In August 2025, the world commemorated eighty years since the atomic bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These two events took place just three days apart and are the only instances when the world’s most powerful weapons were used in a military conflict. For international relations and security studies scholars, the continued reluctance by nuclear-armed states to employ their arsenals – even when fighting and losing major wars – remains a significant puzzle. The field has even recently witnessed a genuine renaissance in ‘nuclear taboo’ scholarship, marked by a wave of population surveys and survey experiments investigating micro-level attitudes towards the use of nuclear weapons.Footnote 1 According to the Nuclear Taboo Database,Footnote 2 of the approximately ninety academic articles published on this subject in the past decade, more than 40 per cent used surveys as their primary research method.Footnote 3

However, this ‘second wave’ of nuclear non-use scholarship has also faced persistent criticism for surveying the general public to examine the traditionally elite domain of nuclear policy.Footnote 4 While a foundational experimental study by Daryl Press, Scott Sagan, and Benjamin Valentino suggested that ‘elites may not differ dramatically from the general public in their views toward nuclear weapons’,Footnote 5 subsequent research has shown significant elite–public gaps in attitudes towards nuclear strikes.Footnote 6 Even if the public and elites think differently about nuclear decisions, some scholars have proposed that public opinion could constrain or enable elite decision-making on the military use of nuclear weapons.Footnote 7 Others are more sceptical about the relevance of public views in the nuclear domain writ large.Footnote 8

Employing the bomb in an international conflict would constitute a level of escalation unprecedented since World War II and have global consequences. Factors that shape nuclear choices should therefore be of paramount importance to the study of foreign policy. Yet, scholars still lack experimental evidence demonstrating whether and how decision-makers are responsive to public sentiments about using nuclear weapons. Both the practice of nuclear policy and the utility of more than a decade of nuclear (non-)use scholarship hinge on the answer to this question.

We designed and pre-registered an original survey experiment to address this critical gap. We fielded the survey to a sample of members of the British parliament and American and British government employees working on policy issues. Depending on their nationality, we asked the participants to imagine themselves as high-level advisors to the US president or UK prime minister. In turn, we presented them with fictional crisis scenarios depicting the most likely, real-world cases for the use of nuclear weapons. The three scenarios described considerations of nuclear first use in response to an Iranian chemical weapons attack, nuclear retaliation in response to a North Korean nuclear strike, and a third-party observation of a nuclear conflict between India and Pakistan. By experimentally manipulating levels of public support for nuclear strikes in individual countries, we tested three hypotheses about the impact of public opinion on elite beliefs and preferences: 1) elites consider bottom-up ‘public cues’ when forming their own preferences regarding nuclear weapon use; 2) information about public opinion leads to belief updating about the likelihood of nuclear use by the country’s leaders; and 3) public opinion in favour of nuclear weapon use makes nuclear threats more credible to outside observers.

The results of our study provide important theoretical and empirical insights into the role of public opinion in elite decision-making on using nuclear weapons. In the scenario involving Iran’s chemical weapons use, we found strong evidence that public support for nuclear strikes shaped our participants’ attitudes. When the public backed nuclear strikes, participants across samples were significantly more willing to support nuclear use and more likely to believe that their country would employ nuclear weapons. In the scenario involving nuclear retaliation to a North Korean nuclear attack, the evidence was mixed. Public opinion influenced UK government employees, but we found no statistically significant effect among US government employees and UK parliamentarians. Finally, we found consistent support for our third hypothesis in the scenario involving an Indian threat to use nuclear weapons against Pakistan. Across all samples, India’s nuclear threats were deemed to be more credible when backed by sympathetic public opinion.

Our findings have considerable implications for scholarly literature on public attitudes towards nuclear weapon use. We provide the first experimental evidence that, when it comes to high-level political decisions about violating the ‘nuclear taboo’, elites are likely to be at least partially responsive to public sentiments. Survey experiments conducted on population samples therefore investigate attitudes with legitimate real-world relevance to elite decision-making. This is arguably of increasing significance in today’s highly volatile ‘third nuclear age’, in which a growing number of nuclear stakeholders – including new potential proliferators and advocacy groups – shape global nuclear politics.Footnote 9

However, our study also suggests that there are limitations to the role of the public in the nuclear domain. Specifically, we find that public views may be less relevant for nuclear retaliation decisions after the nuclear taboo has been broken. Given that the retaliatory use of nuclear weapons is more closely aligned with most nuclear-armed states’ strategic doctrines than nuclear first use, this finding is worthy of note.

Finally, we show that beliefs about the likelihood of nuclear strikes by third countries are affected by information about public support in those countries. This finding implies that nuclear threats may be more credible when backed by sympathetic public opinion, making public opinion a pertinent and understudied factor for the literature on coercive bargaining in nuclear crises.Footnote 10 Put simply, public opinion can impact the practice of effective nuclear deterrence by states.

We proceed as follows. First, we discuss our theoretical expectations and hypotheses regarding how public opinion may shape elite beliefs and preferences. Second, we introduce our experimental research design. Third, we present results for each of the three scenarios in our study. Fourth, we discuss our findings and their contribution in the context of existing literature. We conclude by highlighting the scholarly and policy relevance of our work and proposing future research avenues.

Theoretical expectations and hypotheses

The original theory behind the post–World War II ‘nuclear taboo’ in world politics considered public opinion to be a relevant causal factor. In a seminal articleFootnote 11 and subsequent book,Footnote 12 Nina Tannenwald found that US decision-makers acutely felt the public opposition to nuclear weapon use that emerged after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. According to Tannenwald, public views were one of the main constraints against Washington using nuclear weapons in its conflicts with North Korea, China, North Vietnam, and other adversaries. Public opinion has also been central to the rationalist ‘tradition of nuclear nonuse’. T. V. Paul accordingly argued that reputational concerns – partially connected with expected public disapproval – lead to self-deterrence and iterated nuclear non-use practices.Footnote 13

However, some of the original experimental findings raised concerns that public opinion would more likely act as an enabler for nuclear weapon use in a crisis rather than a constraining force. A highly publicised survey experiment by Scott Sagan and Benjamin Valentino found that more than half of Americans would prefer nuclear first use against a densely populated city in Iran – and almost 60 per cent would approve of such a decision – to avoid a costly ground invasion.Footnote 14 Joshua Schwartz has found that the American public would be surprisingly supportive of nuclear strikes conducted by allied or partner countries.Footnote 15 Building on these findings, Damon Coletta suggests that ‘when calibration is critical for the American president, the public will clamor for a decisive, wildly disproportionate response […] the irrational mob will expect its elected leader to pursue vigilante justice rather than calculated crisis management’.Footnote 16

Other scholars in the ‘second wave’ of nuclear taboo research have nevertheless found that concerningly high public support for nuclear strikes can be significantly reduced by priming. Charli Carpenter and Alexander Montgomery, for example, demonstrated that reminding respondents of existing ethical and legal norms against civilian targeting decreased support for saturation bombing of a city in the aforementioned Iran scenario.Footnote 17 Lisa Koch and Matthew Wells showed that vivid descriptions of the aftermath of a nuclear blast reduce both public preferences for and approval of nuclear weapon use.Footnote 18 In an experiment conducted on samples of the US and South Korean publics, Lauren Sukin found that adversary signals of nuclear restraint reduce support for nuclear strikes, and support for nuclear first use against Russia and North Korea is low.Footnote 19 In a cross-national study conducted on Japanese, South Korean, and American citizens, David Allison, Stephen Herzog, and Jiyoung Ko also demonstrated low levels of public support for nuclear strikes against North Korea in both first-use and retaliation scenarios.Footnote 20 These important findings generally support the notion that public opinion can serve as a constraining factor in elite decision-making in nuclear crises.

Ultimately, the debate over the potential constraining and enabling effects of public opinion boils down to the question of whether political elites are responsive to public preferences. In the domain of foreign policy, the original view in the discipline was that public opinion lacked structure and did not significantly influence government decisions.Footnote 21 More recent research has questioned these assumptions.Footnote 22 Scholars have identified several empirical cases in which the views of voters directly influenced the policies pursued by elected officials.Footnote 23 In fact, elite responsiveness to public sentiments is often proposed as the (micro)foundation of prominent IR theories.Footnote 24 For example, domestic audience cost models of crisis bargaining indicate that leaders strategically tie their hands by issuing public threats.Footnote 25

Importantly, the rise of elite experiments in IRFootnote 26 has provided new ways to test these actors’ responsiveness to public views. A study conducted on Israeli Knesset members found that they were more willing to employ military force when the Israeli public supported such actions. They exhibited fear of political consequences that might arise from contravening public preferences.Footnote 27 Another survey experiment demonstrated that UK parliamentarians’ views on the country’s military presence in the South China Sea were influenced by exposure to public polling.Footnote 28 Furthermore, a 2025 study showed that public opinion affected US foreign policy practitioners’ preferences regarding the imposition of economic sanctions on Russia.Footnote 29 These and other studies point to the cross-national importance of public opinion in structuring foreign policy outcomes.

The dynamics identified above can be described as a mirror counterpart to the ‘elite cues’ scholarship. This body of literature examines how political, military, and other elites shape public attitudes on foreign policy through strategic communication.Footnote 30 Top-down messaging has the potential to shape public views on different international issues, but public opinion simultaneously provides bottom-up ‘public cues’ that elites could see as either a political constraint or an enabler for policy choices. Whether and how much elites take public cues into account remains an empirical question, though there are compelling reasons why elites might care about public attitudes. Defying public preferences may have implications for the political careers of some elites, such as diminishing re-election prospects or tarnishing their legacies.

Yet, there are clearly other elite considerations involved, such as the long-term strategic impact of a policy, one’s own normative stance, and views of other domestic and international elites. All these factors and others can ultimately prove to be significantly more important in elite decision-making than the public mood.Footnote 31 Using the bomb carries enormous strategic and political implications that could override even supportive public opinion. To this end, earlier research has found strong elite aversion to nuclear weapon use even in situations when a nuclear strike would provide major military advantages over a conventional strike.Footnote 32 As such, elite decisions regarding nuclear strikes represent a very hard test for identifying potential causal effects of public cues. To see whether the mechanism of elite responsiveness would pass an empirical test in the nuclear domain, we pre-registered our first hypothesis:

H1. Political elites are more supportive of the use of nuclear weapons when public support for nuclear use is high than when it is low.

We contend that public cues are not the only mechanism through which public opinion can influence elite decision-makers. Evidence from wargames suggests that elites often have strong views on nuclear weapons and may be resistant to recommending or supporting nuclear strikes.Footnote 33 It is, therefore, possible to imagine a situation in which political elites remain firm in their preferences – irrespective of information about public opinion – due to strong convictions about the strategic, political, or normative appropriateness of a given action. However, they may still believe that other political elites will be affected by public sentiment. As a result of this change in beliefs about political dynamics, elites might alter their behaviour. For example, they might proactively put forward new arguments or build new political coalitions to prevent undesirable outcomes. To test elites’ belief updating in the domain of nuclear weapon (non)use, we pre-registered our second hypothesis:

H2. Political elites believe that their country’s leaders are more likely to favour the use of nuclear weapons when public support for nuclear use is high than when it is low.

Finally, we argue that information about public support for nuclear use could shape the beliefs of third-party observers. Indeed, perceptions and intelligence assessments of others’ nuclear decisions help to form the basis for national policy formulation.Footnote 34 It is conceivable that political elites believe that ‘our’ leaders are not easily swayed by public opinion in high-level nuclear decisions, but they may well believe that ‘their’ leaders in other countries are affected by such sentiments. Asymmetric perceptions are consistent with the logic of attribution biases and ‘us versus them’ dichotomies. ‘Us’ is considered to be firmer and more principled in international affairs, whereas ‘them’ is more swayed by domestic political factors such as fluctuating public opinion.Footnote 35 If this argument holds, it suggests critical ramifications for coercive bargaining in nuclear crises and the practice of nuclear deterrence.Footnote 36 All else equal, threats issued by states in which public opinion supports nuclear weapon use should be perceived as more credible by outside observers than threats without such public backing. Drawing on this logic, we formulated our third hypothesis:

H3. Political elites are more likely to find third-party nuclear threats credible when public support for using nuclear weapons is high than when it is low.

Taken together, these hypotheses offer testable insights into whether and how public opinion might affect elite decision-making on the most critical political–military choice facing nuclear-armed states: to use the bomb or not in an international conflict. Several studies referenced above showed that public views can shape elite preferences in various foreign policy domains. But the field lacks clear evidence that public opinion carries implications for nuclear weapon use. Thus, rigorous testing of our three propositions would help scholars answer pivotal questions about the utility of survey experiments conducted on public samples.Footnote 37

Experimental design

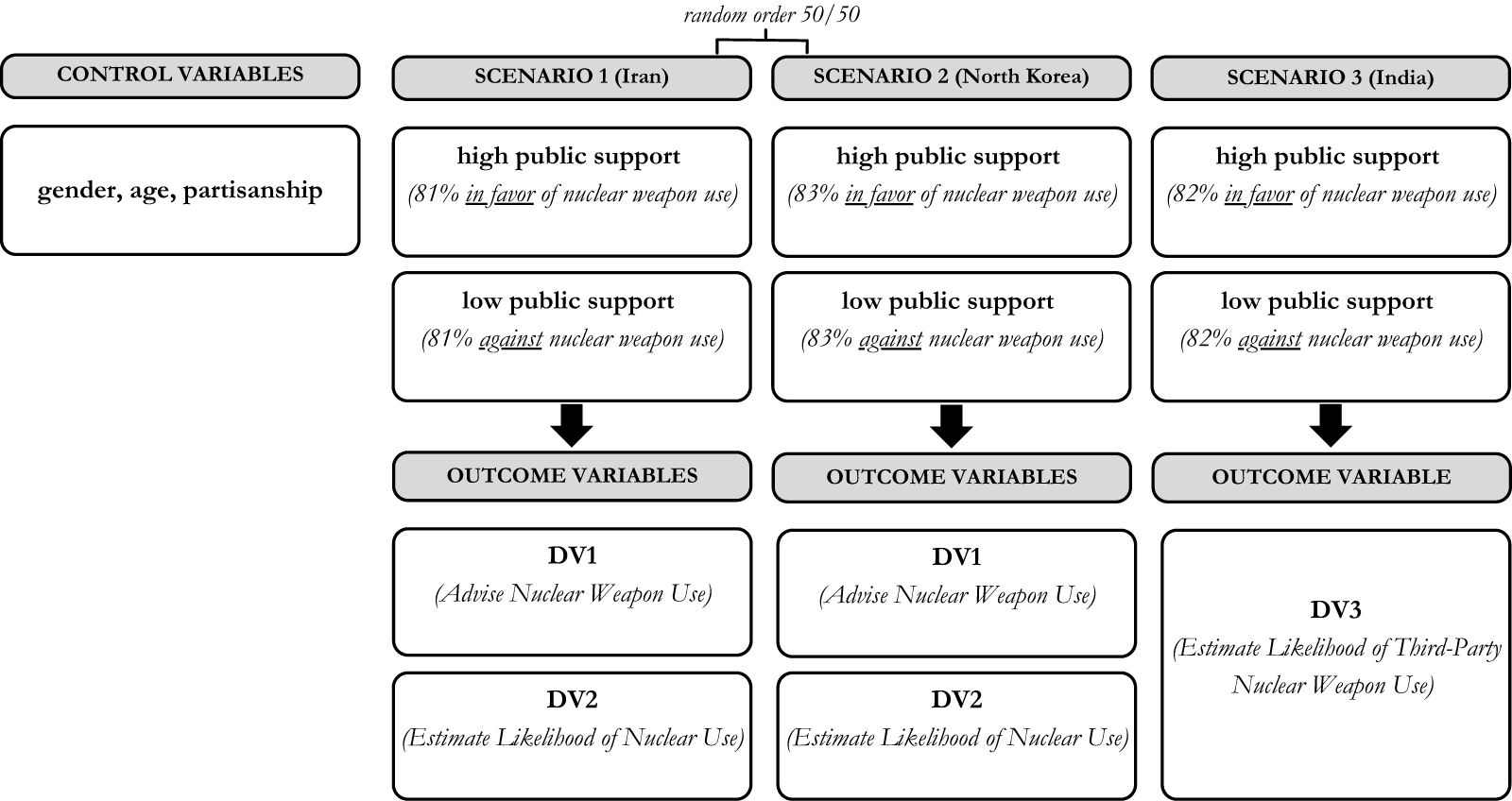

To test our theoretical expectations empirically, we designed and pre-registered an original survey experiment (see Figure 1). Participants were asked to imagine that they served as the US National Security Advisor (US sample) or the UK National Security Adviser (UK samples). Their task was to provide situational assessments and advice to the US president or the UK prime minister, respectively. In turn, we provided them with three different fictional scenarios wherein nuclear weapon use was considered as a form of military retaliation. In these scenarios, we varied domestic public attitudes regarding nuclear weapon use.Footnote 38

Figure 1. Experimental design.

Our scenarios represented realistic, most-likely cases for the use of nuclear weapons. They allowed us to test how our participants reacted to public views about the use of nuclear weapons in a first-use scenario against a non-nuclear adversary, a nuclear retaliation scenario, and a third-party nuclear threat scenario, respectively. Each scenario was presented to the participants as a classified memorandum sent by the Director of National Intelligence.Footnote 39

Scenario 1 corresponded to the logic of a majority of ‘nuclear taboo’ experiments. In these studies, a nuclear-armed country considers violating a nuclear non-use norm by using nuclear weapons first in response to a serious national security threat or a major non-nuclear attack.Footnote 40 Our own vignette described tensions in the Middle East after international negotiations to stop Iran’s support for terrorist organisations failed. Participants were informed that the intelligence community obtained credible information about Iran’s plans to conduct a major attack – possibly involving chemical weapons – on their country’s troops deployed in the region. In response, the US president/UK prime minister publicly threatened that any use of chemical weapons by Iran would ‘result in a devastating nuclear response’.Footnote 41 Defying this warning, Iran conducted large-scale missile strikes against US/UK military bases in the region, including the use of banned chemical nerve agents. Initial casualty estimates indicated that at least 4,700 of the country’s troops and 6,100 local civilians had died.

After respondents read this prompt, we asked them for their initial assessment and explained the choices facing their respective national leaders. We first asked participants how serious they believed the situation would be for their national security on a scale from 1 (not serious at all) to 10 (extremely serious).Footnote 42 Next, we informed them that the US president/UK prime minister was considering two retaliatory options prepared by senior military leaders. These options varied in terms of the chosen weapon system, which affected the expected collateral damage and the likelihood of successfully destroying Iran’s chemical weapons stockpile:

Operation Alpha would use a limited number of nuclear-armed missiles to target key military sites in Iran. There would be significant collateral damage and a high chance of successfully destroying Iran’s chemical weapons stockpile.

Operation Beta would use a large number of conventionally armed missiles to target key military sites in Iran. There would be some collateral damage and a moderate chance of successfully destroying Iran’s chemical weapons stockpile. Footnote 43

Furthermore, participants were provided with two additional considerations. First, the memorandum noted that members of the government were divided over whether a nuclear or conventional response was warranted. This conveyed that both options were considered feasible by military and political decision-makers. Second, we experimentally manipulated the results of a fictional public opinion poll. In a ‘high public support’ treatment, we stated that ‘public opinion polls conducted before Iran’s attack indicated that the public would strongly support a nuclear response to Iranian use of chemical weapons: 81 per cent of [American/British] citizens indicated that they would support or strongly support nuclear retaliation in the event of chemical weapons use’. In a ‘low public support’ treatment, we changed all instances of the word ‘support’ to ‘oppose’.Footnote 44

After participants read the vignette, we asked them how likely they were to advise the US president/UK prime minister to retaliate against Iran with nuclear weapons. We measured their responses on a 7-point Likert scale: 1 – Very likely to 7 – Very unlikely. These responses were used as a dependent variable (‘Advise Nuclear Weapon Use’; DV1) for testing H1.

We also asked participants how likely they thought it was that the US president/UK prime minister would prefer to retaliate against Iran with nuclear weapons. Responses were measured on the same ordinal scale. This item was used as a dependent variable (‘Estimate the Likelihood of Nuclear Weapon Use’; DV2) for testing H2.

Scenario 2 described a crisis in which another actor used nuclear weapons first, and the participant’s country considered nuclear retaliation. Such scenarios are occasionally used in nuclear non-use experiments conducted on population samples.Footnote 45 Even though the ‘nuclear taboo’ was coined with reference to the first use of nuclear weapons, Tannenwald suggests that it ‘may have spillover effects on even the retaliatory use of nuclear weapons’.Footnote 46

In the Scenario 2 vignette, we described the escalation of tensions in East Asia after international talks to eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons failed. Akin to the previous scenario, the intelligence community obtained credible information that North Korea was planning a major attack against US/UK forces deployed in the region, possibly including the use of nuclear weapons. In a televised speech, the US president/UK prime minister warned that the use of nuclear weapons would result in devastating nuclear retaliation. Pyongyang nevertheless launched two nuclear-armed missiles against a US/UK aircraft carrier strike group in South Korean waters and the South Korean port of Busan. Casualty estimates included the deaths of 4,100 US/UK troops, 4,000 South Korean troops, and 34,500 South Korean civilians, with hundreds of thousands wounded.

Retaliation choices followed a similar nuclear/conventional strike dilemma against key military sites. The objective here was to destroy North Korea’s nuclear weapons stockpile. We labelled the operations Gamma and Delta for variety. The treatment assignment once again differentiated between high (83 per cent in favour) and low (83 per cent against) public support for nuclear use. We used the same DV1 and DV2 to test H1 and H2 in a different strategic context.

Scenario 3 described a war between the nuclear-armed states of India and Pakistan. Pakistan dropped four tactical nuclear bombs on the barracks of Indian forces in Kashmir, despite the Indian prime minister’s warning of nuclear retaliation. We presented the assessment that India’s prime minister was considering different military response options. Once again, we varied support for nuclear use in a public opinion poll among Indian citizens (82 per cent in favour or 82 per cent against).

We then asked participants how likely they thought it was that the Indian prime minister would prefer to retaliate against Pakistan with nuclear weapons on a 7-point Likert scale. This item was used as a dependent variable (‘Estimate the Likelihood of Third-Party Nuclear Weapon Use’; DV3) for testing H3.

After reading the three scenarios and responding to all outcome measures, we included a simple attention check.Footnote 47 Finally, we provided a debrief section to offset potential real-world conditioning.Footnote 48 We pre-registered the experiment with [anonymised] and obtained ethics permissions from [anonymised].Footnote 49

We fielded our experiment to three audiences comprised of the types of respondents that engage in policy advising and/or decision-making on policy. These samples included sitting members of the UK parliament surveyed via Survation’s parliamentary omnibus poll and US and UK government employees in official policy rolesFootnote 50 recruited through the Prolific online platform. Compared to commonly used samples of university students or the general public, these respondents possess direct, practical experience with real-world policy processes. As such, they are more likely to employ the types of decision-making heuristics relevant in high-stakes political and bureaucratic environments, which is particularly valuable for our ‘perspective-taking’ experiment.Footnote 51 Given the practical challenges of directly sampling sitting members of the executive branch and high-level policy advisers, our approach provides a balanced trade-off between sufficient ‘elite-ness’ of respondents and sample sizes that allow for meaningful statistical analyses.

In the sample of UK parliamentarians, we received responses from 103 participants during November and December 2024. Between October 2024 and January 2025, we also collected 420 responses from the US government employee sample and 406 responses from the UK government employee sample. In Appendix 5, we provide a breakdown of the socio-demographic composition of these three samples.

Results

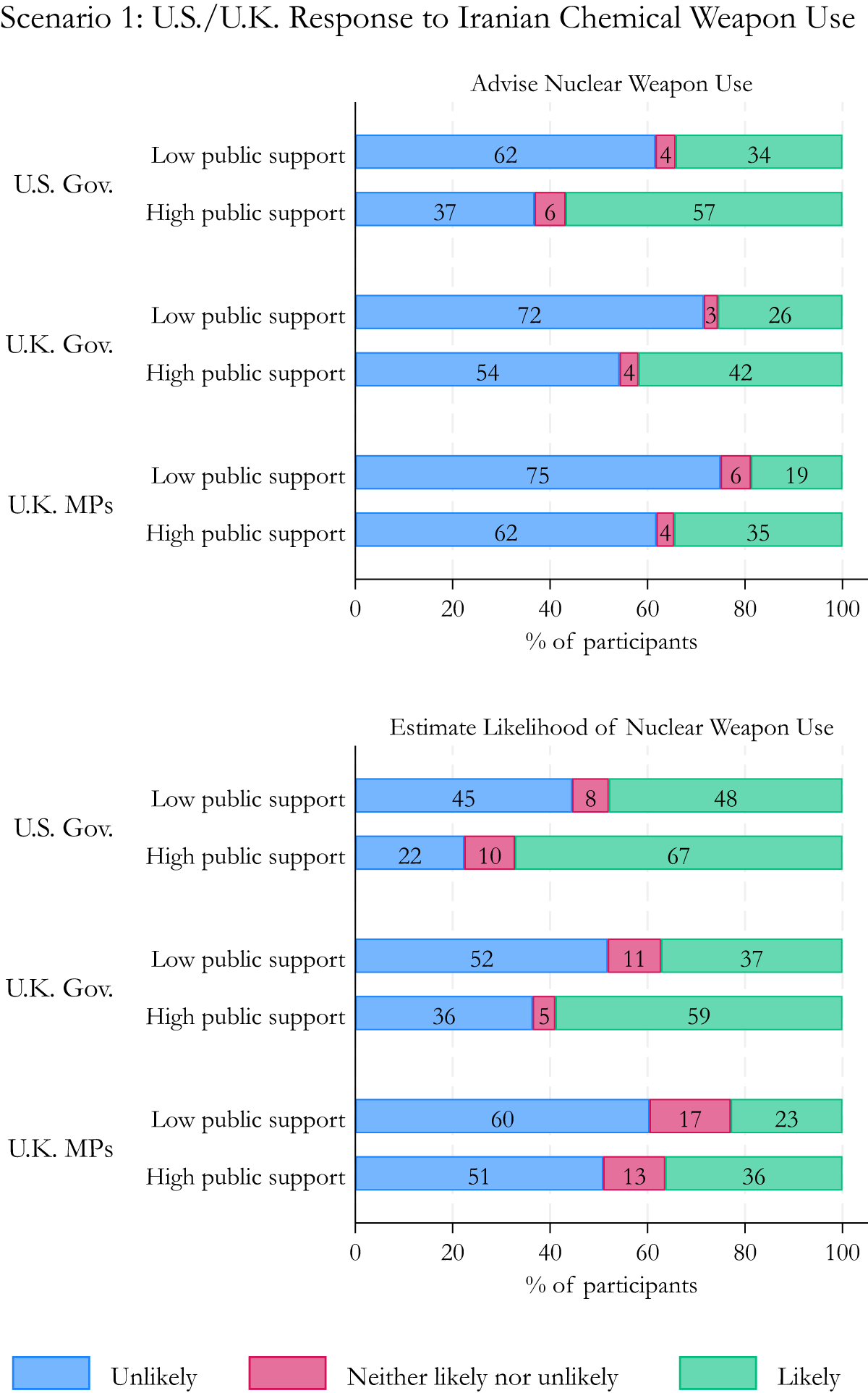

In this section, we present results separately for our three scenarios. To facilitate the interpretation of substantive effects, we first present the results as categorical plots, with responses from a 7-point ordinal scale grouped into three categories: Unlikely, Neither likely nor unlikely, and Likely. Subsequently, we show the results of ordinal regression analyses conducted to test the hypotheses, per our pre-registration plan.

Figure 2 displays results for Scenario 1 (Iran). Across all three samples, we observe a consistent pattern of increased elite support for nuclear weapon use in the high public support condition compared to the low public support condition (‘Advise Nuclear Weapon Use’; DV1). The magnitude of the results ranges from a 16 percentage-point increase in the two UK samples to a 23 percentage-point increase in the US sample. In the US government employee sample, the likelihood of advising nuclear use against Iran increased considerably from 34 per cent to 57 per cent. In the UK government employee sample, the increase was from 26 per cent to 42 per cent. Among UK parliamentarians, we observed an increase from 19 per cent to 35 per cent.

Figure 2. Survey responses to the Iran scenario.

While the difference between conditions holds systematically across samples, we generally observed lower support for a nuclear strike option in the UK samples compared to the US sample. This could reflect a variety of different concerns that might make British respondents more circumspect about supporting nuclear weapon use. These factors might include a stronger nuclear taboo in the United Kingdom, concerns about the limitations of the smaller UK nuclear arsenal, or lower salience among British participants regarding Middle East security issues. The US relationship with Iran has also long been more hostile than the British relationship with Iran. Our finding aligns with the work of Janina Dill, Scott Sagan, and Benjamin Valentino, who found lower support for nuclear use among the UK public when compared to the US, French, and Israeli publics.Footnote 52

A similar pattern holds for the second dependent variable (‘Estimate the Likelihood of Nuclear Weapon Use’; DV2). As we show in the second panel of Figure 2, in all three elite samples, a larger proportion of participants believed that nuclear strikes against Iran were more likely to be ordered by their country’s leader when public support for nuclear use was high (from 13 to 22 percentage-point increases). In the US government employee sample, the estimated likelihood increased from 48 per cent to 67 per cent. In the UK government employee sample, it grew from 37 per cent to 59 per cent. In the UK parliamentarian sample, it rose from 23 per cent to 36 per cent.

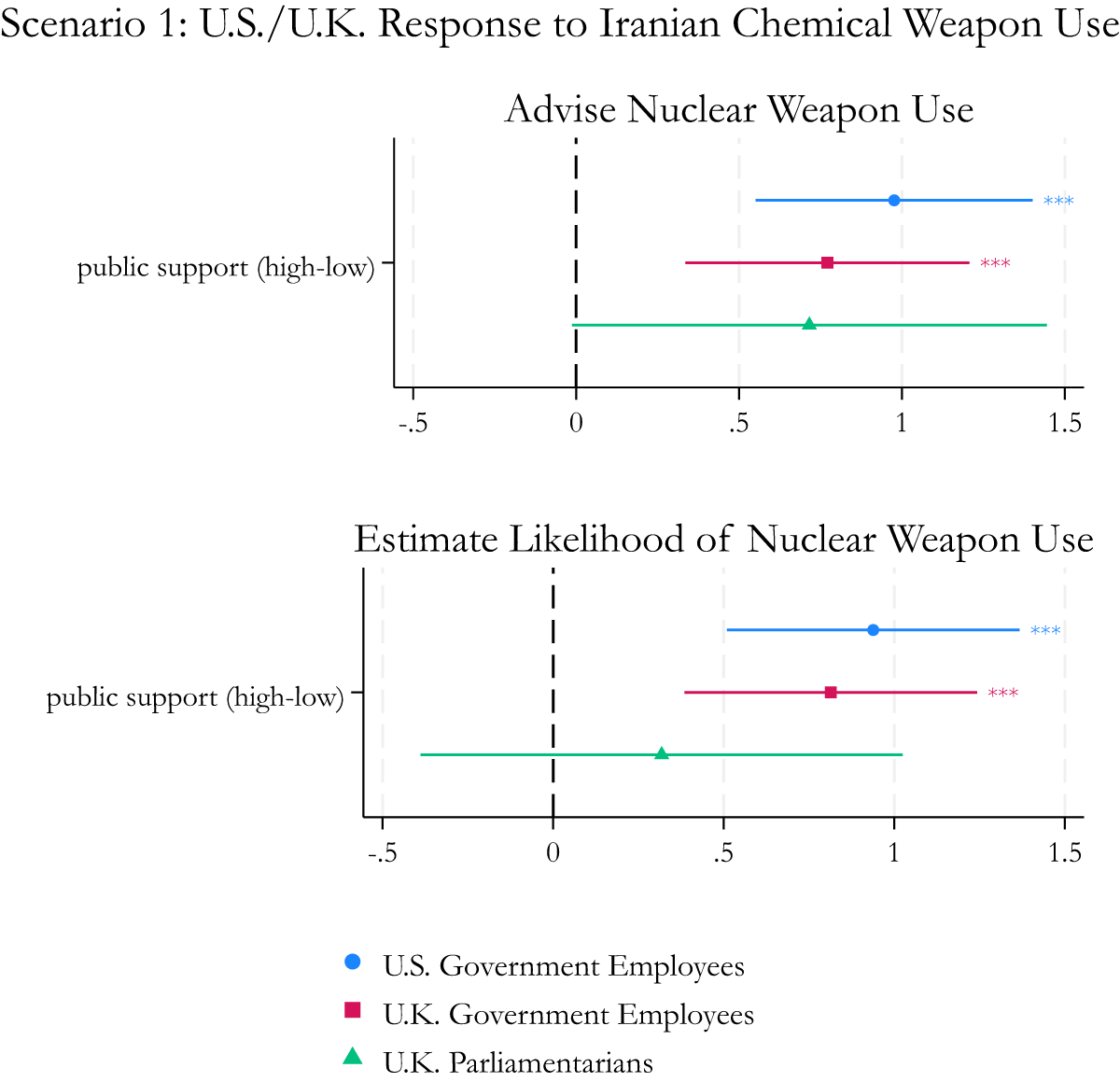

To test hypothesis H1 in this scenario, we conducted an ordinal logistic regression analysis. We used the public cue (high/low public support) as a predictor; gender, partisanship, and age as covariates; and DV1 (likelihood of advising nuclear use) as an outcome measure. In the first panel in Figure 3, we show that for both US and UK government employees, the effects were statistically significant (p < .001). For UK parliamentarians, the test fell just short of the conventional measure of statistical significance (p = .054). However, considering the same direction and a comparable effect size to the UK government employees sample, this was most likely a function of a significantly smaller sample size preventing us from calculating a more precise estimate.Footnote 53 As such, the first-use Iran scenario provides strong empirical evidence in favour of H1 that political elites are more supportive of the use of nuclear weapons when public support for nuclear use is high than when it is low.

Figure 3. H1 and H2 tests in the Iran scenario.

To test H2, we conducted a corresponding analysis with the estimated likelihood of nuclear weapon use (DV2) against Iran as an outcome measure. In the second panel in Figure 3, we show that for the government employee samples, effects were once again statistically significant (p < .001). In the UK parliamentarian sample, the difference between experimental groups did not pass the test of statistical significance (p = .377). This is likely both a function of a small n preventing a precise estimation of the effect in the population and a genuinely smaller effect of public cues on parliamentarians’ beliefs about the likelihood of nuclear use compared to our other samples. Indeed, parliamentarians may feel greater confidence in the consistency of government decision-making based on strategic doctrine, rather than in passing political trends like public opinion. Overall, however, our analysis of Scenario 1 provides some empirical evidence in favour of H2 that political elites believe that their country’s leaders are more likely to favour the use of nuclear weapons when public support for nuclear use is high than when it is low.

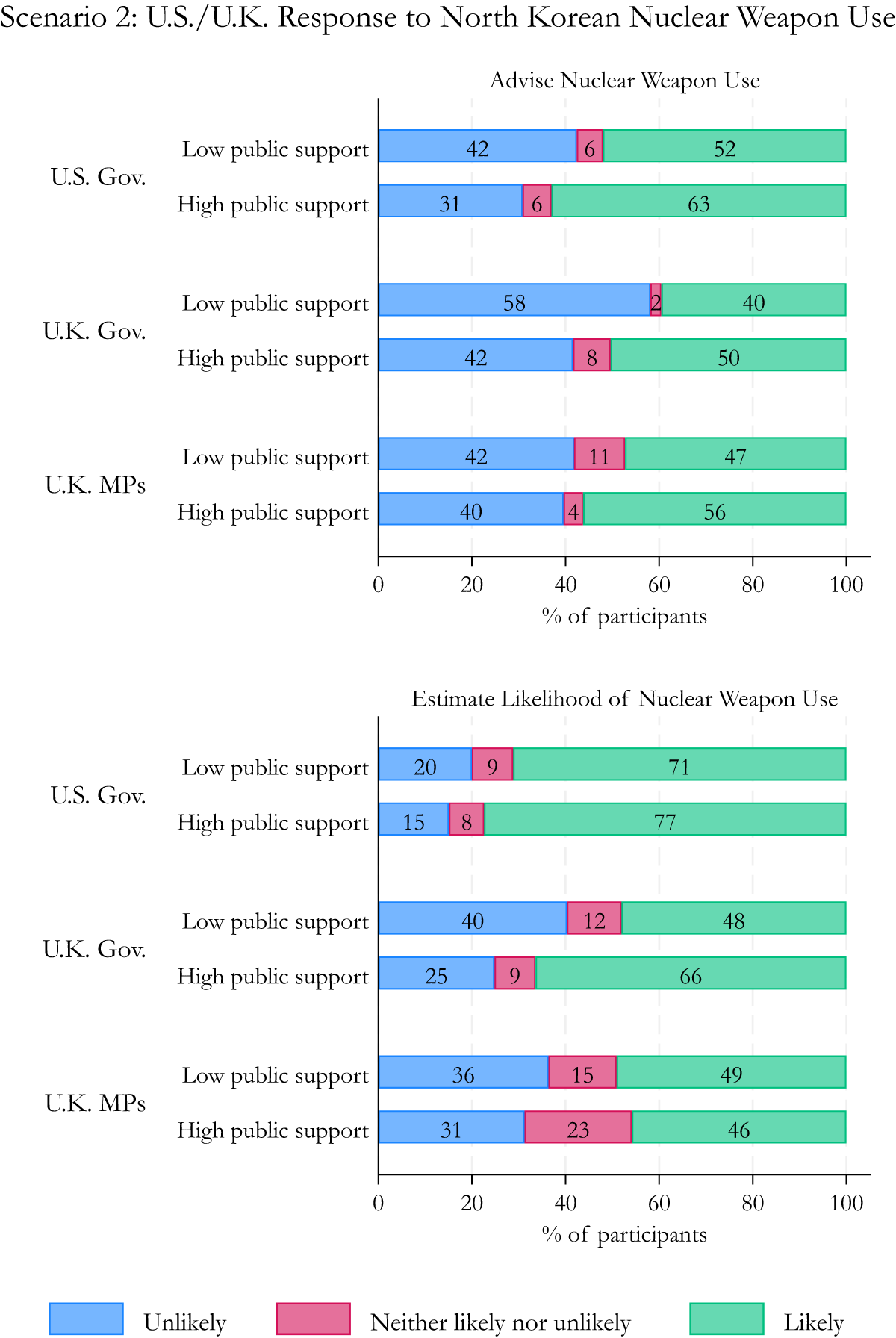

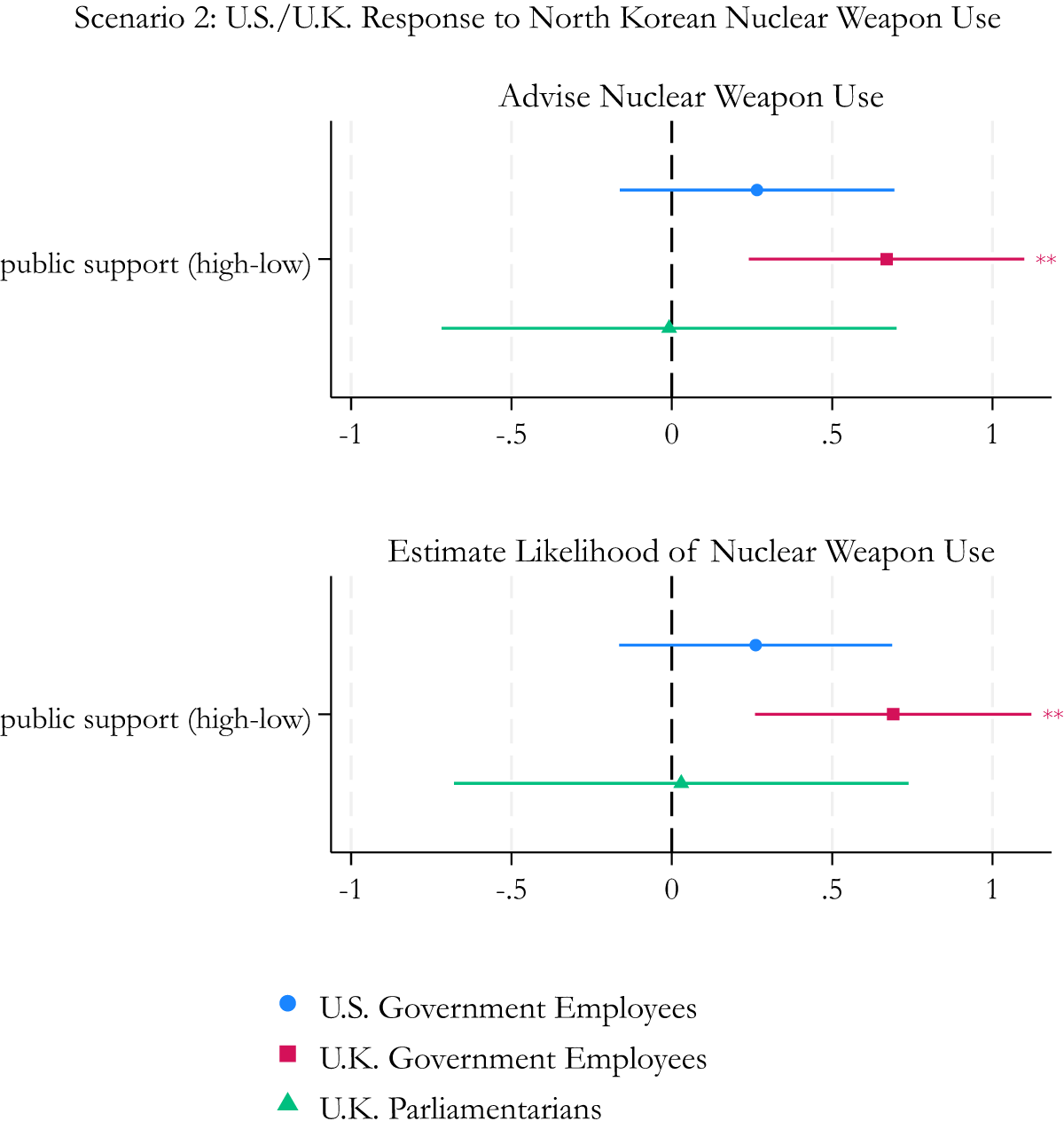

We conducted corresponding analyses for the North Korea nuclear retaliation scenario. Once again, we observe a clear pattern in responses to DV1. A larger proportion of participants indicated that they would advise nuclear weapon use when public support is high than when it is low (see Figure 4, first panel). However, the difference here is substantially smaller than for the Iran scenario, with a 9 to 11 percentage-point increase. For DV2, the difference in the perceived likelihood of nuclear use under conditions of high public support is present but small: only 6 percentage points in the US government employee sample and 8 in the UK government employee sample. In the UK parliamentarian sample, participants were slightly less likely to think using nuclear weapons was ‘likely’ under conditions of high public support, although they were also slightly less likely to think nuclear weapon use was ‘unlikely’. Stated differently, a greater percentage of UK parliamentarians believed nuclear use was neither likely nor unlikely when public support was high than when it was low.

Figure 4. Survey responses to the North Korea scenario.

There is, notably, a more muted effect of public opinion when considering nuclear retaliation in response to a North Korean nuclear strike than when considering nuclear first use against Iran. Public opinion may be less relevant once the nuclear taboo has been shattered, especially given the higher measures for elite support of the nuclear option in Scenario 2 versus Scenario 1. The strategic demands associated with nuclear retaliation in this scenario could outweigh domestic political concerns to a greater degree than is the case for nuclear first use against a non-nuclear adversary.

In Figure 5, we show the result of ordinal regression analyses testing H1 and H2 in the North Korea scenario. Only in the sample of U. government employees did the difference in responses to DV1 and DV2 between experimental conditions pass the threshold of statistical significance (p = .002). The direction of the effect for US government employees is consistently positive, but these results are not statistically significant. As such, in this scenario, wherein the United States or the United Kingdom is faced with having to respond to a North Korean nuclear strike, we found only very limited empirical evidence supporting H1 and H2. This suggests that there are fundamental political, strategic, and/or normative distinctions between nuclear first use directed at an adversary without nuclear arms and retaliation in kind against a nuclear-armed adversary. Such considerations may mitigate the role of public opinion after the nuclear taboo is broken.

Figure 5. H1 and H2 tests in the North Korea scenario.

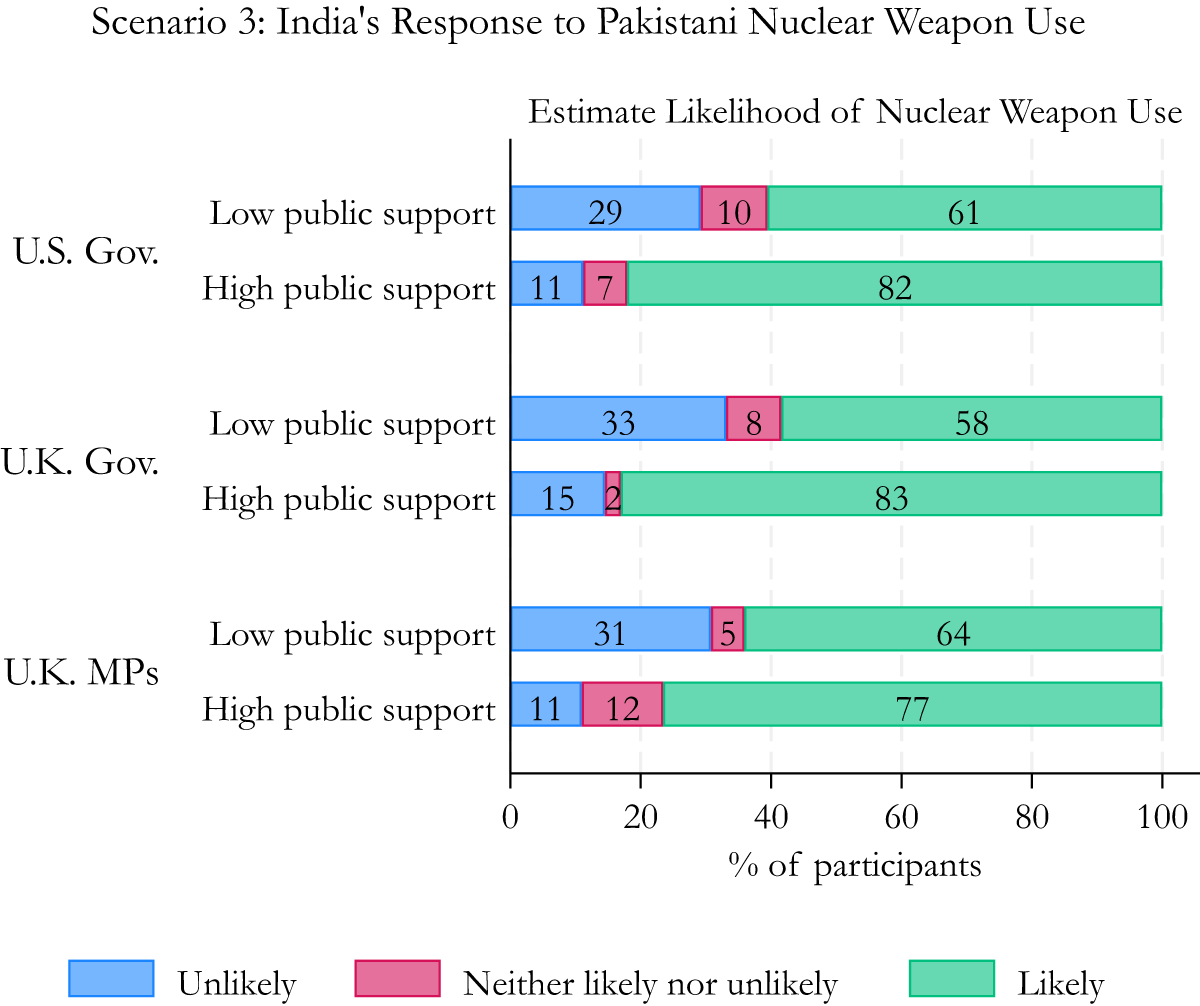

Next, we examined the third scenario depicting an India–Pakistan conflict. As Figure 6 shows, participants in all three elite samples saw India’s nuclear threats as more credible in the high public support condition relative to the low public support condition. In the US government employee sample, there was a 21 percentage-point increase from 61 per cent to 82 per cent. In the UK government employee sample, the difference was 25 percentage points: 58 per cent to 83 per cent. In the UK parliamentarian sample, there was a 13 percentage-point increase from 64 per cent to 77 per cent.

Figure 6. Survey responses to the India scenario.

It is telling that many respondents had heterogeneous perceptions of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ in terms of elite susceptibility to public opinion. Whereas many participants did not believe that their own government’s nuclear retaliation decisions would be shaped by public opinion, they nonetheless thought public opinion would influence the decision-making process in other states (e.g., India). Public opinion may, therefore, be a significant factor underlying the credibility of nuclear threats. It could affect the ability of states with varied types of democratic institutions and degrees of power consolidation to practice effective nuclear deterrence. It may, however, be the case that non-democratic governments are seen as unresponsive to public preferences – a subject worthy of further scholarly investigation.

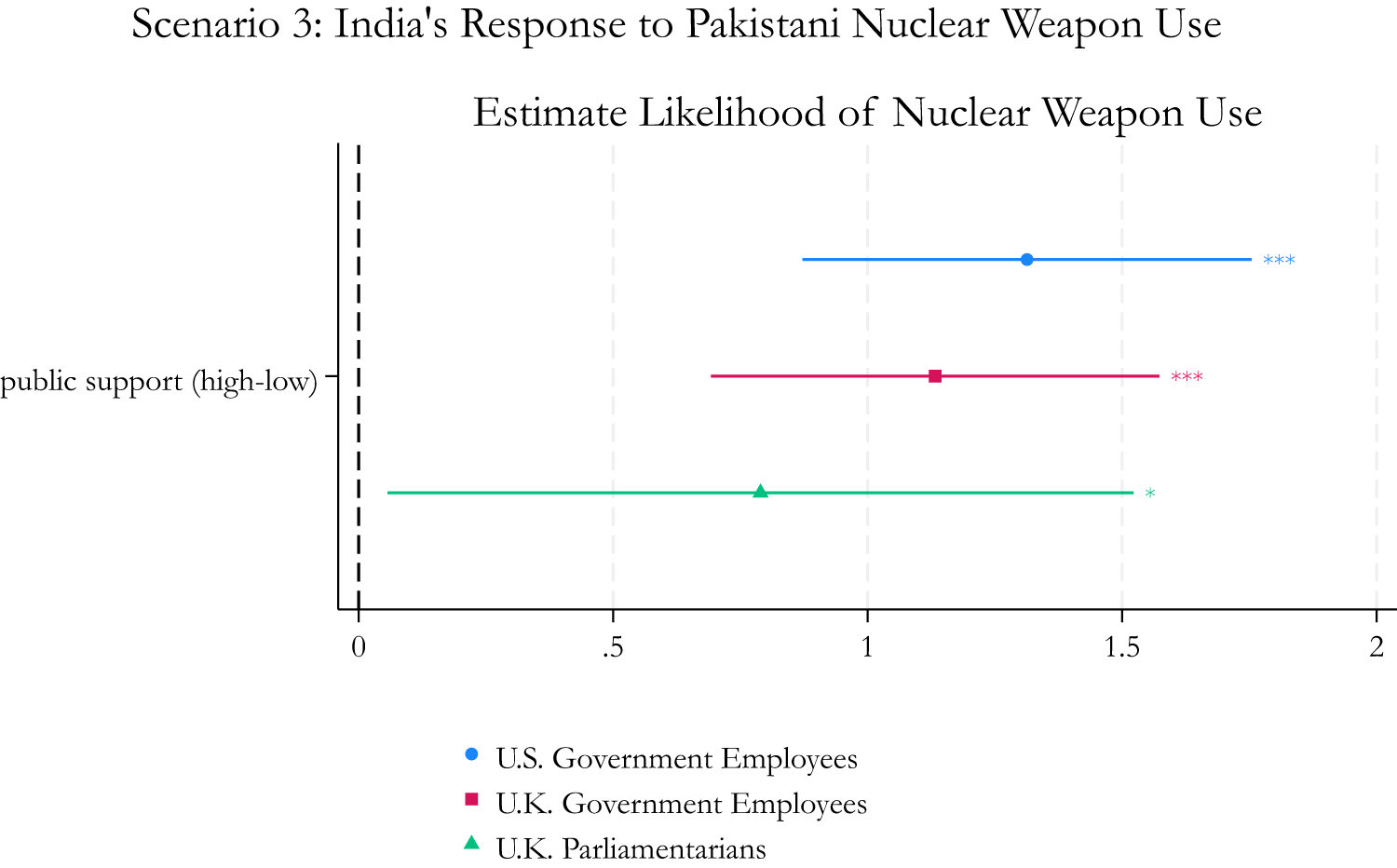

In Figure 7, we show the results of an ordinal regression test with responses to DV3 (‘Estimate the Likelihood of Third-Party Nuclear Weapon Use’) as an outcome measure. In all three samples, our results are statistically significant (p < .001 in the government employee samples and p = .035 in the parliamentarian sample). As such, we find strong evidence favouring H3 that political elites are more likely to find third-party nuclear threats credible when public support for using nuclear weapons is high than when it is low.

Figure 7. H3 test in the India scenario.

After formally testing our three main pre-registered hypotheses, we conducted a set of additional exploratory analyses to gain further insight into the collected data. First, as mentioned in the ‘Experimental Design’ section of this paper, one-third of respondents in the government employee samples were also assigned to a control condition in which we provided no information about public views on nuclear weapon use. In line with our theoretical expectations, the responses in this ‘no cue’ condition generally fell between those observed in the high- and low-support conditions. We provide a detailed analysis of this treatment group in Appendix 8.

Next, we examined whether the order in which we displayed scenarios 1 (Iran) and 2 (North Korea) affected our participants’ responses. The results provided in Appendix 9 show that the effect of scenario order was not statistically significant across samples and dependent variables. In other words, seeing the North Korea second-strike scenario first did not meaningfully alter participants’ subsequent judgements about nuclear first use in the Iran scenario.

Finally, we tested the effects of gender and age. The results presented in Appendix 10 show neither a consistent association between these socio-demographic factors and relevant outcome measures nor a statistically significant interaction with the experimental treatments.

Discussion

This section discusses our key findings and their implications for the study of nuclear politics. We find strong evidence suggesting that high public support significantly increases elites’ backing for nuclear first use when the adversary cannot retaliate in kind. Likewise, such hawkish public support makes elites more convinced that top political and military leaders will opt for the nuclear option. These headline findings indicate that public opinion studies of the nuclear taboo should not be written off as irrelevant to the formulation of nuclear policy.

Our findings are also squarely in line with other recent elite-focused experimental studies on attentiveness to public preferences in the military domain. For example, Michael Tomz, Jessica Weeks, and Keren Yarhi-Milo found a 16 percentage-point difference between Israeli Knesset members’ support for military strikes against Lebanon under conditions of high versus low public support.Footnote 54 Jonathan Chu and Stefano Recchia observe a 19 percentage-point increase in UK parliamentarians’ support for military patrols in the South China Sea when informed of public support.Footnote 55 And Erik Lin-Greenberg identifies a 15 percentage-point increase in US military officers’ support for operations in Somalia when the public supports, rather than opposes, the mission.Footnote 56 The similar effect sizes across these studies – and our own congruent findings – provide some insights into the degree to which political and military elites might be swayed by public preferences for the use of military force. In providing the first clear evidence of this phenomenon specifically in the nuclear domain, we show that decisions about using the world’s most powerful weapons do not appear to be ‘firewalled’ from public preferences.

To that end, our finding regarding the effect of public opinion on elite preferences towards nuclear first use reveals two critical pathways for public opinion to affect policy outcomes. First, political elites may be proactively attentive to public preferences, aligning their decision-making with public attitudes to reap political benefits such as re-election, political party backing, and donor support. Of course, this is observationally equivalent to a genuine responsiveness to the demands of representative democracy. Second, political elites who are unwilling to change their own views in response to public preferences appear to believe that other political actors will do so. This belief could cause key actors to take action to promote their views, by either strategically leveraging public opinion or building coalitions to oppose these attitudes. That public opinion could shape political decisions about the potentially world-altering decision to use nuclear weapons gives weight to the recent wave of studies dedicated to examining public views on nuclear issues.

These mechanisms function independently of whether public preferences can reliably provide insight into the psychological ‘microfoundations’ of elites’ nuclear attitudes. While elites and the public may think differently about various nuclear issues or have different baseline views on the use of nuclear weapons,Footnote 57 the study of public preferences is nonetheless significant in its own right. Our work shows that public opinion can sway elites’ perceptions and perhaps even shape outcomes in nuclear politics.

However, these effects may be far more pronounced in cases of nuclear first use against adversaries that lack their own nuclear arsenals. We find far more limited evidence regarding the effect of public opinion in cases where nuclear weapons use is considered in retaliation to an adversary’s nuclear strike. When public support for nuclear use is high, we find a significant increase in UK government employees’ willingness to advise using the bomb against North Korea. Similarly, we see a significant increase in these respondents’ perceptions of the likelihood of nuclear use by the UK prime minister in response to North Korea’s aggression. For the US government employee sample, the direction of these effects remains positive, but the results are not statistically significant. We find no evidence that UK parliamentarians are attentive to public opinion in considering nuclear retaliation in response to a North Korean nuclear strike, although our ability to detect a small effect is limited by a limited sample size – a common constraint in elite surveys.

Limited evidence supporting H1 and H2 in the North Korea scenario suggests that public opinion may not be as meaningful an enabling or constraining factor in cases of nuclear retaliation as in certain cases of nuclear first use. There are many potential explanations for this finding. It is possible that our participants anticipate different domestic political dynamics after the nuclear taboo is broken. They could expect unique normative pressures in retaliation scenarios, such as demands for retribution in kind in response to an adversary’s use of nuclear weapons. Participants could also identify different strategic imperatives in the North Korea scenario compared to the Iran scenario, given that Pyongyang possesses a functional nuclear arsenal. This could include a need to quickly eliminate North Korea’s remaining nuclear stockpile or carefully manage the potential for further nuclear escalation. These and other factors might act as countervailing pressures to the concerns of domestic politics.

Our third key finding is that public opinion may underpin the credibility of nuclear threats. Even if there are cases when public opinion does not directly influence individual elites’ politics, our results show that third-party observers take domestic politics into account when evaluating the credibility of others’ threats to use nuclear weapons. This offers another pathway through which public opinion can shape nuclear outcomes. On the one hand, publics deeply opposed to nuclear weapon use could undermine the ability of their governments to practice nuclear deterrence and reassure security partners. On the other hand, publics that strongly support the use of nuclear weapons could enhance their government’s deterrent threats. This latter situation could, however, come at the cost of undermining adversary assuranceFootnote 58 or raising concerns among allies and partners about entrapment.Footnote 59 Importantly, this pathway is a matter of perception that exists regardless of whether or not public opinion affects specific nuclear use decisions. Although some elites may not be attentive to their own publics’ nuclear preferences, third-party observers – be those allies, partners, neutral states, or adversaries – may nevertheless believe that public opinion matters. And they may formulate policy responses that take such perceptions into consideration.

While we suggest that this finding is of critical importance for our understanding of nuclear crisis bargaining, we must also acknowledge an important caveat. The fictional scenario in our experiment depicted decision-making dynamics in India, the world’s largest democracy. It is conceivable that elites assessing the credibility of a nuclear threat in a non-democratic nuclear-armed state (e.g., China, Russia, or North Korea) would give much less weight to public views on the issue (if such data were available at all). While we assume that the logic that applied to India would generalise to other democratic nuclear-armed states, we cannot a priori make such an assumption for states with non-democratic regimes.

However, we should also note trends in recent scholarly literature on autocratic accountability. There is increasing empirical evidence that even non-democratic regimes care deeply about fluctuating domestic public opinionFootnote 60 and are more responsive to public preferences than previously assumed.Footnote 61 Furthermore, studies investigating the domestic audience costs in authoritarian contexts have found that, even in non-democratic states like Russia and China, the public disapproves of leaders who make threats to use military force and then back down.Footnote 62 This experimental evidence from nuclear-armed, non-democratic countries, therefore, aligns with the hand-tying logic that we operationalised in our experiment through leaders’ public signalling of nuclear threats. Future experimental research should investigate whether elite decision-makers in democratic countries consider public opinion in authoritarian regimes as a relevant factor in their leaders’ decision-making. This would help scholars determine whether elites believe that public support for nuclear weapon use in autocracies enhances the credibility of nuclear threats in a manner comparable to that of democratic nuclear powers.

Conclusion

Our survey experimental study presents convincing evidence that political elites may well take public opinion seriously when considering decisions about the potential use of nuclear weapons. It offers first-of-its-kind backing for the utility of conducting general population surveys about an issue that has long been considered the exclusive domain of elites. In the preceding discussion section, we identified three specific pathways through which public opinion can shape elite decision-making on nuclear use. These mechanisms include: 1) directly influencing elite preferences through bottom-up public cues; 2) updating elite beliefs that other political actors will be affected by public attitudes; and 3) increasing or decreasing the credibility of a state’s deterrent threats in the eyes of third-party elite observers. That said, as we noted, the first and second mechanisms appear to be attenuated in scenarios wherein decision-makers are deciding on whether to use nuclear weapons to retaliate against an adversary’s first use of the bomb. The third mechanism, however, remains relevant in situations involving the second use of nuclear weapons.

These results suggest at least two important future directions for the study of nuclear politics. First, scholars would do well to expand the scope of this inquiry to states beyond the United States and the United Kingdom to evaluate its generalisability. Existing literature suggests that the views of the French and Israeli publics may differ in potentially meaningful ways.Footnote 63 Likewise, it would be useful to examine the applicability of our theoretical findings in other nuclear-armed states – including non-democratic countries – and among states that are protected by a patron’s nuclear umbrella. Would elites in this latter group of countries seek an ally to defend them with nuclear weapons? How might public preferences shape such decisions? Second, scholars could conduct detailed, open-ended interviews with elite decision-makers to gain a deeper understanding of how they perceive and interpret public opinion on nuclear weapons. What precise causal factors, among individual elites, might explain the differing results that we observed across our three scenarios (Iran, North Korea, and India)? In these respects, our work may open the door to scholarly inquiries that help to shed new light on the intersection of domestic politics and international nuclear politics.

Our findings are also policy-relevant, as they provide valuable insights for understanding the bargaining and deterrence relationships between nuclear-armed states. The results of our study suggest that states should be both aware of – and proactive about – their public’s nuclear preferences. To some extent, this already reflects political realities. An ongoing campaign by NATO to ‘raise the nuclear IQ’ reflects this logic. Its intent is to create a more informed transatlantic public that does not panic in the face of nuclear threats from adversaries, but whose support could enhance the credibility of NATO’s nuclear deterrence.

Since the onset of Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, there has also been growing attention to the Kremlin’s nuclear strategy.Footnote 64 For its part, Russia appears to be similarly interested in its public’s nuclear resilience. Many of Moscow’s nuclear threats towards Ukraine and Europe over the last few years have appeared to be targeted at domestic audiences (e.g., appearing only in local, Russian-language media). This may reflect an intent to build public support for nuclear weapon use to shore up Russia’s nuclear credibility and/or enable nuclear decision-making by the regime at lower domestic political costs.Footnote 65 Our work suggests that such efforts by states and military alliances – should they successfully inform public opinion on nuclear issues – could yield significant benefits.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2025.10031.

Acknowledgements

The findings of this research were presented at workshops and seminars at Harvard University, Boston University, the University of Southern Maine, Peace Research Center Prague, and the Vienna School of International Studies. We thank all the participants for their constructive and useful feedback.

Funding statement

Michal Smetana gratefully acknowledges funding from Charles University’s PRIMUS programme, grant PRIMUS/22/HUM/005. Lauren Sukin and Marek Vranka acknowledge funding from Charles University’s Center of Excellence (UNCE) programme, grant 24/SSH/018 (‘Peace Research Center Prague II’), and Cooperatio (MCOM). Lauren Sukin acknowledges funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, grant G-PS-24-61252.

Michal Smetana is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University, and Director of the Peace Research Center Prague (PRCP); email: smetana@fsv.cuni.cz.

Lauren Sukin is John G. Winant Associate Professor in US Foreign Policy in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford, Professorial Fellow at Nuffield College at the University of Oxford, and a researcher at the Peace Research Center Prague (PRCP) at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University; email: Lauren.sukin@politics.ox.ac.uk.

Stephen Herzog is Professor of the Practice at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey and an Associate of the Project on Managing the Atom (MTA) at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs; email: sherzog@middlebury.edu.

Marek Vranka is Lecturer at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University, researcher at the Peace Research Center Prague (PRCP), and Head of the Prague Experimental Laboratory for Social Sciences; email: marek.vranka@fsv.cuni.cz.