In summer 2001, a South African production of the Chester Mystery Cycle titled Yiimimangaliso: The Mysteries opened at the Wilton Music Hall in London. Unlike most modern productions of Middle English mystery cycles, it featured no medieval costumes or pageant wagons, and it was delivered in seven different languages. Coupling a medieval dramatic text with a contemporary South African aesthetic, the show was an unprecedented success, acclaimed by Charles Spencer of The Telegraph as “one of the most moving, beautiful, human and courageous shows you will ever see.” The Times lauded it as “brilliantly inventive” and reported nightly standing ovations wherein “hundreds of jaded journalists forgot their cynicism and sprang to their feet” (Billington, “Mysteries”). Beyond the production’s multicultural aesthetic, critics praised its spiritual effect, describing it as a show that “will fill a hole in your soul” (Mulkerrins) and as a performance that had “done what the Church of England has been striving to do for decades and given Christianity an audience” (“No Mystery”). The 2001 run quickly sold out, and the production moved to the West End for another sold-out run in 2002 before touring internationally to further acclaim; since then it has been reprised in the United Kingdom in 2009, 2014, and—before its cancellation due to the COVID-19 pandemic—2020.Footnote 1 Only a few months earlier, however, Yiimimangaliso had received a less laudatory response from its South African audience: during its December 2000 premiere at the Spier Arts Festival in Stellenbosch, many members of the predominantly white audience walked out when a black performer spoke the opening lines “I am God” (Riding).Footnote 2 Incensed by the portrayal of God by a person of color, many spectators openly complained about the “Africanization” of the biblical narrative (Fletcher).

This article centers the spiritual efficacy attributed to Yiimimangaliso in its Western, and particularly British, reception. It constitutes part of my ongoing research on the question of modern revivals of medieval mystery cycles and spiritualized reception. As Katie Normington and Sarah Beckwith have observed, the vast majority of modern productions of mystery cycles sublimate or desacralize the religious content of these medieval biblical dramas in the service of secular impetuses—to invoke nostalgia for a premodern medieval imaginary often underpinned by a search for European “national origins” (Beckwith 18) or to buttress secularist values such as “community” and “altruism” (Normington 80). Yiimimangaliso’s distinctly spiritualized reception by British audiences (and the absence of such a reception by South African audiences) disrupts this tendency. In analyzing the response of predominantly white British audiences, I seek to understand how racialized spectatorship functioned to reinvigorate the spiritual efficacy of the Chester Mystery Cycle; while Yiimimangaliso was staged only twice in South Africa to limited review by the press, its repeated success in the United Kingdom, its international tours in the Global North, and its voluble reception by the British press suggest that its indigenous aesthetic and postcolonial syncretism activate a medieval imaginary of religious devotion that is consumed through race.

To date, neither Yiimimangaliso nor any of the South African company’s subsequent stage productions have been mentioned in any of the broad, book-length studies of contemporary South African theater.Footnote 3 This relative dearth of research on Yiimimangaliso speaks to the contested status of contemporary postcolonial adaptations of the Western dramatic canon. In its embrace of a sixteenth-century religious drama, Yiimimangaliso challenges the dominant modes of approaching religion—and Christianity in particular—within postcolonial the ater studies. Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins’s Post-colonial Drama: Theory, Practice, Politics describes the “tyranny of the Bible” as functioning to “dilute the influence of local religions” (46); accordingly, Gilbert and Tompkins focus on postcolonial performances that serve as “reworking[s]” of “Christian myth” that enact “strategic reform” (43) through the intentional “(mis)use of the master narratives of Christianity to illustrate imperialism’s effect on native cultures” (44). As an overt celebration of the biblical Christian narrative, Yiimimangaliso defies this predominant secularist hermeneutic for reading postcolonial Christianity as merely a problematic vestige of settler colonialism, European proselytization, and the suppression of indigenous religions. Such a hermeneutic flattens the multifaceted role Christianity plays in contemporary South Africa, where the percentage of South Africans identifying as Christian has risen to a record high of 85.3% since the end of apartheid (“South Africa”), most notably through growth in African Independent Church membership.Footnote 4 With the recent demographic shift of Christian belief and practice from the Global North to the Global South, studies of the intersection between postcolonial theater and religion must be nuanced beyond Eurocentric assumptions of secularist modernity.Footnote 5

In the light of this context, I analyze Yiimimangaliso’s reception in relation to race and spirituality. First, I investigate its decolonial, syncretic aesthetic; I then discuss its emergence during the formative years after the fall of apartheid; and finally, I interrogate its disparate receptions in South Africa and the United Kingdom through the lens of the phenomenology of race. Drawing on Sianne Ngai’s formulation of “animatedness” (e.g., 92), I argue that Yiimimangaliso’s racialized reception enacted a confluence of notions of the medieval unmodern and the racialized Other—one that reanimated the spiritual affects of the original Chester plays while destabilizing Eurocentric binaries of the sacred and the secular.

Yiimimangaliso’s Postcolonial Syncretism

Following the collapse of apartheid, the South African billionaire and philanthropist Dick Enthoven founded the Spier Arts Festival in Stellenbosch with the vision of using the arts to build a sense of “shared nationhood in this new democracy” (Dornford-May, “Working”). He invited the British director Mark Dornford-May to produce the festival’s first season, impressed by the director’s previous experience bridging cultural and socioeconomic divides through the arts in East London.Footnote 6 Seeking to build an ensemble that was “genuinely South African” in its diversity (Riding), Dornford-May initially held auditions at universities, conservatories, and urban arts organizations; he quickly realized, however, that black performers struggled to access these historically white spaces. Shifting his approach, he began holding auditions in the townships that surround South Africa’s major urban centers. From over two thousand hopefuls, a company of thirty-four black and six white performers was formed, initially called Dimpho di Kopane before changing its name to Isango Ensemble.Footnote 7

For the inaugural season of the Spier Arts Festival, Dornford-May turned to the sixteenth-century Chester plays for their unifying potential: “The stories are accessible to most South Africans; we are not trying to push the Christian message, but rather to establish a common link across South Africa’s cultures” (qtd. in Willoughby, “South Africa”).Footnote 8 In treating the biblical stories of the cycle as a “common link” across the racial, linguistic, and socioeconomic divisions within South African culture, Dornford-May’s turn to the medieval mystery play tradition recognizes and embraces the prevalence of Christianity in South Africa. Beyond its biblical content, the Middle English of the original Chester text offered a way to decenter modern English as the language of the colonizer; in Dornford-May’s words, “The fact that no one culture starts with an advantage in this production is underscored in language.” During the early weeks of workshopping with the newly formed ensemble, the performers recited the text in the original Middle English in order to establish a common ground of mutual alienation from the language: no one initially approached the text in their native tongue. Only after a period of establishing this “even plane and [getting] clarity on the story” did the ensemble collectively choose the languages that would be used in the production, with each performer delivering their lines in their native tongue. As a result, the performance featured a mix of modern English, Xhosa, Afrikaans, Zulu, and Sotho while retaining elements of the original text’s Latin and Middle English. This heteroglossic approach to language laid the groundwork for the theatrical syncretism that would come to define the production as a whole, as well as Isango’s ongoing artistic work.Footnote 9

Before mapping the various production elements that characterized Yiimimangaliso’s postcolonial, syncretic aesthetic, I want to explain my use of the conceptual framework of “theatrical syncretism.” I draw on Christopher Balme’s definition of theatrical syncretism as a decolonizing strategy that “utilizes the performance forms of both European and indigenous cultures in a creative recombination of their respective elements, without slavish adherence to one tradition or the other” (9). In distinguishing between syncretism and theatrical exoticism, Balme’s argument maintains a strict dichotomy between European and indigenous positionalities on the part of artists. I resist this binary, which risks flattening the positionalities of artists, obscuring various forms of intersectional postcolonial identity. As the South African performance scholar Loren Kruger has argued, “Insisting on authenticity or an absolute difference between European and African, imported and indigenous, literary and oral, threatens to repeat the neocolonial essentialism that it purports to critique” (Drama 18). I accordingly read Yiimimangaliso’s theatrical syncretism through Kruger’s redefinition, which frames the syncretic as “an ongoing negotiation with forms and practices, variously and not always consistently identified as modern or traditional, imported or indigenous, European or African” (20).

Through its “ongoing negotiation” of language, drawing on the Middle English Chester text, Yiimimangaliso’s heteroglossia became the central underlying principle of the production’s syncretism. As Theresa Coletti has observed, the production’s use of multiple languages recaptures the heteroglossic aspect of the original medieval mystery cycle tradition, one that is absent from the majority of contemporary medievalist productions:

The acknowledgment of linguistic difference that we encounter in the Chester plays, which strategically employ Latin and French alongside [Middle] English, both provides precedent for the sliding between languages that is on display in the South African Mysteries and signals the important cultural inflections that accompany uses of the vernacular in both historical contexts. (278)

In tandem with its heteroglossia, the production supplemented its verbal meaning-making through nonverbal modalities, using dance, song, and movement to communicate the biblical narrative. As Dornford-May stated in a 2001 interview, “Because everyone knows the story of Noah and the Flood or Abraham and Isaac, we could allow the freedom of expressing these stories in all these languages” (qtd. in “Mysteries”). In other words, audiences were able to grasp the meaning of the heteroglossic dialogue through their familiarity with the biblical text conjoined with the dynamic interplay of nonlinguistic performance elements. In this way, the production functioned affectively rather than discursively, and particularly through music.

Song features heavily throughout the production, and more than one reviewer has called it “musical theater,” though it can more aptly be said to follow the long tradition of township musical performance.Footnote 10 Central scenes—including God’s creation of the world and Adam and Eve, Noah and the Flood, the Annunciation of Mary, the Slaughter of the Innocents, Lucifer’s temptation of Christ, Christ’s raising of Lazarus, and the Resurrection—are enacted through song.Footnote 11 The musical director, Charles Hazlewood, described in an interview how he gathered a “library” of songs from distinct South African traditions, including Dutch folk songs, Zulu lullabies, Xhosa war chants, and Latin hymns, which were then interwoven throughout the show (Township Opera). In a scene that was widely praised in reviews, the company performs a syncretic version of “You Are My Sunshine” when Noah’s ark arrives safely on land, featuring the four-part harmonies that are characteristic of township gospel choirs. God then appears and joins the song, playing a township-style instrument made of a glass soda bottle. Yiimimangaliso’s final scene closes with the entire ensemble gathered onstage in a collective song and dance: the song is the traditional Xhosa melody “Intonga,” which The Times described as “the sort of song that could make anyone think they have died and gone to heaven” (Rees). While “Intonga” is a canonical Xhosa retreat song, Coletti observes that its lyrics resonate with the theme of resurrection that ends the play: “Elan e twasa lhobo; la ku phumele da bene yo! Ku ba ku bet w’intonga; Yo!” (“The sun is rising. It is a new day. Go forth in peace”; 281). Throughout the performance, the ongoing interactions between God and humanity are marked by music, so that God’s relationship with humankind emerges as a continuous song featuring different characters, participants, and episodes. The sonic backdrop of the production is constant and atmospherically pervasive; in the words of one South African reviewer, “unconventional instruments, normally associated with anything but music, are used to generate what can be described as heavenly noise” (Phosa). The instruments used are in fact staples of black township musical performance: upturned rubbish bins, penny whistles, oil drums, tires, bottles, and voices. This soundscape works together with the production’s other nondiscursive elements to produce an affectively charged, “heavenly” atmosphere.

Yiimimangaliso also draws on traditional indigenous dance modalities to supplement its heteroglossic syncretism. While song is performed throughout by individuals and the ensemble as a whole, dance functions almost exclusively to indicate key moments in the narrative. God dances with his angels during the creation of the world, using gestures that evoke a sense of calling forth order out of chaos (see fig. 1). Later, Christ’s incarnation as man is signified by a dance between Mary and God that is distinctly reminiscent of South African gumboot dancing, featuring an intricate clapping rhythm.Footnote 12 Mary demonstrates to God, who is dressed in ornate tribal garb, a complicated rhythm of clapping and stomping; God attempts to repeat the dance but fails in a moment of comedic humility. Mary demonstrates again, and God fails again. Finally, in order to perform the dance, God removes his ornate garments, revealing tattered jeans and sandals underneath. Only then can God (now as Christ) perform the dance of his earthly mother. The simplicity of this moment—and its insertion as material extraneous to the biblical text—enacts the incarnation of God as Man.

Fig. 1. Vumile Nomanyama as God in Yiimimangaliso: The Mysteries. Screenshot from 2005 Heritage Theatre / BBC recording.

Soon after this moment, Jesus chooses his followers, calling them into discipleship by teaching each one the same gumboot dance individually. In a rare acknowledgment of the multiraciality of the cast, the only disciple played by a white actor struggles to replicate the complicated rhythm, shaking his head at his own (white, it is implied) rhythmic ineptitude.Footnote 13 The dance and its increasing elaborations throughout the production form an embodied, kinesthetic motif, tracing the incarnational encounter between humanity and the divine. The dance is recapitulated in the penultimate scene of the play, which stages Chester’s Pentecost episode. Following the death of Christ, the disciples enter the bare stage in silence. One of the disciples attempts to show Peter the complex, rhythmic clapping dance that God-Christ has performed throughout the play. After multiple attempts, and without speaking, Peter and all the disciples master the dance and perform it in unison. They break into song and dance as the back of the stage is lit with tongues of flame to signify the coming of the Holy Spirit. At this moment, Christ—now recostumed as God to signify his resurrection—enters the stage from a central thrust platform to lead the dance. Increasing in pace, the dance encompasses the entire playing space, and the full ensemble ultimately joins in to represent the spread of the gospel throughout all the nations (as delineated in both the Chester text and its source material in the book of Acts). With the entire company onstage, the gumboot dance transmutes into a victorious dance whose movements echo the toyi-toyi, the canonical dance of anti-apartheid protests. Coupled with the victorious Xhosa song “Intonga,” the dance depicts humanity’s encounter with God as a complex and embodied mode of unification through movement. In the 2001 reprisal of the production (by then an international hit) in South Africa, the then president Thabo Mbeki famously joined the cast on stage to dance in the final moments of the play (Mulkerrins).

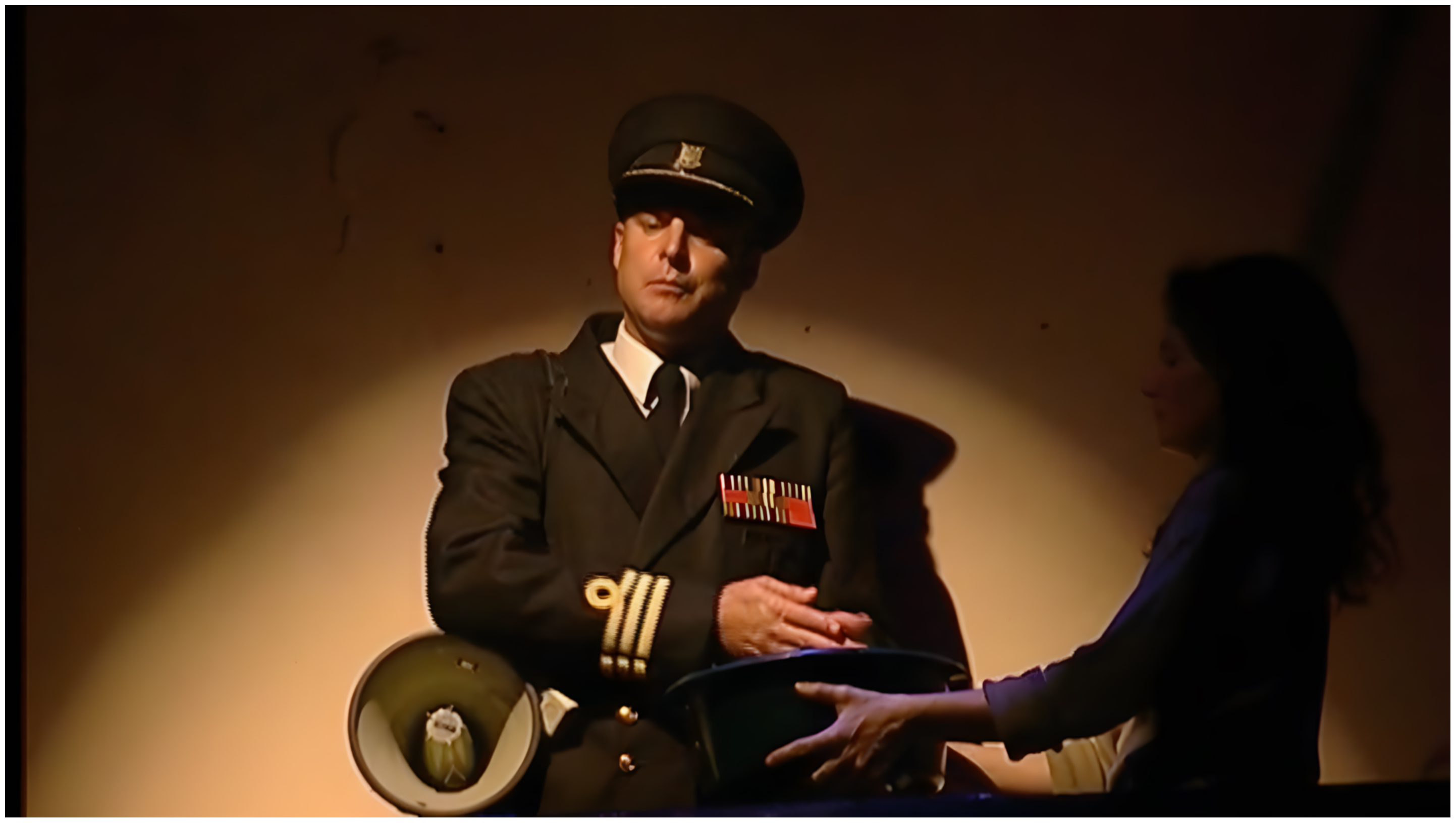

Across these elements, a visual aesthetic of South African indigeneity is prominently featured. The costume design draws extensively on a mix of traditional clothing from across South Africa’s many indigenous tribes as well as contemporary dress associated with township life. In general, the divine characters—God and his angels—are clothed in vibrant and intricate tribal garments, while the human characters wear a mix of traditional and contemporary African clothing. At key moments, the contemporaneity of the dress has special significance; the sex worker whom Jesus saves from an angry mob is in a red dress and adorned with bangles, while Pontius Pilate (played by a white actor) is dressed as a colonial military leader (see fig. 2). In contrast, characters associated with rurality (such as the shepherds in the Nativity story) or with tribal authority (the Magi) are dressed in traditional African garb, while the threatening King Herod is styled as a military junta leader associated with figures of African dictatorship.

Fig. 2. Pontius Pilate styled as a colonial military leader in Yiimimangaliso: The Mysteries. Screenshot from 2005 Heritage Theatre / BBC recording.

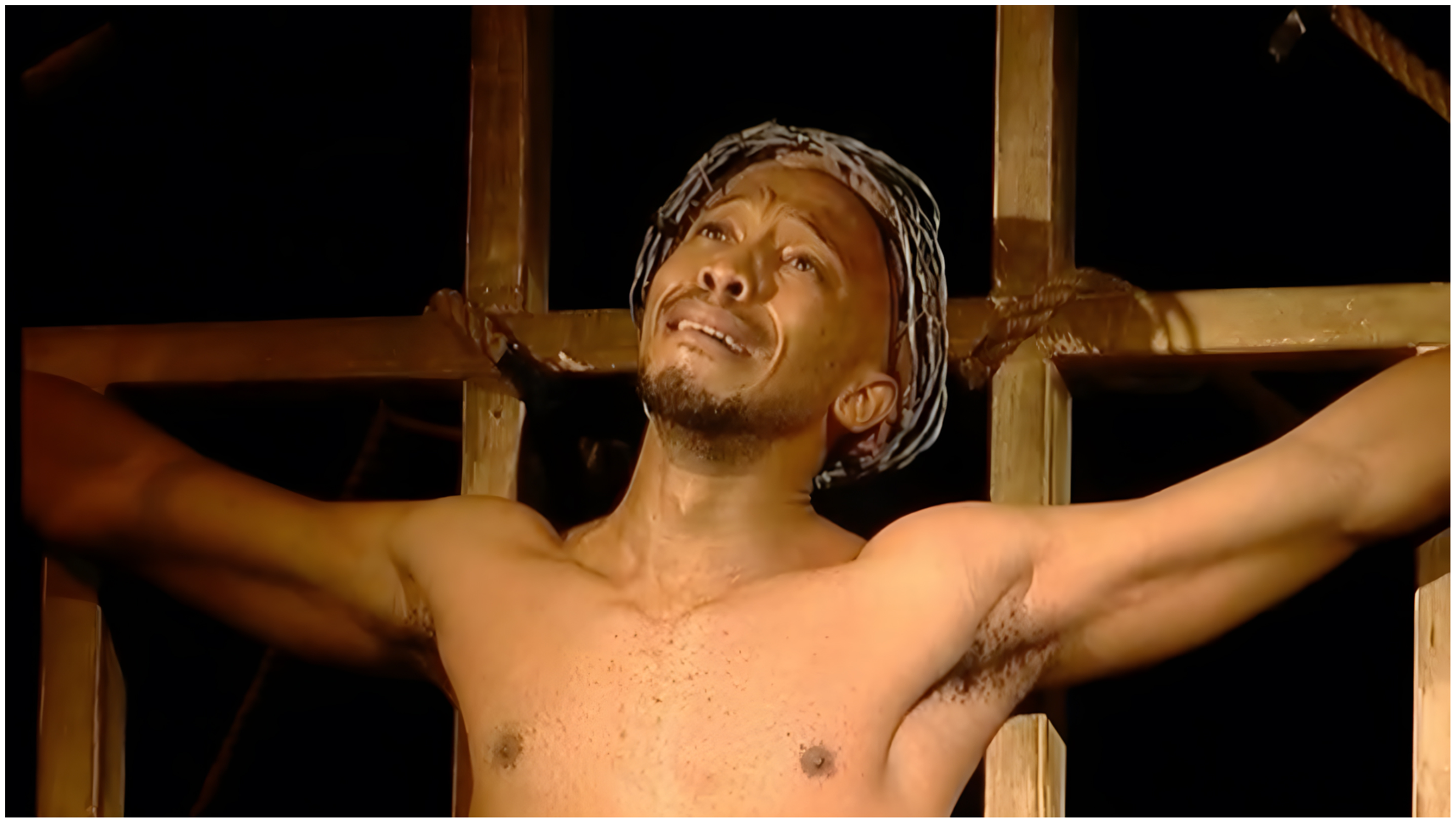

Such visual references extend beyond costume design, providing other forms of allusion to black South African culture. In place of the biblical account of stoning, Yiimimangaliso’s sex worker is threatened with necklacing (see fig. 3), a form of “people’s justice” carried out in black townships upon collaborators with the apartheid government (Buur and Jensen 150n12). The gifts given by the shepherds to the infant Jesus are also distinctly South African: a gourd and a penny whistle, both associated with the popular kwela music of the 1950s. Jesus is later crowned with a ring of barbed wire, rather than a crown of thorns, in a clear reference to the barbed wire gates and walls found in affluent districts in South Africa’s urban centers (see fig. 4).

Fig. 3. The Woman Caught in Adultery episode staged with necklacing in Yiimimangaliso: The Mysteries. Screenshot from 2005 Heritage Theatre / BBC recording.

Fig. 4. Christ’s Crucifixion with barbed wire crown in Yiimimangaliso: The Mysteries. Screenshot from 2005 Heritage Theatre / BBC recording.

Heralded in the United Kingdom and the United States as “visionary” (Hitchings, “Exhilarating Sensory Feast”) and “dazzling” (Spencer), the production’s syncretic pairing of a medieval mystery cycle with South African music, dance, and costumes was praised as a refreshing approach to the Middle English Chester text. Margo Jefferson wrote for The New York Times, echoing Balme’s distinction between syncretism and exoticism:

[The production has] taken a huge leap past the usual conventions about how Western and non-Western styles should meet.…We are all too familiar with the old pattern by which some classic work is injected with the style serum of a culture assumed to be earthier, more sensual and less intellectual and therefore able to reach the audience with its primal force, or at the very least its openhearted warmth and vibrant energy.…Nothing could be farther from the path taken by the D.D.K [Dimpho di Kopane] directors, actors, and choreographer. Two sets of performance traditions meet. They alter and enhance each other.

Because the production blended “two sets of performance traditions,” its success was also couched in political terms. Described in The Times as “an ideal ambassador for the new South Africa” (Rees), Yiimimangaliso’s syncretic, decolonial aesthetic was framed by reviewers as enacting the new political ideal of Rainbow Nationhood, offering proof that “black, white and ‘colored,’ or mixed-race, South Africans could work together on an equal footing” (Riding). South Africa had been an international pariah for the final decades of apartheid, as the racial atrocities perpetuated under the apartheid regime triggered global censure in the form of resolutions of the United Nations, trade embargoes, and widespread anti-apartheid movements across the world. Against this history of violent racial oppression, Yiimimangaliso’s Western reviewers credited the play with effectively countering “all the gruesome stories about South Africa that circulate in the media” and ultimately serving an “affirmative purpose” by staging “an affront to the prejudices fermented both within and around 21st century South Africa” (“South Africa’s Champion”). Such descriptions converge on the perceived political efficacy of the production: in this interpretation, Yiimimangaliso served not only to showcase South African culture and talent but also to repair the country’s reputation abroad. Benedict Nightingale of The Times defines this political efficacy as a form of reconciliation: “It’s a celebration of healing, wholeness, togetherness: South African, human, universal.” In this way, Yiimimangaliso’s syncretic “celebration of the linguistic and cultural plurality of modern South Africa” (Hewison) was read as politically reflective of South Africa’s postapartheid efforts at reunification, reconciliation, and forgiveness.

Ubuntu, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and Yiimimangaliso’s Racial Politics

This reading of political efficacy on the part of audiences and reviewers, however, was eschewed by academic critics. While praising Yiimimangaliso’s “poetic language, good singing, music, drums and dancing,” Betsy Rudelich Tucker’s 2002 review for Theatre Journal criticizes the production as “politically naïve” (305). Stephen Kelly extends this critique in a 2012 article, characterizing the production as “childishly festive” and disengaged from “contemporary politics” (72) in its (lack of) engagement with race:Footnote 14

Ironically, in such a self-consciously multiracial theatre company, race is all but erased in the fictional world of the play; black and white characters play brothers and sisters, fathers, mothers, and sons and daughters, all the while explicitly negating race as a key characteristic of identity…. [Reviewers’] assessment of the play is adumbrated by an implicit sense of their own liberal political relief and self-satisfaction with recent historical events in South Africa. Yiimimangaliso is…a cipher for the fulfilment of an easy Western cosmopolitan fantasy of a deracinated South Africa. (73)

Tucker’s and Kelly’s readings center anxieties like Balme’s about the threat of theatrical exoticism inherent in the Western consumption of multiculturalism. But such readings also betray a privileging of Western audience reception—indeed, the 2000 premiere was read by its predominantly white South African audience as racially controversial—as well as an ignorance of the political context of the project of nation building that surrounded Yiimimangaliso’s inception and production in the aftermath of apartheid. By briefly contextualizing Yiimimangaliso within the political climate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and Mbeki’s presidency, I reread the production’s racial politics; instead of being “politically naïve,” Yiimimangaliso enacts the politicization of the indigenous value of ubuntu in service of the goal of “building a shared nationhood in this new democracy” (Dornford-May, “Working”).

A Bantu value that preexisted colonialism, ubuntu has been described as a form of “African humanism” that functions as a philosophy of “shared humanity” (Praeg 11, 15). Often translated as “humanity” or “humaneness,” the concept is encapsulated by the South African aphorism “people are people through other people” (Bongmba 299). As Phillip Zapkin’s 2021 article puts it, ubuntu formulates the self through its inherent relationship with others. As a philosophical practice and enacted ideal, ubuntu operates at the level of a social contract in which those who do not live by its principles can lose their humanity. One’s humanity, in a sense, is earned or performed through the practice of ubuntu as an embodied philosophy.

After the fall of apartheid and the beginning of South African democracy in the mid-1990s, ubuntu was transformed from a precolonial, indigenous moral value into an ideological tool for nation building. In their postapartheid call for forgiveness and reconciliation, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu championed ubuntu as the mode by which South Africa would heal as a nation and form a newly unified identity, deeming it a “model for redefining terms of inclusion in this historically divided country” (Hutchinson 137). At its establishment in 1995, the TRC claimed ubuntu as its defining philosophy, citing “the need for understanding but not for vengeance, a need for reparation but not retaliation, a need for ubuntu but not for victimization” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission 8). As the chairman of the TRC, Tutu articulated a formulation of ubuntu interwoven with Christianity in a syncretic approach to forgiveness that was heralded by theologians and scholars of religion as “ubuntu theology.” Pointing to the Bible, Tutu described ubuntu repeatedly as a value of interdependence that had the potential to heal the wounds of apartheid: “Apartheid…says people are created for separation, people are created for apartheid…for alienation and division, disharmony and disunity; we say, the Scripture says, people are made for togetherness, people are made for fellowship…that is to say, you and I are made for interdependency” (qtd. in Battle 178). As Michael Battle, a scholar of black theology, observes, Tutu presents ubuntu as “a form of relational spirituality” that counters “godless systems of justice that encourage a high degree of competitiveness and selfishness.” In this way, Battle argues that Tutu’s use of ubuntu advances an “African epistemology” that “begins with community and moves to individuality,” rejecting a “Western epistemology which moves from individuality to community” (178).

Tutu’s coupling of ubuntu and the Christian ideal of forgiveness form a distinct syncretism (in the original, religious sense of the term)Footnote 15 that is strategically aimed at nation building within the postcolonial and postapartheid context. Instead of relying exclusively on Christian rhetoric and ideologies, Tutu drew on an indigenous African ideal, hybridizing it with popular Christian values to create what the cultural studies scholar Hanneke Stuit calls a “reinvented tradition” (26). This new syncretic form of ubuntu—as both an indigenous value and a Christian responsibility—functioned as “the African philosophy that animates the core of South Africa’s TRC” (Cole, Performing 162). In this context, ubuntu informs Yiimimangaliso’s celebration of Rainbow Nationhood, which was lauded by reviewers but criticized by scholars like Kelly as merely deracinated multiculturalism. Instead of paying lip service to South Africa’s multiculturalism, the concept of Rainbow Nationhood as it was valorized by Mbeki in the early 2000s draws on the “relational spirituality” of ubuntu as the dominant ideology of the postapartheid policies issued by the newly democratic government.

In his oft-cited 1996 speech “I Am an African,” Mbeki interpellates his audience into a range of racial and ethnic identities, using the first person to identify himself in turn with the indigenous Khoi and San tribes, European colonial migrants, Malay slaves, Boer farmers, and Xhosa and Zulu warriors. With this strategy, he combines them into a singular, transcendent South African identity that forms the aspirational foundation of the new nation. Yiimimangaliso’s multiracial casting mirrors the comprehensive political messaging of the Mbeki presidency and the TRC. In other words, the production’s elision of racial difference is not “politically naïve” but rather highly politically motivated: as a celebration of common humanity through the syncretic aesthetics of postcolonial performance, Yiimimangaliso’s flattening of racial difference is a strategic, political choice that emerges from the predominance of ubuntu within contemporary discourses on reconciliation, democracy, and new nationhood.Footnote 16

Racial Animatedness and Spiritual Efficacy in Yiimimangaliso

While this understanding of ubuntu’s centrality at the time of Yiimimangaliso’s creation sheds light on the production’s multiculturalism, I am not suggesting that race functions neutrally in Yiimimangaliso’s laudatory reception. The production’s initially controversial reception in South Africa demonstrates that its domestic audience perceived the show as highly raced. But, to return to the question that animates this essay, Yiimimangaliso’s purported ability to “fill a hole in the soul” for British audiences is fundamentally imbricated with the consumption of race in its performance. While scholars like Kelly often focus on the exoticism that accompanies Western consumption of non-Western, black performance, Yiimimangaliso’s disparate receptions and efficacies (both spiritual and political) manifest in ways that go beyond mere exoticization and the flattening of black experience.Footnote 17 Rather, the production’s racialized reception engages what Ngai has termed “animatedness,” a perceptual practice that performs a distinctly raced notion of “authenticity” (95). In the case of Yiimimangaliso, this practice reanimated a notion of the medieval in highly spiritualized terms among the production’s Western spectators.

Before engaging directly with Ngai, I want to situate her work in relation to modern phenomenologies of race and their antecedents in medieval Europe. Scholars like Geraldine Heng and M. Lindsay Kaplan, among others, have offered crucial reappraisals of ideologies of race in medieval Europe as part of the larger turn within medieval studies toward considerations of the Global Middle Ages and antiracist scholarship. Heng’s 2018 monograph The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages moves away from conceptualizing race in the medieval period as either absent (as an exclusively modern construction) or solely localized in the body. Rather, Heng’s articulation of race aligns with conceptions of race as an intersubjective phenomenon; in her words, “race has no singular or stable referent…race is a structural relationship for the articulation and management of human differences” (19). The work of scholars like Heng and Kaplan, however, includes a critical aspect that is absent from the modern phenomenologies of race I discuss below: religion. “Religious race” describes the racialization of subjects who fell outside medieval Christendom (Heng 20).Footnote 18 As Heng observes, religion in the medieval period functioned “socioculturally and biopolitically: subjecting peoples of a detested faith…to a political theology that could biologize, define and essentialize an entire community” (3). The hegemony of Christianity in medieval Europe thus functioned as a critical component in race making. I suggest that religious race—as both a medieval and a medievalist concept—is invoked through the phenomenology of racialized spectatorship in Yiimimangaliso’s spiritualized reception. If religious difference was racialized in the European Middle Ages, race, I argue, is being religionized in the secular West’s consumption of Yiimimangaliso. This inversion illuminates the ongoing imbrication of religion and race that traces back to racial formation and race making in the medieval period itself.

In Ugly Feelings, Ngai describes a range of “minor affects,” including the “racialized affect of animatedness” read onto racialized subjects (8, 9).Footnote 19 She defines animatedness as “the kind of exaggerated emotional expressiveness…[that] seems to function as a marker of racial or ethnic otherness” (94). While Ngai notes that animatedness has been applied to a range of differently racialized subjects, she analyzes its ongoing legacy in particular relation to black subjects. The attribution by the Western gaze of “the affective qualities of liveliness, effusiveness, spontaneity, and zeal” to black bodies points to “a disturbing racial epistemology, and makes these variants of ‘animatedness’ function as bodily (hence self-evident) signs of the raced subject’s naturalness or authenticity” (95). As a perceptual practice manifesting as racialized affect, animatedness invites a phenomenological reading as modeled by scholars of the phenomenology of race. Drawing on Frantz Fanon’s canonical account of being hailed as a “Negro” through the white gaze, scholars such as Helen Ngo, Sara Ahmed, and Linda Martín Alcoff have demonstrated how racialization functions as a preconscious perceptual practice within the visual sphere. Applying Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s formulation of perception, Alcoff argues that his “concept of the habitual body—a default position the body assumes in various commonly experienced circumstances that integrates and unifies our movement” is useful for understanding “how individuals fall into race-conscious habitual postures in cross-racial encounters” (18). For Alcoff, race manifests as a “structure of contemporary perception” that results from “sedimented contextual knowledges” that are “congealed into habit” and activated by the gaze (20, 18, 21). In this way, visual perception unconsciously accesses learned racial knowledges:

This is why race must work through the visible markers on the body, even if those markers are made visible through learned processes. Visible difference, which is materially present even if its meanings are not, can be used to signify or provide purported access to a subjectivity through observable, “natural” attributes, to provide a window on the interiority of the self. (24)

Aligning with Ngai’s articulation of animatedness as signaling expressive “authenticity,” Alcoff’s phenomenological argument frames race as a visible bodily marker that is perceived as providing access to “the interiority of the self,” reifying racialized attributes and stereotypes as natural or authentic.

Through the rhetoric of “animatedness,” both the South African and the British receptions of Yiimimangaliso testify to the spectatorial perception of such racialized authenticity, albeit to radically different ends. While in the British press it was lauded as spiritually convicting, the perceived authentic animation of the performers was disparaged by South African critics. Though South African critics avoided discussing the cast’s race directly in reviews, their response converged on a racialized critique of what they perceived as the black cast’s tendency to “overdramatize the story” through “histrionic” performances (Phosa; Apthorp). The South African reviewer Robert Grieg deemed the production “amateurish,” accusing the performers of a lack of “craft” due to “economic reasons”; here “economic reasons” (or, as other critics put it, the performers’ coming from “disadvantaged communities”; Graham; Le May) can be read as code for the performers’ blackness. Grieg suggests that as black subjects, these artists are in fact not performing but are authentically “overemotional” (Ngai 91).

The South African response to Yiimimangaliso, unlike the British reception, did not read the production as efficacious in terms of rehabilitating the Christian narrative for its domestic audiences. Though the show was racialized through the rhetoric of animatedness, Yiimimangaliso’s efficacy for its South African spectators operated in political rather than spiritual terms. The dismay of the audience members at the “Africanization” of the Spier Arts Festival reveals the anxiety of white South African spectators during the aftermath of apartheid’s recent collapse. While British spectators were dissociated from the specific realities of South Africans’ shifting sense of national identity, South African spectators—already imbricated in the nexus of Mbeki’s national policies—betrayed their discomfort with the new political reality of Rainbow Nationhood. Far from being perceived as apolitical (as Tucker and Kelly hold it to be), the production elicited a negative reaction from South African critics and audiences alike that testifies to its politicized reception. In fact, the negative response from these audiences illuminates how politically efficacious Yiimimangaliso was in reflecting the tensions that accompanied South Africa’s attempts to build a postapartheid national identity.

In stark contrast to the South African response, British reviewers acclaimed many of the same animated qualities disparaged by the South African press, repeatedly turning to the rhetoric of animatedness by praising the cast as “vital” (Spencer; Lang; “South Africa’s Champion”) and full of “energy.”Footnote 20 As Ngai notes, terms like “energy” acquire specifically racialized overtones in regard to the “metamorphic potential of the animated body.” Ngai cites Rey Chow’s contention that through the racialized gaze, the qualities of the racially animated body become “readable as signs of the body’s utter subjection to power, confirming its vulnerability to external manipulation and control”; this exaggerated corporeality of “the body-made-spectacle” echoes the long lineage of the black body as a site of spectacular performance for the white gaze (101). The repetition of adjectives like “raw” (Carpenter), “fresh” (Nightingale; Hitchings, “Magical Mysteries Tour”; Hemming), and “pungent” (Hitchings, “Exhilarating Sensory Feast”) invoke the sensory language of taste and smell, contributing to an impression of spectatorial consumption of the performance. In his Evening Standard review, Henry Hitchings refers to Yiimimangaliso as a medieval mystery cycle “with a zestily contemporary South African tang,” exemplifying the representation of South African aesthetics as a sensory feast for the palate of predominantly white British audiences.Footnote 21

It is this racialized consumption of animatedness that underpinned what spectators perceived as the production’s religious authenticity and, ultimately, its spiritual efficacy. As Ngai argues, reading a racialized subject’s “naturalness or authenticity” serves to reinforce “the notion of race as a truth located…[in the] visible body” (95). This sense of religious authenticity was invoked especially by critics’ use of a rhetoric of joy. Michael Billington wrote in The Guardian that audiences witnessed “not just a well-drilled company but an expression of communal joy” (“Mysteries—Yiimimangaliso”). The contrast between this “expression of communal joy” and the mechanical image of a “well-drilled company” not only implies an authenticity behind such joy but also distances the production from theatrical representation itself: if a “well-drilled company” represents joy on stage, Billington suggests, Isango expresses and embodies joy. Spencer similarly describes the production not only as “full of joy” but also as “heartfelt,” suggesting a blurred distinction between representation and authentic expression. Billington reiterates this idea of performed emotion as sincere and authentic in his 2009 review of the production’s second UK tour. In attempting to explain the show’s powerful ability to “raise the spirits,” Billington writes, “Watching the thirty-three actors in this all-black company, I felt that they were telling the story out of inner conviction.…I felt the cast were genuinely rejoicing.…[T]he sincerity of their faith communicates itself to the audience.” Through his rhetoric of genuineness and sincerity, Billington asserts that Yiimimangaliso authentically enacts—rather than represents—the personal religious faith of its performers. Other Western reviewers echoed this assumption of an authentic expression of the actors’ personal faith; one American critic referred to Isango as “a company of true believers” (Stasio). At no point in the show’s run did the creative or marketing teams indicate anything about the personal faith of the performers. The company itself has no religious affiliation, nor have any of its members spoken publicly on the subject of their personal faith. Yet several reviewers nonetheless made the same assertion about the true conviction of Yiimimangaliso’s performers. Why?

In line with Ngai, Alcoff, and other theorists of the phenomenology of race, I posit that Yiimimangaliso’s performers were read as “natural” or “authentic” by Western audiences through the lens of their animatedness, which transmuted their racialized exaggerated expressivity into proof of their “inner conviction.” For these “animated” performers, joy cannot be representational: it must be genuine and natural in its energy and zest. Through the white Western gaze, the performance was perceived as an enactment of faith.

The perception of animatedness as connoting true faith in the performers ultimately produced Yiimimangaliso’s spiritual efficacy for its British spectators through its invocation of the medieval imaginary. Tucker makes this connection explicit, noting the “thoroughly joyful commitment of the multi-colored cast to the text” and their “refreshing faithfulness to the spirit of the Chester text” (304, 305). While she stops short of assigning religious belief to the performers, Tucker reads Yiimimangaliso’s “joyful,” “multi-colored” cast as somehow aligned with the original devotional and doctrinal purposes of the medieval cycle—what she terms the “spirit of the Chester text.” Tucker’s language reveals the racialized reading of Yiimimangaliso’s performers and their perceived authentic performance of faith as reactivating the spiritual efficacy of the original medieval text.

As scholars of medieval temporality have argued, the medieval imaginary emerged contemporaneously with the rise of colonialism, functioning to justify colonial expansion and the subjugation of non-Western peoples and territories through what Candace Barrington terms “temporal global medievalism,” which “uses medievalism to imagine two coeval cultures as occupying two different time zones or historical chronologies. The Western European is considered to occupy the modern ‘now,’ while others [indigenous cultures] are perceived as occupying a medieval ‘then’” (184).Footnote 22 Through the pervasive narrative that portrays both black African bodies and the Middle Ages as distinctly unmodern, Yiimimangaliso’s spiritual efficacy operates through a racialized perception of the Other, both temporally and geographically. In other words, it is the racialized Otherness of Yiimimangaliso’s cast, read through a modern, secular, Western gaze as recapitulating a sincere and authentic sense of Christian faith, that is associated with the Middle Ages. For British audiences, the experience of watching Yiimimangaliso revived the spiritual efficacy of the original Chester text, an efficacy that has otherwise been absent from what Normington and Beckwith observed to be the secular nostalgia that characterizes contemporary British revivals of medieval mystery plays. Instead of functioning as “mournful reminders of an Edenic ‘green and pleasant land’” (Kelly 74) or reducing the Christian narrative to the secularized values of “altruism” and “community” (Normington 80), Yiimimangaliso’s racial alterity evokes for Western spectators the unmodern character of Christian devotion, belief, and faith, causing them to read the performance as authentically religious and spiritually transformative, like the original medieval productions.

This association between the African Other and the medieval unmodern is revealed through the commentary of reviewers who explicitly juxtaposed Yiimimangaliso’s “transcendent faith” with modernity and its presumed association with secularism (Hemming). British critics marveled at the production’s ability to “resonate with a secular audience” (Hitchings, “Magical Mysteries Tour”), “communicate powerfully to a secular audience” (Hitchings, “Exhilarating Sensory Feast”), and create an “excitement that is at once political, dramatic, and spiritual” (“South Africa’s Champion”). Billington’s 2001 review belies an assumption of coterminous sacred/secular and medieval/modern binaries, stating that “even in a secularized society like ours” the production called out a “residual religious instinct.” As “residual,” this “religious instinct” is placed firmly in the unmodern past. Jane Mulkerrins echoes this gesture, declaring Yiimimangaliso “the perfect antidote for the cynicism of modern British life”; here the association between secularity and modernity again betrays the racialized reading of Yiimimangaliso and its black cast as unmodern in their assumed spirituality. Yiimimangaliso’s perceived spiritual efficacy results from the production’s syncretic, decolonial approach to the Chester text rendered through the phenomenology of race as activated by the white Western gaze. In staging ubuntu through the lens of the medieval mystery tradition, Yiimimangaliso’s racial animatedness was read as at once “African” and “unmodern” in its presumed religious devotion and spiritual authenticity. In this way, Yiimimangaliso was perceived as authentically enacting the medieval imaginary for Western audiences, yielding a more spiritually efficacious experience for spectators than perhaps any other recent performance of the Chester Mystery plays.

Twenty-two years after the production’s South African premiere, Yiimimangaliso’s valorization of ubuntu and Rainbow Nationhood signifies differently today; as Catherine Cole observes in her recent book Performance and the Afterlives of Injustice, contemporary South Africa is currently “experiencing profound disillusionment with the unfulfilled promises of Mandela’s Rainbow Nation” (15). Despite the optimism that characterized the immediate aftermath of apartheid’s collapse in 1994, today’s South Africa is plagued by corruption, continued racial injustice, sexual violence, and wealth inequality.Footnote 23 In this way, Yiimimangaliso is a relic of—and perhaps a memorial to—the optimism of the early years of South Africa’s new democracy, with its vision of reconciliation under ubuntu and Rainbow Nationhood. In the light of South Africa’s “suspended revolution” (Habib), Kelly’s critique of the production points to the realization that South Africa’s racial progress has stalled.

In my conversation with him, Dornford-May observed that South African theater has similarly lost its way; with the collapse of apartheid, South African political theater has been superseded by Western touring musicals or else new writing by predominantly white South African playwrights (Interview). In recent years, Isango has sought to carve out a new space in South African theater by featuring black South African writers; their 2018 production of SS Mendi: Dancing the Death Drill is an adaptation of Fred Khumalo’s novel about black South African soldiers in World War I. But the company can only fund such new work with the income earned from international tours for Western audiences. As Dornford-May explains, “We have no public subsidy. So the only way we survive is staging shows abroad.…[I]f we tour twelve weeks a year then we have funding for nearly the whole year” (qtd. in Neuss E-16). In October 2022, Isango premiered its latest adaptation from the Western canon—Scott Joplin’s unfinished opera Treemonisha. In an interview with The New York Times, Dornford-May cited the parallels he hoped to illuminate in transposing the American opera to a South African context: “A lot of the issues in the piece are ones we still face here [in South Africa]…issues of education, of deep sexism. There wasn’t a great leap for us from 1880s America on a plantation to today in a township” (qtd. in Woolfe). As yet, the production has not been met with the demand for an international tour that defined Yiimimangaliso year after year. Yiimimangaliso, in that sense, remains unique in Isango’s repertoire; garnering a spiritualized reception activated by a gaze that connects racial animatedness to medieval aspects of religious race, it remains to date both the company’s most profitable production and a rare example of spiritually efficacious medievalist performance.