Highlights

-

In 42 CUPS patients, DaTscan results changed management in 31% (95% CI: 18–47%).

-

Change was significantly more likely after a normal scan (60%) than an abnormal scan (15%) (p = 0.009).

-

Normal scans primarily guided discontinuation of dopaminergic therapy.

Introduction

A clinical diagnosis of a parkinsonian syndrome (PS) requires the presence of bradykinesia along with at least one other cardinal symptom, such as tremor or rigidity. Reference Postuma, Berg and Stern1 In PS with a dopaminergic deficit, like idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD), the characteristic motor signs and symptoms manifest only after the degenerative process is well-established. Reference Postuma and Berg2,Reference Greffard, Verny and Bonnet3 Other forms of PS, such as essential tremor (ET), drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) and vascular parkinsonism (VP), lack dopaminergic deficits but can present with clinical features similar to PD. Reference Kägi, Bhatia and Tolosa4,Reference Vlaar, de Nijs and Kessels5 Diagnosing PS in its early stages can be challenging, especially when symptoms are not fully developed or when patients exhibit atypical features. Reference Rajput, Rozdilsky and Rajput6,Reference Newman, Breen, Patterson, Hadley, Grosset and Grosset7

This diagnostic uncertainty, termed clinically uncertain parkinsonian syndromes (CUPS), Reference Kupsch, Bajaj and Weiland8,Reference Catafau and Tolosa9 is a significant clinical problem. Meta-analyses, including a comprehensive review by Rizzo and colleagues, demonstrate that misdiagnosis rates can be as high as 20% even among movement disorder specialists. Reference Rizzo, Copetti, Arcuti, Martino, Fontana and Logroscino10 An incorrect or delayed diagnosis profoundly impacts patient prognosis, mental health and therapeutic management, often leading to the prescription of inappropriate or unnecessary medications. Reference Sadasivan and Friedman11

Dopamine transporter (DaT) single-photon emission CT (SPECT) imaging, or DaTscan, is a valuable tool that addresses this challenge. The [123I]Ioflupane radiopharmaceutical binds presynaptic DaTs, enabling visualization of dopaminergic system integrity. Reference Hauser and Grosset12 A normal scan, showing intact transporters, helps to rule out a diagnosis of PD and supports a diagnosis of ET, DIP or VP. Reference Catafau and Tolosa9 An abnormal scan confirms a dopaminergic deficit, consistent with PD or other forms of neurodegenerative PS. Reference Hauser and Grosset12 DaTscan has been found to have a sensitivity of up to 90% and a specificity of up to 92% in differentiating neurodegenerative and non-neurodegenerative PS. Reference Brigo, Matinella, Erro and Tinazzi13,Reference Benamer, Patterson and Grosset14

Previous studies have confirmed that DaTscan has a substantial impact on clinical practice. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Bega and colleagues, for instance, found that DaTscan results influenced patient management in approximately 54% of cases and led to a change in diagnosis in 31% of patients. Reference Bega, Kuo and Chalkidou15 Similarly, a large, prospective, controlled study by Kupsch et al. demonstrated that patients in the imaging group had significantly greater changes in both clinical management and diagnosis than those in the non-imaging control group. Reference Kupsch, Bajaj and Weiland8

Despite its approval in Europe (2000) and the United States (2011), DaTscan was approved by Health Canada only in 2018. 16 A critical distinction in the Canadian context is that the scan is not covered by provincial insurance plans, making it an out-of-pocket expense for patients. Reference Vu and Horton17 Canadian Guidelines for Parkinson’s Disease recommend considering a DaTscan when clinical uncertainty persists. Reference Grimes, Fitzpatrick and Gordon18 However, due to its cost and lack of funding, there is a distinct lack of published data on its real-world utilization and impact within the Canadian healthcare system.

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of DaTscan results on clinical management of patients with CUPS within a Canadian tertiary-care movement disorder service. This information could indicate whether offering funded DaTscan access to movement disorders specialists who often see these patients in consultation would enhance patient care for this intricate patient group.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective study conducted at the Movement Disorder Clinic of London Health Sciences Centre, a tertiary hospital in London, Ontario, Canada. DaTscans were performed at the Nuclear Medicine Department, Brant Community Healthcare System, Brantford, Ontario. Patients paid for all scans out of their own funds.

Patients

Patients with CUPS who were referred for a DaTscan between January 1, 2020, and September 30, 2025, were recruited for the study. The Western University Health Science Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol (#127455).

Data collection

A retrospective chart review was performed using the hospital’s electronic medical records system. Data collected included basic demographic and clinical data: age at DaTscan, sex, duration of symptoms, presence of cardinal parkinsonian symptoms (tremor, bradykinesia and rigidity) and history of exposure to neuroleptics.

Patients were categorized into one of three pre-DaT diagnostic groups based on the clinical presentation: (1) Atypically long-standing PD with features like mild clinical signs, non-progression of clinical features and small levodopa requirement. (2) Secondary parkinsonism (SP), specified as either DIP or VP; (3) tremor syndrome (TS), specified as “ET Plus” with subtle bradykinesia or rigidity; isolated parkinsonian tremor (PT) without bradykinesia; or dystonic tremor (DT).

DaTscan acquisition and processing

Brain SPECT imaging was performed using a standardized protocol. Patients received a single intravenous injection of [123I]Ioflupane. One hour before the injection, oral Lugol’s iodine solution was administered to protect the thyroid. Image acquisition commenced 3 to 4 hours post-injection. Scans were acquired using a dual-head gamma camera (Discovery D670, GE Healthcare) equipped with low-energy, high-resolution collimators.

Images were obtained in a step-and-shoot mode (angular step of 3°, 30 seconds/step, rotation coverage 360°) with a matrix size of 128 × 128, at 1.25× zoom. Pixel size was 3.53 mm. Images were reconstructed using the GE Brain SPECT volumetrix programs with OSEM Iterative reconstruction and Chang’s attenuation correction and Butterworth filtering. No scatter correction was made.

The official DaTscan report from the Nuclear Medicine physician was categorized as “Abnormal” (positive scan, indicative of a dopaminergic deficit) or “Normal” (negative scan).

Outcome

The primary outcome was “Change in Management.” This was assessed from follow-up visit notes and defined as “Present” if a new medication was initiated, pre-DaT medications were discontinued or both. The outcome was defined as “Absent” if patients were explicitly continued on their pre-DaT medications. Post-DaT diagnoses and specific medication changes were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables with skewed distributions (age, duration of symptoms) were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The proportion of patients with a “Change in Management” was reported as a percentage with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

The association between “DaT Report” and “Change in Management” was assessed using Fisher’s Exact test. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

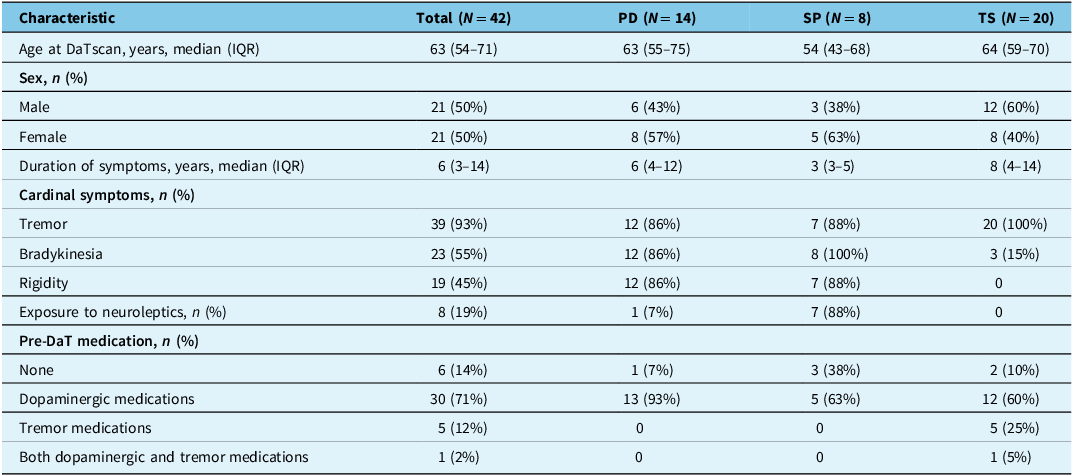

A total of 42 patients with CUPS who underwent a DaTscan were included in the analysis. The cohort was divided into three pre-DaT diagnostic groups: PD (n = 14, 33%), SP (n = 8, 19%) and TS (n = 20, 48%). Within the SP group, seven cases (88%) were suspected DIP and one case (13%) was suspected VP. The TS group was comprised of nine cases (45%) of PT, nine cases (45%) of ET Plus and two cases (10%) of DT. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the total cohort and by diagnostic group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by pre-DaTscan diagnosis (N = 42)

Note: DaT = dopamine transporter; IQR = interquartile range; N = total number of patients; n = number of patients in subgroup; PD = Parkinson’s disease; SP = secondary parkinsonism; TS = tremor syndromes.

Overall, the median age at the time of the scan was 63 years (IQR: 54–71), and the cohort was evenly split by sex, with 21 males (50%) and 21 females (50%). The “PD” group (median age 63) and “TS” group (median age 64) were of similar age, while the “SP” group was younger (median age 54).

The median duration of symptoms for the entire cohort was 6 years (IQR: 3–14). The SP group had the shortest median symptom duration (3 years), while the TS group had the longest (8 years).

Clinical symptom presentation varied significantly between the groups. Tremor was the most common symptom overall (39/42, 93%). Exposure to neuroleptic medications was reported in eight patients (19%).

Before the scan, 71% (30/42) of all patients were already taking dopaminergic medications, including 93% (13/14) of the PD group and 60% (12/20) of the TS group.

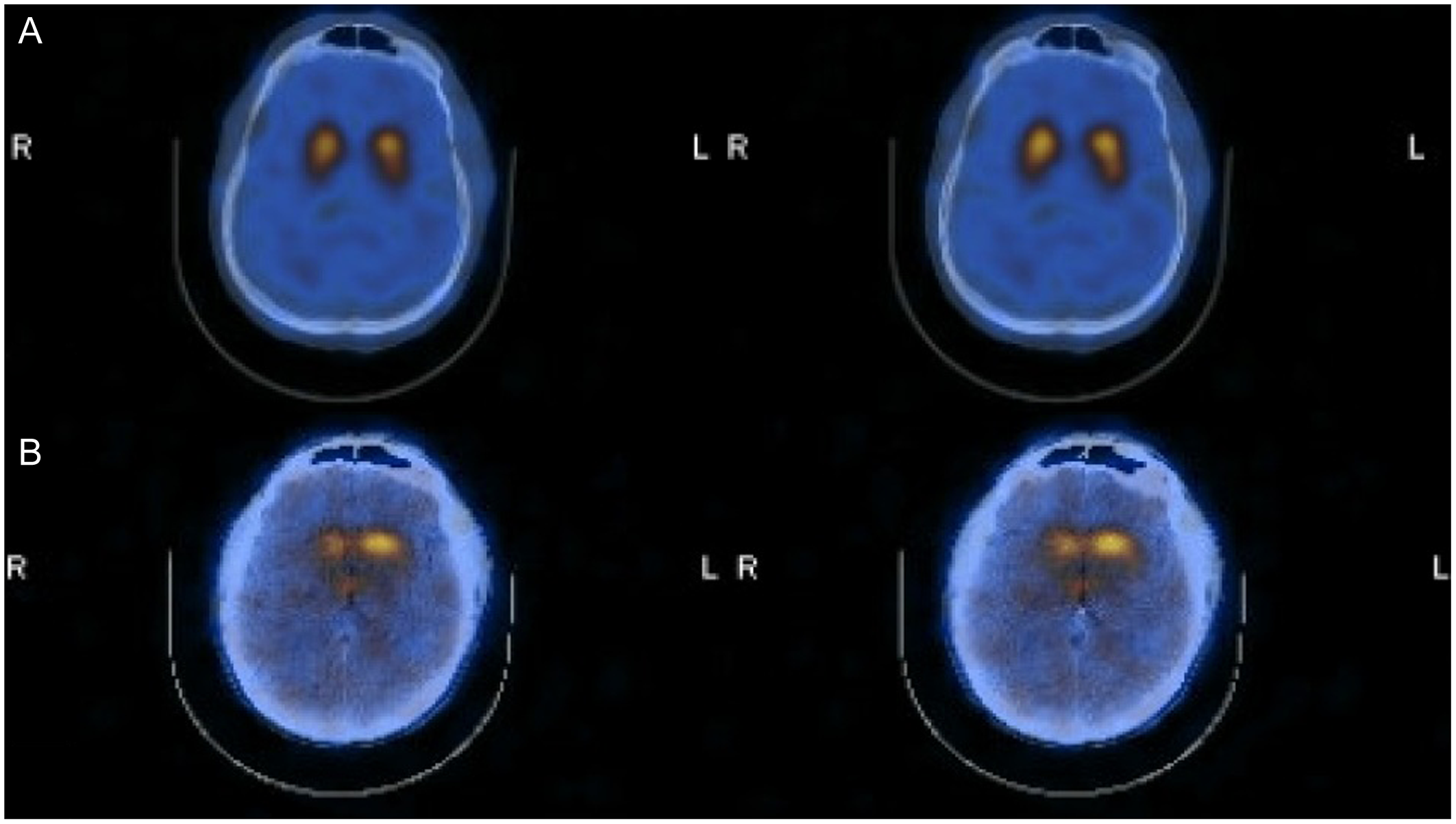

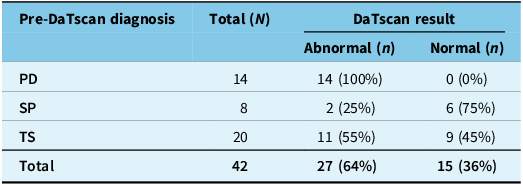

DaTscan results

Overall, 27 of the 42 DaTscans (64%) were reported as “Abnormal,” and 15 (36%) were reported as “Normal.” Representative images of Normal and Abnormal DaTscans are shown in Figure 1. The distribution of these results by pre-DaT diagnosis is shown in Table 2. All 14 patients (100%) with a pre-DaT diagnosis of “PD” had an abnormal scan. In contrast, six of eight patients (75%) with “SP” had a normal scan. The “TS” group was mixed, with 11 patients (55%) having an abnormal scan and 9 (45%) having a normal scan.

Figure 1. Representative DaTscan images. Top row (Normal): Displays symmetrical, intense radiotracer uptake in the striatum with a characteristic “comma” shape, indicating preserved presynaptic dopamine transporters in both the caudate and putamen. This pattern supports a non-neurodegenerative diagnosis (e.g., essential tremor). Bottom row (Abnormal): Displays reduced uptake, particularly in the putamen (posterior striatum), resulting in a “period” or circular appearance. This loss of the “comma” tail indicates a presynaptic dopaminergic deficit consistent with neurodegenerative parkinsonism (e.g., Parkinson’s disease). Note: DaT = dopamine transporter.

Table 2. DaTscan results by pre-DaTscan diagnosis

Note: DaT = dopamine transporter; N = total number of patients; n = number of patients in subgroup; PD = Parkinson’s disease; SP = secondary parkinsonism; TS = tremor syndromes.

After the DaTscan results were reviewed, the final post-DaT diagnoses were: PD (27/42, 64%), ET (8/42, 19%), DIP (6/42, 14%) and DT (1/42, 2%).

Impact on Clinical Management

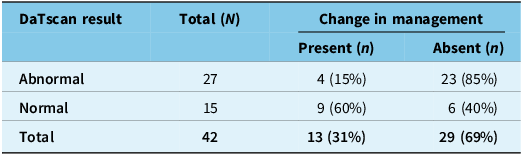

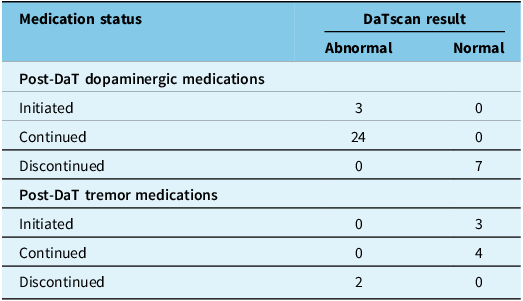

A “Change in Management” was observed in 13 of the 42 patients (31%, 95% CI: 18% to 47%). Overall, 27 patients (64%) were on dopaminergic medications following their DaTscan; three were newly initiated and 24 continued. Seven patients discontinued their dopaminergic medications. For tremor medications, seven patients (17%) were on treatment post-scan; three were newly initiated and four continued, while two discontinued their tremor medication.

The association between the DaTscan result and “Change in Management” is presented in Table 3. A management change occurred in 9 of 15 patients (60%) who had a normal DaTscan. In comparison, a change occurred in 4 of 27 patients (15%) with abnormal DaTscan results. Using Fisher’s Exact test, a statistically significant association was found between the DaTscan result and Change in Management (p = 0.009).

Table 3. Association between DaTscan results and change in management

Note: DaT = dopamine transporter; N = total number of patients; n = number of patients in subgroup. Fisher’s Exact Test p = 0.009.

The nature of the management change was dependent on the scan result, as detailed in Table 4. Of the four patients with an abnormal scan who had their management changed, two involved initiating dopaminergic therapy. In the third patient, dopaminergic treatment was continued, and tremor medication was discontinued. In the fourth patient, dopaminergic treatment was initiated, and tremor medication was discontinued. Of the nine patients with a normal scan who had their management changed, six involved discontinuation of dopaminergic medications, and two involved initiation of tremor medication. In the ninth patient, dopaminergic therapy was discontinued, and tremor medication was initiated.

Table 4. Post-DaTscan medication status by DaTscan results

Note: DaT = dopamine transporter; N = total number of patients.

Overall, 27 patients (64%) were on dopaminergic medications following their DaTscan; this included three patients who initiated therapy and 24 who continued. Seven patients discontinued their dopaminergic medications. For tremor medications, seven patients (17%) were on treatment post-scan; three initiated therapy and four continued, while two discontinued their tremor medication.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of 42 Canadian patients with CUPS, we found that DaTscan results led to a change in clinical management in 31% of all cases. Crucially, there is a statistically significant association between the scan result and the decision to alter management (p = 0.009). A change in therapy was far more likely after a normal scan (60% of cases) than after an abnormal scan (15% of cases). In a specialist clinic, DaTscan’s primary role is to provide conclusive evidence to determine the presence or absence of a dopaminergic deficit, which then guides patient care.

Our overall finding of a 31% management change rate is lower than the 54% reported in the Bega et al. meta-analysis and the 41–50% reported in the Kupsch et al. prospective trial. Reference Kupsch, Bajaj and Weiland8,Reference Bega, Kuo and Chalkidou15 These studies were conducted in a general neurology setting. The specialized setting of our study may explain the discrepancy.

The most important finding of our study is the strong association between the DaTscan result and the likelihood of a management change. An abnormal result typically confirms the clinical suspicion of PD, leading to the logical next step of continuing dopaminergic therapy and discontinuing tremor medications. Conversely, a normal scan led to a change in patient management for 60% of individuals, highlighting the scan’s significant ability to disprove diagnoses, leading to discontinuation of dopaminergic therapy or initiation of new tremor-specific medications. This finding clearly defines the scan’s clinical utility: it provides the objective evidence needed to withdraw unnecessary dopaminergic medications confidently and, in many cases, pivot to a more appropriate treatment. This aligns with observations from Oravivattanakul et al., who highlighted the challenge of patients with normal scans remaining on dopaminergic medications. Reference Oravivattanakul, Benchaya and Wu19

Our data also support the utility of the scan in resolving diagnostic ambiguity within specific CUPS subgroups. The scan demonstrated clear utility in the SP group, where 75% of results were normal, supporting the pre-scan diagnosis of DIP or VP. It was most valuable in the heterogeneous TS group, which was evenly split between abnormal (55%) and normal (45%) results, effectively differentiating patients with PD from those with ET or Dystonic tremor.

There are several limitations to this study. First, its retrospective, single-center design and small sample size (N = 42) limit the generalizability of our findings. Although we found a statistically significant association, a larger sample would provide greater statistical power and more precise estimates. Second, we did not collect systematic data on the duration of follow-up or disease progression post-scan, which would be necessary to validate the long-term accuracy of the post-DaT diagnosis. Finally, the “out-of-pocket” cost of the DaTscan in the Canadian system introduces a significant selection bias. Patients who are willing and able to pay for the scan may represent a unique cohort, with higher motivation for a definitive diagnosis or having failed previous empirical therapies.

Conclusions

This is the first study to investigate the real-world impact of DaTscan on clinical management within a Canadian Movement Disorder Clinic. We found that DaTscan results prompted a change in management in 31% of CUPS patients, and this change was significantly associated with the scan result. It justified initiating dopaminergic therapy after an abnormal scan and, more critically, supplied the definitive evidence needed to withdraw unnecessary dopaminergic therapy after a normal scan.

The lack of public funding for DaTscan in Canada remains a significant barrier to access. Our data suggest that targeted use of DaTscan in patients with CUPS provides substantial clinical utility by clarifying diagnosis and preventing inappropriate, costly long-term medication use. Further prospective, multi-center studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to formally evaluate the scan’s cost-effectiveness within the context of the Canadian healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

MJ was responsible for the study’s conceptualization and contributed to the writing (review and editing). AMM was responsible for data curation, formal analysis and writing the original draft. COB contributed to the writing (review and editing) of the manuscript.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

None.