Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe mental illness characterized by significant fluctuations in emotions, energy levels, and thoughts, affecting up to 1.1% of the world’s population [Reference Oliva, Fico, De Prisco, Gonda, Rosa and Vieta1]. In addition to mood symptoms, individuals with BD often experience cognitive impairments. Cognition broadly includes both neurocognition, which incorporates core mental processes such as memory, attention, and executive functions, and affective cognition (AC), which involves functions related to perceiving, interpreting, and responding to emotional stimuli, representing an integration of emotional and neurocognitive processes [Reference Elliott, Zahn, Deakin and Anderson2]. These domains collectively shape how individuals perceive, process, and respond to the world around them. Understanding these aspects is particularly important in conditions like BD, since impairments in these domains can profoundly impact daily functioning, interpersonal relationships, and overall quality of life [Reference Jensen, Knorr, Vinberg, Kessing and Miskowiak3]. While neurocognitive impairments have been extensively studied and recognized in BD [Reference Keramatian, Torres and Yatham4], there has been a growing interest in AC as a key area of investigation, due to its crucial role in everyday interactions, contributing to social adaptation and integration [Reference Sagliano, Ponari, Conson and Trojano5]. AC incorporates various interconnected domains, including emotional intelligence, emotional decision-making, reward and punishment processing, emotion regulation, and facial emotion recognition (FER) [Reference Miskowiak, Seeberg, Kjaerstad, Burdick, Martinez-Aran and del Mar Bonnin6]. Individuals with BD exhibit several alterations across these domains, including impaired emotional intelligence [Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent and Lahera7], disrupted decision making [Reference Ramírez-Martín, Ramos-Martín, Mayoral-Cleries, Moreno-Küstner and Guzman-Parra8], and difficulties in emotion regulation [Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Fornaro, De Bartolomeis and Serretti9]. Among these components of AC, FER is the ability to identify and discriminate the emotional meaning of specific facial expressions displayed by other people, typically categorized into six basic and discrete emotions (i.e., anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise) [Reference Ekman and Friesen10]. FER serves as a bridge between cognitive and emotional processes, and it is critical for interacting and communicating with others, allowing individuals to make appropriate cognitive and behavioral adaptations during interpersonal exchanges [Reference Sagliano, Ponari, Conson and Trojano5]. Deficits in FER can have a critical impact on people’s ability to function in daily life, including in work and in social settings [Reference Porcelli, Van Der Wee, van der Werff, Aghajani, Glennon and van Heukelum11]. The International Society of Bipolar Disorder Targeting Cognition Task Force [Reference Miskowiak, Seeberg, Kjaerstad, Burdick, Martinez-Aran and del Mar Bonnin6] emphasized the significance of understanding deficits in AC, including FER, in individuals with BD. This understanding is essential for uncovering the neurobiological basis of these impairments and for developing targeted treatments that go beyond symptom control, to improve patient-centered outcomes, including functioning, well-being, and overall quality of life. To quantify the magnitude of FER impairments in BD, we previously conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis [Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Montejo, Possidente and Bracco12] comparing patients with BD with individuals with other psychiatric disorders. Our findings revealed that individuals with BD showed a better FER performance compared to those with schizophrenia, but performed worse than individuals with major depressive disorder.

Currently, there is a lack of meta-analytic evidence to quantify whether and how FER differs between BD patients, unaffected first-degree relatives (FDRs), and healthy controls (HCs), relevant for guiding future research and clinical practice. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to (a) investigate FER performance in BD compared with FDRs and HCs, and (b) identify potential predictors that might influence FER performance.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie13]. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023422035). The MOOSE checklist and deviations from the protocol are reported in Supplementary Appendix I.

Identification and selection of studies

The PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, EMBASE, and PsycINFO databases were searched from inception to March 28, 2024. Search strategies are provided in Supplementary Appendix II. Reference lists of each included study, textbooks, and other materials were searched to identify additional studies. Inclusion criteria required original studies (a) to provide quantitative data on FER, (b) in people diagnosed with BD (c) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases diagnostic criteria, (d) and compared with unaffected FDRs (i.e., without BD) or HCs. Both observational and interventional studies were considered, but only baseline data were collected. No age, sample size, or language restrictions were applied. Where populations overlapped across multiple studies, the largest study with the most representative data, or the most recent, was preferred. Exclusion criteria included (a) reviews, (b) case reports, (c) case series, (d) studies not peer-reviewed, (e) studies that were retracted after publication, and (f) animal studies. Three authors (MDP, VO, CP) independently examined studies of potential interest at both title and abstract and full-text screening, and in case of disagreement, another author (JR) was consulted. The same three authors independently extracted relevant data regarding outcome measures and study characteristics. In cases of insufficient data, corresponding authors were contacted twice.

Risk of bias

Three authors (MDP, VO, CP) independently evaluated the risk of bias of included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [Reference Stang14], and another author (JR) resolved disagreements. The NOS scores were converted to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards, as done elsewhere [Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Montejo, Possidente and Bracco12].

Outcomes

FER tasks focusing on emotion identification (i.e., the ability to match an emotional stimulus with its corresponding emotion) or discrimination (i.e., the ability to discriminate whether two presented faces show the same emotion or not) were studied. Any outcome aimed at exploring the differences in FER was considered eligible for inclusion. “Accuracy” was defined as any measure assessing the overall correct recognition of emotions (e.g., percentage of correct recognition, scores from specific scales evaluating the number of emotions correctly identified, and author-defined accuracy). “Reaction time” was defined as the time elapsed before responding, and “number of errors” referred to the count of errors made by individuals during a FER task.

Statistical analysis

Random-effect meta-analyses (restricted maximum-likelihood estimator) [Reference Harville15] were conducted through the R-package “metafor” [Reference Viechtbauer and Viechtbauer16], using R, version 4.3.1 [17]. The results were presented for each outcome according to a three-level scheme, as done in our previous studies [Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Montejo, Possidente and Bracco12, Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Kjærstad, Miskowiak and Anmella18]. Level one represents a global measure of FER, referring to the overall ability to recognize any emotion. Level two is a measure of FER based on emotion valence, distinguishing between negative (i.e., anger, disgust, fear, or sadness), or positive (i.e., happiness or surprise) emotions. Level three is a measure of FER based on specific emotions analyzed separately (i.e., anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, or surprise). A graphical representation of this three-level scheme is presented in Supplementary Appendix II. When studies did not provide information at all levels, we hierarchically derived missing levels to maximize data inclusion, where possible. Specifically: (a) when studies provided only level-three data (i.e., relative to specific emotions), we computed mean values for emotions belonging to the same valence (i.e., negative or positive) to obtain level-two information; (b) when studies reported level-three data without an overall measure of FER, we computed mean values across all available individual emotions to obtain level-one information; (c) when studies reported only level-two data (i.e., positive or negative emotion scores), we computed mean values across them to derive level-one information. Standardized mean differences (SMD) with their confidence intervals (CIs) were used as effect sizes and represented by Hedge’s g. These values can be interpreted as indicating small (SMD = 0.2), moderate (SMD = 0.5), or large (SMD = 0.8) effects, based on their magnitude [Reference Cohen19]. Heterogeneity was assessed by using Cochran’s Q test [Reference Cochran20], τ 2 and I 2 statistics [Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page21]. Prediction intervals were calculated. For the associations analyzed at level one, meta-regression analyses were conducted according to the following predictors considering original study characteristics (i.e., primary or secondary outcome, and publication year), sociodemographic (i.e., % of females, mean age, and years of education), clinical characteristics of people with BD (i.e., % of people in (hypomania), % of people in depression, % of people in euthymia, % of BD-I, age at onset, duration of illness, depression symptoms severity, and manic symptoms severity), and FER task characteristics (i.e., duration of the stimulus, duration of the inter-stimulus interval, maximum emotion intensity, minimum emotion intensity, presence of morphing, number of emotions considered in the whole task, number of stimuli, presence of practice, and presence of neutral faces), when at least 10 studies providing this data were available. For the associations analyzed at the levels two and three, the same meta-regression analyses were conducted when the Cochran’s Q test presented a p < 0.10 or the I 2 statistic showed a value >50%, and when at least 10 studies providing this data were available. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the robustness of the results: (a) excluding one study at a time from the main analysis (i.e., leave-one-out); (b) by including only good-quality studies according to AHRQ standards; (c) by removing those studies whose lower-level data were calculated from higher-level information (only for levels one and two). Publication bias was explored by visual inspection of funnel plots and using the Egger’s test [Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder22] when at least 10 studies were available.

Results

Overall, 3388 records were identified. After duplicate removal, 1667 were excluded at the title/abstract level and 143 after the full-text evaluation. Finally, 99 papers (considering 100 individual studies) were included, and 86 of them (considering 87 individual studies) provided enough data to perform a meta-analysis comparing people with BD to FDRs or HCs. The flow diagram is reported in Figure 1. Details on included studies are displayed in Table 1. Excluded studies, as well as additional information about the studies included only in the systematic review, are presented in Supplementary Appendices III-IV.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; BLERT, Bell-Lysaker emotion recognition test; CAFPS, Chinese affective facial picture system; CANTAB, Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery; Cohn-Kanade, Cohn-Kanade action unit-coded facial expression database; DANVA, diagnostic analysis of non-verbal accuracy; DIGS, Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies; DIP, The Diagnostic Interview for Psychoses; DSM-III-R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – third ed. Revised; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – fourth ed.; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – fourth ed. – Text Revision; DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – fifth ed.; EEMT, Emotional Expression Multimorph Task; ER-40, Penn Emotion Recognition-40; ER-96, Penn Emotion Recognition-96; EK, Ekman 60 Faces Test; FDRs, First-Degree Relatives; FEDT, Facial Emotion Discrimination Test; FEIT, Facial Emotion Identification Test; FEED, Facial Expression and Emotions Database; FEEL, Facially Expressed Emotion Labeling; FEEST, Facial Expressions of Emotion: Stimuli and Tests; FOE, The Face of Emotions; HCs, healthy controls; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases; JACFEE, Japanese and Caucasian Facial Expressions of Emotion; KAMT, Kinney’s Affect Matching Test; KDEF, Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces; K-SADS-PL, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, present and lifetime version; MIMI, MIMI Facial Expression Database; MINI, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; Mini-SEA, mini-Social Cognition and Emotional Assessment; NA, not available; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; PEAT, Penn Emotion Acuity Test; POFA, Pictures of Facial Affect; SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SCID-P, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders-Patient version; TRENDS, Tool for Recognition of Emotions in Neuropsychiatric Disorders; VERT-K, Vienna Emotion Recognition Tasks; WASH-U-KSADS, Washington University Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia.

Characteristics of included studies

The 100 studies included were published between 1996 and 2024 in 21 countries worldwide. Ninety-four studies (94%) were cross-sectional, and six (6%) were longitudinal. Regarding the age group, 84 (84%) were conducted in adults, 12 (12%) in children/adolescents, and four (4%) in mixed age groups.

Individuals with BD (n = 4920, range = 7–275; females = 56%, mean age = 34.1 ± 9.1) had an age at onset of 21.2 ± 7.6 years and a duration of illness of 13.6 ± 8.7 years. 74.5% were diagnosed with BD-I. Regarding their mood state, 62.9% were euthymic, 18.1% depressed, and 12.5% (hypo)manic. In 21 studies (21%), the information regarding the mood state was unclear. Control groups included both FDRs (n = 676, range = 20–286, females = 55%, mean age = 36.1 ± 12), and HCs (n = 4909, range = 10–380, females = 53.2%, mean age = 32.5 ± 9.5).

Ninety-four studies (94%) used a FER identification task, and 19 studies (19%) used a FER discrimination task (Supplementary Appendix IV).

Risk of bias evaluation

Sixty-five studies (65%) were considered “good quality” according to the AHRQ standards, 20 studies (20%) were considered “fair quality,” and 15 studies (15%) were considered “poor quality.” Additional details are available in Table 1 and in Supplementary Appendix V.

Main analyses

Table 2 displays the main results of all the meta-analyses conducted. Figure 2 is the jungle plot [Reference De Prisco and Oliva23] for the differences in FER accuracy and reaction time among adult populations.

Table 2. Results of the meta-analyses in detail

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; CIs, confidence intervals; FDRs, first-degree relatives; HCs, healthy controls; PIs, prediction intervals; SMD, standardized mean difference. Statistically significant results (p < 0.05) are highlighted in bold.

Figure 2. Jungle plot for differences in facial emotion recognition accuracy (left) and reaction time (right), adults only. BD, bipolar disorder; FDRs, first-degree relatives; HCs, healthy controls. Circles represent HCs, while triangles represent FDRs. Black-filled circles or triangles indicate statistically significant comparisons, while white-filled ones indicate non-significant comparisons. Point size is proportional to the number of patients included in that specific comparison.

Regarding the identification of any emotion, adults with BD were less accurate (k = 65; SMD = −0.47; 95% CIs = −0.56, −0.38; p-value <0.001; I 2= 63.4%) and showed higher reaction time (k = 25; SMD = 0.57; 95%CIs = 0.33, 0.81; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 89.3%) compared to HCs.

Regarding the identification of negative and positive emotions, adults with BD were less accurate (k = 45; SMD = −0.32; 95%CIs = −0.43, −0.21; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 66.3%), and showed higher reaction time (k = 19; SMD = 0.43; 95%CIs = 0.15, 0.7; p-value = 0.002; I 2 = 90.1%) compared to HCs, during the recognition of negative emotions. Similarly, they were less accurate (k = 39; SMD = −0.28; 95%CIs = −0.39, −0.16; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 63.2%), and showed higher reaction time (k = 13; SMD = 0.62; 95%CIs = 0.33, 0.91; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 88.2%), during the recognition of positive emotions too.

Regarding the identification of specific types of emotions, adults with BD were less accurate than HCs in recognizing anger (k = 32; SMD = −0.26; 95%CIs = −0.34, −0.18; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 26.3%), disgust (k = 22; SMD = −0.33; 95%CIs = −0.46, −0.20; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 52%), fear (k = 33; SMD = −0.37; 95%CIs = −0.49, −0.24; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 65.7%), happiness (k = 35; SMD = −0.19; 95%CIs = −0.27, −0.11; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 25.8%), neutral (k = 16; SMD = −0.17; 95%CIs = −0.29, −0.05; p-value = 0.005; I 2 = 25.4%), sadness (k = 36; SMD = −0.22; 95%CIs = −0.33, −0.12; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 53.6%), and surprise (k = 17; SMD = −0.31; 95%CIs = −0.4, −0.21; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 0%), and showed higher reaction time during the recognition of anger (k = 11; SMD = 0.46; 95%CIs = 0.18, 0.75; p-value = 0.001; I 2 = 86.1%), fear (k = 11; SMD = 0.38; 95%CIs = 0.2, 0.56; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 61.3%), happiness (k = 12; SMD = 0.55; 95%CIs = 0.27, 0.84; p-value <0.001; I 2 = 88%), neutral (k = 10; SMD = 0.29; 95%CIs = 0.1, 0.49; p-value = 0.03; I 2 = 61%), and sadness (k = 11; SMD = 0.33; 95%CIs = 0.13, 0.53; p-value = 0.001; I 2 = 72.9%).

Additional details are presented in Supplementary Appendix VI.

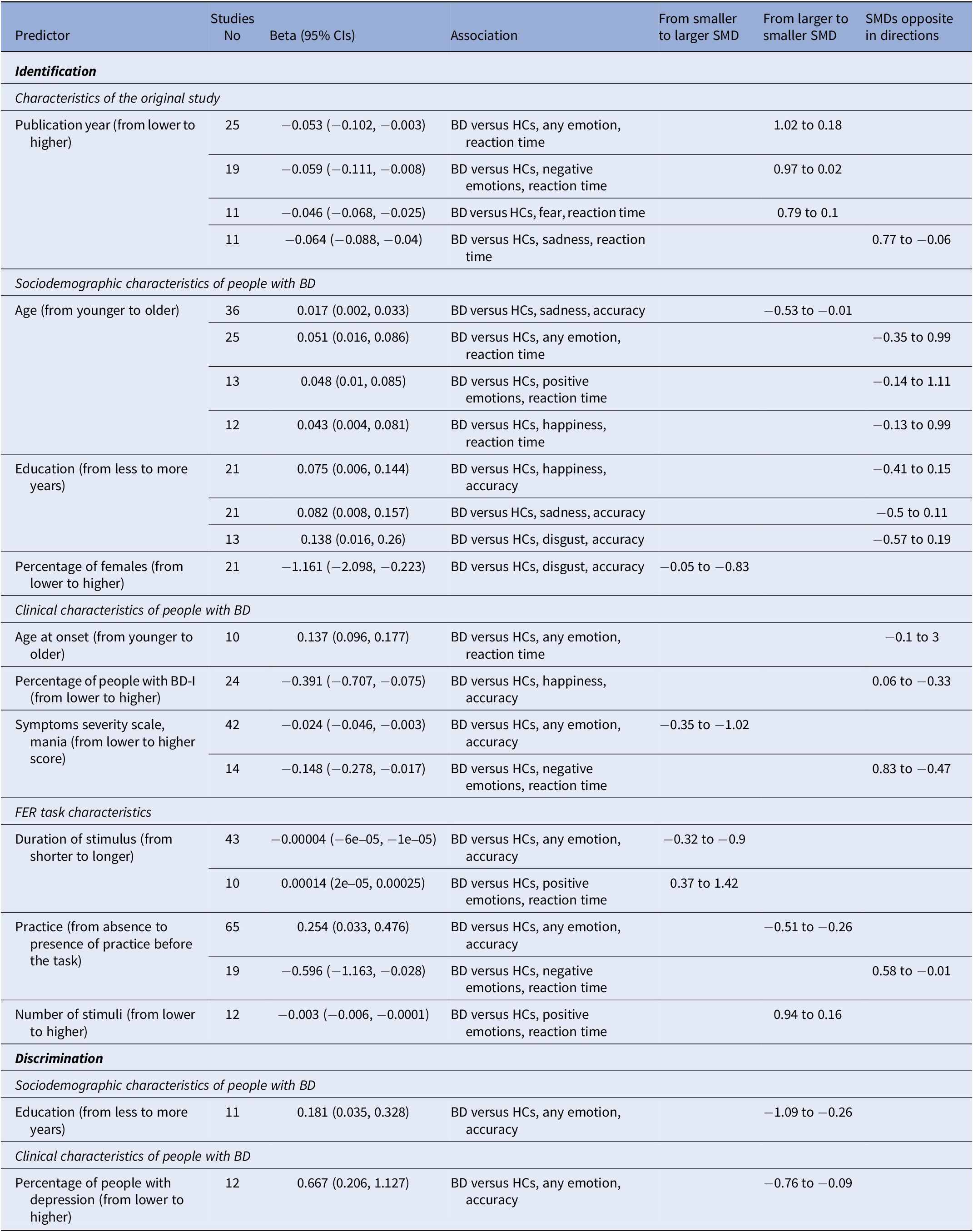

Meta-regression analyses

Characteristics of the original study, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of people with BD, and FER task characteristics were chosen as predictors in the meta-regression analyses. Table 3 displays the significant predictors among all the meta-regressions conducted.

Table 3. Results of the meta-regression analyses, only significant predictors reported

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; CIs, confidence intervals; HCs, healthy controls; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Among the characteristics of the original study, higher publication years were associated to smaller differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the reaction time during the identification of any emotion (k = 25; beta = −0.05; 95%CIs = −0.1, −0.003), the reaction time during the identification of negative emotions (k = 19; beta = −0.06; 95%CIs = −0.11, −0.01), and the reaction time during the identification of fear (k = 11; beta = −0.05; 95%CIs = −0.07, −0.03).

Among the sociodemographic characteristics of people with BD, older age was associated to smaller differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate identification of sadness (k = 36; beta = 0.02; 95%CIs = 0.002, 0.03), and higher percentage of females was associated to bigger differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate identification of disgust (k = 21; beta = −1.16; 95%CIs = −2.1, −0.22). More years of education were associated to smaller differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate discrimination of any emotion (k = 11; beta = 0.18; 95%CIs = 0.04, 0.33).

Among the clinical characteristics of people with BD, more severe manic symptoms were associated to bigger differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate identification of any emotion (k = 42; beta = −0.02; 95%CIs = −0.05, −0.003). Higher percentage of people experiencing a depressive episode were associated to smaller differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate discrimination of any emotion (k = 12; beta = 0.67; 95%CIs = 0.21, 1.13).

Among the FER task characteristics, longer duration of stimuli was associated to bigger differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate identification of any emotion (k = 43; beta = −4e−05; 95%CIs = −6e−05, −1e−05), and the reaction time during the identification of positive emotions (k = 10; beta = 1.4e−04; 95%CIs = 2e−05, 2.5e−04). On the other hand, presence of practice was associated to smaller differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the accurate identification of any emotion (k = 65; beta = 0.25; 95%CIs = 0.03, 0.48), and the higher number of stimuli was associated to smaller differences between adults with BD and HCs regarding the reaction time during the identification of positive emotions (k = 12; beta = −0.003; 95%CIs = −0.006, −1e04).

Additional details are presented in Supplementary Appendix VI.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted: (a) by excluding one study at a time from the main analysis; (b) by including only good-quality studies according to AHRQ standards; (c) by removing those studies whose lower-level data were calculated from higher-level information.

Additional details are presented in Supplementary Appendix VI.

Publication bias

Publication bias was examined in 21 comparisons with at least 10 available studies. Among these comparisons, publication bias was identified in 10 of them.

Additional details are presented in Supplementary Appendix VI.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the differences in FER among BD, FDRs, and HCs. Overall, adults with BD were less accurate than HCs on all FER identification and discrimination tasks, and they required more time to respond on all FER identification tasks, except those related to disgust and surprise. Differences were more pronounced with greater stimulus durations and manic symptoms severity, and less pronounced when participants had practice before the task. These deficits seem to manifest early in life, as even children/adolescents presented reduced accuracy and increased reaction times compared to HCs. No significant differences were found comparing BD and FDRs.

Regarding comparisons with HCs, our results are consistent with findings observed in other domains of AC, such as emotion regulation [Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Fornaro, De Bartolomeis and Serretti9], and affective decision-making and reward processing [Reference Ramírez-Martín, Ramos-Martín, Mayoral-Cleries, Moreno-Küstner and Guzman-Parra8]. The observed deficits in FER may be explained by several reasons. From a brain functioning perspective, patients with BD undergoing emotion processing tasks like FER appear to exhibit consistent hyperactivation in amygdala activity compared to HCs [Reference Mesbah, Koenders, van der Wee, Giltay, van Hemert and de Leeuw24]. The amygdala is a hub for different networks involved in core affect representation, playing a significant role in emotional stimulus generation and perception [Reference Xu, Peng, Y-j and Gong25]. Its hyperactivation may indicate heightened sensitivity to emotional stimuli, potentially contributing to worsened mood symptoms or the genesis of mood episodes [Reference Mesbah, Koenders, van der Wee, Giltay, van Hemert and de Leeuw24]. Consistently, alterations in other dimensions of AC associated with changes in amygdala activity, such as emotion dysregulation, were also found to be associated with more severe mood symptoms [Reference Oliva, De Prisco, Fico, Possidente, Fortea and Montejo26], with dimensions more strongly influenced by amygdala hyperactivity showing a stronger correlation to symptoms [Reference Oliva, De Prisco, Fico, Possidente, Bort and Fortea27]. Extended neurocognitive impairments observed in BD may also contribute to difficulties in FER. As AC involves the integration of emotions and neurocognitive processes, challenges in FER may depend on the integrity of neurocognitive performance. A post-hoc analysis [Reference Van Rheenen and Rossell28] showed that BD patients with a cognitive performance similar to HCs had also similar FER skills, while impaired neurocognitive functions were associated to deficits in FER. This observation was confirmed by another study [Reference Kjærstad, Eikeseth, Vinberg, Kessing and Miskowiak29] and maintained when the problem was analyzed the other way around. Indeed, emotionally preserved BD patients generally exhibited better cognitive abilities, especially in attention, psychomotor speed, working memory, and executive functions [Reference Varo, Kjærstad, Poulsen, Meluken, Vieta and Kessing30].

For many years, cognitive symptoms in BD have been overshadowed by an almost exclusive focus on depressive and manic symptomatology, leaving them underappreciated despite their significant impact on patients’ lives. Nowadays, cognitive impairments are increasingly recognized as a core feature of BD, persisting throughout the illness, even in the absence of acute mood episodes [Reference Martínez-Arán, Vieta, Reinares, Colom, Torrent and Sánchez-Moreno31]. This growing awareness has led to the development of interventions targeting cognitive functions, yet most treatments focus on neurocognitive domains without specifically addressing AC [Reference Torrent, CdM, Martínez-Arán, Valle, Amann and González-Pinto32–Reference Strawbridge, Tsapekos, Hodsoll, Mantingh, Yalin and McCrone35]. Indeed, evidence on interventions aimed at improving FER in BD remains limited. While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have shown efficacy in enhancing FER in some individuals [Reference Vierck, Porter and Joyce36], results are inconsistent [Reference Samamé, Martino and Strejilevich37]. Similarly, antipsychotics, which are effective in reducing manic symptoms, may indirectly affect FER by impairing eye-gaze movements [Reference Reilly, Lencer, Bishop, Keedy and Sweeney38], which complicate task performance. Our findings, confirming FER impairments in BD, underscore the importance of future research focused on developing treatments specifically targeting domains of AC.

We observed high heterogeneity in nearly half of our results, which can be partly attributed to the neurocognitive variability inherent to BD, as described above. In addition, FER was not uniformly assessed across each study. Different paradigms were used, including the use of facial expressions from multiple atlases, consideration of a varying range of emotions or stimulus durations, or allowing for a trial before task execution. Only 20% of the included studies used facial expressions morphed from neutral or mild intensity to full intensity expressions. This is critical because the International Society of Bipolar Disorder Targeting Cognition Task Force has recommended the use of FER tasks using morphed faces as the gold standard for studying this domain in BD [Reference Miskowiak, Seeberg, Kjaerstad, Burdick, Martinez-Aran and del Mar Bonnin6]. While we believe that such aspects should be controlled upstream, encouraging future studies to use standardized tasks aligned with existing guidelines, we attempted to control this heterogeneity with numerous meta-regressions to identify some important variables in predicting our outcomes.

Among FER task characteristics, we observed that an increased stimulus duration was associated with an increase in the magnitude of differences in correctly identifying facial expressions (SMD from −0.32 to −0.9) or in the speed with which participants provided a response in identifying positive emotions (SMD from 0.37 to 1.42). A brief stimulus duration could pose challenges for both BD patients and HCs in correctly performing a FER task. However, the difficulties experienced by BD patients may be more evident with longer stimulus durations, where issues related to attention or information integration become more apparent. Conversely, studies that did not include a trial before the actual task showed greater differences in identifying facial expressions compared to those that allowed for a preliminary practice (SMD from −0.51 to −0.26). This suggests that the difficulties experienced by BD patients may be partially alleviated through training. Regarding the clinical characteristics of individuals with BD, the severity of manic symptoms was associated with greater difficulty in identifying facial expressions (SMD from −0.35 to −1.02). Patients with more severe manic symptoms exhibit greater distractibility and impulsivity [Reference Vieta, Berk, Schulze, Carvalho, Suppes and Calabrese39], which may explain this finding.

Considering comparisons with FDRs, we did not find significant differences. Although not manifesting the pathology, FDRs share genetic heritage with their family members and thus genetic risk factors. Therefore, our results support the hypothesis that difficulties in AC may constitute an endophenotype of BD [Reference Miskowiak, Seeberg, Kjaerstad, Burdick, Martinez-Aran and del Mar Bonnin6], as observed in previous reports about AC domains such as emotion regulation [Reference De Prisco, Oliva, Fico, Fornaro, De Bartolomeis and Serretti9]. However, studies comparing these two populations are very scarce. Additionally, FDRs of individuals diagnosed with other psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, have also shown FER deficits when compared to HCs [Reference Martin, Croft, Pitt, Strelchuk, Sullivan and Zammit40], raising the question of whether these deficits could be transdiagnostic endophenotypes rather than illness-specific ones [Reference Kjærstad, Søhol, Vinberg, Kessing and Miskowiak41]. Hence, further research is necessary to draw more robust conclusions.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and most comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on FER in individuals diagnosed with BD compared to FDRs and HCs. By synthesizing data from numerous studies conducted across different countries and age groups while controlling for several predictors, our analysis provides comprehensive insights into the challenges faced by individuals with BD in perceiving and interpreting facial expressions. From a clinical standpoint, these findings support a shift toward personalized, multidomain treatment strategies in BD. FER performance should be systematically assessed as part of comprehensive cognitive profiling at baseline and follow-up to identify individuals who may benefit from integrated interventions. The presence of FER deficits in both patients and unaffected FDRs suggests they may represent a cognitive endophenotype of BD, offering a potential biomarker for early identification and risk stratification in clinical settings. The observed association between manic symptom severity and FER impairments further suggests that difficulties in emotion recognition intensify during periods of mood instability, underscoring the importance of monitoring social cognitive functioning when designing individualized treatment plans. By integrating FER assessment into routine cognitive profiling, clinicians can implement more precise treatment sequencing, where mood stabilization serves also as a foundation for subsequent cognitive interventions aimed at improving interpersonal functioning and quality of life. Similarly, our findings offer valuable directions for future research, suggesting specific areas requiring exploration in individual studies. For example, our observation of practice’s positive impact supports the development of targeted interventions aimed at improving cognitive functions. This highlights the potential for tailored interventions considering also the specific deficits identified in our meta-analysis. While various interventions targeting specific domains of AC have been proposed in different populations [Reference Sloan, Hall, Moulding, Bryce, Mildred and Staiger42–Reference Reis, Rossi, de Lima Osório, Bouso, Hallak and Dos Santos44], we believe in a therapeutic approach aimed at enhancing AC as a cohesive whole rather than focusing solely on discrete aspects such as emotion regulation, impulsivity, or reward processing. Additionally, given that these aspects are common even in young people and individuals at risk, we believe that AC should also be integrated into early intervention programs to address vital aspects necessary for individuals’ growth within their social environment.

The present work has some limitations. First, affective state of participants with BD was not always reported, limiting our speculation on the role of affective symptomatology in FER. However, we addressed this aspect through meta-regressions related to both the severity of affective symptomatology and the percentage of individuals in a specific mood state, finding a relationship between the severity of manic symptomatology and the accurate identification of facial emotions. Second, we could not control for the type of pharmacological therapy taken due to the heterogeneity of treatments and the limited availability of information. Medication could serve as an important confounder that limits the generalizability of our results [Reference Ilzarbe and Vieta45], although the majority of our sample was euthymic and likely on stable therapy. Third, individuals with BD often have comorbidities with other psychiatric disorders [Reference Krishnan46], which may influence differences in FER. However, most studies employed (semi)structured diagnostic interviews, enhancing the reliability of reported information. Fourth, although we did not find significant differences between individuals with BD and FDRs, it would be important to compare FDRs with HCs to further test the endophenotype hypothesis. While this comparison was not among the objectives of our study, future research should consider it to provide a better understanding. Fifth, we observed publication bias in some comparisons. Nonetheless, this review searched four databases and used a search strategy without time, language, or age restrictions, maximizing the likelihood of capturing all relevant published studies.

Our analysis provide evidence that people with BD exhibit extensive impairments in FER when compared to HCs, across all emotional categories. These differences are not observed when comparing individuals with BD to their FDRs, suggesting that FER impairments could be considered as an endophenotype of BD. Our findings can guide the development of new treatments for individuals with BD that target AC to enhance cognitive functions, promote social functioning, and improve the overall quality of life.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10147.

Acknowledgements

MDP is supported by the Translational Research Programme for Brain Disorders, IDIBAPS. VO is supported by a Rio Hortega 2024 grant (CM24/00143) from the Spanish Ministry of Health financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-financed by the Fondo Social Europeo Plus (FSE+). GA thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Health financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-financed by the European Social Fund+ (ESF+) (JR23/00050, MV22/00058, CM21/00017); the ISCIII (PI24/00584, PI24/01051, PI21/00340, PI21/00169); the Milken Family Foundation (PI046998); the Fundació Clínic per a la Recerca Biomèdica (FCRB) - Pons Bartan 2020 grant (PI04/6549), the Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (SEPSM); the Fundació Vila Saborit; the Societat Catalana de Psiquiatria i Salut Mental (SCPiSM); and the Translational Research Programme for Brain Disorders, IDIBAPS. DHM’s research is supported by a Juan Rodés JR18/00021 granted by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII). AMu thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI22/00840PI19/00672) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D + I and co-financed by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) and of La Marató-TV3 Foundation grants 202230-31. EV thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI21/00787) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D + I and co-financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III -Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2021-SGR-01358), CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya; La Marató-TV3 Foundation grants 202234-30; the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (H2020-EU.3.1.1. - Understanding health, wellbeing and disease, H2020-EU.3.1.3. Treating and managing disease: Grant 945151, HORIZON.2.1.1 - Health throughout the Life Course: Grant 101057454 and EIT Health (EDIT-B project). JR thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CPII19/00009, PI22/00261) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D + I and co-financed by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III; and the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2021-SGR-01128).

Author contribution

Michele De Prisco: Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. Vincenzo Oliva: Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. Chiara Possidente: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Giovanna Fico: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Laura Montejo: Writing – review & editing. Lydia Fortea: Writing – review & editing. Hanne Lie Kjærstad: Writing – review & editing. Kamilla Woznica Miskowiak: Writing – review & editing. Gerard Anmella: Writing – review & editing. Diego-Hidalgo Mazzei: Writing – review & editing. Alessandro Miola: Writing – review & editing. Michele Fornaro: Writing – review & editing. Andrea Murru: Writing – review & editing. Eduard Vieta: Visualization, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Joaquim Radua: Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

GF has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Angelini, Janssen-Cilag and Lundbeck. HLK has received honoraria from Lundbeck. GA has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Lundbeck/Otsuka, Rovi, and Viatris, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. DHM has received CME-related honoraria and served as consultant for Abbott, Angelini, Ethypharm Digital Therapy and Janssen-Cilag; MF received honoraria from the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) for his speaker activities, and from Angelini, Lundbeck, Bristol Meyer Squibb, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. AMu has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: Angelini, Idorsia, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Takeda, outside of the submitted work; EV has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, AbbVie, Angelini, Biogen, Biohaven, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celon Pharma, Compass, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Idorsia, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medincell, Neuraxpharm, Newron, Novartis, Orion Corporation, Organon, Otsuka, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris, outside the submitted work; JR has received CME-related honoraria from Adamed, outside the submitted work.

All the other authors have no conflict to declare.

Open practices statement

The dataset used for this research is available on request.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT to improve readability and language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.