1 Introduction

Lasers in the 3 μm wavelength region cover the absorption lines of many molecules (H2O, NH4, CO, etc.), making them important for applications in gas sensing, molecular spectroscopy, medical surgery and related fields[ Reference Serebryakov, Boiko, Petrishchev and Yan1– Reference Du, Zhang, Li, Gao and Tong3]. A simple and efficient approach to generating laser emission near 3 μm is to use erbium (Er) lasers pumped by 976 nm laser diodes (LDs). To further enhance the laser performance in the 3 μm region, extensive research has been conducted on various Er-doped media, including both fiber and crystalline materials.

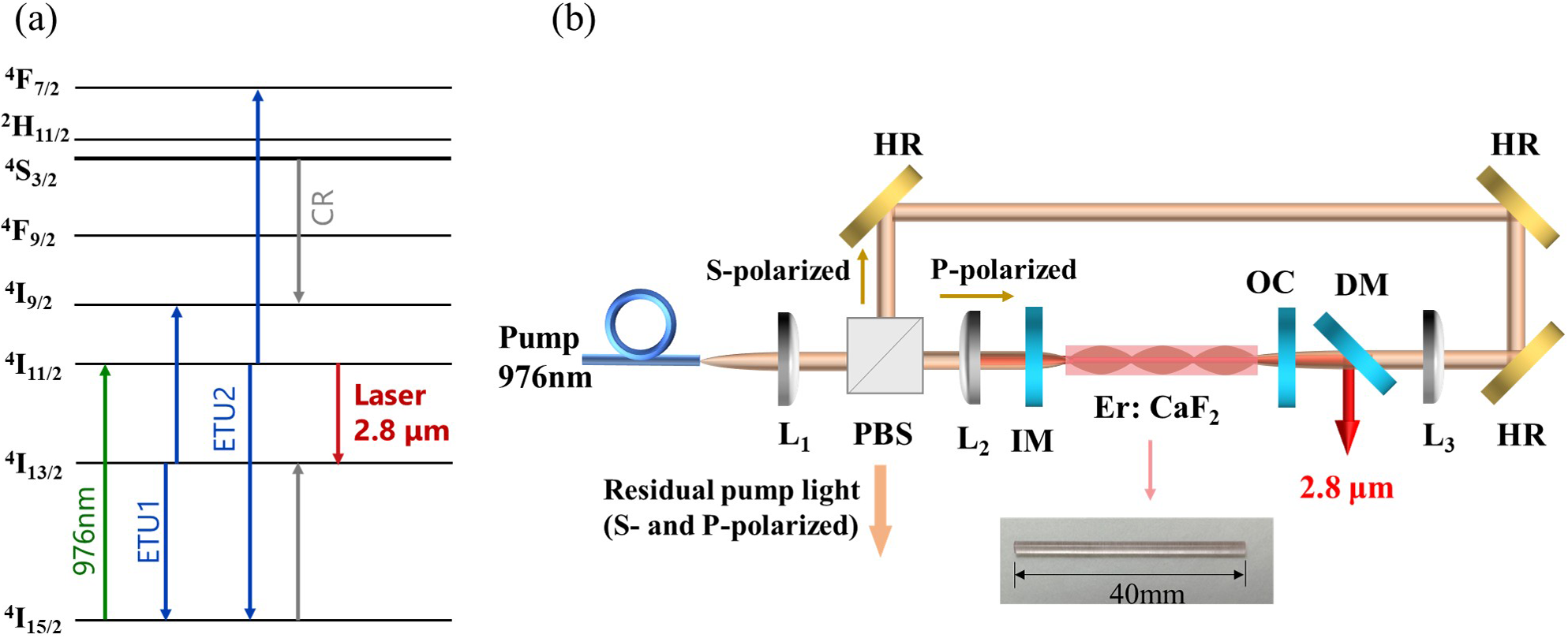

Er-doped fluoride fiber lasers have excellent beam quality and high thermal dissipation capability. However, the end faces of these fibers are prone to be damaged because of the hydroxyl (-OH) contamination from the air, which limits their long-term stability and applicability. In comparison, Er-doped laser crystals have higher thermal conductivity and larger end faces, making them suitable for high-power lasers. Since the lifetime of the lower laser level (4I13/2) is much longer than that of the upper laser level (4I11/2) in Er-doped media, heavy Er-ion doping is often employed to enhance the energy transfer upconversion (ETU1) process (4I13/2 + 4I13/2 → 4I15/2 + 4I9/2, as shown in Figure 1(a)), thereby avoiding lasing self-termination effect and maintaining sufficient population inversion. This approach has been widely used in erbium-doped yttrium scandium gallium garnet (Er:YSGG), erbium-doped lutetium yttrium scandium gallium garnet (Er:LuYSGG) and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG)[ Reference Zhang, Sun, Luo, Quan, Zhang, Qiao, Dong, Chen, Wang, Li and Cheng4- Reference Chen, Fincher, Rose, Vernon and Fields7]. However, heavy doping in crystals increases heat power density, leading to more severe thermal effects. While side-pumping can alleviate this effect and support high-power laser operation, the slope efficiency is relatively low[ Reference Zhang, Sun, Luo, Quan, Zhang, Qiao, Dong, Chen, Wang, Li and Cheng4- Reference Arbabzadah, Chard, Amrania, Phillips and Damzen6]. Low-phonon-energy hosts reduce the probability of non-radiative (NR) transitions caused by multi-phonon relaxation, leading to superior laser performance. Among them, sesquioxide and fluoride crystals are two types of promising gain materials[ Reference Kränkel8]. Lasers based on sesquioxide hosts, such as Er:Lu2O3[ Reference Liang, Li, Zhang, He, Kalusniak, Zhao and Kränkel9] and Er:Y2O3[ Reference Sanamyan, Kanskar, Xiao, Kedlaya and Dubinskii10, Reference Ding, Li, Wang, Shen, Wang, Tang and Zhu11], have demonstrated continuous-wave (CW) output powers of the order of 10 W, while erbium-doped yttrium aluminum perovskite (Er:YAP)[ Reference Yao, Uehara, Kawase, Chen and Yasuhara12] has achieved a high slope efficiency of 30.6% with an output power of 6.9 W. Due to their lower phonon energy, Er-doped fluoride crystals (e.g., yttrium lithium fluoride (YLF), BaY2F8, CaF2 and SrF2) have also been widely studied for 2.8 μm lasers[ Reference Svejkar, Sulc, Nemec and Jelínková13– Reference Wyss, Luthy, Weber, Rogin and Hulliger21]. Among these, Er:CaF2 lasers have shown the highest output power of 14.5 W[ Reference Zhu, Zhang, Wang, Ding, Jiang, Zhao, Xie, Xu and Su19]. However, this required tailoring the pump beam profile to match the slab geometry, which induced higher-order transverse modes in the x-direction and led to a beam quality factor (M²) exceeding 30, thereby limiting practical applications. Overall, Er-doped crystal lasers still face challenges such as limited heat dissipation and relatively low beam quality.

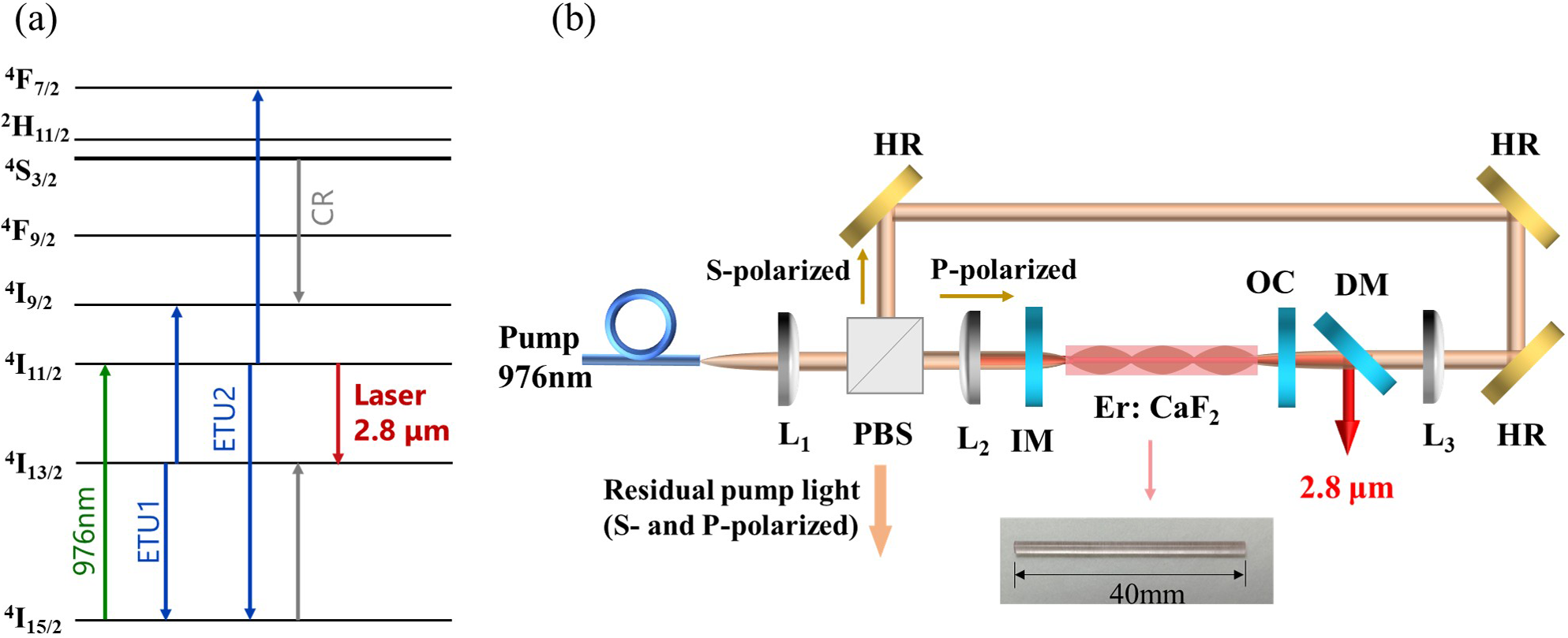

Figure 1 (a) Energy-level diagram of Er3+ ions in Er:CaF2 SCF, showing energy transfer upconversion (ETU, blue), cross-relaxation (CR, gray), pump (green) and laser (red) transitions. (b) Schematic of the Er:CaF2 SCF laser setup. Inset: photograph of the Er:CaF2 SCF.

A single-crystal fiber (SCF) refers to fiber-like thin crystal rod with a typical diameter of the millimeter scale and a length of several centimeters, which guides pump light via total internal reflection while allowing the laser to propagate freely[ Reference Sangla, Martial, Aubry, Didierjean, Perrodin, Balembois, Lebbou, Brenier, Georges, Tillement and Fourmigué22– Reference Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Wang, Wu, Lin, Kusalik, Jia and Tao24]. SCFs combine the advantages of bulk crystals with high thermal conductivity and optical fibers with a large surface-to-volume ratio for heat dissipation. They are widely used in sensing, imaging, medicine and chemical applications[ Reference Habisreuther, Elsmann, Pan, Graf, Willsch and Schmidt25– Reference Deng, Loterie, Konstantinou, Psaltis and Moser28] and, most notably, high-power laser systems[ Reference Délen, Piehler, Didierjean, Aubry, Voss, Ahmed, Graf, Balembois and Georges29– Reference Liu and Ohodnicki31]. However, there have been only a few reports on mid-infrared SCF lasers in the 3 μm region to date. SCF lasers based on Er:YSGG and erbium- and praseodymium-codoped gadolinium yttrium scandium gallium garnet (Er,Pr:GYSGG) have been demonstrated, but only with CW output powers below 1 W[ Reference Han, Sun, Zhang, Luo, Quan, Hu, Dong, Chen and Cheng32– Reference Han, Sun, Zhang, Luo, Quan, Chen, Qiao, Wang and Cheng34]. Owing to the clustering effect of trivalent rare-earth ions in fluoride materials, a strong ETU1 process occurs even at low doping levels. Some progress has also been made with low-doping fluoride SCFs[ Reference Wang, Tang, Liu, Qian, Wu, Wu, Liu, Mei and Su35– Reference Zong, Yang, Liu, Zhang, Jiang, Liu and Su37]. For instance, Er:SrF2 and Er:CaF2 SCF lasers have achieved high slope efficiencies[ Reference Wang, Tang, Liu, Qian, Wu, Wu, Liu, Mei and Su35, Reference Zhang, Wu, Wang, Zhang, Wang, Liu, Liu and Su36]. However, the output powers in these SCF laser systems remained at only approximately 1 W.

In this work, the CW laser performance of Er:CaF2 SCF was investigated in a compact resonator pumped by a 976 nm LD. The thermal lensing effect and its influence on mode matching were analyzed. Through appropriate thermal lens compensation, the Er:CaF2 SCF laser delivered a maximum output power of 10.02 W, with a slope efficiency as high as 32.2% for pump powers below 25 W. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the highest output power reported so far for SCF lasers in the 3 μm wavelength region. It indicates that Er:CaF2 SCFs are promising gain media and lay the foundation for developing high-power mid-infrared laser sources.

2 Experimental details

The laser setup is shown in Figure 1(b). The Er:CaF2 SCFs (1% and 2% (atomic fraction) Er-doping) were fabricated through precise mechanical processing of bulk crystals grown by the vertical Bridgman (VB) method. They are generally transparent with a pale pink color and have dimensions of 40 mm in length and 1.5 mm in diameter, as shown in the inset of Figure 1(b). The waveguide-like structure of the SCF enables the pump light to undergo total internal reflection. Both end faces of SCFs were polished but uncoated. The measured absorption ratios of 1% and 2% Er:CaF2 SCFs were 79.3% and 94.4%, respectively. The SCFs were wrapped in indium foil and mounted in a water-cooled copper bracket for efficient heat dissipation, and the cooling water temperature was maintained at 8°C.

A double-end pumping configuration was implemented using a fiber-pigtailed 976 nm LD with a fiber core diameter of 105 μm and a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.22. The M² factor of the pump beam is approximately 37.2. The pump beam was collimated by lens L1 (f = 30 mm) and subsequently divided into two beams with a polarizing beam splitter (PBS). The P-polarized light was focused forward into the SCF through lens L2 (f = 250 mm), while the S-polarized light was focused backward into the SCF through lens L3 (f = 250 mm). The residual pump light caused by incomplete absorption in the SCF was handled by the PBS, which reflected the S-polarized light and transmitted the P-polarized light, thus preventing feedback into the LDs, as shown in Figure 1(b). Considering the thermal lensing effect of Er:CaF2 SCF, a relatively large pump spot can mitigate the thermal lensing effect. The plano-concave input mirror (IM) has a radius of curvature (ROC) of –100 mm. Both surfaces were coated with anti-reflection (AR) films at the pump wavelength, while the concave surface was coated with high-reflection (HR) film at the laser wavelength. Output couplers (OCs) with different ROCs (–50 mm, –100 mm, ∞) and transmissions (1.5%, 4%, 10%) were used to optimize laser performance. All OCs were AR-coated at the pump wavelength. The cavity length affects both mode matching and round-trip loss, where the latter is dominated by water vapor absorption. Experimentally, we adjusted the cavity length and found that the maximum output power was obtained at the length of 67 mm. A dichroic mirror (DM) placed at 45° was used to separate the output laser from the pump light.

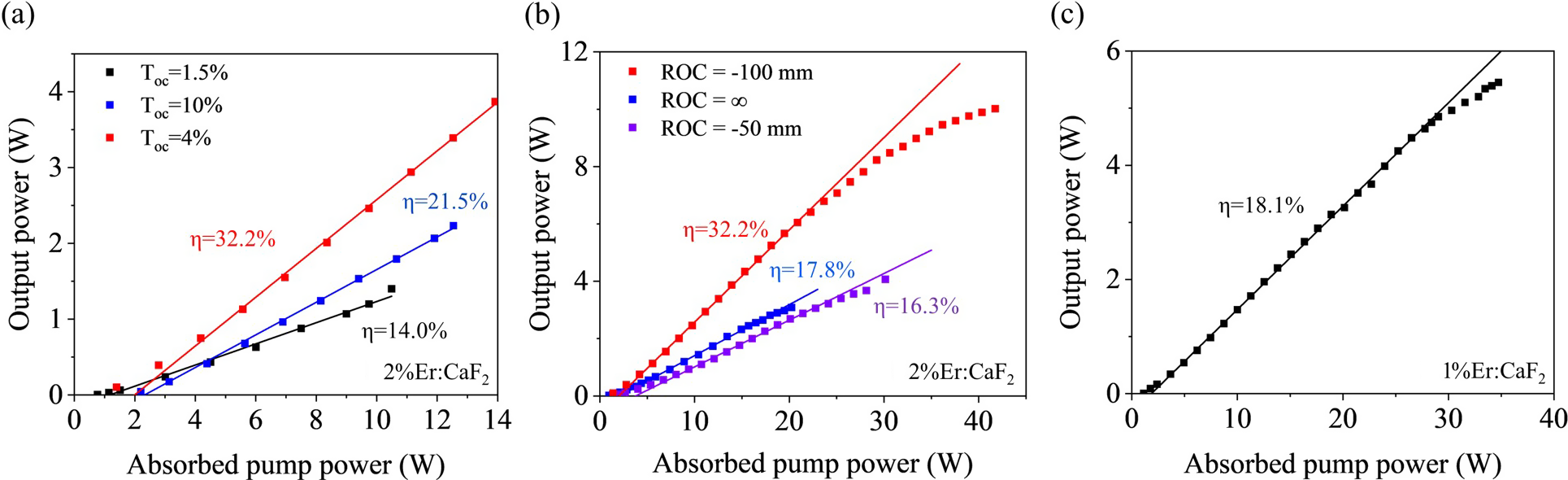

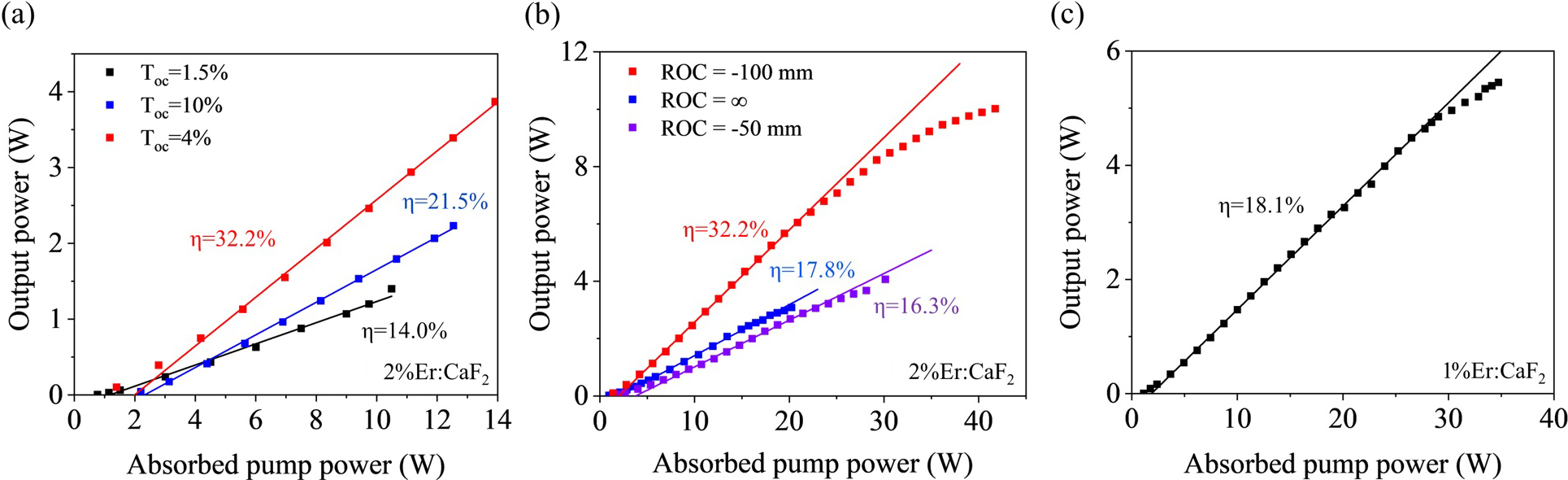

Figure 2 Output performance of the Er:CaF2 SCF laser: (a) 2% Er:CaF2 SCF with OCs of different transmissions (ROC = –100 mm); (b) 2% Er:CaF2 SCF with OCs of different ROCs (T = 4%); (c) 1% Er:CaF2 SCF with an OC of ROC = –100 mm (T = 4%).

3 Results and discussion

The performance of the 2% Er:CaF2 SCF laser was first studied using OCs with transmissions (T) of 10%, 4% and 1.5% (all with ROC = −100 mm), as shown in Figure 2(a). Among these OCs, the laser using the OC with T = 4% achieved the highest slope efficiency. Based on this result, the laser performance using OCs with different ROCs (all with T = 4%) was compared, as shown in Figure 2(b). The laser thresholds were approximately 2, 1.4, and 1 W for OCs with ROCs of –50 mm, −100 mm and ∞ (flat), respectively. The best performance was obtained using the OC with ROC of –100 mm. With this OC, when thermal lensing effect was relatively weak, the intracavity mode matching remained good, resulting in a laser slope efficiency as high as 32.2% for pump powers below 25 W. At higher pump powers, stronger thermal lensing effects led to an expansion of the laser mode and poor mode matching, which caused a decrease of slope efficiency. Ultimately, a maximum output power of 10.02 W was achieved under an absorbed pump power of 41.75 W. As the pump power was further increased, the output power stagnated or even declined without damaging the SCF. This indicated that mode mismatching and cavity instability at excessively high pump powers limited further increase of the laser output. Higher laser power may be obtained by improving the cooling method. The slope efficiencies were lower when using the plane OC (ROC = ∞) or the OC with ROC of –50 mm owing to poor mode matching values, which were only 17.8% and 16.3%, respectively. In addition, the performance of the 1% Er:CaF2 SCF laser was also investigated using a cavity consisting of two concave mirrors with ROC = –100 mm (T = 4% for the OC), as shown in Figure 2(c). Due to the weaker thermal lensing effect, the slope efficiency remained unchanged until the pump power reached 30 W. A maximum output power of 5.45 W was obtained under an absorbed pump power of 34.75 W, corresponding to a slope efficiency of 18.1%.

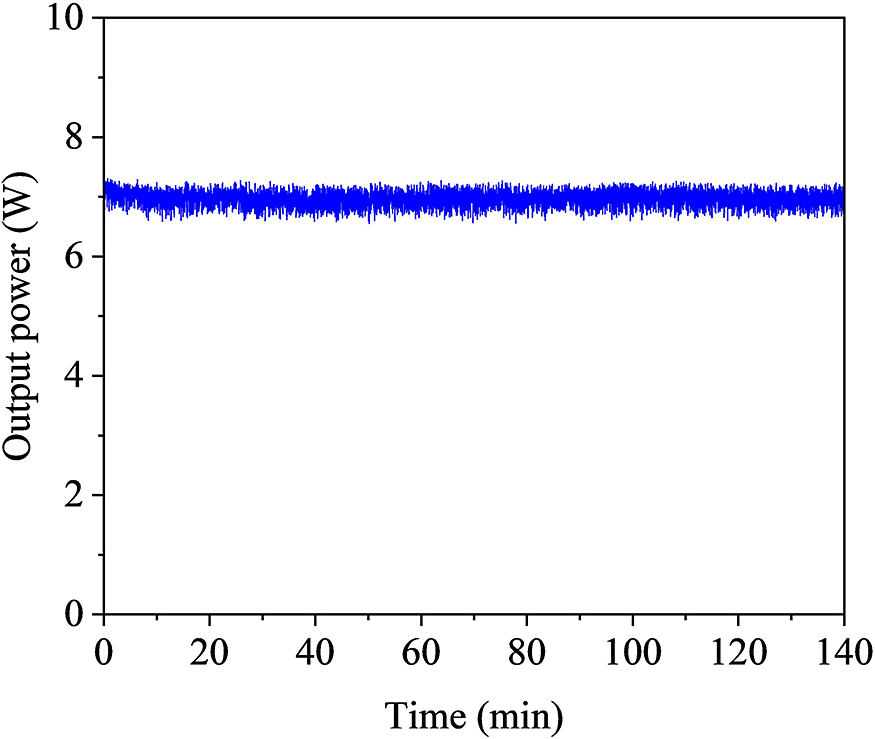

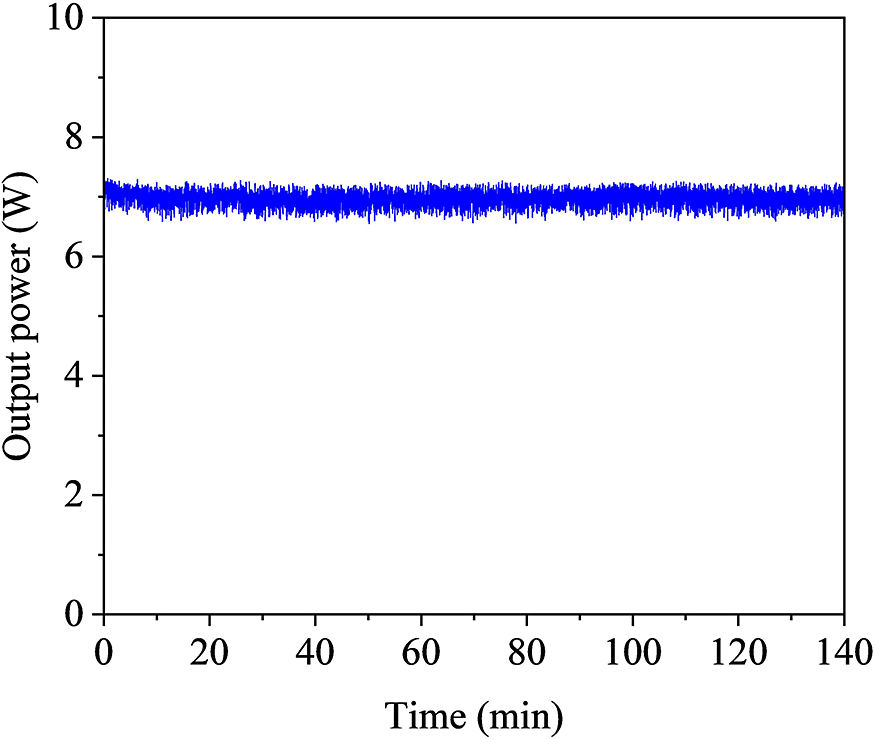

Figure 3 Output power stability of the 2% doping Er:CaF2 SCF laser.

To evaluate the power stability of the laser, we monitored its output power at 7 W for 140 m, as shown in Figure 3. The stability test was not performed at the maximum power to avoid the risk of damaging the SCF. The measured power fluctuation is approximately 1.84%. This slight instability may be attributed to the vibration and temperature fluctuation of the water-cooling system. If a thermoelectric cooler (TEC) is used for heat dissipation, the power stability may be further improved[ Reference Liang, Li, Zhang, He, Kalusniak, Zhao and Kränkel9].

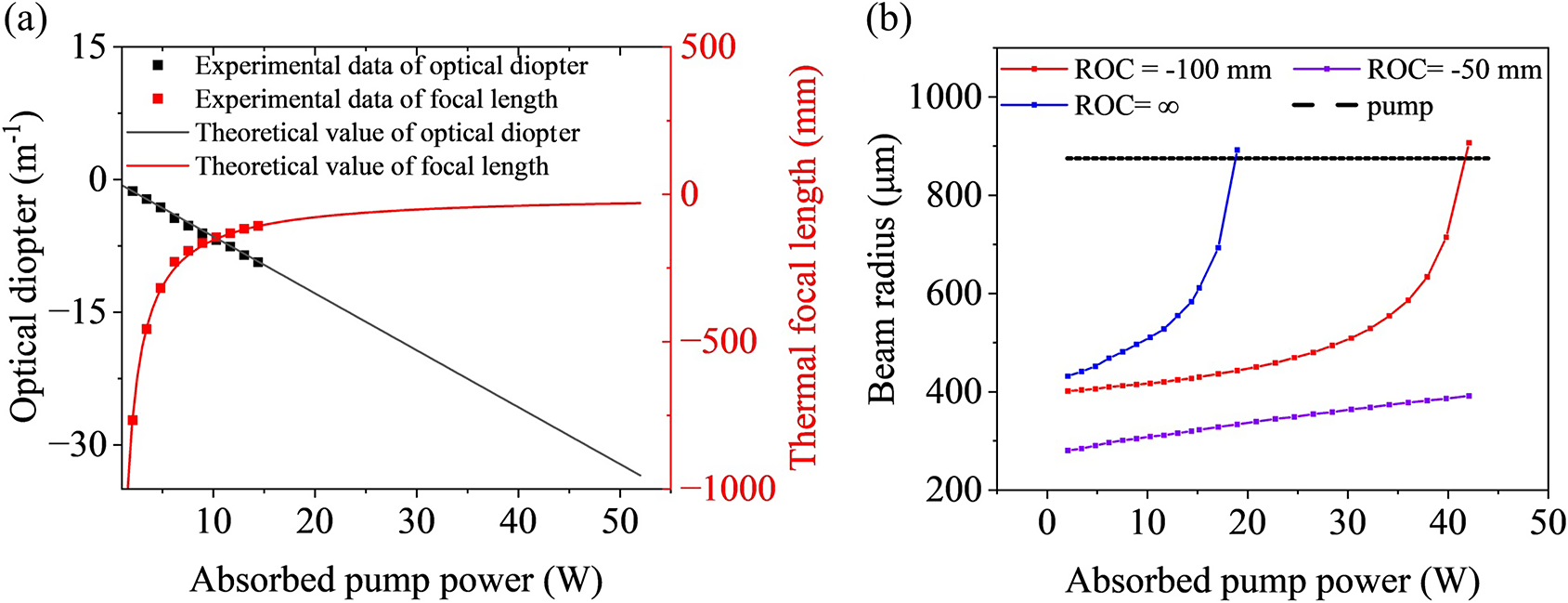

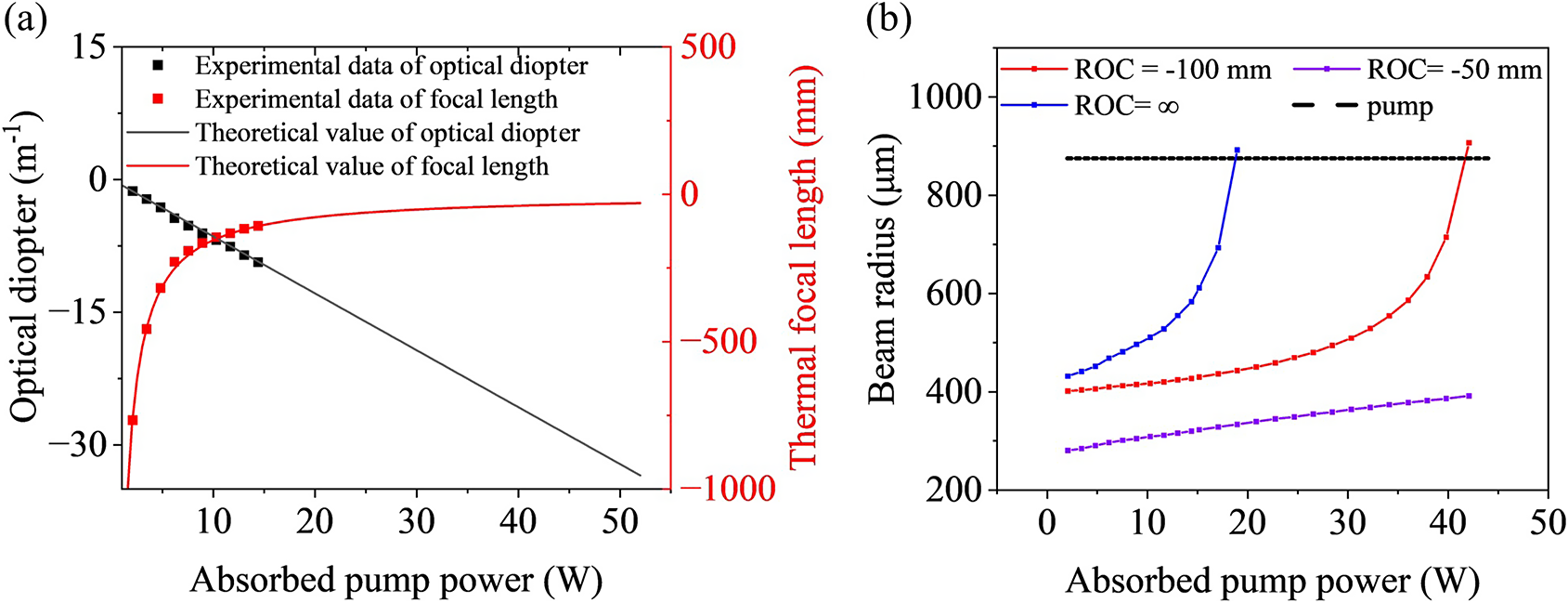

Figure 4 (a) Thermal focal length and optical diopter of the experimental and theoretical values as a function of absorbed pump power. (b) Laser beam waist radius in the SCF dependent on absorbed pump power.

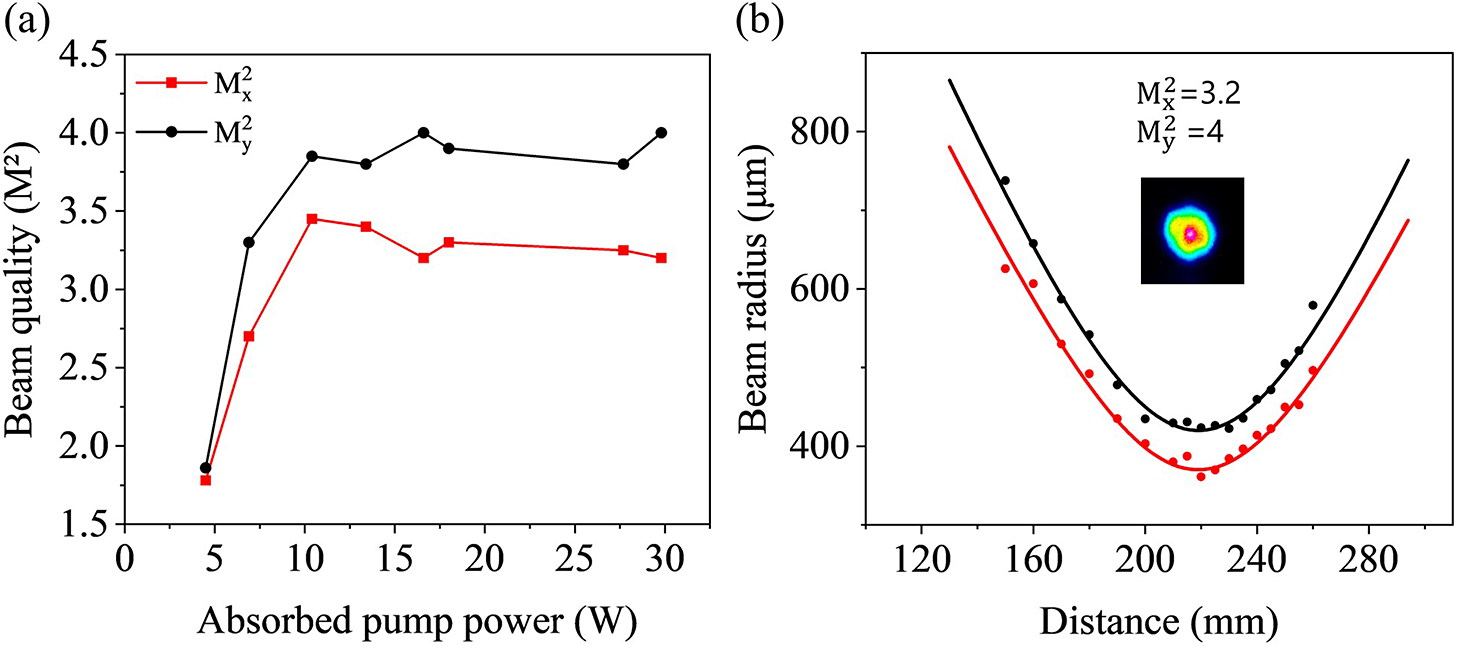

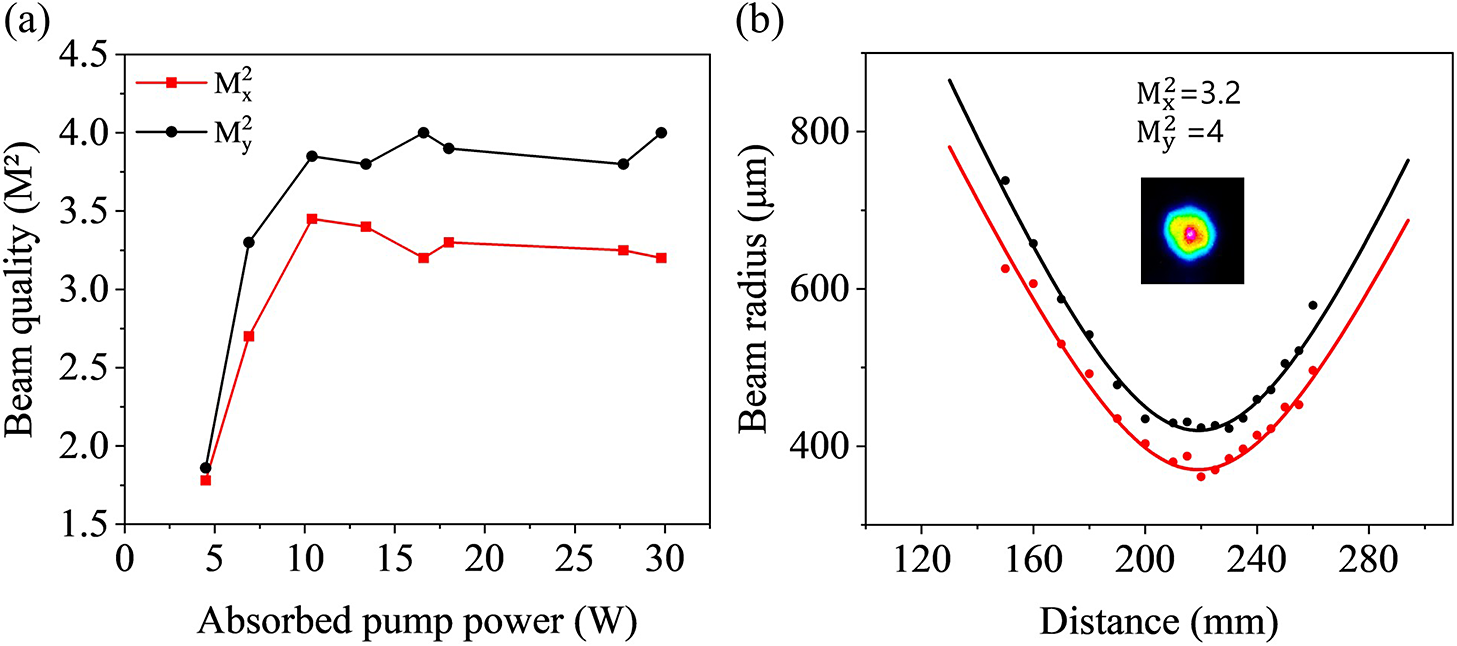

Figure 5 Beam quality factor (M 2) of the 2% doping Er:CaF2 SCF laser at different absorbed pump powers (a) and at 30 W of absorbed pump power (b). The inset of (b) shows the beam profile.

From Figure 2, it is obvious that the thermal lensing effect cannot be neglected. The thermal focal lengths at different pump powers were measured using the stability condition of the resonator[ Reference Zhang, Sun, Luo, Quan, Zhang, Qiao, Dong, Chen, Wang, Li and Cheng4], as shown in Figure 4(a), revealing that the Er:CaF2 SCF exhibits a negative thermal lensing effect. As the absorbed pump power increased, the focal length of the thermal lens gradually increased. Due to the limited adjustment range of cavity length, we could not directly measure the thermal focal lengths at the highest power, but we were able to calculate them. The thermal lens optical diopter is defined as follows[ Reference Chénais, Druon, Forget, Balembois and Georges38]:

$$\begin{align}D=\frac{1}{f}=\frac{\eta_{\mathrm{h}}{P}_{\mathrm{abs}}}{2\pi {\omega}_{\mathrm{p}}^2{K}_{\mathrm{c}}}\left[\frac{\mathrm{d}n}{\mathrm{d}T}+\left(n-1\right)\left(1+\upsilon \right)\alpha +2{n}^3\alpha {C}_{\mathrm{r}\left(\theta \right)}\right],\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}D=\frac{1}{f}=\frac{\eta_{\mathrm{h}}{P}_{\mathrm{abs}}}{2\pi {\omega}_{\mathrm{p}}^2{K}_{\mathrm{c}}}\left[\frac{\mathrm{d}n}{\mathrm{d}T}+\left(n-1\right)\left(1+\upsilon \right)\alpha +2{n}^3\alpha {C}_{\mathrm{r}\left(\theta \right)}\right],\end{align}$$

where η

h = P

heat/P

abs is the ratio between the generated heat power and the absorbed pump power and ω

p is the radius of the pumping beam, which was averaged to be approximately 594 μm in the SCF. The material parameters include the thermal conductivity K

c, the refractive index n, the thermo-optic coefficient dn/dT, the thermal expansion coefficient α, the Poisson ratio

![]() $\upsilon$

and the photoelastic constant C

r(θ). All the values for Er:CaF2 used in the calculations can be found in Ref. [Reference Basyrova, Loiko, Doualan, Benayad, Braud, Viana and Camy17]. The theoretical results shown in Figure 4(a) are in good agreement with the experimental data. The optical diopter decreases linearly with the absorbed pump power, with a slope of –0.66 m–1/W. According to the relation of f = 1/D, the corresponding thermal focal lengths were calculated, as shown in Figure 4(a). Figure 4(b) presents the calculated laser beam waist radius, taking the thermal focal lengths into account. The IM with ROC of –100 mm and OCs with different ROCs were used in the cavity. When the OC is a plane mirror, insufficient compensation for thermal lensing leads to severe mode mismatching once the absorbed pump power exceeds 19 W. In contrast, the thermal lensing is overcompensated by the OC with ROC = −50 mm, resulting in poor mode matching and low laser slope efficiency. Among these cases, the OC with ROC = –100 mm is the best choice for good mode matching and high laser slope efficiency.

$\upsilon$

and the photoelastic constant C

r(θ). All the values for Er:CaF2 used in the calculations can be found in Ref. [Reference Basyrova, Loiko, Doualan, Benayad, Braud, Viana and Camy17]. The theoretical results shown in Figure 4(a) are in good agreement with the experimental data. The optical diopter decreases linearly with the absorbed pump power, with a slope of –0.66 m–1/W. According to the relation of f = 1/D, the corresponding thermal focal lengths were calculated, as shown in Figure 4(a). Figure 4(b) presents the calculated laser beam waist radius, taking the thermal focal lengths into account. The IM with ROC of –100 mm and OCs with different ROCs were used in the cavity. When the OC is a plane mirror, insufficient compensation for thermal lensing leads to severe mode mismatching once the absorbed pump power exceeds 19 W. In contrast, the thermal lensing is overcompensated by the OC with ROC = −50 mm, resulting in poor mode matching and low laser slope efficiency. Among these cases, the OC with ROC = –100 mm is the best choice for good mode matching and high laser slope efficiency.

The beam quality factors (M 2) of the 2% doping Er:CaF2 SCF laser were measured at different pump powers using a mid-infrared charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, as shown in Figure 5. The laser was configured using an OC with an ROC of –100 mm and T = 4%. At low pump power, the M² factors in the x- and y-directions were 1.78 and 1.86, respectively. As the pump power increased, excitation of higher-order modes led to larger M² factors. Under an absorbed pump power of 30 W, the M² factors were 3.2 in the x-direction and 4 in the y-direction, as shown in Figure 5(b). The slight degradation of beam quality along the y-direction may be caused by uneven heat dissipation. Figure 5(a) shows that the M² factors in both directions changed slightly from 10 to 30 W of absorbed pump power, indicating that the mode of the SCF laser is stable.

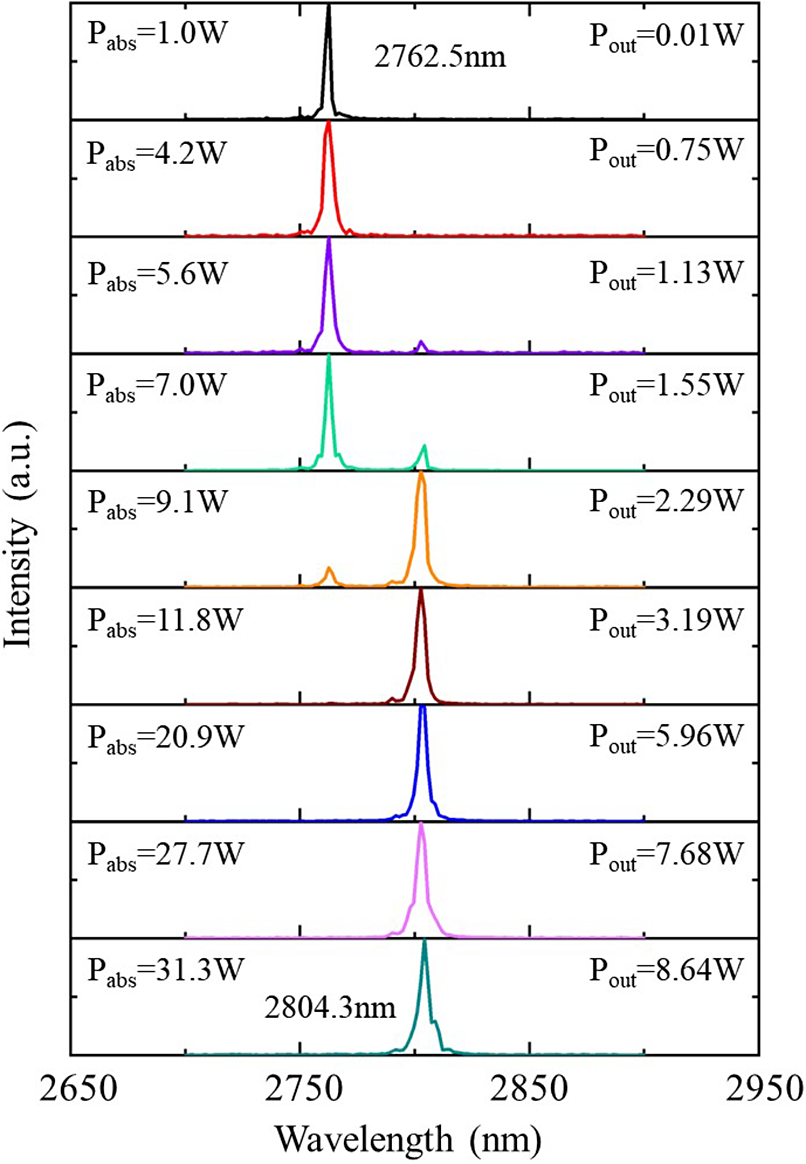

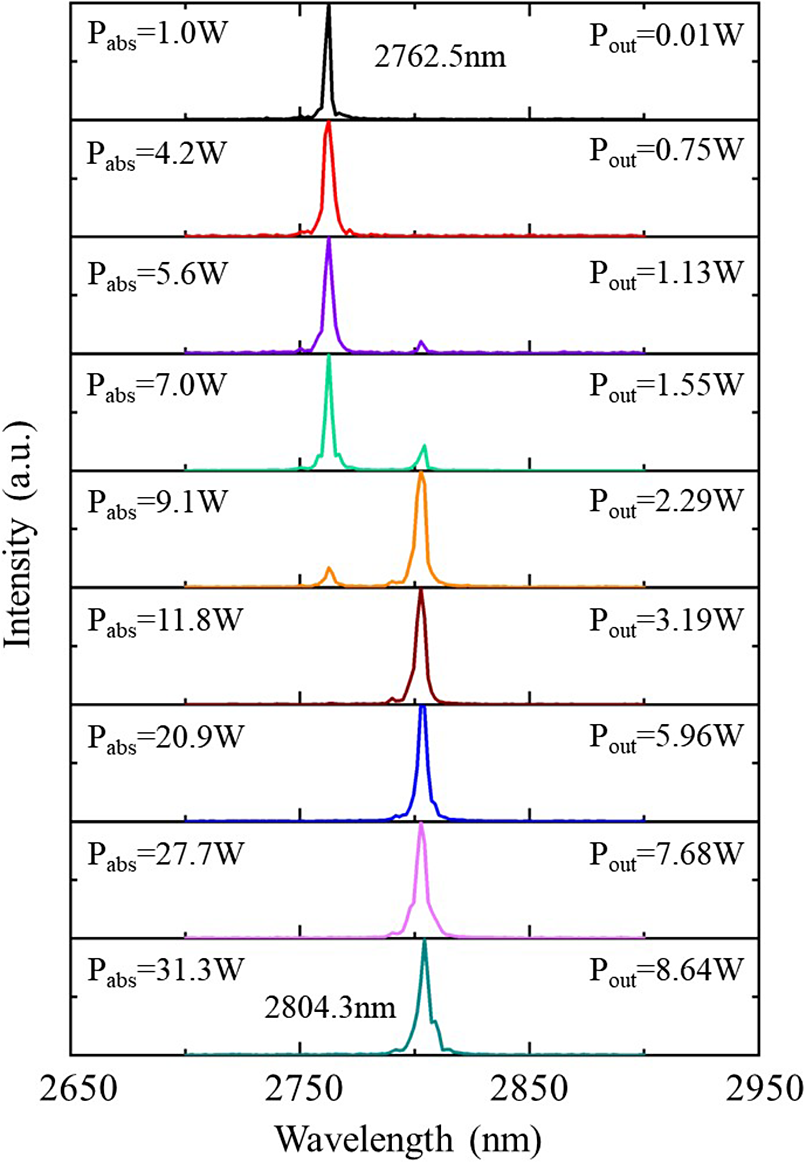

The spectra of the Er:CaF2 SCF laser were recorded, as shown in Figure 6. At low pump power, the central wavelength of the laser was 2762.5 nm. As the pump power increased, the laser wavelength exhibited a redshift and briefly showed dual-wavelength operation. Eventually, the laser maintained stable single-wavelength operation at 2804.3 nm under high pump power, avoiding the region of strong water vapor absorption. This phenomenon is attributed to a redshift of the net gain peak at high intracavity power, where the laser reabsorption at shorter wavelengths becomes stronger. Consequently, the laser emission shifts to longer wavelengths due to the lower loss[ Reference Liang, Li, Zhang, He, Kalusniak, Zhao and Kränkel9, Reference Ma, Su, Xu, Wang, Jiang, Zheng, Fan, Li, Liu and Xu39]. The redshift of the wavelength reduces transmission loss in the air, making it more favorable for developing high-power 3 μm lasers. The output spectrum was also examined over a broad wavelength range, including the 1.5 μm band, and no lasing in the 1.5 μm region was observed.

Figure 6 Output laser spectra of the 2% doping Er:CaF2 SCF laser (ROC = –100 mm, T OC = 4%) at different pump powers.

4 Conclusion

In summary, we experimentally demonstrated a high-power Er:CaF2 SCF CW laser. By optimizing the cavity design and Er-doping concentration, a maximum output power of 10.02 W was achieved, with a slope efficiency as high as 32.2% for pump power below 25 W. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest output power reported for 3 μm SCF lasers to date. The obtained output power represents an order-of-magnitude improvement over previous reports. In addition, the effects of thermal lensing on laser performance and the spectral redshift at high power levels were also explored. These results indicate the potential of Er:CaF2 SCF as an efficient gain medium for the next generation of high-power mid-infrared lasers. The fiber-like geometry, combined with favorable thermal properties of SCFs, enhances laser performance.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFB3507404), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62325506 and 62205359), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. 2023ZKZD19) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.