Names matter. Since 1789, the median country has changed its name four times. When it does so, it makes a declaration that usually implies a change from the status quo. In 1792, the declaration of the French Republic signaled the rejection of monarchy. Ten years later, Napoleon Bonaparte brought the republican experiment to an end with a constitution that made him Consul for Life and allowed him to select his own successor (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1969, 145). Nevertheless, Beethoven named his third symphony for Bonaparte. It was only two years later when a revised constitution renamed France an empire that disappointment erupted among liberals and Beethoven struck Bonaparte’s name from the symphony (Cantor Reference Cantor2007, 388). The symbolic name change was arguably more impactful than the previous change in institutions and even regime type.

Names matter. Since 1789, the median country has changed its name about four times. When it does so, it makes a declaration that usually implies a change from the status quo.

The study of place names (i.e., toponymy) is an interdisciplinary field—prominent in geography, linguistics, history, and other disciplines. Critical toponymy emphasizes governmentality, social justice, resistance, power, and politics (Rose-Redwood, Alderman, and Azaryahu Reference Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryahu2010). Yet, political science has rarely considered the names of countries, which is the discipline’s primary unit of analysis.

Using descriptors in country names (including empire, kingdom, Islamic, republic, democratic, socialist, and people’s) as a starting point, this study demonstrates that names of nation-states provide important signals about a country’s politics. Descriptors are an appropriate place to begin establishing a theory of country names because they (1) are common; (2) have meanings that are relatively clear and easily tested; and (3) require less etymological contextualization than other parts of countries’ names. To test my hypotheses, I used the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset to examine whether countries’ descriptors match their characteristics and found that, with one noteworthy exception, descriptors are correlated in the expected direction.

TOWARD A THEORY OF COUNTRY NAMES

Many fields have established the importance of names. Studies of nominative determinism have shown that people are more likely to choose professions related to their surnames (Abel Reference Abel2010). Names are significant for branding strategies (Alderman Reference Alderman, Graham and Howard2016). They can leverage the past and promote a “heritage ambience” to create a community image and connect with the historical and cultural environment (Aplin Reference Aplin2002, 17). Naming is used to draw distinctions among places, leading to associations and differentiations (Myers Reference Myers, Vuolteenaho and Berg2017) and constructing place identity (Douglas Reference Douglas2010, Reference Douglas2012). Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch (Reference Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch2016) viewed place naming as a Foucauldian dispositif that reveals power relations in a society. Because of “the normative power of naming, place names create a material and symbolic order that allows dominant groups to impose certain meaning into the landscape and hence control the attachment of symbolic identity to people and places” (Alderman Reference Alderman, Graham and Howard2016, 208). Names build or divide communities, create identity, (re)write history, and give meaning. They change perception and thereby reality.

Names build or divide communities, create identity, (re)write history, and give meaning. They change perception and thereby reality.

Critical toponymy is concerned primarily with political questions. It has focused on street names and other urban locations (Bigon Reference Bigon2020; Sysiö, Ülker, and Tokgöz Reference Sysiö, Ülker and Tokgöz2023) but also considered the naming of places beyond the urban, especially seas and other oceanic features (Basik Reference Basik2024; Nash Reference Nash2017; Wu and Young Reference Wu and Young2023). The political valence of the names of such features recently was highlighted by efforts to rename the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America.

Naming has been shown to be a tool for asserting authority, constructing national identity, conducting diplomacy, and embedding ideologies within the landscape (Azaryahu Reference Azaryahu2011; Sysiö, Ülker, and Tokgöz Reference Sysiö, Ülker and Tokgöz2023; Yeoh Reference Yeoh, Berg and Vuolteenaho2017). This touches on central topics in political science. To my knowledge, however, there has not been a systematic study of country names, despite them being the most common units of analysis in the study of politics and the most powerful actors in the world. This study focuses on the connection between the political characteristics of countries and their names, particularly their descriptors. I posit two reasons for this link.

First, we should expect a connection between a country’s name and its political institutions and characteristics because both are generally established by the same powerful forces, at least initially. Changing the name of a country is costly, and new names are not chosen lightly or randomly. Critical toponymy has emphasized how powerful and hegemonic forces impose political and ideological messages on populations by (re)naming their physical environment (Düzgün Reference Düzgün2021; Vuolteenaho and Puzey Reference Vuolteenaho, Puzey, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryahu2017). This demonstrates the goals, narratives, and ideology of the dominant group establishing the naming, their level of commitment to these ideas, and success imposing them on those (especially minorities) that might attempt to contest (Alderman Reference Alderman1996; Costa Reference Costa2012) or resist them (Azaryahu Reference Azaryahu2011; Myers Reference Myers, Vuolteenaho and Berg2017; Yeoh Reference Yeoh, Berg and Vuolteenaho2017). This study is the first to empirically demonstrate and measure the strength of that signal and is of value to political scientists who seek to understand the narratives, goals, and ideology of a regime. This is especially true soon after a revolution or political upheaval, when the intentions of the new regime may be unclear and evidence of its policy “on the ground” is still becoming evident.

Second, a country’s name and its political institutions are linked because, once established, it shapes how its politics evolve; that is, a country’s name creates identity, generally reinforcing the politics and ideology of the forces that named it. Whether we think in terms of Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1991) “imagined political communities” or Gramscian hegemony (i.e., a ruling class maintains power through both force and intellectual and moral leadership over society), names are “used as tools by the hegemonic groups to penetrate their world views into the daily life of the people and thereby naturalize their ideologies in society” (Düzgün Reference Düzgün2021, 3). Country names often suggest the dominance of majority groups, as in India, Finland, Kazakhstan, Bangladesh, Albania, Malaysia, and Botswana. In some cases (e.g., India and Malaysia), these names are suggestive of the dominant ethnic group without necessarily being directly named for them. For example, in India, the most common language (Hindi) and religion (Hindu) are tied etymologically to the Indus River, from which the name of the nation-state also derives.

Country names also are particularly enduring and costly to change and may become layered or difficult to alter over time (Thelen Reference Thelen, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003). This is particularly important in postcolonial contexts, for which Voulteenaho and Berg (2017) demonstrated that names are used in “the colonial silencing of indigenous cultures, the canonization of nationalist ideals in the nomenclature of cities and topographic maps…as well as the formation of more or less fluid forms of postcolonial identities.” Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch (Reference Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch2022) demonstrated the possibility of decolonization through neotoponymy. Names also can assist in the production of a nation in a postcolonial multiethnic context (Yeoh Reference Yeoh, Berg and Vuolteenaho2017). Similarly, multiethnic or multinational identity is evident in names such as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics—two examples that also demonstrate the importance of the descriptors that countries include in their formal names.

The descriptors that countries choose when they select a new name are the most obvious link between a name and a political system or ideological value. Decolonizing a name or choosing to name a country after a majority ethnic group is a political choice. Yet, it is difficult to imagine a clearer signal than inserting a word like “socialist” or “Islamic” in the name of a country. Empirical analysis of descriptors deepens our understanding of country names, their relationship to critical toponymy, and the political priorities they signal.

This study takes the straightforward step of examining the empirical link between country names and their political characteristics. It is a necessary first step in the study of country names because understanding the magnitude of the connection is useful. If there is no significant relationship, then a fresh investigation of the subject and theory likely would be required.

CATEGORIES OF DESCRIPTORS

This section identifies five categories of country-name descriptors, briefly discusses what they mean, and presents hypotheses to test them. I created the categories by reading through and coding all 814 distinct historical country names in the V-Dem dataset into categories according to their explicit meaning (Givens Reference Givens2025). These five descriptors fall into two broad groupings. The first are monarchical and republican, both of which indicate how the heads of state (HoS) were chosen and their term in office. The second category signals state ideologies: religious, socialist, democratic, and (again) republican. The five categories and their related hypotheses are outlined in the following subsections.

Monarchical

Monarchies are the most common regime type throughout history (Gerring et al. Reference Gerring, Wig, Veenendaal, Weitzel, Teorell and Kikuta2021) and highly varied (Barany Reference Barany2013; Stepan, Linz, and Minoves Reference Stepan, Linz and Minoves2014). A monarchy can be “a state ruled by a single absolute hereditary ruler” or a monarch “who rules according to the constitution” (Bogdanor Reference Bogdanor1995, 1). Either way, monarchs are “empowered by law or custom to remain in office for life” (Kokkoen and Sundell Reference Kokkoen and Sundell2014, 442). Monarchies usually are transferred according to rules of kinship-based succession, including election by and from small groups such as a royal council, which may choose among members of a royal family (Kurrild-Klitgaard Reference Kurrild-Klitgaard2000). I therefore hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Countries with a monarchical descriptor in their name have:

H1a: heads of state with lifetime tenure

H1b: heads of state who inherit their office or are chosen from a small hereditary group (monarchical succession)

I qualified descriptors as monarchical if they referred to a hereditary ruler. Most languages and cultures have their own term for a hereditary ruler; therefore, monarchies have the widest range of country-name descriptors, including emirate, kingdom, empire, beylik, hereditary, Khaan, duchy, electorate, landgraviate, Dai Viet Quoc, and principality. I combined all of these into a single monarchical-descriptor dummy variable.

Republican

Republics are by far the most common regime type today. Definitions vary, but James Madison (Reference Madison1788) described a republic as “a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people, and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior.” I used these basic characteristics—which are common although not universal in definitions of republics—as the basis for my second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Countries with a republican descriptor in their name have:

H2a: heads of state with limited terms

H2b: heads of state chosen either by direct election or the legislature (republican succession)

H2c: higher levels of electoral democracy

To create the republican category, I combined countries with a name that includes the word “Republic” or “Commonwealth,” which is synonymous with “republic” as an English translation of the original Latin version: res publica (i.e., the common good) (The Monthly Magazine 1796, 280).

Religious

Throughout history, theocracies that seek to enshrine religion into the institutions of the state and thereby use their faith as a legitimating ideology are common (Glazer Reference Glazer, Ferrero and Wintrobe2009; Potz Reference Potz and Potz2020). Although it may be possible to preserve freedom of religion in constitutional theocracies, I expected theocracies, on average, to experience less religious freedom (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2010), which is the basis for my third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Countries with a religious descriptor in their name have:

H3a: lower levels of religious freedom

H3b: religion as a legitimating ideology

I combined countries with a name that includes the words “Islamic,” “papal,” or “bishopric” into a single religious descriptor to test my hypothesis.

Socialist

Socialism is a political and economic system associated with an emphasis on the equal distribution of resources (Alexander Reference Alexander2015) and state or collective ownership of property (Heywood Reference Heywood2017). The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and its early satellites (including the Mongolian People’s Republic) established the overlapping use of the terms “socialist,” “soviet,” and “people’s,” although no country ever used all three. Muamar Qadhafi coined a similar term, “Jamahiriya,” based on a combination of the words “masses” and “state” (Bassiouni Reference Bassiouni2013, 64). My fourth hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 4: Countries with a socialist descriptor in their name have:

H4a: a more equal distribution of resources

H4b: higher levels of state ownership and control of the economy

I combined countries with a name that includes the descriptors socialist, soviet, people’s, and/or Jamahiriya into a single socialist descriptor to test my hypothesis.

Democratic

Dahl (Reference Dahl2000) outlined five process-oriented criteria by which to define democracy: participation, voting equality, enlightened understanding, control of the agenda, and inclusion of adults. The V-Dem dataset explicitly cites Dahl’s approach to defining democracy as the basis for its primary measure: electoral democracy, also known as polyarchy (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Coppedge, Gerring and Teorell2014).

For alignment with my other hypotheses, I made the naïve prediction that countries with a democratic descriptor are more democratic. However, a cursory knowledge of countries with this descriptor suggests that this is not its intended meaning. Therefore, I also hypothesized that when used in country names, the term is connected to Marxist–Leninist ideas such as people’s democracy and democratic centralism. In this sense, it may be a synonym to people’s. I therefore hypothesized that it also will be correlated with a more equal distribution of resources and higher levels of state ownership and control of the economy:

Hypothesis 5: Countries with a democratic descriptor in their name have:

H5a: higher levels of electoral democracy

H5b: a more equal distribution of resources

H5c: higher levels of state ownership and control of the economy

Only the democratic descriptor is in this category.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

My data are from the V-Dem dataset (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Coppedge, Gerring and Teorell2014). To create my variables of interest, I examined every unique historical name in the V-Dem dataset and grouped descriptors into the five categories described previously. I then coded every country-year based on the inclusion of these descriptors. These binary variables for the descriptor categories comprised my variables of interest.

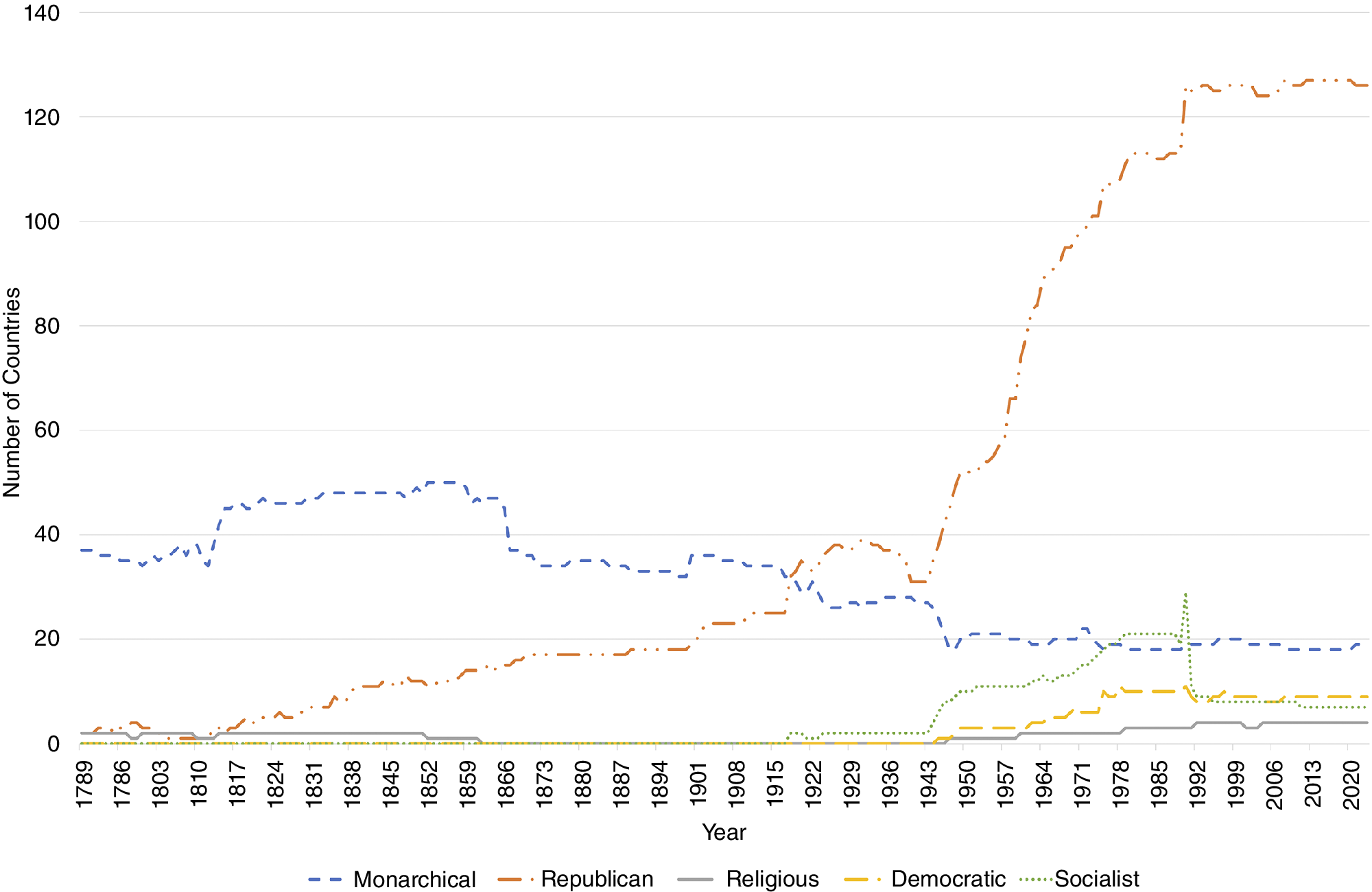

Figure 1 illustrates striking trends in the popularity of various country-name descriptors over time. Socialist descriptors experienced a rapid increase after World War II; a brief spike as states split after the collapse of the Soviet Union; and then a sharp decline as most of the countries abandoned socialism as an official ideology. Democratic descriptors followed a similar trajectory; today, most countries in both categories overlap as democratic people’s republics. Democratic descriptors seem to be particularly favored by the communist side when countries are split between two governments, as was or is the case in Germany, Vietnam, Yemen, and Korea. Two countries in nineteenth-century Europe used the religious descriptor bishopric or papal, which then disappeared. The category reemerges with the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1949 and, in 2024, four countries used Islamic as a descriptor. The most significant trend has been the slow decline of monarchies and the gradual and then rapid rise of republics. As decolonization led to the emergence of approximately 100 new countries, the majority adopted a republican descriptor, perhaps to signal their rejection of colonial oppression. This was further boosted by the breakup of the Soviet Union, marking the last significant increase in the number of countries, most of which adopted republican descriptors. Even as political scientists debate the ebb and flow of democracy and the rise of illiberal and hybrid democracies, the republic has emerged as the unmatched default in country names.

Figure 1 Country-Name Descriptors by Category, 1789–2023

Online appendix A includes a full description of the definition and coding of the dependent and control variables. For the regression analysis, I used a fixed-effects panel approach to control for unobserved heterogeneity among groups (Allison Reference Allison2009) and draw clearer causal inferences from the data (Gangl Reference Gangl2010). For continuous dependent variables, I used linear fixed-effects models with robust standard errors; for binary dependent variables, I used a fixed-effects panel logit. These fixed-effects models are parsimonious and interpretable, and they reliably fit the data. The models should provide accurate estimates because they control for any country-level, individual-specific effects that are correlated with variables in the model (Wooldridge Reference Wooldridge2010). All models include two control variables: the natural logs of population and GDP per capita.

RESULTS

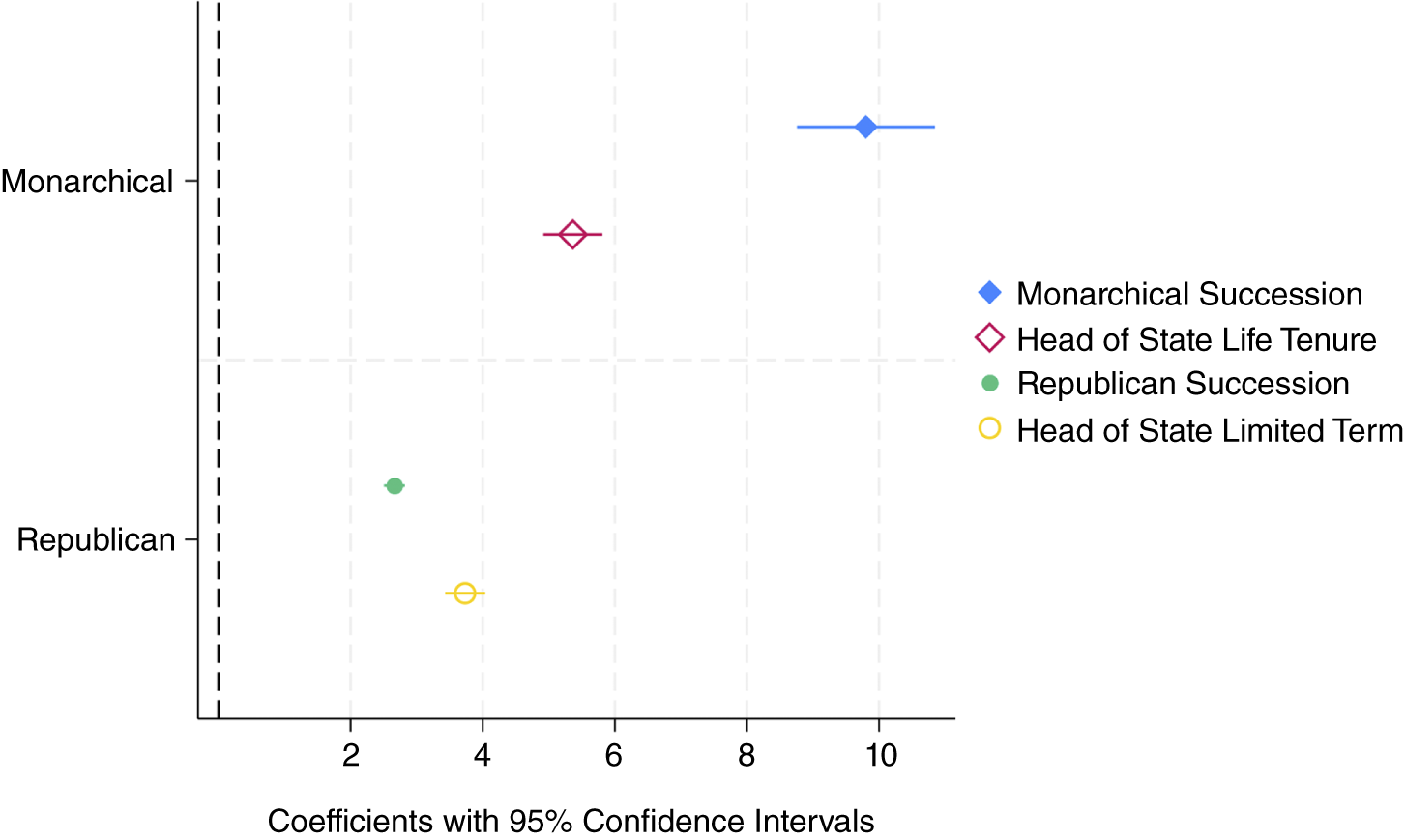

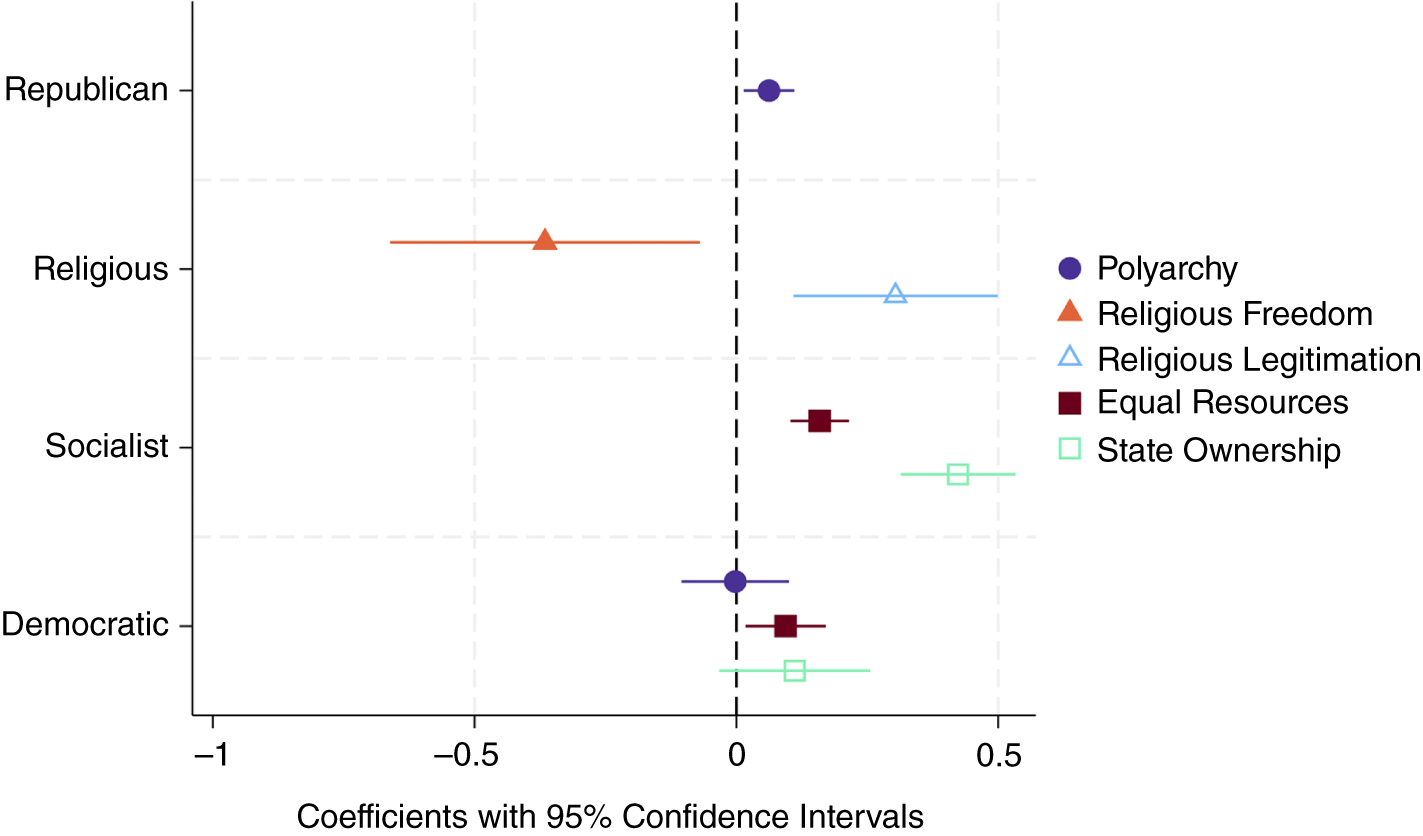

Figures 2 and 3 depict the results of 12 separate models by displaying the point estimates of coefficients with bars that represent 95% confidence intervals. When these intervals do not overlap with zero (represented by a dotted vertical line), they are statistically significant. For legibility reasons, the figures do not use odds ratios. Coefficients for the models as displayed in figures 2 and 3 are best considered primarily in terms of statistical significance, direction, and relative size. The size of coefficients could be interpreted as an indicator of the strength of signal that these descriptors provide. I found that country-name descriptors are highly accurate with P values of 0.01 or smaller, except in the case of the democratic descriptor. The first four models (see figure 2) have binary dependent variables and, therefore, use logistic regressions.

Figure 2 Effect of Country-Name Descriptor on Corresponding Country Characteristics (Logit Models)

Figure 3 Effect of Country-Name Descriptor on Corresponding Country Characteristics (Linear Models)

Figure 2 illustrates that the predictive power of the monarchical descriptors is particularly strong. By translating these coefficients to odds ratios, the odds of monarchical succession increases approximately 18,000 times with a monarchical descriptor and the odds of life tenure increases more than 200 times. Only a few unusual and short instances defy these trends. In no case in the data was a HoS directly elected in a country with a monarchical descriptor. Except for brief periods in Afghanistan and Cambodia, the only cases in which a country with a monarchical descriptor put term limits on its HoS was the highly unusual federal presidential elective constitutional monarchy of the United Arab Emirates.

The impact of republican descriptors in figure 2 also has a clear statistically significant effect. A republican descriptor makes republican succession 14 times more likely and the odds of term limits for a HoS increase more than 40 times. More than 90% of regimes with republican descriptors explicitly limit the term of the HoS and less than 1.5% give the HoS explicit lifetime or unlimited terms; the longest running of these is the Islamic Republic of Iran. Even more rare are cases of heredity or a royal council determining an heir in a country with a republican descriptor. The only meaningful example occurred when the office of Stadtholder in the Republic of the United Netherlands went from de facto to de jure hereditary in 1747.

Whereas the results in figure 2 focus on the selection and tenure of the HoS, those in figure 3 demonstrate a country’s commitment to political, socioeconomic, and religious values. Regimes with republican descriptors are more committed to democracy; although the effect is small—an approximate 6% increase in the predicted polyarchy score—it is significant. The impact of a religious descriptor is much stronger, correlating with an approximate 30% decrease in religious freedom and an equivalent increase in religion as a legitimating ideology. Socialist descriptors correlate with a 16% increase in equal access to resources and a 43% increase in state ownership and control of the economy. Democratic descriptors are uncorrelated with democracy as well as state ownership and control of the economy. However, they do show a significant albeit minor relationship to equal resources. Except for the democracy descriptor, the results proved extremely robust to changes in the periodization and model specifications. The use of fixed-effects models means that these results are based on within-country variance (i.e., countries that have changed their name over time). Random-effects models include between-country variance and indicated only one substantively different result: a positive significant coefficient for polyarchy in countries with a democratic descriptor. These and several other alternative models are presented in online appendix A.

The number of name changes by country in the V-Dem dataset varies between zero and 15, with an approximate mean of 3.96 and a standard deviation of 2.45. Two examples, one with many name changes and one with none, illustrate the meaning of the quantitative results. The Kingdom of Sweden has had no changes to its name throughout the dataset and maintains a system of lifetime tenure for its HoS throughout the entire 234-year period covered. The only exception to monarchical succession was between 1818 and 1848, when Charles XIV John, a Bonapartist general, was elected to replace an heirless Swedish king.

By contrast, Serbia had 13 distinct names in the V-Dem dataset. The Kingdom of Serbia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1882. Between that year and 1945, it appears in the dataset as the Kingdom of Serbia; the Kingdom of Serbia under Central Powers Occupation; the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes/Kingdom of Yugoslavia; and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia under German Occupation. Despite the changes, the monarchical descriptor is present throughout. Moreover, the data confirm both monarchical succession and lifetime tenure for the HoS, with short exceptions primarily during periods of occupation. In 1945, the country became part of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. This was followed by the emergence of term limits and the end of monarchical succession, although not the hypothesized republican succession and higher levels of polyarchy. This suggests that in a more sophisticated theory of country-name descriptors, a socialist descriptor would change or nullify the meaning of the republican descriptor. As expected with the socialist descriptor “people’s,” there was a significant upturn in state ownership and in the equal division of resources. Finally, beginning in 1992, the country’s name changed to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia; the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro; and, ultimately, the Republic of Serbia. Most of these names possess a republican descriptor and demonstrate the expected republican succession, term limits, and higher levels of polyarchy.

DISCUSSION

The results of this analysis may appear self-evident and intuitive, yet this is the first time that this relationship has been tested empirically. Additionally, in the rare instance that countries’ descriptors are considered, it often is in a case such as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. This may lead us to believe that descriptors are misleading or meaningless. When I first conceived of this project, I expected to find primarily negative correlations. Yet, with the notable exception of the democratic descriptor, country-name descriptors proved accurate and robust. Their accuracy makes descriptors useful to comparative political science in various ways. In the early days after a revolution, a successful bid for independence, or another type of upheaval, we often are uncertain of what to expect from a new regime. Country names help in judging the commitment of a new regime to an ideology. In time, country names reveal the technology of governance, in terms of both the regime’s continued commitment to the ideology reflected in the name and in its naturalization of that ideology into a population’s identity and politics.

Having established that descriptors can indicate the political characteristics of countries, what might their absence signify? Approximately 34% of the country–years in the V-Dem database do not have any of the descriptors discussed in this study. Canada (post-1982), Grenada, Hungary (post-2012), Jamaica, and many other countries do not use any descriptors. In the English language, Japan generally lacks a descriptor, but “State of Japan” is arguably a better translation of the Japanese name. Countries without any descriptors seem less likely to have strong characteristics one way or another. This is the inverse of the idea that names are used to impose a certain vision of a country. If the powers naming a country want to send a strong signal that it has a monarch, they are likely to call it a kingdom; if they want to send a strong signal that it does not have a monarch, they might call it a republic. If they want the status of the HoS to be ambiguous, it seems likely that they would not use either descriptor. This arguably is the case for Japan, which—despite maintaining an emperor as HoS—had political and diplomatic reasons to downplay that fact after World War II. Furthermore, a lack of descriptors may indicate ongoing contestation or a lack of clear consensus among the powers coming together to name a country.

This research is focused on what Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch (Reference Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch2016) called place-name studies. It takes the names of places as given and examines their meanings. However, there may be an opportunity for a study of the place-naming of countries with a “focus on the procedures of and stakes at play when giving a certain name to a specific place” (Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch Reference Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch2016, 4). This could prove useful especially in understanding the ambiguous results connected to democratic descriptors. A careful study of the process of naming may reveal that this descriptor was never intended to convey socialist or democratic values. Rather, it may have been chosen to appeal to a broad coalition of support from different factions. This type of research could be conducted through process tracing and the study of historical documents and debates that are relevant to the selection of country names.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The study of country names is overdue for further investigation, including the descriptors sovereign, suzerain, colony, and protectorate. The effect of exonyms (i.e., non-native names for geographical places) likewise deserves examination: Are there meaningful differences among countries that use names forced on them by colonizers or any measurable impact when countries decolonize their names? Does the choice of whether to enshrine an ethnic majority in the name of a country have subsequent effects on how inclusive a country will be toward ethnic minorities?

Future research also could explore how both official and unofficial country names are used in practice. Everyday usage of country names—whether by citizens, media, or political actors—may reveal implicit narratives, contested identities, and shifts in national self-perception. Informal or alternative names (e.g., Holland and Burma) may signal political resistance, historical continuity, or linguistic convenience. Examining the political negotiations and historical moments that led to naming choices could illuminate the role of national identity, diplomatic strategy, and ideological alignment.

Furthermore, the study of names in political science need not be confined to only country names; it could expand to other areas of onomastics (i.e., the study of the history and origin of proper names). The names of political parties often contain many of the same descriptors studied herein, as well as religious and ethnic markers that may shape political perceptions. Similarly, the names of leaders and politicians provide an underexplored area of research. If people are more likely to choose professions that match their surnames, they also may be more inclined to support political leaders whose names evoke positive associations or historical connections.

Finally, future research could benefit from analyses of naming across different political eras, colonial and postcolonial contexts, and regions. Investigating how naming conventions evolve over time and the sociopolitical forces that drive these changes could deepen our understanding of the intersection among language, power, and governance. Other disciplines have long asked, “What’s in a name?” It is time for political science to do the same.

Other disciplines have long asked, “What’s in a name?” It is time for political science to do the same.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525101479.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their valuable feedback and contributions, I thank Heather Pincock, Eric Castater, Charity Butcher, Benjamin Taylor, Daniel Matisoff, Evan Mistur, and Andrew MacDonald; the editors of PS; the anonymous reviewers; the copyeditor, Constance Burt; and my graduate research assistant, Liz Maina. I also thank the community at Spelman College, as well as my parents, wife, and children, for their unwavering support.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/REJ38B.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.