All major international oncology guidelines advocate for routine nutritional screening in patients diagnosed with cancer, owing to the increased susceptibility of this population to malnutrition(Reference Arends, Strasser and Gonella1,Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2) . The prevalence of cancer-associated malnutrition varies according to tumour type, stage of disease, clinical setting and the type of screening or diagnostic methodology used, with an estimated prevalence of 20–70%(Reference Arends3,Reference Dewys, Begg and Lavin4) . Early identification of cancer-associated malnutrition is vital, as it is associated with negative consequences including decreased tolerance to treatment, poorer quality of life (QoL) and worsened overall survival(Reference Martin, Senesse and Gioulbasanis5–Reference Schaeffers, Scholten and Van Beers7).

A landmark study conducted by Martin et al. found that in 8160 patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, a grading score combining BMI category and percentage weight loss was associated with reduced survival, independent of disease stage, disease site or performance(Reference Martin, Senesse and Gioulbasanis5). This study concluded that even the inability to maintain weight (≥2.4% body weight loss) was significantly associated with worse overall survival(Reference Martin, Senesse and Gioulbasanis5). A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Takaoka et al. which included 26 articles (n = 11,118 patients with cancer), reported that cachexia was associated with an increased hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival [HR: 1.58 (95% CI 1.45, 1.73)](Reference Takaoka, Yaegashi and Watanabe8). Due to advancements in screening and treatments, cancer has become a more chronic condition, with people living longer after a cancer diagnosis(9). As such, there has been a new-found emphasis placed on QoL. QoL in patients with cancer is a multifaceted, patient-specific, subjective measure that includes psychological well-being, functional status and perceptions of health(Reference Wheelwright, Darlington and Hopkinson6). A systematic review conducted by Wheelwright et al. found that 85% of studies (23 of 27 studies) reported a negative relationship between QoL and weight loss(Reference Wheelwright, Darlington and Hopkinson6). The relationship between lean body mass (LBM) and dose-limiting toxicities (DLT) has also been closely examined. Toxicity to chemotherapy can lead to treatment interruptions, deferrals and even complete treatment cessation. Severe DLT can result in hospitalisation or life-threatening situations(Reference Prado, Baracos and McCargar10). A 2024 meta-analysis (n= 22 studies) examined the influence of skeletal muscle mass (SMM) on DLT during chemo(radio)therapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Included studies primarily used SMM by computed tomography (CT). This analysis found that low SMM was associated with both DLT (Odds Ratio (OR) 1.60; 95% CI 1.00–2.58; P = 0.05) and treatment interruptions (OR 1.89; 95% CI 1.00–3.57; P = 0.05), despite heterogeneity with cut points used to define low SMM(Reference Schaeffers, Scholten and Van Beers7).

Reducing the incidence of these debilitating outcomes requires timely identification of the signs and symptoms of cancer-related malnutrition, making systematic malnutrition screening a critical component of oncology care(Reference Arends, Strasser and Gonella1,Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2) . The purpose of this review is to summarise and critique current malnutrition screening and assessment practices and to make recommendations to inform future research and clinical practice.

Current approaches to malnutrition screening in oncology

The basics of good nutritional management is early identification of patients who are ‘at-risk’(Reference Da Prat, Pedrazzoli and Caccialanza11). To prevent underdiagnosing and under-treating malnutrition, The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) recommends that all patients with cancer undergo routine nutritional screening(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2). Timely detection is essential to ensure that appropriate nutritional support is commenced early and results in optimal treatment outcomes(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2). Internationally, there is no consensus on the most effective nutritional screening tool to use(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2). This can make comparisons between studies and obtaining a true value for malnutrition prevalence difficult.

The Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (IrSPEN) National Malnutrition Screening Survey (2023) found that across 26 hospital sites, 64% were using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) and 35% were using the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST)(12). Research conducted by Ní Bhuachalla et al. examined whether commonly used malnutrition screening tools were able to accurately capture hidden malnutrition (adverse muscle and fat changes not detected with weight or BMI alone), usually only detected using de facto gold-standard CT scans in 725 ambulatory patients receiving chemotherapy(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13). The MUST(Reference Elia14), MST(Reference Ferguson, Capra and Bauer15) and the Nutritional Risk Index (NRI)(Reference Buzby, Mullen and Matthews16) were included in this analysis(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13). This study found that in patients classified as ‘low nutritional risk’ by the MUST or MST, a large percentage of patients (40–50%) exhibited abnormal body composition phenotypes (cancer cachexia, low muscle density, sarcopenia). This study also found that the NRI was the most sensitive, and having an NRI score < 97.5 was a significant predictor of mortality (HR 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.8, P = 0.007)(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13). Likely, the prognostic value of the NRI above the MUST and MST stems from the inclusion of albumin, which is a marker associated with systemic inflammation(Reference Soeters, Wolfe and Shenkin17). While this study’s findings support the potential use of the NRI in practice, the MUST and MST continue to be the most utilised screening tools in Ireland and the UK.

Issues with current malnutrition screening practices

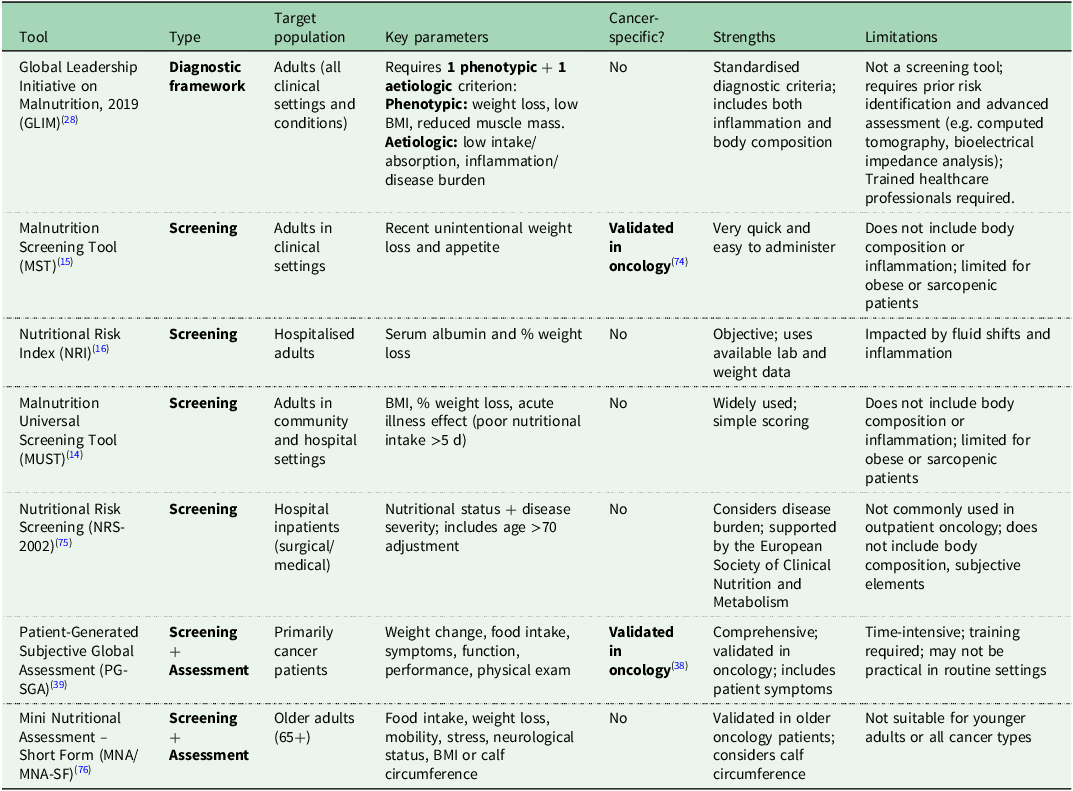

In order to be efficient, nutritional screening must be brief, inexpensive, highly sensitive and have good specificity(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13,Reference Trujillo, Shapiro and Stephens18) . Furthermore, as screening is often delivered by nurses or healthcare assistants, before referral to a dietitian, they should not require nutritional expertise to be appropriately administered. Currently there is no international consensus on the best tool to use for specific patient populations, including oncology(Reference Da Prat, Pedrazzoli and Caccialanza11). Guidelines from international nutritional societies advocate consistently for nutritional screening in patients with cancer, but give no specific indication for the preferential tool to use(Reference Da Prat, Pedrazzoli and Caccialanza11). Even within the same country, this lack of consensus on the most appropriate tool to use results in high heterogeneity and ambiguity surrounding the true prevalence rates of malnutrition(Reference Da Prat, Pedrazzoli and Caccialanza11). Commonly used malnutrition screening, assessment and diagnostic tools have been summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of malnutrition screening and assessment tools in cancer populations

In oncology population groups, commonly used malnutrition screening tools focus primarily on unintentional weight loss, and few consider body composition, systemic inflammation or patient-reported symptoms. Basic anthropometric measurements such as calculating BMI are part of many screening tools used in practice. BMI is a simple equation that indicates whether an individual is an appropriate weight for their height, but it is unable to differentiate between various musculoskeletal and adipose compartments(Reference Amano, Okamura and Baracos19). High fat stores can mask muscle wasting and result in inaccurate interpretations and late dietetic referrals(Reference Lorton, Griffin and Higgins20). Obesity is now an established risk factor for over twelve different types of cancers and includes the most common cancers diagnosed (colorectal, postmenopausal breast) and many of the cancer sites which are difficult to treat (pancreatic, hepatobiliary(21)). Many patients remain overweight or obese at the time of diagnosis despite weight loss often being a presenting symptom. It has been estimated that even in the presence of metastatic disease, 40–60% of patients are overweight or obese(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13). Therefore, the use of basic anthropometric measurements is not appropriate as hidden malnutrition (adverse muscle and fat changes not detected with weight or BMI alone) is often masked by excess adiposity and may go under-recognised when relying on simple nutritional screening tools alone(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13). In a Dutch multicentre study, Latenstein et al. showed that in 202 pancreatic cancer patients, while cachexia was present in 71% of their cohort, only 56% had received a dietetic consultation(Reference Latenstein, Dijksterhuis and Mackay22). This suggests that even in the presence of severe malnutrition, universal access to nutrition care is not being facilitated(Reference Latenstein, Dijksterhuis and Mackay22). Furthermore, despite unintentional weight loss being a red flag for possible cancer, a US study found that of 29,494 primary care patients with at least 2 recorded weight measurements in 2020 and 2021, and excluding those with existing cancer diagnoses, 1% had experienced unintentional weight loss, of which only 21% of these cases were recognised by a doctor.(Reference Rao, Ufholz and Saroufim23) The authors hypothesised that in people with a higher BMI, doctors may assume that the weight loss was intentional and desirable, or may be less likely to notice smaller degrees of weight loss.(Reference Rao, Ufholz and Saroufim23) Partially supporting this hypothesis, Sullivan et al. showed in a 2018 survey of people living with and beyond cancer in Ireland, that of 36% who experienced unintentional weight loss, 21% interpreted this as a positive outcome(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24). Given the relatively little attention given to unintentional weight loss by patients and professionals, the low sensitivity of screening tools further limits the likelihood of earlier detection and intervention. The reliance of many nutritional screening tools on basic anthropometric measures, such as body weight and BMI, raises concerns. According to data from the European Cancer Patient Coalition, only 35% of surveyed cancer patients (n = 842) reported having their weight monitored regularly during treatment(Reference Muscaritoli, Molfino and Scala25). This is particularly striking given that 69.6% of respondents experienced weight loss following their cancer diagnosis, with 36.7% of these cases classified as moderate to severe(Reference Muscaritoli, Molfino and Scala25). According to the definition proposed by Fearon et al., cancer cachexia is characterised by >5% weight loss within six months(Reference Fearon, Strasser and Anker26). It is therefore potentially problematic that current malnutrition screening tools classify such patients merely as ‘at risk’ of malnutrition rather than malnourished. Furthermore, even smaller weight losses (e.g. ≥2.4%) or the inability to maintain weight have been shown to be prognostic of poorer overall survival in patients with cancer(Reference Martin, Senesse and Gioulbasanis27). Continuing to use these tools may result in delayed identification and referral, thereby missing the optimal window for early intervention and contributing to poorer clinical outcomes. Therefore, in oncology settings, universal nutritional assessment may be more appropriate than screening.

Issues with the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition

Despite being associated with debilitating consequences, until recently there was no global consensus on how best to diagnose malnutrition. The Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria were published in 2019 with the aim of standardising the diagnosis of malnutrition internationally(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia28). The GLIM steering committee agreed that diagnosing malnutrition should be simple and include clinically relevant diagnostic criteria that can be used across different clinical settings and by all healthcare professionals(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia28). The GLIM model for diagnosing malnutrition is a two-step approach. First, individuals are screened to identify those ‘at-risk’ for malnutrition using any validated malnutrition screening tool. Once those ‘at-risk’ are identified, the second step is to apply the GLIM criteria(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia28). The GLIM criteria are a list of aetiological and phenotypic criteria with patients requiring at least one of each to be diagnosed with malnutrition. The aetiological criteria include the presence of disease burden/inflammation or reduced food intake/assimilation. The phenotypic criteria include unintentional weight loss, low BMI, or the presence of reduced muscle mass.

The GLIM criteria aimed to provide specific guidance for diagnosing malnutrition across diverse clinical settings, but GLIM is still a relatively new concept and some limitations exist. While the criteria outlines specific diagnostic thresholds for weight loss and BMI, it does not specify cut-points for the numerous techniques that can be used to establish reduced muscle mass(Reference Cederholm, Jensen and Correia28). As a result, the interpretation is more complex, and results in the assessment of muscle mass being less commonly performed, particularly in settings that lack specialised nutrition professionals and/or relevant body composition assessment tools(Reference Compher, Cederholm and Correia29). In 2022, the GLIM consortium appointed a working group to provide consensus-based guidance on the assessment of skeletal muscle mass(Reference Compher, Cederholm and Correia29). It was determined that when available, priority should be given to quantitative methods such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), CT or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). For clinical settings where these methods are not available, anthropometric measurements (e.g. calf circumference, mid upper arm circumference) and subjective physical examinations, although less accurate, are acceptable(Reference Compher, Cederholm and Correia29). The working group acknowledges that specific expertise is required to avoid errors and misinterpretations of the data. Recently, the GLIM consensus group acknowledged the lack of validated cut-points to identify reduced muscle mass and recommend a general inclusive approach to consensus-based cutoffs. The GLIM working group have emphasised the need for future research to establish ethnic and sex-specific cutoff values for each measurement and method (e.g. CT, BIA, anthropometric measures)(Reference Compher, Cederholm and Correia29).

Notably, the first step of the GLIM criteria requires individuals to be screened for malnutrition using a validated malnutrition screening tool, with no additional guidance on which is the preferred tool to use. ‘At-risk’ individuals are then brought onwards for the full assessment. This approach may create disparity if we consider that all patients diagnosed with cancer are inherently ‘at-risk’ of malnutrition and those with a higher BMI might be wrongly classified as not ‘at-risk’(Reference Trujillo, Kadakia and Thomson30). Traditional malnutrition screening tools (MST, MUST, NRI) are often highly specific (e.g. requiring >5% WL, or BMI < 18 kg/m2 to be considered ‘at-risk’ of malnutrition) but lack sensitivity. Notably, low muscle mass is considered in few screening tools, and as a result, rather than directing the highest risk patients for expedited assessment, the suggestion to require a positive screening result restricts a GLIM diagnosis of malnutrition to those patients who experience significant weight loss or low BMI. Moreover, these screening tools most commonly consider phenotypic criteria, rather than aetiological, so offer no opportunity to identify risk factors for subsequent development of malnutrition, in which preventative interventions could be employed. Therefore, bypassing the initial primary screening step is beneficial, particularly in oncology populations who are particularly susceptible to nutrition impact symptoms (NIS), which may reduce oral intake and food assimilation. This approach also ensures that patients with muscle loss, but not weight loss, are not incorrectly excluded. Future screening tools which are more sensitive may render the first GLIM step more appropriate in this context.

Previous research conducted by Scannell et al. has investigated the prognostic value of the GLIM criteria to predict overall survival in a large cohort of patients diagnosed with cancer and with varying treatment intents (e.g. curative, palliative systemic treatment, supportive palliative measures) (n = 1405)(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Dolan31). This study used CT assessment of body composition to determine individuals with the reduced muscle mass phenotypic criterion. In total, 40.4% were diagnosed with malnutrition according to the GLIM criteria. This includes 14.8% with stage 1 moderate malnutrition and 25.6% with stage 2 severe malnutrition(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Dolan31). The addition of CT to the GLIM criteria adds value to the framework. In this large cohort of patients diagnosed with cancer, 54% were overweight or obese. Despite this, 42.2% had lower muscle mass when evaluated by CT. In addition, only 24.8% experienced weight loss >5% in the proceeding 3–6 months. This suggests the presence of hidden malnutrition(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Dolan31). Moreover, the inclusion of CT assessment identified an additional 22.8% of patients as malnourished, despite being weight stable with a normal to high BMI(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Dolan31). Therefore, the use of basic anthropometric measurements are not appropriate as hidden malnutrition is often masked by excess adiposity and may be under-recognised by healthcare professionals. This includes anthropometric techniques frequently incorporated into GLIM (e.g. BMI, mid upper arm circumference, calf circumference)(Reference Compher, Cederholm and Correia29).

What improvements do we need?

The need for greater emphasis on systemic inflammation and nutrition impact symptoms

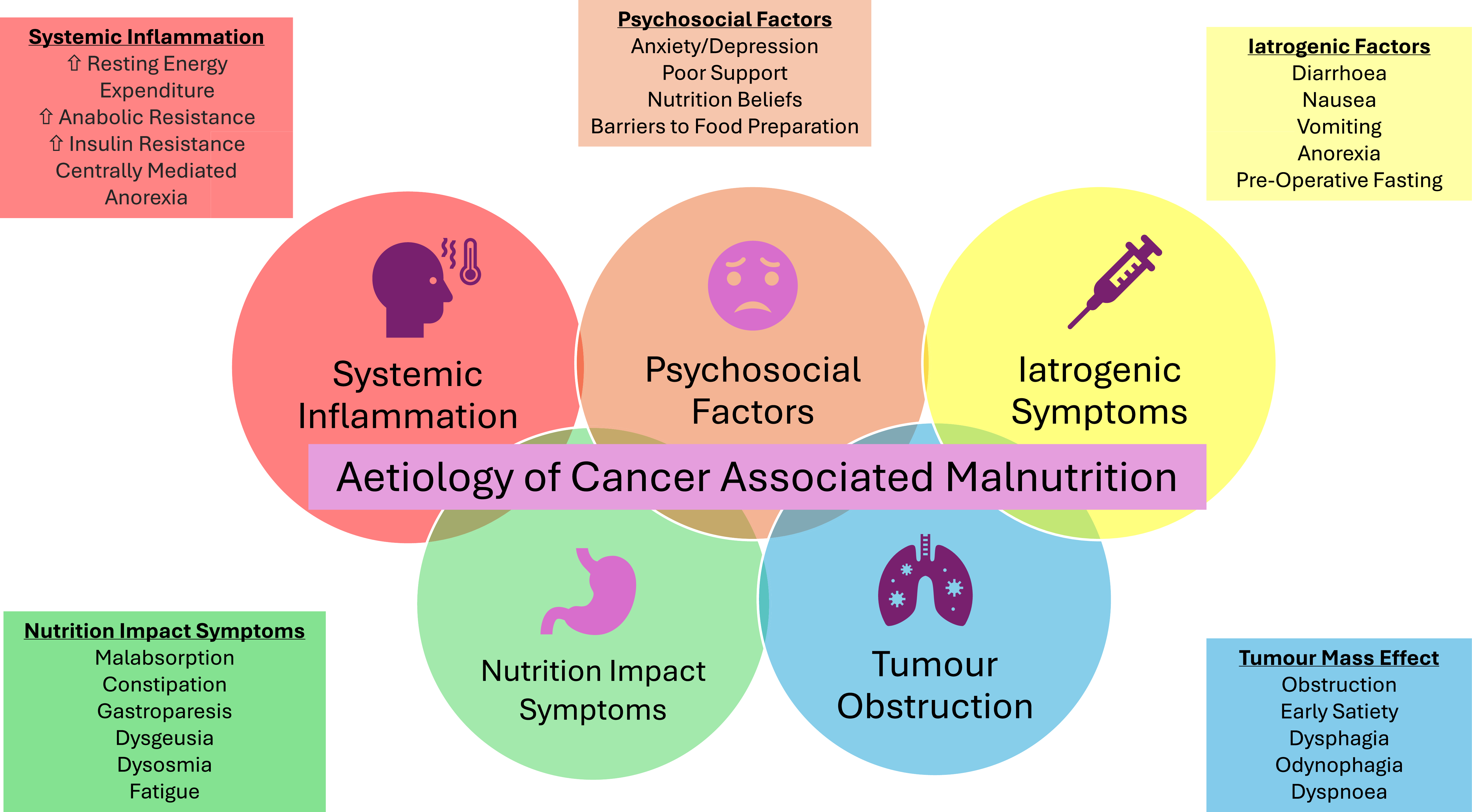

The causes of cancer-associated malnutrition are multifactorial and complex, relating to both the disease and the treatments for the disease(Reference Ryan, Power and Daly32). The aetiology of cancer-related malnutrition has been illustrated in Figure 1. This unique form of malnutrition is not as a result of simple starvation and occurs due to distinctive cancer-specific metabolic derangements, nutrition impact symptoms (NIS) that affect eating, the presence of systemic inflammation, psychological issues, mechanical obstructions and reduced assimilation of nutrients from food(Reference Ryan, Power and Daly32). Systemic inflammation has now been recognised as a distinctive hallmark and driver for the metabolic alterations and muscle wasting that occurs(Reference Argilés, Busquets and Stemmler33). Systemic inflammation is present in 30–50% of advanced cancer patients and is associated with poorer clinical outcomes(Reference McMillan34). Pro-inflammatory cytokines also act centrally on the hypothalamus and can suppress normal eating behaviours, resulting in reduced oral intake. The inflammatory response is responsible for the activation of the anorexigenic (appetite-suppressing) and inhibition of orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) pathways(Reference Argilés, Busquets and Stemmler33). Inflammation is also the unifying mechanism for the entire cluster of sickness behaviours which also decrease food consumption (asthenia, mood alteration, lethargy, depression, anorexia, hyperalgesia and decreased social interaction)(Reference Fearon, Glass and Guttridge35).

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating the aetiology of cancer-associated malnutrition.

Both the disease and its treatment can cause several side-effects which diminish oral food intake(Reference Ryan, Power and Daly32,Reference Crowder, Douglas and Yanina Pepino36) . These complications are known as NIS and include dysphagia, mechanical obstructions, nausea, xerostomia (dry mouth), disrupted bowel movements, and taste and smell alterations. De Pinho et al. collected data from newly-diagnosed patients (n = 4783) using the complete patient-generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA) from 45 different public hospitals in Brazil(Reference De Pinho, Martucci and Rodrigues37). This study found that the most common NIS were reduced appetite (28.7%), dry mouth (20.4%) and nausea (19.8%)(Reference De Pinho, Martucci and Rodrigues37). NIS are strongly associated with malnutrition, as they combine with underlying cancer-related catabolic processes and further exacerbate the wasting process(Reference De Pinho, Martucci and Rodrigues37). The study conducted by De Pinho et al. also reported that patients with >3 NIS (according to the PG-SGA) were at a greater risk of moderate/severe malnutrition (OR 8.34 (95% CI 5.8–12.0, P < 0.001)(Reference De Pinho, Martucci and Rodrigues37). Therefore, it seems prudent for malnutrition screening in oncology populations to include patient reported outcomes and systemic inflammation, to detect those at highest risk of developing malnutrition.

Within the realms of oncology, the PG-SGA is a screening tool which has been validated for use in this context(Reference Bauer, Capra and Ferguson38). The PG-SGA is an adaptation of the subjective global assessment (SGA) and has been validated to evaluate the nutritional status of cancer patients(Reference Bauer, Capra and Ferguson38). It is a non-invasive and assesses weight history, food intake, NIS, activities and function, metabolic stress and body composition simultaneously(39). The short form (SF) version of the PG-SGA is a valuable screening tool as it includes patient-reported outcomes and can be used alone as a screening tool, or as the first step in a more comprehensive assessment(39). According to the IrSPEN 2023 malnutrition survey, the PG-SGA was not reported as being used at any clinical site in Ireland(12). This may reflect its more comprehensive content and the consequent perception that it is time-consuming to complete, although a 2020 study reported a median self-completion time of 2 min 42 s for patients with head and neck cancer(Reference Jager-Wittenaar, De Bats and Welink-Lamberts40). Furthermore, when using the paper-based version, only 26% of patients required assistance, indicating that self-completion of the PG-SGA-SF is feasible in this population(Reference Jager-Wittenaar, De Bats and Welink-Lamberts40).

A significant benefit of the PG-SGA-SF is the focus on patient-reported outcomes and NIS. The European Cancer Patient Coalition published results from a survey of 907 patients diagnosed with cancer and found that 72.5% experienced feeding problems due to their illness or therapy(Reference Muscaritoli, Molfino and Scala25). Placing a renewed emphasis on NIS should be at the forefront of screening patients for nutritional risk, as these symptoms will likely precede the occurrence of weight and muscle loss. Early identification and subsequent management of these debilitating issues can potentially improve the cancer-associated malnutrition trajectory.

Anecdotally, this research group has recently used the PG-SGA-SF to screen patients for eligibility for enrolment onto a multi-country nutritional intervention trial (Clinical Trials.gov identifier: NCT05495360)(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Tuček41). To be eligible for the intervention, patients needed to have a diagnosis of colorectal or non-small cell lung cancer and be ‘at-risk’ of malnutrition according to the PG-SGA-SF (scoring > 4). In the Irish cohort, the majority were overweight or obese and weight stable. Despite this, participants enrolled were extremely symptomatic scoring high values on the PG-SGA-SF. Therefore, it could be hypothesised that had another screening tool been used to determine eligibility (e.g. MST or MUST), that these participants ‘at-risk’ of malnutrition would not have been recruited due to the presence of excess adiposity. This shows the value of the PG-SGA-SF as it has the ability to highlight those truly ‘at risk’ of malnutrition, where there is still potential to halt the development of malnutrition. This is far more useful than establishing the prevalence of those already malnourished, in whom intervention may be less effective and more resource intensive.

The need to consider body composition

As discussed, a considerable number of screening tools which are based on anthropometric measurements will likely miss patients who are malnourished(Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13). Cancer-associated malnutrition is not as simple as just unintentional weight loss. It is an umbrella term for several different abnormal body composition types including sarcopenia, low muscle attenuation, sarcopenic obesity and the spectrum of cancer cachexia(Reference Ryan, Power and Daly42). While these abnormal body composition phenotypes are associated with debilitating consequences, they are often not visible to the naked eye(Reference Prado, Birdsell and Baracos43). In patients diagnosed with cancer, changes in body composition can be masked by weight stability and changes can occur even in early-stage disease(Reference Prado, Laviano and Gillis44). As a result, patients with these conditions are often not diagnosed with malnutrition until the refractory stage, as the majority of screening tools are primarily based on BMI and do not flag individuals as ‘at-risk’ until significant weight loss has occurred (e.g. MUST, MST), at which point they often already meet the phenotypic criteria for a diagnosis of malnutrition(Reference Lorton, Griffin and Higgins20).

Recent advancements in medical technology have meant that CT scans are now the de facto gold standard method of body composition analysis(Reference Prado, Birdsell and Baracos43). CT is not commonly used outside of the research setting due to high equipment costs, the need for highly skilled healthcare professionals, lack of portability and radiation exposure(Reference Cruz-Jentoft, Bahat and Bauer45). In addition, cut-points for low muscle mass have not yet been established, although a skeletal muscle mass that is 2 standard deviations below the mean reference value of a healthy population is generally considered to be acceptable to define low levels(Reference Baumgartner, Koehler and Gallagher46). The Martin et al. threshold values, established by optimal stratification according to overall survival, are frequently used in the literature(Reference Martin, Birdsell and MacDonald47). These values are derived from specific oncology populations (e.g. gastrointestinal and respiratory tumours), which are not necessarily representative across all conditions. In addition, these values are often based on overall survival, rather than a more proximate measure of the presence of malnutrition(Reference Baumgartner, Koehler and Gallagher46). There is currently a gap in the literature for cut-points that are derived from a healthy population and can be extrapolated to include various cancer cohorts(Reference Van Der Werf, Langius and De Van Der Schueren48). Although work conducted by van der Werf et al. has suggested that low muscle mass is defined using the 5th percentile of a healthy sex-specific reference population (n = 420), but was not standardised for age(Reference Van Der Werf, Langius and De Van Der Schueren48). It is hoped that future automation of CT software will result in almost instant reporting of body composition, that can then be easily incorporated into malnutrition screening and better inform healthcare professionals about the clinical situation of patients(Reference Pickhardt, Summers and Garrett49). Even in the absence of clear thresholds for normal versus abnormal, the intra-individual trends may be insightful.

In the absence of quantitative imaging, the SGA or nutrition-focused physical exam has also been validated to assess changes in body composition(Reference Hummell and Cummings50). While this requires training and experience, it is accessible, without the need for expensive equipment. On the other hand, there has been growing interest in using hand-grip dynamometry as a surrogate for muscle health in clinical practice, as it is a relatively simple and quick measurement. However, it is important to note that functional gains may occur in the absence of gains in muscle mass, and that in the context of cancer care, mass is important, not only for its locomotor functions, but also due to its other physiological roles, notably being the bodies largest reservoir of amino acids, and playing an important role in nitrogen and glucose homoeostasis(Reference Ling, Jiang and Ru51,Reference Mukund and Subramaniam52) . Additionally, reduced muscle mass can lead to reduced volume of distribution of hydrophilic chemotherapy agents, increasing the risk of adverse reactions(Reference Prado, Baracos and McCargar10,Reference Prado, Baracos and Xiao53–Reference Assenat, Ben Abdelghani and Gourgou55) .

The need for nutritional screening guidelines for the ambulatory setting

Due to the lack of consistency on which screening tool to use, nutritional screening is often not incorporated into routine clinical practice, particularly in the ambulatory oncology setting. National Clinical Guidelines from the Department of Health in Ireland recommend that all hospital inpatients are screened for malnutrition on admission or within 24 h of admission(56). But in Ireland, and elsewhere in Europe and the USA, nutritional screening is not mandatory in outpatient or ambulatory services for systemic anti-cancer treatment(Reference Muscaritoli, Molfino and Scala25,Reference Trujillo, Claghorn and Dixon57) . This is of concern when we consider that 90% of oncology care is provided in the ambulatory setting and that for a considerable number of patients this setting will be their only means of accessing their oncology team(Reference Trujillo, Claghorn and Dixon57). Trujillo et al. have previously reported that only 53% of outpatient cancer centres reported screening for malnutrition risk in the USA, and of these, only 65% were using a validated screening tool(Reference Trujillo, Claghorn and Dixon57). Similarly, a 2020 survey of Italian oncologists found that only 16% of oncology units were using validated nutrition screening tools(Reference Caccialanza, Lobascio and Cereda58).

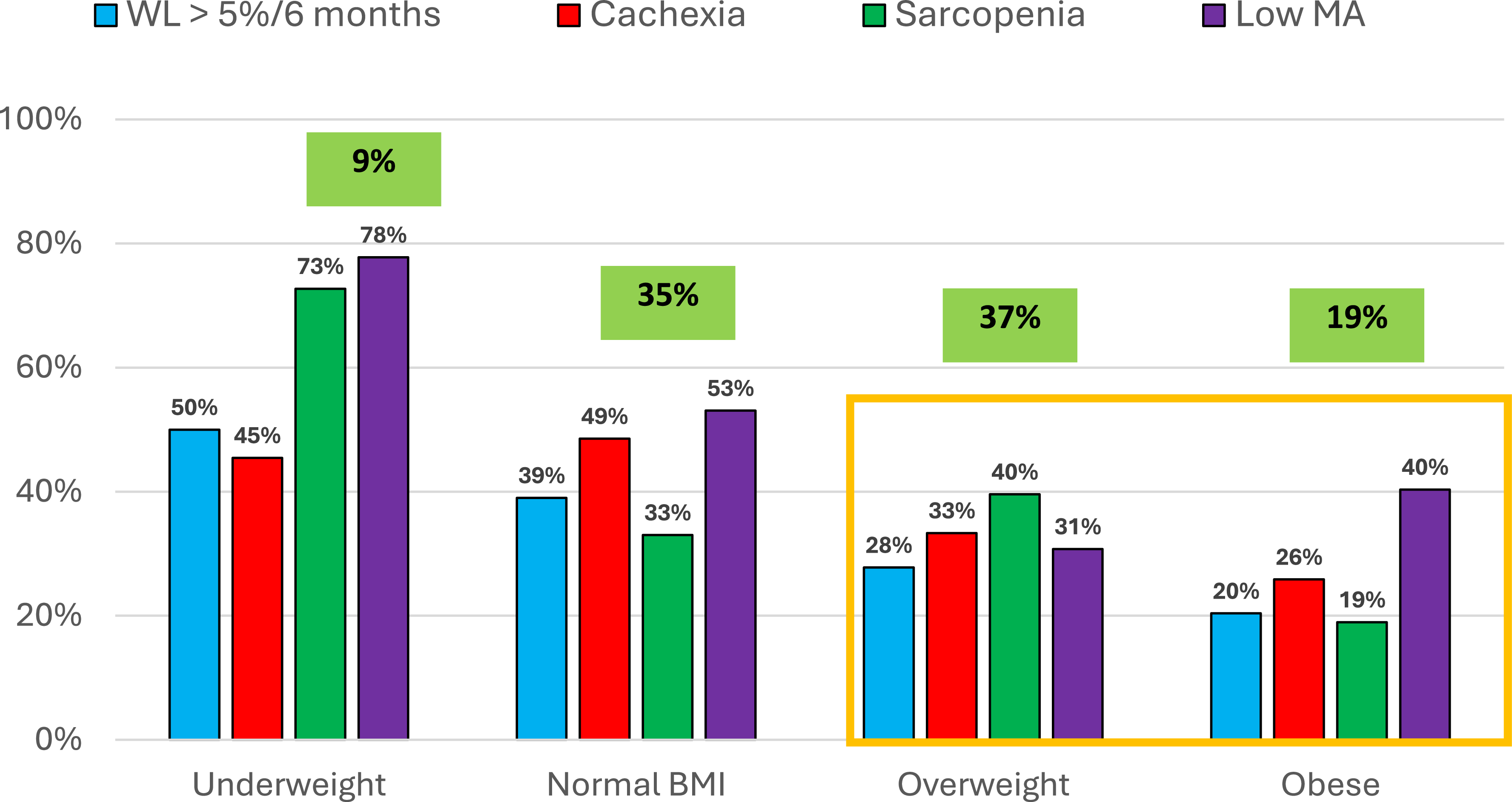

Research from Sullivan et al. has shown that in a large cohort of ambulatory patients on systemic cancer treatment (n = 940), despite 56% being overweight or obese, 73% had an abnormal body composition phenotype when evaluated by CT. Hidden malnutrition (adverse muscle and fat changes not detected with weight or BMI alone) was highly prevalent, as 65% of those with an abnormal body composition were overweight or obese(Reference Sullivan, Daly and Scannell59). Notably, only 9% of the cohort has visible malnutrition (e.g. BMI < 18.5kg/m2)(Reference Sullivan, Daly and Scannell59). This marked incidence of abnormal body composition phenotype despite BMI classification has been illustrated in Figure 2. These figures are particularly stark given that there is currently no mandate nor guidance on how best to screen these outpatients for malnutrition. The ESPEN guidelines themselves, particularly with regards to re-screening, are quite ambiguous(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2). The panel states that in order ‘to detect nutritional disturbances at an early stage, we recommend to regularly evaluate nutritional intake, weight change and BMI, beginning with cancer diagnosis and repeated depending on the stability of the clinical situation (Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2) ’. The lack of specificity in current recommendations contributes to ambiguity in guideline interpretation and poses challenges for consistent implementation. It is therefore essential that future guidelines provide comprehensive instructions tailored to both inpatient and outpatient oncology populations, specify preferred validated screening tools and define appropriate re-screening intervals, such as per cycle of systemic treatment(Reference Bossi, De Luca and Ciani60).

Figure 2. Bar chart depicting the percentage of abnormal body composition phenotypes present in each BMI classification (n = 940)(Reference Sullivan, Daly and Scannell59).

WL: Weight Loss

Low MA: Low Muscle Attenuation (Fatty Infiltration of Muscle)

The need for proactive nutritional services

Due to the high prevalence of hidden malnutrition and the aforementioned issues with current malnutrition screening practices, recognition and referral to a dietitian can often occur in the advanced stages, when the condition is refractory and potentially resistant to any nutritional intervention(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2,Reference Ní Bhuachalla, Daly and Power13,Reference Fearon, Strasser and Anker26) . Irish research by Lorton et al. examined referral practices in five tertiary hospitals including public, private, inpatient and outpatient oncology services (n = 200 mixed cancer types). Over half of the cohort were being treated with palliative intent (52%). This study found that 70% of patients had >2 nutritional symptoms, with the most common being anorexia, nausea and early satiety(Reference Lorton, Griffin and Higgins20). Despite significant weight loss (66% had lost >5% in the previous 3–6 months), a considerable number had a normal weight BMI (48%) or were overweight/obese (40%). The authors also reported that in almost half of new referrals, an earlier opportunity to see a dietitian was missed. In most cases, referrals were reactive as opposed to being proactive(Reference Lorton, Griffin and Higgins20).

Therefore, to improve outcomes, nutrition services in oncology as a whole need to become more proactive and preventative in nature. In an ideal situation, a 100% referral pathway would be the standard of care for all patients diagnosed with a condition that places them at an increased risk for malnutrition (e.g. head and neck cancers, upper gastrointestinal). But this is potentially an overambitious proposal, particularly when it was estimated in 2019 by the Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute (INDI) that there is only 1 dietitian per every 4500 patients with cancer in Ireland(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24). A comparable situation has been observed in the USA, where a survey of 215 cancer centres revealed that each dietitian was responsible for approximately 2308 patients diagnosed with cancer(Reference Trujillo, Claghorn and Dixon57). As a result, clear referral pathways for dietetic assessment following a positive screen are often lacking, which reduces the effectiveness of screening tools even when they are applied correctly. Advances in oncology, including more aggressive multimodal treatments and improved survival, have increased the need for dynamic, accurate and context-specific nutritional screening approaches. As the field shifts towards personalised medicine, revisiting existing tools and integrating novel technologies, patient-reported outcomes, systemic inflammation and body composition measures becomes essential to improve patient outcomes(Reference Kiss, Loeliger and Findlay61,Reference Hébuterne, Lemarié and Michallet62) .

A lack of a proactive nutrition services results in patients that have been forced to turn outside of conventional healthcare for nutrition information, resulting in widespread misinformation. Results from the literature shows that patients diagnosed with cancer have a high demand for nutritional information(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24,Reference Van Veen, Beijer and Adriaans63) . It has been estimated that 30–66% of patients with cancer have unmet needs related to nutrition information(Reference Van Veen, Beijer and Adriaans63). But one-to-one dietetic counselling is not available for all patients and results from an Irish national survey (2021) showed that in the absence of evidence-based information provided by registered dietitians, over one third (36.9%) of Irish cancer patients reported engaging in biologically based complementary and alternative medicine practices (BBCAM)(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24). An Italian survey published in 2018 found that 56.1% of patients (n = 705) reported changing their diet post-diagnosis(Reference Martin, Senesse and Gioulbasanis5). This includes 31% modifying their diet due to side effects of treatment and 18% because of cancer-site related complaints(Reference Gavazzi, Sieri and Traclò64). We have previously reported that in Irish cancer survivors, the use of BBCAM increases significantly from 28% pre-diagnosis to 34% post diagnosis (P < 0.001)(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Curtin65). The most common special diets reported by the BBCAM users (n = 97) included dairy-free (32%), gluten-free (19%), intermittent fasting (17%), ketogenic diet (15%) and juicing/detox diets (10%)(Reference Scannell, Sullivan and Curtin65). Self-imposed restrictive dietary patterns can place already vulnerable patients at an even greater risk of nutritional inadequacies and contribute to the development of cancer associated malnutrition(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2).

In addition, results from an Irish national survey (n = 1073) found that 44% of cancer survivors surveyed had lost weight, of concern, 27% reported being ‘delighted/happy’ about losing weight(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24). Moreover, the majority (56%) felt confused by the often conflicting nutrition information available in the media and offered by people around them(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24). To combat the array of misinformation, a proactive nutrition service could provide all patients who have been diagnosed with cancer with first-line nutrition advice. This advice could centre around the importance of weight maintenance for improved clinical outcomes and aim to combat common nutrition and cancer myths(Reference Arends, Bachmann and Baracos2,Reference Martin, Senesse and Gioulbasanis27) . Availability of regular group-based education could also help to alleviate issues with staffing levels, for example, a monthly dietetics-led information session would allow for patients to attend in the weeks preceding or immediately following the start of their treatment, to ensure early access to reliable information, without being as resource intensive as 1:1 dietetic consultations. Education could also be provided by webinars devised by oncology dietitians, allowing patients to access the content at a time that suits them best. This approach may enable more efficient allocation of 1:1 dietetic counselling time to complex patients, ensuring that resources are directed towards patients with the greatest clinical need, requiring personalised interventions.

More recent Irish data shows that almost 60% of patients diagnosed with cancer who had not seen a dietitian reported wanting access to more dietetic support, including access to reliable information(Reference Sullivan, Rice and Kingston24). Lack of access to specialised care results in knowledge gaps that are filled by unqualified outlets such as the media, social media and alternative health providers who promote complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)(Reference Grimes and O’Riordan66). Previous work conducted by the Clinical Nutrition and Oncology Research Group at University College Cork has aimed to proactively bridge this gap by creating a novel, evidence-based resource written by dietitians and freely available to all patients diagnosed with cancer in Ireland(Reference Scannell, Hanna and O’Sullivan67). The ‘Truth Behind Food and Cancer: Simple Explanations Based on Scientific Evidence’ is a colourful resource which discusses popular diet-based CAM (e.g. ketogenic diet, alkaline diet, juicing and detox diets) and provides an evidence-based rationale to counter these unproven dietary strategies. This booklet is endorsed by the INDI, the National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) and the Irish Society of Medical Oncologists (ISMO)(Reference Scannell, Hanna and O’Sullivan67). Funding was secured from charity partner Breakthrough Cancer Research to print 20000 copies for free distribution to cancer centres nationwide and was made available online(Reference Scannell, Hanna and O’Sullivan67). Similar informational resources targeting simple malnutrition prevention strategies and symptoms management tips could contribute to prevention of malnutrition in those identified as ‘at-risk’ by more sensitive, symptom-based screening tools.

Prehabilitation

Prehabilitation is a concept which aims to optimise both physical and psychological suitability through multidisciplinary involvement prior to surgery with the aim of counteracting muscle loss(Reference Tartara, Da Prat and Mattavelli68). The use of this ‘prehab’ framework in preparing patients for systemic anti-cancer treatment is an evolving concept(Reference Tartara, Da Prat and Mattavelli68). Although published trials to date have demonstrated considerable heterogeneity, they consistently suggest that prehabilitation exerts a positive impact on functional capacity, with potential reductions in postoperative complications and hospital length of stay(Reference Tartara, Da Prat and Mattavelli68–Reference Gennuso, Baldelli and Gigli70). A systematic review of 55 studies (26 of which reported on oncology populations) reported that prehabilitation is a promising intervention to improve postoperative outcomes, but future research to establish the optimal intervention using robust clinical trials is needed(Reference McIsaac, Gill and Boland69). The Royal Marsden Hospital in the UK are currently investigating the design of a personalised prehab programme for patients diagnosed with cancer, which can then be implemented across the National Health Service (NHS)(71).

Given the requirement for nutritional interventions to be commenced early, it could be hypothesised that first-line nutrition advice could be provided to patients prior to initiation of systemic anti-cancer treatment as a proactive way to manage the cancer-associated malnutrition trajectory. As previously mentioned, and considering poor dietetic staffing levels, this advice could be provided as group education, which could also offer an opportunity for peer-support, in a facilitated environment in which misinformation can be addressed if it arises.

Digital advances

Innovations in technology and data science offer promising avenues to enhance malnutrition screening and may offer a more proactive approach. Machine learning algorithms have been used to identify malnutrition risk based on routine clinical and imaging data with high accuracy(Reference Sguanci, Palomares and Cangelosi72). Integration of screening tools into electronic health records can prompt clinicians to assess nutritional risk systematically and refer patients efficiently. Dynamic or stratified screening models, tailored to cancer type/stage and treatment may improve sensitivity and allow better targeting of resources(Reference Hustad, Koteng and Urrizola73). Precision oncology also offers a new frontier, linking nutritional status to treatment personalisation. Central to these innovations is a multidisciplinary approach, involving dietitians, oncologists, nurses and IT specialists working together to embed nutrition as a core component of cancer care. One example of this is the My Path project(Reference Hustad, Koteng and Urrizola73). The My Path is a European Project aiming to implement patient-centred care at nine European cancer centres using a digital based solution(Reference Hustad, Koteng and Urrizola73). The My Path nutrition assessment considers MST, modified GLIM, BMI, weight change, health status (functional status, cancer diagnosis and prehabilitation needs) and inflammatory status (C-reactive protein levels) of each presenting patient. Based on this assessment, the digital solution suggests tailored, evidence-based nutritional interventions. Continuous monitoring through patient-reported outcomes and clinical consultations will customise care to patients’ dynamic nutritional needs(Reference Hustad, Koteng and Urrizola73). The rationale behind this project aligns with the oncology paradigm of ‘staging the tumour, treating the tumour’, as oncology professionals now acknowledge that nutrition care should also ‘stage the patient and treat the patient (Reference Hustad, Koteng and Urrizola73) ’. However, the feasibility and application of this automated process outside of the research setting has yet to be established. It will also depend heavily on sufficient digital resourcing, which may result in furthering inequalities for those treated in centres without robust electronic medical record systems.

Conclusion

Malnutrition remains a hidden but modifiable burden in oncology, with far-reaching consequences for patients and health systems. While screening tools exist, their inconsistent use, limited sensitivity and poor integration into care pathways diminish their impact. The emergence of new evidence around body composition, systemic inflammation and patient-centred metrics calls for a fundamental rethinking of how we identify and manage nutritional risk. It is insufficient to merely advocate for improved or oncology-specific malnutrition screening tools. In reality, a comprehensive restructuring of nutritional services is urgently needed, particularly within ambulatory care settings. Future efforts should prioritise proactive, rather than reactive approaches to nutritional support to prevent cancer-associated malnutrition and mitigate its impact on clinical outcomes. Reimagining malnutrition screening as a dynamic, technology-enabled, multidisciplinary process offers an opportunity to improve outcomes across the cancer care continuum. Therefore, an appetite for change is not only timely, but also essential.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Irish section of the Nutrition Society for inviting this review paper as part of the postgraduate competition.

Author contributions

CS: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; ESS: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing; AMR: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Financial support

None to declare.

Competing interests

ESS is a former Irish Research Council Enterprise Partnership Scheme Postdoctoral Fellow, co-funded by Nualtra. She has received travel fees from Nutricia and writing honoraria from the British Dietetic Association. She is a member of the management committee of the Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition & Metabolism (IrSPEN). All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.