‘Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall’

Proverbs 16:18–King James Version (KJV)Introduction

The research question

This paper proposes an unorthodox thesis. It disputes the supposition of received theories. Received theories include present-bias approaches (e.g., Strotz, Reference Strotz1955; Laibson, Reference Laibson1997; O’Donoghue & Rabin, Reference O’Donoghue and Rabin1999), the multiple-self framework (Fudenberg & Levine, Reference Fudenberg and Levine2006; Thaler & Shefrin, Reference Thaler and Shefrin1981), and the dynamic consistency theory (Gul & Pesendorfer, Reference Gul and Pesendorfer2001, Reference Gul and Pesendorfer2004a, Reference Gul and Pesendorfer2004b). Despite their differences, received theories basically suppose that temptations are the primitives while the decision maker (DM) adopts rules to control them. This paper proposes the contrary: rules rules come first, while temptations can be defined only vis-à-vis rules. This unorthodox thesis raises the Question about the origin of rules. One major part of this paper is devoted to answering this question.

The proposed thesis basically rearranges two basic phenomena (temptations and rules) that must be the fundamental elements of any theory of temptations (weakness of will). The research Question concerns the entry point:

Research Question: Should a theorist commence with rules to explain temptations? Or should she follow received theory, i.e., commence with temptations as the primitives and consequently explain rules as the attempt to control those primitives?

The proposed entry point, i.e., rules, allows researchers to provide endogenous accounts of temptations. Rules can be regarded as a kind of institution or constitutional design. There are two kinds of such rules or constitutional designs. The first are rules or constitutional designs that involve individual behaviour vis-à-vis future self: the DM designs rules where the aroused temptations concern over-consumption (i.e., under-saving). The over-consumption undermines the wellbeing of the future self. The second kind are rules, or, more commonly recognised, constitutional designs that involve individual behaviour vis-à-vis contemporaneous others: the DM designs rules where the aroused temptations concern also over-consumption. However, the over-consumption here undermines the wellbeing of pertinent others, i.e., cooperators that the DM has made promises to.

As explained elsewhere (Khalil, Reference Khalil2020), both acts of over-consumption are analytically identical. Although this thesis is not the subject of this paper, it can be a source of confusion. The confusion is expected given that the claim that both kinds of over-consumption are identical is contrary to textbook economics, where it models intertemporal allocation (present self vis-à-vis future self) differently from how it models the prisoner’s dilemma game (present self vis-à-vis contemporaneous others). While it models the DM in intertemporal allocation as concerned about the wellbeing of their future self, it models the DM in the prisoner’s dilemma as concerned only about the wellbeing of their own self. As explained below, there is a mechanism of punishment of cheaters in intertemporal allocation that is similar to the mechanism in the prisoner’s dilemma game. If we are convinced that the two acts of over-consumption or cheating are isomorphic, it should not be surprising that the proposed theory, which focuses mostly on over-consumption that undermines the wellbeing of the future self, should also be a theory regarding over-consumption that undermines the wellbeing of pertinent contemporaneous others.

The proposed claim of isomorphism is not new. A few theorists and philosophers (e.g., Elster, Reference Elster2000, pp. 88–174; Teubner & Beckers, Reference Teubner and Beckers2013; Waluchow & Kyritsis, Reference Waluchow and Kyritsis2023) have noted that the set of constitutional rules regarding individual liberties is the condition that DMs, theoretically behind the veil of ignorance, demand prior to becoming members of the respective political community. The demand for such constitutional rules entails that, irrespective of the faction that controls the office of the executive or the legislature, no faction can squash rights that are ex ante dear to all.

Indeed, this paper uses the principal-agent framework, relying on the isomorphism thesis, namely, reneging on promises made to contemporaneous others amounts to succumbing to temptations. That is, reneging is analytically identical to failing to live to promises made to the future self.

This paper focuses only on temptations, a major phenomenon that has captured the interests of many behavioural economists (see Camerer, Reference Camerer2003; Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Loewenstein and Rabin2004; Dhami, Reference Dhami2017, Reference Dhami2025). There are many other important phenomena that have also captured the attention of behavioural economists. However, they fall outside the scope of this paper. These phenomena include habits (e.g., heuristics and routines), fairness (e.g., the ultimatum game), loss aversion, the income-happiness paradox (Easterlin paradox), the endowment effect, and framing effects. This range does not include deviations from rationality arising from anxiety, such as procrastination, the certainty effect (Allais paradox), and the ambiguity effect (Ellsberg paradox). Indeed, it is hard to keep track of all these phenomena, not to mention putting them into an efficient taxonomy (see Khalil, Reference Khalil2025a, Reference Khalil2025b).

Definitions: Temptations, rules, institutions, constitution

When the DM succumbs to temptations, the DM succumbs to weakness of will. The consequent consumption is by definition suboptimal. Such consumption is usually over-consumption, i.e., where the DM’s weakness of will undermines the wellbeing of their future self (or the wellbeing of pertinent contemporaneous others). The consumption can also be suboptimal in the opposite direction, namely, where the DM succumbs to stiffness of will. This paper does not discuss under-consumption, i.e., choices motivated by stiffness of will.

It suffices, however, to highlight two examples of stiffness of will: (i) miserly behaviour in the case of intertemporal allocation where the future self is the focus (see Khalil, Reference Khalil and Altman2017a); and (ii) sentimental foolishness exhibited in suboptimal acts of helping others in the cases of cooperation where pertinent others are the focus (see Khalil, Reference Khalil1999).

To illustrate temptations in the sense of succumbing to over-consumption, let us imagine a model of a single DM who is planning in the present, at t1, consumption and saving for fifty periods. In period t50, she expects to die at the end and, hence, plans to bequeath the invested capital to her daughter. She cares about the daughter’s wellbeing with the same intensity as she cares about her own wellbeing at t1. In this model, the DM has well-defined preferences regarding present and future consumption, a certain capital at t1 that equals, say, $1.1 million, a uniform discount rate of future consumption that equals, say, 10%, and a constant investment rate of return per period that equals the discount rate. The DM has neither an income from labour nor from rental property. At the beginning of t1, the DM decides to consume $100,000 and to save $1 million. At the beginning of t2, she receives the investment return ($100,000) and consumes it while keeping the $1 million invested. Indeed, the optimal consumption in each period is $100,000. At t50, she dies at the end of the period, as she expected. The daughter inherits the $1 million. Assuming that the daughter has the same preferences and budget constraint, she would also choose the optimal consumption bundle, $100,000 at t51 and all following periods, assuming that she also has one offspring.

Temptation is defined here as the deviation of the DM (or her daughter) from the optimal consumption plan, $100,000 per period. It is usually the case to define weakness of will as succumbing to ‘temptation’ of consuming any amount at any period that is above $100,000. However, it is analytically correct, arising from ‘stiffness of will’ (Khalil, Reference Khalil and Altman2017a), to consider any consumption below $100,000 to be also succumbing to ‘temptation’.

Regarding rules, they amount to informal and formal guidelines at the level of the DM as well as the level of the collective. At the collective level, they are cultural norms, government regulations, laws, and rights placed in constitutions. Such rights usually pertain to limiting the supremacy of one actor, subjecting the declarations of war, the raising of taxes, and other major policies to the careful scrutiny of other actors within the state.

As such, the term ‘rules’ denotes in this paper one kind of institution, namely, the self-commanded restraints that decision makers (DMs) impose on themselves à la Adam Smith’s (Reference Smith, Raphael and Macfie1976) concept of ‘self-command’ (see Khalil, Reference Khalil2010). This paper does not study ‘institutions’ in the sense of habits and laws designed to define and regulate property relationships, precautions against uncertainty, moral limits of contracts, the functions of the judiciary, or the duties of the state in encouraging saving, innovations, and economic development. These types of institutions have been studied by Williamson (Reference Williamson1985), North (Reference North1990, Reference North1991), and Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2015; see Khalil, Reference Khalil2012, Reference Khalil2013). The focus of this paper is narrower than the focus of these authors.

Once we study these authors and find the judicious balance between privately and publicly owned property and further specify the informal norms, laws, and regulations associated with such property relationships, what is the source of succumbing to temptations? Why do people tend to violate the institutional foundations of the economic society? Do the rules, in the sense of self-commanded restraints, arise in light of preferences conceived as primitives – or vice versa?

The paper simply does not study what determines the judicious institutions à la Williamson, North, or Hodgson. It takes them as givens. On the basis of these givens, it asks a Question corresponding to Smith’s self-command: Do we have self-commanded restraints (rules) because of human predilection toward tantalising preferences, or vice versa?

The scope of this paper is even more narrow. It does not discuss two variants of the mentioned self-commanded restraints. The first variant that this paper ignores is ‘general rules’ in Smith’s (Reference Smith, Raphael and Macfie1976: 156–161) sense, namely, as principles that DMs impose on themselves to avoid self-deception. Self-deception, following the definition of Smith, is the technology that DMs employ to masquerade their deviations from the self-commanded restraints (see Khalil, Reference Khalil2009, Reference Khalil2016, Reference Khalil2017b; Khalil and Vasudevan, Reference Khalil and Vasudevan2025). The second variant that this paper ignores is formal ‘general rules’, i.e., regulations and laws. This paper does not focus on when informal ‘general rules’, i.e., ‘norms’, become formal ‘general rules’. This analysis involves a research Question outside the scope of this paper.

Received theories mentioned at the outset also ignore ‘general rules’ – the principles that help DMs avoid self-deception – as this paper does. These theories study ‘rules’, i.e., self-commanded restraints to control temptations as technologies designed to amend human partiality toward present consumption.Footnote 1 Despite their differences, they effectively conceive temptations as primitives, as ‘present-bias preferences’.Footnote 2

The holiday license paradox

For received theories, present-bias preferences entail that DMs choose a consumption of suboptimal goods only because they are situated in the present, i.e., they would not choose them excessively if they were situated in any period in the future.

To state the received theories succinctly:

Received Theories: DMs suffer from present-bias preferences that pose temptations; in turn, DMs adopt self-imposed rules, ranging from commitments to so-called ‘pre-commitments’, to prevent succumbing to temptations. That is:

Temptations → Rules

This paper offers a radical proposal: we need to reverse the order. At the first moment, DMs adopt self-imposed rules. What they feel as temptations appears only at the second moment, only in reference to the self-imposed rules. That is, received theories simply place the proverbial cart in front of the horse.

The motivation behind this radical proposal is to solve a contradiction – an anomaly that is not noted in the received literature. This paper coins it the ‘Holiday License Paradox’:

The Holiday License Paradox: DMs erect constraints to ward off stand-alone consumptions from, say, the tempting Y set, i.e., those deemed suboptimal. So, ceteris paribus, bundles of the Y set are always ‘bads’, i.e., suboptimal. Failing to save or exercise is always ‘bad’. On the other hand, in order to enhance wellbeing, DMs erect institutions that license limited choices of bundles from the Y set. How come, given the ceteris paribus condition, DMs consider the Y set to be always suboptimal but allow choices from the Y set as exceptions, like holiday licences?

Holiday licences allow DMs to splurge during vacations, e.g., to overeat, under-exercise, and so on. Holiday licences are simply licences to cheat, but cheat within a boundary. DMs observe holiday licences in many cultures. Indeed, holiday licences are evident in almost all societies, contemporaneous and historical. From a quick survey of the sociological and anthropological literature (e.g., Bakhtin, Reference Bakhtin1965; Dietler and Hayden, Reference Dietler and Hayden2001; Falassi, Reference Falassi1987; Goody, Reference Goody1982), a researcher would be surprised to find stable or everlasting puritan societies that have managed to totally suppress indulgence that violates the rules.

There are many versions, forms, and explanations of events that remotely or closely resemble the holiday licence phenomenon that this paper identifies. This paper cannot discuss the phenomenon in all its aspects and various forms (see Khalil, Reference Khalil2026c). At its most elemental level, the holiday licence phenomenon is paradoxical. Given that circumstances have not changed, why would humans consume in holidays bundles of goods that are deemed to be bad in all instances?

Indeed, the proposed key thesis of this paper is an attempt to solve the holiday license paradox. To solve the paradox, we need to rearrange the two basic elements (temptations and rules) in contradistinction to the arrangement in received theories of weakness of will. The identified paradox stems from engaging theory with history. It emerges from engaging rational choice theory and optimal rules, on the one hand, with the historical record of most societies insofar as they set up holiday licences while knowing that such licences undermine the optimal rules, on the other hand.

This paper’s methodology of engaging theory with history can be traced back to Ibn Khaldûn. For example, Ibn Khaldûn (Reference Khaldûn1967, vol. 2: 103–111) maintained that the prince or the sultan should avoid predatory public finance: a reasonable and stable tax rate can ensure greater public revenue than a capricious and high tax rate. He enlisted his historical accounts of the debacles of many political dynasties in history in light of a theory of public finance that modern economists characterise as ‘predatory’ (e.g., Olson, Reference Olson2000; see Khalil, Reference Khalil2007a, Reference Khalil2007b).

Similar to Ibn Khaldûn’s methodology, this paper uses holiday licences in historical and modern societies to highlight a dilemma that faces standard, neoclassical rational choice theory insofar as it commences with tempting preferences. For such a theory, the decision strategy is clear: at each point, the DM should abide by rules (pre-commitments) to avoid splurging, overeating, and under-exercising. That is, at first approximation, the DM should lead a puritan lifestyle (e.g., Fitouchi et al., Reference Fitouchi, André and Baumard2023). However, evidently, DMs embrace holiday licences, i.e., violating the rational puritan lifestyle.

Let us grant that the received starting point faces the holiday license paradox. Still, why does reversing the entry point, i.e., starting with rules, promise to solve it so easily? Once this paper uncovers below the origin or source of the adopted rules, it becomes easy to realise that such origin allows the DM to design rules and, simultaneously, design with ease the exceptions, i.e., the holiday licences.

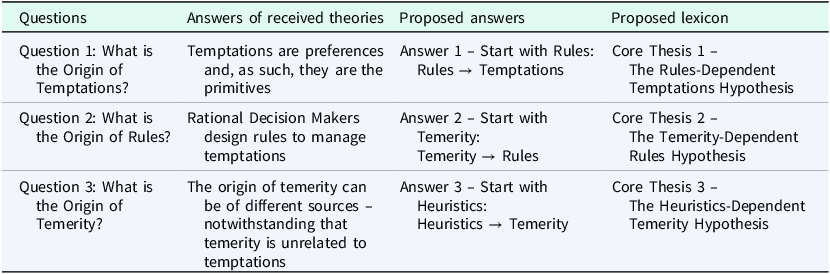

As Table 1 sums up, the radical proposal, called below core thesis I, faces a question: if rules are not the products of tempting preferences, what is the origin of rules? In response, this paper advances core thesis II: the origin of rules is temerity in the sense of overconfidence – defined as the tendency to form unfounded beliefs about the states of nature (environment) to rationalise reckless behaviour.Footnote 3 However, in turn, core thesis II faces another question: what is the origin of temerity? In response, this paper advances core thesis III: the origin of temerity is heuristics, i.e., deep-seated machinery of temerity-guided beliefs needed in life-and-death decisions. However, heuristics may generate excessive temerity, prompting DMs to adopt rules to restrain it.

Table 1. Questions, received answers and proposed answers

The paper discusses, in three sections, core thesis I, core thesis II, and core thesis III, respectively. It proceeds to identify the basic motive for the adoption of rules in a preliminary model. The last section concludes. This paper’s contribution resides in the three core theses and, further, the preliminary model that explains the problem with temerity.

A separate online link (https://eliaskhalil.com/download/Appendices-Rules-and-Temptations.pdf) contains three pertinent appendices. Appendix 1 distinguishes temptations from addictions, on the one hand, and the certainty effect, on the other hand. Appendix 2 offers a critical review of different theories of temptations, including rational addiction theory, dynamic inconsistency, the multiple-self approach, dynamic consistency, and dual process theory. Appendix 3 lists three major payoffs of the proposed theory.

Question 1: What is the Origin of Temptations?

The Answer: Start with Rules

The radical proposal, called here core thesis I, can be expressed tersely:

Core thesis I (The Rules-Dependent Temptations Hypothesis): Tempting preferences cannot be the entry point. The entry point should be the rules, the set or restraints. That is,

Rules → Temptations

The core thesis I, ‘the rules-dependent temptations hypothesis’, entails that tempting preferences can be identified only in reference to rules, where such rules form a part of the set of constraints. That is, tempting preferences cannot stand-alone preferences. They originate from the already set-up rules.

The core thesis entails that the world of temptations is monist: there is a single phenomenon called ‘temptations’, and, hence, it behoves us to develop a single theory: either temptations are primordial while rules appear later or, as this paper argues, rules appear prior to temptations. However, what if the world of temptations is non-monist – what if we have two different phenomena of temptations? The first, call it the ‘Ten Commandments’ phenomenon of the Old Testament, is the one investigated in this paper: there are rules that exist for some reason, and only against such rules can we identify temptations. The second, call it the ‘Ulysses’ phenomenon, where Ulysses tries to fight off the tempting songs of the Sirens (Elster, Reference Elster2000), is the supposition of an intense taste for songs or chocolate that acts as the primordial entity. This supposition means that the DM sets up rules to command excessive consumption.

However, given that we need to define ‘excessive consumption’, the Ulysses phenomenon inescapably reverts to the Ten Commandments phenomenon. Let us start with a DM who has an intense taste for chocolate. Still, the DM has to decide what is the optimum normal consumption – above which would be ‘excessive consumption’. Let us say, given the DM’s set of preference, the optimum is 50 grams per day. Let us say that there is a special sale for one day where the optimum for the DM under focus becomes 70 grams per day. The DM finds that if he, given the special sale, consumes 70 grams, he cannot stop and actually consumes 150 grams. To prevent such suboptimal consumption, the DM sets up a 50-gram-per-day rule that makes him disregard special circumstances such as special sales. The desire to consume more, as in the case of special sales, would be ‘a tempting option’.

Thus, to define a ‘tempting option’, we must already have in place what is the optimum or, what is more common, the rule that expresses the optimum in average (normal) circumstances.

A defence of rules

How should we reconcile the rational decision strategy of leading a puritan lifestyle with the actuality of holiday licences that are anti-puritan? We could reconcile rationality with holiday licences if we can theorise that when people design rules, they also can easily design exceptions, i.e., holiday licences. This would be easy to theorise only if we suppose that rules precede temptations. However, this leads to Question 2.

Question 2: What is the Origin of Rules?

The Answer: Start with Temerity

Given core thesis I, what is the origin of rules? This paper postulates that DMs design rules to regulate temerity:

Core thesis II (The Temerity-Dependent Rules Hypothesis): DMs adopt the self-imposed rules in order to manage temerity. That is,

Temerity → Rules

Core thesis II, ‘the temerity-dependent rules hypothesis’, traces rules to temerity. This means that rules can be identified only in reference to temerity.

This paper defines ‘temerity’s the cavalier attitude that lowers one’s reading of the risks regarding non-auspicious outcomes – i.e., increases the probabilities of fortunate states of nature – below what the facts suggest. Such a cavalier attitude is the basis of the formation of unfounded beliefs about the states of nature. Such an attitude leads the DM to take actions that she would not have taken if she had read the facts objectively and, consequently, held fact-based prior beliefs about the states of nature. Examples of temerity include reckless driving based on downplaying the likelihood of accidents, overeating based on dismissing the likelihood of ill health, and failing to take extra precautions on sea voyages based on lowering the risk of storms.

In contrast, we may reserve the term ‘prudence’ to denote an attitude that generates properly formulated risk assessments, leading to well-founded beliefs.Footnote 4

Once we see temerity, especially excessive temerity, rather than tempting preferences, at the origin of rules, we can solve the holiday licence paradox as promised. If we conceive rules as a function of excessive temerity, the DM can modify the rules during holidays, i.e., allow for licences to over-consume, without worry. After the holiday, the DM can return to the rule, i.e., avoid overconsumption. The holiday acts as a known limit for the overconsumption and, hence, preserves the integrity of the rules. Put plainly, the DM tells the self, ‘I can splurge and take risks, but this activity is limited to holidays and vacations’. In this manner, the episode of overconsumption will not distort the prudent rule, i.e., will not lead to cavalier or temerarious beliefs about the environment.

In contrast, if we travel along the received theories – i.e., conceive rules as a function of present-bias preferences – the DM should not modify the rules: at every instance the DM should avoid the suboptimal choice. As an example, the rule ‘do not under-save’ must be true in every instance – except when circumstances change as in the case of the emergency of saving a life. The holiday licence is far from an emergency to save a life. The DM cannot find it useful to violate the rule in some instances. Thus, it is difficult for received theories to explain holiday licences.

In response, received theories may resort to ad hoc qualifications – which effectively weaken their explanatory apparatus (Khalil, Reference Khalil1989). One qualification is the reasoning that holiday licences are ‘exceptions’ to habits. As one may break away from a habit under an extraordinary circumstance, one may assign a holiday as an exception. Such reasoning regards the continuous avoidance of temptations to be burdensome. When the DM adopts a rule of abstemiousness, she also adopts an exception, i.e., a holiday that allows the self to ‘sin’. When the DM yields to a temptation, it allows the DM to release a repressed desire that otherwise can wreak havoc.

In this explanation, the rule, with its respective holiday licence, is on average optimal. However, this explanation portrays the rule regarding temptations as a ‘habit’. While the rule might become habitual, it does not mean its origin (insofar as it is about temptations) is the same as the origin of habits. Habits, as the term is defined here, are not about rules to combat temptations. Habits include heuristics that humans form as first impressions or generalisations. Habits also include routines such as taking the same route home or brushing the teeth. As argued in Appendix 2 (see also Khalil, Reference Khalil2022; Khalil and Amin, Reference Khalil and Amin2023), DMs adopt habits (ranging from heuristics to routines) to minimise the cognitive and physiological cost of deliberation of each instance.

Indeed, dual process theory explains habits as the manifestation of mental economy (e.g., Grayot, Reference Grayot2020; Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). This theory proposes that decisions or choices proceed along either a fast process, called ‘System 1’, or a slow process, named ‘System 2’. This is not the paper to discuss the origin of the two systems–not to mention the basis of the switching between them (Khalil, Reference Khalil2025c).

It is sufficient to state that the basis that gives rise to habits differs from the basis that originates rules regarding temptations. (Notwithstanding, as shown below, this paper relies on dual process theory to explain temerity, which is another phenomenon). We cannot explain the holiday licence phenomenon as ‘exceptions’ to habits – given that rules regarding temptations are not related to the difference between System 1 and System 2 (dual process theory).

To recapitulate, with core thesis II, the cheat days or holiday licences phenomenon is no longer an anomaly. The phenomenon is only an anomaly in reference to received theories – i.e., theories that commence with suboptimal, present-bias preferences.

A defence of temerity

To recapitulate, DMs adopt rules to regulate temerity, which this paper coins the ‘temerity-dependent rules hypothesis’. That is, rules do not stand alone. They can only be defined in reference to temerity.

This paper postulates ‘temerity’ as the origin of rules, as it is the most convincing origin that can easily explain, besides rules, the exceptions to the rules, i.e., holiday licences. That is, the specified origin is a successful hypothesis if it carried the two tasks at first approximation, i.e., without ad hoc assumptions and tortured qualifications.

Temerity is a cavalier attitude that leads the DM to exaggerate the likelihood of auspicious outcomes. This exaggeration takes place without the DM being necessarily conscious of his misguiding attitude. Such an attitude can be expressed in the asymmetrical reaction to outcomes. For example, let us take two outcomes that are the products of two choices, where each choice requires the same effort. However, the outcomes differ: one is successful while the other is not. The difference is the result of two exogenous shocks of equal probability. If the outcome is successful, the DM attributes the success more to skill/effort than to luck. If the outcome is unsuccessful, the same DM attributes the failure more to luck than to skill/effort. We can conclude that these DMs have a temerarious attitude, as they tend to inflate their ability – not realising that ability is not in question.

Let us take a game of die tossing, where the die is fair. The DM gains $1 when she tosses an even number and loses $1 when she tosses an odd number. The expected value is zero. A risk-neutral DM would be ready to pay no more than zero to participate in this game. However, if the risk-neutral DM is conceited, i.e., operating on the belief that ‘I am special’ or ‘I feel lucky today’, she would be ready to pay a positive amount, say $10 for 100 rounds, based on the belief that, ex ante, there will be at least 60 times out of the 100 rounds where the toss generates an even number.Footnote 5

In everyday examples, if the DM was lucky in guessing the outcome of a roulette spin, he would upgrade the likelihood of an outcome in the following spin, thinking that ‘it is my lucky day’. However, if the DM was unlucky in the first round, he would not symmetrically downgrade the likelihood of an outcome in the following spin. Temerarious DMs seem eager to build a causal story where it neglects that outcomes, following Galton’s law, regress to the average (see Galton, Reference Galton1889; Mulligan, Reference Mulligan1999).

In his light, temerity is the basis of unfounded beliefs in a specific sense:

Temerity: When DMs over-recognise the role of luck when outcomes are negative while under-recognising the role of luck when outcomes are positive, such DMs operate according to a cavalier attitude, temerity, i.e., a belief that presents the likelihood of success higher than justified by ex ante evidence.

In contradistinction to temerity, when DMs are motivated by prudence, they uphold objective beliefs about the likelihood of success, i.e., beliefs supported by available information.

We can use the terms ‘arrogance’ and ‘smugness’ as equivalent to ‘temerity’. However, we should not use the term ‘optimism’ as equivalent to ‘temerity’ – contrary to how some authors use the term (e.g., Sharot, Reference Sharot2011). Optimism has the connotation of being motivated by a positive outlook toward life, ever thankful and ever hopeful, even in dire catastrophes and circumstances (Khalil, Reference Khalil2023). Optimism suggests transcendence, i.e., going beyond everyday material constraints, which temerity does not suggest.

We may use the terms ‘overconfidence’ or ‘over-estimation’ as equivalent to ‘temerity’. However, these terms suggest narrower scope than ‘temerity’. They limit the issue to the assessment of ability, while ‘temerity’ suggests both assessment of ability and beliefs about the states of nature.

Specifically, as Moore and Schatz (Reference Moore and Schatz2017) clarify, while the term ‘overconfidence’ has three separate meanings in the literature, they all about the assessment of ability. The first meaning is the ‘overestimation’ of an ability, as in solving word puzzles; the second is the ‘overplacement’ of one’s ability vis-à-vis the ability of a group, as in automobile driving; and the third is the ‘overprecision’ in one’s belief that she is correct.

In any case, economists generally do not distinguish overconfidence in the narrow sense of assessment of ability, on the one hand, and temerity in the broad sense that includes beliefs about the states of nature, on the other hand. For example, Bhaskar and Thomas (Reference Bhaskar and Thomas2019) detect temerarious attitude by measuring the extent that DMs exaggerate their ability.Footnote 6

The task of separating temerity from overestimation of ability is difficult. As noted above, the DM is usually not cognisant of her own temerity (see Barber and Odean, Reference Barber and Odean2001; Kőszegi, Reference Kőszegi2006). This is similar to self-deception: temerity (as well as self-deception) would vanish once the DM recognises the attitude as such. Probably the DM senses his temerity as if it is about ability rather than the mistaken exaggeration of luck.

Question 3: What is the Origin of Temerity?

The Answer: Start with Heuristics

Given core thesis II, what is the origin of temerity? This paper postulates that DMs adopt temerity as a survival strategy:

Core thesis III (The Heuristics-Dependent Temerity Hypothesis): DMs adopt temerity as a habit in the sense of a heuristic to enhance survival in critical situations. That is,

Heuristics → Temerity

Core thesis III, ‘the heuristics-dependent temerity hypothesis’, stipulates that, ultimately, the entry point is heuristics.

This paper maintains that temerity is an optimal heuristic in the game of life. DMs take risks not only in everyday decisions about how to drive, what to buy, and whether to accept a job offer. DMs also have to take risks that have definite outcomes with regard to staying alive. When DMs face critical choices in life-and-death situations, they face binary outcomes: staying alive or dying. Consequently, DMs find it better to err on the side of recklessness, i.e., temerity, than to err on the side of the opposite, i.e., prudence in the sense of well-founded caution (see Khalil, 2026b).

A defence of heuristics

Temerity-as-heuristics are on average optimum. That is, heuristics do not always engender the correct responses. A heuristic-based action might produce, ex post, a negative outcome. The optimum heuristics are destined on many occasions to go amiss, i.e., to become what Kahneman (Reference Kahneman2011) calls ‘biases’ or ‘cognitive illusions’. Even with mistakes, DMs cling to the biases (cognitive illusions) as long as they are ex ante optimum, i.e., on average optimum. They would be on average optimum because of bounded rationality, where DMs adopt heuristics to economise on cognitive cost (see Khalil, Reference Khalil2022; Khalil and Amin, Reference Khalil and Amin2023).

Temerity is an optimum heuristic given that it is highly possible for the DM to face critical situations. Therefore, the DM is ready to tolerate inevitable ex post errors of the optimum heuristic. However, these errors can be excessive. Therefore, DMs set up rules to restrain temerity, to keep it within reason. Such rules include a limit on consumption every instance of consumption.

However, DMs can do even better. They can improve wellbeing by adopting exceptions (holiday licenses) to the rule, i.e., allowing overconsumption for a specified period.

The model

A generalised principal-agent framework

This paper has so far defended three core theses, culminating in the temerity-dependent rules hypothesis. This defence is not axiom-based. This paper will make suggestions in this direction by proposing a framework, while leaving future research for a full-fledged axiom-based model of the proposed hypothesis.

The proposed framework promises to keep track of the expected cost-and-benefit of risks in a principal-agent model. In this model, the likelihood of success must be less than 100%. Otherwise, the model is useless. However, we need to modify the model considering the temerity-dependent rule hypothesis. In the modified model, the principal and the agent are the same person, not even separated by a time period. That is, we do not even have two selves, each living in a different period, à la the multiple-self approach (e.g., Fudenberg and Levine, Reference Fudenberg and Levine2006; Thaler and Shefrin, Reference Thaler and Shefrin1981).

In the proposed generalised model, the agent is the DM, while the principal is the judge that knows the true probabilities. The principal (judge) resides within the person’s breast, resembling Adam Smith’s impartial spectator (Smith, Reference Smith, Raphael and Macfie1976; Khalil, Reference Khalil2010, Reference Khalil2017c). The principal (judge) keeps track of the prior. In contrast, the DM has a temerarious attitude: the DM tends to exaggerate the likelihood of success. If the DM becomes aware, as a result of experience, of how to update properly the principal’s prior, then the DM becomes a sophisticate. In this case, there would be absolutely no difference between the principal and the agent. We would have the standard rational DM that inhabits textbook economics.

This modified model is more general than the standard principal-agent model in an additional way. The standard model is limited in one important sense. It does not consider that the agent, when hired, must feel obligated to perform the different tasks demanded by duty, i.e., what she has promised the principal to deliver. As stated at the outset (Khalil, Reference Khalil2020), for standard economists it is non-conventional, if not strange, to conceive the interaction in a prisoner’s dilemma setting as constrained by duty toward pertinent others – analytically similar to duty toward the future self. It is proposed here that the rational choice of players in the prisoner’s dilemma game is cooperation – at least consistent with the standard economist’s proposition that the rational choice of the present self in intertemporal allocation is cooperation (see also Khalil, Reference Khalil2026a).

This conception, however, should not be regarded as strange. Standard economists propose that the present self must feel obligated to exercise, save, eat healthy, and so on, i.e., do what it sees as the best interest of the future self while also taking care of the best interest of the present self. They should, to remain consistent, propose that players in prisoner’s dilemma games must also feel obligated to keep the ex ante promises made to the other players.

If we suppose that the present self is motivated by duty toward the interest of the future self, why not extend such biological unity to social unity, i.e., equally suppose that the employee/agent is obligated to the employer/principal? Why should a thinker impose a metaphysical assumption, namely, that the biological unit (present and future selves) trumps the social unit (employee and employer selves)? Put differently, if a thinker is ready to suppose some kind of obligation between their present and future selves, why refuse to extend the same kind of obligation between employee and employer selves?

In the proposed generalised model, the way the DM can be an employee deciding whether to shirk on the job or not is analytically the same as the DM can be a present self deciding whether to cheat the future self or not. This isomorphic nature of the decision – i.e., isomorphic across two contemporaneous people or across two selves belonging to the same biological person – has many applications that cannot be discussed here (see Khalil, Reference Khalil2015, Reference Khalil and Altman2017a).

With the proposed modified model, the ‘agent’ and the ‘principal’ are the same person, where the agent is the present self while the principal is the future self. If the DM/agent (i.e., present self) decides to shirk, the principal (i.e., future self) would suffer. The standard principal-agent model is a special case, as it imposes the additional restriction that the two are separate persons. This restriction permits it to escape the issue of obligation, namely, to suppose that an employee/DM would not feel obligated toward the employer/principal, while supposing that the present self feels such obligation toward the future self. With this restriction, the standard model supposes that cheating impacts the principal negatively but only impacts the cheating DM negatively if he gets caught.

The proposed generalised principal-agent model, where the principal and the agent are the same person, allows us to clearly comprehend the choice of ‘overeating’ or ‘undersaving’. The party that can be potentially harmed is the adjacent future self: such a self would potentially feel some discomfort by the suboptimal decision of the current self. That is, the generalised principal-agent model is nothing but individual decision-making, whereas the DM may take the gamble and enjoy an extra piece of cake or less consumption, given the likelihood that the future adjacent self would suffer.

In the proposed generalised principal-agent framework, the decision to eat or to save is analytically the same as the decision to shirk on the job. Both are gambles that the DM is ready to undertake, given the likelihood of success. In fact, the adjacent self in the decision of eating or saving becomes the principal in the standard model if such an adjacent self is conceived totally as separate. Then, the current self would only have to worry about the punishment, given the likelihood of success. This worry is the same irrespective of whether the probable punishment is meted out by an employer or by the future self via a special mechanism.Footnote 7

From the generalised principal-agent framework to the power of taxation

The proposed principal-agent framework can be generalised in a different way. The proposed theory – namely, DMs set up rules that limit temerity regarding over-consumption and other intertemporal allocations – is easily generalisable to constitutional rules regarding public finance. One of the major concerns of public finance is the power of taxation and its possible predatory practice by the king or sultan – as alluded to above regarding Ibn Khaldûn’s methodology (Reference Khaldûn1967, vol. 2: 103–111).

The concern with public finance differs from the issue of constitutional rules regarding civil liberties discussed at the outset. Regarding public finance, the issue is – e.g., in light of North and Weingast’s (Reference North and Weingast1989) study of the English Glorious Revolution in 1689 – who should have the power to tax: the executive (i.e., the king) or the parliament? With the change of the constitution as a result of the Glorious Revolution, the parliament was able to wrest the power to tax from the hands of the king. As North and Weingast show, the new constitutional rule ushered in fruitful institutions that encouraged investments, given that investors do not have to fear the predatory actions of the executive.

However, why is the executive more prone to predatory taxation than the parliament? That is, why do kings, more often than their respective parliaments, fall victim to excessive temerity? Given that kings cannot be easily removed, they are more prone to raise taxes under some excessive temerarious beliefs, such as that extra taxation would not lower investments and, as a corollary, undermine long-term prosperity. Given it is much easier to remove the parliamentarians by one method or another, they are sensitive to public opinion. Hence, they are less susceptible to excessive temerarious beliefs and would more likely than the King raise taxes on the basis of evidence.

In short, it is insufficient to erect rules that assist the DM to fight off excessive temerity. What matters is credible rules. For the constitution to specify that only the parliament can raise taxes, whereas the parliament is based on representation, the power to tax is less easily swayed by excessive temerarious beliefs than would be the case if the power rested in the hands of a hard-to-remove king.

The assumptions

The proposed generalised principal-agent model employs the following reasonable assumptions:

-

1. The objective functions of the DM and the principal are made up of identical time-consistent preferences;

-

2. The DM and the principal make decisions at discrete time τ (τ = t 1, …, t n), running from the present (t1) to retirement (tn), where they start with the correct prior at t 1;

-

3. The DM and the principal differ regarding Bayesian updating of the likelihood of success starting at t2: while the principal employs Bayesian updating, the DM forms biased priors (Pb) in the direction of temerity;

-

4. The DM, not the principal, is the doer, and hence, the acts are based on Pb starting t2;

-

5. The DM is either unaware or, more likely, dismissive of the prognosis of the principal regarding success;

-

6. The DM and the principal have perfect and common information about their property rights, i.e., they concur regarding the costs and benefits of shirking or taking gambles;

-

7. The DM does not suffer from any loss of integrity, utility, moral disutility, blame, etc., for taking an action that may inflict pain on the principal–whereas any pain is simply the cost of the act;

-

8. The DM and the principal are risk-neutral;

-

9. Regarding the standard principal-agent model, if the DM is caught shirking, the principal would punish the DM, but the DM cannot retaliate.

-

10. The DM does not gain any skill or extra ability from learning or investing in technology on how to evade the principal’s punishment because the punishment is unmitigated function of whether the principal suffers from the DM’s gamble.

Decisions and Dynamics

The Principal’s Command

The principal commands that the DM undertakes a binary act Aτ to take a risky consumption, a confrontation, or a gamble (Aτg) or not (Aτng) to maximise expected benefit (Qτ),

Pτ is the probability of success based on facts available at time τ, i.e., the probability of avoidance of detection and punishment or, in the generalised model, the avoidance of self-harm. Bτ is the benefit of the gamble, whether the gain is a good, leisure, a bribe, an embezzlement, and so on. If the principal is caught, she would have to surrender Bτ or its equivalent. In addition, the principal would have to pay Cτ, the cost of punishment in terms of imprisonment, the loss of bonus, the loss of reputation, or, in the generalised model, bodily harm and discomfort.

We may complicate this simple decision by adding, in the standard case, that the agent may have some positive altruistic preference toward the principal. Also, in the standard case, the agent may invest in technology to avoid detection/punishment.

To keep the decision simple, the principal commands

For example, in the generalised model, if the expected discomfort from eating an extra serving of food is less than the expected benefit, the principal commands the extra serving. In contrast, in the standard model, the principal commands shirking if the DM’s expected additional leisure exceeds the expected cost, say, of losing bonus pay.

It might be hard to imagine how the principal could command the agent to shirk. But the principal could raise the monitoring technology to catch the agent shirking, say, for 10 minutes. The principal finds that the cost of such technology is greater, at the margin, than the benefit of stopping the 10-minute shirking. This in effect means that the principal finds it beneficial to tolerate some shirking.

The DM’s action

Irrespective of the principal’s command, the DM (agent) reaches the decision about whether to gamble given the biased prior (Pb), according to the temerity heuristic assumption. Let us assume that a gamble was taken in a period preceding the one under focus. In this case, Pb either surpasses or fails to surpass P (the objective probability held by the principal):

$$\eqalign{ & {{\rm{P}}^{\rm{b}}}_\tau {\rm{I}}{{\rm{A}}_{\tau - 1}}^{\rm{g}}\left\{ {\matrix{ { \gt {{\rm{P}}_\tau }{\rm{I}}{{\rm{B}}_{\tau - 1}} \gt {\rm{ }}0} \cr { = {{\rm{P}}_\tau }{\rm{I}}{{\rm{C}}_{\tau - 1}} \gt {\rm{ }}0} \cr } } \right. \cr & {\rm{for\,all }}\,\tau\,{\rm{ }}\left( {\tau = {{\rm{t}}_2}, \ldots, {{\rm{t}}_{\rm{n}}}} \right) \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{ & {{\rm{P}}^{\rm{b}}}_\tau {\rm{I}}{{\rm{A}}_{\tau - 1}}^{\rm{g}}\left\{ {\matrix{ { \gt {{\rm{P}}_\tau }{\rm{I}}{{\rm{B}}_{\tau - 1}} \gt {\rm{ }}0} \cr { = {{\rm{P}}_\tau }{\rm{I}}{{\rm{C}}_{\tau - 1}} \gt {\rm{ }}0} \cr } } \right. \cr & {\rm{for\,all }}\,\tau\,{\rm{ }}\left( {\tau = {{\rm{t}}_2}, \ldots, {{\rm{t}}_{\rm{n}}}} \right) \cr} $$

where ‘I’ is the operator ‘given’. That is, the DM updates the prior in an asymmetrical fashion. She updates it upward if the gamble succeeds in the previous period, but do not symmetrically update downward otherwise. That is, the heuristic engenders a (temerity) bias.

With this temerity heuristic assumption, the asymmetrical response would generate, on average, over time a belief that excessively exaggerates the likelihood of success.

Put differently, the temerarious DM updates upward above the principal’s probability (P) upon learning of the accidental success in the previous period. However, ceteris paribus, the DM does not update downward below the principal’s P upon learning of the accidental failure in the previous period. The DM would be a non-biased estimator, i.e., free of temerity, if her downward update fully offsets her upward update.

In this rendition, the DM reaches the principal’s P in the case of failure. But the assumption need not be this strong. It is enough to stipulate that the DM may update downward below the principal’s P, but not to an extent that fully offsets the upward swing in the case of success.

With enough rounds, the discrepancy between the DM’s Pb and the principal’s P will widen, where the DM’s Pb will become higher than the principal’s in an excessive manner. There can be two different mechanisms that engender the discrepancy.

First, it could be the case that a series of gambling acts that succeed each other decreases the probability of success in avoiding, in the case of eating, stomach discomfort or, in the case of shirking, getting detected and punished. While the principal properly updates the probability downward, the DM maintains the old probability. So, the DM fails to abstain from the gambling acts, considering the rising probability of getting caught or enduring self-harm.

The discussion above has already suggested the second mechanism. On the one hand, success leads the DM to exaggerate the updated likelihood of success above what is warranted by the facts. On the other hand, the DM does not sufficiently lower the likelihood of success in the face of failure. Here the DM is rather selective in the assessment of the facts to buttress excessively positive beliefs regarding the success of gambles.

Dynamics

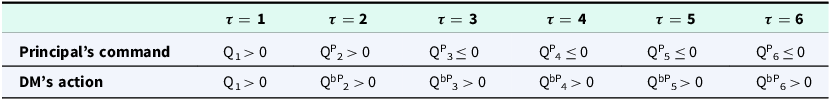

Let us examine a stylised dynamic to demonstrate the consequence of the discrepancy between the principal’s P and the DM’s Pb. Table 2 shows the decisions of whether to gamble in six time periods (τ = 1, …, 6). The first row specifies the time period; the second row lists the principal’s expected benefit based on P; and the third row registers the DM’s expected benefit based on Pb.

Table 2. How actions become reckless

When the expected benefit (Qτ) is strictly positive for either self, the optimal decision is to gamble. The superscript indicates the probability upon which the decision is based. In this stylised example, the assessment of Qτ is the same in the first period. While the assessment of Qτ may diverge in the second period, the decision is the same: to gamble. From the third period onwards, the discrepancy of the likelihood engenders different decisions. But the action expresses the DM’s decision, which is to gamble when the principal commands the contrary. In this stylised example, we assume that the DM is lucky and succeeds, which emboldens him or her further to exaggerate the likelihood of success and, correspondingly, to gamble.

If the dynamics is left alone, optimum temerity escalates to an excessive, dangerous level. Thus, the rational DM places rules—e.g., setting up a maximum level of consumption per period—to tame excessive temerity.

The thesis of the paper is accomplished. The root of rules amounts to the principal’s decision to annul intertemporal dynamics of biased probability formation. This biased probability formation provides the insight that the rule, under a specified condition, can be suspended without the specter of inviting intertemporal dynamics of biased probability formation. The condition is allowing overconsumption only within specified holiday periods. The holiday license condition effectively neutralizes the intertemporal dynamics of biased probability formation. The success of overconsumption during a holiday license does not entice the DM to upward update the probability of success. Once the DM places the self within the confines of an institution, i.e., a holiday, that explicitly allows overconsumption, any positive outcome does not lead the DM to wrongly upgrade the likelihood of success.

In contrast, if we trace the rule to primitive present-bias preferences—which is the basis of diverse received theories of temptations—we are unable to explain why rational DMs invent holiday licenses. We would be free from the Holiday License Paradox once the analysis starts with rules, and trace them to a temerity heuristic—what this paper maintains.

Conclusion

This paper advances a basic idea. If we want to understand temptations, we should not start with tempting, present-bias preferences. Rather, we should start with rules (core thesis I). To understand rules, we should start with temerity (core thesis II). Finally, to understand temerity, we should start with optimal heuristics needed in critical decisions (core thesis III).

According to core thesis III, DMs adopt efficient temerity-as-heuristics to ensure survival in critical life-and-death situations. But such heuristics can go amiss, causing the lowering of wellbeing or fitness. Therefore, DMs can do better by erecting rules to stave off the excesses of temerity, i.e., applying rules that annul excessive temerity-based decisions in situations that are not life-and-death.

Once we have rules adopted to correct for excessive temerity-based choices (core thesis II), we can understand tempting, present-bias preferences (core thesis I). Such preferences are suboptimal only in relation to the adopted rules.

Still, what is the payoff of rejecting the received literature that conceives temptations as prior to rules? One payoff is the solution of the Holiday Licence Paradox. Insofar as received theories conceive tempting preferences as the entry point, they basically must conceive any deviation from rules as suboptimal. DMs have to basically lead a puritan lifestyle. Such a lifestyle has no room for holiday licences at the entry point of analysis.

In contrast, if we conceive temerity-as-heuristics as the entry point – where rules function as corrective technologies of excessive temerity-as-heuristics – we can easily explain holiday licences. DMs can see how such licences improve wellbeing, i.e., how the violations of rules can be beneficial as long as the violations are confined to holidays; they do not pose any threat to the rules once the holiday is over. After all, the ‘enemy’ is not the violation of the rules but rather intertemporal dynamics of biased probability formation.

For future research, experiments can be conducted to test the proposed hypothesis. Namely, rules are a function of temerity. It is difficult to measure the variation of rules, i.e., puritan lifestyle, across participants in the experiment. We can instead measure the variation of reckless choices (succumbing to temptations) across participants. The experiment design consists of three stages. In the first stage, the participants are tested regarding their propensity to be temerarious. The experimenter can use one of the tests developed by psychologists, e.g., Kruger and Dunning (Reference Kruger and Dunning1999). The second stage of the experiment is to screen out participants who are risk-loving. (Those participants can be paid to do other unrelated tasks to the end of the experiment). In the third stage, the experimenter offers different investment strategies with different returns and risks. While the returns on the risky options are higher than on less risky options, it should be obvious that the difference should not justify the investment in the risky options. Experimenters are given a chance to learn how to calculate ‘expected value’. They are tested to make sure they realise that the expected value of the risky options is lower than the less risky options. That is, the less risky options dominate the risky ones for the participants (who are risk averse or risk neutral). The hypothesis is that the participants with high degrees of temerity will invest more frequently in the risky options than those with low degrees of risk. Thus, participants with high degrees of temerity will end up with lower financial portfolios than their counterparts.

There can be many variations of this experiment design, including measuring whether temerity is correlated with risk-loving. The first task, however, is to Question the standard entry point that posits rules as a function of temptations. The task is to start conceiving temptations as a function of rules.

Data Availability Statement

This paper does not include any data.

Acknowledgements

Earlier drafts benefited from the comments of Jonathan Baron, Harold Demsetz, Eric Schliesser, Leonidas Montes, James Buchanan, Yew-Kwang Ng, Ian McDonald, Haiou Zhou, and especially the comments of Tim Rakow and Steven Gardner. The paper benefited from the support of the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research (Altenberg, Austria) and from the Faculty of Business and Economics at Monash University. The most recent draft benefited from the comments of five anonymous reviewers. Michael Dunstan has provided valuable research assistance, and Maks Sipowicz provided useful editorial help. The usual caveat applies.

Conflict(s) of Interest

This paper is free from conflict of interest of any kind.

Funding statement

The research behind this paper has not received any funding. Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library