INTRODUCTION

The island of Samos is known for its archaeology and rich island heritage. The island is particularly famous for the Heraion, or the Sanctuary of Hera, which in 1992 was inscribed along with the remains of the ancient city of Pythagoreio on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Even after a century of research (the Heraion was first excavated in 1925), new investigations on Samos continue to yield important new insights (Henke Reference Henke2021; Menelaou and Kouka Reference Menelaou and Kouka2021; Walter, Clemente and Niemeier Reference Walter, Clemente and Niemeier2021). Most of this archaeological research, however, has been focused on the eastern half of the island, the location of the main urban centre (Pythagoreio and its surroundings) as well as the island’s main sanctuary (the Heraion).

Comparatively less attention has been paid to the archaeology of western Samos. This area is rich in fertile agricultural land, and is also located on a major maritime route from the northern to the southern Aegean (Campbell and Koutsouflakis Reference Campbell, Koutsouflakis, Demesticha and Blue2021). Graham Shipley conducted an extensive pedestrian survey in the area in the 1980s, documenting the presence of archaeological remains and identifying several locations for potential future investigation (Shipley Reference Shipley1987). Yet in the intervening decades, archaeological exploration of this region has been limited, and much still remains to be investigated about the nature of settlement and connectivity in this area. The West Area of Samos Archaeological Project (WASAP) was conceived with a primary research question on the identification of areas of ancient activity, through a combination of exploratory and systematic investigations of the landscape. The other major research question of the project was focused on the (economic) connectivity of west Samos, both ‘internally’ with respect to its connections to the eastern half of the island and regarding possible export and import networks to the wider east Aegean region.

This article forms the first element of the tripartite publication of the WASAP survey. In this article, we present the results of the survey from south-western Samos, on the plain of Marathokampos between Koumeiika in the east and Limnionas in the west. Material was collected from south-western Samos during the 2021 and 2022 field seasons (during which we worked exclusively in the south-western area), as well as during the 2024 season (during which we worked both in the south-western and north-western areas). A second article on results from north-western Samos is currently in preparation. The third primary publication stemming from WASAP is an online data release on the open access platform Zenodo, making available in open and accessible format all field data, field photographs, geospatial data, and drone photography from all project seasons between 2021 and 2024.Footnote 1 In addition to these three core publications of WASAP, further articles offering further interpretations, analysis, or considerations of particular aspects of the work are planned (see ‘Discussion and Conclusions’, below).

In this article, we will introduce the project; summarise previous archaeological research in the area; set out our methodology; offer an overview of the main results of fieldwork according to geographical area; describe the key ceramic developments identified in the material; summarise statistical patterns; and outline plans for future public engagement work.

THE WEST AREA OF SAMOS ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT

The West Area of Samos Archaeological Project (WASAP) conducted four seasons of fieldwork between 2021 and 2024 (Fig. 1), with the kind permission of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, as well as the Ephorate of Antiquities of Samos and Ikaria (permit number: Ψ5ΛΩ4653Π4-AA1). WASAP was directed by Anastasia Christophilopoulou, Michael Loy, Naoíse Mac Sweeney and Jana Mokrišová (2021–2 only). The lead ceramicist for the project was Sabine Huy. The Field Director for 2022–4 was Michael Loy. The Byzantine specialist was Georgia Delli, and the Geographical Information Systems (GIS) analysis and data management were handled by Alexandra Katevaini (2021 and 2023), Anastasia Vasileiou (2022–4) and Michael Loy (2021–4). Team Leaders for fieldwalking teams were Katerina Argyraki, Matthew Evans, and Enrico Regazzoni; and senior team members were Fabiola Heynen, Eleni Kopanaki and Tracy Rabaiotti.Footnote 2

Fig. 1. Map of Samos and the Aegean, showing the area investigated by WASAP (map by Michael Loy).

SOUTH-WESTERN SAMOS

Samos is a large eastern Aegean island separated from the Anatolian (Turkish) coast by the Straits of Mykale. It is dominated by two high mountains, Mt Karvounis in the centre and Mt Kerkis in the west, both formed by marble and schists. Much of the island’s agricultural land lies in eastern Samos and is concentrated on the low lying plain of Chora, which is enclosed by mountainous terrain. The prominent Sanctuary of Hera is located on the plain’s south-western edge, while the town of Pythagoreio marks its easternmost limit. WASAP’s activities, however, focused on the western part of the island, which has a more rugged terrain.

West Samos lies between two high mountains: Kerkis and Karvounis (the latter also locally called ‘Ampelos’). Two basins lie between their slopes – a coastal plain around the city of Karlovasi in the north called Xirokampos, and the coastal plain of Velanidia south of Marathokampos in the south. Both are formed of Neogene marl soils and provide arable land. Additional opportunities for agriculture were afforded by the gentler lower slopes of the mountains (Shipley Reference Shipley1987, 8). This is particularly the case of south-western Samos, where the area between the southern coast and its central town, Marathokampos, rises steadily up to meet the foothills of Kerkis and Karvounis on either side (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Map of south-west Samos, showing places mentioned in the text, as well as the location of the five surveyed zones (map by Michael Loy).

Samos was known for the export of its rich natural resources in the first millennium BCE (e.g. Strabo 14.1.15; Touratsoglou and Tsakos Reference Touratsoglou, Tsakos, Papageorgiadou and Giannikouri2008; Bresson Reference Bresson2016, 376–8), and it is difficult to imagine that the south-western territories did not contribute to the island’s agricultural economic output of, for example, timber, marble, olive oil and wine (Herodotus 3.6; Paus. 7.4.1). Indeed, historically, it seems that areas in west Samos were used for the cultivation of vines, olives, legumes (supplemented with some wheat, barley, and oats), fruit trees such as pomegranates and figs, and also animal husbandry and pastoralism (sheep, goats, and horses). Bee-keeping has also been documented,Footnote 3 as well as the quarrying of stone, including marble.Footnote 4

Chronologically later information on the economic production in south-west Samos can be distilled from reports of Early Modern travellers to the region. They specify that the slopes of the Kerkis were terraced to make them viable for agriculture in the Early Modern era (Tournefort Reference Tournefort1717, 307; J. Murray Reference Murray1872, 362), olives were grown in the south-west (Stavrinidis Reference Stavrinidis1889, 24) and cattle were reared here as well (Tozer Reference Tozer1890, 160). Marathokampos was in fact named after fennel, which was cultivated there (Guérin Reference Guérin1856, 269).

Maritime connectivity was important for Samos, a nodal point in the Aegean. Sailing around south-west Samos is challenging year round, even though the area has a number of good anchorage points in use today, including Limnionas and Ormos and Kampos. Strong north to north-west winds persist not only in winter, but also in summer (as indicated by Windy.app that aggregates modern meteorological data). The channel between Samos and Ikaria was dangerous due to strong winds, as the large number of shipwrecks recovered around the Fournoi archipelago just south-west of Samos attests (Campbell and Koutsouflakis Reference Campbell, Koutsouflakis, Demesticha and Blue2021). Yet the same shipwrecks are testimony to the continued importance of this route throughout antiquity, despite its dangers. On balance, therefore, it seems possible that passage from Fournoi to south-western Samos could have been used on a regular basis during the sailing months in antiquity (Campbell and Koutsouflakis Reference Campbell, Koutsouflakis, Demesticha and Blue2021; Loy Reference Loy2024).

Little is known of the history of specifically south-west Samos, as ancient literary sources tend to refer to Samos generically, without discussion of specific regions within the island, or in relation to its central urban centre of Pythagoreio in the east. Epigraphic material recovered from this area is extremely rare too. Indeed, relatively little is also known of its archaeology. The most extensive exploration was Graham Shipley’s survey in the 1980s (Shipley Reference Shipley1987), which incorporated local knowledge, historical information, and extensive pedestrian survey. Shipley provided, on the one hand, the first synthetic account of Samian history from the Early Iron Age to the Hellenistic period and, on the other hand, a systematic catalogue of findspots with pre-modern activity based on previous knowledge supplemented with observations from visits to these sites. This information is extended by the continued work of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Samos and Ikaria, as reported in the Archaiologikon Deltion.

Within the permitted survey area of WASAP, Shipley identified Archaic to Hellenistic architecture at Agios Ioannis as well as Late Roman pottery scatters (Shipley Reference Shipley1987, map ref. 9504). In a southerly direction from the church at a lower elevation by the coast he reported Hellenistic blocks and Byzantine remains, but these areas are now built over by the expansion of the resort town of Kampos. Most archaeological remains in south-west Samos comprise Roman and Byzantine period activity, when a network of small-scale settlement and churches emerged (such as at Kareiika, Koumeiika and Marathokampos; Shipley Reference Shipley1987, map refs 9604, 0103 and 9605). In the plain around Velanidia (Shipley Reference Shipley1987, map ref. 9504), the remains include a Late Byzantine aqueduct and water channels and mills. Extensive surveys and rescue excavations by the Ephorate added to this material more recently, documenting marble architectural elements at Kampos, in addition to Velanidia and Agios Ioannis (Touchais Reference Touchais2004–5).

Overall, therefore, the evidence for natural resources and agricultural and other economic productivity, as well as maritime connectivities, suggests that south-west Samos would most likely have seen significant activity and occupation in antiquity. Despite this, what has hitherto been documented in the archaeological record remains scant, save for some tantalising hints of possible remains. This was the situation that WASAP set out to remedy.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY

WASAP used a mixture of methodologies in order to shed new light on the region (Fig. 3). At a preliminary phase, the study of historic aerial and satellite images allowed us to identify locations mentioned in earlier literature and areas of potential archaeological interest. This work was generously funded by a British Academy/Leverhulme Trust Small Research Grant.Footnote 5

Fig. 3. Diagram to show methodology of tract and minigrid walking, combined with pictures of team walking and gridding (diagram by Anastasia Vasileiou, Michael Loy and Naoíse Mac Sweeney; photographs by Fabiola Heynen and Michael Loy).

The primary methodology used by the WASAP team for systematic intensive survey was transect walking. Targeted collection in minigrids allowed us to learn more about specific locations that were of particular interest. Extensive survey was also undertaken. Information collected through all three methods was handled through a born-digital data acquisition process. Finally, drone photography enhanced our picture of the whole landscape at both an intensive and extensive level. The combination of different survey methodologies enables us to compare the results gained, and to consider the relative strengths and weaknesses of each method. An article giving more technical details and reflecting on the practice of the methodologies used in WASAP has already been published (Loy, Katevaini and Vasileiou Reference Loy, Katevaini and Vasileiou2024).

Transect walking

Pre-season, a grid was drawn by the GIS team over the entire survey area, comprising 50 x 50 m grid-squares. A map of target grid-squares was given by the GIS team to the field team leaders, along with the relevant Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) co-ordinates for grid-square corners. Field teams used Garmin eTrex10 GPS units to locate the grid corners, and to identify the relevant area for investigation. Once a grid-square was explored, in full or partially, it was recorded as a tract. Team leaders collected landscape information for each transect (tract), including data on viewsheds, landscape quality (slope, erosion type, vegetation coverage), and notes on possible human disturbance, and a photograph of the tract.

WASAP teams consisted of five walkers, spaced at 10 m intervals along the 50 m baseline of a regular-sized tract. Fieldwalkers progressed as far as the landscape allowed, up to 50 m from one side of the grid to the other in regular formation and following a fixed compass-bearing. The unit walked by a fieldwalker was referred to as the walkerline. For each tract, fieldwalkers made a subjective estimate on the surface visibility, recorded by each walkerline arbitrarily as a percentage (where 100% is near-perfect sight of the ground on a clear ploughed surface or similar, and 1% indicates it was almost impossible to see anything on the ground through thick vegetation or fallen leaves). Across each tract, fieldwalkers noted the total count of surface ceramics and tiles seen within a 1 m cone of vision either side of their line walked. During the statistical and geospatial processing of the data, ceramic counts were used at the level of the walkerline, i.e. giving sub-tract resolution to the survey dataset. If any notable features potentially of archaeological or historical interest were noted by fieldwalkers during transect walking, these were recorded as Points of Interest (POIs).

The collection strategy was to bring in all diagnostic sherds of any period found within the walkerline (rims, bases, handles, and decorated feature sherds). Team members also collected body sherds for each representative fabric type found across a walkerline; fabric samples were consolidated across a tract and duplicates were discarded.Footnote 6 A total collection of non-ceramic objects found within the walkerlines was also made.

Three different sampling strategies were used in exploring south-west Samos:

-

1. Total coverage was attempted in the immediate vicinity of Velanidia and Agios Ioannis, as both were identified in preliminary investigations as areas of particular interest. The boundaries of the survey area in each case were defined by roads and landscape features, as well as by the limits of the modern town of Kampos (for Agios Ioannis). Large sections (c. 12 ha) of landscape immediately west of Agios Ioannis were initially sampled but had to be removed from the survey area due to inaccessible terrain.

-

2. An intensive exploration of extensively identified features of interest was undertaken in both the West Kampos and Limnionas areas. Possible features of interest identified in aerial photography and through extensive POI exploration were covered with tracts. There was no set target size for these intensively explored extensive units; rather they were each explored by one walker team for one day. The coastal area of Limnionas was too large to explore by one team in one day, so the area was explored by alternating rows of walked and non-walked grid squares between the coast and road, over successive days.

-

3. The landscape connecting Velanidia and Agios Ioannis was targeted for further exploration. Although the plan had been for total coverage between these two areas, timing dictated that this would not be possible. Instead, the area was explored by alternating rows of walked and non-walked grid squares between Velanidia and Agios Ioannis.

In terms of coverage, the south-west area of Samos was investigated in 818 tract units, giving a coverage of 1.27 km2. Of these tracts, 223 (27.2%) were regular 50 x 50 m grids, and 594 were irregular in shape. In total 1.41 km2 were marked as unwalkable owing to inaccessible private properties or sheer topography, bringing the total area discussed here to 2.68 km2.

Minigrid collection

The minigrid methodology was developed to gain a higher resolution of spatial information from areas of particular interest. Areas investigated with this methodology were mapped in 10 x 10 m minigrids, set within the pre-existing tract grids. The 25 minigrids within each tract grid were each given a letter designation, with letters designated in regular locations from the north-west corner. Each minigrid therefore had a unique identifier comprising the number of the tract grid, followed by the letter showing its location within the tract grid (e.g. 3130-A). Finds from each minigrid were then labelled in the normal way following this (e.g. 3130-A-1). The minigrids were set up, and marked with flagging tape. Each walker started in the south-west corner of their grid, or as close as they could get to it, and walked back and forth at 2 m intervals for a total of five passes across the grid, ending in the north-east corner. Ceramics and other finds were recorded in the same way as for tracts. Each minigrid was documented on a paper form, which was later digitised onto KoBoCollect. Paper forms with space for free sketching were used to capture qualitative and impressionistic responses to the landscape and the progress of the work. The minigrid methodology was used solely during the 2024 season in the area of Velanidia, during which a total of 278 minigrids were considered, spread over sixteen tract grids.

Extensive survey

Outside of the intensive survey methodologies outlined above, extensive exploration was used to document features of potential archaeological or historical interest at a number of other locations in the south-west of the island. Such features were designated ‘Points of Interest’ (POIs), a ‘catch-all’ term that was devised to record any information relevant to the project’s research questions that did not fall within the remit of systematic tract or minigrid documentation. POIs were located in three main ways. First, exploratory visits were undertaken to locations that had been identified as being of potential archaeological interest. Such identifications were made on the basis of study of previous literature, study of aerial imagery, and thanks to information from local informants. Second, visits were made to locations that were identified as potentially of interest on the basis of their geographical or topographic features, such as springs, river courses, and hilltops. Third, while undertaking the core tract-walking, if any further features of interest were encountered (e.g. wall, cut feature, dense scatter of pottery, architectural feature), they were recorded as POIs.

Each POI was located by its GPS coordinates, recorded using the Garmin eTrex10 GPS units. Documentation was undertaken through a standard form that also gave team members free-text space to add interpretation or commentary on the features located. Categories of information documented for each POI included viewsheds, landscape quality (slope, erosion type, vegetation coverage), and notes on possible human disturbance. Landscape and feature photographs were also taken, and where relevant, ceramics could be collected using the same collection and documentation protocols as for transect walking and minigridding. POIs were originally assigned a temporary ID during data input, which was cleaned to a permanent ID off-season, with an integer sequence starting at P001.

Born-digital data acquisition

All field data were recorded on tablets using a set of pre-designed forms. Every fieldwalker was equipped with their own Alcatel or Samsung Android tablet, loaded with the open application KoBoCollect. This app connects to the project’s user area in the KoBoToolbox platform, a tool that enables born-digital data collection in areas of poor or zero access to cellular internet connection. KoBoToolbox allows for the creation of custom-built forms, prepared pre-season, designed either using KoBo’s online form builder or uploaded as an XLSForm specification. Form fields can be dropdown, multiple-choice or free-text; the forms can also handle image media, acquired through a tablet’s front or back camera. Once designed, these forms were ‘pulled’ from the team’s KoBoToolbox account pre-season to the tablets, allowing team members to access and input data to the forms from the field, i.e. offline. In the field, data that has been input to these forms was stored locally on the tablet. When the team returned to base, by connecting the field tablets to a stable internet or WiFi connection the data were ‘pushed’ from the tablet to the project’s KoBoToolbox account. Initial verification and cleaning were completed by the GIS and data team within the KoBoToolbox platform, and the flat table data were downloaded as CSV files and backed up.

Aerial survey

Aerial photography was acquired using a DJI Phantom 4 drone (Fig. 4) to obtain information of the visual spectrum at a higher resolution than was available from GIS basemaps (0.1 m v. 0.6 m resolution). The drone was flown over zones of interest using manual controls at a height of 30 m from the ground. Flights were conducted in regular linear passes and captured to video with a frame rate of 29.97 fs (3840 x 2160 px / 59874 kbps). From each flight video, every fifteenth frame was extracted to an image. The total batch of images was aligned, built in 3D and exported as an orthophoto in Agisoft Metashape (photos aligned under medium accuracy with generic preselection, 20,000 key point limit and 0 tie point limit; depth map generated on medium quality with mild filtering; and the creation of a texture with generic mapping, mosaic blending, and texture size of 2048; orthophotos were exported at 96 dpi, with bit depth 32 and LZW compression add metadata details). Orthophotos were georectified on visual comparison with GIS basemaps. The acquisition of drone photography was non-systematic, owing to the availability of personnel, flight restrictions imposed by the authorities in proximity to military zones, and weather conditions. Drone photography covers only 338 grid squares of the surveyed area. In south-west Samos, thirteen orthophotos of the landscape were produced, covering 0.56 km2.

Fig. 4. Aerial imagery from south-west Samos (photographs by Michael Loy).

OVERVIEW OF SURVEY RESULTS BY GEOGRAPHICAL ZONES

The survey identified five main zones within south-west Samos in which WASAP worked (see Fig. 2). In this section, a brief geographical overview of these microregions, and the work done in them, will be given. In what follows, identification numbers will be given for POIs in bold.

The zones are, from east to west:

-

1. Velanidia: the area between the modern fishing port of Ormos and the village of Koumeiika.

-

2. Ormos: the area around Ormos and the eastern section of the seaside resort of Kampos.

-

3. Agios Ioannis: the area around the central section of Kampos.

-

4. West Kampos: the area around the western section of Kampos.

-

5. Limnionas: the area around the village of Limnionas.

Velanidia

The area known locally as Velanidia can be characterised as a flat, low-lying basin of roughly 2 km x 1.5 km in size, bounded by the beach in the south and ringed by hills to the east, north, and west. The village of Koumeiika lies in the eastern hills, which rise from there upwards on the north-east to become the foothills and lower slopes of Mt Kerkis. The modern fishing port of Ormos lies at the westernmost point of the basin. Most of the basin is under cultivation, being well watered by two streams, the Kamares and the Megalo Rema, running down to the coast from the northern hills. As a result, some more southerly areas of the basin are thick with maquis and reeds. The historical importance of the water supply here is underlined by the remains of a sizable post-antique aqueduct, preserved in two locations (P048, P294), and the remains of an abandoned mill (P144, P143). A modern reservoir constructed in 1991 demonstrates the continuing importance of the area in this respect. The hills themselves are for the most part covered in agricultural terraces, largely planted with olive trees.

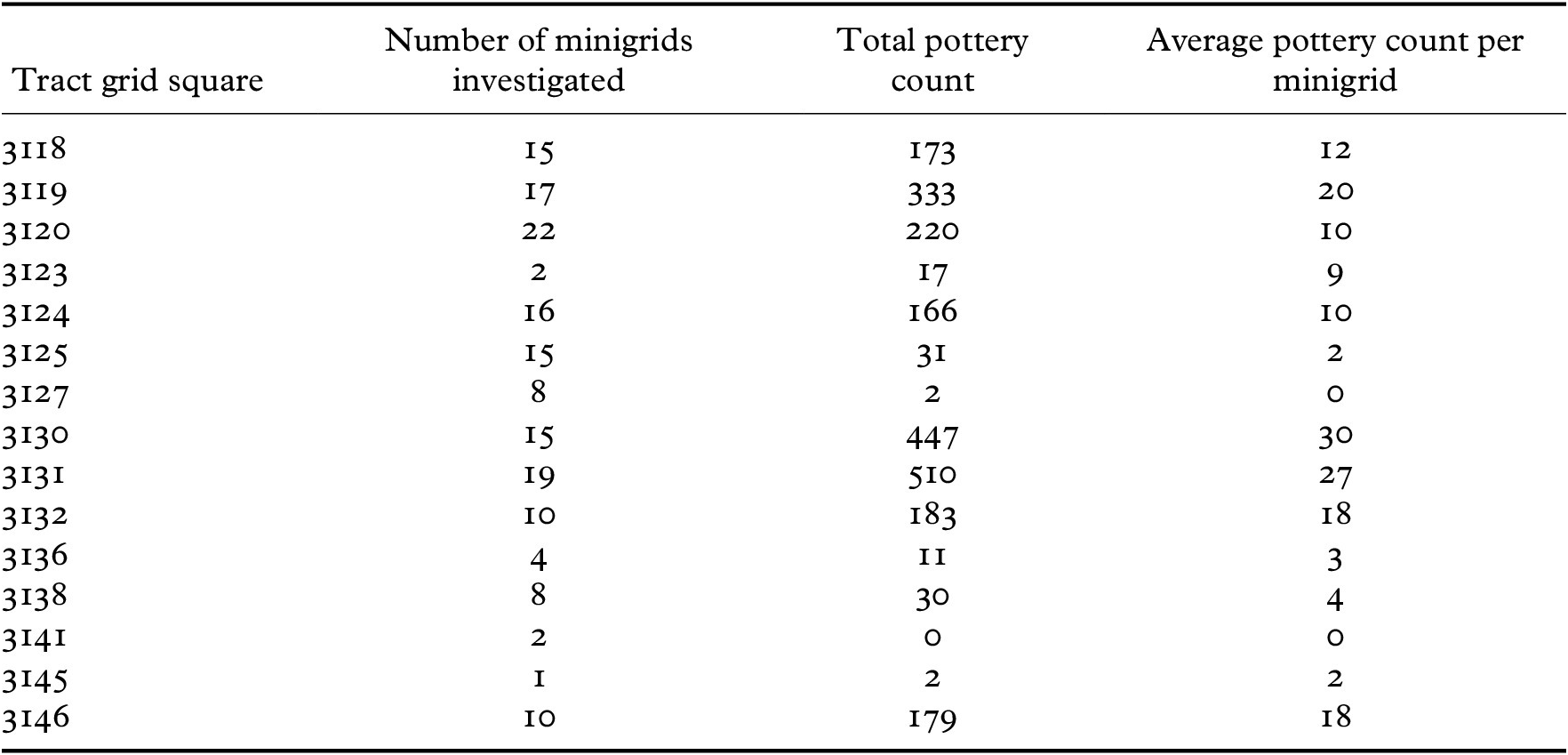

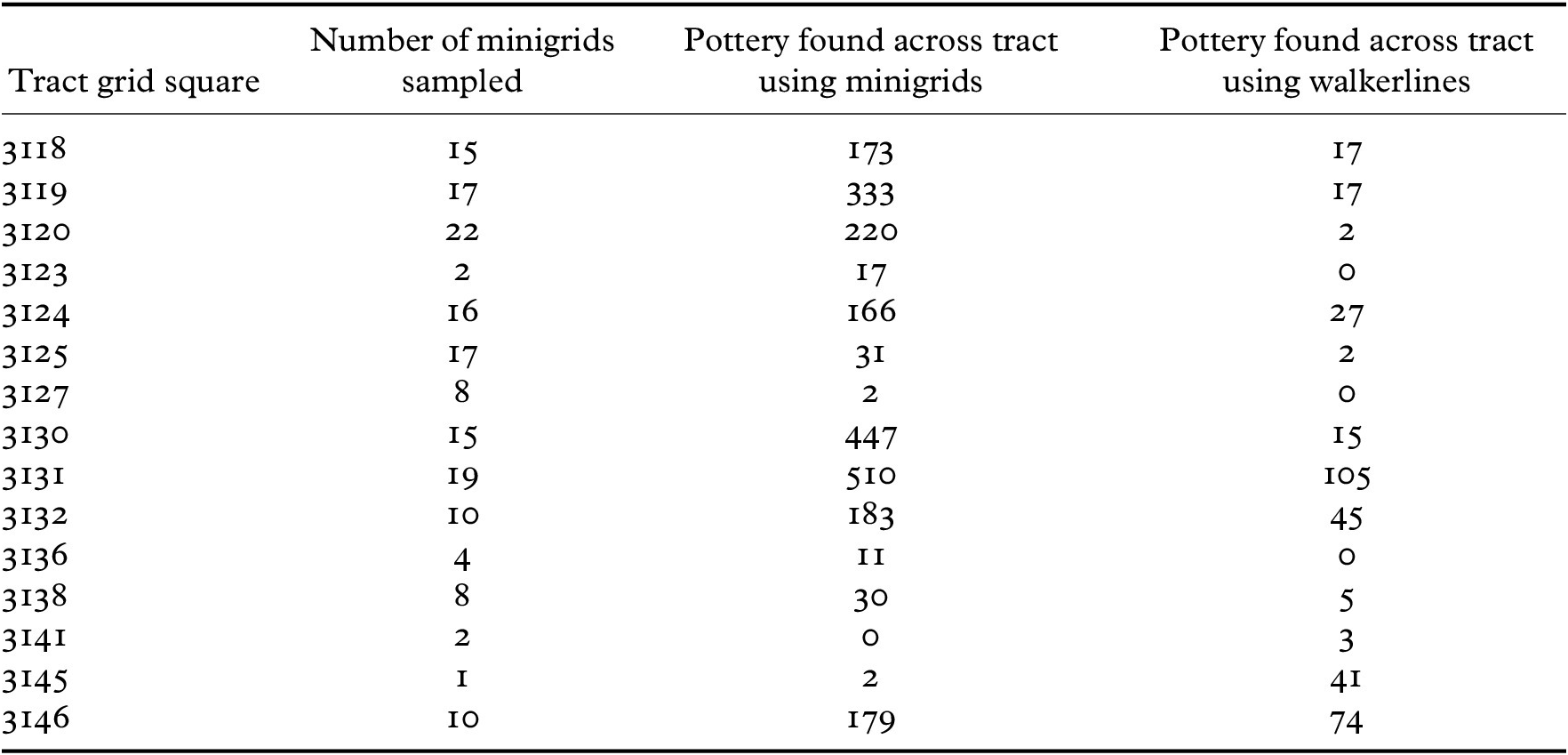

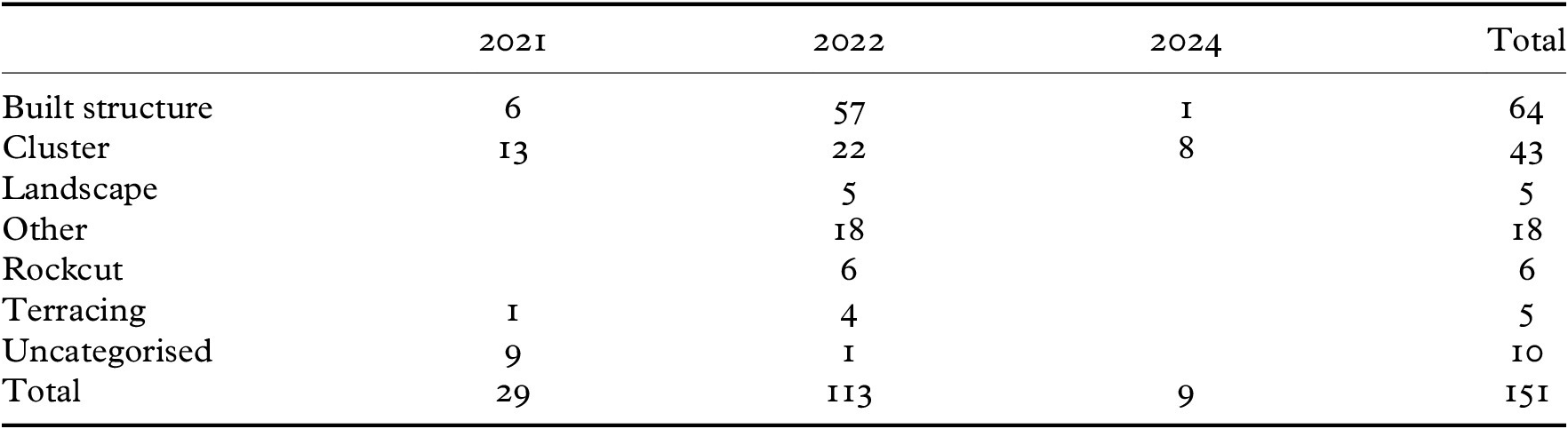

This area was initially explored in 2021 with extensive survey, and in 2022 with tract walking (Table 1). We returned to the area in 2024 for more targeted investigation using the minigrid methodology (Table 2), and a small amount of further tract walking. Extensive survey in the surrounding hillsides was also undertaken in both 2022 and 2024 (Table 3). In addition, approximately 0.24 km2 of the Velanidia basin was documented as an orthophoto through drone flight. The orthophoto comprises five images composited, from five separate flights: strong wind conditions prevented more extensive drone flying from being completed in most of the basin.

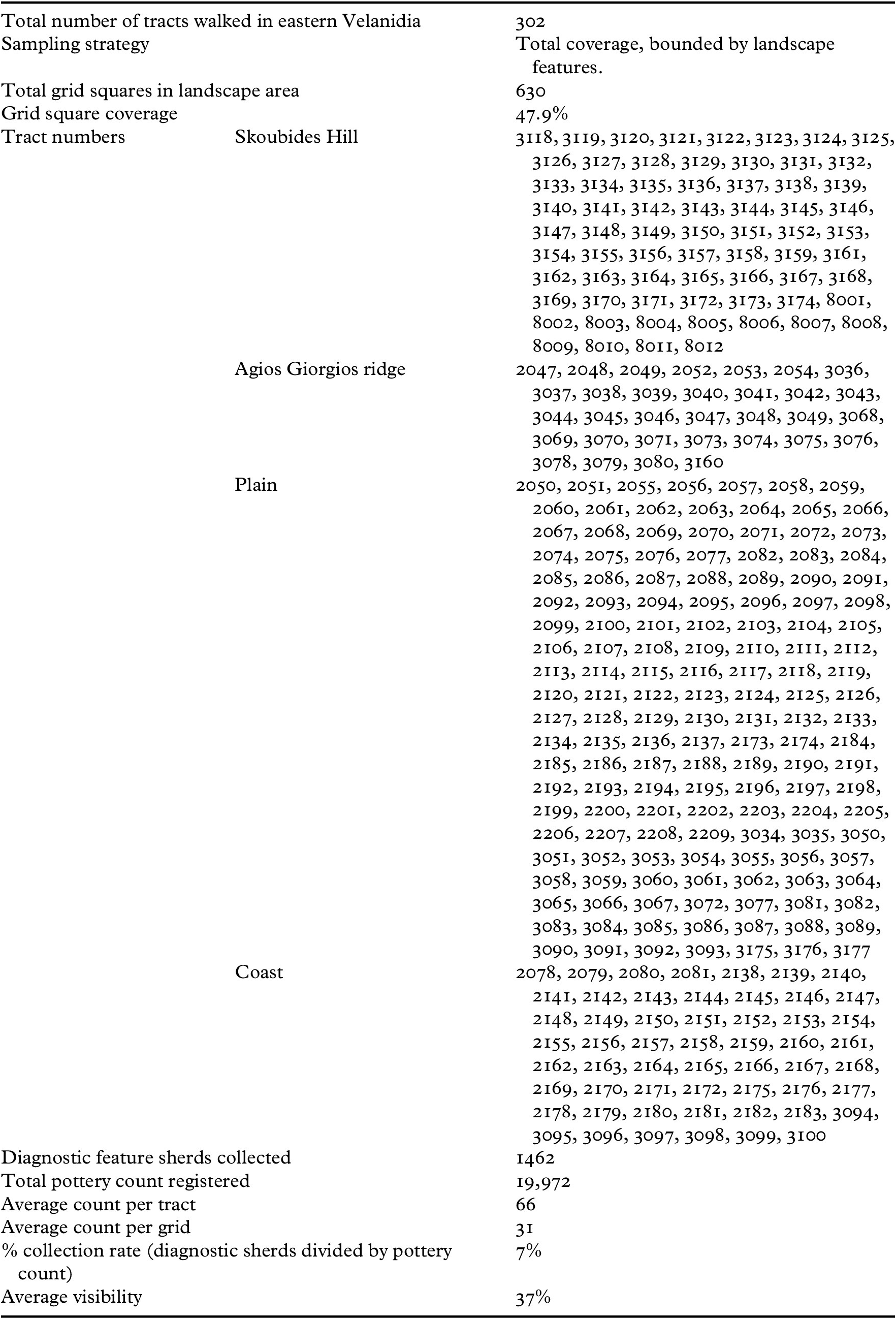

Table 1. List of tracts walked in the eastern Velanidia basin

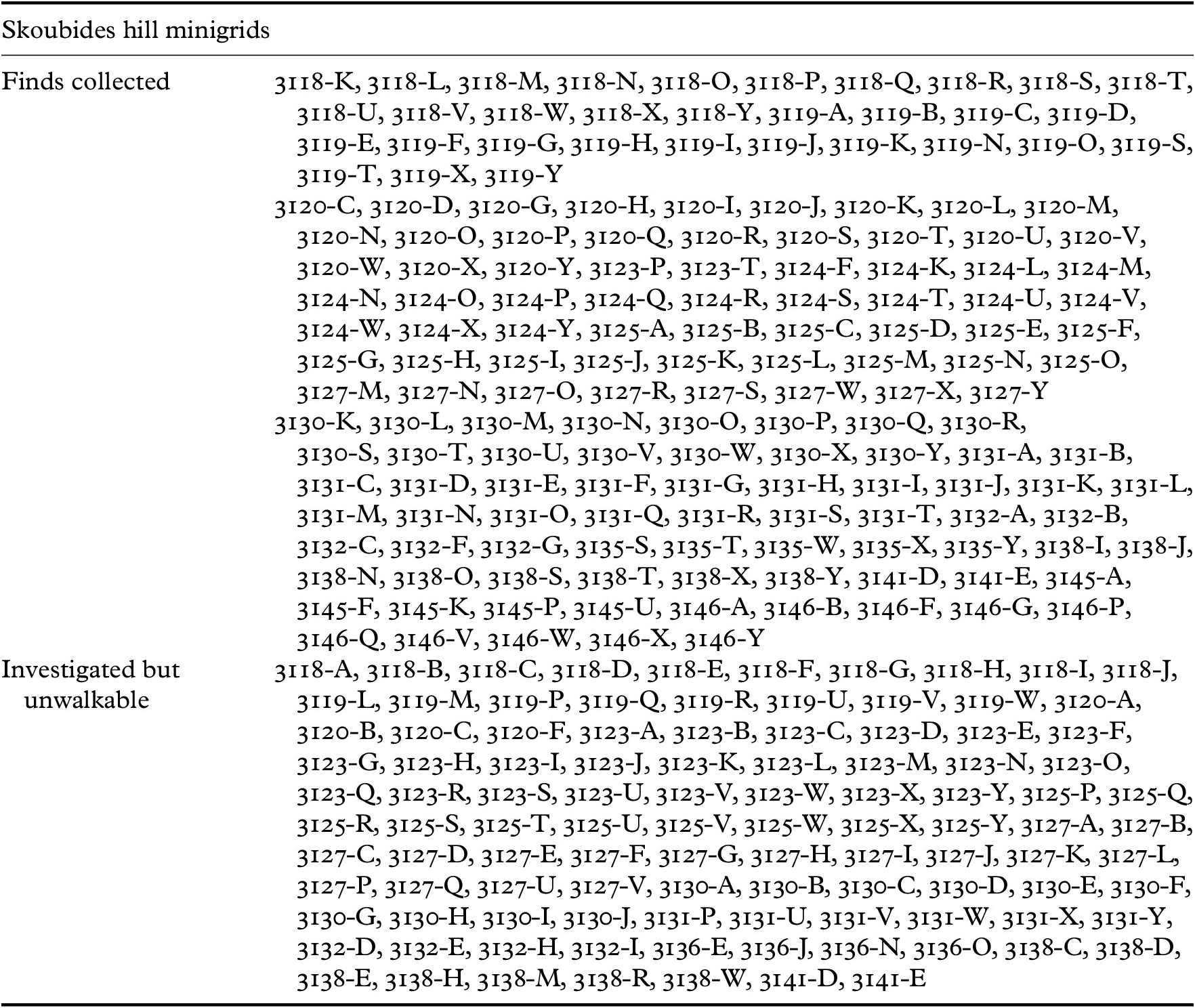

Table 2. List of minigrids investigated on and around Skoubides hill

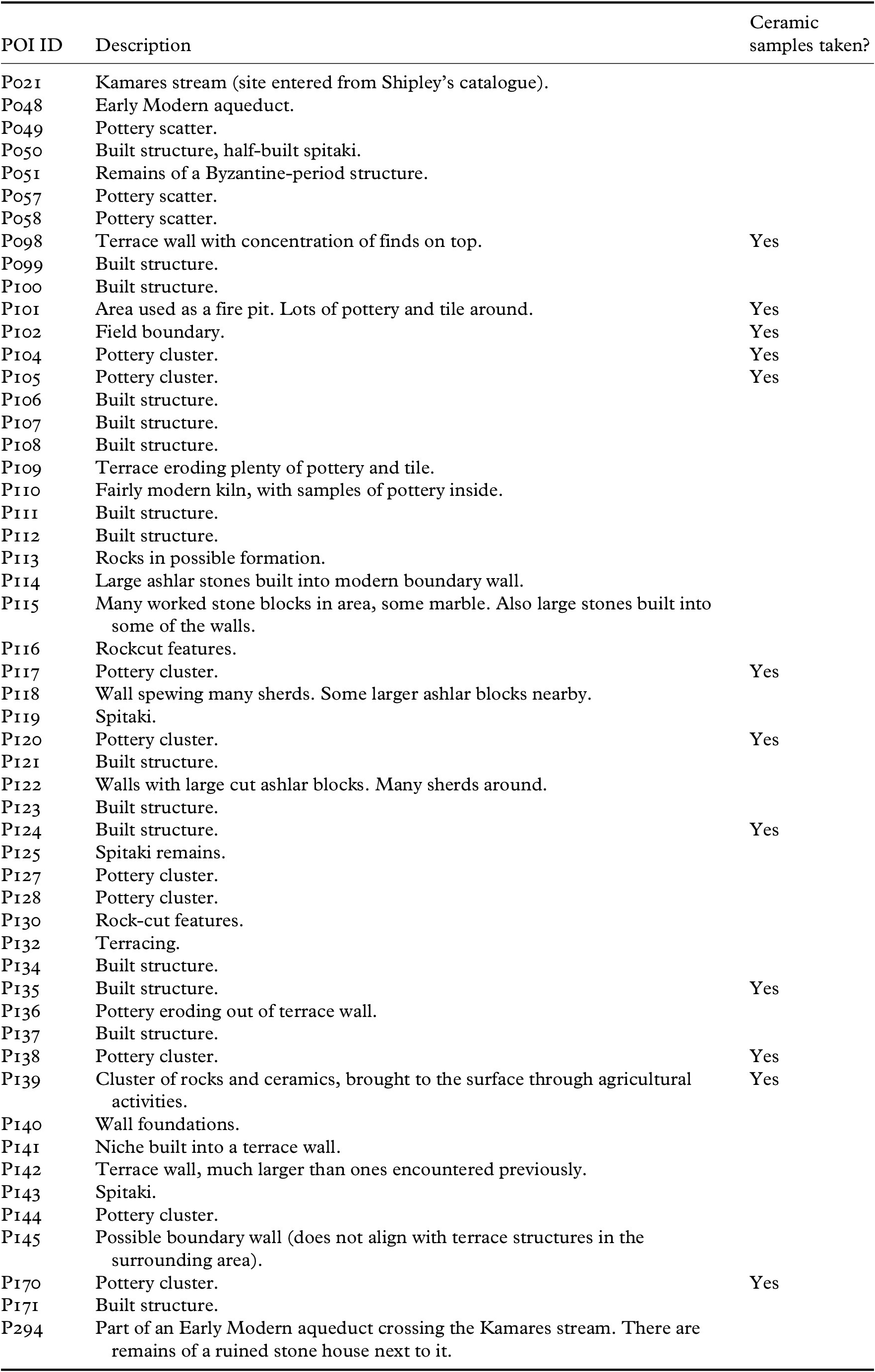

Table 3. List of POIs in the eastern Velanidia basin

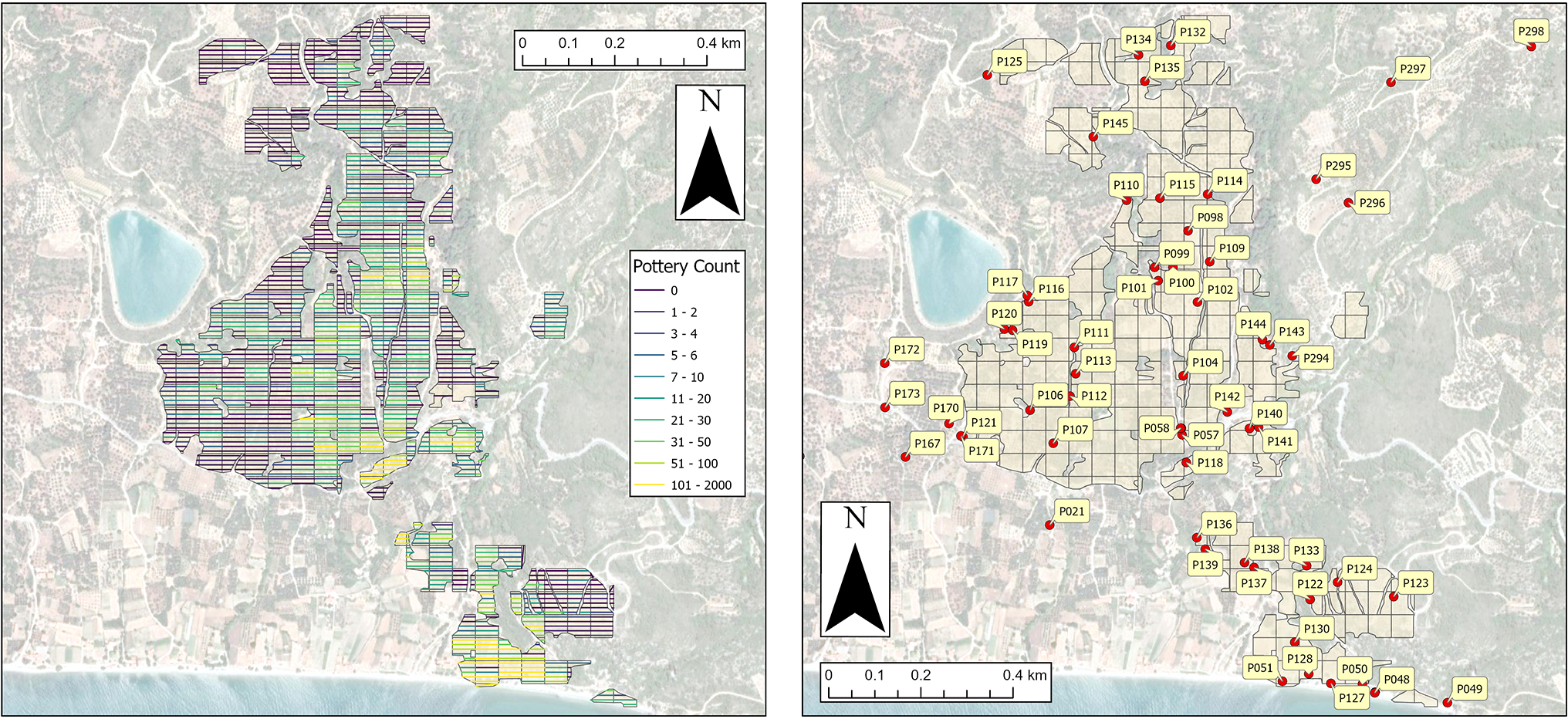

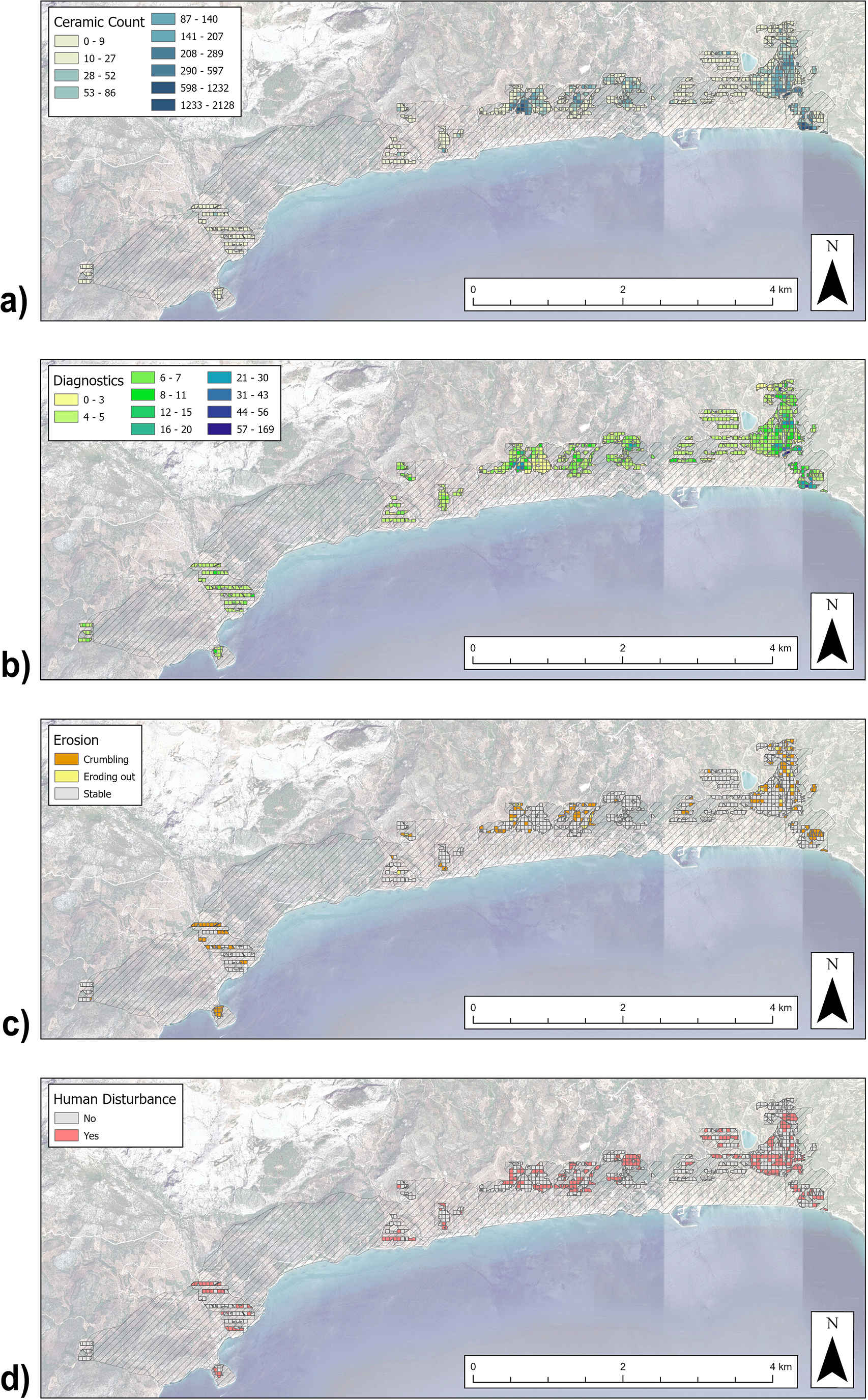

In the Velanidia basin the landscape was fairly consistently walkable (302 tracts were walked out of a total area of 630 grids). Areas were deemed unwalkable due to the dense vegetation and marshy land in the case of the low-lying areas, or due to the steepness of the slope on the northern and eastern edges of the basin, where the landscape rises into the hills. Exploratory work quickly identified a noticeable difference between the western portion of the basin (between Ormos and the modern reservoir) and the eastern portion (between the reservoir and the stream and hillside known locally as Kamares). Relatively little material was recovered in the western portion (491 sherds counted in total across 72 tracts, resulting in an average of 7 sherds per tract). The only areas in this zone that yielded material were old river beds. A number of POIs were nonetheless documented in this area. Of particular interest are P172 (an area with possible cut masonry, including the eroded remains of a circular stone-cut feature) and P174 (an unusual rock formation with cuts, perhaps indicating that blocks have been quarried from it). Please see online Supplementary Material for close zoom maps showing the locations of tracts (nos 17–20).

In comparison, high densities of material were collected in the eastern portion of the Velanidia basin (Fig. 5; 19,972 sherds counted in total over 302 tracts, resulting in an average count of 66 sherds per tract; see Table 1), beginning from the hills in the north and continuing to the coast in the south. This material ranges in date from the Archaic to the Middle Byzantine periods, although there is noticeably less material dating to the Roman period. Spatially, four concentrations of surface ceramics can be identified in the eastern Velanidia basin, suggesting that different portions of the basin were used in different ways in different periods of antiquity. This area will be the subject of a separate article (Mac Sweeney et al. Reference Mac Sweeney, Heynen, Kopanaki and Regazzoniforthcoming).

-

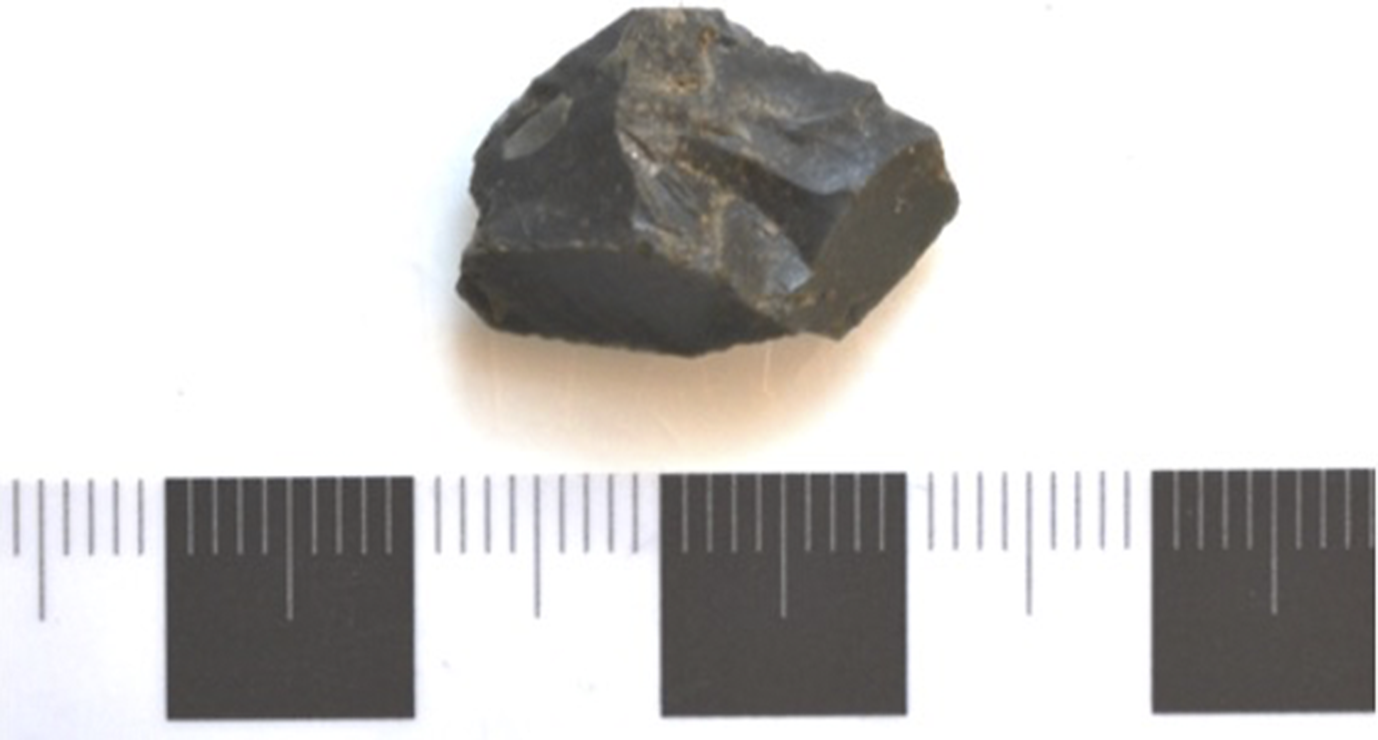

• The most northerly of these was on a small hill, two grids in size, overlooking the basin from the north, known locally as ‘Skoubides’. Ceramics from the Skoubides area are predominantly Archaic fine tablewares, and the assemblage notably included a small blue scarab (P135-1; Fig. 6). The unusual nature of this material prompted us to investigate the area with a drone flight in 2022; and to return in 2024 to conduct minigrid collection and some additional tract walking (Fig. 7). See online Supplementary Materials for a close-zoom map of Skoubides hill, showing the locations of the minigrids. The summit of the hill itself is covered in dense maquis, and it was therefore extremely hard to collect material here. However, significant amounts of material were collected on the western slope (830 sherds counted), once more predominantly comprised of Archaic finewares, which appears to be eroding from the summit. The other sides of the hill did not display the same pattern. To the east, the hill drops steeply down to the Kamares stream, and little was collected on this slope due to the precipitous nature of the terrain. On the north (280 sherds counted) and south (345 sherds counted) slopes, less material was collected, despite the terrain and erosion processes appearing to be similar to those on the western slope. At the south-eastern foot of the slope, micro-concentration of finds includes ceramics from the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods, while on a small plateau to the north-east, another micro-concentration appears to predominantly consist of Archaic finds.

-

• The second concentration of surface ceramics was identified along the ridge south of the church of Agios Giorgios, and contained material from the Classical through to the Byzantine periods, but with a prominent signature from the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Two POIs in this area (P114, P115) documented the large blocks of ashlar masonry, including some blocks of marble, which may be the remains of ancient architecture. Fragments of an ancient beehive were also collected here (P120).

-

• The ceramics collected from the third concentration point, on the flat plain of the basin at the base of the Agios Giorgios ridge, included material from all periods, but particularly notable is the presence (albeit in small quantities) of Roman ceramics, as well as the dominance of Byzantine ceramics (c. 42% of all sherds dated from this cluster). Within this area, a collection of ashlar masonry blocks was found (P118), as well as a niche and several other irregularities in terrace walls that might be the result of the incorporation of blocks of historic masonry (P140, P141, P142).

-

• The fourth point of concentration lay close to and on the coastline, itself different once more (c. 10 grids in size, roughly 2 x 5 m in arrangement). In this area, Byzantine ceramics are dominant, with fewer sherds of other periods present. A collection of ashlar masonry has also been recorded in this area (P125).

Fig. 5. Left: map of the eastern Velanidia basin, with walkerlines by ceramic count. Right: map with location of tracts and POIs labelled (images by Michael Loy).

Fig. 6. The scarab found on Skoubides hill (photographs by Francesca Zandonai).

Fig. 7. Bottom left: map of Skoubides hill, showing location of minigrids. Top left: view over Skoubides hill. Right: map of minigrids by ceramic count (image by Michael Loy).

Extensive survey was conducted in the areas north and east of the Velanidia basin in 2022 and 2024 (Table 4). The northern hills yielded no notable archaeological remains, and as a result no POIs were documented in this area. The remains of a post-antique stone structure were, however, documented on the hill immediately to the west of Skoubides across the Megalo Rema, known locally as ‘Algaiika’ (P125). Some ancient activity may be inferred, however, from evidence in the hills immediately to the east of the Velanidia basin across the Kamares stream (Fig. 8). Clusters of ceramics were found at several locations on the plateau of Iatrokallina (documented as P295, P296, P297 and P298). These were primarily Archaic in date, but also included some Hellenistic and Byzantine pieces. Further to the east, in the hills between Iatrokallina and Koumeiika, P068 and P069 are remnants of potentially ancient masonry.

Table 4. List of POIs in the area east of Velanidia

Fig. 8. Map of the areas east of Velanidia explored through extensive survey, with locations of POIs labelled (map by Michael Loy).

On the plateau south of Koumeiika, one particularly dense concentration of ceramics is spread over several fields and displays several noteworthy characteristics (P313 and P317). The ceramics from this area were primarily Archaic in date, although a sherd of an Early Iron Age hand-formed vessel (P316-9) was also identified. Five ground stone tools (Fig. 9; P316-13, P316-2, P316-15) and four chipped stone lithics were also reportedly found here (P316-14, P316-16). In nearby areas, also to the south of Koumeiika, several ceramic clusters suggest activity during the Byzantine period (P315, P317), including one where rock-cut features were also found, perhaps suggestive of tombs (P314).

Fig. 9. Two of the ground stone tools collected at a POI south of Koumeiika (illustration by Bettina Bernegger).

Ormos (including the western Velanidia basin)

This zone includes the area immediately north of the fishing port of Ormos, as well as the neighbouring area immediately north of the eastern portion of the seaside resort of Kampos. Both areas are characterised by the same topography, featuring low hills and a mixed terrain varying between ploughland, fallow and dense maquis. This area was explored with tract walking, mostly during the 2022 season although some tracts were also walked here in 2021 (Fig. 10; Tables 5 and 6). The unevenness of the terrain and density of the maquis meant that tracts were only walkable here in relatively small patches. An area of c. 1 km was sampled with alternate east–west lines of walked and non-walked tracts, connecting the Velanidia and Agios Ioannis zones, where a total coverage strategy had been employed. See online Supplementary Materials for close zoom maps showing the location of tracts (nos 10–16).

Fig. 10. Above: map of the Ormos zone, with walkerlines by ceramic count. Below: map with location of tracts and POIs labelled (images by Michael Loy).

Table 5. List of tracts walked in the Ormos zone

Table 6. List of POIs in the Ormos zone

A concentration of ceramics was found immediately at the northern edge of Ormos itself. For the most part, this material dated to the Roman and Byzantine periods (44% of total assemblage dated from this cluster). In the same area a number of potentially ancient architectural features were also documented (P176, P177, P178). In the central and western part of this zone, the ceramics collected were mostly Early Byzantine in date (34% of total assemblage dated from the central and western portions of the cluster). Sherds from earlier periods (including Archaic [8.1%], Classical [2.3%] and Hellenistic [6%] sherds, and one potentially Early Iron Age fragment) were mostly small and very abraded. No potentially ancient architectural remains were recorded.

Agios Ioannis

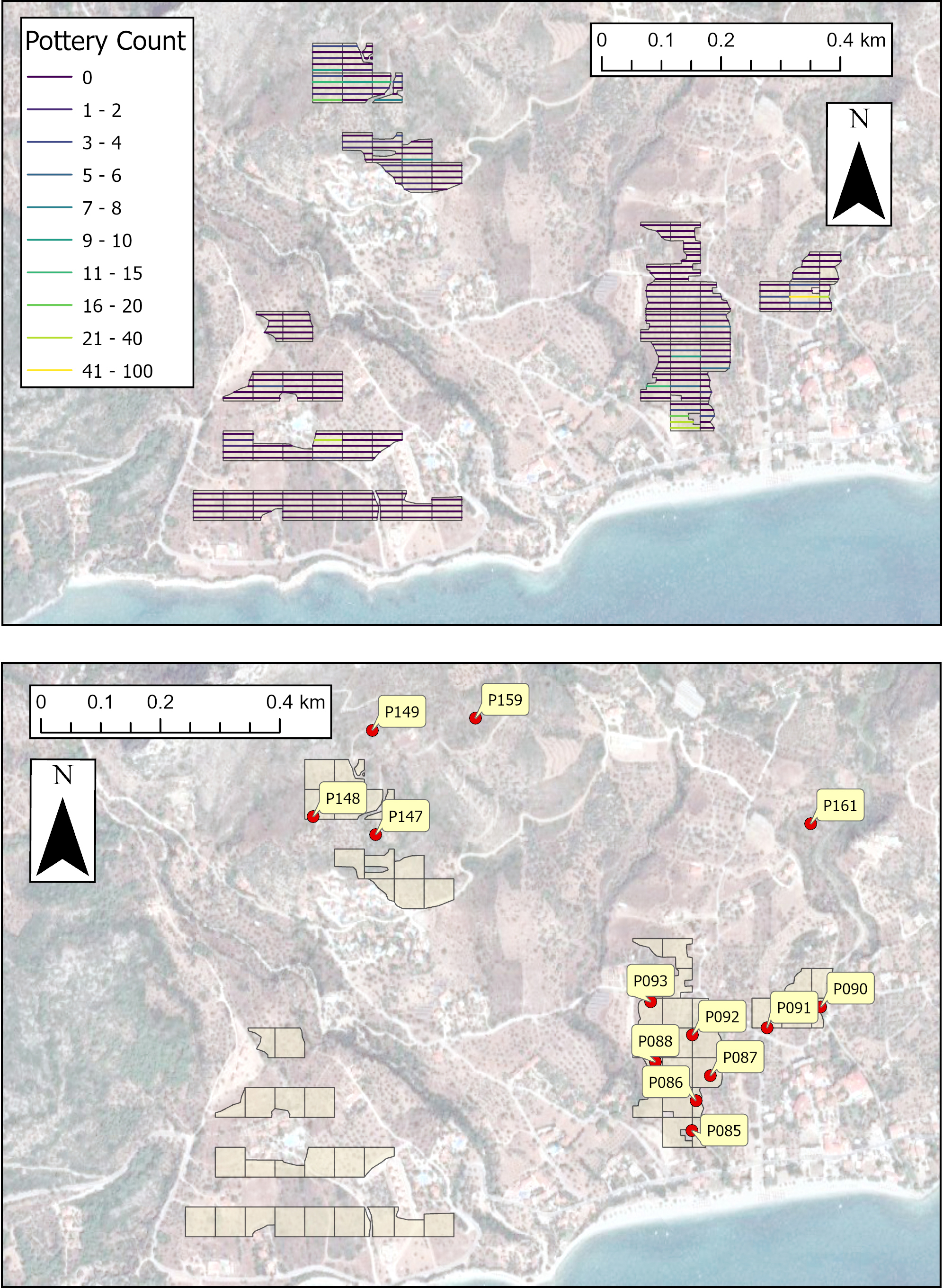

Above the central portion of Kampos, at the top of a series of high terraces, is a post-antique church dedicated to Agios Ioannis. This zone attracted the attention of antiquarians in the past (Guérin Reference Guérin1856, 283–4; Kritikidis Reference Kritikidis1869, 54; Bent Reference Bent1886, 146–7), and was also documented by Shipley (Reference Shipley1987, 254, map ref. 9504). Shipley in particular noted the presence of large blocks of ashlar masonry forming a rectangular structure, which he surmised might be a late Archaic or Classical fort. He also recorded remains of ancient marble architecture on the hillside immediately below the church, including columns, cornice pieces, and one inscribed block, as well as ancient material including a marble lintel built into the church itself. Both Shipley and earlier investigators mentioned significant quantities of ceramics visible on the surface in this zone. For this reason, the area around Agios Ioannis was the first location that WASAP targeted for study, and tract walking was undertaken here in 2021 and 2022 (Fig. 11; Tables 7 and 8). The immediate vicinity of Agios Ioannis was documented in orthophoto by drone flight, including an area 200 m north and 200 m east of the church. See online Supplementary Materials for close zoom maps showing locations of tracts (nos 8–9).

Fig. 11. Above: map of the Agios Ioannis zone, with walkerlines by ceramic count. Below: map with location of tracts and POIs labelled (images by Michael Loy).

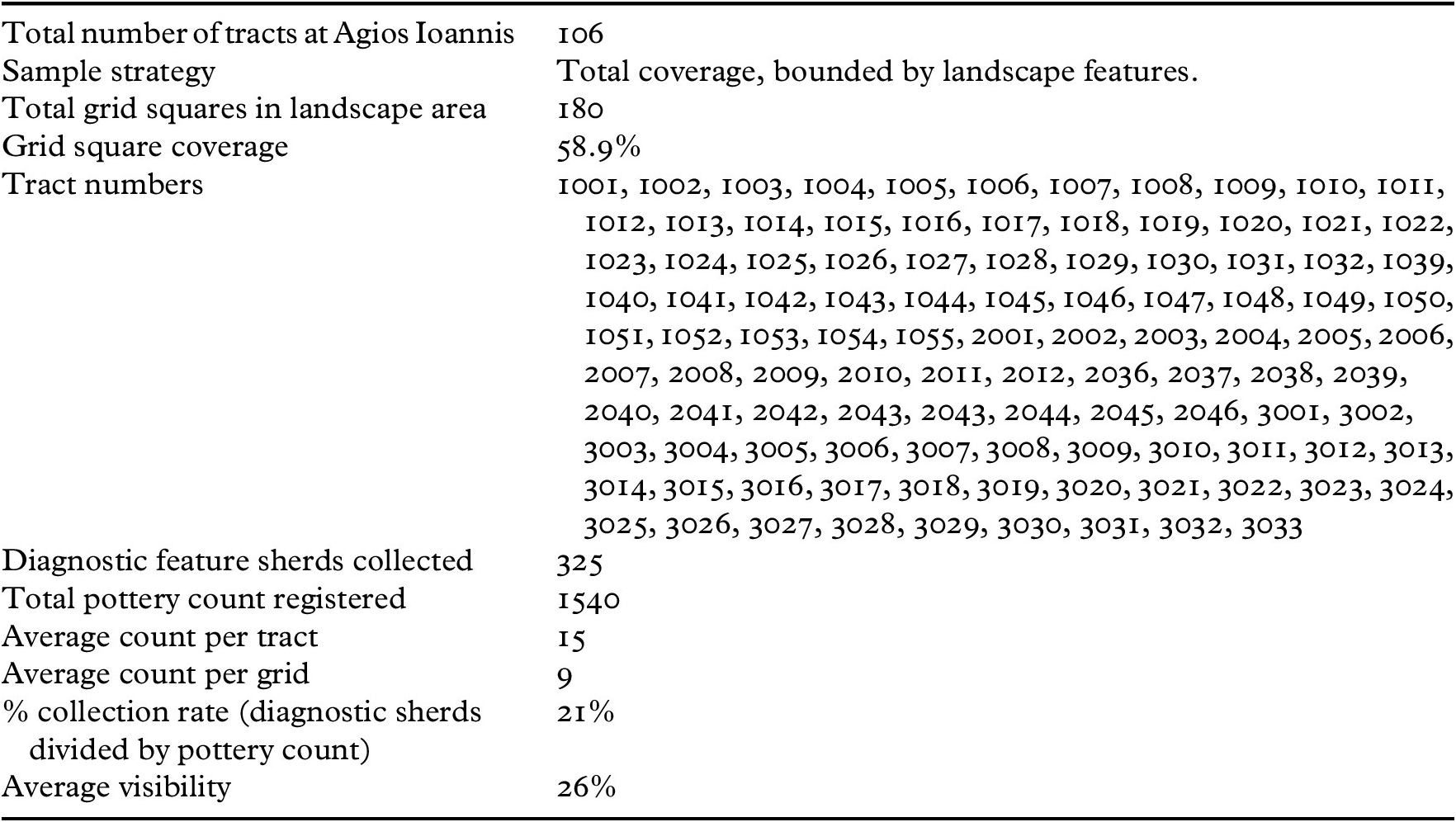

Table 7. List of tracts walked in the Agios Ioannis zone

Table 8. List of POIs in the Agios Ioannis zone

The terrain in this zone is fairly regular and walkable (106 tracts walked out of 180 possible grid areas). The terraces are flat with thin soil, plentiful olive cultivation, and small areas fenced off for the farming of livestock (mainly chickens and goats). Erosion of the whole area is stable, but there are a number of rubbish dumps right by the church.

The work of WASAP in this zone revealed slightly less material than might have been expected given the reports from earlier studies. Low quantities of surface ceramics (1540 sherds counted in total over 106 tracts, resulting in an average count of 15 sherds per tract; see Table 7) might be attributed to landscape changes as a result of housing development and shifts in farming practice during the intervening decades. Nonetheless, we documented significant amounts of ceramics in the area immediately around the church of Agios Ioannis itself, as well as just to its north-east. These ceramics were mostly Byzantine in date (75%), although a small number of Classical (1.5%), Hellenistic (5%) and Roman (6%) sherds were also identified (Table 15c).

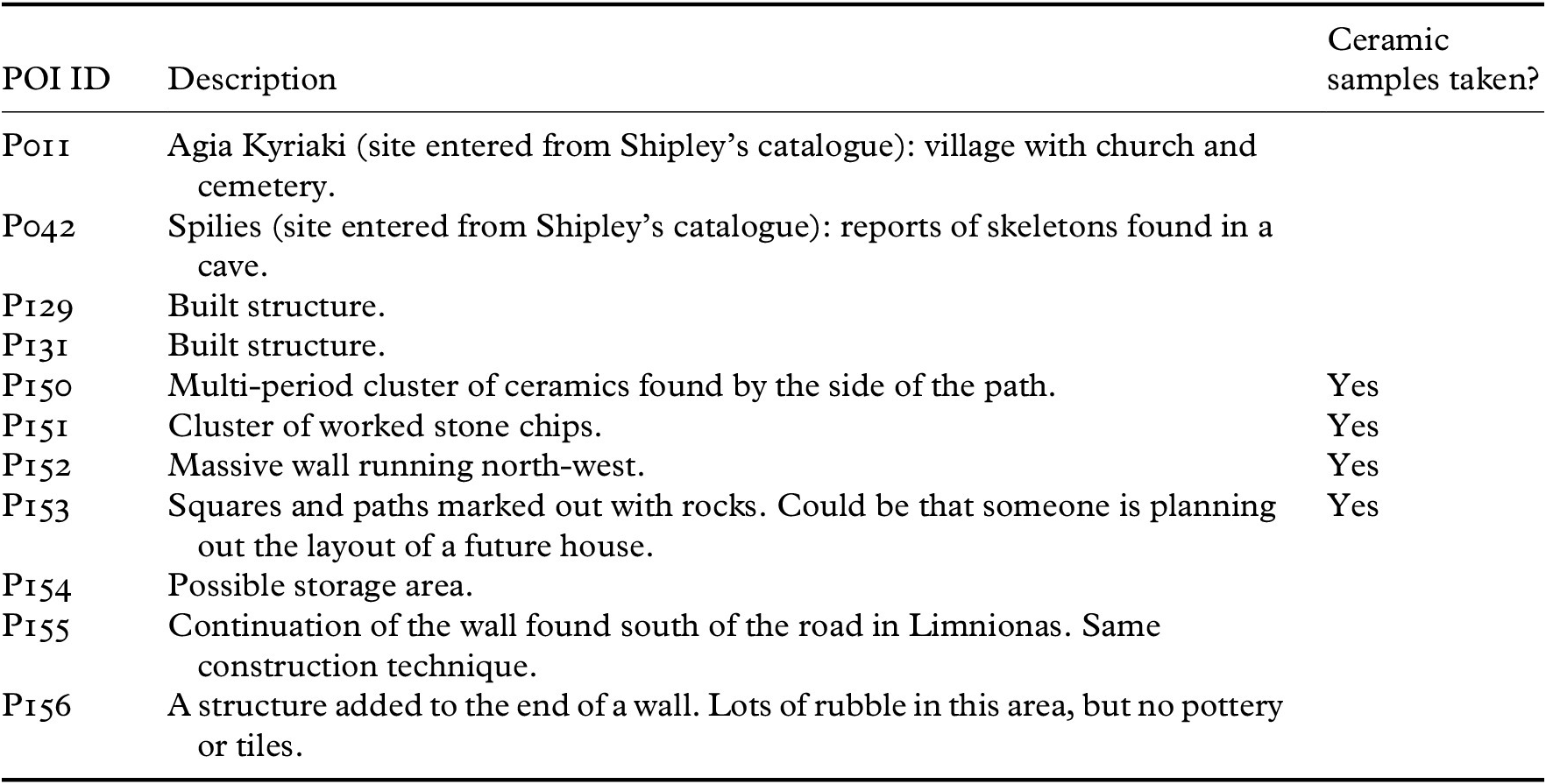

The lower courses of a rectangular masonry structure are still intact, perhaps constituting the remains of the building originally documented by Shipley (P005; Fig. 12). Without further specialist study, however, the date of this structure is still obscure. Remains of marble architecture were recorded at several locations in the immediate area (P064, P070, P076, P079, P083, P087, P088), and the reuse of what might be blocks of ancient limestone masonry were even more common.

Fig. 12. The rectangular masonry structure at Agios Ioannis zone, as documented in 2021 (photogrammetry by Michael Loy).

West Kampos

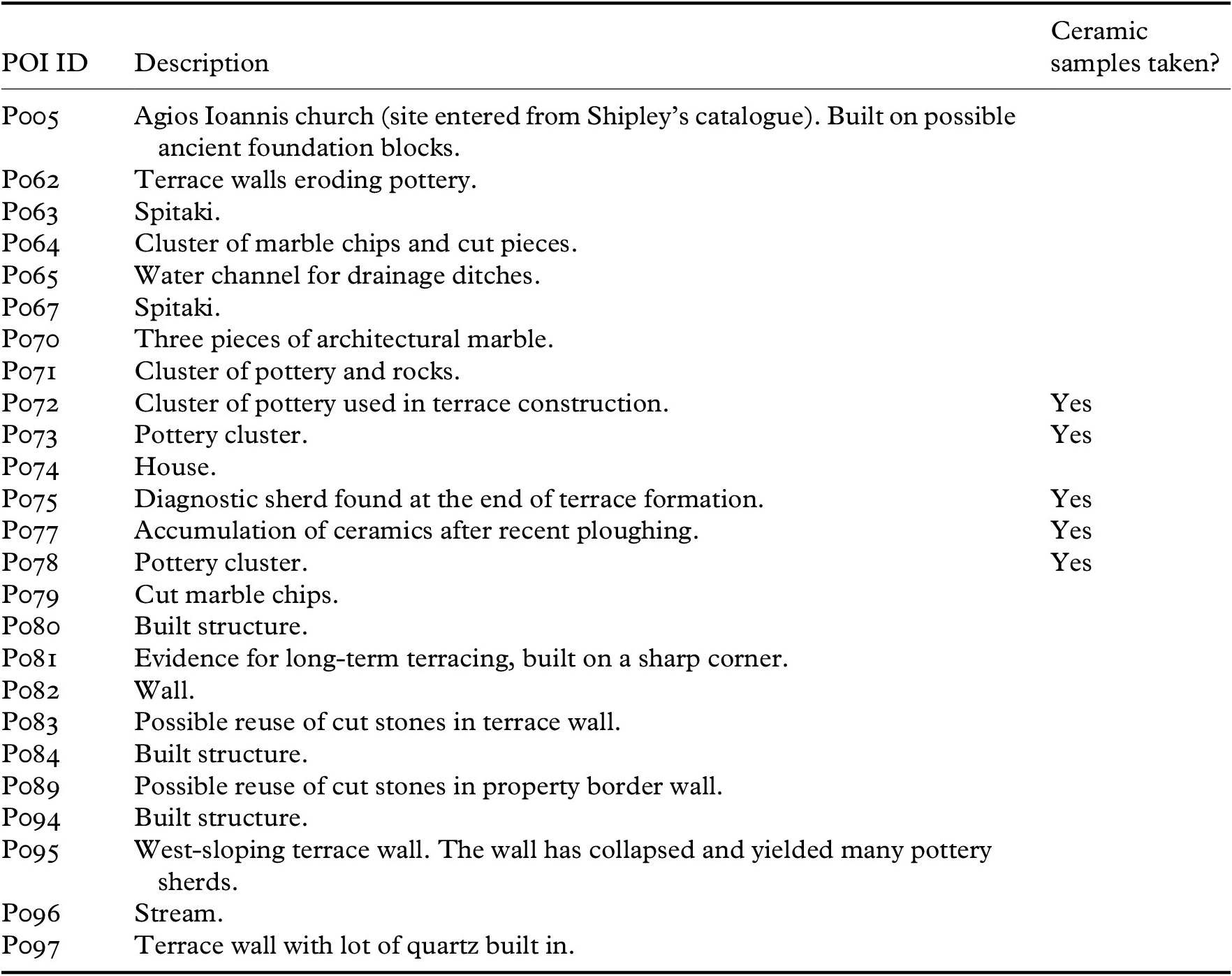

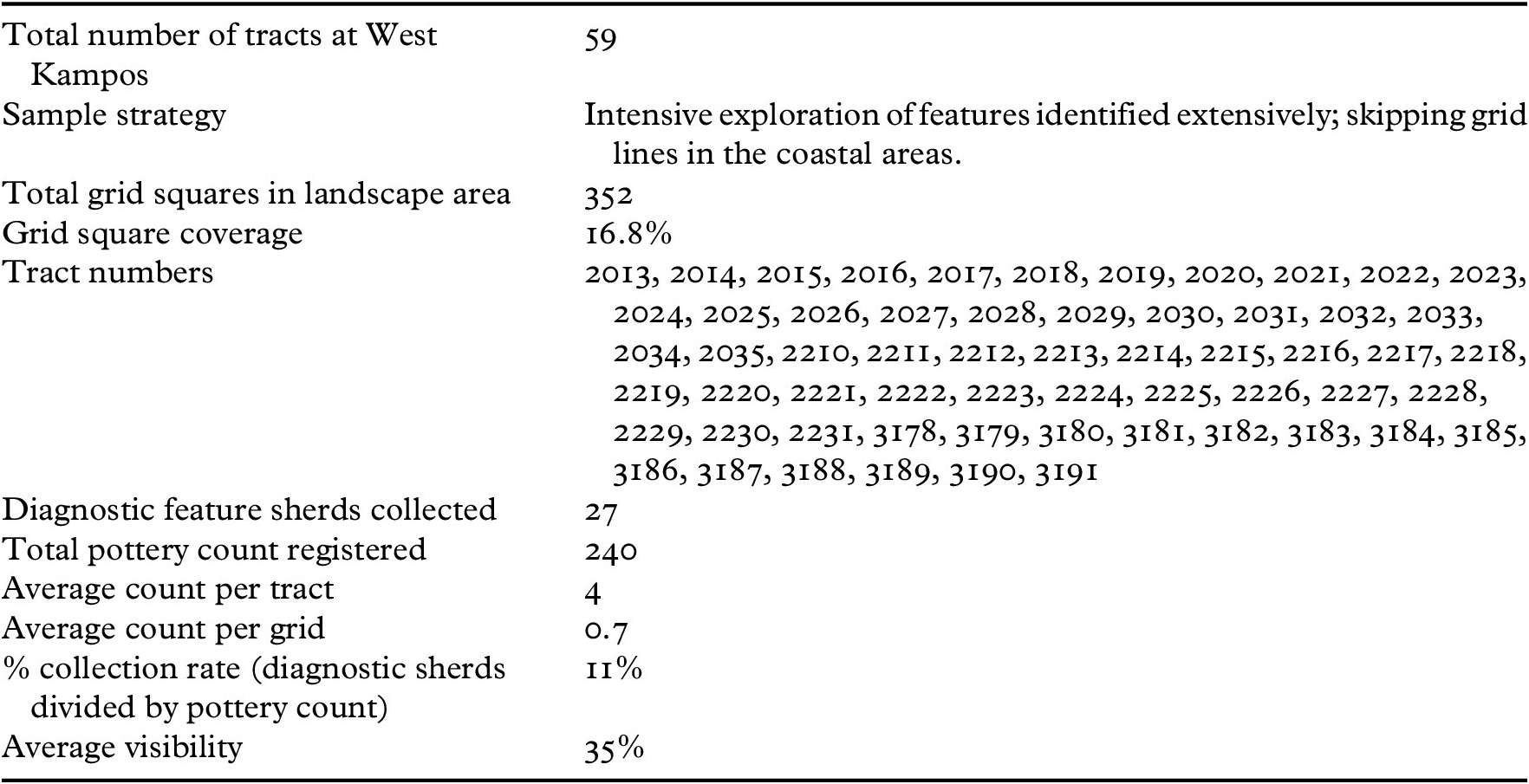

The WASAP team explored the zone of West Kampos with exploratory tract walking in 2022 (Fig. 13; Tables 9 and 10). The landscape did not allow for a full coverage of intensive tract walking in this area, but different locations were targeted with different questions in mind. The general aims of this work were twofold. First, we sought to investigate a number of features identified through analysis of the satellite imagery, ascertaining whether or not these were of archaeological interest. Areas explored included the fields directly west of Kampos, and on the high ridge towards the church of Panagia Sarandaskaliotissa. Here, the hillsides were extremely steep (any terraces were old and crumbling), with little modern cultivation and very high-grown maquis. The whole area walked was documented by drone flight, producing both an orthophoto and a 3D topographic map of the hillside. See online Supplementary Materials for close zoom maps showing locations of tracts (nos 5–7).

Fig. 13. Above: map of the West Kampos zone, with walkerlines by ceramic count. Below: map with location of tracts and POIs labelled (images by Michael Loy).

Table 9. List of tracts walked in the West Kampos zone

Table 10. List of POIs in the West Kampos zone

In the lower area, there were a number of low-lying deep-soil field systems for the cultivation of tomato, potato, and other crops, irregularly distributed between a number of villas and private properties. None of the features identified through the aerial images proved to be of archaeological interest, and in general, very little archaeological material was found in this zone (960 sherds counted in total over 240 tracts, resulting in an average count of 4 sherds per tract; see Table 16). In the upland area of the zone, the few sherds collected were Early Byzantine or Early Modern in date, located around disused Early Modern spitakia.

Our second aim in this zone was to continue our systematic sample of the coastal landscape. To this end, the westernmost area of this zone was explored right down to the seafront, using the same sampling strategy of walked and unwalked east–west tract lines as at Ormos. Here, the slope was shallow with stable erosion and low densities of maquis and fallow.

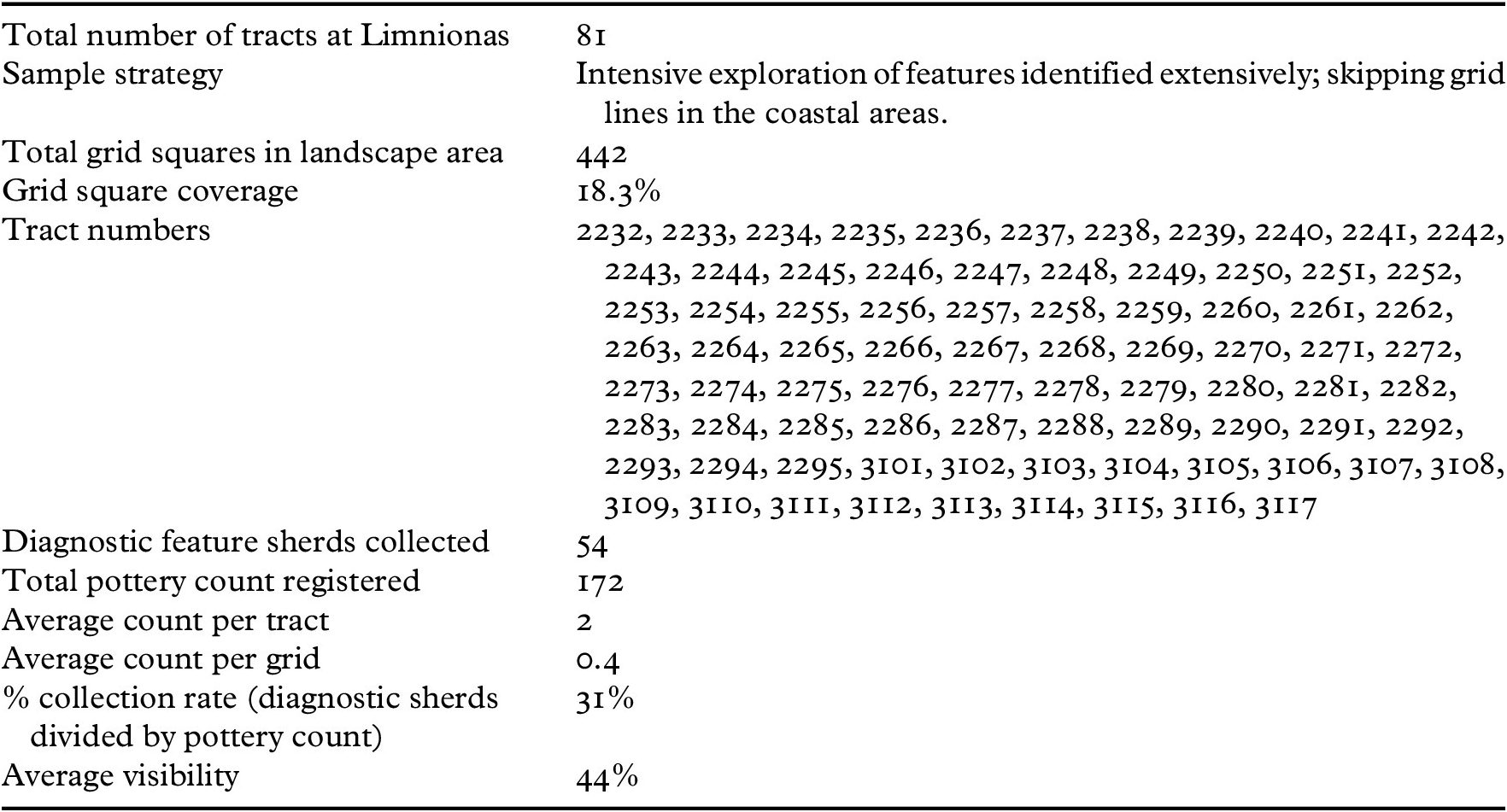

Limnionas

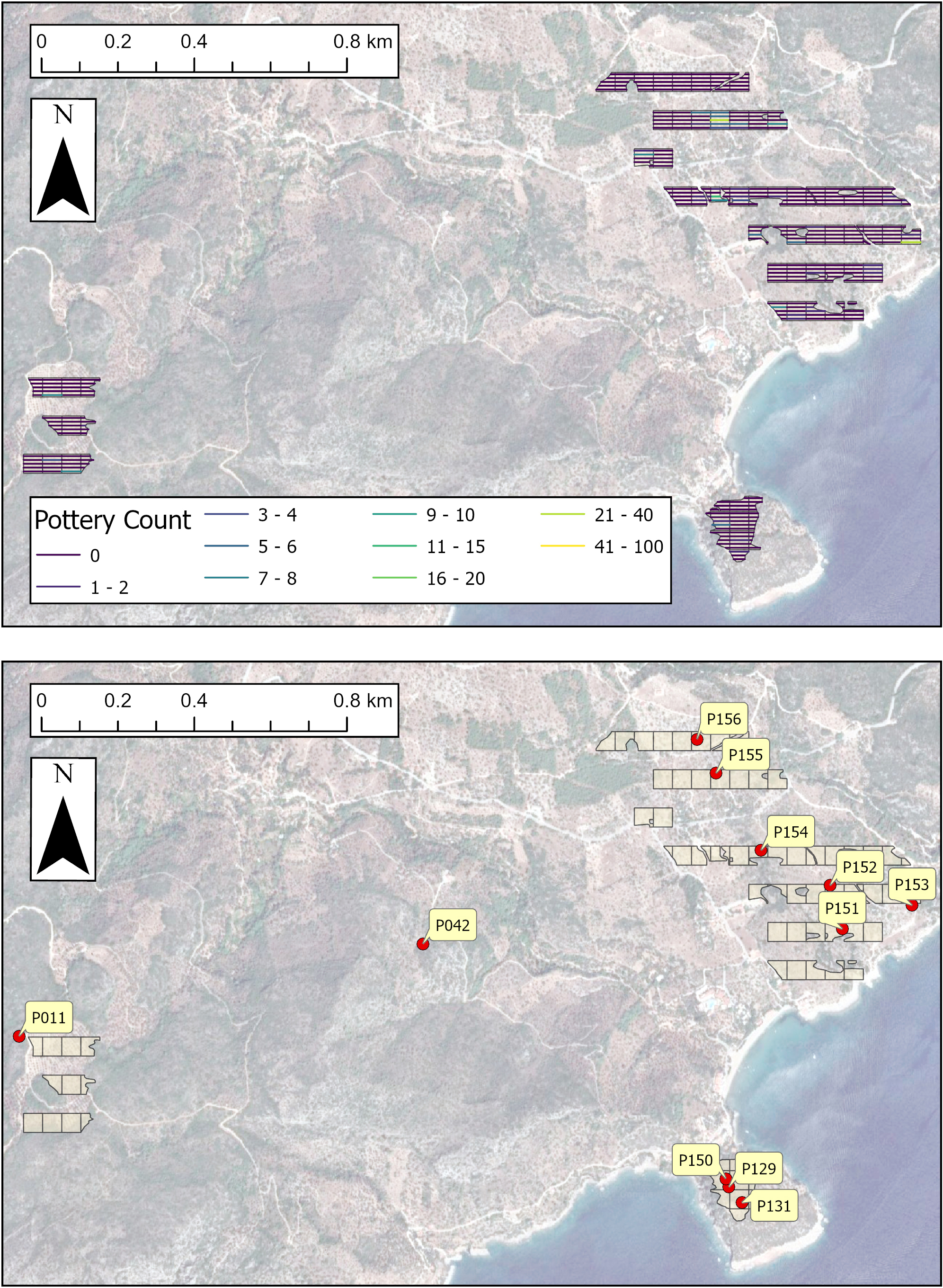

West of Kampos, the coastline rises to high cliffs around the beach of Psili Ammos, and the inland areas present more rugged landscape due to the steep sides of Mt Kerkis. This area was ill-suited for intensive archaeological survey. Further along the coast, the next point that offers a suitable landscape for tract walking is the area around the modern seaside village of Limnionas. West of the village itself are two coastal promontories, Akra Chondros Kavos and Makria Pounta, the forms of which create a natural harbour. The spurs are characterised by medium slopes, thin soils and low-growing fallow and maquis on the inland side, and sheer rock-face on the seaside. Akra Chondros Kavos is steeper, with parts of the hill covered by private olive groves (Fig. 14; Tables 11 and 12). The whole walkable area of Akra Chrondros Kavos was documented through drone photography. See online Supplementary Materials for close zoom maps showing locations of tracts (nos 1–4).

Fig. 14. Above: map of the Limnionas zone, with walkerlines by ceramic count. Below: map with location of tracts and POIs labelled (images by Michael Loy).

Table 11. List of tracts walked in the Limnionas zone

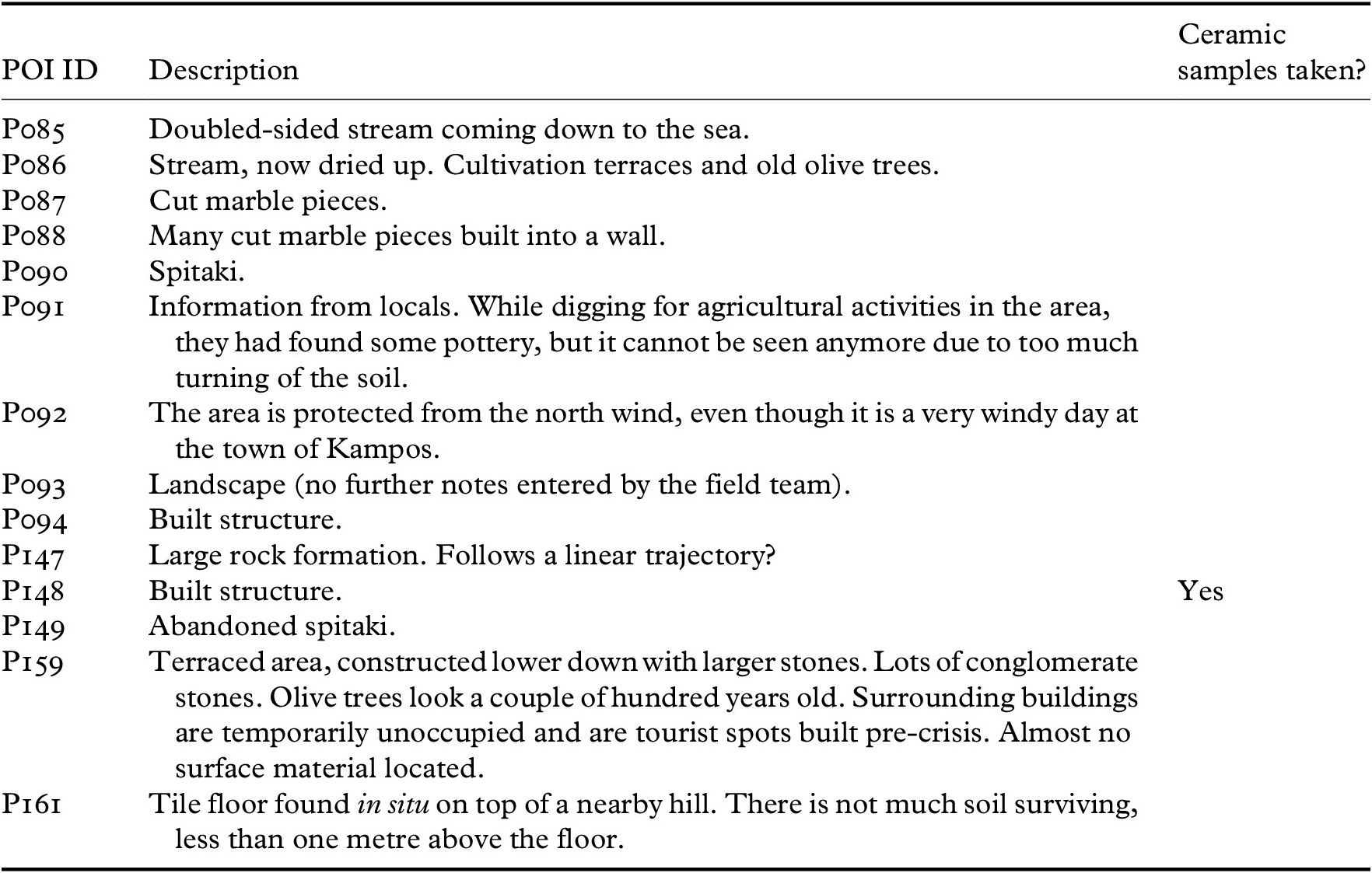

Table 12. List of POIs in the Limnionas zone

This zone was identified in 2021 as being of potential archaeological interest, given the safe anchorage created by the natural landscape formations. The discovery of a small cache of sherds on the promontory of Akra Chondros Kavos (collected in 2022 as the POI P150) further suggested that the zone might potentially yield archaeological remains. This cache was indeed promising, as it included Archaic and Hellenistic sherds as well as Byzantine material.

However, further tract walking on Akra Chondros Kavos in 2022 yielded few further finds, and those that were collected were mostly of Early Byzantine date, although one piece of obsidian perhaps hints at earlier activity at this location (3110-2-1; Fig. 15). It is worth noting that the terrain does not favour the retention of archaeological material – the promontory is steeply sloped, with a thin and eroded soil. In addition, a significant portion of the promontory was inaccessible for tract walking due to being fenced.

Fig. 15. Obsidian flake collected at Limnionas (photograph by Francesca Zandonai).

Exploratory tract walking was done inland, in the area immediately behind the village of Limnionas, from the coast up to the lower slopes of Kerkis. Very little material came from this latter area, but Early Byzantine sherds were collected. Of interest in this area were various walls and rock-cut features (P152–P157). Much further west, a small number of test tracts were walked in extensive exploration to try and identify sites mentioned as part of Shipley’s own extensive explorations. These tests were largely unsuccessful and yielded very small numbers of surface ceramics. Across this zone as a whole, relatively little material was collected (344 sherds counted in total over 172 tracts, resulting in an average count of 2 sherds per tract; see Table 16), with most material being concentrated on the Akra Chondros Kavos promontory.

CERAMICS AND MATERIAL CULTURE by Sabine Huy

This section gives a comprehensive overview of the material culture according to the five main zones in south-west Samos as described above, with the main focus on the ceramic material. A discussion of the assemblage in a local, regional and supra-regional context is the subject of a separate article in this volume (Loy and Huy Reference Loy and Huy2025).

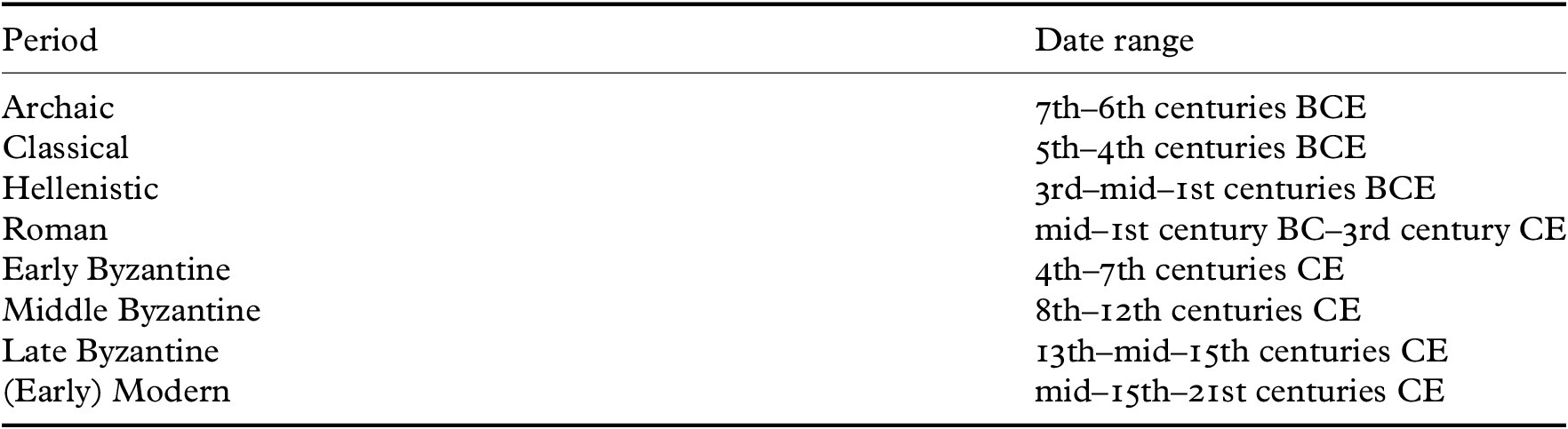

The overview is based on the analysis of all classifiable diagnostic pottery sherds and also includes the few finds of other categories made at the locations listed above (architectural ceramics, stone, glass and metal objects). All have been photographed individually, and a representative sample of the typo-chronological pottery groups has been drawn (334 vessel profiles). The classification of the ceramics was primarily aimed at determining date and vessel function. The dating follows the common historical phases and covers the periods from Archaic to Modern (Table 13).Footnote 7 Where fragments could only be roughly dated, they were simply classified as first millennium BCE or first millennium CE. The vessel function is distinguished according to the following categories: tableware (drinking vessels, food services, pouring and mixing vessels), transport amphorae, household ware (often called ‘plain or common ware’ = large bowls and jugs, beehives), cooking/kitchen ware (cooking pots, pans and jugs made of cooking fabrics) and storage ware (pithoi and large pots). Less than half of the sherds (889 = 44%) are heavily abraded and worn. The general preservation is therefore good for survey material, indicative of exposure to external influences for only a short time. On the plateau south of Koumeiika (P316), some vessels were even found broken into several fragments in one place, proving that they had only recently come to the surface (e.g. P316-23). The majority of the pottery is probably of local Samian provenance, as the main fabric groups identified are ubiquitous in the survey universe and occur in all periods and vessel types. The fabric groups will be introduced in detail in a separate article in this volume (Loy and Huy Reference Loy and Huy2025).

Table 13. Chronology and date ranges used in this article for ceramic classification

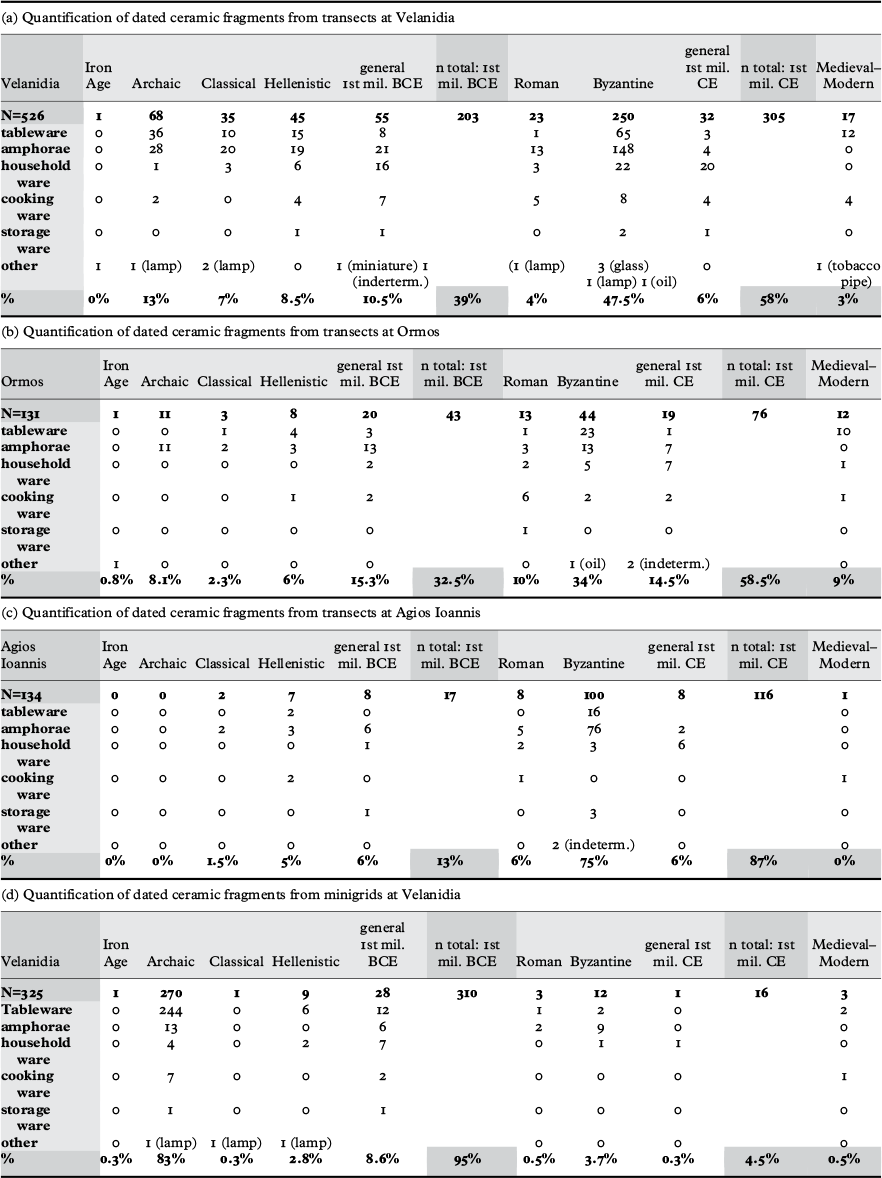

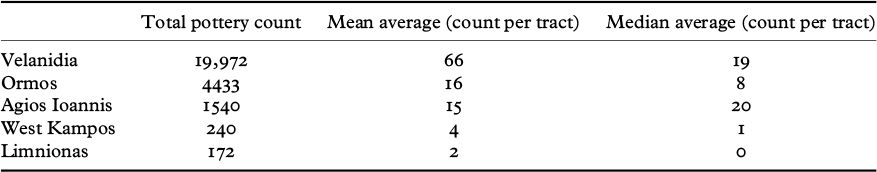

Quantification of ceramics

A total of 2235 ceramic sherds were identified in the field as diagnostic and brought to the museum for further analysis. In the field, not only rim, base, and handle fragments were considered diagnostic, but also wall sherds with decoration/glaze or ribbing.

During analysis at the museum, at a first stage any sherds that had been incorrectly identified as diagnostic were discarded, as were most of the decorated body sherds. This was done because a test counting glazed decorated body sherds of tableware and ribbed/grooved sherds of middle Roman–Early Byzantine vessels provided a noticeable bias for the collection of such highly diagnostic sherds: ribbed body sherds of the Early Byzantine period (242 fragments) far outnumbered in the dataset un-ribbed body sherds dated to other periods (47 fragments). It was therefore decided that their inclusion could skew the analytical statistics and only the few exceptions of body fragments with clear diagnostic information (e.g. biconical fragments of carinated bowls) remained in the analysis. However, in the minigrid collection in the Skoubides area at Velanidia, all sherds (including body fragments) were included in the quantitative and typological analysis, as the gridding methodology aimed to investigate the area to a high resolution.

Other categories of finds were only sporadically encountered, and architectural ceramic was documented on a sample basis. These non-pottery objects are not part of the quantitative analysis, but are listed in the typological overview of each zone.

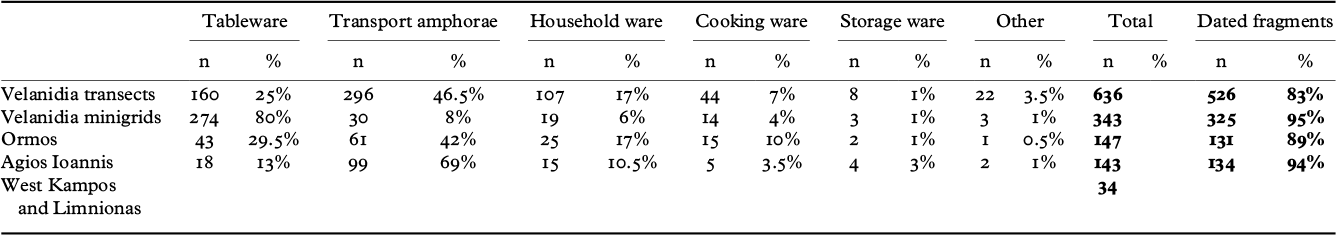

Each of the five main zones was quantified separately. After filtering out all incorrectly identified profiles, non-pottery objects, and wall fragments as described above, 1303 ceramic fragments remained that were suitable for classification into functional groups, distributed among the zones as follows (see also Table 14): Velanidia basin: 636 fragments; Ormos (including the western Velanidia basin): 147 fragments; Agios Ioannis: 143 fragments; West Kampos: 10 fragments; Limnionas: 24 fragments. From the minigrid collection at Skoubides, 343 fragments were analysed. Due to the small amount of pottery from West Kampos and Limnionas, these assemblages are not quantified.

Table 14. Quantification of classified pottery fragments according to functional groups in each survey area

In all areas, tableware and transport amphorae were the main functional groups found, but there are significant differences in the proportions. The findings from the Velanidia tracts and from the Ormos region show similar proportions of 25–30% tableware and 42–46% amphorae, whereas the ratio in Agios Ioannis and from the minigrids in Velanidia deviates significantly. In the case of the latter, tableware accounts for 80% of the assemblage, which correlates with the high proportion of such wares already collected during the tract walking in the Skoubides area in 2022. At Agios Ioannis, however, the very high proportion of amphorae (69%) correlates with the comparatively low proportion of tableware (13%).

A more detailed quantification of the chronological distribution is given in Table 15 (only showing the numbers of datable fragments). The absence of any clearly prehistoric material in the dataset is particularly striking. Again, the assemblages from the tract-walking in Velanidia and Ormos compare well: more than half of the finds date from the first millennium CE and a good third from the first millennium BCE. The long-term use of the areas since the pre-Roman periods is therefore evident. In Agios Ioannis, the picture is different: almost 90% of the dated finds are from the first millennium CE with the majority being from the Early Byzantine period of the fifth–seventh centuries CE.Footnote 8 For the finds from the minigrid campaign in 2024 at Skoubides hill, the dating of 80% of the finds to the Archaic period was expected due to the spatial concentration of Archaic pottery observed already during the tract walking.

Typological overview of the five main survey zones

The 1303 ceramic fragments identified by quantification as suitable for more detailed classification were then dated and sorted by type. The following section provides a representative overview of the individual assemblages from the five main survey areas, summarised in Table 16. The observations are discussed in the following section.

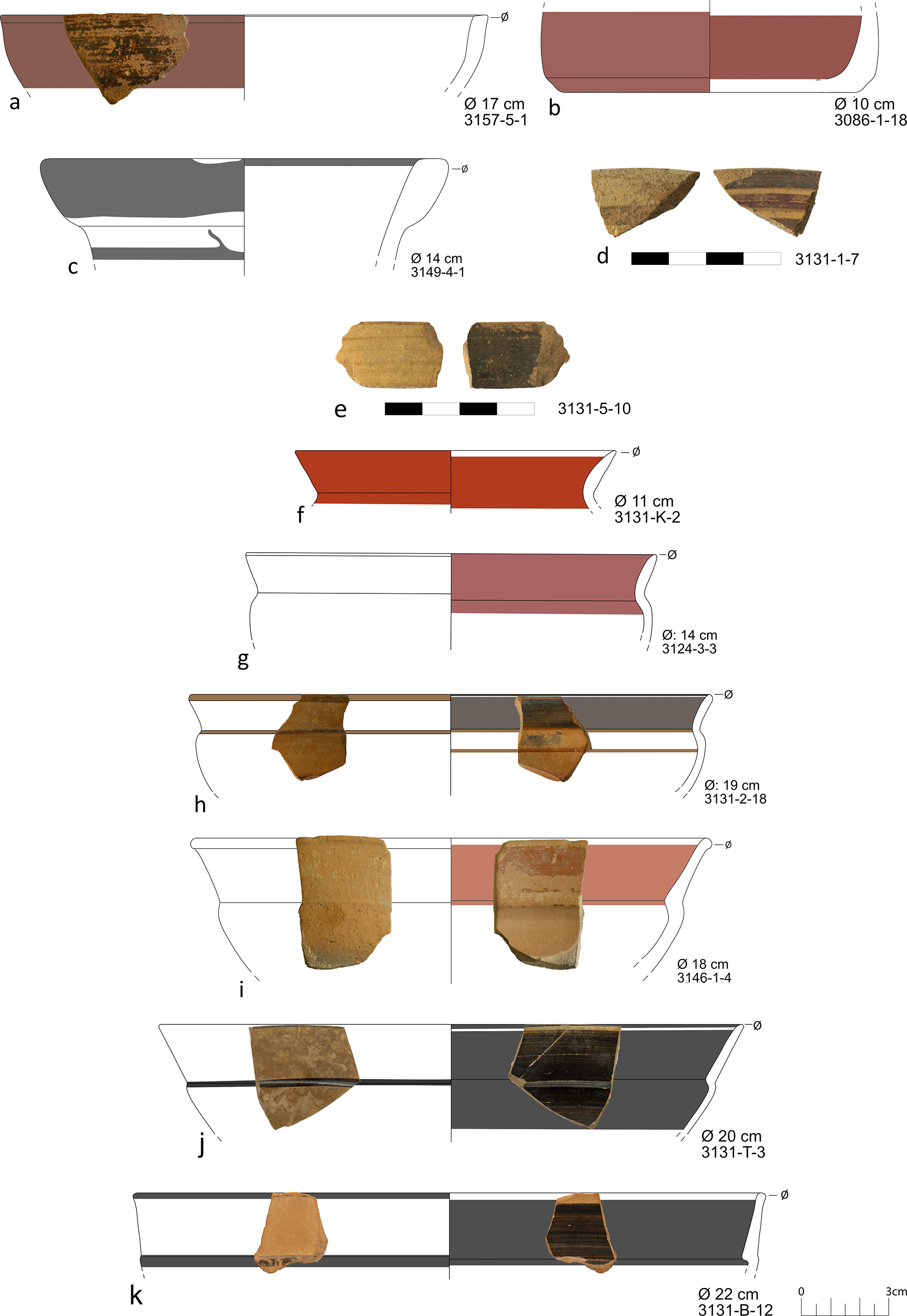

East Velanidia

Archaic material was found mainly on Skoubides hill during tract-walking in 2022 and the minigrid campaign in 2024. The tableware consists primarily of vessels with simple band decoration, a typical ware in Ionia.Footnote 9 Among the shapes are amphorae, jugs, plates, mugs, and, above all, the so-called Ionian bowls or cups with everted rim (German: Knickrandschalen; total 67 fragments) (Fig. 16). These are exemplified by various types (mainly types 5, 6 and 9 according to Schlotzhauer Reference Schlotzhauer2014) and cover the period between the second half of the seventh and the late sixth century BCE. The delicate vessels of type 9 are the best represented among the cups (Fig. 16h –k). Since there are close connections in form, decoration and even fabrics between the Ionian cups of type 9,3 and 9,4 and Attic bowls with everted rims (Schlotzhauer Reference Schlotzhauer2014, 107, 332–4), the origin of vessels such as 3131-2-18 (‘Class of Athens 1104’, second quarter/late sixth century BCE; cf. Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 88–9, fig. 4, pls 18–19) or 3131-T-3 and 3131-B-12 (Schlotzhauer Reference Schlotzhauer2014, 107–8, type 9,4.C) cannot be determined with certainty.

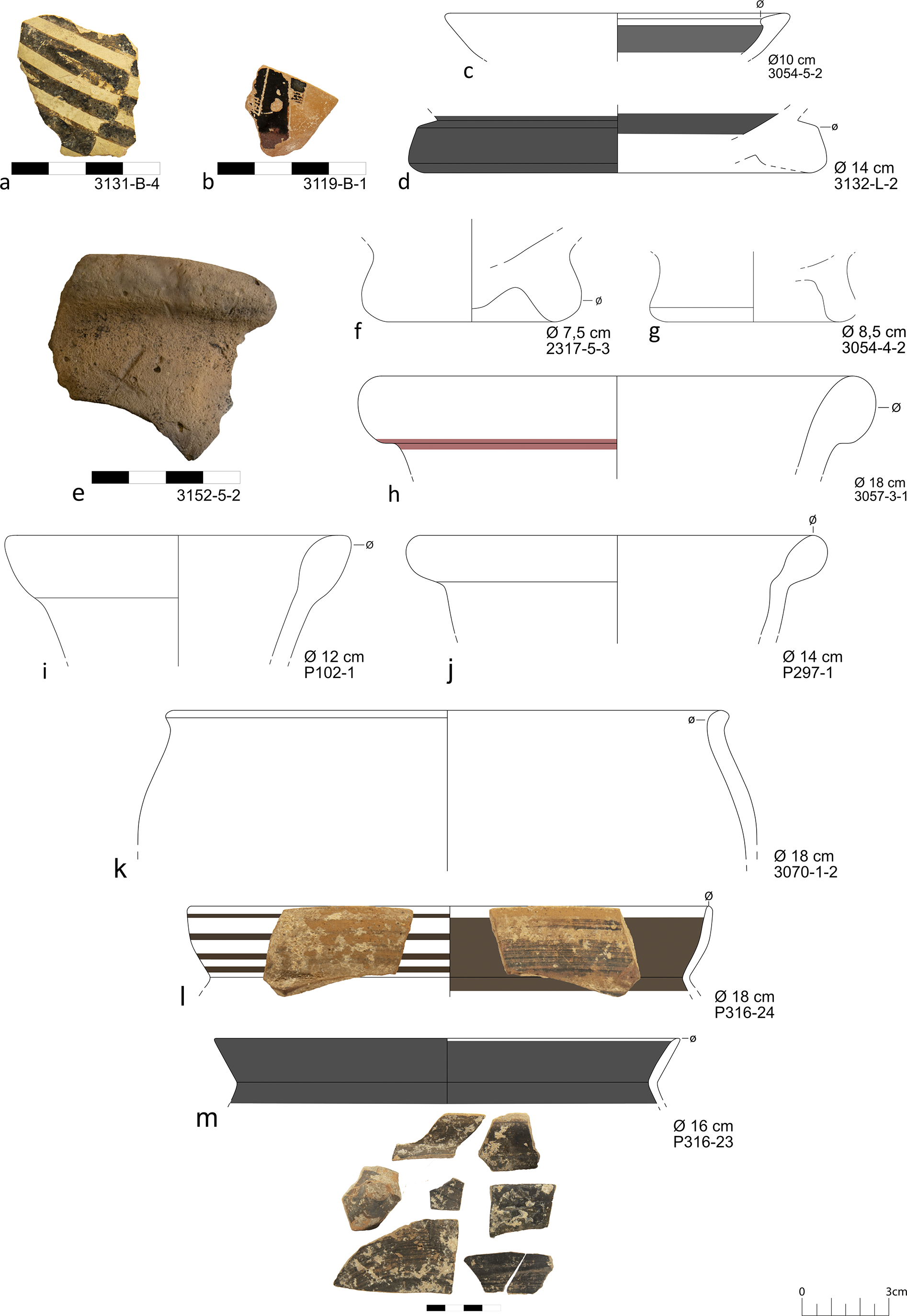

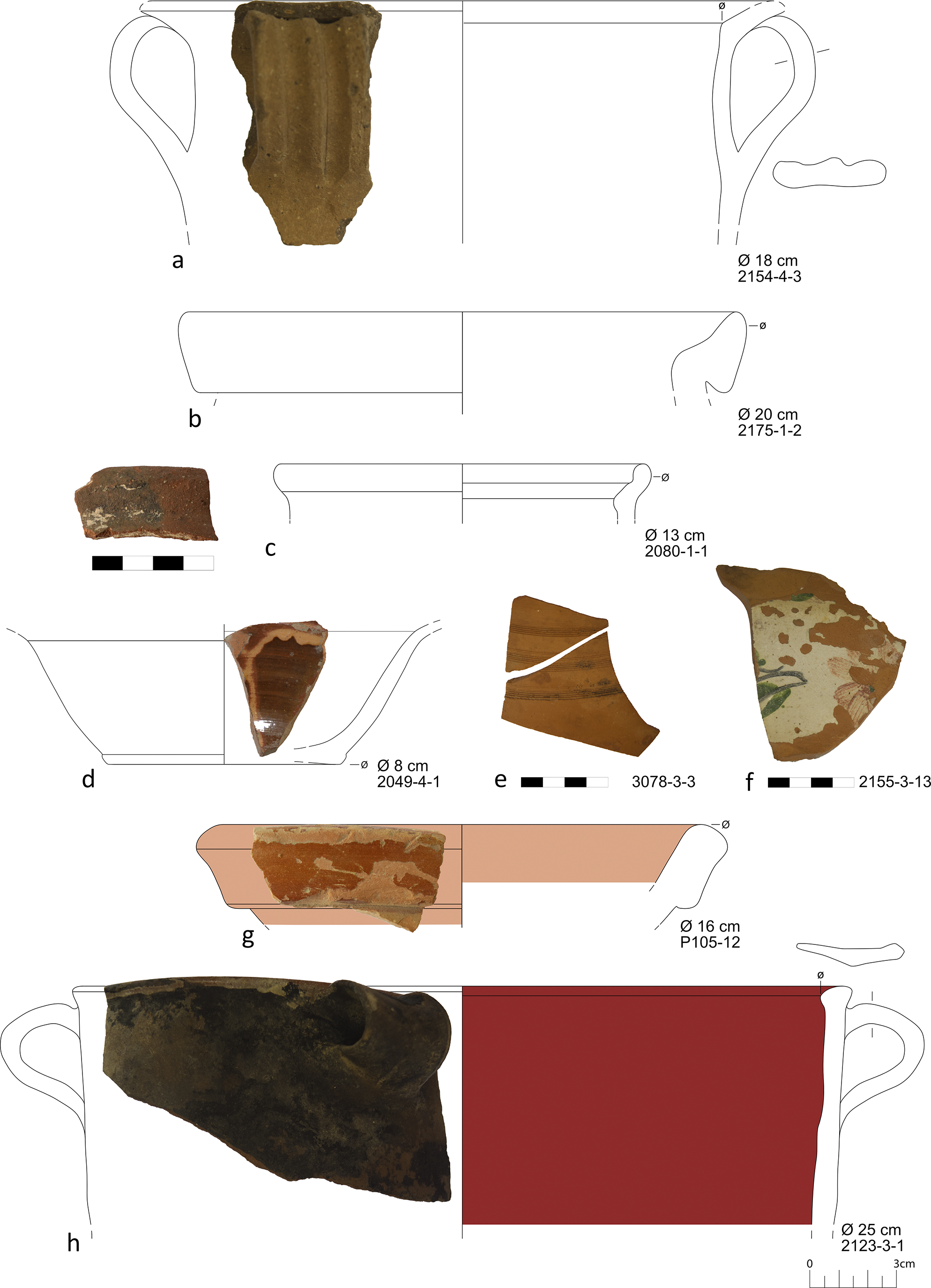

Fig. 16. Ceramics from Velanidia (Skoubides hill). Archaic period: Ionian tableware (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

A few sherds of finewares such as Fikellura (3131-B-4; Fig. 17a; cf. Walter-Karydi Reference Walter-Karydi1973, 3–4, nos 47, 54, 57, pls 4–5: mid–third quarter of the sixth century BCE) and Attic black-figure (3119-B-1; Fig. 17b; mid-sixth century BCE)Footnote 10 have been found at Skoubides hill. Attic black-glazed ware is represented by some one-handlers (e.g. 3054-5-2; Fig. 17c; cf. Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 124–6, nos 724–57, fig. 8; 520–500 BCE), a cup-skyphos (3131-L-2; Fig. 17d; cf. Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 109–10, nos 573–8, fig. 6; 490–80 BCE), and fragments of type C kylikes of the late Archaic period (cf. Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, 91–2, nos 398–431, fig. 4).

Fig. 17. Ceramics from Velanidia (Skoubides hill and the hills to the east). Archaic period (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

The Archaic amphorae are almost all of the South Ionian ‘Samian-Milesian’ type, of which the ‘Samian’ variant with a bulging thick rim (e.g. 3152-5-2, 3057-3-1, P297-1, 2317-5-3, 3054-4-2; Fig. 17e –h j ) was found somewhat more frequently than the ‘Milesian’ variant with a narrow oval rim (e.g. P102-1; Fig. 17i).Footnote 11 As numerous studies have shown, these types of amphorae were not produced exclusively in Samos or Miletus, but in many different places in southern Ionia and Caria (see for example Kerschner and Mommsen Reference Kerschner, Mommsen, Brandt, Gassner and Ladstätter2005, 126, n. 40; Greene, Lawall and Polzer Reference Greene, Lawall and Polzer2008, 688–90). One of the fragments shows an χ-shaped graffito, a typical commercial sign carved after firing (3152-5-2; Fig. 17e).

Archaic household and kitchen ware is represented by lekanides and some rims of jugs and cooking pots (e.g. 3070-1-2; Fig. 17k; cf. Archaic contexts in Ephesus [von Miller Reference Miller2019, 61, nos 338–9, pl. 32, 70, nos 395–7, pl. 38] and in Didyma [von Miller Reference Miller and Bumke2023b, 361–2]).

In addition to ceramic vessels, there are some fragments of painted roof tiles, perhaps datable to the Archaic period, some with broken edges of antefixes, indicative of a possible representative architectural structures. Of special interest is the Egyptian Blue faience scarab (Fig. 6).Footnote 12

A second, much smaller concentration of Archaic pottery was found a good way south-east of the village of Koumeiika at the POI P316. The types compare well with the assemblage from Skoubides hill. Along with an amphora rim of the Samian-Milesian type, a fragment of a cooking pot such as 3070-1-2 (Fig. 17k), and a krater of the mastoid type, which was found in 18 pieces (P316-7.18; Fig. 18a; cf. von Miller Reference Miller2019, 65, no. 363, pl. 34, 106, no. 623, pl. 55), there are a few cups with everted rim (only types 5 and 6 according to Schlotzhauer Reference Schlotzhauer2014; e.g. P316-24, P316-23; Fig. 17lm). A sherd of a hand-formed vessel (P316-9; Fig. 18b) and some stone tools (e.g. P316-13, P316-2, P316-14, P316-15, P316-16A. B; Fig. 9)Footnote 13 point to possible activity in Late Neolithic–Early Bronze Age periods at the site.

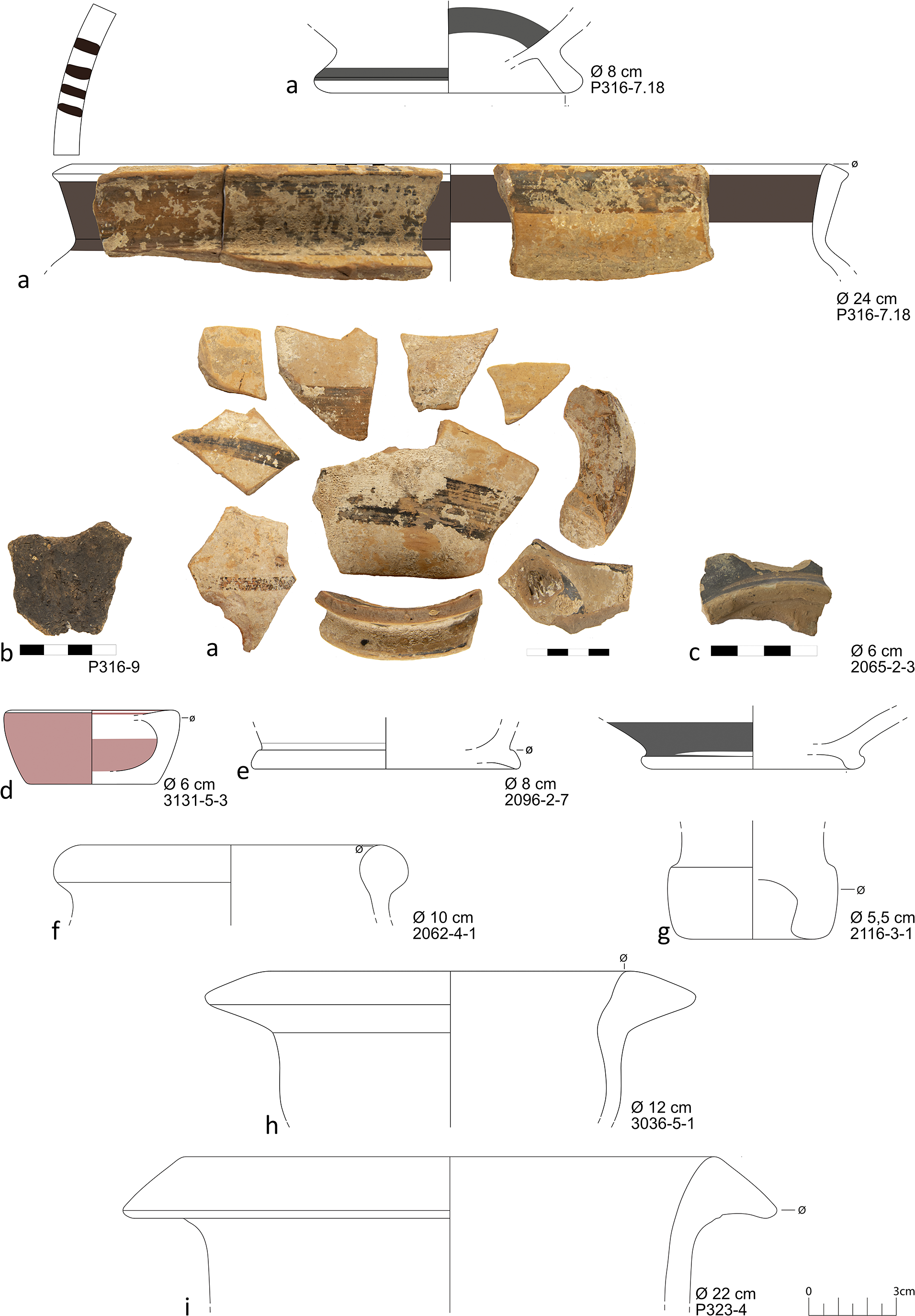

Fig. 18. Ceramics from Velanidia. Archaic–Classical periods (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

The post-Archaic findings come mostly from the other areas in the Velanidia. The few finds from the Classical period date almost all from the second half of the fifth and the fourth centuries BCE, including local black-glazed ware (2096-2-7, 2065-2-3; Fig. 18ce), three lamps of type Broneer VI (e.g. 3131-5-3; Fig. 18d; cf. Bookidis and Pemberton Reference Bookidis and Pemberton2015, 63–4, nos L92, L93, pl. 10) and amphorae. From the first half of the fifth century BCE only the rim of a swollen-neck type amphora from Chios has survived (2062-4-1; Fig. 18f; cf. Monakhov Reference Monakhov2003, 17–19, type III-B, pl. 5). Another slightly later Chian amphora is preserved as base 2116-3-1 (Fig. 18g; cf. Monakhov Reference Monakhov2003, 19–20, type IV-A, pl. 8:1–2). Other amphorae belong to the mushroom-rim type, which was produced by a lot of poleis in Ionia and the wider south-east Aegean region especially in the fourth century BCE (e.g. 3036-5-1, P323-4; Fig. 18hi). In Ephesos, Miletus, and Samos this type continued into the Hellenistic period, and some fragments from the survey show typological features dating to the third century BCE (e.g. 2178-3-4, 2052-5-17; Fig. 19ab; cf. Lawall Reference Lawall, Eiring and Lund2004). Other Hellenistic amphorae are of the Ionian and Rhodian types with small beaded rims (e.g. 2175-5-1, 2048-2-2; Fig. 19cd).

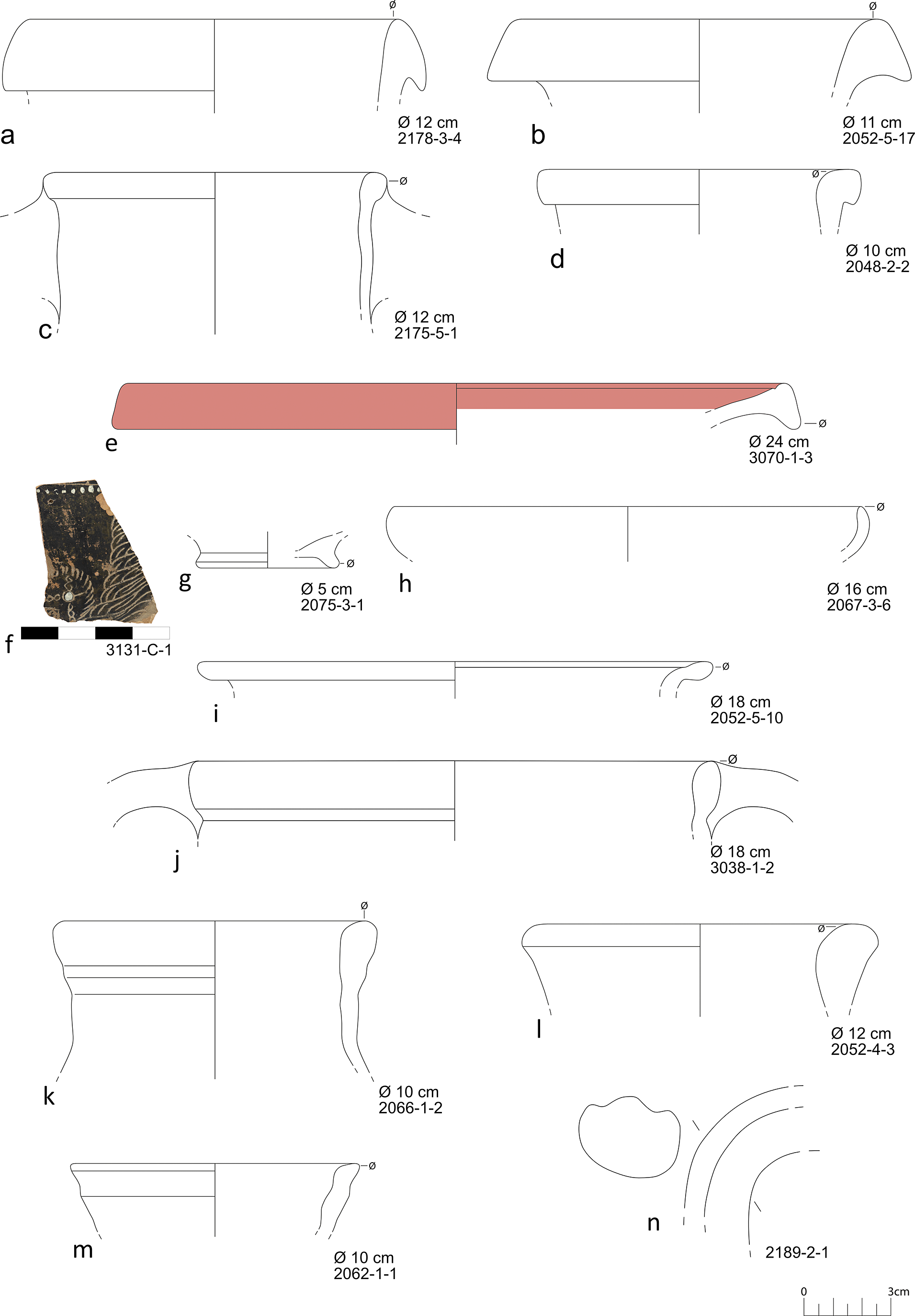

Fig. 19. Ceramics from Velanidia. Hellenistic–Early Byzantine periods (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

Sherds of Hellenistic table, household and cooking wares cover the usual range of shapes typical of the period. Tableware consists mainly of colour-coated bowls, fish plates, and Knidian carinated cups (e.g. 3070-1-3, 2075-3-1, 2067-3-6; Fig. 19egh; for a summary of these types in Attic black-glazed ware, cf. Rotroff Reference Rotroff1997, 146–9, 156–69; in Ionian colour-coated ware, cf. Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 58–79, 147–58; in Knidian grey ware, cf. Rotroff Reference Rotroff1997, 233–4; Kögler Reference Kögler, Bilde and Lawall2014). From Skoubides hill comes the peculiar piece of a large closed vessel (an amphora?) in the late Hellenistic Westabhang-Nachfolgestil (West Slope Successor Style) with the incised depiction of a winged horse (3131-C-1; Fig. 19f). This style developed from the mid-second century BCE and on Samos it was particularly popular in the late second to early first century BCE (cf. Tölle-Kastenbein Reference Tölle-Kastenbein1974, 153; Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 41). Among the Hellenistic vessels are some household jugs (cf. Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 73–7, Hellenistic jugs forms 1 and 2) and cooking pots (e.g. 2052-5-10, 3038-1-2; Fig.19ij; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 322, no. 1879, pl. 86 = cisterne 2, Hellenistic filling and Rotroff Reference Rotroff2006, 177, chytra form 10).

In the Roman period, there is a noticeable gap in the finds sequence. Sigillatas have not survived at all, which, given their shiny red coatings, can hardly be attributed to a visibility bias in the survey. Roman amphorae appear sporadically at Velanidia, as isolated fragments of various types (e.g. 2066-1-2: cup-shaped rim type; Fig. 19k; 2176-3-4: Dressel 2-4; 2203-2-1: Dressel 24; 2189-2-1: Kapitän II; Fig. 19n; 2052-4-3: Africana III; Fig. 19l). They were found together with some Roman household ware and cooking pots (e.g. 2062-1-1; Fig. 19m; cf. Pülz Reference Pülz1987, 43, no. 47, fig. 16).

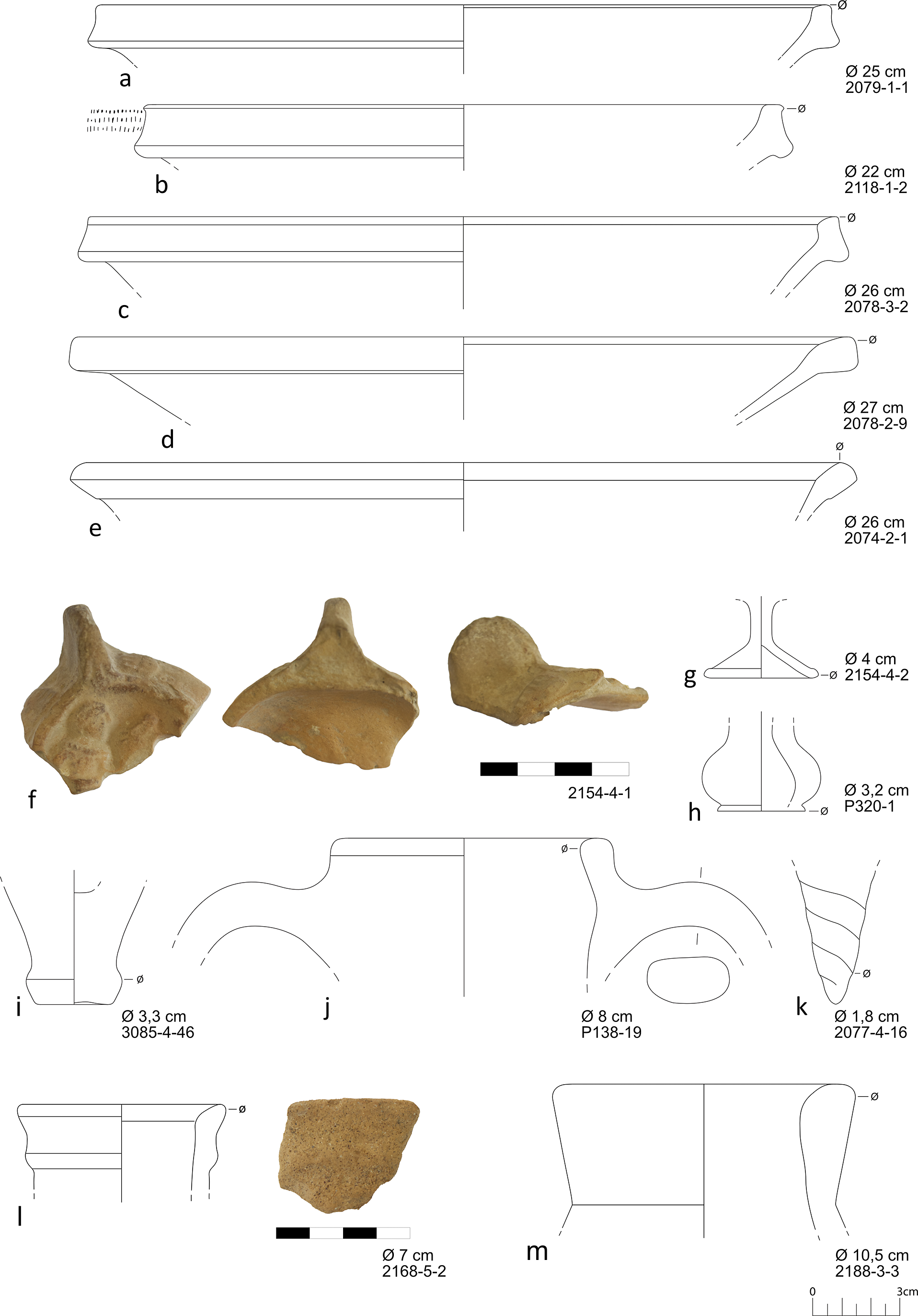

The density of finds increases significantly in the Late Roman/Early Byzantine period. The tableware of the fifth to seventh centuries CE consists of dishes of the Phocean Red Slip ware, mainly Hayes Late Roman C (= LRC) forms 3 and 10 (e.g. 2079-1-1, 2118-1-2, 2078-3-2, 2078-2-9, 2074-2-1; Fig. 20a–e). Fragments of glass chalices (2154-4-2, 2154-4-10; Fig. 20g; cf. Isler Reference Isler1969, 226–8, figs 59–61; Megow Reference Megow and Jantzen2004, 67–73, nos 425–501, Beil. 12, pl. 12) as well as one lamp of the Asia Minor group date from the same period (2154-4-1; Fig. 20f; cf. Fırat Reference Fırat2016, 130, no. 7, fig. 9). Notable is a small but massive base of a glass vessel (P320-1; Fig. 20h). The light purple material is rare in Ionia and mainly known from Mesopotamia (cf. Czurda-Ruth Reference Czurda-Ruth2007, 181, no. 810, pl. 36).

Fig. 20. Finds from Velanidia. Early Byzantine period (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

Early Byzantine amphorae are dominated by the regional type Agora M 273 and the Samos Cistern type (e.g. 3085-4-46, P138-19, 2077-4-16; Fig. 20i–k), which were produced in Samos and on the opposite mainland (Arthur Reference Arthur1990). The types are closely related and in the case of fragmented material cannot always be distinguished with certainty. Agora M 273 (a.k.a. Ephesos 50, Opait C III-1) is the older type, dating from the second half of the third to the end of the fifth centuries CE. The Samos Cistern type (a.k.a. Ephesos 51; eponymous context: Isler Reference Isler1969) was produced from the sixth to seventh centuries CE. In addition to these local amphorae, there are several other types, such as Late Roman Amphorae (= LRA) 1 from Cilicia (e.g. 2168-5-2; Fig. 20l) and LRA 2 (e.g. 2188-3-3; Fig. 20m), and Aegean Globular Amphorae (a.k.a LRA 5/6, LRA 13; e.g. 3085-4-4) from the Ionian region. Several fragments of large pithoi (e.g. 2081-3-1) and cooking pots also date from the fifth to seventh centuries CE (e.g. 2154-4-3; Fig. 21a; cf. Schneider Reference Schneider1929, 128, no. 10, fig. 21:2; Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 242, no. 1486, pl. 55; context: seventh century CE; 2175-7-2; Fig. 21b; cf. Akrivopoulou and Slampeas Reference Akrivopoulou, Slampeas, Poulou-Papadimitriou, Nodarou and Kilikoglou2014, 290; context: seventh century CE; 2080-1-1; Fig. 21c; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 240–1, nos 1470–9, pl. 54; context: seventh century CE).

Fig. 21. Ceramics from Velanidia. Early Byzantine–Early Modern periods (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

No fragment from Velanidia can be assigned with certainty to the Middle Byzantine period. Green or brown monochrome lead glazed ware with white slip probably dates from the Late Byzantine period (e.g. 2049-4-1; Fig. 21d; cf. Böhlendorf-Arslan Reference Böhlendorf-Arslan2008, 381–2; Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 150–1). The unglazed comb incised ware like the jug 3078-3-3 (Fig. 21e) cannot be dated exactly, but represents a kind of decoration common between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries CE (cf. Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 176–7; Laflı and Kan Şahin Reference Laflı and Kan Şahin2015, 74–5; Kaercher Reference Kaercher2022, 245). The fragment of a bowl with a flanged rim in the style of polychrome painted maiolica (2155-3-13; Fig. 21f; cf. Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 166–7) and the mouthpiece of a tobacco pipe (3163-3-1; cf. Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 172–5) point to the Early Modern period (seventeenth to early twentieth centuries CE).

Cooking vessels with a glossy red glaze on the inside are numerous (cf. Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 190–3; Kyriakopoulos Reference Kyriakopoulos, Spataro and Villing2015). The so-called tsoukali (e.g. 2123-3-1; Fig. 21h) are round pots with steep walls and two loop handles just below the rim, which were used in large parts of the Aegean between about 1700 and 1950. Siphnos was a famous centre of production, but bowls like P105-12 (Fig. 21g) were certainly also produced on Samos, where they were even given their own name – tsoukalogavatha (literally tsoukali bowl; Kyriakopoulos Reference Kyriakopoulos, Spataro and Villing2015, 257). They were common in Samian households until the middle of the twentieth century CE and could serve many different functions.

Ormos (including the western Velanidia basin)

In Ormos the finds from the pre-Roman phases are few. A single sherd of a hand-formed vessel even dates to the Early Iron Age (2362-4-1). Archaic to Hellenistic pottery is nearby exclusively represented by amphorae of the same types as described for Velanidia: the Samian-Milesian type (e.g. 3214-1-2, 2317-5-3; Fig. 22ab), the mushroom rim type (e.g. 3208-4-2; Fig. 22c) and the South Aegean type with bead rim. Tableware that predates the Early Byzantine phase comprises the base of an Attic skyphos and a couple of Hellenistic vessels, including a fish plate, a Knidian carinated cup and a pyxis (3215-1-7, 3215-1-8; Fig. 22d; cf. Sparkes and Talcott Reference Sparkes and Talcott1970, nos 1309, 1312, fig. 11; Rotroff Reference Rotroff1997, nos 1247–9, fig. 77).

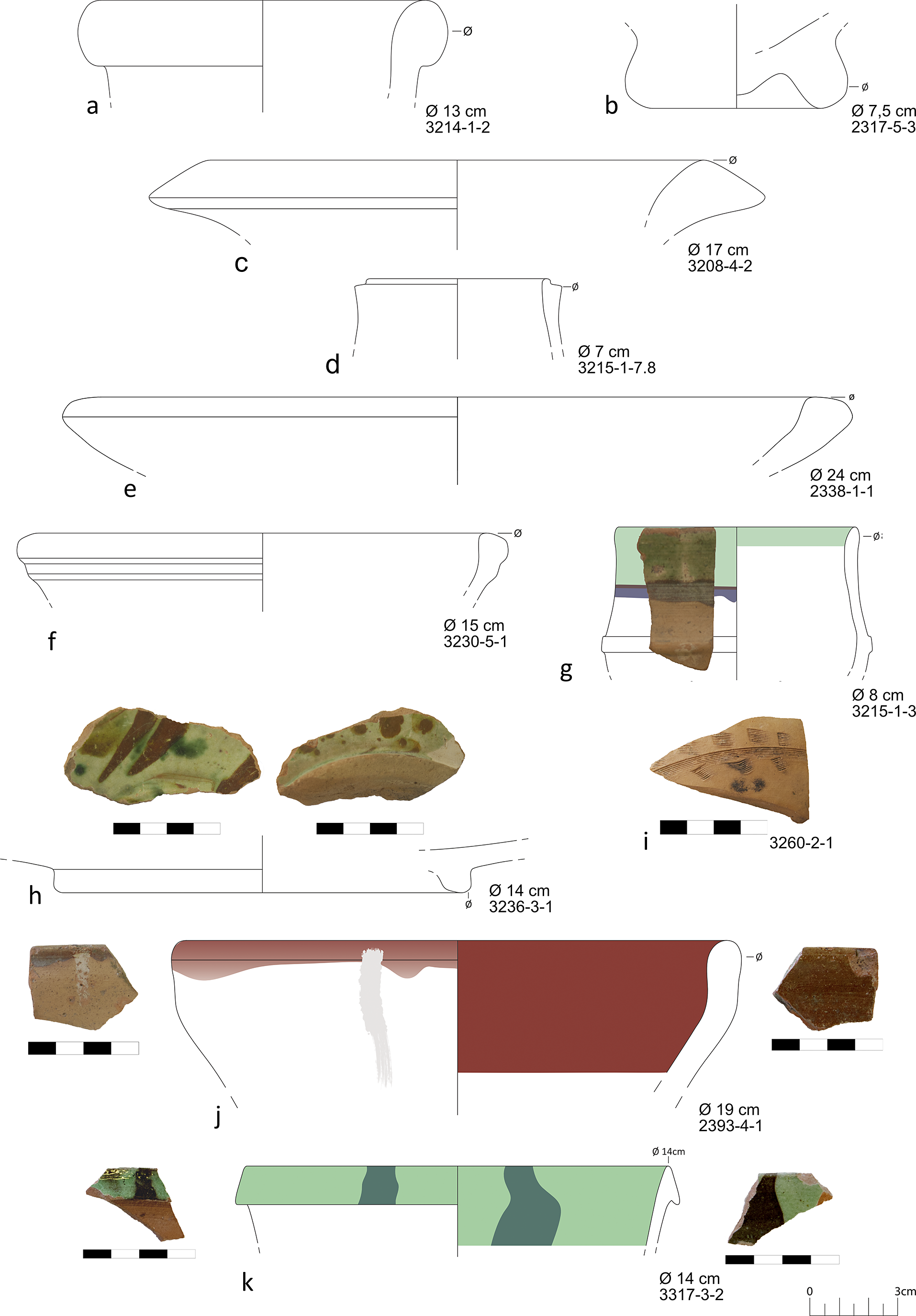

Fig. 22. Ceramics from Ormos. Archaic–Early Modern periods (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

In the Roman period, the range of vessel functions includes also some fragments of household, cooking and storage wares that are typical in Ionian settlements of the Early to Middle Imperial times (e.g. the rim of a pan [2338-1-1; Fig. 22e], flat bases of thin-walled chytrai, and the fragment of a biconical lopas [cf. Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 94–5, pl. 59]). Two amphora handles can be attributed to imported vessels of the types Dressel 2–4 (3204-5-2) and Agora M 54 (3273-1-1).

As in Velanidia, the number of finds increased in the Early Byzantine period. The tableware consists of the Phocaean Red Slip plates (LRC Hayes forms 3 and 10), while amphorae are of the Ionian types Agora M 273 and Samos Cistern. In addition, the rim of a bowl of Cypriot Red Slip ware (3230-5-1; Fig. 22f; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 255, no. 1560, pl. 61), two rims of household ware and wall fragments of storage vessels were found.

Single fragments of amphorae and various glazed table vessels indicate a date late into the Byzantine period (3215-1-3; Fig. 22g; 3236-3-1; Fig. 22h; cf. Green and Brown painted ware). As in Velanidia, some fragments of comb incised ware were found (e.g. 3260-2-1; Fig. 22i), as well as a fairly large number of Early Modern vessels with a glossy red glaze (e.g. 2393-4-1; Fig. 22j) and the rim of a porcelain-like plate (3219-2-1). Modern cooking ware is also represented in the bowl with hooked rim and slip-painting with a vitreous greenish glaze, probably from Thrace or north-western Turkey (3317-3-2; Fig. 22k; cf. Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 186–7).

There are some special finds from Ormos: the wall fragment of a hand-formed vessel probably dates from the Early Iron Age (2362-4-1). Apart from vessels, some fragments of water pipes (e.g. 3262-2-3; cf. Laflı and Kan Şahin Reference Laflı and Kan Şahin2015, 126–7, nos 264–5, pl. 19), two pieces of mother-of-pearl (3228-4-3) and a very light piece of charcoal with many iron and sand inclusions, possibly a kind of slag (2320-1-1), were found.

Agios Ioannis

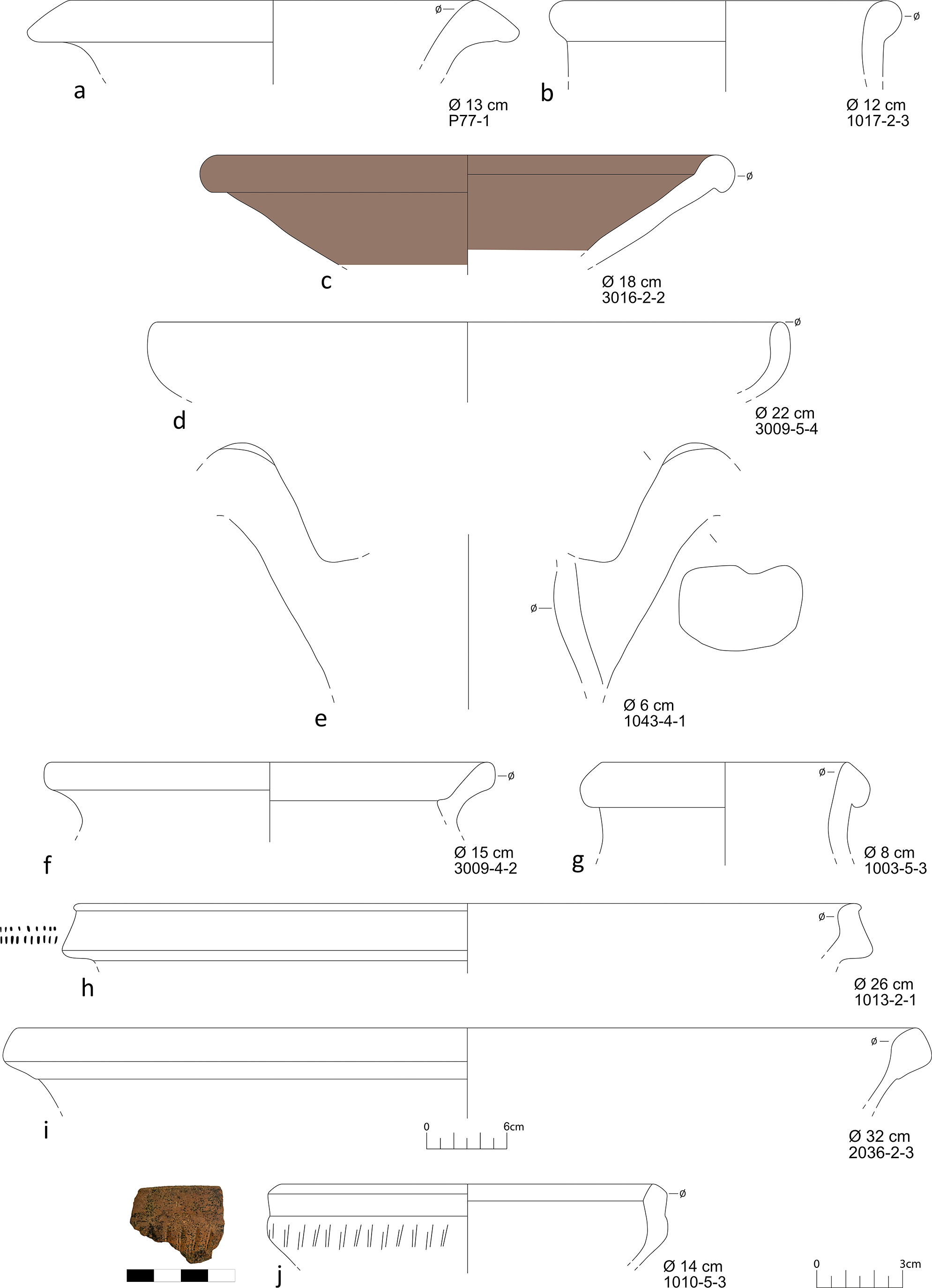

From the area around the church of Agios Ioannis there are very few finds that can be dated before the Early Byzantine period. The very oldest fragment comes from a mushroom-rim amphora from the fourth century BCE (P77-1; Fig. 23a); from the Hellenistic period there are isolated fragments of South Aegean amphorae (e.g. 1017-2-3; Fig. 23b), a fragment of a plate and a bowl of colour-coated ware (3016-2-2, 3009-5-4; Fig. 23cd) and the rim of a cooking pot of the same type as 3038-1-2 (Fig. 19j) from Velanidia. Several amphorae of types Dressel 2–4 (1002-5-7), Dressel 5 (1043-4-1; Fig. 23e) and Kapitän II (2036-1-4, 3024-1-3) can be attributed to the Roman period, as well as the rim of a jug (1003-5-3; Fig. 23g) and cooking vessels (e.g. 3009-4-2; Fig. 23f; cf. Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 170, 418, nos B312–13, pl. 95; 1011-5-1; cf. Fenn Reference Fenn2016, 172, 423, nos B340–1, pl. 99).

Fig. 23. Ceramics from Agios Ioannis. Archaic–Early Byzantine periods (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

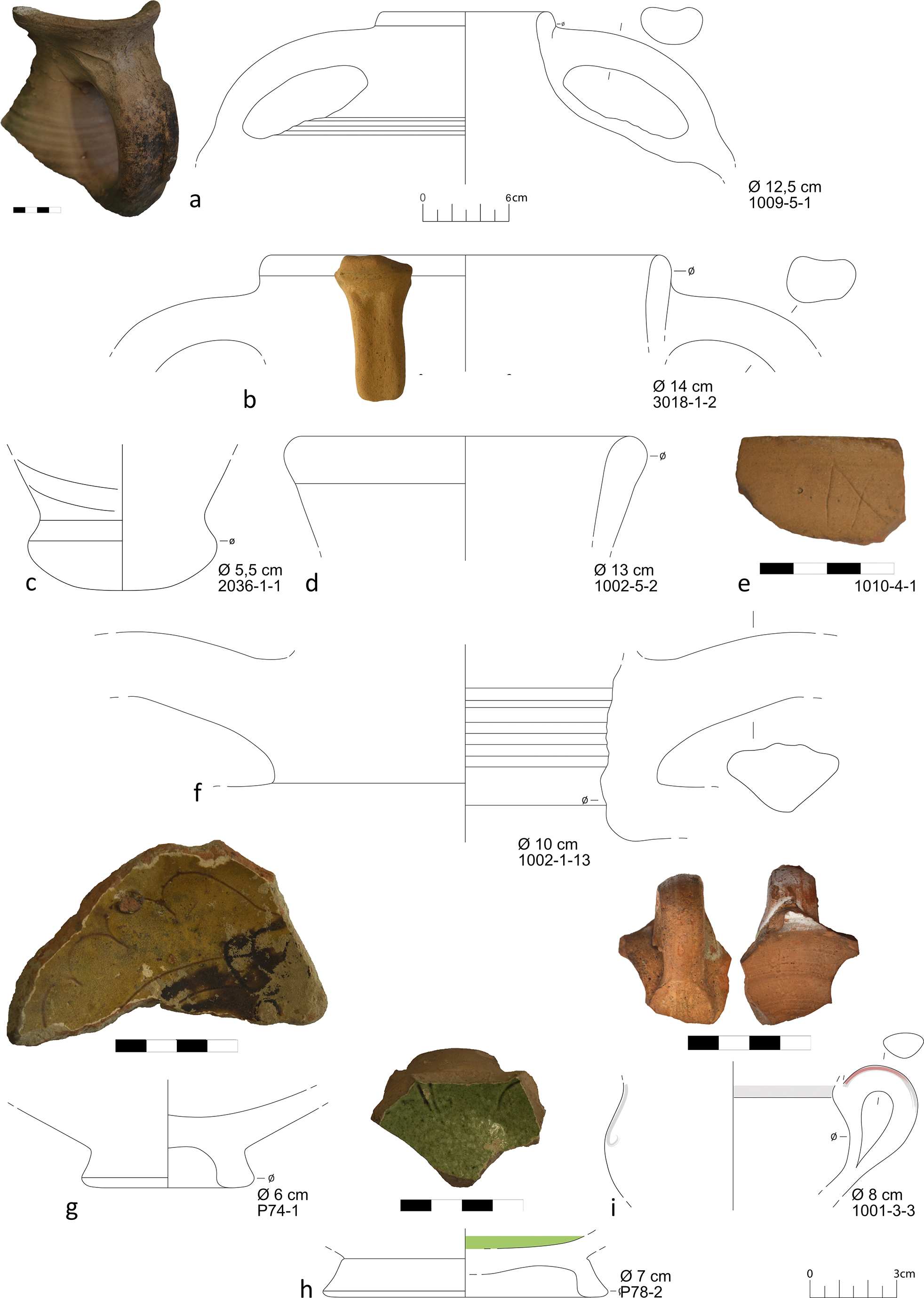

The majority of the finds date from the fifth to the seventh centuries CE, and the assemblage resembles those from other areas of the survey universe. The tableware consists mainly of plates of Phocaean Red Slip ware (LRC Hayes forms 3 and 10; e.g. 1013-2-1, 2036-2-3; Fig. 23hi) and a bowl of Cypriot Red Slip ware (1010-5-3; Fig. 23j; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 257, no. 1570, pl. 62). The amphorae are almost all regional and mostly belong to the Agora M 273 and Samos Cistern types (e.g. 1009-5-1, 3018-1-2; Fig. 24ab). In addition, some fragments of the wider Ionian region and Aegean were found: two bases are comparable to type Ephesos 56 but with typical South Ionian/Samian fabrics (P77-8, 2036-1-1; Fig. 24c; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 225, no. 1391, pl. 48; context seventh century CE), some fragments of LRA 2 (e.g. 1002-5-2; Fig. 24d) and Aegean globular amphorae (e.g. 1002-1-13; Fig. 24f). Evidence of long-distance imports can only be found in a few examples in LRA 1 from Cilicia (e.g. 2037-5-1). Worthy of note is the rim of a jug with the graffito Iχ, probably of Early Byzantine date (1010-4-1; Fig. 24e).

Fig. 24. Ceramics from Agios Ioannis. Early Byzantine–Early Modern periods (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

Tableware of a later date is rather rare, but pieces identified include a fragment of comb incised ware (3021-3-2) and two fragments of late thirteenth to fifteenth century CE sgraffito ware (P78-2, P74-1; Fig. 24gh). The latter seems to be rather late in date due to the thickness of the body and the thick white slip (cf. Böhlendorf-Arslan Reference Böhlendorf-Arslan2008, 381). The Early Modern phase is represented by the rim of a tsoukali (3009-4-2) and the fragment of a red-and-white painted mug (1001-3-3; Fig. 24i). The shape of the mug is also known from Early Byzantine times (Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 267–8, nos 1633–8, pl. 68), but the glaze compares better to the Early Modern vessels such as 2393-4-1 (Fig. 22j).

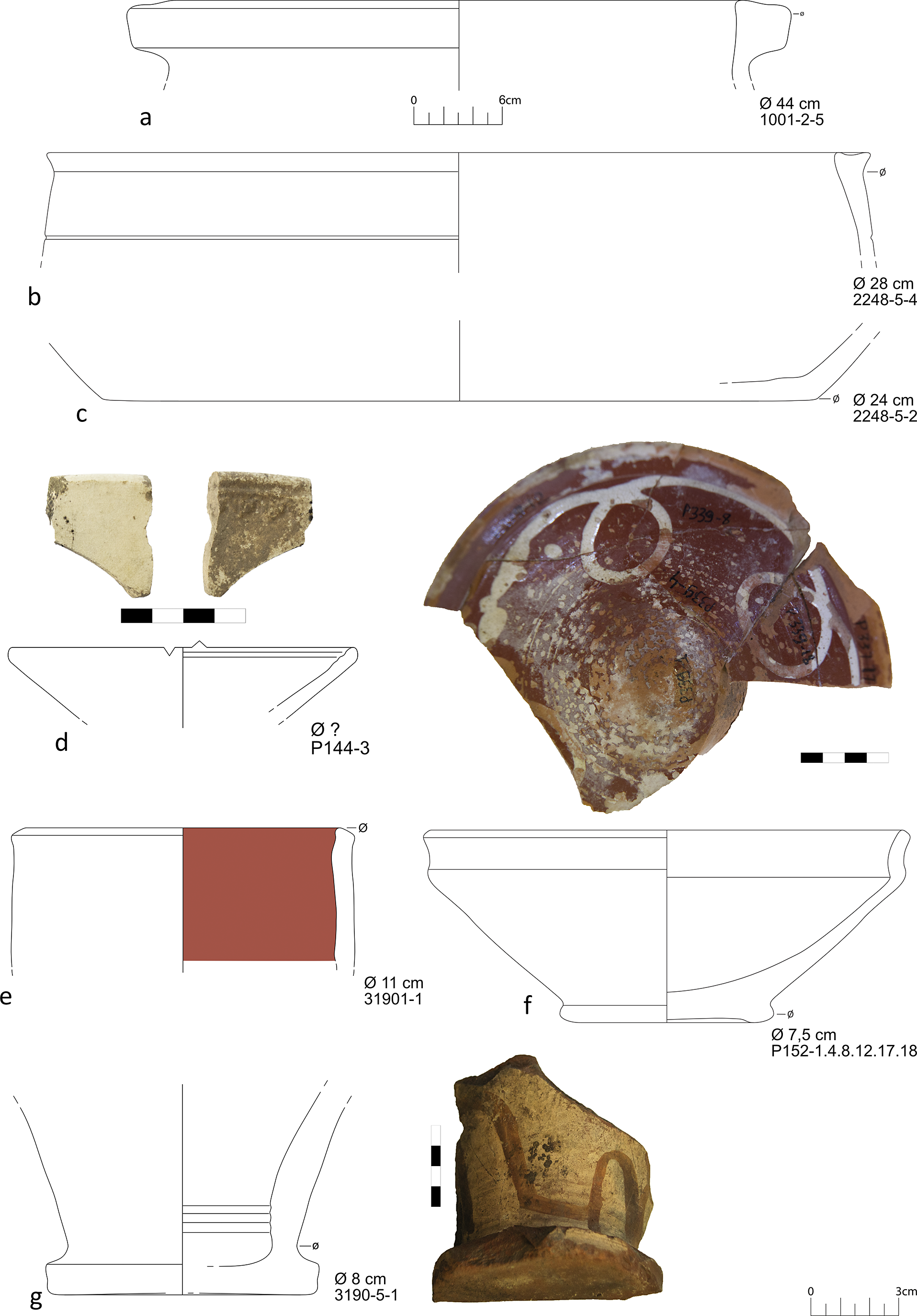

Moreover, some fragments of pithoi (e.g. 1001-2-5; Fig. 25a; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 236, no. 1451, pl. 52; context seventh century CE; Winther-Jacobsen and Bekker-Nielsen Reference Winther-Jacobsen and Bekker-Nielsen2017, 41, pl. 1, nos 88, 130/040.1, 150/080.1; 1003-5-1; cf. Hautumm Reference Hautumm and Jantzen2004, 235, nos 1448–9, pl. 52, 237, no. 1460, pl. 53) and water pipes (1008-1-4, 3009-4-1, 3009-4-5; cf. Laflı and Kan Şahin Reference Laflı and Kan Şahin2015, 126–7, no. 263, pl. 19) were found at Agios Ioannis.

Fig. 25. Ceramics from Limnionas and West Kampos (illustrations by Sabine Huy, Caitlin Bamford, Bettina Bernegger, Georgia Tsiouprou).

West Kampos and Limnionas

Although these areas yielded a very small number of finds, it can be discerned that the range of forms corresponds to that of the others. At Limnionas, in addition to two Hellenistic amphorae (2240-5-3, 3114-5-1), two small sherds of Archaic banded ware were found. There were no finds from the Roman period and, surprisingly, no Early Byzantine tableware. Only two handles from Samos Cistern type amphorae belong to this phase (2237-1-2, 2271-2-1). The rim of a plate of Glazed White Ware can be dated to the Middle Byzantine period (P144-3; Fig. 25d; cf. Vroom Reference Vroom2014, 74–7). In addition, some well-preserved Early Modern cooking vessels were found, some of which could be restored from several fragments (e.g. 2248-5-4, 2248-5-2, P152-1, P152-4, P152-8, P152-12, P152-17, P152-18; Fig. 25bcf). Furthermore, a small piece of obsidian (3110-2-1)Footnote 14 and fragments of water pipes (P152-3, P152-16) came from Limnionas.

No pre-Roman fragments were found at West Kampos. Apart from a few lead-glazed body sherds, the ceramics belong to Early Modern cooking vessels with a thick, shiny, dark red glaze (e.g. 3190-1-1; Fig. 25e). The base fragment 3190-5-1 (Fig. 25g) cannot be classified. The painted loop decoration has parallels in late fifth/early sixth century CE contexts from the Athenian Agora (cf. Hayes Reference Hayes2008, 257–8, nos 1488–9, pl. 73). The form of the jug is also known from Early Modern Italy (last quarter of the sixteenth–seventeenth centuries CE; cf. Verrocchio Reference Verrocchio, Bocharov, François and Sitdikov2017, 61, fig. 12:20). Some pieces of iron slag (3179-3-1, 3181-2-1, S3186-1) and a bronze object (2227-5-1) have been found.

Preliminary conclusions concerning ceramics and material culture

A comparative analysis of the pottery assemblages in terms of their chronological distribution and the proportions of the functional groups allows for some preliminary interpretations of the sites.

Finds from Skoubides hill

The assemblage from Skoubides hill at Velanidia is outstanding in the survey universe (Table 15ad). It shows an extremely high amount of Archaic tableware, almost all of which are drinking vessels. Along with a significant number of cooking pots and amphorae as containers for agricultural goods, the spectrum strongly indicates that the area could have been used as a feasting area. The ratio of functional groups seems well comparable to the assemblage of the Archaic sanctuary on Taxiarchis hill in Didyma, where bowls with simple band decoration form the largest group, followed by amphorae (cf. von Miller Reference Miller and Lawall2022, 5). Additional distinctive features of the Archaic assemblage, namely the painted roof tiles with antefix, the scarab,Footnote 15 and the individual pieces of Attic black-figured and Fikellura ware, give reason to interpret the site on Skoubides hill as a ritual or cultic area, furnished with a representative architecture. The hypothesis of a possible sanctuary at Skoubides hill is strengthened by the high presence of the cups with everted rim of types 9,3/9,4, because, as Schlotzhauer (Reference Schlotzhauer2014, 105–6) has pointed out, these delicate cups are almost exclusively known from sanctuaries. In Miletus they were found numerously in the district of Aphrodite of Oikous at Zeytintepe, but hardly in the neighbouring settlement contexts at Kalabaktepe. Many cups of types 9,3/9,4 have also survived from the Samian Heraion (e.g. Kienast and Furtwängler Reference Kienast and Furtwängler2018, 90–1, no. 28, fig. 23; Walter-Karydi Reference Walter-Karydi1973, 24–5; Isler Reference Isler1978, 95, pl. 49) as well as in the sanctuary at the Taxiarchis hill in Didyma (von Miller Reference Miller and Bumke2023c, 474–7 with further references in notes 1199 and 1200).

With regard to the chronology of the possible sanctuary at Skoubides hill, the absence of kotylai, Knickrandskyphoi as well as Knickrandschalen of types 1–4 indicates that activity at the site did not begin before the mid-seventh century BCE. These vessel types, dated between the mid-eighth and mid-seventh centuries BCE, were widespread in the eastern Greek world and would therefore likely have been consumed at Skoubides hill as well.Footnote 16 However, vessel types produced from the second half of the seventh century BCE onwards occur in greater numbers, and we can therefore date the beginning of activity at Skoubides Hill to this period. The range of pottery also suggests that the site was only in use until the end of the sixth century BCE. Only a very small number of finds date from later periods, and the functional composition does not differ from the assemblages of the other zones of the survey universe.

Other zones in south-west Samos

The assemblages from the other zones at Velanidia, as well as at Ormos, Agios Ioannis, and Limnionas, are well comparable to each other. The first millennium BCE phases are much less well represented than the first millennium CE (Table 15a–c). Worth noting is also the limited range of functional groups in the Archaic to Hellenistic periods with almost only amphorae and the near lack of cooking, household and storage ware. This is a very atypical assemblage for settlements. What is also striking in all areas is the scarcity of Roman ceramics in general and the complete absence of sigillatas in particular. As stated above, this can hardly be regarded as a bias in collecting practice. It is only in the Early Byzantine period that we see a significant increase in the number and a differentiation in the functional groups of vessels.

Table 15. Quantification of dated ceramic fragments

Table 16. Ceramics counted per tract

As the short outline showed, the vessels from the southern parts in the Velanidia zone, in Ormos, Agios Ioannis and Limnionas, belong to the same types: the scattered finds of Archaic and Classical tableware belong to Ionian banded ware, Attic imports and local/regional products in Attic tradition (cf. Technau Reference Technau1929, 41–8). The Hellenistic period is represented by typical shapes of colour-coated ware, and from about the fifth century CE especially the large dishes of the Phocaean Red Slip ware of Hayes LRC forms 3 and 10 (mid-fifth to mid-seventh centuries CE) survived. Middle, Late and post-Byzantine finds were few and far between at all investigated areas and do not allow for further interpretation.

The amphorae assemblages are quite homogenous and consist mainly of regional types with only a limited number of imports from the neighbouring areas of the west coast of Asia Minor and rarely from more distant regions. The dominant pre-Roman types are the Samian-Milesian-, the mushroom-rim- and the bead rim types; the dominant Roman and Early Byzantine types are the Dressel 2–4 (pieces from South Aegean and Campania), the Dressel 24, the Kapitän II, the Agora M 273, the Samos-Cistern-type, and the LRA 1 (some from Cilicia) and LRA 2 types.

The chronological distribution of the pottery suggests that human activity in the survey areas took place since Archaic times. However, it was not until the Early Byzantine period that they intensified, possibly indicative of actual settlement activity. It is hard to determine the character of the sites in the earlier phases. The few pre-Byzantine finds from the west of the island contrast with the strong presence of the Archaic–Roman periods in the east of the island, especially in the sanctuary of Hera, but also in the surrounding areas (cf. Technau Reference Technau1929; Tölle-Kastenbein Reference Tölle-Kastenbein1974; Isler Reference Isler1978, Furtwängler and Kienast Reference Furtwängler and Kienast1989, Jöhrens Reference Jöhrens and Rodríguez2004). In this respect, the assemblages indicate that the sites in the survey universe may not have been permanently inhabited before the Early Byzantine period, but were, perhaps, visited seasonally. The small number of vessels without household and storage pots could be interpreted as the remains of small dwellings, probably used only seasonally by farmers during periods of agricultural work.Footnote 17 The scarce pottery of the area at West Kampos does not allow any conclusions yet.

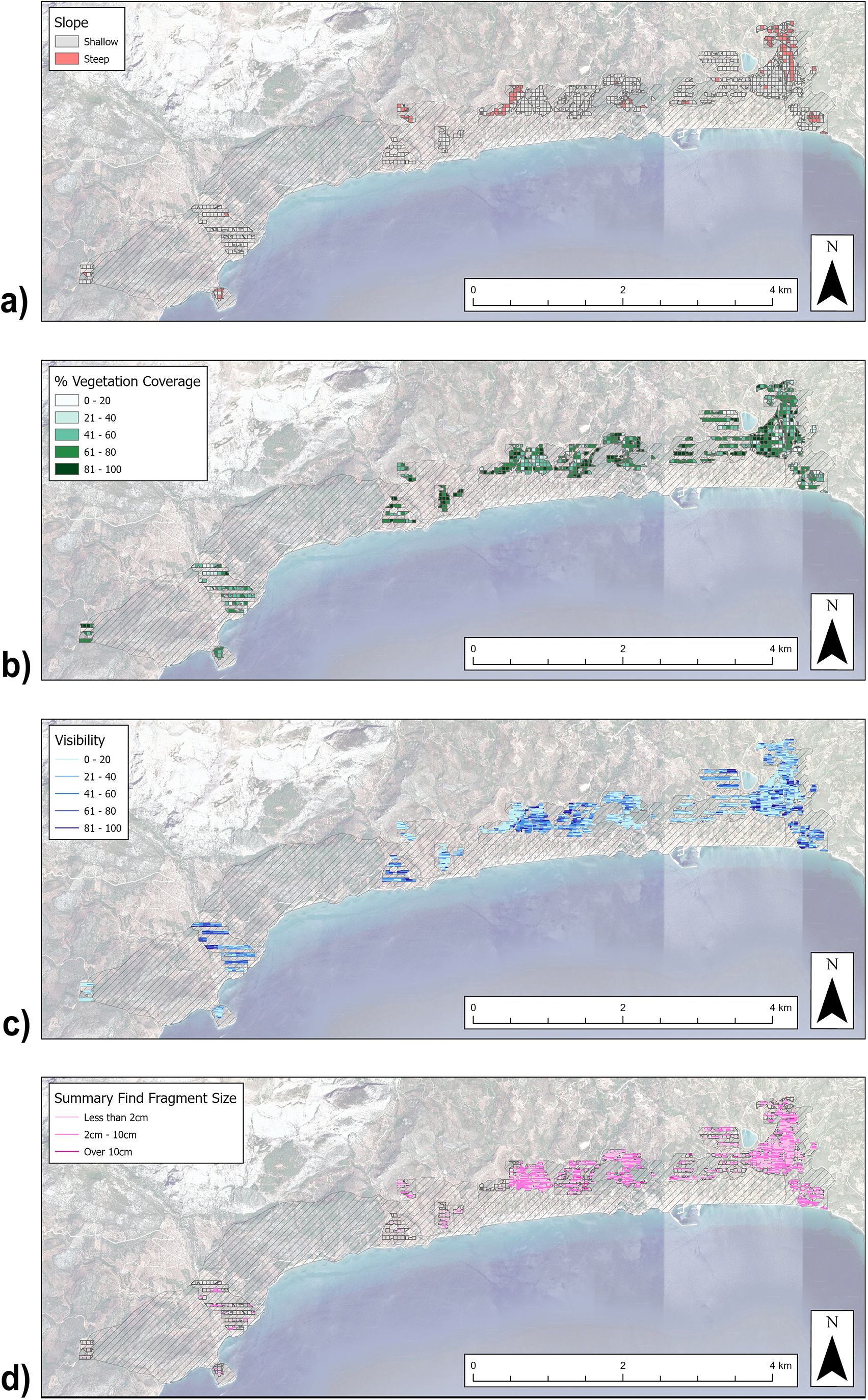

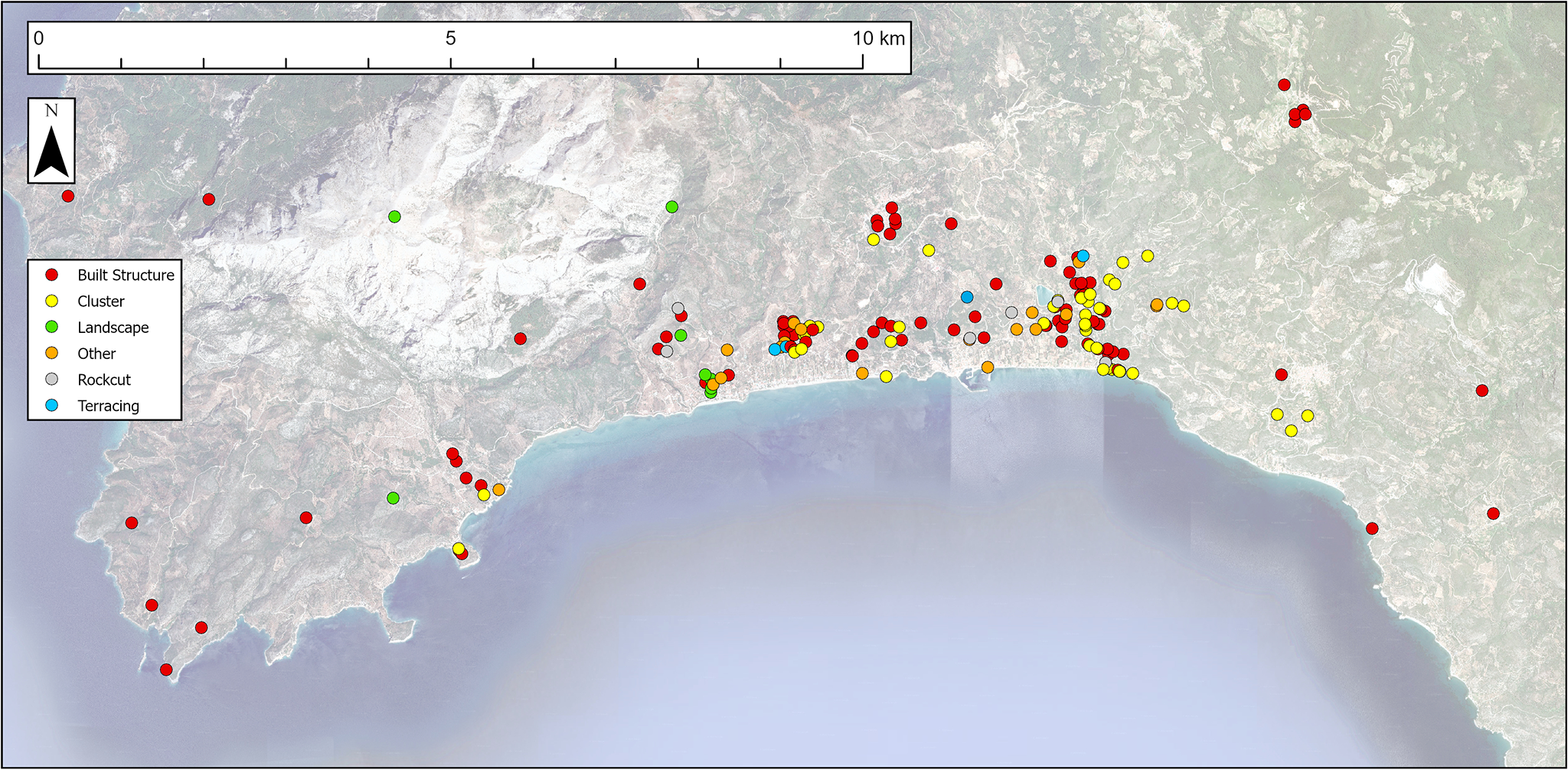

SPATIAL DATA AND SUMMARY STATISTICS by Michael Loy