1. Introduction

Grammatical categories such as verbs (e.g. to sing V) and nouns (e.g. a song N) are universally attested. Quite interestingly, nouns can be derived from verbs (e.g. a [[sing]V-er]N). This process is referred to as nominalization. Nominalizations have drawn interest since Lees (Reference Lees1960) due to their mixed display of verbal and nominal features (see also Chomsky Reference Chomsky1970). Building on prior syntactic work (Abney Reference Abney1987, Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2001, Harley & Noyer Reference Harley and Noyer1998, Marantz Reference Marantz1997, van Hout & Roeper Reference Van Hout and Roeper1998), I posit that deverbal nominalizations are derived from a nominal projection that includes some degree of verbal structure (Borsley & Kornfilt Reference Borsley and Kornfilt1999, Bruening Reference Bruening2018, Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1990, Kornfilt & Whitman Reference Kornfilt and Whitman2011, Wood Reference Wood2023, among others), as shown in (1):

Although debate continues over how much verbal structure such nominalizations can exhibit, it is widely accepted that this varies across languages and constructions. Notably, most research has focused on event nominalizations. In recent years, the structural variation in individual-denoting nominalizations has come to light (Baker & Vinokurova Reference Baker and Vinokurova2009, Fábregas Reference Fábregas2012, Gotah & Lee Reference Gotah and Lee2024, Hanink Reference Hanink2021, Harley Reference Harley2020, Lee & Ndapo Reference Lee and Ndapo2025, Ntelitheos Reference Ntelitheos2012, Roy & Soare Reference Roy and Soare2014, Reference Roy and Soare2020, Toosarvandani Reference Toosarvandani2014).

This work focuses on Gĩkũyũ (Bantu) nominalizations in which a verb is realized together with a noun class prefix and a suffix spelled out as either -i or -a:

Mugane (Reference Mugane1997) presents empirical facts from Gĩkũyũ nominalizations that cannot be readily handled under a traditional definition of syntax which assumes phrase-level constituents (see Alexiadou & Schäfer’s Reference Alexiadou and Schäfer2010 Phrasal Layering analysis):

Gĩkũyũ [mu-… -a]-type nominalizations are characterized as “phrases that are in the process of becoming lexicalized,” and “a lexicalization process involving phrases” (Mugane Reference Mugane1997: 127). Despite such characterizations, I present a syntactic approach to handling this type of nominalizations without resorting to the lexicon. Adopting Wood’s (Reference Wood2023) Complex Head analysis, which runs on the assumption that a complex head can be derived via External Merge (EM) without head movement, I show that Gĩkũyũ [mu-… -a]-type nominalizations need not rely on the inner workings of the lexicon.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the empirical puzzle surrounding the [mu-… -a]-type nominalizations. Section 3 provides how the Complex Head analysis (Wood Reference Wood2023) works and how it addresses the issue. Section 4 concludes.

2. Big and small nominalizations

2.1. Basic facts

Gĩkũyũ exhibits two types of nominalizations that differ with respect to their syntactic profile. The [mu-… -i]-type nominalizations permit various syntactic properties. The [mu-… -a]-type nominalizations, on the other hand, are quite limited with respect to what they can accommodate. The former is syntactically bigger than the latter. Hence, I refer to [mu-… -i]-type nominalizations as big nominalizations (BNs) and [mu-… -a]-type nominalizations as small nominalizations (SNs). (4) shows that an adverb can be realized inside BNs but not in SNs.

Additionally, an applied argument, together with its applicative marker -er, can be introduced in BNs but not in SNs:

Note that BNs can host a ditransitive predicate together with its internal arguments (IAs), unlike SNs:

BNs can also host the reflexive marker ĩ-, whereas SNs cannot:

Baker & Vinokurova (Reference Baker and Vinokurova2009) argue that the reflexive marker ĩ- in Gĩkũyũ has to be locally bound by an antecedent. They assume that the external argument (EA), PRO, is introduced in the derivation and that it is the antecedent that locally binds the object reflexive marker. It is difficult to make such a case for SNs where the reflexive marker cannot be introduced.

Due to the various discrepancies observed between BNs and SNs, Mugane (Reference Mugane1997) comes to the conclusion that SNs resemble lexical words.

2.2. The puzzle

Although BNs and SNs differ in various ways, they align in their ability to accommodate a phrasal theme argument (a theme DP). (8) demonstrates this point, which, in fact, complicates the picture sketched out in Section 2.1.

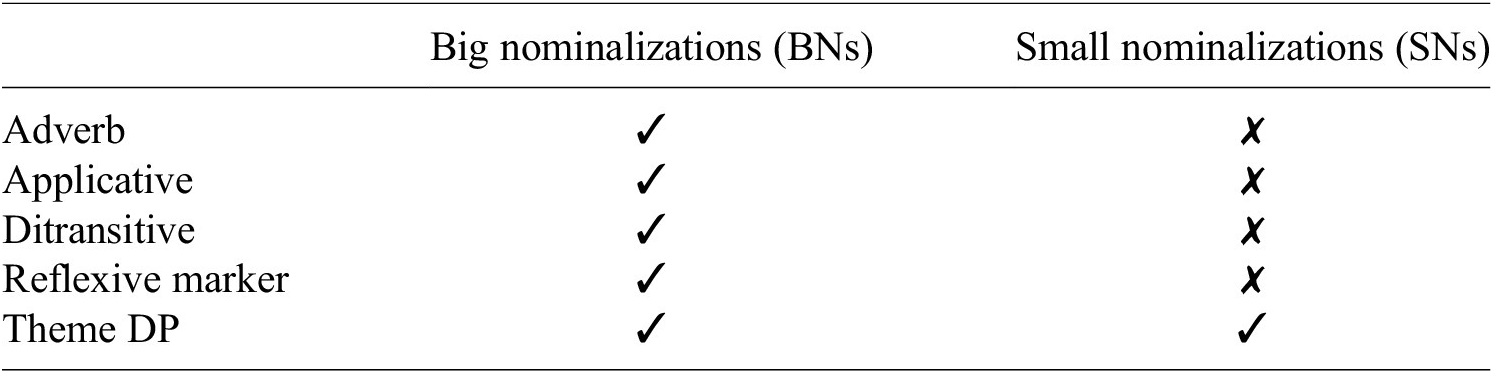

The well-formedness of (8b) puts Mugane in a position to argue that SNs are derived only when syntax comes into play. There is a dilemma here since SNs do not display any other syntactic properties that are otherwise expected from a run-of-the-mill verbal or clausal structure. Table 1 summarizes our findings so far.

Table 1. (Im)possible syntactic properties in big and small nominalizations

Mugane’s puzzle can be summarized as follows: how can something non-syntactic (e.g. an SN) accommodate something syntactic (e.g. a DP)? Also, how is the theme DP syntactically licensed in (8b) if syntactic operations do not apply SN-internally? In what follows, I address these questions.

3. Toward a solution

3.1. Phrasal Layering analysis

The Phrasal Layering analysis puts forward a unified approach to handling the clausal domain and the nominal domain. It works under the assumption that phrases such as vP, VoiceP, and Asp(ect)P can be realized inside noun phrases (Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2020, Alexiadou & Schäfer Reference Alexiadou and Schäfer2010, Hanink Reference Hanink2021, Harley Reference Harley2020, Ntelitheos Reference Ntelitheos2012).Footnote 1 While a unified approach to handling the two domains is theoretically desirable, the Phrasal Layering analysis is challenged by some important differences between the domains. The mismatch in Case distribution, for instance, sets the stage for the conundrum at play. It has been a long-standing puzzle why of-insertion is only observed in the nominal domain and not in the clausal domain (e.g. a reader *(of) many books vs. Mary reads (*of) many books) (see Chomsky Reference Chomsky1970, Harley & Noyer Reference Harley and Noyer1998, Lee Reference Soo-Hwan2024). Moreover, in most Indo-European languages, adverbs are readily available in the clausal domain (e.g. Halima reads books quickly.), while they are rarely observed inside individual-denoting nominalizations (e.g. *a reader of books quickly.). Analyses drawing parallels between the two domains have not been free from these issues.

3.2. Complex Head analysis

Taking into consideration the differences between the clausal domain and the nominal domain, Wood (Reference Wood2023) argues for a structure that does not involve phrase-level constituents inside nominalizations. This accounts for the presence of of-insertion and the absence of adverbs. Wood’s structure is similar to a complex head established via head movement. At the heart of Wood’s proposal is that complex heads need not rely on head movement. (9) schematizes Wood’s way of deriving a complex head. The structure is deprived of specifiers and adjuncts.Footnote 2 We will soon see that this small syntax approach applies to SNs but not BNs.

Note that (9) cannot accommodate an adverb, an applied argument, a ditransitive predicate with multiple IAs, or an EA internal to v that can locally bind a reflexive IA. All of these elements in syntax occupy a specifier or an adjunct position in the traditional sense. Because (9) rules out this possibility, we are able to correctly predict many of the empirical facts about SNs.

Now we are in a position to address how (9) fares with (8b). How do we reconcile the fact that a DP is realized together with something that appears to be non-phrasal? First, we need to discuss the different syntactic sites at which a theme DP can be introduced in Gĩkũyũ nominalizations. Examining the distribution of the associative marker will prove to be useful.

3.3. Associative marker

The associative marker (e.g. of) in Gĩkũyũ often appears inside noun phrases.

BNs can take an associative marker, and this is predictable. Bresnan & Mugane (Reference Bresnan and Mugane2006) assume that the associative marker can be introduced only after a verb turns into a noun. According to Bresnan & Mugane (Reference Bresnan and Mugane2006), the post-head demonstrative ũyũ safely marks the end of a verbal structure and the presence of the nominal syntax. Bresnan & Mugane (Reference Bresnan and Mugane2006) argue that any syntactic element following the demonstrative should be placed in the nominal domain and not in the verbal domain. In this respect, the realization of the associative marker in (11a) makes sense. Its absence in (11b) makes sense if we assume that the theme DP is introduced inside the verbal structure before the demonstrative comes into play.

Crucially, (11) suggests that a theme DP can be introduced at different syntactic sites. In (11a), the DP is introduced outside of the verbal structure. In (11b), the DP is introduced inside of the verbal structure. Hence, the height at which the DP is introduced is crucial under the current analysis.

3.4. An analysis based on nominal licensing

I adopt the widely held assumption that all overt DPs have to be licensed in syntax.Footnote 3 I take the associative marker in (11a) as a preposition (P) that licenses its complement DP in the nominal domain, as schematized in (12). Following Fuchs & van der Wal (Reference Fuchs and van der Wal2022), Kramer (Reference Kramer2015), Lee & Lee (Reference Lee and Lee2019), I argue that a stacked-n analysis applies to the Gĩkũyũ nominalizations under discussion. Specifically, I posit that a noun class prefix belongs to n, which is stacked above a lower n, namely the suffix -i (see Halpert & Hammerly Reference Halpert and Hammerly2025). In (12), movement captures the correct word order between the noun and the demonstrative.

A reviewer asks how agreement is achieved between the associative marker and the noun class prefix in (12). I adopt Clem’s (Reference Clem2023) probe-goal system. Her approach is based on Rezac’s (Reference Rezac2003) cyclic expansion analysis, which posits that probing can be done by an intermediate-level projection when the head fails to find an appropriate goal within its c-command domain. Clem argues that a maximal projection of X can also probe for a goal. Probing under this definition operates cyclically, and the search domain continues to expand whenever X and its kin(s) fail to find their goal. The expansion stops when X projects maximally (XP). Let us see how this works in (12). P is the probe and the upper n is the goal. P fails to probe the upper n since it is outside of P’s c-command domain.Footnote 4 On the second try, P’s maximal projection probes its c-command domain, and this time the domain includes the upper n associated with the noun class. Agreement is successful on this trial, and the associative marker ends up with the noun class agreement marker.

In cases where the associative marker is absent, the theme DP is introduced as the complement of the verb, and the DP is licensed inside the verbal structure. For present purposes, I assume that there is a higher functional head, call it X, that licenses the DP. Recall that the reflexive marker ĩ- can be showcased inside BNs, as seen in (7a). This suggests that an antecedent is present in the derivation. Adopting Baker & Vinokurova (Reference Baker and Vinokurova2009), I assume that PRO takes part in BNs’ derivation as an EA and acts as the antecedent for the reflexive marker ĩ-. For ease of exposition, I posit that the licensing of the theme DP is done in the style of Burzio’s Generalization (Burzio Reference Burzio1986)Footnote 5, though I remain open to alternative analyses. Note that the generalization is useful for cases where the direct object (DO) is present in the absence of a preposition. This is because the licensing of the DO can be done independently, as long as an EA is present in the derivation, as in (13).

I argue that SNs bear an associative marker. I posit that -a is the associative marker (P) that licenses a theme DP.Footnote 6 The PP led by -a here is sandwiched between the upper nP and the lower nP, as shown in (14). Since the PP participates in the derivation prior to the introduction of the upper n (noun class 1), the noun class agreement marker, w-, which would have otherwise appeared, does not show up. This suggests that an interpretable noun class feature-bearing goal (n) does not undergo agreement with its probe when the former c-commands the latter. In fact, this aligns with the idea that upward agreement is not desirable (see Carstens Reference Carstens2005, Chomsky Reference Chomsky2000, Reference Chomsky2001, Preminger Reference Preminger2014). I also take the view that agreement can fail without causing a crash in the derivation (Preminger Reference Preminger2014). As opposed to the verbal profile of a BN, the verbal profile of an SN lacks the necessary functional material to license a theme DP. This is well in line with the fact that a theme DP requires -a inside SNs. Here, I posit that there are two types of lower ns. One of them selects a phrase-level constituent (XP) and the other a head-level element (X0). The assumption is not far-fetched if we think about the distinct phonological realization of the two ns. The lower n in SNs is spelled out as a zero form (i.e. ø) instead of -i because it selects a head instead of a phrase. The suffix -i, on the other hand, selects a phrase instead of a head. This pattern can be accommodated using a Distributed Morphology-style framework (see Halle & Marantz Reference Halle and Marantz1993). The derivation for the SN in (2b) is fleshed out in (14).

Under close inspection, both BNs and SNs can be accounted for in syntax. Let us return to Table 1. We see that all of the verbal properties showcased in BNs are expected from phrase-level syntax (XP). Adverbs adjoin to an XP. Applicatives, ditransitives, and reflexives need Spec,XP in order to accommodate an extra argument (e.g. an applied argument or an antecedent DP). A theme DP in a BN can be licensed in the same way that it can be licensed in an XP containing verbal structure. The Complex Head analysis coupled with the licensing of the theme DP using an associative marker offers a way of handling SNs. The absence of an XP rules out adverbs. There certainly is no Spec,XP to secure enough room for applicatives, ditransitives, and reflexives. A theme DP has to be licensed in a fashion different from the one in an ordinary XP containing verbal structure.

4. Conclusion

Mugane (Reference Mugane1997) presents two types of nominalizations in Gĩkũyũ: BNs and SNs. Mugane argues that the SNs resort to the lexicon and its inner workings prior to syntactic operations. I have highlighted that we can handle this issue without resorting to the lexicon. By making use of Wood’s (Reference Wood2023) small syntax approach, I have argued that the facts about SNs can be captured simply by employing syntactic apparatuses. In doing so, the derivation is done within a single workspace. The approach advocated in this work also has cross-linguistic and cross-phenomenal implications. It adds weight to the recent growing body of literature on the Complex Head analysis, which has been applied for Icelandic and German nominalizations (Benz Reference Benz2025, Wood Reference Wood2023) and English and Greek stative passives (Biggs & Embick Reference Biggs and Embick2025, Embick Reference Embick2023, Paparounas Reference Paparounas2023). Hopefully, future research will shed further light on the exact profile of small syntax and its theoretical implications.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Alec Marantz, Alex Hamo, Chris Collins, Claire Halpert, Dave Embick, Eva Neu, Gary Thoms, Jim Wood, Johanna Benz, Julie Legate, Lefteris Paparounas, Mark Baker, Marlyse Baptista, Matt Hewett, Mike Barrie, Milena Šereikaitė, Richie Kayne, Seunghun Lee, Stephanie Harves, Yining Nie, and the audiences at LSA 2025, NYU Syntax Brown Bag, and Sogang University. I would also like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the New Faculty Research Support Grant from Gyeongsang National University in 2025, GNU-NFRSG-0001.