The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease Hypothesis (DOHaD) proposes that adverse perinatal experiences increase the risk for later psychopathology (Doyle & Cicchetti, Reference Doyle and Cicchetti2018; Hanson & Gluckman, Reference Hanson and Gluckman2008). Negative affectivity refers to temperament dimensions marked by a tendency to experience negative emotions or emotional distress (Rothbart & Bates, Reference Rothbart, Bates, Damon and Lerner2007). Greater negative affectivity is a predictor of future child psychopathology, such as externalizing and internalizing problems (Nigg, Reference Nigg2006). Perinatal complications, or a composite of pregnancy-related complications, encompassing maternal illness, traumatic events during pregnancy, obstetric complications, and infant birth weight (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Velez, Brook and Smith1989; Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, McGee and Silva1991), have been found to predict children’s negative affectivity as well as externalizing and internalizing problems (e.g., Barroso et al., Reference Barroso, Hartley, Bagner and Pettit2015; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lähdepuro, Tuovinen, Girchenko, Rantalainen, Heinonen, Lahti, Räikkönen and Lahti-Pulkkinen2021; Rouse & Goodman, Reference Rouse and Goodman2014; Shuffrey et al., Reference Shuffrey, Morales, Jacobson, Bosquet Enlow, Ghassabian, Margolis, Lucchini, Carroll, Crum, Dabelea, Deutsch, Fifer, Goldson, Hockett, Mason, Jacobson, O’Connor, Pini and Rayport2023). Moreover, it has been proposed that negative affectivity may serve a key role in the developmental pathway from early perinatal risk to later internalizing problems (Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Morales, Metcalf and Pérez-Edgar2019). Given negative affectivity predicts other forms of psychopathology (e.g., externalizing problems) and the comorbidity of different disorders (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Fisher, Danese and Moffitt2023), we examined negative affectivity’s role in the developmental pathway to broader psychopathology. In addition, most existing studies examining the effects of perinatal complications and temperament have been conducted in mostly young (i.e., early to middle childhood), homogenous, and relatively small samples. Thus, we examined longitudinal relations among perinatal complications, children’s negative affectivity, and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems and general psychopathology problems in a large, diverse sample assessed from pregnancy to 17 years.

Perinatal complications are related to children’s socioemotional outcomes

Perinatal complications, including both maternal and neonatal complications, have been established within the DOHaD framework as significant contributors to children’s developmental trajectories, such as their temperament and risk for mental health problems (Doyle & Cicchetti, Reference Doyle and Cicchetti2018). In particular, maternal psychological distress during pregnancy may shape child development by impacting fetal brain development through various pathways, including hormonal influences, changes in placental functioning and perfusion, and epigenetic changes (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Austin, Knapp, Vaiano and Galbally2015; Monk et al., Reference Monk, Lugo-Candelas and Trumpff2019). Maternal depression during pregnancy has been found to positively predict infant negative affectivity (Rouse & Goodman, Reference Rouse and Goodman2014). In addition, pregnancy cardiometabolic complications, including gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, have been associated with infant difficult temperament (i.e., higher intensity and negative mood, and lower approach, adaptability, and rhythmicity) (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Oddy, Whitehouse, Pennell, Kendall, McLean, Jacoby, Zubrick, Stanley and Newnham2013). Preterm birth is another established risk factor, as lower gestational age and birth weight have been related to higher infant negative affectivity (Barroso et al., Reference Barroso, Hartley, Bagner and Pettit2015).

In addition to being associated with temperament, perinatal complications have been found to positively predict children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. For example, prenatal maternal internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression) positively predicts preschool/early school-age children’s internalizing symptoms (Field, Reference Field2011; Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Szekely et al., Reference Szekely, Neumann, Sallis, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Verhulst, Meaney, Pearson, Levitan, Kennedy, Lydon, Steiner, Greenwood, Tiemeier, Evans and Wazana2021). Depressive symptoms during pregnancy also have been positively related to children’s externalizing problems (Pihlakoski et al., Reference Pihlakoski, Sourander, Aromaa, Rönning, Rautava, Helenius and Sillanpää2013). For pregnancy cardiometabolic complications, both gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal hypertensive pregnancy disorders have been related to increased emotional and behavioral problems, including externalizing and internalizing symptoms amongst children (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lähdepuro, Tuovinen, Girchenko, Rantalainen, Heinonen, Lahti, Räikkönen and Lahti-Pulkkinen2021; Shuffrey et al., Reference Shuffrey, Morales, Jacobson, Bosquet Enlow, Ghassabian, Margolis, Lucchini, Carroll, Crum, Dabelea, Deutsch, Fifer, Goldson, Hockett, Mason, Jacobson, O’Connor, Pini and Rayport2023). Similarly, preterm birth and low birth weight have been identified as risk factors for children’s emotional disorders and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD) (Johnson & Marlow, Reference Johnson and Marlow2011).

Negative affectivity is related to emotional and behavioral problems

Negative affectivity has been found to positively predict emotional and behavioral problems, including internalizing and externalizing problems (Naragon-Gainey et al., Reference Naragon-Gainey, McMahon and Park2018; Nigg, Reference Nigg2006; Stanton & Watson, Reference Stanton and Watson2014). Internalizing and externalizing problems as broad classes of psychopathology share substantial genetic covariation with aspects of temperament, including negative affectivity (Mikolajewski et al., Reference Mikolajewski, Allan, Hart, Lonigan and Taylor2013; Nigg, Reference Nigg2006). Negative affectivity could provide an early-emerging vulnerability or liability for psychopathology. In addition to shared genetic effects, negative affectivity may elicit responses from the environment, such as interactions with parents and peers, which could then lead to psychopathology through amplifying or canalizing processes (Nigg, Reference Nigg2006). For example, in an adoption study, birth mothers’ prenatal psychopathology symptoms predicted toddlers’ negative reactivity, which, in turn, was positively associated with adoptive parents’ over-reactive and hostile parenting 9 months later (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ji, Chow, Kang, Leve, Shaw, Ganiban, Natsuaki, Reiss and Neiderhiser2020). In this way, negative affectivity could positively predict future internalizing and externalizing problems via complex developmental processes, involving both genetic and environmental influences.

Because child negative affectivity is associated with both perinatal complications and psychological symptoms, it might serve a key role in the developmental pathway from early perinatal risk to later internalizing and externalizing problems. In support for this, negative affectivity has been found to mediate the positive relation between prenatal maternal mood problems and children’s internalizing behavior (Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023). Similarly, behavioral inhibition, which is closely related to fearfulness, has been found to mediate the association between perinatal complications and children’s social anxiety (Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Morales, Metcalf and Pérez-Edgar2019). However, although negative affectivity is known to predict externalizing problems, to our knowledge, no study has examined the indirect predictions from perinatal complications to externalizing problems via negative affectivity; thus, this represents an important area for further research. In support for this, there have been recent calls for a more thorough examination of the predictions from perinatal complications to child externalizing disorders (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Lähdepuro, Tuovinen, Girchenko, Rantalainen, Heinonen, Lahti, Räikkönen and Lahti-Pulkkinen2021).

Beyond investigating pathways to internalizing and externalizing problems separately, there has been growing interest in examining overall or general psychopathology, given that individuals could experience multiple disorders at the same time (Angold et al., Reference Angold, Costello and Erkanli1999), and internalizing and externalizing problems are strongly correlated (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014; McElroy et al., Reference McElroy, Belsky, Carragher, Fearon and Patalay2018; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Tang, Bowers, Miller, Buzzell, Smith and Fox2022; Olino et al., Reference Olino, Bufferd, Dougherty, Dyson, Carlson and Klein2018). The general psychopathology factor “p” captures the shared variance of internalizing and externalizing problems (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014). Although it is most commonly measured through bifactor models, general psychopathology can be robustly captured in various ways (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Fisher, Danese and Moffitt2023), including via the Total Problems scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Hicks, Angstadt, Rutherford, Taxali, Hyde, Weigard, Heitzeg and Sripada2021). In addition, The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework that intends to develop new classifications of mental disorders for research aims to identify broad dimensions, spanning from general normal to abnormal functioning, instead of dividing into heterogeneous disorders (Insel et al., Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn and Wang2010; Sanislow et al., Reference Sanislow, Pine, Quinn, Kozak, Garvey, Heinssen, Wang and Cuthbert2010). Child temperament, including negative affectivity, has been found to serve as a risk factor for general psychopathology (Hankin et al., Reference Hankin, Davis, Snyder, Young, Glynn and Sandman2017; Olino et al., Reference Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson and Klein2014). Moreover, infant temperament has been examined as a mediator between maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and child adjustment comprising internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Stürmlinger et al., Reference Stürmlinger, Ray, Von Krause, Nonnenmacher, Alpers and Zietlow2025). Despite the documented associations between perinatal complications and child temperament and adjustment, limitations in existing studies of these associations included focusing on young and small samples (i.e., early to middle childhood and fewer than 500 participants) (e.g., Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Morales, Metcalf and Pérez-Edgar2019), using retrospective measures of perinatal complications (e.g., Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Morales, Metcalf and Pérez-Edgar2019), and recruiting mostly homogenous samples in terms of race and ethnicity (i.e., predominantly Caucasian) (e.g., Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Morales, Metcalf and Pérez-Edgar2019).

The current study

In the current study, we examined the relations among perinatal complications (i.e., prenatal maternal depression and cardiometabolic complications, preterm birth, and low birth weight), children’s negative affectivity in childhood, and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems and general psychopathology problems in childhood or adolescence. We addressed four aims. The first aim was to examine if negative affectivity was predicted by perinatal complications. We hypothesized that greater maternal prenatal depression, any maternal cardiometabolic complications in pregnancy (versus none), preterm birth (versus not preterm birth), and small for gestational age (SGA) (versus not small) would be associated with higher levels of negative affectivity in children. The second aim was to examine if children’s negative affectivity was longitudinally associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing problems and general psychopathology problems. We hypothesized that higher negative affectivity would predict higher levels of later externalizing and internalizing problems as well as general psychopathology problems. The third aim was to examine if negative affectivity was a mediator in the longitudinal relations between perinatal complications and children’s externalizing, internalizing, and general psychopathology problems. We hypothesized negative affectivity would be a significant mediator in the relations between perinatal complications and children’s externalizing and internalizing problems as well as general psychopathology problems. The fourth aim was to explore if demographic factors acted as moderators in the first and second aims. This aim was exploratory in nature, seeking to generate hypotheses for future research. Because previous studies have found differential effects in relation to child temperament and externalizing and internalizing problems by child sex, child age, and socioeconomic status (SES) (Morales et al., Reference Morales, Beekman, Blandon, Stifter and Buss2015, Reference Morales, Miller, Troller-Renfree, White, Degnan, Henderson and Fox2020; Padilla et al., Reference Padilla, Hines and Ryan2020; Takács et al., Reference Takács, Putnam, Bartoš, Čepický and Monk2021), we examined if patterns of relations in the first and second aims differed based on child sex, child age, or family SES (i.e., maternal education).

Methods

Participants

The present study utilized data from the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program, a research initiative supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from 2016 as a large-scale consortium. The ECHO Program combines existing longitudinal birth cohorts and funds additional recruitments and follow-ups of families previously enrolled in those cohorts (Blaisdell et al., Reference Blaisdell, Park, Hanspal, Roary, Arteaga and Laessig2022). Through collecting longitudinal data across the U.S. using a common protocol, ECHO intends to examine the impact of early environmental exposures on child health and development (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Kress, Parker, Page, McArthur, Gachigi, Alshawabkeh, Aschner, Bastain, Breton, Bendixsen, Brennan, Bush, Buss, Camargo, Catellier, Cordero, Croen and Dabelea2023). The final analyzed sample for this study consisted of 3070 children (47% female) and their primary caregivers. See Supplementary Figure 1 in supplementary materials for a flow chart of the inclusion and exclusion of the participants. Data were collected three times longitudinally. Specifically, birth complications were collected during the perinatal period (10 weeks gestational age through the birth of the child). Negative affectivity was collected across infancy and childhood (M = 2.77 years, SD = 2.32, age range = 0.24–12.46 years). Internalizing and externalizing problems were collected across childhood and adolescence (M = 5.15 years, SD = 2.62, age range = 1.50–16.85 years). The average time gap between the assessments of negative affectivity and internalizing and externalizing problems was 2.37 years (SD = 1.14, range = 0.50–5.45 years). Data were collected across 22 ECHO cohorts enrolled from 18 states and one territory of the U.S. (California, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Puerto Rico, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington). The majority of the child participants were White (58%), followed by Black (19%), multi-racial (11%), and others (12%) (i.e., Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian). Twenty-eight percent of participants were Hispanic/Latinx. The median level of maternal education, assessed in pregnancy, was “some college, no degree; Associate’s degree (A.A., AS); trade school,” with the range from less than high school to a master’s degree and above. Parents who participated in the study were primary caregivers (N = 3070), including 2570 biological mothers, 22 biological fathers, and 478 adoptive mothers.Footnote 1 For biological mothers, most of them were White (63%), followed by Black (19%), and others (18%) (i.e., Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian, multi-racial). Their average age was 29.54 years (SD = 5.91, age range = 13.70–49.40 years) at the birth of the child. In addition, we measured area–level socioeconomic disadvantage using the Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index (SVI), a census–tract–level measure representing neighborhood vulnerability based on 16 variables, including socioeconomic status, household characteristics, minority status, and housing and transportation, derived from the American Community Survey and aggregated into a continuous scale ranging from 0 (lowest vulnerability) to 1 (highest vulnerability) (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Zhang and Kowal2025). SVI has been found to predict adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth and perinatal mortality (Kawakita et al., Reference Kawakita, Hayasaka, Robbins, Martins and Saade2025). In our sample, the SVI had a mean of .50 (SD = 0.32), indicating moderate variation in neighborhood-level vulnerability across participants.

Measures

Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms

Biological mothers reported their own depressive symptoms during pregnancy through different self-report depression symptom measures that were combined to harmonize into one common scale, the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Depression Scale (PROMIS®-D; Blackwell et al., Reference Blackwell, Tang, Elliott, Thomes, Louwagie, Gershon, Schalet and Cella2021). Different studies have used this scale (e.g., Avalos et al., Reference Avalos, Chandran, Churchill, Gao, Ames, Nozadi and Nguyen2023; Shuffrey et al., Reference Shuffrey, Morales, Jacobson, Bosquet Enlow, Ghassabian, Margolis, Lucchini, Carroll, Crum, Dabelea, Deutsch, Fifer, Goldson, Hockett, Mason, Jacobson, O’Connor, Pini and Rayport2023). Through this common scale, data collected from the following instruments could be aggregated: Edinburgh Prenatal/Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Reference Cox, Chapman, Murray and Jones1996), Adult Self-Report Achenbach System Depression Problems Syndrome Scale (Achenbach et al., Reference Achenbach, Rescorla, McConaughey, Pecora, Wetherbee, Ruffle, Reynolds and Kamphaus2003), Brief Symptom Inventory-18 item (BSI-18; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis2000), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Ball and Ranieri1996), SF-36 Health Survey Mental Health Summary (Ware et al., Reference Ware, Mark and Keller1994), and Kessler 6 Mental Health Scale (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002). In the present study, maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy were measured by BSI-18, EPDS, and PHQ-9. We used PROMIS-D T-scores, standardized to a U.S. general adult population with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. That is, an individual with a T-score of 50 would have depressive symptoms with a severity level equal to the average level of the general adult U.S. population. Higher scores reflect greater symptom severity. The ECHO Data Analysis Center converted maternal depressive symptom scores during pregnancy from different scales into standardized PROMIS-D T-scores. These PROMIS-D T-scores were created empirically using published crosswalk tables derived from multiple formal linking studies, which converted scores from non-PROMIS measures to the PROMIS T-score metric (see Blackwell et al., Reference Blackwell, Tang, Elliott, Thomes, Louwagie, Gershon, Schalet and Cella2021 and supplementary materials for details). If mothers were assessed multiple times in pregnancy, we used the average score of all available assessments.

Pregnancy cardiometabolic and other complications

Pregnancy cardiometabolic complications included gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. We combined all cardiometabolic complications into one summary score that indicated whether the biological mother had any of these complications or not (0 = no, 1 = yes). Other birth factors included child preterm birth, which refers to birth prior to 37 completed weeks of gestation (0 = not preterm birth, 1 = preterm birth), and SGA, which was defined as birth weight below the 10th percentile for the infant’s gestational age (coded as 0 = not SGA, 1 = SGA; Muhihi et al., Reference Muhihi, Sudfeld, Smith, Noor, Mshamu, Briegleb and Chan2016).

Data on pregnancy complications were harmonized across ECHO cohorts using maternal self-report via case report forms and abstraction from prenatal, delivery, and newborn medical records. When multiple sources were available, a predefined hierarchy (e.g., medical record > birth certificate > maternal recall) was applied. Harmonization involved systematic abstraction, range and plausibility checks, and resolution of discrepancies (e.g., gestational age differences ≥1 week) in consultation with contributing cohorts. Duplicate or conflicting entries were prioritized based on the earliest verified record, and all variables were recoded into standardized formats to reduce measurement error and ensure consistency for pooled analyses.

Child negative affectivity

Parents reported child negative affectivity using Rothbart’s Temperament Questionnaires in very short form (The Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised-Very Short Form; Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire-Very Short Form; Childhood Behavior Questionnaire-Very Short Form; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Gartstein and Rothbart2006, Reference Putnam, Helbig, Gartstein, Rothbart and Leerkes2017; Putnam & Rothbart, Reference Putnam and Rothbart2006) corresponding to the child’s age. Average child ages were 0.08, 1.80, and 4.60 years at the time of assessment for the infant, early childhood, and childhood versions of the questionnaires, respectively. Each of these questionnaires consists of 36–37 items that measure three broad temperament domains: surgency/positive affectivity, negative affectivity, and effortful control/regulation (orienting/regulation for the infant version). Parents rated the frequency their children displayed the behavior described in each item using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “1 = never” to “7 = always.” In the current study, only the negative affectivity factor score was used (12 items for each version). Example items include “When introduced to an unfamiliar adult, how often did the baby cling to a parent? (infant version)”; “While having trouble completing a task, how often did your child get easily irritated? (early childhood version)”; “Gets angry when s/he can’t find something s/he wants to play with. (childhood version).” We used the average score of the 12 items to represent negative affectivity, and higher scores indicate higher levels of temperamental negative affectivity. Convergent, predictive, and discriminant validity have been established for negative affectivity across different versions (Allan et al., Reference Allan, Lonigan and Wilson2013; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Helbig, Gartstein, Rothbart and Leerkes2014). Although temperament and child behavioral and emotional problems are related and possibly overlapping when examined with parent reports, there are important conceptual and methodological differences. For example, to address the potential overlap, Eisenberg et al. (Reference Eisenberg, Sadovsky, Spinrad, Fabes, Losoya, Valiente, Reiser, Cumberland and Shepard2005) identified and removed CBQ items that experts rated as overlapping with externalizing and internalizing problems. Even after removing these items, negative affectivity had good reliability and predicted internalizing and externalizing problems. Studies like this suggesting the CBQ is a reliable measure with adequate discriminant validity, and further supports the interpretation that while related, temperament and psychopathology are conceptually and empirically distinct. In the current sample, all versions demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .80, .72, and .72 for infant, early childhood, and childhood versions, respectively).

Child internalizing, externalizing, and total symptoms

Parents reported child emotional and behavioral problems using the Preschool Child Behavior Checklist 1½–5 (CBCL 1½–5, Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000) or School Age Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 6–18; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001), depending on the child’s age. Average child ages at the time of assessment were 3.14 years and 7.65 years for the preschool and school-age versions of the questionnaires, respectively. For both CBCL 1½–5 (100 items) and CBCL 6–18 (113 items), parents rated each of the listed behavior as Not True (0), Somewhat or Sometimes True (1), and Very True or Often True (2) for their children. The CBCL 1½–5 has seven total syndrome scales (emotionally reactive, anxious/ depressed, somatic complaints, withdrawn, sleep problems, attention problems, and aggressive behaviors), and the CBCL 6–18 has eight total syndrome scales (anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behaviors). Both versions have two second-order factors, internalizing problems and externalizing problems, which were used in the current study. Internalizing problems of CBCL 1½–5 include emotionally reactive, anxious/ depressed, somatic complaints, and withdrawn and internalizing problems of CBCL 6–18 include anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic complaints. Externalizing problems of CBCL 1½–5 include attention problems and aggressive behaviors and externalizing problems of CBCL 6–18 include rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behaviors. Both versions of the CBCL have demonstrated high test-retest reliability and internal consistency across different subscales (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). Both versions’ content validity and criterion validity have been well established (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). The Total Problems score captures additional domains not represented in the internalizing or externalizing factors (i.e., sleep and other problems in CBCL 1½–5; social, thought, attention, and other problems in CBCL 6–18), providing a more comprehensive assessment of general psychopathology. Because CBCL T-scores are age- and gender-standardized, they provide developmentally appropriate measures of each child’s behavioral and emotional problems, enabling direct comparability across age and CBCL versions (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach2013), we used T-scores for our main analyses. Importantly, the same pattern of results is found if raw scores are used.

Statistical analyses

Path analyses using structural equation model (SEM) were performed through the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012) to examine the mediating role of negative affectivity in the association between perinatal complications and children’s internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. Predictors of child negative affectivity and of internalizing, externalizing, and total problems included maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy, pregnancy cardiometabolic complications (whether the biological mother had any complications or not), preterm birth, and SGA. The mediator for all paths was child negative affectivity, and outcomes were child internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. The model controlled for the child’s age at CBCL administration, maternal education, child sex, child ethnicity (Hispanic/Latinx or not), and child race.

We began by testing whether any perinatal factors were significantly associated with negative affectivity and whether negative affectivity, in turn, predicted at least one outcome. Following this, we assessed potential mediation effects by using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure using 10,000 bootstrap samples to generate confidence intervals for the indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004; Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). We also examined child age when negative affectivity was measured, child age when emotional and behavior problems were measured, maternal education, and child sex as potential moderators in the mediation model and used simple slope analyses to probe any significant interactions. For child age and maternal education, moderation was tested by creating an interaction term between the moderator and any significant predictor identified in the model. When negative affectivity was the outcome, we used child age at the negative affectivity assessment; when children’s internalizing, externalizing, and total problems were the outcomes, we used child age at the CBCL assessment. For child sex, we conducted multi-group analyses, testing whether constraining significant paths to be equal across boys and girls significantly worsened model fit. We used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to account for missing data and maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) estimator to deal with potential nonnormality of the variables (Lei & Shiverdecker, Reference Lei and Shiverdecker2020). To assess the model fit, we used the criteria outlined by Hu and Bentler (Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

Results

Descriptive analyses

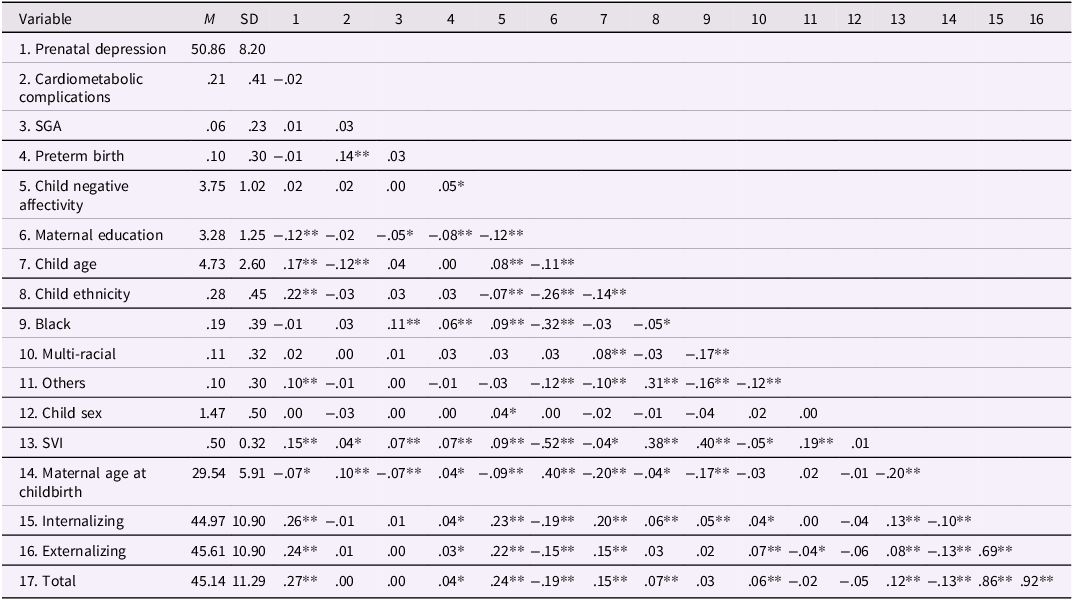

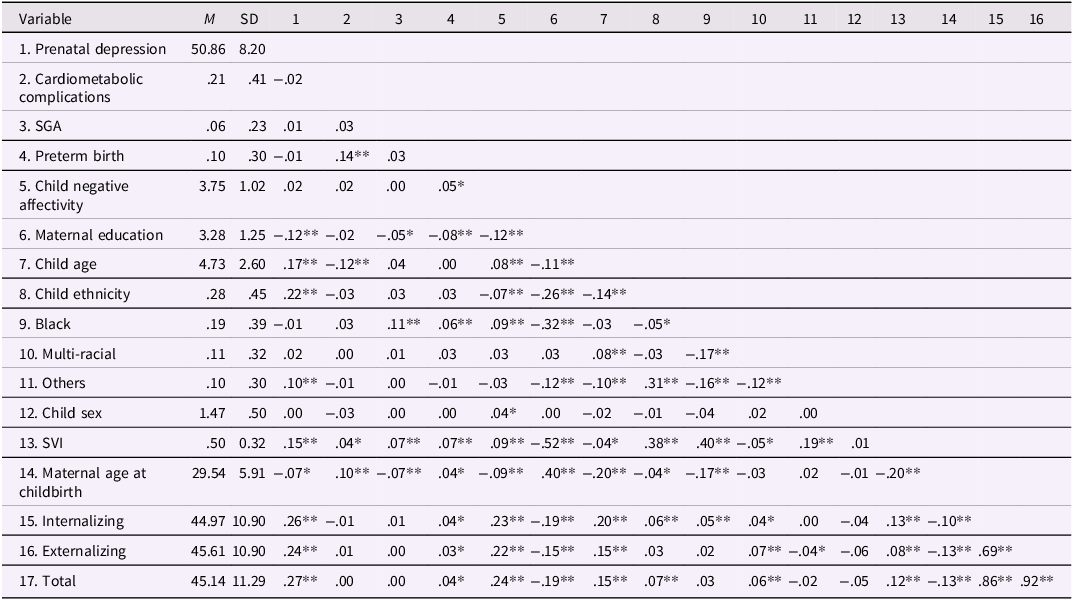

Descriptive statistics and correlations of all the study and control variables are presented in Table 1. Regarding associations among the main study variables, maternal depression in pregnancy was positively correlated with child internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. Pregnancy cardiometabolic complications were positively correlated with child preterm birth. Preterm birth was positively correlated with child negative affectivity and child internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. Child negative affectivity was positively correlated with child internalizing, externalizing, and total problems.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all study and control variables

Note. N = 1340-3070. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; SGA = birth weight small for gestational age; SVI = Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index; For cardiometabolic complications, 0 = did not have any complications, 1 = had at least one type of complications; For SGA, 0 = not small for gestational age, 1 = small for gestational age; For preterm birth, 0 = not preterm birth, 1 = preterm birth; For child ethnicity, 0 = Non-Latinx; 1 = Latinx; For Black, 0 = Non-Black; 1 = Black; For multi-racial, 0 = Non-multi-racial; 1 = multi-racial; For others, 0 = participants who were White, Black, or multi-racial; 1 = all other participants who were not White, Black, or multi-racial; For child sex, 1 = male, 2 = female.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Primary analyses

We used two path analysis models to examine the mediation effects, one for internalizing problems and externalizing problems (Model 1), and the other for total problems (Model 2) to examine the developmental pathway. Predictors, the mediator, and covariates were the same for both models. Model 1 demonstrated a good fit for the data based on Hu and Bentler’s (Reference Hu and Bentler1999) guidelines, χ 2(24) = 120.52, p < .001; CFI = .98; TLI = .92; SRMR = .02; RMSEA = .04; 95% CI [0.03, 0.04]. Among the participants (N = 3070), 1340 had data on prenatal maternal depression, all had data on prenatal maternal cardiometabolic complications, 3060 had data on preterm birth and 2805 had data on SGA. We used FIML estimation to account for missing data (Lei & Shiverdecker, Reference Lei and Shiverdecker2020). This allowed us to include any participant that had at least one measure in our main variables of interest.

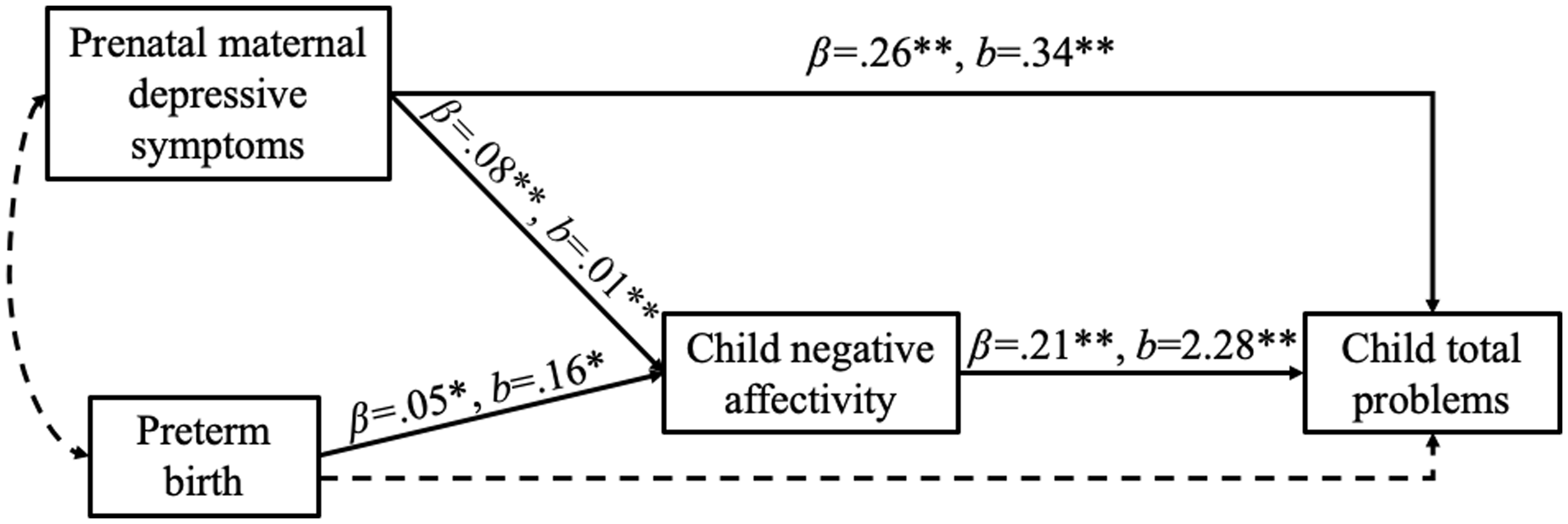

Significant associations among the primary study variables are displayed in Figure 1, while the full model including nonsignificant findings and results related to covariates are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Model 1 indicated that greater maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth (compared to not preterm birth) predicted greater child negative affectivity. Additionally, greater maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and child negative affectivity predicted greater child internalizing and externalizing problems. We also found child negative affectivity’s significant mediation pathways. Specifically, child negative affectivity was a significant mediator in the longitudinal relation between maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and child internalizing and externalizing problems (b = 0.02, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.006, 0.034] and b = 0.02, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.006, 0.033], respectively). Child negative affectivity was also a significant mediator in the longitudinal association between preterm birth and child internalizing and externalizing problems (b = 0.34, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.072, 0.617] and b = 0.33, bootstrapped 95% CI [.070, .596], respectively).

Figure 1. Structural equation model examining the relations among perinatal complications, child negative affectivity, and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Note. Significant paths are in solid lines and nonsignificant paths are in dashed lines. To see the full model including nonsignificant paths and covariates with standardized and unstandardized estimates, see Supplementary Table 1. Other predictors to child negative affectivity and internalizing and externalizing problems included in the analysis were maternal cardiometabolic complications in pregnancy and birth weight small for gestational age (SGA). For preterm birth, 0 = not preterm birth, 1 = preterm birth. Control variables were Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index (SVI), maternal education, age of child at the CBCL assessment, child sex, child ethnicity, and child race. Internalizing = internalizing problems; Externalizing = externalizing problems. *p < .05, **p < .01.

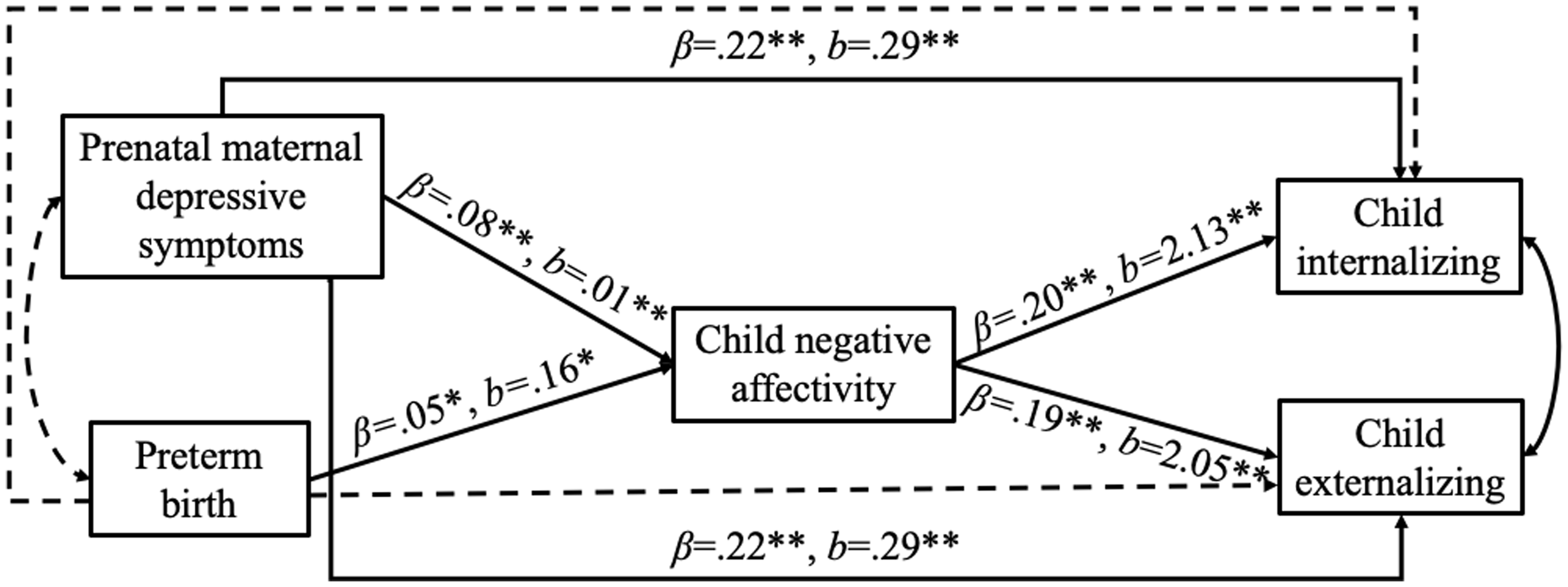

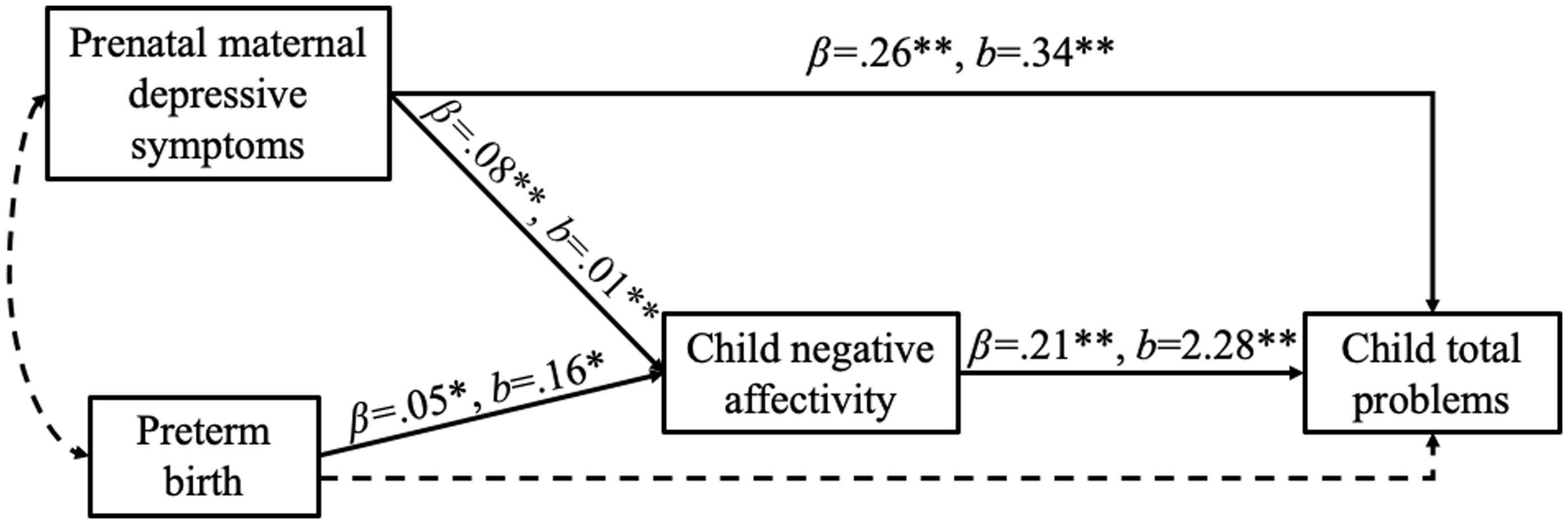

Similarly, Model 2 demonstrated a good fit for the data based on Hu and Bentler’s (Reference Hu and Bentler1999) guidelines, χ 2(24) = 119.35, p < .001; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.90; SRMR = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.04; 95% CI [0.03, 0.04]. Significant associations among the primary study variables are displayed in Figure 2, while the full model including nonsignificant findings and results related to covariates are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Model 2 indicated that greater maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth (compared to not preterm birth) predicted greater child negative affectivity. Additionally, greater maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and child negative affectivity predicted greater child total problems. We also found child negative affectivity’s significant mediation pathways. Specifically, child negative affectivity was a significant mediator in the longitudinal relation between maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and child total problems (b = 0.02, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.007, 0.036]). Child negative affectivity was also a significant mediator in the longitudinal association between preterm birth and child total problems (b = 0.36, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.077, 0.655]).

Figure 2. Structural equation model examining the relations among perinatal complications, child negative affectivity, and child total problems. Note. Significant paths are shown in solid lines and nonsignificant paths are in dashed lines. To see the full model including nonsignificant paths and covariates with standardized and unstandardized estimates, see Supplementary Table 2. Other predictors to child negative affectivity and total problems included in the analysis were maternal cardiometabolic complications in pregnancy and birth weight small for gestational age (SGA). For preterm birth, 0 = not preterm birth, 1 = preterm birth. Control variables were Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index (SVI), maternal education, age of child at the CBCL assessment, child sex, child ethnicity, and child race. *p < .05, **p < .01.

For both models, we examined if any demographic variables (i.e., maternal education, child age, and child sex) moderated the reported associations among perinatal complications, child negative affectivity, and child internalizing, externalizing, and total problems (i.e., perinatal complications’ predictions to child negative affectivity and internalizing, externalizing, and total problems, and child negative affectivity’s prediction to internalizing, externalizing, and total problems). We did not observe any significant moderation effects. Moreover, because data in the present study were collected across 22 ECHO cohorts, observations within cohorts were not independent. To account for potential correlations among participants within the same cohort, we conducted multilevel models (MLMs) parallel to Models 1 and 2 as sensitivity analyses. These models were conducted separately for each outcome, and separately for prenatal depression and preterm birth because prenatal depression had considerable missing data and listwise deletion was used for missing data in MLMs. As shown in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Tables 3–6), the results are the same with similar estimates to the ones presented in the main analyses of Models 1 and 2. Finally, we additionally tested models including other temperament dimensions (surgency and effortful control) and found that our main results remained significant and were specific to negative affectivity (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8).

Discussion

In the current study, we examined if negative affectivity served as a developmental mechanism in the longitudinal pathway between perinatal complications and children’s emotional and behavioral problems. We found that child negative affectivity mediated the longitudinal relation between maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and child internalizing and externalizing problems. In addition, child negative affectivity mediated the longitudinal relation between preterm birth and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Findings in the current study support the DOHaD framework by highlighting the importance of perinatal complications on the development of children’s temperament and future psychopathology. Moreover, our findings extend negative affect’s mediating role on internalizing problems in early to middle childhood (Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Hernandez-Castro, Yang, Dunton, Farzan, Breton and Morales2025; Suarez et al., Reference Suarez, Morales, Metcalf and Pérez-Edgar2019) to further support the role of negative affectivity as a developmental pathway linking perinatal complications to child externalizing and overall emotional and behavioral problems at an older age. Our findings also supported the RDoC framework by identifying the role of negative affectivity in the development of total problems, a broad dimension that combines internalizing and externalizing problems (Insel et al., Reference Insel, Cuthbert, Garvey, Heinssen, Pine, Quinn and Wang2010; Sanislow et al., Reference Sanislow, Pine, Quinn, Kozak, Garvey, Heinssen, Wang and Cuthbert2010).

Among several perinatal complications examined, maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth were the two significant predictors to child negative affectivity. This is in line with existing studies finding that children with perinatal complications (i.e., mothers’ depressive and mood symptoms in pregnancy, preterm birth) showed more negative affectivity in infancy and toddlerhood than their peers without these complications (Barroso et al., Reference Barroso, Hartley, Bagner and Pettit2015; Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Rouse & Goodman, Reference Rouse and Goodman2014). In addition, children of mothers who reported more depressive symptoms in pregnancy had more internalizing and externalizing problems, which is similar to previous studies (Field, Reference Field2011; Green et al., Reference Green, Szekely, Babineau, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Bouvette-Turcot, Minde, Sassi, Atkinson, Kennedy, Steiner, Lydon, Gaudreau, Burack, Herba, Pennestri, Levitan, Meaney and Wazana2023; Pihlakoski et al., Reference Pihlakoski, Sourander, Aromaa, Rönning, Rautava, Helenius and Sillanpää2013; Szekely et al., Reference Szekely, Neumann, Sallis, Jolicoeur-Martineau, Verhulst, Meaney, Pearson, Levitan, Kennedy, Lydon, Steiner, Greenwood, Tiemeier, Evans and Wazana2021). These results align with the DOHaD model, suggesting that prenatal influences could contribute to children’s developmental trajectories (Doyle & Cicchetti, Reference Doyle and Cicchetti2018). Beyond genetic contributions, maternal psychological distress during pregnancy may shape child outcomes – such as temperament and mental health – through mechanisms that impact fetal brain development, including hormonal influences, alterations in placental functioning and perfusion, and epigenetic changes (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Austin, Knapp, Vaiano and Galbally2015; Monk et al., Reference Monk, Lugo-Candelas and Trumpff2019). Although negative affectivity and internalizing and externalizing problems were measured across different ages (child age range was 0.50–5.45 years when negative affectivity was measured and was 1.50–16.85 years when emotional and behavioral problems were measured), these effects were not modified by age. Similarly, maternal depression has been found to positively and persistently predict behavioral and emotional symptoms across childhood, without the effect increasing or decreasing as children grow older (O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Glover, Barker and O’Connor2014). Maternal depression during pregnancy has been linked to elevated cortisol levels in offspring, likely through its programming effects on the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Oberlander et al., Reference Oberlander, Weinberg, Papsdorf, Grunau, Misri and Devlin2008). Dysregulation of the HPA axis has been implicated in children’s ability to regulate negative emotions (Field et al., Reference Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif, Schanberg and Kuhn2002; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Anh, Li, Chen, Rifkin-Graboi, Broekman, Kwek, Saw, Chong, Gluckman, Fortier and Meaney2015) as well as in the emergence of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Kallen et al., Reference Kallen, Tulen, Utens, Treffers, De Jong and Ferdinand2008; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Schatzberg and Lyons2003).

In regard to the association between preterm birth and negative affectivity, similar to maternal depression, preterm birth has been related to the development of the HPA axis. Preterm-born infants are neuroendocrinologically immature, and a stay in a neonatal intensive care unit is associated with exposure to stressful events that might further disturb the central regulation of HPA axis (Lammertink et al., Reference Lammertink, Vinkers, Tataranno and Benders2021). Similarly, preterm birth could lead to early, repeated, stressful, and painful medical procedures, which could impact infant development (Grunau, Reference Grunau2002). For example, preterm infants’ neonatal distress pain-related procedures have been found to predict higher levels of negative affectivity (Valeri et al., Reference Valeri, Holsti and Linhares2015). In addition, compared to parents of children born full-term, parents of children born preterm have been found to show less sensitivity, more intrusiveness, and more withdrawal (Bugental et al., Reference Bugental, Corpuz and Samec2013; Hoffenkamp et al., Reference Hoffenkamp, Braeken, Hall, Tooten, Vingerhoets and Van Bakel2015). Thus, preterm birth could be associated with more negative parent-child interactions, which, in turn, predict greater child negative affectivity.

It is also important to note that prenatal teratogenic exposures, such as maternal smoking and alcohol use, may contribute to the findings in the present study, as these exposures have been linked to greater maternal emotional distress during pregnancy and an increased risk of preterm birth (Anunziata et al., Reference Anunziata, Frankeberger, Baer, Chambers and Bandoli2025; Cerrizuela et al., Reference Cerrizuela, Vega-Lopez and Aybar2020; Širvinskienė et al., Reference Širvinskienė, Žemaitienė, Jusienė, Šmigelskas, Veryga and Markūnienė2016). Furthermore, because prenatal teratogenic exposures also predict children’s later internalizing and externalizing problems (Lees et al., Reference Lees, Mewton, Jacobus, Valadez, Stapinski, Teesson and Squeglia2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Shu, Huang, Feng and Yang2025), such exposures may partially explain or moderate the links between prenatal complications and children’s negative affectivity and psychopathology. Future larger studies are needed to simultaneously examine a broader range of perinatal complications to elucidate the independent and combined effects of multiple exposures on child socioemotional outcomes.

We also found that greater child negative affectivity was associated with greater internalizing and externalizing problems later in childhood and adolescence. Importantly, we found that negative affectivity could help explain how maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth are linked to children’s later emotional and behavioral problems. These findings add to the literature on similar mediation effects by studying negative affectivity and internalizing and externalizing problems across childhood and adolescence, beyond just early childhood. Moreover, our results provide evidence of negative affectivity serving as a pathway to general psychopathology, as we found significant mediation effects for internalizing, externalizing, and total problems. Although child temperament has been found to serve as a risk factor for general psychopathology (Hankin et al., Reference Hankin, Davis, Snyder, Young, Glynn and Sandman2017; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Tang, Bowers, Miller, Buzzell, Smith and Fox2022; Olino et al., Reference Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson and Klein2014), our findings extended the role of child temperament as a pathway linking perinatal complications to psychopathology.

In contrast to maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth, maternal cardiometabolic complications and SGA did not predict child negative affectivity or internalizing and externalizing problems. Thus, we did not find evidence for mediation effects in these relations. One possible explanation for the lack of effects with cardiometabolic complications is that relatively few mothers experienced cardiometabolic complications in pregnancy in our sample. Consequently, we did not differentiate the types of cardiometabolic complications. Combining all types of cardiometabolic complications may have limited our ability to examine their effects on child negative affectivity or their internalizing and externalizing problems because their effects may differ across types of complications.

Limitations and future directions

The current findings should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, perinatal complications and child negative affectivity and psychopathology were reported by caregivers. To reduce shared-method variance, researchers could use behavioral tasks or different informants (e.g., parent, teacher, child) to examine whether the relations between perinatal complications and child outcomes change when shared-method variance is removed. However, previous analyses suggest that maternal characteristics (e.g., psychopathology) may not bias caregiver report (Olino et al., Reference Olino, Michelini, Mennies, Kotov and Klein2021). Moreover, existing studies using behavioral observations have documented similar associations between temperament and later psychopathology (Morales et al., Reference Morales, Tang, Bowers, Miller, Buzzell, Smith and Fox2022; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Crawford, Morales, Degnan, Pine and Fox2020), which ameliorate concerns of shared-method variance. Additionally, with respect to facets of negative affectivity (i.e., anger, fear, sadness), we were unable to examine them separately because the Very Short Form of the temperament scales does not yield reliable facet-level scores. Future research should consider using the full version of temperament scales with reliable subscales to clarify whether specific facets of negative affectivity play distinct roles in linking perinatal complications with child outcomes. Second, although the current study was longitudinal, the stability of child negative affectivity and psychopathology were not controlled. Future studies could examine if the predictions of maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth and the mediating role of child negative affectivity exist above and beyond the stability of child negative affectivity and psychopathology. Third, we examined the prediction of perinatal complications to child negative affectivity and later psychopathology without considering the effects of other postnatal factors (e.g., postnatal maternal psychopathology). While these factors may remain relatively consistent from the prenatal to postnatal periods, changes from the prenatal period to early childhood have been found to influence child outcomes (e.g., Park et al., Reference Park, Brain, Grunau, Diamond and Oberlander2018). In addition, pathways such as prenatal programming of the HPA axis and early parent–child interactions may link perinatal complications with child outcomes, but these mechanisms could also be shaped by postnatal conditions not captured in our data. We tested for moderation effects by age and found that age did not moderate any direct or indirect effects between perinatal complications and child emotional and behavioral problems, suggesting that the associations with perinatal complications did not increase over time because of potential cumulative adversity, developmental vulnerabilities, or compounding exposures. Although we adjusted for area-level socioeconomic disadvantage using the Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index, this measure may not adequately capture family- or individual-level risk factors that emerge postnatally (e.g., parenting quality, family stress, maternal mental health). To clarify the unique contribution of prenatal factors, future research should incorporate both neighborhood- and family-level contextual factors occurring during the postnatal period. Fourth, our examination of perinatal complications was limited to prenatal maternal depression and cardiometabolic complications, preterm birth, and low birth weight. Other relevant prenatal and perinatal risk factors, including prenatal teratogenic exposures (e.g., maternal smoking, alcohol use, and other substance exposures) and intrapartum events that may lead to anoxia or hypoxia (e.g., umbilical cord prolapse, placental abruption, or prolonged obstructed labor), were not included. As a result, the range of complications captured was relatively narrow. Future research with more comprehensive assessments of perinatal complications and prenatal teratogenic exposures could provide a fuller picture of how diverse prenatal and perinatal risk factors contribute to child temperament and psychopathology.

Conclusion

The current study found that child negative affectivity has a role in the developmental pathway from maternal depressive symptoms in pregnancy and preterm birth to child internalizing and externalizing problems, and general psychopathology problems. These findings inform our understanding of the development of early individual differences in socioemotional development and support the DOHaD framework by demonstrating that prenatal factors are predictive of child developmental outcomes (Doyle & Cicchetti, Reference Doyle and Cicchetti2018). These findings add to the literature on similar mediation effects by studying child temperament and psychopathology at older ages and extending the role of temperament in the longitudinal predictions from perinatal complications to other types of psychopathologies beyond internalizing problems (i.e., externalizing problems and general psychopathology problems). Thus, interventions aimed at preventing preterm birth, reducing maternal psychopathology during pregnancy, and addressing temperament-based factors could improve children’s mental health and psychological well-being.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579426101175.

Data availability statement

Select de-identified data from the ECHO Program are available through NICHD’s Data and Specimen Hub (DASH). Information on study data not available on DASH, such as some Indigenous datasets, can be found on the ECHO study DASH webpage.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank our ECHO Colleagues; the medical, nursing, and program staff; and the children and families participating in the ECHO cohorts. We also acknowledge the contribution of the following ECHO Components – Coordinating Center: Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina: Smith PB, Newby LK; Data Analysis Center: Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland: Jacobson LP; Research Triangle Institute, Durham, North Carolina: Catellier DJ; Person-Reported Outcomes Core: Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois: Gershon R, Cella D.

Funding statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program, Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, under Award Numbers U2COD023375 (Coordinating Center), U24OD023382 (Data Analysis Center), U24OD023319 with co-funding from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (PRO Core), UH3OD023389 (Leve, Neiderhiser, Ganiban), UH3OD023251 (Alshawabkeh), UH3OD023279 (Elliott), UH3OD023285 (Kerver), UH3OD023248/UG3OD023248 (Dabelea), UH3OD023328 (Duarte, Canino, Monk, Posner), UH3OD023290 (Herbstman), UH3OD023305 (Trasande), UH3OD023320 (Aschner), UG3OD023313 (Koinis Mitchell), UG3OD023318 (Dunlop), UH3OD023289 (Ferrara), UH3OD023287 (Breton), UH3OD023288 (McEvoy), UH3OD023349 (O’Connor), UH3OD023272 (Schantz), UH3OD023249 (Stanford), UH3OD023337 (Wright), UH3OD023344 (Mackenzie).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All data collection and research methods were approved by IRBs at each cohort site and the ECHO Data Analysis Center, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Pre-registration statement

This study was not pre-registered.

AI statement

Artificial intelligence was not used in this manuscript.