Music offered a variety of appealing careers for women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whether teaching, performing in various capacities, composing, putting their musical ability to use in music retail, or — as I will suggest — in music publishing. The present article explores some of these activities in the context of the women musicians related to the Scottish music publishers Mozart Allan, James Kerr, and the Logan brothers, along with another woman who not only published with the first two of these, but also embarked upon self-publication. It offers a picture of the ways in which a woman could put her musical talents to remunerative use during this era, including through a musical portfolio career. Some women may have dedicated their careers solely to teaching, performance, or composition, but others were clearly not specialists in one sphere.

Just as the roles of governess or schoolmistress suited an educated woman needing an income, so teaching music suited a woman with musical ability. Music had been a necessary social accomplishment and a sign of gentility since the Georgian era. Cyril Ehrlich’s monograph on the music profession in Britain sheds light on how much women music teachers dominated the scene in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain, and, reflecting this, how young female singers and pianists predominated in the young Royal College of Music, founded in 1882.Footnote 1

The enthusiasm for piano playing as a marker of women’s respectability, social standing, and taste was plainly good for the sheet music retail trade. As I shall outline, Kate Logan (wife of David Logan) ran her own music shop, while Mary Kerr (wife of James Kerr) and Euphemia Allan (Mozart Allan’s sister) could well have been involved in their family retail concerns, despite their roles being undefined. Indeed, contemporary newspapers confirm that the practice of employing a pianist to demonstrate new music on the shop floor was quite common in Scotland by the last third of the nineteenth century, notably by retailer James Macbeth in Aberdeen and Methven Simpson in Dundee.Footnote 2 Whether women were involved in demonstrating music in Scotland has not yet been proven, but this might feasibly have been another career option.Footnote 3

The subject of women in music is now a well-established field, to the extent that the arguments around the difficulties experienced by women trying to establish themselves, particularly as composers of large-scale forms, hardly need rehearsing here.Footnote 4 (Indeed, the women discussed in the present article were not such composers.) That composers among studies of women in music should command the most attention is unsurprising, considering the historical focus on composers in musicology. But women were widely engaged in other musical spheres too, such as providing music for dances or playing for the new silent films, whether as pianists, organists, or in cinema orchestras. Indeed, Kate Logan was a dance pianist and band leader, and Maud Kerr may well have played in silent films overseas.

Book historians have certainly turned their attention to women involved in book publishing, the latest extensive offering being The Edinburgh Companion to Women in Publishing, 1900–2020. Footnote 5 While the history of music publishing runs in parallel with book publishing, the two are seldom considered side by side in scholarly discussions; printed music is plainly a very different product from mainstream reading matter. The Edinburgh Companion makes no mention either of women publishing music or indeed of Scottish book or music publishers.

Researching Scottish music publishing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries occasions a careful examination not only of bibliographical but also of census records and other genealogical data, in order to learn more about the men heading the most notable firms.Footnote 6 Through this exploration, it becomes apparent that there were also women — wives, sisters, and aunts — whose musical expertise would have helped their families, while one woman’s daughter in turn benefited from advanced tuition and pursued a performing career herself.

I take a similar approach to Leah Broad in her recent Quartet by examining the parallel lives of a small number of musical women. My subjects, however, were neither composers of significant musical works nor performers of high repute, nor even nationally famous instrumental teachers; their achievements are on a much smaller scale. Nonetheless, the evidence that survives about the lives of these women suggests that we may have underestimated the ways in which late-Victorian and Edwardian Scotswomen used their musicianship for careers which were more multifaceted than we may have assumed, and certainly went beyond piano teaching.

Each of the five women discussed in this article shared family connections with the publishing houses, and/or were published by them, and sufficient materials survive to inform a closer study of their careers. All but one had a Glasgow connection at some point, and all occupied that somewhat fluid space between skilled working class and lower middle class. Their importance is in bringing to our attention the varied components which went into satisfying portfolio careers for women of a less elevated standing. Their need to earn an income coincided with their musical aptitude, and the opportunity to profit from a personal interest was probably only open to a few fortunate women of that era. Four of the five were initially or primarily piano teachers, but all seem to have engaged in other aspects of the music trade at various points in their lives.

Mary Kerr (c. 1848–1908) taught the piano in Glasgow before she married, and was recorded as ‘music publisher’ on her death certificate. One of her daughters, Maud Speirs Kerr (1877–1923), studied at the newly founded Glasgow Athenaeum School of Music (today the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland). She used her talents as a performer to support herself after her first marriage ended, and continued her vocation after remarriage. Euphemia Allan (1861–1948) grew up in Glasgow, taught piano in middle age, and was recorded as ‘music publisher (retired)’ on her death certificate. Kate Logan (née MacLernan) (1862–1936) was raised in Inverness and taught the piano before marriage. Up in the Highlands, Logan was a doyenne of the Scottish country dance scene and had her own successful band.Footnote 7 Rose Buchanan Smith (1870–1942) was not a member of a publishing family; she moved to Glasgow with her widowed mother and her sister in childhood. After her marriage, she continued piano teaching and published work with the aforementioned Kerrs and Mozart Allan; she later established her own small self-publishing imprint and wrote music for variety theatre artistes.

Euphemia Allan and Rose Smith composed work of a lightweight and often ephemeral nature, best described as ‘light music’ or ‘entertainment music’. Derek Scott alludes to the popularity of waltz orchestras and ladies’ orchestras, which played a repertoire of dance music and overtures in leisure contexts such as spas, parks, and restaurants, with the implication that this was often background music or ‘easy listening’.Footnote 8 Indeed, as we shall see, Smith may have written one of her dance tunes in response to a ladies’ orchestra visiting Glasgow when she was a young woman. Allan, hiding behind pseudonyms and anonymity, may have had editorial input to the family publishing firm; by comparison, Smith had a more public profile, retaining her birth name for her published compositions and placing advertisements in The Era, a theatrical newspaper.

There is no firm evidence suggesting that any one of these individuals extended a helping hand to another. However, they possibly knew of these other women: Allan, Smith, and Logan were all born within the same decade, are likely to have shared common acquaintances, and Allan’s brother’s firm published some of Smith’s music. Meanwhile, Maud Kerr, seven years younger than Smith, nonetheless followed behind her to study at the Athenaeum only two years later, and was taught by the same piano teacher.

Considered together as a group, these women, clearly educated and showing musical prowess, give us insight into the various ways an upper working-class or lower middle-class woman could use her talents not only to earn an income, but to construct a meaningful career in turn-of-the-century Scotland, whether in the urban central belt or the more remote Scottish Highlands. My focus on activity in Scotland (indeed, mainly in Glasgow) offers new perspectives on women’s careers while at the same time pointing to broader contemporary trends, such as the increasing numbers of women attending music colleges, Scots emigrating for personal betterment, and in one case, the embracing of new recording technology to make records of a popular export: Scottish dance music.

Mary McKerrow (Mrs James S. Kerr)

While there is very little information about any aspect of Mary McKerrow’s life after her marriage, we can infer that her former profession not only gave her informed insight into her husband’s business, but also meant that their family grew up in a home where music was highly valued. From at least 1868 until her marriage to James Speirs Kerr in 1874, McKerrow advertised in the Glasgow Post Office Directory as a piano teacher. Her father managed Park House (sometimes spelled Parkhouse) Colour Works, a paint factory at 97 Portman Street, not far from Paisley Road. The family seems to have lived on site; McKerrow’s wedding was conducted at home, in a Wesleyan Methodist ceremony. From 1872, James Kerr had advertised as a piano tuner, but by the time he married, he was running the London Pianoforte Warehouse from his address in Pollok Street, his new title of ‘master pianoforte maker’ denoting vocational progress. Within a year or so, he was also publishing dance music. Four violin books, Kerr’s Merry Melodies (1885–c. 1914), achieved lasting fame, with a single piano volume of Merry Melodies also appearing, in 1887. By 1877 the family was living in Paisley Road near his latest premises, and their daughter Maud was born that year.Footnote 9 Their first son, Vincent, was born in 1880, and two more children followed; by 1891, they had moved to a home that would also accommodate Mary’s mother and a servant.

There is nothing to indicate that McKerrow continued piano teaching after marriage, but considering their subsequent careers, she is likely to have encouraged her children in their musical education or even taught them herself. Besides Maud becoming a professional musician, Vincent became a cinema pianist and musical director, first in Glasgow and then in Dundee, also arranging musicians for gigs and playing them himself. By the 1920s, his younger brother, James, was a musician in San Francisco. Only their sister Mary appears not to have been involved in music.

James Kerr died in 1893 at the age of 52, at their home in Saltcoats, along the Clyde; Maud was only about 16 and Vincent 13. After this, the family can be traced between Saltcoats and Glasgow for a while until they settled in the latter, in a residential part of town some distance from the Paisley Road shop. Mary Kerr inherited the business, which remained in the family until she died on 4 October 1909. Whether she had anything to do with its daily management is unknown, but it certainly flourished, with music advertised in and regularly exported to Australia. We do know that from 1901 until 1919 at the latest, there was a music shop assistant called Jane S. McBride (aged 36 in 1901) and that the shop was under new management, owned by Robert Wallace, from around 1914. It would appear that none of Kerr’s children wanted to take on the family business after Mary’s demise.

While we cannot attribute any publications to Mary Kerr, the general air of authority and insight in the guidance to teachers found in Kerr’s Pianoforte Tutor suggests a piano teacher’s expertise. As such, it is likely that she took more than a polite wifely interest in the Tutor, which was published around 1890. The book was also exported to New Zealand and Australia, and tributes published in the advertisements that appear paratextually inside other Kerr publications and also in newspapers suggest that it was well received.Footnote 10 Reviewers highlighted the popular, recognizable, and accessible tunes in simple keys — Scottish and Irish, American, a couple of ‘plantation’ tunes, and a handful of hymn tunes. The book — surely aimed at piano teachers given the extent of adult-level guidance, and in no way written in a child-friendly style — begins with easy tunes, but proceeds at a pace that today would extend over a whole series of books, with the addition of finger exercises, two-octave scales in all keys, and extensive music theory. James Kerr signed himself ‘author and publisher’, but the passage on pedal technique was evidently written by someone au fait with the piano’s inner workings; it could equally have been by James or Mary, or perhaps was a collaboration.

Maud Speirs Kerr

The Glasgow Athenaeum School of Music had developed from a sociable institution offering classes in a variety of subjects to a music school in the same decade that two of our women pianists opted to take advantage of the benefits it now offered. Principal Allan Macbeth had taken up his post at the Athenaeum in 1890. Kerr’s daughter Maud attended the school, studying for Senior Grade piano under Emile Berger in 1894 and 1895, and winning a scholarship for piano accompaniment in two successive years. She performed chamber music by Henryk Wieniawski and Anton Rubinstein in college concerts in January and March 1897, also attaining the highest level, Fourth Grade piano, that year.

Maud Kerr had good reason to be grateful both for inherited musical talent and for having had the opportunity to develop her expertise at the newly established Athenaeum School, since she subsequently carried on her mother’s musical legacy in her own distinctive way. After a disastrous first marriage, Kerr was able to draw upon these skills to support herself when she joined a couple of touring ‘Highland’ entertainers on a trip to America as a violinist, only divorcing the bigamist Benjamin Disraeli Wigton in 1910, after her mother’s death. Emigration in search of a better life was a common phenomenon in this era, and touring Scottish musical acts found a warm reception among homesick emigrants in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Her return trip to the United States was later followed by a permanent move from Glasgow to Vancouver, where she remarried and played in theatre orchestras for the next twelve years, like her second husband, Harold Taylor. (She may also have played in cinemas; as noted above, one of her brothers certainly did.) Her obituary in the Vancouver Sun seems to suggest that she used her married name professionally: ‘Maude S. Taylor’.Footnote 11

Euphemia Amelia Nightingale Allan

While James S. Kerr was the son of a blacksmith, another new Glasgow music publisher around the same time originated from a very different background. The charmingly named Mozart Allan (actually Ebenezer James Mozart Allan) was born in 1857, the second son of dancing master William Elder Allan, and began his own career in the same métier, as did his elder brother Haydn. One of Allan’s first publications was his father’s pocket dancing manual, and dance music and national songs became staple products for the Mozart Allan imprint. Their premises, first in South Portland Street and then in Carlton Place, would have been more elegant and upmarket in their day than their modern condition suggests.

The Allan brothers’ younger sister Euphemia Amelia Nightingale Allan showed musical talent to the extent of publishing some pieces as a young teenager, under the pseudonym of ‘Arthur de Lulli’. In David Baptie’s late-Victorian lexicon of Scottish musicians, Musical Scotland, more attention was given to the achievements of this youthful, ‘clever violinist, pianiste, and composer’ than to her older career-minded brothers.Footnote 12 Today, Allan is merely known because she composed what is now known as Chopsticks under her ‘de Lulli’ nom de plume. It originated as the Celebrated Chop Waltz, published jointly by Mozart Allan and a London firm, Howard & Co., around 1877 as a solo and as a piano duet. (Instructions in the duet advised the melody player to use the sides of their hands as though they were chopping something.) It was renamed the Chop Sticks Waltz by a Chicago firm, enjoying a long life with this alternative title. Her Celebrated Chop Quadrille appears to have been published solely by Mozart Allan the following year. Another even earlier piece — Wynaad Varsoviana, a dance tune published by the London firm B. Williams — was advertised in the Glasgow Herald and the Alloa Advertiser in 1874, and was later advertised in her father William’s Ballroom Companion. Footnote 13

One can only speculate as to whether Allan used a pseudonym out of modesty, in the hope of achieving greater sales (it was harder for women to achieve sales than for men), as a source of private family amusement, or perhaps a combination of all of these. Pseudonyms were used to disguise both gender and nationality, and were also used by men; in Glasgow, Archibald Milligan also used the name Carlo Volti, an Italian-sounding name devised with the help of his publisher in the hope of attracting a wider audience.Footnote 14 Near-contemporary efforts to persuade Mozart Allan to reveal the truth about de Lulli were met with a polite silence.

Euphemia Allan did not marry, but lived with her brother Mozart and his family. Not until 1901 did the census record her occupation as ‘teacher of the pianoforte’. Both Mozart and Haydn had sons called Mozart; Mozart senior’s son (Mozart junior) was to continue the family firm in Glasgow, living in the family home with his aunt after his own father and mother had died.Footnote 15

More Pseudonyms, and Works in her Own Name

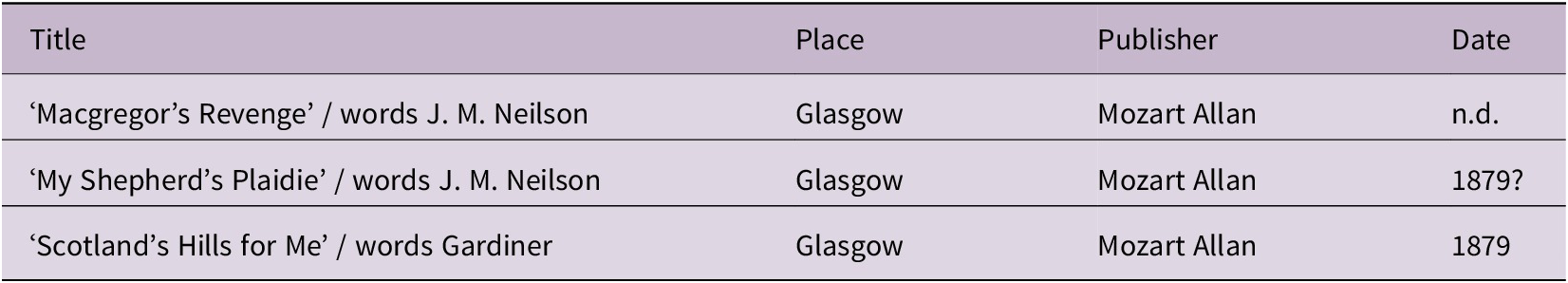

At first glance, this is all that we know of Euphemia Allan, but a more extensive output has been discovered: ‘de Lulli’ published further titles, but Allan also used another pseudonym. Mozart Allan published three Scottish-themed songs by ‘Julius Farinelli’, to whom ‘My Shepherd’s Plaidie’ was attributed in all but two sources: the British Library copy is attributed to Allan herself, and this is confirmed in Franz Pazdirek’s nineteen-volume listing of 1904, The Universal Handbook of Musical Literature: Practical and Complete Guide to All Musical Publications. Footnote 16 Two songs by ‘Farinelli’ were set to poems by J. M. [James Macadam] Neilson, a Glasgow poet published in the 1870s and 80s: ‘My Shepherd’s Plaidie’ and ‘Macgregor’s Revenge’. A third, ‘Scotland’s Hills for Me’, had lyrics by W. B. Gardiner (the publisher William Gardiner, c. 1800–45).Footnote 17 Allan set a fourth Scottish-themed song, ‘The Midges’, under her own name, to lyrics by renowned Scottish poet Robert Tannahill. In London, B. Williams published other early pieces besides Allan’s Wynaad Varsoviana, but once her brother Mozart’s own publishing house was established, she appears to have published her compositions only with the family firm. These were lightweight, comparatively trivial pieces: mainly for piano, and a few songs.

The mysterious and modest Euphemia Allan has more secrets to divulge. Two years after her death, the new owner of Mozart Allan’s music firm, Jack Fletcher, collaborated with Mozart junior to produce a song book, The Glories of Scotland (1950), for tourist visitors to Scotland during the Festival of Britain in 1951, also putting the book into an exhibition of modern Scottish publications at Glasgow’s Mitchell Library, along with a few other choice specimens of Mozart Allan publications. Two of these other examples were Morven, their most popular Scottish song book (1890), and a centenary book of songs by Robert Burns (1896).Footnote 18 In the exhibition catalogue, the Selected Songs of Burns was attributed to Arthur de Lulli — a detail revealed in no other printed source that I have been able to trace. Not only that, but some songs in the Burns book had already appeared in Morven, coincidentally even bearing the same page numbers, albeit not the same print font. This tends to suggest that if Euphemia Allan had some editorial input to the Burns songs, then she was possibly also involved in the compilation of Morven. Tables 1a, b, and c enumerate her output as Arthur de Lulli, Julius Farinelli, and Euphemia Allan respectively.

Table 1a. Euphemia Allan’s output as Arthur de Lulli

| Title | Place | Publisher | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bella Waltz | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Celebrated Chop Quadrille | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1878 |

| Celebrated Chop Waltz: Solo and Duet | London & Glasgow | Howard & Co.; Mozart Allan | 1877 |

| Chop Sticks Waltz | Chicago | National Music Co. | By 1904 |

| Daisy: Quadrille | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Jacobina: Mazurka de salon | Glasgow (60 South Portland St) | Mozart Allan | 1890 |

| Jessie, The Flower o’ Dunblane [piano] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Jolies coeurs [set of waltzes] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1884 |

| Joys of Youth: Waltz | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Last Rose of Summer [piano] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Loudon’s Bonnie Woods and Braes [piano] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Morven [possible involvement?] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1890 |

| Old Towler [piano] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Selected Songs of Burns | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1896 |

| Silver Threads among the Gold [piano] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

| Silvery Waves [piano] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | By 1904 |

Table 1b. Euphemia Allan’s output as Julius Farinelli

| Title | Place | Publisher | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Macgregor’s Revenge’ / words J. M. Neilson | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | n.d. |

| ‘My Shepherd’s Plaidie’ / words J. M. Neilson | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1879? |

| ‘Scotland’s Hills for Me’ / words Gardiner | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1879 |

Table 1c. Euphemia Allan’s output in her own name

| Title | Place | Publisher | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiquarian Quadrille [Antiquarean Quadr.] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1877 |

| Bird of Paradise: Mazurka eleg. | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1904? |

| Dream of the Future: Fant. [piano] | London | B. Williams | 1874 |

| Dream of the Future: Descriptive Fantasia | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1890? |

| First Come, First Served: Polka | London | B. Williams | 1874 |

| Jingo Ring | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | after 1880 |

| The Last Fox of the Season: Galop [piano] | London | B. Williams | 1875 |

| ‘The Midges’ / words Tannahill | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1904? |

| ‘My Shepherd’s Plaidie’ / words J. M. Neilson | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1895? |

| Wynaad Varsoviana | London | B. Williams | 1874 |

| Wynaad Varsoviana | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | 1890 |

| Wynaad Varsoviana [in Ballroom Companion] | Glasgow | Mozart Allan | c. 1928 |

Virtually nothing can be traced of Allan’s daily life. A great-great-niece, traced through the Ancestry website, revealed that her own father had dim memories of ‘old Auntie’, who died when he was just a young boy. The impression was that he found her rather intimidating.Footnote 19 Notwithstanding the paucity of detail about Allan, her death certificate recorded her as a ‘music publisher (retired)’. We can deduce that she was at some point an active member of the family firm, perhaps turning from composition to editing after a youthful burst of enthusiasm, and continuing to teach the piano into middle age.Footnote 20

Catherine MacLernan (Mrs David Logan, Mrs Kate Logan)

In her autobiography, A Life of Song (1929), the Gaelic song arranger and performer Marjory Kennedy-Fraser alluded to some songs in her repertoire that she had sourced in publications by Mrs Logan’s firm in Inverness. This was presumably a reference to the Logan series ‘The Inverness Collection of Popular Gaelic Songs with English Translations’, which had commenced in 1879.Footnote 21

We made a concert tour that summer [1882] in Scotland which included Oban and Inverness by the newly opened railway and the Caledonian Canal. […] Gaelic songs were being issued at the time by Mrs Logan, Inverness, and from her publications I selected ‘Gu ma slan a chi mi’, ‘Fear a bhata’, ‘Mo nighean donn bhoidheach’, &c, and arranging them myself as unaccompanied trios for three equal voices sang them, with Helen and Margaret, from that time forth literally round the world. My father fell in love with them [footnote: ‘He had once himself sung in Gaelic, a translation’] and backed me heartily in my efforts thus to introduce the Gaelic tongue on the concert platform.Footnote 22

Kennedy-Fraser’s memories were accurate to a point, but not entirely. Only five years older than Logan, she may not have yet met her as early as 1882; if she had, she might not have couched her recollections in those terms. When Kennedy-Fraser went to Inverness in 1882, music was not ‘being issued at the time by Mrs Logan’, who was still Miss Catherine MacLernan. It was not her firm, they were not ‘her publications’, and she may not yet even have been performing with the band.

Logan & Co

David Logan established his piano manufacturing firm, Logan & Co., in the 1830s in Aberdeen, his sons James and David opening the Inverness branch around 1879. The firm had commenced publishing circa 1874, with a new edition of Simon Fraser’s Airs and Melodies. This was followed by the ‘Inverness Collections’ series: The Inverness Collection of Highland Pibrochs, The Inverness Collection of Reels, Strathspeys and Country Dances, Arranged for the Piano Forte, etc., as well as the Inverness Collection of Gaelic Songs (1879). Highland dance music, Gaelic songs, and bagpipe music were their major focus, with imprints emanating from Aberdeen and Inverness, while a music circulating library was run from the Elgin branch of the firm around 1885.Footnote 23 Geoff Hore notes that the firm also had a branch in Nairn prior to 1900. David Logan senior died in 1898, but the business continued to expand, opening a branch in Dingwall circa 1900.Footnote 24

Catherine MacLernan’s family lived opposite the Logans’ premises in Church Street. Her father had been a military musician (as we shall see later, Rose Smith had a similar background): Sergeant Major Alexander MacLernan was a Glasgow man, a non-commissioned officer who served in Canada and the West Indies, becoming a bandmaster. His wife, Sarah, was from Leeds. They settled in Inverness in the 1870s, where he was associated with the militias and became drillmaster to the First Company of the Inverness Rifle Volunteers. In the 1881 census, Catherine MacLernan was the only daughter still living at home with her parents, a servant, and three lodgers, and was teaching the piano.

As a piano teacher living opposite a piano and music publishing firm, it was perhaps inevitable that Catherine MacLernan would become friendly with them. By 1886, she was playing the piano in Logan’s band, a commercial ensemble accompanying Highland dances and playing for the Northern Meeting, a sociable club that fostered Highland culture. She married David Logan, the younger brother, at St Andrew’s Cathedral in Inverness in 1889.

Within a few years of David senior’s death, the Logan business in Church Street went bankrupt, caused — as James explained at Edinburgh Sheriff Court in September 1903 — by high interest rates on a loan that the firm had raised. James, David junior, and the firm were jointly and severally declared bankrupt. Valuation rolls are not available for every year, so the surviving records provide only a snapshot rather than a comprehensive record. Nonetheless, the extant Inverness valuation rolls record that at various times, Logan’s owned or leased 55, 57, and 59 Church Street. The only years in which brothers James and David are recorded as owning all three were 1903–04, when they leased no. 57 to three private tenants and William S. Roddie’s music school. In 1904–05, after the bankruptcy, the British Linen Bank owned all three properties, with no. 55 lying empty, tenants in no. 57, and Logan’s shop at no. 59. The original Logan & Co. now began trading under a new name, Logan & Co. (Inverness) Ltd, from The Highland Music Warerooms at 59 Church Street, with shares being held by seven Inverness businessmen. James was the managing director, but David was no part of it. The firm later took over the ‘stock and goodwill’ of J. Marr Wood around February 1915, becoming Logan & J. Marr Wood Ltd at The Royal Music Saloons, briefly at 23 Church Street before reverting to no. 59. Circa 1923, the firm merged with a larger firm, Paterson’s, which had branches in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and various other Scottish towns at different points in time.Footnote 25

Kate Logan’s Pianoforte and Music Saloon

Were there family negotiations leading to Kate Logan opening another music shop in her own name? Hore suggests that under the terms of the bankruptcy and the subsequent establishment of the new firm, it is possible that James and David could no longer be partners.Footnote 26 Nonetheless, on 2 March 1904, barely six months after the bankruptcy, the Northern Chronicle and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland advertised that Mrs David Logan had opened a ‘pianoforte and music saloon’ at 10 Drummond Street.Footnote 27 From these premises, she sold pianos, coordinated piano tuners’ visits, and presumably ran the band. She moved to new premises at 10 Lombard Street in May 1905, and again to Queensgate Arcade after her husband’s death in 1926.

As an aside, we can note Matthew Chambers’s observation that it was unusual for women to run bookshops until the mid-1910s in either Britain or the United States, unless they had inherited them.Footnote 28 (Indeed, as we observed, Kerr inherited her husband’s music firm in Glasgow in 1893.) However, the situation with music was rather different. As Clare Gleeson has noted, women’s involvement in music retail was not uncommon, for music was such a popular pursuit among women.Footnote 29 The fact that Kate Logan was running a music shop in Inverness a full decade earlier than Chambers observed with bookshops is perhaps only remarkable inasmuch as a small town in the Highlands might have been expected to be rather conservative. The fact that she was running a band as well certainly suggests that she was a capable and determined entrepreneur. Her business throve for three decades.

Even before the brothers’ bankruptcy, the band was beginning to become known as Kate Logan’s own band within a couple of years of her father-in-law’s death in 1898. Advertised as ‘Messrs. Logan’s band’ in 1899, we find ‘Mrs Logan’s band’ noted in a newspaper report at the end of 1900.Footnote 30 The old-style name, or just ‘Logan’s band’, was still reported in 1902, with Mrs David Logan, or just ‘Mrs Logan’, presiding at the piano. However, by 1904, references to Mrs [David] Logan’s band, or occasionally Mrs David Logan’s reel party, indicate that she was directing from the piano. She must sometimes have been ‘out of office’, taking her band around the country to gigs: they are documented as having performed in London, and twice went there to make recordings, for Columbia in 1923 and Beltona in 1925 — Scottish music was a very popular genre for recorded music in this era.Footnote 31 Perhaps David, ten years her senior, remained in Inverness to look after the shop. Her obituary in the Aberdeen Press and Journal clearly states that it was her business: ‘Her husband, who died ten years ago, was associated with her for a long time in the conduct of her musical business in Church Street, Inverness.’Footnote 32

Kate Logan, the Dance Pianist

Providing musicians for events was a lucrative sideline for music publishers.Footnote 33 In Edinburgh, Paterson’s took bookings for musicians, but Logan’s own band was certainly in demand. Reports of the band’s appearances often specifically mention ‘Mrs [David] Logan’, who was clearly making a name for herself, and was noted as being the most in-demand dance pianist of her day. Angus Fairrie’s book about the Northern Meeting alludes to her prowess as a dance band pianist, a helpful, capable, and much-loved fixture of their engagements. Fairrie cites an 1893 letter concerning a dance engagement, which informs us that Logan’s band consisted at that time of violins, flute, oboe, clarinet, cornets, trombone, double bass, drum, and grand piano.Footnote 34 A later recollection by one of Fairrie’s informants alludes only to her ‘fiddlers’, and there is no trace of wind or brass instruments on the Caledonian Orchestra’s 78 rpm record, Columbia 3319.Footnote 35 There is no indication as to whether any of these iterations were solely made up of women performers.Footnote 36

Logan preferred reels and strathspeys, and was a little resistant to the newer jazz-inspired dances.Footnote 37 At one point, a board was put up reading, ‘Charleston not allowed’. In her later years, the Northern Meeting would employ a jazz band to share the gig, playing the modern dances that she would not. Fairrie was told by older informants that she seems to have been something of an unstoppable force; younger jazz musicians found her unlike anyone that they had encountered in gigs before. Fairrie notes that in the early 1930s, some of the band leaders seemed unsure how to deal with her; indeed, someone had to ‘pacify some of the band leaders who had never been thwarted by anyone quite like Mrs Logan at her piano’.Footnote 38 One further recollection adds a humorous note: Captain Patrick Munro of Foulis told Fairrie that a teacup would rattle on the edge of Logan’s grand piano while she played, but she never seemed to take milk or sugar in her tea — closer inspection revealed her cup to contain neat whisky.Footnote 39

A writer for the Sphere newspaper, intended for readers across the British Empire, made exuberant (and breathless) mention of Mrs Logan’s prowess as a pianist at Inverness’s annual Ghillies’ Ball in 1927 and 1928, when she was already getting on in years. September 1927 saw a feature about Inverness and contemporary Highland prosperity which also highlighted Mrs Logan’s role in accompanying dances for the aforementioned ball. She had been widowed in 1926, when she was 64, but her accustomed energy was undiminished:

Do you know those Highland orchestras, of which Mrs. Logan of Inverness is the reigning Queen, patentee, and acknowledged magician? You talk of dance music, your saxophones […] You have no faint notion of what dance music, rhythm, time, abandon, thrill, intoxication, mean till you have heard Mrs. Logan’s band changing to quick time, and fifty kilted Highlanders responding to her magic with toe and heel, tongue and heart. Crash! Bang! Hoch aye! The floor leaps in the air, the walls tremble, sweat pours down, the dust rises in choking fumes. […] And then come the country dances, not necessarily more gentle […] The ‘Circassian Circle’. You should come to it with a doctor’s certificate. It’s no cure for cardiac trouble. You will […] cover the equal of six miles over the plough. Or, as a breather, the dignified ‘Triumph’, the ‘Flowers of Edinburgh’, the ‘Highland Schottische’ […] By three o’clock in the morning there is no sensible slackening of energy. The seventh reel is half over.Footnote 40

A year later, the same journalist appears to have gone back for more, gushing that no ball was a success if Mrs Logan wasn’t there:

Inverness’s Leading Lady.

[…] Who is at this moment the most popular, the most sought after, the most difficult to secure of all these ladies who throng grey old Inverness? […] She is the first on the invitation list of every dance-giver. The dance is prejudged an utter failure if she does not accept. In the ballroom she is from start to finish the centre of attraction; without her the reels fall flat, her spirit inspires the entire company which revolves round her like gay moths round a candle; she is the Robin Adair that makes the assembly shine, the spirit of joy, movement, swing, rhythm; she is in a word the most sought-after woman in the Highlands just now. Her name is Mrs. Logan. When you have heard her play a reel you will […] resign from all your night clubs.Footnote 41

More serious acknowledgement of Logan’s expertise is evidenced by the fact that when Miss Jean Milligan founded the Scottish Country Dance Society (SCDS) with J. Michael Diack and other influential people in November 1923, early committee minutes record that Logan was on the publications subcommittee for the Highlands, and on the music committee, along with Kennedy Fraser, Diack, and others. While this was undoubtedly a tribute to Logan’s expertise, there are no further mentions of her in the main society minutes, except for an apology for absence. In all probability, she was too busy with existing commitments, with David by now quite elderly. She may not have been much involved with the growth of the new society.

Kate Logan’s Role in the Family Business

When Kennedy-Fraser was writing her memoirs (published in 1929), Logan was still active as a musician and in her Queensgate Arcade shop. Kennedy-Fraser had been on the same SCDS committee (however briefly Logan was involved with it), so she must have been aware of the latter’s band and retail activities. She must have associated Kate and David with the Logan brand, whether or not she realized that Kate Logan was now running her own business, distinct from Logan & Co. (Inverness).

Kate Logan’s obituaries in both the Aberdeen Press and Journal and the Inverness Courier (based on the same press release) again appear to conflate David’s and Kate’s activities with the original Logan & Co. and their subsequent business in the name of Mrs David Logan.Footnote 42 If nothing else, we can deduce that Mr and Mrs Logan were strongly associated with the original family firm, before Kate later opened her own premises. (She might even, as a younger woman, have been involved with playing over new music in the original Logan shop, but there is no documentation to prove or disprove it.)

After her husband’s death in July 1926, Kate Logan leased a unit in Inverness’s Queensgate Arcade, continuing there until a year or so before her death in 1936.Footnote 43 Even a fire on the premises in 1931 was insufficient to make her consider retirement. She also played for dances until a couple of years before her death; indeed, in August 1933, she and her band played four dances in a concert of Scottish song and dance for a regional radio broadcast from Aberdeen.Footnote 44 Her final Northern Meeting was in 1934, when she was given a handsome cheque. In return, her only publication, Strathspeys and Reels for the Pianoforte (1936), was dedicated ‘by kind permission to The Convenor, Earl Cawdor and The Members of the Northern Meeting’.Footnote 45 If Logan only ever published one slender music score of her own, this suggests that publishing was not a key activity for her, and there is no evidence to suggest that she had any active involvement with the publishing side of the original Logan firm. Publications in the last couple of decades of the nineteenth century are never attributed to her, although of course, this need not rule her out from other behind-the-scenes activity.

‘Strathspeys and Reels for the Pianoforte’ (1936)

The abovementioned tune book was advertised in the Inverness Courier on 14 April 1936, just weeks before Kate Logan’s death in a nursing home. Mozart Allan published the book, which contained only five pages of music. (Paterson’s had by this time taken on the Logan & J. Marr Wood list.) She acknowledged the assistance of a collaborator, J. A. Mallison, who had been one of two official accompanists in the Inverness Music Festival in 1932 and was to be the adjudicator for the Badenoch and Strathspey annual Provincial Mòd in 1936–37 (a Mòd is a Scottish Gaelic cultural festival; this particular event was one of the local ones, as distinct from the Royal National Mòd). The collection contains arrangements for piano of three strathspeys and seven reels, and the accompaniments are very elementary. The reel accompaniments consist mainly of bass octaves on the first and third crotchets of the bar, or occasionally on every crotchet; the strathspeys generally have a bass note on every beat. Full chords may appear at cadences, or not at all. A few down-bow marks are indicated, and equally sparse dynamics. Only one tune, the ‘Reel o’ Tulloch’, is also represented in her recorded output. Table 2 provides a list of Kate Logan’s recordings.

Table 2. Kate Logan’s recordings

| Title | Label | Date | Performers |

|---|---|---|---|

| A side: Lady Mary Ramsay / Nathaniel Gow [and] Reel o’ Tulloch / John MacGregor: foursome reel to follow eightsome; [and] B side: Lady Madeline Sinclair / Niel Gow; The Wife She Brewed It / trad; The Keel Row / trad (Highland Schottische) | Columbia 3320 | Recorded London, Monday 23 June 1923 | Mrs Kate Logan and the Caledonian Orchestra |

| A side: Rachael Rae (Eightsome Reel. First Part); [and] B side: Rachael Rae (Eightsome Reel. Second Part) | Columbia 944 | Recorded London, Monday 23 June 1923 | Mrs Kate Logan and the Caledonian Orchestra |

| A side: Strip the Willow (tune The Irish Washerwoman) / trad [and] B side: Petronella: Country Dance / trad | Columbia 3319 | Recorded London, Monday 23 June 1923 | Mrs Kate Logan and the Caledonian Orchestra |

| A side: Traditional Scottish Dances - part 3 [and] B side: Traditional Scottish Dances - part 4 | Columbia 954 | Recorded London, Monday 23 June 1923 | Mrs Kate Logan and the Caledonian Orchestra |

| A side: Mrs Logan’s Famous Scottish Waltz, part 1 [and] B side: Mrs Logan’s Famous Scottish Waltz, part 2: piano solos by Mrs David Logan | Beltona 799 | Recorded London, May 1925 | Mrs Kate Logan piano solo |

Rose Buchanan Smith (Mrs Iden Rigden)

The fourth book of Kerr’s Merry Melodies, possibly dating as late as 1911–14, includes three tunes attributed to a woman, Rose Smith: ‘Cap and Bells’: Polka, ‘My Polly’: Waltz, and ‘Sweet Dreams’: Valse. Footnote 46 Who was this woman with a very English-sounding name? Indeed, might she have composed anything more than this handful of dance tunes? If the fourth collection was as late as is suspected, then it was published after Mary Kerr’s demise, and possibly by the new owner, Robert Wallace.

Again, piecing together the jigsaw reveals a woman of some talent and ambition. The youngest daughter of an English trumpet major who retired to Scotland, Rose Smith was born in Lanark. Her father, James Smith, died in 1877, his funeral taking place in Lanark with military honours. He had followed his own father into military service with the 11th Hussars, spending eighteen years with the auxiliary forces in the town after retirement, teaching instrumental bands and vocal groups, and latterly serving as a drill inspector to the Lanarkshire Yeomanry Cavalry.

Besides raising six children, Rose’s mother, Mary Ann Smith (c. 1828–c. 1900), was known in Lanark as a published poet (Mrs M. A. Smith), producing two book collections and publishing poems in the Hamilton Advertiser and the Lanarkshire Upper Ward Examiner. One particular poem, ‘The Great Big Shah’, in her Poems and Songs (1873, repr. 1877), is an early instance of her interest in women’s rights, alluding to the minimal rights and restricted life of the Shah’s harem:

He that makes the laws that keep his women in subjection,

Denies nutrition to their minds […]

Think [sic] women in particular are some inferior species

Of the human race in general, only born for man’s caprices.Footnote 47

M. A. Smith moved the family to Glasgow within four years of James’s death. (Her eldest daughter, Mary Ann Trott Smith, appears on the 1881 census as a music teacher, but had moved away by the following census.) She continued writing poetry; there was a poetic exchange in the Glasgow Weekly Herald in 1884 in which she and Marion Bernstein wrote poems about franchise demonstrations and women’s rights. Bernstein’s poems appear in Cohen, Fertig, and Fleming’s edition of her poetry, A Song of Glasgow Town, where the editors’ commentary says of M. A. Smith that:

A vein of gentle humour runs through most of her verses; but a few pieces, especially those on temperance concerns and gender matters, are scornful in tone. In her ‘Reply’ to Bernstein, she expresses anger at those who ‘say a woman’s right sphere is her home’ and anticipates a subsequent stage of political discourse.Footnote 48

By contrast, Honor Rieley, on The People’s Voice website, observed that Smith’s response is somewhat ambiguous and possibly sarcastic, compared to the forthright observations of Bernstein.Footnote 49 It is quite possible that this Smith might be the same M. A. Smith who was the lyricist of a ‘humorous musical sketch’ composed by Constance M. Yorke and published by Bayley & Ferguson in the 1890s: Mr and Mrs Dobbs at Home. Again on the theme of women’s rights and the franchise, the sketch similarly takes a somewhat ambiguous and ambivalent line as to whether women should have a life beyond the home.Footnote 50 (A ‘comic duet’ by this title had twice been performed some years earlier in Lanark in 1874 by ‘Madame Smith’s two sons’. They were accompanied by a ‘Miss Smith’ at the piano.Footnote 51 Clearly, this cannot have been Rose Smith, who would have been too young, and it is impossible to know if this was Constance Yorke’s music or an earlier setting.)

In this duologue, both husband and wife are extreme caricatures; a preferable middle ground of equality between the sexes is only inferred by its absence. Mr Dobbs appears ‘in shirt sleeves and kitchen apron, with broom in one hand, duster in the other’; he is responsible for housework and childcare, and is completely dominated by Mrs Dobbs. Acquiescent for the greater part of the sketch, he objects to one of his wife’s friends (‘She’d have you in that “Women’s Rights” affair/And I’m bound to differ from her there’), and the final duet concludes with Mr Dobbs singing ‘Women can’t rule just as well as the men’, against Mrs Dobbs’s assertion that they can.

Of course, poems are open to different interpretations, and while Cohen et al allude to Smith’s ‘anger’, Rieley suggests an ambiguous display of sarcasm. The musical sketch pokes fun at a hypothetical situation in connection with women’s suffrage. Nonetheless, one can safely assert that these, along with the views asserted in ‘The Great Big Shah’, demonstrate M. A. Smith’s interest and willingness to engage in the issues, and it is therefore hard to imagine that she would not have engaged in conversations about women’s rights with her daughters at home. I shall demonstrate that such a home background is entirely consistent with the way Rose Smith navigated her own career.

By the time Rose was a young woman, she was living with her mother and another sister in London Street, in the east end of Glasgow. There, following in her sister Mary Ann’s steps, she advertised piano lessons from 1886 onwards. By 1889 she was advertising theory tuition and her services as an accompanist as well. Harmony and counterpoint lessons were also offered in 1891, with organ and singing lessons newly advertised in 1892. I have traced her as the organist at St Andrew’s Episcopal Church in the early 1890s; as we shall see, newspaper reports suggest that she continued to be involved with the church for some time after this. Meanwhile, her part-song ‘Widow Malone’ was published by Paterson’s around 1892; the Kirkintilloch Herald notes its performance in Lenzie (just outside Glasgow) in December 1893.

Rose Smith began studying at the Athenaeum in 1892, two years after the appointment of Macbeth as principal and two years before Maud Kerr attended there.Footnote 52 She achieved first-class marks in Advanced Harmony under Mr Ferrier and in piano under Emile Berger, a couple of years before Kerr was to study under the same teacher.Footnote 53 In 1893, Smith was not listed as a student in the School of Music class lists, but was awarded a £5 composition scholarship under the tuition of Otto Schweizer. A newspaper review noted one of her songs, ‘The Beggars’, performed in May 1893.Footnote 54 By August that year, she had joined the Athenaeum staff, giving junior piano lessons, but only seems to have taught there for two years.

By 1894, if not before, she had published more music, this time with Kerr’s. These three lightweight pieces, advertised under ‘popular music for small orchestra’ in the ‘Dance Music for Orchestra’ series, were the aforementioned ‘Cap and Bells’: Polka and ‘Sweet Dreams’: Waltz, and another waltz, Les Militaires. The latter is unexpectedly noteworthy. As Margaret Myers describes, women’s orchestras were a popular novelty act in the late nineteenth century; there were dozens of them, offering women a hardworking and varied career and the chance to travel, although sometimes they were subjected to disparaging and misogynistic comments.Footnote 55 (Ehrlich observed that despite their professionalism, they were not very well paid.)Footnote 56 Les Militaires was a ladies’ string orchestra led by Mrs Hunt, ‘grand concerts’ being advertised in Liverpool, London, Dublin, Manchester, Preston, ‘&c’, in 1889 alone.Footnote 57 Fuller also notes this orchestra’s fame and their striking costumes.Footnote 58 The ensemble gave a number of performances in Scotland from 1890 to 1896, visiting Glasgow in February 1891 for the East End Industrial Exhibition, as reported in the Glasgow Herald. Footnote 59 Smith’s dance tune may thus have been inspired by (or written for) a women’s orchestra that she could have heard playing in Bellgrove, only a mile or so from her home.

Smith married the customs officer Iden Ernest Rigden in 1898; they had three children, two sons and a daughter.Footnote 60 But she continued her musical activities: in 1901, she accompanied a performance in the South Side Assembly Rooms, Crown Street, by the operetta class that she had been teaching. Her husband was one of the principals in this performance. Notably, the newspaper review describes her as ‘Miss Rose Smith (Mrs Rigden)’; her professional name came first. Since two clergymen from St Andrew’s Episcopal Church were named in the review, the class may have been run as a church social or educational activity. Smith also continued her piano teaching practice, as evidenced by the 1911 census, when the couple had not long moved to Rutherglen (just outside Glasgow). She was involved in the West of Scotland branch of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, with a surviving photograph recording her attendance at the 1903 conference in Glasgow — despite having her second baby that year — while in October 1910 she was elected to the Sectional Council of the ISM West of Scotland section (possibly just for one year), also performing from time to time and continuing to compose.Footnote 61

Not all of Rose Smith’s music is still extant; some titles are only traceable through secondary sources. Table 3 enumerates her output, which fell into three main categories: piano music for pianists of modest ability, dance music for piano, and songs. As noted earlier, Kerr’s published some of her early work, and she does not seem to have forsaken them, despite later also publishing with Mozart Allan. A couple of her tunes were subsequently arranged by other people under Kerr’s imprint. Additionally, she had a song published by John Blockley in London. (If there were more, then they are no longer traceable.) Inheriting her mother’s aptitude as a wordsmith, Smith penned her own lyrics for ‘Benorie’ (published by Blockley) and her self-published songs ‘For You’, ‘Now You’re Afar’, and ‘A Song of Joy’.

Table 3. Rose Smith’s Output

| Title | Publisher | Date |

|---|---|---|

| The Beggars | Unpublished? Composed whilst student at Athenaeum. | May 1893 |

| ‘Benorie’ [song; words and music] | John Blockley 3 Argyll St | by 1903 |

| ‘Cap and Bells’: Polka. Series: Popular Music for Small Orchestra. Dance music. Advert on back of Volti, Drawing Room Orchestra series no.12 [Il Trovatore] | Kerr | by 1894 |

| ‘Cap and Bells’: Polka | Kerr | c. 1911–14 |

| The Cap and Bells Polka / arranged for violin by Alfred C. Wood | Kerr | c. 1920 |

| Floating [two versions for ‘septett’ or piano] | Kerr | by 1894 |

| ‘For you’ [song; words and music] Dedicated to Evelyn King, a Royal Academy of Music graduate who was performing in a music troupe at Milngavie near Glasgow in 1921–22, and later in London |

Idene Music | 1918 |

| Forget-Me-Not | Mozart Allan | 1900? |

| Happy-Go-Lucky | Mozart Allan | 1900 |

| ‘Heart of Mine’ / words Bert Davis [song] | Idene Music (band parts in C & D also available) | by 1918 |

| Inez: Spanish Dance [piano mazurka] | Kerr | by 1894 |

| ‘Kitty McLean’ [song] | by 1894 | |

| Lily of the Valley: Waltz [piano] | Mozart Allan | 1900 |

| ‘Long Ago’, from Idene: Musical Play | Idene Music | 1920 |

| Les Militaires: Waltz. Series: Popular Music for Small Orchestra. Dance music. Advert on back of Volti, Drawing Room Orchestra series no.12. Additionally, two versions for ‘septett’ or piano advertised on the back of a piano piece by Henri Laski | Kerr | by 1894 |

| Les Militaires: Valse / arr. Alfred C Wood | Kerr | c. 1920 |

| ‘Molly Mavourneen’ [song] | Self-published | by 1917 |

| ‘My Polly’ [song]. Henri Laski’s waltz on ‘Rose Smith’s popular song’ is included in Kerr’s Collection of Latest Dance Music [Kerr’s Popular Violin Books series no. 8] | [n.d.] | |

| ‘My Polly’: Waltz | Kerr | c. 1911–14 |

| ‘My Polly’: Waltz on Rose Smith’s Popular Song / composed Henri Laski, arr. Alfred C. Wood | Kerr | c. 1920 |

| ‘Now You’re Afar’ [song; words and music] from Idene: Musical Play | Idene Music | 1920 |

| ‘Return’ [song; words and music] | Self-published by R. Rigden (no mention of Idene Music) | 1917 |

| Simplicity | Mozart Allan | 1900 |

| ‘Smile’ / words Harold Hazelwood, from Idene: Musical Play | Idene Music | 1920 |

| ‘A Song of Joy’ [song; words and music] | Idene Music | 1918 |

| Spring Blossoms [piano] | Mozart Allan | 1900 |

| Sweet Briar [piano] | Mozart Allan | by 1900 |

| ‘Sweet Dreams’: Valse | Kerr | c. 1911–14 |

| ‘Sweet Dreams’: Valse; arranged for violin by Alfred C. Wood | Kerr | c. 1920 |

| ‘Sweet Dreams’: Waltz [septett or piano]. Series: Popular Music for Small Orchestra. Dance music. Advert on back of Volti, Drawing Room Orchestra series no.12. Additionally, two versions for ‘septett’ or piano advertised on the back of a piano piece by Henri Laski | Kerr | by 1894 |

| Under the Trees | Mozart Allan | 1900 |

| The Water Sprite [piano] | by 1894 | |

| ‘Widow Malone’ [four-part song]. Series: Paterson’s Part Music no. 21 | Paterson | c. 1890–92 |

| ‘Large repertoire of songs, duets and song scenas, especially written for …’ Advert in The Stage, April 1921, hints at further material, possibly unpublished. Smith appears to be acting as some kind of agent for them (and her own work) | 1921 |

Latterly, she self-published her songs under Idene Music (based on her husband’s first name) from her home in Rutherglen. There is no documented reason for her self-publishing; while getting music performed or published was historically more difficult for women, single songs were perhaps not quite as difficult to place as other formats, and Smith’s songs are stylish, competent, and tuneful.Footnote 62 There was good money to be made by selling single songs. Although Smith sold and advertised ‘professional copies’ (i.e. review copies) at six or seven pence, she subsequently sold them at two shillings, the same price that Boosey was charging for their hugely popular ballad songs.Footnote 63 Self-publishing entailed Smith bearing the full costs of production and also assuming responsibility for marketing, which is evidenced by several advertisements in the Stage. Since she was known both to local music publishers and to Blockley, one can only speculate as to whether they had rejected these songs, if she had approached other publishers unsuccessfully, or if she made a deliberate choice not to approach the publishers she had used before.

This summary barely does her justice, for some of her songs were written for variety artistes, performed in England and popularized by a few individuals named in a series of advertisements in the Stage. The war, and military connections, were not far away; the two named baritone singers had previously been in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers; one was invalided out early on during the Great War, while the other was a Mons hero. Smith’s oldest son, Iden Ernest Norman Rigden, died in active service on 23 July 1918, aged 19. Probably prompted by this tragedy, she wrote a musical play containing three songs, which was performed at the Glasgow Athenaeum in 1920.Footnote 64 It was entitled just Idene. Two songs appear to address a soldier away from home, and strongly suggest a connection with Iden junior. One, ‘Smile’, with words by Harold Hazelwood, begins:

When the road is hard to travel, and the hills are long and steep,

And your weary steps are lagging, still the pace you try to keep!

Oh! Smile, just the same,

Tho’ all is dark about you.

As mentioned, Smith wrote the lyrics of ‘Now you’re afar’ herself: ‘I wonder if your thoughts to me like mine to you have flown?/I think of you in danger and I hope and pray alone.’ The chorus, repeated after each of the two verses, continues:

Now you’re afar, never a star illumines the night of gloom;

Laughter has fled, pleasure is dead, roses no longer bloom.

When you were near, life held no fear,

Love reigned in our hearts supreme.

Sunshiny hours! Music and flowers! All was a happy dream.Footnote 65

Smith must have written more than still survives, for I have traced what may have been her final advertisement in the Stage, from 14 April 1921, in which she promotes the services of two people for whom she had written repertoire: soprano Phyllis Sinclair and Welsh baritone Bert Rowland. The advert boasts of a ‘large repertoire of songs, duets and song scenas, especially written’ for them by Smith. Smith’s husband died in 1923; in her early fifties, after the loss of both Iden and Ernest, she appears to have published nothing more after this time. She lived until 1942, outliving her second son, Everden, by eleven years.

Smith’s output, although slight compared to more prolific, recognized composers, nonetheless defines her as a competent composer of music for both amateur pianists and variety theatre acts. In an era when talented musicians often left Scotland to train in London or abroad, she remained; she studied harmony, composition, piano, and organ both at Glasgow’s new music school and with professionals not in that institution, and made use of her talents for several decades.

Until well into the twentieth century, it was perfectly normal for a woman to be known by her husband’s full name: Kate Logan was referred to as Mrs David Logan, or latterly just Mrs Logan. Even her own Strathspeys and Reels were published as by ‘Mrs David Logan’, as were her recordings. Rose Smith and her mother seem to have been a little more modern: her mother published using her own initials with her husband’s surname, as Mrs M. A. Smith, or just M. A. Smith. Rose Smith gave her first name rather than initials, and her authorship was always as ‘Rose Smith’, although her self-published compositions were initially published by ‘R. Rigden’ until she adopted ‘Idene Music Publishing’. Newspaper columnists made their own choices, such as ‘Mrs Rose Smith Rigden’, while the ISM West of Scotland branch annotated the only known surviving photograph (see Figure 1) simply as ‘Mrs Rigden’.

Figure 1. Mrs Rigden, ISM Glasgow Conference, 1903 (by kind permission of the Independent Society of Musicians).

Conclusion

This article has explored the achievements of five women connected with Scottish music publishers from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Occupying a position in the blurred overlap between upper working and lower middle class, Kerr, Allan, Smith, and Logan all started out as piano teachers. The latter three left a durable legacy in the shape of publications and/or recordings, while Kerr’s involvement in the family publishing firm remains unclear — for a start, did she or did she not help compile Kerr’s Pianoforte Tutor? Meanwhile, Kerr’s daughter Maud made her own transatlantic mark on the music scene as Maud Taylor, leaving little permanent evidence, apart from a few American newspaper reviews and her obituary in the Vancouver Sun. (Taylor is the only one of the five not on record as having taught the piano.) We may never know whether or not she played for silent movies after emigrating, but research for the present article highlighted the need for more work to explore women silent film musicians in Scotland; there appears to be no published scholarship comparable to Condon’s work on silent film music accompaniment in the Irish context, or Kendra Preston Leonard’s on the substantial input of women film accompanists in America during that era.Footnote 66

A sample of five women is representative neither of an era nor even of the hundreds of Scottish women piano teachers working during that time. Their significance is predominantly that they were connected with some of the key Scottish music publishers of their day, and their careers came to light today because of these connections. Notwithstanding these caveats, and the relatively lightweight nature of their music — whether compositions, edited compilations, or recordings — taken together, these women absolutely bear out the findings of Condon, Ehrlich, Gleeson, Leonard, and Myers. Music offered late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century women an attractive professional career, which they could take in whichever direction appealed to or suited them. Thus Allan was undeniably active in composing light music (although much was discreetly one step removed from her own name by the use of pseudonyms), besides having a largely undefined role in the family music publishing firm, and some kind of piano-teaching practice. Smith combined being a wife and mother with teaching the piano and leading an opera class (probably at her church), and also writing and self-publishing competent and appealing songs for variety theatre singers. Both Allan and Smith were mentioned in Baptie’s Musical Scotland. (Indeed, Mozart and Haydn Allan are detailed at the end of Euphemia Allan’s listing, rather than Mozart Allan’s firm having a listing of its own.) Logan became arguably the most famous of the five, as one of the grandes dames of Scottish country dance accompaniment, while also running a successful music shop; Maud Kerr started a new life overseas, playing the piano in Vancouver theatres for a decade, as did her husband, Harold Taylor.

None of the five achieved anything remotely like the fame of Marjory Kennedy-Fraser, with her Gaelic song interpretations largely published by Boosey, along with a few by Paterson’s. Kennedy-Fraser knew Logan by repute, and probably later also by association to a limited extent, while Kennedy-Fraser and Smith were both in the Incorporated Society of Musicians, although they would probably have primarily moved in the Edinburgh and West of Scotland branches respectively.Footnote 67

I have noted the different approaches each took towards ‘owning’ their compositions, taking the possibility of Mary Kerr’s hidden hand in Kerr’s Pianoforte Tutor as the furthest extreme of anonymity, then Allan’s two pseudonyms alongside the use of her own name, with Logan content to be known by her husband’s name alongside her own reputation and Smith retaining her birth name professionally — one step further than her own mother, Mary Ann Smith, who used her own initials rather than her husband’s forename against her published poetry.

The influence of the Glasgow Athenaeum should also not go unnoticed. It was not a music school in Kerr’s day, but her daughter Maud benefited not only from music tuition there, but also by gaining two scholarships in piano accompaniment. Before Maud Kerr’s attendance, Smith had also received instruction from the same piano professor, besides winning a scholarship in composition and teaching there herself.

Logan, on the other hand, was arguably more isolated in Inverness. Lessons in Glasgow (or for that matter, anywhere else in the Lowlands or further south) would probably have been impossible. There is no evidence to inform us how and where she acquired her musical skills; perhaps her father, a professional military musician himself, had also been her teacher.Footnote 68 Joining Logan’s band must have seemed an entirely appropriate way for her to exploit her evident musical talents, initially just in the Highlands but in later life further afield as well. With her progression from band pianist to band leader, the evidence points to a woman with talent, personality, drive, and leadership, willing to travel long distances and to embrace new technologies.

All five women were evidently an asset to their family’s professional standing and potentially role models for other women seeking to pursue a rewarding musical career. They were not alone in these endeavours; one could immediately cite plenty of other professional women musicians. They are nonetheless significant in enabling us to form a more rounded picture of musical opportunities available to Scotswomen in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.