Introduction

With future intended human missions to Mars, it is vital that we understand if conditions on Mars could ever sustain life to inform scientific (history and habitability), planetary protection (of Mars and Earth) and exploration (robotic and human) goals (Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Spry, Broyan, Castro-Wallace, Sato, Mahoney and Robinson2023). Conditions on Mars that are hospitable or inhospitable to terrestrial life expand our understanding of the limits of life, while harmful conditions can also be exploited to meet planetary protection goals. To sustain human exploration of Mars, soils and ecosystems that can support plants will be needed. This will involve developing and testing experimental set ups on Earth using various combinations of plants and microbial life, i.e. multiple species interacting with each other in a closed system (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Pechurkin, Allen, Somova, Gitelson, Wang, Ivanov and Tay2010). Species to be used on Mars must tolerate transit and martian conditions, such as radiation levels, range of temperature, etc. As potential candidates for establishing soil ecosystems on Mars we tested tardigrades, a group of valuable model organisms for animal development and survival of extreme conditions (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein2022). Despite not having an immediate practical utility for humans, tardigrades can be important members of ecological communities and thus help the establishment of functional soils for plant growth on Mars (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Bartels, Guil and Schill2018).

Conditions on Mars are generally inhospitable to terrestrial life (Rummel et al., Reference Rummel, Beaty, Jones, Bakermans, Barlow, Boston, Chevrier, Clark, de Vera, Gough, Hallsworth, Head, Hipkin, Kieft, McEwen, Mellon, Mikucki, Nicholson, Omelon, Peterson, Roden, Sherwood Lollar, Tanaka, Viola and Wray2014). The martian atmosphere comprises 95.1% CO2, 2.59% N2, 1.94% Ar and other minor constituents such as 0.16% O2. The atmospheric pressure is about 7 mbar, and there are frequent violent dust storms. The temperature ranges between a low of −153 °C at the poles and a high of 20 °C during the day at the equator, with an annual global average of −65 °C. Ultraviolet (200–400 nm) flux averages about 50 W/m2 at the surface. There is no magnetic field to protect life on the surface from the harmful effects of ionizing and cosmic radiation. Components of the regolith can be hazardous and include salts, acids, heavy metals, perchlorates and volatile oxidants (Schuerger et al., Reference Schuerger, Golden and Ming2012). While the atmosphere and regolith of Mars are very dry; water is present in subsurface reservoirs as hydrated minerals or embedded ground ice or permafrost or liquid water in the mid-crust (Jakosky, Reference Jakosky2021; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Morzfeld and Manga2024). Clearly survival on Mars will be challenging and hardy species (both extremophiles and extreme tolerant organisms) will be needed – even in protected habitats.

An expanding number of experiments have demonstrated that some microorganisms can survive and/or grow for a limited time during simulation of single to multiple martian conditions in chambers on Earth, which cannot easily replicate the cosmic radiation and gravity environment of Mars. For example, several methanogens survived exposure to low pressures (Mickol and Kral, Reference Mickol and Kral2017) and cyanobacteria from cryptobiotic crusts survived exposure to martian pressure, atmospheric composition, variable humidity and UV irradiation (de Vera et al., Reference de Vera, Dulai, Kereszturi, Koncz, Lorek, Mohlmann, Marschall and Pocs2014). Furthermore, the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp PCC 7938 grew in simulated martian atmospheric conditions (pressure and composition) with martian regolith simulant MGS-1 (Verseux et al., Reference Verseux, Heinicke, Ramalho, Determann, Duckhorn, Smagin and Avila2021). These methanogens or cyanobacteria, as primary producers, could serve as food sources for primary consumers like tardigrades in soils.

Tardigrades are among the few metazoan groups able to survive, but not reproduce in, extreme environmental conditions through an almost complete stopping of their metabolism, i.e. cryptobiosis (Guidetti et al., Reference Guidetti, Altiero and Rebecchi2011; Wright, Reference Wright2001). While in cryptobiosis, tardigrades can also survive many extreme conditions: high pressures (Jönsson and Bertolani, Reference Jönsson and Bertolani2001; Seki and Toyoshima, Reference Seki and Toyoshima1998), the vacuum of space (Jönsson et al., Reference Jönsson, Rabbow, Schill, Harms-Ringdahl and Rettberg2008), desiccation (Boothby et al., Reference Boothby, Tapia, Brozena, Piszkiewicz, Smith, Giovannini, Rebecchi, Pielak, Koshland and Goldstein2017; Wełnicz et al., Reference Wełnicz, Grohme, Kaczmarek, Schill and Frohme2011), freezing (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Bartels, Guil and Schill2018), temperature extremes and radiation levels far greater than that which could be tolerated by a human (Horikawa et al., Reference Horikawa, Sakashita, Katagiri, Watanabe, Kikawada, Nakahara, Hamada, Wada, Funayama, Higashi, Kobayashi, Okuda and Kuwabara2006). Because of their resilience, tardigrades are excellent models for metazoan survival of extreme conditions that can inform the potential habitability of extraterrestrial environments and are of great interest to astrobiology.

As a result of their small size (0.05 to 1.2 mm length) and metabolic adaptations (e.g. cryptobiosis), tardigrades can colonize a variety of environments on Earth, ranging from limno-terrestrial (leaf litter, soil, mosses, lichens) to aquatic habitats (periphyton, sediment) (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Bartels, Guil and Schill2018). When colonizing terrestrial environments, tardigrades require at least a film of water surrounding their bodies to perform activities necessary for life. Tardigrades serve important roles in food webs as primary consumers and predators, feeding on a wide range of organisms, including bacteria, algae, fungi and nematodes (Nelson, Reference Nelson2002). For example, tardigrades can contribute to the control of plant-feeding nematode populations through predation (Sánchez-Moreno et al., Reference Sánchez-Moreno, Ferris and Guil2008). Both primary consumers and predators are needed in a healthy soil microbiome (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Dumack, Trivedi, Islam and Hu2023; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Song, Yang, Gu, Wei, Kowalchuk, Xu, Jousset, Shen and Geisen2020), which should contain a range of microorganisms able to decompose organic matter and mineralize nutrients for increased availability to plants and other organisms. Establishing healthy soil microbiomes in martian regoliths is essential to create martian soils that promote plant growth.

To better understand how microorganisms and plants could survive in martian regolith, simulants that mimic the chemistry and mineralogy of the regolith have been developed (see review Ramkissoon et al., Reference Ramkissoon, Pearson, Schwenzer, Schröder, Kirnbauer, Wood, Seidel, Miller and Olsson-Francis2019). For example, simulants JSC-Mars-1(a), MMS and JMSS-1 are based on the martian global regolith chemistry; while simulants MGS-1 and OUCM-1 mimic the Rocknest deposit at Gale Crater. Specific chemical environments have also been modeled by simulants P-MRA and S-MRA, which represent pH neutral and acidic martian environments, respectively. To date, microorganisms (Bauermeister et al., Reference Bauermeister, Rettberg and Flemming2014; Schirmack et al., Reference Schirmack, Alawi and Wagner2015; Schuerger et al., Reference Schuerger, Ming and Golden2017) and plants (Berni et al., Reference Berni, Leclercq, Roux, Hausman, Renaut and Guerriero2023; Chinnannan et al., Reference Chinnannan, Somagattu, Yammanuru, Nimmakayala, Chakrabarti and Reddy2023; Oze et al., Reference Oze, Beisel, Dabsys, Dall, North, Scott, Lopez, Holmes and Fendorf2021) have been tested in various martian simulants, but tardigrades have not yet been tested.

The aim of this study is to better understand the potential habitability of martian regolith and its use as a resource for plant growth. Specifically, we examined the active states of two taxa (Ramazzottius cf. varieornatus and Hypsibius exemplaris) of tardigrades during a short-term exposure to martian regolith simulants. As a first step toward understanding tardigrade survival on Mars, we examined the impact of simulants only (not of other martian conditions). Populations of tardigrades were exposed to martian regolith simulants MGS-1 and OUCM-1, which were chosen based on availability and chemical composition representative of Mars, specifically the Rocknest formation at Gale Crater (Ramkissoon et al., Reference Ramkissoon, Pearson, Schwenzer, Schröder, Kirnbauer, Wood, Seidel, Miller and Olsson-Francis2019). These experiments, concerning the survivability of tardigrades in simulated martian regolith, have ramifications for the choice of species for functional soils to support plants and humans on Mars and can yield insight into the limitations of terrestrial life and the habitability of extraterrestrial environments.

Materials and methods

Soil simulants

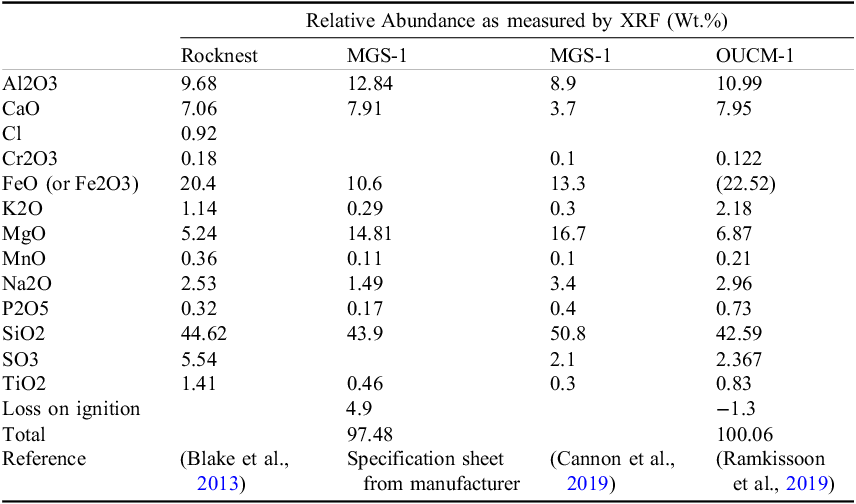

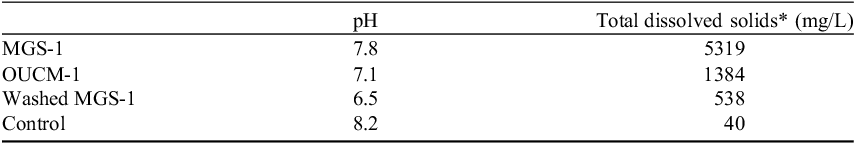

Two martian regolith simulants (Table 1) modeled on the Rocknest aeolian deposit at Gale Crater on Mars were used along with terrestrial sand as control. Simulant MGS-1 (Cannon et al., Reference Cannon, Britt, Smith, Fritsche and Batcheldor2019) was obtained from Exolith Lab, CO, USA. Median particle size of MGS-1 was 150 µm, with 80% of particles finer than 300 µm. Simulant OUCM-1 (<280 µm fraction) was obtained from N. Ramkissoon, Open University, UK (Ramkissoon et al., Reference Ramkissoon, Pearson, Schwenzer, Schröder, Kirnbauer, Wood, Seidel, Miller and Olsson-Francis2019). Siliceous sand from Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts, USA (+41.461592 −70.558629) was used as a control. Sand was washed repeatedly with distilled water and autoclaved before use. Particle sizes of sand ranged from 250 to 2000 µm with 87% of particles >500 µm. MGS-1 was washed four times as follows: 20 mL ddH2O was added to 10 g MGS-1 in a 50 mL conical tube, shaken well, centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant decanted. After the final wash, “washed MGS-1” was air dried in a fume hood for several days. The pH and conductivity of samples was measured using standard techniques (see Table 2).

Table 1. Bulk chemistry of martian regolith and simulants

Table 2. Properties of simulant extracts

*As determined from conductivity measurements.

Organisms

Populations of the tardigrade species Ramazzottius cf. varieornatus (which will be referred to as Ramazzottius throughout remainder of manuscript) were collected from dried sediments from ephemeral freshwater rock pools in the Italian Northern Apennines between May 2019 and June 2020. Sample coordinates are: Sample 132 (+44.387468 +10.021142), Sample 284 (+44.387520 +10.021026) and Sample 778 (+44.396427 +10.004250). Sediment samples were kept desiccated and frozen at −20 °C at the Polish Academy of Sciences until use. Samples 132, 284 and 778 were collected under sampling permit N.1128 of 4/4/2019 from Parco Nazionale Appennino Tosco-Emiliano. The tardigrade species Hypsibius exemplaris strain Z151 (Gąsiorek et al., Reference Gąsiorek, Stec, Morek and Michalczyk2018) and the green alga Auxenochlorella pyrenoidosa (Calvo Pérez Rodó and Molinari-Novoa, Reference Calvo Pérez Rodó and Molinari-Novoa2015) were obtained from Carolina Biological Supply Company, Burlington, NC, USA.

Preparation of tardigrade inoculums

To activate the anhydrobiotic Ramazzottius, sediment samples were mixed with distilled H2O (volume equivalent to 1.5 times the weight of the sample) in 50 mL tubes and incubated for 24 hours at 15°C in a Model 3724 Fisher Scientific Low Temperature Incubator. Tardigrades were separated from the denser sediments by density centrifugation. Specifically, three volumes of 1.15 g mL−1 density solution of LUDOX® TM-50 colloidal silica was added to 1 volume of hydrated samples and mixed well prior to centrifugation for 1 min at 1000×g. During centrifugation, the denser sediment particles collect at the bottom, while the less dense tardigrades and other organic materials remain in the supernatant. Subsequently, tardigrades were collected from supernatant by passing supernatant through a 20 μm cellular sieve (pluriStrainer, pluriSelect Life Science, Leipzig, Germany). Tardigrades on sieves were rinsed with distilled water and all flow-through was discarded. Tardigrades were collected from sieves by inverting the sieve and rinsing with distilled water into a clean 50 mL tube. Distilled water was added as needed to achieve the desired final volume (about 6 mL) of inoculum. Hypsibius exemplaris were used in active form as shipped by Carolina Biological Supply Company. To ensure food was plentiful in inoculums, the green alga A. pyrenoidosa was added (0.5 mL of a visibly dense culture).

Exposure to simulants

Tardigrades were exposed to martian simulants in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes as follows. To each tube, 0.25 g dry simulant (control, MGS-1, OUCM-1, or washed MGS-1) and 0.25 mL inoculum (with A. pyrenoidosa) were added and mixed by inverting gently several times. Duplicate or triplicate tubes were prepared for each time point*treatment*population. Tubes were incubated on their sides at 15°C (Ramazzottius) or 20°C (H. exemplaris) for 12 hours light, 12 hours dark under full-spectrum LED lights to provide a day/night cycle that supports tardigrade activity. Tubes were opened for 10–15 minutes every two days for air exchange.

Assessment of tardigrade activity

At different exposure time points (0, 2, 4 days), tardigrades were collected and separated from sediments by adding 1.0 mL of a 1.15 g mL−1 density solution of LUDOX® TM-50 colloidal silica; mixing well; centrifuging for 1 min 1000× g; and transferring the supernatant to a Sedgewick Rafter slide. Slides were viewed at 100× magnification and tardigrades counted. Tardigrades that showed movement were counted as active and alive; immobile tardigrades were counted as inactive and presumed dead. Exuviae were not counted. Raw data is available in supplementary materials. Due to the low numbers of animals in available samples of Ramazzottius it was not possible to test all simulants with all tardigrade populations.

Statistical analyses

Data were fitted to a generalized linear model with binomial distribution in R with active tardigrades as the response variable. Time, species, time*simulant and time*species were used as predictors. For the tardigrade population the intercept was H. exemplaris and for the treatment the intercept was the controls. Residuals were examined for normality and heteroscedasticity by visual inspection of plots produced by the R function check_model from the package “performance” (Lüdecke et al., 2021). R script is available in supplementary materials.

Data, Rscript, images and videos are available at figshare.com (10.6084/m9.figshare.27115375, 10.6084/m9.figshare.27119193, 10.6084/m9.figshare.27119217, 10.6084/m9.figshare.27119226, and 10.6084/m9.figshare.27119271).

Results

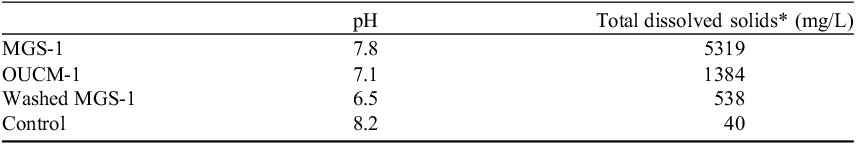

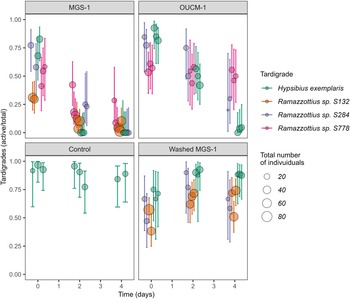

To assess the potential habitability of martian regolith and capabilities of terrestrial life, we examined the survival of active tardigrades in martian regolith simulants. The numbers of active tardigrades in martian simulants MGS-1 and OUCM-1 showed marked declines over four days (Fig. 1), while the numbers in controls did not. When the amount of inoculum was large enough (H. exemplaris and S778), a portion of the inoculum was also monitored and showed that tardigrades remained active over the four days with little to no mortality; that is, the number of active tardigrades remained constant. Furthermore, the provided food, A. pyrenoidosa, was visibly abundant in all treatments throughout the experiment, indicating that activity and survival of tardigrades were not limited by food availability.

Figure 1. Tardigrade survival in martian regolith simulants. Observations plotted with 95% confidence interval for binomial distribution shown. Size of circle indicates total number of tardigrades counted. Mean number of animals assessed per replicate was 22 ± 6 for H. exemplaris, 56 ± 15 for Ramazzottius sp. S132, 15 ± 5 for Ramazzottius sp. S284 and 21 ± 8 for Ramazzottius sp. S778.

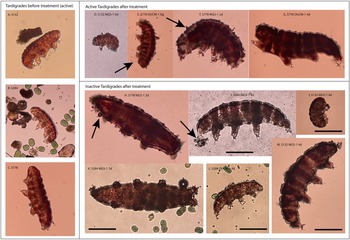

Movement of active (i.e. live) tardigrades ranged from vigorously crawling or swimming to the twitching of only one or two claws (videos available at 10.6084/m9.figshare.27119271). In the control, active tardigrades remained energetic. In MGS-1, most remaining active tardigrades were barely moving after two days; while in OUCM-1 live tardigrades were reasonably energetic at all time points. Inactive tardigrades did not visibly move within 10–15 seconds and were often bloated or slightly curled (Fig. 2); some inactive tardigrades were visibly disrupted or degraded and presumed to be dead. Both active (Figs. 2D–2G) and inactive (Figs. 2H–2M) tardigrades were often seen with mineral particles coating their bodies giving their surface a rough appearance when compared to the smooth exterior of animals in controls (Figs. 2A–2C). Occasionally, inactive tardigrades were found with mineral particles near their mouths (Figs. 2I and 2M).

Figure 2. Images of tardigrades with mineral coatings. Each image is annotated with the sample, simulant and time of exposure in days. Before treatment: Panels A–C show example active animals from inoculums with smooth exteriors. After treatment: Panels D–G show examples of active animals with mineral particles visible as a rough, bumpy exterior (arrows point to examples). Panels H–M show inactive (presumed dead) animals with mineral particles attached. Panels H, K and M show examples of bloated animals. Scale bar is 100 microns and the same size in each image. Images without scale bars are from videos and are shown at approximately the same scale.

To determine the impact of solutes on active tardigrades, MGS-1 was washed (see methods) and included as one of the treatments. Washed MGS-1 had a pH of 6.5 and total dissolved solids of about 538 mg L−1 as determined from conductivity measurements. Indeed, in washed MGS-1, active tardigrades remained vigorous the entire time (Fig. 1) and had fewer minerals coating their bodies.

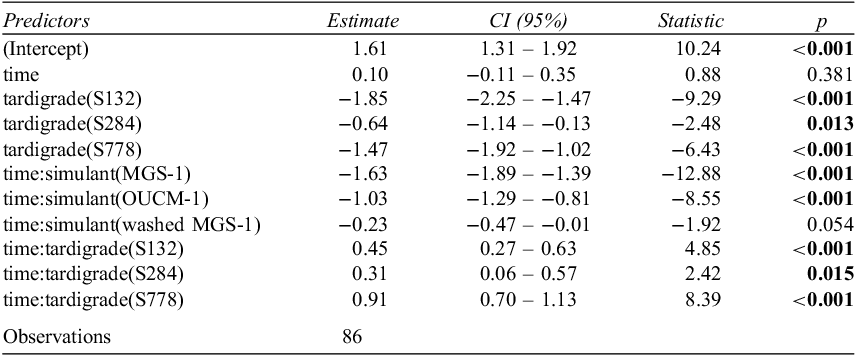

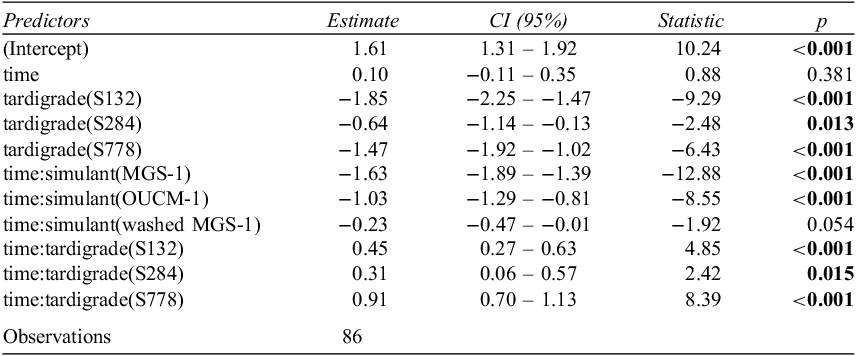

To assess the statistical significance of the observed relationships between tardigrade survival and treatment, a generalized linear regression model was used. The model showed that time, simulant and species were significant (p < 0.0001) predictors of active tardigrades (see Fig. 3 and Table 3). The model supported the conclusion that both simulants MGS-1 and OUCM-1 were detrimental to tardigrades. MGS-1 was the most inhibitory simulant that caused numbers of active tardigrades to decrease the most. Indeed, no live H. exemplaris were found after two days of exposure to MGS-1. Not surprisingly, the model did not distinguish between washed MGS-1 and the control treatment. The model also identified a significant (p < 0.0001) difference between most Ramazzottius populations and H. exemplaris; with Ramazzottius S778 appears to be the hardiest. Indeed, no replicate of Ramazzottius S778 had zero active tardigrades.

Figure 3. Fitted line estimate of generalized linear model. Shaded region shows the 95% confidence interval. Observations were plotted as circles where size indicates the total number of tardigrades counted and with a small offset to enhance visibility of overlapping data points. Note that each population of tardigrades contained approximately the same number of animals in each replicate, thus intra-population differences in circle size should be small.

Table 3. Binomial GLM coefficients estimates

Discussion

We examined tardigrade survival in martian regolith simulants to assess the potential habitability of martian regolith: to illuminate potential uses (e.g. medium for growing food) and potential dangers (e.g. toxicity to animals). Simulant MGS-1 was the most detrimental to tardigrades, followed by OUCM-1. Tardigrade survival was minimally impacted by washed MGS-1 and by the control.

In the tested substrates, active tardigrades could have been negatively impacted by a variety of factors such as pH, particle size, particle shape, solute concentration and chemical composition of martian regolith simulants. The pH probably had no role, as the pH of simulant extracts was within acceptable ranges for active tardigrades. For example, tardigrades can be grown at pH 8. Furthermore, a pH of 6 had little to no impact on activity over 48 hours in three different species: Acutuncus antarcticus, H. exemplaris and Macrobiotus cf. hufelandi (Massa et al., Reference Massa, Rebecchi and Guidetti2023). Particles (natural and manmade) can impact the growth and activity of microfauna (Daghighi et al., Reference Daghighi, Shah, Chia, Lee, Shang and Rodríguez-Seijo2023; Doyle et al., Reference Doyle, Sundh and Almroth2022; Ogonowski et al., Reference Ogonowski, Schür, Jarsén and Gorokhova2016); however, the impact of particle size vs. shape vs. chemical nature cannot usually be differentiated. Particle size can impact sediment rheology and interactions with microfauna independent of sediment chemistry. In this study, particle size may have contributed to differences in survival given that the control sand contained larger particles than MGS-1, washed MGS-1 and OUCM-1, which had relatively similar particle sizes to each other. In addition, very few studies have specifically examined particle effects on tardigrades or other meiofauna (Corinaldesi et al., Reference Corinaldesi, Canensi, Carugati, Lo Martire, Marcellini, Nepote, Sabbatini and Danovaro2022; de França et al., Reference de França, Moens, da Silva, Pessoa, França and Dos Santos2024). In our study, both active and inactive tardigrades were found to be coated in mineral particles (Fig. 2); however, any specific impact could not be determined due to the limited number of available animals.

Tardigrade survival in the various simulants was associated with solute concentration measured as total dissolved solids. That is, MGS-1 with the highest solute concentration was most detrimental, while tardigrades survived best in the control with the lowest solute concentration. Tardigrades also survived well in washed MGS-1. Extracts of MGS-1 are classified as moderately saline and OUCM-1 as slightly saline, while both unwashed MGS-1 and the control can be classified as freshwater, according to the United States Geological Survey. Tardigrades are found in freshwater to marine environments and are known to osmoregulate, but only to a species-specific limit. For example, the marine tardigrade Halobiotus crispae remains active at salinities up to 40 ppt (Halberg et al., Reference Halberg, Persson, Ramløv, Westh, Kristensen and Møbjerg2009); while the limno-terrestrial tardigrade Richtersius coronifer had a lethal limit of 16 ppt (Møbjerg et al., Reference Møbjerg, Halberg, Jørgensen, Persson, Bjørn, Ramløv and Kristensen2011) Ramazzottius varieornatus remained active at 3.2 ppt, but not at 6.4 ppt sucrose (Emdee et al., Reference Emdee, Møbjerg, Grollmann and Møbjerg2024); while Ramazzottius oberhaeuseri remained active at 61 ppt NaCl with gradual exposure (Heidemann et al., Reference Heidemann, Smith, Hygum, Stapane, Clausen, Jørgensen, Hélix-Nielsen and Møbjerg2016). Given that the total dissolved solids of all treatments was below these lethal limits, tardigrades were probably not affected by solutes as osmolytes, but were more likely affected by the toxicity of specific chemicals. Tardigrade survival in washed MGS-1 suggests that potential toxins are water soluble.

The terrestrial Ramazzottius species are more stress-tolerant than the freshwater Hypsibius sp. (Horikawa et al., Reference Horikawa, Kunieda, Abe, Watanabe, Nakahara, Yukuhiro, Sakashita, Hamada, Wada, Katagiri, Kobayashi, Higashi and Takashi2008, Reference Horikawa, Cumbers, Sakakibara, Rogoff, Leuko, Harnoto, Arakawa, Katayama, Kunieda, Toyoda, Fujiyama and Rothschild2013) and, not surprisingly, were found to be less harmed by martian regolith simulants in our study (Fig. 1). Differences in tolerance were readily apparent; for example, individuals from the more sensitive H. exemplaris all died within two days of exposure to MGS-1. In contrast, at least one active tardigrade was found from all Ramazottius populations after eight days of exposure to MGS-1. The number of available tardigrades also limited the ability to include the terrestrial sand control with Ramazottius populations. However, given that H. exemplaris activity in washed MGS-1 was similar to activity in terrestrial sand, it is probable that Ramazzottius activity in terrestrial sand would not have differed from washed MGS-1.

Our data are consistent with previous studies that have shown martian regolith simulants can be damaging to active cells. In one study, vegetative cells of Enterococcus faecalis experienced 2.5 to 5 log reductions when exposed to 2:1 (water: simulant) extracts of all analogs (basalt, salt, acid, alkaline, Phoenix and aeolian), with extremely low pH and high solute concentrations the most detrimental (Schuerger et al., Reference Schuerger, Ming and Golden2017). High concentrations (>1 wt%) of the analogs JSC-Mars-1A, P-MRA and S-MRA were found to be inhibitory to several methanogens; however, lower concentrations supported methane production and growth with buffer and a N2/H2/CO2 headspace at 28 °C (Schirmack et al., Reference Schirmack, Alawi and Wagner2015). Similarly, our study demonstrated that a 1:1 ratio of MGS-1 had a negative impact, which was mitigated by washing. In addition, the cyanobacteria Nostoc muscorum and Anabaena cylindrica grew in 4:1 (v:wt) extracts of MGS-1 with light and oxygen at 20 °C, while Arthrospira platensis could not (Macário et al., Reference Macário, Veloso, Frankenbach, Serôdio, Passos, Sousa, Gonçalves, Ventura and Pereira2022). Sulfur, calcium and potassium were identified as the most abundant elements in aqueous extracts of MGS-1 (Macário et al., Reference Macário, Veloso, Frankenbach, Serôdio, Passos, Sousa, Gonçalves, Ventura and Pereira2022). While none of these studies were able to isolate the effects of individual chemical species, these data suggest that dilution or washing will be necessary to mitigate toxicity of martian regolith and that impacts will be species-specific.

More dilute extracts of simulants have been shown to support the growth of a variety of microorganisms. In addition to the methanogens and cyanobacteria mentioned above, Acidothiobacillus ferrooxidans grew in extracts (5% wt/vol) of simulants P-MRA and S-MRA under oxic and microoxic conditions at 30 °C (Bauermeister et al., Reference Bauermeister, Rettberg and Flemming2014). Furthermore, extracts of OUCM-1 or modeled fluids based on OUCM-1 can support growth of: sulfate-reducing bacteria, acetogenic bacteria and other generalist anaerobic bacteria with a CO2/H2/N2 headspace at 25 °C (Macey et al., Reference Macey, Ramkissoon, Cogliati, Toubes-Rodrigo, Stephens, Kucukkilic-Stephens, Schwenzer, Pearson, Preston and Olsson-Francis2022); sulfur-cycling bacteria and halophilic archaea with a H2/CO2 headspace at 10 °C (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Kelbrick, Ramkissoon, Dugdale, Stephens, Kucukkilic-Stephens, Fox-Powell, Schwenzer, Antunes and Macey2022); heterotrophic bacteria with yeast extract and oxygen at 30 °C (Kelbrick et al., Reference Kelbrick, Oliver, Ramkissoon, Dugdale, Stephens, Kucukkilic-Stephens, Schwenzer, Antunes and Macey2021); and pure cultures of nitrate-reducing bacteria with a N2/CO2 headspace at 25 °C (Price et al., Reference Price, Macey, Pearson, Schwenzer, Ramkissoon and Olsson-Francis2022). These specific species were enriched from sediments from Mars analog environments (estuary mudflats, brine springs and a sulfidic, saline spring system) that were used as starting inoculums. Similarly, our data demonstrated that OUCM-1 can support tardigrades. Notably, one tardigrade population (Ramazzottius sp. S778) was not inhibited by OUCM-1.

Conclusion

Martian simulants MGS-1 and OUCM-1 were both harmful to tardigrades, however OUCM-1 was less harmful. Ramazzottius were more tolerant of simulants than H. exemplaris. Furthermore, washing MGS-1 significantly reduced negative impacts. These data suggest that the specific chemical nature of the simulants is damaging (not pH or solute concentration). Particles and mineral shards could also be detrimental. Future studies should identify the toxicity of individual chemical species and the specific impact of particles on microfauna. These and related data can inform future exploration and planetary protection efforts on Mars. For example, if OUCM-1 more accurately reflects martian regolith, a soil microbiome for plant growth could be established with little to no modification of the regolith. Alternately, if the inhospitable MGS-1 is more accurate, then planetary protection goals may be more easily met in case of accidental release of terrestrial organisms on Mars. However, more testing is necessary to fully understand the potential habitability and dangers of martian regolith. These data also contribute to understanding the limits of tardigrade survival of martian conditions; future studies will examine additional constraints on survival such as martian atmospheric pressure and composition.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1473550425100220.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by the Polonez Bis grant No. 2022/45/P/NZ8/01512 to MV co-funded by the National Science Center and the European Union framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant. CB was funded by a grant from Penn State Altoona’s Office of Research and Engagement.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.