Joining the WTO was a major challenge for China in 2001. The conditions for China being a WTO member were broad, deep and even demanding. For its WTO accession, China made significant concessions. Beyond general WTO commitments for all the WTO memberships, there were some tailor-made provisions incorporated into China’s accession to the WTO agreement, stipulating certain WTO-plus obligations and WTO-minus rights (Qin, Reference Qin2010). It was not easy for China to fulfil such a grand international obligation in its entirety. However, the Chinese government took the challenge of WTO accession as an opportunity to promote domestic reform and opening up and made great efforts in studying and implementing WTO rules.

I China’s Overall Implementation of WTO Commitments

To assess whether China has fulfilled its WTO commitments, the legal documents signed by China at the time of its WTO accession shall prevail, that is Protocol on the Accession to WTO of the People’s Republic of ChinaFootnote 1 (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Accession Protocol’) and Report of the Working Party on the Accession of ChinaFootnote 2 (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Working Party Report’). To fully fulfil its WTO commitments, China has undergone a comprehensive process of tremendous legal adjustments, substantive market opening up on goods and services, and relevant commitment implementation on intellectual property rights and transparency.

(i) Legal Adjustments

The WTO is an international economic organization based on rules. In order to achieve the consistency between the domestic trade law system and the WTO rules, China began to prepare for the adjustment of domestic laws since 1986 when it began the negotiation of ‘Returning to GATT’. By carrying out a large-scale review and revision of domestic laws and regulations after China joined the WTO in 2001, the Chinese central government has cleaned up more than 2,300 laws, regulations and departmental regulations, and the local governments have cleaned up more than 190,000 local policies and regulations (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2018). The relevant legal adjustments include: the general foreign trade law and legislative law, as well as specific laws and regulations concerning trade in goods and services, intellectual property and foreign investment.

(ii) Fulfilment of Commitments in Trade in Goods

1 Tariff and Non-tariff Barriers Cut

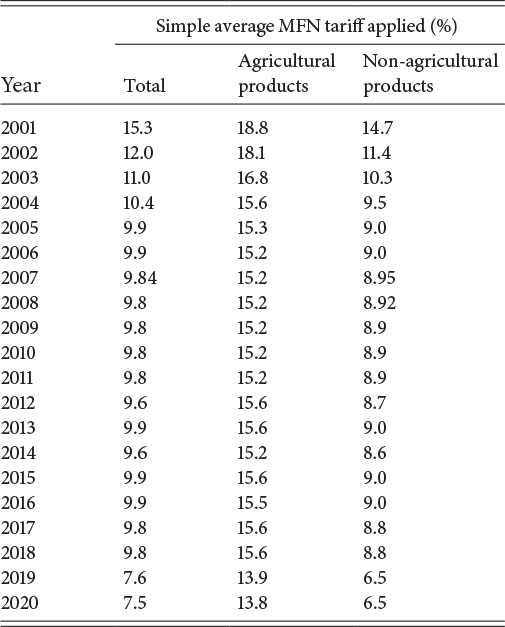

Annex 8 to the Accession ProtocolFootnote 3 is the tariff concession obligations for China. According to the Schedule of Concessions, China would reduce the total import tariff rate to 9.9 per cent within the transition period of six years after China’s accession to the WTO. So far, China has fully implemented its tariff commitments and reduced the total import tariff further to 7.5 per cent in 2020, as indicated in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Tariff rates of China 2001–2020

| Year | Simple average MFN tariff applied (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Agricultural products | Non-agricultural products | |

| 2001 | 15.3 | 18.8 | 14.7 |

| 2002 | 12.0 | 18.1 | 11.4 |

| 2003 | 11.0 | 16.8 | 10.3 |

| 2004 | 10.4 | 15.6 | 9.5 |

| 2005 | 9.9 | 15.3 | 9.0 |

| 2006 | 9.9 | 15.2 | 9.0 |

| 2007 | 9.84 | 15.2 | 8.95 |

| 2008 | 9.8 | 15.2 | 8.92 |

| 2009 | 9.8 | 15.2 | 8.9 |

| 2010 | 9.8 | 15.2 | 8.9 |

| 2011 | 9.8 | 15.2 | 8.9 |

| 2012 | 9.6 | 15.6 | 8.7 |

| 2013 | 9.9 | 15.6 | 9.0 |

| 2014 | 9.6 | 15.2 | 8.6 |

| 2015 | 9.9 | 15.6 | 9.0 |

| 2016 | 9.9 | 15.5 | 9.0 |

| 2017 | 9.8 | 15.6 | 8.8 |

| 2018 | 9.8 | 15.6 | 8.8 |

| 2019 | 7.6 | 13.9 | 6.5 |

| 2020 | 7.5 | 13.8 | 6.5 |

Besides, as of January 2005, China had eliminated all non-tariff measures such as import quota, import licence and specific bidding requirement, involving 424 dutiable products including automobile, mechanical and electrical products, natural rubber and so on. Instead of traditional non-tariff measures, tariff quotas were introduced on bulk commodities related to the national economy and the people’s livelihood such as wheat, corn, rice, sugar, cotton, wool, wool top and fertilizer. The Ministry of Commerce announces the quantity, the proportion of state-owned trade, the application condition and the distribution principle, etc., of the specific products subject to tariff quotas in the form of governmental proclamation annually, ensuring the transparency of tariff quota administration and the consistency with the WTO rules.

2 Right to Trade

Before China joined the WTO, the approval system for granting foreign trade rights restricted sufficient participation of enterprises in foreign trade. Since 1 July 2004, the original approval system changed to the registration system for granting foreign trade rights, and the scope of traders in China expanded to individuals. China has fully fulfilled its WTO commitment to liberalize the foreign trade rights and has been greatly releasing the foreign trade vitality of private enterprises. In 2020, there are 531,000 enterprises participating in foreign trade in China, with an increase of 6.2 per cent as compared with the previous year. Among them, the total trade volume of private enterprises reached 14.98 trillion CNY, accounting for 46.6 per cent of China’s total foreign trade. This shows the top position of private enterprises in China’s foreign trade. Besides, the total trade volume of foreign-invested enterprises reached 12.44 trillion CNY, accounting for 38.7 per cent of China’s total foreign trade (Xinhua Finance, 2021).

3 Subsidies

China has accepted certain specific subsidy commitments upon its WTO accession. For example, China committed that ‘subsidies provided to state-owned enterprises will be viewed as specific if, inter alia, state-owned enterprises are the predominant recipients of such subsidies or state-owned enterprises receive disproportionately large amounts of such subsidies’. Meanwhile, China has foregone some special and differential treatment under Articles 27.8, 27.9 and 27.13 of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM) that provide more subsidy space for developing countries.

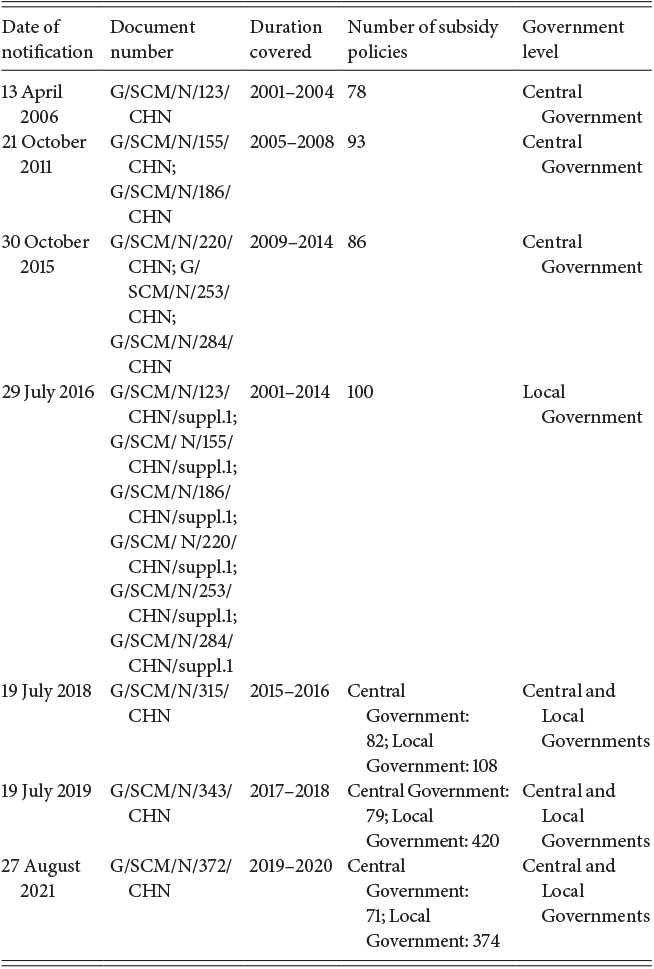

In addition, China has regularly notified to the WTO of its domestic subsidy policies in accordance with the notification requirements of the ASCM. As of 27 August 2021, China has notified its domestic subsidy policies seven times to the WTO, covering the period of 2001–2020, as is shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Notifications of subsidy policies by China to the WTO (October 2001–2021)

| Date of notification | Document number | Duration covered | Number of subsidy policies | Government level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 April 2006 | G/SCM/N/123/CHN | 2001–2004 | 78 | Central Government |

| 21 October 2011 | G/SCM/N/155/CHN; G/SCM/N/186/CHN | 2005–2008 | 93 | Central Government |

| 30 October 2015 | G/SCM/N/220/CHN; G/SCM/N/253/CHN; G/SCM/N/284/CHN | 2009–2014 | 86 | Central Government |

| 29 July 2016 | G/SCM/N/123/CHN/suppl.1; G/SCM/ N/155/CHN/suppl.1; G/SCM/N/186/CHN/suppl.1; G/SCM/ N/220/CHN/suppl.1; G/SCM/N/253/CHN/suppl.1; G/SCM/N/284/CHN/suppl.1 | 2001–2014 | 100 | Local Government |

| 19 July 2018 | G/SCM/N/315/CHN | 2015–2016 | Central Government: 82; Local Government: 108 | Central and Local Governments |

| 19 July 2019 | G/SCM/N/343/CHN | 2017–2018 | Central Government: 79; Local Government: 420 | Central and Local Governments |

| 27 August 2021 | G/SCM/N/372/CHN | 2019–2020 | Central Government: 71; Local Government: 374 | Central and Local Governments |

4 Agriculture

According to Article 12 of the Accession Protocol, China shall not maintain or introduce any export subsidies on agricultural products. Meanwhile, according to Section 235 of the Working Party Report, China would have recourse to a de minimis exemption for product-specific support equivalent to 8.5 per cent of the total value of a specific agricultural product and a de minimis exemption for non-specific product support equivalent to 8.5 per cent of the value of aggregate agricultural production in the relevant year. Such a de minimis level is lower than the 10 per cent allowed for developing members.

According to China Trade Policy Review Report released by the WTO Secretariat in June 2018,Footnote 4 China’s average MFN tariff rate for agricultural products in 2017 is 14.8 per cent, which is well below the average tariff rate of 56 per cent of developing members and 39 per cent of developed members. China’s average tariff rate for agricultural products has been reduced to 13.8 per cent in 2020. Besides, China submitted the latest notification of agricultural subsidies on 14 December 2018,Footnote 5 covering agricultural subsidies up to 2016. According to China’s notifications, the green box subsidies were 1.31 trillion CNY, and the blue box subsidies were 39.039 billion CNY. The above two categories of subsidies are not subject to WTO subsidy commitments. In addition, China notified amber box subsidies for specific agricultural products, that is corn, cotton, rapeseed, rice, root crops, soybean, wheat, cattle, pigs and sheep, and notified amber box subsidies for non-specific agricultural products (25.759 billion CNY). Except for terminated amber box subsidies for corn, cotton and soybean, other amber box subsidies for specific agricultural products and non-specific agricultural products did not exceed the de minimis exemption level of 8.5 per cent.

5 Trade Remedies

After its WTO accession, China amended and enacted the domestic trade remedy laws in order to make the domestic laws and regulations consistent with the WTO rules. Meanwhile, China has been reporting to the WTO of the amendment of trade remedy laws and the implementation of trade remedy measures in a timely manner.

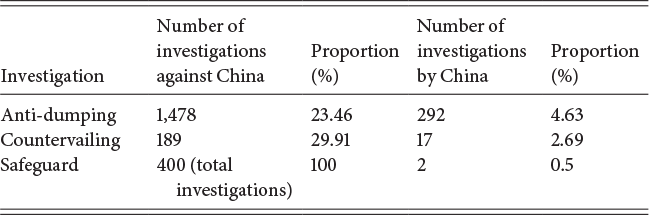

According to WTO statistics from 1995 to 2020, China was the top target country by foreign anti-dumping and countervailing investigations, but at the same time, China was very cautious to launch trade remedy investigations, accounting for a relatively low proportion of global trade remedy investigations, as is shown in Table 1.3. In addition, China has accepted certain China-specific rules on trade remedies, including: (i) a special textile safeguard mechanism (which expired on 11 December 2008)Footnote 6 and a transitional product-specific safeguard mechanism (which expired on 11 December 2013)Footnote 7; (ii) WTO members are authorized to apply the ‘surrogate country’ methodology in anti-dumping cases against China for a period of 15 years following China’s accession to the WTOFootnote 8 and (iii) WTO members are authorized to use ‘external benchmark’ to determine subsidies in countervailing duty cases against China.Footnote 9

Table 1.3 Number of trade remedy investigations involving China, 1995–2020

| Investigation | Number of investigations against China | Proportion (%) | Number of investigations by China | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-dumping | 1,478 | 23.46 | 292 | 4.63 |

| Countervailing | 189 | 29.91 | 17 | 2.69 |

| Safeguard | 400 (total investigations) | 100 | 2 | 0.5 |

6 Investment Measures

The WTO rules concerning investment measures are mainly embodied in two aspects: one is the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (hereinafter referred to as the TRIM Agreement) in relation to trade in goods, and the other is the General Agreement on Trade in Services in respect of trade in services.

According to Section 203 of the Working Party Report, China has to fully abide by the TRIM Agreement to cancel the foreign exchange balance requirements, trade balance requirements, local content requirements and export performance requirements. Furthermore, China has committed to provide national treatment to both foreign products and persons, while the normal WTO national treatment clauses only cover measures applicable to products.

In order to fulfil these commitments, China amended the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Foreign-capital Enterprises, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-Foreign Equity Joint Ventures and the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-Foreign Contractual Joint Ventures before China joined the WTO, eliminating the original investment requirements not conforming to its WTO commitments.

In addition to fulfilling its TRIM Agreement commitments, China also implemented the opening up policy for foreign investment on its own. On 3 September 2016, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress issued the ‘Decision on Amending the Four Laws Including the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Foreign-capital Enterprises’, stipulating that the original approval system for the establishment of foreign-capital enterprises, Chinese-Foreign Joint Ventures, Chinese-Foreign cooperative enterprises and Taiwan-invested enterprises shall be changed to the register administration when no special market access administrative measures are involved. On 28 June 2018, China issued the nationwide Special Administrative Measures (Negative List) for Foreign Investment Access (Edition 2018) for the first time, providing that all kinds of entities can enjoy access to Chinese market equally except for those sectors and businesses that are covered by the Negative List. On 1 January 2020, China enacted the new Foreign Investment Law that replaced the three previous laws, that is the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Foreign-capital Enterprises, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-Foreign Equity Joint Ventures and the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-Foreign Contractual Joint Ventures, aiming to provide clarity on foreign investment policies. The new Foreign Investment Law consolidated the legal status of pre-establishment national treatment and negative list for foreign direct investment (FDI), showing the determination of China to open up market to foreign investment.

China’s implementation of these commitments and further opening up on its own have created an open and fair competition environment for foreign investment in China. After joining the WTO, the FDI in China has increased from US$46.88 billion in 2001 to US$136.32 billion in 2017, with an annual growth rate of 6.9 per cent (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2018). Comparing a sharp drop in FDI globally, the FDI in China has rose to US$144.37 billion with an increase of 4.5 per cent in 2020. In the same year, the FDI in the service sector reached 776.77 billion CNY with an increase of 13.9 per cent, accounting for 77.7 per cent of total FDI in China. Meanwhile, the FDI in high-tech manufacturing sector increased by 11.4 per cent and FDI in high-tech service sector grew by 28.5 per cent (MOFCOM, 2021).

China’s improvement on investment environment has gained recognition from foreign enterprises. According to China Business Climate Survey Report 2021 published by American Chamber of Commerce in China, 61 per cent of the American enterprises surveyed list China as the primary investment destination and show confidence about China further opening its market. Eighty-three per cent of the American enterprises surveyed respond that they are not considering shifting business outside China (AmChamChina, 2021). The Business Confidence Survey 2021 published by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China points out ‘the resilience of China’s market provided much-needed shelter for European companies amidst the storm of the COVID-19 pandemic’. Sixty-eight per cent of European companies in China are optimistic about growth, and 60 per cent of European companies plan to expand their business in China in 2021 with nearly 10 per cent increase compared with that of 2020. Seventy-three per cent of European companies still report positive earnings, with another 14 per cent breaking even. A quarter of European manufacturers intend to further onshore some of their supply chains into China, with 4 per cent attempting to fully onshore (European Chamber, 2021).

(iii) Fulfilment of Commitments in Trade in Services

In accordance with Annex 9 to the Accession Protocol, China committed itself to opening up 100 sub-sectors in nine major sectors of trade in services by 2007. The number of sectors China committed to open was significantly above the average (54 sub-sectors) of developing countries and close to that (108 sub-sectors) of developed countries. Such a level of commitment was regarded as ‘the most radical services reform programme negotiated in the WTO’ (Mattoo, Reference Mattoo2003).

In terms of opening up service market, China has implemented a series of market opening measures in major service sectors including banking, insurance, securities, tourism, telecommunication, education, medical service and construction. By 2019, banks from fifty-five countries and regions have set up offices in China, and banks from all six continents have set up business establishments in China. The total assets of foreign banks in China reached 3.48 trillion CNY and their annual net profit reached 21.613 billion CNY (Xinhua Finance, 2020). By 2020, foreign insurance institutions have set up 66 foreign-funded insurance institutions, 117 representative offices and 17 professional insurance intermediaries in China, with total assets of 1.71 trillion CNY (China Economic Net, 2021). In addition, from 1 April 2020, the restriction on foreign ownership of securities companies has been lifted and the proportion of foreign ownership in securities companies can be up to 100 per cent.

(iv) Fulfilment of Commitments for Protection of Intellectual Property Rights

Intellectual property right (IPR) protection has always been one key issue for China, which is also the area where other countries have concerns about China. After China’s accession to the WTO, in order to fully fulfil its WTO commitments and keep the domestic IPR laws in line with the WTO rules, China has successively amended the Trademark Law, Patent Law and Copyright Law several times, and has promulgated the Regulations for the Protection of Layout design of Integrated Circuits and amended the Regulations for the Protection of Computer Software.

In terms of law enforcement, China has re-established the National Intellectual Property Administration and set up intellectual property courts and specialized adjudication institutions to enhance law enforcement and punishment for IPR cases, providing effective civil, administrative and criminal remedies for IPR holders. From 1998 to 2020, the National Intellectual Property Administration published the White Paper on China’s IPR Protection annually. China’s progress on IPR protection has been widely recognized by foreign communities. According to China Business Climate Survey Report 2020 published by American Chamber of Commerce in China, 69 per cent of American enterprises surveyed believe that China’s IPR protection has been improved. The Business Confidence Survey 2020 published by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China shows that 67 per cent of the European enterprises surveyed rate the effectiveness of China’s laws and regulations on IPR protection as ‘excellent’ or ‘adequate’.

(v) Transparency

Transparency is a basic principle of the WTO. China’s transparency obligations are mainly stipulated in Article 2(c) of the Accession Protocol and Sections 331 through 336 of the Working Party Report. After China’s accession to the WTO, it has completed the following tasks in fulfilling the transparency obligations: (1) Enhancing transparency in the Legislative Process. China has formulated, promulgated and implemented the Legislation Law of the People’s Republic of China, the Regulations on Procedures for the Formulation of Administrative Regulations and the Regulations on Procedures for the Formulation of Rules. These laws and regulations contain provisions on transparency and stipulate the uniform implementation of national laws and regulations. (2) Regularly issuing publications of trade-related laws and regulations. The official publications of China to promulgate trade-related laws, regulations and measures include the Gazette of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress,Footnote 10 the State Council Gazette,Footnote 11 the Catalogue of laws in force issued by the National People’s Congress,Footnote 12 China Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation Gazette,Footnote 13 the Proclamation of the People’s Bank of China,Footnote 14 the Proclamation of the Ministry of FinanceFootnote 15 and so on. In addition, China committed to translate all foreign trade laws into one of the WTO official languages, while the general transparency obligation in the WTO agreements only requires members to publish trade laws and regulations in their own national languages. (3) Designating national Enquiry Points. The Chinese government has established the ‘WTO Enquiry Point’Footnote 16 within the Ministry of Commerce to provide information for public queries related to the WTO. In addition, the Chinese government has established the ‘WTO/TBT-SPS Notification and Enquiry of China’ websiteFootnote 17 under the General Administration of Customs to publish technical trade measures and answer public inquiries. (4) Undergoing a special transitional review mechanism operated annually since China’s accession to the WTO, with the final review taking place in 2011 to examine the first 10 years of China’s WTO membership.

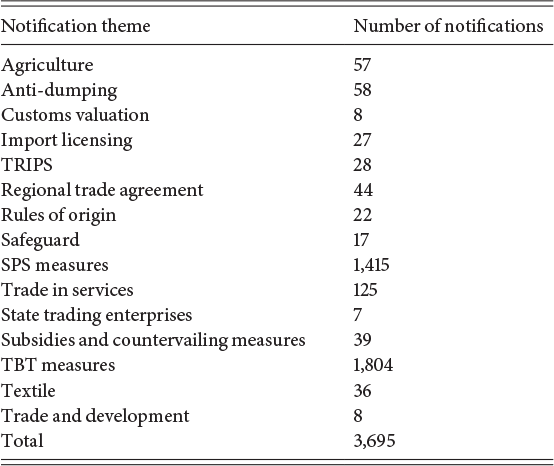

Besides the above transparency measures, China has been conscientiously fulfilling its notification obligations. As of 18 August 2021, China had submitted 3,695 notifications to the WTO, as detailed in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 China’s notifications to the WTO 2001–2021

| Notification theme | Number of notifications |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | 57 |

| Anti-dumping | 58 |

| Customs valuation | 8 |

| Import licensing | 27 |

| TRIPS | 28 |

| Regional trade agreement | 44 |

| Rules of origin | 22 |

| Safeguard | 17 |

| SPS measures | 1,415 |

| Trade in services | 125 |

| State trading enterprises | 7 |

| Subsidies and countervailing measures | 39 |

| TBT measures | 1,804 |

| Textile | 36 |

| Trade and development | 8 |

| Total | 3,695 |

II China’s Contribution to the World Economy and Trade

(i) China Acts as a Driving Force for the World Economy

Although China made significant concessions upon WTO accession, accepted certain tailor-made obligations and gave up some special and differential treatment for developing countries, China still has been honouring its WTO commitments, expanding market access, improving business environment and making positive contribution to world trade and economic development.

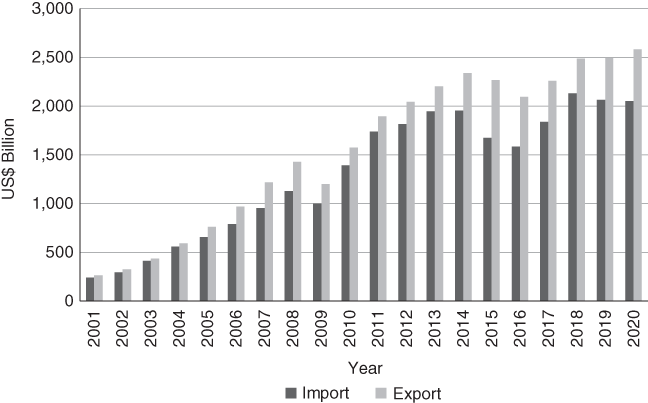

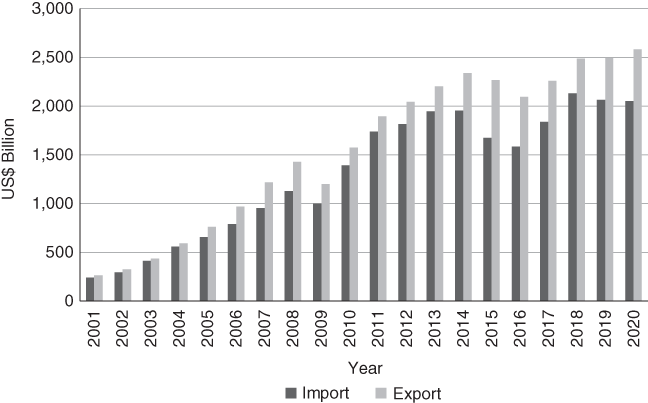

China’s implementation of WTO commitments and its broader opening up policy have accelerated its integration into the world economy and made it a critical part of global value chains. China is now the second largest economy in the world, with a dramatic increase of GDP from US$1.339 trillion in 2001 to US$14.723 trillion in 2020.Footnote 18 The GDP value of China represents 17.4 per cent of the world economy in 2020. Meanwhile, China has become the leading trading nation. From 2001 to 2020, China’s exports rose by nearly 8.74 times from US$266.1 billion to US$2,590.6 billion, while imports climbed by nearly 7.44 times from US$243.55 billion to US$2,055.59 billion (Figure 1.1). It presents a striking example of how opening an economy can boost productivity, the adaptation of modern technologies and international competitiveness.

Figure 1.1 China’s annual foreign trade, 2001–2020

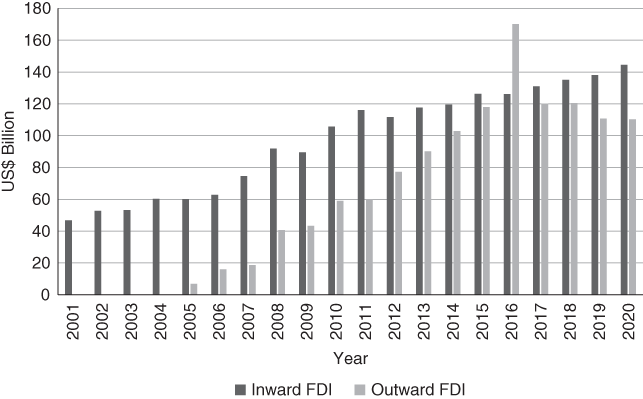

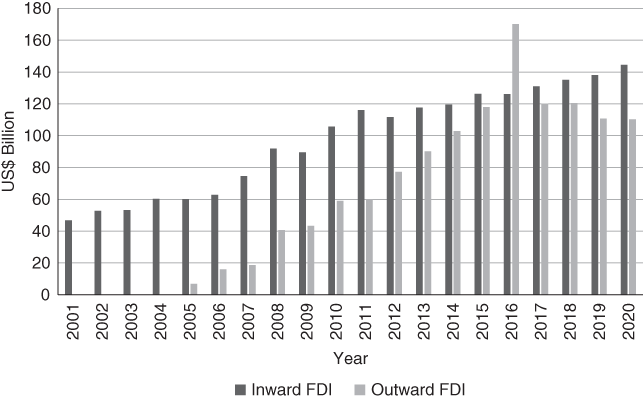

In addition, China’s integration into the world economy was marked by huge waves of FDI focusing on manufacturing for export and, increasingly, for its enormous and rapidly growing domestic market. The inflows of FDI to China totalled US$144.4 billion in 2020, representing an annual increase of 5.8 per cent since 2001.Footnote 19 Increasing numbers of foreign enterprises have established research and development centres, manufacturing factories and marketing branches in China, stimulating China’s trade from foreign-owned subsidiaries as well. Following the surge in inflows of FDI, China’s outward FDI has increased rapidly. In 2020, China’s outward FDI reached US$110.2 billion, with an annual increase of 18.91 per cent since 2005 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 China’s inward and outward FDI, 2001–2020

Note: The inflows of FDI data represent the actual use of FDI and does not include the FDI in banking, securities and insurance sectors. The outward FDI data can be traced back to 2005 and does not include the FDI in financial sector.

In return, China’s dramatic growth has been a critical driving force for the world economy. Despite the weakened world economy following the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese economy remains the single largest contributor to the world economic growth, contributing nearly 30 per cent of global growth on annual average. In the wake of current COVID-19 crisis worldwide, China became the only major economy in the world to achieve positive economic growth in 2020. According to the World Bank calculation, the world economy has declined by 3.593 per cent, with China’s economic rebound by 3.1 per cent.Footnote 20 Being the first to gain the momentum for recovery, China has made contributions to stabilizing the global supply chain and driving the world economy to recover.

China’s deeply embedded position in global value chains is broadly benefiting other countries. First, China has quickly gotten involved in the global supply chain and successfully upgraded from low-end industrial products that are resource-intensive and labour-intensive to more sophisticated industrial products that are capital-intensive and technology-intensive. As the world largest exporter, the share of high-technology manufactures in China’s exports has been growing from next to nothing in 1980 to 31 per cent in 2019.Footnote 21 Second, China is a major consumer market with the world’s largest middle-class consumers. As the fastest growing economy with strong demand for raw materials, advanced machinery and consumer products, China has become an even more important source of global demand, stimulating other economies’ growth. Third, China’s industrial upgrading and expanding trade will lead to further specialization and increased efficiency in world markets, and its increasingly educated labour force will become a force for global innovation, which have benefited developed and developing countries alike (The World Bank and Development Research Center of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China, 2013).

(ii) China Plays a Constructive Role in Multilateral Trading System

China’s significant rise has changed other countries’ perceptions of what is at stake in the global trading system. As China rises as a global power, it is naturally expected that China should play a larger role in global institutions (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2015). For decades, China has gradually translated its trade ascendancy into significant influences in the WTO.

As a firm supporter of the multilateral trading system, China’s contribution to the WTO is obvious to all. First of all, China’s WTO membership has contributed to making the WTO a relevant and truly global organization. Without China, with its 1.3 billion people and enormous market as a major trading nation, the WTO would be incomplete (Sun, Reference Sun, Meléndez-Ortiz, Bellmann and Cheng2011). On the one hand, China’s accession to the WTO set a good example for the WTO to encourage more developing countries to join. Following China’s accession, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and other developing countries became WTO members later on. On the other hand, China’s active participation in WTO negotiations and its strong support for the legitimate positions of the least developed countries (LDCs), African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, the African Group and other groupings of developing countries make the WTO more inclusive, representative and legitimate. Since China’s accession, the WTO membership has expanded from 143 to 164 members, with most of the ‘recently acceded members’ being developing countries. The participation of developing countries has led to the WTO leadership being more balanced (Li and Tu, Reference Li and Tu2018).

Second, China has taken an active part in key aspects of the WTO since its accession. Regarding the WTO negotiation function, China is an important contributor to the successful conclusion of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) and has voluntarily given up some preferential treatment of TFA for developing members. For example, China did not designate any Category C measures and agreed to implement 94.5 per cent of the measures immediately upon ratification. All of its Category B measures were fully implemented by January 2020.Footnote 22 China has been participating in all ‘Joint Statement Initiatives’ (JSIs) including negotiations on Investment Facilitation for Development, E-commerce, Services Domestic Regulation as well as Micro-, Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. China is also the driving member to promote the Informal Dialogue on Plastics Pollution and Environmentally Sustainable Plastics Trade.

Regarding the WTO judicial function, China has seriously implemented WTO dispute rulings. Since the establishment of the WTO in 1995, as of August 2021, WTO members have initiated 605 dispute cases in total, among which the USA and the EU are the most active members. The USA initiated 124 cases (20.5 per cent of the total) as complainant and was sued by 156 cases (25.8 per cent of the total) as respondent. The EU initiated 105 cases (17.4 per cent of the total) as complainant and was sued by 88 cases (14.5 per cent of the total) as respondent. China is at the third position, initiating twenty-two cases (3.6 per cent of the total) as complainant and being sued by forty-seven cases (7.8 per cent of the total).Footnote 23 If we only calculate the dispute cases since China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, as of August 2021, the number of disputes initiated by the USA and the EU was 55 and 49, and the number of disputes targeting the USA and the EU was 100 and 55, which are much higher than the number of cases initiated by or targeting China. Regarding the implementation of WTO dispute rulings, during 1995–2020, the WTO issued twenty-five arbitration decisions authorizing retaliation against non-compliant respondents in nineteen dispute cases according to Article 22.6 of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes. The relevant non-compliant respondents are the USA (18 arbitration decisions), the EU (5 arbitration decisions), Brazil (1 arbitration decision) and Canada (1 arbitration decision). China has never been targeted by any WTO arbitration decision authorizing retaliation, reflecting China’s good implementation record of WTO dispute rulings.

Third, China has taken an active part in various development assistance and aid for trade programmes of the WTO. For example, China and the WTO signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 2011 to establish the China’s LDCs and Accessions Programme. This programme is aimed at strengthening LDCs’ participation in the WTO and at assisting acceding governments in joining the WTO. In addition, China and African countries have jointly launched the Initiative on Partnership for Africa’s Development to provide technical and financial assistance to support Africa’s pursuit of prosperity and stability. Many developing countries have identified China as an important South-South development partner and source of financing.

III China’s Recent Efforts in Promoting WTO Joint Statement Initiatives

China has been active in promoting the WTO negotiating function through creative ways. One specific illustration is that China was a driving force behind the launch of JSI for Investment Facilitation for Development (Wolff, 2021) and mobilized wide support from WTO members.

Cross-border investment is an important driving force for economic growth. However, the existing international investment rules are dominated by bilateral and regional agreements, which are characterized by fragmentation and complexity. In recent years, the international communities have been working on promoting the formulation of multilateral investment rules. In September 2016, G20 leaders reached the Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking at the Hangzhou Summit.

Building on the outcome of the G20 Hangzhou Summit, China took the lead in introducing the topic of investment facilitation into the WTO in October 2016, creatively integrating the discussions on investment, trade and development together, as trade and investment are closely interlinked in today’s world underlined by in-depth development of global value chains. The initiative focused on developing a framework of rules to ensure transparency and predictability of investment measures; streamline and speed up administrative procedures and requirements; and enhance international cooperation, information sharing, the exchange of best practices, and relations with relevant stakeholders. Building on the positive momentum achieved by the WTO in concluding the TFA, the discussions on investment facilitation have broken the stalemate that the WTO has not been able to discuss investment issues for decades and taken an important step towards the goal of formulating multilateral investment rules in the WTO.

So far, China has made fruitful efforts as one of leading members to facilitate discussions on investment facilitation among WTO members. In April 2017, China coordinated Brazil, Argentina, Korea, Mexico and other developing members to form the ‘Friends of Investment Facilitation for Development (FIFD)’ to start informal dialogue on investment facilitation in the WTO. This was followed by seventy WTO members including China signing on to a Joint Ministerial Statement on Investment Facilitation for Development calling for ‘structured discussions with the aim of developing a multilateral framework on investment facilitation’ at the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires in December 2017. In 2018, the Structured Discussions focused on the identification of the possible elements of the framework on Investment Facilitation for Development, which were reflected in a ‘Checklist of Issues raised by Members’. On 5 November 2019, in the margin of Informal WTO Ministerial Meeting in Shanghai, China hosted a Ministerial Luncheon Meeting on Investment Facilitation for Development to facilitate discussions and exchanges of views. On the same day, ninety-two WTO members issued a new Joint Ministerial Statement on Investment Facilitation for Development. This Statement highlights the link between investment and development and to make sure that any eventual framework considers the needs of developing members and LDCs. As of December 2020, there were 105 WTO Members participating in the negotiation process, comprised of a mix of developed, developing and least developed members, and this number is expected to keep growing.

For China, it is particularly encouraging that many developing members, especially the LDCs, from differently geographic regions including Asia, Africa, Eurasia, Mid-east and Latin America have showed their support for ongoing discussions on investment facilitation. The broad participation of WTO members sends a clear message that the investment facilitation reflects the common interest of the broad WTO membership. It is promising to reach forward-looking and results-oriented outcomes that could reactivate the WTO negotiating function and increase relevance of the WTO in the world economic governance. The success of launching the Initiative on Investment Facilitation also inspires other members to follow suit. Some of the members launched the JSIs on E-commerce, Services Domestic Regulation as well as Micro-, Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises later on. All of these JSIs are making good progress, injecting momentum for WTO negotiations.

IV China’s Basic Stance towards the WTO Reform

China benefited enormously from entering the WTO and is now an important stakeholder in the existing multilateral trading system. China has been an active participant, staunch supporter and major contributor in the multilateral trading system. However, uncertainties in global trade governance are on the rise, and the WTO is facing multiple challenges. First, the world economy and trade need to pull out of the sluggish situation. The sudden outbreak of COVID-19 accelerated the decline of world trade that was already on the downward trend, and severely disrupted global supply chain, causing widespread negative impacts on the world economy. Second, the new trend of technological revolution has changed the shape and pattern of world economy. With the rise of information technology, digital trade and cross-border e-commerce, new challenges and problems in international trade are constantly emerging. The traditional WTO rules system cannot fully adapt to the new international economic and trade realities and needs to be improved. Third, the WTO has internal institutional problems from its three key dimensions. The Doha negotiation process is stalled, the trade policy review lacks effectiveness and the dispute settlement mechanism has been challenged by certain WTO members, making it difficult to effectively respond to emerging issues and coordinate interests among WTO members.

In the above context, the WTO reform is imperative. Since 2018, major WTO members have put forward a number of proposals on WTO reform. Although they share the same objectives of WTO reform, differences on substances remain. Discussions on WTO reform continue after the outbreak of COVID-19 but have to tackle with increased inward-looking trade policies of certain countries when dealing with the pandemic, which would negatively affect their political will to promote multilateral trade cooperation.

For China, the WTO reform will be a long-term process that will bring all-round influence to itself. On the one hand, participating in the process of WTO reform will be an important strategic practice for China to play a constructive role in the global economic governance under the current complex international situation. Maintaining a strong WTO-centred multilateral trading system is in line with China’s economic and trade interests and strategic needs. In turn, a successful WTO reform may provide a favourable external environment for China to stimulate domestic economic transformation, industrial upgrading and technological innovation and enhance China’s ability to participate in global economic governance. On the other hand, there is no escaping the fact that the focal issues in the current China–USA trade frictions are gradually evolving into issues that may affect the WTO reform. The demands for ‘market orientation’ and ‘structural reform’ put forward by a few developed members, such as the USA, EU and Japan, tried to change trade policy reform into debate of economic system and are clearly beyond the mandate of a trade organization such as the WTO. Such discussions would lead nowhere.

To support the stability and authority of the WTO-centred multilateral trading system, China issued two documents on WTO reform. The first document was issued in December 2018, setting out China’s basic principles and suggestions on WTO reform. The second document was formally submitted to the WTO to further elaborate the main concerns of China and specific actions that need to be taken for the WTO.Footnote 24 Generally speaking, China is open to any discussion that can strengthen the multilateral trading system and seeks cooperation with both developed and developing members. Since its WTO accession, China has made remarkable economic achievements, but it still faces the similar problems during economic development and shares broad common interests with other developing countries. In addition, the conclusion of Regional Economic Cooperation Partnership and China-EU Comprehensive Investment Agreement (CAI) shows China’s determination to further open up and achieve win–win outcome with both developed and developing members.

More specifically, China could promote WTO reform in the following aspects. First, regarding the crucial and urgent issues threatening the existence of the WTO, China proposed to break the impasse of the Appellate Body appointment, tighten disciplines to curb the abuse of national security exception and unilateral trade measures. China together with the EU and other WTO members submitted several proposals to the WTO to address the Appellate Body crisis,Footnote 25 and participated in a multi-party interim appeal arrangement (MPIA) to maintain an appeal process in the WTO dispute settlement mechanism. In addition, due to concerns on unilateral measures inconsistent with the WTO rules, China initiated three successive WTO disputes against the different rounds of USA unilateral tariff increases. Second, regarding the operational issues affecting the efficiency of the WTO, China shares common ground with other WTO members in strengthening the compliance of notification obligation and improving the efficiency of WTO subsidiary bodies. Third, regarding the emerging issues that reflect the twenty-first century business reality, China holds positive attitude towards open plurilateral approach to update the multilateral trade rules and believe that in new areas such as digital economy and artificial intelligence, the WTO members need to fill the gap between the reality and the WTO rule book, so as to bring new impetus for global economic growth and technological progress.

The last but more important, the new demand for global economic governance in the context of COVID-19 should be taken as a major opportunity to improve the WTO system, with China playing an critical role in it. On the one hand, as a leading trading nation, China became the largest exporter of COVID-19 critical medical products in 2020. It exported medical products with a value of US$105 billion, about 2.8 times its exports in 2019 (WTO, 2021). As of early September 2020, China has provided more than 200 countries and regions with more than 320 billion masks, 3.9 billion protective suits and 5.6 billion nucleic acid testing kits and provided more than 100 countries and international organizations with 1.2 billion doses of vaccines (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2021a, b). Furthermore, China has taken a series of trade facilitation measures to relieve logistic bottlenecks that have affected trade in medicines, equipment and essential supplies to fight against the pandemic, so as to prevent supply chain disruption and to facilitate the resuming of business operations. For example, China launched an emergency plan which simplified customs procedures, reduced port charges and accelerated inspections and quarantine procedures. The Chinese Customs managed to reduce the release time of relief cargo to 45 minutes and set up online services to guide importers throughout the fast clearance of anti-epidemic supplies. Import materials donated for epidemic prevention and control are exempted from import duties, import value-added tax and consumption tax. Sanitary registration for donated medical items has been suspended. The Chinese Customs can release directly selected medical items, such as vaccines, blood products and reagents, essential to prevent, diagnose or cure COVID-19, according to the certificate issued by competent authorities provided that the health risks can be controlled (UNCTAD, 2020). By utilizing its manufacturing capacities and trade facilitation measures, China did its part in closing global immunization gap especially in developing countries.

On the other hand, China plays an active role in multilateral agenda setting relevant to COVID-19. As of October 2021, China has submitted eleven proposals with other WTO members relevant to COVID-19.Footnote 26 Meanwhile, China has committed to making COVID-19 vaccines a global public good and promoting vaccine accessibility and affordability in developing countries. China supports discussions on TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines in the WTO and would like to facilitate such discussions to enter the text consultation stage. The above positive measures to facilitate anti-pandemic supplies, medical supplies and daily necessities would strengthen the fundamental role of the WTO in upholding trade liberalization during the pandemic and beyond.

V Concluding Remarks

China’s accession to the WTO in December 2001 has proven to be one of the most significant economic events both in our lifetime and in modern world history. In bringing China under its umbrella, the WTO took a huge step towards achieving its goal of universal membership and inclusiveness. As a result of China’s accession, one of the world’s biggest economies is now playing by the same multilaterally agreed rule book just as other major trading nations. This is no small achievement, particularly in terms of strengthening global trade governance and the multilateral trading system. China’s successful accession has also inspired many other developing countries to join the WTO.

Upon its WTO accession, China’s economy has undergone a systemic transformation and all-round opening up. The past 20 years have proven that by embracing globalization and integrating into world economy, China has successfully become a global manufacturing hub and trade centre. A wide range of Chinese industries, particularly those that were opened up due to China’s WTO commitment, have emerged much stronger in global competition and climbed up the value chain. Keeping the same path is therefore a strategic choice for China to enhance its international positioning and avoid falling into the ‘middle-income trap’ in the next decades.

The less known reason for China’s success in speedy development and industrial upgrading after its WTO accession is its proactive participation in global value chains. It is convinced that continuous trade and investment liberalization in the future will improve the business environment, attract foreign investment and help China remain firmly embedded in global value chains. It in turn will greatly reinforce its economic resilience to withstand various crises and risks and break the ill-founded ‘decoupling argument’.

At present, the multilateral trading system is going through the most difficult moment in its more than 70 years of history. Trade protectionism is spreading around the world. The WTO is in a deep crisis, with the vacuum of leadership, stalled multilateral negotiations and paralyzed dispute settlement mechanism. However, an open, non-discriminatory and rules-based multilateral trading system that can keep pace with modern times is indispensable for the growth of both China and the world economy. In a multipolar world, China should promote a new pattern of collective leadership and good co-governance in the WTO. Therefore, China is needed to provide more public goods to WTO members by opening its market and promote win–win multilateral cooperation. China is also expected to stay firm in observing multilateral trade rules so as to gain the trust of the members.

Regarding the ongoing WTO reform, China should actively participate in the process and firmly uphold open, inclusive and non-discriminatory principles, while preventing the multilateral trading system from moving towards protectionism.

In conclusion, while China’s huge achievements during 20 years of WTO membership are to be commended, the country must not rest on its successes. Our task now is to find a way to restore multilateral cooperation, keep strengthening the system and deliver new reforms. In an increasingly interdependent and multipolar world economy, it is our shared responsibility to ensure that we bolster global economic cooperation – and that we leave a strong and well-functioning trading system for the future generations.

Twenty years after it became a member of the WTO, China’s image in popular perception has shifted from the biggest success story of the world trading system to its biggest challenge.Footnote 1 In the past few years, tons of research have been conducted on what other WTO members should or could do to deal with the China challenge,Footnote 2 but not much attempt has been made to understand the Chinese perspective on its WTO membership. Focusing only on the China challenge without understanding the Chinese perspective is rather problematic as it treats China as a passive object rather than an active subject, despite its significant economic and political clouts in the world trading system today. This chapter fills the research gap by providing the first systemic review of this important yet ignored question, which in my view, would be the key to addressing the China challenge. The chapter argues that the Chinese perspective on the WTO has changed from viewing it as the symbol for its aspiration to integrate into the world economy, to trying to assimilate the Chinese economic system with that of the market-based multilateral trading system, to increasing alienations with the core values of WTO in response to the attacks on its economic system. The paper concludes with lessons drawing from China’s changing perspective, especially on how to manage the China challenge in the multilateral trading system.

I The Aspiration: Pre-2001

While China was a founding contracting party to the GATT, it did not participate in the activities of the GATT due to the withdrawal from the GATT by the government of the Republic of China in 1950 and the subsequent Cold War.Footnote 3 This did not change even when China resumed its seat in the United Nations in 1971 when the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Trade and Ministry of Foreign Affairs submitted a joint report advising against China’s participation in the GATT by calling it “a tool for the imperialists, especially American imperialists to expand foreign trade and grab world markets.”Footnote 4

However, China’s perspective started to change when it started its economic reform in the late 1970s. In particular, learning from the success stories of other export-oriented economies in East Asia, China tried to boost its trade and investment, and started to realize the key role played by the GATT in the facilitation of international trade. In a joint report submitted to the State Council in 1982,Footnote 5 the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade (MOFERT), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, State Economic Commission, Ministry of Finance, and General Customs Administration noted that China’s foreign trade is rapidly developing with the adoption of the reform and opening up policy, and trade with members of the GATT already constitute 80% of its overall trade.Footnote 6 Thus, they suggested China to participate in the GATT and enjoy the MFN tariffs.Footnote 7 After learning more about the GATT in the next few years, China formally submitted the application to resume its status as a GATT contracting party on July 10, 1986.Footnote 8

In its Memorandum on China’s Foreign Trade Regime submitted in February 1987, China stated that the “objective of the reform is to establish a new system of planned commodity economy of Chinese style.”Footnote 9 The strange term “planned commodity economy” is essentially just a euphemism for “market economy,” disguised in such a way so as to overcome the ideological opposition from Party hardliners. This was officially confirmed in 1992 when the Fourteenth National Congress of the Communist Party adopted a Resolution to make “socialist market economy” the goal of the reform,Footnote 10 which was subsequently incorporated into the PRC Constitution in 1993.Footnote 11

As China’s reform goal was to establish market economy and the GATT was the pinnacle international institution based on market economy principles, it is no wonder that China looked up to its accession to the GATT/WTO with great enthusiasm. For example, Li Zhongzhou, the first division chief for GATT Affairs at MOFERT who was responsible for China’s GATT bid for a long time in the 1980s, summarized nine benefits of China’s participation in the GATT, which includes boosting its trade and investment, getting MFN tariffs, enjoying special and differential treatment for developing countries, and participating in various GATT activities such as negotiations and dispute settlement.Footnote 12

China’s eagerness as an aspiring convert of the multilateral trading system is also demonstrated by its willingness to move past four major political crises during its accession process: the boycott against China in the aftermath of the “June Fourth incident” in 1989; the unilateral release of China’s concessions on market access and protocol (including some still under negotiation) by the US in April 1999; the NATO bombing of China’s embassy in Yugoslavia in May 1999; and the collision of a US Navy spy plane with a Chinese fighter jet in April 2001. Any of the four crises, if they were to happen today, could easily derail or even terminate the whole negotiation. Yet, China was willing to set them aside and press forward with its accession talk. Indeed, in each case, a deliberate decision was made by China’s then top leader to de-escalate the situation and move on, such as Deng Xiaoping’s speech affirming the goal of “market economy” in his southern tour in 1992, Jiang Zemin’s decision to resume negotiation with the US in August 1999,Footnote 13 and his call to President Bush at 2 AM Beijing Time on 12 September 2001, just 5 hours after the first of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, to condemn the attacks and send condolences to American people.Footnote 14

II The Assimilation: 2001–2008

With the same joy as Monk Tang entering the Western Heaven,Footnote 15 China finally acceded to the WTO at the Doha Ministerial Conference in November 2001. The accession was celebrated universally across China, with CCTV hosting a “Who Wants to be a Millionaire”-style show testing people’s knowledge on WTO issues, various local campaigns to teach WTO to people from all trades including taxi drivers, and a high-level seminar on WTO issues for Provincial Governors and Ministers in February 2002 with an opening speech by President Jiang Zemin. In the speech, Jiang repeatedly emphasized how the accession could help China to act in accordance with internationally accepted rules, build a foreign trade legal system compatible with common international practices, and use WTO rules to “constrain China’s policy and govern the government.”Footnote 16

Of course, China’s decision to embrace WTO rules was in no way made out of altruism or naiveté. Indeed, Jiang made it quite clear that the US’ willingness to let China in was not “a sudden act of kindness.”Footnote 17 Instead, Jiang highlighted the strategic considerations of the US, that is, “pushing for political liberalization through economic liberalization” and thus “Westernize and divide the Socialist countries.”Footnote 18 Referring to Clinton’s speech on China’s PNTR status, which hailed the role of WTO accession in “removing government from vast areas of people’s lives”Footnote 19 and promoting social and political reform in China, Jiang stressed the need for China to keep a clear mind and strive to achieve its own “strategic intentions.”Footnote 20

So what are China’s “strategic intentions”? The first is the promotion of China’s economic development. Jiang mentioned that he thought “long and hard” about China’s accession to the WTO and decided that China must “swim in the sea of international markets” given the increasing competition at the international level.Footnote 21 According to him, WTO accession will help China to attract foreign investment, enhance the competitiveness of its industries, participate in international rule-making, and promote the development of the socialist market economy, which are all aligned with China’s long-term development goals.Footnote 22 The second is to improve China’s approach to running its economy. In his speech, Jiang called for a major overhaul of the Chinese government’s way to manage the economy upon WTO accession. In particular, he stated that the primary task of the government in managing the economy shall be regulating the market economy order using WTO rules, guiding the proper development of a socialist market economy, and nurturing and strengthening the international competitiveness of the Chinese economy.Footnote 23 In other words, China essentially takes the WTO rules as a manual for economic reform, which is why Jiang repeatedly mentioned the need for government officials and Party members to “study WTO rules … in this new exam,” and ended his speech by calling all government leaders to “pass the exam, and strive to get good results.”Footnote 24

How did China fare on the exam? The main question on the exam is the implementation of its accession commitments, which China passed with flying colors. For example, in China’s first transitional review conducted in 2002, Sergio Marchi, then chairman of the WTO General Council, gave China an A+.Footnote 25 Similarly, Pascal Lamy also gave China an A+ in 2011.Footnote 26

In addition, China also performed well on the bonus question on learning the rules of the WTO and fully participated in all areas of WTO’s work.Footnote 27 In WTO negotiations, China has emerged from a Member that struggled to fully understand the content of discussionFootnote 28 to a key player.Footnote 29 In WTO dispute settlement, China has also risen from a reluctant participant that tried very hard to avoid disputes to one of the most active litigants.

It is worth noting that China’s assimilation efforts in the WTO are largely because China deemed it to be in its own benefits. As explained by Shi Guangsheng, China’s trade minister at the time of the accession, WTO membership is beneficial to China in three ways:Footnote 30 First, it promoted China’s own economic development, as shown by China’s accelerating GDP growth rate from 2001 to 2007, reversing the trend of declining GDP growth pre-2001; Second, it promoted China’s reform and opening up, as shown by China’s exponential growth in both exports and FDI; Third, it promoted the development of the socialist market economy in China, as shown by China’s improving score in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index.Footnote 31

III The Awakening: 2008–2012

Right before China’s first WTO Ambassador Sun Zhenyu went to Geneva to assume his position in early 2002, he met with former USTR Charlene Barshefsky in Beijing.Footnote 32 Barshefsky told Sun that China’s accession will change the balance of power in the WTO, but it would be better for China to observe how things were done in the WTO first before joining any group. Taking her advice, China adopted a cautious approach in its first few years in the WTO: while it claimed its position as a developing country for political reasons, its positions on various issues do not always follow the developing country’s “party-line.” For example, China participated actively in the trade facilitation negotiation even though many developing countries opposed the negotiation. China was also the first developing country to express support for the chairman’s texts in agriculture and NAMA negotiations.Footnote 33 In the words of Zhang Xiangchen, then Director-General of the Division on WTO Affairs of MOFCOM and later China’s WTO Ambassador, China should play “a balancing, bridging and constructive role” between developed and developing countries.Footnote 34 This is confirmed by Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, who stated at the Forum on the 10th Anniversary of China’s Accession to the WTO that China was “a responsible country that has actively shouldered international responsibilities commensurate with the level of its development.”Footnote 35

While it recognizes that it has special responsibilities as a large developing country, China resents being singled out in the negotiations due to the painful memory of its “century of humiliation” starting from the Opium War. Therefore, when the July 2008 meeting ran into an impasse due to India’s refusal to give in on special products and special safeguard mechanisms, China rejected the US request for it to provide additional concessions on special products in agriculture and sectoral negotiations on industrial goods as the same demands were not made to India or Brazil. When the US tried to accuse China of walking back the text despite getting “a seat at the big kids’ table” as it requested,Footnote 36 Ambassador Sun gave a diatribe outlining China’s contributions to the round in various areas as a retort to the US “finger pointing.”Footnote 37

As the July min-ministerial was underway in Geneva, an editorial titled “Elephant in the Room”Footnote 38 was published by the China WTO Tribune – a journal published by MOFCOM and edited by Zhang Xiangchen, who assumed his new position as the Deputy Permanent Representative of China’s WTO mission the month before. In the editorial, Zhang argued that China’s low-profile approach did not prevent it from playing a major role in the WTO. Moreover, as the world plunged into the financial crisis in 2008, China’s visibility would become even more prominent. In 2009, despite the contraction of world trade by 13%, China became the biggest exporter for the first time in modern history, which led to two major developments:

First, the fact that China emerged not only unscathed but also triumphant from the financial crisis bolstered China’s confidence in the so-called Beijing Model, a model of economic growth that relies heavily on government intervention.Footnote 39 Moreover, as China was able to avoid the contagious effects of the global crisis by maintaining its restrictions on foreign exchange and capital flows, its incomplete market reform was hailed as a feature rather than a defect of the Chinese system and Chinese leaders started to question the wisdom of more market-oriented reforms. On the other hand, concerned with the continued rise of China, the US announced its “pivot to Asia” and launched negotiations to join the TPP to reinforce both economic ties and strategic relationships in the Asia Pacific.Footnote 40

Second, China’s emergence as the largest exporter, combined with the growth contractions in many countries, resulted in new waves of export restrictions against China even though the textile safeguard mechanism and the product-specific safeguard mechanism in China’s Accession Protocol started to expire. With its surge of exports, China tried to ensure the supply of raw materials for its domestic producers by enacting export restrictions on raw materials. Based on its understanding of WTO rules, China regarded such measures to be justified by the general exceptions clause under GATT Art. XX.Footnote 41 However, the US and EU sued China in the WTO, and managed to win the case by arguing that China could not invoke the general exceptions clause due to the lack of explicit reference to such provision in China’s Accession Protocol. At the DSB meeting adopting the AB report, China criticized the report for creating “a two tier membership, which was neither legally sustainable, nor systemically desirable.”Footnote 42 Li Zhongzhou was even more explicit in his op-ed in the China WTO Tribune, where he blasted the decision as downgrading China to a “second-class citizen.”Footnote 43 In view of such double standards, China started to question the value of WTO rules, which led to its efforts seeking alternatives.

IV The Alternative: 2013–2015

With the US reaching across the Pacific to assemble its allies in the TPP to contain China and “make sure the United States – and not countries like China – is the one writing this century’s rules for the world’s economy,”Footnote 44 China also started to make its own move. The first piece of the strategy is to form an RTA in response to the TPP, which led to the launch of negotiations on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2012.Footnote 45 China had long advocated for regional economic integration between East and Southeast Asia, but its preferred set-up was ASEAN plus three, that is, China, Japan, and Korea. Japan, on the other hand, prefers to add three more countries, that is, India, Australia, and New Zealand, as counterbalances to China. China’s willingness to go with the ASEAN plus six model reveals its urgency following the US accession to the TPP, which could severely disrupt China’s supply chains in the region with provisions such as the yarn-forwarding rule that makes it difficult for TPP members to use inputs from non-members in the production process.

Second, in 2013, China announced two major initiatives: the Silk Road Economic Belt, which connects China with Europe through the Eurasian Continent,Footnote 46 and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which links China with Southeast Asian countries, Africa, and Europe across the Pacific and Indian oceans.Footnote 47 Later combined together as the Belt and Road Initiative, this has since become the centerpiece of President Xi’s foreign policy. Spanning sixty-five countries on three continents with a total population of 4.4 billion,Footnote 48 the BRI reportedly accounts for 29% of global GDP and 23.4% of global merchandise and services exports.Footnote 49 By “linking up the interests of China with those of developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America,”Footnote 50 the BRI helps China to build its own supply chain without direct confrontation with the US in the Pacific.

V The Attack: 2016–2020

China’s efforts to build the alternatives turned out to be rather prescient, as attacks started to pour in from all fronts in the next few years.

(i) Unilateral Attack

On the unilateral front, the US launched a trade war against China when Trump came into office. In August 2017, President Trump requested the USTR, to ‘determine, consistent with Section 302(b) of the Trade Act of 1974 (19 U.S.C. 2412(b)), whether to investigate any of China’s laws, policies, practices, or actions that may be unreasonable or discriminatory and that may be harming American intellectual property rights, innovation, or technology development.’Footnote 51 On 22 March 2018, the USTR released its Section 301 Report into China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation, which suggested ‘[a] range of tools may be appropriate to address these serious matters including more intensive bilateral engagement, WTO dispute settlement, and/or additional Section 301 investigations.’Footnote 52 On the same day, President Trump directed the USTR to raise tariffs against Chinese products, bring WTO cases against China’s discriminatory licensing practices, and the Treasury Department to impose investment restrictions on Chinese firms.Footnote 53 On 3 April 2018, the USTR published a proposed list of Chinese products subject to an additional tariff of 25%.Footnote 54 In total, the list covers about 1,300 separate tariff lines with an estimated worth of roughly $50 billion. In the next one and a half years, the list was expanded several times to cover $550 billion worth of Chinese products.

These tariff measures are clearly in violation of WTO rules such as MFN and tariff bindings. In addition, despite its ultimate finding of consistency on the Section 301 legislation in the US – Sections 301 case, the WTO Panel also explicitly warned that making a unilateral determination of WTO-inconsistency against another country’s trade measures “before the adoption of DSB findings” could constitute “a prima facie violation of Article 23.2(a) [of the DSU]” (emphases original).Footnote 55 Commenting on the US Section 301 investigations in the General Council, China’s WTO Ambassador Zhang Xiangchen criticized the US measures for “violat[ing] the most fundamental values and principles of this organization.” China filed a dispute against the US the day after the first rounds of tariffs were announced,Footnote 56 and brought two successive WTO cases against subsequent rounds of US tariffs.Footnote 57

(ii) Plurilateral Attack

In addition to unilateral actions, the US also started to take a coordinated approach against China with its allies. This started with a joint statement the US issued along with the EU and Japan at the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in December 2017,Footnote 58 where they agreed to “enhance trilateral cooperation in the WTO and in other forums” to address the “critical concerns” on “severe excess capacity in key sectors exacerbated by government-financed and supported capacity expansion, unfair competitive conditions caused by large market-distorting subsidies and state-owned enterprises, forced technology transfer, and local content requirements and preferences.” Since then, the trilateral group has intensified its work with several more joint statements, all targeting China’s trade practices without explicitly naming it.

In China’s view, the other major attack on the plurilateral front is the refusal to recognize China’s market economy status. According to Section 15(a)(ii) of China’s WTO Accession Protocol, China agreed to be treated as a non-market economy (NME) in antidumping investigations, with the proviso that such provision “shall expire 15 years after the date of accession.” China understood this to mean that “China will be recognized as a full market economy” on 11 December 2016, as stated by then-Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao to world leaders in 2011.Footnote 59 Since its accession, China has been working hard to persuade other WTO members to recognize China’s market economy status, both by inserting the provision in its free trade agreements, as well as making direct demands to the governments of other members. As of 2016, more than 80 countries have recognized China’s market economy status. In addition to the practical benefit of avoiding discriminatory treatments in the antidumping investigation, the recognition of market economy status is also regarded by China to be of great symbolic value as it marks China’s coming of age in the WTO. However, starting from 2011, some foreign lawyers started to argue that the expiration of the clause does not automatically grant China market economy status.Footnote 60 In 2016, the EUFootnote 61 and the USFootnote 62 respectively announced that they would not recognize China’s market economy status.Footnote 63 In response, China dropped its earlier position which mixed the two issues together and started to separate them by treating market economy status as a political issue and NME methodology as a legal/technical issue. On 11 December 2016, China took the unprecedented move by suing both the EU and the US in the WTO.Footnote 64

At the first panel hearing of the case against the EU in December 2017, Chinese WTO Ambassador Zhang Xiangchen made a rare appearance before the panel.Footnote 65 Quoting the Latin maxim “pacta sunt servanda” (“agreements must be kept”), Zhang made clear at the outset that “China brought this matter to dispute settlement with the objective to establish that promises made must be respected, and treaty terms struck must be honoured.”Footnote 66 In China’s 14-page statement, Zhang referred to the word “promise” six times and lambasted the US and EU for breaking their promises on ending China’s NME status after 15 years. Zhang also highlighted the high stakes at play, including “the credibility of the dispute settlement mechanism, the integrity of the World Trade Organization, and the membership’s faith in the multilateral trading system.”Footnote 67

In the end, however, the panel did not side with China. According to a leaked interim report, the panel supported the EU’s argument that the expiration of the clause merely shifted the burden of proof and did not terminate the substantive right to apply the NME methodology.Footnote 68 In June 2019, China decided to suspend the caseFootnote 69 and then abandoned the case by letting the authority for the panel lapse in June 2020.Footnote 70 While MOFCOM later clarified by stating that the termination of the proceedings in the case does not affect China’s rights under the WTO,Footnote 71 it did indirectly reflect China’s disappointment and despair toward the decision of the panel.

(iii) Multilateral Attack

At the multilateral level, the trilateral initiative spurred a new wave of WTO reform proposals, with key players, led by the US, EU, and Canada, all submitting major proposals. While there are considerable variations among these proposals, they mainly focus on three groups of issues, all of which are regarded by China as China-specific:

The first group addresses the need to update the substantive rules of the WTO, such as clarifying the application of the “public body” rule to SOEs, expanding the rules on forced technology transfer, and reducing barriers to digital trade.Footnote 72 All of these reflect long-standing concerns over China’s trade and economic systems, which have been litigated in the WTO. For example, concerns over China’s unique state-led development model that emphasizes the role of state-owned firms in the Chinese economy were litigated in the US – Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties (China).Footnote 73 Similarly, cases were also brought over China’s over-zealous drive to obtain and absorb foreign intellectual property rights, where foreign firms are allegedly asked to trade their technologies for markets.Footnote 74 China’s censorship regime and its tight control over information and the Internet were also the subjects of both actual and potential WTO litigation.Footnote 75 Unhappy with the results of these cases, the West tries to make new rules and tighten the discipline through their reform proposals.

The second group addresses the procedural issue of boosting the efficiency and effectiveness of the WTO’s monitoring function, especially the rules relating to compliance with the WTO’s notification requirements, such as those under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures.Footnote 76 While no WTO Member may claim a perfect record in subsidy notifications, China’s compliance seems to be particularly problematic and has been a constant subject of complaint by the USTR ever since China’s accession to the WTO.Footnote 77 After much prodding from the US, China finally submitted its first subsidies notification in April 2006, nearly five years behind schedule.Footnote 78 However, even that remained incomplete as China did not notify subsidies by subcentral governments, which would eventually take China another ten years to report, with the subsequent notification took another four years.Footnote 79 In frustration, the US filed a “counter notification” in October 2011 pursuant to Article 25.10 of the SCM Agreement, and identified more than 200 unreported subsidy measures.Footnote 80 To address the problem, the joint proposal by the United States, the European Union, Japan and Canada on strengthening the notification requirements suggested some rather drastic measures, such as naming and shaming the non-compliant Member by designating it as “a Member with notification delay,” curtailing its right to intervene in WTO meetings and nominate chairs to WTO bodies, and even levying a 5% fine based on its annual WTO contribution.Footnote 81

The last significant issue is development, another long-standing issue stemming from the call of the US and the EU for greater “differentiation” among WTO members. While they are willing to extend special and differential treatment (S&DT) to smaller developing countries, it is politically difficult for them to extend the same treatment to large developing countries, such as China, a growing economic powerhouse. Among the major economies, the US never granted China preferences under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), while Canada and the EU terminated GSP benefits for China in 2014 and 2015 respectively. At the time of writing, only Australia, New Zealand, and Norway continue to provide GSP preferences to China. The EU and Canada, in their proposals, called for the rejection of “blanket flexibilities”Footnote 82 for all WTO members, which are to be replaced by “a needs-driven and evidence-based approach”Footnote 83 that “recognizes the need for flexibility for development purposes while acknowledging that not all countries need or should benefit from the same level of flexibility.”Footnote 84 The US proposal went even further by proposing the automatic termination of S&DT for members who meet one of the following criteria: OECD membership, G20 membership, classification as “high income” by the World Bank, or a share of global goods trade at 0.5% or above.Footnote 85 With such a classification system, many WTO members, including China, will be stripped of their developing countries’ status.

Commenting on these reform proposals at the Luncheon in Paris Workshop in November 2018, Ambassador Zhang criticized these efforts as trying to “put China in a tailor-made straightjacket of trade rules to constrain China’s development…in the name of reform.”Footnote 86 Drawing an analogy from the attempts by some countries to change the rules of the International Table Tennis Federation to reduce China’s “advantages,” Zhang pointed out that “[w]inning a game should be done through strengthen and hard work, not by altering the rules.”

Another multilateral attack is the persistent blockage of the launch of the selection process for AB members by the US, which effectively shuts down the institution in December 2020. While such an attack ostensibly had nothing to do with China, a close examination of the US criticisms against the AB reveals that many of the complaints relate to the China cases. For example, among the six substantive “interpretive errors” enumerated by the USTR in its Report on the AB,Footnote 87 three are directed against the AB’s decisions in cases concerning China.Footnote 88 These include, for example, the “public body” jurisprudence developed in US – Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties (China),Footnote 89 the requirement to consider government prices before using out-of-country benchmarks in US – Countervailing Measures (China) (21.5),Footnote 90 and the ban on “double remedies” through the concurrent application of countervailing duties and antidumping duties in US – Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties (China).Footnote 91 Thus, it is no wonder that China also regarded the attack on the AB as an indirect attack on China.

VI The Aftermath: Affirmation and Alienation