Mental health services represent a significant and growing component of healthcare systems, with approximately 1 in 6 adults affected by mental health conditions and 14% of healthcare expenditure attributed to mental healthcare. Reference Baker and Kirk-Wade1 Early identification and risk stratification are crucial to improving outcomes, yet predictive modelling in routine mental healthcare remains under-utilised compared with other medical specialties. Colling et al explored three potential outcomes for predictive modelling in this context, ultimately finding that high-intensity service use was the most effective target for prediction, outperforming the other outcomes of length of stay and readmission risk. Reference Colling, Khondoker, Patel, Fok, Harland and Broadbent2 This reflects a broader trend of increasing interest in leveraging machine learning and electronic health record (EHR) data for risk prediction, although mental health presents unique challenges, including data fragmentation, complex care pathways and variable diagnostic coding. Reference Ostojic, Lalousis, Donohoe and Morris3 Despite the growing availability of EHR data, its potential for predictive modelling in mental health has yet to be fully realised, highlighting a critical opportunity for further research and implementation.

Building on the earlier work of Colling et al, this project similarly aimed to evaluate the performance of a predictive algorithm targeted at adults 3 months following their first presentation to mental health services, and sought to identify those at risk of requiring high-intensity mental healthcare (defined as being in the top decile of expenditure) over the subsequent 12-month period. In this retrospective cohort study, a variety of predictor variables including demographic, clinical and service use factors were examined to determine the likelihood of a given patient receiving high-intensity service use, based on information derived from their first 3 months of care.

Method

Setting

This analysis was conducted at the South London and Maudsley (SLaM) National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, a specialist mental healthcare provider serving a catchment population of 1.3 million residents in the south London boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham and Croydon. Data were extracted using SLaM’s Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) platform, which was first developed in 2008 and facilitates the real-time retrieval of anonymised patient information from the mental health EHR. 4

Index date, predictors and outcome

The index date was defined as 3 months following a patient’s initial assessment at SLaM. All patients aged 18 years and older at the time of first assessment, and with an accepted referral to SLaM, were considered for inclusion. Predictions were made on the index date using information collected during the first 3 months of care, with the aim of forecasting high-intensity service use over the subsequent 12 months. To ensure accuracy of modelling, only those patients who had received at least 3 months of care prior to the index date were included. Because data were extracted up to 31 December 2024, the cut-off for the index date was set to 31 December 2023 (corresponding to patients first assessed by 30 September 2023).

Predictor variables were consistent with the previous work of Colling et al which, in turn, had been informed by a literature review of the field and multidisciplinary project meetings. Reference Colling, Khondoker, Patel, Fok, Harland and Broadbent2 These variables can be classified broadly into demographic factors (e.g. a patient’s ethnicity, age at first assessment, gender and marital status); service user factors (e.g. number of teams that a patient was under; number of in-patient admissions in the 3 months following first assessment, and the total number of in-patient and community contact days during this time); and clinical factors (e.g. a patient’s diagnosis and the recorded risk of suicide, violence and neglect). Additionally, metadata from pre-existing natural language-processing (NLP) algorithms were considered, including routinely extracted mentions of over 50 symptoms from the EHR, categorised into catatonic, depressive, disorganisation, manic, negative psychotic and positive psychotic scales. These NLP-derived variables were generated using supervised machine learning techniques, with each ascertaining mentions of experiences of the given symptom in the health record. Specifications and performance data for each NLP algorithm are detailed in an open-access online library, as is the categorisation of symptoms into the above scales, which are simple quantifications of the number of different symptoms (one scale point per symptom) within a given category recorded in text fields over a given time period (in this case, over the 3 months following first contact). 5

A total of 87 predictor variables were initially included within the prediction model (see supplementary data for the full list of original variables). A primary data-preprocessing step involved reclassifying patients’ episode locations (i.e. type of service and team providing this) into broader location categories. There were approximately 400 unique episode locations in the data extract, which were placed into 1 of 21 categories including a not-assigned category (i.e. patients whose episode location at 3 months was blank) and an unknown category (i.e. patients whose episode location could not be assigned to any of the categories). This reclassification process was performed using a combination of domain expertise and manual checks, guided by an aspiration to maximise potential reproducibility when translating this work to other sites (a full list of reclassified location categories is also provided in the supplementary file).

The outcome of interest, high-intensity service use, was defined as the top decile of service costs, calculated using the University of Kent compendium of unit costs, and a patient’s total number of service use days (across the following settings: in-patient, community, crisis and home treatment teams). 6 The primary outcome is binary, classifying individuals as either high-cost (falling within the top decile of healthcare expenditure) or not. This approach was chosen for its clinical utility, because it enables a focus on the highest-acuity service users who are most likely to require targeted interventions. While a continuous model predicting incremental changes in expenditure could offer more granular insights, this was felt to be less actionable in a healthcare setting where resource allocation decisions prioritise those with the greatest needs. It was accepted that this binary classification would introduce limitations, because individuals just outside the top decile may still have significant healthcare needs but that would not be identified as being high-cost. This trade-off underscores the importance of considering model outputs alongside clinical judgement, and exploring complementary risk stratification methods to account for near-threshold cases.

Statistical analysis and predictive model building

All analyses were performed using Python 3.11.7 (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, Oregon, USA; see https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3117) on Jupyter Notebook 7.0.8 (Jupyter Development Team, Berkeley, California, USA; see https://jupyter.org) for Windows. The prediction model was trained and tested on patients first assessed in the 5-year period 2007–2011. In total, 18 869 patients were assessed during this time and the model was trained and tested using an 80:20 split, such that it was trained on 15 079 patients and tested on 3770 patients. Subsequent validations took place in the time periods 2012–2017 and 2018–2023. In the latter validation, additional analysis was carried out, both retaining and omitting patients assessed in 2020–2021, because it was envisaged that the period at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic would be characterised by atypical service use, which might have interfered with prediction modelling.

The default preferred prediction approach was a logistic regression model, the rationale for this choice being based on its interpretability and efficiency. It was determined that alternative models would be considered only if these showed demonstrably superior performance, particularly in terms of sensitivity.

Sensitivity was prioritised over specificity, because the primary clinical goal was to identify as many at-risk service users as possible for early review and intervention. In this context, a false positive (flagging a patient who ultimately does not require high-intensity care) carries lower clinical risk than a false negative (i.e. a patient whose needs are missed entirely). Moreover, it was reasoned that resource allocation decisions would not be based solely on model output but would, instead, rely on clinical judgement in conjunction with the prediction, ensuring that those flagged for review would undergo appropriate clinical assessment before any substantial changes to their care pathway.

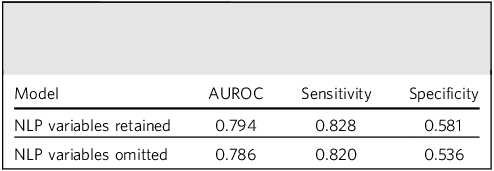

The primary logistic regression model was initially built using all 87 predictor variables. Balanced sampling was used to ensure that ‘not high-intensity’ and ‘high-intensity’ outcomes were represented equally, recognising that, by definition, the latter comprised approximately 10% of the overall data-set, and seeking to improve sensitivity for this class. Correlation matrices were further employed to identify pairs of categorical variables with high collinearity (correlation >0.8), which were then removed. NLP-derived variables were included in initial models but later omitted following performance comparisons (Table 1). Despite moderate gains in sensitivity and area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC), it was further envisaged that extraction of these variables would be more complex if the model was applied more generally in other sites, and therefore these were not considered further in the absence of a substantial impact on performance.

Table 1 Comparison of model performance before and after omission of natural language-processing (NLP)-derived variables

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic.

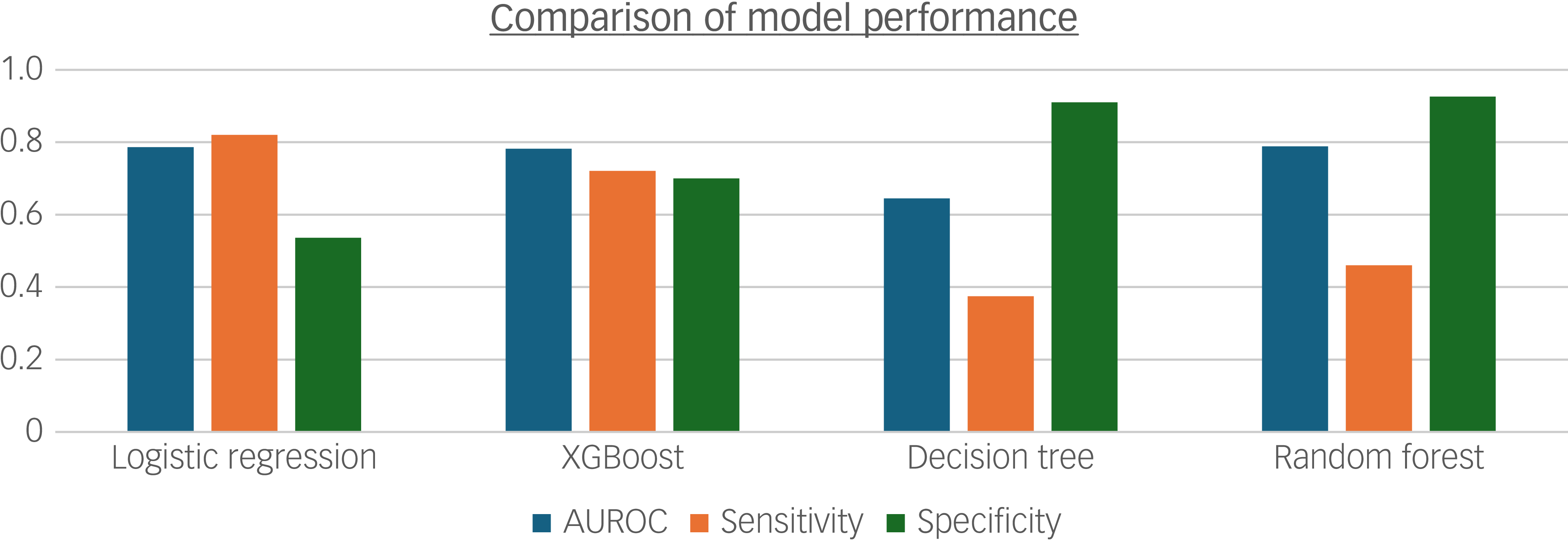

The final model was further compared against other predictive modelling techniques, namely XGBoost, random forest and decision tree, developed using the same feature set on data between 2007 and 2011 (Fig. 1). This approach permitted direct comparison of algorithm performance on consistent inputs, although it is acknowledged that some models may be more robust to collinearity and derive greater predictive value from NLP-derived variables than logistic regression; as such, the relative performance of these models may be underestimated when restricted to the reduced feature set used in the final logistic regression model. In summary, logistic regression outperformed the other models, achieving the highest sensitivity and AUROC. Although specificity was higher for the decision tree and random forest models, sensitivity was prioritised for the reasons cited earlier. Furthermore, the logistic model was retained for its interpretability and efficiency, considering the pragmatics of potential implementation, compared with the other more resource-intensive techniques.

Fig. 1 Bar chart comparing model performance for 2007–2011 data with identical inputs for logistic regression, XGBoost, decision tree and random forest models. AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic.

Results

Summary statistics

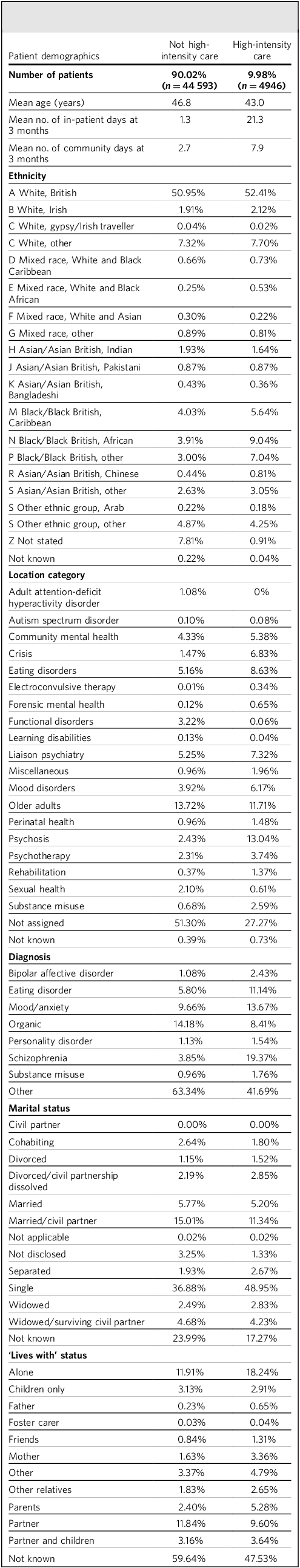

Table 2 provides a summary of the baseline variables contained within the data-set, broken down by future high-intensity care (HIC) versus non-HIC service users. The sample comprised 49 539 patients 3 months following first referral, with 9.98% (4946) ending up with a HIC receipt over the subsequent 12 months. Compared with the remainder, future HIC users were younger and experienced longer in-patient stays and community contact days in the first 3 months. While White British patients represent the largest ethnic group overall, Black patients were over-represented in those with future HIC use. Regarding service use, most patients were not assigned to a specific category at 3 months. Among those who were, higher proportions of those with future HIC received psychosis, forensic mental health and electroconvulsive therapy services. Schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and eating disorders were more common in those with future HIC use, and organic disorders less common. Furthermore, separated, divorced or single marital status was also more common in those with future HIC use.

Table 2 Sample characteristics comparing patients with/without future high-intensity care use

Model performance

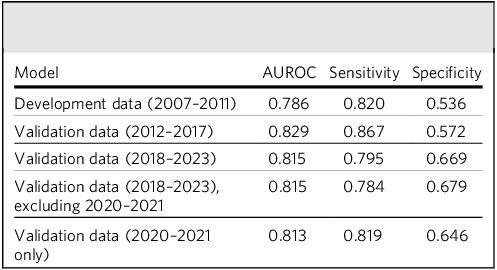

In regard to index dates during the model development period (2007–2011), the model achieved an AUROC of 0.79, with a sensitivity of 0.82 and specificity of 0.54 at an optimal cut-off. The model built on 2007–2011 data continued to perform well in subsequent evaluation time periods, between both 2012 and 2017 and 2018 and 2023. The omission of patients first assessed in 2020–2021 from the latter validation had no substantial impact on performance metrics, and the model still achieved relatively high performance in the 2020–2021 period alone (Table 3).

Table 3 Model performance in development and subsequent validation periods

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic.

Within the algorithm derived from the development sample (see Supplementary Table 1), the variables most strongly predictive of HIC use were number of contact days (both in-patient and in the community); eating disorder or schizophrenia diagnoses; care under a mood disorder or psychosis team; service users in whom a risk assessment was conducted during the first 90 days; and those living alone. The variables most associated with not requiring HIC were receipt of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or functional disorder services, organic disorder diagnosis and clients with low levels of service use (across both in-patient and community settings); in addition, this latter group were also more likely to have unknown or missing status on variables, indicative of less complete records at the 3-month prediction point.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the predictive performance of a logistic regression model for identification of high-intensity service use among patients 3 months following a first mental healthcare episode. Our findings evaluate the clinical utility of this approach while also raising areas for further research.

Model choice and suitability of logistic regression

Logistic regression was selected as the primary model due to its balance of interpretability, efficiency and robustness when handling a large number of predictor variables. Compared with alternative techniques such as XGBoost, random forest or decision tree, logistic regression provided a clear understanding of the relationships between predictor variables and outcomes. In a clinical setting, where transparent decision-making is critical, the ability to directly interpret coefficients (e.g. quantifying the impact of high service use in the first 3 months) makes logistic regression particularly appealing.

The role and limitations of NLP-derived variables

Our analysis initially incorporated a range of NLP-derived variables. However, the additive value of these variables to the model’s overall sensitivity and AUROC was limited. It is important to note, however, that despite their marginal contribution to the prediction metrics, NLP-derived features may have clinical utility – particularly in explaining misclassified cases. For example, detailed symptom descriptions extracted from free-text notes might provide contextual insights into why certain patients were flagged incorrectly, potentially guiding clinicians in understanding atypical presentations or complex cases. This is scheduled for further evaluation in advance of any consideration for implementation.

Interpreting the predictor variables

Interpretation of predictor variables revealed several clinically relevant associations. As expected, a high volume of service use in the initial 3 months strongly predicted continued high-intensity use over the subsequent 12 months. This aligns with the notion that early patterns of service engagement often presage later, more intensive, resource use. Additionally, the finding that conditions such as schizophrenia and eating disorders are associated with high service costs is consistent with existing literature on the management challenges and resource demands of these diagnoses. Reference Kotzeva, Mittal, Desai, Judge and Samanta7,Reference Streatfeild, Hickson, Austin, Hutcheson, Kandel and Lampert8 Conversely, conditions such as ADHD were linked with lower likelihood of high-intensity service use, which may well be accounted for by large numbers receiving care episodes primarily for diagnosis rather than for longer-term management; this may also account for the lower risk in patients with organic disorder diagnoses.

Ethnicity and high-intensity service use

The ethnicity of service users is a key consideration for the interpretation and generalisability of our findings. While White British patients constituted the largest group overall, Black patients were over-represented among the HIC group compared with the non-HIC group. This pattern is consistent with long-standing national evidence showing that people from Black ethnic groups are more likely to access mental health services through crisis pathways, and to use higher-acuity services. Reference Bansal, Karlsen, Sashidharan, Cohen, Chew-Graham and Malpass9 These disparities may be driven by myriad complex, interdependent factors, including differences in socioeconomic status, institutional barriers to accessing timely mental healthcare and social adversity. Reference Gilburt and Mallorie10 Addressing these ethnic inequities in mental health outcomes requires not only robust risk prediction but also redoubled efforts to deliver culturally competent care and lowering of healthcare access barriers. It is also clearly important that predictive algorithms highlighting outcome inequalities do not further stigmatise patients ascertained as being at increased risk but, instead, are used to support accessible interventions to reduce inequalities.

Exploring misclassification: future directions

A predictive algorithm alone, however high the performance, is unlikely to be sufficiently informative for immediate clinical implementation. In part, it would be unethical to attach predictive labels at an individual level without a clear strategy for intervention. In addition, further work is warranted to clarify factors that might influence the model’s accuracy. In particular, further analysis of false positive and false negative predictions presents a valuable opportunity for refining the predictive model, communicating factors influencing its accuracy as well as providing potential information on clinical workflows that might be developed as interventions. Future research should, for example, include a detailed consideration of false positive cases – patients flagged as high-intensity users at 3 months who do not sustain this level of service use at 12 months. This may shed light on whether early interventions, such as care coordination or proactive clinician engagement, might play a role in altering the clinical trajectory. Additionally, examining patients who were misclassified as low risk (false negatives) may help to identify factors or post-prediction events that contributed to their eventual high-intensity status. It may also be important to filter the cohort by in-patient status at the date the prediction is made, to determine how additional in-patient days contribute to crossing the high-cost threshold, because these predictive processes are likely to differ from those in community services.

Mutable versus immutable factors

A critical aspect of our discussion involves differentiating between mutable and immutable predictors. Certain factors, such as a patient’s primary diagnosis or the inherent cost associated with specific services, are immutable and must be managed within the broader context of clinical care. By contrast, other factors – such as early service use – might be modifiable through timely and targeted interventions. This distinction is crucial, because it not only informs resource allocation but also underscores the need for integrating predictive insights with clinical judgement and tailored treatment planning.

Implications for care delivery and service redesign

The strong predictive performance of this model across multiple validation periods supports its potential use in routine mental healthcare for risk stratification, proactive care planning and resource allocation. Prediction models may aid clinical decision-making by classifying service users into discrete subgroups or personalised care pathways, enabling services to target interventions towards the highest-acuity users. Reference Meehan, Lewis, Fazel, Fusar-Poli, Steyerberg and Stahl11

For patients predicted to be high-intensity service users, interventions such as intensive case management (ICM) and enhanced care coordination may be particularly valuable. ICM has been shown to reduce hospitalisation and improve engagement among people with severe mental illness, with particular effectiveness among those with high baseline hospital use. Reference Dieterich, Irving, Bergman, Khokhar, Park and Marshall12 Care coordination activities include care allocation developing personalised care plans, increasing contact frequency, monitoring and follow-up care and linking to community resources, all of which may help to prevent escalation to crisis or prolonged in-patient admissions. Reference Hynes and Thomas13

This predictive model was designed in such a way as to facilitate its potential implementation and further evaluation in other mental health services, because it relies on what would be expected to be routinely collected data such as diagnoses, service contacts and demographic characteristics. The use of a logistic regression model (compared with other, more complex, machine learning techniques) maximises compatibility with standard analytics platforms and reporting dashboards, without the need for advanced computational resources. In addition, the use of earlier clinical data for model training and later clinical data for evaluation was considered the simplest and most replicable approach for use at other sites.

Reproducibility and generalisability

SLaM serves a socioeconomically diverse population, with a catchment spanning four London boroughs and a range of clinical presentations and varying levels of deprivation. This breadth of coverage, and the variety of relatively independent services captured, strengthen the generalisability of the study’s findings for other settings, and may mitigate concerns about the area being homogeneous and unrepresentative. Nevertheless, external validation in more rural or less diverse settings remains important in regard to evaluation of reproducibility elsewhere. Moreover, variations in EHR data structures and local clinical practices and pathways may further influence model performance when deployed at other institutions. Therefore, future work should aim to validate and potentially recalibrate the model in diverse settings, to enhance its generalisability and practical impact.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including the use of a large, well-characterised cohort and a rigorous validation framework. The interpretability of the logistic regression model facilitates its potential integration into clinical decision-making processes. However, some limitations exist. The exclusion of certain nuanced NLP-derived variables, although justified by their limited additive predictive value, may have inadvertently omitted contextual factors that could be informative in specific subgroups. Additionally, the binary outcome definition may oversimplify the spectrum of healthcare needs, potentially overlooking patients who fall just outside the high-intensity threshold. These limitations highlight the importance of complementary risk-stratification methods and iterative model refinement.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

As part of this work, a patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) session was conducted in partnership with the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). A committee of service users and expert lay members was provided with an overview of this project, and their feedback was obtained regarding the perceived clinical utility of this work and foreseeable barriers to implementation, as well as suggestions for the direction of travel for this study. The session was a useful exercise in sense-checking the project’s aims, and brought to light issues of bias, user training and retaining the focus of clinical outcomes rather than on cost as the primary driver. For example, participants observed that patients who may have had adverse experiences or trauma associated with service use in the past may be less likely to seek care, and were therefore not flagged as high-intensity users despite being potentially quite unwell. They further noted that clinicians and other members of the care team will require training around model design, explainability and the variables contained within the model’s prediction, in order to yield meaningful service improvements. We will continue to engage closely with the PPIE committee, both at SLaM and elsewhere, as this body of work develops to ensure its acceptability, safety and utility.

In summary, this study demonstrates that a relatively simple logistic regression model, leveraging a range of demographic, clinical and service use predictors, can effectively identify mental health patients shortly after first referral who are at risk of subsequent high-intensity service use. The model, validated across multiple time periods, including during the COVID-19 pandemic, achieved robust performance metrics (AUROC ranging from 0.79 to 0.83, with high sensitivity throughout), highlighting its potential clinical utility. While the exclusion of certain NLP-derived features reflects practical challenges in EHR data extraction, the findings highlight critical areas for early intervention and suggest opportunities for further refinement and validation in diverse healthcare settings.

About the authors

Bharadwaj V. Chada is an Honorary AI Research Fellow working across the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IOPPN), King’s College London, and the Clinical Informatics Service at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM NHSFT). He is also a General Practice (GP) Registrar in North West London, and Clinical AI Lead at Kent Surrey Sussex Health Innovation Network (KSS HIN). Robert Stewart is Professor of Epidemiology and Clinical Informatics at the IOPPN, King’s College London, Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist at SLaM NHSFT, and academic lead for the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) application. James Lai is a Postgraduate Doctoral Research Scholar at the Department of Bioengineering – Faculty of Engineering, Imperial College London, Emergency Medicine Specialty Registrar, and Honorary Clinical Lecturer at Queen Mary University of London.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2025.10205.

Data availability

Data for this study were extracted from SLaM electronic health records using the CRIS system. Metadata, including NLP variables, were generated using the TextHunter text-mining tool. All data access and analysis were conducted within a secure virtual desktop environment (Windows App, formerly accessed via remote desktop), with no data leaving the secure system. Only credentialled researchers with appropriate approval (e.g. research passport and CRIS training) had access to the data. Data preprocessing and analysis were conducted using Python and Microsoft Excel. Due to data governance and confidentiality policies, the data are not publicly available but can be accessed by qualified researchers via SLaM CRIS, subject to institutional approvals and data access agreements.

Author contributions

B.V.C. conducted data preprocessing and analysis, led PPIE discussions and was responsible for drafting and preparing the manuscript. R.S. provided project supervision, subject matter expertise and strategic guidance throughout, contributing to the refinement of objectives and interpretation of results, as well as manuscript revisions. J.L. contributed to initial data preprocessing and supported manuscript authorship and revisions.

Funding

R.S. is part-funded by the following organisations: (a) the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at the SLaM NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London; (b) the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; (c) UKRI – Medical Research Council through the DATAMIND HDR UK Mental Health Data Hub (MRC reference no. MR/W014386); (d) the UK Prevention Research Partnership (Violence, Health and Society, no. MR-VO49879/1), an initiative funded by UK Research and Innovation Councils, the Department of Health and Social Care (England) and the UK devolved administrations, and by leading health research charities; and (e) the NIHR HealthTech Research Centre in Brain Health. This research was carried out by B.V.C. and J.L. while in receipt of the NHS Fellowship in Clinical Artificial Intelligence, funded by the NHS Digital Academy and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.