Introduction

Radar sensors are considered a key element of a modern advanced driver assistance system (ADAS), enabling comfort- and safety-related driving features [Reference Rasshofer and Gresser1, Reference Gerstmair, Melzer, Onic and Huemer2]. Their advancement in terms of cost-effectiveness is expected to result in an increasing amount of radar sensors on the road. However, their widespread deployment also implies a rising probability of mutual interference between radar sensors. This is particularly the case for radar sensors mounted to different vehicles [Reference Kunert3], as exemplified in fig. 1(a). Such interference may severely degrade radar system performance, including the introduction of ghost targets or even missing targets [Reference Kim, Mun and Lee4]. Therefore, a variety of potential countermeasures have been developed over the past [Reference Toth, Meissner, Melzer and Witrisal5], which often belong to the categories of detect-and-mitigate or detect-and-avoid [Reference Umehira, Okuda, Wang, Takeda and Kuroda6, Reference Bechter, Sippel and Waldschmidt7]. Moreover, since many of the currently operating automotive radar sensors use the frequency-modulated continuous-wave (FMCW) principle [Reference Patole, Torlak, Wang and Ali8], so are the countermeasures often tailored to handle interference between FMCW radar sensors.

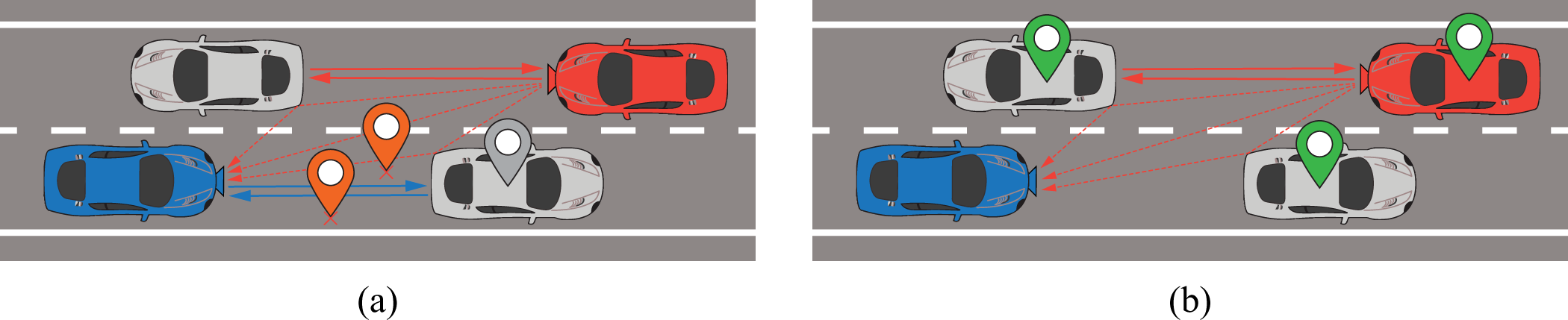

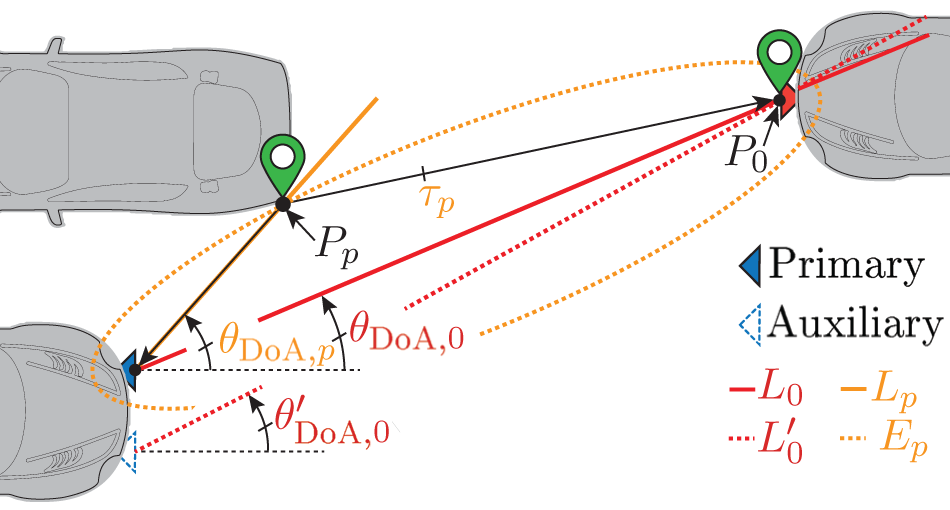

Figure 1. An exemplary traffic scenario in which the blue car receives interfering radar signals originating from the red car. The signals may travel via multiple signal propagation paths, either direct and/or indirect. (a) Without countermeasures: Degradation of radar performance. Targets may be missed and ghost targets may occur. (b) Detect-and-exploit countermeasure: Passive localization of interferer and surrounding objects using interfering signals.

An alternative viewpoint on interference that has not yet received much attention is detect-and-exploit, which makes use of interfering signals to obtain information about the environment. From an ADAS point of view, in particular the localization of the interferer and surrounding objects that create indirect signal paths could be of special interest, as illustrated in fig. 1(b). In other works, it has already been shown that processing such non-line-of-sight (NLOS) signals allows detection and localization of objects such as occluded road users using active automotive radar sensors [Reference Zhaoyu, Wenli, Jingyue, Shisheng, Guolong, Lingjiang and Kun9, Reference Scheiner, Kraus, Wei, Phan, Mannan, Appenrodt, Ritter, Dickmann, Dietmayer, Sick and Heide10]. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, successful localization of objects using interfering automotive FMCW radar signals has not yet been demonstrated and will be treated in this work.

In order to provide such exploitation functionalities, principles known from passive radar can be employed, since the interferer can be treated as an illuminator of opportunity (IoO) [Reference Griffiths and Baker11]. In fact, passive automotive radar has already been in the focus of research at times. For example, in [Reference Moussa and Liu12], the general feasibility of passive automotive radar using 5G roadside units as IoOs was investigated. Furthermore, in [Reference Blasone, Colone and Lombardo13] the potential of different IoOs such as 5G and DVB-S was considered to solve the problem of mutual interference. However, these approaches not only require additional hardware, but also do not exploit but instead avoid interfering automotive FMCW signals. In order to truly enable exploitation, it is necessary to find a way to obtain usable intermediate frequency (IF) signals that can be assigned to a reference and surveillance channel within the general passive radar framework. To this end, a series of key challenges will be addressed in the following.

(1) By its definition, a passive radar does not emit any electromagnetic (EM) signals, whereas an automotive radar usually transmits actively. However, in this mode of operation, the interfering signals will be superimposed by the active radar response upon reception. Therefore, in this work, a dedicated passive sensing mode in which all transmit (TX) channels are turned off will be considered. This mode can be invoked as soon as an interferer has been detected and maintained during its presence. For the detection of FMCW interference, we refer to state-of-the-art solutions such as a power detector or a generalized likelihood ratio test (GLRT)-based detector [Reference De Oliveira and Backx14].

(2) In order to capture the signals stemming from an IoO, a straightforward solution would be to use a receiver that can cover the whole frequency band of interest in terms of bandwidth. However, in an automotive FMCW radar sensor, the IF bandwidth of the receiver is typically much smaller than the radio frequency (RF) bandwidth. Moreover, since the local oscillator (LO) signal of the non-cooperative interferer is not available at the interfered vehicle, an alternative choice for the LO is required for down-conversion. One way to ensure that the captured IF signal yields exploitable components is to linearly sweep the LO signal across the whole RF band of interest. This mode of operation, which was originally proposed for passive spectral sensing [Reference Gardill, Schwendner and Fuchs15], can further serve as an enabler for over-the-air synchronization (OTAS) [Reference Gardill, Schwendner and Fuchs16] onto the interfering waveform. Since in practice OTAS is often challenged by radar sensors with temporally varying ramp parameters and/or time frequency dithering, in this work, an exploitation method requiring only linear frequency sweeps without OTAS will be presented. This not only greatly extends its practical applicability, but also allows to passively monitor the chirp sequence of an interferer as an additional side feature.

(3) Passive radar signal processing typically makes use of a reference channel and a surveillance channel. However, these channels are not directly available, but only their superposition. In this work, the required separation will be achieved in the spatial domain using multiple receive (RX) channels of an antenna array, which is typically available in an automotive radar sensor. To this end, a processing step based on established direction of arrival (DoA) estimation and beam steering methods will be incorporated.

(4) Cost-efficient automotive radar sensors often avoid I/Q receivers, which introduces a spectral ambiguity for every signal component. In order to resolve these ambiguities, a pre-processing step based on the Hilbert transform and phase inversion, similar to [Reference Bechter, Biswas and Waldschmidt17], will be proposed in this work.

Once reference and surveillance channels are available, the standard procedure for passive radar signal processing suggests computing a cross ambiguity function (CAF) to evaluate bistatic range and Doppler information. However, for the problem at hand, two points need to be considered in this regard. Firstly, Doppler frequency shifts are typically negligible compared to range-induced frequency shifts in a fast-chirp FMCW radar. Therefore, bistatic velocity evaluation using the CAF is considered not meaningful in this context, and will consequently not be incorporated. Secondly, the linearly sweeping LO causes the individual signal components of the IF signals to be of chirp-like shape with low sub-sample time delays between them. It could consequently appear reasonable to evaluate the correlation operation of the CAF in the frequency domain rather than in the time domain. In contrast to the fast Fourier transform (FFT) used in active FMCW radar, a suitable transformation is now given by the fractional Fourier transform (FrFT) since the IF signals are chirps rather than single-tone frequencies. For a chirp signal embedded in white Gaussian noise, the FrFT is in fact even the optimum transformation in a maximum likelihood (ML) sense [Reference Aldimashki and Serbes18]. However, due to the limited IF bandwidth, the chirp signal is subject to additional windowing, which is not part of the FrFT signal model in the first place. Therefore, an adapted FrFT-inspired estimation method is elaborated in this work that takes this windowing effect into account.

As will be shown, the resulting estimate encodes a time-frequency sample of the interfering waveform, covering the aspect of passive spectral sensing. Additionally, the estimates from different signal paths represent a time difference of arrival (TDoA) information that, together with the DoA estimates, enables joint DoA-TDoA-based localization of surrounding objects [Reference Hua, Hsu and Liu19]. Importantly, to map the TDoA quantity to a corresponding iso-range ellipse necessary for localization, the position of the interferer has to be determined beforehand. To this end, a simple triangulation-based solution using DoA information from a second auxiliary radar sensor mounted on the same vehicle will be presented.

In order to assess the applicability of the proposed method, a dedicated section on theoretical analysis will be provided, covering aspects such as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of an interferer, the minimum required SNR, the DoA-TDoA-based localization accuracy as well as the computational complexity and execution time. Finally, measurement results recorded in an anechoic chamber will be presented, confirming the feasibility of the proposed concept.

A part of this work with an initial measurement-based verification was presented at the European Radar Conference 2024 and published in [Reference Rienessl, Gerstmair, Schmid, Stelzer and Feger20].

Signal model

In this section, the signal model that will be used throughout this work will be derived. Importantly, a single LO ramp will be considered as a starting point, where the handling of multiple consecutive LO ramps will be explained later in this work. Moreover, we will start with a complex-valued signal model and will later introduce a pre-processing step in order to deal with cases in which no I/Q receiver is available.

We denote the (automotive) frequency band under consideration as ![]() ${[f_{\textrm{min}}, f_{\textrm{max}}]}$ and assume a single interfering FMCW radar sensor with frequency course

${[f_{\textrm{min}}, f_{\textrm{max}}]}$ and assume a single interfering FMCW radar sensor with frequency course ![]() $f_{\textrm{TX}}(t)$ present in the scene, where

$f_{\textrm{TX}}(t)$ present in the scene, where ![]() ${f_{\textrm{min}} \lt f_{\textrm{TX}}(t) \lt f_{\textrm{max}}}$. It is assumed that this signal reaches the passive radar sensor via a direct signal path after a delay of

${f_{\textrm{min}} \lt f_{\textrm{TX}}(t) \lt f_{\textrm{max}}}$. It is assumed that this signal reaches the passive radar sensor via a direct signal path after a delay of ![]() $\tau_{0}$ as well as via

$\tau_{0}$ as well as via ![]() $P \ge 0$ indirect signal paths after the delays

$P \ge 0$ indirect signal paths after the delays ![]() $\tau_{1}, \ldots , \tau_{P}$. Without loss of generality, the index order is defined such that

$\tau_{1}, \ldots , \tau_{P}$. Without loss of generality, the index order is defined such that ![]() ${\tau_{0} \lt \tau_{1} \lt \ldots \lt \tau_{P}}$ holds. Furthermore, as Doppler shifts are considered negligible, the received frequency course from the

${\tau_{0} \lt \tau_{1} \lt \ldots \lt \tau_{P}}$ holds. Furthermore, as Doppler shifts are considered negligible, the received frequency course from the ![]() $p$th signal path can be expressed as

$p$th signal path can be expressed as

with ![]() ${p\in\{0, 1, \ldots , P\}}$. Moreover, the LO of the passive radar system is configured to linearly sweep over the whole frequency band of interest, i.e., its starting frequency

${p\in\{0, 1, \ldots , P\}}$. Moreover, the LO of the passive radar system is configured to linearly sweep over the whole frequency band of interest, i.e., its starting frequency ![]() $f_{\textrm{LO0}}$ and stopping frequency

$f_{\textrm{LO0}}$ and stopping frequency ![]() $f_{\textrm{LO1}}$ are set to

$f_{\textrm{LO1}}$ are set to ![]() $f_{\textrm{min}}$ and

$f_{\textrm{min}}$ and ![]() $f_{\textrm{max}}$, respectively. Also, a certain (short) sweep duration denoted as

$f_{\textrm{max}}$, respectively. Also, a certain (short) sweep duration denoted as ![]() $T_{\textrm{LO}}$ is set, such that its frequency course

$T_{\textrm{LO}}$ is set, such that its frequency course ![]() $f_{\textrm{LO}}(t)$ is given by

$f_{\textrm{LO}}(t)$ is given by

for ![]() $t \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$, where

$t \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$, where ![]() ${k_{\textrm{LO}} = (f_{\textrm{LO1}} - f_{\textrm{LO0}})/ T_{\textrm{LO}}}$ is the ramp slope.

${k_{\textrm{LO}} = (f_{\textrm{LO1}} - f_{\textrm{LO0}})/ T_{\textrm{LO}}}$ is the ramp slope.

Next we assume that ![]() $f_{\textrm{TX}}(t)$ can be equally expressed as

$f_{\textrm{TX}}(t)$ can be equally expressed as ![]() ${f_{\textrm{TX}}(t) = f_{\textrm{TX0}} + k_{\textrm{TX}} t}$ for

${f_{\textrm{TX}}(t) = f_{\textrm{TX0}} + k_{\textrm{TX}} t}$ for ![]() $t \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$, with an initial frequency

$t \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$, with an initial frequency ![]() ${f_{\textrm{TX0}}}$ and a ramp slope

${f_{\textrm{TX0}}}$ and a ramp slope ![]() $k_{\textrm{TX}}$, where

$k_{\textrm{TX}}$, where ![]() $|k_{\textrm{TX}}| \lt |k_{\textrm{LO}}|$ holds due to the assumptions. According to (1), this yields for the received frequency courses

$|k_{\textrm{TX}}| \lt |k_{\textrm{LO}}|$ holds due to the assumptions. According to (1), this yields for the received frequency courses

where

holds for one ![]() $t_{\textrm{X,}p} \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$, which is given by

$t_{\textrm{X,}p} \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$, which is given by

\begin{equation}

t_{\textrm{X,}p} = \frac{f_{\textrm{LO0}} - f_{\textrm{RX0,}p} }{k_{\textrm{RX}} - k_{\textrm{LO}}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

t_{\textrm{X,}p} = \frac{f_{\textrm{LO0}} - f_{\textrm{RX0,}p} }{k_{\textrm{RX}} - k_{\textrm{LO}}}.

\end{equation}An example of the previous conditions is shown in fig. 2(a).

Figure 2. An exemplary scenario with interfering FMCW signals captured by a passive radar sensor. (a) Frequency-over-time domain. The LO is configured to perform a (short) sweep over the whole frequency band of interest, allowing to exploit the received signal components stemming from the interferer. Here, ![]() $k_{\textrm{LO}} \gt 0$ and

$k_{\textrm{LO}} \gt 0$ and ![]() $k_{\textrm{RX}} \gt 0$ was used, yielding

$k_{\textrm{RX}} \gt 0$ was used, yielding ![]() $t_{\textrm{X,}0} \gt t_{\textrm{X,}1} \gt \ldots \gt t_{\textrm{X,}P}$. (b) Spatial-angular domain. Multiple EM waves representing the individual signal components impinge onto the antenna array under different DoAs. Every received signal is downconverted by the same commonly generated LO signal.

$t_{\textrm{X,}0} \gt t_{\textrm{X,}1} \gt \ldots \gt t_{\textrm{X,}P}$. (b) Spatial-angular domain. Multiple EM waves representing the individual signal components impinge onto the antenna array under different DoAs. Every received signal is downconverted by the same commonly generated LO signal.

Furthermore, the passive radar sensor is assumed to consist of ![]() $L$ receiving channels of an antenna array, enumerated by

$L$ receiving channels of an antenna array, enumerated by ![]() ${l\in\{0, 1, \ldots , L-1\}}$. In the following, a uniform linear array (ULA) with

${l\in\{0, 1, \ldots , L-1\}}$. In the following, a uniform linear array (ULA) with ![]() $\lambda/2$ element spacing is considered,

$\lambda/2$ element spacing is considered, ![]() $\lambda$ being the free space wavelength corresponding to the center frequency of the monitored frequency band. In addition, the EM wave corresponding to the

$\lambda$ being the free space wavelength corresponding to the center frequency of the monitored frequency band. In addition, the EM wave corresponding to the ![]() $p$th signal path impinges on the antenna array under the angle

$p$th signal path impinges on the antenna array under the angle ![]() $\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}p}$ with respect to antenna boresight. These conditions are exemplified in fig. 2(b).

$\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}p}$ with respect to antenna boresight. These conditions are exemplified in fig. 2(b).

Due to the previous considerations, the LO signal for ![]() $t \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$ can now be expressed as

$t \in [0, T_{\textrm{LO}}]$ can now be expressed as

with a signal amplitude ![]() $A_{\textrm{LO}}$ and initial phase

$A_{\textrm{LO}}$ and initial phase ![]() $\varphi_{\textrm{LO0}}$. Furthermore, the received signal at the

$\varphi_{\textrm{LO0}}$. Furthermore, the received signal at the ![]() $l$th channel is given by

$l$th channel is given by

\begin{equation}

s_{\textrm{CH,}l}(t) = \sum_{p=0}^{P} A_{\textrm{RX,}p} {\rm e}^{{\rm j}(2\pi f_{\textrm{RX0,}p} t + \pi k_{\textrm{RX}} t^2 + \varphi_{\textrm{RX0,}p} + \pi l u_p) },

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

s_{\textrm{CH,}l}(t) = \sum_{p=0}^{P} A_{\textrm{RX,}p} {\rm e}^{{\rm j}(2\pi f_{\textrm{RX0,}p} t + \pi k_{\textrm{RX}} t^2 + \varphi_{\textrm{RX0,}p} + \pi l u_p) },

\end{equation} where ![]() $A_{\textrm{RX,}p}$ and

$A_{\textrm{RX,}p}$ and ![]() $\varphi_{\textrm{RX0,}p}$ are signal amplitude and initial phase term of the

$\varphi_{\textrm{RX0,}p}$ are signal amplitude and initial phase term of the ![]() $p$th signal path, respectively, and

$p$th signal path, respectively, and ![]() $u_p = \sin\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}p}$. After downconverting each channel with the common LO signal, the resulting

$u_p = \sin\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}p}$. After downconverting each channel with the common LO signal, the resulting ![]() $l$th IF signal after the mixer (assuming unity gain) can be written as

$l$th IF signal after the mixer (assuming unity gain) can be written as

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\tilde{s}_{\textrm{IF,}l}(t) = \sum_{p=0}^{P} \underbrace{A_{\textrm{IF,}p} {\rm e}^{{\rm j}(2 \pi f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} t + \pi k_{\textrm{IF}} t^2 + \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}p} + \pi l u_p)} }_{ \tilde{s}_{\textrm{IF,}l,p}(t) },

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\tilde{s}_{\textrm{IF,}l}(t) = \sum_{p=0}^{P} \underbrace{A_{\textrm{IF,}p} {\rm e}^{{\rm j}(2 \pi f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} t + \pi k_{\textrm{IF}} t^2 + \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}p} + \pi l u_p)} }_{ \tilde{s}_{\textrm{IF,}l,p}(t) },

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}with

\begin{equation}

s_{\textrm{IF,}l}(t) =

\sum_{p=0}^{P} {\tilde{s}}_{\textrm{IF,}l,p}(t) \mathrm{rect} \left( \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}} t + f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} }{2 B_{\textrm{IF}} } \right) .

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

s_{\textrm{IF,}l}(t) =

\sum_{p=0}^{P} {\tilde{s}}_{\textrm{IF,}l,p}(t) \mathrm{rect} \left( \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}} t + f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} }{2 B_{\textrm{IF}} } \right) .

\end{equation} Finally, adding a noise term ![]() $w_{\textrm{IF,}l}(t)$ that is assumed to originate from a circular symmetric white Gaussian random process results in

$w_{\textrm{IF,}l}(t)$ that is assumed to originate from a circular symmetric white Gaussian random process results in

This signal is digitized by the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) at a sampling rate ![]() ${f_\textrm{s}}$, which for automotive radars is usually in the MHz range and is assumed to satisfy

${f_\textrm{s}}$, which for automotive radars is usually in the MHz range and is assumed to satisfy ![]() $f_\textrm{s} \gt 2 B_{\textrm{IF}}$ to prevent aliasing effects. After obtaining

$f_\textrm{s} \gt 2 B_{\textrm{IF}}$ to prevent aliasing effects. After obtaining ![]() ${ N= \lfloor T_{\textrm{LO}} f_\textrm{s} \rfloor }$ time domain samples and combining the resulting signals for all

${ N= \lfloor T_{\textrm{LO}} f_\textrm{s} \rfloor }$ time domain samples and combining the resulting signals for all ![]() $L$ channels into a matrix

$L$ channels into a matrix ![]() ${\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}} \in \mathbb{C}^{N \times L}}$, the resulting signal model using the fast time index

${\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}} \in \mathbb{C}^{N \times L}}$, the resulting signal model using the fast time index ![]() $n \in \{0, 1, \ldots , N-1\}$ can be expressed as

$n \in \{0, 1, \ldots , N-1\}$ can be expressed as

with

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{R}_{\textrm{FT}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{n,p} = \mathrm{rect} \left( \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}} n + f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} f_\textrm{s} } {2 B_{\textrm{IF}} f_\textrm{s} } \right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{R}_{\textrm{FT}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{n,p} = \mathrm{rect} \left( \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}} n + f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} f_\textrm{s} } {2 B_{\textrm{IF}} f_\textrm{s} } \right),

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

[\mathbf{H}_{\textrm{FT}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{n,p} = {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\left(2 \pi \frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}}{f_\textrm{s}} n + \pi \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}}}{f_\textrm{s}^2} n^2 \right)},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{H}_{\textrm{FT}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{n,p} = {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\left(2 \pi \frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}}{f_\textrm{s}} n + \pi \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}}}{f_\textrm{s}^2} n^2 \right)},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

[\mathbf{H}_{\textrm{AF}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{p,l} = {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \pi l u_p},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{H}_{\textrm{AF}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{p,l} = {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \pi l u_p},

\end{equation} where ![]() $\sigma^2$ is the variance of the complex-valued noise and

$\sigma^2$ is the variance of the complex-valued noise and

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\theta} =

[&f_{\textrm{IF0,}0}, \ldots , f_{\textrm{IF0,}P}, k_{\textrm{IF}}, A_{\textrm{IF,}0}, \ldots , A_{\textrm{IF,}P}, \\

& \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}0}, \ldots , \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}P}, u_0, \ldots , u_P, \sigma^2]^{\rm T},

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\theta} =

[&f_{\textrm{IF0,}0}, \ldots , f_{\textrm{IF0,}P}, k_{\textrm{IF}}, A_{\textrm{IF,}0}, \ldots , A_{\textrm{IF,}P}, \\

& \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}0}, \ldots , \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}P}, u_0, \ldots , u_P, \sigma^2]^{\rm T},

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} represents the vector of unknowns, which will be the focus of the signal processing steps in the next section. Notably, due to the lowpass, the amount of time-domain samples is effectively reduced to ![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}} = \textrm{min}(N, \lfloor 2 B_{\textrm{IF}} f_\textrm{s} / |k_{\textrm{IF}}| \rfloor) \le N$ usable samples for the proposed mode of operation, where edge cases are not considered. The lowpass also defines an effective bandwidth

$N_{\textrm{IF}} = \textrm{min}(N, \lfloor 2 B_{\textrm{IF}} f_\textrm{s} / |k_{\textrm{IF}}| \rfloor) \le N$ usable samples for the proposed mode of operation, where edge cases are not considered. The lowpass also defines an effective bandwidth

\begin{equation}

B_{\textrm{eff}} = \min \left( \left| T_{\textrm{LO}} k_{\textrm{RX}} \right|, \left| \frac{2 B_{\textrm{IF}} k_{\textrm{RX}}}{k_{\textrm{LO}} {-} k_{\textrm{RX}}} \right| \right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

B_{\textrm{eff}} = \min \left( \left| T_{\textrm{LO}} k_{\textrm{RX}} \right|, \left| \frac{2 B_{\textrm{IF}} k_{\textrm{RX}}}{k_{\textrm{LO}} {-} k_{\textrm{RX}}} \right| \right),

\end{equation} which will become relevant later when analyzing the accuracy of the object localization. At this point, it is only required that ![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}}$ is sufficiently large such that the subsequent signal processing steps can be performed.

$N_{\textrm{IF}}$ is sufficiently large such that the subsequent signal processing steps can be performed.

Signal processing

Pre-processing

As already mentioned, many state-of-the-art automotive FMCW radar sensors do not feature an I/Q receiver. Therefore, the spectral components of the real-valued IF signals occur pairwise, one of which is the actual physically relevant component. Consequently, in the following, a pre-processing step that removes the ambiguous signal component is presented, with the intention of ensuring approximate compliance with (11).

The received real-valued IF signals can be modeled by ![]() $\check{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}} = \textrm{Re}(\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}})$. First, applying a time-domain Hilbert transform

$\check{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}} = \textrm{Re}(\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}})$. First, applying a time-domain Hilbert transform ![]() $\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}} = \mathcal{H}(\check{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}})$ removes the negative spectral components. Next, a (coarse) estimate

$\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}} = \mathcal{H}(\check{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}})$ removes the negative spectral components. Next, a (coarse) estimate ![]() $\hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim}$ for the intersection points

$\hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim}$ for the intersection points ![]() $t_{\textrm{X,}p}$ is obtained by computing

$t_{\textrm{X,}p}$ is obtained by computing

\begin{equation}

\hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} = \frac{1}{L f_\textrm{s}} \sum_{l=0}^{L-1} \frac{\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} n|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}|^2}{\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} |[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}|^2},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} = \frac{1}{L f_\textrm{s}} \sum_{l=0}^{L-1} \frac{\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} n|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}|^2}{\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} |[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}|^2},

\end{equation}which corresponds to the center of mass of the instantaneous signal powers, averaged over all antenna channels. Finally, a selective phase inversion is performed

\begin{equation}

[\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} = \left\{

\begin{array}{ll}

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{-{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \gt 0 \;\; n \le \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \gt 0 \;\; n \gt \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \lt 0 \;\; n \le \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{-{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \lt 0 \;\; n \gt \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

\end{array}

\right.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} = \left\{

\begin{array}{ll}

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{-{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \gt 0 \;\; n \le \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \gt 0 \;\; n \gt \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \lt 0 \;\; n \le \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

|[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l}| {\rm e}^{-{\rm j} \; \textrm{arg}[\bar{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}}]_{n,l} } & k_{\textrm{LO}} \lt 0 \;\; n \gt \hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim} \ f_\textrm{s} , \\

\end{array}

\right.

\end{equation} yielding the pre-processed signal ![]() $\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}} \approx \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}$ that can be used as input to the subsequent processing steps.

$\tilde{\mathbf{X}}_{\textrm{IF}} \approx \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}$ that can be used as input to the subsequent processing steps.

Signal component separation

The joint estimation of all unknown parameters in ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ appears to be impractical due to the high dimensionality of the resulting estimation problem. Therefore, a prior separation of the different signal components based on their different DoAs is proposed. To this end, determination of

$\boldsymbol{\theta}$ appears to be impractical due to the high dimensionality of the resulting estimation problem. Therefore, a prior separation of the different signal components based on their different DoAs is proposed. To this end, determination of ![]() $P$ as well as the corresponding DoAs is initially required. The obtained DoAs allow to synthesize beam steering vectors that maximize the signal energy out of a certain DoA while at the same time suppressing the signal energy from all other DoAs. Also, the obtained DoAs can be used for the localization concept, which will be shown later.

$P$ as well as the corresponding DoAs is initially required. The obtained DoAs allow to synthesize beam steering vectors that maximize the signal energy out of a certain DoA while at the same time suppressing the signal energy from all other DoAs. Also, the obtained DoAs can be used for the localization concept, which will be shown later.

As a first step, the amount of spatial frequencies corresponding to ![]() $P$ has to be detected. For this task, state-of-the-art model order selection criteria such as power-spectrum-based constant false alarm rate (CFAR) detection, minimum description length (MDL) or Akaike information criterion (AIC) can be used [Reference Djukanovic and Popovic-Bugarin21, Reference Javidi da Costa, Thakre, Roemer and Haardt22]. Next, a (scaled) estimate of the array correlation matrix

$P$ has to be detected. For this task, state-of-the-art model order selection criteria such as power-spectrum-based constant false alarm rate (CFAR) detection, minimum description length (MDL) or Akaike information criterion (AIC) can be used [Reference Djukanovic and Popovic-Bugarin21, Reference Javidi da Costa, Thakre, Roemer and Haardt22]. Next, a (scaled) estimate of the array correlation matrix ![]() $\mathbf{R}_{\mathbf{ll}}$ is obtained by using all available time-domain samples as snapshots

$\mathbf{R}_{\mathbf{ll}}$ is obtained by using all available time-domain samples as snapshots ![]() ${\hat{\mathbf{R}}_{\mathbf{ll}} = \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}^H \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}}$. Subsequently, standard beamforming techniques like delay-and-sum, Capon, or multiple signal classification (MUSIC) can be applied to this matrix, depending on the required angular resolution in relation to the given array size.

${\hat{\mathbf{R}}_{\mathbf{ll}} = \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}^H \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}}$. Subsequently, standard beamforming techniques like delay-and-sum, Capon, or multiple signal classification (MUSIC) can be applied to this matrix, depending on the required angular resolution in relation to the given array size.

Assuming that ![]() $P$ has been correctly identified, the beamforming step yields

$P$ has been correctly identified, the beamforming step yields ![]() $P+1$ estimates for the DoAs

$P+1$ estimates for the DoAs  ${\hat{\theta}_{\textrm{DoA,}0}, \ldots , \hat{\theta}_{\textrm{DoA,}P}}$ which can be used to generate

${\hat{\theta}_{\textrm{DoA,}0}, \ldots , \hat{\theta}_{\textrm{DoA,}P}}$ which can be used to generate ![]() $P+1$ beam steering vectors. Ideally, the

$P+1$ beam steering vectors. Ideally, the ![]() $p$th beam steering vector

$p$th beam steering vector ![]() $\mathbf{b}_{p}$ should be chosen such that

$\mathbf{b}_{p}$ should be chosen such that  ${[\mathbf{H}_{\textrm{AF}} \mathbf{b}_{p}^{*}]_{p'} = c_p \delta_{pp'}}$ holds for a certain

${[\mathbf{H}_{\textrm{AF}} \mathbf{b}_{p}^{*}]_{p'} = c_p \delta_{pp'}}$ holds for a certain ![]() $c_p \ne 0$,

$c_p \ne 0$, ![]() $\delta$ being the Kronecker delta and

$\delta$ being the Kronecker delta and ![]() ${p' \in\{0, 1, \ldots , P\}}$. In this work, we propose to apply the null-steering-based least squares error pattern synthesis method for this purpose [Reference Van Trees23]. Afterwards, the individual signal components

${p' \in\{0, 1, \ldots , P\}}$. In this work, we propose to apply the null-steering-based least squares error pattern synthesis method for this purpose [Reference Van Trees23]. Afterwards, the individual signal components ![]() $\mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p}$ can be obtained by

$\mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p}$ can be obtained by  ${\mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p} = \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}} \mathbf{b}_{p}^{*}}$. According to (11),

${\mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p} = \mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}} \mathbf{b}_{p}^{*}}$. According to (11), ![]() $\mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p}$ can be modeled as

$\mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p}$ can be modeled as

with

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{f}_{\textrm{FT},p}]_{n} = \mathrm{rect} \left( \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}} n + f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} f_\textrm{s} } {2 B_{\textrm{IF}} f_\textrm{s} } \right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{f}_{\textrm{FT},p}]_{n} = \mathrm{rect} \left( \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}} n + f_{\textrm{IF0,}p} f_\textrm{s} } {2 B_{\textrm{IF}} f_\textrm{s} } \right),

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

[\mathbf{h}_{\textrm{FT},p}]_{n} = {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\left(2 \pi \frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}}{f_\textrm{s}} n + \pi \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}}}{f_\textrm{s}^2} n^2 \right)},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\mathbf{h}_{\textrm{FT},p}]_{n} = {\rm e}^{{\rm j}\left(2 \pi \frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}}{f_\textrm{s}} n + \pi \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}}}{f_\textrm{s}^2} n^2 \right)},

\end{equation}and a reduced vector of unknowns

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{\theta}_p = [\,f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}, k_{\textrm{IF}}, A_{\textrm{IF,}p}, \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}p}, \sigma_p^2]^{\rm T}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{\theta}_p = [\,f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}, k_{\textrm{IF}}, A_{\textrm{IF,}p}, \varphi_{\textrm{IF0,}p}, \sigma_p^2]^{\rm T}.

\end{equation}Time-frequency estimation

In this section, we will investigate the optimal estimation of ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}_p$ with the goal of obtaining a time-frequency sample of the interfering waveform with the best possible precision. To this end, the estimation of

$\boldsymbol{\theta}_p$ with the goal of obtaining a time-frequency sample of the interfering waveform with the best possible precision. To this end, the estimation of ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}_p$ in an ML sense is proposed as a first step. Considering (15), the ML estimator is found by maximizing

$\boldsymbol{\theta}_p$ in an ML sense is proposed as a first step. Considering (15), the ML estimator is found by maximizing

\begin{equation}

\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_p' = \mathop{\arg\max}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}_p'} {\underbrace{| (\mathbf{f}_{\textrm{FT},p} \odot \mathbf{h}_{\textrm{FT},p})^H \mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p} |^2 }_{J'(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p')}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_p' = \mathop{\arg\max}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}_p'} {\underbrace{| (\mathbf{f}_{\textrm{FT},p} \odot \mathbf{h}_{\textrm{FT},p})^H \mathbf{x}_{\textrm{IF,}p} |^2 }_{J'(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p')}},

\end{equation} where  ${\boldsymbol{\theta}_p' = [f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}, k_{\textrm{IF}}]^T}$ is a reduced (concentrated) parameter vector and

${\boldsymbol{\theta}_p' = [f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}, k_{\textrm{IF}}]^T}$ is a reduced (concentrated) parameter vector and  $J'(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p')$ is the (concentrated) likelihood function. In order to further elaborate the estimation concept, examples for

$J'(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p')$ is the (concentrated) likelihood function. In order to further elaborate the estimation concept, examples for  $J'(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p')$ were simulated using the parameters summarized in Table 1 for

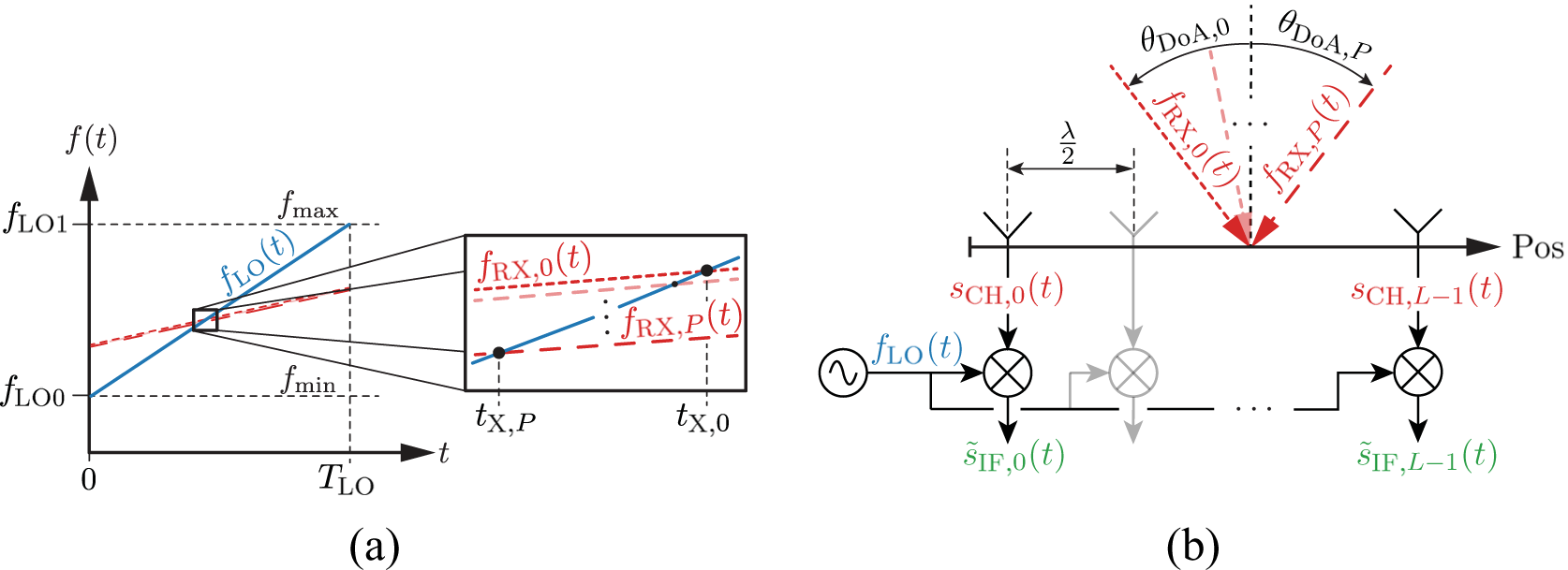

$J'(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p')$ were simulated using the parameters summarized in Table 1 for ![]() $p=0$ and a noiseless scenario. The results are shown in fig. 3(a), where two different IF bandwidths are compared. As evident, in the case of the lower IF bandwidth, the energy within the likelihood function is spread over a larger area, indicating that the estimation of

$p=0$ and a noiseless scenario. The results are shown in fig. 3(a), where two different IF bandwidths are compared. As evident, in the case of the lower IF bandwidth, the energy within the likelihood function is spread over a larger area, indicating that the estimation of ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}_p'$ becomes more imprecise in a noisy scenario.

$\boldsymbol{\theta}_p'$ becomes more imprecise in a noisy scenario.

Figure 3. Exemplary concentrated likelihood functions for both a high and a low ![]() $B_\textrm{IF}$. (a) Original parameter space. Due to the energy spread, estimation of

$B_\textrm{IF}$. (a) Original parameter space. Due to the energy spread, estimation of ![]() $f_{\textrm{IF0,}0}$ becomes more imprecise at a lower IF bandwidth. (b) Transformed parameter space. The energy spread is minimized in the direction of

$f_{\textrm{IF0,}0}$ becomes more imprecise at a lower IF bandwidth. (b) Transformed parameter space. The energy spread is minimized in the direction of ![]() $f_{\textrm{RXX,}0}$, allowing its precise estimation also in case of a low IF bandwidth.

$f_{\textrm{RXX,}0}$, allowing its precise estimation also in case of a low IF bandwidth.

Table 1. Parameter set for simulation of likelihood functions

For the aspect of spectral sensing, ![]() $f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}$ could theoretically be used to obtain the time-frequency sample

$f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}$ could theoretically be used to obtain the time-frequency sample ![]() $(t{=}0, f{=}f_{\textrm{RX0,}p})$ according to (3). However, since cost-efficient automotive FMCW radar sensors typically feature IF bandwidths in the order of the lower simulated bandwidth, the estimation accuracy would be unsatisfactory. Therefore, we propose applying a coordinate transformation to a different frequency that can be estimated with high precision also in the case of low IF bandwidths. To this end, note that

$(t{=}0, f{=}f_{\textrm{RX0,}p})$ according to (3). However, since cost-efficient automotive FMCW radar sensors typically feature IF bandwidths in the order of the lower simulated bandwidth, the estimation accuracy would be unsatisfactory. Therefore, we propose applying a coordinate transformation to a different frequency that can be estimated with high precision also in the case of low IF bandwidths. To this end, note that ![]() $t_{\textrm{X,}p}$ defined in (5) can, according to (8b) and (8c), also be expressed through

$t_{\textrm{X,}p}$ defined in (5) can, according to (8b) and (8c), also be expressed through ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}_p'$ as

$\boldsymbol{\theta}_p'$ as

\begin{equation}

t_{\textrm{X,}p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p') = \frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,p}}}{k_{\textrm{IF}}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

t_{\textrm{X,}p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p') = \frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,p}}}{k_{\textrm{IF}}}.

\end{equation} Furthermore, considering the corresponding instantaneous frequency ![]() $f_{\textrm{RXX,}p} = f_{\textrm{RX,}p}(t= t_{\textrm{X,}p})$ given by (3) results in

$f_{\textrm{RXX,}p} = f_{\textrm{RX,}p}(t= t_{\textrm{X,}p})$ given by (3) results in

\begin{equation}

f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p') = f_{\textrm{LO0}} + \frac{k_{\textrm{LO}}}{k_{\textrm{IF}}} f_{\textrm{IF0,p}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_p') = f_{\textrm{LO0}} + \frac{k_{\textrm{LO}}}{k_{\textrm{IF}}} f_{\textrm{IF0,p}}.

\end{equation} This relationship allows to express the concentrated likelihood functions in terms of the transformed parameter vector  ${\boldsymbol{\theta}_p^{\prime\prime} = [f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}, k_{\textrm{IF}}]^T}$, which is shown in fig. 3(b). As evident, the spread of energy is now maximized along

${\boldsymbol{\theta}_p^{\prime\prime} = [f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}, k_{\textrm{IF}}]^T}$, which is shown in fig. 3(b). As evident, the spread of energy is now maximized along ![]() $k_{\textrm{IF}}$ and minimized along the

$k_{\textrm{IF}}$ and minimized along the ![]() $f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}$-direction, indicating that the coupling between both variables is minimized. This observation suggests that

$f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}$-direction, indicating that the coupling between both variables is minimized. This observation suggests that ![]() $f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}$ can be estimated more precisely than

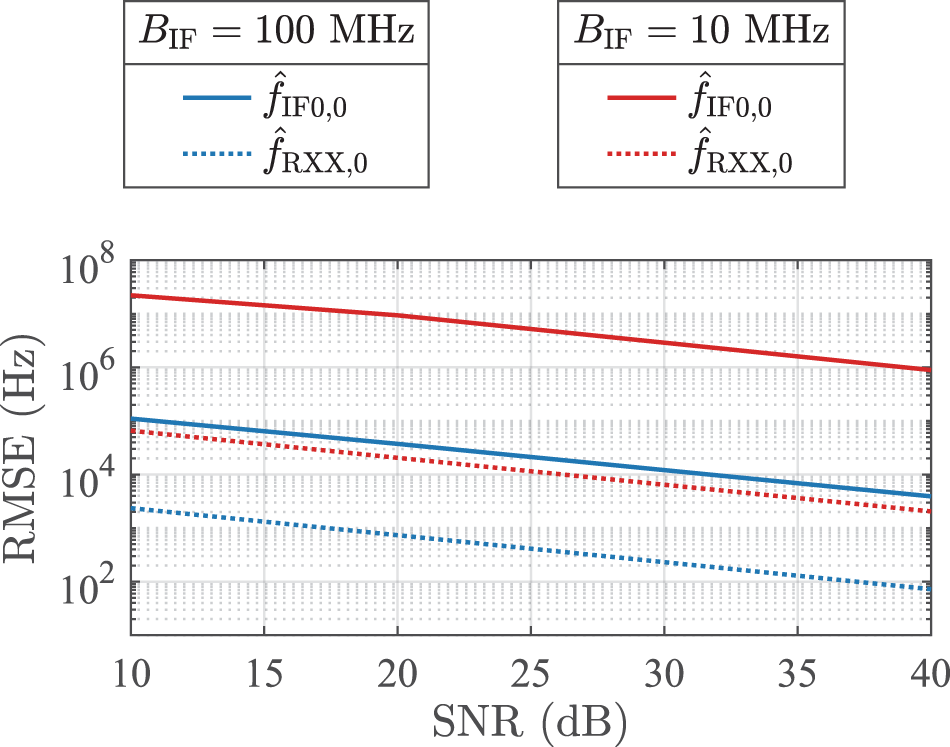

$f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}$ can be estimated more precisely than ![]() $f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}$, which is further supported by the performance comparison shown in Figure 4. Accordingly, at an exemplary SNR of

$f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}$, which is further supported by the performance comparison shown in Figure 4. Accordingly, at an exemplary SNR of ![]() $10\,\mathrm{dB}$,

$10\,\mathrm{dB}$, ![]() $f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}$ yields a moderate root mean squared error (RMSE) of

$f_{\textrm{RXX,}p}$ yields a moderate root mean squared error (RMSE) of ![]() $\approx 60\,\mathrm{kHz}$, whereas for

$\approx 60\,\mathrm{kHz}$, whereas for ![]() $f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}$ it is

$f_{\textrm{IF0,}p}$ it is ![]() $\approx 20\,\mathrm{MHz}$.

$\approx 20\,\mathrm{MHz}$.

Figure 4. Comparison of RMSE of  $\hat{f}_{\textrm{IF0,}0}$ and

$\hat{f}_{\textrm{IF0,}0}$ and  $\hat{f}_{\textrm{RXX,}0}$ for a high and a low IF bandwidth, obtained by Monte-Carlo simulations. The transformation of the frequency variable yields a significant performance improvement.

$\hat{f}_{\textrm{RXX,}0}$ for a high and a low IF bandwidth, obtained by Monte-Carlo simulations. The transformation of the frequency variable yields a significant performance improvement.

The proposed time-frequency point that can be used for passive spectral sensing is therefore given by ![]() $(t{=}t_{\textrm{X,}p}, f{=}f_{\textrm{RXX,}p})$. Although the estimates can be very similar for different path indices

$(t{=}t_{\textrm{X,}p}, f{=}f_{\textrm{RXX,}p})$. Although the estimates can be very similar for different path indices ![]() $p$, their precise determination will become important for the aspect of object localization, which will be explained in the next section.

$p$, their precise determination will become important for the aspect of object localization, which will be explained in the next section.

Object localization

As mentioned previously, joint DoA-TDoA-based object localization is proposed. To this end, the direct and the indirect signal path created by an object will be conceptually assigned to the reference and surveillance channel within the passive radar framework, respectively. This can be achieved by first identifying the direct signal path, e.g., by choosing the signal component with the highest ![]() $A_{\textrm{IF,p}}$. Next, the TDoA information for the (indirect) signal paths

$A_{\textrm{IF,p}}$. Next, the TDoA information for the (indirect) signal paths ![]() $p \gt 0$ with respect to the direct signal path, denoted as

$p \gt 0$ with respect to the direct signal path, denoted as ![]() $\tau_{p0}$, can be computed. Its general definition

$\tau_{p0}$, can be computed. Its general definition ![]() ${\tau_{p0} = \tau_{p} - \tau_{0}}$ can be re-expressed using the results from (3b), (3a), (8b), (8c) and (18) as

${\tau_{p0} = \tau_{p} - \tau_{0}}$ can be re-expressed using the results from (3b), (3a), (8b), (8c) and (18) as

\begin{equation}

\tau_{p0} = \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}}}{k_{\textrm{LO}}} \frac{f_{\textrm{RXX,}p} - f_{\textrm{RXX,}0}}{k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\tau_{p0} = \frac{k_{\textrm{IF}}}{k_{\textrm{LO}}} \frac{f_{\textrm{RXX,}p} - f_{\textrm{RXX,}0}}{k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}}},

\end{equation} which contains the results from the previous time-frequency estimation step as well as the known value for ![]() $k_{\textrm{LO}}$. The corresponding geometric representation of

$k_{\textrm{LO}}$. The corresponding geometric representation of ![]() $\tau_{p0}$ is given by an (iso-TDoA) ellipse

$\tau_{p0}$ is given by an (iso-TDoA) ellipse ![]() $E_{p}$ with both the passive and the interfering radar sensor located at its foci. Therefore, in order to use

$E_{p}$ with both the passive and the interfering radar sensor located at its foci. Therefore, in order to use ![]() $\tau_{p0}$ for localization, the position of the interferer

$\tau_{p0}$ for localization, the position of the interferer ![]() $P_0$ with respect to the passive radar sensor has to be determined. In the following, a triangulation-based solution using a second (auxiliary) radar sensor in addition to the first (primary) radar sensor is proposed for this purpose. Ideally, this auxiliary radar sensor is placed such that dilution of precision (DOP) for triangulation is minimized, while at the same time, a stable direct signal path to the interferer can be maintained. One suitable way could be to place both radar sensors close to the outer bumper corners of the passively sensing vehicle. In addition, the auxiliary radar sensor applies the same sweeping LO and signal processing steps as the primary sensor, and its LO ramps can be triggered using a coarse time synchronization link to the primary radar sensor. Even though this sensor could be used to further improve the overall localization quality in a passive radar network setup, in this work, it will only be used for the purpose of finding

$P_0$ with respect to the passive radar sensor has to be determined. In the following, a triangulation-based solution using a second (auxiliary) radar sensor in addition to the first (primary) radar sensor is proposed for this purpose. Ideally, this auxiliary radar sensor is placed such that dilution of precision (DOP) for triangulation is minimized, while at the same time, a stable direct signal path to the interferer can be maintained. One suitable way could be to place both radar sensors close to the outer bumper corners of the passively sensing vehicle. In addition, the auxiliary radar sensor applies the same sweeping LO and signal processing steps as the primary sensor, and its LO ramps can be triggered using a coarse time synchronization link to the primary radar sensor. Even though this sensor could be used to further improve the overall localization quality in a passive radar network setup, in this work, it will only be used for the purpose of finding ![]() $P_0$. Therefore, after identifying the primary signal path at both primary and auxiliary radar stations, the corresponding values

$P_0$. Therefore, after identifying the primary signal path at both primary and auxiliary radar stations, the corresponding values ![]() $\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}0}$ and

$\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}0}$ and ![]() $\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}0}'$ yield lines

$\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}0}'$ yield lines ![]() $L_{0}$ and

$L_{0}$ and ![]() $L_{0}'$ as geometric representations, and their intersection point yields

$L_{0}'$ as geometric representations, and their intersection point yields ![]() $P_0$ in a suitable coordinate system. Considering that

$P_0$ in a suitable coordinate system. Considering that ![]() $P_0$ and

$P_0$ and ![]() $\tau_{p0}$ now fully define

$\tau_{p0}$ now fully define ![]() $E_{p}$, and that

$E_{p}$, and that ![]() $L_{p}$ further denotes the geometric line representation corresponding to

$L_{p}$ further denotes the geometric line representation corresponding to ![]() $\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}p}$ of an object, the latter can be localized by computing the geometric intersection point between

$\theta_{\textrm{DoA,}p}$ of an object, the latter can be localized by computing the geometric intersection point between ![]() $E_{p}$ and

$E_{p}$ and ![]() $L_{p}$, denoted as

$L_{p}$, denoted as ![]() $P_p$. This localization procedure is summarized and depicted in fig. 5.

$P_p$. This localization procedure is summarized and depicted in fig. 5.

Figure 5. Visualization of the proposed localization principle using a primary and an auxiliary radar sensor. Firstly, the position of the interferer ![]() $P_0$ is determined by triangulation of

$P_0$ is determined by triangulation of ![]() $L_{0}$ and

$L_{0}$ and ![]() $L_{0}'$. Secondly, the position of another object in the scene

$L_{0}'$. Secondly, the position of another object in the scene ![]() $P_p$ is given by intersecting

$P_p$ is given by intersecting ![]() $L_{p}$ and

$L_{p}$ and ![]() $E_{p}$.

$E_{p}$.

For completeness, it should be noted that the interferer could also be localized by evaluating TDoA information between the primary and the auxiliary radar sensor [Reference Liu, Yang and Wang24]. However, since such a method requires a fine time synchronization (in the order of a few ns) between the primary and auxiliary radar sensor, it may not be practical for every automotive radar setup.

Multiple LO ramps

The focus of the preceding sections was on interference exploitation using an individual LO ramp. However, in automotive radar sensors, usually multiple consecutive LO ramps are performed (chirp sequence). Considering that an interferer is usually present for a period longer than that of a single LO ramp, in many cases, multiple of the received IF signals will be affected. This can be ensured due to the sweeping of the LO over the whole automotive frequency band, in particular for interferers with changing starting frequencies in a stepped FMCW modulation scheme and/or time and frequency dithering. While ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ in (11f) and the resulting time-frequency point generally being different for each IF signal, the positions of the interferer and surrounding objects may still be considered as similar for many IF signals. Therefore, averaging of these positions (

$\boldsymbol{\theta}$ in (11f) and the resulting time-frequency point generally being different for each IF signal, the positions of the interferer and surrounding objects may still be considered as similar for many IF signals. Therefore, averaging of these positions (![]() $P_0$ and

$P_0$ and ![]() $P_p$) is proposed to improve the quality of the localization. As will be shown in the next analysis section, this strategy will benefit in particular interference scenarios with a low effective bandwidth

$P_p$) is proposed to improve the quality of the localization. As will be shown in the next analysis section, this strategy will benefit in particular interference scenarios with a low effective bandwidth ![]() $B_{\textrm{eff}}$ and only a few interfered samples

$B_{\textrm{eff}}$ and only a few interfered samples ![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}}$, where the localization accuracy using only a single ramp would be insufficient. The latter case will also be shown in the measurement section, where the averaging significantly reduces the variances of the resulting localization estimates.

$N_{\textrm{IF}}$, where the localization accuracy using only a single ramp would be insufficient. The latter case will also be shown in the measurement section, where the averaging significantly reduces the variances of the resulting localization estimates.

Theoretical analysis

SNR range

In order to assess the practicability of the proposed concept, evaluating the possible range of SNRs created by an interfering signal is of special interest. To this end, the primary radar station is assumed to be located at the origin of a 2-D Cartesian coordinate system. In addition, the interferer and an object are assumed to be located at ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_0 =[x_{\textrm{0}},y_{\textrm{0}}]$ and

$\boldsymbol{P}_0 =[x_{\textrm{0}},y_{\textrm{0}}]$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_1 = [x_{\textrm{1}},y_{\textrm{1}}]$, respectively.

$\boldsymbol{P}_1 = [x_{\textrm{1}},y_{\textrm{1}}]$, respectively.

The SNR for the direct signal path based on the radar equation is given by

\begin{equation}

\textrm{SNR}_0 = \frac{P_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{RX}} \lambda^2}{\left(4\pi c_0 \tau_0 \right)^2 k_\textrm{B} T_\textrm{S} B_{\textrm{IF}} F},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\textrm{SNR}_0 = \frac{P_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{RX}} \lambda^2}{\left(4\pi c_0 \tau_0 \right)^2 k_\textrm{B} T_\textrm{S} B_{\textrm{IF}} F},

\end{equation}and further for the indirect signal path assuming a reflection at a flat widespread object with proper alignment

\begin{equation}

\textrm{SNR}_1 = \frac{

P_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{RX}} \lambda^2 } {(4\pi c_0 \tau_1)^2 k_\textrm{B} T_\textrm{S} B_{\textrm{IF}} F},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\textrm{SNR}_1 = \frac{

P_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{TX}} G_{\textrm{RX}} \lambda^2 } {(4\pi c_0 \tau_1)^2 k_\textrm{B} T_\textrm{S} B_{\textrm{IF}} F},

\end{equation} where ![]() $P_{\textrm{TX}}$ is the transmit power of the interferer,

$P_{\textrm{TX}}$ is the transmit power of the interferer, ![]() $G_{\textrm{TX}}$ and

$G_{\textrm{TX}}$ and ![]() $G_{\textrm{RX}}$ are the antenna gains of the interferer and the primary station, respectively. Furthermore,

$G_{\textrm{RX}}$ are the antenna gains of the interferer and the primary station, respectively. Furthermore, ![]() $\lambda$ is the wavelength,

$\lambda$ is the wavelength, ![]() $k_\textrm{B}$ is the Boltzmann constant, and

$k_\textrm{B}$ is the Boltzmann constant, and ![]() $T_\textrm{S}$ and

$T_\textrm{S}$ and ![]() $F$ are the primary stations’ system temperature and noise figure, respectively. Also, the corresponding path delays are given by

$F$ are the primary stations’ system temperature and noise figure, respectively. Also, the corresponding path delays are given by

\begin{equation}

\tau_0 = \frac{1}{c_0} \sqrt{x_{\textrm{0}}^2 + y_{\textrm{0}}^2},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\tau_0 = \frac{1}{c_0} \sqrt{x_{\textrm{0}}^2 + y_{\textrm{0}}^2},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\tau_1 = \frac{1}{c_0} \left( \sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2} + \sqrt{(x_{\textrm{0}}-x_{\textrm{1}})^2 + (y_{\textrm{0}}-y_{\textrm{1}})^2} \right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\tau_1 = \frac{1}{c_0} \left( \sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2} + \sqrt{(x_{\textrm{0}}-x_{\textrm{1}})^2 + (y_{\textrm{0}}-y_{\textrm{1}})^2} \right),

\end{equation} where ![]() $c_0$ is the speed of light.

$c_0$ is the speed of light.

In order to also cover the influence of the antenna beampattern, we assume patch antenna elements with a cosine-squared amplitude dependency (field of view (FOV) ![]() $\approx 65^{\circ}$) on the DoA for both the interferer and the primary station. If alignment of the antenna boresight directions with the y-axis is assumed, this yields

$\approx 65^{\circ}$) on the DoA for both the interferer and the primary station. If alignment of the antenna boresight directions with the y-axis is assumed, this yields

\begin{equation}

G_{\textrm{TX}} = G_{\textrm{TX,max}} \left( \frac{|y_{\textrm{1}}|}{\sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2}} \right)^4,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

G_{\textrm{TX}} = G_{\textrm{TX,max}} \left( \frac{|y_{\textrm{1}}|}{\sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2}} \right)^4,

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

G_{\textrm{RX}} = G_{\textrm{RX,max}} \left(\frac{|y_{\textrm{1}}|}{\sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2}} \right)^4,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

G_{\textrm{RX}} = G_{\textrm{RX,max}} \left(\frac{|y_{\textrm{1}}|}{\sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2}} \right)^4,

\end{equation} where ![]() $G_{\textrm{TX,max}}$ and

$G_{\textrm{TX,max}}$ and ![]() $G_{\textrm{RX,max}}$ are the antenna gains of the interferer and the primary station in boresight direction, respectively. In the sequel, the following values were chosen to model a typical automotive setup:

$G_{\textrm{RX,max}}$ are the antenna gains of the interferer and the primary station in boresight direction, respectively. In the sequel, the following values were chosen to model a typical automotive setup: ![]() $P_{\textrm{TX}} = 10\,\mathrm{dBm}$,

$P_{\textrm{TX}} = 10\,\mathrm{dBm}$, ![]() $G_{\textrm{TX,max}} = G_{\textrm{RX,max}} = 10\mathrm{dBi}$,

$G_{\textrm{TX,max}} = G_{\textrm{RX,max}} = 10\mathrm{dBi}$, ![]() $\lambda = 3.896\,\mathrm{mm}$,

$\lambda = 3.896\,\mathrm{mm}$, ![]() $T_\textrm{S} = 333.15\,\mathrm{K}$,

$T_\textrm{S} = 333.15\,\mathrm{K}$, ![]() $F = 12\,\mathrm{dB}$.

$F = 12\,\mathrm{dB}$.

Figure 6(a) shows the resulting Iso-SNR contour plot of the direct signal path as a function of the interferer position ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_0$. Furthermore, fig. 6(a) shows an Iso-SNR contour plot of the indirect signal path as a function of the position of an object

$\boldsymbol{P}_0$. Furthermore, fig. 6(a) shows an Iso-SNR contour plot of the indirect signal path as a function of the position of an object ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_1$, where a fixed interferer position

$\boldsymbol{P}_1$, where a fixed interferer position ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ has been used. These results show that

$\boldsymbol{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ has been used. These results show that ![]() $\textrm{SNR}_0$ can be over

$\textrm{SNR}_0$ can be over ![]() $30\mathrm{dB}$ for interferers closer than

$30\mathrm{dB}$ for interferers closer than ![]() $10\,\mathrm{m}$ and close to boresight direction (e.g., a front and a rear radar of two vehicles driving one behind the other in a dense urban traffic environment). Also, larger distances such as

$10\,\mathrm{m}$ and close to boresight direction (e.g., a front and a rear radar of two vehicles driving one behind the other in a dense urban traffic environment). Also, larger distances such as ![]() $50\,\mathrm m$ can still yield considerable

$50\,\mathrm m$ can still yield considerable ![]() $17\,\mathrm{dB}$ of SNR. However, if the two radar sensors leave their mutual FOV (e.g., two front radars of two vehicles driving past each other), the influence of the antenna beampattern quickly reduces the available SNR. Similarly,

$17\,\mathrm{dB}$ of SNR. However, if the two radar sensors leave their mutual FOV (e.g., two front radars of two vehicles driving past each other), the influence of the antenna beampattern quickly reduces the available SNR. Similarly, ![]() $\textrm{SNR}_1$, which is limited by

$\textrm{SNR}_1$, which is limited by ![]() $\textrm{SNR}_0$ at the corresponding interferer position (

$\textrm{SNR}_0$ at the corresponding interferer position (![]() $17\,\mathrm{dB}$ in this example), also degrades significantly for objects outside the mutual FOV.

$17\,\mathrm{dB}$ in this example), also degrades significantly for objects outside the mutual FOV.

Figure 6. Iso-SNR contour plots. (a) Direct signal path (![]() $\textrm{SNR}_0$) for different interferer positions

$\textrm{SNR}_0$) for different interferer positions ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_0$. (b) Indirect signal path (

$\boldsymbol{P}_0$. (b) Indirect signal path (![]() $\textrm{SNR}_1$) for different object positions

$\textrm{SNR}_1$) for different object positions ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_1$ and fixed interferer position

$\boldsymbol{P}_1$ and fixed interferer position ![]() $\boldsymbol{P}_0 = [0, 50]$.

$\boldsymbol{P}_0 = [0, 50]$.

The SNR determines not only whether the interference can be reliably detected, but also the localization accuracy of objects. Both points will be analyzed in the next sections.

Minimum SNR

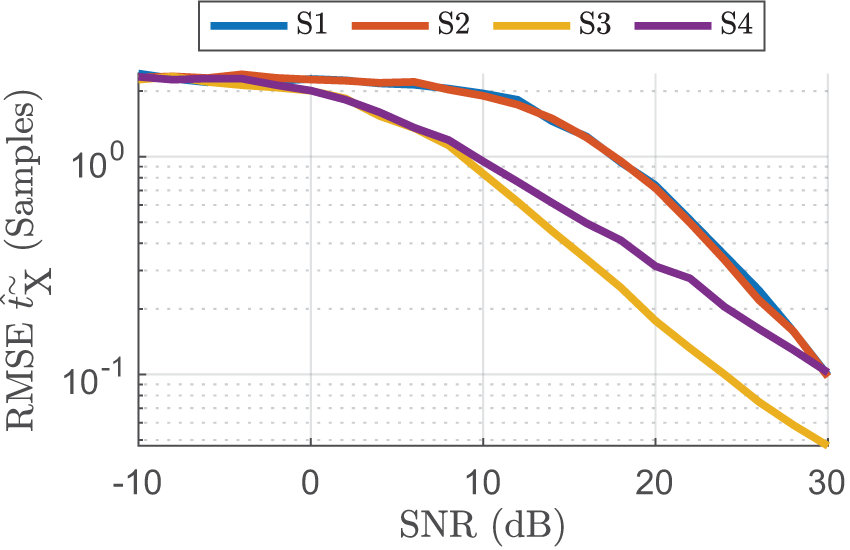

An important aspect with respect to the SNR is the minimum SNR for the algorithm to be applicable. Generally speaking, this minimum SNR is defined by requirements in terms of signal detectability in the first place. A limiting factor for the proposed signal detection in the angular domain is given by the estimate of ![]() $\hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim}$ in (13). Its estimation quality can be assessed by means of RMSE curves, which were simulated for four different interference scenarios S1–S4 summarized in Table 2. While S1 and S2 create short (

$\hat{t}_{\textrm{X}}^{\sim}$ in (13). Its estimation quality can be assessed by means of RMSE curves, which were simulated for four different interference scenarios S1–S4 summarized in Table 2. While S1 and S2 create short (![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}} = 10$ and

$N_{\textrm{IF}} = 10$ and ![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}} \approx 22$) and S3 medium-extended (

$N_{\textrm{IF}} \approx 22$) and S3 medium-extended (![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}} = 200$) interference patterns in the time-domain signal, for S4 all

$N_{\textrm{IF}} = 200$) interference patterns in the time-domain signal, for S4 all ![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}} = 1000$ samples of the IF signal are interfered. The resulting curves are shown in fig. 7. In accordance with the expectations, the RMSE decreases with increasing SNR, where the decrease starts at lower SNRs for larger

$N_{\textrm{IF}} = 1000$ samples of the IF signal are interfered. The resulting curves are shown in fig. 7. In accordance with the expectations, the RMSE decreases with increasing SNR, where the decrease starts at lower SNRs for larger ![]() $N_{\textrm{IF}}$. For an RMSE below 1 sample, the algorithm requires an SNR in the range

$N_{\textrm{IF}}$. For an RMSE below 1 sample, the algorithm requires an SNR in the range ![]() $[8, 18] \mathrm{dB}$, depending on the scenario. According to the previous SNR analysis, these values are realistic for a large range of possible interferer positions, such that a reasonable performance can be generally assumed. Noteworthy, since this analysis is not completely exhaustive, the provided SNR range represents a coarse estimate only. Additional requirements for the SNR can be further imposed by requirements on localization accuracy, which will be discussed next.

$[8, 18] \mathrm{dB}$, depending on the scenario. According to the previous SNR analysis, these values are realistic for a large range of possible interferer positions, such that a reasonable performance can be generally assumed. Noteworthy, since this analysis is not completely exhaustive, the provided SNR range represents a coarse estimate only. Additional requirements for the SNR can be further imposed by requirements on localization accuracy, which will be discussed next.

Figure 7. RMSE simulation for minimum SNR assessment.

Table 2. Parameter set for SNR and localization accuracy analysis

Localization accuracy

In this section, the accuracy of the proposed DoA-TDoA-based localization method will be investigated by means of DOP analysis for scenarios S1-S4. As will be seen, the localization accuracy depends on the position of both the interferer ![]() $\mathbf{P}_0 = [x_0,y_0]$ and the object

$\mathbf{P}_0 = [x_0,y_0]$ and the object ![]() $\mathbf{P}_p = [x_p,y_p]$ to be localized relative to the passive radar stations. This is due to not only the properties of the geometric localization approach, but also the SNR of the interference present at the receiver.

$\mathbf{P}_p = [x_p,y_p]$ to be localized relative to the passive radar stations. This is due to not only the properties of the geometric localization approach, but also the SNR of the interference present at the receiver.

For this analysis, the SNR is again modeled according to (20) and (21). In order to fully specify the parameter vector ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ in (11f) we further set the arbitrary phase arguments to

$\boldsymbol{\theta}$ in (11f) we further set the arbitrary phase arguments to ![]() $\varphi_\textrm{IF0,0}=0$ and

$\varphi_\textrm{IF0,0}=0$ and ![]() $\varphi_\textrm{IF0,1}=0$, and the noise variance to

$\varphi_\textrm{IF0,1}=0$, and the noise variance to ![]() $\sigma^2=1$ since for the accuracy of the proposed localization method only the SNR is relevant. For simplicity, it is further assumed that

$\sigma^2=1$ since for the accuracy of the proposed localization method only the SNR is relevant. For simplicity, it is further assumed that ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ is jointly estimated in an ML sense. Its error covariance matrix

$\boldsymbol{\theta}$ is jointly estimated in an ML sense. Its error covariance matrix ![]() $\boldsymbol{C}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}\boldsymbol{\theta}}$ is for large data records is consequently given by

$\boldsymbol{C}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}\boldsymbol{\theta}}$ is for large data records is consequently given by

with the Fisher information matrix ![]() $\boldsymbol{I}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) $ defined by

$\boldsymbol{I}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) $ defined by

\begin{equation}

[\boldsymbol{I}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{a,b} = - \mathbb{E} \left[ \frac{\partial^2 \log p(\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) }

{\partial \theta_{a} \partial \theta_{b} } \right], \end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[\boldsymbol{I}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{\theta})]_{a,b} = - \mathbb{E} \left[ \frac{\partial^2 \log p(\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) }

{\partial \theta_{a} \partial \theta_{b} } \right], \end{equation} where ![]() $p(\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}; \boldsymbol{\theta})$ is the probability density function (PDF) of

$p(\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}; \boldsymbol{\theta})$ is the probability density function (PDF) of ![]() $\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}$ parameterized by

$\mathbf{X}_{\textrm{IF}}$ parameterized by ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta}$, and

$\boldsymbol{\theta}$, and ![]() $a, b\in \{0, \ldots 4P+5\}$. Its convenient computation for the problem at hand (

$a, b\in \{0, \ldots 4P+5\}$. Its convenient computation for the problem at hand (![]() $P=1$) is possible by applying the result from [Reference Kay25, p. 525] to the transformed parameter vector

$P=1$) is possible by applying the result from [Reference Kay25, p. 525] to the transformed parameter vector

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\textrm{loc}} =

[&f_{\textrm{IF0,}0}, f_{\textrm{IF0,}1}, k_{\textrm{IF}}, a_{\textrm{IF,}0}, a_{\textrm{IF,}1}, \\

& b_{\textrm{IF,}0}, b_{\textrm{IF,}P}, u_0, u_1, \sigma^2]^{\rm T},

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\textrm{loc}} =

[&f_{\textrm{IF0,}0}, f_{\textrm{IF0,}1}, k_{\textrm{IF}}, a_{\textrm{IF,}0}, a_{\textrm{IF,}1}, \\

& b_{\textrm{IF,}0}, b_{\textrm{IF,}P}, u_0, u_1, \sigma^2]^{\rm T},

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}where

This yields the Fisher information matrix

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{I}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\textrm{loc}}} = \begin{bmatrix}

\frac{2}{\sigma^2} \textrm{Re}(\boldsymbol{D}^\textrm{H} \boldsymbol{D}) & \boldsymbol{0} \\

\boldsymbol{0}^\textrm{T} & \frac{NL}{(\sigma^2)^2} \\

\end{bmatrix},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{I}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\textrm{loc}}} = \begin{bmatrix}

\frac{2}{\sigma^2} \textrm{Re}(\boldsymbol{D}^\textrm{H} \boldsymbol{D}) & \boldsymbol{0} \\

\boldsymbol{0}^\textrm{T} & \frac{NL}{(\sigma^2)^2} \\

\end{bmatrix},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{D}_{f} = \mathbf{H}_{\textrm{AF}}^{\rm T} \ast (\mathbf{R}_{\textrm{FT}} \odot \mathbf{D}_{N} \mathbf{H}_{\textrm{FT}} ) \mathbf{A},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{D}_{f} = \mathbf{H}_{\textrm{AF}}^{\rm T} \ast (\mathbf{R}_{\textrm{FT}} \odot \mathbf{D}_{N} \mathbf{H}_{\textrm{FT}} ) \mathbf{A},

\end{equation} Next, the error covariance matrix for the parameter vector ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}} = [u_{\textrm{1}}, \tau_{10}]^T$, which is required for DoA-TDoA-based object localization is given by the relation [Reference Kay25]

$\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}} = [u_{\textrm{1}}, \tau_{10}]^T$, which is required for DoA-TDoA-based object localization is given by the relation [Reference Kay25]

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{C}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}} \boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}} \boldsymbol{I}^{-1}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}^T}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{C}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}} \boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}} \boldsymbol{I}^{-1}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}^T}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}},

\end{equation}where

\begin{equation}

\left[ \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}} \right]_{c,a} = \left\{

\begin{array}{ll}

1 & c=0, a=8\\

-\frac{1}{k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}}} & c=1, a=0\\[5pt]

\frac{1}{k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}}} & c=1, a=1\\[5pt]

\frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,0}} - f_{\textrm{IF0,1}}}{(k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}})^2} & c=1, a=2\\[5pt]

0 & \, \textrm{else}, \\

\end{array}

\right.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left[ \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{loc}}}} \right]_{c,a} = \left\{

\begin{array}{ll}

1 & c=0, a=8\\

-\frac{1}{k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}}} & c=1, a=0\\[5pt]

\frac{1}{k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}}} & c=1, a=1\\[5pt]

\frac{f_{\textrm{IF0,0}} - f_{\textrm{IF0,1}}}{(k_{\textrm{LO}} - k_{\textrm{IF}})^2} & c=1, a=2\\[5pt]

0 & \, \textrm{else}, \\

\end{array}

\right.

\end{equation} and ![]() $c \in \{0, 1\}$.

$c \in \{0, 1\}$.

Finally, the relation of ![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}$ to

$\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}$ to ![]() $\mathbf{P}_1 = [x_1, y_1]$ is given by the sensor measurement residual equations

$\mathbf{P}_1 = [x_1, y_1]$ is given by the sensor measurement residual equations ![]() $\boldsymbol{f} = [f_1(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1), f_2(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1)]^{\rm T}$

$\boldsymbol{f} = [f_1(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1), f_2(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1)]^{\rm T}$

\begin{equation}

f_1(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1) = u_{\textrm{1}} +\frac{x_{\textrm{1}}}{\sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2+y_{\textrm{1}}^2}}= 0,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

f_1(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1) = u_{\textrm{1}} +\frac{x_{\textrm{1}}}{\sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2+y_{\textrm{1}}^2}}= 0,

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

& f_2(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1) = \tau_{\textrm{10}} - \frac{1}{c_0}\left( \sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2+y_{\textrm{1}}^2} + \right. \\

& \left. \sqrt{(x_{\textrm{1}}-x_{\textrm{0}})^2+(y_{\textrm{1}}-y_{\textrm{0}})^2} - \sqrt{x_{\textrm{0}}^2+y_{\textrm{0}}^2} \right) = 0.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

& f_2(\boldsymbol{\theta_{\textrm{1,loc}}}, \mathbf{P}_1) = \tau_{\textrm{10}} - \frac{1}{c_0}\left( \sqrt{x_{\textrm{1}}^2+y_{\textrm{1}}^2} + \right. \\

& \left. \sqrt{(x_{\textrm{1}}-x_{\textrm{0}})^2+(y_{\textrm{1}}-y_{\textrm{0}})^2} - \sqrt{x_{\textrm{0}}^2+y_{\textrm{0}}^2} \right) = 0.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} DOP analysis, which assumes that (33) is solved by applying the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE) to a linearized version of the equation system [Reference Langley26], yields the error covariance matrix ![]() $\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ given by

$\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ given by

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1} = ( \mathbf{J}_{\mathbf{P}_1}^{{\rm T}} (\mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} \boldsymbol{I}^{-1}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}}^{{\rm T}} )^{-1} \mathbf{J}_{\mathbf{P}_1})^{-1},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1} = ( \mathbf{J}_{\mathbf{P}_1}^{{\rm T}} (\mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} \boldsymbol{I}^{-1}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}}^{{\rm T}} )^{-1} \mathbf{J}_{\mathbf{P}_1})^{-1},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} ,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} ,

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\mathbf{J}_{\mathbf{P}_1} = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}}{\partial \mathbf{P}_1} ,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{J}_{\mathbf{P}_1} = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{f}}{\partial \mathbf{P}_1} ,

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 \\

\end{bmatrix},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{\theta_{1,\textrm{loc}}}} = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 \\

\end{bmatrix},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

[ \mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{x}_{\textrm{1}}}]_{0,0} = \frac{y_{\textrm{1}}^2}{(x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2)^{3/2}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[ \mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{x}_{\textrm{1}}}]_{0,0} = \frac{y_{\textrm{1}}^2}{(x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2)^{3/2}},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

[ \mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{x}_{\textrm{1}}}]_{0,1} = \frac{- x_{\textrm{1}} y_{\textrm{1}} }{(x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2)^{3/2}} ,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

[ \mathbf{J}_{\boldsymbol{x}_{\textrm{1}}}]_{0,1} = \frac{- x_{\textrm{1}} y_{\textrm{1}} }{(x_{\textrm{1}}^2 + y_{\textrm{1}}^2)^{3/2}} ,

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

{[{{\boldsymbol{J}}_{{{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\rm{1}}}}}]_{1,0}} = - \frac{1}{{{c_0}}}\left( {\frac{{{x_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {x_{\rm{1}}^2 + y_{\rm{1}}^2} }}} \right.\\

\left. { - \frac{{{x_{\rm{0}}} - {x_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {{{\left( {{x_{\rm{0}}} - {x_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left( {{y_{\rm{0}}} - {y_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2}} }}} \right),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

{[{{\boldsymbol{J}}_{{{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\rm{1}}}}}]_{1,0}} = - \frac{1}{{{c_0}}}\left( {\frac{{{x_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {x_{\rm{1}}^2 + y_{\rm{1}}^2} }}} \right.\\

\left. { - \frac{{{x_{\rm{0}}} - {x_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {{{\left( {{x_{\rm{0}}} - {x_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left( {{y_{\rm{0}}} - {y_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2}} }}} \right),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

{[{{\boldsymbol{J}}_{{{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\rm{1}}}}}]_{1,1}} = \frac{1}{{{c_0}}}\left( {\frac{{{y_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {y_{\rm{1}}^2 + x_{\rm{1}}^2} }}} \right.\\

\left. { - \frac{{{y_{\rm{0}}} - {y_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {{{\left( {{y_{\rm{0}}} - {y_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left( {{x_{\rm{0}}} - {x_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2}} }}} \right).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

{[{{\boldsymbol{J}}_{{{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\rm{1}}}}}]_{1,1}} = \frac{1}{{{c_0}}}\left( {\frac{{{y_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {y_{\rm{1}}^2 + x_{\rm{1}}^2} }}} \right.\\

\left. { - \frac{{{y_{\rm{0}}} - {y_{\rm{1}}}}}{{\sqrt {{{\left( {{y_{\rm{0}}} - {y_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left( {{x_{\rm{0}}} - {x_{\rm{1}}}} \right)}^2}} }}} \right).

\end{aligned}

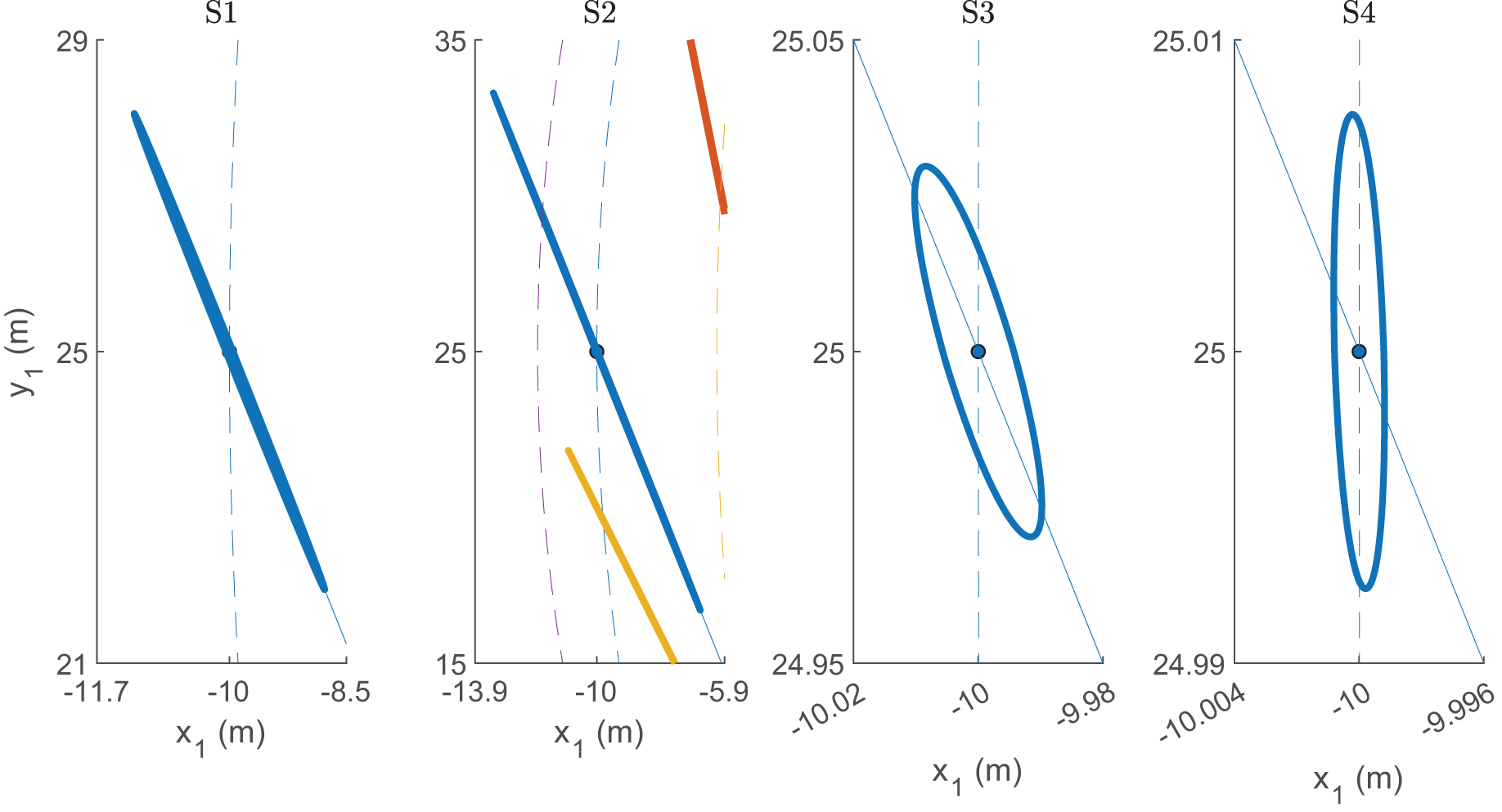

\end{equation} In fig. 8, ![]() $\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ is visualized by means of error ellipses for different positions of

$\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ is visualized by means of error ellipses for different positions of ![]() $\mathbf{P}_1$ and a fixed interferer position

$\mathbf{P}_1$ and a fixed interferer position ![]() $\mathbf{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ for all defined scenarios. Noteworthy, for S3 and S4 the error ellipses are no longer visible due to their small size. Therefore, in fig. 9, a zoomed-in version of the error ellipse for

$\mathbf{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ for all defined scenarios. Noteworthy, for S3 and S4 the error ellipses are no longer visible due to their small size. Therefore, in fig. 9, a zoomed-in version of the error ellipse for ![]() $\mathbf{P}_1 = [-10,25]$ is additionally provided.

$\mathbf{P}_1 = [-10,25]$ is additionally provided.

Figure 8. Visualization of ![]() $\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ (error ellipses) for different positions of

$\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ (error ellipses) for different positions of ![]() $\mathbf{P}_1$ and a fixed interferer position

$\mathbf{P}_1$ and a fixed interferer position ![]() $\mathbf{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ for all defined scenarios. Noteworthy, for S3 and S4 the error ellipses are no longer visible due to their small extent.

$\mathbf{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ for all defined scenarios. Noteworthy, for S3 and S4 the error ellipses are no longer visible due to their small extent.

Figure 9. Zoomed-in visualization of ![]() $\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ (error ellipses) of

$\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathbf{P}_1\mathbf{P}_1}$ (error ellipses) of ![]() $\mathbf{P}_1 = [-10, 25]$ and a fixed interferer position

$\mathbf{P}_1 = [-10, 25]$ and a fixed interferer position ![]() $\mathbf{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ for all defined scenarios.

$\mathbf{P}_0 = [0, 50]$ for all defined scenarios.

Several aspects are worth mentioning at this point. First, by analyzing the error ellipses for a fixed scenario, it can be seen that their extent and orientation depend on the actual position of the object ![]() $\mathbf{P}_1$. As known from other TDoA-based localization approaches, the forward scattering region close to the baseline between Txb and Rxb1 generally yields poorer localization accuracies. This can be seen, e.g., by comparing the extent of the error ellipses for