Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction, characterized by the presence of autoantibodies targeting components of the postsynaptic muscle membrane, resulting in fatigable muscle weakness. The preoperative management of patients with MG presents a clinical challenge, particularly in the context of major surgical interventions. Optimal preoperative preparation aims to reduce the risk of postoperative complications, including the possibility of a myasthenic crisis. Myasthenic crisis is generally defined as significant respiratory or bulbar muscle weakness necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilatory support. Crises can occur spontaneously due to the natural progression of the disease or be precipitated by external factors such as infections, specific medications or surgical procedures. Neurologists are often consulted as part of pre-operative planning in myasthenic patients. The aim of this paper is to review the available evidence (and its gaps) that supports current practice in pre-operative management of myasthenic patients. As will be seen, much of the data discussed in this paper is derived from the surgical literature, and may be relatively unfamiliar to neurologists.

What is the definition of postoperative myasthenic crisis or worsening?

Postoperative myasthenic crisis has been defined as either the need for mechanical ventilation support exceeding 48 hours, or re-intubation after extubation because of respiratory failure, in the absence of postoperative cardiopulmonary complications or cholinergic crisis. Reference Watanabe, Watanabe and Obama1 In patients receiving high doses of cholinesterase inhibitors, the presence of miosis, salivation, tearing, bronchorrhea and diaphoresis should prompt consideration of cholinergic crisis, although this is rarely seen in the modern era. In a multicenter study of 393 patients with MG who underwent thymectomy across six tertiary centers in Japan, no cases of cholinergic crisis were reported. Reference Kanai, Uzawa and Sato2 The authors attributed this absence to the routine discontinuation of pyridostigmine during the perioperative period.

What is the incidence and what are the risk factors for postoperative myasthenic worsening?

For almost a century, thymectomy, either for removal of thymoma or for treatment of MG, has been commonly performed in myasthenics, and essentially all the studies assessing the risk of post-operative crisis have been in this setting. In a study examining outcomes following thymectomy in patients with MG from January 1995 to December 2011, the incidence of postoperative myasthenic crisis was reported to be 12%. Reference Leuzzi, Meacci and Cusumano4 This figure reflects the immediate postoperative risk, as myasthenic crisis was specifically defined as respiratory failure due to neuromuscular weakness, occurring either in patients requiring prolonged intubation beyond 24 hours postoperatively or in those who were successfully extubated but subsequently required re-intubation or resuscitative support. Geng et al. reported a meta-analysis of 15 studies comprising 2,626 myasthenic patients undergoing thymectomy published between 2004 and 2017. The reported incidence of postoperative myasthenic crisis ranged from 6.2% to 30.3%. Reference Geng, Zhang and Wang3 At least some of this variability in reported incidence is likely due to different definitions of postoperative myasthenic crisis, with some studies characterizing it as a crisis occurring within 7 days following thymectomy, while others extended the timeframe to 30 days postoperatively or longer. Reference Geng, Zhang and Wang3

In recent years, the incidence of myasthenic crisis after thymectomy appears to have declined. While the shift toward minimally invasive techniques, such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, is often credited for the observed decline in postoperative myasthenic crisis, Reference Gritti, Sgarzi and Carrara6–Reference Huang, Su, Zhang, Guo and Wang8 a single-center study reported by Xue et al. revealed a 10% postoperative myasthenic crisis rate in 127 thymoma patients, two-thirds of whom underwent a transsternal thoracotomy. Reference Xue, Wang and Dong9 This finding underscores the multifactorial nature of the decline, highlighting the likely contributions of improved medical management and meticulous patient selection, in addition to surgical technique. Overall, recent studies estimate the current incidence of myasthenic crisis after thymectomy to be below 10%. Reference Kanai, Uzawa and Sato2,Reference Xue, Wang and Dong9,Reference Kadota, Horio and Mori10

Identifying patients at particular risk of postoperative crisis has been an objective of several studies. A history of prior myasthenic crises and the presence of preoperative bulbar symptoms appear to be independent risk factors for developing myasthenic crisis after thymectomy. Reference Kanai, Uzawa and Sato2,Reference Geng, Zhang and Wang3,Reference Liu, Liu, Zhang, Li and Qi7,Reference Nam, Lee and Kim11 Additionally, preoperative Osserman stages, Reference Watanabe, Watanabe and Obama1,Reference Geng, Zhang and Wang3,Reference Liu, Liu, Zhang, Li and Qi7,Reference Xue, Wang and Dong9,Reference Nam, Lee and Kim11,Reference Scheriau, Weng and Lassnigg12 preoperative pulmonary function Reference Kanai, Uzawa and Sato2,Reference Liu, Liu, Zhang, Li and Qi7,Reference Nam, Lee and Kim11 and higher preoperative pyridostigmine dosages Reference Kanai, Uzawa and Sato2,Reference Geng, Zhang and Wang3,Reference Liu, Liu, Zhang, Li and Qi7 have been associated with increased risk of myasthenic crisis after thymectomy. In the study by Xue et al of 127 myasthenic patients who underwent thymectomy for thymoma, the risk of postoperative myasthenic crisis was higher in patients with WHO type B2-B3 histopathology. Reference Xue, Wang and Dong9 However, the overall frequency of crisis in these 127 patients was 10%, suggesting that thymoma per se is probably not an important risk factor for postoperative crisis.

Some studies have indicated an association between high anti-AChR antibody titers (>100 nmol/L) and increased risk of myasthenic crisis after thymectomy. Reference Watanabe, Watanabe and Obama1,Reference Liu, Liu, Zhang, Li and Qi7 However, this finding has not been consistently replicated, and is difficult to reconcile with the generally accepted view that AChR antibody titers are not correlated with disease severity in myasthenics.

The risk factors for postoperative myasthenic crisis after thymectomy are summarized in Table 1. Note that the incidence of and risk factors for postoperative crisis following other types of surgery have been little studied and thus remain unknown.

Table 1. Risk factors for postoperative myasthenic crisis

To stratify perioperative risk, several predictive models have been developed based on preoperative clinical severity, bulbar involvement, pulmonary function and serologic markers. Leuzzi et al. proposed a predictive model based on a cohort of 196 patients who underwent thymectomy between 1995 and 2011. Multivariate logistic regression identified Osserman stage, body mass index greater than 28, disease duration greater than two years and the need for pulmonary resection as independent predictors of postoperative myasthenic crisis. Based on these variables, a scoring system was developed, stratifying patients into four risk groups with progressively higher rates of postoperative respiratory failure (6%, 10%, 25% and 50%, respectively).

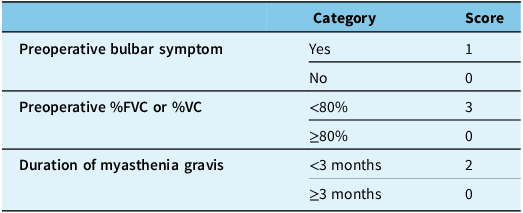

Kanai et al. subsequently introduced a clinical predictive score derived from a cohort of 393 patients, divided into derivation and validation groups. Their model incorporated three preoperative variables: reduced forced vital capacity or vital capacity (<80%), disease duration of less than three months and the presence of bulbar weakness immediately prior to thymectomy (Table 2).

Table 2. Kanai’s postoperative myasthenic crisis predictive score

This clinical score demonstrated excellent discriminative ability for predicting postoperative myasthenic crisis in both the derivation and validation cohorts. Notably, the scoring model achieved a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 83.3%, suggesting superior predictive performance compared to the Leuzzi score, which had a sensitivity of 36.8% and a specificity of 93.8%.

An important observation from the Kanai study was the association between short disease duration and increased risk of postoperative myasthenic crisis, contrary to earlier findings that implicated longer disease duration. Reference Leuzzi, Meacci and Cusumano4 A short disease duration was postulated to reflect either a rapidly progressive disease course or inadequate therapeutic control prior to thymectomy. In addition, the Kanai study cohort differed significantly from previous reports, with 66.1% of patients undergoing thymectomy within one year of diagnosis, compared to only 29% in earlier studies. The Kanai score demonstrated a high negative predictive value: when the score was low (<3 points), post-operative crisis was very unlikely. Although the positive predictive value was modest, the probability of postoperative myasthenic crisis increased proportionally with higher scores. Although these models provide a structured framework for perioperative risk estimation, their applicability across diverse patient populations and surgical settings remains to be validated in larger prospective studies.

What preoperative treatments to reduce the risk of postoperative deterioration in myasthenics are available, and what is the evidence for their efficacy?

The preoperative evaluation and management of MG patients aim to minimize postoperative complications. The process generally includes comprehensive anesthesia and neurological assessments, pulmonary function testing and, in selected cases, preoperative immunomodulatory therapy with either plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg). The use of preoperative plasmapheresis or IVIg, particularly in patients with bulbar dysfunction, was recommended by Juel Reference Juel13 and an international consensus group guideline published in 2016. Reference Sanders, Wolfe and Benatar14 The rationale for using preoperative immunotherapy is not difficult to understand, but is there evidence that it is effective?

Plasmapheresis: Given the possibility of myasthenic crisis being precipitated by surgery, the routine use of plasmapheresis prior to thymectomy in patients with generalized symptoms has been practiced for decades. However, the evidence supporting this practice is mixed. One favorable study involved a series of 51 patients undergoing thymectomy, in which Nagayasu et al. reported that none of the 19 patients who received preoperative plasmapheresis developed a crisis within 30 days of surgery, compared with 5 of 32 patients who did not undergo plasmapheresis. Reference Nagayasu, Yamayoshi and Matsumoto15 Although the baseline characteristics between the two groups were comparable, including age, sex, disease duration, Osserman classification (IIA/IIB) and preoperative medication use, the study was a retrospective analysis conducted between January 1980 and December 1997. In addition, plasmapheresis was selectively administered for preoperative stabilization, except in cases where it was contraindicated or declined by the patient, further limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding its efficacy.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Reis et al. evaluated the clinical benefits of preoperative plasmapheresis in patients with MG undergoing thymectomy. Reference Reis, Cataneo and Cataneo16 Of 317 studies initially identified, seven studies involving 360 patients were included in the final analysis, including two randomized controlled trials and five retrospective studies. Five studies involving 243 patients assessed the incidence of postoperative myasthenic crisis and found no statistically significant reduction with preoperative plasmapheresis. In a subgroup analysis based on disease severity, plasmapheresis did not reduce postoperative myasthenic crisis in patients with milder disease (Osserman II), but was associated with a reduced risk in patients with more symptomatic disease (Osserman III and IV). In addition, preoperative plasmapheresis was associated with increased perioperative bleeding. The authors judged the overall quality of evidence to be low, due to the predominance of retrospective designs, variability in patient selection and treatment protocols.

Although the benefit of preoperative plasmapheresis in reducing postoperative myasthenic crisis remains debated, some evidence suggests that it may also shorten the duration of mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit (ICU) stay. Reference d’Empaire, Hoaglin, Perlo and Pontoppidan17–Reference Kamel and Essa18 Ultimately, the literature remains inconclusive regarding the routine use of preoperative plasmapheresis in MG patients.

IVIg: The clinical efficacy of IVIg has been well established in the management of worsening myasthenic symptoms Reference Zinman, Ng and Bril19 and is considered comparable to plasmapheresis in the treatment of myasthenic crisis. Reference Gajdos, Chevret, Clair, Tranchant and Chastang20 Several studies have investigated IVIg’s value in preventing postoperative crisis, mostly using plasmapheresis as a comparator. A retrospective study by Jensen and Bril compared the efficacy of IVIg and plasmapheresis as preoperative therapy in 105 patients with MG undergoing thymectomy between 2001 and 2006. Reference Jensen and Bril21 Nine patients received IVIg and 26 underwent plasmapheresis; the remaining 70 patients were judged to not need preoperative immunotherapy. Both IVIg and plasmapheresis achieved comparable outcomes, with approximately a one-grade improvement in Osserman classification at the first post-operative clinic visit in each group. Although they did not report data on postoperative myasthenic crisis or reintubation rates, both groups had a short hospital stay of 2–3 days, implying that neither crisis nor reintubation occurred.

In another study, Pérez-Nellar et al. compared IVIg and plasmapheresis as preoperative therapies in patients with MG undergoing thymectomy. Reference Pérez Nellar, Domínguez and Llorens-Figueroa22 Among 33 patients treated with IVIg and 38 historical controls receiving plasmapheresis, no statistically significant differences were observed in duration of intubation or length of ICU stay, and no myasthenic crises occurred in either group. Huang et al. reported uneventful postoperative outcomes in six generalized MG patients who received high-dose intravenous IVIg before thymectomy, with successful extubation within 8 hours. Reference Huang, Hsu, Kao, Huang and Huang23 Neither of these studies included control patients who received neither plasmapheresis or IVIg, limiting interpretation.

There have been two randomized controlled trials evaluating the preoperative use of IVIg. Alipour-Faz et al. conducted a non-blinded randomized trial of 24 patients undergoing thymectomy, whose myasthenia was stable. Participants were assigned to receive either high-dose IVIg (1 g/kg/day for two days) or five sessions of plasmapheresis prior to surgery. Reference Alipour-Faz, Shojaei and Peyvandi24 The IVIg group had significantly shorter intubation periods; length of stay in ICU and hospital was similar in the two groups. Two patients in the plasmapheresis group had postoperative myasthenic crisis (not further defined) secondary to pneumonia. In contrast, Gamez et al. performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 47 MG patients undergoing various surgeries, including thymectomy. Reference Gamez, Salvadó and Carmona25 Patients were randomized to receive either IVIg (0.4 g/kg/day for five days) or placebo prior to surgery. The incidence of postoperative myasthenic crisis was low, with only one event occurring in the placebo group, and no significant differences were observed between groups in intubation time, recovery room duration, postoperative complications or hospital length of stay. The authors concluded that routine preoperative IVIg is not necessary for well-controlled MG patients (preoperative quantitative myasthenia gravis score<8 and preoperative forced vital capacity less than 70% of predicted).

In addition to limited evidence, both plasmapheresis and IVIg have some risks and potential complications. Plasmapheresis is invasive, resource-intensive and can be associated with complications such as catheter-related infections, hypotension, bleeding disorders and citrate reactions. Reference Gajdos, Chevret, Clair, Tranchant and Chastang20,Reference Ghimire, Kunwar and Aryal26 IVIg, while less invasive, carries risks, including thromboembolic events, fever or chills, aseptic meningitis and infusion-related reactions, and may be contraindicated in patients with IgA deficiency. Reference Ghimire, Kunwar and Aryal26,Reference Dalakas27 Moreover, both treatments are relatively costly and may not be readily available in all healthcare settings.

Conclusion

Postoperative myasthenic crisis remains an important issue in the management of myasthenia gravis, although its incidence has declined significantly in recent years, with most contemporary series reporting rates below 10%. This decline is likely due to improved perioperative care, meticulous patient selection and increased use of minimally invasive surgical techniques. Several validated predictive tools, such as the Leuzzi and Kanai scores, are available to estimate perioperative risk based on disease severity, bulbar involvement, pulmonary function and serologic markers. These models offer a structured approach to risk stratification and can help identify patients who may benefit from additional preoperative interventions.

Although there is a good theoretical rationale for preoperative plasmapheresis or IVIg, current evidence (albeit flawed) does not support their routine use. In addition, when the cost, logistical challenges and potential complications are considered, we conclude that routine preoperative plasmapheresis or IVIg should be discouraged. Nevertheless, there are likely patients in whom preoperative plasmapheresis or IVIg is advisable. Published expert opinion recommends these treatments for patients with “bulbar or generalized weakness” Reference Juel13 or with “significant bulbar dysfunction.” Reference Sanders, Wolfe and Benatar14 This expert opinion seems reasonable, but we advocate a more evidence-based approach, and instead recommend that high-risk patients be identified using the validated risk scores described above, and that preoperative plasmapheresis or IVIg be reserved for such patients. A randomized controlled trial of this approach would be ideal but is likely impractical; prospective validation using a multicentre registry would be feasible.

Author contributions

SA: literature search, initial and final drafts of manuscript.

CC: concept of project, initial and final drafts of manuscript.

Funding statement

This work did not receive funding support.

Competing interests

SA and CC report no conflicts of interest or competing interests.