During the past three decades, political science research has experienced profound transformations. New research questions, technological advancements, shifting university budgets, and a growing awareness of systemic biases, to name only a few, have reshaped the research landscape (Berry Reference Berry and Berry2012; Meyer and Schroeder Reference Meyer and Schroeder2009; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017). Many of these changes have led to greater accessibility, collaboration, and inclusivity. For example, video conferencing and cloud storage have made file sharing and coauthorship easier. Data—whether quantitative or qualitative—are more available and more efficiently analyzed. Journals are making conscious efforts to move beyond traditional behavioralist and institutionalist approaches to consider social, psychological, and cultural analyses.

This digital revolution also has reshaped how research is accessed and disseminated (Berry Reference Berry and Berry2012; Dunlap Reference Dunlap2008). For example, students and faculty members are requesting and accessing fewer physical books. At the University of Virginia, more than 1 million books were circulated in 1999–2000; by 2016–2017, this number decreased to slightly more than 200,000 (Mintz Reference Mintz2024). This shift was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, when physical access to university libraries was restricted, yet faculty and students still could access vast repositories of scholarship—especially journal articles—through online platforms such as Google Scholar. More recently, AI-powered academic search tools such as Elicit have further expanded digital research tools. This shift is not without cost: journal articles often consider narrower, less complex arguments than print books. Moreover, whereas it is suggested that eBooks could mitigate these concerns, user tests reveal that readers consume eBooks differently than physical materials. Specifically, eBook readers rely on keyword searches to find “specific information,” spending an average of only 10 minutes engaging with a digital book (Zhang, Niu, and Promann Reference Zhang, Niu and Promann2017, 578). This contrasts sharply with the way that readers consume print books, and it reimagines research as a finite task rather than an extended thought exercise.

This analysis explores whether the collective effect of these changes in political science specifically and academia more generally has altered patterns of referencing in the discipline during the past three decades. Specifically, by analyzing references in leading political science journals from 1990 to 2024, our study reveals a substantial decline in book references and a corresponding increase in article references. Additionally, we observed significant growth in the total number of references (i.e., books, articles, and other sources), suggesting that scholars now cite multiple articles instead of books, which tend to be broader or more comprehensive. We contend that these changes have significant implications for the production and dissemination of knowledge that will affect students, faculty, research libraries, and academia.

We contend that these changes have significant implications for the production and dissemination of knowledge that will affect students, faculty, research libraries, and academia.

ADVANTAGES OF THE SHIFT FROM BOOK REFERENCES TO JOURNAL ARTICLE REFERENCES

Many of the most significant advantages of an increasing reliance on journal articles over books in political science research result from the much shorter publication timeline (Savage and Olejniczak Reference Savage and Olejniczak2021) and the resulting ability of scholars to address contemporary political issues in a timelier manner. For example, manuscripts submitted to American Political Science Review (APSR) can be reviewed and published in as little as three months on FirstView (Tripp and Dion Reference Tripp and Dion2024), whereas books usually take 1.5 to 3 years to publish (Boboc Reference Boboc2025; Saiya Reference Saiya2022). This expedited review and publishing process has the potential to enhance the discipline’s ability to achieve its fundamental goals: creating “reciprocity between the ‘closet philosopher’ and ‘those engaged in the active walks of political life’ and exerting influence on the ‘world of action’” (Goodnow Reference Goodnow1904, 35, quoted in Gunnell Reference Gunnell2006). Stated simply, a greater reliance on journal articles increases the ability of scholars to address and influence current debates and policy decisions.

Moreover, the greater reliance on journal articles can be advantageous for early-career researchers who need to establish their credentials and contribute to ongoing scholarly conversations. Publication metrics, such as impact factors and citation counts, are used increasingly for hiring, tenure, promotion, and funding decisions (Carpenter, Cone, and Sarli Reference Carpenter, Cone and Sarli2014). The ability to publish quickly—and for others to read and cite this work—may help researchers build their reputation, increase their ability to influence current debates and policy decisions, and make a persuasive case about their contributions to the discipline to administrators and rank and tenure committees.

DISADVANTAGES OF THE SHIFT FROM BOOK REFERENCES TO JOURNAL ARTICLE REFERENCES

The previous discussion highlights several potential positive outcomes of an increasing reliance on journal articles over books. However, there also are significant concerns. First, books often offer more comprehensive and in-depth explorations of topics, covering various perspectives, methodologies, and historical contexts. Journal articles, in contrast, are generally more concise and focus on specific research questions or narrow aspects of a field. They frequently prioritize quantitative methodological approaches, sometimes at the expense of the descriptive, qualitative, and historical analyses necessary for a deep understanding of a problem and the formulation of a comprehensive theory. Journal articles also often lack the interdisciplinary insights provided by books. Consequently, a growing reliance on journal articles may create “echo chambers” and stifle the critical thinking essential for broader synthesis and integration of knowledge.

Second, the pressure to publish frequently can lead to rushed or less thoroughly vetted research. The growing number of journals and, in many cases, increases in the number of manuscript submissions have resulted in reviewer fatigue, making it difficult to find qualified reviewers or resulting in less-than-best reviews (Breunig et al. 2015). Although slower to publish, academic books typically undergo rigorous editorial and review processes, contributing to high quality and thoroughly researched content. Ultimately, the greater reliance on journal articles may result in the referencing and propagation of poorly reviewed or bad research.

HYPOTHESES

Recognizing the evolution of academia, including new research questions, changing curricula and other standards, shrinking budgets, the expansion of online journal databases, and the increase in faculty members working remotely, we posit several hypotheses. First, we suggest that scholars have become increasingly reliant on academic journals as an authority for their research. Specifically, we hypothesize that:

H1a: During the past three decades, the proportion of references to scholarly journal articles has increased.

The corollary likely follows:

H1b: During the past three decades, the proportion of references to books has decreased.

We expect that these changes have been particularly clear since the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., 2020 and beyond). As entire physical campuses transitioned to online operations—some for multiple semesters—students and faculty members faced prolonged periods without easy access to physical books in libraries, and they adjusted by sourcing reference materials online. At the same time, libraries were asked to allocate additional resources to online journal catalogs, necessitating a reduction in their book budgets (Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg Reference Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg2020; Mintz Reference Mintz2024). Furthermore, AI and other tools for accessing and analyzing research and data have grown exponentially. Thus, we posit:

H1c: Growth in the proportion of references to journal articles (as compared to books) accelerated after 2020.

The discipline varies significantly across subfields, each with its own methodologies and research styles. Given this diversity, we anticipate that political theory, which heavily relies on classic texts, will reference a lesser proportion of journal articles (and a greater proportion of books) than other subfields:

H2: Compared to other subfields, political theory will reference a lesser proportion of journal articles.

The consequences of referencing more journal articles also are important to consider. If scholars increasingly reference journal articles, we should observe an increase in the number of references per article. Although changing patterns of referencing may not be the only factor leading to growth in references—other potential explanations include increasing word counts, exempting references from word counts for publication, and an emphasis on citing authors from marginalized backgrounds—it is likely a contributing factor. The logic behind this hypothesis is straightforward: whereas a book has the space to address A, B, C, D, and E, a journal article may have the space to address only A and B. To fill these voids, scholars must reference additional journal articles to address C, D, and E. Thus, we suggest:

H3: An increased reliance on journal articles over books will result in an increase in the average number of references per article.

DATA

To examine changes in journal referencing over time, we analyzed data from 1990 through 2024. This timeframe is recent enough that it reflects the modern discipline—works that form the foundation of much of the literature taught in classrooms and cited today. However, it allowed us to consider equally three potentially important phases of citation. First, it includes approximately 10 to 15 years of research published before the widespread availability of online journals and Internet access in faculty offices and homes. For example, two of the most widely used online databases of scholarly articles, JSTOR and ProQuest, launched in 1995 (“Mission and History” 2004; “ProQuest” 2008); libraries did not begin to adopt these resources widely until the latter part of the decade (Watts Reference Watts2024). Second, there was a 10- to 15-year intermediate period, in which digital tools were well established but many faculty members continued to rely heavily on physical library resources. Third, the last five to 10 years of our analysis reflect shifting library budgets and the post-COVID-19 university. There is no doubt that the next wave is approaching rapidly and will reflect additional changes because of AI research tools.

Our study focuses on top-ranked political science journals (Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003), supplemented by a purposeful sample to explore variations across different subfields and methodologies. Garand and Giles’ rankings were based on a subjective survey of 565 political scientists who were asked to rank the impact, evaluation, and familiarity with more than 100 journals in the discipline. This survey, conducted in the middle of our study period, ranked APSR, American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics, World Politics, International Organization, and British Journal of Political Science as the top overall journals in the discipline. To these, we added Perspectives on Politics, an APSA journal established in 2003, and subfield-specific journals (i.e., Comparative Political Studies, International Studies Quarterly, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Policy Analysis & Management, Journal of Urban Affairs, Public Administration Review, and Political Behavior) based on their rankings in the survey (Garand and Giles Reference Garand and Giles2003, 296).Footnote 1 Footnote 2

We coded the subfield and the references (manually and using machine learning) of the first 10 articles published by each journal at the beginning and the midpoint of each decade within our study period, as well as for 2024 (i.e., 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020, and 2024).Footnote 3 In total, our analysis included 872 articles with 50,453 citations (Yanus and Ardoin Reference Yanus and Ardoin2025).Footnote 4

ANALYSIS

We begin by testing our specific propositions, starting with Hypotheses 1a and 1b. Specifically, we anticipated that during the 34-year study period, references to academic journals became more frequent and references to books decreased.

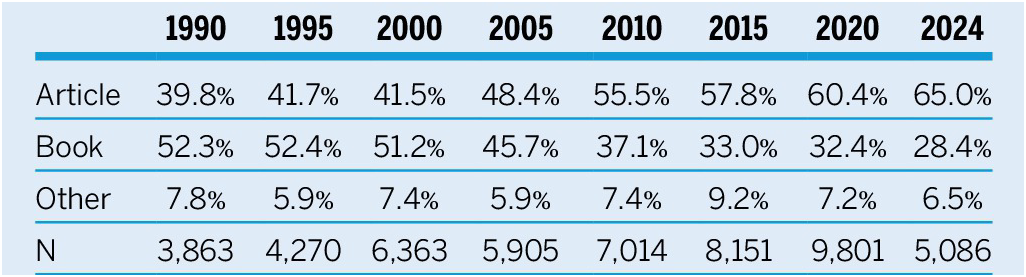

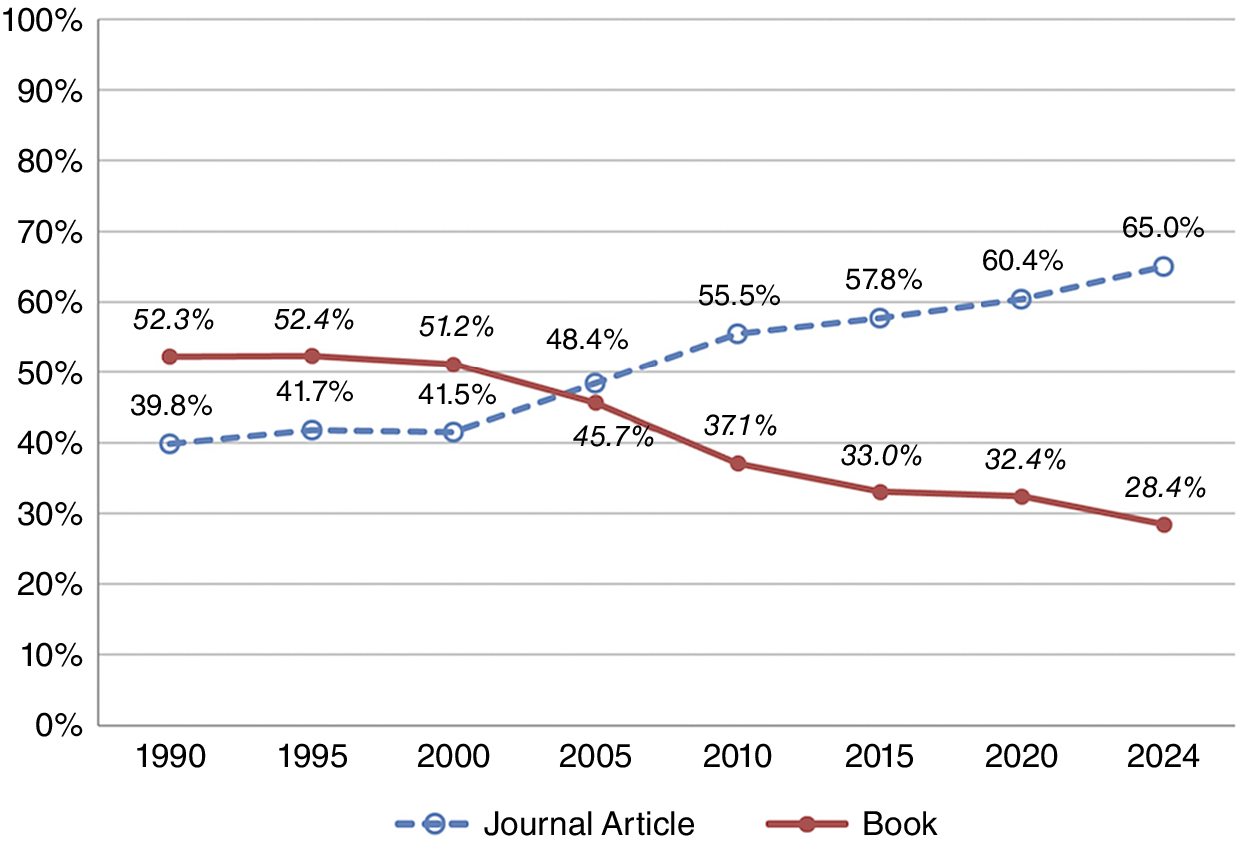

These changes are illustrated in figure 1 and the full data are presented in table 1. In 1990, books constituted more than half (52.3%) of all references and journals constituted less than 40%. Over time, references to books have decreased steadily, replaced by a growing reliance on journal articles. In 2005, the first year in the collected data that journal references surpassed book references, the proportion of references to each was almost equal (i.e., 48.4% of references were to journals and 45.7% were to books). However, in the subsequent 20 years, journal references have dramatically surpassed book references: in 2024, 65% of references were to journal articles and only 28.4% were to books.Footnote 5 A two-sample t-test reveals that the difference between the proportion of book and journal article references in 1990 and 2004 is statistically significant (t= –1025.19, p<0.000).

Over time, references to books have decreased steadily, replaced by a growing reliance on journal articles.

Table 1 References by Type, 1990–2024

Figure 1 References to Books and Journal Articles, 1990–2024

Hypothesis 1c further suggests that there should be evidence of an additional reliance on journal articles after the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. This hypothesis also is supported by the data. The percentage of references to journal articles increases by 5 percentage points between 2020 and 2024 (from 60.4% to 65.0%); this difference is both statistically and substantively significant (two-sample t-test; t=-231.24.19, p<0.000). As figure 1 illustrates, this four-year period represents a noteworthy deviation from the relative stability in reference patterns observed between 2010 and 2020. That is, it resembles the period between 2000 and 2010 when online repositories began to be more widely adopted by a wide range of academic libraries and accessed by students and faculty.Footnote 6

Variations by Subfield

We did not expect that scholars’ reliance on books and articles would be consistent across subfields. Instead, Hypothesis 2 posits that political theory, which relies more on classic texts, will reference fewer journal articles. The data shown in figure 2 and table 2 provide support for this claim. Only modest differences in the number of references to journal articles by subfield existed before the late-twentieth-century revolution in digital access. However, between 2000 and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, political theory articles averaged only about 30% of references from journal articles. The other subfields experienced an upward trajectory in journal references, increasing from about 50% of all references in 2000 to approximately 60% of references in 2020, which is a 20- to 30-percentage-point difference between political theory and the other subfields.

Table 2 References to Journal Articles by Subfield, 1990–2024

Figure 2 References to Journal Articles by Subfield, 1990–2024

During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, however, political theory looks more like other subfields, particularly American and comparative politics. In fact, much of the post-COVID-19 increase in journal references observed in testing Hypothesis 1c is attributable to dramatic changes in political theory and international relations. The proportion of references to journal articles in American and comparative politics and public administration remained almost constant with their 2000 levels, but references to journal articles in political theory and international relations increased by approximately 25%. If this trend persists, it may enhance the subfield’s ability to make timely connections to “those engaged in the active walks of political life” and influence the “world of action” (Goodnow Reference Goodnow1904, 35).

It also is noteworthy that although we do not discuss it in this article, the inverse can be said about book citations. Between 2000 and 2020, approximately 60% of references in political theory articles were to books, whereas book references in other subfields declined from approximately 50% of all references in 2000 to closer to 25% by 2024.

Consequences: Contributing to an Increase in References?

The shift from referencing books to journal articles has numerous consequences for the discipline. Exploring all of these implications is beyond the scope of this study; however, we can examine one significant trend: how an increasing reliance on journal article references affects overall reference counts. Hypothesis 3 suggests that although it is not the only potential cause, a growing reliance on journal articles may contribute to an increase in the average number of references per article.

Table 3 provides clear support for this proposition. In no case did a journal reference fewer sources in 2020 or 2024 than in 1990. A review of the individual-level data finds that only 4% of articles in 1990 included more than 100 references compared to more than 10% in 2024. Overall, most journals increased their overall number of references by about a quarter or a third. However, the increases in some journals—particularly subfield-specific outlets—were much greater. For example, the 1990 articles from the Journal of Conflict Resolution cited only 315 articles; by 2020, this number had increased almost threefold to a total of 878.

Table 3 Total Number of References by Journal, 1990–2024

Figure 3 provides further evidence of these changes. In 1990, the average number of references per article in all of the journals we studied was 43; by 2024, the average number increased to 71, which represents a 65% increase over time. Figure 3 also illustrates the changes in the average number of references per article in the three major journals (i.e., APSR, American Journal of Political Science (AJPS), and Journal of Politics (JOP)), revealing a significant increase for each journal. Potentially because of its higher maximum word count, APSR represents somewhat of an outlier. Even with an average rate of 60.2 references per article in 1990, APSR increased to 84.8 references per article in 2024. It is interesting that three of the 10 APSR articles examined in our 2024 analysis included more than 100 references. Future analyses should explore in depth the potential causes of this increase considering not only the type of references but also the ratio of references to length and the authors whose work is being cited.

Figure 3 Average Number of References by Year and Journal, 1990–2024

CONCLUSION

This analysis demonstrates a clear increase in references to journal articles (as opposed to book sources) between 1990 and 2024, accelerating after the COVID-19 pandemic. With minor variations, these changes generally are present regardless of subfield and journal.

The increasing reliance on journal articles over books in scholarly research is a complex phenomenon with far-reaching implications, including an overall increase in references per article. These changes may serve the purposes of the discipline and provide potential benefits for accessibility, tenure, and promotion. However, they also raise concerns about the depth of analysis, the nature of academic discourse, and the evaluation of scholarly work. Online search engines and AI referencing tools—heavily driven by algorithms—also may introduce additional biases in referencing, including to literature that scholars cannot read or access. At what point do scholars decide to reference an article that seems to substantiate their work but is inaccessible due to a publisher’s paywall or, worse, may be the result of an AI hallucination and not even exist? To what extent do search engines and the strategic use of keywords have a more significant impact on citation counts than the quality of research?

These changes may serve the purposes of the discipline and provide potential benefits for accessibility, tenure, and promotion. However, they also raise concerns about the depth of analysis, the nature of academic discourse, and the evaluation of scholarly work.

The economics of academic publishing also may shift as journal articles continue to become more dominant. This could affect traditional academic publishers, university presses, and libraries, potentially leading to new business models and changes in how research is funded and disseminated (Davidson Reference Davidson2005). It also may accelerate the adoption of new technologies in academic publishing, such as enhanced online platforms for collaboration and data sharing. Corporate libraries, which have experienced similar disruptive changes, may provide insight for academic libraries in maintaining relevance in an increasingly digital research environment (Housewright Reference Housewright2009).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

These preliminary findings document important changes that merit further investigation related to references as well as the scholars who are conducting the research. Regarding how patterns of referencing have changed: (1) exploring in more depth the differences not only in these top-ranked journals but also other niche-specific and lower-ranked journals could shed light on changes in the discipline, training, and institutional resources; and (2) exploring biases (e.g., in authors, publishers, and venues) in the specific books and articles being cited may speak not only to how knowledge is shaped but also to potential effects on tenure and promotion decisions.

With respect to authors, there are many variables to consider about the identity of scholars and the sources that they regard as authorities and/or have the resources to access. For example, are women-identifying faculty members—who typically have greater familial pressures and are more likely to be in contingent and teaching-centered positions—more likely to reference articles than books? Or are biases more institutional than based on descriptive characteristics? For example, do scholars at non-research universities exhibit different citation patterns than those at research institutions? Similarly, how does online, English-language access to journals affect the ability of scholars located outside of the United States to publish in major English-language political science journals? How, if at all, do these trends intersect with the increase in international editorial teams, including at the top three journals (i.e., APSR, AJPS, and JOP) in the discipline? There also are important questions about author teams, including how the number and seniority of coauthors may affect the type and variety of works cited.

Finally, the findings of this study demonstrate how citations have changed but cannot fully explain why. We suspect that availability, access, and financial shifts may be major driving factors behind the growing reliance on journal articles. However, other potential explanations merit investigation. Perhaps shifting faculty workloads and the growing demands of the tenure process (where it is available) encourage scholars to publish their best ideas in journal articles rather than books. Alternately, the growing emphasis of graduate institutions on journal articles over books in their curriculum, including the emergence of the three-article dissertation, may be an important contributing factor. These changes also may be the result of asking and answering new types of questions in the discipline—particularly in some subfields as suggested by the changes in international relations and political theory discussed in this article. Or it may be due to the types of data that researchers collect and analyze, including the increase in large off-the-shelf databases and the lower cost of original survey research. Understanding how these factors affect scholars’ decisions regarding authoritative sources (and, therefore, references) would be an important contribution to guiding how departments, universities, and associations support scholarly work and how, as teachers, we design our courses and curricula moving forward.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research on this project was conducted while Professor Yanus was the Daniel B. German Visiting Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Appalachian State University. The authors are grateful for the support provided by this position, as well as for the research assistance of Samuel Shaver and Sydney Ianelli and the helpful comments provided by Laura Showalter and the anonymous reviewers.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KFZ3NZ.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.