During the 2016 presidential primary and general elections, pundits and commentators noted some of the many criticisms that Black people had of Hillary Clinton. Early in her campaign, Clinton was confronted by Black Lives Matter activists regarding her past statements in which she referred to Black people as “super predators,” a normalized opinion at the time. Clinton’s 1996 super predators remark echoed racists comments about Black people and crime (Gillstrom Reference Gillstrom2016). Despite these early criticisms of Clinton by Black people, there was overwhelming support for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, further highlighting the race-gender differences in Clinton support. Polls show that Black women were over 40% more likely to support Hillary Clinton than white women. In addition, Black women were 12% more likely to support Hillary Clinton than Black men (CNN 2016). Remarkably, over 94% of Black women supported Hillary Clinton.

Black people had their critiques of Hillary Clinton based on her past positions with regard to racial justice, but white women disliked Clinton for different reasons. In a 2017 interview with Vox, Clinton suggested that white women may have chosen not to vote for her because their husbands said that she would be in jail due to her mishandling of her personal emails (Millhiser Reference Millhiser2019). White women diverged from Black women on several issues dominating the presidential campaign. First, white women had higher levels of ambivalent sexism, which explained their support for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton (Frasure-Yokley Reference Frasure-Yokley2018). Second, generally, white women are more ideologically conservative than Black women, and married white women tend to vote like their husbands. Clinton’s speculation with regard to why white women did not vote for her is connected to long-standing research that has found that married couples tend to vote similarly (Glaser Reference Glaser1959). Research in the field of Black feminism and gender studies finds that white women conventionally choose white supremacy and patriarchy over the importance of gender (hooks Reference hooks1997). While Clinton deterred white women, Black women turned out for Clinton in high numbers despite their misgivings. Although 2016 felt exceptional, white women, in fact, have traditionally voted for the Republican candidate over the Democratic candidate in all presidential elections from 1952 to 2020, with only 1964 and 1996 serving as anomalies (Junn Reference Junn2016).

Black women occupy a unique social location in the racial and gender hierarchy of “identity politics” (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). The guiding theoretical framework for understanding this location is intersectionality. Rather than focusing exclusively on gender or exclusively race, intersectionality recognizes how the experiences of Black women are distinct and noncollapsible into these neat categories of identity and similar to standing at the middle of a four-way intersection. Thus, for Black women, racialized experiences are gendered and gendered experiences are racialized. Most of the literature on African American partisan identification has neglected the intersectional experiences of Black women informing their affective attachments toward the party (Simien Reference Simien2005; Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004). For instance, scholars largely focus on the racial contours of the partisan divide, noting—and rightly so—how many Blacks are strong Democrats given their elevated levels of racial identity, class backgrounds, and liberal policy views. We examine how Black women’s individual attachments to the Democratic Party as strong or weak partisans (long term) and their warmth toward Democratic Party candidates (short term) factor into their political decision-making and perceptions of its effectiveness.

Second, there is an entire field of political science that examines Black women’s politics. While these works are undoubtedly important, this literature is prone to overlooking Black women as voters and centers on Black women as leaders, candidates, and representatives (Brown Reference Brown2014; Philpot and Walton Reference Philpot and Walton2007). Given the increase in the salience of Black women as voters, greater attention must be paid to their mass behavior and attitudes. As Philpot and Walton (Reference Philpot and Walton2007, 50) note, “ironically few studies have been devoted to examining Black vote choice at the individual level.” Even fewer of these works, if any, center on the political action and attitudes of Black women as the focal group of analysis (Crowder Reference Crowder2023). This article examines the puzzle of Black women’s loyalty to the Democratic Party and support for Democratic candidates in the 2016 election. We consider the popular narrative that Black women’s ambivalence about the candidate running for office, Hillary Clinton, forestalled Black voter turnout. For two decades, Black women have been a reliable Democratic voting bloc (Gillespie and Brown Reference Gillespie and Brown2019), and we seek to explain how they behave as partisans relative to their white female and Black male counterparts.

This article investigates the political implications of partisan identity for Black women voters. Specifically, we seek to explain why Black women turned out for Clinton in such high numbers despite their ambivalence toward her as a candidate. In the first half of this article, we examine two principal questions. The first investigates the relationship of Black women to the Democratic Party. We examine how candidate favorability in 2016 influenced the voting behavior of Black women compared to Black men and white women. Second, we aim to understand how Black women’s perceptions of voting’s effectiveness and importance drive electoral participation to a greater extent than their Democratic partisan identity. We compare the effects between strong and weak partisans, between Black women and Black men, and then between Black women and white women. We demonstrate the necessity for scholars to engage Black women as voters to understand the context of Black political participation and partisan identity. Our article empirically demonstrates that Black women’s partisan identity is associated with their support for Democratic candidates; however, their faith in the democratic process, rather than their support for candidates, drives their turnout in presidential elections.

Black Women’s Civic Duty to Vote

Conventional wisdom posits that Black people have overwhelmingly supported the Democratic Party since the civil rights realignment that was marked by the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1990). Before the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party both avoided discussions of civil rights, but Lyndon B. Johnson’s strong stance on the Civil Rights Act differentiated the Democratic Party from the Republican Party. While the Democratic Party supported the Civil Rights Act, during this time, the Republican Party took an anti–civil rights stance and opposed the Civil Rights Act. Party leaders took clear stances and polarized on civil rights policy, and the mass public followed suit. The Democrats became identified with Black people and racial liberalism, and the Republican Party became the party of racial conservatism.

While Black people initially shifted support to the Democratic Party because of its clear support for civil rights policy, scholars have suggested that this does not fully explain why Blacks remain loyal to the party almost 60 years later. Scholarship has shown that Black people’s support of the Democratic Party has less to do with the Democratic Party’s support of Black people and more to do with the lack of a viable alternative to the Democratic Party. Paul Frymer’s (Reference Frymer1999, 8) theory of electoral capture argues that as a result of overwhelming loyalty to one party, “The party leadership … can take the group for granted because it recognizes that, short of abstention or an independent (usually electorally suicidal) third party, the group has nowhere else to go.” This led to Black women, in particular, turning out in high numbers for the Democratic Party (White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020).

Black women are a key demographic of the Democratic Party base. Exit poll data from 2016 show that Black women supported Clinton at 98% compared to 81% of Black men (Pew Research Center 2018). In addition, according to a Black Women’s Roundtable/Essence poll conducted in September 2016, Black women overwhelmingly (85%) felt that the Democratic Party best represented their interests. In the Essence poll, 61% of Black women agreed with the statement “Voting is my responsibility given our history as Black people.”Footnote 1 These preelection and postelection polls offer evidence that there are potential cleavages in the attitudes and behavior of Black men and women with respect to politics and perceptions of the Democratic Party. It is clear that Black women believe in voting to further the democratic/Democratic process, but their motivation as to why they vote differs from that of their white female and Black male counterparts. Further, as we elaborate in the subsequent pages, Black women’s understanding of the importance of civic duty as it pertains to voting behavior illustrates ideological and partisan differences when compared to Democratic white female and Black male voters.

Black political behavior is driven by shared norms and group consciousness (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Shingles Reference Shingles1981; White Reference White2007). Despite high levels of support for the Democratic Party, Black voters are heterogeneous on other dimensions. Black people generally have higher levels of linked fate (Dawson Reference Dawson1994), which coalesces their support for Democratic Party candidates (and each other). However, areas of differentiation among Black voters include their immigrant status (Greer Reference Greer2013), gender consciousness (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998), regional differences, and residential poverty (Shaw, Foster, and Combs Reference Shaw, Foster and Combs2019). With regard to gender, Black women differ from both Black men and white women in their level of political participation (Baxter and Lansing Reference Baxter and Lansing1983; Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001). However, few studies are well powered to examine differences among Black women and men, while also examining Black women in comparison to white women.

In 2016, many expected Clinton to woo women voters, in the same way that Barack Obama symbolically appealed to Black voters in 2008 and 2012. However, exit poll data reveal that Clinton did not woo all women voters. While an overwhelming majority of Black women voted for Clinton, only 43% of white women did the same, while 53% supported Republican candidate Donald Trump (Junn Reference Junn2016). Unlike white women and Black men, Black women consistently turn out for Democratic candidates at higher rates than any other group (Gillespie and Brown Reference Gillespie and Brown2019). However, not all Black women were highly supportive of Clinton, yet they still voted for the Democratic Party ticket.

Because of Clinton’s violation of traditional gender roles, the public’s views toward her were polarized as a first lady (Sulfaro Reference Sulfaro2007), and as a presidential candidate, her support was largely diminished by increased sexism among voters (Frasure-Yokley Reference Frasure-Yokley2018). Partisanship is a heuristic for voters to align with a political candidate and conveys a range of information (Downs Reference Downs1957). However, Black voters overwhelmingly identify as Democrats (White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020) and are pressured to remain Democrats despite their ideological diversity (Philpot Reference Philpot2017). Questions remain about the role of Democratic partisan identity in Black women’s vote choice, despite their overwhelming identification as Democrats. Thus, we demonstrate that candidate favorability (i.e., warmth toward Democratic candidates) and partisan identity (i.e., strong or weak Democrat) are less associated with Black women’s electoral engagement. Instead, we argue that Black women’s political engagement can be explained by their commitment to civic duty and perceptions of the efficacy of voting. In doing so, we seek to further complicate how partisan identity and attachments operate for Black voters, specifically Black women voters. Relying on partisan identification alone or using Black Democrats to discuss Black women voters misses several key attributes of their political decision-making process. Essentially, Black women voters employ myriad complicated factors when assessing their vote choice, not purely partisanship identification.

Civic duty, one civic norm about participation, is a determinant of voter turnout (Campbell, Gurin, and Miller Reference Campbell, Gurin and Miller1954), particularly as it pertains to Black voters (Collins and Block Reference Collins and Block2020). Higher levels of civic duty can recover lower levels of campaign enthusiasm, which strengthens the intention to vote (Collins and Block Reference Collins and Block2020). Voters who express greater attachment to civic duty participate in politics because of a sense of responsibility or a moral obligation to contribute to the democratic enterprise (Blais Reference Blais2000; Tullock Reference Tullock2000). Empirically, civic duty explains the commitment to voting, but yet to be explored is the relative effectiveness of voting compared to other forms of political expression (e.g., nonviolent protest, rioting, contacting elected representatives). The socialization, contextual, and institutional factors that Black women are situated in determine their obligations to engage in electoral and nonelectoral politics (Githens and Prestage Reference Githens and Prestage1977; Smooth Reference Smooth2018). This suggests that civic duty may not operate for white women in the same ways that it does for Black women, leaving open how gender dynamics shape civic duty among Black people.

Civic duty includes a range of actions from voting and running for office to protesting and volunteering. When it comes to Black women, we contend that their unique civic duty, which we operationalize as the effectiveness of voting, is connected to their faith in the political process. If we are to understand civic duty as one’s obligation to their community and upholding the laws, rights, and beliefs of others, Black women consistently serve as the canaries in the coal mine warning all others, regardless of party affiliation, of the potential dangers that lie ahead with respect to equality and inclusion in the democratic project. Black women consistently look out for themselves and others with respect to policy preferences, even when other groups ignore them or actively work against them in a policy space.

We suspect that Black women are motivated by nonpartisan factors, including their commitment to democratic principles, measured by their higher levels of civic duty. We argue that Black women’s civic duty is especially mobilizing when they are ambivalent about the presidential candidate and enthusiastic about the prospects for social change under a Democratic presidential administration. Black women’s entrenchment in the Democratic Party reflects their commitment to advancing justice for Black communities from an intersectional lens. The choices available to Black women are quite limited given their electoral capture by the Democratic Party (Frymer Reference Frymer1999). Even still, Black women voters are not particularly well represented by the Democratic Party, and they do not have a viable alternative. There are a host of issues facing the African American community that are on the fringe of the Democratic Party platform. We expect that higher levels of civic duty distinguish Black women Democrats from both Black male Democrats and white women Democrats given their social location in the race-gender hierarchy. We expect that across strong and weak Democratic partisan affiliations, civic duty is a primary driver of Black women’s participation.

To showcase the factors relevant to Black women’s participation, we contrast Black women with Black men for an intraracial gendered analysis, and Black women with white women for an intergender racial analysis.Footnote 2 We expect that the factors that influence Black women’s participation and vote choice reflect perceptions of voting, rather than strong partisan identity, and the favorability of the Democratic presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton. In our effort to model attachment to the Democratic Party, we examine three dependent variables: (1) Clinton favorability, (2) 2016 turnout, (3) Democratic Party vote choice.

To that end, we generate three testable research hypotheses that outline our expectations:

-

1. Black women who identify as strong Democrats were more favorable toward Clinton compared to Black women who identify as weak Democrats, white women who identify as strong Democrats, and Black men who identify strong Democrats.

-

2. Black women who identify as strong Democrats were more likely to vote in the 2016 election compared to Black men and white women who identify as strong Democrats.

-

3. Black women Democrats view voting as more effective compared to white women Democrats and Black male Democrats, and Black women Democrats view voting as the most effective activity relative to other forms of participation compared to their male counterparts.

-

4. Black women who were least favorable toward Hillary Clinton were more likely to vote for her than Black men and white women who were least favorable toward her.

Research Design and Methods

Understanding Black women’s attachment to the Democratic Party and perceptions of civic duty requires data that include these measures and a significant number of Black women to conduct the analyses. This study uses data from the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS), a cooperative, online, national post–presidential election survey designed by scholars of racial and ethnic politics that was administered between December 3, 2016, and February 15, 2017 (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Vargas and Wong2018). The CMPS includes a large number of Black (n = 3,102), Latino (n = 3,003), and Asian American (n = 3,006) respondents. There is also a sample of white Americans (n = 1,034). The CMPS is a first-of-its-kind survey that includes large numbers of minorities, including voters (n = 6,024) and nonvoters (n = 4,120), that other political surveys lack (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Vargas and Wong2018). Since we are interested in women voters, the CMPS boasts a large number of female respondents across race and ethnicity, including Black women (n = 2,416), Latinas, (n = 2,041), Asian American women (n = 1,800), and white women (n = 643). The data for all the racial and ethnic groups included in the survey were weighted using 2015 American Community Survey data (for further details about survey sampling and methodology, see Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Vargas and Wong2018).

Comparable studies have used the CMPS to understand how Black women’s political ambition derives from their political activism (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Brown, Frasure and Pinderhughes2021), generational differences among Black Americans’ perceptions of American identity (Greene et al. Reference Greene, Gray, Carter and Block2020), and the role of linked fate in candidate evaluations (Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019). The 2016 CMPS is the ideal data set to examine Black women’s attachments to the Democratic Party, as very few surveys include individual-level data with sufficient sample sizes of Black women to disaggregate by other characteristics. However, one drawback is the limited ability to draw comparisons to white Americans, specifically white women, who generally dominate nationally representative social science surveys. This is also a strength of the analyses given our intentions to center Black women and draw conclusions about Black women specifically.

Partisan Identity

Among the 80% of Black women who identify as Democrats, a 57% plurality identify as “strong Democrats.” Among the 72% of Black men who identify as Democrats, only 43% of Black men identify as strong Democrats, followed by 39% and 18% of white women, respectively. Compared to other groups, Black women demonstrate a unique dedication to the Democratic Party. Less than 5% of Black women in the CMPS identify as Republican, and 5% identify with other political parties. Unlike Black women and men, a 37% plurality of white women identify as Republicans. Across all groups, between 11% and 16% identify as independents. Black men and women overwhelmingly identify as Democrats, and white women primarily identify as Republicans.

Candidate Favorability

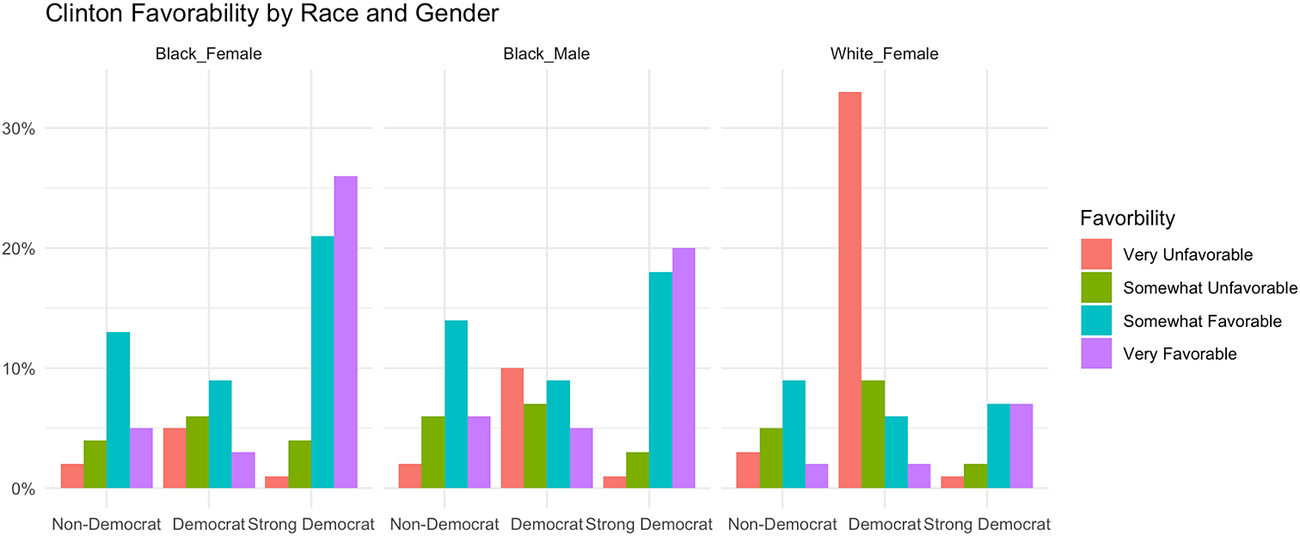

Figure 1 shows Hillary Clinton’s favorability among Black women, Black men, and white women. Across partisan identities, a majority of Black women are somewhat favorable toward Clinton. Black women who identify as strong Democrats were favorable toward Clinton, more so than their Black male counterparts. Across race and gender, partisan identity and intensity are associated with candidate favorability; Black women who identify as strong Democrats are quite like Black males, yet they are drastically different from white women who identify as Democrats. In fact, most white women Democrats were very unfavorable toward Clinton. Black women, by proxy of identifying as strong Democrats, are well entrenched in the Democratic Party, and slightly more so than Black males, and thus more favorable toward Clinton.

Figure 1. Candidate favorability among Black women (n = 2,146), Black men (n = 956), and white women (n = 643) in the CMPS (n = 3,745).

Civic Duty

We examine the perceived effectiveness of voting. We expect that Black women Democrats consider voting to be an effective means to have their voices heard, regardless of their level of support for the Democratic candidate.Footnote 3 The effectiveness question asked, “How effective, if at all, are the following tactics [voting] for getting your voice heard”; the other tactics presented were nonviolent protesting, rioting, and contacting your representatives. We use voting effectiveness relative to other forms of participation, as well as the perceived effectiveness of voting. We standardize the variable between 0 and 1, so that the lowest value represents “less/not effective” and the highest value represents “very/more effective.”

Black women view voting as effective, similar to Black men, but more so than white women. Black men view voting as more effective than other acts compared to Black women (about 53% to 49%). However, when comparing Black women to white women, Black women view voting as a more effective tool (about 49% to 36%). Blacks view nonviolent protest as effective (about 38% and 37%), but only 23% of white women Democrats share that view. We expect that Black women’s belief in voting’s effectiveness operates in distinct ways compared to Black men and white women, despite their perception that nonelectoral forms of participation are overall less effective compared to Black men.

Controls

In the models, we include a standard set of demographic controls used to explain political decision-making (Smets and van Ham Reference Smets and van Ham2013). These vary by the outcome of interest. We include registered (1 = yes), age (1 = 65+), region (1 = South), education (1 = college degree or more), immigrant status (0 = not born in United States), marital status (1 = married), income (1 = $150,000+), and political ideology (0 = conservative, 1 = moderate, 1 = liberal). We also include the importance of gender identity (1 = very important) and linked fate (1 = a lot), church attendance (1 = every week), and state of the national economy (1 = better). We include other political measures such as discussing politics, political interest, supporting a pathway to citizenship, supporting Black Lives Matter, supporting the local police, political efficacy, and the perception that their friends vote. We use these items to account for the impact of existing predispositions, relevant to 2016 campaign discussions, and density of social and political networks. All variables in the analysis are scaled between 0 and 1.

Findings and Discussion

What Factors Influence Favorability toward Hillary Clinton?

First, we explore what factors influenced Clinton’s favorability in the 2016 presidential election. Table 1 reports four ordinary least squares regressions: (1) Black women, (2) white women, (3) Black men, and (4) all.Footnote 4 Across the three race-gender models, and in the full model, identifying as a Democrat is associated with Clinton’s favorability. Only for Black men is a strong Democratic identity (relative to weak) more associated with Clinton’s favorability. Party identification is “the most powerful cue” provided to voters during an election, and partisanship plays a significant role in the evaluation of political candidates (Rahn Reference Rahn1993). The strong Democrat coefficient is largest for white women. Similarly, for white women Democrats, identifying as a strong Democrat (relative to weak) is associated with a 20% increase in Clinton’s favorability. However, for Black women who identify as strong Democrats (relative to weak Democrats), there is only a minor increase in Clinton’s favorability. Intense attachment to the Democratic Party is not the sole factor relevant to shaping Clinton’s favorability. However, descriptively, Black women strong Democrats have the highest favorability toward Clinton compared to white women and Black male Democrats.

Table 1. Predicting support for Hillary Clinton

*** p < .01;

** p < .05;

* p < .1.

Source: 2016 CMPS weighted to 2015 American Community Survey one-year data.

We include policy items that were a part of Clinton’s platform and widely discussed in the 2016 presidential campaign. We find that increased support for the Black Lives Matter movement is associated with Clinton’s favorability, to a greater extent than partisanship. In addition, Black women who rated their friends as “frequent voters” were more likely to favor Clinton. White women who were supportive of Black Lives Matter also favored Clinton; however, there is no meaningful relationship for Black men. For Black men, besides partisanship, the belief that the economy is doing better is associated with increased favorability. Surprisingly, Black women’s linked fate is less associated with Clinton support. This relationship is negative and significant, indicating a near 6% decrease. However, there is no relationship between linked fate for Black men and white women. While partisanship dominates in support for Clinton, there are several other relevant positions that influenced support for her, and these, too, varied across race and gender.

Civic Duty and Turnout among Black Women, White Women, and Black Men

Next, we examine how Clinton favorability, partisan identity, and civic duty are each associated with turnout in the 2016 election (Figure 2). We expect that civic duty—namely, the belief that voting is an effective tool of political expression—has a particular influence on Black women voters, more so than favorability and partisan identity. Black women’s civic duty increases, and so does their likelihood of turning out. Interestingly, we do not find strong evidence of differences between Black women and Black men who view voting as the most effective tool. Black women who view voting as “not too effective” are less inclined to vote compared to Black men. However, Black men who view voting as “not too effective” are more likely to vote than both Black women and white women.

Figure 2. Predicting voting in 2016 election models for Black women, white women, and Black men. Results are presented as marginal effects. All other values are held at their mean. Source: CMPS 2016.

We hypothesized that Black women who identify as strong Democrats would be more likely to vote compared to Black men and white women strong Democrats. We failed to find significant differences between Black women strong and weak Democrats, though Black women strong Democrats were slightly more likely to vote when they reported that voting was very effective. For Black men, non-Democrats were slightly more likely to vote across levels of voting’s effectiveness. However, when we compare Black women to others, we find that Black women strong Democrats were more likely to vote compared to white women and Black males that were favorable to her. We expand on this in the next section.

Clinton Favorability and 2016 Turnout

In Table 2, we examine 2016 turnout with attention to the magnitude of civic duty’s influence. We include three logistic regressions for all registered (1) Black women, (2) white women, and (3) Black males in the CMPS. We focus on variables that correspond to our theory and expectations: (1) partisan identity, (2) Clinton favorability, and (3) civic duty. Overall, we find that Clinton’s favorability, strong partisan identity, and the belief that voting is more effective than protest are associated with Black women’s turnout, but not for white women and Black men. Only for Black women is identifying as a strong Democrat, relative to other partisan identities, strongly and significantly associated with voting in the 2016 election. Black women strong Democrats are 5% more likely to vote compared to their non-Democratic counterparts.

Table 2. Predicting voting in 2016 election

AME = average marginal effects.

* p < .1;

** p < .05;

*** p < .01.

Source: 2016 CMPS weighted to 2015 American Community Survey one-year data.

Second, Black women’s favorability toward Clinton is associated with their 2016 turnout. While Clinton’s favorability is positively associated with Black men’s likelihood to vote, it is an insignificant relationship. Similarly, while there is a positive association between favorability and turnout for white women and Black men, only among Black women is the relationship significant and positive. Black women who were more favorable toward Clinton are about 2% more likely to vote compared to those who are unfavorable, like Black men. However, Clinton’s favorability has less of an effect among white women.

What matters to Black women matters less to white women and Black men. Black men’s partisan identity has an undetectable influence, and civic duty reaches marginal significance with a 7% increase in the likelihood to vote. Among white women, both partisan identity and civic duty have a negligible influence on turnout. Surprisingly, the favorability measure is the least associated with white women’s turnout. While both of these measures are in the expected positive direction, they fail to reach significance. These results suggest that partisan identity drives Black women’s turnout, but to a lesser extent than their commitment to voting and their perceptions of its effectiveness compared to other political acts.

We hypothesized that Black women strong Democrats would be more likely to vote than white women and Black male who identify as strong Democrats. We find evidence that both strong Democratic and weak Democratic Black women were more likely to vote than Black women from other partisan affiliations. When examining the influence of Democratic affiliation on voting for white women and Black men, we find a negligible relationship. Partisan affiliation differentiates Black women’s likelihood of turnout, but it does not for white women and Black men. This means that Black women overall have a moderate likelihood of participating, and identifying as a Democrat increases their propensity to vote relative to other partisan affiliations. The intercept of the models for white women and Black men indicates that, in general, white women’s and Black men’s likelihood of participating is high, and partisan identity is less associated with their turnout. Further, Black women are favorable toward Hillary Clinton, more so than Black men and white women; however, there is a weak relationship between favorability and turnout. For Black women, identifying as a strong Democrat, relative to other partisan identities, and having favorability toward Clinton is strongly associated with their turnout, but this pattern does not present for white women and Black men.

Next, we turn to our analysis of civic duty and voting. There is mixed support among Black women and Black men that voting is an effective political activity. Black women who reported that voting is more effective than protesting are 10 percentage points more likely to vote than those that do not. Surprisingly, Black men view nonviolent protesting as more effective than voting, and we observe that only when Black men view voting as more effective than rioting is there an increase in their likelihood of voting. Civic duty bears no significance for white women’s likelihood of voting. Given protest as a familiar form of political expression among Black people (Tate Reference Tate1994), Black women, but not Black men, who view voting as more effective than protesting are marginally more inclined to vote because of it. These findings signal that Black women’s civic duty to vote trumps their engagement in nonelectoral politics as an effective method of engagement.

Predicting Democratic Vote Choice in 2016

Lastly, we examine Democratic vote choice among Black women, white women, and Black men, across levels of Clinton favorability among strong and weak Democrats. We hypothesized that even Black women who were least favorable toward Clinton would be more inclined to vote for her compared to Black women who were least supportive of Clinton compared to similarly situated white women and Black men. In Figure 3, we show that an increase in favorability toward Clinton is associated with a greater likelihood of voting for her. However, we do not find that the least supportive Black women differed from white women and Black men. In fact, Black male Democrats who were the least supportive were more inclined to vote for Clinton than Black women. We find subtle differences among white women and Black male weak Democrats and strong Democrats, across levels of favorability. However, Black women with higher Clinton favorability casted their ballots for her at the highest rates. Black women Democrats who were somewhat favorable toward Clinton were slightly more likely than white women to support her, but less likely compared to Black men. Black women’s vote choice is a product of partisan and nonpartisan motivations, and less about their candidate perceptions.

Figure 3. Likelihood of Clinton vote choice by Clinton support levels among Democrats.

Conclusion

In 1982, Black women’s studies scholars Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Scott (Reference Hull, Scott and Smith2015) published a groundbreaking edited volume on the status of Black women in academic research. All the Men Are Black, All the Women Are White remains a position of research that fails to incorporate an intersectional analysis to understand Black women’s relationship to the Democratic Party, democracy, and the democratic process. In this article, we have demonstrated that Black women view voting as an effective tool for having their voices heard compared to protesting, and that Black women overwhelmingly identify as strong Democrats and exhibit favorability toward Democratic candidates. We showed that while favorability is a vital component of vote choice, it is one of many considerations for Black women. Primarily, we show that the perception of voting as an effective tool to have their voice heard is largely the reason why Black women participate. Despite greater affiliation with the Democratic Party and primary identification as strong Democrats, not all Black women hold favorable views toward Democratic candidates. We find that Black women’s views toward the act of voting have behavioral implications in ways that we do not observe for Black men and white women. We compared Black women to other strong Democrats to get a better sense of whether, or how, electoral capture by the Democratic Party operates. We examined how Black women are bound by race in some instances and how they differ from Black men. Lastly, we expanded on our understanding of electoral participation by looking at Black women through the lens of gender, compared to white women.

When it comes to political behavior, Black women have always occupied a distinct and important role in political advocacy both inside and outside the Democratic Party (Ransby Reference Ransby2003). The theory of intersectionality captures the unique challenges that Black women face in the political process at the intersection of race and gender (Brown Reference Brown2014; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Crowder Reference Crowder2023; Smooth Reference Smooth2006). Neither gender nor race alone accurately characterizes the complexity of voting behavior and decision-making as it pertains to political participation. Rather than focusing exclusively on gender or exclusively on race, intersectionality recognizes how the experiences of Black women are distinct and noncollapsible into these neat categories of identity and are similar to standing at the middle of a four-way intersection. Thus, for Black women, it is imperative to understand Black women’s racialized experiences as gendered and gendered experiences are racialized with respect to their political participation and efficacy. The primary texts on African American partisan identification have neglected the intersectional experiences of Black women informing their affective attachments toward the party (White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020). This article starts to fill this void.

Our findings demonstrate the complexities of an intersectional approach. Pertaining to both candidate evaluations, perceptions of voting’s effectiveness, and partisan identification, both racial and gendered identities matter. Gender interacts with race in a dynamic fashion, and the context in which these identities meet is increasingly important to politics. We demonstrated this dynamism in the 2016 election; however, we believe that this electoral context rendered gender, race, and ethnicity particularly salient in ways that will likely influence later electoral contests. Conducting intersectional analyses and centering Black women unearths their dissimilarity from their Black male and white female counterparts, both of whom dominate discussions of race and gender, respectively.

The findings from this study have implications for the evaluations of women candidates for highly visible political offices. In 2020, Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign was subject to criticism, concerns about her electability, and disinformation targeted to Black male voters. The patterns unearthed in our analyses may shed light on how Black male and white female voters evaluated Kamala Harris, and whether higher levels of civic duty outweighed partisan considerations. Similarly, as candidates in the Democratic Party diversifies, candidate favorability may shift and mobilize voters differently across race, gender, and partisan intensity.

Despite these implications, our study has limitations with respect to favorability that warrant discussion. The CMPS is a postelection study, and we are unable to detect variability in candidate evaluations over the course of the campaign as new information is revealed about the candidates. Future studies should examine whether the campaign horserace influences Black female voters’ candidate perceptions. Second, we examine one dimension of candidate evaluations: favorability. Other evaluative dimensions of candidates, such as competence and warmth, may be more influential toward the nuanced, and complicated views of Hillary Clinton. Future surveys must incorporate specific candidate qualities to best understand what factors into candidate favorability.

Despite the limitations, this paper is one of the few whose central focus is on the electoral behavior of Black women and their relation to party politics in the United States. After the election and reelection of Barack Obama, the focus on Black voters took a more prominent role in American politics, but often this came through discounting the role that gender has played for Black women. For candidates who champion issues in which women are the primary beneficiaries, race often divides the opinions of women. By examining differences among Black and white women, we demonstrate some areas of difference that have political consequences. The salience of gender among women of various racial backgrounds leaves fertile ground for further exploration.

In addition, we illustrated other intraracial and intragendered findings that were not the primary focus of the article. We show that linked fate operates in a nuanced manner, given the dependent variable of interest. For Democratic candidate favorability, linked fate varied between Black men and Black women. With respect to Democratic vote choice, linked fate has a consistently positive effect that varies in magnitude—moving from weak to strong. As linked fate is a ubiquitous explanation of Black political behavior and preferences, its gendered effects demand a reexploration. Second, we encountered a finding that reifies the distinct preferences between Black people in the United States, those who have immigrated from the Caribbean or continental Africa, and those who are descendants of U.S. chattel slavery. Even more, the finding of immigrants has gendered contours.

Overall, we find that the relationship between civic duty, partisanship, and Clinton favorability operate in distinct ways for Black women’s vote choice. While we find that Black women exhibit elevated levels of Democratic partisanship and continue to view voting as effective, one must ask how long Black women will continue serving as the thankless keepers of democracy and the Democratic Party.