Introduction

Coins constitute an important category of material culture recovered from ancient transcontinental ports. Both indigenous and foreign pieces have been discovered, as stray finds or in hoards, lost or deposited in religious buildings, graves, and residential structures. When studied in context they can tell hugely interesting stories of daily life in the international emporia and of the social give and take between residents and visitors.Footnote 1 Excavations at Berenike and Myos Hormos (modern Quseir al-Qadim), the key ports of the Roman branch of Indian Ocean trade, have contributed significantly to this field of research. Archaeological projects conducted at the two Egyptian sites have yielded an abundance of objects used by their residents. The coins, however, while forming an important part of this material, have been used mostly to examine the ebb and flow of trade, and the major actors in the Mediterranean world who played a part in the global trade passing through these two emporia.Footnote 2 Discussion has pertained to the circumstances that might explain the relative dearth of foreign coins at Berenike,Footnote 3 and issues related to the monetization of Roman Egypt under the Flavian emperors have been dealt with briefly based on finds from two destination ports in the province: Alexandria and Berenike.Footnote 4 Despite meticulous documentation and cataloguing, there has been no comprehensive discussion of coin distribution and its implications for reconstructing everyday transactions in the harbors across various periods of operations.Footnote 5

This paper is a pioneering attempt at a contextualized examination of published coin finds from the Red Sea ports. Concentrating on the archaeological contexts of these finds, which include a variety of botanical and zoological data as well as epigraphic sources mentioning monetary transactions and the story of trade as told by the ubiquitous ceramics, provides the background for a first-ever exploration of the role that coins actually played in the everyday dealings of the ports’ residents. In this sense, the paper expands the study of archaeological coin finds to include not only the economic but also the social history of the ancient port communities. The study’s aims are accomplished by observing significant trends in the relationship between the coins and the non-numismatic evidence found at these sites of exchange and transaction. On this basis, a hypothetical framework is then proposed for the everyday dealings presumed to have taken place at the Berenike and Myos Hormos emporia.Footnote 6

Evidence suggests that coinage served as a means of payment throughout all periods of activity at the Red Sea ports, though the degree of monetization and the contexts of coin usage likely varied significantly over time. To better understand this topic, detailed studies of coin use during specific periods are essential. This paper, therefore, focuses on the question: how were coins used in Berenike and Myos Hormos during the Roman period? It covers coins referred to as “Roman provincial coinage for Egypt” or “Alexandrian,” encompassing issues from the reign of Augustus to the reign of Diocletian. During the rule of the latter, the currency of the Roman Empire became more standardized and was produced across a network of imperial mints.

The Alexandrian coinage consisted of billon tetradrachms and smaller bronze denominations, issued at a centralized mint in Alexandria.Footnote 7 The Romans maintained the closed currency system they inherited from Ptolemaic Egypt, likely as a means of generating revenue, until the reforms of Diocletian. Hence, only coins issued in Alexandria could be used within the province. The implication is that “foreign” coins, that is, coins from external sources, needed to be exchanged for the “Egyptian” currency of the time.Footnote 8 The question of whether imperial gold circulated in Egypt remains difficult to settle. Recently, Howgego hypothesized that the influx of Dacian gold might have driven an increase in the use of gold coin in Egypt during the Antonine period. This change might also have been connected with a whole range of reforms relating to the mint in Alexandria in 162/3 CE.Footnote 9

Ports and coin finds

Berenike and Myos Hormos were vibrant harbor towns in the Eastern Desert, located on the western shore of the Red Sea (Fig. 1). The site of Berenike (Troglodytika) lies approximately 825 km south-southeast of Suez and 260 km east of Aswan. Myos Hormos is located about 8 km north of the modern town of Quseir and about 500 km south of Suez. Both ports of trade appear in various ancient texts including the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, the mid-1st c. CE guide to trade and navigation in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 10 They were connected to Koptos, a gateway to the desert, by a system of caravan routes lined with fortlets (praesidia) that were built and controlled by the Roman army and provided travelers with water, rest, and protection.Footnote 11

Fig. 1. Sites mentioned in the text.

Berenike was founded by Ptolemy II Philadelphus in the third quarter of the 3rd c. BCE to ensure constant access to African elephants. In Hellenistic times, it was a strongly fortified outpost where soldiers were stationed.Footnote 12 After the annexation of Egypt by Augustus in 30 BCE, Berenike became primarily an imperial harbor engaged in international maritime trade, connecting the Roman Empire with India, Arabia, and the African coast. The third and final phase of Berenike’s vibrant economy began in the mid-4th c. CE, in post-Roman times, after Diocletian withdrew the Roman forces from the Dodekaschoinos to Syne (modern Aswan) in 298 CE.Footnote 13 Recent discoveries from Berenike and the wider region show that between the 4th and the 6th c. CE, the port was controlled by the Blemmyes.Footnote 14 The first systematic excavations of Berenike were jointly conducted by teams from the Universities of Delaware and Leiden between 1994 and 2001, led by Steven Sidebotham and Willeke Wendrich.Footnote 15 After a short break, in 2008, a Polish-American team from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, the University of Warsaw, and the University of Delaware restarted excavations at the site. Until mid-2025, the Berenike Expedition was co-directed by Mariusz Gwiazda and Steven Sidebotham. Thereafter, the University of Delaware was replaced by Heidelberg University as an institutional partner of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, and the expedition is currently directed by the author together with Rodney Ast (Heidelberg University).Footnote 16

The archaeological sequence from Myos Hormos is shorter than Berenike’s. During the Roman period, the port was occupied from the late 1st c. BCE until the 3rd c. CE; however, it cannot be excluded that the town had already been founded by the Ptolemaic period.Footnote 17 Together with Berenike, Myos Hormos played a crucial role in supporting the ancient Indian Ocean trade. The second phase of the site’s occupation was during the Islamic period, under the Mamluk rulers. The most important excavations of Myos Hormos were conducted by two teams: the first excavated at the site in 1978, 1980, and 1982, and was led by Donald Whitcomb and Janet Johnson, supported by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago;Footnote 18 then, between 1999 and 2003, five seasons of survey and excavations were conducted by the University of Southampton under the direction of David Peacock and Lucy Blue.Footnote 19

The total number of coins discovered in Berenike between 1994 and 2020 exceeds 900, and many thousands more must still await recovery.Footnote 20 The published corpus contains 586 specimens that were found during the campaigns that took place between 1994 and 1999/2000 and in 2009, and discovered in the animal cemetery/trash dump area after 2009.Footnote 21 Of these coins, 16 (2.8%) are Ptolemaic, 180 (30.7%) are Roman provincial issues of the Alexandria mint (Fig. 2), and 115 (19.6%) are Late Roman. Only 3 coins (0.5%) were foreign issues, and another 3 (0.5%) were imitations of Late Roman bronzes. Two hundred and sixty-nine specimens (45.9%) cannot be identified. One hundred and fifty-four of the coins (26.3%) were surface finds, and the rest (432 = 73.7%) were discovered during excavations. The spoil of each context at Berenike was sieved to prevent coins from being overlooked; therefore, we can be certain that coins recovered from the trenches are a representative sample of coins deposited.

Fig. 2. Berenike: the density of Roman provincial coin finds, spatial distribution.

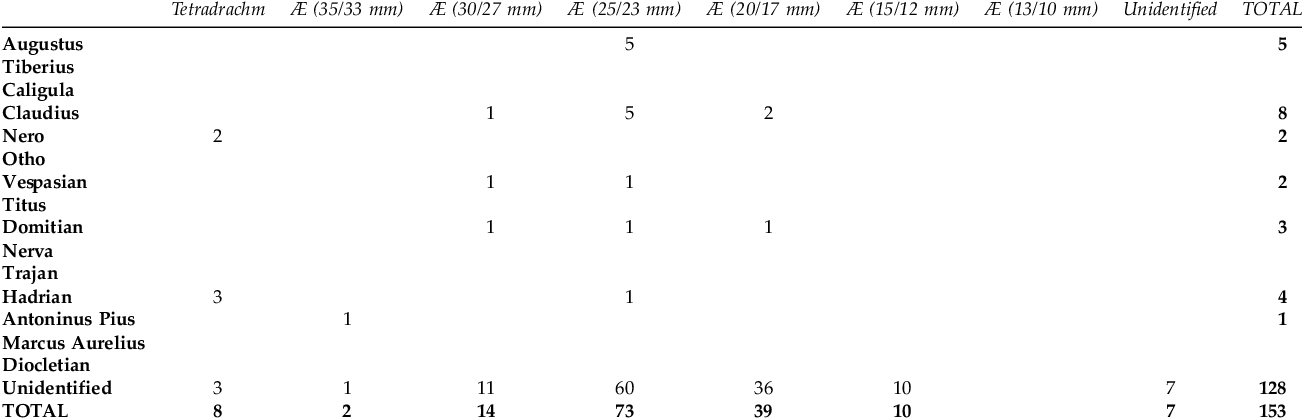

Fewer coins were found in Myos Hormos due to the fact that this site was less extensively excavated. Excavations by the team from the University of Chicago in 1978, 1980, and 1982 unearthed 153 coins and one lead token.Footnote 22 The total number of coins discovered during the University of Southampton’s excavations is unknown, since only 14 coins were published.Footnote 23 Within the corpus of coin finds from the site, 4 (2.4%) are Ptolemaic, 153 (91.6%) are Roman provincial issues of the Alexandria mint (Fig. 3), and 10 (6%) are non-Roman/possible Islamic/possible coins/flans. Most of the coins (155 specimens, 92.8%) came from excavations, and only 7 (4.2%) were surface finds. For five coins (3%), the find contexts were not recorded.

Fig. 3. Myos Hormos: the density of Roman provincial coin finds, spatial distribution.

Everyday transactions: non-numismatic evidence

Evidence from both textual and archaeological sources indicates that Roman Red Sea ports such as Berenike and Myos Hormos were part of a highly monetized economy. Papyri from Roman Egypt show widespread use of coinage in daily transactions – alongside rents, wages, taxes, and credit – even at the village level. Barter was minimal, though payments in kind occasionally supplemented coin use.Footnote 24

Of particular relevance to Indian Ocean trade was the 25% tetarte tax levied on both imports and exports at Koptos, rather than at the ports themselves. Merchants also incurred tolls along the desert caravan routes. In addition, documents refer to the quintana, a commercial levy imposed at various Eastern Desert outposts, including Berenike, and always recorded in monetary terms.Footnote 25 A local tax list from Berenike further attests to dues assessed both in coin and in kind.Footnote 26 A bank in Berenike is mentioned on an ostrakon from the site, which is a receipt for the delivery of water.Footnote 27 There is abundant evidence from Egypt for banks, including private ones, even in villages.Footnote 28

Essential goods available in Berenike, many of them imported from the Nile Valley and beyond, included food, water, and animal fodder.Footnote 29 A network of caravans and donkey drivers supplied these necessities, as evidenced by archives of ostraka from the desert stations. Regular requests for food and supplies from the Nile Valley and desert outposts appear in private letters from Berenike. These goods arrived via caravan or were purchased from donkey drivers and wagons traversing the desert routes.Footnote 30

Evidence of a monetized economy comes from the sites themselves; for example, a street discovered at Myos Hormos lined with shops and terminating with a bakery. In many cases, residents lived and worked in the same premises, engaging in production and trade.Footnote 31 No trace has yet been found of periodic markets, but they were widespread in the Roman EmpireFootnote 32 and are to be expected.

Wheat was the primary staple consumed in the ports, often arriving pre-processed as flour or bread.Footnote 33 Bread was also baked locally, as shown by Myos Hormos bakery.Footnote 34 Protein-rich foods came mainly from the Nile Valley, though some were sourced from the Red Sea. High-status residents in Berenike may have eaten imported escargots, likely from France or Italy.Footnote 35 Botanical evidence indicates the consumption of imported fruits, pulses, herbs, spices, nuts, oil-rich seeds, vegetables, and cereals at both ports.Footnote 36 Wine, olive oil, and fish sauce – typically transported in amphoras – were imported in large volumes, with some goods that were originally intended for export also reaching parts of the Berenike population.Footnote 37 Another commodity that must have been available for purchase was animal fodder.Footnote 38

Imported timber was likely required for ship repairs, while Berenike’s fuel wood mainly came from local trees and recycled ship’s timber. The discovery of Nile acacia at Myos Hormos indicates fuel imports from the Nile Valley; ready charcoal may have also been brought in.Footnote 39 A large archive of 1st-c. CE ostraka from Berenike records water deliveries from nearby inland sources, highlighting the Roman military’s control over water supply and distribution in the city.Footnote 40

Legally or not, money likely changed hands at the ports for commodities imported via Indian Ocean trade, such as black pepper, which is found throughout Roman layers at Myos Hormos and Berenike.Footnote 41 In Berenike, some peppercorns appear in ritual contexts, while others were found in domestic areas linked to food preparation and consumption.Footnote 42 An ostrakon from Myos Hormos records a request for pepper, and additional evidence from Didymoi and Mons Claudianus confirms its broader use.Footnote 43 Some of this pepper may have circulated tax free, reaching inland sites directly from Berenike, where it had been purchased from its importers from India.Footnote 44 However, taxation on eastern goods at Berenike and Myos Hormos, to facilitate their acquisition in the local markets, cannot be ruled out.Footnote 45

There is also evidence of frankincense being purchased at the desert outports. Private letters from Berenike mention bdellium – a resin used in aromatics and medicine – and myrrh, indicating that Indian Ocean imports were sold in the ports.Footnote 46 The importers likely sold surplus goods for cash, which could then be used by them for daily needs or ship repairs. Beads made from a variety of materials must have also been available for purchase, whether as imported goods or as objects made for the local market.Footnote 47 The discovery of gem blanks from India and Sri Lanka suggests that some of these may have been sold at Berenike. Beads crafted locally from imported semi-precious stones have also been found. Roman layers at Berenike yielded beads that were likely imported from India, as well as from Persia, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Black Sea region.Footnote 48 Indo-Pacific glass beads have also been discovered in Myos Hormos.Footnote 49 Beads found at Berenike and made from emeralds sourced at Mons Smaragdus were likely intended for local use or export to Africa. Red Sea coral, believed to protect against maritime hazards, may have been sold at both ports in the form of amulets.Footnote 50

A papyrus from Berenike records the sale of a donkey and its saddle for 160 drachmas, with the seller explicitly acknowledging receipt of the sum in cash.Footnote 51 Another document appears to be an agreement or receipt, possibly related to beer. A papyrus from Myos Hormos documents a loan of 200 drachmas, with the agreement written and the funds disbursed there in 93 CE.Footnote 52

Crafts and service industries in both ports also engendered payments in cash. Ship building, maintenance, and repair was the main industry, as attested by a variety of archaeological evidence.Footnote 53 An ostrakon from Krokodilo mentions the transport of wood for shipbuilding in Myos Hormos,Footnote 54 while a 90 CE tariff from the Koptos tollhouse lists various shipbuilding professions – and suggests their members were well compensated, given the high taxation rates.Footnote 55 An ostrakon from Berenike mentions payments for a boat and for an assistant or assistance, probably in a nautical context, e.g., for the assistant shipbuilder.Footnote 56 Other workers who were probably paid in coin for their labor and services included those involved in loading and unloading ships, seasonal sailors, and craftsmen, as well as prostitutes, who are reported to have traveled from Koptos.Footnote 57

Other services were also available to port residents or visitors. An ostrakon from Berenike confirms the presence of a men’s barber shop, while another lists a general merchant, a goldsmith, and a lead worker.Footnote 58 A thriving small-scale industry in both ports utilized materials such as mother-of-pearl, semi-precious stones, turtle shell, hippo tusk, and Indian elephant ivory. At Myos Hormos, stone molds for jewelry production suggest the presence of a local workshop crafting ornaments.Footnote 59

Religious practices also entailed expenses. At least two religious buildings – the Isis temple and the Shrine of the Palmyrenes – were active in Berenike during the Roman period. Their upkeep depended on contributions from both local and foreign patrons.Footnote 60 Civilians and military personnel alike paid homage to the deities worshipped in the port, as evident from surviving stone inscriptions.Footnote 61 These, along with sculptures, were likely commissioned from a local atelier.Footnote 62 Foreign merchants and visitors also availed themselves of the services of local workshops when dedicating inscriptions or statues in the local temple.Footnote 63

Religious festivals likely entailed additional costs. An ostrakon from Berenike records one Herennios purchasing a large quantity of roses – possibly for a ritual – and expressing concern over an unspecified number of cats, perhaps also intended for religious purposes.Footnote 64 As protector of sailors, Isis was venerated across the Mediterranean during the Navigium Isidis, a festival marking the annual reopening of sea routes. A similar ceremony may have occurred in Berenike during the Red Sea sailing season, though direct evidence is lacking.Footnote 65 Fragments of mica inscriptions from Myos Hormos are likely ex-voto dedications for safe travel, and a figurine of the Sothic dog – representing Sirius, the navigation star – was found in the harbor.Footnote 66 Terracotta figurines of deities, used domestically or as votive offerings, were probably sold at temples after being imported from the Nile Valley, as suggested by figurines made of Nile silt found at Myos Hormos and Berenike.Footnote 67

Transactions evidenced by coin finds

Assessing coin use and monetization in the Roman Red Sea ports on the basis of coin finds requires careful consideration of the methodological challenges specific to Roman Egypt. A central principle in numismatic scholarship is to identify regional circulation patterns prior to interpreting site-specific assemblages. Foundational work by Richard Reece and P. John Casey,Footnote 68 particularly the “Reece period analysis” and the concept of the “British Mean,” have played a central role in shaping current methodologies by organizing coin finds into standardized chronological distributions and facilitating a clearer understanding of individual site assemblages in relation to broader regional trends. Scholars have continued to refine and expand upon Reece’s original methodology, applying it in increasingly nuanced ways to interpret coin data across diverse archaeological and chronological contexts.Footnote 69

However, applying such models in the context of Roman Egypt presents several difficulties. Chief among them is the limited publication of site finds, which hinders the establishment of reliable regional patterns. While coin hoards have been systematically documented for decades, site-level evidence remains scarce and fragmentary.Footnote 70 Christiansen’s survey of 4,623 recorded specimens highlights this issue, and he notes that “the evidence is so meagre that it does not warrant too firm conclusions, unless substantiated by other evidence.”Footnote 71 Although additional data exist from individual sites,Footnote 72 much material remains unpublished, often lacking provenance and stored in museum collections across Egypt.Footnote 73

Inconsistencies in reporting further complicate analysis. Coin finds are frequently presented without archaeological context,Footnote 74 or selectively included based on legibility.Footnote 75 This is evident in the publication of coin material from Myos Hormos, where only 14 coins from the 1999–2003 excavations were deemed sufficiently identifiable to warrant inclusion.Footnote 76 As Soto Marín has rightly pointed out, many coins are dated only broadly due to poor preservation and the lack of contextual detail in older excavation records. As a result, these coins often cannot be confidently attributed to specific reigns or years, posing challenges for their incorporation into chronological distribution models aimed at inter-site comparison. These limitations are particularly acute at Berenike and Myos Hormos, where the condition of the coins often precludes precise dating or attribution to individual emperors. Soto Marín also observes that while comparative methods developed for Roman Britain offer some utility – especially for analyzing Late Roman coinage – their more general application to Egypt is constrained. The province’s closed currency system and reliance on provincially issued coinage during the first three centuries CE limit direct comparability with other regions of the empire.Footnote 77

Despite these constraints, some broad interpretative conclusions can be drawn. It is believed that coins were commonly used by urban and rural dwellers of Roman Egypt for everyday transactions.Footnote 78 However, patterns of coin use appear to have varied locally.Footnote 79 In this context, material from Koptos and the Eastern Desert may offer a valuable comparative framework for analyzing coin finds from the Red Sea ports.

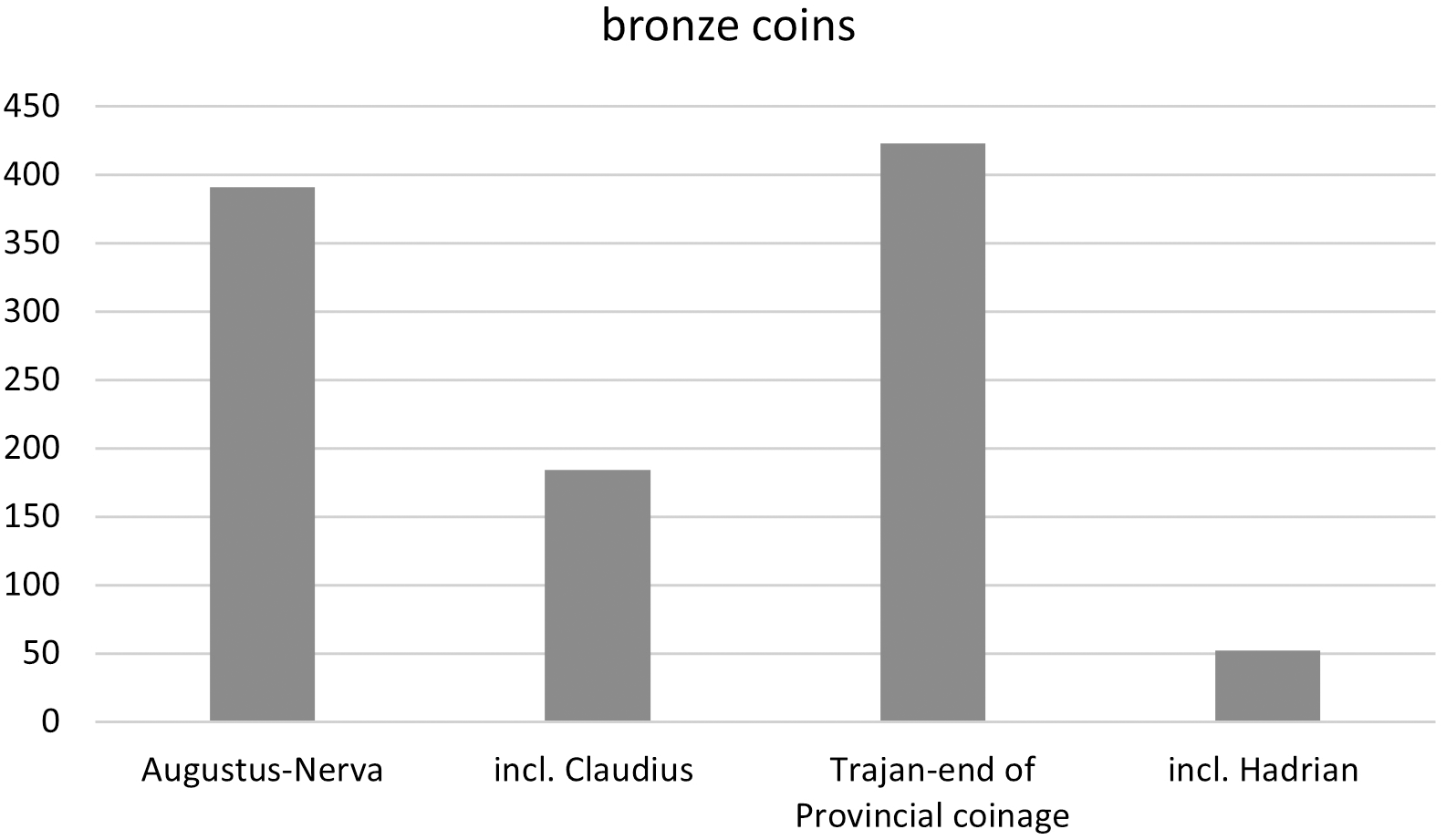

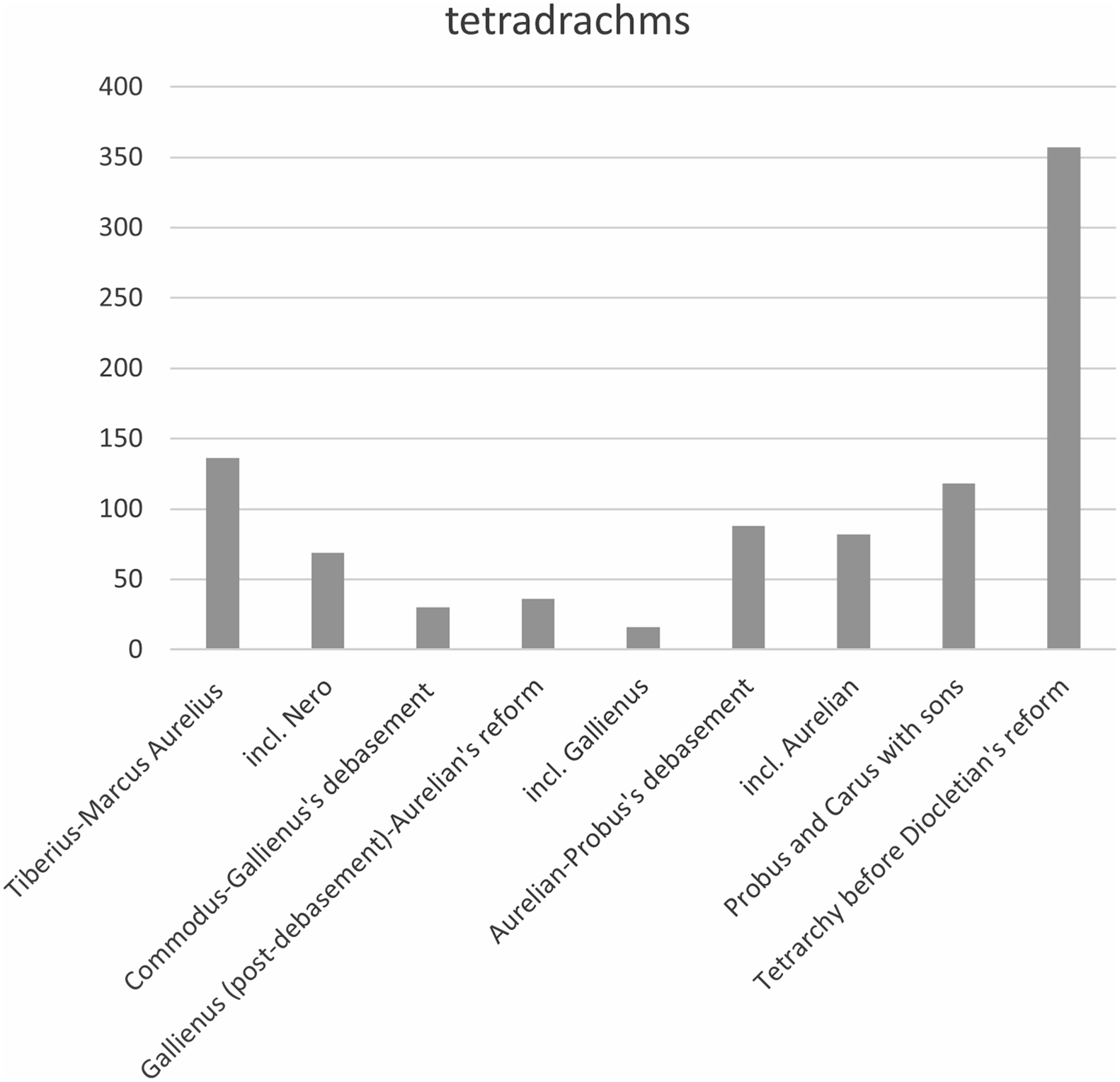

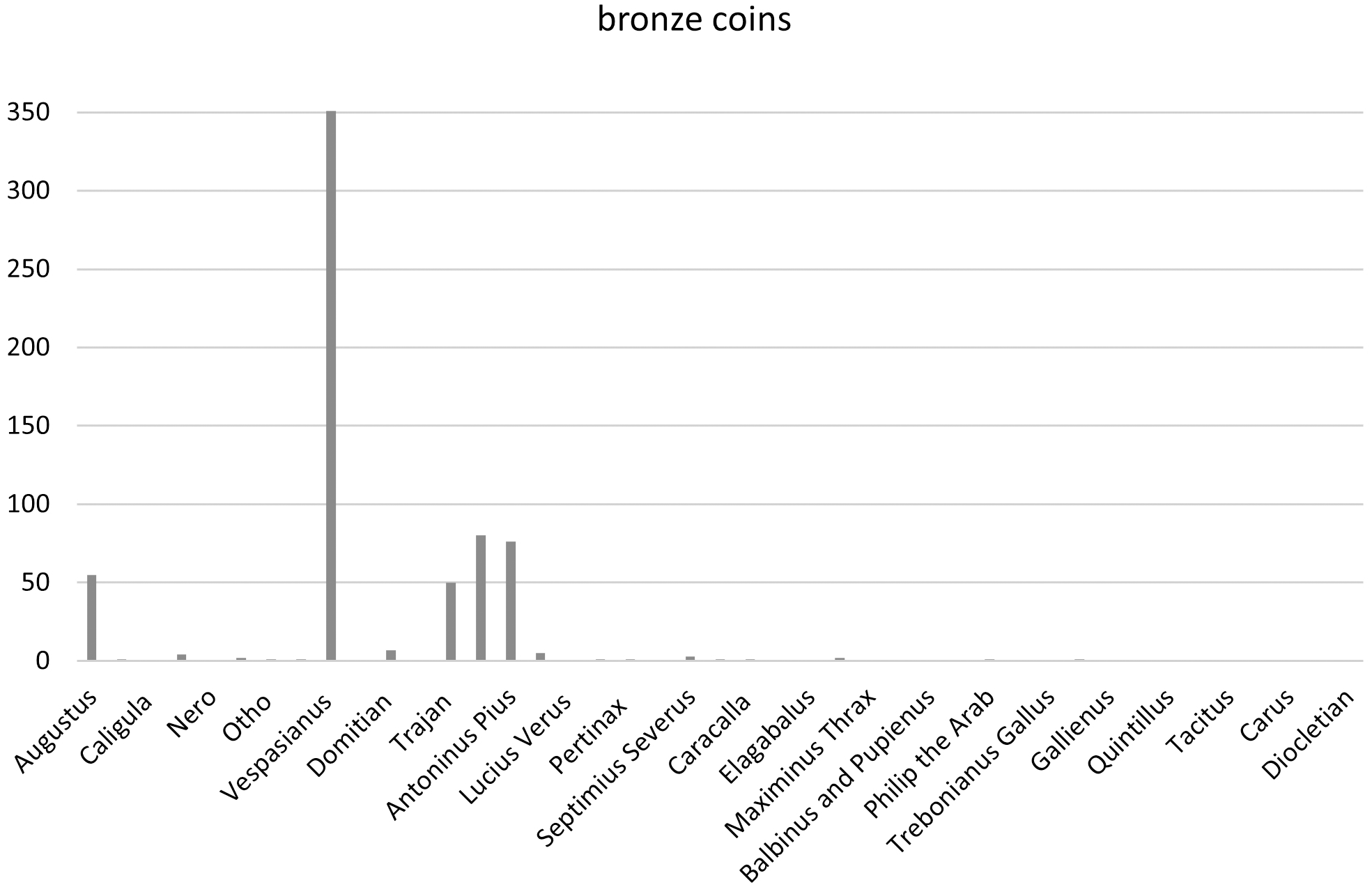

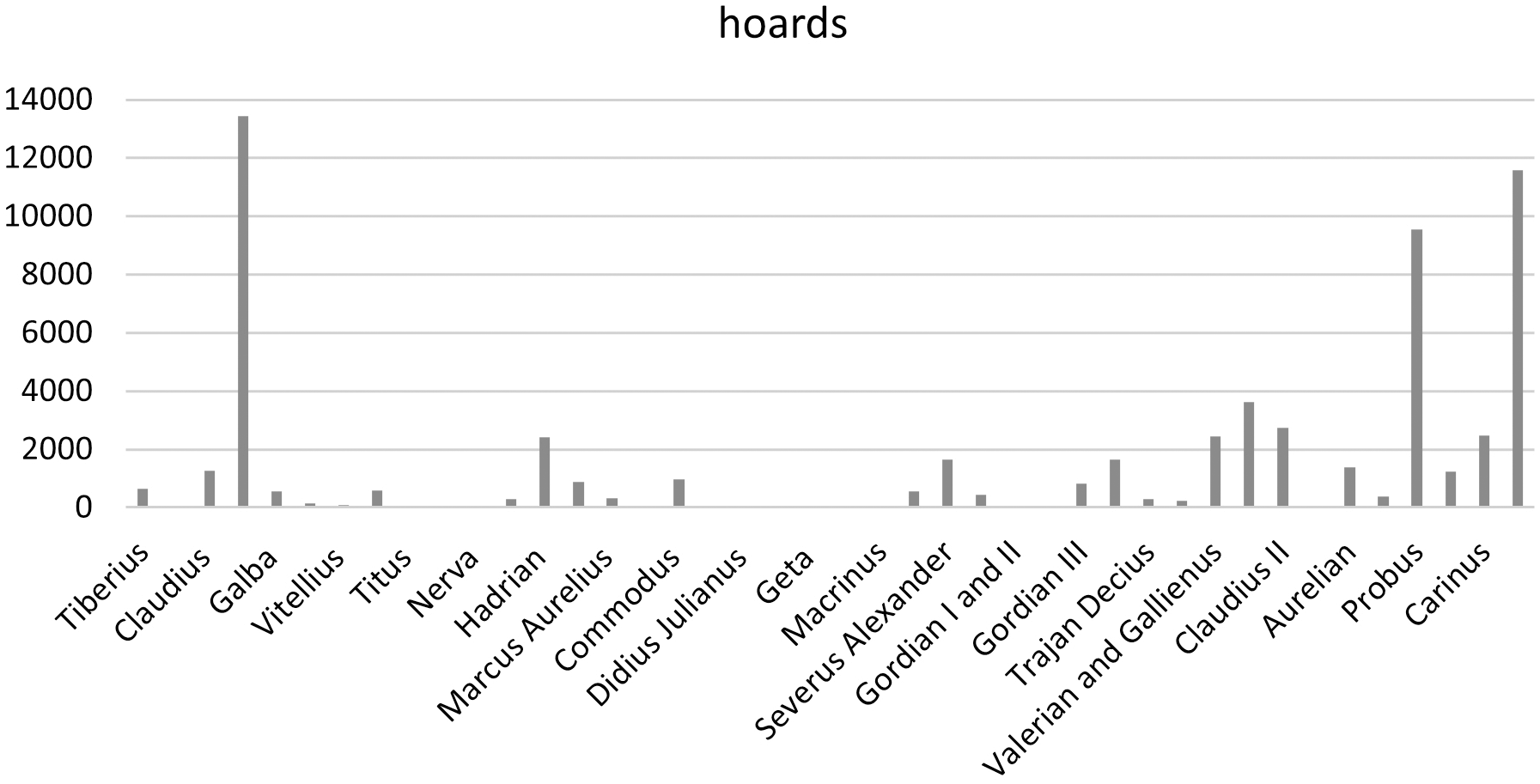

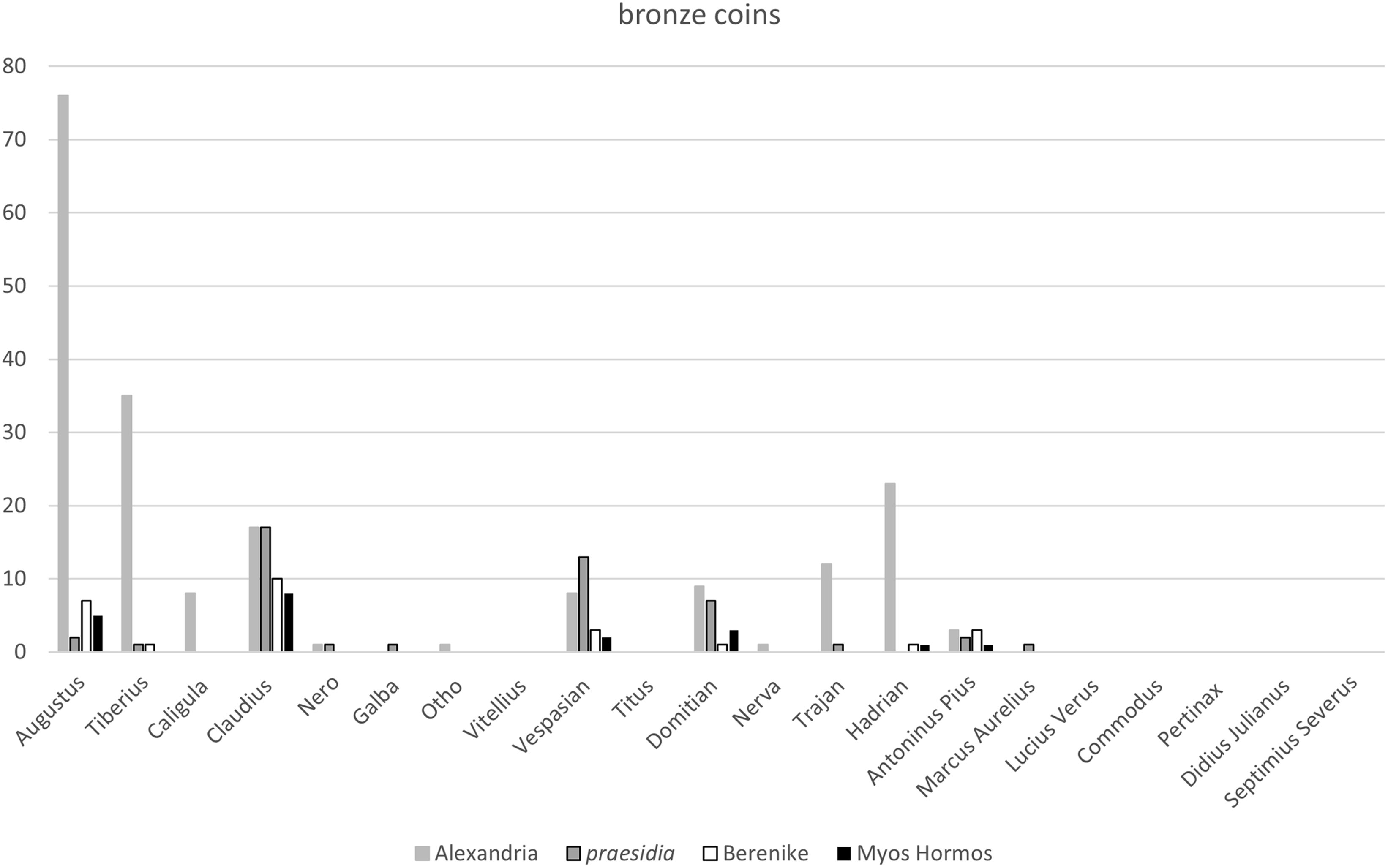

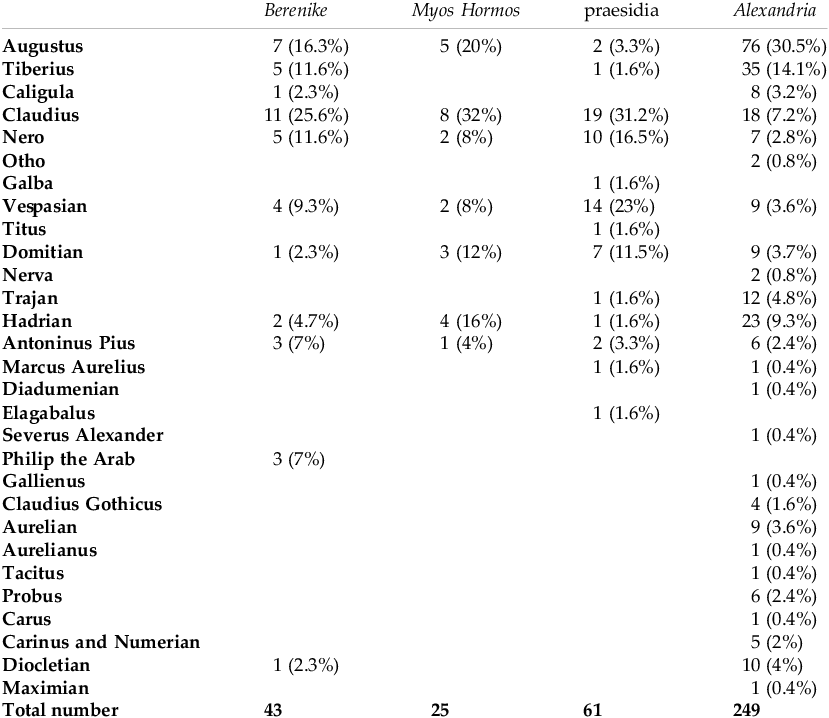

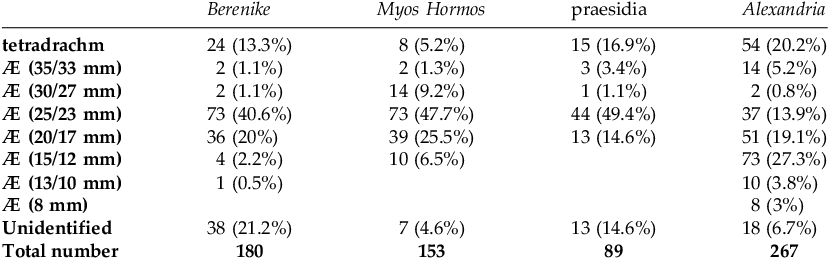

Unfortunately, meager publication of the Koptos material – apparently only 13 coins, including five Alexandrian issues, were recovered from six years of excavations by a joint team from the University of Michigan and the University of AsyutFootnote 80 – makes this dataset insufficient to be included in the comparison. By contrast, the numismatic corpus from excavations carried out at the praesidia of the Eastern Desert under the auspices of IFAO comprises 89 Roman coins of various denominations and provides a more meaningful point of comparison.Footnote 81 Chronological patterns observed at the Red Sea ports can also be tentatively compared with Christiansen’s catalog of stray finds (Figs. 4 and 5), as well as with coin hoards discovered across Roman Egypt (Figs. 6 and 7).Footnote 82 Among site-specific datasets, the assemblage from Alexandria remains the most pivotal. Of the 3,529 coins that have been published, 267 date from the Roman period up to the Diocletianic reform of 294/295 CE.Footnote 83 This dataset will also be employed as a key comparative reference for analyzing coin circulation patterns at Berenike and Myos Hormos (Figs. 8 and 9; Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 4. Chronological distribution of bronze coin stray finds (Christiansen Reference Christiansen2006).

Fig. 5. Chronological distribution of tetradrachm stray finds (Christiansen Reference Christiansen2006).

Fig. 6. Chronological distribution of bronze coin hoard finds. (Chart by the author, based on data from https://chre.ashmus.ox.ac.uk.)

Fig. 7. Chronological distribution of tetradrachm coin hoard finds. (Chart by the author, based on data from https://chre.ashmus.ox.ac.uk.)

Fig. 8. Chronological distribution of bronze coin finds from Alexandria and Eastern Desert sites – a comparative overview. (Chart by the author, based on data from Cuvigny and Lach-Urgacz Reference Cuvigny, Lach-Urgacz and Faucher2020 and Picard Reference Picard, Picard, Bresc, Faucher, Gorre, Marcellesi and Morrisson2012.)

Fig. 9. Chronological distribution of tetradrachm coin finds from Alexandria and Eastern Desert sites – a comparative overview. (Chart by the author, based on data from Cuvigny and Lach-Urgacz Reference Cuvigny, Lach-Urgacz and Faucher2020 and Picard Reference Picard, Picard, Bresc, Faucher, Gorre, Marcellesi and Morrisson2012.)

Table 1. Chronological structure of datasets from Eastern Desert and Alexandria.

Table 2. Denominational structure of datasets from Eastern Desert and Alexandria.

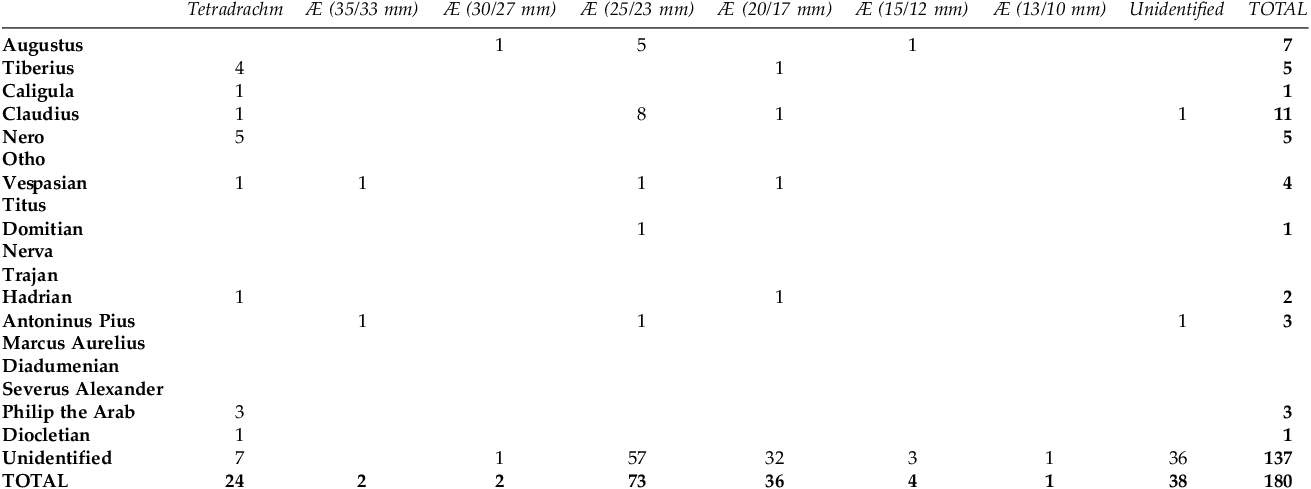

The number of attributable coins from Berenike and Myos Hormos is very low (Tables 3 and 4). Acid sand and higher salinity in the deeper layers are not conducive to metal preservation. Moreover, many of the coins are heavily worn due to long use. Only 43 Roman coin finds from Berenike (23.8% of those published) can be assigned to particular emperors. Myos Hormos yielded only 25 attributable specimens (16.3%). These attribution ratios are responsible for the limited and preliminary nature of the conclusions below but, even so, the chronological distributions of the datasets from Myos Hormos and Berenike are clearly similar.

Table 3. Chronological and denominational distribution of published coins from the Berenike excavations.

Table 4. Chronological and denominational distribution of published coins from the Myos Hormos excavations.

Bronze coins from the 1st c. CE dominate the assemblages at Berenike (69%) and Myos Hormos (65%), especially those of Claudius (38% in Berenike; 40% in Myos Hormos) and Augustus (27% in Berenike; 25% in Myos Hormos). Claudian issues are also most common in the Eastern Desert praesidia (37%), while Augustan issues are comparatively rare (4%), with Julio-Claudian coins overall representing 46% of the assemblage. This distribution reflects the extensive production at Alexandria mint during the reigns of Augustus and Claudius, followed by a notable, though reduced, output under Nero.Footnote 84 Interestingly, while the predominance of Augustan coins is well supported by hoard finds, a similar dominance of Claudian issues is not. Instead, a high frequency of Claudian coins has been observed among stray finds.

Alexandrian excavations present a different picture: Augustan and Tiberian coins together account for the majority of provincial issues (44.66%), with Augustus at 30.54%, Tiberius at 14.12%, and Claudius significantly less well represented at 7.29%. Overall, Julio-Claudian coins comprise 57.80% of the sample, despite the reduced production during Tiberius’s and Caligula’s reigns.Footnote 85

Bronze coinage was regularly minted during the reign of Vespasian, though production appears to have declined in some years and likely ceased around 77 CE. Minting resumed under Domitian, but there is no evidence of bronze coinage issued during the reign of Titus.Footnote 86 Flavian coins constitute the second largest group in the praesidia (43%) but appear in lower proportions at the ports (15% in Berenike; 25% in Myos Hormos) and Alexandria (9%). This peak in Flavian-period coinage is also reflected in hoard evidence. However, the apparent predominance of Vespasianic issues is largely attributable to a single hoard, from which 87% of the identified Flavian coins derive.Footnote 87

Denominations of 25 and 20 mm remained the most frequently minted during the Flavian period, consistent with the trends of the Julio-Claudian era.Footnote 88 Those two denominations are also the most frequently found in both the ports and the praesidia. Cuvigny and Lach-Urgacz attribute the prevalence of Æ 25/23 mm coins in the praesidia to their abundant production and the fact that they tended to be easily lost. They also suggest that given the higher prices in the Eastern Desert, these must have been the coins most often exchanged in everyday transactions.Footnote 89 In contrast, excavations in Alexandria indicate a greater supply of smaller denominations, particularly during the early 1st c. CE.Footnote 90

In the 2nd c. CE, Alexandrian minting became more regular, especially under Hadrian.Footnote 91 Coins of the Antonine dynasty are attested at Eastern Desert sites (15% for Berenike; 10% for Myos Hormos; 9% for praesidia; 20% for Alexandria) and represent the final bronze coinage phase. This increase is reflected in both hoard and stray finds. By contrast, Severan coins are rare, even in coin hoards. Coin production during the reign of Septimius Severus was notably low, and it appears to have ceased entirely under Caracalla.Footnote 92

Turning to silver coinage, the minting of tetradrachms during the Julio-Claudian period was substantial, beginning under Tiberius, expanding under Claudius, and peaking with Nero.Footnote 93 This trend is reflected in finds from Berenike, where tetradrachms of Nero (29%) and Tiberius (24%) are the most commonly represented. The high output under Nero is further evidenced by finds from Myos Hormos (40%) and the Eastern Desert praesidia (60%) and is corroborated by both hoard discoveries and stray finds.

In contrast, silver coin production during the Flavian period was limited, a pattern also reflected in the hoard evidence.Footnote 94 Only two Flavian tetradrachms are known from the praesidia and two from Alexandria, with a single specimen recovered from Berenike. No Flavian silver coins have been identified at Myos Hormos.

In the 2nd c. CE, Alexandrian coinage became more standardized and less sporadic. The production of silver coins was low under Trajan but increased during Hadrian’s reign, as evidenced by both stray finds and hoard assemblages.Footnote 95 This increase is also observable at Eastern Desert sites, though not in Alexandria, where tetradrachms of Hadrian are absent from the archaeological record. In contrast, at Myos Hormos, Hadrianic tetradrachms represent 60% of all tetradrachm finds, compared to only 6% at Berenike and 1% in the praesidia.

The volume of coins declines significantly from the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus onwards, deteriorating even further during the Severan dynasty and eventually leading to the closure of the mint during the reign of Caracalla. A gradual recovery began under Elagabalus and continued more substantially under Severus Alexander, as confirmed by coin hoards and other numismatic evidence.Footnote 96 In the Eastern Desert, this period is currently represented by only a single tetradrachm of Elagabalus from Didymoi. From Alexandria, only one specimen – of Severus Alexander – has been identified.

The archaeological record from the Eastern Desert presents a markedly different picture for the period following the Severan dynasty. Coin issues dated between the end of the Severan line and the Diocletianic reform are almost entirely absent, with only four specimens identified at Berenike. In contrast, coins from this period are well represented in Alexandria, as well as in hoards and stray finds, likely reflecting both increased output from the Alexandrian mint and patterns of hoarding during periods of crisis.Footnote 97

The structure of coin finds from the ports and praesidia can likely be attributed, at least in part, to the rhythms of the Alexandria mint, particularly for the 1st-c. CE issues. In the Eastern Desert, coins from the 2nd c. CE are limited. In contrast, the peak in the chronological distribution of bronze coin finds from the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian is significantly more pronounced in the Alexandrian assemblage. The most striking discrepancy between the dataset of the Eastern Desert and those of both Alexandria and the broader coin hoard and stray finds is the scarcity of 3rd-c. CE coins in the desert region.

Berenike and Myos Hormos experienced an initial peak in prosperity from the 1st to mid-2nd c. CE. Archaeological research indicates abandonment or disuse in numerous areas of Myos Hormos from the 2nd c. CE onwards. It was long assumed that Berenike likewise saw a significant decline in activity during the second half of the 2nd c. CE, particularly due to the scarcity of 3rd-c. CE material in the archaeological record;Footnote 98 however, the recent discovery of inscriptions dated to the 3rd c. CE has significantly revised this view, confirming that the port remained active throughout that period.Footnote 99

According to Cuvigny and Lach-Urgacz, the scarcity of 3rd-c. CE coins in the praesidia is best explained by the predominance of billon tetradrachms minted at Alexandria during this time – a denomination less prone to loss – and the continued reliance on older bronze coinage for everyday transactions.Footnote 100 Excavations at Dios and Xeron Pelagos support this view, with Claudian coins remaining in circulation into the 3rd c. CE. Faucher similarly cautions against the overly narrow dating of small hoards, emphasizing the potential for long-term coin circulation.Footnote 101 Provincial coins found in post-284 CE layers at Kom al-Ahmar have led Asolati and Crisafulli to propose that earlier issues were reused into the 4th and even 5th c. CE, owing to their similarity in size and metal content to later coins.Footnote 102

Thus, the question of which coins were in circulation in the Eastern Desert differs from that of how long individual issues remained in use. It is also reasonable to infer a correlation between the degree of coin wear and the intensity of use.Footnote 103 In fact, heavy wear observed on finds from Berenike and Myos Hormos suggests long circulation, perhaps through the 3rd c. CE. Nevertheless, as noted, the 3rd-c. CE coins are well represented among stray finds and in the Alexandrian dataset. Consequently, whether the composition of the coin pool at the ports reflects broader imperial monetary policy or local economic preferences remains an open question.

Ultimately, the scarcity of 3rd-c. CE coin finds in Berenike can no longer be explained by site decline. It is more likely that coins simply stopped arriving into the region for reasons that are not yet fully understood. A satisfactory explanation must await a more comprehensive understanding of coin circulation patterns in Roman Egypt.

Finally, the distinct chronological and denominational profile of Alexandrian coin finds suggests that coins found at the Eastern Desert sites may not have circulated previously in the capital. The Berenike local market catered to both regional consumers and Roman soldiers, whose presence in the port has been confirmedFootnote 104 and who would have been in possession of newly minted coins received as pay.Footnote 105 The same would have been true at Myos Hormos, where the presence of the army is well documented, not to mention at the praesidia.Footnote 106

A micro-historical perspective must be adopted, however, when examining the particular circumstances in which transactions were concluded using coins. Thus, a contextual approach to the coin finds is called for.Footnote 107 In the case of both Myos Hormos and Berenike, it is essential to consider the long-term excavation strategy (not to mention the approach to publicationFootnote 108 ), as well as site formation processes. Neither of the two ports has been completely excavated, and site formation processes are a common issue at many archaeological sites. A significant portion of the finds come from destruction or abandonment layers. In Berenike, for instance, fills containing redeposited material from the 1st and 2nd c. CE are a site-wide phenomenon, and a significant number of discoveries originate from layers associated with rebuilding and repair in post-Roman times (4th–5th c. CE),Footnote 109 which naturally excludes any precise determination of where or when they were originally deposited. The finds from Myos Hormos offer a more nuanced perspective because the abandonment of the port at the beginning of the 3rd c. CE resulted in numerous coins entering the archaeological record as primary deposits.

Several primary contexts containing coin finds were distinguished at both sites. The most general of these contexts are occupational layers, which usually yield coins either as single finds or in groups. These are either floor layers or occupational and debris strata resulting from activities in certain areas. The coins found their way into these deposits casually, presumably dropped or misplaced during routine handling, when being passed either from hand to hand or purse to purse. It is reasonable to assume that the higher the transaction volume in a particular location, the greater the likelihood of coins being dropped. On the other hand, individuals would probably have been careful not to lose valuable coins and have made an effort to retrieve any they accidentally misplaced.Footnote 110 Intentional discard may also have been possible in individual cases.Footnote 111

Trenches situated in areas of harbor-related activities have been excavated at both sites. The delivery of supplies, the loading and unloading of ships, and the carrying out of ship repairs, all common in waterfront districts, would have called for different behaviors than those expected in other contexts,Footnote 112 and the evidence is that these activities involved the handling of coins. In Berenike, worn Roman coins were found in sands and marine sediments dated to the late 1st c. BCE–1st c. CE, east of a harbor seawall in trench BE-2.Footnote 113 Another set of coins was associated with a possible wharf and quay area in the same trench, dated from the mid-1st through the second half of the 1st c. CE.Footnote 114 A coin from trench BE-54, located at the edge of the Ptolemaic and Early Roman harbor zone, lay on a 1st-c. CE surface that could have been part of a storage area for shipped goods and a loading or unloading platform.Footnote 115 Five coins came from loci associated with ship repairs in trench BE-5, dated to between the 1st and the 3rd c. CE.Footnote 116 In Myos Hormos, a Nero tetradrachm was discovered in trench 15 in the harbor area,Footnote 117 in a place that likely served for mooring boats and unloading goods and may have been associated with a seawall. Two Roman coins came from trench 7a, which included installations connected with a Roman waterfront and harbor jetty, constructed of amphoras and dated to the late Augustan period–early 1st c. CE (the precise location of the finds was not described in the report).Footnote 118 Boat and ship-repair infrastructure from the late 1st to the early 2nd c. CE in trench 12 also yielded a coin from one of the floorsFootnote 119 and another one from the floor of a large, unroofed area, associated with a number of hearths and dated to the early 2nd c. CE.Footnote 120 Excavations outside Building 3 in trench 10 (Sondage B), which was associated with boat repair and maintenance in the mid- to late 1st c. CE, also brought to light “a number of coins.” The structure was found to contain an industrial workshop with iron-smelting furnaces.Footnote 121

Another public location in Myos Hormos where coins were found in occupational loci was Central Building A (trenches F8d, F9c, F10a), situated in the sector of the town associated with the harbor. Donald Whitcomb interpreted this place as a collection, storage, and redistribution center for trade goods and subsistence supplies: either a granary or storage depot.Footnote 122 The part of the structure that was excavated comprised a series of rooms with doorways facing onto a central courtyard. Two coins were deposited on tamped mud floors, in one case near a possible hearth.Footnote 123 The open courtyard may have functioned as a market and a place for loading and unloading goods, and their display or sale, as well as storage, processing, and repacking for land shipment. Light industries such as ironworking, glassmaking, weaving, and other cloth manufacturing, as well as ship repairs and preparation of naval stores, could have been situated in the building. Further excavations by Peacock and Blue neither confirmed nor refuted this interpretation.Footnote 124

Inferences about the role of coins in the religious practices of residents and visitors can only be made for Berenike as no clearly religious structures have been uncovered in Myos Hormos thus far. A coin was discovered embedded in an earthen floor from the 3rd–4th c. CE in the Palmyrene shrine (trench BE-6).Footnote 125 It was probably unintentionally dropped. Coins have also been found in the largest and most significant temple in town, the Isis temple, and while the details of their discovery have not yet been made public (the dataset is still to be published), it can be presumed that the pattern of finds would have been influenced by two factors. First, regularly swept paved surfaces, like that of the temple courtyard, tend to yield fewer coins because, if lost, they were promptly recovered or removed.Footnote 126 If swept away, they could have inadvertently landed in the trash, meaning they would not be found inside the building. It is much more common to find coins on earthen or mud floors, which are more conducive to having coins trampled into them. Second, coin deposition in a religious structure would likely have been different from deposits at other locations.Footnote 127 The example of two Indian coins of the Satavahana dynasty, already reported from the excavations in the temple, found alongside a Buddha statue of Proconessian marble and other Indian dedications,Footnote 128 tentatively suggests votive offerings made by foreign merchants or visitors. In Roman ports, foreign copper or lead coins had no economic value and were considered useless pieces of small change. For their owners, however, they might have served as symbols of their place of origin and their distinctive religious beliefs.

A contextual analysis of coin finds from residential structures is possible only for Myos Hormos, because Roman-period houses have yet to be excavated in Berenike. A building complex comprising an open area and lightweight structures was partly excavated in trench C4c in the northwestern part of the site. It was built and inhabited during the earliest stages of port activity, likely in the early 1st c. CE, and was subsequently abandoned and repurposed as a trash dump.Footnote 129 One coin was found embedded in the floor of a room, while another was unearthed within the occupational layer of the open courtyard. A third coin was discovered within a stratum representing various occupation phases and debris accumulation, including a fire pit, and covering a narrow alleyway to the north of the room.Footnote 130 A total of 59 specimens originated from a substantial residential structure, dubbed the “Roman Villa” (trenches E6 and a small part of D6).Footnote 131 This dataset includes three items that may not be coins, along with an ancient lead token.Footnote 132 One coin was found in the northeastern room, possibly within an occupational context, although this area was not excavated down to bedrock. Six more came from a presumed hearth, where there was a deposit of ash and bones in burnt soil, discovered east of the villa’s wall D.Footnote 133 The three intact storerooms in this structure, with their stashes of numerous pottery vessels and other artifacts in situ, provided insight into contemporaneous artifact use and storage practices. The large storeroom yielded three coins from among the small vessels lying on the floor, another 16 were unearthed along with associated finds from the floor level inside the small storeroom, and, last but not least, a single coin was found inside the storeroom cellar.Footnote 134 According to the excavator, the large storeroom was probably also used for grain grinding, while later stages of food preparation were carried out elsewhere, probably in the courtyard to the west, and the small storeroom could have been used for household items. Carol Meyer considered the coins an indication of formal commercial activity, noting that significantly more coins were recovered from the small storeroom than from the large one. The cellar of the large storeroom is presumed to have been emptied by the villa owner, who, Meyer proposes, might have retreated to the Nile Valley between trading seasons, taking with him his most valuable possessions, which naturally included coins.Footnote 135 It should be noted at this point that distinguishing between domestic and business contexts in many port settings, including Myos Hormos, poses difficulties. Business transactions and other activities were frequently conducted from the home.Footnote 136 Excavations of post-Roman Berenike (4th–5th c. CE contexts) have demonstrated substantial overlap between domestic/residential and industrial/commercial activities, several of the multi-storied structures evidently having accommodated both types of pursuits.Footnote 137

The other example of a residential structure from Myos Hormos that yielded coins from occupational layers is a building situated in the non-elite area known as the “Roman town,” identified in trench 8a and dated to at least the late 1st to mid-2nd c. CE or earlier.Footnote 138 The courtyard had a surface of coral and pebble conglomerate and was part of a large structure with two storage rooms. Four pots were sunken into the gravel of the courtyard and one of the stores, probably to keep foodstuffs.Footnote 139 Here, as in the case of the previously discussed structure, the pattern indicates that coins were being used in a way that was conducive to losing a stray coin or two on the floors.

Coins from presumed industrial zones at Myos Hormos are taken to illustrate the association between coinage and specialized activities. A building known as Villa East in the northwestern part of the city, between the central building and the peripheries of the town (trenches E7a and E6b),Footnote 140 yielded a coin from the mud floor of a long room that also contained a small furnace (likely an ironworking installation) with a significant amount of slag adhering to its walls. Another three coins came from the ashy fill that had accumulated during the use of the furnace and its subsequent abandonment.Footnote 141 Coins were also found on the floor and on a secondary surface above it inside an open room or stall in trench E7a that potentially served as a storage unit or part of an industrial area.Footnote 142

Finally, one should mention a small coin hoard from Berenike discovered in 2019. It has not been included in the dataset examined for this study, but it stands as the sole coin hoard found in the Eastern Desert to date. This accidental discovery was made outside the city limits, west of the site. It comprised 14 Alexandrian bronze coins that were deposited in a small jar and had seemingly been burned. The list of coins has not been published yet, but at least one of them is an Alexandrian issue of Tiberius.Footnote 143 This discovery confirms the function of coins as a store of wealth in the Eastern Desert, and the hoard was possibly hidden by a traveler or merchant whose misfortune was that he did not come back to retrieve it.

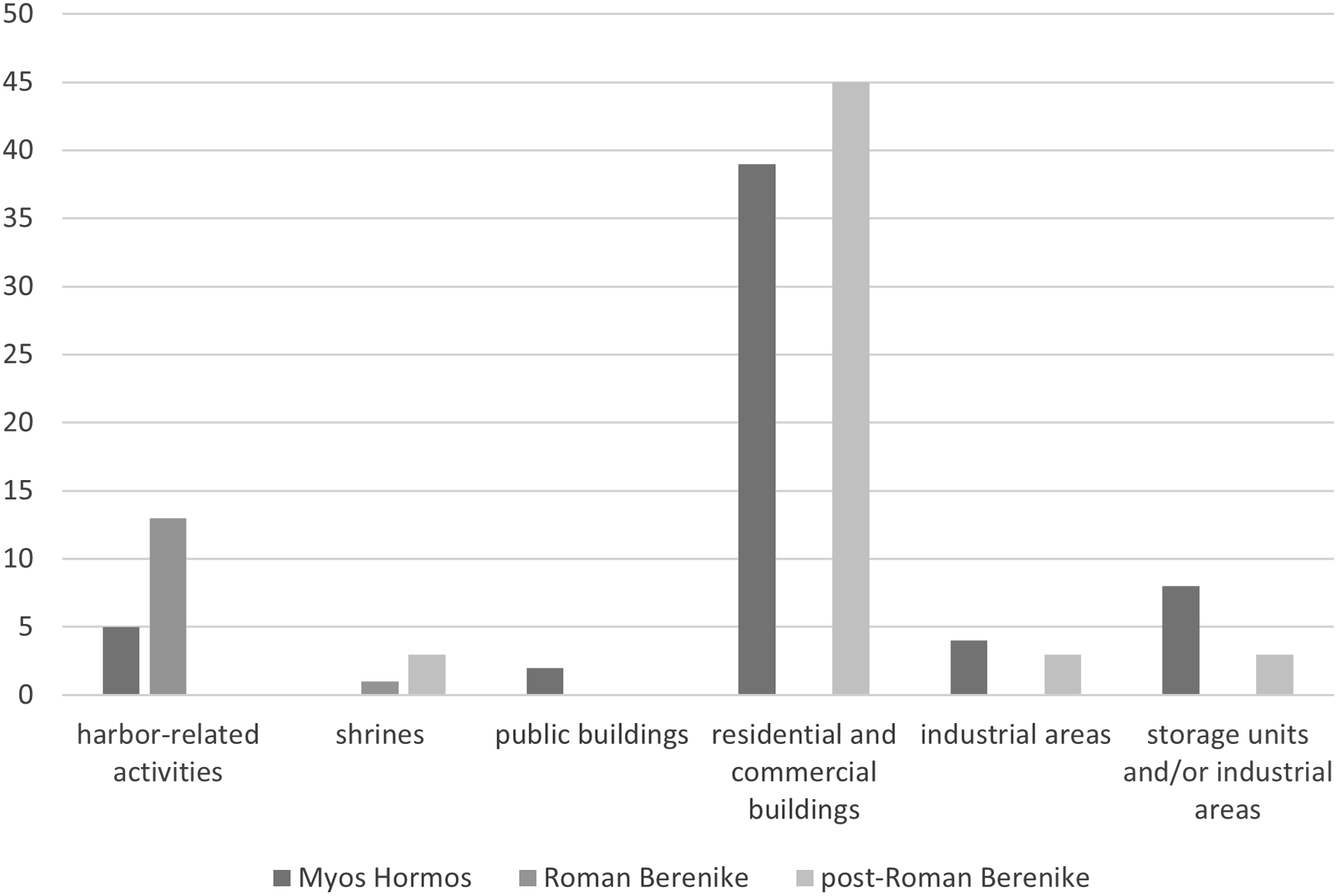

A comparative analysis of coin use in the Red Sea ports during the Roman, pre-Roman, and post-Roman periods could yield valuable insights into the evolving function and value of coinage in Berenike across different historical contexts. However, such a comparison is currently feasible only for the post-Roman period (Fig. 10). The coinage from Ptolemaic Berenike remains largely understudied; to date, only 16 Ptolemaic coins from the site have been published.Footnote 144 Of these, 10 were surface finds, while the others were recovered from contexts such as trash dumps, leveling fills, or abandonment layers – all contexts with limited interpretive value.Footnote 145

Fig. 10. Distribution of coin finds by context type. (Chart by the author.)

At Myos Hormos, the evidence for the Ptolemaic period is even more fragmentary. Only four Ptolemaic coins have been identified, all retrieved from a trench containing installations associated with a Roman-era waterfront and harbor jetty.Footnote 146 According to Peacock,Footnote 147 this may indicate that earlier Ptolemaic occupation layers lie deeper, possibly beneath the current water table. However, no securely dated Ptolemaic deposits have been identified at Myos Hormos to date.

In contrast to the limited numismatic evidence from the Ptolemaic period, Late Roman coins constitute a substantial component of the material culture at Berenike during the post-Roman period. They account for 19.6% (115 coins) of all published finds to date, though the actual number is likely higher given the poor preservation of many specimens. All identified coins are bronze issues dated to the 4th and 5th c. CE.

The highest concentration of these coins comes from the central urban quarter, where a group of multifunctional, multi-story buildings was excavated. The upper floors appear to have served as domestic spaces, while the ground floors were used for commercial and public purposes.Footnote 148 Coins were recovered from both primary use contexts and secondary depositional layers. Several were found in strata associated with building abandonment and collapse, alongside a broad range of artifacts, including bronze and lead weights, fragments of scales, peppercorns, a small hinge (possibly from a container), iron rings, locking mechanisms, and personal adornments such as beads and gem-quality stones. Other items included worked bone and stone, finely crafted metal objects (e.g., an iron ring, situla handle, bell, and miniature balance), and the bases of glass vessels likely used for perfumes or other aromatic substances.

Notably, several coins were recovered from collapse layers adjacent to architectural niches fitted with wooden shelving, likely used to store valuable items. One coin was found directly on the preserved floor surface at the base of such a niche. Additional coins came from mixed deposits of architectural and occupational debris from the upper-story domestic areas.

These buildings featured narrow, single entrances, and the presence of numerous copper-alloy locking mechanisms suggests a strong concern for security. The associated assemblages – comprising luxury goods, storage containers, and instruments related to trade – indicate that these structures functioned as hubs of economic activity. In one ground-floor room, two woven grass mats were found in situ, likely serving as comfortable surfaces for work-related tasks.Footnote 149

Late Roman coins were also found in post-Roman contexts within public buildings. In one structure near the ancient harbor – possibly a storage facility or warehouse – coins were discovered alongside 10 complete or nearly complete amphorae, roughly 50 beryl fragments, and several hundred charred peppercorns.Footnote 150 In Trench 26, a post-Roman structure of unknown function yielded Late Roman coins in association with glass, stone beads, gemstones, and a handle from an Aksumite-style vessel.Footnote 151 Further evidence linking coins to industrial activities during this period comes from small-scale manufacturing areas, including zones of metal smelting and glass working, located just north of the Isis Temple above the floor of a Roman-era courtyard.Footnote 152

The uneven distribution of coin finds between commercial and residential areas across the Roman and post-Roman periods at Berenike likely reflects differences in excavation strategy and site preservation. As previously noted, all documented residential structures to date belong to the post-Roman period; no Roman-period domestic dwellings have been excavated.Footnote 153 Nonetheless, as at Myos Hormos, it is reasonable to expect that Roman-era buildings combining residential and commercial functions, once identified and excavated, would likewise yield significant numismatic evidence.

Coin finds from post-Roman buildings of this type confirm the continued use of Roman currency in everyday transactions at the port, highlighting the enduring economic role of Roman coinage in post-Roman Berenike. By this time, Berenike lay beyond the borders of the Roman Empire and was administered by the Blemmyes; nevertheless, the value and acceptability of Late Roman coins were likely sustained by longstanding tradition and social consensus.

In addition to domestic, commercial, and industrial contexts, Late Roman coins at Berenike have also been found within religious structures. Two specimens were recovered from occupational layers in the rebuilt Palmyrene temple, which remained in use during the post-Roman period.Footnote 154 However, these coins were retrieved from layers above the floor surfaces and are best interpreted as casual losses rather than deliberate deposits. A similar case is documented in the Christian Basilica, where a coin was discovered on the floor of a room that, during the later phases of occupation, appears to have functioned – at least in part – as a storeroom for building materials.Footnote 155

Beyond incidental losses, two finds may reflect non-economic uses of coinage in religious or symbolic contexts. The first example comes from the Northern Complex, where a coin was found in one of the temple pools on the latest floor level, likely having served as a votive offering.Footnote 156 The second example was uncovered during the excavation of the Harbor Temple. This coin, featuring two drilled holes, appears to have been repurposed either as a pendant or as a decorative fixture. Nearby, a bronze bull’s head mounted on a bronze plate was also recovered. It is notable that both the coin and the bronze object feature bull imagery, suggesting a possible symbolic or cultic connection between them.Footnote 157

These examples suggest that in the post-Roman period, coins at Berenike may have served ornamental, ritual, or amuletic functions – uses not attested in earlier phases of the site’s occupation. They broaden the interpretive scope of numismatic evidence, highlighting the symbolic and cultural dimensions of coinage beyond its conventional economic role.

Concluding remarks

The examination of coin use and everyday transactions in Berenike and Myos Hormos in Roman times, based upon coin finds and the broader archaeological and epigraphic evidence, yields a picture of a vibrant Red Sea port economy, with the interconnected spheres of private and personal coin use by residents and visitors set against their living and working environment. The abundance of coin finds from both sites emphasizes the integral role of coinage in economic and social transactions, emphasizing the importance of this aspect of people’s lives.

The study casts light on the variety of goods that could be purchased in the ports, including food, fuel, imported commodities such as black pepper or other exotic items, gemstones, and beads. Port residents, traders, sailors, and visitors used the services of ship caulkers, barbers, sculptors, prostitutes, and others. Coin finds from ship-repair facilities and other industrial areas indicate that skilled craftsmen and other individuals working in the ports accepted cash payments in exchange for their services. Additionally, these finds suggest that economic transactions involving certain goods occurred at the places of production. Discoveries from both private and public buildings provide evidence of various transactions or payments that likely occurred there, possibly including quintana payments. The existing infrastructure supported a monetized economy, as indicated by archaeological finds and written sources documenting the presence of shops, a bakery, and a sculptor’s atelier. Various other transactions took place in the ports, as well, such as the sale of donkeys or the arrangement of loans. Money was also spent on religious offerings and festivities. The pool of coins circulating in Roman ports differed in terms of its chronological and denominational structure from Alexandria’s but was similar to finds from the praesidia, indicating a localized pattern of circulation.

Nevertheless, each coin find from Berenike and Myos Hormos carries with it a distinct history, imbued with significance both for individuals and for society as a whole. In the case of Berenike and Myos Hormos, one can imagine Herennios preparing for a seasonal festival in Berenike by purchasing roses. While gathering the required number of coins from where he kept them, he may have accidently dropped one of them. A foreign merchant or sailor may have visited the barber to groom an overgrown beard after a long sea journey. The crew of a recently arrived ship may have lost some bronze coins while paying for ship maintenance and repair in the harbor workshop. And, indeed, they might have sold some pepper at the harbor to acquire local coinage to spend in the ports. A sculpture of Buddha was ordered from a local atelier for dedication in Berenike’s main temple. The Indian merchant who was perhaps behind this commission may have offered an Indian coin he brought with him at the temple, hoping by this act of devotion to bring good luck to his business ventures. Although these are speculative scenarios, they are all highly plausible and help illustrate the everyday transactions that took place in Roman Red Sea ports, as well as the role of coinage in the social and private lives of the inhabitants and visitors.Footnote 158 By doing so, they contribute to a better understanding of the everyday lives of the ancient transcontinental port communities. Furthermore, monetization during the Roman period continued to shape the port’s development in the centuries that followed. Under Blemmyan administration, the use of coinage persisted, with its functions extending beyond strictly economic purposes, reflecting both continuity and adaptation in local practices.

Finally, this study highlights an important methodological consideration: interpretive models formulated predominantly for Western or military sites are not always directly applicable to the contexts of the Eastern Desert or Egypt more broadly. The relatively limited scale of material remains, alongside the complexities involved in integrating numismatic, epigraphic, and archaeological data, necessitates a flexible and context-sensitive analytical approach. In acknowledging these constraints, this research contributes to a more nuanced and grounded understanding of monetization and daily life in the interconnected yet distinct world of the Roman periphery.