Highlights

-

Direct surgical repair offered durable symptom relief in refractory spinal CSF leaks.

-

Subdural hematoma management should prioritize CSF leak repair to prevent recurrence.

-

Standardized diagnostic pathways improved surgical targeting and efficacy.

Introduction

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) has been attributed primarily to spinal CSF leaks, with an estimated annual incidence of approximately 5 per 100,000 individuals. Reference Urbach, Fung, Dovi-Akue, Lützen and Beck1 Its clinical manifestations commonly include orthostatic headache, vestibular and cochlear disturbances and, in some cases, debilitating neurological symptoms including myelopathy. Reference Schievink2–Reference Ferrante, Trimboli and Rubino6 Despite an increasing awareness of SIH, variability in clinical presentation often leads to diagnostic delays and under-recognition of spinal CSF leaks. Reference Yoganathan, Mariappan and Sudhakar7–Reference Subramanian, Kecler-Pietrzyk and Murphy9 One major predisposing factor involves generalized dural weakness, frequently observed in hereditary connective tissue disorders, rendering the dura vulnerable to rupture. Reference Schievink, Gordon and Tourje10–Reference Puget, Kondageski and Wray12

Spinal CSF leaks have been classified etiologically into dural tears, meningeal diverticula and CSF-venous fistulas (CVF). Reference Schievink, Maya, Jean-Pierre, Nuño, Prasad and Moser13,Reference Amrhein and Kranz14 A more contemporary radiological classification using MRI and digital subtraction myelogram (DSM) distinguished leaks into four types: ventral dural tear (type 1), lateral dural tear (type 2), CVF (type 3) and distal nerve root sleeve leak (type 4). Reference Farb, Nicholson and Peng15 Additionally, spinal longitudinal extradural CSF collections (SLECs) on spinal MRI facilitated classification into SLEC-positive (SLEC-P) and SLEC-negative (SLEC-N) groups, thereby guiding diagnostic myelography. Reference Farb, Nicholson and Peng15

Despite improvement in imaging-based localizations, treatment of CSF leaks remained challenging. While epidural blood patching (EBP) and endovascular coiling are widely practiced, outcomes vary, especially in SLEC-negative patients with meningeal diverticula or CVF. Reference Sencakova, Mokri and McClelland16,Reference Signorelli, Caccavella and Giordano17 Surgical repair has emerged as the most definitive therapeutic option in refractory cases but can be equally challenging when attempted for leaks with complex configurations. Reference Cohen-Gadol, Mokri, Piepgras, Meyer and Atkinson18 This study aimed to characterize outcomes of surgically treated spinal CSF leaks over a 6-year period and contextualize findings through a comprehensive review of the literature.

Methods

Study design and data source

This is a retrospective observational study encompassing all patients with spinal CSF leak or CVF who underwent surgical treatment between June 2017 and December 2023 in a single Canadian tertiary academic center. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network and conducted in accordance with their ethics guidelines and those of the University of Toronto. Data were retrieved from institutional electronic health records, operative records and radiological database. Informed consent for retrospective analysis of the patient’s data was obtained at the same time as for the surgical intervention. This study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement.

Patient selection and diagnostic workup

Inclusion criteria comprised adult patients diagnosed clinically with spontaneous spinal CSF leak or CVF confirmed radiologically, who underwent surgical treatment. Patients with iatrogenic leaks, such as those secondary to previous spinal surgeries or (inadvertent) lumbar puncture, were excluded. Surgical treatment was performed after a comprehensive diagnostic workup including X-rays, MRI of the brain and spine, DSM and CT scan prior to surgery. All cases were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team prior to surgical consideration.

The cranial imaging was evaluated for stigmata of intracranial hypotension, which include pachymeningeal enhancement, subdural hygroma, subdural hemorrhage, venous distention, pituitary gland enlargement and brain stem sagging. The spine, on the other hand, was specifically reviewed using a protocol with isotropic T2-weighted reformatted high-resolution sequences to identify the presence or absence of SLEC. SLECs typically appear as a ventrally located fluid collection extending cranio-caudally from the site of dural tear, although dorsal presentations are occasionally observed. A CT scan was used to assess associated pathologies, such as calcified disc herniations or osteophytes.

The DSM was obtained in different positions (prone and bilateral lateral decubitus), as described by Farb et al. and Piechowiak et al., until a set of three negative myelograms was completed or a definitive leak or CVF was localized. Reference Farb, Nicholson and Peng15,Reference Piechowiak, Pospieszny and Haeni19 CSF leaks were then classified into types 1–4, based on the classification proposed by Farb et al. Reference Farb, Nicholson and Peng15 Surgery was offered to patients who suffered from long-standing symptoms or neurological deficits and who failed conservative measures, such as medical treatment, EBP or endovascular embolization.

Surgical technique

Surgeries were performed under general anesthesia with patients positioned prone on a radiolucent frame through a posterior approach. All surgeries utilized continuous intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM) of motor evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials. Careful attention was given to accurate localization using a lateral plain radiograph. In some cases, the Onyx from the embolization served as a radio-opaque marker. The surgical approach was chosen according to the level of the CSF leak and initiated through a midline incision. A second confirmation of the index level was performed at the subfascial juncture of the dissection with a second lateral radiograph. Subsequently, hemilaminotomy, laminotomy or laminectomy was performed under the microscope centered on the suspected site of CSF leakage using a 1.7-mm diamond matchstick burr. The use of a bone scalpel was introduced to perform the initial laminectomy in selected cases of laminoplasty.

Leaks lateral to the spinal cord (type 2) were addressed by an extradural approach and working from lateral to medial; only a partial foraminotomy was performed when necessary. Ventrally located CSF leaks (type 1) were repaired using a microscopic intradural direct suturing technique. This was carried out via a dorsal durotomy spanning one level above and below the index-level pathology. The edges of the dura were then tacked up with stitches on each side, and mobilization of the spinal cord was performed by dissecting 1–2 dentate ligaments bilaterally (spinal cord release maneuver), allowing for slight rotation and exposure of the ventral dura. Once the dural defect was identified, micro spurs penetrating the anterior dura were removed if present, a small autologous fat graft was placed ventral to the durotomy and posterior to the disc space and watertight closure of the ventral durotomy was achieved with a running 5-0 Nurolon suture. The dorsal durotomy was then closed using a running 5-0 Nurolon suture, and the closure was reinforced with fibrin glue and an autologous blood patch. The Valsalva maneuver was performed to confirm a watertight closure.

Instrumented fusion with pedicle screws was performed in patients in whom the laminectomy spanned the cervicothoracic junction or when a wide laminectomy with partial facetectomy was required, necessitating stabilization. In the mid-thoracic region, laminoplasties were performed, and small titanium mini-plates were used to secure the laminae back to their original position using four mini self-tapping screws per mini-plate, reducing the dead space and the risk of developing a postsurgical pseudo-meningocele. The incision was closed in layers over a subfascial drain without suction. All patients were mobilized on day one following the surgery.

For surgical repair of type 3 fistulas, we followed the technique previously described by Lokhamp et al. Reference Lohkamp, Marathe, Nicholson, Farb and Massicotte20 Briefly, this involves a minimally invasive surgical (MIS) approach with the use of a tubular retractor system docked over the level of CSV. After exposure of the lateral dura and nerve root complex, the fistulous connection was microsurgically disconnected after a period of temporary clipping using ligated titanium Yasargil aneurysm clips. IONM was conducted for 10 minutes to ensure no significant changes in the physiological function of the spinal cord before nerve root ligation. Closure then proceeded as described above but without placement of any drain.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The surgical outcome was assessed by clinical follow-up through scheduled outpatient visits. All patients had a minimum 3-month follow-up with postoperative clinical evaluation and a full spine and brain MRI. The primary outcome was change in presenting symptom, as reported by patients, categorized as either resolution (minimal or no symptoms), improvement (partial change) or persistent (no change or worsening). Secondary outcomes included headache relief, radiographic resolution of SLEC or cranial stigmata and postoperative complications.

Systematic review

A systematic literature review was conducted using PubMed, Ovid, MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Library from inception to 2024 following the PRISMA guidelines. Two independent authors (LL and KP) screened, selected and performed the data extraction. The search strategy incorporated combinations of the terms “CSF leak,” “Spinal,” “surgical repair,” “surgical treatment,” “spontaneous intracranial hypotension,” “cerebrospinal venous fistula,” “CVF” and “SIH.” Studies were included if they reported surgical outcome of spontaneous spinal CSF leaks in adult populations using direct open or MIS techniques. Exclusion criteria included conference abstracts, reviews, case reports, non-English literature, studies involving post-traumatic or postsurgical leaks and nonsurgical series that lack description of surgical interventions. Data extraction included patient demographics, surgical approaches, outcomes and reported complications.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical variables, including leak type, surgical procedure and postoperative complications, were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation (SD). All analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (version 4.2.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient population and surgical outcome

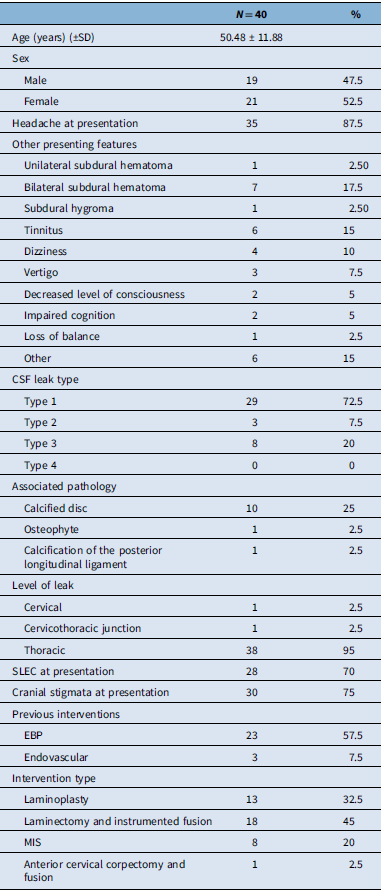

Between June 2017 and December 2023, a total of 40 patients underwent surgical repair of a primary spinal CSF leak at our center. The cohort included 21 females (52.5%) and 19 males (47.5%), with the mean age at surgery of 50.48 ± 11.88 years (range: 29–78 years). Most patients presented with symptoms persisting for at least 12 months, and the mean duration from symptom onset to surgery was 41 ± 55.44 months.

Orthostatic headache was the most commonly reported symptom (87.5%), followed by tinnitus (15%). Other presenting features include subdural hygroma (2.5%), unilateral (2.5%) and bilateral (17.5%) subdural hematoma(s) (2.5%) and dizziness (10%).

CSF leaks were classified radiographically as type 1 (ventral dural tear) in 72.5% of patients, type 3 (CVF) in 20% and type 2 (lateral dural tear) in 7.5%. No patient had type 4 leaks. The thoracic spine was the predominant location of CSF leak (95%).

Anatomical abnormalities identified on imaging included calcified disks in 10 of 40 patients (25%), posterior longitudinal ligament calcification in 1 patient and osteophytic changes in 1 patient. SLEC was observed in 70% of cases (n = 28), and cranial stigma of intracranial hypotension was noted in 75% (n = 30) (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of patient characteristics, including demographic information, clinical presentation, pathology and interventions

SLEC = spinal longitudinal epidural collection; EBP = epidural blood patch; MIS = minimally invasive surgery.

Prior to surgery, 57.5% (n = 23) of patients had received at least one epidural blood patch, and three patients (7.5%) underwent endovascular embolization. Surgical approaches included laminectomy with or without instrument fusion (45%, n = 18), laminoplasty (32.5%), minimally invasive surgery (20%) and anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion in one patient (2.5%).

Surgical outcomes and complications

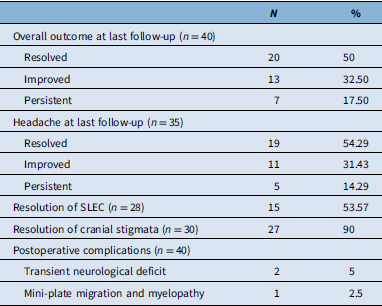

The average duration of postoperative follow-up was 19.54 (±15.46) months. At the most recent visit, complete symptom resolution was observed in 50% of patients (n = 20), while 32.5% (n = 13) experienced partial improvement. Seven patients (17.5%) reported persistent symptoms.

Among the 35 patients who initially presented with headache, 19 (54.3%) achieved complete resolution, and 11 (31.4%) noted improvement. Five patients (14.29%) experienced persistent headache.

Resolution of imaging findings was also observed. Of the 28 patients presenting with SLEC, 53.5% (n = 15) demonstrated complete resolution. Cranial stigmata of intracranial hypotension resolved in 90% (n = 27) of the 30 patients presenting with such findings.

The overall postoperative complication rate was low. Two patients (5%) developed transient neurological deficits. One of these cases occurred after ventral leak repair and was attributed to dentate ligament resection and cord mobilization, although full recovery occurred. One patient developed mild postoperative myelopathy related to mini-plate migration following a laminoplasty and subsequently underwent successful revision surgery (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of outcomes and complications among patients undergoing direct surgical repair of spinal CSF leak

SLEC = spinal longitudinal epidural collection.

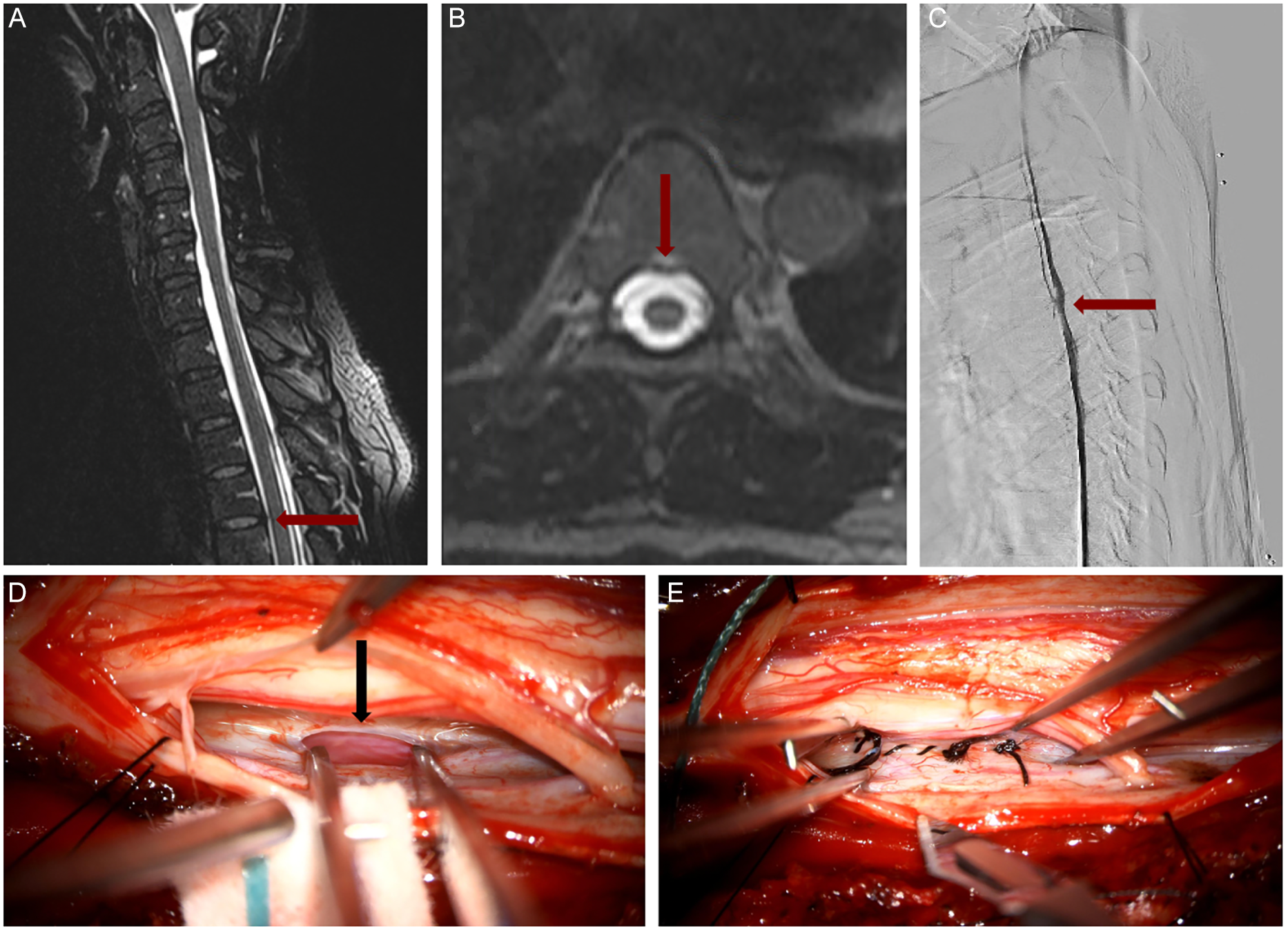

Illustrative Case (Figure 1 and Supplementary Video)

A 44-year-old previously healthy female presented with a 2-year history of isolated orthostatic headaches. She underwent an epidural blood patch (EBP) for a CSF leak at T4 in August 2018 and was symptom-free until September 2020, when she experienced a severe relapse of her headaches. Subsequently, she developed increasing neurological symptoms, requiring further treatment. Surgical direct CSF leak repair was performed in January 2021. MRI demonstrated a bone spur impacting the ventral dura at T4 (Figures 1A and 1B). DSM visualized the anterior CSF leak with contrast extravasation at the level of T4 (Figure 1C). Intraoperative photographs showed a 5 mm slit-like opening of the anterior dura (Figure 1D, black arrow) and its subsequent closure with a 5-0 Nurolon suture (Figure 1E) (Supplementary Video).

Figure 1. Open direct surgical repair of type 1 ventral dural CSF leak at T4 level. (A) MRI T2 sequence in sagittal plane, showing the bone spur red arrow (B) MRI T2 sequence in axial plane showing the same bone spur red arrow. (C) Corresponding dynamic myelogram with extravasation of contrast at the same level of the bone spur. (D) Intra-operative image of ventral defect with micro-instrument inside the dural breach black arrow. (E) Final primary closure with black interrupted sutures. The spinal cord is displaced to the top of the intra-operative image.

Systematic review of related literature

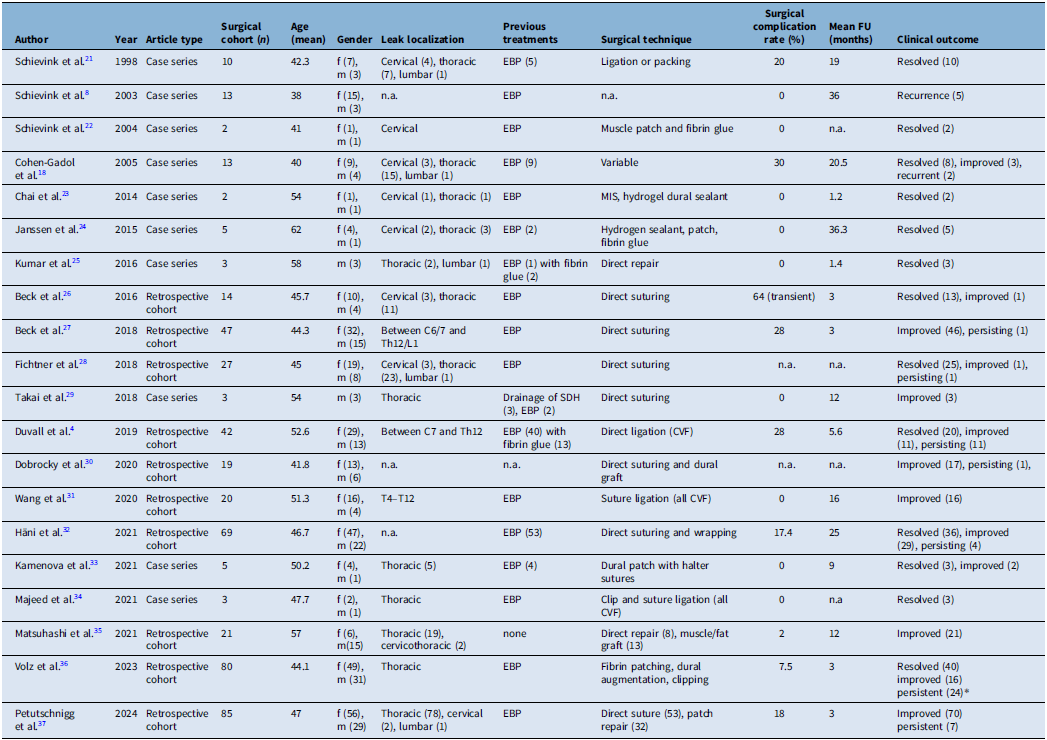

The literature search identified 444 articles from databases and 6 records via citation search. After duplicate removal, a total of 241 articles were screened for relevance of titles and abstracts. After exclusion of 166 records due to language (n = 1) and abstract content (n = 165), 75 reports were sought for retrieval. Three records were not available as full text and therefore not retrieved. Seventy-two articles were reviewed for eligibility and led to exclusion of 28 articles not matching the inclusion criteria and 25 articles due to the article type (reviews and case reports). A total of 20 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. These comprised 10 case series and 10 retrospective observational cohort studies published between April 1998 and December 2024 (Supplementary Fig. 1 PRISMA).

These studies collectively reported outcomes on 483 patients who underwent surgical intervention for spontaneous spinal CSF leaks. The mean age across cohorts was 44.3 years with female predominance (66.25%, n = 320). The mean follow-up duration across studies was 10.3 months (range: 1.2–36.3 months). The thoracic spine is the most frequently reported location, although cervical and lumbar leaks were also present.

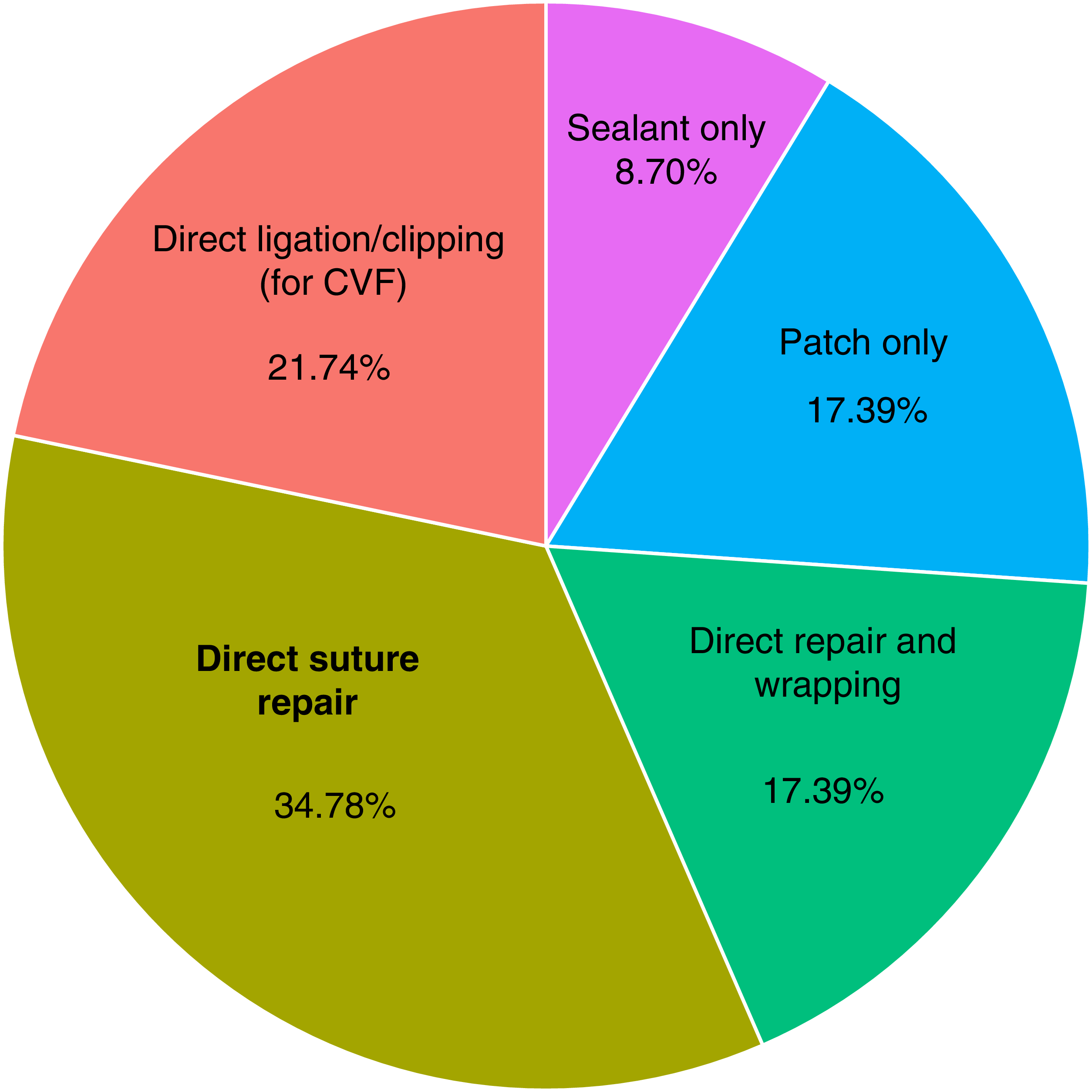

The most common preoperative intervention was EBP, with 18 out of 20 studies documenting failed EBP attempts prior to surgery. Surgical strategies varied: eight studies employed direct suturing, and six described patch-based methods including autologous muscle/fat grafts, fibrin glue or sealant use. Suture and clip ligation were also reported in five studies for CVF (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Surgical technique trends in reviewed studies of spontaneous spinal CSF leak management. CVF = CSF-venous fistula.

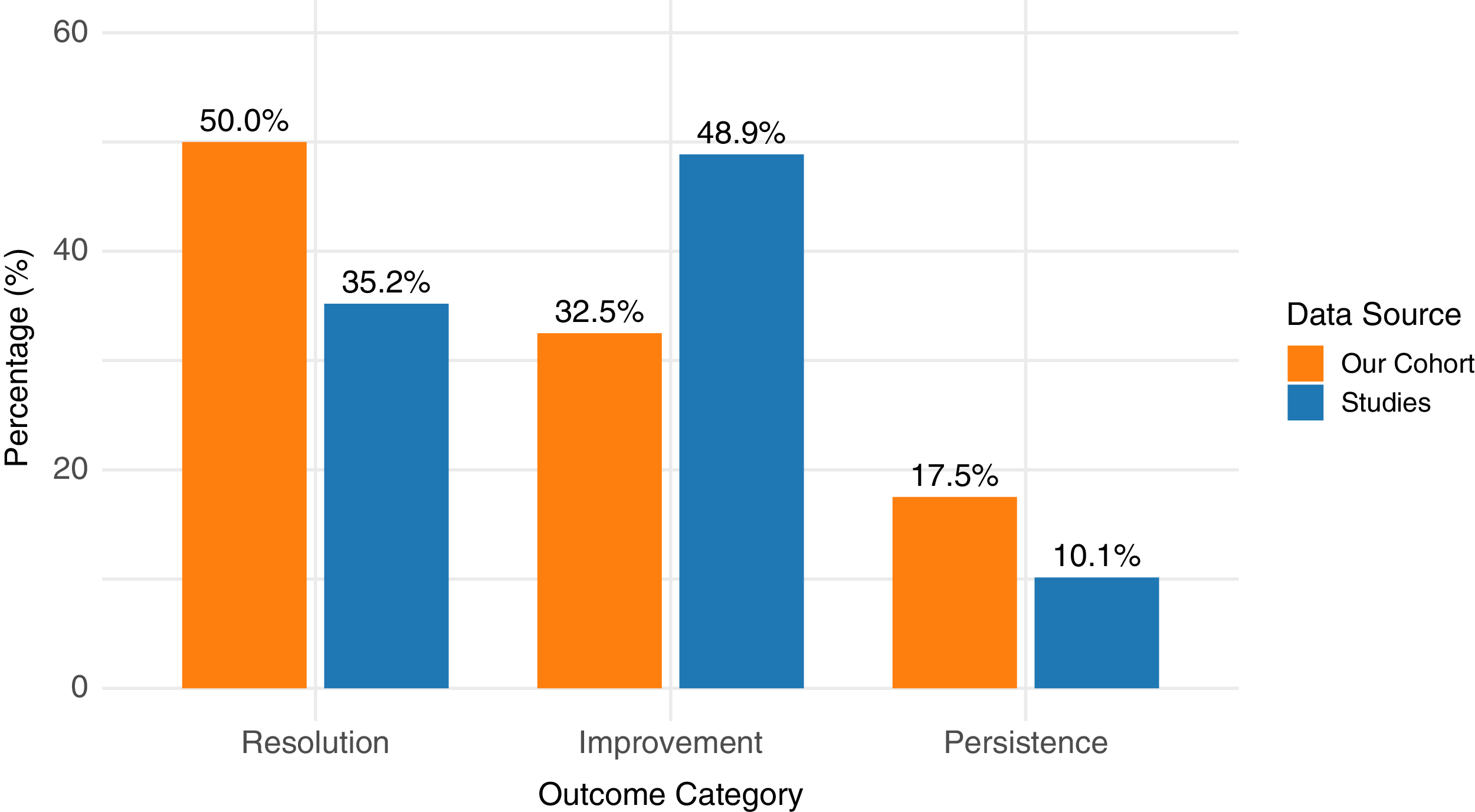

Clinical outcomes demonstrated high rates of postoperative improvement. Symptom improvement was documented in 236 patients (48.86%), with an additional 170 patients (35.20%) reporting complete resolution (Figure 3). A minority of patients (10.14%) experienced persistent or recurrent symptoms. Postoperative complications ranged from 0% to 64%, with the highest incidence noted in studies using direct repair techniques. The use of patches only was considered an indirect technique. However, the majority of complications were transient neurological deficits. No procedure-related mortality was reported (Table 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of postoperative outcomes between systematic review results and institutional cohort.

Table 3. Overview of the surgical techniques, complications and outcomes across 20 studies included in the systematic review

EBP = epidural blood patch; CVF = CSF-venous fistula; SDH = subdural hematoma; MIS = minimally invasive surgery.

Discussion

Our study presents a combined institutional case series and systematic review evaluating surgical outcomes for spontaneous spinal CSF leaks. Our results demonstrate that direct microsurgical suture repair offers favorable clinical outcomes and low complication rates, even in patients who had previously failed conservative treatment modalities such as EBP or endovascular embolization.

Within the surgical cohort, 57.5% of patients had previously undergone an EBP, while 7.5% received endovascular embolization prior to definitive surgical intervention. As our patient population represents a highly selected group, referred for surgery following multidisciplinary evaluation, the observed rates of prior EBP or embolization failure may not reflect broader clinical practice. Moreover, factors influencing EBP efficacy, including the type of CSF leak, volume of injected blood and proximity of the injection to the leak site, were not uniformly captured. Reference Montes, Pisani Petrucci, Bhaumik, Andonov, Lennarson and Callen38,Reference D’Antona, Jaime Merchan and Vassiliou39 Similarly, the success of endovascular embolization is contingent upon accurate leak localization and technical execution, details of which cannot be accurately ascertained in our dataset. These limitations highlight potential areas for future studies to better delineate predictors of procedural success and possibly refine patient selection for early surgical referral. Recent advances in imaging have introduced photon-counting CT, which directly converts X-rays into electrical signals, thereby improving spatial resolution and contrast-to-noise ratio compared to conventional CT. This technology may enhance the detection of subtle or elusive CSF leaks, particularly in patients with negative or inconclusive findings on standard myelography. Reference Madhavan, Cutsforth-Gregory and Brinjikji40

Surgical repair yielded favorable outcomes in our cohort, with 82.5% of patients demonstrating overall symptom improvement and 50% achieving complete resolution. Resolution or improvement in orthostatic headache was observed in 85.7% of patients, while radiographic resolution of SLEC and cranial stigmata was achieved in 53.5% and 90%, respectively. These outcomes compare well with those from the 20 studies included in our systematic review, with slightly higher rates of complete resolution in our cohort. Importantly, complication rates in our cohort were low, consisting only of transient neurological deficits or implant-related issues that were reversible with appropriate intervention. Similarly, the literature reported complication rates ranging from 0% to 64%, with most being nonpermanent and not associated with any long-term morbidity or mortality. These results reinforce the role of surgery, specifically with direct suture repair, as a definitive treatment option for spontaneous spinal CSF leaks, especially when conservative interventions fail. We previously described a related technique, the sling repair, in which an artificial dura or dural substitute is interposed between the dural defect and the spinal cord and secured with sutures. However, this approach is best suited for large dural defects or spinal cord herniations. Reference Massicotte, Montanera and Ross Fleming41

A notable observation in our series is the association between spinal CSF leaks and subdural hematomas (SDH). In our cohort, two patients presented with bilateral SDH and underwent hematoma evacuation following CSF leak repair. This sequence emphasizes the importance of recognizing that SDH in the context of SIH should not be managed in isolation. Rather, addressing and repairing the underlying spinal CSF leak is crucial, as untreated CSF hypotension may perpetuate downward brain displacement and venous traction, increasing the risk of SDH recurrence. Reference Beck, Gralla and Fung42 Thus, management should prioritize leak localization and repair before neurosurgical SDH evacuation in such cases.

Up to 15% of patients with SIH have underlying connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan’s syndrome or Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Reference Warsi, Farb and Kalia43 Careful preoperative assessment is essential, as these cases may represent ruptured dural ectasia, which is often not amenable to direct surgical repair due to intrinsically fragile dura. Imaging features suggestive of dural ectasia include thinning of the pedicles and lamina, widening of neural foramina and the presence of anterior meningocele, most commonly in the lumbosacral region. Reference Mokri, Maher and Sencakova44 In such cases, nonoperative strategies are generally preferred, as surgical closure carries a high risk of recurrence or failure.

Our institution’s experience also revealed technical considerations that may improve surgical outcomes. One patient who underwent laminoplasty at the cervicothoracic junction developed delayed postoperative myelopathy due to implant migration. This complication necessitated revision surgery and serves as a cautionary example. The cervicothoracic junction is subject to unique biomechanical stresses, especially in individuals with elevated body mass or altered spinal alignment. In such scenarios, rigid posterior stabilization with pedicle screw constructs may offer superior mechanical support compared to laminoplasty. These findings should thus serve to highlight the importance of customizing stabilization strategies based not only on anatomical location but also on patient-specific factors such as body habitus and bone quality.

One key strength of this study lies in the multidisciplinary diagnostic workup employed, including high-resolution MRI, digital subtraction myelography and CT imaging, which enabled precise localization of the CSF leak. The ability to differentiate between ventral, lateral and CVF-associated leaks allowed for tailored surgical approaches and likely contributed to the high success rates observed.

Several technical adaptations in our center may have additionally contributed to the favorable outcomes. The use of minimally invasive tubular techniques for CVF legation and avoidance of unnecessary fusion via laminoplasty in select cases further optimized outcomes while reducing surgical morbidity. Additionally, the consistent use of intraoperative neuromonitoring ensured further procedural safety.

This study has several limitations. The institutional retrospective cohort comprised a modest sample size and was derived from a single-surgeon experience at a tertiary academic center, potentially limiting generalizability. Although our mean follow-up duration (19.54 months) compares favorably with that reported in the literature, longer-term follow-up is needed to validate sustained efficacy. Furthermore, the accompanying systematic review qualitatively synthesized heterogeneous retrospective data with considerable variability in surgical technique, outcome reporting and follow-up intervals, precluding formal meta-analysis. Notably, no randomized controlled trials were identified; all included studies were case series or retrospective cohorts, which introduces inherent risk of bias. Nonetheless, this combined analysis provides crucial Canadian insights into the evolving surgical paradigms in SIH management.

Conclusion

Microsurgical direct suture repair represents an effective and safe strategy for the treatment of spontaneous spinal CSF leaks, with high rates of symptom resolution and low morbidity observed both in our institutional cohort and across the published literature. Careful patient selection, anatomical classification and operative planning, including consideration of biomechanics in fixation choices, are critical to optimizing outcomes. The management of SDH in the context of spinal CSF leak should prioritize leak repair to prevent recurrence. Future research should prioritize prospective multicenter trials and standardized reporting to establish an evidence-based algorithm for the diagnosis and management of spontaneous CSF leaks. Efforts are currently ongoing in both Canada and internationally.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10488.

Author contributions

EM: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; LL: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation; KP: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; FD : Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; PL: Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; JL: Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; NM: Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; NH: Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; PP: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; YH: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; EH: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; RF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.