Introduction

Poverty remains a pressing global concern, with an estimated 692 million people living in extreme poverty worldwide in 2024 (World Bank, 2024). There is agreement that financial exclusion – i.e., the lack of access to and use of financial services by certain individuals or groups – is a significant barrier to economic opportunity and mobility (World Bank, 2023). The rapid growth of digital financial services has arguably opened new avenues for financial inclusion through Digital Financial Inclusion (DFI), defined as ‘the use of digital financial services to advance financial inclusion’ (Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, 2016). DFI involves not only the expanding access to digital financial tools but also the intensity and diversity of their usage in digital financial services, ensuring affordability for users and sustainability for providers (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wang, Wang, Kong, Zhang and Cheng2020). As a result, it has the potential to reduce transaction costs and enhance financial resilience for underserved populations. By promoting access to entrepreneurial resources, DFI can stimulate job creation and wealth generation, offering a sustainable pathway to poverty alleviation (Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan, & Uras, Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018; Goldstein, Jiang, & Karolyi, Reference Goldstein, Jiang and Karolyi2019; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016). DFI is also important because traditional aid-based approaches to poverty alleviation have yielded mixed results, and this makes entrepreneurship a promising strategy for empowering individuals and communities to lift themselves out of poverty.

However, beneath DFI’s promise lies an underexamined tension between its potential for inclusion and its stratifying effects (Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, 2016; Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe1986). Different barriers to digital financial adoption across income classes continue to create disparities in entrepreneurial opportunity exploitation and venture growth through the use of digital financial services (Asian Development Bank, 2017). For instance, upper-income groups, with their superior initial resource endowments in the digital financial era, can better leverage network effects and economies of scale, gaining major advantages in entrepreneurial opportunity identification (World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018; Yue, Korkmaz, Yin, & Zhou, Reference Yue, Korkmaz, Yin and Zhou2022). Besides, regulatory gaps and privacy concerns regarding digital financial services may disproportionately affect vulnerable populations (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Korkmaz, Yin and Zhou2022). These factors may exacerbate regional and individual income disparities, with stronger regions and wealthier individuals benefiting more disproportionately from DFI in their entrepreneurial pursuits. Thus, although many countries (e.g., China) have embraced DFI to promote social inclusion and welfare, a critical question persists: Do different income classes in society benefit differently from DFI?

To explore DFI’s stratified effect, we employ technology adoption and income stratification research as an integrative lens to examine the differentiated impacts of DFI on entrepreneurship. From a technology adoption lens (Rogers, Reference Rogers1965; Venkatesh & Davis, Reference Venkatesh and Davis2000), we conceptualize DFI as the extent to which digital technology is used and integrated in the financial sectors within a region. The literature suggests that digital technology acceptance primarily hinges on individual attitudes and capabilities such as digital literacy and trust in new technology (Chatterjee, Gupta, & Upadhyay, Reference Chatterjee, Gupta and Upadhyay2020; Kim, Shin, & Lee, Reference Kim, Shin and Lee2009), as well as organizational (Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso, & Pino, Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024) and societal factors (e.g., Nguyen & Nguyen, Reference Nguyen and Nguyen2024). In particular, income stratification, where populations in society form lower, middle, and upper classes based on income, serves as a fundamental hierarchical mechanism for analyzing varying levels of DFI adoption (Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe1986; Su, Zahra, & Fan, Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022). Each income class has distinct resource endowments and entrepreneurial patterns (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2017; Su et al., Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022), potentially shaping their adoption of digital financial technology (Kish-Gephart, Moergen, Tilton, & Gray, Reference Kish-Gephart, Moergen, Tilton and Gray2023). Still, despite observable income mobility in developing economies, low-income groups often face a poverty trap and may remain disadvantaged in their technology adoption in the long term (Liu, Mithas, & Saldanha, Reference Liu, Mithas and Saldanha2024). This highlights the need to connect income class with technology adoption when examining the effects of DFI. As Kish-Gephart et al. (Reference Kish-Gephart, Moergen, Tilton and Gray2023: 510) point out, ‘the last decade in particular has seen momentum in social class research, underscoring the relevance of this once understudied yet important topic’. Despite this recognition, however, most studies continue to focus on the aggregate economic benefits of DFI for entrepreneurship (e.g., Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016), often overlooking the question of who benefits.

We further explore how the role of DFI unfolds across various stages of the entrepreneurial process. This comprehensive focus is a departure from prior research that has primarily focused on isolated venture creation stages, resulting in a fragmented understanding of DFI’s comprehensive role in different entrepreneurial stages. Even though studies demonstrate that DFI can boost entrepreneurship by reducing financial constraints (Liu, Koster, & Chen, Reference Liu, Koster and Chen2022) and enhancing venture profitability (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018), concern persists that DFI also introduces potential risks for entrepreneurs that inhibit their ability to create or grow their ventures. For example, the literature shows that indebtedness significantly impairs entrepreneurs’ innovation capabilities and firm performance (Bradley, McMullen, Artz, & Simiyu, Reference Bradley, McMullen, Artz and Simiyu2012), and the ease of access to DFI may worsen this situation, especially among lower-class entrepreneurs who lack financial knowledge and risk awareness (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Korkmaz, Yin and Zhou2022). Hence, understanding these nuanced effects of DFI across the different entrepreneurial stages is crucial for evaluating whether it serves as an inclusive force that creates jobs, generates wealth, and alleviates poverty, or, instead, exacerbates socio-economic inequality.

To address these gaps, we propose a multi-stage model of entrepreneurship to explore how income stratification is heterogeneously influenced by DFI throughout the entire venture lifecycle: entrepreneurial venture creation (Xavier-Oliveira, Laplume, & Pathak, Reference Xavier-Oliveira, Laplume and Pathak2015), entrepreneurial investment (Paulson & Townsend, Reference Paulson and Townsend2004), and entrepreneurial performance (Zhao & Yang, Reference Zhao and Yang2020). This model allows us to examine how DFI influences the relationship between income stratification and the pursuit of entrepreneurship, as well as subsequent entrepreneurial outcomes, a key source of wealth creation that enables people to escape poverty. Furthermore, we explore how DFI works throughout the different entrepreneurial stages by identifying and testing two primary channels: financial literacy (Oggero, Rossi, & Ughetto, Reference Oggero, Rossi and Ughetto2020) and risk preference (Dimmock, Kouwenberg, Mitchell, & Peijnenburg, Reference Dimmock, Kouwenberg, Mitchell and Peijnenburg2016).

Our empirical context is Chinese households. Over the past decade, China has developed a leading digital financial system despite its relatively underdeveloped traditional financial infrastructure. For example, the IMF (2024) reports in its Financial Access Survey that China had only 10.97 commercial bank branches per 1,000 km2, placing it 70th out of 139 countries and regions. In contrast, the World Bank’s financial inclusion survey shows that by 2021, 86.2% of Chinese adults made or received digital payments in the past year, exceeding the average usage rates in upper-middle-income economies (Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, & Ansar, Reference Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer and Ansar2022; World Bank, 2022). The widespread adoption of digital finance in China, compared to traditional financial systems, underscores the need for research in the Chinese context. Furthermore, in his seminal work, Becker (Reference Becker1993) highlights households as a fundamental socioeconomic unit, emphasizing their dual role in both consumption and production. Thus, by focusing on households, we can better understand how technological innovations and social changes (e.g., digital finance) exert profound influences at a granular level.

China has also been proactive in fighting poverty, lifting over 800 million people out of poverty since 1978 (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Chen, Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Chen2021; Si, Cullen, Ahlstrom, & Wei, Reference Si, Cullen, Ahlstrom and Wei2020). The country has eliminated extreme poverty as of 2020, emphasizing economic development, education, and social welfare. China has also invested heavily in infrastructure development, such as roads, bridges, and telecommunications. China’s poverty alleviation programs also include vocational training, microfinance, and social security. In addition, the country’s e-commerce platforms, such as Alibaba, have played a significant role in poverty reduction by providing rural communities with access to markets and financial services. The government has also established a national poverty reduction database to track progress and identify areas for improvement.

Our study makes three contributions. First, we contribute to income stratification theory and entrepreneurship literature by examining the impact of income stratification on entrepreneurial outcomes using a multi-stage entrepreneurial model (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Moergen, Tilton and Gray2023; Liu, Koster, & Chen, Reference Liu, Koster and Chen2022). By framing entrepreneurial activities into three distinct stages (venture creation, investment, and performance), we highlight the nuanced differences between entrepreneurial stages with variant stratifying effects of income class (Navis & Ozbek, Reference Navis and Ozbek2015).

Second, we extend technology adoption research by conceptualizing DFI as a region-level digital technology adoption in financial sectors that affects entrepreneurial behaviors and outcomes across income classes (Huarng & Yu, Reference Huarng and Yu2022; Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Moergen, Tilton and Gray2023; Nguyen & Nguyen, Reference Nguyen and Nguyen2024; Rogers, Reference Rogers1965; Venkatesh & Davis, Reference Venkatesh and Davis2000). Departing from prior studies that acknowledge the inclusiveness of digital financial technology (Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, 2016), we pay more attention to possible structural technology adoption barriers for lower-class households in entrepreneurship (Si, Hall, Suddaby, Ahlstrom, & Wei, Reference Si, Hall, Suddaby, Ahlstrom and Wei2023).

Third, we provide an empirical and contextual contribution by investigating the role of DFI in China, the world’s largest emerging economy (Pattnaik, Ang, & Tang, Reference Pattnaik, Ang and Tang2025). Our study shows that the DFI, vigorously promoted by the Chinese government, presents both opportunities and challenges for alleviating poverty through entrepreneurship. Overall, by providing an integrative analysis of the effectiveness of DFI in stimulating entrepreneurship, our study offers insights into how DFI can foster inclusive growth and poverty reduction in emerging market contexts.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Technology Adoption and DFI

Technology adoption refers to the process by which individuals or organizations accept and use new or improved technologies (Rogers, Reference Rogers1965; Venkatesh & Davis, Reference Venkatesh and Davis2000). As such, adoption is a critical mechanism that drives productivity gains, welfare enhancements, entrepreneurial activities (Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Gupta and Upadhyay2020), and poverty alleviation (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018). At the individual level, technology adoption decisions are shaped by cognitive evaluations, such as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, etc. (Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Gupta and Upadhyay2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Shin and Lee2009). At the organizational level, organizational structure, strategy, and resource availability influence adoption patterns (Capestro et al., Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024). Also, broader societal factors – including cultural values, regulatory frameworks, and infrastructure development – create enabling or constraining conditions that affect adoption trajectories (Huarng & Yu, Reference Huarng and Yu2022; Nguyen & Nguyen, Reference Nguyen and Nguyen2024).

In recent years, DFI, particularly the regional-level adoption of digital technology in financial sectors, has provided a new context for technology adoption research to understand its poverty alleviation effects through entrepreneurial activities (Alvarez & Barney, Reference Alvarez and Barney2014; Si et al., Reference Si, Cullen, Ahlstrom and Wei2020; Si et al., Reference Si, Hall, Suddaby, Ahlstrom and Wei2023; Su et al., Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022). In China, the rapid development of digital technology combined with the widespread usage of mobile phones has accelerated the integration of digital technology with financial services (World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018), making DFI an important technological solution to addressing financial inclusion challenges.

Research suggests that DFI can play a pivotal role in advancing financial inclusion for entrepreneurial endeavors by addressing the limitations of traditional financial systems through digital technology (Apeti & Edoh, Reference Apeti and Edoh2023; Song, Gong, Song, & Chen, Reference Song, Gong, Song and Chen2024; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016; Xu, Zhong, & Dong, Reference Xu, Zhong and Dong2024). First, DFI enhances savings and boosts future consumption and investment (Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016) by offering e-bank services for underserved groups, such as farmers, small and micro-enterprises, and low-income individuals in remote and rural areas (World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018). Second, DFI improves access to credit, allowing individuals and businesses to invest in productive assets and transition from low-productivity sectors, such as agriculture, into higher-productivity sectors such as commerce (Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016). The elimination of geographic barriers expands financial services’ reach to previously neglected communities, making payments more secure and efficient, and encouraging small-scale trade and occupational mobility (Apeti & Edoh, Reference Apeti and Edoh2023). Additionally, fintech innovations that leverage big data analytics enable the development of personalized, affordable financial products, while peer-to-peer (P2P hereafter) lending and equity crowdfunding platforms create alternative credit channels for small businesses previously excluded from traditional financing (Lagna & Ravishankar, Reference Lagna and Ravishankar2022; World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018). Thus, DFI is expected to stimulate entrepreneurial activities, particularly in regions and sectors previously excluded from formal financial services (Huang, Zhang, Li, Qiu, Sun, & Wang, Reference Huang, Zhang, Li, Qiu, Sun and Wang2020).

Despite its benefits, however, critics argue that, while DFI expands accessibility, it does not necessarily ensure inclusivity. Digital financial technologies are not exclusively designed for disadvantaged groups. While lower-income groups gain more access to financial services, middle- and high-income cohorts can also benefit from digital financial innovations tailored to all socioeconomic groups, such as high-credit-limit digital loans, advanced insurance products, and sophisticated investment tools. However, the extent to which individuals adopt digital financial technology depends on their trust in the new technology and the skills needed to navigate it – both systematically weaker among lower-income groups who lack digital and financial literacy (Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Gupta and Upadhyay2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Shin and Lee2009). Even when basic adoption occurs, the depth and quality of adoption often remain constrained. For instance, Fuster, Plosser, Schnabl, and Vickery (Reference Fuster, Plosser, Schnabl and Vickery2019) demonstrate that fintech lending fails to effectively allocate credit to constrained borrowers. Moreover, the inherent adoption risks of DFI, such as data security, privacy concerns, and over-indebtedness, pose challenges for the lower-income group. Unsolicited digital credit offers via mobile phones can lead to excessive borrowing and financial distress (World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018; Yue et al., Reference Yue, Korkmaz, Yin and Zhou2022). Meanwhile, people in remote areas with weak digital infrastructure remain excluded by the financial system and continue to face barriers to accessing digital financial services, representing the ‘last mile’ of DFI (World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018). These risks highlight the need for robust regulatory frameworks that ensure the safety, responsibility, and inclusivity of digital finance.

The double-edged nature of DFI shows a need for a deeper understanding of how it influences entrepreneurial decisions comprehensively. There are two streams of DFI literature related to our study. One examines DFI’s impact on entrepreneurship for certain underprivileged groups, such as impoverished households (Peng & Mao, Reference Peng and Mao2023), females (Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016; Yang & Zhang, Reference Yang and Zhang2022), and migrants (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Koster and Chen2022). The other investigates the determinants of digital financial technology adoption (e.g., Huarng & Yu, Reference Huarng and Yu2022; Nguyen & Nguyen, Reference Nguyen and Nguyen2024). However, there remains a lack of systematic understanding of DFI’s differential effects across income classes and entrepreneurial stages. This undermines our appreciation of DFI as a means of promoting entrepreneurship and alleviating poverty in society.

Income Stratification and the Multi-Stage Model of Entrepreneurship

Income stratification determines the initial resources available to individuals while influencing their attitudes and motivations toward venture creation (Su et al., Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022). Upper-class households, typically equipped with substantial financial and social capital (Kim, Aldrich, & Keister, Reference Kim, Aldrich and Keister2006), are most likely to pursue opportunity-based entrepreneurship. They can leverage their rich financial resources to identify and seize market opportunities, exhibiting stronger risk-bearing capacity (Xavier-Oliveira et al., Reference Xavier-Oliveira, Laplume and Pathak2015). Compared with them, lower- and middle-class counterparts are burdened by resource constraints and market entry barriers, leading them to exhibit lower entrepreneurship rates (Su et al., Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022).

Some research does suggest that lower-class households engage in entrepreneurial activities because they usually have strong self-efficacy, accept vulnerabilities and subsequent risks, and possess a different set of skills and capabilities (De Clercq & Dakhli, Reference De Clercq and Dakhli2009; Su, Song, Lu, Fan, & Yang, Reference Su, Song, Lu, Fan and Yang2023). Yet, trapped by life challenges, they tend to pursue venturing opportunities in the form of informal (Salvi, Belz, & Bacq, Reference Salvi, Belz and Bacq2023) or underdog (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2017) entrepreneurship, rather than formal venture creation (Sutter, Bruton, & Chen, Reference Sutter, Bruton and Chen2019). At the other extreme, middle-class households typically value stability and career promotion and prefer salaried employment over entrepreneurial activities (Banerjee & Duflo, Reference Banerjee and Duflo2008). Together, these observations suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a): Lower-class households are less likely to establish entrepreneurial ventures than upper-class ones, but more likely than middle-class ones.

Research also indicates that income stratification not only influences entrepreneurial venture creation decisions but also affects subsequent entrepreneurial investment (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Aldrich and Keister2006). Lower-class households, typically constrained by a lack of financial resources, are hesitant to allocate these scarce resources to entrepreneurship compared to middle- and upper-class ones (Xavier-Oliveira et al., Reference Xavier-Oliveira, Laplume and Pathak2015). Thus, lower-class households may exhibit a relatively high commitment to entrepreneurship due to their limited occupational choices, leading to low resource investments in entrepreneurial ventures. In contrast, their middle- and upper-class counterparts, with relatively more abundant financial capital and funding sources, can allocate significantly more financial resources to entrepreneurial activities (Cagetti & De Nardi, Reference Cagetti and De Nardi2006; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Aldrich and Keister2006).

The argument we have just presented primarily pertains to the absolute number of investments in entrepreneurial ventures. However, the literature also shows that, driven by the value of upward mobility, lower-class households may allocate their limited resources disproportionately to entrepreneurship, resulting in a higher proportion of entrepreneurial investment relative to their total household assets (Cagetti & De Nardi, Reference Cagetti and De Nardi2006; Perry–Rivers, Reference Perry–Rivers2016). Despite this, these economically disadvantaged households remain constrained by their limited savings and asset base, making it unlikely for them to achieve high levels of entrepreneurial investment (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, McMullen, Artz and Simiyu2012). Overall, these observations suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b (H1b): Lower-class households exhibit lower levels of financial investment in entrepreneurial ventures relative to their middle- and upper-class counterparts.

Focusing on entrepreneurial performance, we suggest that income stratification influences entrepreneurial performance through differential resource utilization capabilities. Lower-class households often face severe cognition and resource constraints, including limited financial capital (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, & Levine, Reference Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine2007), inadequate education, and restricted social networks (Ansari, Munir, & Gregg, Reference Ansari, Munir and Gregg2012). These constraints hinder their ability to scale up their businesses, adopt advanced (e.g., digital) technologies, or access lucrative markets, which results in lower levels of entrepreneurial performance compared to middle- and upper-class entrepreneurs (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, McMullen, Artz and Simiyu2012).

In contrast, upper-class households usually benefit from abundant financial resources, superior education, and extensive social capital. This enables them to invest in high-growth ventures and achieve superior performance (Hurst & Lusardi, Reference Hurst and Lusardi2004). Middle-class entrepreneurs, though better resourced than lower-class entrepreneurs, often lack the financial reserves and social networks of the upper class, leading to moderate levels of entrepreneurial performance. These observations suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1c (H1c): Lower-class households exhibit inferior entrepreneurial performance relative to their middle- and upper-class counterparts.

The Moderating Role of DFI

DFI fundamentally influences whether households pursue entrepreneurial careers and subsequently, how these households devote their resources to entrepreneurial investment and how this influences venture performance. These entrepreneurial processes are interrelated; they are deeply embedded in the rapidly evolving digital technology environment (Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016). DFI has the potential to foster entrepreneurship by increasing accessibility, lowering transaction costs, and alleviating information asymmetries and, as a result, poverty reduction (Apeti & Edoh, Reference Apeti and Edoh2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Koster and Chen2022; Song et al., Reference Song, Gong, Song and Chen2024; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016; Xu, et al., Reference Xu, Zhong and Dong2024).

Specifically, the growing accessibility of digital financial technology is expected to address the barriers that often prevent marginalized households from using traditional financial systems, such as a lack of credit history, collateral, or informal employment; thus, it enables them to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018). The convenience of digital payments also reduces operational inefficiencies across society, assisting underprivileged entrepreneurs in streamlining their business processes at low costs while improving overall performance (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Zhang, Li, Qiu, Sun and Wang2020; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016).

To date, however, the literature has overlooked the differential impacts of DFI across social classes, assuming a one-size-fits-all benefit (e.g., Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Jiang and Karolyi2019; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016). Still, scholars have highlighted how individual, organizational and societal factors determine technology adoption (Capestro et al., Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024; Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Gupta and Upadhyay2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Shin and Lee2009). Applying this lens to DFI, we argue that, for lower-class households, mere access to digital financial services does not guarantee equivalent entrepreneurial outcomes. In what follows, we document adoption barriers that hinder lower-income households from benefiting from DFI in entrepreneurship, particularly compared to their middle- and upper-income counterparts.

Individual-level barriers to DFI adoption manifest through cognitive and behavioral constraints. Low-class households exhibit constrained adoption capacities due to digital literacy deficits, risk-averse attitudes, low trust in new technology and suboptimal resource allocation patterns (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Shin and Lee2009; Yang, Wu, & Huang, Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023). For example, insufficient digital literacy prevents low-class households from navigating complex financial tools, and aversion to risks such as financial loss often discourages investment in high-yield opportunities, resulting in suboptimal scaling of entrepreneurial ventures (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023). Additionally, the ease of access to digital financial technology may create a substitution effect, wherein financial resources intended for entrepreneurial activities are diverted to immediate consumption needs or short-term obligations (Yang & Zhang, Reference Yang and Zhang2022; Yue et al., Reference Yue, Korkmaz, Yin and Zhou2022), further limiting entrepreneurial performance.

At the organizational level, fintech firms that implement stringent user qualifications exacerbate digital adoption barriers for lower-class households. Alternative credit scoring models that rely on non-traditional indicators such as data or mobile usage often fail to accurately reflect the creditworthiness of lower-income individuals, raising borrowing costs and restricting their access to affordable credit (Lagna & Ravishankar, Reference Lagna and Ravishankar2022). Such systems inadvertently reinforce existing inequalities, since those with limited credit histories, poor credit scores, or constrained financial literacy are unable to leverage digital finance effectively for entrepreneurship (Fuster et al., Reference Fuster, Plosser, Schnabl and Vickery2019). Moreover, many digital finance providers prioritize profitability over addressing funding needs for lower-class entrepreneurial ventures, limiting the potential for vulnerable populations to achieve poverty reduction through entrepreneurship (Lu, Zhang, & Li, Reference Lu, Zhang and Li2023).

At the societal level, macro-environmental factors such as infrastructure and regulatory environments influence the adoption of digital financial technologies, presenting greater challenges for lower-income households. For instance, insufficient mobile and banking infrastructure in underserved areas reduces access to digital financial services (World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018). Furthermore, weak regulatory frameworks or limited consumer protection reduce trust in digital finance, disproportionately impacting vulnerable groups (Lagna & Ravishankar, Reference Lagna and Ravishankar2022). These barriers, which have long accompanied traditional financial inclusion initiatives, remain equally pertinent and warrant vigilance in the context of DFI and entrepreneurship.

In contrast, middle- and upper-class entrepreneurial households are better positioned to leverage digital finance for entrepreneurial activities. With favorable resource endowments and creditworthiness, they can access affordable credit and allocate more resources to entrepreneurial venturing (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Zhang, Li, Qiu, Sun and Wang2020), widening the gap in entrepreneurship across income classes. Upper-class entrepreneurs, with their superior background and extensive social networks, can better rely on digital financial resources to scale up their businesses and access high-growth opportunities (Lagna & Ravishankar, Reference Lagna and Ravishankar2022). In essence, for upper-class families who already possess substantial resources, digital finance acts as a resource multiplier. The complexity of digital financial products can disproportionately benefit those with higher financial literacy, typically found in upper social classes, who can navigate these systems more effectively (Asian Development Bank, 2017). Upper-class families can also better navigate complex financial products, leverage alternative credit scoring systems, and combine DFI with existing resources to maximize entrepreneurial opportunities. Meanwhile, middle-class entrepreneurs, while less advantaged than the upper class, still possess sufficient financial literacy and social capital to benefit from DFI, resulting in moderate improvements in entrepreneurial investment and performance (Lagna & Ravishankar, Reference Lagna and Ravishankar2022). They can efficiently leverage DFI as an alternative to traditional financial systems.

To sum up, although DFI is intended to be inclusive, it may benefit upper-class individuals the most across the different stages of the entrepreneurial process, followed by the middle class, with the lower class receiving the least advantage. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): DFI positively impacts (a) entrepreneurial venture creation, (b) entrepreneurial investment, and (c) entrepreneurial performance of lower-class households, with these positive effects less salient than those of middle- and upper-class counterparts.

Methods

Data and Sample

To test our hypotheses, we focus on China, which offers an ideal setting given its rapid entrepreneurial growth (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023) and advanced digital finance development (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., Reference Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer and Ansar2022; World Bank, 2022) in an underdeveloped traditional financial institution environment. This setting allows us to explore how DFI influences different income classes across various entrepreneurial stages.

We collected our data from five sources. We relied on five survey waves of China Household Financial Survey (CHFS) data in 2011, 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 as the starting point for demographic characteristics, household assets, income and expenditures, and household entrepreneurial relevant information. The sampling process of this nationally comprehensive, household-level survey covered 25 provinces and municipalities in 2011 and expanded to 29 provinces and municipalities in the following wavesFootnote 1, ensuring the effective representation of China’s socioeconomic landscape. Recent studies have used the CHFS database to investigate household entrepreneurship (Song et al., Reference Song, Gong, Song and Chen2024) and financial literacy (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023).

We used a second database, the Digital Financial Inclusion Index of China (DFIIC), jointly established by Peking University and Ant Group Research Institute (Guo, Wang, Wang, Kong, Zhang, & Cheng, Reference Guo, Wang, Wang, Kong, Zhang and Cheng2020). Ant Group, the preeminent digital financial services company in China, currently provides the most comprehensive and accurate measures. The DFIIC encompasses 31 provinces (including municipalities and autonomous regions), 337 prefecture-level administrative units, and approximately 2,800 county-level jurisdictions. The amalgamation of digital infrastructure with financial services has improved accessibility, enabling financial inclusion through digital channels in regions previously underserved by conventional banking infrastructure. This database has been used to explore DFI’s effect on rural economic development (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhong and Dong2024) and household financial behavior (Song et al., Reference Song, Gong, Song and Chen2024).

As a third data source, we applied the regional cultural index developed by Zhao, Li, and Sun (Reference Zhao, Li and Sun2015), which draws on a cultural custom questionnaire based on the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) research and is based on a survey of 3,690 participants and five experts from 31 provinces in China. As our fourth data source, we then incorporated provincial-level measures using the National Economic Research Institute Index (NERI) of the marketization index (Wang, Fan, & Yu, Reference Wang, Fan and Yu2017), reflecting regional market development. Finally, for our fifth data source, we gathered provincial GDP per capita data from China Regional and Provincial Statistical Yearbooks (Grohmann, Klühs, & Menkhoff, Reference Grohmann, Klühs and Menkhoff2018) to measure provincial economic fundamentals.

We constructed an unbalanced panel dataset, in which the unit of observation is household-wave, by combining all the above-mentioned databases. We conducted the following sampling procedures in line with existing studies: (1) retaining household heads who participated consecutively in at least two waves of the CHFS database; (2) focusing on household heads aged between 18 and 65 years (Hechavarría, Terjesen, Stenholm, Brännback, & Lång, Reference Hechavarría, Terjesen, Stenholm, Brännback and Lång2018); (3) excluding farmers who are self-employed to avoid biasing our results (Brünjes & Diez, Reference Brünjes and Diez2013); and (4) excluding households that have inherited enterprises or gifted business (Hurst & Lusardi, Reference Hurst and Lusardi2004). Furthermore, we discarded any dependent variable with any missing values through the multi-stages. After dropping observations with missing key variables, we have 36,557 householder-year observations, of which 3,139 (8.59%) report entrepreneurial investment and performance across the different survey waves.

Measures

Entrepreneurial venture creation

Consistent with Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023), our first dependent variable, entrepreneurial venture creation, is a dummy variable based on the CHFS question: [B2000b] ‘Is your family engaged in production and operation of industry and commerce, including individual business, leasing, transportation, online stores, and enterprises’? Given that the CHFS questionnaire varies slightly across waves, all questions referenced here are from the 2015 survey. Specifically, a response was coded as 1 if a household head answered ‘yes’ to this question and 0 otherwise.

Entrepreneurial investment

As noted by Shum and Faig (Reference Shum and Faig2006), investments in private business are risky. Households heavily rely on savings, whether in cash or asset sales, to fund initial business investments. We operationalized entrepreneurial investment as the household’s financial investment in entrepreneurial ventures, calculated by multiplying the total asset value of entrepreneurial venturing projects with the household’s ownership share accordingly. Thus, we used responses to two survey questions: (1) [B2040] ‘How much are the total assets of these projects? Total asset includes project-related shops, cash deposit, stock, office equipment, machinery, means of transportation, etc., but excludes the value of self-owned houses used for these projects’, and (2) [B2051] ‘What is your family’s percentage of shares in the project’? This measurement excludes residential property values to avoid the overestimation of entrepreneurial investment assets (Shum & Faig, Reference Shum and Faig2006).

Entrepreneurial performance

We measured entrepreneurial performance by total business revenue. Following prior studies (e.g., Gruber, Dencker, & Nikiforou, Reference Gruber, Dencker and Nikiforou2024), we calculated this variable as the business revenue or gross revenue generated by entrepreneurial venturing projects, based on responses to the question: (1) [B2052] ‘What was the total business revenue (or gross income) from these projects in the past year or the first half of this year’? and (2) [B2054] ‘What is the profit status of the project last year/for the first half of this year’? Since the business revenue in the first question was taken as an absolute value, we determined entrepreneurial performance by checking the profit status of the project. If the project was operating at a loss, we assigned a negative value to the business revenue.

Income stratification

This set of variables captures the hierarchical economic distribution within society through household income analysis. Specifically, we employed household total earnings (including business revenue, agricultural income, wages, and other sources) divided by the number of family members to establish per capita figures. Following prior research (Su et al., Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022), we established two critical threshold measures. The first is the relative poverty line, set at 60% of the median annual per capita household income of the focal province. The second is the high-income threshold, established at the 90th percentile of annual per capita household income of the focal province, which identifies individuals or households in the top income bracket. Applying these thresholds, we divided the population into three distinct income classes: upper class, middle class, and lower class. This classification system aligns with Stinchcombe’s (Reference Stinchcombe1986) theoretical framework, which emphasizes the interconnection between economic stratification and organizational structures in modern society.

DFI

Consistent with previous studies (Zhang & Pang, Reference Zhang and Pang2023), the moderator, DFI, was calculated to capture the provincial actions that promote financial inclusion through digital financial services. Then, we sourced data from China’s Digital Inclusive Financial Index (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wang, Wang, Kong, Zhang and Cheng2020). The framework features 33 data points examining three core dimensions: coverage breadth, usage depth, and digitalization level. Some empirical evidence suggests that DFI significantly ameliorates entrepreneurial constraints (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023), reducing disparities in entrepreneurial opportunities across different family backgrounds.

Control variables

We also employed an extensive set of control variables to account for potential confounding factors at the individual, household, and provincial levels. The individual-level characteristics are reflected by demographic attributes and human capital indicators of the household head. For demographics, we included age (years from birth to present), gender (1 = male and 0 = female), and marital status (1 = married and 0 = otherwise). In addition, human capital was measured through education (1 = formal education, 2 = primary school, 3 = junior high school, 4 = senior high school, 5 = technical secondary school or vocational high school, 6 = junior college or vocational college, 7 = undergraduate, 8 = master, and 9 = doctoral) and health status (on a 5-point scale, where 1 represents the worst and 5 the best health condition).

At the household level, we controlled for family size (total number of people in the focal family), children ratio (the fraction of children under 16), rural (1 = rural areas and 0 = otherwise), and house owner (1 = owning a house and 0 = otherwise). We also incorporated social network measures, quantified through the total value of cash gifts exchanged during traditional holidays (such as Spring Festival and Mid-Autumn Festival) and life events (including birthdays and celebrations).

Additionally, we employed the marketization index from NERI (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Fan and Yu2017) to assess provincial-level market-oriented reform in China. Higher levels of provincial marketization indicate more developed market institutions in that specific province. We also accounted for geographical heterogeneity in economic development by incorporating regional economic indicators, including GDP per capita from the previous wave to proxy economic development. Finally, we added wave dummies to control for unobserved factors that vary across time. Overall, we standardize the continuous data to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one (Wolfson & Mathieu, Reference Wolfson and Mathieu2021).

Analytical Procedures

Given that two of our dependent variables – entrepreneurial investment and entrepreneurial performance – are only observed for households that engage in entrepreneurial activities, there exists a potential sample selection bias. Therefore, we adopted the Heckman two-stage estimation method to resolve this bias (Certo, Busenbark, Woo, & Semadeni, Reference Certo, Busenbark, Woo and Semadeni2016). In the first stage, we used a probit model to estimate the probability of a household creating an entrepreneurial venture. We then ran Breusch-Pagan Lagrange multiplier tests (Baltagi, Reference Baltagi2001), with all the tests rejecting the null hypothesis and thus suggesting pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for the second stage. All regression models incorporate robust standard errors clustered at the household level, with the independent, moderating, and control variables lagged by one wave.

In the first stage of the Heckman regression, we added future orientation as an exclusion restriction — a variable that affects the selection but does not affect the outcome (Wolfolds & Siegel, Reference Wolfolds and Siegel2019). Following GLOBE’s (House, Javidan, Hanges, & Dorfman, Reference House, Javidan, Hanges and Dorfman2002) definition, future orientation refers to the extent to which individuals engage in future-oriented behaviors, such as planning, investing in the future, and delaying gratification, which impact self-selection into entrepreneurship through linking the past and future and inspiring confidence, yet do not directly affect investment or performance (Ganzin, Islam, & Suddaby, Reference Ganzin, Islam and Suddaby2020). For the second-stage regressions, we followed Su et al. (Reference Su, Zahra and Fan2022) to add the employer variable for controlling for entrepreneur type. A value of 1 represents the household’s entrepreneurial ventures with employees, and 0 otherwise.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations for all variables. In Panel A of Table 1, we find that the lower class, as well as the upper class, has a positive correlation coefficient with entrepreneurial venture creation, supporting H1a. As Panel B shows, among the entrepreneurial households, the lower class generally appears to invest the least in ventures and gain the lowest levels of entrepreneurial performance, supporting H1b and H1c. The variance inflation factors (VIFs) of our variables are below 2.78 and the average VIF is 1.42, which is well below the acceptable threshold of 10. Consequently, multicollinearity does not threaten our analyses (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, Reference Cohen, Cohen, West and Aiken2013).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Notes: SD stands for standard deviation. For Panel A (N = 36,557), correlations with an absolute value > 0.008 are significant at the 0.01 level of confidence. For Panel B (N = 3,139), correlations with an absolute value > 0.046 are significant at the 0.01 level of confidence.

Results

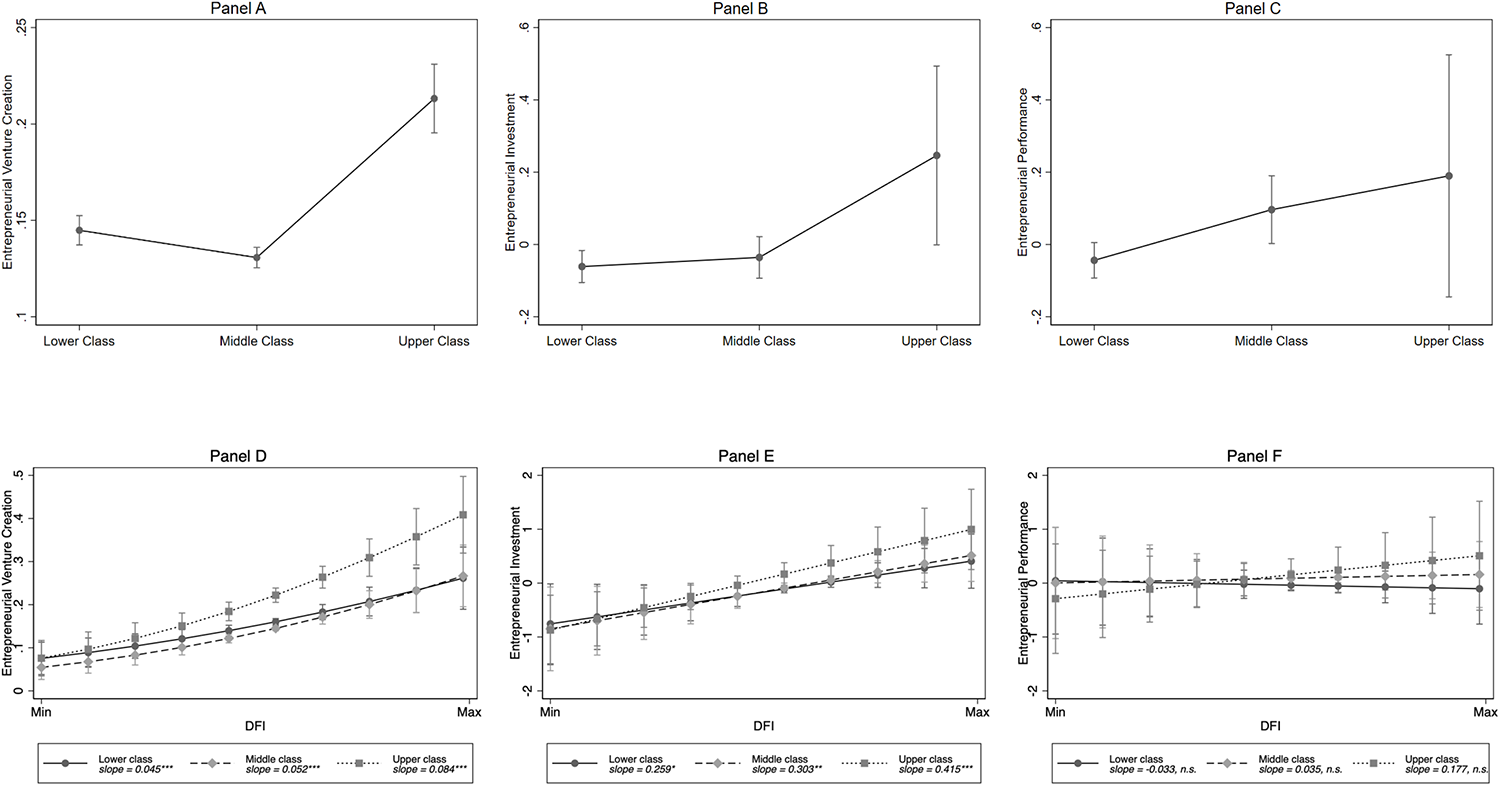

Table 2 reports regression results for the models used to test our hypotheses. Models 1, 3, and 5 are the baseline models that include independent, moderating, and control variables. Models 2, 4, and 6 further add the interaction effect between income stratification and DFI. In Models 1 and 2, we estimate whether a household initiates an entrepreneurial venture using the first-stage Probit model and generate an Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR) as a control for the second stage. As expected, the coefficient of our exclusion restriction, future orientation, is positive and significant (P < 0.01) in Models 1 and 2, indicating that the future orientation dimension of regional culture is positively associated with the likelihood of household venture creation. Importantly, the independent variables lower class and upper class are statistically significant, supporting the potential existence of sample-induced endogeneity (Certo et al., Reference Certo, Busenbark, Woo and Semadeni2016). Models 3-6 of Table 2 report the results of the second-stage regressions for entrepreneurial investment and entrepreneurial performance, using the year-fixed effect. The coefficient of IMR is statistically insignificant in Models 3 and 4 while significant in Models 5 and 6, suggesting that our results are likely to be influenced by selection bias when the dependent variable is entrepreneurial performance and the effectiveness of the Heckman procedureFootnote 2 (Certo et al., Reference Certo, Busenbark, Woo and Semadeni2016). All models in Table 2 report two-tailed tests for non-directional effects and one-tailed tests for the research hypotheses (Cho & Abe, Reference Cho and Abe2013). We also plotted the income stratification effects on entrepreneurial venture creation (Panel A), investment (Panel B), and performance (Panel C) in Figure 1.

Figure 1. DFI and income stratification

Table 2. Main results for hypotheses testing

*,**,*** Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Two-tailed tests for control variables; one-tailed tests for hypothesized effects. P < 0.1, P < 0.05, P < 0.01.

H1a predicts that the likelihood of entrepreneurial venture creation among households from the lower classes is higher than that of middle-class households but lower than that of upper-class households. Model 1 of Table 2 shows that the coefficient for the lower class is 0.064 (p < 0.01), whereas that for the upper class is 0.327 (p < 0.01). In Panel A of Figure 1, upper-class households exhibit the highest inclination toward entrepreneurial venture creation, while lower-class households show a relatively higher probability of engaging in entrepreneurship, compared to middle-class households. Thus, H1a is supported.

In H1b, we predict that entrepreneurial households from the lower class tend to allocate fewer financial resources toward entrepreneurial ventures than their middle- and upper-class counterparts. In Model 3, the coefficients for lower and upper class are −0.025 (n.s.) and 0.282 (P < 0.05), respectively. As Panel B of Figure 1 illustrates, households from the upper class invest more in entrepreneurial ventures than do middle-class households, with no significant difference in entrepreneurial investment between lower- and middle-class households. Thus, the results partially support H1b.

H1c proposes that lower-class households are associated with inferior entrepreneurial performance relative to middle- and upper-class households. In Model 5, the coefficients for lower and upper class are − 0.140 (p < 0.01) and 0.093 (n.s.), respectively. Panel C of Figure 1 indicates an upward trend of entrepreneurial performance with the progression of income classes: lower-class households obtain less entrepreneurial performance than middle-class households, with no significant difference in entrepreneurial performance between middle- and upper-class households. Thus, H1c is supported.

As H2 predicts, DFI increases entrepreneurial venture creation, investment, and performance among lower-class households, although such positive effects are weaker compared to those among middle- and upper-class households. To assess the effects of DFI within each income class, we conducted simple slope tests to assess the statistical significance of the gradients and plotted the moderating effects in Figure 1 (Panels D, E, and F) (Schillebeeckx, Chaturvedi, George, & King, Reference Schillebeeckx, Chaturvedi, George and King2016). Overall, we observe that DFI has consistently positive effects on the likelihood of venture creation in Model 1 (β = 0.233, P < 0.05), entrepreneurial investment in Model 3 (β = 0.317, P < 0.05), and entrepreneurial performance in Model 5 (β = 0.051, n.s.).

In relation to entrepreneurial venture creation, we find a significant and negative coefficient of lower class X DFI (β = −0.045, P < 0.05), along with a significant and positive coefficient of upper class X DFI (β = 0.055, P < 0.05), as shown in Model 2. Consistently, as Panel D displays, DFI exhibits the steepest slope for upper-class households (simple slope = 0.084, P < 0.01), followed by that of middle-class households (simple slope = 0.052, P < 0.01), with lower-class households showing the flattest slope (simple slope = 0.045, P < 0.01). Although regional DFI most strongly facilitates entrepreneurial ventures among high-income families, we can still see a significantly positive effect of DFI for low-income families. Thus, H2a is supported.

Focusing on entrepreneurial investment, Model 4 shows that the coefficient of lower-class X DFI is significantly negative (β = −0.044, P < 0.05), while that of upper-class X DFI is significantly positive (β = 0.112, P < 0.05). Similarly, in Panel E, high levels of DFI in the focal province lead to the greatest increase in entrepreneurial investment for the upper-class households (simple slope = 0.415, P < 0.01), followed by that of the middle-class households (simple slope = 0.303, P < 0.05), with the smallest but significant increase observed for the lower class (simple slope = 0.259, P < 0.1). These results support H2b.

Finally, we look at entrepreneurial performance. Model 6 shows that the coefficient of upper class X DFI is significantly positive (β = 0.142, P < 0.1), while the coefficient of lower class X DFI is significantly negative (β = −0.068, P < 0.01). Even though Panel F shows significant differences in the role of DFI across income classes, the slopes within upper-class households (simple slope = 0.177, n.s.), middle-class households (simple slope = 0.035, n.s.), and low-income households (simple slope = −0.033, n.s.) are not significant. Thus, H2c is partially supported.

Robustness Tests

We also conducted several tests to assess the robustness of our results and gain additional insights. These tests included an exploration of income stratification and DFI’s influence on household income growth, alternative specifications of the moderator, alternative exclusion restrictions for the Heckman two-stage model, subsample analyses with class-stable households and an alternative analytical procedure using OLS estimation.

Exploration of the effects of income stratification and DFI on household income growth

To further examine the poverty-reduction implications of income stratification and DFI, we extended our analysis by incorporating household income growth as an additional dependent variable in the Heckman second-stage model. Income growth was measured by the relative change rate of household income between consecutive waves. The results, presented in Model 7 of Table 2, show that lower-class status is positively related to income growth (β = 0.008, P < 0.01), whereas upper-class status has a negative effect on income growth (β = − 0.008, P < 0.1). This suggests that lower-class entrepreneurial households, starting from a lower base, have greater growth potential than their middle- and upper-class counterparts. Moreover, in Model 8, DFI significantly moderates the relationship between lower class and income growth (β = 0.005, P < 0.05) and its moderating effect is absent for upper-class entrepreneurs, indicating that DFI particularly catalyzes the catch-up process for lower-class entrepreneurial household income.

Alternative measure for the moderator

The CHFS is conducted biennially, which results in temporal gaps. To ensure continuous coverage, we calculated the average DFI between consecutive survey waves as an alternative measure of the moderator. The results remained consistent with our initial findings, providing support for our theoretical predictions.

Alternative exclusion restrictions for the Heckman two-stage model

Following Vasudeva, Nachum, and Say (Reference Vasudeva, Nachum and Say2018), we employed two distinct exclusion restrictions in the first stage of the Heckman regression. First, we extracted provincial-level uncertainty avoidance from Zhao et al.(Reference Zhao, Li and Sun2015), capturing the extent to which society relies on social norms, rules, and procedures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events (House et al., Reference House, Javidan, Hanges and Dorfman2002). Second, we constructed a city-level entrepreneurship ratio to capture the local entrepreneurial climate (Rocha, Carneiro, & Varum, Reference Rocha, Carneiro and Varum2018), calculated as the proportion of entrepreneurial households within the total sampling households in each focal city. The empirical results are qualitatively the same across both specifications of exclusion restrictions.

Subsample analyses with class-stable households

We conducted subsample analyses by restricting the sample to households whose income class did not change during the observation period to avoid the potential influence of income-class mobility. The results are generally consistent with our main findings.

Alternative analytical procedure using OLS estimation

Our analysis of the effectiveness of the Heckman procedure indicates that an OLS approach is suitable for the entrepreneurial investment stage, while the Heckman procedure is more appropriate for the entrepreneurial performance stage. Accordingly, we replicated the regression in the second stage of Heckman using an OLS approach (i.e., without IMR). The findings are consistent with our main analysis, further supporting our main results.

Tests of Potential Channels

The empirical analyses revealed that while DFI facilitates venture creation and increases entrepreneurial investment for lower-class households, such facilitating effects pale in comparison to its support for entrepreneurial activities among middle- and upper-class households. In this section, we further identify two mechanisms through which income stratification and DFI may influence household entrepreneurship. The first is financial literacy, which encompasses the understanding of risk diversification, inflation, interest rates, and compound interest, and has been documented as promoting entrepreneurial activities (Oggero et al., Reference Oggero, Rossi and Ughetto2020). It guides people in financial decision-making (Grohmann et al., Reference Grohmann, Klühs and Menkhoff2018), affects trust in the use of new technologies and increases tolerance for financial risks (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wu and Huang2023). The second mechanism is risk preference. Past research has found that individuals with higher risk tolerance demonstrate a greater propensity for entrepreneurial activities and financial investments (Dimmock et al., Reference Dimmock, Kouwenberg, Mitchell and Peijnenburg2016). As illustrated by prior studies (e.g., Huang, Kerstein, Wang, & Wu, Reference Huang, Kerstein, Wang and Wu2022), we conducted channel tests to establish the relationships between income stratification and two primary mechanisms and investigate how these relationships vary with regional DFI. For this purpose, we use a probit model to predict the household head’s financial literacyFootnote 3, and a pooled OLS regression to estimate their risk preferenceFootnote 4 (see Table 3).

Table 3. Channel tests

*,**,*** Notes: Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Two-tailed tests for control variables; one-tailed tests for hypothesized effects. P < 0.1, P < 0.05, P < 0.01.

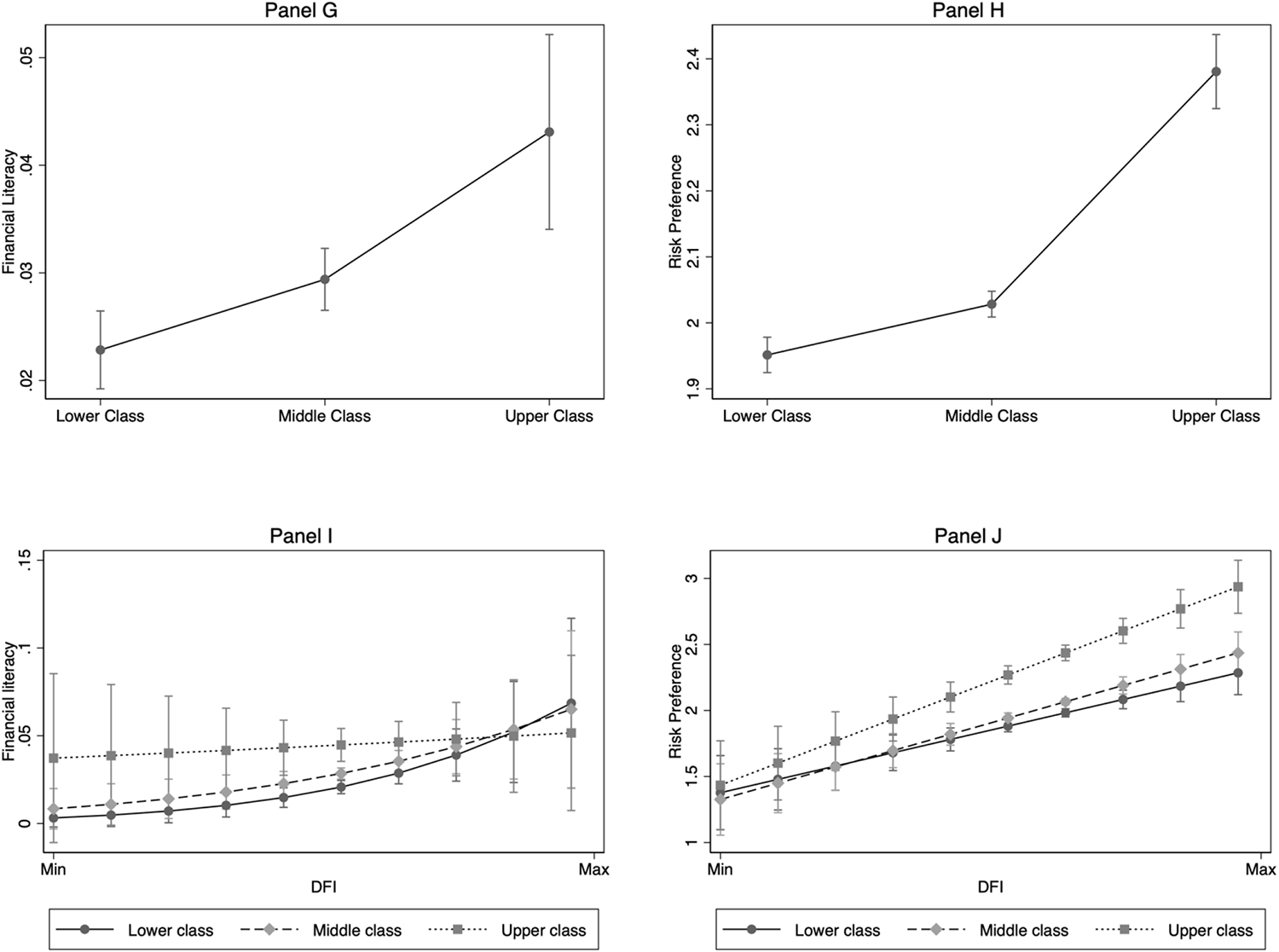

We find that, compared to those of affluent counterparts, low-income households are constrained by their lower levels of financial literacy and risk preference, as indicated by the consistent and significant negative coefficients of lower class for predicting financial literacy in Model 9 (β = −0.109, P < 0.01) and risk preference in Model 11 (β = −0.077, P < 0.01). As we plot the patterns in Panels G and H of Figure 2, upper-class households exhibit the highest levels of financial literacy and the greatest risk preference, followed by middle-class ones, while lower-class ones rank the lowest. Thus, we infer that the lack of financial literacy and risk tolerance among low-income households acts as a barrier to entrepreneurial activities. We also find the consistently significant and positive coefficients of DFI for both financial literacy in Model 9 (β = 0.195, P < 0.05) and risk preference in Model 11 (β = 0.240, P < 0.01), which verify a facilitating role of DFI to overcome limitations in cognition and risk attitudes in aggregate.

Figure 2. Channel tests

However, the inconsistent impacts of DFI across different income classes warrant further in-depth consideration. When examining the moderating effect of DFI for financial literacy in Model 10, we find that the coefficient of the interaction term, lower class X DFI, is significant and positive (β = 0.083, P < 0.1). Conversely, as for risk preference, we note in Model 12 that the coefficient of the interaction term, lower class X DFI, is significantly negative (β = −0.045, P < 0.05). Figure 2 provides some hints into how the inconsistent moderating effects of DFI affect lower-class household entrepreneurship. As shown in Panel I, DFI exhibits a marginally significant positive moderating effect on the financial literacy of lower-class households. However, across the majority of DFI’s value range, the financial literacy of lower-class households remains lower than that of middle- and upper-class households. This suggests that DFI alone is unlikely to bridge the gap in entrepreneurial activities and performance for low-income households by improving financial literacy. Moreover, as shown in Panel J, DFI exacerbates the gap in risk preference between low-income households and other income groups. Although DFI increases the risk acceptance of low-income households, the magnitude of this increase is significantly smaller compared to that of middle- and upper-income households. Thus, from an absolute standpoint, risk attitude serves as a mechanism through which DFI facilitates poverty alleviation via entrepreneurship. However, in relative terms, it acts as a channel through which DFI exacerbates the entrepreneurial gap across income classes.

Discussion

The United Nations emphasizes the role of DFI in accelerating sustainable development goals (SDGs), with ‘No poverty’ being identified as the first target (UNSGSA, 2018). While digital finance has been widely recognized as a catalyst for poverty alleviation through entrepreneurship (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Jiang and Karolyi2019; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016), most studies focus on its aggregate economic effects, often neglecting how it works for households from different income classes at various stages of entrepreneurship (e.g., Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Jiang and Karolyi2019; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016). Our study advances the ongoing discussion by examining how DFI differentially affects entrepreneurial outcomes across lower-, middle-, and upper-class households. Drawing upon 36,557 household-wave observations in the CHFS, the results show that lower-class households, despite exhibiting higher entrepreneurial propensity than middle-income groups, report lower levels of venture creation rates, entrepreneurial investment, and subsequent performance compared to upper-income households. Notably, although digital finance positively influences entrepreneurial activities across all income groups, its impacts are less pronounced for lower-income households.

Our study advances the literature in several ways. First, we enrich the income stratification theory and entrepreneurship literature by examining the heterogeneous entrepreneurial outcomes of each income class in a multi-stage entrepreneurial model (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Moergen, Tilton and Gray2023). This approach allows us to uncover nuanced patterns of entrepreneurial activities specific to different income groups. The findings show that upper-class households, endowed with abundant human, financial, and social capital, maintain significant advantages throughout all entrepreneurial stages. In contrast, lower-class households underperform in both entrepreneurial investment and performance, although they are more likely to pursue entrepreneurship than the middle class. This can be explained by the possibility that the entrepreneurial venture creation by lower-income households is mainly necessity-driven and takes the form of self-employment (Sutter et al., Reference Sutter, Bruton and Chen2019). In contrast, middle- and upper classes leverage their substantial resources to invest in industries with higher capital requirements and profit potential. This pattern aligns with Hurst and Lusardi’s (Reference Hurst and Lusardi2004) finding that a disproportionate number of wealthy households engage in entrepreneurship within professional sectors. Such differentiation in entrepreneurial behaviors further amplifies the disparities in resource acquisition and wealth accumulation across income classes. These results suggest that, when examining the impacts of income stratification on key entrepreneurial outcomes, it is crucial to distinguish and focus on the stage-specific decisions throughout the entrepreneurial process (Navis & Ozbek, Reference Navis and Ozbek2015).

Second, our study extends technology adoption literature by conceptualizing DFI at a regional digital financial technology adoption level that shapes entrepreneurial outcomes unevenly across income stratification (Huarng & Yu, Reference Huarng and Yu2022; Nguyen & Nguyen, Reference Nguyen and Nguyen2024; Rogers, Reference Rogers1965; Venkatesh & Davis, Reference Venkatesh and Davis2000). This addresses Lagna and Ravishankar’s (Reference Lagna and Ravishankar2022: 73) call to critically examine whether DFI ‘can really help the poor escape poverty’. Existing studies predominantly highlight the role of entrepreneurship in alleviating poverty through job creation and wealth generation (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Pamuk, Ramrattan and Uras2018; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Jiang and Karolyi2019; Suri & Jack, Reference Suri and Jack2016), and often assume that DFI inherently democratizes financial access and promotes inclusive growth. Our findings, however, challenge this assumption by showing that, even in regions with high DFI, lower-class households face a higher adoption barrier of digital financial technology and derive relatively limited benefits compared to their wealthier counterparts. Similarly, Park and Mercado (Reference Park, Mercado, Cavoli and Shrestha2021) observed that the poverty-reducing effects of DFI are significant only in higher-income economies but not in lower-income countries in their cross-country analysis. This asymmetry emerges from multidimensional factors. One reason is that the cognitive and psychological barriers rooted in social class dynamics, such as lower risk tolerance and constrained learning capacity, hinder lower-income households from fully leveraging digital financial tools. Another reason is the fact that profit-oriented service models by fintech firms often prioritize high-value clients, marginalizing less profitable groups. Finally, social factors including weak regulatory frameworks and geographically fragmented digital infrastructures, decrease the possibility for lower-class households to adopt digital financial technology. These findings highlight the paradox of technological advancement: while DFI can democratize financial access and foster entrepreneurship on a broader scale, it also risks amplifying preexisting socioeconomic inequalities if the technology adoption barriers faced by lower-income households are not adequately addressed.

Third, our study provides context-specific empirical evidence from China, thereby underscoring the critical role of national context in shaping the relationship between income stratification and DFI. Building on established research emphasizing contextual considerations (Pattnaik et al., Reference Pattnaik, Ang and Tang2025), we extend this perspective to the unique digital financial technology adoption process within China’s financial inclusion efforts. China’s experience with DFI exemplifies both the potential and limitations of digital financial innovations. Fintech platforms like Alipay and WeChat Pay have significantly expanded financial access, serving over 1 billion users by 2021 and lowering traditional financial barriers. These advances serve as evidence of the capacity of digital tools to improve transactional efficiency and financial reach. Yet this success also highlights challenges in achieving true inclusivity. Despite the Chinese central government’s active promotion of nationwide fintech infrastructure, it permits platforms like Ant Group to independently design profit-maximizing algorithms. This autonomy creates a paradox: while rapid technological adoption widens access, it also enables widespread regulatory arbitrage. For instance, an overreliance on digital footprints for credit assessments systematically excludes lower-income households with limited digital literacy or online activity (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Zhang and Li2023; World Bank Group & People’s Bank of China, 2018). Furthermore, the online P2P lending crisis of 2018 underscores the risks tied to unregulated financial innovation. Following the crisis, many vulnerable borrowers were excluded from formal financial systems due to damaged credit records, deepening their financial marginalization (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, McMullen, Artz and Simiyu2012; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Zhang and Li2023). This indicates that the benefits of DFI are neither automatic nor universally distributed. Instead, they heavily depend on government regulatory frameworks, including algorithmic accountability to prevent discriminatory lending practices, consumer protection mechanisms to guard against exploitative data use, and targeted educational programs to enhance digital and financial literacy among underprivileged populations (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine2007). These findings lead us to question the prevailing notion of DFI as a panacea for poverty alleviation and to call for more inclusive credit assessment models and targeted financial education programs.

Our findings also offer several practical contributions for entrepreneurial households and policymakers. For entrepreneurial households, particularly those from lower-class groups, our research highlights the double-edged effects of DFI. While these households should actively leverage digital financial services to support their entrepreneurial activities, they need to simultaneously improve their financial literacy to better manage associated risks. As demonstrated by the 2018 P2P lending crisis in China, inadequate financial literacy and risk awareness can lead to severe consequences, including debt traps and financial exclusion (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Korkmaz, Yin and Zhou2022). Therefore, lower-class households need to focus on developing digital competencies and financial management skills while carefully evaluating the terms and conditions of digital financial products before engagement.

For policymakers, our findings regarding the unequal moderating effects of DFI across income stratifications provide crucial insights. Our results indicate that DFI may unintentionally exacerbate wealth disparities because lower-class groups face significant barriers in leveraging digital financial services compared to middle- and upper-classes. These barriers include limited digital literacy, insufficient financial knowledge, and structural disadvantages in credit scoring systems. Despite these challenges, however, DFI remains a powerful tool for promoting inclusive entrepreneurship when properly designed and implemented. The way forward requires a multi-faceted approach. First, policymakers should strengthen regulatory oversight of digital financial service providers to prevent predatory practices and ensure fair access, while simultaneously developing differentiated DFI strategies that account for varying resource levels and capabilities across income groups. Second, digital microfinance represents a promising bridge between traditional financial inclusion strategies and modern digital platforms. Unlike conventional P2P lending which often prioritizes profit maximization, digital microfinance programs can maintain the community-based, education-integrated approach of traditional microfinance while leveraging digital technology to reduce costs and extend reach. Third, targeted interventions focusing on digital skills, financial management, and risk assessment for lower-income groups are essential. These initiatives could include community-based financial education programs, digital literacy workshops, and mentorship opportunities to help low-income entrepreneurs better utilize DFI for poverty reduction.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our study has some limitations that suggest several promising avenues for future research. For example, we chose China as our research context because of its rapid development in digital finance among developing countries. The comparability of DFI’s effectiveness in stimulating entrepreneurial activities between China and developed and developing countries should be examined. Future research could address this through cross-country comparative studies. Furthermore, beyond income-based stratification, social stratification can be analyzed through various dimensions such as gender and social status. Therefore, scholars could explore the heterogeneous barriers faced by disadvantaged groups across different stratification criteria when accessing and utilizing digital financial services for entrepreneurial activities in the future. Finally, our study identifies two primary mechanisms through which DFI affects individual characteristics across income classes: financial literacy and risk preference, both of which are cognitive and attitudinal variables at the individual level. Therefore, future research could explore additional mechanisms at the societal level, such as transaction costs, or examine the financial conditions of entrepreneurs to gain deeper insights into how DFI influences entrepreneurial behavior and outcomes.

Conclusion

In this study, we examine the relationship between DFI and entrepreneurship, focusing on its impacts across different income classes and entrepreneurial stages. If this article could provide a main message, it would be that DFI does encourage entrepreneurial activities and improve outcomes for lower-class households, but these positive effects remain notably smaller compared to those experienced by middle- and upper-class households. This means, in practical terms, that while DFI can be a valuable tool for reducing poverty and promoting entrepreneurship, policymakers and financial institutions must complement digital financial initiatives with targeted interventions – such as digital literacy education and tailored regulatory frameworks – to address pre-existing socioeconomic inequalities and ensure genuine inclusiveness.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are obtained from the China Household Finance Survey and Research Center of Southwest University of Finance and Economics. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from http://chfs.swufe.edu.cn/ with appropriate permission. The analysis code that supports the findings of this study is openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/tvhz6/

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant 72372119) and the Special Fund of Fundamental Scientific Research Business Expense for Higher School of Central Government (Grant 22120240563).

Yiyi Su (suyiyi@tongji.edu.cn) is a professor of management at the School of Economics and Management, Tongji University, China. Her research centers on innovation and entrepreneurship, internationalization, and Chinese management. Her recent studies are published in Management and Organization Review, Human Resource Management, Regional Studies, Public Administration Review, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Public Administration Review, Long Range Planning, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Management International Review, and Asia Pacific Journal of Management.

Shaker A. Zahra (zahra004@umn.edu) is the Department Chair, Robert E. Buuck Chair of Entrepreneurship and Professor of Strategy in the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota. He is also the Academic Director of the Gary S. Holmes Entrepreneurship Center. His publications appear in leading journals, such as Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Journal, Organization Science, Strategic Management Journal, Journal of International Business Studies, and Journal of Business Venturing, among other leading journals.

Ya’nan Zhang (yanan_zhang@tongji.edu.cn) is a PhD candidate in the School of Economics and Management of Tongji University (Shanghai). Her current research interests include Chinese outward investment, the Belt and Road Initiative, and entrepreneurship in China. Her recent studies have been published in International Business Review, European Journal of International Management, and Chinese Management Studies.

Mengdi Shang (2410137@tongji.edu.cn) is a PhD candidate in the School of Economics and Management of Tongji University (Shanghai). Her current research interests include digital transformation, text analysis, and entrepreneurship.