Introduction

States are increasingly concerned about the security of submarine cables.Footnote 1 After several suspicious incidents of submarine cable damage off Taiwan’s coast, in June 2025 the Chinese captain of the Togolese-registered vessel Hong Tai 58 was convicted of damaging Taiwan’s submarine cable networks with an anchor and sentenced to prison.Footnote 2 This incident followed two widely reported acts of alleged cable sabotage in the Baltic Sea in late 2024.Footnote 3 As the conduit for approximately 99 per cent of digital communications globally, submarine cables are the backbone of the internet and modern digital societies. In the ‘Indo-Pacific’ region – now generally regarded as a ‘theatre of strategic competition’ between the United States (US) and ChinaFootnote 4 – many states rely upon a limited number of expensive cables that are laid on or buried under the seabed for data connectivity with the rest of the world. Submarine cable networks are routinely damaged by accidental and negligent commercial and recreational maritime activity (such as fishing and anchoring), as well as by natural phenomena including underwater landslides and underwater volcanic activity.Footnote 5 However, in an era of heightened geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific, concerns over deliberate attacks are prominent. These could have the considerable effect of creating widespread social and economic disruption for one or more states, with the ‘digital economy’ particularly exposed.Footnote 6 Data integrity and concerns about signals intelligence collection also drive concerns over submarine cable network control.

Submarine cable security highlights the ways in which the traditional separation between economic and national security is becoming increasingly blurred, with economic factors significantly impacting national security challenges and vice versa – what Lee, Wainwright and Glassman,Footnote 7 Schindler, DiCarlo, and Paudel,Footnote 8 and others term ‘geopolitical-economic competition’. In the cable network industry, security and economics are intertwined as a complex mix of state and private actors are involved in funding, developing, and maintaining submarine cables. Suppliers, owners, and operators of undersea cable networks may be private or national telecommunication providers and often invest as a consortium, particularly given the expense in laying and protecting submarine cables.Footnote 9 Companies may also be backed by states. While the strategic importance of security and resilience of underseas cables is not new, since 2015 concerns have intensified as Chinese companies (broadly under China’s Digital Silk Road, part of its Belt and Road Initiative) became increasingly prominent in building and supplying submarine cable infrastructure. Other governments have increasingly recognised the importance of protecting data and communication channels for the functioning of respective societies and national security.Footnote 10

There is much attention being paid in the ‘grey’ literature to the (in)security of seabed cables in the context of geopolitical-economic competition, and the academic literature has also grown in recent years.Footnote 11 The international governance and security of undersea cables is complicated by their location in maritime spaces that reach typically beyond the unilateral control of sovereign states and involve commercial partners that (unlike states) may have priorities other than security. While the role of private corporations in submarine cables may limit ‘what is politically possible’,Footnote 12 this paper argues that to deal with emerging perceived seabed insecurity, states have nevertheless sought to adopt interventionist approaches to cable network development in collaboration with partners. By encouraging neighbours to shift trade and supply chain networks to countries (and respective firms) that share political values, the US and its partners are engaging in economic policies of ‘friendshoring’. In the context of strategic competition, recent subsea cable network deals and developments present illuminating case studies in how states have sought to manage economic projects and international relations to defend their security interests.

In the Indo-Pacific, efforts to ‘friendshore’ the seabed – that is, integrating friends into data supply chains while simultaneously excluding foes in a form of collective yet exclusionary control – are demonstrated through a raft of recent deals by the US and partners. These new submarine cable network arrangements are an attempt to constrain the abilities of China to gain market share and regional influence via data supply chain centrality. Since 2021, the US Department of State has implemented its ‘CABLES Program’ throughout the Indo-Pacific, which it views as ‘responsibly informing essential telecommunications and cables infrastructure stakeholders of the perils of choosing untrusted suppliers’. In 2024, the US’s International Cyberspace and Digital Policy Strategy linked economic choices with strategic interests, arguing that ‘choices made about which vendors to rely on for undersea cable infrastructure, maintenance, and repair operations can either drive development and innovation or lead to new forms of dependency and insecurity’.Footnote 13 In order to hamstring Chinese bids, the US also created an interagency task force – at one point dubbed ‘Team Telecom’ – to advise the Federal Communications Commission ‘on national security and law enforcement concerns associated with applications for telecommunications licenses meeting certain thresholds of foreign ownership or control’.Footnote 14 The US government and its allies have also sought to intervene in private undersea cable deals to ensure that Chinese companies would be prevented from winning tenders.Footnote 15

Our paper argues that ‘friendshoring’ reflects a broader pursuit for ‘network centrality’ through a collective yet exclusionary control over submarine cable networks.Footnote 16 Actors seek network centrality by controlling the circulation of information and production networks, including by excluding competitors from those networks.Footnote 17 To make this argument, this article begins by contextualising the ‘geopolitical-economic competition’ that frames the analysis of how states are engaging in the development of submarine cables. The article uses three recent case studies to demonstrate how states are pursuing network centrality through critical infrastructure: the Coral Sea Cable System, the East Micronesia Cable System, and the Palau Spur Cable. These cases were selected to illuminate how the US and its Indo-Pacific partners (primarily Japan and Australia) scrambled to respond to China’s forays into the global submarine cable network market commencing in the late 2010s through the exclusionary development of cable networks premised on collective control by a small number of actors. These cases focus particularly on the Pacific because this region has become an important site of geopolitical-economic competition between the US and China. Perceptions of China’s increased presence and influence in the Pacific resulted in swift new policies and led to the establishment of new bureaucratic infrastructures to proactively intervene in new submarine cable network projects before China could participate.

The paper concludes by offering some potential implications of seabed friendshoring for regional states. US President Donald Trump’s second inauguration in January 2025 has cast doubt over the future of friendshoring, particularly as its prominence in US discourses has reduced. This should prompt other countries to consider how collective solutions to shared security risks can be found and implemented in an era of ‘America First’. While the future of friendshoring (with US involvement) is uncertain, its role in submarine cable development nevertheless confirms a new model of geopolitical-economic competition based on network centrality that is reshaping global data flows.

Geopolitical-economic competition, ‘network centrality’, and the role of friendshoring

Over the past decade, analysts have debated the nature of the relationship between the US and China and its implications for global order.Footnote 18 Some argue that the relationship should be characterised as a ‘new Cold War’. Similarities between the old and new Cold Wars lie primarily in the increasing bifurcation in economic and security relations reflected in ‘growing bipolarity, intensifying polemics, sharpening distinctions between autocracies and democracies’.Footnote 19 While there are important differences (e.g., the presence and importance of non-aligned ‘connector’ countries differs from the early period of the Cold War), there is some evidence of ‘decoupling’ (separating economic systems) along geopolitical lines evident in trade and investment fragmentation, with Mexico overtaking China in 2023 to become the US’s largest trading partner. The purpose of the first Trump administration’s trade war in ‘pulling up the drawbridges’, for example, was to undo ‘40 years of ever closer economic relations with China and rolling back U.S. reliance on Chinese factories, firms, and investment’.Footnote 20 This was a repudiation of earlier ideas, particularly in the 1990s, that economic engagement with China would contribute to it becoming a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in global politics and/or lead to democratisation.Footnote 21

Instead, the geopolitical-economic competition of the new Cold War is creating global economic blocs, which emerge when great powers enter a ‘race’ for economic privilege by developing or expanding their own ‘exclusive economic zones’.Footnote 22 This is a dynamic that scholar David Lake likens to the security dilemma:Footnote 23

historically, great power competition has been driven primarily by exclusion or fears of exclusion from each power’s international economic zone, including its domestic market. Great powers in the past have often used their international influence to build zones in which subordinate polities – whether these be colonies or simply states within a sphere of influence – are integrated into their economies.Footnote 24

While disputing the (structural realist) view that such competition is inevitable, Lake highlights the agency of the US and China but questions whether either have the ‘self-restraint to limit domestic rent-seeking interests who will undoubtedly demand economic protections at home and special privileges in their international spheres of influence’.Footnote 25 The effect is the creation of ‘economic zones’ that favour the firms and investors of one power by excluding the economic agents of the other.Footnote 26

As part of this creation of exclusive economic ‘zones’, competition of the new Cold War is not characterised so much by territorial control, but rather over ‘networks and their structures’.Footnote 27 As Schindler and colleagues have argued, power – both geopolitical and economic – is waged through ‘network centrality’, whereby actors seek to ‘gain privileged access to strategic inputs, manage the circulation of information, exert control over the wider division of labour, establish standards, exclude competitors … and capture value within production networks’.Footnote 28 There are three elements central to this form of geopolitical-economic competition: infrastructure, supply chains, and technology.

Infrastructure is increasingly a site of US–China competition. Rather than take over territory or direct control, the aim is ‘to integrate territory into value chains anchored by their domestic lead firms through the financing and construction of transnational infrastructure (e.g., transportation networks and regional energy grids)’.Footnote 29 This is best reflected in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In 2013, China’s President Xi Jinping announced the BRI under its original ‘One Belt, One Road’ moniker.Footnote 30 It promised to create a network of infrastructure projects connecting maritime and continental Asia, Europe, and Africa. As Schindler et al. argue, the BRI has a territorial logic as its ‘corridors are meant to orient vast territories towards China and are anchored by key nodes such as special economic zones and logistics hubs’.Footnote 31 Ultimately, the BRI affects how states are ‘drawn into the global economy’.Footnote 32

Supply chains are also central to how states seek to advance ‘network centrality’. The 2018–19 trade war and subsequent COVID-19 pandemic exposed US dependencies and potential for global disruption with deleterious effects on security and economies. The COVID-19 pandemic sparked intense political debate in the United States about the need for strategic autonomy and reshoring (i.e., returning manufacturing to the US and/or North America).Footnote 33 While supply chains were largely viewed through an economic lens, they are now viewed through a strategic lens.

The third dimension is the weaponisation of technology for strategic ends. Geopolitical-economic competition has set the backdrop for US adoption of economic interventionist measures to defend its economic and security interests against a rising China. The Biden administration implemented significant protectionist measures in the context of increasing strategic competition, including in trade and manufacturing (the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act), technology (restricting US investments, screening foreign investment, and strengthening export controls in critical areas such as artificial intelligence (AI) and semi-conductors), and efforts to develop supply chains and reduce dependence on foreign minerals. In its own words, the Biden administration sought to implement ‘an industrial strategy to revitalise domestic manufacturing, create good-paying American jobs, strengthen American supply chains, and accelerate the industries of the future’.Footnote 34 This included policies to restrict Chinese telecommunication companies such as Huawei and ZTE from 5G networks and boosting American semiconductor research, development, and production through the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022. The 5G mobile internet standards reflect the ‘hard infrastructure’ of the internet, and part of the economic exclusion is being able to set technology standards and control global communications technologies.

The US approach, described by some as ‘de-risking’, has sought to reduce dependency on single countries or suppliers for critical resources, technology, and supply chains. Rather than ‘decoupling’, this approach seeks to both strengthen domestic capabilities and ‘derisk’ international trade by developing new or alternative trade relationships and diversifying supply chains across countries. In 2022, the concept of ‘friendshoring’ emerged, primarily by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who declared that the US could not ‘allow countries to use their market position in key raw materials, technologies, or products to have the power to disrupt our economy or exercise unwanted geopolitical leverage’.Footnote 35 Frequently associated with semiconductor supply chains, including by YellenFootnote 36 and various think tank analysts,Footnote 37 the core idea behind friendshoring was to find a middle ground between maintaining global supply chains and ‘reshoring’ (i.e., bringing production back to the US). To maintain global supply but reduce vulnerabilities that accompany reliance on geopolitical rivals in critical areas, the US would restructure supply chains to rely more on allies and trusted partners.

The Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific concept provided the important backdrop to this shift to friendshoring. In a November 2023 speech at the Asia Society on the Biden administration’s economic approach towards the Indo-Pacific, Yellen stated that:

We see economic engagement with the Indo-Pacific as crucial to bolstering our supply chain security. Our critical supply chains are too vulnerable to risks, as the disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed. So, along with massive investments at home through the President’s economic agenda, we’re pursuing an approach I’ve called friendshoring: seeking to strengthen our economic resilience through diversifying our supply chains across a wide range of trusted allies and partners. Across the Indo-Pacific, the Administration is pursuing multilateral engagements to better coordinate supply chain efforts – from monitoring supply chain disruptions to responding to supply chain crises. And we’re making supply chains a focus of our bilateral engagements as well.Footnote 38

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), initially consisting of fourteen states, would seek a regional arrangement that ‘will enable the United States and our allies to decide on rules of the road that ensure American workers, small businesses, and ranchers can compete in the Indo-Pacific’.Footnote 39 In coping with a loss of US primacy, the ‘friendshoring’ strategy emphasised the role of states that are friendly or neutral to the United States.Footnote 40 Shared geopolitical interests and values would determine economic relationships and permit a greater interventionist role for the state in the market, including those relevant to critical infrastructure, supply chains, and technology to reduce the risk of disruption.Footnote 41 Perhaps unsurprisingly, economists argued that friendshoring is costly for most economies, warning that such efforts to distort market economics ‘could undo the globalisation that has been the prevalent force that shaped the international trade in recent decades’.Footnote 42 Others were more optimistic, with some arguing that ‘friendshoring may positively assist in diversifying supply chains from countries that present geopolitical risk, and can be done with the intention to minimize the supply chain vulnerabilities and create a resilient network with trusted or allied partners’.Footnote 43 In any case, the idea of friendshoring contributes to ‘the fragmentation of the global economy along lines that are politically drawn rather than economically derived’.Footnote 44 Friendshoring is therefore a response by the US to the challenges presented by China in the competition around technological, infrastructure, and supply chains, driven by the ‘race’ for economic privilege and zones of exclusion that, according to Lake, reflects a self-fulfilling competition dynamic similar to the security dilemma.

The new geopolitical-economics of submarine cables

Competition over submarine cable infrastructure is not new.Footnote 45 These infrastructures have been attacked, censored, and exploited, and a site of geopolitical competition and efforts of national control since cable networks begun to be laid in the mid-1800s. Since submarine cables networks began to proliferate, the relative influence of and control by states and private interests have varied depending on a complex set of legal, geographic, technological, temporal, commercial, and strategic considerations. While submarine cable security was deprioritised by many states in the post–Cold War period, China’s forays into the market – through its Digital Silk Road – have re-ignited cable scrutiny in the West.

Undersea cables combine all three defining elements of the new Cold War’s geopolitical-economic competition: infrastructure, supply chains, and technology. The idea of ‘network centrality’ in infrastructure, supply chains, and technology is evident in China’s Digital Silk Road. When the Digital Silk Road first emerged as part of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2015, optical cable network infrastructure was its first concern, and cyber security, digital transformation, advanced technology, and innovation only followed sometime later.Footnote 46 According to China’s joint National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce action plan titled ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road’, China’s aim was to ‘build bilateral cross-border optical cable networks at a quicker pace, plan transcontinental submarine optical cable projects, and improve spatial (satellite) information passageways to expand information exchanges and cooperation’.Footnote 47

While scholars have argued that China’s Digital Silk Road is neither ‘coherent’ or a ‘geo-strategic masterplan’,Footnote 48 the strategy nevertheless raised concerns in the West that China was attempting to dominate the undersea cables market, giving Beijing ‘potentially unfettered access to the vast amounts of varied data transmitted through these cables’.Footnote 49 There are also risks of states gaining control over information communication technology during times of conflict, for which there are historical precedents. For example, Britain’s monopoly over radio transmissions in the late nineteenth century was ‘successfully wielded … against Germany during the First World War by cutting German cables, monitoring German transmissions, and forcing German traffic onto British-controlled networks, uncovering the Zimmerman telegram proposing military collaboration with Mexico that helped bring the United States into the war’.Footnote 50 China’s Digital Silk Road is therefore viewed by some analysts as a ‘potent instrument that could be wielded to potentially disrupt, sabotage, or clandestinely gather intelligence from undersea cables’.Footnote 51 Such ambitions ‘involve an attempt at multi-regional reordering and, by proxy, global reordering’,Footnote 52 and could be used to ‘establish a Sino-centric global digital order by expanding and exporting Chinese technology through state-controlled and private corporations’.Footnote 53

China’s escalated efforts at submarine cable market capitalisation through its BRI have contributed to the emergence of a new era of cable geopolitical-economic competition. As we argue below, the ‘friendshoring’ of undersea cables can be considered part of the US countering Chinese efforts to establish ‘network centrality’ by setting up its own exclusive network that includes ‘friends’ but excludes rivals. This new era has witnessed a new set of considerations driving state intervention into the submarine cable networks, including: the digital connectivity imperative, the erosion of state control, new Sino–US competition dynamics, and regional outlooks. The current ‘epoch’ of undersea cable politics, therefore, can be distinguished from those that preceded it. While there are many similarities to preceding time periods, four key elements distinguish this current period of undersea cable security from those that preceded it.

First, digital connectivity underpins modern societies to a greater degree than ever before. While submarine cable networks and the information these networks transmit have always been important, as more of society’s functions are digitised, submarine cables remain the primary data conduit between terrestrial bodies. These cables transmit myriad data, including private communications, banking data, stock market transactions, medical data, scientific data, government communications, data centre traffic, and AI transmissions. An estimated US$10 trillion in financial transactions is transmitted via undersea cables daily.Footnote 54 The global financial system came to rely upon the microsecond-level transmission speeds fibre optic cables enable, making them ‘the only practical option for meeting current and future demand’.Footnote 55

In contrast to earlier periods, in the internet age there has been unprecedented demand for high-bandwidth global connectivity delivered cheaper than satellites and with fewer disruptions.Footnote 56 Between 2019 and 2023, global annual bandwidth demand has more than tripled, totalling five petabits per second in 2023.Footnote 57 Furthermore, between the same period, most regions experienced a 35–40 per cent compound annual growth in used international bandwidth, with Africa leading at almost 50 per cent.Footnote 58 This large growth in bandwidth requirements is primarily due to the demands of content and cloud providers including Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon.Footnote 59 To keep up with growing global bandwidth demand, large sums are being spent to construct new submarine cable networks. In the last eight years, USD$2 billion was spent on average per year to lay cables.Footnote 60 Furthermore, according to the latest data, between 2024 and 2026, over USD$10 billion is forecast to be spent on new submarine cable networks.Footnote 61 Put simply, submarine cables are an indispensable part of our modern digital society, and despite improvements in satellite data transfer, physical subsea cables remain the internet’s backbone.

Second, state sovereignty and direct control over submarine cable networks eroded in the immediate post–Cold War era as many state-owned telecommunications entities were privatised. Indeed, the role of the state (and militaries) in submarine cable networks has fluctuated since cables began to be laid in the 1800s. For the British in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – leaders in subsea networks – ‘strategic motives’ drove cable network development to a far greater extent than commercial imperatives.Footnote 62 Headrick notes that while commercially viable cable networks were laid for business and personal communication purposes before the 1880s, many networks were constructed prior by Britain for ‘political reasons’ – often at the behest of Admiralty, the Colonial Office, the War Office, and the Foreign Office.Footnote 63 As cable routes across the Pacific were not economically viable, the Pacific Cable Board was established by Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand in 1896 to connect the British empire and finish Britain’s global ‘All Red Line’ – operational by 1902.Footnote 64 Scholar Jill Hills argues that ‘the Indian Mutiny, the Crimean War, the American Civil War, the Boer War, World War I, and the possibility of a second world war instigated the expansion of the submarine cable system, backed by British subsidies, and then its defense’.Footnote 65 During the Cold War period, consortia dominated by monopoly telecommunications companies primarily constructed international undersea cables.Footnote 66 During this era the ‘club’ or ‘consortium’ ownership model saw cable network projects undertaken as collaborations between various state-owned or represented telecommunications providers, primarily American, Japanese, British, and French.Footnote 67 According to Starosielski, ‘with the breakup of the colonial empires, the focus of securing the cable network shifted from routing via one’s territory or colonial holdings to having national control over the processes of building, operating, and maintaining the cable network’.Footnote 68 She adds that ‘the national development of a cable industry was a strategy to insulate cables from the potential interference of other nations in their cable construction and operation, since everything could be controlled and accounted for by the incumbent telecommunications company’.Footnote 69

In the post–Cold War period, however, privatisation reduced the amount of state control over undersea cables. The World Trade Organization’s 1997 telecommunications agreement formalised increased international competition, allowing private equity a greater role in network development.Footnote 70 As a result, due to the erosion of direct state control and ownership, ‘national regulation has become increasingly important to the assertion of public priorities over corporate profit’.Footnote 71 Key actors in undersea cables were no longer states, and cable networks are generally privately owned. The approximately 600 undersea cable networks globally are primarily owned and operated by private telecommunications firms or technology companies,Footnote 72 and constructed by private industry. According to scholar Brendon J. Cannon, in the modern era, ‘cables are not sovereign property as such. They are instead a mix of public and private and often involve consortium.’Footnote 73 In more recent years, the consortia model is being replaced by so-called hyperscalers – large technology firms such as Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon, which do not require partners and can unilaterally commission cable networks.Footnote 74

Third, Sino–US competition drives international affairs with networks at the core. As this article has made clear above, Sino–US competition is fuelling competition over submarine cable network construction. Historically, nations have competed to control seabed networks. While a comprehensive list would require a longer treatment, some representative cases are given. For example, even before the First World War, Germany begun to install an alternative global cable network to avoid British-controlled cables. Germany supported its domestic cable suppliers and between 1896 and 1911 German firms laid cables to Spain, the Azores, and the Canary Islands, which were subsequently extended to the United States, Liberia, and South America as well as Germany’s west African colonies.Footnote 75 Germany also built a cable network in the Pacific, which linked Yap in the Caroline Islands to the Dutch East Indies, Guam, and China.Footnote 76 Additionally, for the United States, Britain’s systematic destruction of the German network (which the US used) during the First World War, in addition to Britain’s unrelenting submarine cable censorship during the ensuing conflict, led US officials to build its own global communication network of submarine cables and long-distance radio.Footnote 77

Japan used submarine cables to consolidate its empire during both its Meiji era and while attempting to create the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Indeed, Japan long prioritised attaining autonomy in its international communications and constructed a comprehensive network in East and Southeast Asia.Footnote 78 According to Daqing Yang, during this period Japan’s submarine cable network was a ‘technology of expansion for Meiji Japan’, and in the late 1930s ‘the artery of the new imperium’ and a ‘technology of consolidation’.Footnote 79 Yang asserts that Japan’s international cable network allowed the Japanese to ‘imagine its [eventual] wartime empire’.Footnote 80 In the Cold War era, despite intense US–USSR strategic competition, the Soviets were not major submarine cable network players and did not compete with the United States for dominance of global subsea telecommunications. However, in this modern era, the way in which China is attempting to dislodge the established American, French, and Japanese firms is unprecedented in speed and scale, and has parallels to German and Japanese efforts at empire building.

Fourth and finally, as major powers are relatively well connected physically, states are seeking to connect smaller regional states and use foreign assistance budgets to do so. States are not only concerned about cables that connect respective shores, but are increasingly concerned about the suppliers of cable networks at a regional level. Furthermore, states are subsidising cable networks (often through foreign assistance budgets) to connect regional states (either for the first time or to add redundancy) even if such cable connections are not otherwise commercially viable. In this sense, and as the below analysis makes clear, in the midst of a new great power rivalry, the construction and installation of cables is increasingly viewed as a ‘strategic threat’, and a vulnerability,Footnote 81 even if the network does not connect the major power directly. In sum, states are taking a regional view to cable connectivity, beyond concern for just respective physical connections. These four factors – the digital connectivity imperative, the erosion of state control, new Sino–US competition dynamics, and regional outlooks – define the current ‘epoch’ of undersea cable politics and are reflected in the analysis of our case studies below. Yet, what can also be discerned is a new wave of governments attempting to gain back state control for security reasons.

Friendshoring cable networks

The balance of this article uses a qualitative, comparative case study approach to demonstrate how these geopolitical-economic competition dynamics are at play in the modern development and installation of various Indo-Pacific submarine cable networks in the pursuit of ‘network centrality’. These three cases, all located in the Pacific Ocean – the epicentre for Sino–US competition – have been selected as they demonstrate emerging ‘friendshoring’ dynamics. These cases exhibit how a political crisis was created by China’s forays into the submarine cable network installation market in the Pacific – broadly part of its Digital Silk Road Initiative – and illustrate how Western bureaucratic infrastructures were created to maintain network centrality without public controversy. These cases are noteworthy as they represent the genesis of regional cable friendshoring in the Indo-Pacific, in response to China’s network-centric ambitions.

To understand and describe these cases, this article cites a variety of publicly available primary source materials, including official policy statements and speeches. While states and leaders are not always explicit in explaining their motivations, there has been considerable scholarly literature that argues that the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept of region created and disseminated by states such as Japan, Australia, and the US has emerged as a consequence of concerns over China’s rising influence and its use of infrastructure funding mechanisms such as the BRI.Footnote 82 This broader regional setting contextualises the actions and motivations of states ‘friendshoring’ the seabed. The analysis also utilises international media reporting, including by investigative journalists, in addition to grey literature and government reports to substantiate the cases. In particular, the analysis focuses on the ‘strategic narratives’ that key political actors use to justify respective Indo-Pacific policies and delegitimise the interests and actions of others. It should be noted that small island nations have often been the sites of data connectivity geopolitics.Footnote 83 However, according to Watson, in the Pacific ‘endogenous views regarding undersea cables and exogenous perspectives’ differ, and many leaders of Pacific island nations are focused on providing robust and economical digital connectivity, rather than geopolitical competition.Footnote 84

In chronological order, this section analyses the Coral Sea Cable System, the East Micronesia Cable System, and the Palau Spur Cable. In response to attempts by Chinese-based firms to gain submarine cable market share primarily in the Pacific (as detailed above), these cases show how Australia, Japan, and the US have coordinated to thwart Beijing’s attempts. Each of these cases demonstrate how submarine cable networks have become an arena for geopolitical-economic competition in the Indo-Pacific, as Western allies collaborate to maintain network centrality through ‘friendshoring’.

Coral Sea Cable System

The 4,700 kilometre Coral Sea Cable System, operational in December 2019 and (eventually) costing US$93 million, connects Sydney with Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea and Honiara, Auki, Noro, and Taro in the Solomon Islands (see Figure 1 below).Footnote 85 Laid by Australian-based Vocus Communications and Alcatel Submarine Networks, Inc. (then owned by Nokia, now owned by the French Government), the network is owned by the Coral Sea Cable Company, registered in Australia but owned in equal parts by the Commonwealth of Australia, PNG DataCo, and the Solomon Islands Submarine Cable Company.Footnote 86 While PNG has existing submarine network links, Solomon Islands previously had no submarine cable connection and relied on satellites for voice and data transfer. As this case study demonstrates, while China eyed the Coral Sea Cable System’s supply, in dramatic circumstances at the eleventh hour, the United States, Japan, and Australia intervened to ‘friendshore’ this critical data link.

Figure 1. Map of the Coral Sea Cable System.Footnote 93

Prior to 2016, Solomon Islands was working with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to finance a cable between Sydney and Honiara, plus further domestic connections, which was to be funded through a combination of grants and loans.Footnote 87 At an expected cost of US$60 million, in 2012 the Asian Development Bank approved US$17 million in project funding (US$7.5 million as a grant and US$10.5 million as a loan).Footnote 88 According to a local media report in September 2012, the cable was expected to be operational by December 2013.Footnote 89 However, despite plans for the cable to be laid by a US–British firm, which had won the competitive ADB tender and had already secured Australian permission to land the cable in Sydney, the Solomon Islands government began pursuing an alternate deal with the China-based Huawei Marine Networks in mid-2016.Footnote 90 The Solomon Islands’ decision to circumvent the ADB process prompted the bank to cancel the project as Solomon Islands officials would not disclose the identity of the fellow bidders.Footnote 91 According to an ADB spokesperson reported by Radio New Zealand, ‘the Huawei contract was developed outside of ADB procurement processes. ADB is committed to ensuring ADB financing is used within ADB procurement guidelines: On that basis, ADB could no longer be involved and therefore cancelled the project in May 2016.’Footnote 92

Despite the ADB process breaking down, Solomon Islands officials continued to work with Huawei, amid mounting pressure by Australia to abandon its agreement with the Chinese tech firm. In a rare move in June 2017, the then-director-general of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (Australia’s secretive foreign human intelligence agency) Nick Warner was sent to Solomon Islands to meet with Prime Minister Sogavare and warn him against using Huawei.Footnote 94 Indeed, Canberra did have leverage as the proposed cable would require an Australian permit to land in Sydney, which Canberra was unlikely to grant.Footnote 95

Despite Australia’s efforts, in July 2017 Huawei and the Solomon Island Submarine Cable Company inked a deal to connect the archipelagic nation to Sydney and expected the network to be complete by the following year.Footnote 96 Allegations were made in the Australian media in August 2017 that Huawei paid the ruling party of Solomon Islands a A$6.5 political million donation.Footnote 97 According to a report, the donation prompted the abandonment of regular procurement processes and selection of Huawei. Although Huawei Australia’s media relations representative issued a statement denying the allegations and noting that ‘Huawei does not involve itself in politics’,Footnote 98 this incident nevertheless cast doubt over the process’s transparency.

Despite this 2017 agreement between Solomon Islands and Huawei, in January 2018 Australia announced it had agreed to fund the cable project’s lion share via its foreign development budget.Footnote 99 Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade stated it had contracted Australia-based Vocus to start initial scoping work and noted that the project would be consolidated with a formerly separate cable project connecting Papua New Guinea.Footnote 100 Journalist and National Security Correspondent for Australian newspaper The Age, David Wroe, noted in January 2018 that ‘the step is highly significant as it shows the lengths to which the Turnbull government was willing to go to ensure the cable project could go ahead without Huawei’s involvement’.Footnote 101

According to then-Solomon Islands Prime Minister Rick Houenipwela speaking in June 2018, ‘We have had some concerns raised with us by Australia, and I guess that was the trigger for us to change from Huawei to now the arrangements we are now working with Australia’.Footnote 102 Houenipwela added that ‘looking at the two projects, from our perspective this [Australia’s offer] is the best one … The cost is much, much less for us. Australia is paying two thirds of the cost.’Footnote 103 Australia’s then Foreign Minister Julie Bishop commented publicly in June 2018, illustrating Canberra’s motivation, that ‘We put up an alternative, and that’s what I believe Australia should continue to do … I want to ensure that countries in the Pacific have alternatives, that they don’t only have one option and no others.’Footnote 104 According to former Lowy Institute analyst Jonathan Pryke, speaking to journalists in July 2021, Huawei Marine’s hardware connecting to internet infrastructure in Sydney ‘was seen as a red line that Australia would not cross and so we [Australia] jumped in with a better deal providing the cable as a grant that would be implemented with a procurement partner of Australia’s choosing – that wouldn’t be Chinese’.Footnote 105

The Coral Sea Cable System crisis prompted Australia, the United States, and Japan to implement various formal mechanisms to proactively counter China’s forays into the submarine cable market. It is important to note that this initiative was led by an Australian Coalition government that was, at the time, concerned about China’s activities in the Pacific region and had implemented a ‘Pacific step-change’ and then ‘step-up’ from 2016 to counter Beijing’s rising influence.Footnote 106 Contemporarily, the United States’ 2018 National Defense Strategy turned US efforts to global competition, including with China,Footnote 107 and Japan’s 2018 National Defense Program Guidelines highlighted China’s rise and consequences for the existing balance of power.Footnote 108 In this case, the three nations on 30 July 2018 jointly announced a ‘Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific’.Footnote 109 According to the three nations, the trilateral partnership aimed to:

mobilise investment in projects that drive economic growth, create opportunities, and foster a free, open, inclusive and prosperous Indo-Pacific. We share the belief that good investments stem from transparency, open competition, sustainability, adhering to robust global standards, employing the local workforce, and avoiding unsustainable debt burdens.Footnote 110

The partnership was formed between Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the United States Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), and the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation. Additionally, later in 2018 Australia announced the creation of its Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, which partners ‘with governments and private sector in the Pacific and Timor-Leste, to provide grant and loan financing for high quality, transformational energy, water, transport, telecommunications, and other infrastructure’.Footnote 111

Huawei’s attempt to circumvent ADB procurement processes and install an international submarine cable network in the Pacific alarmed Australian officials and promoted unprecedented political intervention. This incident was the catalyst for modern seabed friendshoring for two reasons. First, rather than allow China’s Huawei to install the network, Canberra stepped in and engaged both Australian fibre network provider Vocus and importantly also French-based firm Alcatel Submarine Networks to undertake the project. In this sense, and as Pryke above notes, Australian officials were not necessarily attempting to simply appoint an Australian firm but were attempting to contract a ‘trusted’ international supplier from a friendly state, thereby friendshoring the seabed network. Second, the Coral Sea Cable System crisis precipitated a formal trilateral grouping between the United States, Japan, and Australia to proactively friendshore submarine cable network supply. Alarmed by China’s attempt at installing submarine cable networks in the Pacific, the Coral Sea Cable System prompted these three Western nations to friendshore the Indo-Pacific seabed.

East Micronesia Cable System (EMCS)

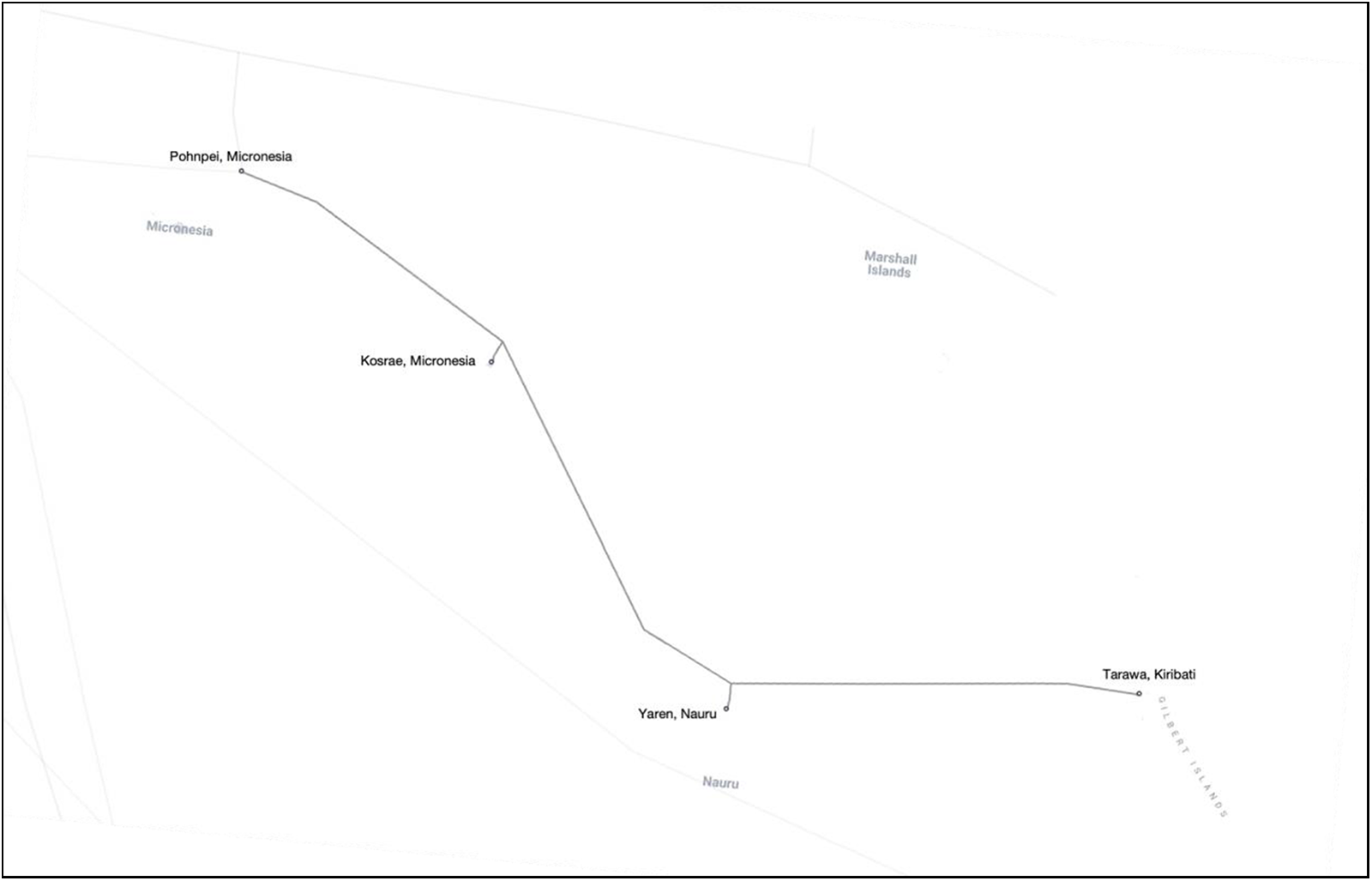

With an expected completion date in late 2025, the US$95 million East Micronesia Cable will connect Kiribati (Tarawa), Micronesia (Kosrae), and Nauru (Yaren) to the existing HANTRU-1 cable, which lands in Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia (see Figure 2 below). The nearly 3,000-kilometre existing HANTRU-1 cable, operational in 2010 and laid by US-based SubCom, connects Guam (a global cable hub) to the Marshall Islands and Pohnpei. The HANTRU-1 cable was funded by the US Army and connects the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands, with which the United States has a Compact of Free Association.Footnote 112

Figure 2. Map of the East Micronesia Cable System.Footnote 114

However, like the Coral Sea Cable System, the East Micronesia Cable System had a rocky beginning. Originally a World Bank-led project, the possibility of a Chinese firm winning the tender rang alarm bells in Western capitals. According to reporting by Reuters, in July 2020 diplomats in Washington told their FSM counterparts about the way Chinese firms including Huawei Marine cooperate with Beijing’s intelligence and security architecture.Footnote 113 The United States reportedly told FSM that Huawei Marine would cooperate with China’s intelligence apparatus and thus deemed the firm an unacceptable risk.Footnote 115 Reuters was told by the FSM government that it was discussing the issue with bilateral partners, ‘some of whom have addressed a need to ensure that the cable does not compromise regional security by opening, or failing to close, cyber-security related gaps’.Footnote 116 In response to reports about such warnings from Washington to FSM, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin in December 2020 accused the United States of ‘smearing’ Chinese firms.Footnote 117

Simultaneously in 2020, Huawei divested its stake in Huawei Marine after numerous rounds of US sanctions were applied in response to charges of espionage.Footnote 118 Moreover, Huawei was added to the US Department of Commerce’s ‘Entity List’, which restricts trade with the firm.Footnote 119 As a result, an 81 per cent shareholding acquisition in Huawei Marine was purchased by the Suzhou-based fibre cable manufacturer Hengtong Optic-Electric Co Ltd., which is listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. Following this acquisition, in November 2020 Huawei Marine Networks was rebranded as HMN Technologies (commonly known as HMN Tech) and continued operations.

Following Huawei Marine’s conversion to HMN Tech, ultimately, the World Bank tender came unstuck when in June 2021 HMN Tech submitted a bid 20 per cent lower than Alcatel Submarine Networks and Japanese NEC.Footnote 120 In response, the World Bank declined to award a contract, citing ‘non-responsiveness to the requirements of the bidding documents’.Footnote 121 According to an anonymous source reported by Reuters, HMN Tech’s bid was competitive against the World Bank’s terms, and ‘given there was no tangible way to remove Huawei [HMN Tech] as one of the bidders, all three bids were deemed non-compliant’.Footnote 122

In December 2021, Australia, the United States, and Japan announced a joint plan to connect Nauru, Kiribati, and the Federated States of Micronesia with a submarine cable.Footnote 123 The Australian Government noted that ‘the six-country collaboration highlights the commitment to maximising the region’s stability, security and prosperity, and the countries will continue to work together on telecommunications infrastructure projects that support long term social and economic growth’.Footnote 124

According to a joint media statement on 12 December 2021 issued by David W. Panuelo, President of the Federated States of Micronesia; Yoshimasa Hayashi, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Japan; Taneti Maamau, President of the Republic of Kiribati; Lionel Aingimea, President of the Republic of Nauru; Antony J. Blinken, Secretary of State, United States of America; and Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne:

This is more than an infrastructure investment. It represents an enduring partnership to deliver practical and meaningful solutions at a time of unprecedented economic and strategic challenges in our region […] It is a further demonstration of our shared commitment to quality, transparent, fiscally sustainable, catalytic infrastructure partnerships with, and between, Pacific nations.Footnote 125

Under this new collaborative agreement, the East Micronesia Cable System is being laid by Japan-based NEC and consists of approximately 2,250 kilometres of optical fibre. Work commenced in June 2023Footnote 126 and these nations are among the final Pacific nations to be connected via a submarine cable.Footnote 127 At an estimated USD$95 million total cost, Australia is granting up to approximately USD$43.3 million (AUD$65 million), and the Japanese and US contributions are undisclosed.Footnote 128

As occurred in the Coral Sea Cable System case, the East Micronesia Cable System demonstrates seabed friendshoring. In this case, the United States intervened to lobby parties to the cable against accepting a Chinese offer, despite the substantial price difference to the French and Japanese alternatives. Ultimately this pressure, in addition to an alternative offer made by the United States, Japan, and Australia, swayed these Pacific leaders to accept a Western alternative. Unlike the Coral Sea Cable System, which is part owned by the Australian government, the East Micronesia Cable System is owned by local operators, including Kiribati’s BwebwerikiNET Limited (BNL), Nauru Fibre Cable Corporation (NFCC), and the Federal States of Micronesia Telecommunications Cable Corporation (FSMTCC). Importantly, rather than HMN Tech, Japan’s NEC was selected as a ‘trusted’ supplier – sufficiently trustworthy to connect its network to the US-Army funded HANTRU-1 cable system that connects the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site.

Palau Spur Cable

While the East Micronesia Cable System was being fought over, officials in Tokyo, Washington, and Canberra were rapidly actioning their newly established Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific to fund another cable network before China could make a counter-offer. The Republic of Palau, with a total area of only 466 square kilometres, borders the Federated States of Micronesia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Palau was connected by only one NEC-laid submarine cable, the SEA-US, which linked the United States’ west coast to Philippines and Indonesia via Micronesia, Guam, and Hawaii. However, the new transiting ECHO submarine cable, owned by hyperscalers Google and Meta and laid by Japan’s NEC, provided an opportunity to mitigate Palau’s lack of redundancy. Connecting Singapore and Indonesia with Eureka in California via Guam, ECHO at the time was slated as one of the world’s longest cable projects.Footnote 129

Connecting Palau via a dedicated branch (also called a spur line) to this cutting-edge trunk cable became the first cable project under the new Australia, Japan, and United States agreement (see Figure 3 below). According to a 2020 US Department of State Fact Sheet, at an expected USD$30 million cost, the United States was providing USD$4.6 million, USD$7 million was being contributed by Palau from its Palau Compact Review Agreement with the United States, the Palau state-owned Belau Submarine Cable Corporation was contributing USD$1 million, Australia was contributing approximately USD$10 million (which includes a loan of USD$9 million from its Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific), and Japan’s contribution was to be determined.

Figure 3. Map of a section of the Echo cable network showing the Palau Spur Cable.Footnote 130

According to former Secretary of State Michael Pompeo at a joint press conference in October 2020 with both Australian and Japanese foreign ministers upon announcing the project, he noted that ‘this is what free nations do – they support one another openly, transparently, and for mutual benefit’.Footnote 132 In June 2022 the Palau spur laying commenced and the fibre is expected to be ready for service in mid-2026.Footnote 133

While from publicly available information it seems that the Palau spur was not eyed by Chinese cable firms, it nevertheless demonstrates Western seabed friendshoring. This cable project demonstrates the success of the Australia–Japan–United States trilateral partnership, as well as Australia’s new Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific, as the spur line could be coordinated and funded without a public crisis due to a competing bid by HMN Tech. Following the two public policy crises as noted above, the Palau Spur Cable intervention via the trilateral partnership illustrates how diplomatic and bureaucratic infrastructures established by Japan, the United States, and Australia could effectively and efficiently exclude China from seabed critical infrastructure projects in the Pacific, before the East Asian nation’s industry could mount a competing business case. Indeed, another cable network was subsequently funded as part of the Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific – the Tuvalu Vaka Cable – which is Tuvalu’s first subsea connection. In addition to Japan, the United States, and Australia, the governments of New Zealand and Taiwan also contributed to the USD$56 million Tuvalu Vaka Cable.Footnote 134

The geopolitical-economics of Indo-Pacific cables

All three cases demonstrated the importance of geopolitical competition in shaping how the United States and its allies invested in cable networks in the Indo-Pacific. As part of creating exclusive economic ‘zones’, these cases add weight to the argument expressed above that the new Cold War has been defined less by territorial control and more by networks and infrastructure, which has created a substantively new geopolitical-economics of submarine cables.Footnote 135 The cases highlight the efforts of states in developing ‘network centrality’: providing privileged access to some actors over others, managing the flow or channels of information, and excluding competitors. Submarine cable infrastructure has therefore become an arena for geopolitical-economic competition, as security considerations have become intertwined with and ultimately have outweighed economic factors in decision-making. Western states have become increasingly willing to provide significant financial support to prevent Chinese companies from building communications infrastructure that could potentially compromise security.

There are three key drivers that explain the actions of the US and its partners. First, as US–China strategic competition intensifies, both sides are looking for more ways to provide public goods to smaller countries across the Indo-Pacific. In managing strategic competition, many smaller states in the Indo-Pacific continue to adopt omni-alignment or ‘hedging’ strategies by avoiding alignment with powerful countries.Footnote 136 While friendshoring states aim to provide public goods to smaller states in the race for influence via infrastructure projects, a range of network options provide smaller countries with benefits as they seek to improve respective telecommunications security and leverage strategic competition to their advantage. Many of these countries are viewed by the West as at risk of becoming too close to Beijing. Australia is, for example, concerned that the Chinese military may be able to gain a foothold in the South Pacific through the development of a military base.Footnote 137 By providing a valuable and much-needed product – submarine cables and associated digital connectivity – these countries aim to shore up influence and goodwill in areas such as the South Pacific as part of a broader context of infrastructure and development competition. Provision of these critical infrastructures creates a dependency that can be leveraged and weaponised depending on the future dynamics of geopolitical-economic competition.

A second and related driver is excluding China from cable networks. While the US and partners aim to increase respective influence, they simultaneously seek to counter the infrastructure projects that are being developed by China in its Belt and Road Initiative that aim to increase Beijing’s regional power and influence. The cases demonstrate how coordination between allied countries has sought to exclude Chinese companies (particularly HMN Tech and its suppliers) from critical submarine cable infrastructure in the Pacific. This collaboration also established a diplomatic and bureaucratic framework for ‘like-minded’ countries to efficiently fund future Pacific cable projects before China could make competitive offers, as evidenced by the subsequent Palau Spur Cable project. The Coral Sea Cable System case similarly catalysed the formation of the ‘Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific’ in 2018, establishing a formal mechanism to proactively counter Chinese involvement in submarine cable infrastructure through the deliberate selecting of suppliers that are viewed as sharing political values. By excluding HMN Tech from new networks, the firm cannot grow and cannot expand its infrastructural footprint. As a result, the firm will struggle to innovate and be a market leader – a position that American, French, and Japanese firms enjoy. For these Western firms in the submarine cable installation market, this heightened geopolitical-economic competition is being capitalised on, as networks not otherwise commercially viable are being subsidised by states. Moreover, firms that are perceived as ‘trusted’ or ‘secure’ by states have a competitive advantage, leveraging respective positions as ‘national champions’ to secure contracts and increase revenue.

A third driver is the importance of intelligence and informational security in shaping the security concerns of the US and its allies. In the Coral Sea Cable System case, Australia intervened to prevent China’s Huawei from building a submarine cable connecting Solomon Islands to Sydney, despite an initial agreement between Solomon Islands and Huawei, due to national security concerns raised by Australian intelligence agencies. The East Micronesia Cable also faced significant geopolitical challenges when a Chinese firm (HMN Tech, formerly Huawei Marine) submitted a competitive bid, prompting security concerns around potential intelligence risks. It is notable that despite HMN Tech offering a bid 20 per cent lower than competitors, Japan’s NEC was ultimately selected as the ‘trusted supplier’ for the project. According to analyst Hayley Channer, controlling submarine cables is one way to grapple with the risks that China’s rise presents to informational security.Footnote 138 Channer writes that ‘as well as providing developing countries with greater digital capacity and enhanced opportunity for economic growth, strategically, [friendshoring the seabed] crowds out Chinese-owned cables, reducing Beijing’s espionage capability’.Footnote 139 Submarine cable networks constrict or aggregate data into limited conduits that are then susceptible to interception. As such, networks installed and operated by rivals introduce distinct data integrity concerns – concerns that drive network centrality through intervention.

Conclusion

As this article argues, major powers are pursuing ‘network centrality’ through collective yet exclusionary control over submarine cables. In this new Cold War era, which is characterised by geopolitical-economic competition over networks rather than territory, submarine cable networks have become a key battleground for control and centrality. States are utilising a variety of policies and have created unilateral and multilateral bureaucratic infrastructures to enhance respective centrality. As submarine cables are the primary conduit of information flows – central to the functioning of modern society – the United States and its partners will continue to defend their leading role, especially in the face of China’s Digital Silk Road, including through ‘friendshoring’.

Through three recent case studies, the Coral Sea Cable System, the East Micronesia Cable System, and the Palau Spur Cable, the article demonstrates how states are pursuing network centrality through these critical infrastructures. These cases are important as the catalyst for submarine cable regional network competition in the modern era, as the West scrambled to respond to China’s forays into the global submarine cable network market following the launch of its Belt and Road Initiative and Digital Silk Road Initiative. These cases are also significant given the Indo-Pacific as a site of strategic competition between the world’s two largest powers, China and the US. These cases illustrate some of the methods in which competition over centrality in submarine cable networks plays out between China and the West. Further research could examine the more hidden methods governments use to maintain submarine cable network centrality, including the often-complex relationships between governments and the submarine cable industry (which may indeed limit state intervention efforts),Footnote 140 the use of sanctions and export controls, and other diplomatic efforts and official representations that aim to sway third party decisions over which suppliers to engage. Various levers of statecraft are available to policymakers to maintain submarine cable network centrality, many of which are little understood.

While friendshoring states seek to reduce geopolitical risk and increase influence regionally, there are potential wider implications for the international system. By treating telecommunications – a public good – as a strategic asset, state competition in connectivity is reified. As a result of this competition, the global economy is increasingly bifurcated between China and the West, as states and respective firms are pitted against one another in a race to connect the region. Particularly in a time of political upheaval, as the second Trump administration rewrites American foreign and defence policy, the future of ‘friendshoring’ the seabed amongst Western partners will be tested. While it is too soon to tell whether the Trump administration will withdraw from this collaborative strategy of network-centric competition on the seabed,Footnote 141 the administration’s ‘America First’ policies and corresponding isolationism may hamper future joint intervention in new subsea networks. Further research in the coming years is needed to understand how submarine cable supply chain competition is evolving during the second Trump term, including whether friendshoring is continuing (with or without the US involvement).

Lastly, even as the United States and its partners subsidise new regional submarine cable networks and exclude China’s HMN Tech from new projects, what impact will these wins have on broader Sino–US competition? It must be noted that in network-centric competition, digital networks are just one network domain, and smaller countries are able to hedge by aligning with larger powers differently between network domains. In practice, even if the Solomon Islands or Papua New Guinea, for example, accept a subsidised Western submarine cable network, the nations can align with China in other network domains – whether financial, infrastructural, or production. This ability for smaller states to omni-align between network domains makes overall ‘success’ for China and the Western grouping in this new Cold War era difficult to judge, but should offer avenues for future research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the anonymous peer reviewers for insightful and constructive comments which strengthened the article.

Funding statement

The research for this article was supported by an Australian Department of Defence Strategic Policy Grant Program grant, Project 2024-053, ‘Defending Critical Seabed Infrastructure’.

Samuel Bashfield is a research fellow at the La Trobe Centre for Global Security, La Trobe University, Australia, where he studies geopolitical and defence trends, Indian Ocean security, and digital flows.

Rebecca Strating is Director of the La Trobe Centre for Global Security and Professor of International Relations at La Trobe University, Australia, where she focuses on Asian regional security, maritime disputes, and Australian foreign and defence policy.