In their landmark book written 30 years ago Can We All Get Along? McClain and Stewart Jr. identified political coalitions among racial-ethnic minorities as a promising strategy for addressing race-based inequality in the United States. However, as they noted then, the formation of cross-racial political alliances poses its own complications because the shared minority group status that “may be the bases for building coalitions … may also generate conflict” (McClain and Stewart Reference McClain and Stewart1995, 3). This article gauges the current prospects for the emergence of a cross-racial political coalition between Latinxs, the largest racial-ethnic minority group in the country, and Black Americans, identifying factors that facilitate and stymie such partnerships.

As a racialized group subject to discrimination, US Latinxs are often considered “natural” coalitional partners for Black-led civil rights struggles.Footnote 1 However, the internal heterogeneity of the Latinx population in terms of ethnic background, phenotype, and acculturation means that Latinxs experience and interpret discrimination differently, which can influence their racial identity and complicate the formation of cross-racial alliances. This set of circumstances prompt the following research question of this study: How do multiple dimensions of group identity—perceptions of discrimination, intra- and intergroup commonality, and elements of racial group consciousness—shape Latinxs’ perceptions of a shared struggle with Black Americans? Answering this question is important to better discern where Latinxs stand on the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and potentially other Black-led campaigns for racial justice. I find that although some of Latinxs’ personal experiences with discrimination (especially at the hands of police) are associated with increased support for the BLM movement, it is those Latinxs with a consciousness of Blacks’ struggle with racial discrimination in the United States and within Latinx communities and those who report a sense of commonality with Blacks who are most consistently inclined to support multiracial social justice efforts.

LATINX–BLACK POLITICAL COALITION BUILDING: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Previous scholarship of Latinx–Black coalition building (for a review, see Ocampo and Flippen Reference Ocampo and Flippen2021) has documented various factors that make Latinxs less inclined to perceive a sense of commonality with Blacks (Gay Reference Gay2006; Marrow Reference Marrow2011; McClain et al. Reference McClain, Carter, Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally and Scotto2006; Mindiola, Niemann, and Rodriguez Reference Mindiola, Niemann and Rodriguez2002; Pérez, Robertson, and Vicuña Reference Pérez, Robertson and Vicuña2023; Vaca Reference Vaca2004). A common thread uniting one set of findings in the literature is that anti-Black stereotypes prevalent among Latinx immigrants who are still undergoing the acculturation process in US society heighten perceptions of difference and conflict with Blacks. In a groundbreaking study of Latinx immigrant views of Blacks in North Carolina, McClain and coauthors (Reference McClain, Carter, Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally and Scotto2006, 582) found that because of “Latino immigrants’ negative views of black Americans, most likely brought with them from their home countries and reinforced, rather than reduced, by neighborhood interactions with blacks,” Latinx immigrant newcomers engaged in a “distancing” strategy from Blacks.

Although the thrust of McClain et al.’s (Reference McClain, Carter, Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally and Scotto2006) findings painted a skeptical picture of Latinx–Black coalitions, importantly that study also echoed previous findings by Kaufmann (Reference Kaufmann2003, 579) showing that linked fate served as a “robust corrective to negative stereotypes of Blacks” among those same Latinx immigrants. One way that Latinxs in the United States develop a sense of Latinx group consciousness is through the acculturation process, which involves personal experiences with discrimination and the growing awareness of anti-Latinx bias in various aspects of US society (Masuoka Reference Masuoka2006; Sanchez and Rodriguez Espinosa Reference Sanchez and Espinosa2016; Sanchez, Masuoka, and Abrams Reference Sanchez, Masuoka and Abrams2019). In this sense, entrenched practices of racial profiling by police and immigration enforcement that target people of color and immigrants alike are one way that more Latinxs could come to view Black-led campaigns for racial justice like the BLM movement as beneficial to the pursuit of greater equality for Latinxs as well.

Statistics documenting how the excessive use of force by police is also borne disproportionately by Latinxs suggests that criminal justice reform efforts could also benefit Latinxs, despite media and popular discourse framing police brutality as a singularly Black issue (Salinas Reference Salinas2015). For example, although the number of police shootings involving Latinxs are not as high on a per-capita basis as they are for Blacks, Latinxs are killed by police at nearly double the rate of White Americans (Foster-Frau Reference Foster-Frau2021; Nguyen Reference Nguyen2025).Footnote 2 Similarly, an analysis of New York City Police Department’s controversial “stop-and-frisk” program found that of the five million pedestrian stops between 2002 and 2019, Blacks and Latinxs represented 85% of those stopped, despite comprising only about half the city’s population (Levchak Reference Levchak2021). As described presciently by Sawyer (Reference Sawyer, Dzidzienyo and Oboler2005, 275), addressing systemic racism in policing and mass incarceration represents a potentially fertile ground for Latinx–Black coalition building because “both communities share this burden equally” and reforming the criminal justice system is a place where there is “no divergence of interests.”

The BLM movement’s transformation from demonstrations against the routine lack of accountability for citizens and police who kill unarmed Black people into a global social movement against systemic racism and anti-Blackness has served as an important test case for interminority coalition building. Findings from both qualitative and quantitative studies suggest that Latinxs are more likely to join Blacks in coalitions when they feel a sense of “shared status.” For example, Jones’s (Reference Jones2019) ethnographic case study exploring race relations in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, highlights how the racialization and targeting of previously welcomed Latinx immigrants during the anti-immigrant hysteria following 9/11 led both Latinxs and Blacks to recognize their common experiences battling racialized exclusion. Rather than the descent into conflict typically thought to occur in the wake of rising anti-immigrant sentiment, Jones traces how community leaders successfully strengthened ties between Latinx and Black communities.

A major issue within the literature of Latinx–Black relations is the trap of the “contention-cohesion binary” that oversimplifies the nuanced realities of interminority coalitions, which are often issue-based and geographically contingent (Dhuman Reference Dhuman2025). Increasingly, research finds that zero-sum issues like economic competition between groups for employment, housing, and education resources pose unfavorable conditions for forging cross-racial coalitions. For example, one study found that framing racial disparities in education and housing resources as Black and Latino versus White did not promote feelings of commonality (Israel-Trummel and Schachter Reference Israel-Trummel and Schachter2019). Instead, nonzero-sum issue domains like criminal justice reform proposed by the BLM movement have been found to be the most fruitful for interminority coalition building because Latinxs and Blacks are both poised to benefit from policy changes. Indeed, Hurwitz, Peffley, and Mondak (Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015, 512) find that both Latinxs and Blacks “interpret the justice system in essentially the same way” and that Latinxs “report that blacks are the most victimized group in the country.” This suggests that Latinxs are likely a supportive audience for considering policy reforms proposed by Black-led social movements because they recognize the distinct, yet sufficiently similar, echoes of anti-Latinx discrimination. Two different experimental studies found that Latinx respondents who read an article highlighting how Blacks are viewed as “second-class individuals, similar to many Latino people” exhibited a greater sense of cross-racial solidarity (or “shared status”) that then increased their endorsement of the BLM movement (Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Vicuña and Ramos2024a, Reference Pérez, Vicuña and Ramos2024b).

TOWARD A SHARED STRUGGLE: THE THEORETICAL ROLE OF DISCRIMINATION AND IDENTITY IN LATINX–BLACK COALITION BUILDING

Theoretically, my expectations about Latinxs’ inclination to form coalitions with Blacks are grounded in insights from both Race and Ethnic Politics research and political psychology, which suggest that Latinxs’ perceptions and interpretations of anti-Latinx and anti-Black discrimination serve as critical building blocks for Latinx–Black coalitions. First, according to Masuoka and Junn’s (Reference Masuoka and Junn2013, 25) “racial prism of group identity” theory, racial-ethnic minorities in the United States experience conditional membership, which increases their awareness of racial hierarchies such that “who one is racially, where one’s group is positioned relative to others, and what stereotypes are associated with one’s group systematically structure political attitudes.” On the role of discrimination specifically, Masuoka and Junn contend that movement along the racial hierarchy along the dimensions of national membership (insider/outsider) and status (superior/inferior) is informed not only by the power of prevailing cultural stereotypes that reinforce positions but also by what they refer to as “hierarchy enhancing practices” (24). Hierarchy enhancing practices can be understood as practices of racial discrimination that occur either interpersonally or, more importantly for the purposes of this research, at the institutional level by the nation’s law and immigration enforcement systems.

Second, linking Latinx racial identity to perceptions of a shared struggle with Blacks also requires considering certain tenets of the common ingroup identity model (CIIM; Gaertner and Dovidio Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2000). The CIIM proposes that, contrary to experiences of social identity threat, the increased salience of group discrimination might instead trigger a common ingroup identity. Extensions of the CIIM by Craig and Richeson (Reference Craig and Richeson2012, 762) into the study of Latinx–Black populations have found that “Blacks and Latinos who perceive that they or their racial/ethnic group faces discrimination tend also to believe that the experience of discrimination is something that they have in common with the other racial/ethnic minority group.” These findings suggest that Latinxs and Blacks may well choose to respond to experiences of discrimination by embracing, rather than derogating, one another. This “same team” effect forms the basis of recent findings showing that the immigrant experience among Latinxs may induce coalitional behavior with Blacks.

What links Masuoka and Junn’s (Reference Masuoka and Junn2013) “racial prism of group identity” theory with the tenets of the common ingroup identity model is that shared status across group boundaries can be developed based on either personal experiences with discrimination or the recognition of group-level discrimination. The latter has been found to be particularly important for increasing perceptions among Latinxs that Blacks as a group experience discrimination (Warren and Valentino Reference Warren and Valentino2025). Following Jones’s (Reference Jones2022) “theory of racial status,” which holds that shared status only emerges when members of different ethnoracial groups come to believe that both groups have experienced discrimination, Warren and Valentino (Reference Warren and Valentino2025) find that Latinxs are the only group—Whites and Asians do not show this effect—in which perceptions of Latinx group-level discrimination produce increased perceptions that Blacks also experience discrimination.

Based on the insights from the racial prism of group identity and the CIIM, I forward the following two hypotheses regarding Latinxs’ perceptions of the BLM movement:

H1a: Group-level discrimination hypothesis. Group-level perceptions of societal discrimination toward Latinxs will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

H1b: Personal discrimination hypothesis. Personal experiences with discrimination will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

The next set of hypotheses relate to the role played by intra- and intergroup commonality among Latinxs in shaping views of a shared struggle against racial injustices. Previous work has found that measures of Latinx ingroup commonality are associated with lower levels of negative Black stereotypes (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Carter, Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally and Scotto2006), more liberal views of the criminal justice system (Hurwitz, Peffley, and Mondak Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015), and greater commonality with Blacks (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003; Sanchez Reference Sanchez2008). Therefore, I expect that both inter- and intragroup commonality will shape views of the BLM movement in the following ways:

H2a: Intergroup commonality hypothesis. Latinx intergroup commonality with Blacks will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

H2b: Intragroup commonality hypothesis. Latinx intragroup commonality with other Latinxs identity will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

Variations in Latinxs’ racial attitudes about their own identities and sense of the problem of anti-Blackness within the Latinx community will likely also influence dispositions toward the BLM movement. The three measures of Latinx racial attitudes and identity explored in the subsequent analysis relate to systemic forms of racism and include (1) the belief that anti-Black racism is a problem in the Latinx community, (2) the belief that Latinxs as a pan-ethnic group represent a distinctive racial category, and (3) the centrality of racial identity to a person’s life.

The first measure about anti-Blackness in Latinx communities is included because ideologies in service of whiteness like racial resentment and colorblindness have been shown to be important factors for shaping the partisanship and voting behavior of Latinxs (Alamillo Reference Alamillo2020; Beltrán Reference Beltrán2021; Cuevas-Molina Reference Cuevas-Molina2023). Although not a measure of a respondent’s anti-Black sentiment per se, I believe this construct taps a theoretically important racial attitude: Latinxs’ willingness or predisposition to acknowledge how various racial mythologies that predominate in Latin America, like mestizaje and blanqueamiento, work to erase the African presence in Latin America genealogy and culture (Haywood Reference Haywood2017). The expectation here is that an inclination to adopt a critical stance regarding anti-Blackness in Latinidad might be correlated with other efforts to correct a history of racial injustice.

The second measure, group-level racialized identity, is included because it has been shown to be associated with increased support for coalition with Blacks in the struggle against racism (Cardenas, Silber Mohamed, and Michelson Reference Cardenas, Mohamed and Michelson2023). For the third measure—personal-level racial identity—I expect that stronger Latinx racial identity will correspond to increased support for the BLM movement.

H3a: Group-level racial attitudes. The perception that anti-Black racism is a major problem within the Latinx community will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

H3b: Group-level racial identity. The perception that Latinxs constitute a distinct racial group will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

H3c: Personal racial identity. Stronger personal Latinx racialized identity will be associated with an increased likelihood of positive and supportive orientations toward the BLM movement.

DATA ANALYSIS

To test my proposed hypotheses, I analyzed the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) because it includes a large enough sample of Latinxs (N = 4,006) and other racial minorities for subgroup analysis (Frasure et al. Reference Frasure, Wong, Barreto and Vargas2021). The CMPS is a postelection survey that was collected in a self-administered online format between April 2 and August 25, 2021.

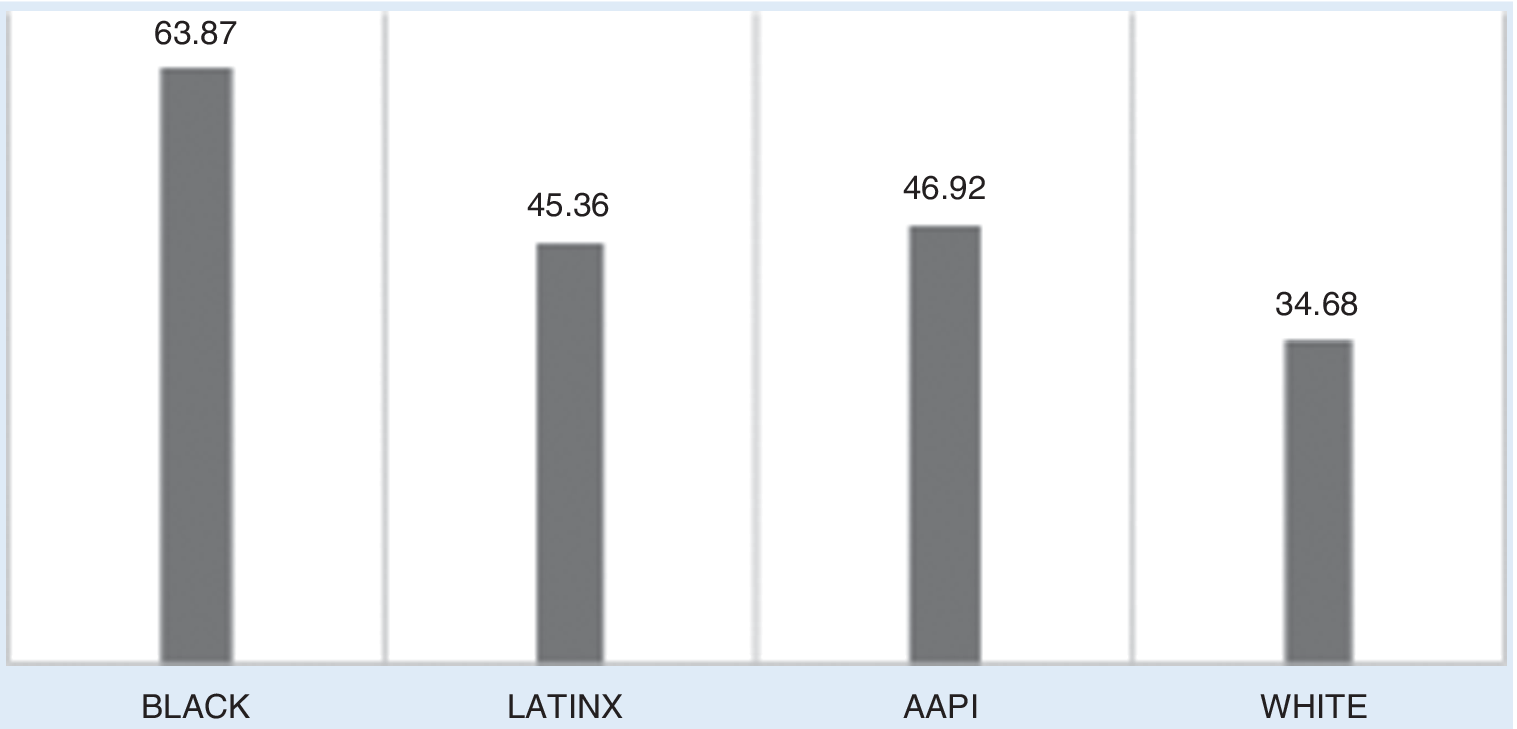

A preliminary examination of this study’s four dependent variables involved measuring Latinxs’ dispositions toward the BLM movement and levels of personal and group support for it. The bar graph in figure 1 displays a feeling thermometer measure of the BLM movement across racial groups and indicates that Latinx respondents rate it somewhat coolly: they register just below the 50-degree mark on the 0–100 scale. That said, the feeling thermometer score for Latinxs (though almost identical to that of AAPI respondents) is almost 11 degrees warmer than that of Whites.

Figure 1 Black Live Matters Feeling Thermometer

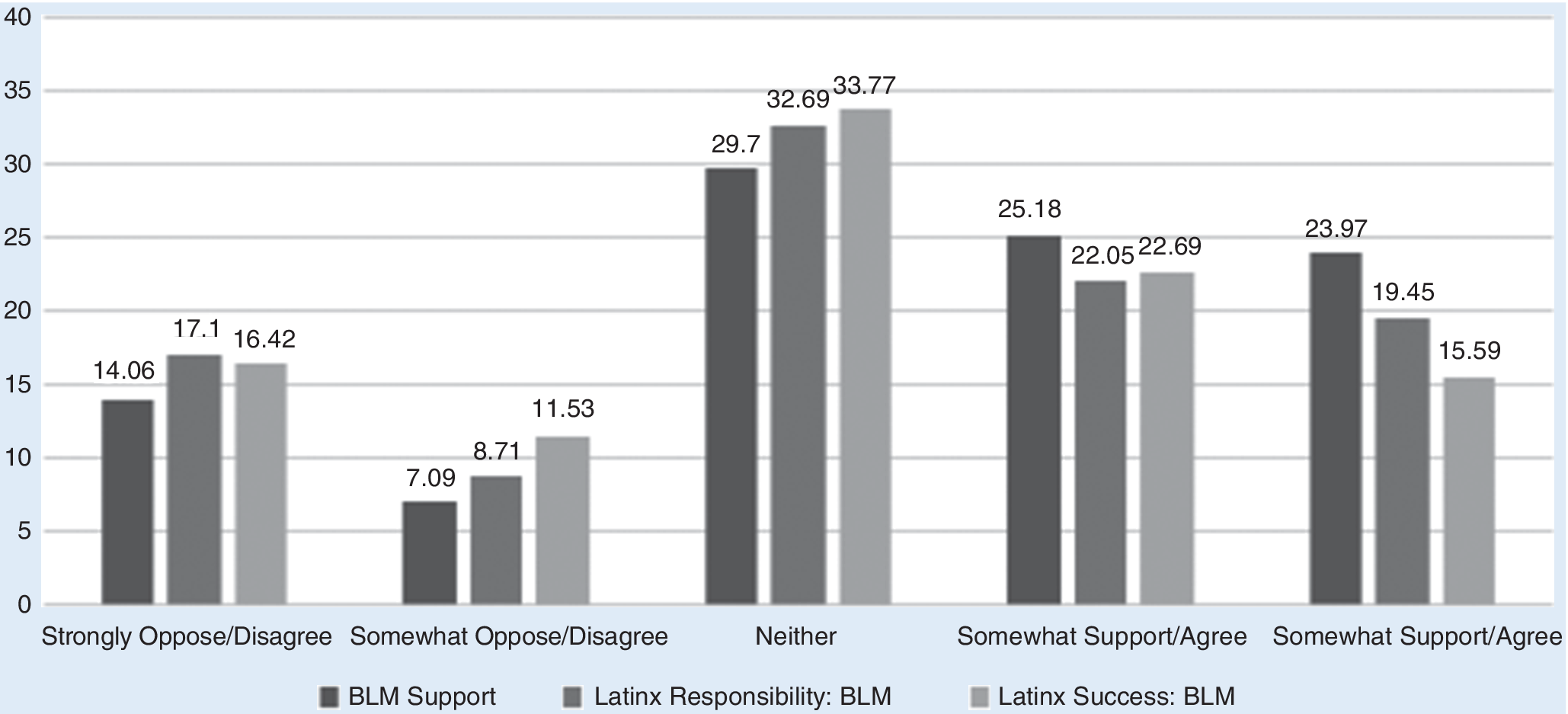

Figure 2 shows the results for only Latinx respondents on three other questions about the BLM movement. The three questions asked respondents to rate (1) their support for the BLM movement, (2) the degree to which their racial group (in this case, Latinxs) “have a responsibility to support the Black Lives Matter movement,” and (3) whether Latinxs “will benefit from the success of the Black Lives Matter movement.” All three questions are coded on the same 5-point scale from strongly oppose/disagree to strongly support/agree (see the methodological appendix for question wording, coding, and descriptive statistics presented in table A1). Results show that approximately half (49.15%) of Latinxs support the BLM movement, whereas slightly smaller shares of the Latinx sample, though still pluralities, agree with the statements about Latinxs’ responsibility to support the BLM movement or that Latinxs as a group were poised to benefit from the movement’s success (41.5% and 38.28%, respectively). About one-third of Latinxs occupy the neutral space of neither opposing nor supporting the BLM movement, and smaller shares of Latinxs (ranging from one-fifth to one-quarter) report opposition to its goals or disagree with the proposition that their racial group has a duty to support the movement or view its success as beneficial to Latinxs. In sum, the Black community likely has far more allies than adversaries among Latinxs regarding this criminal justice reform effort, which comports with McClain and Johnson Carew’s (Reference McClain and Carew2018, 273) broad characterization of the state of minority coalitions as “one of realistic limitations and cautious optimism.”

In sum, the Black community likely has far more allies than adversaries among Latinxs regarding this criminal justice reform effort, which comports with McClain and Johnson Carew’s (Reference McClain and Carew2018, 273) broad characterization of the state of minority coalitions as “one of realistic limitations and cautious optimism.”

Figure 2 Latinx Support for BLM Movement (%)

Multivariate Analysis

To test the expectations outlined in my hypotheses, I then conducted a multivariate analysis on my four dependent variables. In addition to exploring the effect of my key independent variables, I also included a range of demographic and political variables as controls because they might also be associated with Latinxs’ propensity to engage in multiracial coalition building with Blacks (see table A2 for complete regression results). Demographic controls include a categorical variable for the 9% (n = 358) of Latinxs who identify as “Afro-Latino” in the sample, given that previous research suggests that these individuals may be more likely to support Black-led racial justice causes (Corral Reference Corral2020; Hordge-Freeman and Loblack Reference Hordge-Freeman and Loblack2021). Also included as controls are a self-reported skin tone measure, given that variation in Latinx phenotype has been shown to inform a range of political attitudes (Ostfeld and Yadon Reference Ostfeld and Yadon2022; Stokes-Brown Reference Stokes‐Brown2012), and standard controls meant to capture unique aspects of immigrant acculturation attitudes including national ancestry and generational status. Other demographic factors included in the analysis are gender, age, income, and religious affiliation. Political control variables include political ideology and partisanship scales, on which higher values correspond to stronger conservatism and Republican affiliation.

Table 1 displays the results of ordinary least squares regression for the first outcome variable of the BLM feeling thermometer (first column); the results from ordered logistic regression are presented in the three rightmost columns for the questions concerning Latinxs’ support for and role in the BLM movement. For ease of interpretation, coefficients displayed in columns 2–4 are exponentiated as odds ratios, such that significant values above 1 denote positive relationships and values below 1 denote negative relationships between independent and dependent variables.

Table 1 Predicting Latinx Views of Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement, CMPS 2020

Notes: Odds ratios = exp. coefficients; std. errors in parentheses; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

See methodological appendix for full table showing full regression models inclusive of all control variables.

Beginning with the role of group-level discrimination (H1a), I find some support for the expectation that group-level discrimination perceptions are positively associated with support for the BLM movement. Although Latinxs with heightened perceptions of group-level discrimination toward their own racial group are likely to support the BLM movement in only one of the four dependent variables (Latinxs will benefit from the success of the BLM movement), the results regarding Latinxs’ belief in Black group-level discrimination are much stronger, given that they are consistently predictive of support for the BLM movement across all four models. To take just one example, a one-unit increase on that 4-point scale corresponds to a nearly 8-point movement toward the BLM movement in the warmer direction.

The left panel of figure 3 displays the predicted probabilities of reporting the most supportive outcome on each scale from the ordered logit models corresponding to table 1: it shows that movement on the Black group discrimination scale from the minimum to the maximum yields a 22% increase in support for the BLM movement (“support”), a 10% increase in the probability of believing that Latinxs have a responsibility to support the movement (“responsibility”), and a 9% increase in the probability that Latinxs would benefit from its success (“benefit”).

Figure 3 Predicted probabilities of reporting the most supportive outcome on each scale (“strongly support” for “BLM Support” and “strongly agree” for “Responsibility” and “Benefit”)

Notes: The figure corresponds to ordered logit models from Table 1 in which independent variables were statistically significant. Predicted probabilities were derived with all continuous variables held at their means and dummy variables held at their modal outcomes.

I also find some support for the hypothesis that Latinxs’ direct experience with racial discrimination (H1b) is correlated with increased support for the BLM movement. Of the two measures—discrimination experiences at the hands of immigration officials or of police—the latter is far more predictive. Although the variable for personal experiences with race-based discrimination with immigration officials is only positive and significant for believing that Latinxs as a group have a responsibility to support the BLM movement, the measure for personal experiences with racial discrimination by the police is predictive in the three ordered logit models. The right panel of figure 3 shows that experiences with racial discrimination by police translate to modest increases in predictive probabilities across the “support,” “responsibility,” and “benefit” dependent variables of about 7%, 4%, and 2% percent, respectively.

Results show strong support across all four models for the intergroup commonality hypothesis (H2a), which posits that Latinxs expressing higher levels of perceived commonality between Latinxs as a group and Blacks are more likely to engage in cross-racial coalitions. For example, a one-unit increase on that 4-point scale is linked to a 6-point movement in the warmer direction. The left panel of figure 4 shows that going from the minimum to the maximum on the Latinx-Black Commonality scale produces 22%, 23%, and 13% increases in predicted probabilities across the “support,” “responsibility,” and “benefit” dependent variables, respectively.

Figure 4 Predicted probabilities of reporting the most supportive outcome on each scale (“strongly support” for “BLM Support” and “strongly agree” for “Responsibility” and “Benefit”).

Notes: The figure corresponds to ordered logit models from Table 1 in which independent variables were statistically significant. Predicted probabilities were derived with all continuous variables held at their means and dummy variables held at their modal outcomes

Interestingly, contrary to expectations and previous findings by Sanchez (Reference Sanchez2008), Latinxs with higher levels of intragroup commonality (H2b) are less likely to engage in cross-racial coalitions in two of the four outcome variables. Latinxs who consider themselves to share a lot in common with other Latinxs in terms of job opportunities, income, and educational attainment are less likely to support the BLM movement (O.R. 0.90, p = < .05) or to think that Latinxs as a group have a responsibility to support it (O.R. 0.80, p = < .001). One potential interpretation of this result is that those who express strong intragroup commonality do so at the expense of recognizing shared commonality with outgroups. By shrinking their sense of shared experience to a limited racial-ethnic circle, some Latinxs may contribute to the group’s balkanization.

In terms of results concerning the role of racial attitudes, I find strong support for the group-level racial attitudes hypothesis (H3a): those Latinxs who consider anti-Blackness to be a problem within their own racial community are more likely to be positively oriented toward the BLM movement across all four dependent variables. For example, a one-unit increase in the scale measuring the severity of anti-Black racism within the Latinx community is associated with a 2-percentage point warming in the BLM feeling thermometer. The right panel of figure 4 shows that going from the minimum to the maximum on the Anti-Black Racism in the Latinx Community scale produces 18%, 19%, and 12% increases in predicted probabilities across the “support,” “responsibility,” and “benefit” dependent variables, respectively. This result suggests that those Latinxs who acknowledge how their group can often be complicit in anti-Blackness (Hernández Reference Hernández2022) are more willing to enter multiracial coalitions with Blacks on matters of racial justice. The multivariate analysis, however, produced null results for the group-level racial identity hypothesis (H3b), whereas support for the personal racial identity hypothesis (H3c) remained tentative: it was only positive and statistically significant in one of the four outcome variables.

The control measures did produce a few interesting results that identified certain demographic groups within the broader Latinx community that are both more and less amenable to coalition building with Blacks. First, Afro-Latinxs were more likely to agree that Latinxs as a group have a responsibility to support the BLM movement. This finding supports the call by Sawyer (Reference Sawyer, Dzidzienyo and Oboler2005, 274) for both scholars of Black and Latinx politics to adopt a “diasporic lens” that appreciates the ways that Afro-Latinxs as a group “represent a space for greater cross-cultural understanding or the tragedy of missed opportunity.” With a few exceptions showing that Central Americans and those Latinxs identifying their ancestry as “Spanish”/“other” were on occasion less likely than Mexican-origin Latinxs to support the BLM movement, most national-origin differences were statistically insignificant. In terms of gender differences, results show that compared to Latinas (reference group), Latino men are less likely to rate the BLM movement warmly and to express support for it. This contrasts with the results for those Latinxs respondents who identify as nonbinary: in three of the four models, they are more likely than Latinas to report pro-Black coalitional attitudes. These gender differences fit with findings from extant literature suggesting a gender gap between Latinas and Latino men on certain issues and that LGBTQIA+ Latinxs may also be politically distinct (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014; Montoya Reference Montoya1996; Morneau, Nuño-Pérez, and Sanchez Reference Moreau, Nuño-Pérez and Sanchez2019). Results also showed strong and consistent evidence that Latinxs with college degrees were consistently more likely to support the BLM movement, whereas older Latinxs were consistently less likely to support it. Lastly, movement on both the ideological and partisanship spectrums toward conservativism and Republican affiliation were strongly associated with decreased support for the BLM movement.

DISCUSSION

This study showed how multiple dimensions of group identity shape Latinxs’ perceptions of a shared struggle with Blacks against continued patterns of racial injustice. Although Latinxs cannot be said to support the BLM Movement at levels on par with Black Americans, the analysis revealed that Latinxs (along with Asian Americans) rate the BLM Movement more warmly than Whites and that about half of all Latinxs report supporting the movement’s goals.

Although Latinxs cannot be said to support the BLM movement at levels on par with Black Americans, the analysis revealed that Latinxs (along with Asian Americans) rate the BLM movement more warmly than Whites and that about half of all Latinxs report supporting the movement’s goals.

Results from multivariate analyses relying on the Latinx sample from the 2020 CMPS data yielded three primary contributions. First, those Latinxs who are cognizant of Blacks’ struggle with racial discrimination as a group were more likely to be positively oriented toward the BLM movement and to perceive that Latinxs have a role to play in it and can share in its potential success. Recognition of Latinxs’ group-level discrimination was a less consistent predictor of support for the BLM movement, although having firsthand experience with racially discriminatory mistreatment by police was a predictive factor in three of the four models. The second major finding relates to the contrasting effects for inter- and intragroup commonality: the former (Latinxs’ commonality with Blacks) is strongly and consistently predictive of support for the BLM movement across all four dependent variables, whereas the latter (Latinxs’ commonality with other Latinxs) was negatively associated with support for the movement in two of the four models. The third important finding is that Latinxs who are critical of Latinidad’s complicity in reproducing anti-Blackness within the community are also more likely to support the BLM movement. Taken together, these findings suggest that Latinxs who are more cognizant of Black Americans’ continuing struggle against racial discrimination in American society and within the Latinx community are more willing to back the movement for racial justice and that perceptions of commonality across lines of race-ethnicity are associated with support for multiracial social justice movements among Latinxs.

These findings suggest that Latinxs who are more cognizant of Black Americans’ continuing struggle against racial discrimination in American society and within the Latinx community are more willing to back the movement for racial justice and that perceptions of commonality across lines of race-ethnicity are associated with support for multiracial social justice movements among Latinxs.

Future research should address the surprising finding about the contrasting effects of inter- and intragroup commonality. Contrary to previous findings by Sanchez (Reference Sanchez2008), higher levels of intragroup commonality among Latinxs were associated with lower levels of support for the BLM movement. An open question is whether and how the ingroup bonds of commonality may exist in tension with multiracial coalitions. Therefore, future studies should explore whether group-level discrimination may unintentionally drive the sort of group balkanization that shrinks people of color’s capacity to extend empathetic responses to other minoritized groups.

A methodological limitation of this study is that its reliance on cross-sectional survey data makes disentangling causal directionality difficult. That said, the inclusion of a wide array of statistical controls that grasp the heterogeneity of the Latinx experience in the United States, as well as the statistical power provided by a large, multilingual sample of Latinx individuals, should bolster confidence in these results. Future work on this topic using qualitative interview data or experimental methods could offer valuable insights about how Latinxs understand the barriers and opportunities to building cross-racial alliances with Black Lives Matter or other movements.

CONCLUSION

Although initial studies of Latinx–Black coalition building were skeptical that Latinxs would enter coalitional partnerships with Blacks based on notions of intergroup conflict (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Carter, Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally and Scotto2006), this work joins the growing literature identifying various social conditions favorable to the emergence of Latinx–Black coalitions (Cardenas, Silber Mohamed, and Michelson Reference Cardenas, Mohamed and Michelson2023; Corral Reference Corral2020; Jones Reference Jones2019; Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Robertson and Roman Reference Robertson and Roman2024; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015). The major contribution of this work is its conclusion that Latinxs’ awareness of the Black struggle against racial discrimination along multiple fronts and of their group’s commonality with Blacks leads to increased support for multiracial social movements. However, building a political partnership across group boundaries may well hinge on Latinxs’ interpretation of their own experiences with racial discrimination as individuals and as members of a minoritized group.

The substantive significance of these and other findings herein underscore both the challenges and opportunities of creating an influential Latinx–Black political coalition. Given that perceptions of group-level discrimination were shown to be important avenues toward building a sense of a shared struggle with Blacks, those looking to build multiracial coalitions should consider increasing Latinxs’ awareness of systemic forms of racism faced by their ingroup, as well as by other minorities. The success of the Black-led BLM movement implies the need for allyship across lines of race so that a larger, multiracial coalition can exert pressure on state and local policy makers on issues related to social justice and civil rights. As this analysis has shown, the emergence and solidification of cross-racial alliances between Latinxs and other racially minoritized groups in the United States are central to the future trajectory of American politics.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525101790.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QXCJYY (see Corral Reference Corral2025).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.