Between 1898 and 1923, a series of disputes erupted among fishing communities throughout the British Gold Coast Colony (modern-day Ghana) following the introduction of new sea fishing nets. The conflicts centred around herring drift (ali) and beach seine (yevudor) nets, which were introduced by African entrepreneurs in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. These nets soon became contentious due to their ability to yield larger and less selective catches than other nets then in use. Disputes quickly arose in which opposing groups voiced concerns that the higher productivity of the nets not only impacted on fish prices but also threatened nearshore fish stocks. All along the coast, fishers debated the environmental and economic consequences of adopting the nets, which debates shifted across African and colonial forums as each group sought support for their positions. These were innovations and debates driven by competing groups of fishers at a crucial juncture in the history of the fishing industry in Ghana.

This twenty-five year period has been recognised as a watershed moment in existing studies of fishing in Ghana. Most notably, Albert De Surgy, Emile Vercruijsse, and Barbara Louise Endemaño Walker have utilised these disputes to discuss the transformation of the Ghanaian fishing industry. Focusing on protests surrounding the nets, De Surgy and Vercruijsse argue that these were driven by environmental concerns and labour concerns, respectively. Walker, meanwhile, contends that British emphasis on the maritime commons—whereby the “high seas” and the resources therein were considered as the common property of all mankind (res communis)—when adjudicating these disputes enabled women to maintain as much access to property in marine resources as men. This secured their longstanding control over the processing, production, and marketing of fish, enabling them to leverage influence through collective action and ownership of fishing equipment. These works each recognise that the disputes also led to the greater intrusion of colonial law over fishing activities.Footnote 1 Yet, by focusing on overarching narratives of fisheries transformation, these studies have tended to brush over the complex debates that arose within fishing communities as fishers invented, adopted, and challenged these nets. By viewing these quarrels primarily through the lens of colonial legal impositions, these works have also downplayed the considerable improvisation of African and colonial authorities when reacting to rising tensions within fishing communities.

This reflects the existing historiography of fishing within colonial Africa more generally, in which scholars have concentrated on either the histories of particular fishing communities and their changing practices or, alternatively, the trajectory and impact of colonial development policies.Footnote 2 Bridging these two perspectives, this article demonstrates how the technological innovations driven by fishers in coastal Ghana were debated and challenged across different fishing communities and how the manoeuvring of opposing groups pulled African and colonial authorities into the debates. This stresses the reactive and improvised nature of colonial policy that arose in response to coastal disruptions, while emphasising the ways in which different groups of fishers resisted the decisions of African and colonial authorities when these did not align with their perspectives.

In doing so, this article situates these disputes within the rich historiography of African technological innovation that has emerged over the past decade. This scholarship has emphasised the vibrant and diverse sites of work that acted as open-air spaces of experimentation and knowledge production throughout Africa from the precolonial to the modern period. This has firmly challenged once dominant views arising from Western imperialism that portrayed Africa as a place without technology or Africans as solely recipients of technology transfers. This has also challenged the idea of Africans as solely victims of “inbound” technologies.Footnote 3 As Clapperton Mavhunga argues, Africans were “designers and innovators in their own right,” who did not merely react to incoming technologies.Footnote 4 Rather, they made active choices to accept, reject, remake, or reappropriate technologies to fit within and expand their existing repertoires of tools and methods.Footnote 5 While scholars have interrogated African technological innovations across a vast range of sectors, fishing and other marine industries have received only limited investigation. Although not the focus of their analysis, Emmanuel Akyeampong, Setsuko Nakayama, and Paul Abiero Opondo have each shown that fishers operating in diverse waterscapes in Ghana, Malawi, and Kenya actively experimented with indigenous and endogenous fishing technologies throughout the colonial period.Footnote 6

What has yet to be closely interrogated is how sites of fishing innovation also became sites of intense conflict as different groups debated new technologies. Across the histories of technological change in colonial Africa, studies of conflict have tended to focus on clashes between African innovators and colonial technological visions.Footnote 7 As Gufu Oba explains, African responses to colonial development programmes were extremely variable and influenced more by pressure from within communities than through coercive action by colonial officials.Footnote 8 In the case of fishing nets in the Gold Coast Colony, however, this was a direct conflict between African resource users, in which the colonial occupation offered alternative avenues for competing groups to challenge one other. As Rachel Jean-Baptiste, Emily Osborn, Kristin Mann, Richard Roberts, and others have argued, African men and women made strategic use of colonial legal forums to reshape the boundaries and terms of their disputes with other African men and women.Footnote 9 At the turn of the twentieth century, processes of technological innovation and legal forum shopping converged in the Gold Coast Colony as competing fisheries participants sought to advance their agendas by shifting their conflicts between African and colonial legal processes. Pairing fishers’ testimonies as recorded in legal proceedings and newspaper reports with the written record of law and policy formation by African and colonial authorities, this article provides new insight into how technological innovation drove processes of arbitration and negotiation in the context of colonial occupation.

Beginning with a brief overview of fishing in precolonial Ghana, the article then focuses on the invention and introduction of ali and yevudor nets in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, tracing the primary arguments advanced by net advocates and opposers. These centred on environmental and economic concerns while raising issues relating to jurisdiction, migration, and class. The article then charts the active solicitation, manoeuvring, and pressuring of fisheries participants, which pulled African authorities and colonial officials into the debates. Across these twenty-five years, the arguments and decisions emanating from these disputes were drawn and redrawn as opposing groups navigated African and colonial institutions in search of favourable outcomes. In the process, the voices advocating for caution within the fishing industry were effectively marginalised through the manoeuvring of net advocates while the introduction of colonial arbitration within the realm of fisheries offered new challenges to the authority of African leaders within the marine space with lasting consequences.

Fishing in Precolonial Ghana

According to an oral tradition recorded in 1895 by Carl Christian Reindorf, a Euro-African missionary born in Prampram, the sea fishing industry commenced in coastal Ghana under Farnyi Kwegya—one of two giants who emerged from the sea with a great number of followers. Founding Moree as a “place well suited for fishing,” Kwegya was considered “the first fisherman” from whom “all the rest of the people of the Gold Coast acquired the knowledge of fishing in the sea.”Footnote 10 It was from the original inhabitants of Moree—the Etsii—that the Fante, who are largely credited with the expansion of sea fishing in the region, learned their trade.Footnote 11 Ga oral traditions tell that it was Fante fishers who taught them how to fish at sea. Prior to this, Ga and other coastal groups, including the Anlo in the region surrounding Keta Lagoon, had fished only in the calmer lagoons close to the coast.Footnote 12 These traditions recount that sea fishing in Ghana has long centred on the expansion and diffusion of fishing methods between different groups fishing along the coast.

The written accounts of Europeans voyaging to Ghana from the fifteenth century onwards are also filled with descriptions of the seagoing activities of coastal inhabitants, particularly among Fante and Ga communities. The most detailed accounts of fishing appear in the seventeenth-century accounts of Pieter de Marees and Wilhelm Johann Müller. Both describe nets made from “tree-bark, by beating long leaves… with a club, plaiting twine from the veins of the leaves, winding it on to a spindle and then preparing nets with large and small mesh.”Footnote 13 They also describe the use of hook and line, harpoons, and baskets.Footnote 14 These accounts also convey that fishers actively integrated materials made available through the expansion of Atlantic trade into their repertoires.Footnote 15 Müller mentions that European traders sold steel fishing hooks on the coast, while fishers also purchased European-manufactured sewing needles from which they fashioned more robust hooks for use with fishing gears constructed from indigenous materials.Footnote 16 By the eighteenth century, Akyeampong writes, a variety of set nets and purse-nets were used on the coast, together with hook and line and diverse forms of traps and dams.Footnote 17

In these early written accounts, fishers’ cultivated knowledge of fish behaviour is clearly recognised. De Marees and Müller explain that particular fishing methods were used to target different species depending on the season. De Marees describes that hook and line was used between January and March to catch small fish species “such as Whiting,” harpoons in April and May to catch “a kind of fish similar to the Ray,” hooks in June and August to catch “a lot of Fish not unlike Herring,” and nets in October and November to catch fish that are “like Pikes” and also fish that “from the outside looks like Salmon, but inside it is very white.”Footnote 18 Müller also states that nets were not utilised before the “lesser rainy season” in October as Bosompo—god of the sea, described as the “patron saint of the fisherman” by Müller—“does not like seeing this done and causes much harm on account of it.”Footnote 19 While this evidence is only indicative, such seasonal approaches speak to fishers’ long-term observations of spawning seasons and changing oceanic conditions. This aligns with the biannual coastal upwelling periods experienced in the Gulf of Guinea, which brings cool waters, nutrients, and higher concentrations of fish into nearshore waters at different times of the year.Footnote 20

While sea fishing was a male-dominated vocation in precolonial Ghana, women controlled processing and marketing once catches were landed. Following the difficult and labour-intensive task of processing, fish were sold in local and regional markets that linked fishing communities to surrounding villages and distant interior markets. These market spaces were also controlled by women.Footnote 21 This was commented on by de Marees who wrote “These women and Peasants’ wives, very often buy fish and carry it to towns in other Countries [in the interior] in order to make profit: thus the Fish caught in the Sea is carried well over 100 or 200 miles into the Interior.”Footnote 22 The expansion of Atlantic trade also provided new economic opportunities for fish traders through demand for fish to feed European sojourners, employees, mariners, and those they enslaved.Footnote 23

To control and restrict sea fishing activities, there were a series of long-established powers, privileges, and customs in place throughout the coast. One particularly prominent example that appears across various European accounts was fishers’ adherence to non-fishing days. Tuesday was the most frequently cited non-fishing day, which European observers described as a “Sabbath” among fishing communities.Footnote 24 Müller writes that it was believed “a great disaster would befall [fishermen] if they went to sea to fish” on a Tuesday.Footnote 25 This was also noted by Thomas Thompson, an eighteenth-century missionary, who wrote that “they keep [non-fishing days] so strictly, that even the Necessity of Hunger, in the scarcest Times, makes no Exception to their established Rule in this Particular.”Footnote 26 Although earlier accounts do not describe the punishment for non-compliance beyond fear of supranatural displeasure, Alfred Burton Ellis—a British major and colonial ethnographer stationed in the Gold Coast Colony in the nineteenth century—described that Akan fishermen who violated this rule were fined and their fish were cast into the sea.Footnote 27

Beyond non-fishing days, political and religious authorities also held forms of marine tenure, including the rights to control access to beaches, rivers, lagoons, and specific fishing grounds. In the case of rivers and lagoons, fishing was sometimes controlled through religious ceremonies that opened and closed fishing seasons. In the Korle lagoon in Accra, for example, fishing is permitted throughout the year except for two weeks in late July and August during the Homowo harvest festival, when a prohibition is imposed by the Korle Wulomo (priest) as a way of asking Korle, the guardian of the lagoon, to supply water and fish for the rest of the year.Footnote 28 With regards to beaches and sea fishing grounds, M. J. Field, writing in the colonial period, recognised that such rights were well established. When discussing the opening of a potential fishery station in Accra, Field warned:

These sites [the beaches surrounding Accra], or rather rights of fishing from these sites, are hereditarily owned. Certain fishing grounds belong by immemorial custom to certain individuals. Any violation of these and other customs would bring bitter opposition and possibly the wrecking of the whole scheme.Footnote 29

Unlike many of his peers who, as we shall see, often disregarded the informed concerns of fishers, Field recognised that these prohibitions “have a sound basis of knowledge and fishing wisdom (for instance the closing of the lagoon fishing enables fish to spawn in peace).” He declared that “in spite of their ‘heathen’ trappings,” these customs were “worth respecting.”Footnote 30

At the time of the declaration of the British Gold Coast Colony in 1874, then, fishers had long been experimenting with exogenous materials, adapting these to fit with existing fishing methods to improve their efficiency and durability. While doing so, fishing efforts remained subject to regulations enforced by political and religious authorities. There are no discussions of conflicts arising from the introduction of new fishing technologies and methods in the precolonial period, although it is possible that such conflicts did occur but escaped commentary within the written record. As these were integrated with indigenous fishing methods using nets made largely from indigenous materials, it is also possible that these did not prompt substantial levels of protest or concern. In the late nineteenth century, however, the introduction of whole new fishing technologies that threatened to replace existing nets triggered significant debates throughout the coast.

Debating Fishing Nets in the Gold Coast Colony

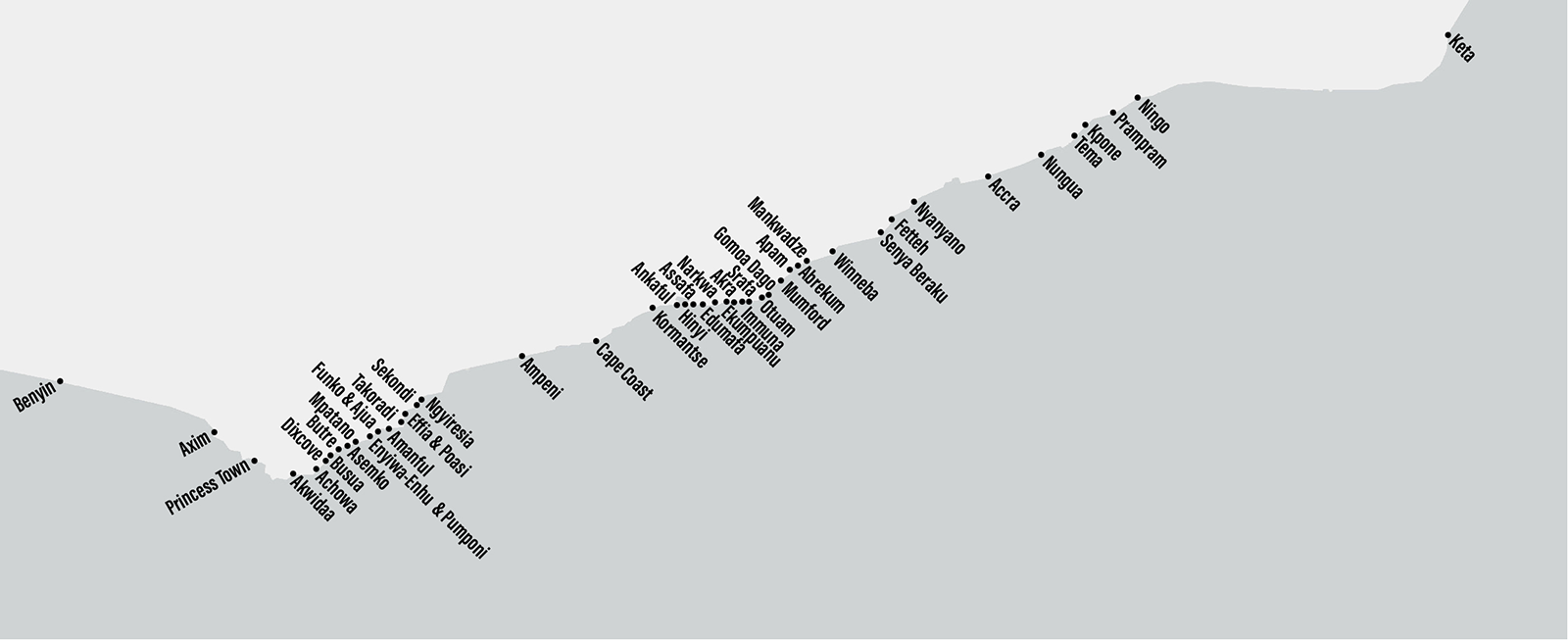

The invention and introduction of ali and yevudor nets marked a significant shift in fishing practices in the Gold Coast Colony from the final decade of the nineteenth century onwards. These were technological innovations driven by African entrepreneurs seeking more efficient and profitable fishing methods. Their use then ignited fierce divides within and between communities (see Fig. 2). Advocating for either their continued use or prohibition, fisheries participants debated the environmental and economic impacts of net adoption while tensions also arose surrounding migration, class, and jurisdiction over fishing activities. Viewed together, these were complex disputes driven by competing groups of fishers who held distinctive visions for the future of the fishing industry.

By all descriptions, ali and yevudor nets were considerably larger than existing nets in use on the coast. This meant they caught a significantly greater number of fish per haul than other nets. With smaller mesh sizes, these nets also caught much higher yields of juvenile fish. This was confirmed during a dispute between fishers from Abuadze and Shama in 1916, in which an ali net was measured and found to be 600 feet in length and 27 feet in width; this was compared to the other nets then in use with the longest measured at 130 by 7 feet.Footnote 31 Akyeampong suggests that ali nets could stretch between 700 and 1000 feet long.Footnote 32 The mesh was measured in 1901 and found to be of three-quarter inches.Footnote 33 The yevudor, meanwhile, was described in 1906 by a German missionary as “sixty to a hundred metres long, three to four feet wide and the middle has a sack (voku) that catches large and small fish.”Footnote 34 While the ali net was operated at sea by canoe, the yevudor was largely operated from shore.Footnote 35 These were new types of nets that were easily identified by their considerable size and the method of their use.

Although it was not until the last decade of the nineteenth century that disputes surrounding ali and yevudor nets began to appear in colonial reports and coastal newspapers, there are conflicting accounts as to when and where these were first introduced. In 1952, in an interview with Rowena Lawson, the chief fisherman in Accra claimed that Fante fishers had been using the ali net from the mid-nineteenth century and it was them who introduced the net to Ga fishers in 1870.Footnote 36 An alternate account is given in A. P. Brown’s history of the fishing industry at Labadi, written in the 1930s, which recounts that the ali net was first introduced at Nungua on the Ga coast in the 1890s by two half-brothers, Male Akro and Habel Nmai. Brown describes Akro as an innovator within the fishing industry, being the first to adopt European-manufactured twine—which he purchased in Accra in the early 1890s—for netting and rigging as opposed to rolling fibres from indigenous plants. Using manufactured twine, he then invented a bottom-net called the tengiraf at Teshie in the early 1890s; this initially caused protests and attempts at prohibition by the Teshie fishing community, but was later adopted by the opposing fishers. Next, Akro and Nmai travelled to Moledge, Nigeria, to labour as bricklayers, where they witnessed herring drift nets in use. On returning to Nungua, the brothers constructed the ali net in line with the drift nets they observed in Moledge. Brown’s account is supported by the narrative provided by Ga fishers before the British Supreme Court in 1898 during the first case surrounding ali nets. Martie Akrong, a fisher from Teshie, stated that he had first observed the ali net in use at nearby Nungua; he claimed to be the first to then make the net at Teshie.Footnote 37 Given that disputes did not arise until the 1890s and that these were centred first on Teshie before further conflicts arose along the coast over the next three decades, this latter account seems more feasible. The quick diffusion and fierce reactions to ali nets—including amongst Fante communities—would suggest that these were not in use before they were introduced at Nungua and Teshie in the 1890s (see Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1. Timeline of disputes surrounding fishing nets in the Gold Coast Colony, 1898–1923

When the yevudor came into use is less clear. The predominant account is that this was introduced on the Anlo coast surrounding Keta between the 1850s and 1870s by Afedima, a female entrepreneur. In an interview by Kraan in 2004, the chief fisherman of Woe explained “Mama Afedima went to Europe. She was taken there by a white, they married and she came back and brought the net with her.”Footnote 38 The fact that yevudor means “European net” or “white man’s net,” supports this account.Footnote 39 Prior to the introduction of the yevudor, Anlo fishers focused predominantly on fishing in Keta Lagoon as this proved safer than sea fishing, which required the navigation of the heavy surf and sand bar that endangered the approach to shore. Operated from the beach rather than further out at sea, the adoption of the yevudor by Anlo communities created new commercial opportunities without creating internal competition with other groups of sea fishers as occurred elsewhere. As Akyeampong has charted, Anlo fishers quickly carved out a niche in the sea fishing industry as experts in beach seine fishing.Footnote 40 As no reports of disputes surrounding beach seine fishing arose on the Anlo coast, it is possible that these nets could have been adopted much earlier than ali nets. It was only in the early twentieth century that disputes surrounding yevudor nets arose, especially as coastal erosion on the Anlo coast encouraged increasing numbers of Anlo fishers to migrate along the coast where they came into conflict with other sea fishing groups.Footnote 41

The Ga and Anlo coasts, then, were considerable open-air sites of fisheries-related experimentation, invention, and innovation in the latter half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 42 Here, fishers were innovating using different materials and inventing new nets to increase the efficiency and productivity of their efforts. These nets may have been based on designs influenced by European fishing methods, which had also spread to other coasts in the Gulf of Guinea, but their introduction and adoption in coastal Ghana was driven entirely by African entrepreneurs and innovators working within the fishing industry. As the nets spread and were adopted by different groups of fishers throughout the coast, debates then arose between net supporters and opposers (see Fig. 2).

Across the disputes arising within and between communities between 1898 and 1923 (see Table 1), those who opposed net adoption consistently claimed that their use threatened to ruin the industry. The chief fisherman of Teshie in 1898, Kwaoplanga Sowah, explained that most of the fishing community had adopted the ali net in 1897 after observing its efficiency. However, it was later found “to be of no use” as the large catches of herring gained by using the net for one day meant that for “2 or 3 or 4 weeks after you got no fish at all.” Consequently, it was determined that “the Alli net drives them [herring] away” so that the majority of Teshie fishers began opposing its use.Footnote 43 Other fishers at Teshie confirmed this, with Sowah Kudjo stating that the net “only brought starvation.”Footnote 44 This view was repeated throughout the twenty-five years of the disputes with frequent protestations of scarcities of fish in waters where the nets were deployed. There were also concerns about indiscriminate catches of juveniles, which led to considerable waste as they were “left to rot away in the sand.”Footnote 45 Without hard data, it is impossible to quantify the short- and long-term impact of these nets on fish stocks, although the frequent observations of decline and concerns over juveniles, particularly by fishers with deep knowledge of local conditions and breeding seasons, would suggest that such concerns were not unwarranted. The significantly higher yields of fish and, particularly, indiscriminate catches of juveniles could have created the conditions for instances of growth and recruitment overfishing.Footnote 46

Without discounting these anxieties, such environmental concerns were closely linked to apprehensions over the economic impact of the nets. This was the argument of net advocates who stated that concerns surrounding the impact of the nets on fish stocks were unwarranted. Instead, they suggested that opposition was driven by the high cost of the nets and the fact that greater yields intensified competition and caused a decline in prices per fish caught.Footnote 47 With regards to net costs, in 1898, Teshie fishers reported that an ali net cost £15 in comparison to “ordinary nets” that cost around 35 shillings.Footnote 48 In the 1930s, Brown reported that a home-made ali cost around £5–7 while imported nets cost £10–17; the cost of yevudor nets ranged from £20–£40.Footnote 49 These costs were paired with the need to recruit more labourers and purchase larger canoes to effectively deploy and work the nets.Footnote 50 As Vercruijsse has argued, the higher costs involved in deploying these nets led to changing labour relations within the fishing industry as net and canoe owners claimed greater shares of catches—two extra shares for the net and one for the canoe—than non-owner crewmembers. Over the long-term, this led to new class formations centred on hierarchies of owners and non-owners.Footnote 51

Even in the short-term, though, these nets offered to disrupt the economic status quo within fishing communities through their impact on prices per fish caught as well as the greater social mobility these offered for early adopters. Adjaytay Kofie, who employed the ali net at Teshie, explained that the cost of herrings was dependent on the volume of catch being landed on the beach. He had observed costs varying from three to twelve herring for 3d, which was confirmed by the testimonies of other Teshie fishers.Footnote 52 Across each fishing community, the adoption of larger nets that could land greater catches meant an impact on the total price per fish caught for all fishers who sold on the same beach to the waiting fish traders. This created even greater disparity between those using larger nets and those using smaller less efficient nets as the latter landed fewer fish and had to sell for the same price as those who landed much greater yields.Footnote 53 Moreover, as was explained in an article on ali nets in the Gold Coast Leader in 1916, “‘Ali’ became synonymous with ‘wealth’, for all ‘Ali’ fishermen became well-to-do.”Footnote 54 While net adopters often claimed that opposition was due to jealousy by those who could not afford the nets, in Teshie at least, most fishers appear to have had access to ali nets before choosing not to use them. Instead, those advocating for continued use of the nets in Teshie argued that the opposers sought to control markets in their favour, accusing the richer members of the community as being responsible for driving the prohibition.Footnote 55

New dimensions arose as conflicts developed between fishers from different communities. In 1903, a dispute arose between Tantum (Otuam) and Legu (Gomoa Dago) when Legu fishers began using ali nets in Tantum waters with Tantum fishers complaining that Legu fishers “caught more fish than Tantum did.”Footnote 56 Two years later, a riot ensued between Gomoah Fetteh and Cook’s Loaf after Cook’s Loaf fishers used the ali in Gomoah Fetteh waters.Footnote 57 Similar disputes emerged between neighbouring communities all along the coast with the same arguments surrounding impacts on fish stocks and markets being persistently raised by both sides. This also introduced questions surrounding the rights of coastal authorities to restrict net usage in waters proximate to their communities (see Fig. 2 and Table 1). This was further exacerbated by the arrival of migrant fishers who utilised the nets in waters where they had yet to be introduced or where they had been opposed previously. In 1909, a conflict between Kormantse and Saltpond arose when fish traders at Saltpond encouraged ali fishermen from Keta to fish in Kormantse waters.Footnote 58 Similarly, an anonymous letter in the Gold Coast Nation in 1916 reported on a long-running dispute between fishers in Shama and the nearby villages of Aboadze and Abuesi, which had previously been “barely inhabited” but had since become “quite welcome resting places” for inhabitants migrating from “places between Winnebah and Seccondee.” These migrants then adopted the ali net to the ire of nearby Shama fishers.Footnote 59

Fish traders—predominantly women—often played prominent roles within these disputes. Encouraged by the promise of larger catches at lesser prices, fish traders actively encouraged the adoption of larger and more efficient nets, often turning to migrant fishers to do so.Footnote 60 Their advocacy was further encouraged by the emergence of new transportation technologies that enabled quicker and more convenient transit of dried and salted fish to interior markets. On the coast surrounding Sekondi, the opening of the Sekondi-Kumasi railway from 1903 appeared to intensify disputes surrounding fishing nets as the railway enabled an expansion of existing connections with interior markets, particularly to provide cured fish for labourers in the mining regions.Footnote 61 The same anonymous letter that discussed the disputes surrounding Shama suggested that 80 percent of fish traffic between the coast around Sekondi and interior markets was contributed by the migrant fishers who had settled at Aboadze and Abuesi.Footnote 62 This was likely an exaggeration but it shows how the adoption of nets by neighbouring communities or resident migrants led to greater competition within local and regional markets. To meet increasing market demands and opportunities, fish traders actively encouraged the settlement and activities of migrant fishers, leading to further resentment and divisions within coastal communities.Footnote 63 In 1922, the asafo companies of Elmina—which were made up of several young fishing men—drove out sojourning Fante fishers, much to the protest of fish traders who claimed that there were not enough fishermen in Elmina to meet their demands.Footnote 64 The adoption of nets—whether by indigenous or migrant fishers—benefitted local fish traders while causing resentment among fishers who were not using the nets, whether out of choice or because they had yet to acquire them.

Across these disputes, arguments surrounding fish stocks, market prices, and migratory fishers were not mutually exclusive. Whether framed as concerns surrounding the long-term viability of the resource, the declining costs per fish caught, or the impact of greater competition on livelihoods, this was not a debate around the outright conservation of marine resources. Instead, fisheries participants on both sides acted as stewards of an economic-based system. Those who supported net adoption viewed these as enabling more productive and efficient fishing efforts, providing opportunities for social mobility despite the impact on fish prices. Those who opposed their use did so as they viewed these as being detrimental to the future of local fishing industries, whether by threatening fish stocks, markets, or livelihoods.Footnote 65 It is likely that opposition was driven by a mixture of all these concerns in which the economic impact of the nets on fish markets encouraged narratives of crisis to justify net restrictions. Such crisis narratives have largely been recognised within the context of colonial development schemes, in which African harvesting and cultivation practices were (erroneously) portrayed as excessively destructive in order to justify colonial assumptions of stewardship over colonised lands and resources.Footnote 66 In this case, though, crisis narratives were deployed by net opposers who claimed these nets either had caused or threatened to lead to declining fish stocks. While the significance of such observances should not be overlooked, neither should they be taken at face value without considering the potential of exaggeration to justify precautionary measures in the name of protecting the economic viability of the industry.

All along the coast, different groups of fishers became involved in these debates as they weighed up the benefits and drawbacks of the nets according to their own circumstances and observances, coming to different decisions surrounding their use.Footnote 67 In some cases, nets appear to have been adopted without contention (see Figs. 1 and 2). At other times, fishers using the nets were forcibly driven from fishing grounds, moving to different waters or returning to home waters when faced with repeated persecution.Footnote 68 Yet, the recurring disputes that arose surrounding the same nets in the same waters among the same communities demonstrates that this was a deeply contested issue, in which both sides were adamant in their views. To echo Jacob Dlamini’s assertion surrounding game reserves, there was no singular African attitude towards these nets but, instead, a diversity of debates and disputes arose around their adoption.Footnote 69 What is clear, though, is that ali and yevudor nets continued to be profitable even in the face of increasing tension. As they debated these issues, net advocates and opposers persistently turned to African and colonial authorities to advance their agendas.

Figure 1. Communities who had adopted the ali net by 1916.

Figure 2. Locations of disputes surrounding fishing nets in the Gold Coast Colony, 1898–1923.

Contesting Net Restrictions on the Coast

From the outset, net advocates and opposers solicited support from African and colonial authorities. Most commonly, fishers’ demands for net restrictions were backed by regional African authorities, leading to net bans in delineated coastal areas. Net advocates then turned to colonial forums to contest the legitimacy of restrictions and shift the debates in their favour. This was at a time when the colonial government was fundamentally disinterested in the coastal fishing industry and no information was being gathered surrounding the marine environment or resources.Footnote 70 Colonial adjudication, therefore, relied on how far the arguments advanced by either side aligned with colonial opinions surrounding fishing, fishing technologies, and the laws of the sea. The confluence between net supporters’ arguments and colonial views ensured that net supporters found ready allies within the British colonial apparatus. Yet, opposing fishers and their leaders persistently contested colonial decisions by continuing to challenge net adopters, encouraging yet further arbitration.

The first dispute to draw in African and colonial authorities occurred shortly after the introduction of the ali net at Nungua and Teshie. As discussed, in 1898 after experimenting with the ali net, a majority of Teshie fishers decided that it was detrimental to the industry. Kwaoplanga Sowah, the chief fisherman at Teshie, then called a meeting of fishers to state that the net should not be used. As there were no objections, a gong-gong was beaten about the town to confirm the establishment of the new law.Footnote 71 Shortly thereafter, five canoe crews went fishing with ali nets; many later claiming to have been out of town at the time of the declaration and unaware of the prohibition. Opposing fishers then swam out to meet the canoes on their return, capsizing the canoe to turn out the fish catch before confiscating the nets and canoes. Following this, the ali fishers refused to answer a summons taken out by the chief fisherman to account for their breaking the law. Instead, they travelled to Accra and hired Arthur Boi Quartey-Papafio, a prominent Ga lawyer educated in London, to bring their case before the British Supreme Court in Accra. In this case, the plaintiffs—the ali fishers—claimed damages from the defendants—those accused of undertaking or ordering the seizure—on the grounds that their actions were unlawful as the net restriction was illegitimate.Footnote 72

Presided over by Chief Justice William Brandford Griffith, the material issues as far as the Supreme Court was concerned was “whether there was a native law empowering the capsizing of the pl[ain]t[iff]s boats” and “whether the Supreme Court should enforce that law if it exists.”Footnote 73 To make the plaintiffs’ case, Quartey-Papafio argued that the consent of the Teshie mantse—the senior authority over the town—was required before the law could be considered in force. Called before the court, Teshie Mantse Nii Kotey declared he had not made or sanctioned a law prohibiting ali nets, asserting that “the fishermen dare not think of making a law without my sanctioning it.”Footnote 74 Chief Fisherman Sowah, however, stated that “a law which concerns the whole country is one which the king has to make, but not one which concerns any trade.”Footnote 75 Representing the defendants, Charles James Bannerman—also a Western-educated barrister based in Accra—focused on proving this point. Several witnesses attested to this, including the Ga Mantse Tackie Tawiah I who explained “members of a trade can make laws for their trades.” He explained he would only be made aware of the law if it was broken and a summons was taken out before him against the perpetrators. The process was such that, if the law was disobeyed, complaint was made first to the chief fisherman and then to the mantse or his second in command (referred to in the case as his “linguist”).Footnote 76 This had been done by the Teshie fishers, who complained about the ali fishers to Aboadyin, whose brother Ayeku was second in command at Teshie; Aboadyin undertook his brother’s duties when he was absent. After the ali fishers did not obey the summons before Sowah or Aboadyin, a summons was then taken out before the Ga mantse as the paramount authority in the Ga state. The ali fishers again disobeyed the summons, instead shifting the forum for the dispute to the Supreme Court.Footnote 77

While the lawyers focused on the question of whether the process followed by opposing Teshie fishers adhered to law within the Ga state, Chief Justice Griffith disregarded these as immaterial to his ruling. He declared “it is not necessary to consider … whether the fishermen had a right to make this law without the king’s consent [or] whether the law was validly made.”Footnote 78 Instead, the question was whether the restriction adhered to the relevant colonial ordinances that had been imposed over indigenous legal structures. In his judgement, Griffith referred to the Supreme Court Ordinance of 1876, which had created the British Supreme Court as the highest court in the colony. Section 19 of the ordinance stated that customary laws—that is to say, indigenous laws and customs—continued to apply to the extent that these were not “repugnant to natural justice, equity and good conscience.”Footnote 79 According to Griffith, this meant that only those laws and customs that existed when the ordinance was passed were recognised within the laws of the colony. As the ali net was not in use prior to 1876, Griffith judged it was a new law that could not be considered legitimate under the Supreme Court Ordinance.Footnote 80 Instead, this was subject to the Native Jurisdiction Ordinance of 1883, which empowered African authorities to make byelaws surrounding certain issues, including public fisheries as long as these were approved by the colonial government and published in the government gazette.Footnote 81 As the ali law had not been approved by the colonial government, the Supreme Court could not recognise its legitimacy. On this basis, the case was decided for the plaintiffs, who received damages from the defendants for the loss of their fish, canoes, nets, and other materials.Footnote 82

With this decision, Teshie ali fishers successfully challenged the restrictions on their activities. Through colonial mediation, the question shifted away from whether the chief fisherman had the authority to make the law without the Teshie mantse’s approval to instead focus on whether that restriction had received colonial approval. This effectively confirmed that any responses to newly arising issues by African authorities—such as restrictions on new fishing methods—would have to first gain approval through the colonial process or else they would be judged illegitimate within colonial forums. Following this ruling, there were several occasions where African authorities sought approval for byelaws to restrict ali, yevudor, and other fishing nets within their coastal expanses, citing the arguments of opposing fishers surrounding the impact on fish catches. While this approach was recommended on several occasions by district commissioners seeking to stem disputes in their districts, such byelaws were consistently rejected by the attorney general and secretary for native affairs of the Gold Coast Colony.Footnote 83 In 1905, on the suggestion of the attorney general, a decree was even circulated to district commissioners of seaboard districts ordering them to notify inhabitants of fishing villages that the governor would not interfere in the “free use of nets.”Footnote 84

In his judgement, Griffith had endorsed this approach, stating “if I thought for a moment that the use of Alli nets did tend to injure the fishing industry I should advise the defendants to apply to the Government to make legislation … but the Government would rather encourage than discourage the use of the ali ‘net.’”Footnote 85 Although his judgement was not based on this assessment, Griffith aligned with the views of net advocates that the nets did not negatively impacting fish stocks. This was a view, he declared, that “the experience of practically the whole civilized world [was] against.”Footnote 86 This sentiment was repeated frequently by colonial officials. In 1901, when a breach of peace was anticipated at Teshie surrounding the continued use of ali nets, the district commissioner of Accra advised that he did not believe use of the nets would impact on future fish supplies as the nets were “similar to that used for centuries round the English Coast.”Footnote 87 Two decades later, the colonial secretary of the Gold Coast Colony asserted “the best fishing net is the net that catches the most fish.”Footnote 88 This was not a universal view but had emerged in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century during similarly tense disputes surrounding fishing methods, particularly the introduction of heavy beam trawling using steam trawlers. A series of royal commissions suggested that the impact of fishing on fish stocks was insignificant, findings based more on conjecture and assumptions about the inexhaustibility of sea fisheries than any tangible evidence.Footnote 89 The perceptions surrounding the inexhaustibility of the sea that dominated British governance at the turn of the twentieth century then influenced colonial views surrounding fishing technologies in the Gold Coast Colony.

These conclusions, though, were also underpinned by deeply racialised views surrounding African fishing technologies and communities. Handbooks compiled in 1914 and 1916 to guide new district commissioners appointed to the Gold Coast Colony provided specific advice surrounding the fishing disputes. New district commissioners were advised that “The native … is foolishly conservative, and clings tenaciously to the customs of his fathers, detesting innovations.”Footnote 90 In line with this view, objections towards the nets were described by colonial officials as “frivolous,” “dictated by selfish motives,” and resulting from ignorance and an aversion to progress among fishing communities.Footnote 91 This was paired with views that the fishing nets in use—including ali and yevudor nets—were “on the whole still very primitive.”Footnote 92 These ideas continued into the 1920s, even when the idea of inexhaustible seas was being challenged in Britain.Footnote 93 In 1923, the district commissioner of the Central Province sought advice from the secretary for native affairs surrounding a byelaw restricting fishing nets that had been proposed by the omanhene of Winneba. When doing so, the district commissioner attached an article from the Over-Seas Daily Mail reporting on dwindling fish catches in Britain, questioning whether there may be some truth to the omanhene’s claims that the nets threatened the health of fish stocks. While agreeing that overexploitation of fish in Europe had led to fish “leaving certain coasts,” the secretary declared “I should not think there is any ground for alarm on the Gold Coast with the present extent and methods of fishing.”Footnote 94 Viewing the adoption of fishing technologies comparable to those utilised in Europe as a marker of progress, opposition to such technologies was repeatedly seen by colonial officials as evidence of the irrationality of resistant fishers and fishing communities, dismissing any other grounds for their objections out of hand.Footnote 95 As Michael Adas has argued, colonial officials were guided in their dismissal of African material achievement through the prevailing narratives of material superiority in Europe.Footnote 96 Through these opinions, colonial officials flattened the debates between fishers to that of progressive and conservative groups, entirely ignoring the active invention, innovation, experimentation, and observation that net advocates and opposers engaged in. Net adopters were then able to exploit colonial prejudices in support of their attempts to shut down debates and challenge restrictions on their activities.Footnote 97

Just as net adopters ardently resisted restrictions passed by coastal authorities, however, so too did opposing fishers and their leaders contest colonial decisions by continuing to vigorously challenge net adopters. In February 1900, just over a year after Griffith’s decision, a disturbance was reported at Teshie as fishers clashed over the continued use of ali nets. This then led to an agreement, this time with the backing of the Teshie mantse, to prohibit the ali net. Further use of the net then led Ga Mantse Tackie Tawiah I to order the destruction of all ali nets in his domain; this was again challenged in the colonial court.Footnote 98 A few years later, in response to complaints of ali fishers from Senya Beraku fishing in Winneba waters, the omanhene of Winneba passed a law prohibiting the use of the net, introducing a fine of £2 6d for offenders. It was reported that in less than a month, these fines amounted to £300 and it was only with increased persecutions that ali fishers were forced to return to their home waters.Footnote 99 Net users also faced seizures and public humiliations, such as in Teshie in 1898 when capsized ali fishers were pelted with fish as they returned to shore.Footnote 100 In Shama in 1916, ali fishers were seized and “taken through the town with their nets and surrounded by a large crowd of men, women and young people, they [were] hooted at and assaulted, the poor people being afterwards taken before the Chief and are fined £5 each canoe and sent away.”Footnote 101 The captors were said to receive £1 of each fine.Footnote 102 These disputes also erupted into violent assaults with fishers seeming to take matters into their own hands. In 1918, community members from Shama attempted to burn the nearby villages of Aboadze and Abuesi, where fishers were using ali nets. In the attempt, the attackers burned one house, damaged a number of canoes, and destroyed a number of fishing nets—the main focus of their ire.Footnote 103

Unable to contain the disputes through either court proceedings or legislative measures, which fishers from both sides repeatedly refused to adhere to, African and colonial authorities made frequent attempts to broker compromises between fishing communities. In these negotiations, British district commissioners were regularly solicited as arbitrators. Several agreements were mediated in which neighbouring communities agreed to only use ali nets in their own waters or in waters where their use was not objected to. In 1907, an imminent conflict between fishers of Kormantse and Saltpond surrounding Saltpond fishers using ali nets in Kormantse waters was halted with the erection of a cement pillar on the beach half way between the two communities, delineating the boundaries of each community’s fishing grounds.Footnote 104 Two years later, a meeting was called by the commissioner of the Central Province following continuing disputes, especially an attack on Kormantse fishers who had now adopted the nets and were deploying them in Anomabo waters. At this meeting, all coastal representatives—including leaders from Anomabo, Brewa, Cape Coast, and Moree—objected to the use of ali nets, except the omanhene of Kormantse whose people now found the nets profitable. It was agreed that Kormantse fishers would only use ali nets in their waters, so that if they “followed fish to other people’s waters,” they would “put away the ali net and use only cast net.”Footnote 105

Through this process, African leaders and British district commissioners improvised a reactive policy to stem tensions in their regions and mediate between opposing groups. Yet, even as cement pillars were being erected, colonial officials questioned their legality. At the meeting he called in 1910, the commissioner of the Central Province stated that boundary pillars could be used to stop disputes surrounding seine nets, as these were worked from the beach, but such boundaries “could not be fixed at sea which was common property.”Footnote 106 This aligned with prevailing arguments established in European natural law, in which the “high seas” was considered the common property of all mankind.Footnote 107 This, however, conflicted with the claims of African authorities over fishing activities occurring adjacent to their beaches. In favour of mediating agreements, the district commissioner pushed the issue aside; his successor reported in 1913 that the erection of pillars to fix the boundaries of ali net fishing had achieved satisfactory results.Footnote 108 Unwilling to officially sanction byelaws restricting fishing nets, the colonial government nevertheless supported arrangements that fixed the fishing boundaries of bordering communities. This was confirmed in 1916 by the governor of the Gold Coast Colony, Sir Hugh Clifford, who stated that each community should be allowed to decide for itself whether to adopt the nets within their “own territorial waters” while taking all reasonable precautions to prevent the nets from inconveniencing their neighbours. On the suggestion of the secretary for native affairs, it was also confirmed that the government would “not discountenance the legitimate use of the nets” when disputes arose between two sections of the same community. Instead, such cases would be judged “on their particular merits.”Footnote 109 This was a means to deter conflict between competing fishing communities while not discouraging the use or future adoption of the nets. Any conflicts arising among fishers within the same community would be arbitrated in colonial forums with judgments likely to favour net adopters. Even as the colonial government recognised the rights of fishing communities to restrict fishing practices in their proximate waters, colonial forums were preserved as a space where the legitimacy of such restrictions—and the authority of those who passed them—could continue to be questioned.

Just as restrictions were challenged in colonial forums by net adopters, African authorities and fishers who continued to restrict net use faced increasing pressure from net advocates and especially fish traders. In line with the arguments of Jennifer Hart, Osborn, and Laura Ann Twagira, women were not only active participants who helped to drive the introduction of new fishing technologies but they were also active lobbyists across colonial and indigenous forums in the pursuit of greater prosperity and opportunity.Footnote 110 A clear example of this surrounds the adoption of the ali net in Winneba in the early twentieth century following its introduction at Senya Beraku. As discussed, ali fishers from Senya Beraku who attempted to fish in Winneba waters faced fines imposed by the omanhene of Winneba, which encouraged them to return to Senya Beraku waters. When they did so, Winneba fish traders began travelling to Senya Beraku to take advantage of the greater yields and competitive prices offered by ali fishers. On arriving in Senya Beraku, however, Winneba fish traders began encountering customers who had formerly visited Winneba to buy fish but who were now also travelling to Senya Beraku instead. Concerned of trade being diverted away from their home markets, Winneba fish traders revolted against the omanhene, forcing him to withdraw net restrictions and permit any fishers—indigenous or settler—to use the ali net. Importantly, around this same time, the omanhene’s byelaw restricting the ali net was also rejected by the colonial government.Footnote 111 When coastal leaders did not adhere to fish traders’ wishes, fish traders were also willing to lobby colonial officials instead. This was evident in 1922 when the omanhene of Elmina supported the removal of Fante fishers from Elmina. After appealing several times to the omanhene against the decision, the fish traders of Elmina then submitted a petition to the district commissioner, requesting that foreign fishermen be permitted to resume their work as the number of fishermen in Elmina was “insufficient to meet our large demand.”Footnote 112

The involvement of fish traders in these disputes led to increased pressure on African authorities to permit the use of the nets. Importantly, traders’ active encouragement of migrant fishers also offered additional sources of income for coastal authorities through the levying of amandzi, a special toll that migrant fishers had to pay for the rights to settle in and use the landing sites of communities.Footnote 113 At the time of these disputes, amandzi fees appear to have cost approximately £5 per settler, which was paid directly to the authorities who held the rights over the land.Footnote 114 In their petition to the district commissioner, Elmina fish traders made sure to highlight that tolls collected from foreign fishers for just one season had raised over £300. This revenue had then been used to cover various costs, including debts accumulated by the omanhene and the annual Edina Bakatue festival that opened the Benya Lagoon for the fishing season.Footnote 115 As Vercruijsse has stated, fish traders’ encouragement of foreign fishermen willing to use these nets was another means to manipulate African authorities to permit these practices in spite of local opposition.Footnote 116 This was at a time when there were limited sources of income for coastal leaders, partly because colonial courts provided an alternative and cheaper source of dispute resolution than customary courts, which had been important sources of revenue previously.Footnote 117 Consequently, the additional revenue offered through amandzi was hard for coastal authorities to forgo, especially when facing pressure from net advocates.

By the 1920s, disputes surrounding the ali and yevudor nets had subsided and the nets were in frequent use all along the coast, including in areas where fishers and coastal authorities had formerly opposed their adoption (see Figs. 1 and 2). By this time, it appears that net advocates had successfully contested those who cautioned against their use. To do so, they had strategically navigated African and colonial processes, questioning the basis for net restrictions, while pressuring opposing fishers and authorities into acquiescence. This was despite the continuing concerns over the impacts of the nets. In 1923, Nana Ayirebi Acquah III, the omanhene of Winneba, wrote “The Colony is much poorer in Sea fish supply than it was 30 years ago, and it is believed that the cause is due to the use of certain objectionable Nets which unnecessarily deplete our foreshore stock of fishes.” Yet, when making this statement, Acquah was not making the case for restrictions against ali and yevudor nets but was instead seeking approval for a byelaw against three newly invented nets recently adopted at Winneba. Acquah purposefully distinguished these restrictions from the “the old famous general dispute among our Fishermen with regard to the use of the ali Net.” Still, the byelaw echoed arguments from earlier debates that use of the nets “would result in scarcity of fishes in our waters” and an “unnatural depletion of sea stock.” Despite Acquah’s attempt to distance this restriction from previous byelaws, he had to withdraw it after the secretary for native affairs advised that this would be considered in accordance with the judgements made during the former disputes.Footnote 118

As the 1923 byelaw demonstrates, fishing communities continued to invent and innovate new fishing nets and methods, even as decades of disputes about these technologies rolled on. For its part, the colonial government continued to passively support such innovations through the rejection of restrictive byelaws, even as some African authorities and fishers advised caution. While the debates around ali and yevudor nets essentially petered out as the nets were gradually adopted throughout the coast, this was a process in which African authorities and colonial officials had been pulled into debates surrounding the future of the fishing industry through the active solicitation, activities, and pressure of fishers. Despite the omanhene of Winneba’s pronouncement that “There is no Industry in this world without some natural laws or other regulations prompted by local circumstances,” the ability of opposing fishers and coastal leaders to respond to the introduction of new fishing gears and methods by adopting precautionary measures was effectively undermined by the manoeuvring of net advocates using the alternative legal avenues opened through colonial rule.Footnote 119 In the process, the perspectives of a significant portion of the fishing community who cautioned against the wholesale adoption of more productive nets became marginalised while the jurisdiction and powers of African authorities to regulate fishing activities were persistently questioned and challenged within colonial forums and throughout coastal towns.

Conclusion

Given their productivity and the active support of fish traders as well as the revenue generated from amandzi, it could be suggested that it was inevitable that ali and yevudor nets would have spread throughout the coast. The tide perhaps had already turned after several communities adopted the net at the turn of the twentieth century. This was driven by the greater catches experienced by fishers and the resultant support of fish traders who gained access to more fish at lesser prices. After these nets were adopted by neighbouring communities or by fishers within the same community, this then encouraged other communities and fishers to adopt them, prompted either by their productivity or the need to remain competitive in the face of diminishing costs per fish caught. This happened frequently throughout the coast where those who initially opposed the nets then adopted them (see Table 1, and Figs. 1 and 2). This could be interpreted as a classic example of Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” in which fishers were inevitably motivated to utilise those methods that returned the greatest yields in competition with other fishers, thereby lending credence to the notion that the best net is the net that catches the most fish.Footnote 120 As Peter Jones has noted with regards to failed attempts to curb the use of bottom trawls in British waters, such methods were “simply too productive and far too profitable” to suppress effectively.Footnote 121 This would mean that the introduction of nets by some community members was inevitable as was their later adoption by the rest of the fishing population. This was, seemingly, what occurred time and time again in the Gold Coast Colony.

Such an interpretation, however, would ignore twenty-five years of invention, experimentation, and disputes that featured sustained attempts to halt the perceived impact of these nets despite their increased efficiency by opposing fishers and authorities. This firmly situates fishing within the ever-increasing range of industries in Africa that scholars have studied that continued as vibrant sites of technological and environmental improvisation and debate before, during, and following colonial occupation. In the early twentieth-century Gold Coast Colony, fishers introduced and engaged with new and adapted fishing technologies on their own terms, choosing where, when, and how to bring these into their repertoire of fishing activities. Views on these technologies, however, were not homogenous. Instead, disputes surrounding the nets were made and remade through the active choices and strategizing of those who supported and opposed their adoption for a variety of reasons. Rather than simply a result of the efficiency and profitability of the new nets, the outcomes of these debates were contingent on the effective manoeuvring of net advocates who navigated African and colonial hierarchies to gradually encourage and pressure opposing groups into accession. Women fish traders played a critical role in this, recognising the benefits that these nets brought through greater yields and lower prices, especially when paired with new transportation opportunities. Collectively, these fishing technologies, the debates they stimulated, and the strategic manoeuvring of opposing groups were all firmly part of what Mavhunga has called the “everyday innovation” arising within sites of production in Africa.Footnote 122

Yet, even as these disputes arose far and apart from any colonial attempts to interfere in the fishing industry, the colonial context is crucial to understanding the process and outcome of the debates. Even as colonial engagement proved entirely reactive, it was through colonial decisions—supported by the ill-informed views of colonial arbitrators—that laws passed by African authorities were consistently challenged and overturned. Still, colonial decisions did not create these disputes or bring them to an end, nor was it the colonial state who actively policed or enforced these verdicts. Despite the Supreme Court ruling in 1898 and subsequent interventions by colonial officials, African authorities continued to pass restrictions, levy fines, and sanction confiscations of fishing equipment. Likewise, fishers who opposed the nets continued to seize and destroy equipment while driving net users from their fishing grounds, thereby forcing colonial and African authorities into repeated rounds of negotiation and compromise. That colonial officials questioned the legalities of such compromises—such as boundary posts—yet upheld them in practice speaks to the limits of colonial power to impose and enforce unilateral decisions onto African practices and industries. The relative flexibility of colonial officials—both at district and executive levels—in responding to these conflicts over time reflects their own acknowledgement of such limitations. Crucially, it was the actions of competing fisher groups—who strategically mobilised different forums and authorities in response to technologies that fishers themselves introduced and innovated along the coast—that shaped the origins and outcomes of these conflicts. This reflects broader patterns identified by scholars across different contexts and industries, in which colonial occupation created new avenues and opportunities for different sectors of the population to advance their interests against competing groups.Footnote 123 In this case, fishers advanced their visions for the future of the fishing industry based on the use of new technological innovations while contesting those who disputed this vision.

In the process, however, colonial arbitration was initiated within the realm of fisheries for the first time, entangling the future of the industry with the legal determinations of a colonial regime that challenged—but did not eradicate—the authority of African powers within the marine space. This ensured that African authorities could no longer independently regulate fisheries as they now had to contend with colonial forums and laws that, at this time, unequivocally favoured the uncritical adoption of new fishing technologies. As occurred on land, the resulting ambiguous and indefinite legal boundaries would have profound consequences for the fishing industry well into the future.Footnote 124

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editor and anonymous peer reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this work. Their suggestions have significantly strengthened this piece in every way. The author would also like to express their gratitude and appreciation to colleagues who provided feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript, including colleagues from One Ocean Hub and the University of Strathclyde Humanities Work-in-Progress group. Special thanks to James Bell, whose perspectives and comments surrounding fishing gears were especially helpful. This research was supported by the One Ocean Hub, a collaborative research program for sustainable development funded by United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) (Grant Ref: NE/S008950/1).