1. Introduction

The canonical problem of a starting object in a quiescent fluid has been investigated for more than a century, where the main focus has been on the force response and the starting vortices. An example is the early work of Prandtl (Reference Prandtl1936), who studied the starting vortex behind a wedge. The motion of an accelerating object in a fluid is relevant to various applications, such as the gust response of surging wings and wind turbine blades (Mancini et al. Reference Mancini, Manar, Granlund, Ol and Jones2015; Eldredge & Jones Reference Eldredge and Jones2019), flapping insect wings (Dickinson, Lehmann & Sane Reference Dickinson, Lehmann and Sane1999; Pullin & Wang Reference Pullin and Wang2004), ship manoeuvring and motion of offshore structures (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1986) and also certain sports, such as the propulsion force generated by a rowing blade (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019, Reference Grift, Tummers and Westerweel2021). When an object changes its velocity the kinetic energy of the surrounding fluid must also change. This change in kinetic energy requires work, which is interpreted as the work done by an ‘added mass force’ on the object (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967; Brennen Reference Brennen1982). In the case of an irrotational flow the added mass force can be computed through potential flow theory and scales linearly with acceleration. This is referred to as the inviscid added mass force. When the surrounding flow contains vorticity, it is often referred to as the circulatory force due to acceleration (e.g. Corkery, Stevens & Babinsky Reference Corkery, Stevens and Babinsky2017), of which the scaling with respect to the motion of the object is not fully known.

Perhaps the most widely used expression for the force on an object that experiences a variation in velocity is the Morison equation (Morison et al. Reference Morison, O’Brien, Johnson and Schaaf1950). This equation separates the time-dependent drag force

![]() $F_D(t)$

on an object into a quasisteady drag force

$F_D(t)$

on an object into a quasisteady drag force

![]() $F_{\textit{QS}}(t)$

and an acceleration drag force

$F_{\textit{QS}}(t)$

and an acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

,

$F_{{a}}(t)$

,

\begin{equation} F_D(t) = \underbrace {C_{\!D} \textstyle {\dfrac 12}\rho V^2(t) A}_{F_{\textit{QS}}(t)} +F_{{a}}(t), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} F_D(t) = \underbrace {C_{\!D} \textstyle {\dfrac 12}\rho V^2(t) A}_{F_{\textit{QS}}(t)} +F_{{a}}(t), \end{equation}

where

![]() $V(t)$

is the instantaneous velocity of the object,

$V(t)$

is the instantaneous velocity of the object,

![]() $C_{\!D}$

the steady-state drag coefficient,

$C_{\!D}$

the steady-state drag coefficient,

![]() $\rho$

the fluid density and

$\rho$

the fluid density and

![]() $A$

the frontal area of the object. The acceleration drag force

$A$

the frontal area of the object. The acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

in the original Morison equation is taken equal to the inviscid added mass force

$F_{{a}}(t)$

in the original Morison equation is taken equal to the inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}} = m_{{h}}a(t)$

, where the (time-dependent) acceleration

$F_{\textit{AM}} = m_{{h}}a(t)$

, where the (time-dependent) acceleration

![]() $a(t)$

is multiplied by a constant hydrodynamic mass

$a(t)$

is multiplied by a constant hydrodynamic mass

![]() $m_{{h}}$

, which is found from potential flow theory (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967; Brennen Reference Brennen1982) or determined empirically (Yu Reference Yu1945; Payne Reference Payne1981). When the flow is accelerating and the object is stationary,

$m_{{h}}$

, which is found from potential flow theory (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967; Brennen Reference Brennen1982) or determined empirically (Yu Reference Yu1945; Payne Reference Payne1981). When the flow is accelerating and the object is stationary,

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

includes the Froude–Krylov force (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1986). Morison et al. (Reference Morison, O’Brien, Johnson and Schaaf1950) originally considered a variation of fluid velocity due to small-amplitude linear wave motion, which is adequately described by potential flow. This justifies the use of the inviscid added mass force

$F_{{a}}(t)$

includes the Froude–Krylov force (Lighthill Reference Lighthill1986). Morison et al. (Reference Morison, O’Brien, Johnson and Schaaf1950) originally considered a variation of fluid velocity due to small-amplitude linear wave motion, which is adequately described by potential flow. This justifies the use of the inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

for

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

for

![]() $F_{{a}}$

in the original equation. The use of

$F_{{a}}$

in the original equation. The use of

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

is also justified for impulsive motions with a (nearly) instantaneous increase in velocity (e.g. von Kármán Reference von Kármán1929), where the flow and its change in kinetic energy are adequately described by potential flow. Using an inviscid added mass force for separated and viscous flows, where the flow pattern changes during the acceleration, is questionable, as noted by both Batchelor (Reference Batchelor1967) and Brennen (Reference Brennen1982).

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

is also justified for impulsive motions with a (nearly) instantaneous increase in velocity (e.g. von Kármán Reference von Kármán1929), where the flow and its change in kinetic energy are adequately described by potential flow. Using an inviscid added mass force for separated and viscous flows, where the flow pattern changes during the acceleration, is questionable, as noted by both Batchelor (Reference Batchelor1967) and Brennen (Reference Brennen1982).

Following Burgers (Reference Burgers1921), an object that is brought into motion in a fluid generates a vortex layer at its surface that diffuses into the fluid due to the viscosity of the fluid, and is subsequently ‘washed away’ by the flow. Then, another vortex layer is formed that also diffuses away, and so on, where the rate per unit of time of impulse to create the subsequent vortex layers forms the drag force experienced by the moving body. The model of Reijtenbagh, Tummers & Westerweel (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) is based on this concept, and is used later in this paper to describe the scaling of the force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

for accelerating plates. Burgers (Reference Burgers1921) subsequently derives an expression that relates the drag force on an object to the time derivative of the impulse of the fluid motion (see also Biesheuvel & Hagmeijer Reference Biesheuvel and Hagmeijer2006). Wu (Reference Wu1981) and Lighthill (Reference Lighthill1986) arrive independently at the same expression, which is the basis of methods to determine the force on a moving object from the surrounding velocity field (Noca, Shields & Jeon Reference Noca, Shields and Jeon1997; Limacher, Morton & Wood Reference Limacher, Morton and Wood2018; Corkery, Babinsky & Graham Reference Corkery, Babinsky and Graham2019). Several studies have elucidated the role of vortical fluid motion in the resulting forces acting on instationary moving objects; here we focus on recent ones. Pitt Ford & Babinsky (Reference Pitt Ford and Babinsky2013) study the flow around an accelerating plate in a towing tank to determine the inertial effect of the developing leading-edge vortex on the lift force. Fernando, Weymouth & Rival (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) demonstrate that inviscid added mass force does not properly explain the force that acts on a circular plate in a constant-acceleration motion. Later, Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) find that the peak value of the acceleration drag force

$F_{{a}}(t)$

for accelerating plates. Burgers (Reference Burgers1921) subsequently derives an expression that relates the drag force on an object to the time derivative of the impulse of the fluid motion (see also Biesheuvel & Hagmeijer Reference Biesheuvel and Hagmeijer2006). Wu (Reference Wu1981) and Lighthill (Reference Lighthill1986) arrive independently at the same expression, which is the basis of methods to determine the force on a moving object from the surrounding velocity field (Noca, Shields & Jeon Reference Noca, Shields and Jeon1997; Limacher, Morton & Wood Reference Limacher, Morton and Wood2018; Corkery, Babinsky & Graham Reference Corkery, Babinsky and Graham2019). Several studies have elucidated the role of vortical fluid motion in the resulting forces acting on instationary moving objects; here we focus on recent ones. Pitt Ford & Babinsky (Reference Pitt Ford and Babinsky2013) study the flow around an accelerating plate in a towing tank to determine the inertial effect of the developing leading-edge vortex on the lift force. Fernando, Weymouth & Rival (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) demonstrate that inviscid added mass force does not properly explain the force that acts on a circular plate in a constant-acceleration motion. Later, Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) find that the peak value of the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

=

$F_{{a}}(t)$

=

![]() $F_D(t)\!-\!F_{\textit{QS}}(t)$

does not scale linearly with acceleration, as would be expected for the inviscid added mass force

$F_D(t)\!-\!F_{\textit{QS}}(t)$

does not scale linearly with acceleration, as would be expected for the inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

, but rather scales with the square root of the acceleration.

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

, but rather scales with the square root of the acceleration.

Alternative approaches to describe the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

in (1.1) have been suggested, such as the vortex force decomposition (Gehlert, Andreu-Angelo & Babinsky Reference Gehlert, Andreu-Angelo and Babinsky2023) that divides the force into circulatory and non-circulatory components, the drift volume approach (McPhaden & Rival Reference McPhaden and Rival2018) and impulse-based methods (Wu Reference Wu1981; Lighthill Reference Lighthill1986; Limacher et al. Reference Limacher, Morton and Wood2018). These methods can be considered data-driven, since they require knowledge of the flow field and flow structures surrounding the object to provide the forces on the moving object. Hence, these methods are not suited to provide an a priori scaling of the drag force with respect to the acceleration of the object. Also, these methods take vorticity to be already present, usually in the form of starting vortices and shear layers, but do not describe explicitly how this vorticity is created. Morton (Reference Morton1984) provides a summary on the generation of vorticity at a wall.

$F_{{a}}(t)$

in (1.1) have been suggested, such as the vortex force decomposition (Gehlert, Andreu-Angelo & Babinsky Reference Gehlert, Andreu-Angelo and Babinsky2023) that divides the force into circulatory and non-circulatory components, the drift volume approach (McPhaden & Rival Reference McPhaden and Rival2018) and impulse-based methods (Wu Reference Wu1981; Lighthill Reference Lighthill1986; Limacher et al. Reference Limacher, Morton and Wood2018). These methods can be considered data-driven, since they require knowledge of the flow field and flow structures surrounding the object to provide the forces on the moving object. Hence, these methods are not suited to provide an a priori scaling of the drag force with respect to the acceleration of the object. Also, these methods take vorticity to be already present, usually in the form of starting vortices and shear layers, but do not describe explicitly how this vorticity is created. Morton (Reference Morton1984) provides a summary on the generation of vorticity at a wall.

Besides experimental studies, there have been numerous numerical studies that focus on the drag force on and the flow field around accelerating and impulsively started plates. Koumoutsakos & Shiels (Reference Koumoutsakos and Shiels1996) use numerical simulations to investigate the vorticity field around a two-dimensional plate in an accelerating flow over a wide range of accelerations with Reynolds numbers between 20 and 1000. They show that the drag coefficients for different accelerations collapse on a single curve, indicating the possible existence of a general scaling law. Pullin & Wang (Reference Pullin and Wang2004) use an inviscid model to describe the flow around an accelerating two-dimensional plate to obtain the unsteady forces that would mimic those of flapping insect wings. Later, Pullin & Sader (Reference Pullin and Sader2021) studied the trailing edge vortex in an inviscid fluid by the start-up motion of a two-dimensional plate, with power laws for both the translational and rotational velocities. Hinton et al. (Reference Hinton, Leonard, Pullin and Sader2024) extended their inviscid theory to an arbitrary two-dimensional body with sharp and straight edges, and formulated similarity solutions for the starting vortex at the trailing edges. Then, Sader et al. (Reference Sader, Hou, Hinton, Pullin and Colonius2024) assessed the inviscid predictions using results from direct numerical simulations. Although related to the present work, their studies mainly focused on the lift force on pitching plates that have an initial small angle of attack, whereas the present work is on the drag force on three-dimensional plates accelerating in a direction normal to the plate surface. Xu & Nitsche (Reference Xu and Nitsche2014) propose scaling laws for impulsively started two-dimensional plates for Reynolds numbers between 250 and 2000, and later determine similar scaling laws for constant and non-constant accelerations (Xu & Nitsche Reference Xu and Nitsche2015). Wang & Eldredge (Reference Wang and Eldredge2013) performed numerical simulations on impulsively started two-dimensional plates at various angles of attack using a viscous vortex particle method for a Reynolds number of 20 000. This low-order method closely resembles the creation and ‘washing away’ of vorticity described by Burgers (Reference Burgers1921).

In this paper we explore the scaling of the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

on plates that accelerate from rest in a stagnant fluid. We consider different types of motion, where a plate undergoes a finite-duration acceleration phase until a certain final velocity is reached, for both constant and non-constant accelerations. This work extends previously reported findings that the original Morison equation, that includes the inviscid added mass, underestimates the actual drag force both during and immediately after the acceleration phase (Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023). We measure the drag force on the plate during the entire motion, including a relaxation phase that follows the acceleration phase, where the drag force gradually attains the steady motion drag force, as illustrated in figure 1(a–d) for various examples taken from the full set of measurements over various accelerations

$F_{{a}}(t)$

on plates that accelerate from rest in a stagnant fluid. We consider different types of motion, where a plate undergoes a finite-duration acceleration phase until a certain final velocity is reached, for both constant and non-constant accelerations. This work extends previously reported findings that the original Morison equation, that includes the inviscid added mass, underestimates the actual drag force both during and immediately after the acceleration phase (Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023). We measure the drag force on the plate during the entire motion, including a relaxation phase that follows the acceleration phase, where the drag force gradually attains the steady motion drag force, as illustrated in figure 1(a–d) for various examples taken from the full set of measurements over various accelerations

![]() $a$

and final velocities

$a$

and final velocities

![]() $V_{{a}}$

. These examples illustrate the motivation behind this work. The same data is presented in figure 1(e–h), but now as a function of the dimensionless time

$V_{{a}}$

. These examples illustrate the motivation behind this work. The same data is presented in figure 1(e–h), but now as a function of the dimensionless time

![]() $t^*$

, defined as (Gharib, Rambod & Shariff Reference Gharib, Rambod and Shariff1998)

$t^*$

, defined as (Gharib, Rambod & Shariff Reference Gharib, Rambod and Shariff1998)

This is commonly referred to as the formation time, and it expresses the distance the plate has travelled since the start of the motion (

![]() $t=0$

) in terms of length

$t=0$

) in terms of length

![]() $\ell$

. We have chosen the length

$\ell$

. We have chosen the length

![]() $\ell$

to be equal to the plate height

$\ell$

to be equal to the plate height

![]() $\ell _b$

. The measurements presented in figure 1 are similar to those reported by Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019) and Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023); experimental details are given in § 2.

$\ell _b$

. The measurements presented in figure 1 are similar to those reported by Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019) and Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023); experimental details are given in § 2.

Figure 1. The measured drag force

![]() $F_D(t)$

on a rectangular plate with frontal area

$F_D(t)$

on a rectangular plate with frontal area

![]() $A$

=

$A$

=

![]() $\ell _a\times \ell _b$

= 0.2

$\ell _a\times \ell _b$

= 0.2

![]() $\times$

0.1 m

$\times$

0.1 m

![]() $^2$

for a motion with constant acceleration

$^2$

for a motion with constant acceleration

![]() $a$

until it reaches a final velocity

$a$

until it reaches a final velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

. Different colours represent the results for five repetitions of the same experiment. Data for four different combinations of the acceleration

$V_{{a}}$

. Different colours represent the results for five repetitions of the same experiment. Data for four different combinations of the acceleration

![]() $a$

and velocity

$a$

and velocity

![]() $V_a$

are plotted as a function of (a–d) time

$V_a$

are plotted as a function of (a–d) time

![]() $t$

in seconds, and (e–h) dimensionless time

$t$

in seconds, and (e–h) dimensionless time

![]() $t^*$

, defined in (1.2). The black lines indicate the quasisteady drag force,

$t^*$

, defined in (1.2). The black lines indicate the quasisteady drag force,

![]() $F_{ {QS}} = C_{\!D}( {1}/{2})\rho V^2(t) A$

(

$F_{ {QS}} = C_{\!D}( {1}/{2})\rho V^2(t) A$

(![]() ); the inviscid added mass force,

); the inviscid added mass force,

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}} = m_{{h}}a(t)$

(

$F_{\textit{AM}} = m_{{h}}a(t)$

(![]() ), with

), with

![]() $m_{{h}}$

given by Payne (Reference Payne1981); the combined force,

$m_{{h}}$

given by Payne (Reference Payne1981); the combined force,

![]() $F_{\textit{QS}}+F_{\textit{AM}}$

(

$F_{\textit{QS}}+F_{\textit{AM}}$

(![]() ). The acceleration phase of the motion is indicated by ‘A’, and the relaxation phase by ‘R’. The shaded area labelled ‘E’ on the left-hand side in each graph indicates the robot engagement at the start of the plate motion, see Appendix A. The roman numerals refer to the flow fields shown in figures 4 and 5.

). The acceleration phase of the motion is indicated by ‘A’, and the relaxation phase by ‘R’. The shaded area labelled ‘E’ on the left-hand side in each graph indicates the robot engagement at the start of the plate motion, see Appendix A. The roman numerals refer to the flow fields shown in figures 4 and 5.

During the acceleration phase of the motion, the drag force

![]() $F_D$

increases steadily, until it reaches a peak value at the end of the acceleration phase. When the acceleration ceases, and the plate assumes a constant velocity

$F_D$

increases steadily, until it reaches a peak value at the end of the acceleration phase. When the acceleration ceases, and the plate assumes a constant velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

, the drag force gradually relaxes to its steady-state value. Five repetitions of the measured drag force are superimposed to illustrate the experimental variation. The black solid lines in figure 1 indicate

$V_{{a}}$

, the drag force gradually relaxes to its steady-state value. Five repetitions of the measured drag force are superimposed to illustrate the experimental variation. The black solid lines in figure 1 indicate

![]() $F_{\textit{QS}}+F_{\textit{AM}}$

. The drag force during the acceleration phase of the plate is underestimated, and also, after the acceleration ceases and the plate assumes a constant velocity, the drag force does not suddenly drop to

$F_{\textit{QS}}+F_{\textit{AM}}$

. The drag force during the acceleration phase of the plate is underestimated, and also, after the acceleration ceases and the plate assumes a constant velocity, the drag force does not suddenly drop to

![]() $F_{\textit{QS}}$

, as would be predicted by

$F_{\textit{QS}}$

, as would be predicted by

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

, but instead gradually relaxes to the steady state value. Evidently, the experimental results in figure 1 for different combinations of acceleration

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

, but instead gradually relaxes to the steady state value. Evidently, the experimental results in figure 1 for different combinations of acceleration

![]() $a$

and final velocity

$a$

and final velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

show that the inviscid added mass force

$V_{{a}}$

show that the inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

does not properly describe the force during the acceleration and relaxation phases of the motion. The peak in

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

does not properly describe the force during the acceleration and relaxation phases of the motion. The peak in

![]() $F_D(t)$

at the initiation of the motion is the result of the engagement of the robot that drives the plate motion, as is explained in Appendix A. Note that when we use

$F_D(t)$

at the initiation of the motion is the result of the engagement of the robot that drives the plate motion, as is explained in Appendix A. Note that when we use

![]() $t^*$

for the horizontal axis in figure 1(e–h) the measured drag force

$t^*$

for the horizontal axis in figure 1(e–h) the measured drag force

![]() $F_D$

at the start of the motion is compressed towards

$F_D$

at the start of the motion is compressed towards

![]() $t^* = 0$

, as the plate barely moves at the start of the motion.

$t^* = 0$

, as the plate barely moves at the start of the motion.

The objective of this experimental study is to expand the approach of Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) to find a scaling law for the drag force on starting plates. We first consider motions where the acceleration is constant as in the study of Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023). However, in the present work the drag force is considered during the entire motion, rather than only the peak force at the end of the acceleration phase. Also, to test the validity of the model proposed by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) motions are repeated in fluids with different viscosities, and we perform measurements for motions with non-constant acceleration. We first consider a motion where the plate is initially at rest and is subsequently accelerated with a constant jerk

![]() $J = \dot {a} =$

constant. This motion avoids a discontinuous change in the acceleration at the start of the motion. Finally, we consider a motion where the plate is accelerated such that the velocity increases with the square root of time, i.e.

$J = \dot {a} =$

constant. This motion avoids a discontinuous change in the acceleration at the start of the motion. Finally, we consider a motion where the plate is accelerated such that the velocity increases with the square root of time, i.e.

![]() $V(t)\propto \sqrt {t}$

. This motion would predict a constant acceleration drag force

$V(t)\propto \sqrt {t}$

. This motion would predict a constant acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

according to the model proposed by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023).

$F_{{a}}(t)$

according to the model proposed by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023).

One of the complications of finding proper scaling laws for the drag force during an accelerating motion is that the velocity of the object changes constantly, while the final velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

at the end of the acceleration phase is yet ‘unknown’ during the acceleration phase. This implies that we cannot identify a proper characteristic velocity of the motion, and thus also cannot identify a proper velocity-based Reynolds number to characterize the fluid motion. Hence, we look for alternative dimensionless numbers that are invariant to the motion. This is further discussed in § 3.

$V_{{a}}$

at the end of the acceleration phase is yet ‘unknown’ during the acceleration phase. This implies that we cannot identify a proper characteristic velocity of the motion, and thus also cannot identify a proper velocity-based Reynolds number to characterize the fluid motion. Hence, we look for alternative dimensionless numbers that are invariant to the motion. This is further discussed in § 3.

An outline of this paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the experimental methods that are used to determine the forces on the accelerating plates, including the experimental facility, the different motions, the geometries of the plates and the different working fluids, in addition to the methods used to measure the forces and flow field. Section 3 explains the model that describes the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

during the acceleration phase and subsequent relaxation phase. Also a modified Reynolds number is identified that does not explicitly depend on the velocity. This acceleration Reynolds number is used to scale the acceleration drag force. Sections 4 and 5 present the results of the experiments for both the constant acceleration and non-constant acceleration motions. The main conclusions of this study are summarized in § 6.

$F_{{a}}(t)$

during the acceleration phase and subsequent relaxation phase. Also a modified Reynolds number is identified that does not explicitly depend on the velocity. This acceleration Reynolds number is used to scale the acceleration drag force. Sections 4 and 5 present the results of the experiments for both the constant acceleration and non-constant acceleration motions. The main conclusions of this study are summarized in § 6.

2. Experiments

2.1. Experimental set-up

Figure 2 shows the experimental set-up, which is identical to that of Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). It consists of a rectangular plate with an aspect ratio of 1 : 2 (AR = 2) with a width

![]() $\ell _a$

of 0.200 m, a height

$\ell _a$

of 0.200 m, a height

![]() $\ell _b$

of 0.100 m and thickness

$\ell _b$

of 0.100 m and thickness

![]() $\ell _c$

of 4 mm, connected to an industrial gantry robot (Reis Robotics RL50). The plate is translated through a 2.00

$\ell _c$

of 4 mm, connected to an industrial gantry robot (Reis Robotics RL50). The plate is translated through a 2.00

![]() $\times$

2.00

$\times$

2.00

![]() $\times$

0.60 m

$\times$

0.60 m

![]() $^3$

water-filled tank, with a water height of 0.50 m. The top of this plate is 1.5

$^3$

water-filled tank, with a water height of 0.50 m. The top of this plate is 1.5

![]() $\ell _b$

below the water surface, so that it can be considered fully submerged (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). With a frontal area of

$\ell _b$

below the water surface, so that it can be considered fully submerged (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). With a frontal area of

![]() $A$

=

$A$

=

![]() $\ell _a\times \ell _b$

= 0.020 m

$\ell _a\times \ell _b$

= 0.020 m

![]() $^2$

, the blockage ratio is 0.02, which is well below the value of 0.06 for which walls may begin to influence the drag force (West & Apelt Reference West and Apelt1982). In addition to this rectangular plate, a square plate and a circular plate, both with

$^2$

, the blockage ratio is 0.02, which is well below the value of 0.06 for which walls may begin to influence the drag force (West & Apelt Reference West and Apelt1982). In addition to this rectangular plate, a square plate and a circular plate, both with

![]() $A$

= 200.0 cm

$A$

= 200.0 cm

![]() $^2$

, are also tested, in addition to AR = 2 rectangular plates with frontal areas of 312.5 and 112.5 cm

$^2$

, are also tested, in addition to AR = 2 rectangular plates with frontal areas of 312.5 and 112.5 cm

![]() $^2$

, respectively, see § 4.2. All plates are made of acrylic and have the same thickness, i.e. 4 mm.

$^2$

, respectively, see § 4.2. All plates are made of acrylic and have the same thickness, i.e. 4 mm.

Figure 2. Schematic of the experimental set-up, viewed from the side (a) and from above (b), consisting of a large water-filled tank, with a gantry robot moving a plate with a prescribed motion. A light sheet illuminates a planar cross-section of the flow through the middle of the plate. A digital high-speed camera is positioned below the water-filled tank and observes the flow through a

![]() $45^\circ$

mirror. The shaded area represents the field-of-view of the camera. For the measurements in the water–glycerol mixtures at elevated viscosities a smaller tank, outlined by the dotted line, is placed inside the larger tank, see text for further details. Photographs of the experimental set-up are available as Supplementary material at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.11107.

$45^\circ$

mirror. The shaded area represents the field-of-view of the camera. For the measurements in the water–glycerol mixtures at elevated viscosities a smaller tank, outlined by the dotted line, is placed inside the larger tank, see text for further details. Photographs of the experimental set-up are available as Supplementary material at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.11107.

The use of thin plates, instead of streamlined bodies, has the advantage that the quasisteady drag coefficient

![]() $C_{\!D}$

in (1.1) hardly varies with the Reynolds number

$C_{\!D}$

in (1.1) hardly varies with the Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

when

${\textit{Re}}$

when

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

${\textit{Re}}$

![]() $\gt 10^3$

(Blevins Reference Blevins2003), see also § 3.1.

$\gt 10^3$

(Blevins Reference Blevins2003), see also § 3.1.

In this paper we focus on measurements of the drag force on AR = 2 rectangular plates, following Ringuette, Milano & Gharib (Reference Ringuette, Milano and Gharib2007), Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019) and Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023). One can argue that it makes more sense to primarily consider a circular plate, and later test for other geometries. There are two main reasons for using the rectangular AR = 2 plate. As shown by Fernando & Rival (Reference Fernando and Rival2016) and Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019), there are clear peaks in the drag force at certain values of

![]() $t^*$

that occur due to significant changes in the originally formed vortex ring behind a circular plate. Also, Fernando & Rival (Reference Fernando and Rival2016) and Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) show that circular plates show a large decrease of

$t^*$

that occur due to significant changes in the originally formed vortex ring behind a circular plate. Also, Fernando & Rival (Reference Fernando and Rival2016) and Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) show that circular plates show a large decrease of

![]() $F_D$

after the acceleration phase until

$F_D$

after the acceleration phase until

![]() $t^* \approx 20$

, even below what is expected from a steady-state drag force. With this in mind, one could question the validity of (1.1) during the relaxation phase of the motion, and even during the acceleration phase. These complications do not appear to occur for rectangular plates, where the drag force

$t^* \approx 20$

, even below what is expected from a steady-state drag force. With this in mind, one could question the validity of (1.1) during the relaxation phase of the motion, and even during the acceleration phase. These complications do not appear to occur for rectangular plates, where the drag force

![]() $F_D$

during the relaxation phase decays more or less gradually to the expected steady-state value, see figure 1.

$F_D$

during the relaxation phase decays more or less gradually to the expected steady-state value, see figure 1.

The robot is programmed to move the plates through the fluid along a straight path in the middle of the tank. The start and end positions of the plate are at least three times the plate height from the front and rear facing tank walls. Previously Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019) showed that the flow remains unperturbed over a distance 2.4 times the plate height in front of the plate.

Additional measurements are performed in a smaller tank (with dimensions of 1.50

![]() $\times$

0.75

$\times$

0.75

![]() $\times$

0.60 m

$\times$

0.60 m

![]() $^3$

) for three different water–glycerol mixtures to investigate the effect of the fluid viscosity

$^3$

) for three different water–glycerol mixtures to investigate the effect of the fluid viscosity

![]() $\nu$

, see table 1. The smaller tank is designed such that the plates can reach a final velocity

$\nu$

, see table 1. The smaller tank is designed such that the plates can reach a final velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

of 0.90 m s−1 for a large range of accelerations without any wall effects by keeping the blockage ratio of the rectangular plate below 0.06. The finite length of the smaller tank limits the final plate velocity

$V_{{a}}$

of 0.90 m s−1 for a large range of accelerations without any wall effects by keeping the blockage ratio of the rectangular plate below 0.06. The finite length of the smaller tank limits the final plate velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

to 0.90 m s−1. The full range of experiments with constant accelerations is given by table 2. The motions in experiments with non-constant accelerations are shown in figure 3 and details of these experiments are given in table 3.

$V_{{a}}$

to 0.90 m s−1. The full range of experiments with constant accelerations is given by table 2. The motions in experiments with non-constant accelerations are shown in figure 3 and details of these experiments are given in table 3.

Table 1. The dynamic viscosity

![]() $\mu$

, density

$\mu$

, density

![]() $\rho$

and kinematic viscosity

$\rho$

and kinematic viscosity

![]() $\nu$

of water (V1) and water–glycerol mixtures (V2–4).

$\nu$

of water (V1) and water–glycerol mixtures (V2–4).

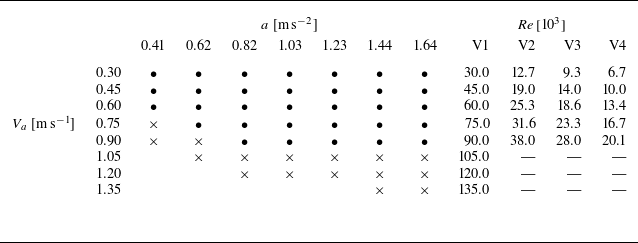

Table 2. Overview of the accelerations

![]() $a$

and final velocities

$a$

and final velocities

![]() $V_{{a}}$

in the constant-acceleration experiments with the AR = 2 rectangular plate. Crosses indicate the combinations of acceleration and velocity that are done with water only; dots indicate the combinations of acceleration and velocity with water and water–glycerol mixtures at higher viscosities. The Reynolds number

$V_{{a}}$

in the constant-acceleration experiments with the AR = 2 rectangular plate. Crosses indicate the combinations of acceleration and velocity that are done with water only; dots indicate the combinations of acceleration and velocity with water and water–glycerol mixtures at higher viscosities. The Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

is given by the velocity

${\textit{Re}}$

is given by the velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

, the plate height

$V_{{a}}$

, the plate height

![]() $\ell _b$

and the kinematic viscosity

$\ell _b$

and the kinematic viscosity

![]() $\nu$

of the fluid, i.e. either water (V1) or the water–glycerol mixtures (V2–V4), see table 1.

$\nu$

of the fluid, i.e. either water (V1) or the water–glycerol mixtures (V2–V4), see table 1.

The plate is connected to the gantry robot with a streamlined strut. We use either of two force sensors between the robot and the plate, where one sensor (ATI Gamma 32-2.5) is used for measurements with lower final velocities (

![]() $V_{{a}}\lt$

0.6 m s−1), while the other sensor (ATI Delta 660-60) is used for those with higher velocities (

$V_{{a}}\lt$

0.6 m s−1), while the other sensor (ATI Delta 660-60) is used for those with higher velocities (

![]() $V_{{a}}\geqslant$

0.6 m s−1). The force signals are filtered using a low-pass filter with a 15 Hz cutoff frequency to reduce noise in the measured signal that originates from the robot (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). The drag force

$V_{{a}}\geqslant$

0.6 m s−1). The force signals are filtered using a low-pass filter with a 15 Hz cutoff frequency to reduce noise in the measured signal that originates from the robot (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). The drag force

![]() $F_D(t)$

is found from the measured force

$F_D(t)$

is found from the measured force

![]() $F(t)$

by subtracting the inertia

$F(t)$

by subtracting the inertia

![]() $m_pa(t)$

of the plate and the strut, where

$m_pa(t)$

of the plate and the strut, where

![]() $m_p$

is their combined mass, and the (very small) measured drag imposed by the strut.

$m_p$

is their combined mass, and the (very small) measured drag imposed by the strut.

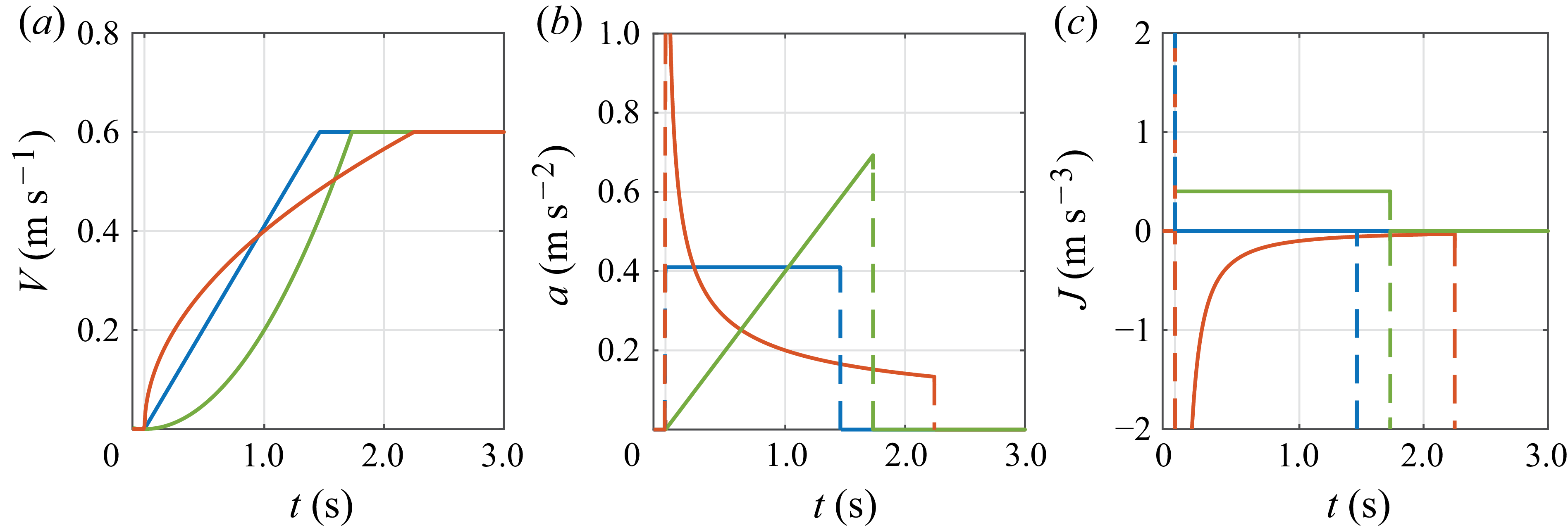

Figure 3. Examples of the programmed plate motions with prescribed (a) velocity

![]() $V(t)$

, (b) acceleration

$V(t)$

, (b) acceleration

![]() $a(t)$

and (c) jerk

$a(t)$

and (c) jerk

![]() $J(t)$

: constant acceleration (blue); quadratic velocity motion (green); square-root velocity motion (red). Dashed lines indicate discontinuities in acceleration or jerk. In this example, the final velocity is

$J(t)$

: constant acceleration (blue); quadratic velocity motion (green); square-root velocity motion (red). Dashed lines indicate discontinuities in acceleration or jerk. In this example, the final velocity is

![]() $V_{{a}}$

= 0.6 m s−1, see tables 2 and 3 for an overview of all motions.

$V_{{a}}$

= 0.6 m s−1, see tables 2 and 3 for an overview of all motions.

2.2. Particle image velocimetry

Planar particle image velocimetry (PIV) is used to characterize the flow around the plates. A high-speed camera (Phantom VEO 640 L) is used to record 2560

![]() $\times$

1600 pixel images at a rate of 1000 frames per second of small neutrally buoyant fluorescent tracer particles (Cospheric UVPMS-BR-0.995, with 53–63

$\times$

1600 pixel images at a rate of 1000 frames per second of small neutrally buoyant fluorescent tracer particles (Cospheric UVPMS-BR-0.995, with 53–63

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m diameter) suspended in the water-filled tank. A 4 mm-thick light sheet from a frequency-doubled Nd:YLF pulsed laser (Litron LDY304-PIV, 527 nm light wavelength) illuminates the tracer particles in a planar cross-section of the tank. The camera and laser sheet are set up to ensure that the field of view is through the centre of the plate in a horizontal plane. This two-dimensional field is representative of the three-dimensional flow around the plate. The field of view has dimensions of 913

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m diameter) suspended in the water-filled tank. A 4 mm-thick light sheet from a frequency-doubled Nd:YLF pulsed laser (Litron LDY304-PIV, 527 nm light wavelength) illuminates the tracer particles in a planar cross-section of the tank. The camera and laser sheet are set up to ensure that the field of view is through the centre of the plate in a horizontal plane. This two-dimensional field is representative of the three-dimensional flow around the plate. The field of view has dimensions of 913

![]() $\times$

477 mm

$\times$

477 mm

![]() $^2$

, which is sufficient to capture the full width of the wake and to follow the plate over a distance of more than six times the plate height (i.e.

$^2$

, which is sufficient to capture the full width of the wake and to follow the plate over a distance of more than six times the plate height (i.e.

![]() $t^* \gt 6)$

.

$t^* \gt 6)$

.

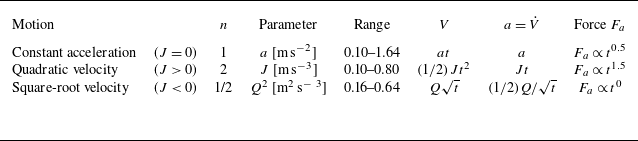

Table 3. Overview of three accelerating motions with velocity

![]() $V \propto t^n$

and acceleration

$V \propto t^n$

and acceleration

![]() $a \propto t^{n-1}$

, with

$a \propto t^{n-1}$

, with

![]() $n$

= 1, 2 and

$n$

= 1, 2 and

![]() $\textstyle 1/2$

; these correspond to ‘zero jerk’ (

$\textstyle 1/2$

; these correspond to ‘zero jerk’ (

![]() $J=0$

), ‘positive jerk’ (

$J=0$

), ‘positive jerk’ (

![]() $J\gt 0$

) and ‘negative jerk’ (

$J\gt 0$

) and ‘negative jerk’ (

![]() $J\lt 0$

) motions, respectively. The scaling for the force

$J\lt 0$

) motions, respectively. The scaling for the force

![]() $F_{{a}}$

is according to the model in (3.1) proposed by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023).

$F_{{a}}$

is according to the model in (3.1) proposed by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023).

The PIV images are analysed using commercial software (Davis 10.2, LaVision GmbH), using a multipass sliding sum-of-correlation method between the

![]() $n$

th frame and (

$n$

th frame and (

![]() $n$

+ 2)th frame, with 48

$n$

+ 2)th frame, with 48

![]() $\times$

48-pixel interrogation regions at the initial pass to 24

$\times$

48-pixel interrogation regions at the initial pass to 24

![]() $\times$

24-pixel windows at the final pass, and with 50 % overlap between adjacent interrogations windows. The final result for the velocity fields has a data spacing of 4.19 mm (i.e. 8.37 mm spatial resolution). The velocities in the final results pass a universal outlier detection test (Westerweel & Scarano Reference Westerweel and Scarano2005), indicating that the results contain at least 99.8 % valid data; rejected interrogation results are replaced by linear interpolation.

$\times$

24-pixel windows at the final pass, and with 50 % overlap between adjacent interrogations windows. The final result for the velocity fields has a data spacing of 4.19 mm (i.e. 8.37 mm spatial resolution). The velocities in the final results pass a universal outlier detection test (Westerweel & Scarano Reference Westerweel and Scarano2005), indicating that the results contain at least 99.8 % valid data; rejected interrogation results are replaced by linear interpolation.

3. Model

3.1. Background

Our point of departure is Morison’s equation (1.1) as modified by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) to describe the drag force on an accelerating plate. The quasisteady force remains unchanged, and instead of the conventional inviscid added mass for the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

we use a history-based acceleration drag force. Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) showed that this gives a better representation of the total drag force. Figure 4 shows the flow field around the plate at different dimensionless times. Figure 4(a) shows the potential flow solution for a moving plate, which resembles the measured flow field at

$F_{{a}}(t)$

we use a history-based acceleration drag force. Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) showed that this gives a better representation of the total drag force. Figure 4 shows the flow field around the plate at different dimensionless times. Figure 4(a) shows the potential flow solution for a moving plate, which resembles the measured flow field at

![]() $t^*=0.05$

in figure 4(b). This indicates that at these short times potential flow, and therefore inviscid added mass, remains a good approximation of the flow and drag force on the plate, although evidence of vorticity at the plate edges is visible. However, note that here

$t^*=0.05$

in figure 4(b). This indicates that at these short times potential flow, and therefore inviscid added mass, remains a good approximation of the flow and drag force on the plate, although evidence of vorticity at the plate edges is visible. However, note that here

![]() $t^*$

= 0.05 corresponds to a plate displacement of 5 mm that is just slightly larger than the plate thickness (4 mm).

$t^*$

= 0.05 corresponds to a plate displacement of 5 mm that is just slightly larger than the plate thickness (4 mm).

Figure 4. The flow around an accelerating AR = 2 rectangular plate. (a) Potential flow around a flat plate, with streamlines in blue. The measured flow around the plate for

![]() $a$

= 0.82 m s−2 and

$a$

= 0.82 m s−2 and

![]() $V_{{a}}$

= 0.40 m s−1 (corresponding to

$V_{{a}}$

= 0.40 m s−1 (corresponding to

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

= 40

${\textit{Re}}$

= 40

![]() $\times$

10

$\times$

10

![]() $^3$

) at dimensionless times:

$^3$

) at dimensionless times:

![]() $t^*$

= 0.05 (b), 0.10 (c), 0.20 (d) and 0.75 (e), respectively, in a fixed frame of reference. The panels (b–e) correspond to the roman numerals I–IV in figure 1. Panels (f–i) represent the same data as (b–e), but now represented in a frame of reference moving with the plate. The colour scale indicates dimensionless out-of-plane component of the vorticity

$t^*$

= 0.05 (b), 0.10 (c), 0.20 (d) and 0.75 (e), respectively, in a fixed frame of reference. The panels (b–e) correspond to the roman numerals I–IV in figure 1. Panels (f–i) represent the same data as (b–e), but now represented in a frame of reference moving with the plate. The colour scale indicates dimensionless out-of-plane component of the vorticity

![]() $\omega ^* = \omega _z \ell _b / V_{{a}}$

. Dimensions (

$\omega ^* = \omega _z \ell _b / V_{{a}}$

. Dimensions (

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

) are made dimensionless with the plate height

$y$

) are made dimensionless with the plate height

![]() $\ell _b$

. For clarity only one out of four velocity vectors is shown.

$\ell _b$

. For clarity only one out of four velocity vectors is shown.

When the plate further progresses during the acceleration the flow starts to separate and a starting vortex loop is created (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019), visible as the vortex pair in figure 4(c). Here, potential flow is no longer appropriate to describe the flow, and therefore is not a proper basis for estimating the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

. This is in line with earlier derivations (Burgers Reference Burgers1921; Biesheuvel & Hagmeijer Reference Biesheuvel and Hagmeijer2006; Limacher et al. Reference Limacher, Morton and Wood2018) where the acceleration drag force is equal to inviscid added mass at early stages only, without flow separation, and where the vorticity is only present in a thin boundary layer close to the plate. This boundary layer is readily visible in figure 4(d–e) (see also figure 18 in Appendix B) and figure 4(h–i), where the flow field is represented in a frame of reference that moves with the plate. The incoming flow impinging on the plate resembles a Hiemenz flow (Emanuel Reference Emanuel2000), which is that of a stationary irrotational outer flow that resembles a stagnation point flow with a viscous boundary layer with a thickness that is inversely proportional to the square root of the flow Reynolds number. The moving plate in the fluid generates vorticity at the surface that diffuses into the fluid and then advects to the edges of the plate where it accumulates in the vortex (Burgers Reference Burgers1921; Biesheuvel & Hagmeijer Reference Biesheuvel and Hagmeijer2006). Figure 5 shows the further development of the instantaneous flow to illustrate the transition of the flow into that of a turbulent wake.

$F_{{a}}(t)$

. This is in line with earlier derivations (Burgers Reference Burgers1921; Biesheuvel & Hagmeijer Reference Biesheuvel and Hagmeijer2006; Limacher et al. Reference Limacher, Morton and Wood2018) where the acceleration drag force is equal to inviscid added mass at early stages only, without flow separation, and where the vorticity is only present in a thin boundary layer close to the plate. This boundary layer is readily visible in figure 4(d–e) (see also figure 18 in Appendix B) and figure 4(h–i), where the flow field is represented in a frame of reference that moves with the plate. The incoming flow impinging on the plate resembles a Hiemenz flow (Emanuel Reference Emanuel2000), which is that of a stationary irrotational outer flow that resembles a stagnation point flow with a viscous boundary layer with a thickness that is inversely proportional to the square root of the flow Reynolds number. The moving plate in the fluid generates vorticity at the surface that diffuses into the fluid and then advects to the edges of the plate where it accumulates in the vortex (Burgers Reference Burgers1921; Biesheuvel & Hagmeijer Reference Biesheuvel and Hagmeijer2006). Figure 5 shows the further development of the instantaneous flow to illustrate the transition of the flow into that of a turbulent wake.

Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) use Stokes’ first problem as an ansatz for a model that incorporates the generation and diffusion of vorticity for an accelerating plate. This is then generalized to account for the advection of vorticity along the plate surface, which leads to a model where the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

is proportional to

$F_{{a}}(t)$

is proportional to

![]() $\sqrt {aV}$

. The derivation of this model is summarized in Appendix B.

$\sqrt {aV}$

. The derivation of this model is summarized in Appendix B.

Figure 5. The instantaneous flow field around an accelerating AR = 2 rectangular plate in the same experiment as in figure 4, at dimensionless times

![]() $t^*$

= 2.0 (a), 3.0 (b), 4.0 (c), 5.0 (d) and 7.0 (e), respectively. Dimensions (

$t^*$

= 2.0 (a), 3.0 (b), 4.0 (c), 5.0 (d) and 7.0 (e), respectively. Dimensions (

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

) are made dimensionless with the plate height

$y$

) are made dimensionless with the plate height

![]() $\ell _b$

. For clarity only one out of four velocity vectors is shown. The colours represent the dimensionless out-of-plane component of the vorticity

$\ell _b$

. For clarity only one out of four velocity vectors is shown. The colours represent the dimensionless out-of-plane component of the vorticity

![]() $\omega ^* = \omega _z\ell _b/V_{{a}}$

. The roman numerals correspond to those in figure 1.

$\omega ^* = \omega _z\ell _b/V_{{a}}$

. The roman numerals correspond to those in figure 1.

3.2. Acceleration drag force

Combining the results of Xu & Nitsche (Reference Xu and Nitsche2015) and Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023) we find for the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

,

$F_{{a}}(t)$

,

\begin{equation} F_{{a}}(t) = \underbrace {C\frac {a^{1/4}\ell ^{3/4}}{\nu ^{1/2}}}_{C_{{a}}}\rho A \sqrt {\nu a V}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} F_{{a}}(t) = \underbrace {C\frac {a^{1/4}\ell ^{3/4}}{\nu ^{1/2}}}_{C_{{a}}}\rho A \sqrt {\nu a V}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $C$

is an empirical constant and

$C$

is an empirical constant and

![]() $\ell$

an appropriate length scale. Note that

$\ell$

an appropriate length scale. Note that

![]() $\sqrt {aV} = at^{1/2}$

for a constant acceleration

$\sqrt {aV} = at^{1/2}$

for a constant acceleration

![]() $a$

. Rewriting (3.1) by eliminating

$a$

. Rewriting (3.1) by eliminating

![]() $\sqrt \nu$

gives

$\sqrt \nu$

gives

where

![]() $\ell _{{h}}(t)$

(

$\ell _{{h}}(t)$

(

![]() $=Ca^{1/4}\ell ^{3/4}t^{1/2}$

) absorbs the time dependency of (3.1) and other remaining constants, and

$=Ca^{1/4}\ell ^{3/4}t^{1/2}$

) absorbs the time dependency of (3.1) and other remaining constants, and

![]() $m_{{h}}(t)$

represents a time-dependent ‘hydrodynamic mass’ of the accelerating plate (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). The length scale

$m_{{h}}(t)$

represents a time-dependent ‘hydrodynamic mass’ of the accelerating plate (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). The length scale

![]() $\ell _{{h}}(t)$

would represent the dimension of the ‘volume of fluid’

$\ell _{{h}}(t)$

would represent the dimension of the ‘volume of fluid’

![]() $A\ell _{{h}}(t)$

that is thought to be accelerated along with the moving plate (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967). Evidently, the acceleration drag force is not constant, as opposed to the conventional inviscid added mass force obtained from potential flow, which implies

$A\ell _{{h}}(t)$

that is thought to be accelerated along with the moving plate (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967). Evidently, the acceleration drag force is not constant, as opposed to the conventional inviscid added mass force obtained from potential flow, which implies

![]() $m_{{h}}(t)$

grows during acceleration, and (3.2) would represent a generalized approach where the flow can also be rotational. However, the concept of hydrodynamic mass in (3.2) would also imply that

$m_{{h}}(t)$

grows during acceleration, and (3.2) would represent a generalized approach where the flow can also be rotational. However, the concept of hydrodynamic mass in (3.2) would also imply that

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

vanishes when

$F_{{a}}(t)$

vanishes when

![]() $a=0$

, which is evidently not the case, see figure 1. Therefore, the association of

$a=0$

, which is evidently not the case, see figure 1. Therefore, the association of

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

with a ‘hydrodynamic mass’ does not seem appropriate in this context.

$F_{{a}}(t)$

with a ‘hydrodynamic mass’ does not seem appropriate in this context.

The dimensionless prefactor

![]() $C_ {{a}}$

in (3.1) is rewritten as

$C_ {{a}}$

in (3.1) is rewritten as

where

![]() $a^* = a\ell /V^2$

is the dimensionless acceleration defined with respect to the velocity

$a^* = a\ell /V^2$

is the dimensionless acceleration defined with respect to the velocity

![]() $V$

of the moving plate, and

$V$

of the moving plate, and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

the Reynolds number defined by the velocity

${\textit{Re}}$

the Reynolds number defined by the velocity

![]() $V$

, the plate dimension

$V$

, the plate dimension

![]() $\ell$

and the kinematic viscosity

$\ell$

and the kinematic viscosity

![]() $\nu$

. The constant

$\nu$

. The constant

![]() $C$

is determined experimentally, see § 4.1. It depends on the plate geometry, i.e. AR = 2 rectangular, square or circular plate, but also on the motion; it absorbs the constants

$C$

is determined experimentally, see § 4.1. It depends on the plate geometry, i.e. AR = 2 rectangular, square or circular plate, but also on the motion; it absorbs the constants

![]() $C_n$

, with

$C_n$

, with

![]() $n$

= 1, 2 and 1/2, that arise from the history-based model explained in Appendix B.

$n$

= 1, 2 and 1/2, that arise from the history-based model explained in Appendix B.

Hence, the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

for constant acceleration motion (

$F_{{a}}(t)$

for constant acceleration motion (

![]() $n=1$

),

$n=1$

),

![]() $V(t)=at$

; constant jerk motion (

$V(t)=at$

; constant jerk motion (

![]() $n=2$

),

$n=2$

),

![]() $V(t) = \textstyle (1/2) Jt^2$

; ‘square-root velocity’ motion (

$V(t) = \textstyle (1/2) Jt^2$

; ‘square-root velocity’ motion (

![]() $n=1/2$

),

$n=1/2$

),

![]() $V(t)=Q\sqrt {t}$

, given by the history-based model become

$V(t)=Q\sqrt {t}$

, given by the history-based model become

\begin{equation} F_{{a}}(t) = C_{{a}}\rho A \sqrt \nu \begin{cases} at^{1/2} & n=1,\\ Jt^{3/2} &n=2,\\ Qt^0 &n=\textstyle \dfrac 12. \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} F_{{a}}(t) = C_{{a}}\rho A \sqrt \nu \begin{cases} at^{1/2} & n=1,\\ Jt^{3/2} &n=2,\\ Qt^0 &n=\textstyle \dfrac 12. \end{cases} \end{equation}

When the motions are expressed in terms of

![]() $t^*$

, defined in (1.2), we find

$t^*$

, defined in (1.2), we find

Note that for the square-root velocity motion (

![]() $n$

= 1/2),

$n$

= 1/2),

![]() $t^*$

=

$t^*$

=

![]() $\textstyle ( 2/3)(Q/\ell _b)t^{3/2}$

.

$\textstyle ( 2/3)(Q/\ell _b)t^{3/2}$

.

3.3. Acceleration Reynolds number

The expression in (3.3) can be written as

where

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

is given by

${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

is given by

This definition of an acceleration Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

is convenient since it eliminates the velocity

${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

is convenient since it eliminates the velocity

![]() $V$

, so what is left is a Reynolds number

$V$

, so what is left is a Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

that only depends on acceleration. This Reynolds number is equivalent to the acceleration-based Reynolds number introduced by Freymuth, Bank & Palmer (Reference Freymuth, Bank and Palmer1983) and generalized by Xu & Nitsche (Reference Xu and Nitsche2015) and is equal to the square root of the dimensionless acceleration

${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

that only depends on acceleration. This Reynolds number is equivalent to the acceleration-based Reynolds number introduced by Freymuth, Bank & Palmer (Reference Freymuth, Bank and Palmer1983) and generalized by Xu & Nitsche (Reference Xu and Nitsche2015) and is equal to the square root of the dimensionless acceleration

![]() $\alpha = a \ell ^3 / \nu ^2$

defined by Koumoutsakos & Shiels (Reference Koumoutsakos and Shiels1996).

$\alpha = a \ell ^3 / \nu ^2$

defined by Koumoutsakos & Shiels (Reference Koumoutsakos and Shiels1996).

The dimensionless acceleration

![]() $a^* = a\ell /V^2$

requires further clarification, especially for the non-constant accelerations of the plate. Our point of departure is the Morison equation, which has two terms: one is the quasisteady drag force

$a^* = a\ell /V^2$

requires further clarification, especially for the non-constant accelerations of the plate. Our point of departure is the Morison equation, which has two terms: one is the quasisteady drag force

![]() $F_{\textit{QS}}$

and the other one is the acceleration drag force

$F_{\textit{QS}}$

and the other one is the acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}$

that is due to the acceleration of the surrounding fluid. In the original expression

$F_{{a}}$

that is due to the acceleration of the surrounding fluid. In the original expression

![]() $F_{{a}}$

is taken equal to the inviscid added mass force

$F_{{a}}$

is taken equal to the inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

that is associated with potential flow. For a fully submerged AR = 2 rectangular plate, with

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

that is associated with potential flow. For a fully submerged AR = 2 rectangular plate, with

![]() $A$

=

$A$

=

![]() $\ell _a\times \ell _b$

, the drag coefficient is

$\ell _a\times \ell _b$

, the drag coefficient is

![]() $C_{\!D}$

= 1.3 (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). For thin plates the drag coefficient

$C_{\!D}$

= 1.3 (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019). For thin plates the drag coefficient

![]() $C_{\!D}$

is effectively constant over a large range of Reynolds numbers

$C_{\!D}$

is effectively constant over a large range of Reynolds numbers

![]() ${\textit{Re}} \gg 10^3$

(Hoerner Reference Hoerner1965; Blevins Reference Blevins2003). The inviscid added mass force

${\textit{Re}} \gg 10^3$

(Hoerner Reference Hoerner1965; Blevins Reference Blevins2003). The inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

for a rectangular plate is (Brennen Reference Brennen1982)

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

for a rectangular plate is (Brennen Reference Brennen1982)

The ratio of the added mass force and the quasisteady drag force, with

![]() $C_{\!D}=1.3$

, is then

$C_{\!D}=1.3$

, is then

\begin{equation} \frac {F_{\textit{AM}}}{F_{\textit{QS}}} = \frac {0.84\dfrac \pi 4\rho \ell _a\ell _b^2a}{1.3\times \textstyle \dfrac 12\rho V^2\ell _a\ell _b} = \underbrace {\frac {0.84\dfrac \pi 4}{1.3\times \textstyle \frac 12}}_{1.01}\frac {a\ell _b}{V^2} \cong a^*, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {F_{\textit{AM}}}{F_{\textit{QS}}} = \frac {0.84\dfrac \pi 4\rho \ell _a\ell _b^2a}{1.3\times \textstyle \dfrac 12\rho V^2\ell _a\ell _b} = \underbrace {\frac {0.84\dfrac \pi 4}{1.3\times \textstyle \frac 12}}_{1.01}\frac {a\ell _b}{V^2} \cong a^*, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\ell _b$

is the short dimension of the plate, here referred to as the plate height; the numerical prefactor is close to unity, and therefore ignored here. Hence, the dimensionless acceleration

$\ell _b$

is the short dimension of the plate, here referred to as the plate height; the numerical prefactor is close to unity, and therefore ignored here. Hence, the dimensionless acceleration

![]() $a^*$

can be interpreted as the ratio of the added mass force relative to the quasisteady drag force.

$a^*$

can be interpreted as the ratio of the added mass force relative to the quasisteady drag force.

We can take the same approach for the cases with non-constant accelerations, where both

![]() $a_n$

and

$a_n$

and

![]() $V_n$

vary in time (see table 3), such that for

$V_n$

vary in time (see table 3), such that for

![]() $n=2$

$n=2$

where

![]() $J$

is the jerk in

$J$

is the jerk in

![]() $\rm [m\,s^{-3}]$

and

$\rm [m\,s^{-3}]$

and

![]() $n=1/2$

gives

$n=1/2$

gives

Substituting (3.10) and (3.11) in the definition for

![]() $a^*$

gives

$a^*$

gives

\begin{equation} a^*_2 = \frac {a_2\ell _b}{V_2^2}=\frac {Jt\ell _b}{\frac {1}{4}J^2t^{4}}=\frac {4\ell _b}{J} \frac {1}{t^{3}}, \quad \text{and}\quad a^*_{1/2} = \frac {a_{1/2}\ell _b}{V_{1/2}^2}=\frac {\dfrac {1}{2}Qt^{-1/2}\ell _b}{Q^2t}=\frac {\ell _b}{2Q} \frac {1}{t^{3/2}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} a^*_2 = \frac {a_2\ell _b}{V_2^2}=\frac {Jt\ell _b}{\frac {1}{4}J^2t^{4}}=\frac {4\ell _b}{J} \frac {1}{t^{3}}, \quad \text{and}\quad a^*_{1/2} = \frac {a_{1/2}\ell _b}{V_{1/2}^2}=\frac {\dfrac {1}{2}Qt^{-1/2}\ell _b}{Q^2t}=\frac {\ell _b}{2Q} \frac {1}{t^{3/2}}, \end{equation}

respectively. Evidently, the dimensionless accelerations

![]() $a^*_2$

and

$a^*_2$

and

![]() $a^*_{1/2}$

should be independent of time, and therefore only a function of

$a^*_{1/2}$

should be independent of time, and therefore only a function of

![]() $J$

or

$J$

or

![]() $Q$

, the velocity

$Q$

, the velocity

![]() $V$

and the plate height

$V$

and the plate height

![]() $\ell _b$

. Substituting

$\ell _b$

. Substituting

![]() $V$

back into the time dependent part from (3.12) for

$V$

back into the time dependent part from (3.12) for

![]() $a^*_2$

and

$a^*_2$

and

![]() $a^*_{1/2}$

results in

$a^*_{1/2}$

results in

\begin{equation} a^*_2 = \frac {\sqrt 2 \ell _b}{J^{-1/2}} \frac {1}{\frac {1}{2}^{3/2}J^{3/2}t^{3}} = \frac {\sqrt 2 \ell _b J^{1/2}}{V_J^{3/2}}, \quad \text{and}\quad a^*_{1/2} = \frac {\ell _bQ^{2}}{2} \frac {1}{Q^3t^{3/2}} = \frac {\ell _bQ^{2}} {2V_Q^{3}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} a^*_2 = \frac {\sqrt 2 \ell _b}{J^{-1/2}} \frac {1}{\frac {1}{2}^{3/2}J^{3/2}t^{3}} = \frac {\sqrt 2 \ell _b J^{1/2}}{V_J^{3/2}}, \quad \text{and}\quad a^*_{1/2} = \frac {\ell _bQ^{2}}{2} \frac {1}{Q^3t^{3/2}} = \frac {\ell _bQ^{2}} {2V_Q^{3}}, \end{equation}

respectively. In addition, it is desirable to maintain a numerator that is proportional to

![]() $V^2$

, similar to

$V^2$

, similar to

![]() $a^*$

for constant accelerations, so that in (3.7) the velocity is effectively cancelled in the definition of

$a^*$

for constant accelerations, so that in (3.7) the velocity is effectively cancelled in the definition of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_a$

while maintaining its scaling with the reciprocal of

${\textit{Re}}_a$

while maintaining its scaling with the reciprocal of

![]() $\sqrt {\nu }$

. To ensure this,

$\sqrt {\nu }$

. To ensure this,

![]() $a^*_2$

in (3.13) is raised to the power

$a^*_2$

in (3.13) is raised to the power

![]() $4/3$

and

$4/3$

and

![]() $a^*_{1/2}$

to the power

$a^*_{1/2}$

to the power

![]() $2/3$

,

$2/3$

,

\begin{equation} a^*_2 = \frac {(4\ell _b^4 J^2)^{1/3}}{V^2}, \quad \text{and}\quad a^*_{1/2} = \frac {\left(\dfrac 14\ell _b^2 Q^4\right)^{1/3}}{V^2}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} a^*_2 = \frac {(4\ell _b^4 J^2)^{1/3}}{V^2}, \quad \text{and}\quad a^*_{1/2} = \frac {\left(\dfrac 14\ell _b^2 Q^4\right)^{1/3}}{V^2}. \end{equation}

Finally, these expressions for

![]() $a^*_{n}$

for non-constant accelerations can be used in (3.7) to find specific Reynolds numbers

$a^*_{n}$

for non-constant accelerations can be used in (3.7) to find specific Reynolds numbers

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^n$

for the constant jerk motion and ‘square-root velocity’ motion,

${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^n$

for the constant jerk motion and ‘square-root velocity’ motion,

\begin{equation} {\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^{n=2} = \frac {(2 \ell _b^5 J)^{1/3}}{\nu }, \quad \text{and}\quad {\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^{n=1/2} = \frac {\left(\dfrac 12 \ell _b^4 Q^2\right)^{1/3}}{\nu }. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^{n=2} = \frac {(2 \ell _b^5 J)^{1/3}}{\nu }, \quad \text{and}\quad {\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^{n=1/2} = \frac {\left(\dfrac 12 \ell _b^4 Q^2\right)^{1/3}}{\nu }. \end{equation}

These expressions for the acceleration Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^n$

are used to determine

${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^n$

are used to determine

![]() $C_{{a}}$

for different plate motions with different values for

$C_{{a}}$

for different plate motions with different values for

![]() $Q$

and

$Q$

and

![]() $J$

. The acceleration Reynolds numbers

$J$

. The acceleration Reynolds numbers

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

in (3.3) for the constant-acceleration motion and in (3.15) for the constant-jerk and ‘square-root velocity’ motions, respectively, are each constants during the specified motions. Hence, they can be used for normalizing the acceleration drag forces

${\textit{Re}}_{{a}}$

in (3.3) for the constant-acceleration motion and in (3.15) for the constant-jerk and ‘square-root velocity’ motions, respectively, are each constants during the specified motions. Hence, they can be used for normalizing the acceleration drag forces

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

during each of these motions; this is demonstrated in § 5. They replace the conventional Reynolds number that is defined by the instantaneous velocity, which would constantly change during the motion as the velocity increases during the acceleration phase. In earlier numerical studies of impulsively started plates, i.e. where a plate attains a fixed velocity

$F_{{a}}(t)$

during each of these motions; this is demonstrated in § 5. They replace the conventional Reynolds number that is defined by the instantaneous velocity, which would constantly change during the motion as the velocity increases during the acceleration phase. In earlier numerical studies of impulsively started plates, i.e. where a plate attains a fixed velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

for

$V_{{a}}$

for

![]() $t\gt 0$

, the velocity-based Reynolds number is used to characterize the flow. In this case the plate velocity is increased discontinuously, and the plate does not experience an acceleration phase. This motion is not physical, and in reality any plate that starts to move from rest towards a certain final velocity

$t\gt 0$

, the velocity-based Reynolds number is used to characterize the flow. In this case the plate velocity is increased discontinuously, and the plate does not experience an acceleration phase. This motion is not physical, and in reality any plate that starts to move from rest towards a certain final velocity

![]() $V_{{a}}$

must experience a finite-duration acceleration phase where the velocity of the plate remains continuous.

$V_{{a}}$

must experience a finite-duration acceleration phase where the velocity of the plate remains continuous.

4. Constant-acceleration motion

4.1. Acceleration phase

The numerical value of the proportionality constant

![]() $C$

in (3.1), and consequently

$C$

in (3.1), and consequently

![]() $C_{{a}}$

in (3.3), is found by a least-squares fit of the model to the measured acceleration drag force

$C_{{a}}$

in (3.3), is found by a least-squares fit of the model to the measured acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

=

$F_{{a}}(t)$

=

![]() $F_D(t)\!-\!F_{\textit{QS}}(t)$

during the acceleration phase for all measurements in table 2. Figure 6 compares the model with the corresponding fit of

$F_D(t)\!-\!F_{\textit{QS}}(t)$

during the acceleration phase for all measurements in table 2. Figure 6 compares the model with the corresponding fit of

![]() $C_{{a}} = C {\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^{1/2}$

in (3.1) with the measured acceleration drag force

$C_{{a}} = C {\textit{Re}}_{{a}}^{1/2}$

in (3.1) with the measured acceleration drag force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

during a constant-acceleration motion with acceleration

$F_{{a}}(t)$

during a constant-acceleration motion with acceleration

![]() $a = 1.03\,{\textrm {m}\,\textrm {s}^{-2}}$

and final velocity

$a = 1.03\,{\textrm {m}\,\textrm {s}^{-2}}$

and final velocity

![]() $V_{{a}} = 0.75\,\textrm {m}\,\textrm {s}^{-1}$

. Figure 6 shows that the force

$V_{{a}} = 0.75\,\textrm {m}\,\textrm {s}^{-1}$

. Figure 6 shows that the force

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

grows proportional to

$F_{{a}}(t)$

grows proportional to

![]() $t^{1/2}$

, or equivalently

$t^{1/2}$

, or equivalently

![]() $(t^*)^{1/4}$

, see (3.5). Evidently

$(t^*)^{1/4}$

, see (3.5). Evidently

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

exceeds the (constant) inviscid added mass force

$F_{{a}}(t)$

exceeds the (constant) inviscid added mass force

![]() $F_{\textit{AM}}$

. Note that

$F_{\textit{AM}}$

. Note that

![]() $F_{{a}}$

at

$F_{{a}}$

at

![]() $t^* = 0$

increases almost discontinuously to the value of

$t^* = 0$

increases almost discontinuously to the value of

![]() $F_{AM}$

. This implies that no distinction can be made between the inviscid added mass

$F_{AM}$

. This implies that no distinction can be made between the inviscid added mass

![]() $F_{AM}$

and the history-based model for

$F_{AM}$

and the history-based model for

![]() $F_{{a}}(t)$

at the start of the motion.

$F_{{a}}(t)$

at the start of the motion.

When the acceleration ceases and the plate assumes a constant velocity, there is an apparent sharp drop

![]() $\Delta F$

in

$\Delta F$

in

![]() $F_{{a}}$

. The magnitude of this drop is also predicted by the model, but is not included in the fitting of the model. This is further discussed in § 4.3.

$F_{{a}}$

. The magnitude of this drop is also predicted by the model, but is not included in the fitting of the model. This is further discussed in § 4.3.

The resulting values of

![]() $C_{{a}}$

defined according to (3.3) for accelerations

$C_{{a}}$

defined according to (3.3) for accelerations

![]() $a$

between 0.41 and 1.64 m s−2 and final velocities

$a$

between 0.41 and 1.64 m s−2 and final velocities

![]() $V_{{a}}$

between 0.30 and 1.35 m s−1 are shown in figure 7. The curves in the graph represent

$V_{{a}}$

between 0.30 and 1.35 m s−1 are shown in figure 7. The curves in the graph represent

![]() $C_{{a}}$

in (3.3), with

$C_{{a}}$

in (3.3), with

![]() $C$

= 1.5 for different values of the Reynolds number

$C$

= 1.5 for different values of the Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

=

${\textit{Re}}$

=

![]() $V_{{a}}\ell _b/\nu$

, where

$V_{{a}}\ell _b/\nu$

, where

![]() $V_{{a}}$

is the final plate velocity at the end of the acceleration phase. This result supports the scaling of

$V_{{a}}$

is the final plate velocity at the end of the acceleration phase. This result supports the scaling of

![]() $C_{{a}} \propto (a^*)^{1/4}$

; this rather weak dependence results in a nearly constant value for

$C_{{a}} \propto (a^*)^{1/4}$

; this rather weak dependence results in a nearly constant value for

![]() $C_{{a}}$

for the measurements represented in figure 7. These results replace the results previously presented by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023), where

$C_{{a}}$

for the measurements represented in figure 7. These results replace the results previously presented by Reijtenbagh et al. (Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023), where

![]() $C_{{a}}$

was considered to be constant for the range of Reynolds numbers

$C_{{a}}$

was considered to be constant for the range of Reynolds numbers

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

and values of the dimensionless acceleration

${\textit{Re}}$

and values of the dimensionless acceleration

![]() $a^*$

for the 200

$a^*$

for the 200

![]() $\times$

100 mm

$\times$

100 mm

![]() $^2$

rectangular plate and different constants

$^2$

rectangular plate and different constants

![]() $C_{{a}}$

for circular and square plates. The values for

$C_{{a}}$

for circular and square plates. The values for

![]() $C$

in

$C$

in

![]() $C_{{a}}$

for different geometries are described in § 4.2.

$C_{{a}}$

for different geometries are described in § 4.2.

Figure 6. The measured acceleration drag force