Introduction

Climate change is among the most pressing issues of our time. While countries of the Global North are responsible for much of the accumulated stock of greenhouse gases, Global South countries are more exposed and less prepared to handle climate disruptions (Wei et al. Reference Wei, Yang and Moore2012; Hanna and Oliva Reference Hanna and Oliva2016; Dolšak and Prakash Reference Dolšak and Prakash2022). Recognizing this inequity, the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, which placed mandatory obligations to reduce emissions on the Global North countries (listed in Annexure 1). In addition, given their historical responsibility in causing the climate crisis, Global North countries have pledged to support the Global South to adapt to future climate disruptions. Finally, although not examined in this paper, Global North countries have also pledged to create a Loss and Damage fund to compensate Global South countries for the damage from climate events.

Overseas support for climate adaptation can take many forms. For example, Global North countries could provide funding for sea walls, irrigation projects, and new drought-resistant crop technologies. Migration is another form of climate adaptation (Bettini Reference Bettini2014; Vinke et al. Reference Vinke, Bergmann, Blocher, Upadhyay and Hoffmann2020). In contrast to in situ adaptation, which supports communities where they reside, ex situ adaptation involves relocating individuals, households, and communities to areas with higher levels of climate resilience. These areas could be within the country or overseas. Thus, the willingness of a Global North country to accept climate migrants from overseas could be viewed as a form of ex situ adaptation assistance.

Overseas climate aid might face domestic opposition. With persistent budgetary problems that most countries in the Global North face, their governments could be criticized for allocating funds abroad and neglecting domestic priorities. Moreover, there is a perception that international aid is sometimes not used properly. Along with ‘aid capture’, the lack of technical and administrative skills often leads aid recipient countries to mismanage aid monies. Some suggest that the perception of aid misuse has led to ‘aid fatigue’ in many donor countries (Loxley and Sackey Reference Loxley and Sackey2008; Bauhr et al. Reference Bauhr, Charron and Nasiritousi2013).

Domestic groups could oppose immigration as well because they fear adverse labor market outcomes (Green Reference Green2009; Haaland and Roth Reference Haaland and Roth2020) or see immigration as a cultural threat (Green Reference Green2009; Harell et al. Reference Harell, Soroka, Iyengar and Valentino2012; Yılmaz Reference Yılmaz2012). Opposition to immigration could also depend on which overseas country is sending migrants (Shehaj et al. Reference Shehaj, Shin and Inglehart2021). Support for right-wing parties (Greven Reference Greven2016; Mazzoleni and Ivaldi Reference Mazzoleni and Ivaldi2022; Jäger Reference Jäger2023) increases when the public perceives a high economic and cultural distance between immigrants and the local population (Shehaj et al. Reference Shehaj, Shin and Inglehart2021). In the Netherlands, the country we focus on in this paper, Geert Wilders’ party has exploited the anti-immigrant sentiment (van der Valk Reference Valk2019; Kiesraad 2023) and emerged as the single largest party in the 2023 elections.

Our paper makes a theoretical contribution by considering aid and migration, along with the characteristics of aid-recipient and migrant home countries in the same framework. Though historically, aid and migration have been discussed as two different topics, in recent years, scholars have also noted the link between them (Berthélemy et al. Reference Berthélemy, Beuran and Maurel2009; Bermeo and Leblang Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015; Gamso and Yuldashev Reference Gamso and Yuldashev2018; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs and Langlotz2019). This linkage is also reflected in the policy discourse. As the New York Times (Kitroeff et al. Reference Kitroeff, Shear and Volpe2021) reported, President Biden made a case to increase foreign aid to Central America to reduce the incentives of their citizens to migrate to the United States. In his speech to the US Congress, he said: ‘When I was vice president, I focused on providing the help needed to address these root causes of migration’, Mr. Biden said in a recent speech to Congress. ‘It helped keep people in their own countries instead of being forced to leave. Our plan worked’ (Kitroeff et al. Reference Kitroeff, Shear and Volpe2021). As President Trump, at the start of his second presidential term, announced the closure of USAID, there were reports on how the aid cutback would increase migration (Flavelle Reference Flavelle2025). In the UK (GOV.UK 2024), the Labour government has allocated £84 million in aid to curb migration (Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office). In the last decade, the European Union has used aid extensively to manage migration (Cook Reference Cook2024). Thus, in the policy sphere, foreign aid is being deployed as an instrument of migration policy.

Theoretically, we move the aid and migration debate in a new direction. While not focusing on any explicit aid-migration tradeoff, we explore the role of both aid and migration together in an overseas climate policy package that the Netherlands might offer (Uji et al. Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021; Andonova et al. Reference Andonova, Zucca, Montfort, Dolšak and Prakash2025). Specifically, using a conjoint forced-choice experiment, we explore Dutch citizens’ support for an overseas climate adaptation package, which has multiple dimensions such as different levels of climate aid (in situ adaptation) and climate migration (ex situ adaptation) from countries located on different continents. Because respondents might also assess overseas adaptation support in terms of how the specific country serves economic or policy interests of the Netherlands, we vary countries in terms of their economic and political linkages with the Netherlands.

Hence, we selected four countries (Colombia, Pakistan, Albania, and Somalia) located in Europe, Asia, and Africa (geographical proximity), and none of them is a former Dutch colony. The dominant religion in these countries also varies: Albania, Somalia, and Pakistan are majority Muslim countries, whereas Colombia is mainly Christian. In addition, these countries could reasonably face wildfire, drought, sea level rise, and floods, which we list in our conjoint analysis. None of these countries features in the top 10 in terms of immigration by countries of origin (Ipsos 2021). This provides some confidence that respondents are not likely to be biased toward a specific country by the ongoing immigration debate, where specific countries tend to be named in the media discourse.

This study is inspired by Uji et al.’s (Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021) examination of public support in Japan for an overseas adaptation package. Theoretically, the Netherlands offers a different political climate because, unlike Japan, right-wing populism with its strong anti-immigrant and anti-climate agenda is well established. About 15% of the Dutch population is foreign-born, and immigration is a highly salient domestic political issue. In contrast, immigrants account for just 2.5% of the Japanese population, and immigration is not a politically contentious topic in the country (Uji et al. Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021; OECD 2024). In addition, while historically, the Netherlands has been a climate leader, the rise of right-wing parties and the recent backlash from farmers on climate issues raise questions about the depth of political support for climate policy. And although the Netherlands is a small country of about 18 million, it has an outsized role in world politics (Hellema and Pearson Reference Hellema and Pearson2009). The Netherlands is also the 6th largest donor of climate aid (Donortracker, 2023). Thus, the Netherlands offers a different political context in relation to Japan to study public support for an overseas adaptation package that includes both aid and migration.

In the conjoint experiment, we asked Dutch respondents to compare two policy packages with the same six dimensions (but randomly assigned different values for any dimension): (1) levels of immigration from, (2) aid to, (3) specific countries (Albania, Pakistan, Somalia, and Colombia), (4) specific weather events experienced in the country (sea level rise, wildfire, flood, drought), (5) the country’s imports from the Netherlands, and (6) the country’s intended year to be climate neutral, a policy championed by the Netherlands in international climate forums.

We find that respondents support policy packages with (1) lower numbers of immigrants, (2) lower volumes of aid, (3) with migrants from Albania and Colombia, but not Pakistan and Somalia, (4) from countries with high imports from the Netherlands, and (5) from countries that have pledged to become climate-neutral earlier.

Literature review

Foreign aid scholars have examined issues such as which countries donate, why, how much, in what form, and to which recipient countries (De Haan Reference De Haan2009; Swedlund Reference Swedlund2017; Jakupec and Kelly Reference Jakupec and Kelly2019). Given the high salience of climate change in the policy discourse, an emerging literature examines climate aid focused on issues such as energy transition (Rogner Reference Rogner2013; Halimanjaya Reference Halimanjaya and Papyrakis2015; Reference Halimanjaya2016; Halimanjaya and Papyrakis Reference Halimanjaya and Papyrakis2015; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Ma, Che, Liu and Song2024). In recent years, adaptation has emerged as an important topic in climate discussions because climate change is already in motion, even as countries seek to achieve zero-emission targets. Adaptation poses important challenges because developing countries tend to be more exposed to climate disruptions, but have fewer resources to adapt (Mertz et al. Reference Mertz, Halsnæs, Olesen and Rasmussen2009). Thus, there is an emerging consensus that the Global North should support the Global South in adapting to climate change, in addition to shouldering greater responsibility for climate mitigation.

While migration research, both migration within and across countries, is well established, in recent years, there has been an increased interest in understanding climate migration, the relationship between environmental stress and out-migration (Piguet et al. Reference Piguet and Guchteneire2011; Koubi et al. Reference Koubi, Spilker, Schaffer and Bernauer2016; Ferris Reference Ferris2020). Scholars have employed different methodological approaches to assess the drivers and volume of climate migration (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Šedová and Vinke2021; Böhm and Sullivan Reference Böhm and Sullivan2021), the patterns of climate migration (McLeman Reference McLeman2018), the political response to climate migration (McLeman Reference McLeman2019), securitization of climate migration (Hartmann Reference Hartmann2010; Boas Reference Boas2015), and climate migration as an adaptation strategy (Bettini Reference Bettini2014).

In terms of public perceptions of climate migration, Koubi et al. (Reference Koubi, Spilker, Schaffer and Bernauer2016) assess how perceptions of slow and fast-onset climatic events differ between migrants and non-migrants in home countries. Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer (Reference Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer2020) find that slow-onset climatic events, like droughts, are more likely to lead to out-migration. Recent studies have also examined public support in host countries for climate migration, both internal migrants, as in Vietnam, Kenya, and Bangladesh (Spilker et al. Reference Spilker, Nguyen, Koubi and Böhmelt2020; Castellano et al. Reference Castellano, Dolšak and Prakash2021) as well as for overseas climate migrants (Dempster and Hargrave Reference Dempster and Hargrave2017; Verkuyten et al. Reference Verkuyten, Mepham and Kros2018; McLeman Reference McLeman2019; Basile and Olmastroni Reference Basile and Olmastroni2020; De Coninck Reference De Coninck2020;) in countries such as Germany (Helbling Reference Helbling2020) and Denmark (Hedegaard Reference Hedegaard2022).

Both climate aid and migration represent overseas adaptation policies but have been discussed in different literatures. In recent years, scholars have also begun to assess public support for different types of overseas adaptation policies without necessarily treating them as a part of the same policy package (exceptions include Uji et al., Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021; Andonova et al., Reference Andonova, Zucca, Montfort, Dolšak and Prakash2025). For example, some studies find that aid can reduce the incentives to emigrate (Lanati and Thiele Reference Lanati and Thiele2018; Gamso and Yuldashev Reference Gamso and Yuldashev2018), while others find no effect of aid on out-migration. Other scholars note that aid can motivate migration by increasing income; the logic being that emigration entails individuals incurring upfront costs, which sometimes even require them to sell family assets.

In studying the link between climate aid and climate migration from home countries, Runfola and Napier (Reference Runfola and Napier2016) find no impact of climate aid on migration or migration on climate aid (Runfola and Napier Reference Runfola and Napier2016). Nabong et al. Reference Nabong, Hocking, Opdyke and Walters(2023), however, find that on the one hand, an increase in financial capital leads to increased climate migration flows, suggesting that aid might lead to migration. On the other hand, diminished food security induces migration as well, meaning that climate aid, which improves livelihoods and enhances food security, can also limit climate migration.

While not examined in this study, we note that scholars have examined support for climate aid in recipient countries (Findley et al. Reference Findley, Harris, Milner and Nielson2017; Mohlakoana et al. Reference Mohlakoana, Lokhat, Dolšak and Prakash2023). Other scholars have examined public support in host countries for different levels of climate aid and climate migration. Arias and Blair (Reference Arias and Blair2022) focus on climate mitigation aid and find no increased support in host countries for mitigation as a result of forecasted climate migration (Arias and Blair Reference Arias and Blair2022). Marotzke et al. (Reference Marotzke, Semmann and Milinski2020) find in a laboratory setting that the ‘rich’ try to avoid migration of the ‘poor’ and are willing to increase their efforts at mitigating climate change if the poor are hit by extreme climate events that exacerbate their poverty (Marotzke et al. Reference Marotzke, Semmann and Milinski2020). The issue of public support for overseas climate adaptation aid is somewhat neglected in the literature.

Uji et al.’s research is among the first to examine the support among Japanese respondents (host/donor country) for an overseas adaptation package that includes both climate aid and climate migration (Uji et al. Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021). The primary goal in our study is to replicate Uji et al. in a country context where climate politics is getting articulated along different interest group configurations, where there is a surge in the support for right-wing parties that are skeptical of climate policies, and where there is a backlash to immigration. We follow Uji et al.’s broad template and modify it for the Dutch context.

Argument

We have noted that some politicians have framed aid and migration as alternatives. The reason is that migration is impacted by ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors (Todaro Reference Todaro1969; Wodon et al. Reference Wodon, Burger, Grant, Joseph, Liverani, Tkacheva, Piguet and Laczko2014). A pull factor might be a strong economy of the host country or the presence of the diaspora that attracts migrants. A push factor could be a climate disturbance in the migrant’s home country that impacts livelihoods and food security. These climate events could also cause conflict within and among communities, which will act as a push multiplier. Taken together, these push forces could motivate individuals to migrate to countries where economic and environmental conditions are superior (Wodon et al. Reference Wodon, Burger, Grant, Joseph, Liverani, Tkacheva, Piguet and Laczko2014; Carrico and Donato Reference Carrico and Donato2019; Nabong et al. Reference Nabong, Hocking, Opdyke and Walters2023).

Climate adaptation aid could reduce the severity of push factors by enhancing the capacity of local (home) communities to cope with disruptive climate events. In host countries, politicians seeking to limit immigration flows might justify aid by pointing to the need to address push factors. In her address to the Washington Conference on the Americas, Vice President Kamala Harris noted that the lack of resilience to events such as hurricanes and droughts is among the root causes of migration to the United States (The White House, 2021).

Yet, foreign aid could be unpopular among the donor publics. With persistent budgetary deficits, most governments underfund pressing domestic priorities. Further, aid fatigue might diminish public support for climate aid. At the same time, some might feel that their country has a historical responsibility to assist Global South countries in adapting to climate change (Aarøe & Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020). Therefore, these individuals might support adaptation aid and/or accept climate migrants as opposed to providing development aid and accepting economic migrants (Helbling Reference Helbling2020).

Instead of arbitrating the debate whether aid and migration are substitutes, or whether Global North countries are obligated to provide both more aid and accept more migrants, we frame the issue in terms of climate adaptation politics. At least among policy elites, there is a consensus that the Global North should provide overseas adaptation aid. At the same time, Global North countries are also experiencing large-scale immigration at least since the Syrian civil war, which has contributed to political turmoil. We seek to explore whether public support for a hypothetical overseas adaptation package (with both ex situ and in situ elements) might depend on levels of aid and immigration, characteristics of aid-receiving and migrant host countries, as well as economic and policy connections of these countries with the Netherlands.

Hypotheses

Dutch respondents might feel a level of historical responsibility to help those facing the costs of climate change, particularly if they weren’t major contributors to the climate crisis (Aarøe & Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020; Helbling Reference Helbling2020). This could increase support for both aid and immigration. However, given the existing political climate in the Netherlands, we suggest that respondents will support lower immigration as well as lower aid as elements of an overseas adaptation package. Support for right-wing parties is growing in the Netherlands; right-leaning individuals tend to show lower support for foreign aid and immigration (Paxton and Knack Reference Paxton and Knack2012; Shehaj et al. Reference Shehaj, Shin and Inglehart2021). This opposition could be motivated by a range of issues; for example, some respondents might perceive immigrants as a cultural and labor market threat (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Green Reference Green2009; Haaland and Roth Reference Haaland and Roth2020). Moreover, though climate change has generally been seen as an important issue by many Dutch people, only 33% are willing to spend their own money toward addressing climate change (Ipsos 2021). In addition, the sentiment that the government should devote resources to addressing domestic issues could reduce support for any kind of foreign assistance. Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages with lower levels of overseas climate adaptation aid.

Hypothesis 2: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages with lower numbers of climate immigrants.

Aid has a specific recipient country, and migrants have a specific country of origin. Thus, in addition to the issues around the volume of aid and number of migrants, respondents might favor aid to and migration from specific countries due to cultural similarity, which might motivate respondents to think in terms of in-groups and out-groups. Culture is a multidimensional construct, and we implicitly focus on two dimensions: proximity to the Netherlands and religion.

In the conjoint, we focus on Albania, Somalia, Pakistan, and Colombia to explore whether implicit understanding of their geographical location and religion influences respondents’ support for the overseas adaptation package. These countries are located on different continents, and none of them are former Dutch colonies, an issue that could influence respondents’ perceptions about these countries.

Albania, Somalia, and Pakistan are majority Muslim countries, whereas Colombia is mainly Christian. In addition, these countries could reasonably face wildfire, drought, sea level rise, and floods, which we list as a separate dimension in our conjoint analysis.

Theoretically, literature suggests that recipient country characteristics can influence the support for aid in donor countries (De Coninck Reference De Coninck2020; Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020; Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, Bryan, Hanania and Pajor2020; Kiratli Reference Kiratli2020; Shehaj et al. Reference Shehaj, Shin and Inglehart2021). We suggest the donor country’s public might support adaptation packages for overseas countries that they consider to be in their in-group (Dion Reference Dion1973; Tajfel et al. Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Support for migration might be influenced by a similar logic. Research finds that aversion to cultural diversity might drive opposition to immigration (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007). We hypothesize that Dutch respondents might favor overseas adaptation support to countries with similar cultural characteristics as reflected in religion and geographical proximity.

Several studies find more generous redistribution (climate aid might be viewed in this manner) toward those who are perceived as the in-group (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Baker Reference Baker2015). Moreover, they might believe that in-group immigrants might find it easier to integrate into the Dutch society (an important issue in the contemporary immigration debates in the Netherlands) (Fleischmann and Dronkers Reference Fleischmann and Dronkers2010). Because Christianity is the largest (nominal) religion in the Netherlands, respondents might consider citizens from other Christian countries (Colombia) as an in-group and may be more willing to support climate adaptation assistance (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). We recognize that the majority of Dutch citizens do not identify with religion (CBS, 2023). Yet, with the rise of right-wing populism, the issue of religious identity of the immigrant population has become salient (in other countries such as France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden as well) (Shehaj et al. Reference Shehaj, Shin and Inglehart2021). This is why we have paid close attention to the issue of religion in selecting the countries for the conjoint experiment.

We further hypothesize that Dutch respondents’ support might be influenced by the geographical proximity of the continent in which the countries are located (Albania: Europe, Pakistan: Asia, Somalia: Africa, and Colombia: South America). This captures the perceptions respondents might hold about different continents (such as poverty and levels of development), and their perceived need and deservingness of adaptation assistance (Taormina and Messick Reference Taormina and Messick1983; Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020). Geographical proximity also has a cultural dimension (Evan et al. Reference Evan, Fišerová and Elgnerová2025) and therefore might also influence perceptions of an in-group (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). This could increase support for an adaptation package that includes both providing aid and/or accepting climate migrants (Phuong Reference Phuong2005).

Note that we are not testing if religion and geographical proximity drive support for aid or migration. Our dependent variable is support for the overseas policy package that has multiple dimensions, including the volume of aid, the number of migrations, as well as the name and characteristics of the country (which signals its geographical proximity and religion). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages for countries with shared religion (Colombia).

Hypothesis 3b: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages for countries in geographical proximity (Albania).

We expect higher support for countries that experience extreme weather events that require immediate help, such as floods and forest fires, over slow-onset problems such as sea level rise and droughts. The reason is that the impact of sudden events might be more likely to be seen as bad luck, rather than as something preventable (though we recognize that poor enforcement of zoning laws and land use planning contribute to both floods and forest fires) (Verkuyten et al. Reference Verkuyten, Mepham and Kros2018). Respondents might want to help communities that face ‘bad luck’ with both financial aid and immigration. Moreover, such assistance might be viewed as one-off support for fast-onset ‘bad luck’ events as opposed to chronic problems (Spilker et al. Reference Spilker, Nguyen, Koubi and Böhmelt2020).

Hypothesis 4: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages for countries facing fast-onset extreme weather events.

Governments often provide aid in the hope of improving bilateral relations and creating export opportunities. Arguably, immigration measures also signal such support. Sociotropic considerations might drive citizens’ support for adaptation assistance as well (Brakman and van Marrewijk Reference Brakman and Van Marrewijk1998; Kiratli Reference Kiratli2020;). Given the link between trade and aid (Lundsgaarde et al. Reference Lundsgaarde, Breunig and Prakash2010), climate aid could allow donor countries to find markets in aid recipient countries (Kiratli Reference Kiratli2020) and in the case of climate change, aid can support Dutch exports to the recipient country. Broadly, public support for any type of overseas policy assistance might favor countries that import from the Netherlands.

Hypothesis 5: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages for countries with high imports from the Netherlands.

Scholars note that perceptions of deservingness drive public support for foreign aid (Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020). We expect public support for policy packages to be higher when recipient countries have taken steps to ameliorate climate change, which is also a priority for the Netherlands (Verkuyten et al. Reference Verkuyten, Mepham and Kros2018). We, therefore, expect that countries that pledge to achieve zero emission targets sooner (2045 instead of 2050, 2060, or 2070), will be favored by Dutch respondents.

Hypothesis 6: Respondents favor adaptation policy packages for countries that pledge to be climate-neutral sooner.

Data and methods

We conducted a conjoint survey experiment among Dutch citizens (administered in Dutch) using market research company Cint (n = 1199) in January and February 2024. The lead author of this study is a native Dutch speaker. The survey was formulated in English, translated into Dutch, and then translated back into English for review by other co-authors. We obtained Human Subjects Approval from University of Washington, Seattle, and preregistered the study (https://osf.io/cmyh3/?view_only=836985be5cc046dba755245a3c953634). Our sample was representative of the Dutch population in terms of gender, age, income, and region (ten regions). More details on how the sample matches the population are provided in Appendix A.

As noted previously, our study draws on Uji et al.’s (Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021) work examining public support in Japan for aid and immigration in a single policy package and modifies it to suit Dutch politics. An advantage of conjoint experiments is that by asking about preferences for a policy with different dimensions, it simulates a more realistic scenario. Moreover, respondents can implicitly trade off among different dimensions (and among different values of the same dimension) without being observed, and this could reduce the social desirability bias (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). This means that respondents who see a link between any two dimensions (such as, but not limited to, aid and migration) could trade them off or view them as mutually reinforcing.

We included respondents who gave consent to participate. After obtaining respondents’ consent, we provided them with information on climate change and the historical responsibility of Global North countries, such as the Netherlands, for climate change. This was followed by an attention check question. Those failing the attention check were screened out. Subsequently, we presented respondents with 2 policy packages side-by-side with the same six dimensions and asked which one they favored (forced choice).

The challenge with online surveys is that respondents (who probably use smartphones to take these surveys) might not carefully read the questions, comprehend them, or complete the survey. In addition to the attention check question, we screened out respondents who did not finish the survey, moved their mouse too little (arguably to filter out bots), or exceeded our specific quotas (which were put in place to ensure that the sample was nationally representative). For more information on the quality of the sample, please see Appendix B.

The policy package had six dimensions, and every dimension could take 4-7 values, all randomly assigned. The dimensions are : (1) countries receiving assistance (Colombia, Pakistan, Albania, Somalia); (2) the type of natural disaster (flood, wildfire, drought, sea-level rise); (3) the proposed levels of financial aid in million Euros (0, 3, 10, 50, 100, 200); (4) the number of proposed climate migrants (0, 100, 300, 600, 1000, 1500, 2500); (5) the value of the country’s imports from the Netherlands in Euros (0, 500 million, 1 billion, 5 billion); and (6) the year in which the country pledges to be climate neutral (2045, 2050, 2060, 2070).

We note a change from the pre-registered survey: we replaced Nigeria with Somalia. The reason is that Nigeria, while a Muslim majority country, has a sizeable number of Christians as well (40% by some estimates). Because we wanted to ensure that the country name should convey the religion of its population, we decided that Somalia fits the criterion better (both countries are in Africa, so geographical proximity to the Netherlands is the same). Importantly, none of the hypotheses outlined in the pre-registration document were changed when we replaced Nigeria with Somalia.

We chose countries to ensure that every dimension (and value in each dimension) was plausible for all countries. For example, the dimension ‘type of natural disaster’ could take the value ‘sea level rise’. Thus, we made sure that all countries have a coastline. In wording the experiment, we used the language of ‘imagine’ the following scenarios, to avoid making any false claims. Overall, we have followed what we consider to be the best practices in conjoint-based research.

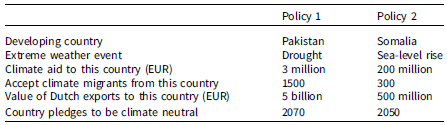

To minimize respondent fatigue, every respondent undertook the paired comparison of the policy packages 5 times only (although scholars note that respondents could undertake up to 30 paired comparisons without degrading the quality of their response, Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2018). With 1199 respondents (attentive and high quality), we worked with a sample of 11,990 observations (1199 respondents * 5 choice sets * 2 policy proposals). An example of paired comparison is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Example choice set

After the paired comparison, we asked a series of questions to assess respondents’ attitudes toward specific issues that might highlight the mechanisms behind their support for overseas aid or immigration. We asked them about their assessment of (1) the perceived difficulty of people from specific countries to integrate into the Netherlands, (2) the beneficial effects of climate aid, and (3) whether they are proud of the Dutch culture. In addition, we asked about their age, gender, income, education, religion, political ideology, children, charitable donations, and postal code.

Findings

We report our results in terms of marginal means. Several political science papers using conjoint experiments employ average marginal component effects (AMCEs) (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) which measure the degree to which a given value (say Colombia) of a conjoint dimension (say Country) increases or decreases respondents’ support for the dependent variable (overseas adaptation package in our case), relative to a baseline. This means if the baseline is changed (especially for non-binary variables), the results might change. As Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020: 214) note, ‘AMCEs are relative, not absolute, statements about preferences. As such, there is simply no predictable connection between subgroup causal effects and the levels of underlying subgroup preferences. Yet, analysts and their readers frequently interpret differences in conditional AMCEs as differences in underlying preferences’.

This is where marginal means (MMs) (Leeper et al. Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) come in. MMs allow us to estimate the level of favorability toward the policy package with a dimension value of x, irrespective of other dimension values (Leeper et al. Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). Thus, the MM could be interpreted in terms of frequency, where the MM outcome of zero indicates that respondents never select the adaptation package with this given value of the specific dimension, whereas the MM outcome of 1 indicates that respondents always select the package when this dimension takes this specific value. MM with 0.5 value becomes the threshold: values (with their confidence intervals) falling below (above) this threshold suggests the lower (higher) likelihood of respondents’ supporting the package when the dimension takes this specific value.

General results

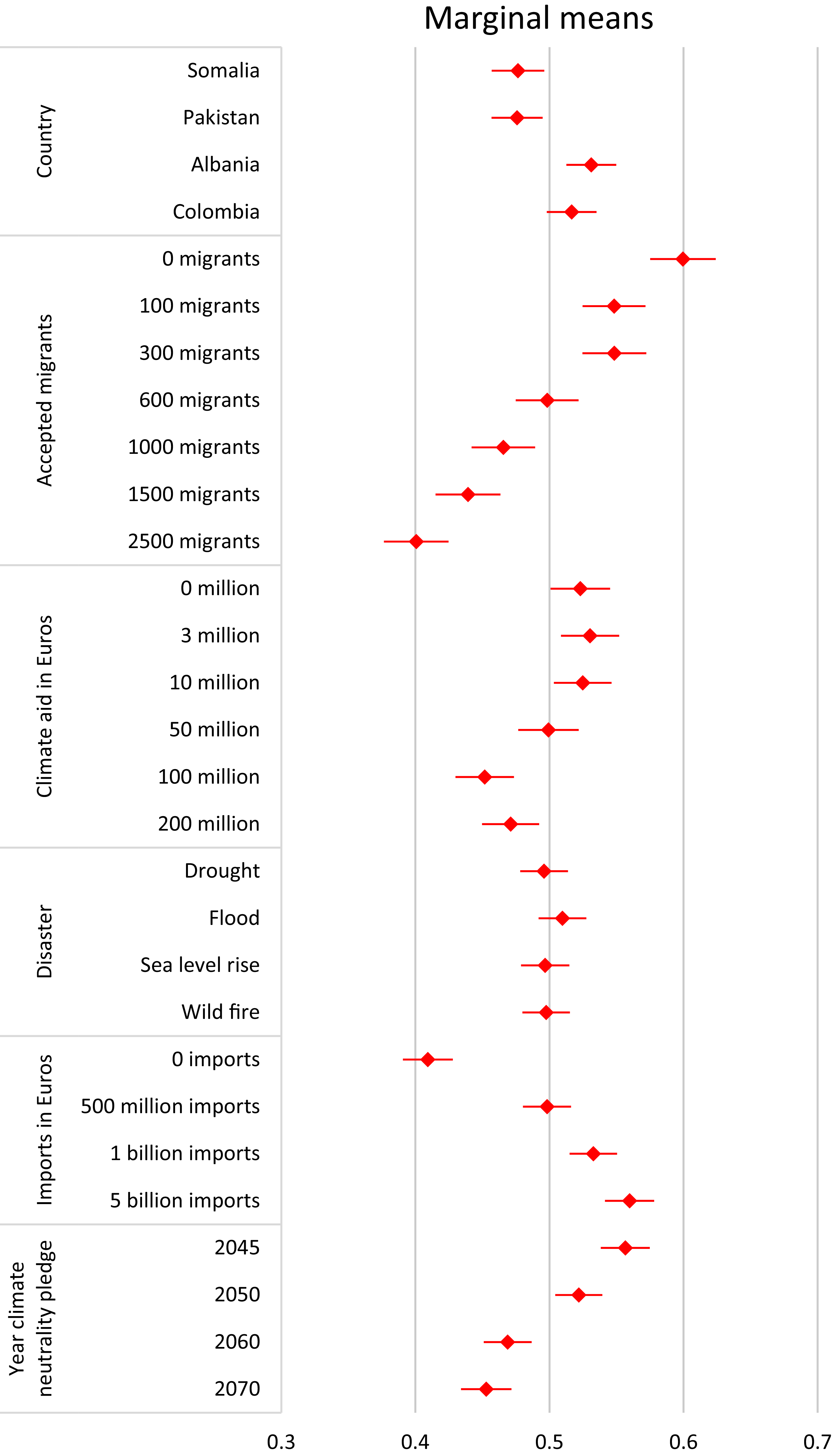

In Figure 1, we report the marginal means at 95% confidence interval for every value of a policy package dimension.

Figure 1. Support for policy package. Note: lines indicate 95% confidence interval.

We find that respondents favor lower levels of climate aid. Climate aid of €10 million and below increases support for the policy package, and aid of €100 million and above decreases policy support (H1 is supported). Respondents favor lower numbers of climate migrants. Support for the policy package increases only when the number of migrants is below 600. When migration numbers rise beyond 600, support for the policy decreases (H2 is supported).

Does policy support reflect an in-group bias? We recognize that religion and geographical proximity are two (of the many) dimensions of perceived cultural similarity, a driver of in-group versus out-group bias. We expected Dutch respondents to support overseas assistance to European countries and countries with co-religionists (while recognizing that most Dutch tend to be non-religious). We find that support for the policy package increases when the package is aimed at Albania, a geographically proximate country. Yet it is also puzzling because Albania is a Muslim majority country. Thus, future research should explore how respondents unpack cultural signals (which might motivate in-group and out-group dynamics) and the extent to which one cultural dimension might dominate others.

Similarly, we find that (borderline) support (at 8% level) for the policy package increases when the package is aimed at Colombia, a geographically distant but religiously similar country. Though this result is borderline significant, it again suggests that culture is a multidimensional concept, and different respondents (in thinking about in-group versus out-group) might focus on a specific dimension only.

Spilker et al. (Reference Spilker, Nguyen, Koubi and Böhmelt2020) argue that respondents are sympathetic toward policy packages supporting victims of abrupt events as opposed to the slowly occurring ones. Assuming floods and forest fires are abrupt onset events while droughts and sea level rise are slow onset events, we expected support for a policy package to diminish with drought and sea level rise but increase with floods and forest fires. However, in our experiment, the type of natural disaster does not influence respondents’ policy support. (H4 is not supported).

In terms of economic and political linkages, the respondents favor countries that import from the Netherlands. Low levels of imports (below Euro 500 million) decrease support, but imports above Euro 500 million increase support (H5 is supported).

Finally, Dutch respondents reward countries that contribute to the global public good of climate mitigation, a policy priority for the Netherlands. We find that policy support is higher for countries that pledge to be climate-neutral sooner (by 2045 and 2050), but lower for countries that pledge to be climate-neutral by 2060 or 2070 (H6 is supported).

In the pre-registration document, we had proposed embedding the conjoint with a survey experiment where we benchmark the Netherlands’ aid and immigration policies with (1) peer countries of the Global North and (2) its previous record. We find that benchmarking does not alter the findings regarding support for the overseas adaptation package. These results are presented in the online Appendix. We also examined whether individual-level characteristics might impact respondents’ support for policy packages. We focus on the following: gender, age, and political orientation. We present these results in the online Appendix as well.

Conclusion

Our study assessed support for overseas adaptation policies among Dutch respondents with a policy package with six dimensions: different levels of (1) climate aid and (2) climate immigrants, directed to (3) countries which vary in characteristics such as their religion, continent in which they are located, (4) trade with the Netherlands, (5) commitment to net zero emission targets, and (6) experiencing different types of natural disasters. The broad finding is that support for the adaptation package decreased with high levels of either aid or immigration. Moreover, the Dutch public tends to support adaptation assistance for countries in geographical proximity (Albania), with shared religion (Colombia-borderline significance), with economic ties, and that show commitment to climate mitigation.

Given the opposition to high levels of aid or immigration raises important questions for climate adaptation efforts at the global level. At the 2009 Copenhagen Conference of the Parties meeting, Global North countries pledged to provide $100 billion per annum in climate aid by 2020. A recent report by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) finds that this target was finally met in 2022 – although the quality of aid (about two-thirds is in the form of loans which need to be repaid) and the conditionalities donors attached to them (such as obligations to purchase materials from domestic firms) raise questions about the seriousness of Global North countries’ commitment to overseas adaptation (OECD 2023). The report suggests that about 25% of climate aid is devoted to adaptation, an inadequate amount given the scale of the challenge developing countries face in adapting to climate change.

Building support for aid (in situ adaptation) and migration (ex situ adaptation) as two aspects of overseas adaptation will probably need a new narrative in the Netherlands, beyond the issue of the historical responsibility of the Global North in contributing to the climate crisis. One strategy might be to link them with issues that the Dutch public favors. For example, we find that the Dutch public supports adaptation policy packages to countries that pledge to be climate-neutral sooner, a climate mitigation strategy. Thus, respondents are willing to support adaptation in countries that are also taking active steps toward mitigation and joining hands with the Netherlands in addressing the climate crisis through decarbonization. Of course, this might create inequities because some countries can decarbonize at lower costs than others. Nevertheless, the narrative that the Dutch government supports climate mitigation leaders in the Global South countries (who are not free riding on the efforts of the Global North) could be an important step to build domestic support for overseas adaptation.

Our paper raises important questions about aid targeting. We find some sort of in-group bias: public support is influenced by geographical proximity and religious similarity with the Netherlands. Yet, it is not clear how respondents prioritized these two dimensions, both signaling cultural proximity: Dutch support adaptation packages for a geographically proximate but religiously dissimilar country (Albania) as well as a religiously similar but geographically distant country (Colombia). This suggests that the issue of cultural similarity needs to be unpacked along its multiple dimensions to study what specific dimensions trigger the in-group bias and how this might vary across individuals.

Similarly, we find that the Dutch audience cares about economic ties with the Netherlands. Targeting aid to countries with trade ties could be morally problematic because, ideally, climate adaptation support should be determined by the needs of overseas countries. While not the ideal way to allocate the adaptation package, this sort of targeting approach could become an initial step to place overseas adaptation packages in routine policy discussions.

We have noted the literature linking migration and foreign aid (e.g., Berthélemy et al Reference Berthélemy, Beuran and Maurel2009, Dreher et al Reference Dreher, Fuchs and Langlotz2019, Bermeo and Leblang Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015 and Gamso and Yuldashev Reference Gamso and Yuldashev2018). Yet, there is less work on how this aid-migration link might shape public support in donor countries for overseas assistance, especially in the context of climate policy. Building on Uji et al. (Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021) and Andonova et al., (Reference Andonova, Zucca, Montfort, Dolšak and Prakash2025) we move this discussion in a novel direction by including aid and migration as a part of an overseas adaptation package. This allows respondents to implicitly trade off one against the other or view them as mutually reinforcing or independent elements of the adaptation package. Future work could explicitly examine how respondents might trade off aid against migration, as opposed to treating them as two of the several dimensions of a climate policy package.

We recognize the concerns about external validity because the extent to which the Netherlands is representative of Global North countries, or even European countries, is not clear, given the high political support for far-right parties (although these parties seemed to have made electoral gains in several European countries in local, national, and European Union Parliamentary elections). We could compare our findings with Uji et al.’s (Reference Uji, Song, Dolšak and Prakash2021) study of the Japanese public. Both studies report that respondents disfavor higher levels of migration. This is a revealing finding because these countries have vastly different experiences with immigration: 15% of the population in the Netherlands, but less than 3% in Japan. While the anti-immigration sentiment in these countries is motivated by different factors, these papers reveal the political challenges of using climate migration as an overseas adaptation policy. Arguably, this might reflect a worldwide trend of domestic opposition to immigration, irrespective of what triggers individuals to migrate in the first place. Indeed, immigration is an important item on the agenda of the recently elected Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi (EFE Reference EFE2025). Might adaptation aid, which has emerged as an important discussion point in the 30th Conference of the Parties meeting in Brazil, reveal different political dynamics? While Dutch respondents disfavor higher levels of aid, Japanese respondents are indifferent. Thus, overseas aid as an adaptation tool might be politically feasible, at least in a subset of Global North countries. Whether this indifference holds for other countries too and what drives this in Japan needs further exploration. Arguably, disaster-prone countries such as Japan might face less political polarization on overseas aid issues compared to those facing fewer disasters, like the Netherlands.

Both the Japanese and the Netherlands studies show that support for adaptation hinges on relational factors, such as bilateral trade, and support for the donor country in international forums. In addition, being a good global citizen also seems to increase public support. While both studies confirm an in-group bias with respect to support for adaptation packages, future work could explore the extent to which in-group bias can be moderated by aforementioned drivers like perceived need, global citizenship, and beneficial bilateral economic ties.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773926100319.

Data availability statement

The survey was pre-registered with OSF: https://osf.io/cmyh3/overview?view_only=556fdf7424c94f2baa850dfb6fc08e62. The replication data is posted on Harvard dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/OELHKG.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the London School of Economics and Political Science and helpful advice from Cameron Mulder (University of Oregon). All errors remain ours.

Funding statement

Ellen Holtmaat gratefully acknowledges funding from the London School of Economics and Political Science. The funder played no role in the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Ethical standard

We obtained Human Subjects Approval from the University of Washington. Approval number/ID: MOD00013540.

All participants were 18 years or older and gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Appendix A. Representative sample

Gender

This is the gender distribution in the Netherlands (source: Cint, Dutch Central Statistics Office CBS, 2020):

We approximated this in the sample with:

Age

The age distribution in the Netherlands is (source: Cint, Dutch Central Statistics Office CBS, 2020):

We approximated this in our sample with:

Income

The income distribution in the Netherlands is as follows (source: Cint, Dutch Central Statistics Office CBS, 2020):

We approximated this in our sample with:

Region

Regional distribution is (source: Dutch Central Statistics Office CBS, 2020):

We approximated that with:

Appendix B. Quality control of the sample

We included respondents who gave consent to participate. The challenge with online surveys is that respondents (who probably use smartphones to take these surveys) might not carefully read the questions or comprehend them or complete the survey. To maintain the quality of the sample, we screened out respondents who: (1) failed the attention check question, (2) did not finish the survey, (3) moved their mouse too little (arguably to filter out bots), and (4) exceeded our specific quotas (which were put in place to ensure that the sample was nationally representative).