1. Introduction

The Lorenz curve is a foundational graphical tool in the study of income distributions, depicting the cumulative share of income received by the bottom ![]() $p$ proportion of the population. A central concept derived from this framework is Lorenz dominance (LD), wherein one distribution is said to dominate another if its Lorenz curve lies entirely above the other’s. This relationship, denoted

$p$ proportion of the population. A central concept derived from this framework is Lorenz dominance (LD), wherein one distribution is said to dominate another if its Lorenz curve lies entirely above the other’s. This relationship, denoted ![]() $F \succ_{LD} G$, implies unanimous agreement among all inequality-averse social welfare functionals, as demonstrated by Atkinson [Reference Atkinson2]. Foster and Shorrocks [Reference Foster and Shorrocks13] further showed that LD supports consistent poverty rankings across a wide class of poverty indices sensitive to distributional changes.

$F \succ_{LD} G$, implies unanimous agreement among all inequality-averse social welfare functionals, as demonstrated by Atkinson [Reference Atkinson2]. Foster and Shorrocks [Reference Foster and Shorrocks13] further showed that LD supports consistent poverty rankings across a wide class of poverty indices sensitive to distributional changes.

Despite its theoretical elegance, strict LD is rarely observed in empirical settings. Empirical Lorenz curves often intersect, rendering binary dominance assessments inconclusive. This empirical reality has motivated the development of statistical procedures to test for LD. Bishop et al. [Reference Bishop, Formby and Smith6, Reference Bishop, Formby and Smith7] initiated this literature with quantile-based inference, which was subsequently refined into pointwise dominance tests by Dardanoni and Forcina [Reference Dardanoni and Forcina9] and Davidson and Duclos [Reference Davidson and Duclos10]. However, Barrett and Donald [Reference Barrett and Donald3] identified size distortions in these methods, leading Barrett et al. [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4] to propose consistent nonparametric approaches grounded in empirical process theory, akin to those employed in stochastic dominance testing. More recently, Sun and Beare [Reference Sun and Beare17] introduced a boundary-corrected bootstrap method that enhances power while maintaining appropriate size.

Alongside inferential advancements, a complementary literature has explored partial and almost dominance frameworks to capture deviations from strict LD. Fishburn and Willig [Reference Fishburn and Willig12] provided formal foundations for partial orderings grounded in transfer principles and social preferences. Duclos et al. [Reference Duclos, Sahn and Younger11] extended these concepts to multidimensional poverty comparisons. Zheng [Reference Zheng20] introduced a formal metric for quantifying almost LD, based on a normalized geometric index denoted as ![]() $\epsilon$. This index is defined as the ratio of the smaller area enclosed between two intersecting Lorenz curves to the total area under the reference Lorenz curve. The measure provides an interpretable gauge of the extent to which one distribution nearly dominates another, even when strict LD does not hold. Chang et al. [Reference Chang, Cheng and Liou8] develop a likelihood-ratio test for LD by framing strict dominance and intersecting curves as nested models. Their method combines maximum likelihood estimation with problem-specific test statistics, but the computational burden increases sharply with each additional crossing point, requiring the use of advanced optimization and simulation techniques.

$\epsilon$. This index is defined as the ratio of the smaller area enclosed between two intersecting Lorenz curves to the total area under the reference Lorenz curve. The measure provides an interpretable gauge of the extent to which one distribution nearly dominates another, even when strict LD does not hold. Chang et al. [Reference Chang, Cheng and Liou8] develop a likelihood-ratio test for LD by framing strict dominance and intersecting curves as nested models. Their method combines maximum likelihood estimation with problem-specific test statistics, but the computational burden increases sharply with each additional crossing point, requiring the use of advanced optimization and simulation techniques.

In this paper, we propose the Lorenz dominance index (LDI), a continuous, population-based metric that quantifies the extent to which one distribution fails to Lorenz dominate another. Unlike existing area-based measures of almost dominance, the LDI focuses on the proportion of the population for which one Lorenz curve lies below the other, offering an interpretable and statistically tractable measure of partial dominance.

A clear distinction must be drawn between area-based inequality measures and dominance-based measures such as the LDI. Standard indices like the Gini coefficient quantify the magnitude of inequality but provide no information about which population segments are relatively better or worse off when comparing two distributions. LD, by contrast, offers this segment-specific insight but does not indicate how large the underlying inequality differences are; strict dominance may arise even when conventional inequality indices differ only marginally. The LDI is therefore introduced to summarize the breadth of (near) LD—that is, the proportion of the population for which one distribution yields relatively better outcomes. Crucially, the LDI does not measure the degree of inequality, and its values should not be interpreted as reflecting large or small inequality differences. Instead, it is a descriptive, non-normative complement to standard inequality indices, highlighting which parts of the population benefit more under one distribution while avoiding conflation between dominance breadth and inequality magnitude.

To support its use in empirical applications, we develop a full statistical framework for the LDI. To support its use in applied research, We derive its asymptotic distribution and establish asymptotic normality under mild regularity conditions, thereby enabling valid statistical inference. To aid practical implementation, we also design a nonparametric bootstrap procedure for constructing confidence intervals and testing hypotheses related to partial LD. Extensive simulation studies demonstrate the estimator’s robustness and efficiency across diverse data-generating processes. Finally, we apply the LDI to Chinese household income data, illustrating its empirical relevance and utility in real-world distributional analysis.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the estimation procedure for the LDI and outlines its asymptotic properties. Section 3 introduces the bootstrap methodology for inference. Section 4 reports simulation results evaluating the performance of the estimator. Section 5 provides an empirical analysis based on household income data from China. Proofs of the main theoretical results are provided in the Appendix.

2. Lorenz dominance index: estimation and statistical properties

This section introduces the LDI as a population-based measure for comparing income distributions and assessing inequality dominance. We begin by defining the LDI and discussing its interpretability and relevance in distributional analysis. We then present an empirical estimation framework suitable for practical implementation, followed by a detailed examination of the estimator’s asymptotic properties under standard regularity conditions. Together, these components provide a rigorous foundation for statistical inference using the LDI in applied settings.

2.1. Definition and interpretation of the Lorenz dominance index

Let ![]() $F_1:[0, \infty) \to [0, 1]$ and

$F_1:[0, \infty) \to [0, 1]$ and ![]() $F_2:[0, \infty) \to [0, 1]$ denote the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of two income (or wealth) distributions. We impose the following regularity conditions.

$F_2:[0, \infty) \to [0, 1]$ denote the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of two income (or wealth) distributions. We impose the following regularity conditions.

Assumption 2.1. For each ![]() $j \in \{1,2\}$,

$j \in \{1,2\}$, ![]() $F_j(0)=0$,

$F_j(0)=0$, ![]() $F_j$ is continuously differentiable with strictly positive density

$F_j$ is continuously differentiable with strictly positive density ![]() $f_j$ on its support, and possesses a finite absolute moment of order

$f_j$ on its support, and possesses a finite absolute moment of order ![]() $(2+\epsilon)$ for some

$(2+\epsilon)$ for some ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$.

$\epsilon \gt 0$.

Given Assumption 2.1, we define the Lorenz curves ![]() $L_j$ for

$L_j$ for ![]() $j=1,2$, as

$j=1,2$, as

\begin{equation*}

L_j(p) = \frac{1}{\mu_j}\int_{0}^{p} Q_j(t) \, {\rm dt} \quad \text{for } p \in [0,1],

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

L_j(p) = \frac{1}{\mu_j}\int_{0}^{p} Q_j(t) \, {\rm dt} \quad \text{for } p \in [0,1],

\end{equation*} where ![]() $Q_j(p) = \inf \{x: F_j(x) \geq p,\; x\in [0,\infty)\}$ represents the quantile function, and

$Q_j(p) = \inf \{x: F_j(x) \geq p,\; x\in [0,\infty)\}$ represents the quantile function, and  $\mu_j=\int_0^{\infty} t f_j(t) \, {\rm dt}$ denotes the mean of distribution

$\mu_j=\int_0^{\infty} t f_j(t) \, {\rm dt}$ denotes the mean of distribution ![]() $F_j$. The condition for the LD of distribution

$F_j$. The condition for the LD of distribution ![]() $F_1$ over

$F_1$ over ![]() $F_2$ is satisfied if and only if

$F_2$ is satisfied if and only if ![]() $L_1(p) \geq L_2(p)$ for all

$L_1(p) \geq L_2(p)$ for all ![]() $p \in [0,1]$, where the Lorenz curve

$p \in [0,1]$, where the Lorenz curve ![]() $L(p)$ represents the cumulative share of total income earned by the bottom

$L(p)$ represents the cumulative share of total income earned by the bottom ![]() $p$ proportion of the population. In this framework, if

$p$ proportion of the population. In this framework, if ![]() $L_1(p) \gt L_2(p)$ for some

$L_1(p) \gt L_2(p)$ for some ![]() $p$, it implies that the poorest

$p$, it implies that the poorest ![]() $p$ fraction of population 1 holds a larger share of total income than the corresponding fraction in population 2, indicating relatively greater equality in

$p$ fraction of population 1 holds a larger share of total income than the corresponding fraction in population 2, indicating relatively greater equality in ![]() $F_1$ at that quantile.

$F_1$ at that quantile.

In many empirical applications, Lorenz curves intersect, indicating that neither distribution fully dominates the other. In such cases, the binary LD criterion is inconclusive, as it cannot establish which distribution exhibits greater inequality. To address this limitation, we propose a continuous measure known as the LDI, which quantifies the extent to which the LD condition is violated. This measure enables more nuanced and informative comparisons between income distributions.

The LDI is formally defined as:

where ![]() $\mu$ denotes the Lebesgue measure on

$\mu$ denotes the Lebesgue measure on ![]() $(0,1)$. That is,

$(0,1)$. That is, ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ measures the proportion of the population over which the Lorenz curve of

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ measures the proportion of the population over which the Lorenz curve of ![]() $F_1$ fails to Lorenz dominate

$F_1$ fails to Lorenz dominate ![]() $F_2$.

$F_2$.

The LDI has several desirable properties. It satisfies the bounds ![]() $0 \le \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \le 1$, where:

$0 \le \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \le 1$, where:

•

$ \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0 $ implies LD of

$ \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0 $ implies LD of  $ F_1 $ over

$ F_1 $ over  $ F_2 $,

$ F_2 $,•

$ \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 1 $ implies LD in the opposite direction, i.e., of

$ \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 1 $ implies LD in the opposite direction, i.e., of  $ F_2 $ over

$ F_2 $ over  $ F_1 $,

$ F_1 $,•

$ \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0.5 $ implies that the two distributions are symmetric with respect to LD, indicating no clear dominance by either in terms of inequality.

$ \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0.5 $ implies that the two distributions are symmetric with respect to LD, indicating no clear dominance by either in terms of inequality.

Moreover, the LDI satisfies a natural symmetry property:

This symmetry allows for direct comparison: when ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2) \lt \Gamma(F_2, F_1) $, the Lorenz curve of

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2) \lt \Gamma(F_2, F_1) $, the Lorenz curve of ![]() $F_1$ lies below that of

$F_1$ lies below that of ![]() $F_2$ over a smaller proportion of the population, indicating that

$F_2$ over a smaller proportion of the population, indicating that ![]() $F_1$ exhibits less inequality relative to

$F_1$ exhibits less inequality relative to ![]() $F_2$. Specifically, values of

$F_2$. Specifically, values of ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ below 0.5 suggest that

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ below 0.5 suggest that ![]() $F_1$ is less unequal compared to

$F_1$ is less unequal compared to ![]() $F_2$, while values above 0.5 suggest the opposite.

$F_2$, while values above 0.5 suggest the opposite.

In contrast to the ![]() $\epsilon$-index introduced by Zheng [Reference Zheng20], which quantifies inequality deviation by measuring the area between intersecting Lorenz curves, the LDI offers a population-based alternative. Rather than focusing on the intensity of deviation, the LDI measures the proportion of the population for which one distribution’s Lorenz curve lies below another’s, highlighting the breadth of deviation from LD.

$\epsilon$-index introduced by Zheng [Reference Zheng20], which quantifies inequality deviation by measuring the area between intersecting Lorenz curves, the LDI offers a population-based alternative. Rather than focusing on the intensity of deviation, the LDI measures the proportion of the population for which one distribution’s Lorenz curve lies below another’s, highlighting the breadth of deviation from LD.

This perspective aligns more closely with how inequality affects people across a society. Intensity-based measures like the ![]() $\epsilon$-index may emphasize sharp deviations in narrow segments of the population, potentially overlooking broader, more pervasive differences. In contrast, the LDI captures how many people are impacted by inequality, making it more intuitive and relevant for policy design and evaluation

$\epsilon$-index may emphasize sharp deviations in narrow segments of the population, potentially overlooking broader, more pervasive differences. In contrast, the LDI captures how many people are impacted by inequality, making it more intuitive and relevant for policy design and evaluation

2.2. Illustrative example of partial Lorenz dominance

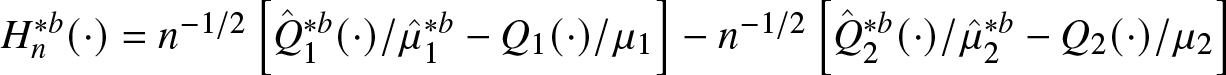

To illustrate the type of situations where the LDI is most informative, we construct two plausible income distributions for populations A and B using a standard spliced model. In this model, the bottom 90% follows a Lognormal distribution and the top 10% follows a Pareto tail—a widely used approach to approximate real-world income distributions. Population A is specified by

while Population B has a more dispersed Lognormal body and a lighter Pareto tail:

with ![]() $\mu_B = 0.54$ calibrated so that both distributions share the same mean income (

$\mu_B = 0.54$ calibrated so that both distributions share the same mean income (![]() $\approx 4.05$). These parameter choices reflect realistic patterns in which middle-class dispersion and top-income behavior differ across populations. The resulting Lorenz curves intersect at

$\approx 4.05$). These parameter choices reflect realistic patterns in which middle-class dispersion and top-income behavior differ across populations. The resulting Lorenz curves intersect at ![]() $p = 0.77$ (Figure 1). Although the Gini coefficients are nearly identical (

$p = 0.77$ (Figure 1). Although the Gini coefficients are nearly identical (![]() $\approx 0.634$), the underlying distributional differences are substantial. Area-based measures, which weight the magnitude of vertical gaps between curves, may favor Population B because the area where

$\approx 0.634$), the underlying distributional differences are substantial. Area-based measures, which weight the magnitude of vertical gaps between curves, may favor Population B because the area where ![]() $L_B \gt L_A$ slightly exceeds the reverse:

$L_B \gt L_A$ slightly exceeds the reverse:

\begin{equation*}

\int_0^p [L_A(q) \gt L_B(q)]\, dq \approx 0.0105, \quad

\int_p^1 [L_B(q) \gt L_A(q)]\, dq \approx 0.0156.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\int_0^p [L_A(q) \gt L_B(q)]\, dq \approx 0.0105, \quad

\int_p^1 [L_B(q) \gt L_A(q)]\, dq \approx 0.0156.

\end{equation*}

Figure 1. The Lorenz curves of the populations A and B, represented by ![]() $L_1$ (orange curve) and

$L_1$ (orange curve) and ![]() $L_2$ (blue curve), respectively.

$L_2$ (blue curve), respectively.

This occurs because differences in the top 23% dominate the integrated area, potentially obscuring patterns that affect the majority of the population. The LDI, in contrast, focuses on the breadth of LD by measuring the proportion of the population for which one Lorenz curve lies above the other:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\Gamma(F_A, F_B) &= \mu\{q : L_A(q) \lt L_B(q)\} = 1-p \approx 0.23, \\

\Gamma(F_B, F_A) &= \mu\{q : L_B(q) \lt L_A(q)\} = p \approx 0.77.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\Gamma(F_A, F_B) &= \mu\{q : L_A(q) \lt L_B(q)\} = 1-p \approx 0.23, \\

\Gamma(F_B, F_A) &= \mu\{q : L_B(q) \lt L_A(q)\} = p \approx 0.77.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}From this perspective, population A clearly dominates for most of the population. This example highlights the policy-relevant advantage of LDI: it captures broad population-level patterns, complementing area-based measures, which may overemphasize differences in small segments such as the top tail.

2.3. Empirical estimation framework

We construct empirical estimators of the LDI using independent random samples from the distributions ![]() $F_1$ and

$F_1$ and ![]() $F_2$. Let

$F_2$. Let  $\{X_i^j\}_{i=1}^{n_j} \stackrel{\text{i.i.d.}}{\sim} F_j$ for

$\{X_i^j\}_{i=1}^{n_j} \stackrel{\text{i.i.d.}}{\sim} F_j$ for ![]() $j=1,2$ denote two independent samples. Based on these, we define the empirical distribution function, sample mean, and empirical quantile function for each sample as follows:

$j=1,2$ denote two independent samples. Based on these, we define the empirical distribution function, sample mean, and empirical quantile function for each sample as follows:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\hat{F}_j(x) &= \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^j \leq x\}}, \\

\hat{\mu}_j &= \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} X_i^j, \\

\hat{Q}_j(p) &= \inf\left\{x \geq 0 : \hat{F}_j(x) \geq p\right\}, \quad p \in [0,1].

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\hat{F}_j(x) &= \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^j \leq x\}}, \\

\hat{\mu}_j &= \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} X_i^j, \\

\hat{Q}_j(p) &= \inf\left\{x \geq 0 : \hat{F}_j(x) \geq p\right\}, \quad p \in [0,1].

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}Subsequently, the Lorenz curve estimator for each distribution is given by:

\begin{equation*}

\hat{L}_j(p) = \hat{\mu}_j^{-1}\int_0^p \hat{Q}_j(t)\mathrm{d}t,\quad j=1,2,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\hat{L}_j(p) = \hat{\mu}_j^{-1}\int_0^p \hat{Q}_j(t)\mathrm{d}t,\quad j=1,2,

\end{equation*}which, in turn, defines the estimator of the LDI as:

\begin{equation*}

\hat{\Gamma} = \Gamma(\hat{F}_1,\hat{F}_2) = \mu\left\{p \in (0,1) : \hat{L}_1(p) \lt \hat{L}_2(p)\right\},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\hat{\Gamma} = \Gamma(\hat{F}_1,\hat{F}_2) = \mu\left\{p \in (0,1) : \hat{L}_1(p) \lt \hat{L}_2(p)\right\},

\end{equation*} where ![]() $\mu$ denotes the Lebesgue measure on the unit interval. This index represents the proportion of the population for which the empirical Lorenz curve of

$\mu$ denotes the Lebesgue measure on the unit interval. This index represents the proportion of the population for which the empirical Lorenz curve of ![]() $F_1$ lies below that of

$F_1$ lies below that of ![]() $F_2$, thereby reflecting the extent of inequality dominance.

$F_2$, thereby reflecting the extent of inequality dominance.

For practical computation, we approximate ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ via numerical integration using a discretization of the unit interval. Let

$\hat{\Gamma}$ via numerical integration using a discretization of the unit interval. Let  $\mathcal{T}_M = \{t_i\}_{i=1}^M$ be a grid of

$\mathcal{T}_M = \{t_i\}_{i=1}^M$ be a grid of ![]() $M$ equally spaced points in

$M$ equally spaced points in ![]() $(0,1)$, with

$(0,1)$, with ![]() $t_i = i/(M+1)$ and typically

$t_i = i/(M+1)$ and typically ![]() $M=1000$. Then, the empirical approximation becomes:

$M=1000$. Then, the empirical approximation becomes:

\begin{equation*}

\hat{\Gamma} = (M+1)^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^M \mathbb{I}_{\{\hat{L}_1(t_i) \lt \hat{L}_2(t_i)\}},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\hat{\Gamma} = (M+1)^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^M \mathbb{I}_{\{\hat{L}_1(t_i) \lt \hat{L}_2(t_i)\}},

\end{equation*}which estimates the proportion of grid points where the Lorenz curve of sample 1 lies below that of sample 2. This proportion serves as a consistent estimator of the population-based LDI and forms the basis for subsequent asymptotic analysis.

2.4. Asymptotic properties of the estimator

This subsection examines the asymptotic properties of the proposed estimator under additional regularity conditions.

Assumption 2.2. Let ![]() $n=n_1n_2/(n_1+n_2)$. As

$n=n_1n_2/(n_1+n_2)$. As ![]() $n_1, n_2 \to \infty$, we have

$n_1, n_2 \to \infty$, we have ![]() $n \to \infty$ and the proportion

$n \to \infty$ and the proportion  $\frac{n_1}{n_1 + n_2} \to \lambda$ for some constant

$\frac{n_1}{n_1 + n_2} \to \lambda$ for some constant ![]() $\lambda \in (0, 1)$.

$\lambda \in (0, 1)$.

Assumption 2.3. There exists a finite number of ![]() $p$ values such that

$p$ values such that ![]() $L_1(p) = L_2(p)$ but

$L_1(p) = L_2(p)$ but ![]() $Q_1(p)/\mu_1 \not= Q_2(p)/\mu_2$. In addition, suppose that

$Q_1(p)/\mu_1 \not= Q_2(p)/\mu_2$. In addition, suppose that

\begin{equation}

\lim\limits_{p\rightarrow0} \frac{Q_1(p)\mu_2}{Q_2(p)\mu_1} \not=1,~~ \lim\limits_{p\rightarrow1} \frac{Q_1(p)\mu_2}{Q_2(p)\mu_1} \not=1.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\lim\limits_{p\rightarrow0} \frac{Q_1(p)\mu_2}{Q_2(p)\mu_1} \not=1,~~ \lim\limits_{p\rightarrow1} \frac{Q_1(p)\mu_2}{Q_2(p)\mu_1} \not=1.

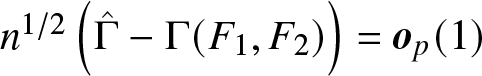

\end{equation}Theorem 2.4 Under Assumptions 2.1–2.3, as ![]() $n \to \infty$,

$n \to \infty$,

\begin{equation*}

\sqrt{n} \left( \hat{\Gamma} - \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \right) \xrightarrow{d} \text{N}(0, \sigma^2)

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sqrt{n} \left( \hat{\Gamma} - \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \right) \xrightarrow{d} \text{N}(0, \sigma^2)

\end{equation*} for some asymptotic variance ![]() $\sigma^2$. In particular:

$\sigma^2$. In particular:

(i) If ![]() $L_1$ and

$L_1$ and ![]() $L_2$ have no crossing point, then

$L_2$ have no crossing point, then  $\hat{\Gamma}-\Gamma(F_1,F_2) = \boldsymbol{o}_p(n^{-1/2}), i.e., \sigma^2 = 0$.

$\hat{\Gamma}-\Gamma(F_1,F_2) = \boldsymbol{o}_p(n^{-1/2}), i.e., \sigma^2 = 0$.

(ii) If ![]() $L_1$ and

$L_1$ and ![]() $L_2$ have exactly one crossing point at

$L_2$ have exactly one crossing point at ![]() $p=p_1^\ast$, then

$p=p_1^\ast$, then

\begin{equation}

\sigma^2=\tau^2(p^\ast_1)\Big[\frac{\lambda p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_1^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_1^\ast))\mu_2^2}\Big];

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sigma^2=\tau^2(p^\ast_1)\Big[\frac{\lambda p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_1^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_1^\ast))\mu_2^2}\Big];

\end{equation} (iii) If ![]() $L_1$ and

$L_1$ and ![]() $L_2$ have exactly two crossing points

$L_2$ have exactly two crossing points ![]() $p_1^\ast \lt p_2^\ast$, then

$p_1^\ast \lt p_2^\ast$, then

\begin{equation*}\sigma^2=\tau^2(p^\ast_1)\left[\frac{\lambda p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_1^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_1^\ast))\mu_2^2}\right]\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sigma^2=\tau^2(p^\ast_1)\left[\frac{\lambda p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_1^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_1^\ast(1-p_1^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_1^\ast))\mu_2^2}\right]\end{equation*} \begin{equation*}+\tau^2(p^\ast_2)\left[\frac{\lambda p_2^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_2^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_2^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_2^\ast))\mu_2^2}\right]\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}+\tau^2(p^\ast_2)\left[\frac{\lambda p_2^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_2^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_2^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_2^\ast))\mu_2^2}\right]\end{equation*} \begin{equation}

-2\tau(p^\ast_1)\tau(p^\ast_2)\left[\frac{\lambda p_1^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_1^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_1^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_1^\ast))\mu_2^2}\right],

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

-2\tau(p^\ast_1)\tau(p^\ast_2)\left[\frac{\lambda p_1^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_1(Q_1(p_1^\ast))\mu_1^2}+\frac{(1-\lambda) p_1^\ast(1-p_2^\ast)}{f^2_2(Q_2(p_1^\ast))\mu_2^2}\right],

\end{equation} where ![]() $\tau(p)=f_1(Q_1(p))f_2(Q_2(p))/\left[\mu_1f_2(Q_2(p))-\mu_2f_1(Q_1(p))\right]$.

$\tau(p)=f_1(Q_1(p))f_2(Q_2(p))/\left[\mu_1f_2(Q_2(p))-\mu_2f_1(Q_1(p))\right]$.

3. Bootstrap-based inference

3.1. Asymptotic properties and bootstrap validity

A rigorous asymptotic analysis of point estimators requires careful evaluation of estimation error, particularly to support the construction of confidence intervals and the implementation of hypothesis testing procedures. While Theorem 2.4 provides the asymptotic variance of the estimator, it depends on unknown features of the underlying population distributions, limiting its direct applicability. To address this issue, we advocate the use of bootstrap methods, which offer a practical and flexible approach to approximating the sampling distribution of the estimator without requiring explicit knowledge of the data-generating process.

Let  $\{X_i^1\}_{i=1}^{n_1}$ and

$\{X_i^1\}_{i=1}^{n_1}$ and  $\{X_i^2\}_{i=1}^{n_2}$ denote independent samples drawn from distributions

$\{X_i^2\}_{i=1}^{n_2}$ denote independent samples drawn from distributions ![]() $F_1$ and

$F_1$ and ![]() $F_2$, respectively. For each

$F_2$, respectively. For each ![]() $b = 1, \ldots, B$, we independently generate bootstrap samples

$b = 1, \ldots, B$, we independently generate bootstrap samples  $\{X_i^{1\ast b}\}_{i=1}^{n_1}$ and

$\{X_i^{1\ast b}\}_{i=1}^{n_1}$ and  $\{X_i^{2\ast b}\}_{i=1}^{n_2}$ by resampling with replacement from the original data. The empirical distribution functions and corresponding quantile functions are then defined as

$\{X_i^{2\ast b}\}_{i=1}^{n_2}$ by resampling with replacement from the original data. The empirical distribution functions and corresponding quantile functions are then defined as

\begin{equation*}

\hat{F}^{\ast b}_j(x) = \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^{j\ast b} \leq x\}}, \quad x \in [0,\infty), \quad j = 1,2,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\hat{F}^{\ast b}_j(x) = \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^{j\ast b} \leq x\}}, \quad x \in [0,\infty), \quad j = 1,2,

\end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}

\hat{Q}^{\ast b}_j(p) = \inf \{x \in [0, \infty): \hat{F}^{\ast b}_j(x) \geq p\}, \quad p \in [0,1].

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\hat{Q}^{\ast b}_j(p) = \inf \{x \in [0, \infty): \hat{F}^{\ast b}_j(x) \geq p\}, \quad p \in [0,1].

\end{equation*} The bootstrap estimators of the Lorenz curves and the functional ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ are given by

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ are given by

\begin{equation*}

\hat{L}^{\ast b}_j(p) = \frac{1}{\hat{\mu}^{\ast b}_j}\int_{0}^{p} \hat{Q}^{\ast b}_j(t) \, {\rm dt}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\hat{L}^{\ast b}_j(p) = \frac{1}{\hat{\mu}^{\ast b}_j}\int_{0}^{p} \hat{Q}^{\ast b}_j(t) \, {\rm dt}\end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b} =\Gamma(\hat{F}^{\ast b}_1,\hat{F}^{\ast b}_2)=\mu\{p: \hat{L}^{\ast b}_1(p) \lt \hat{L}^{\ast b}_2(p),\; p \in (0, 1)\},\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b} =\Gamma(\hat{F}^{\ast b}_1,\hat{F}^{\ast b}_2)=\mu\{p: \hat{L}^{\ast b}_1(p) \lt \hat{L}^{\ast b}_2(p),\; p \in (0, 1)\},\end{equation*} where  $\hat{\mu}^{\ast b}_j = \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} X_i^{j\ast b}$. The empirical distribution of

$\hat{\mu}^{\ast b}_j = \frac{1}{n_j} \sum_{i=1}^{n_j} X_i^{j\ast b}$. The empirical distribution of ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b}$, for

$\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b}$, for ![]() $b \!=\! 1, \ldots, B$, is then utilized to approximate the distribution of

$b \!=\! 1, \ldots, B$, is then utilized to approximate the distribution of ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$. The validity of this approximation is underpinned by the following theorem.

$\hat{\Gamma}$. The validity of this approximation is underpinned by the following theorem.

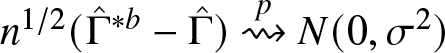

Theorem 3.1 Under Assumptions 2.1–2.3, as ![]() $n \to \infty$,

$n \to \infty$,

\begin{equation*}

\sup_{x} \left| \mathrm{P}^\ast \left( n^{1/2} (\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b} - \hat{\Gamma}) \le x \right)

- \mathrm{P} \left( n^{1/2} (\hat{\Gamma} - \Gamma) \le x \right) \right| = \boldsymbol{o}_p(1),

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sup_{x} \left| \mathrm{P}^\ast \left( n^{1/2} (\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b} - \hat{\Gamma}) \le x \right)

- \mathrm{P} \left( n^{1/2} (\hat{\Gamma} - \Gamma) \le x \right) \right| = \boldsymbol{o}_p(1),

\end{equation*} where ![]() $\mathrm{P}^\ast$ denotes the conditional probability given the original samples

$\mathrm{P}^\ast$ denotes the conditional probability given the original samples  $\{X_i^1\}_{i=1}^{n_1}$ and

$\{X_i^1\}_{i=1}^{n_1}$ and  $\{X_i^2\}_{i=1}^{n_2}$.

$\{X_i^2\}_{i=1}^{n_2}$.

3.2. Bootstrap confidence intervals and hypothesis testing

For a given ![]() $\alpha \in (0, 1/2]$, confidence intervals for

$\alpha \in (0, 1/2]$, confidence intervals for ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ at level

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ at level ![]() $1 - \alpha$ can be constructed using the

$1 - \alpha$ can be constructed using the ![]() $\alpha$-quantiles of the empirical distribution of

$\alpha$-quantiles of the empirical distribution of ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b} - \hat{\Gamma}$, denoted by

$\hat{\Gamma}^{\ast b} - \hat{\Gamma}$, denoted by ![]() $z^\ast_\alpha$. Specifically:

$z^\ast_\alpha$. Specifically:

\begin{equation*}

\text{Two-sided interval:} \quad \left[\hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_{1 - \alpha/2}, \, \hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_{\alpha/2} \right],

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\text{Two-sided interval:} \quad \left[\hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_{1 - \alpha/2}, \, \hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_{\alpha/2} \right],

\end{equation*} \begin{equation*}

\text{Lower one-sided interval:} \quad \left[\hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_{1 - \alpha}, \, 1 \right],

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\text{Lower one-sided interval:} \quad \left[\hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_{1 - \alpha}, \, 1 \right],

\end{equation*} \begin{equation*}

\text{Upper one-sided interval:} \quad \left[0, \, \hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_\alpha \right].

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\text{Upper one-sided interval:} \quad \left[0, \, \hat{\Gamma} - z^\ast_\alpha \right].

\end{equation*} Using these intervals, we may test the following hypotheses for a fixed ![]() $\gamma \in [0, 1]$:

$\gamma \in [0, 1]$:

\begin{align*}

&H_0^1: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = \gamma, \\

&H_0^2: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \geq \gamma, \\

&H_0^3: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \leq \gamma.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

&H_0^1: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = \gamma, \\

&H_0^2: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \geq \gamma, \\

&H_0^3: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \leq \gamma.

\end{align*} To interpret these procedures correctly, it is important to distinguish between the true income distributions ![]() $F_1$ and

$F_1$ and ![]() $F_2$ and their empirical counterparts

$F_2$ and their empirical counterparts ![]() $\widehat{F}_1$ and

$\widehat{F}_1$ and ![]() $\widehat{F}_2$. Bootstrap samples are drawn independently from the original data for each population, and the resulting resamples are used to construct the empirical distributions

$\widehat{F}_2$. Bootstrap samples are drawn independently from the original data for each population, and the resulting resamples are used to construct the empirical distributions ![]() $\widehat{F}_1$ and

$\widehat{F}_1$ and ![]() $\widehat{F}_2$, which serve as nonparametric estimators of the underlying distributions. The bootstrap therefore approximates the sampling distribution of

$\widehat{F}_2$, which serve as nonparametric estimators of the underlying distributions. The bootstrap therefore approximates the sampling distribution of ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ under the data-generating processes represented by the empirical distributions, without constructing artificial distributions that impose the restriction

$\hat{\Gamma}$ under the data-generating processes represented by the empirical distributions, without constructing artificial distributions that impose the restriction ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2) = \gamma$. Inference proceeds by using the bootstrap distribution of

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2) = \gamma$. Inference proceeds by using the bootstrap distribution of ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ to form confidence intervals for

$\hat{\Gamma}$ to form confidence intervals for ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ and to assess whether the hypothesized value

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ and to assess whether the hypothesized value ![]() $\gamma$ lies within these intervals. This approach avoids parametric assumptions and provides valid inference under mild regularity conditions.

$\gamma$ lies within these intervals. This approach avoids parametric assumptions and provides valid inference under mild regularity conditions.

The LDI is designed to quantify the extent to which LD holds between two distributions, particularly in cases where their Lorenz curves intersect. Accordingly, hypotheses involving ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ align directly with the interpretive purpose of the index. Although one could alternatively test the stronger hypothesis

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ align directly with the interpretive purpose of the index. Although one could alternatively test the stronger hypothesis ![]() $H_0 : L_1 = L_2$—for example, by pooling the two mean-normalized samples, treating the pooled population as the common null, and drawing two bootstrap subsamples—the null of exact equality of Lorenz curves addresses a distinct question. Such a test concerns full equality of income distributions, whereas the LDI focuses on the breadth of (near) dominance rather than exact equality. For this reason, we focus our inference framework on hypotheses involving

$H_0 : L_1 = L_2$—for example, by pooling the two mean-normalized samples, treating the pooled population as the common null, and drawing two bootstrap subsamples—the null of exact equality of Lorenz curves addresses a distinct question. Such a test concerns full equality of income distributions, whereas the LDI focuses on the breadth of (near) dominance rather than exact equality. For this reason, we focus our inference framework on hypotheses involving ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$.

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$.

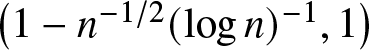

Given the symmetry ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 1 - \Gamma(F_2, F_1)$, we focus on values of

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 1 - \Gamma(F_2, F_1)$, we focus on values of ![]() $\gamma \in [0, 0.5]$. When

$\gamma \in [0, 0.5]$. When ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ is close to zero, the main interest lies in testing whether

$\hat{\Gamma}$ is close to zero, the main interest lies in testing whether ![]() $F_1$ strictly Lorenz-dominates

$F_1$ strictly Lorenz-dominates ![]() $F_2$; i.e.,

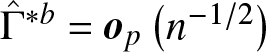

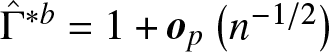

$F_2$; i.e.,  $H_0^1: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0$. In such boundary cases, the convergence of

$H_0^1: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0$. In such boundary cases, the convergence of ![]() $\hat{\Gamma} - \hat{\Gamma}^\ast$ in probability may lead to excessively narrow intervals with undercoverage. To address this, we adjust the bootstrap critical values by setting

$\hat{\Gamma} - \hat{\Gamma}^\ast$ in probability may lead to excessively narrow intervals with undercoverage. To address this, we adjust the bootstrap critical values by setting

where ![]() $\nu \gt 0$ is a small constant (e.g.,

$\nu \gt 0$ is a small constant (e.g., ![]() $\nu = 0.005$), as used in our simulation study.

$\nu = 0.005$), as used in our simulation study.

When ![]() $\hat{\Gamma} \in (0, 0.5)$, it suggests that

$\hat{\Gamma} \in (0, 0.5)$, it suggests that ![]() $F_1$ exhibits a higher degree of equality than

$F_1$ exhibits a higher degree of equality than ![]() $F_2$, though not to the extent of strict LD. In this context, we consider testing the hypothesis

$F_2$, though not to the extent of strict LD. In this context, we consider testing the hypothesis  $H_0^2: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \geq \gamma$ against the alternative

$H_0^2: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \geq \gamma$ against the alternative ![]() $H_a^2: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \lt \gamma$, where

$H_a^2: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) \lt \gamma$, where ![]() $\gamma \in (0, 0.5)$ denotes a practically significant threshold. Common choices include

$\gamma \in (0, 0.5)$ denotes a practically significant threshold. Common choices include ![]() $\gamma = 0.1$ or

$\gamma = 0.1$ or ![]() $\gamma = 0.3$, corresponding to moderate or strong dominance, respectively.

$\gamma = 0.3$, corresponding to moderate or strong dominance, respectively.

Conversely, when ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ is close to

$\hat{\Gamma}$ is close to ![]() $0.5$, this suggests that the two distributions exhibit similar levels of inequality. In such cases, we test the null hypothesis

$0.5$, this suggests that the two distributions exhibit similar levels of inequality. In such cases, we test the null hypothesis  $H_0^1: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0.5$ as a benchmark for symmetry. Rejection of

$H_0^1: \Gamma(F_1, F_2) = 0.5$ as a benchmark for symmetry. Rejection of ![]() $H_0^1$ indicates a significant asymmetry in inequality between the two distributions. Moreover, rejection of

$H_0^1$ indicates a significant asymmetry in inequality between the two distributions. Moreover, rejection of ![]() $H_0^2$ (or

$H_0^2$ (or ![]() $H_0^3$ for

$H_0^3$ for ![]() $F_2$) provides additional evidence that one distribution exhibits lower inequality relative to the other.

$F_2$) provides additional evidence that one distribution exhibits lower inequality relative to the other.

4. Monte Carlo simulation

This section is organized into three subsections. First, we evaluate the consistency of our estimator and examine the effectiveness of the proposed bootstrap procedure through Monte Carlo simulations under a range of distributional scenarios. Next, we conduct hypothesis testing for the three proposed hypotheses using various values of ![]() $\gamma$, reflecting different degrees of partial dominance. Finally, we compare the performance of our method with that of [Reference Sun and Beare17], as well as the approach developed by [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4] for testing strict LD.

$\gamma$, reflecting different degrees of partial dominance. Finally, we compare the performance of our method with that of [Reference Sun and Beare17], as well as the approach developed by [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4] for testing strict LD.

4.1. Consistency and accuracy of the estimator

To enhance the realism of our simulations, we generate data from the following distributions: ![]() $\text{log-normal LN}(\mu, \sigma^2)$,

$\text{log-normal LN}(\mu, \sigma^2)$, ![]() $\text{Pareto Pa}(\alpha, k)$,

$\text{Pareto Pa}(\alpha, k)$, ![]() $\text{Weibull W}(a, \sigma)$ (see [Reference Sarabia, Castillo and Slottje16], [Reference Krause14]). Let

$\text{Weibull W}(a, \sigma)$ (see [Reference Sarabia, Castillo and Slottje16], [Reference Krause14]). Let ![]() $X^1 \sim F_1$ and

$X^1 \sim F_1$ and ![]() $X^2 \sim F_2$ denote two independent samples drawn from respective distributions

$X^2 \sim F_2$ denote two independent samples drawn from respective distributions ![]() $F_1$ and

$F_1$ and ![]() $F_2$. Define the true value of the LDI as

$F_2$. Define the true value of the LDI as ![]() $\Gamma_0 = \Gamma(F_1, F_2)$. We investigate the following scenarios based on different configurations of

$\Gamma_0 = \Gamma(F_1, F_2)$. We investigate the following scenarios based on different configurations of ![]() $F_1$ and

$F_1$ and ![]() $F_2$:

$F_2$:

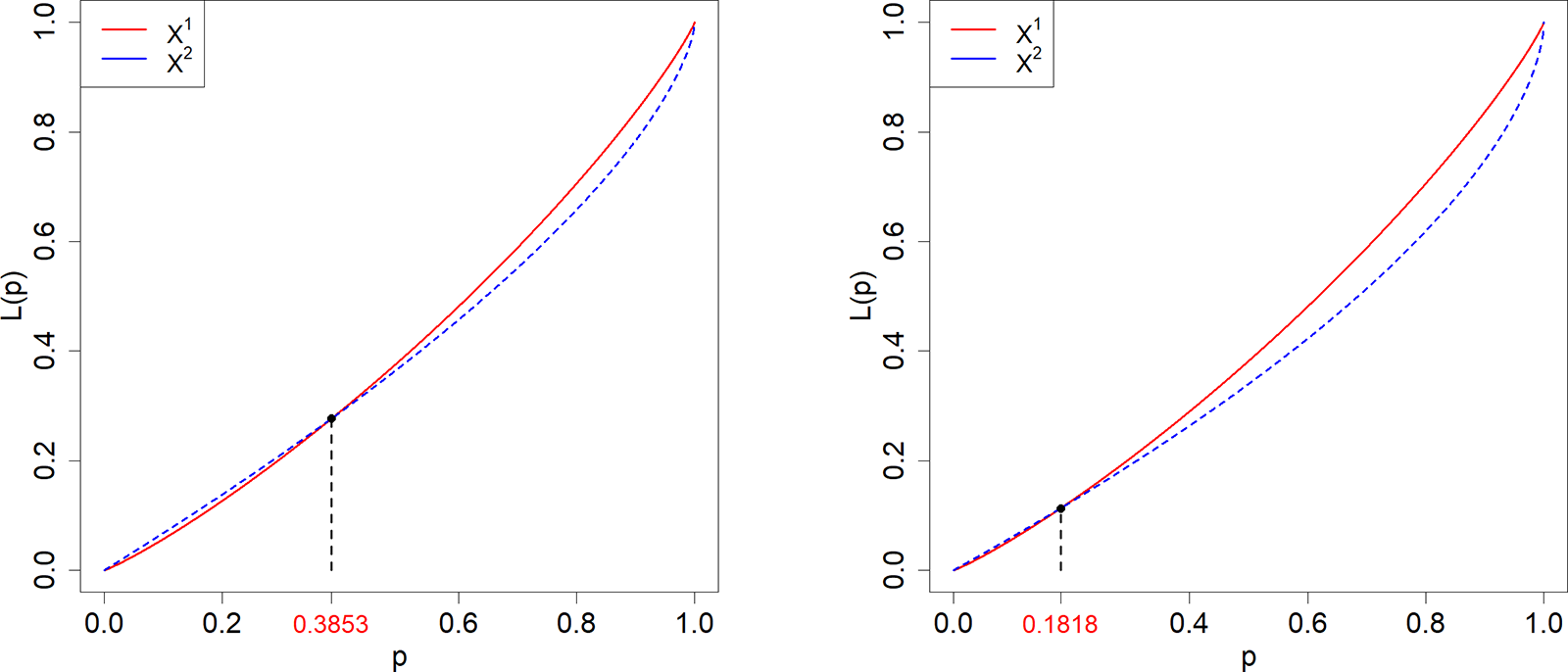

Case 1. ![]() $X^1\sim \text{LN}(0,0.3^2)$,

$X^1\sim \text{LN}(0,0.3^2)$, ![]() $X^2\sim \text{Pa}(1,3)$;

$X^2\sim \text{Pa}(1,3)$; ![]() $\Gamma_0=0.3853.$

$\Gamma_0=0.3853.$

Case 2. ![]() $X^1\sim \text{LN}(0,0.3^2)$,

$X^1\sim \text{LN}(0,0.3^2)$, ![]() $X^2\sim\text{Pa}(1,2.5)$;

$X^2\sim\text{Pa}(1,2.5)$; ![]() $\Gamma_0=0.1818.$

$\Gamma_0=0.1818.$

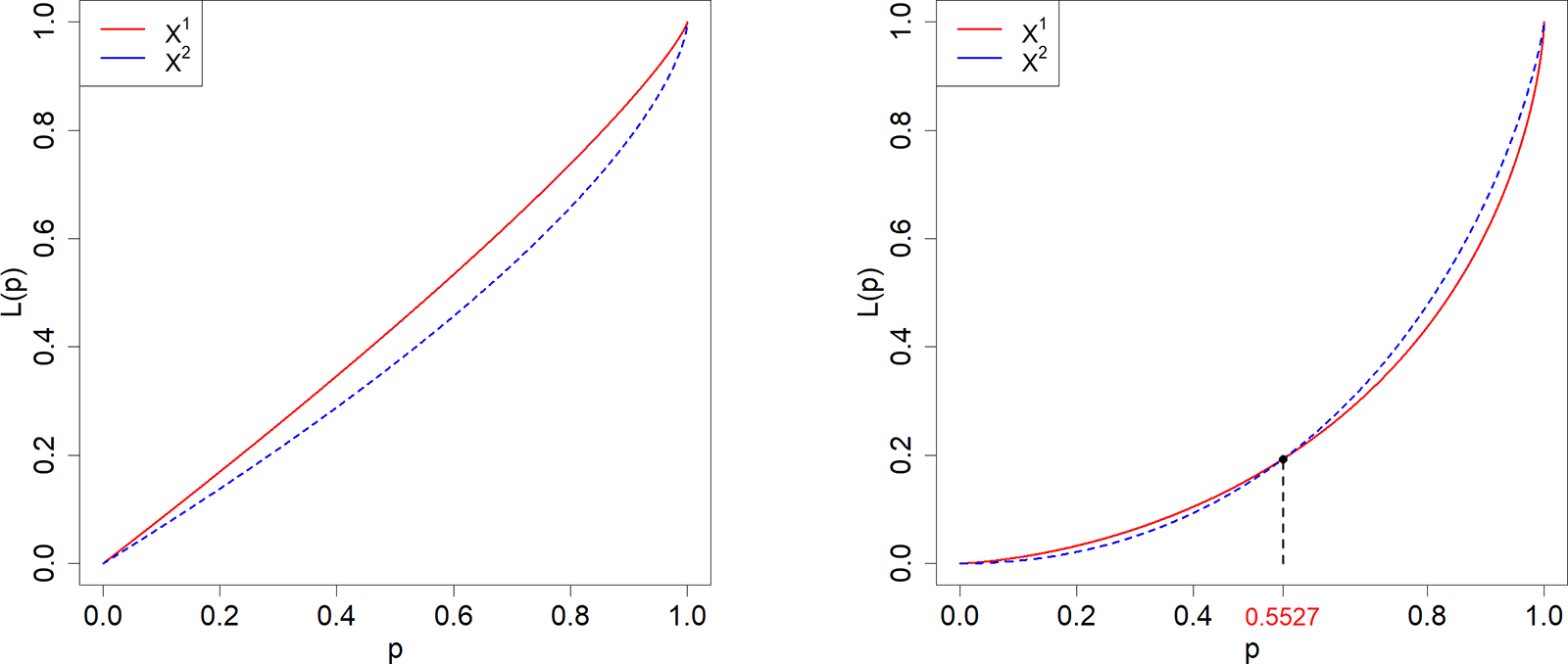

Case 3. ![]() $X^1\sim \text{Pa}(1,6)$,

$X^1\sim \text{Pa}(1,6)$, ![]() $X^2\sim \text{Pa}(1,3)$;

$X^2\sim \text{Pa}(1,3)$; ![]() $\Gamma_0=0.$

$\Gamma_0=0.$

Case 4. ![]() $X^1\sim \text{LN}(0.2,1)$,

$X^1\sim \text{LN}(0.2,1)$, ![]() $X^2\sim \text{W}(1,2.7)$;

$X^2\sim \text{W}(1,2.7)$; ![]() $\Gamma_0=0.4473.$

$\Gamma_0=0.4473.$

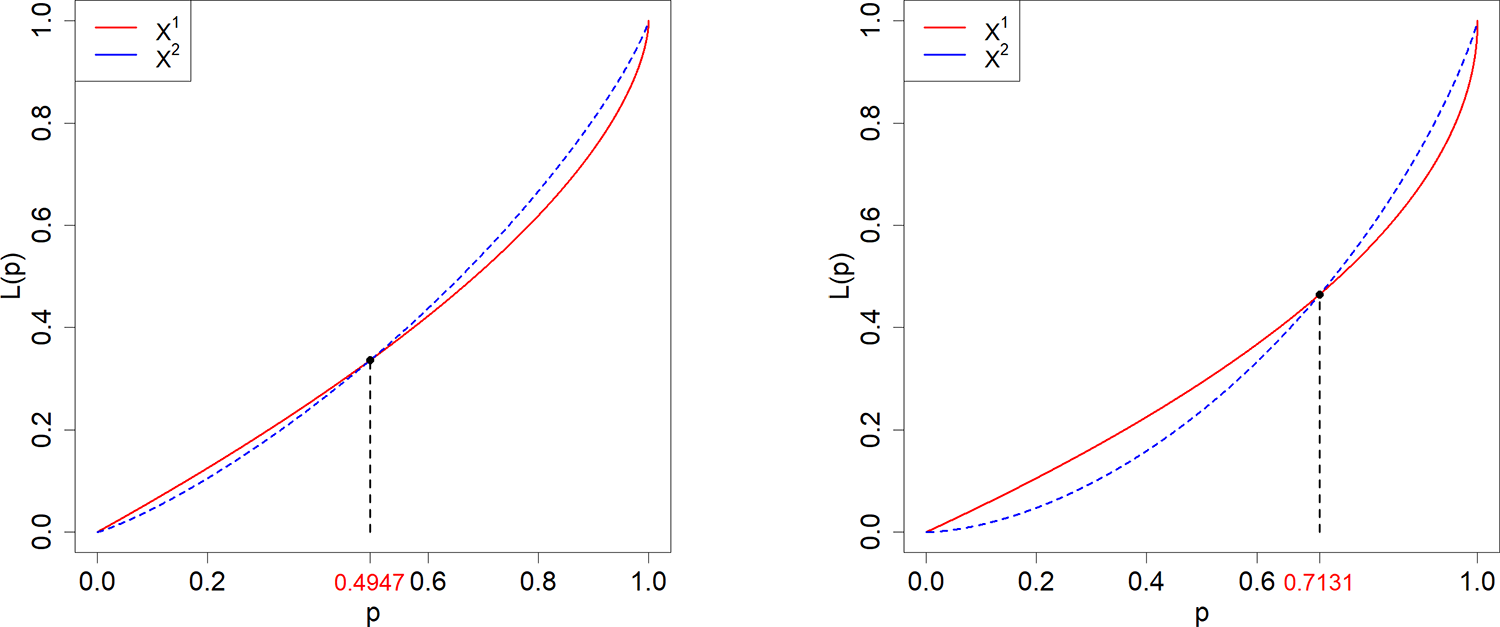

Case 5. ![]() $X^1\sim \text{Pa}(1,2.5)$,

$X^1\sim \text{Pa}(1,2.5)$, ![]() $X^2\sim \text{LN}(0,0.41^2)$;

$X^2\sim \text{LN}(0,0.41^2)$; ![]() $\Gamma_0=0.5053.$

$\Gamma_0=0.5053.$

Case 6. ![]() $X^1\sim \text{LN}(0.2,1^2)$,

$X^1\sim \text{LN}(0.2,1^2)$, ![]() $X^2\sim \text{W}(1,2.7)$;

$X^2\sim \text{W}(1,2.7)$; ![]() $\Gamma_0=0.2869.$

$\Gamma_0=0.2869.$

Case 7. In this scenario, we use the illustrative example introduced in Subsection 2.2. Specifically, ![]() $X^1$ and

$X^1$ and ![]() $X^2$ are drawn from populations A and B, respectively, and we set the value of

$X^2$ are drawn from populations A and B, respectively, and we set the value of ![]() $\Gamma_0$ to

$\Gamma_0$ to ![]() $0.23$.

$0.23$.

Figures 2, 3, 4 illustrate the Lorenz curves for Cases 1–6, and Figure 1 shows the Lorenz curves for Case 7.

Figure 2. Lorenz curves for ![]() $X^1$ (dashed) and

$X^1$ (dashed) and ![]() $X^2$ (solid) according to Cases 1 and 2.

$X^2$ (solid) according to Cases 1 and 2.

Figure 3. Lorenz curves for ![]() $X^1$ (dashed) and

$X^1$ (dashed) and ![]() $X^2$ (solid) according to Cases 3 and 4.

$X^2$ (solid) according to Cases 3 and 4.

Figure 4. Lorenz curves for ![]() $X^1$ (dashed) and

$X^1$ (dashed) and ![]() $X^2$ (solid) according to Cases 5 and 6.

$X^2$ (solid) according to Cases 5 and 6.

We assess the finite-sample performance of the estimators using two metrics: the RMSE of the estimator itself (![]() $\text{RMSE}_1$) and the RMSE of its log odds (

$\text{RMSE}_1$) and the RMSE of its log odds (![]() $\text{RMSE}_2$). These are calculated as:

$\text{RMSE}_2$). These are calculated as:

\begin{align*}

\text{RMSE}1 &= \left[\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{k=1}^N\left(\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}-\Gamma_0\right)^2\right]^{1/2}, \\

\text{RMSE}2 &= \left\{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{k=1}^N\left[\log\left(\frac{\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}}{1-\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}}\right)-\log\left(\frac{\Gamma_0}{1-\Gamma_0}\right)\right]^2\right\}^{1/2},

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\text{RMSE}1 &= \left[\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{k=1}^N\left(\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}-\Gamma_0\right)^2\right]^{1/2}, \\

\text{RMSE}2 &= \left\{\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{k=1}^N\left[\log\left(\frac{\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}}{1-\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}}\right)-\log\left(\frac{\Gamma_0}{1-\Gamma_0}\right)\right]^2\right\}^{1/2},

\end{align*} where ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}$ is the estimate from the

$\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}$ is the estimate from the ![]() $k$-th replication and

$k$-th replication and ![]() $N$ is the total number of simulations. Since the LDI

$N$ is the total number of simulations. Since the LDI ![]() $\Gamma$ is bounded between 0 and 1, the log odds ratio provides a natural and informative metric for evaluating estimation precision ([Reference Zhuang, Hu and Chen21]). To ensure numerical stability when computing

$\Gamma$ is bounded between 0 and 1, the log odds ratio provides a natural and informative metric for evaluating estimation precision ([Reference Zhuang, Hu and Chen21]). To ensure numerical stability when computing ![]() $\text{RMSE}_1$, we adjust any instance where

$\text{RMSE}_1$, we adjust any instance where ![]() $\Gamma_0$ or

$\Gamma_0$ or ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}$ equals 0 or 1 by adding or subtracting a small constant value

$\hat{\Gamma}^{(k)}$ equals 0 or 1 by adding or subtracting a small constant value ![]() $\mu$. In our simulations, we set

$\mu$. In our simulations, we set ![]() $N=1000$ and

$N=1000$ and ![]() $\mu=10^{-5}$. The results, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate the consistency and reliability of the proposed estimator.

$\mu=10^{-5}$. The results, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate the consistency and reliability of the proposed estimator.

Table 1. ![]() $\text{RMSE}_1$s and

$\text{RMSE}_1$s and ![]() $\text{RMSE}_2$s of our empirical estimators.

$\text{RMSE}_2$s of our empirical estimators.

For each case, we construct two-sided confidence intervals at the ![]() $90\%$,

$90\%$, ![]() $95\%$, and

$95\%$, and ![]() $99\%$ levels and record the proportion of times they contain the true value of the LDI. In all experiments, the sample sizes are fixed at

$99\%$ levels and record the proportion of times they contain the true value of the LDI. In all experiments, the sample sizes are fixed at ![]() $n_1 = n_2 = 2000$, with

$n_1 = n_2 = 2000$, with ![]() $B = 999$ bootstrap replications and

$B = 999$ bootstrap replications and ![]() $N = 2000$ simulation repetitions. The results are reported in Table 2.

$N = 2000$ simulation repetitions. The results are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Coverage probabilities of bootstrap confidence intervals.

Overall, the simulated coverage probabilities align well with the nominal levels (![]() $1 - \alpha$), indicating strong finite-sample performance. An exception occurs in Case 3, where extremely narrow intervals require the use of a small constant for stability, leading to coverage rates of

$1 - \alpha$), indicating strong finite-sample performance. An exception occurs in Case 3, where extremely narrow intervals require the use of a small constant for stability, leading to coverage rates of ![]() $100\%$.

$100\%$.

4.2. Hypothesis testing performance

We proceed to apply the bootstrap method to test the hypotheses ![]() $H^{1}_0$,

$H^{1}_0$, ![]() $H^{2}_0$, and

$H^{2}_0$, and ![]() $H^{3}_0$ corresponding to the threshold values

$H^{3}_0$ corresponding to the threshold values ![]() $\gamma = 0.1$,

$\gamma = 0.1$, ![]() $0.3$, and

$0.3$, and ![]() $0.5$, respectively. As in the previous experiments, the sample sizes are fixed at

$0.5$, respectively. As in the previous experiments, the sample sizes are fixed at ![]() $n_1 = n_2 = 2000$, the number of bootstrap replications is set to

$n_1 = n_2 = 2000$, the number of bootstrap replications is set to ![]() $B = 999$, and the number of Monte Carlo repetitions to

$B = 999$, and the number of Monte Carlo repetitions to ![]() $N = 2000$. The resulting rejection frequencies for each case are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5 respectively.

$N = 2000$. The resulting rejection frequencies for each case are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5 respectively.

Table 3. Rejection rates of ![]() $H^{1}_0$ with different

$H^{1}_0$ with different ![]() $\gamma$.

$\gamma$.

Table 4. Rejection rates of ![]() $H^{2}_0$ with different

$H^{2}_0$ with different ![]() $\gamma$.

$\gamma$.

Table 5. Rejection rates of ![]() $H^{3}_0$ with different

$H^{3}_0$ with different ![]() $\gamma$.

$\gamma$.

The simulation results reveal several notable patterns. In Case 3, ![]() $F_1$ strictly Lorenz dominates

$F_1$ strictly Lorenz dominates ![]() $F_2$, as evidenced by consistently high rejection rates across all thresholds. In Cases 1, 2, 4, and 6,

$F_2$, as evidenced by consistently high rejection rates across all thresholds. In Cases 1, 2, 4, and 6, ![]() $F_1$ exhibits generally lower inequality than

$F_1$ exhibits generally lower inequality than ![]() $F_2$ over the majority of the population, while Case 5 reflects approximate parity between the two distributions, with correspondingly low rejection frequencies.

$F_2$ over the majority of the population, while Case 5 reflects approximate parity between the two distributions, with correspondingly low rejection frequencies.

Case 7, corresponding to the illustrative example in Subsection 2.2, warrants particular attention. Here, the LDI indicates that ![]() $F_1$ is less unequal than

$F_1$ is less unequal than ![]() $F_2$ for the majority of the population. In contrast, the 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the difference in Gini coefficients,

$F_2$ for the majority of the population. In contrast, the 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the difference in Gini coefficients, ![]() $[-0.04, 0.037]$, includes zero, signaling no statistically significant difference. This comparison underscores the key advantage of the LDI: it captures the breadth of (near) LD even when conventional area-based measures, such as the Gini, fail to reveal meaningful distributional differences. These findings highlight the practical relevance of the LDI, offering policymakers a more nuanced assessment of which population segments benefit from more equitable income distributions.

$[-0.04, 0.037]$, includes zero, signaling no statistically significant difference. This comparison underscores the key advantage of the LDI: it captures the breadth of (near) LD even when conventional area-based measures, such as the Gini, fail to reveal meaningful distributional differences. These findings highlight the practical relevance of the LDI, offering policymakers a more nuanced assessment of which population segments benefit from more equitable income distributions.

4.3. Comparison with alternative methods

Previous studies by [Reference Reed15] and [Reference Toda18] have convincingly shown that the double Pareto distribution offers a flexible and robust framework for modeling income distributions. The probability density function (pdf) of the normalized double Pareto distribution, denoted as ![]() $\text{dP}(\alpha, \beta)$, is defined as

$\text{dP}(\alpha, \beta)$, is defined as

\begin{equation*}

f(x)=\begin{cases}

\frac{\alpha \beta}{\alpha+\beta} x^{-\alpha-1}, & \text{for } x \geq 1, \\

\frac{\alpha \beta}{\alpha+\beta} x^{\beta-1}, & \text{for } 0 \leq x \lt 1.

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

f(x)=\begin{cases}

\frac{\alpha \beta}{\alpha+\beta} x^{-\alpha-1}, & \text{for } x \geq 1, \\

\frac{\alpha \beta}{\alpha+\beta} x^{\beta-1}, & \text{for } 0 \leq x \lt 1.

\end{cases}

\end{equation*} Building on this model, [Reference Sun and Beare17]) investigated distributional comparisons between ![]() $X^1 \sim \text{dP}(3, 1.5)$ and

$X^1 \sim \text{dP}(3, 1.5)$ and ![]() $X^2 \sim \text{dP}(2.1, \beta)$, with

$X^2 \sim \text{dP}(2.1, \beta)$, with ![]() $\beta$ ranging from

$\beta$ ranging from ![]() $1.5$ to

$1.5$ to ![]() $4$ in increments of

$4$ in increments of ![]() $0.1$. For all

$0.1$. For all ![]() $\beta \gt 1.5$,

$\beta \gt 1.5$, ![]() $X^1$ does not Lorenz dominate

$X^1$ does not Lorenz dominate ![]() $X^2$, where the parameter

$X^2$, where the parameter ![]() $\beta$ varies from

$\beta$ varies from ![]() $1.5$ to

$1.5$ to ![]() $4$ in increments of

$4$ in increments of ![]() $0.1$. For all values of

$0.1$. For all values of ![]() $\beta \gt 1.5$,

$\beta \gt 1.5$, ![]() $X^1$ fails to Lorenz dominate

$X^1$ fails to Lorenz dominate ![]() $X^2$, providing a meaningful benchmark for evaluating the power of LD tests—higher rejection frequencies in these settings indicate better performance.

$X^2$, providing a meaningful benchmark for evaluating the power of LD tests—higher rejection frequencies in these settings indicate better performance.

Both [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4] and [Reference Sun and Beare17] proposed LD testing procedures based on two key test statistics:

\begin{equation*}

I=\int_0^1\max\left\{L_2(p)-L_1(p),0\right\}

{\rm dp}

\text{\ and \ } S=\sup_{p\in[0,1]}\left\{L_2(p)-L_1(p)\right\},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

I=\int_0^1\max\left\{L_2(p)-L_1(p),0\right\}

{\rm dp}

\text{\ and \ } S=\sup_{p\in[0,1]}\left\{L_2(p)-L_1(p)\right\},

\end{equation*}which assess deviations from dominance across the entire distribution. These methods employ distinct bootstrap techniques for inference.

For comparison, we replicate their experimental setup under the null hypothesis ![]() $H_0^1$ and the reversed hypothesis

$H_0^1$ and the reversed hypothesis ![]() $H_0^3$—both of which correspond to tests of strict LD when

$H_0^3$—both of which correspond to tests of strict LD when ![]() $\gamma = 0$. Our evaluation is conducted with fixed sample sizes

$\gamma = 0$. Our evaluation is conducted with fixed sample sizes ![]() $n_1 = n_2 = 2000$, employing

$n_1 = n_2 = 2000$, employing ![]() $B = 999$ bootstrap replications and

$B = 999$ bootstrap replications and ![]() $N = 2000$ Monte Carlo repetitions, all under a nominal significance level of

$N = 2000$ Monte Carlo repetitions, all under a nominal significance level of ![]() $5\%$. The results are summarized and benchmarked against the performance of our proposed method.

$5\%$. The results are summarized and benchmarked against the performance of our proposed method.

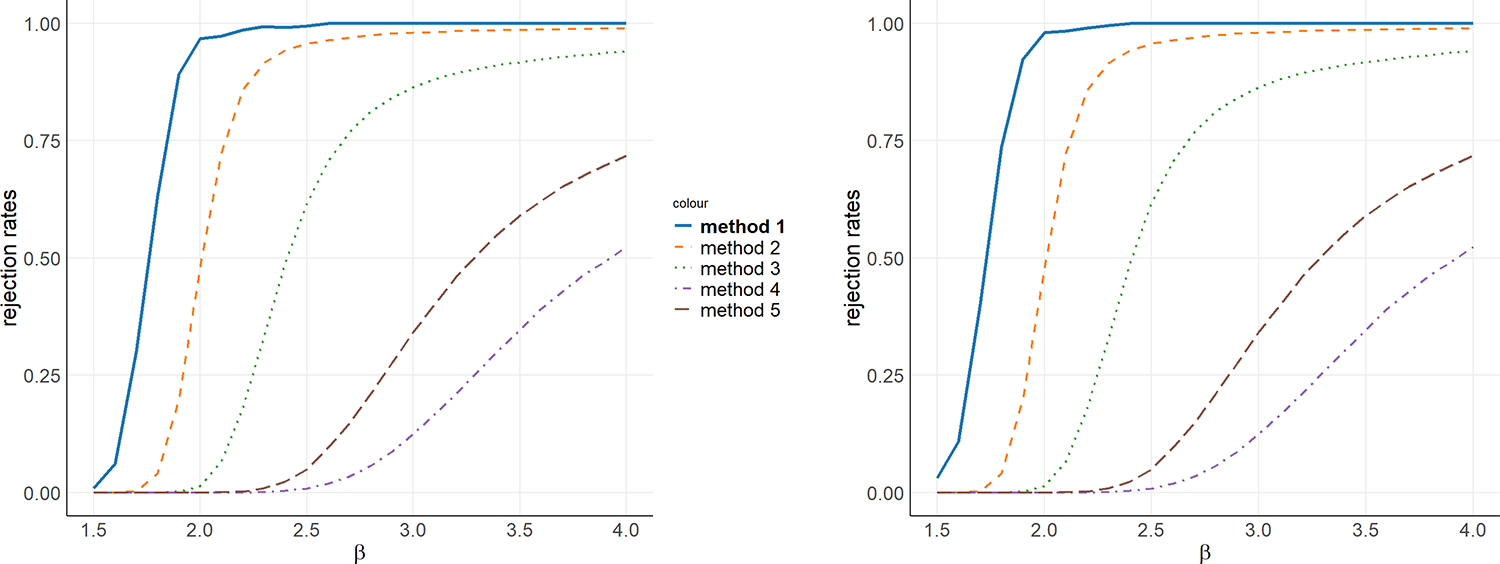

Figure 5 presents the performance of six distinct testing procedures, labeled as Methods 1 through 6, which are defined as follows:

• Method 1: Our proposed method for testing the null hypothesis

$H_0^1$ with

$H_0^1$ with  $\gamma = 0$;

$\gamma = 0$;• Method 2: The approach by [Reference Sun and Beare17] based on the

$S$-statistic;

$S$-statistic;• Method 3: The approach by [Reference Sun and Beare17] based on the

$I$-statistic;

$I$-statistic;• Method 4: The method proposed by [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4] utilizing the

$I$-statistic;

$I$-statistic;• Method 5: The method proposed by [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4] utilizing the

$S$-statistic;

$S$-statistic;• Method 6: Our proposed method for testing the reversed hypothesis

$H_0^3$ with

$H_0^3$ with  $\gamma = 0$.

$\gamma = 0$.

Figure 5. Power with ![]() $X^1 \sim \text{dP}(3, 1.5)$ and

$X^1 \sim \text{dP}(3, 1.5)$ and ![]() $X^2 \sim \text{dP}(2.1, \beta)$ is illustrated as a function of the parameter

$X^2 \sim \text{dP}(2.1, \beta)$ is illustrated as a function of the parameter ![]() $\beta$.

$\beta$.

As illustrated in Figure 5, our proposed methods (Methods 1 and 6) consistently achieve higher rejection rates across a range of evaluated scenarios, demonstrating a superior capacity to detect deviations from LD. This performance underscores the enhanced sensitivity of our tests in capturing inequality differences between distributions, particularly when compared to existing approaches. The consistently stronger rejection rates further attest to the robustness and practical effectiveness of our methods in applied LD testing.

5. An empirical example

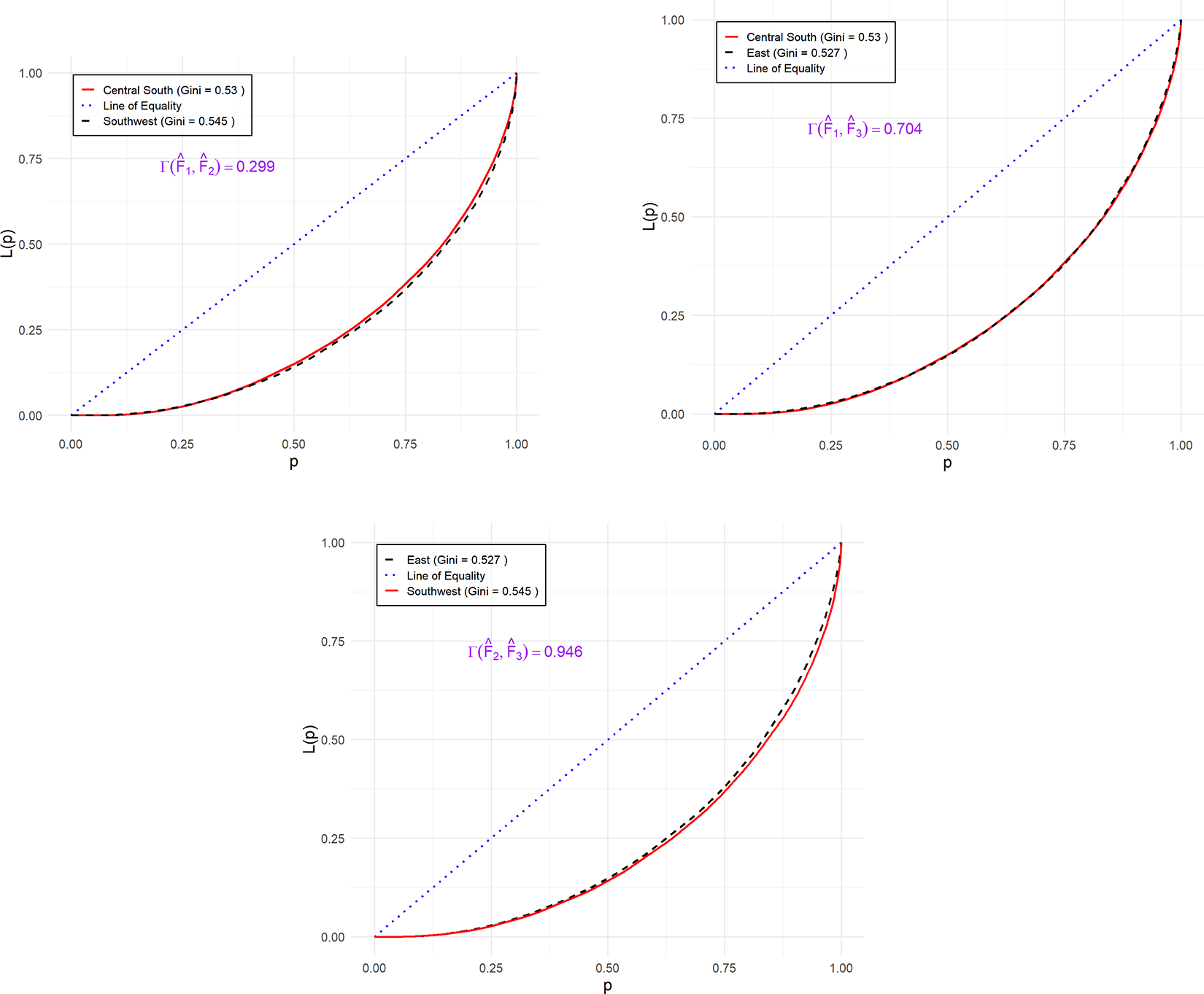

To illustrate the practical application of the LDI, we conduct an empirical analysis using 2,020 household income data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Our focus is on income distributions across three major regional groupings in China: the Central South (Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan), Southwest (Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet), and East (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong) regionsFootnote 1, denoted as ![]() $ F_1 $–

$ F_1 $–![]() $ F_3 $, respectively.

$ F_3 $, respectively.

Table 6 presents summary statistics for each region’s income distribution, including the mean, standard deviation, kurtosis, median, Gini coefficient, and sample size. These descriptive statistics provide key insights into regional income disparities. Among the three, the East region (![]() $F_3$) reports the highest mean and median household incomes, indicating a relatively wealthier population. However, its Gini coefficient (0.527) is only slightly lower than those of the Central South (0.530) and Southwest (0.545), suggesting that income inequality remains considerable despite higher average incomes. The Southwest region (

$F_3$) reports the highest mean and median household incomes, indicating a relatively wealthier population. However, its Gini coefficient (0.527) is only slightly lower than those of the Central South (0.530) and Southwest (0.545), suggesting that income inequality remains considerable despite higher average incomes. The Southwest region (![]() $F_2$) exhibits both the lowest mean and median incomes as well as the highest Gini coefficient, reflecting not only lower overall wealth but also more pronounced income inequality. The Central South region (

$F_2$) exhibits both the lowest mean and median incomes as well as the highest Gini coefficient, reflecting not only lower overall wealth but also more pronounced income inequality. The Central South region (![]() $F_1$) occupies a middle ground in terms of income levels and inequality, yet it records the greatest income dispersion of the Southwest region as evidenced by its high standard deviation and extreme kurtosis. These findings highlight significant regional variation in both income levels and distributions, underscoring the need for localized and more sensitive measures of inequality.

$F_1$) occupies a middle ground in terms of income levels and inequality, yet it records the greatest income dispersion of the Southwest region as evidenced by its high standard deviation and extreme kurtosis. These findings highlight significant regional variation in both income levels and distributions, underscoring the need for localized and more sensitive measures of inequality.

Table 6. Summary statistics for household income of different areas in 2,020.

Figure 6 displays the empirical Lorenz curves for the income distributions of the three regions. The curves appear to intersect at several points, indicating the absence of a clear LD ordering among the distributions. This ambiguity renders standard LD tests inconclusive for pairwise comparisons, thus reinforcing the importance of employing more refined metrics—such as the LDI—for comparative inequality analysis.

Figure 6. The empirical Lorenz curves of ![]() $F_1$–

$F_1$–![]() $F_3$.

$F_3$.

To investigate regional income inequality, we apply the LDI framework to conduct pairwise comparisons of income distributions across three major regions. For each comparison, we construct two-sided confidence intervals using ![]() $B = 999$ bootstrap replications, with a significance level of

$B = 999$ bootstrap replications, with a significance level of ![]() $\alpha = 0.05$ and a smoothing constant

$\alpha = 0.05$ and a smoothing constant ![]() $\nu = 0.005$. The estimated LDI values and their corresponding

$\nu = 0.005$. The estimated LDI values and their corresponding ![]() $95\%$ confidence intervals are presented below:

$95\%$ confidence intervals are presented below:

\begin{align*}

\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_2) &= 0.299 \quad \text{[0.177, 0.411]} &\quad

\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_1) &= 0.701 \quad \text{[0.589, 0.823]} \\

\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_3) &= 0.704 \quad \text{[0.615, 0.792]} &\quad

\Gamma(\hat{F}_3, \hat{F}_1) &= 0.296 \quad \text{[0.208, 0.385]} \\

\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_3) &= 0.946 \quad \text{[0.895, 1.000]} &\quad

\Gamma(\hat{F}_3, \hat{F}_2) &= 0.054 \quad \text{[0.000, 0.105]}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_2) &= 0.299 \quad \text{[0.177, 0.411]} &\quad

\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_1) &= 0.701 \quad \text{[0.589, 0.823]} \\

\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_3) &= 0.704 \quad \text{[0.615, 0.792]} &\quad

\Gamma(\hat{F}_3, \hat{F}_1) &= 0.296 \quad \text{[0.208, 0.385]} \\

\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_3) &= 0.946 \quad \text{[0.895, 1.000]} &\quad

\Gamma(\hat{F}_3, \hat{F}_2) &= 0.054 \quad \text{[0.000, 0.105]}

\end{align*}These results provide an intuitive and quantitative perspective on how inequality differs across regions. The LDI captures the proportion of the population over which one region exhibits lower income inequality than another, thus offering a richer interpretation than binary dominance methods.

For example, the estimate ![]() $\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_3) = 0.946$ indicates that nearly

$\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_3) = 0.946$ indicates that nearly ![]() $95\%$ of the population in the East (

$95\%$ of the population in the East (![]() $F_3$) experiences lower inequality compared to the Southwest (

$F_3$) experiences lower inequality compared to the Southwest (![]() $F_2$). The confidence interval lies entirely above 0.5, providing strong statistical evidence of dominance by the East.

$F_2$). The confidence interval lies entirely above 0.5, providing strong statistical evidence of dominance by the East.

Similarly, ![]() $\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_3) = 0.704$, with its confidence interval also fully above 0.5, suggests a statistically significant advantage in favor of the East (

$\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_3) = 0.704$, with its confidence interval also fully above 0.5, suggests a statistically significant advantage in favor of the East (![]() $F_3$) over the Central South (

$F_3$) over the Central South (![]() $F_1$).

$F_1$).

In contrast, ![]() $\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_2) = 0.299$, with its interval entirely below 0.5, implies that the Central South (

$\Gamma(\hat{F}_1, \hat{F}_2) = 0.299$, with its interval entirely below 0.5, implies that the Central South (![]() $F_1$) exhibits greater inequality than the Southwest (

$F_1$) exhibits greater inequality than the Southwest (![]() $F_2$) over most of the population. By the symmetry of the LDI, this corresponds to

$F_2$) over most of the population. By the symmetry of the LDI, this corresponds to ![]() $\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_1) = 0.701$, confirming that the Central South significantly dominates the Southwest in terms of lower inequality.

$\Gamma(\hat{F}_2, \hat{F}_1) = 0.701$, confirming that the Central South significantly dominates the Southwest in terms of lower inequality.

These empirical findings demonstrate the LDI’s ability to detect and quantify partial dominance and subtle distributional differences. Unlike conventional LD methods, which yield inconclusive results when curves intersect, the LDI provides a continuous, interpretable, and statistically grounded metric. This highlights its practical relevance for policy-oriented analysis of regional disparities.

6. Conclusion

This study introduces the LDI, a novel metric for quantifying deviations from LD in income distributions. We establish the asymptotic normality of the LDI estimator, which supports the application of bootstrap methods for constructing reliable confidence intervals. This statistical foundation reinforces both the theoretical validity and empirical usability of the index.

Monte Carlo simulations across various distributional scenarios confirm the LDI’s consistency and its capacity to detect subtle inequality differences that conventional dominance-based methods may overlook. An empirical application using 2,020 CFPS income data further demonstrates the index’s practical utility in identifying and comparing regional income disparities.

By offering a continuous and interpretable measure of comparative inequality, the LDI complements existing tools for inequality measurement and bridges the gap between binary dominance tests and more nuanced distributional comparisons.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 72571262 and 71971204) and the Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Anhui Province (No. 2208085J43).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Proofs of core results

Let ![]() $\ell^\infty(0,1)$ denote the collection of bounded real-valued functions on

$\ell^\infty(0,1)$ denote the collection of bounded real-valued functions on ![]() $(0,1)$ equipped with the uniform metric, and

$(0,1)$ equipped with the uniform metric, and ![]() $\overset{w}{\rightarrow} $ denote weak convergence in

$\overset{w}{\rightarrow} $ denote weak convergence in ![]() $\ell^\infty(0,1)$. Let

$\ell^\infty(0,1)$. Let ![]() $\overset{p}{\rightsquigarrow}$ denote the convergence in distribution conditionally on the

$\overset{p}{\rightsquigarrow}$ denote the convergence in distribution conditionally on the  $\{X_i^1\}^{n_1}_{i=1}$ and

$\{X_i^1\}^{n_1}_{i=1}$ and  $\{X_i^2\}^{n_2}_{i=1}$.

$\{X_i^2\}^{n_2}_{i=1}$.

Proof of Theorem 2.4.

We begin with some intermediate results required to prove this theorem.

Lemma A.1. Under the conditions of Theorem 2.4, ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ is a consistent estimator.

$\hat{\Gamma}$ is a consistent estimator.

Proof. By Lemma 3 in Barrett et al. [Reference Barrett, Donald and Bhattacharya4], ![]() $\hat{L}_1$ and

$\hat{L}_1$ and ![]() $\hat{L}_2$ are all uniformly consistent. Since

$\hat{L}_2$ are all uniformly consistent. Since ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ is a smooth functional of

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$ is a smooth functional of ![]() $L_1$ and

$L_1$ and ![]() $L_2$, it follows that

$L_2$, it follows that ![]() $\hat{\Gamma}$ is consistent for

$\hat{\Gamma}$ is consistent for ![]() $\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$.

$\Gamma(F_1, F_2)$.

Lemma A.2. Let ![]() $a_n$ be nonrandom positive constants such that

$a_n$ be nonrandom positive constants such that ![]() $a_n \rightarrow 0$ as

$a_n \rightarrow 0$ as ![]() $n \rightarrow \infty$. Under the conditions of Theorem 2.4, for

$n \rightarrow \infty$. Under the conditions of Theorem 2.4, for ![]() $j=1,2$, we have

$j=1,2$, we have

\begin{equation*}

I^j_\xi=\sup _{p:|p-\xi| \leq a_n}\left|\big[\hat{L}_j(p)-\hat{L}_j(\xi)\big]-\big[L_j(p)-L_j(\xi)\big]\right|=\boldsymbol{O}_p\big(n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\big) .

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

I^j_\xi=\sup _{p:|p-\xi| \leq a_n}\left|\big[\hat{L}_j(p)-\hat{L}_j(\xi)\big]-\big[L_j(p)-L_j(\xi)\big]\right|=\boldsymbol{O}_p\big(n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\big) .

\end{equation*}Proof. We prove the result for ![]() $j=1$; the case

$j=1$; the case ![]() $j=2$ follows analogously.

$j=2$ follows analogously.

Let ![]() $\left\{b_n\right\}$ be a sequence of positive integers such that

$\left\{b_n\right\}$ be a sequence of positive integers such that ![]() $b_n \sim$

$b_n \sim$ ![]() $n^{3 / 4}a_n$,

$n^{3 / 4}a_n$, ![]() $n \rightarrow \infty$. For integers

$n \rightarrow \infty$. For integers ![]() $r=-b_n, \ldots, b_n$, define:

$r=-b_n, \ldots, b_n$, define:

\begin{equation*}

\eta_{r, n}=\xi+a_n b_n^{-1} r,\quad\alpha_{r, n}=L_1\left(\eta_{r+1, n}\right)-L_1\left(\eta_{r, n}\right),

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\eta_{r, n}=\xi+a_n b_n^{-1} r,\quad\alpha_{r, n}=L_1\left(\eta_{r+1, n}\right)-L_1\left(\eta_{r, n}\right),

\end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}

G_{r, n}=\left|\big[\hat{L}_1\left(\eta_{r, n}\right)-\hat{L}_1\left(\xi\right)\big]-\left[L_1\big(\eta_{r, n}\right)-L_1\left(\xi\right)\big]\right| .

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

G_{r, n}=\left|\big[\hat{L}_1\left(\eta_{r, n}\right)-\hat{L}_1\left(\xi\right)\big]-\left[L_1\big(\eta_{r, n}\right)-L_1\left(\xi\right)\big]\right| .

\end{equation*} By the monotonicity of ![]() $\hat{L}_1$ and

$\hat{L}_1$ and ![]() $L_1$, we have:

$L_1$, we have:

\begin{equation*}

I^1_\xi \le K_n + \beta_n,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

I^1_\xi \le K_n + \beta_n,

\end{equation*}where

\begin{equation*}

K_n = \max_{-b_n \le r \le b_n} G_{r,n}, \quad \beta_n = \max_{-b_n \le r \le b_n-1} \alpha_{r,n}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

K_n = \max_{-b_n \le r \le b_n} G_{r,n}, \quad \beta_n = \max_{-b_n \le r \le b_n-1} \alpha_{r,n}.

\end{equation*} Since ![]() $\eta_{r+1, n}-\eta_{r, n}=a_n b_n^{-1}\sim n^{-3 / 4}$, and

$\eta_{r+1, n}-\eta_{r, n}=a_n b_n^{-1}\sim n^{-3 / 4}$, and ![]() $-b_n \leq r \leq b_n-1$, using the Mean Value Theorem, we have that

$-b_n \leq r \leq b_n-1$, using the Mean Value Theorem, we have that

\begin{equation*}

\alpha_{r, n} \leq\left(\sup _{p: |p-\xi| \leq a_n} L_1^{\prime}\left(p\right)\right)\left(\eta_{r+1, n}-\eta_{r, n}\right) \sim \left(\sup _{p:|p-\xi| \leq a_n} L_1^{\prime}\left(p\right)\right) n^{-3 / 4}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\alpha_{r, n} \leq\left(\sup _{p: |p-\xi| \leq a_n} L_1^{\prime}\left(p\right)\right)\left(\eta_{r+1, n}-\eta_{r, n}\right) \sim \left(\sup _{p:|p-\xi| \leq a_n} L_1^{\prime}\left(p\right)\right) n^{-3 / 4}.

\end{equation*}Thus,

\begin{equation}

\beta_n=\boldsymbol{O}_p\Big(n^{-3 / 4}\Big), \quad n \rightarrow \infty .

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\beta_n=\boldsymbol{O}_p\Big(n^{-3 / 4}\Big), \quad n \rightarrow \infty .

\end{equation} We now establish that with probability ![]() $1$,

$1$,

\begin{equation}

K_n=\boldsymbol{O}_p\left(n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right), \quad n \rightarrow \infty .

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

K_n=\boldsymbol{O}_p\left(n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right), \quad n \rightarrow \infty .

\end{equation}To prove (A.2), we apply the Borel–Cantelli lemma by showing:

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \lt \infty,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \lt \infty,

\end{equation} for some constant ![]() $c_1 \gt 0$.

$c_1 \gt 0$.

Using a union bound:

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq \sum_{r=-b_n}^{b_n} {\rm P}\left(G_{r, n} \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) .

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq \sum_{r=-b_n}^{b_n} {\rm P}\left(G_{r, n} \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) .

\end{equation*} From Bhattacharya [Reference Bhattacharya5], ![]() $G_{r, n}$ can be written as:

$G_{r, n}$ can be written as:

\begin{equation*}

G_{r, n} = \left| \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[Y_i(\eta_{r, n}) - Y_i(\xi)\right] \right|,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

G_{r, n} = \left| \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[Y_i(\eta_{r, n}) - Y_i(\xi)\right] \right|,

\end{equation*}where

\begin{eqnarray*}

Y_i(p) &=& \frac{1}{\mu} \left( X_i^1 \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^1 \le Q_1(p)\}} - \int_0^p Q_1(t) dt \right)\\

& & \quad\quad + \frac{Q_1(p)}{\mu} \left(p - \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^1 \le Q_1(p)\}}\right)

+ \frac{\int_0^p Q_1(t) dt}{\mu^2}\left(\mu - X_i^1\right).

\end{eqnarray*}

\begin{eqnarray*}

Y_i(p) &=& \frac{1}{\mu} \left( X_i^1 \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^1 \le Q_1(p)\}} - \int_0^p Q_1(t) dt \right)\\

& & \quad\quad + \frac{Q_1(p)}{\mu} \left(p - \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^1 \le Q_1(p)\}}\right)

+ \frac{\int_0^p Q_1(t) dt}{\mu^2}\left(\mu - X_i^1\right).

\end{eqnarray*} For any ![]() $p$ satisfying

$p$ satisfying ![]() $|p - \xi| \le a_n$, the expectation of

$|p - \xi| \le a_n$, the expectation of  $Y^2_i(p)$ is calculated as

$Y^2_i(p)$ is calculated as

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\rm E}\left[Y^2_i(p)\right]=\frac{1}{\mu^2} \left\{{\rm E}\left[\left(X_1^1\right)^2 \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^1 \le Q_1(p)\}}\right] - \left(\int_0^p Q_1(t) dt\right)^2 \right\}\\

+ \frac{Q^2_1(p)}{\mu^2}(p - p^2) + \frac{\left(\int_0^p Q_1(t) dt\right)^2}{\mu^4} \rm{Var}(X^1_1).

\end{eqnarray*}

\begin{eqnarray*}

{\rm E}\left[Y^2_i(p)\right]=\frac{1}{\mu^2} \left\{{\rm E}\left[\left(X_1^1\right)^2 \mathbb{I}_{\{X_i^1 \le Q_1(p)\}}\right] - \left(\int_0^p Q_1(t) dt\right)^2 \right\}\\

+ \frac{Q^2_1(p)}{\mu^2}(p - p^2) + \frac{\left(\int_0^p Q_1(t) dt\right)^2}{\mu^4} \rm{Var}(X^1_1).

\end{eqnarray*} A related expression for the expectation of the squared difference between ![]() $Y_i(\eta_{r, n})$ and

$Y_i(\eta_{r, n})$ and ![]() $Y_i(\xi)$ is given by

$Y_i(\xi)$ is given by

\begin{equation*}

\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i(\eta_{r, n}) - Y_i(\xi)\right]^2 = \boldsymbol{O}_p(|\eta_{r, n} - \xi|).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i(\eta_{r, n}) - Y_i(\xi)\right]^2 = \boldsymbol{O}_p(|\eta_{r, n} - \xi|).

\end{equation*}Applying Hoeffding’s inequality, we obtain

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(G_{r, n} \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq 2 e^{-\theta_{r, n}},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(G_{r, n} \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq 2 e^{-\theta_{r, n}},

\end{equation*}where

\begin{equation*}

\theta_{r, n}=\frac{n ( c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n)^2}{2{\rm E}[Y_1(\eta_{r, n})-Y_1(\xi)]^2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\theta_{r, n}=\frac{n ( c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n)^2}{2{\rm E}[Y_1(\eta_{r, n})-Y_1(\xi)]^2}.

\end{equation*} Given that  ${\rm E}[Y_i(\eta_{r, n})-Y_i(\xi)]^2 =\boldsymbol{O}_p(|\eta_{r, n} - \xi|)$, there exist constants

${\rm E}[Y_i(\eta_{r, n})-Y_i(\xi)]^2 =\boldsymbol{O}_p(|\eta_{r, n} - \xi|)$, there exist constants ![]() $c_2$ and

$c_2$ and ![]() $N^\ast$ for which

$N^\ast$ for which ![]() ${\rm E}[Y_i(\eta_{r, n})-Y_i(\xi)]^2 \leq c_2 a_n$ when

${\rm E}[Y_i(\eta_{r, n})-Y_i(\xi)]^2 \leq c_2 a_n$ when ![]() $|r| \leq b_n$ and

$|r| \leq b_n$ and ![]() $n \gt N^\ast$. Therefore,

$n \gt N^\ast$. Therefore, ![]() $\theta_{r, n}$ satisfies

$\theta_{r, n}$ satisfies ![]() $\theta_{r, n} \geq \delta_n$ under these conditions, where

$\theta_{r, n} \geq \delta_n$ under these conditions, where

\begin{equation*}

\delta_n = \frac{n\left( c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right)^2}{2c_2 a_n} = \frac{c_1^2 \log n}{2c_2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\delta_n = \frac{n\left( c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right)^2}{2c_2 a_n} = \frac{c_1^2 \log n}{2c_2}.

\end{equation*} For a given ![]() $c_2$, selecting

$c_2$, selecting ![]() $c_1$ sufficiently large ensures that

$c_1$ sufficiently large ensures that  $\frac{c_1^2}{2c_2} \gt 2$. It follows that

$\frac{c_1^2}{2c_2} \gt 2$. It follows that

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(G_{r, n} \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq 2 n^{-2}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(G_{r, n} \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq 2 n^{-2}

\end{equation*} for ![]() $|r| \leq b_n$ and

$|r| \leq b_n$ and ![]() $n \gt N^*$. Consequently, for

$n \gt N^*$. Consequently, for ![]() $n \geq N^*$,

$n \geq N^*$,

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq 8 b_n n^{-2}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) \leq 8 b_n n^{-2}

\end{equation*}implying

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) = \boldsymbol{O}_p\left(n^{-3/2}\right).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\rm P}\left(K_n \geq c_1 n^{-1 / 2} a^{1/2}_n\log^{1/2} n\right) = \boldsymbol{O}_p\left(n^{-3/2}\right).

\end{equation*}Therefore, conditions (A.2) and (A.3) have been verified, and together with (A.1), this concludes the proof.

Lemma A.3. Assuming the conditions of Theorem 2.4, let ![]() $p^\ast$ be the first cross point of

$p^\ast$ be the first cross point of ![]() $L_1$ and

$L_1$ and ![]() $L_2$. With probability approaching

$L_2$. With probability approaching ![]() $1,~ \hat{L}_1$ and

$1,~ \hat{L}_1$ and ![]() $\hat{L}_2$ have no cross points in the interval

$\hat{L}_2$ have no cross points in the interval  $\left(n^{-1/2}(\log n)^{-1}, p^\ast-\epsilon\right)$ for any sufficiently small positive constant

$\left(n^{-1/2}(\log n)^{-1}, p^\ast-\epsilon\right)$ for any sufficiently small positive constant ![]() $\epsilon$ as

$\epsilon$ as ![]() $n \rightarrow \infty$. Furthermore, we can conclude that

$n \rightarrow \infty$. Furthermore, we can conclude that ![]() $\hat{L}_1(p)-\hat{L}_2(p)$ can have cross points in the intervals