Introduction

The international system often reinforces nationalist dominance in conflicts; however, religion continues to play a significant role, especially where it intertwines with national identity (Frisch & Snadler, Reference Frisch and Sandler2004). Religion shapes individuals’ worldviews and normative beliefs (Tessler & Nachtwey, Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998; Goldstein & Keohane, Reference Goldstein and Keohane1993), particularly among the devout. As Leege (Reference Leege, Leege and Kellstedt2016, cited in Tessler & Nachtwey, Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998, p. 620) notes, religion frames social and political questions as “sacred, eternal, and implicated with the ultimate meaning of life.”

Religious attitudes are based on what is called religious ethics. “Scholars of religious ethics critically investigate religion’s efforts to shape the character and guide the behavior of individuals, groups, and institutions, and they often draw on religious sources to address contemporary or perennial moral problems” (Miller, Reference Miller2016, p. 17). This study focuses on two religious attitudes grounded in religious ethics: political–religious attitudes and personal religious attitudes. Religious ethics influence tolerance levels differently across societies and religious traditions (Leak & Randall, Reference Leak and Randall1995). In some contexts, religion promotes peace (Abu-Nimer, Reference Abu-Nimer2001), whereas it may fuel conflict or justify violence in other contexts (Tabory, Reference Tabory1981; Beit-Hallahmi, Reference Beit-Hallahmi and Krieger2001; Canetti-Nisim, Reference Canetti-Nisim2003).

However, not all religious influence is negative. Some studies find that only theocratic tendencies correlate negatively with tolerance (Karpov, Reference Karpov2002). In the Middle East—both in Muslim-majority countries and in Israel—religion and religious movements are vital to understanding political and social phenomena (Tessler & Nachtwey, Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998).

Furthermore, religious identification is associated with religious conflict perception. Conflict perception refers to “an individual’s subjective view regarding the essence of the conflict and its core issues” (Khatib, Canetti & Rubin, Reference Khatib, Canetti and Rubin2018, p. 382). Once internalized, religious identity is hard to abandon, reinforcing the persistence of religious conflicts (Seul, Reference Seul1999).

Religion as a political identity can shape intergroup attitudes and conflict dynamics (Rouhana & Bar-Tal, Reference Rouhana and Bar-Tal1998; Flunger & Ziebertz, Reference Flunger and Ziebertz2010). Face-to-face and online surveys of 2,171 citizens across Palestine, Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia were conducted to examine the impact of political–religious and personal religious attitudes on reconciliation in interstate conflicts (e.g., the Arab–Israeli conflict) and tolerance in intrastate conflicts (e.g., secular–religious divisions within Muslim and Jewish communities).

Personal religious attitudes refer to practices like prayer and worship, while political–religious attitudes involve support for religion’s role in public life and religious political movements (Tessler & Nachtwey, Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998). Two key arguments are advanced: (1) religious attitudes influence reconciliation through their relationship with religious conflict perception, and (2) both personal and political–religious attitudes shape tolerance in intragroup (internal) conflict contexts.

Literature review

Religion in the public sphere and conflict context

Religion influences conflict both through its teachings, which shape values promoting either peace or violence, and through individuals’ behavior in conflict settings (Rehman, Reference Rehman2011; Juergensmeyer, Reference Juergensmeyer1993). Recent research continues to refine our understanding of religion’s political role in conflict resolution. Isaacs (Reference Isaacs2016) highlights the strategic use of religious narratives in mobilizing support for or against violence, while Garred and Abu-Nimer (Reference Garred and Abu-Nimer2018) emphasize interfaith dialogue as a critical tool for peacebuilding. More recent studies (e.g., Grewal & Cebul, Reference Grewal and Cebul2023) explore how religious reinterpretation can help bridge ideological divides, offering a more dynamic view of religion’s ambivalence in conflict settings. These empirical findings are interpreted through three major theoretical perspectives on religion in conflict: primordialism, instrumentalism, and constructivism (Hasenclever & Rittberger, Reference Hasenclever and Rittberger2000).

Primordialism sees religion as a core identity that drives intergroup conflict, as religious actors resist compromising on sacred beliefs (Seul, Reference Seul1999). Some scholars challenge this view, arguing that religion can also foster reconciliation (Abu-Nimer, Reference Abu-Nimer2001), whereas others uphold its relevance, especially in identity-based clashes (Huntington, Reference Huntington1996). Instrumentalism holds that religion is not the root cause of conflict but is used to mobilize support for struggles driven by economic or political inequality (Hasenclever & Rittberger, Reference Hasenclever and Rittberger2000). Constructivism views religion as a variable shaped by interpretation and context, capable of both justifying and rejecting violence depending on how religious texts and doctrines are framed (Hasenclever & Rittberger, Reference Hasenclever and Rittberger2000). Religious attitudes are thus mediated by interpretation, values, and context (Bruce, Reference Bruce1995). This paper argues that political–religious attitudes tend to reinforce values that oppose reconciliation in protracted conflicts, while personal religious attitudes are more likely to support tolerance in internal conflicts.

Religion and conflict attitudes

The relationship between religion and attitudes toward violence or reconciliation is complex. Some studies find no direct link between religion and violence (Appleby, Reference Appleby2000), whereas others show both negative (Philpott, Reference Philpott2007) and positive correlations with political violence (Hasenclever & Rittberger, Reference Hasenclever and Rittberger2000; Canetti et al., Reference Canetti, Hobfoll, Pedahzur and Zaidise2010). Canetti et al. (Reference Canetti, Hobfoll, Pedahzur and Zaidise2010) argue that existing explanations are incomplete, and other research points to indirect links through psychological factors and feelings of deprivation (Zaidise, Canetti-Nisim & Pedahzur, Reference Zaidise, Canetti-Nisim and Pedahzur2007).

Overall, the literature has yet to clearly define religion’s role in reconciliation or explore how different religious attitudes shape that role. Many scholars agree that religion can mobilize individuals toward either peace or violence (Schliesser, Reference Schliesser2020; Chakhesang, Reference Chakhesang2024; Kadayifci-Orellana, Reference Kadayifci-Orellana2009). This research suggests that this role depends on the conflict’s case, values, and nature and is not deterministic. Classifying religion as part of identity in a conflict context leads us to think about the role of religious conflict perception in conflict resolution.

When religion becomes part of identity, it shapes conflict perception, which influences attitudes toward reconciliation. Identity-based conflicts, especially those rooted in religious or national narratives, are harder to resolve than material ones, particularly when symbolic or ideological elements are involved (Auerbach, Reference Auerbach and Bar-Siman Tov2010; Tabory, Reference Tabory1981). Empirical studies have shown that when people perceive a conflict as religious, they are less willing to reconcile (Khatib, Reference Khatib2018; Khatib, Canetti & Rubin, Reference Khatib, Canetti and Rubin2018; Canetti et al., Reference Canetti, Khatib, Rubin and Wayne2019). This suggests that religious conflict perception acts as a mediator between religious identity and attitudes toward reconciliation. However, the literature lacks clarity on which specific religious attitudes lead to these perceptions. The research addresses that gap by empirically testing the role of political and personal religious attitudes in shaping reconciliation, mediated by religious conflict perception (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research model: intergroup and intragroup conflict.

The impact of religion on political attitudes and conflict resolution

Religion significantly shapes political attitudes in conflict settings (Spierings, Reference Spierings2019); however, the literature often treats it as a monolithic force, failing to distinguish between its various components. Religion consists of belief, practice, and behavior (Djupe & Calfano, Reference Djupe and Calfano2013), or as others describe it, faith and ritual (Kadayifci-Orellana, Reference Kadayifci-Orellana2009). Research on religion and conflict varies in its focus—from leaders and institutions to beliefs and behaviors; thus, the findings are often inconsistent. Appleby (Reference Appleby2000), for instance, found that religious actors can promote both violence and moderation, while Rasul (Reference Rasul2009) highlights how religious leaders and organizations can serve reconciliation efforts.

Religion has a profound impact on political attitudes in a conflict context (Spierings, Reference Spierings2019), but the literature lacks an in-depth examination of the various aspects of religion that shape attitudes toward reconciliation. This paper focused specifically on the aspects of belief and behavior by exploring the relationship between political and personal religious attitudes, which are part of one’s belief system and faith, and personal religious practices and attitudes, which are part of one’s behavior.

Beyond shaping political preferences, religion also plays a deeper role in conflict resolution. As a core element of identity, religion informs how individuals perceive conflicts and their potential resolution (Rasul, Reference Rasul2009). It provides a moral lens through which people evaluate justice, violence, and reconciliation (Juergensmeyer, Reference Juergensmeyer1993). However, this influence is not uniform. Some studies argue that religious beliefs may lead to rejection of reconciliation (Rothman, Reference Rothman1997), while others find that religious rituals can promote peace or intensify division depending on interpretation and exposure to religious messaging (Abu-Nimer, Reference Abu-Nimer2003; Eisenstein, Reference Eisenstein2006). The extent to which personal religious practices affect public attitudes remains ambiguous. Such practices can expose individuals to religious speech and authority figures who may frame conflict in specific ways, thereby influencing their political positions. This religious commitment may, in some contexts, lead to non-peaceful intergroup relations (Eisenstein, Reference Eisenstein2006).

Understanding how these religious attitudes shape reconciliation requires attention to conflict framing. Reconciliation is not merely a political agreement but a psychological process involving deep shifts in beliefs, emotions, and motivations (Bar- Tal & Bennink, Reference Bar-Tal, Bennink and Bar-Siman-Tov2004). These shifts depend on how individuals perceive the nature of the conflict. Studies show that religious conflict perception, which is the framing of a conflict in religious terms, significantly reduces willingness to reconcile (Khatib, Canetti & Rubin, Reference Khatib, Canetti and Rubin2018; Canetti et al., Reference Canetti, Khatib, Rubin and Wayne2019). As Bar-Tal (Reference Bar-Tal2009, Reference Bar-Tal2013) emphasizes, reconciliation is only possible when certain preconditions, such as restructured attitudes and belief systems, are met.

The present research addresses a critical gap by examining how political and personal religious attitudes influence reconciliation in both interstate and intrastate conflicts. Addressing this gap requires analyzing how these attitudes relate to religious conflict perception, offering a clearer picture of the mechanisms through which religion shapes intergroup relations and the prospects for peace.

Religion and tolerance in intergroup relations

The influence of religion on intergroup relations is not limited to reconciliation in interstate conflicts; it also plays a vital role in shaping political tolerance within societies experiencing intrastate tension, particularly between secular and religious communities. This paper investigates how personal and political–religious attitudes impact individuals’ tolerance of religious and secular outgroups in the Arab world. Political tolerance generally refers to the willingness to extend civil liberties, such as freedom of expression and education, to individuals or groups with opposing or controversial beliefs (Karpov, Reference Karpov1999). It reflects not agreement, but acceptance of difference (Sullivan, Piereson & Marcus, Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1979; Harell, Reference Harell2010). In polarized societies, such tolerance is key to peaceful coexistence.

The literature provides contrasting views on religion’s effect on tolerance. Religion may encourage tolerance by fostering social bonds and shared moral values across groups (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Djupe & Calfano, Reference Djupe and Calfano2013). Moreover, it can promote exclusion or moral condemnation of those whose views or lifestyles deviate from orthodox norms (Little & Appleby, Reference Little, Appleby, Coward and Smith2004). Although earlier assumptions suggested that conservatives and religious individuals are less tolerant, recent scholars, such as Reimer (Reference Reimer2021), have found no direct correlation, particularly among committed conservatives, suggesting that the relationship is more nuanced.

Studies from Egypt and other Arab countries also show inconsistent findings on the link between religiosity and tolerance (Hassan & Shalaby, Reference Hassan and Shalaby2019). These discrepancies highlight the need to differentiate between types of religiosities. The research distinguishes between political–religious attitudes (support for religion’s role in public and political life) and personal religious attitudes (practices of devotion such as prayer and piety), and it examines how each relates to tolerance.

Research has consistently found that doctrinal orthodoxy, beliefs that emphasize exclusivity and moral absolutism, tends to correlate with political intolerance, particularly toward groups that challenge religious norms (Peffley, Hutchison & Shamir, Reference Peffley, Hutchison and Shamir2022; Wilcox, Jelen & Leege, Reference Wilcox, Jelen, Leege, Leege and Kellstedt1993; Reimer & Park, Reference Reimer and Park2001). However, others have contested this conclusion, arguing that religious individuals may also adopt inclusive interpretations (Eisenstein, Reference Eisenstein2006). This tension is reflected in religious texts themselves, which often present both inclusive messages of love and tolerance and commands for hostility against some outsiders (Popovski, Reichberg & Turner, Reference Popovski, Reichberg and Turner2009). The interpretive flexibility of religious doctrine means that individual experience, context, and leadership play a key role in whether religion fosters tolerance or exclusion.

The impact of religious practices on political tolerance is equally contested. Some studies suggest that regular religious participation can reinforce group boundaries and promote intolerance (Reimer & Park, Reference Reimer and Park2001); however, others show that it can encourage openness and empathy (Neiheisel, Djupe & Sokhey, Reference Neiheisel, Djupe and Sokhey2009). Earlier findings also suggest mixed effects: religious commitment has been found to correlate positively (Stouffer, 1955; Filsinger, Reference Filsinger1976) with political tolerance as well as weakly negatively (Karpov, Reference Karpov1999) or not at all (Ellison & Musick, Reference Ellison and Musick1993).

This research is based in Western democratic contexts and often centers on religious affiliation rather than values or practices (Stouffer, 1955; Beatty & Walter, Reference Beatty and Walter1984; Wilcox & Jelen, Reference Wilcox and Jelen1990; Jelen & Wilcox, Reference Jelen and Wilcox1990). Peffley, Hutchison, and Shamir (Reference Peffley, Hutchison and Shamir2022) point out that studies frequently neglect other factors such as ideological worldviews, perceptions of threat, or exposure to pluralism. Djupe and Calfano (Reference Djupe and Calfano2013) similarly emphasize the need to study religious values, not just membership or attendance.

The research aims to fill the gap by examining how religious attitudes operate in the Arab world and the Middle East, where the political context differs markedly from the liberal democratic settings that dominate prior scholarship. Following the Arab Spring, many countries in the region have experienced heightened ideological polarization, especially between secularists and the religious (Hassan & Shalaby, Reference Hassan and Shalaby2019). In this context, tolerance is not only a moral ideal but a necessary condition for political stability and social cohesion (Eisenstein & Clark, Reference Eisenstein and Clark2014).

In such polarized, often non-democratic environments, the relationship between religious attitudes and political tolerance may take different forms. Exploring this relationship is essential for understanding how religion interacts with civil values under conditions of conflict, competition, and institutional weakness (Grewal & Cebul, Reference Grewal and Cebul2023; Toft, Reference Toft2006; Svensson, Reference Svensson2007).

How the Arab–Israeli conflict is perceived

The Arab–Israeli conflict is complex, involving political, national, religious, and material dimensions (Kelman, Reference Kelman1986). Some scholars highlight its colonial character and Israel’s status as a settler-colonial state occupying Arab lands (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2012; Mamdani, Reference Mamdani2015; Robinson, Reference Robinson2013; Rouhana, Reference Rouhana2015), While others emphasize competing nationalist movements, such as Palestinian nationalism and Zionism, that struggle over self-determination in the same territory, the conflict began with Zionist immigrants to Palestine during the British Mandate period.

The conflict is also rooted in national identity; Arabs, including Palestinians, view Palestine as ancestral land and Israel as a threat to Arab unity through its aggressive actions, prompting wars and long-standing embargoes (Kelman, Reference Kelman1999; Steiner, Reference Steiner1976). The religious dimension is also central: some argue that the conflict is between Zionist Jews and Muslims, grounded in competing religious claims based on the occupation of a holy land (Al Qaradawi, Reference Al Qaradawi2001; Hertzberg, Reference Hertzberg2000).

From the Israeli perspective, the state was founded as a national homeland for Jews, but there is a growing demand to define the state in religious terms (Stepan, Reference Stepan2000). This trend was institutionalized through the 2018 Nation State Law, which declared Israel as “the nation-state of the Jewish people.” The law heightened debates over equality and identity by prioritizing Jewish self-determination over civic inclusivity, illustrating the formal entrenchment of religion in defining the state’s character (Buettner, Reference Buettner2020; Agbaria, Reference Agbaria2021).

International actors, particularly the USA, have reinforced this framing by supporting Israel on religious and ideological grounds (Oldmixon, Rosenson & Wald, Reference Oldmixon, Rosenson and Wald2005). Despite decades of diplomacy, the conflict persists today, as Israel continues to occupy Palestinian and broader Arab lands. Palestinians endure ongoing hardship under occupation (Ayesh & Ben Hagai, Reference Ayesh and Ben Hagai2025), which remains a central factor sustaining the conflict and shaping how it is perceived (Mansab, Reference Mansab2024).

The religious–secular tension in the Middle East

Tensions between religious and secular ideologies, with roots dating back to the building of the national states in the Middle East, have risen over the years. For years, a state of polarization and hostility between religious and secular thoughts has characterized the Middle East, including Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, and Israel, among other countries (Haynes & Wilson, Reference Haynes and Wilson2019; Porat, Reference Porat2023; Hassan & Shalaby, Reference Hassan and Shalaby2019).

The case of the Arab Spring and the people’s uprising against their regimes restored Islamic orientation to the political front, and secular groups that are not necessarily linked to authoritarian regimes, as happened in Tunisia and Egypt, rose. The state of tension remained, albeit with a reduction in its intensity at times, and some collaborations between secular and religious groups occurred (Angrist, Reference Angrist2013); however, tensions and rivalries between the two approaches still exist.

The most dominant aspect of this relationship is based on the role of religion in the public sphere and the governing aspects of religious and secular rules (Hallward, Reference Hallward2008). Although some religious implications in the personal status law (like marriage and burial) are found in Middle Eastern countries, the role of religious law (“Sharia” or “Halakah”) remains in dispute. In Israel, tension between secular groups and religious (mainly orthodox Jews) groups is prominent over several issues such as working on Saturdays and the separation of women and men (Hallward, Reference Hallward2008).

Hence, contestation between religious attitudes and secularity is high in the Middle East; however, there are several dimensions of secularity, and people may perceive religious attitudes differently (Krämer, Reference Krämer2013).

Research focus and hypotheses

This article explores how religious attitudes, both political and personal, affect intergroup relations in the Middle East, focusing on their impact on reconciliation in interstate conflict (specifically the Arab–Israeli conflict) and tolerance in intrastate religious–secular tensions. Building on theoretical perspectives and empirical gaps identified in the literature, the study distinguishes between political–religious attitudes (support for religion in public life) and personal religious attitudes (individual practices and piety). It further examines how conflict perception, the tendency to frame conflict in religious terms, shapes the relationship between religious attitudes and willingness to reconcile. Using survey data from multiple Middle Eastern contexts, the study tests the following hypotheses:

H1: Political–religious attitudes will negatively predict willingness to reconcile.

H2: Personal religious attitudes will not significantly predict willingness to reconcile.

H3: Conflict perception will mediate the relationship between religious attitudes and reconciliation.

H4: Political and personal religious attitudes will not significantly predict intolerance in internal secular–religious cleavages.

Methodology

The present analysis employs quantitative research methods in the form of surveys, both face-to-face and online, of students in various countries. It is a comparative study using data from four Arab states, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, and Tunisia, as well as from Israel. These countries were chosen because they were involved in the conflict; Tunisia was chosen because it represents a democratic state with Islamists in power (during the research period) and a state of polarization between Islamists and secularists, in addition to making sure that its geographical distance had no effect. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with students in Israel, Palestine, and Jordan. The survey, conducted in Hebrew and Arabic, took approximately 25 minutes to complete and was administered from November 15, 2015, to March 10, 2016. Footnote 1 After encountering several obstacles to conducting the survey in person in Egypt and Tunisia, I decided to conduct online surveys via the Unipark survey system. The online survey was administered from April 22, 2016, to June 21, 2016. Footnote 2

The sample comprises 2171 subjects comprising 563 students from Jordan, 377 Palestinians from the West Bank, 226 students from Tunisia, 70 students from Egypt Footnote 3 , and 935 students from Israel, of whom 309 were Palestinian citizens of Israel (including Muslims, Christians, and Druze) and 626 were Jewish citizens. Overall, the sample was approximately 64% Muslim, 31% Jewish, 3.4% Christian, and 1.4% Druze. Women made up 62% of the sample, and the average age was 23 years.

To ensure a diverse and representative sample of university students, universities in each country were purposively selected to reflect variation in academic institutions and their surrounding social contexts. In Israel, Palestine, and Jordan, where data collection was conducted face-to-face, respondents were selected randomly in public spaces and common areas within university campuses. Trained data collectors, fluent in both Arabic and Hebrew, administered the surveys to ensure clear communication across linguistic and cultural groups. In Tunisia and Egypt, the survey was conducted online and distributed via social media platforms restricted to university-affiliated groups, alongside direct dissemination among students from varied socioeconomic and academic backgrounds. Across all settings, participation was voluntary and anonymous, enhancing both the ethical integrity of the research and the reliability of the responses.

The composition of the sample aligns broadly with the demographic, religious, and political diversity found within university student populations in each country. In terms of political orientation, Israeli Jewish students in particular exhibited wide ideological variation: 21% identified with the right, 30% placed themselves at the center, and 33% aligned with the left, with an additional 5% identifying as extreme left. This distribution captures the known fragmentation within Israeli Jewish political attitudes, particularly in university settings, and provides a critical lens through which to interpret attitudes toward reconciliation. Similarly, the Palestinian and Jordanian samples showed significant representation across the political spectrum, though with comparatively stronger centrist and right-leaning affiliations. In Tunisia, 35% of respondents positioned themselves at the political center, reflecting the country’s complex post-revolution political landscape. Beyond political ideology, the samples displayed variation in gender, religiosity, and income levels. For example, women were overrepresented in Tunisia (69%) and Jordan (58%), consistent with national higher education trends. Religious identification mirrored national majorities—Israeli participants were predominantly Jewish (67%), whereas Tunisian, Jordanian, and Palestinian respondents were overwhelmingly Muslim. These patterns collectively suggest that while the sample is not statistically representative of entire national populations, it captures substantial intra-country diversity, allowing for meaningful cross-national comparisons and interpretations of the findings.

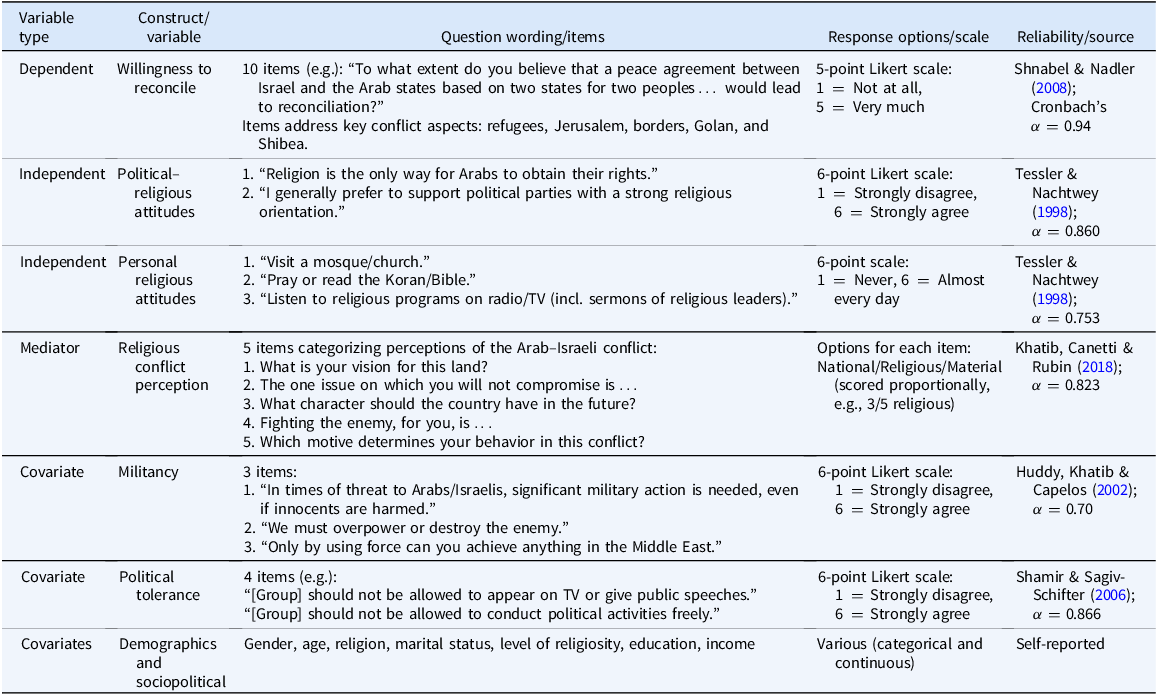

The study aimed to assess the impact of religious attitudes on civilians’ political attitudes toward reconciliation and tolerance in the conflict. Therefore, I have confirmed that the literature justifies the use of the survey variables and covariates based on this paper’s aims and hypotheses. As the literature review indicates, conflict perception has a mediating role between religious attitudes and reconciliation (Khatib et al., Reference Khatib, Canetti and Rubin2018). Militancy is incorporated as a proxy for extremism, which prior research (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Khatib and Capelos2002) links to both religious beliefs and political rigidity. Footnote 4 Additionally, religious attitudes can affect individuals, influencing their attitudes toward tolerance and intolerance (Little & Appleby, Reference Little, Appleby, Coward and Smith2004). Demographics (age, gender, income, religiosity level) are standard controls as they influence political and religious attitudes. Table 1 summarizes the variables and provides further detail.

Table 1. Definition of the study variables

Results and discussion

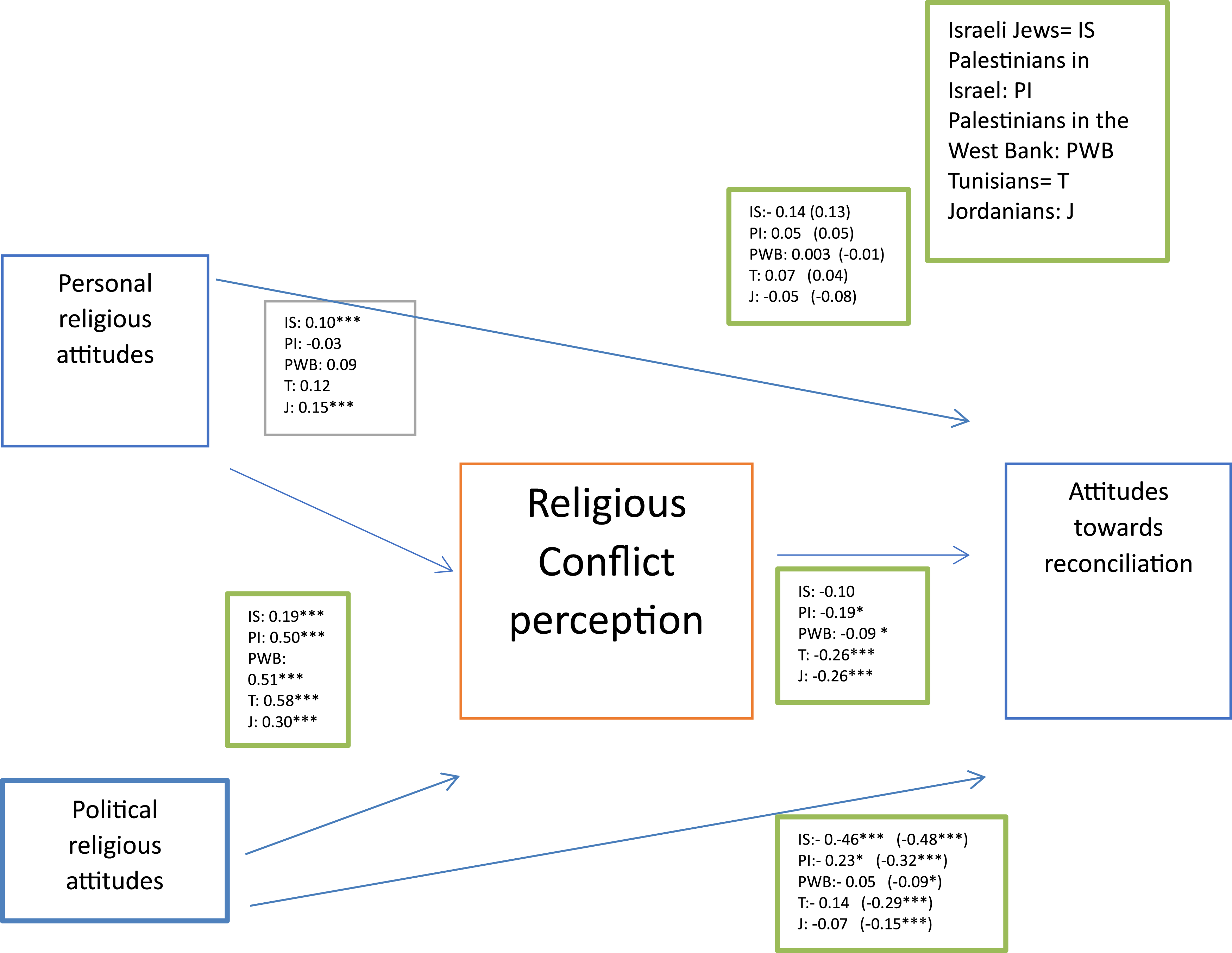

The results show that conflict perception mediates between personal religious attitudes, political–religious attitudes, and willingness to reconcile (see Figure 2). The results include regression coefficient values for the dependent variables, independent variables, covariates, and control variables and the significance of the findings among the various groups.

Figure 2. Research model results. (Numbers without parentheses indicate the direct effect, and numbers inside parentheses indicate the full effect.).

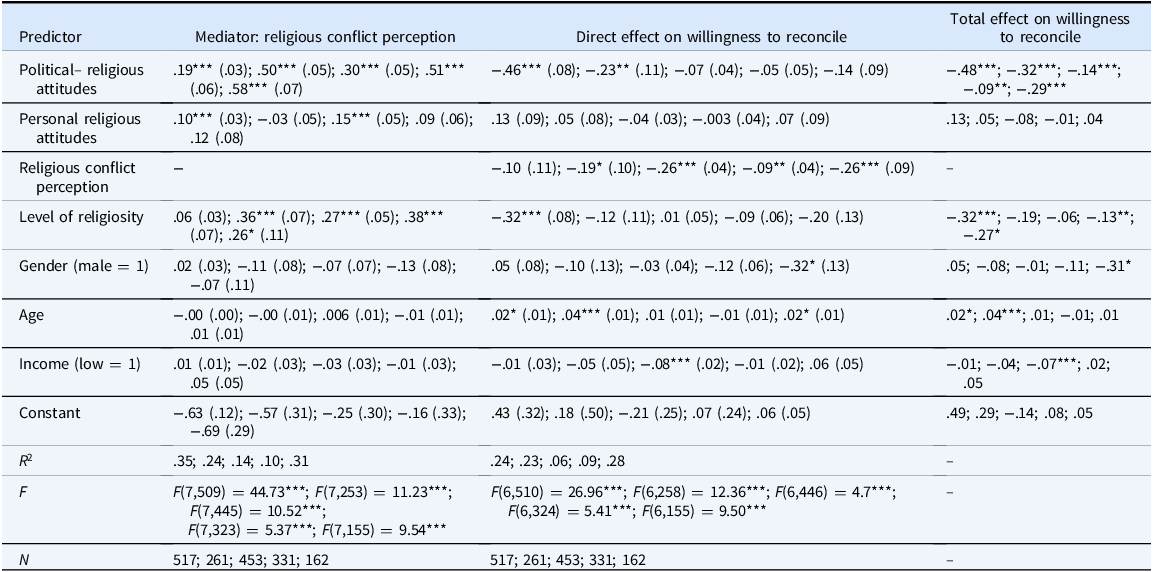

Table 2 explains the results illustrated in Figure 2, such as the difference between direct and total effects.

Table 2. Regression coefficients for mediation model: predicting religious conflict perception (mediator) and willingness to reconcile (direct and total effects)

Note: Results correspond to Jews, Palestinians in Israel, Jordanians, Palestinians in the West Bank, and Tunisians, respectively. These results are unstandardized; standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The results show that personal religious attitudes are not significantly correlated with the willingness to reconcile, but political–religious attitudes display a significant negative correlation with a willingness to reconcile in two cases (Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel). These findings partly support H1 and fully support H2. The results show a significant direct relationship between political–religious attitudes and reconciliation in some cases and a nonsignificant relationship between personal religious attitudes and reconciliation in all cases; however, political–religious attitudes are positively correlated with religious conflict perception across the five groups. These findings support H3. In the case of Jewish Israelis and Jordanians, personal religious attitudes correlated positively with religious conflict perception, which in turn correlated negatively (for both variables) and significantly (for Jordanians) with the willingness to reconcile. Religious conflict perception correlated negatively and significantly with reconciliation in all the cases (apart from Jewish Israelis, for whom it was negative but not significant).

The results show that personal religious attitudes cannot explain the rejection of reconciliation based on a two-state solution and concessions on the core issue of the conflict. Moreover, political–religious attitudes are shown to play a part in the popular unwillingness to reconcile; concurrently, religious conflict perception sheds further light on this rejection.

The results highlight the crucial role of religious conflict perception as a mediator in the relationship between political–religious attitudes and reconciliation, demonstrating how political–religious attitudes can influence reconciliation outcomes in conflict contexts. As the adjusted R-squared values in Table 2 show, the total effect is much higher than the direct effect of political–religious attitudes and reconciliation, whereas the correlation in the Israeli Jewish case increased from −0.46 *** to −0.48 ***; among Palestinians in Israel increased from −0.23 *** to −0.32 ***; among Jordanians increased from −0.07 to −0.14 ***; among West Bank Palestinians increased from −0.05 to −0.09 *; and among Tunisians increased from −0.14 to −0.29 ***. These results show that both political–religious perception and religious conflict perception can explain the rejection of reconciliation.

The previous results raised the question of whether political–religious attitudes foster “negative” perceptions of rival groups. For that purpose, I examined the relationship between personal and political–religious attitudes and militancy.

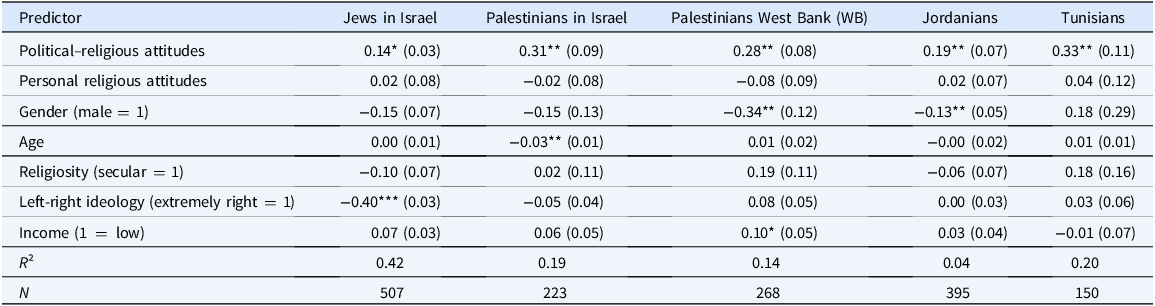

Table 3 and Figure 3 show that political–religious attitudes have a positive regression correlation with militancy in all cases (i.e., among Jordanians, Palestinians in Israel, Palestinians in the West Bank, Tunisians, and Israeli Jews). Regarding the regression correlation between personal religious attitudes and militancy, the results show that this regression is not significant across all cases, but it is positive. Figure 3 illustrates this relationship. The results show that in all cases, adopting political–religious attitudes correlates with significant adoption of militant attitudes among all parties in the conflict. Footnote 5

Table 3. Regression coefficients for political and personal religious attitudes on militancy by group

Note: These results are unstandardized; standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 3. Religious attitudes and militancy.

Although there are similarities in the results in different countries, the cross-country differences highlight the significance of contextual and structural factors in shaping how religious attitudes translate into political behaviors and conflict-related attitudes. The stronger effects observed among Israeli Jews and Palestinians in Israel, for example, may be attributed to their direct and daily engagement with the protracted Arab–Israeli conflict, which heightens the salience of political–religious attitudes and conflict perception. In contrast, the weaker associations in Jordan and the West Bank suggest that either alternative factors, such as political repression (due to the occupation), local governance structures, or distinct political cultures, moderate the influence of religion or that the conflict’s framing varies in these societies. Moreover, the relatively higher explanatory power in Tunisia could reflect the country’s unique post-revolutionary dynamics, where religion and politics have been reconfigured in recent years.

The findings can be interpreted in several ways. Not all of these explanations are equally valid, but they are interconnected and plausible given the data and existing scholarship. The first and most compelling explanation is that this rejection of reconciliation in the Arab–Israeli conflict may come as part of a consensus that does not differentiate between people who practice religious rituals and those who do not and which views the Palestinian cause as a liberation movement seeking justice for a people living under occupation (Khatib, Reference Khatib2022). Such a position has found support among a great many people who oppose reconciliation, as this research shows. In general, it may be said that the rejection of reconciliation in a conflict context is more related to political positioning and strategy, not to religious practices. This argument finds partial support (as the example is of supporting political movements), for example, in Tessler and Nachtwey’s (Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998) research, which states, “Individuals who report high levels of religious devotion in their individual lives do not possess attitudes toward the Arab–Israeli conflict that differ from those held by individuals with lower levels of religious devotion.”

Although Tessler and Nachtwey (Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998) reached similar conclusions, four main differences and contradictions were unearthed by this research. First, their research suggests that merely being supportive of political movements may lead people to reject reconciliation with Israel; however, this study’s results demonstrate a more nuanced relationship with religious conflict perception. Second, the results show that support for the political role of religion is decisive in shaping attitudes toward reconciliation, and it is not necessarily related to affiliation with a political party. Third, their survey results were published over two decades ago. Many changes have occurred in the region since then, including the Arab Spring, evolving views on relations with Israel at the state level, and the rise of Islamic parties. Fourth, it can be argued that the new findings in this research support the indirect role of personal religious attitudes in the rejection of reconciliation. These attitudes correlated positively with religious conflict perception (in some cases), leading to the rejection of reconciliation or peaceful attitudes like normalization (Khatib, Reference Khatib2025). These results show that the more pious one is, the more likely one is to understand the conflict itself in religious terminology.

Further, the conclusions show that religion’s role in shaping attitudes in the conflict context, based on a system of beliefs and practices that determines what it means to be pious, owes to its significance to its followers (Kadayifci-Orellana, Reference Kadayifci-Orellana2009). Framing the conflict in religious terms and presenting reconciliation as a matter of faith drives adherents to reject reconciliation due to their religious beliefs that lead to the rejection of reconciliation if it is not based on values like justice and rights.

Second, a religious faith that transcends personal practice strengthens one’s ability to adopt a position on the political agenda. In the context of conflict, religious or nationalist ideology can lead people to adopt militant attitudes (Hegghammer, Reference Hegghammer2011). Thus, if political–religious attitudes are viewed as part of ideologies with a political dimension, they can explain the rejection of reconciliation better than the apolitical, non-ideological aspects of religion that concern daily worship. Religious attitudes that are separate from political beliefs tend to confine individuals to the private sphere, limiting their public engagement. Personal religious views shape their understanding and restrict them from taking political positions based on political–religious beliefs.

Third, political–religious attitudes can be a precursor to religious conflict perception, which in turn deepens objection to reconciliation because religious conflict is defined in relation to the political ambitions of actors espousing religious motivations for the policies they seek to make a reality (Khatib, Reference Khatib2018). This kind of conflict can happen between various religious groups with different ideologies (Fox, Reference Fox2004); however, compromise remains difficult in any instance of religious conflict perception (Tabory, Reference Tabory1981; Khatib, Canetti & Rubin, Reference Khatib, Canetti and Rubin2018; Canetti et al., Reference Canetti, Khatib, Rubin and Wayne2019), as opposed to material or national conflict perceptions. Additionally, religious beliefs can lead to a religious conflict perception and thus the refusal to reconcile, given the land’s potential religious symbolism and importance, which can obstruct compromise (Goddard, Reference Goddard2006); with the Arab–Israeli conflict, of course, both groups believe the land to be sacred. The Israeli Jews who hold political and religious views related to the conflict reject reconciliation, as their beliefs are rooted in religious justifications that view Palestinian land as sacred Israeli land and do not accept any compromises. This group of religious individuals is aligned with the right wing and believes in the role of religion in public life. On the Arab side, religion plays a major role, both from a moral and values perspective (like justice) and in shaping beliefs about the conflict, particularly regarding issues like Jerusalem and land.

Fourth, the theory of “just war” argues that violence and conflict can be motivated by the pursuit of justice (Cordeiro-Rodrigues & Singh, Reference Cordeiro-Rodrigues and Singh2020) and the existence of a just cause (Edmund, Reference Edmund2021). The latter can become a moral point of reference for combatants during the war; however, the concept is used primarily as a narrative to substantiate a war or armed conflict and to adopt certain ethics during the conflict, not to characterize conflicts that are just (Neusner, Chilton &Tully, Reference Neusner, Chilton and Tully2013). In the context of the Arab–Israeli conflict, elements of the pursuit of justice receive great consideration on the Arab side as the Palestinians’ chief aim; the Israeli occupation of Arab territory and systematic violation of Palestinians’ human rights and personal freedoms (Bishara, Reference Bishara2022) color the conflict as unjust, which explains their repudiation of any proposed reconciliation. Justice plays a crucial role in accepting and realizing reconciliation (Edmund, Reference Edmund2021). Reconciliation is a psychological process that involves accepting and respecting one another (Baysu, Coşkan & Duman, Reference Baysu, Coşkan and Duman2018). However, deep-seated injustice and unjust resolution of conflicts between groups can impede this process.

Finally, the results can be attributed to the concept of “cheap reconciliation,” which entails accepting peace and reconciliation without addressing justice and unresolved grievances (Volf, Reference Volf2000). According to this perspective, “to pursue cheap reconciliation means to give up on the struggle for freedom, to renounce the pursuit of justice, to put up with oppression” (Volf, Reference Volf2000, p. 867). Therefore, rejection of reconciliation can stem from the belief that the process relies on cheap reconciliation and fails to address the root causes of the conflict and grievances. The general willingness of Israeli Jews to reconcile is rooted in the belief that reconciliation is necessary and acceptable if it is based on a two-state solution that accommodates Israeli demands. However, this form of cheap reconciliation is not accepted by Arabs in general due to high levels of grievance.

In summary, the results provide support for the first three interpretations outlined in this section, which are reinforced by the prior literature. Together, these explanations reveal how political–religious attitudes and religious conflict perception interact to strengthen opposition to reconciliation, especially when the conflict is understood through a religious and ideological lens. This dual mechanism, rooted in political religiosity and deepened by viewing the conflict as religious, helps explain persistent resistance to reconciliation in the context of the Arab–Israeli conflict. Importantly, the data also indicate that the rejection of reconciliation is not only driven by religious or ideological commitments but also by the lived reality of the conflict and the perception of enduring injustice, particularly on the Arab side. Many respondents frame reconciliation efforts as insufficient or superficial when they fail to address core issues of justice, rights, and historical grievances. Thus, while political–religious attitudes and conflict perception explain much of the variation in attitude, they are deeply intertwined with broader structural realities that continue to shape perceptions of the conflict and possible resolutions.

Personal and political–religious attitudes and tolerance

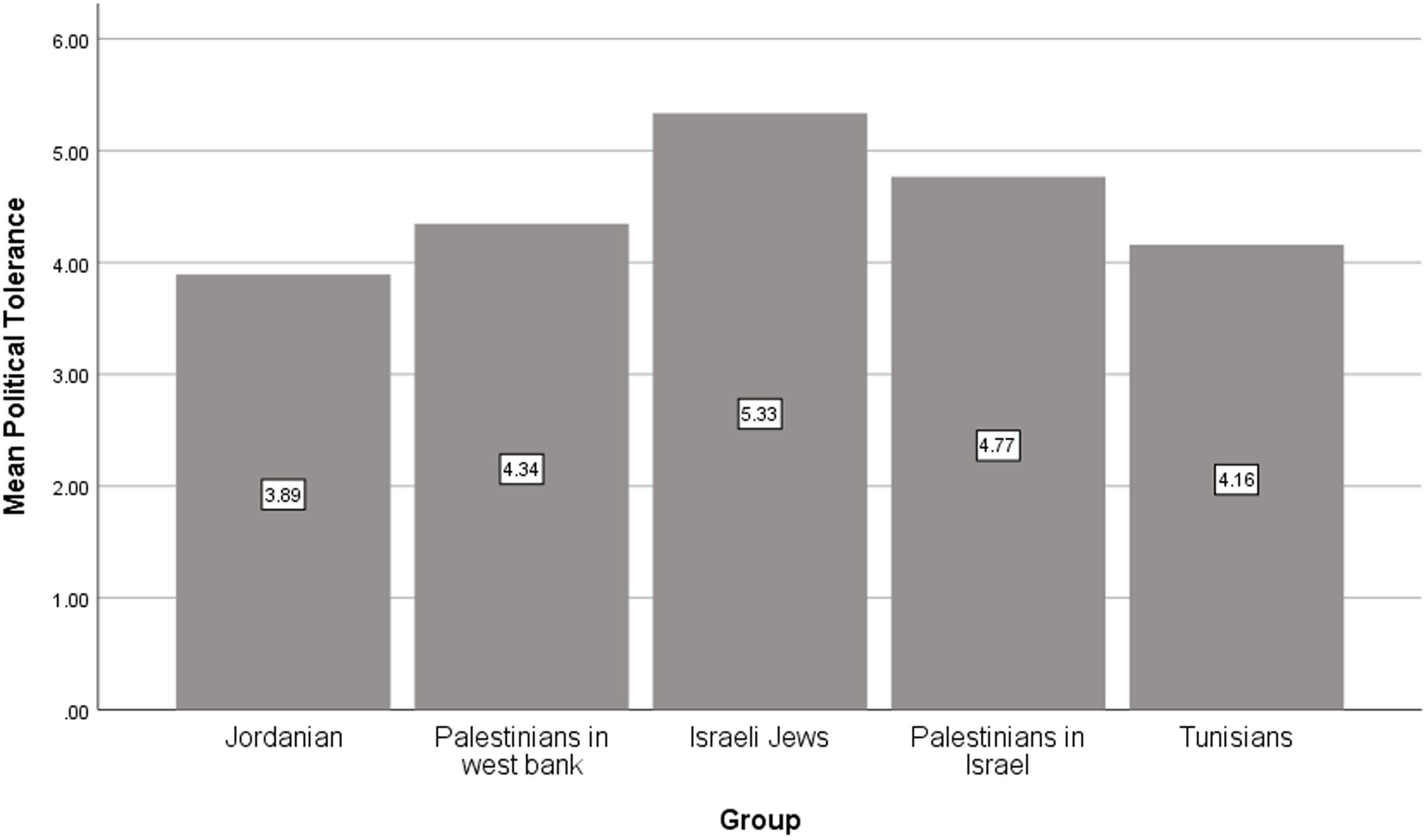

The results pose the question of whether political–religious attitudes always beget negative attitudes toward others. In the former case, I am referring to reconciliation and militant attitudes toward multinational, protracted conflict within the Middle East. In the latter case, I checked the personal and political–religious attitudes and tolerance in an internal conflict between different social groups within the state (secular vs. religious). The general results on tolerance show that the majority are tolerated more than the mean, as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4. Mean of political tolerance.

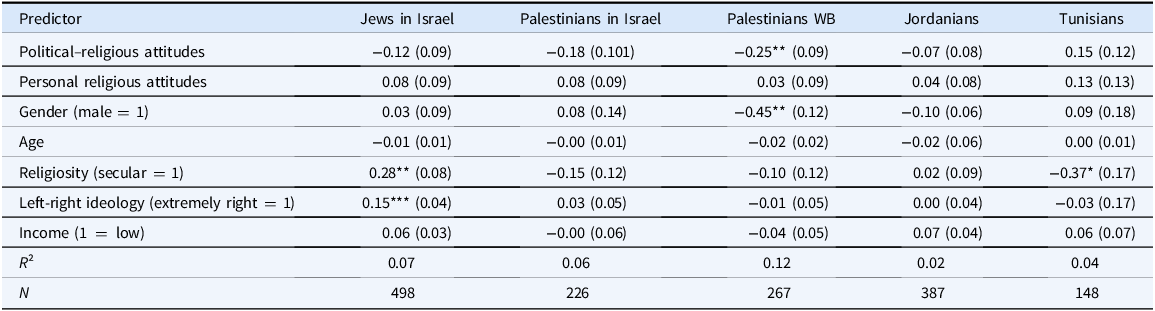

I checked the regression correlation between political–religious attitudes and tolerance for other groups in society (in all the samples, religious respondents were asked about secular groups and vice versa). The results showed that the correlation between Jordanians, Israeli Jews, Palestinians in Israel, and Tunisians was not significant, despite being negative between Palestinians in the West Bank.

The regression correlation between personal religious attitudes and tolerance was positive but nonsignificant across all groups, which means that the adoption of personal religious attitudes cannot explain political tolerance (see Table 4). These findings support H4.

Table 4. Regression coefficients for political and personal religious attitudes on political tolerance by group

Note: These results are unstandardized; standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 5 illustrates these relationships.

Figure 5. Religious attitudes and tolerance in the context of internal political dispute.

Therefore, adopting neither political–religious attitudes nor personal religious attitudes leads to intolerance between religious and secular groups (on the national level). Nevertheless, secular–religious cleavages appeared in these countries as the main fragmentation and point of political contention.

I cannot say with certainty that secular–religious cleavages led to violent conflicts; however, they have played a role in Middle Eastern societies’ internal conflicts and polarization. According to the literature, this kind of conflict (i.e., secular–religious) is less negotiable than other varieties (Reynal-Querol, Reference Reynal-Querol2002; Fox, Reference Fox2004; Hassner, Reference Hassner2017). These results show that religious attitudes (either personal or political) do not necessarily lead to rejection of other groups or the outbreak of civil war, as has been claimed by some scholars (Grewal & Cebul, Reference Grewal and Cebul2023). These results may add to the recent studies on religion and intergroup relations. For example, the findings of Masoud, Jamal, and Nugent (Reference Masoud, Jamal and Nugent2016) state that having some understanding of the rival group’s religion promotes the acceptance of others and other norms like women’s equality. Additionally, according to Grewal and Cebul (Reference Grewal and Cebul2023), religious reinterpretation can reduce secular–religious polarization. However, these results show that political and personal religious attitudes alone can neither promote nor reject tolerance between groups. While Islamic political affiliation (political Islam) may correlate negatively with tolerance according to Spierings (Reference Spierings2014), this does not imply that political–religious attitudes inevitably lead individuals to reject other groups (Spierings, Reference Spierings2014). These results show that negative attitudes or reservations toward reconciliation with others are by no means constant among those who have adopted political–religious attitudes; rather, they are based on political or moral considerations and the nature of the conflict, as in the case of this research on the Arab–Israeli conflict.

Three explanations can be given for these results; the first and most supported explanation is that people adopt either personal or political–religious attitudes, and being more secular or more religious does not affect their attitudes. They may accept one another and live together rather than reject each other because they think intolerance is impossible, as they share their fate as part of one community (Verdeja, Reference Verdeja2009, p. 170). The relatively high level of tolerance, regardless of religious attitudes, can be explained by this feeling. In addition, some religious norms that reject intolerance can also be part of this belonging and shared life.

The second, and more politically salient explanation, is that the relationship between religious commitment and political intolerance is not direct and is mediated by other factors such as psychological security (Eisenstein, Reference Eisenstein2006) and the high democratic values adopted by people in these communities (Khatib, Reference Khatib2022). In addition, tolerance serves as an indicator of popular support for democracy (Karpov, Reference Karpov1999; Lee, Reference Lee2014), and previous research suggests that the populations studied demonstrate both high democratic values (Khatib, Reference Khatib2022) and a strong political will to implement democratic practices (Khatib & Ghanem, Reference Khatib and Ghanem2018). Furthermore, age and education can explain political tolerance (Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Marcus, Feldman and Piereson1981). An additional factor related to the case study is the context of the Middle East: the experience of the Arab Spring and the transformation from revolutions to civil wars with a high number of fatalities led people, despite the polarizations including religious–secular, to decide to live together; political or personal religious attitudes became irrelevant for tolerance while social stability became the cornerstone of their relations, which explains the acceptance of tolerance (Cheah, Reference Cheah2004).

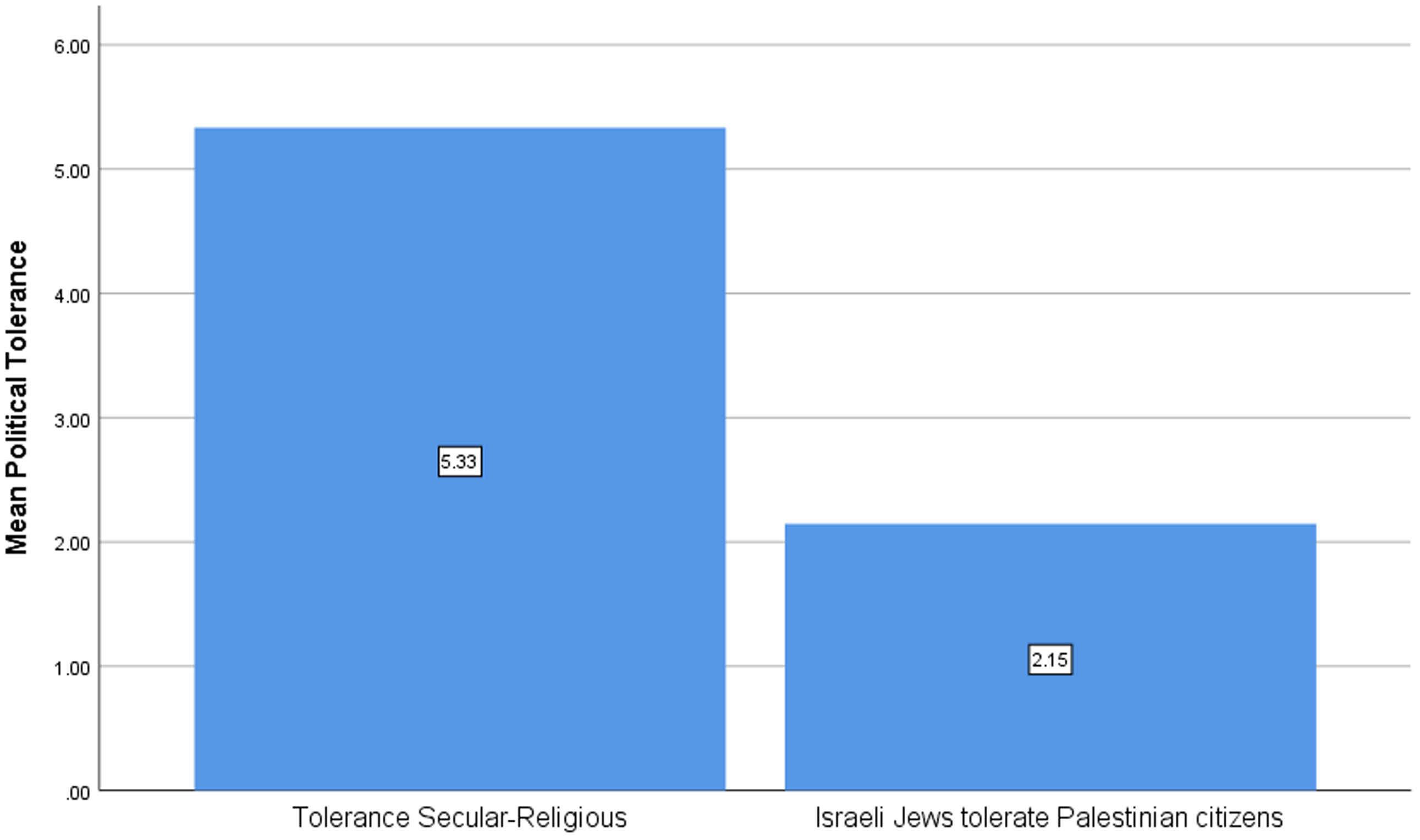

Finally, external conflicts and threats may transform hostilities from intragroup to intergroup conflicts. For that reason, I analyzed another group that is part of the state but is also perceived to be part of the conflict. I analyzed tolerance toward the Palestinians in Israel among the Israeli Jews and found very low tolerance among the Israeli Jews toward Palestinian citizens (see Figure 6), despite them holding Israeli citizenship. This shows the centrality of the protracted intergroup conflict.

Figure 6. Political tolerance toward religious–secular and Palestinian citizens among the Israeli Jews.

The existing literature supports the first explanation; however, future research should test these interpretations more systematically by incorporating direct measures of psychological security, perceptions of democratic norms, and the salience of external threats. Together, these results suggest that although religion shapes perceptions and identities, political tolerance is shaped more by broader political, psychological, and conflict dynamics than by religious attitudes alone.

Taken together, the findings reveal a consistent pattern across countries: political–religious attitudes are the most reliable predictors of both willingness to reconcile and militancy, whereas personal religious attitudes show minimal or inconsistent effects. This pattern is evident in Israel, Palestine, Jordan, and Tunisia; however, the strength of the relationships varies by context. Additionally, conflict perception as religious mediates the relationship between political–religious attitudes and reconciliation in several countries, especially among Palestinians in Israel, Jordanians, and Tunisians, but less so among Israeli Jews. The role of demographic variables like gender, age, and income also differs, but their effects are generally weaker compared to the influence of political religiosity and conflict perception. The analysis of political tolerance yielded weaker and less consistent associations, while the cumulative results across models suggest that the intersection of political–religious attitudes and conflict perception is the central mechanism shaping both intergroup reconciliation and militant dispositions.

Conclusion

This research sought to address how political and personal religious attitudes correlate with attitudes toward reconciliation and tolerance in intergroup and intragroup conflicts. There is a dearth of recent data in the literature on the role of personal and political–religious attitudes in protracted conflicts, such as the Arab–Israeli conflict and the internal political unrest that followed the Arab Spring. Further, the existing scholarship does not address the role of religious conflict perception, which is a recently developed and measured concept (see Khatib, Canetti & Rubin, Reference Khatib, Canetti and Rubin2018; Canetti et al., Reference Canetti, Khatib, Rubin and Wayne2019), as a factor that can mediate between personal and political–religious attitudes and reconciliation. In addition, the literature needs to clearly define the relationship between religion, conflict, and peaceful attitudes, and this research tries to examine this relationship.

Some scholars see religion as a source of conflict, whereas others disagree with the argument that such an association is inevitable. Abu-Nimer, Kadayifci-Orellana, and Weigel describe peaceful attitudes that are promoted by religion (Abu-Nimer, Reference Abu-Nimer2003). As addressed in this paper, the role of religion appears more nuanced, indicating that its relationship to reconciliation and tolerance is much more complicated.

The results show that, in the context of a protracted conflict perceived as a struggle for justice and heavily laden with religious and political dimensions, people who adopt political–religious attitudes tend to perceive the conflict as religious and reject the notion of reconciliation, which is seen as unjust. In the case of internal conflicts, political–religious attitudes are not necessarily correlated with intolerance, and this result may be understood as part of society’s diversity, which is respected. Previous studies suggest that religion can promote empathy, nonviolence, and tolerance (Philpott, Reference Philpott2007) even when tensions are high between groups. Further, the results show that personal religious attitudes alone cannot explain the rejection of reconciliation. Conversely, political–religious attitudes have demonstrated explanatory power toward popular rejection of any willingness to reconcile, and religious conflict perception can simultaneously improve this explanation. These results are supported by the existing literature (Juergensmeyer, Reference Juergensmeyer2017; Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2016). Conversely, some argue that religion offers resources for peace (Garred & Abu-Nimer, Reference Garred and Abu-Nimer2018; Kadayifci-Orellana, Reference Kadayifci-Orellana2009). Although the results suggest a negative relationship between political–religious attitudes to the desire for reconciliation and a positive relationship to militancy, this depends on the nature and circumstances of the conflict. This negative correlation does not exist when examining the relationship between political–religious attitudes and tolerance in contexts of internal political conflicts, nor is there evidence of a significant relationship when addressing the correlation between personal religious attitudes and reconciliation. Further, the findings can be explained by the “just war” theory, which cites the pursuit of justice as a central motivation and a decisive factor in determining attitudes toward conflict and violence; in the Arab–Israeli case, the injustice endemic to the continual violation of Palestinian civil and human rights serves as a moral justification for their rejection of reconciliation. Religions support the values of justice and denunciations of injustice and are part of the faith (Volf, Reference Volf2000). However, although religion may support peaceful attitudes (Abu-Nimer, Reference Abu-Nimer2001), it seems that values of justice and rights are more important than peace among religious believers in the Arab states, particularly in contexts where reconciliation is regarded as insincere or “cheap.” Therefore, the rejection of reconciliation in the context of the Arab–Israeli conflict is based on adopted values (Khatib, Reference Khatib2022). Whether adopted by the religious or the non-religious, the deployment of religious justifications can heighten the impact of this refusal if the conflict has a religious dimension. Here, I cite Islamist political leader Rashied Al-Ghannushi (Reference Al-Ghannushi2014), head of the Tunisian Ennahda party, who has emphasized his support for the Palestinian cause as it is in pursuit of liberation and great sanctity. The nonsignificant correlation between personal religious attitudes and reconciliation can be explained by the limited role of these attitudes in shaping political positions.

Among the Jewish believers, other factors (like interests) and interpretations allow some to accept reconciliation with the Arabs; however, political–religious perception correlated positively with militancy among the Israeli Jews, which can be explained by the reality of the conflict and its religious aspects. It can be observed that the political–religious groups in the occupied territories use violence and religious explanations in support of these attitudes.

Finally, considering religious conflict perception as the main factor in determining attitudes toward reconciliation, Oren, Bar-Tal, and David (Reference Oren, Bar-Tal, David, Lee, McCauley, Moghaddam and Worchel2004) argue that each rival group, through its involvement in a dispute, adopts an ethos of conflict related to its social identity. This ethos serves as the epistemic basis by which a group may perceive the conflict based on their identity. As I have observed, the religious sense of identity that emphasizes the special position of Palestine and Israel and views the conflict as a zero-sum game may lead people, especially those with religious perceptions, to reject reconciliation.

The relationship between political and personal religious attitudes and tolerance shows that religious attitudes do not necessarily have a deterministic correlation with non-peaceful attitudes in group relations. The results indicate that this relationship is related to the context and values that people may adopt.

Previous results support the constructivist approach that religion can justify or reject violence or peace based on the case and the interpretation of holy texts related to the context (Hasenclever & Rittberger, Reference Hasenclever and Rittberger2000). Although the results show that the role of religion can vary depending on the case and the context, this is not contradictory to approaches in which religion is used to justify the use of violence and is instrumental in achieving political or economic goals that have caused the conflict (Hasenclever & Rittberger, Reference Hasenclever and Rittberger2000).

The theoretical and empirical results of this research contribute to the understanding of the role of religion in intergroup relations in countries with high rates of religious affiliation that are facing conflict. In addition, this article has highlighted the importance of religious conflict perception and the role of attitudes toward the other side in perpetuating an unwillingness to reconcile. This religious conflict perception may partially explain attitudes toward reconciliation even when it is not broadly accepted, given the complexity of conflicts and the conventional wisdom of how they may be resolved. In addition, the findings point to the robustness of political–religious attitudes as a driver of intergroup attitudes, while also highlighting the importance of considering how conflicts are framed within religious or national narratives. In this way, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how religion interacts with political events and conflict perceptions to influence political behavior and social cohesion.

The findings invite us to reexamine religion’s role in protracted conflicts. The results are based on a student sample (i.e., the younger generation); however, recent studies have shown that student samples can be representative (Druckman & Kam, Reference Druckman and Kam2009). The results may reflect the attitudes of the younger generation, the largest population segment in the Middle East, as a microcosm of the whole population. Finally, although the findings reveal a general pattern in which political–religious attitudes and conflict perceptions influence reconciliation and tolerance across contexts, the strength and pathways of these effects vary by country. This reflects each society’s unique political conditions, conflict proximity, and experiences. Further research for each community is warranted.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Financial support

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ibrahim Khatib is an Assistant Professor of Conflict Management in the Conflict Management and Humanitarian Action program at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies and a Research Associate in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford. His research examines conflict resolution, democracy, religion, protest, and the politics of the Middle East, particularly in relation to internal conflicts and regional transformations. He completed his Ph.D. in Political Science at Humboldt University of Berlin and was a fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. His work has been published in journals including Journal of Peace Research, Democratization, International Journal of Conflict Management, Citizenship Studies, and Ethnopolitics, among others.