1. Introduction

The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (CGEL; Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), gives a categorially explicit account of English numeratives: cardinals are both determinatives and nouns, ordinals are adjectives, and fractionals are nouns – not phrases but words. What this lexicalist approach doesn’t give is a worked-out syntax for larger numeratives; even very large expressions are treated as single lexemes with sui generis internal structure. Subsequent work has prioritized cardinals and cross-linguistic comparison, leaving English ordinals and fractionals underanalyzed. The most detailed recent English constituency study is He & Her (Reference He and Her2022), who show that complex additive numeratives behave as syntactic constituents.

The main cross-linguistic alternative is the cascade analysis of Ionin & Matushansky (Reference Ionin and Matushansky2006, Reference Ionin and Matushansky2018), which treats numerals as recursive functional projections. While compelling for languages with rich morphological marking, section 3.1.2 demonstrates that this architecture can’t account for English morphological, prosodic and syntactic patterns.

In this article, I develop a hybrid analysis that keeps CGEL’s categorial commitments but replaces its limitless lexicalization with syntax where English shows syntactic structure. The article is structured as follows. After establishing conventions and terminology, section 3 tackles the central lexicon–syntax debate. It begins by reviewing existing phrase-constructional approaches, demonstrating in section 3.1.2 why the influential cascading NumP architecture of Ionin & Matushansky fails for English. After considering lexicalist accounts in section 3.2, the section culminates in section 3.3 with the proposal of a new hybrid framework, arguing that numeratives below 100 are lexemes while larger expressions are syntactic constructions.

Having established this core architecture, section 4 addresses the internal syntax of these constructions, arguing that factors (e.g. two in two hundred) function as modifiers, not determiners or complements. Section 5 then provides a detailed categorial analysis of the system’s components, refining CGEL’s account by distinguishing proper from common cardinal nouns based on clear distributional diagnostics. The final section summarizes the empirical gains: alignment of morphology, prosody and ellipsis; reduction of the determinative lexicon; and an explanation of why English is lexical below 100 but requires overt syntax above it.

1.1. What I don’t claim

I don’t claim that the English solution extends unchanged to languages where Ionin & Matushansky’s cascade is independently motivated by case, classifiers or adpositional morphology; that there is no post-syntactic morphology in English numeratives – only that it can’t replace the missing constituent required by ordinal/fractional morphology; that decimals, algebraic variables and constants belong to the same syntactic space as English numeratives (they are excluded by stipulation); or that arithmetic transparency determines constituency. The claims are confined to Present-Day Standard English numeratives and the morphosyntactic evidence they present.

2. Terminology and conventions

A number is a mathematical object (e.g.

![]() $ 7 $

,

$ 7 $

,

![]() $ \pi $

). A numeral is a linguistic expression (word, conventional compound or symbol string) that denotes a number; expressions with overt arithmetic operators (e.g. ten plus three,

$ \pi $

). A numeral is a linguistic expression (word, conventional compound or symbol string) that denotes a number; expressions with overt arithmetic operators (e.g. ten plus three,

![]() $ {7}^3 $

) are excluded. A numerative is a conventionalized number-denoting syntactic constituent without overt arithmetic operators. I exclude by stipulation idiosyncratic common nouns representing specific quantities like couple, dozen, score, gross, myriad, etc.

$ {7}^3 $

) are excluded. A numerative is a conventionalized number-denoting syntactic constituent without overt arithmetic operators. I exclude by stipulation idiosyncratic common nouns representing specific quantities like couple, dozen, score, gross, myriad, etc.

I introduce magnitude to denote the subcategory of lexemes whose value is

![]() $ {10}^x $

where

$ {10}^x $

where

![]() $ x $

is an integer greater than 1, and I call the non-magnitude numerative lexemes basic numeratives.

$ x $

is an integer greater than 1, and I call the non-magnitude numerative lexemes basic numeratives.

Following CGEL, a determinative is a lexical category including the, many, each, etc. A phrase, such as a determinative phrase (DP), is a headed constituent. A coordination is a non-headed constituent made up of coordinates – not a phrase. Throughout, DP names a phrase headed by a determinative; it does not imply that NPs are projections of D.

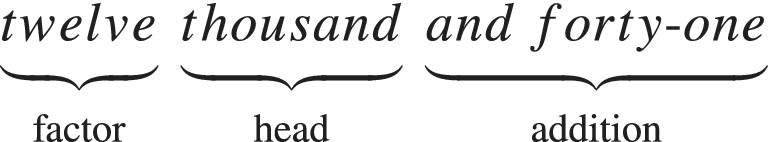

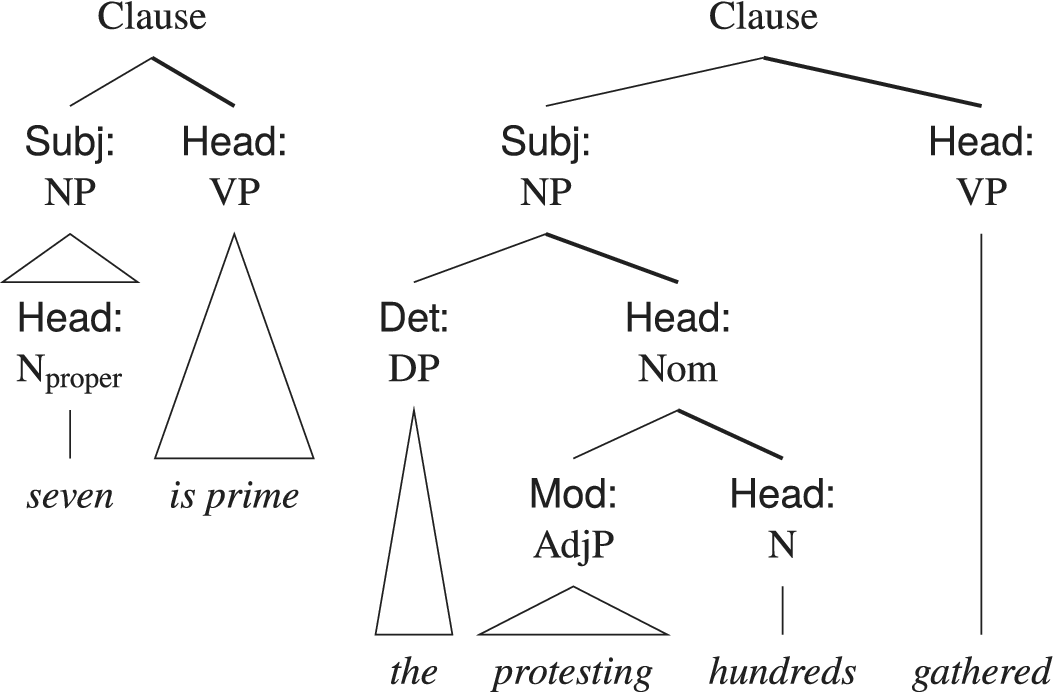

I also define a number of terms for syntactic functions (see figure 1). A determiner is an NP-internal dependent ( no more than one book). A factor is a pre-head modifier licensed by a magnitude (e.g. two thousand). An addition is a coordinate in a numerative coordination following a coordinate with a magnitude head.

Figure 1. The special syntactic functions in numeratives

3. Constructions versus lexemes

The question addressed in this section is how to view the internal structure of complex numeratives like two thousand twenty-seven. Two contrasting approaches have emerged in the literature. The first treats these numeratives primarily as phrasal constructions with internal syntactic structure, while the second approaches them as lexical items. I examine each approach, beginning with the phrasal-construction perspective.

3.1. Phrase-constructional approaches

Brainerd (Reference Brainerd1966) offered one of the first rigorous attempts to capture English ‘verbal numerals’ with formal grammar rules. He argued that certain ‘copying’ mechanisms were needed to generate complex items (e.g. two thousand twenty-seven), underscoring that these can’t be handled by standard phrase-structure rules alone. While this demonstrated the combinatorial complexity of numeratives, Brainerd’s system was mainly concerned with string generation. It set aside deeper syntactic questions (e.g. headedness or constituency tests), leaving open how to integrate numeratives into broader clause structures.

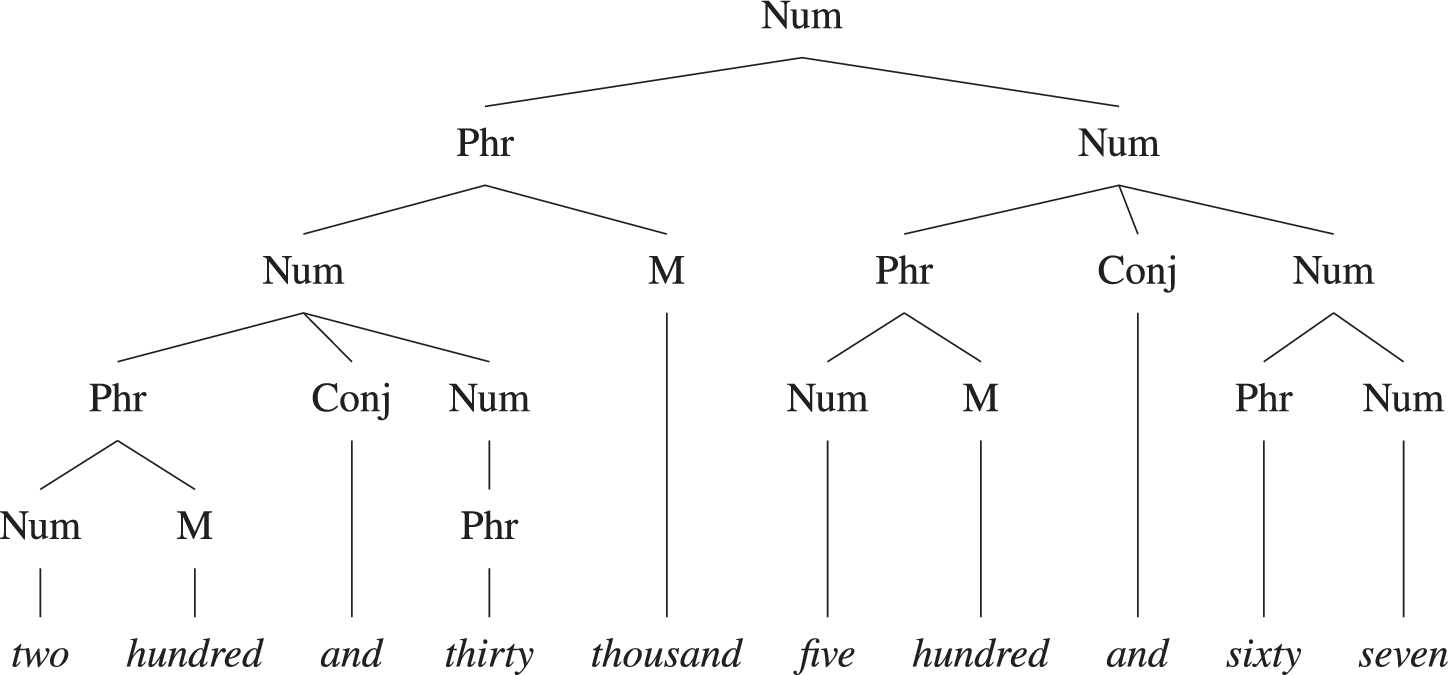

Hurford (Reference Hurford1975, Reference Hurford1987) examined the conceptual underpinnings of numerals and numeratives across languages. In his view, an abstract universal representation of additive and multiplicative operations precedes any language-particular spelling-out. Though this illuminates the cross-linguistic consistency of decimal systems, it downplays the syntax of individual languages. His later work (Hurford Reference Hurford and Plank2003) sketches phrase-structure rules aligning numeratives with typical syntactic constituents, but again, there is little emphasis on distributional constraints unique to English (e.g. how factors and and-marked additions behave in certain contexts). Hurford (Reference Hurford and Plank2003) explains how this conceptual structure is realized in English syntax through a concrete phrase structure grammar, as exemplified in figure 2. It provides the lexical and phrasal categories of each constituent but lacks an analysis of their syntactic functions and headedness.

Figure 2. Phrase structure of the numerative for 230,567, reproduced from Hurford (Reference Hurford and Plank2003: 42)

3.1.1. Categorial and functional analysis within HPSG

While Hurford’s publications provided a semantic framework for understanding numeral systems, he didn’t fully explicate the syntactic functions of numerative constituents within phrase structure. This gap was addressed by Smith (Reference Smith, Webelhuth, Koenig and Kathol1999: 145), who offered a detailed treatment of English numeratives as phrases within Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG). Smith’s analysis demonstrated that ‘English number names such as two hundred twelve thousand twenty-two can be represented quite naturally in HPSG as phrases rather than lexical items.’ HPSG also provided the desired categorial and functional analyses, absent from earlier accounts.

Smith’s analysis makes several important theoretical contributions. First, he demonstrates that English number names can be represented as phrases within HPSG through a systematic mapping between semantic operations and syntactic structures. Specifically, multiplicative relationships (as in two hundred) are realized through specifier–head constructions, while additive relationships (as in two hundred five) are realized through head–complement relations.

The system has several desirable properties: (i) all constraints on specifiers and complements are expressed in terms of upper bounds on the corresponding integers; (ii) each head takes at most one complement and one specifier; (iii) all complements are optional while specifiers are obligatory; (iv) the semantic composition is straightforward, with heads treating their specifiers’ and complements’ semantics as unanalyzed wholes.

Smith’s account of English numeratives seeks to explain not only why hundred must be the head in two hundred – the head’s distribution determines that of the phrase – but also why two hundred five must be headed by hundred rather than two or five. The analysis requires no special machinery beyond new subsorts and features already motivated in HPSG. In section 5.1, I explain why hundred is the head in cases like two hundred, but not in cases like two hundred and twelve.

3.1.2. Ionin & Matushansky’s cascading NumP: theory and English evidence

A recent cross-linguistic analysis of numerals is Ionin & Matushansky’s (Reference Ionin and Matushansky2006, Reference Ionin and Matushansky2018) cascading NumP architecture. Their theory, developed primarily from languages with rich case and agreement morphology – and explicitly limited to cardinals – makes two pertinent core claims about syntactic structure. First, each numeral projects its own functional layer (NumP), with higher numerals merging as specifiers of lower Numeral heads. For two hundred books, this yields the structure [two [hundred [books]]], where two is in Spec-NumP of the Num head hundred. This architecture provides no constituent containing two hundred without also including books.

Second, additive numerals arise from coordination of full NumP+NP structures with the NP deleted in non-initial conjuncts at PF. And so twenty-two books derives from ‘twenty books and two books’, with deletion of the first books. This extends to all additions: two hundred (and) five books would derive from ‘two hundred books and five books’.

While this architecture elegantly captures case and agreement patterns in languages like Russian for cardinals, independent diagnostics reveal that English ordinals and fractionals require exactly the constituent structure their theory denies. First, English ordinal and fractional morphology systematically targets the rightmost simple base of the numerative, requiring a constituent boundary before the noun.

Under Ionin & Matushansky’s NP-deletion analysis, (1a) would derive from the twentieth step and the second step, yielding both incorrect form (*twentieth-second) and meaning (two distinct steps). The morphology requires a constituent containing twenty-two but not step, but their cascade provides only [twenty [two [steps]]] with no intermediate boundary between the numerative and the noun. The constituent [twenty-two] targeted by ordinal morphology simply doesn’t exist in their structure. Any post-syntactic repair that forces the suffix onto the rightmost base must recreate this missing constituent, undermining the core architectural claim. Similar issues affect fractionals like (1b).

Second, intonational phrasing in complex numeratives places a strong break after each magnitude phrase, as in (2a) and (2b), but never inside a basic (21–99) compound (2b).

These breaks coincide with the domain targeted by ordinal and fractional morphology. Ionin & Matushansky’s cascade predicts boundaries after every individual numeral including not only (2a) but also, incorrectly, (2b).

Third, English freely coordinates and substitutes numeratives as constituents. The examples in (3) show that complex numeratives are constituents.

All three diagnostics – morphology, prosody and ellipsis and coordination – converge on the same constituent boundaries: after each magnitude unit [two thousand] [and twenty-two] and at the numerative–noun boundary [two thousand and seven] books. This convergence can’t be accidental. The constituent that English morphology requires is the same one that prosody demarcates and that ellipsis/coordination isolates. While Ionin & Matushansky’s cascade may be correct for languages where case morphology tracks NumP boundaries, English shows overt evidence for precisely the intermediate constituent their architecture forbids. As shown in the next section, this motivates adopting the constituency-based analyses of He & Her (Reference He and Her2022).

3.1.3. He & Her’s English constituency evidence

He & Her (Reference He and Her2022) provide comprehensive English-internal evidence that complex additive numeratives are syntactic constituents. Their analysis deploys three key diagnostics, each revealing the constituent status of numeratives through distinct syntactic phenomena.

First, substitution and fused-head constructions demonstrate constituency through systematic replaceability. In She bought twenty books, but I bought twenty-two , the numerative twenty-two functions as a complete constituent – specifically a determinative phrase (DP) in fused-determiner–head function. This pattern extends to factor substitution: How many thousand? Two, where the factor alone can stand as a complete answer. These substitution possibilities would be impossible if numeratives lacked constituent status.

Second, compounding behaviour reveals that entire numeratives modify as units. In compounds like a twenty-two-foot sailboat, the complex numerative twenty-two must exist as a constituent before entering the compound construction. The singular form foot (not feet) shows that the noun enters this construction as a bare stem, and crucially, the numerative must similarly enter as a complete unit. If twenty-two weren’t a constituent – if it were assembled only after combining with the noun – we couldn’t explain why the entire expression twenty-two-foot behaves as a single modifier. This compounding diagnostic is particularly revealing because it requires numeratives to have independent syntactic status before any morphological operations apply.

Third, coordination patterns show that expressions like two hundred and twenty behave as coordinations of constituents: [two hundred] and [twenty]. The ability to coordinate these units (two hundred or three hundred people) and to target subparts with ellipsis confirms their constituent status. Crucially, this coordination structure aligns with the boundaries required by ordinal and fractional morphology discussed in section 3.1.2.

While I adopt He & Her’s diagnostics as compelling evidence for constituency, I diverge from their analysis regarding the lexeme/phrase boundary for reasons explained in section 3.3.

3.2. Lexical approaches to complex numeratives

Having examined the major phrasal approaches to numerative constructions, I turn to the lexical view that treats complex numeratives as compound words rather than as phrases or coordinations.

The lexical approach is exemplified by Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 393) and, more explicitly, by Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 385). While Quirk et al. treat complex numeratives as lexemes primarily by implication, Huddleston & Pullum et al. make their position clear, arguing that ‘the rules which govern the internal structure of the syntactically complex numerals are sui generis, and, with one minor exception, this internal structure is unaffected by the wider syntactic context. We will therefore treat all numerals as belonging to the lexical category determinative, on a par with other unmodified determinatives.’

According to this view, the internal structure of numeratives like two thousand (and) seven is both ‘syntactically complex’ and morphological, as discussed in chapter 19 of CGEL on lexical word-formation. In this analysis, thousand serves as the head, with two functioning as a factor (CGEL’s multiplier) and (and) seven as an addition, mirroring Smith’s (Reference Smith, Webelhuth, Koenig and Kathol1999) syntactic-headedness analysis.

But this treatment of numeratives as lexemes raises some questions when considered in the broader context of CGEL’s approach to complex lexical items. Elsewhere in CGEL, the only syntactically composite lexical items recognized are dephrasal compounds, defined as ‘a sequence of free bases [that …] arise […] through the fusion of words within a syntactic structure into a single lexical base’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1646). Examples include phrases like a holier-than-thou attitude.

This narrow definition prompts a reconsideration of whether all numeratives are indeed lexemes. If so, it would represent a significant expansion of the set of composite lexical items beyond dephrasal compounds. This expansion would require justification and potentially a reevaluation of the criteria for lexeme status.

The contrast between phrase-structural approaches and CGEL’s lexical analysis underscores a core theoretical tension in modelling numeratives. Phrase-structural frameworks, such as those advanced by Hurford (Reference Hurford and Plank2003) and He & Her (Reference He and Her2022), excel in capturing the syntactic independence of each constituent in complex numeratives, explaining the prosodic autonomy of magnitude units (e.g. intonation breaks in two thousand [pause] and thirty) and modelling the compositional semantics of numerical expressions through hierarchical rules. He & Her’s constituency tests (substitution, compounding, coordination) demonstrate that complex numeratives behave as syntactic units rather than atomic lexemes. But these frameworks remain incomplete: they lack a fully worked out syntactic description of complex numeratives, along with explicit mechanisms to resolve morphosyntactic conflicts, such as ordinal suffix placement (twenty-second vs *twentieth-two).

Conversely, CGEL’s lexicalist approach – treating numeratives as determinatives with sui generis internal structure – sidesteps these challenges by relegating morphological idiosyncrasies (e.g. ordinalization rules) to the lexicon. But this lexical flexibility comes at a cost: it obscures the phrasal behaviour of complex numeratives, such as their capacity for internal coordination (two hundred [and] thirty) and prosodic independence, which align with syntactic rather than lexical patterns.

3.3. A hybrid approach: synthesis and resolution

The preceding review of phrasal and lexical approaches reveals strengths and limitations in each. This subsection advances a hybrid model that synthesizes insights from both, resolving the central tension by drawing a principled line between the lexicon and the syntax. The core claim is that numeratives 0–99 are lexemes, whether morphologically simple, derived with -teen/-ty, or compound (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1716), while larger expressions are syntactic constructions – either phrases or coordinations. This division allows the model to account for the clear syntactic, prosodic and morphological patterns that purely lexical or purely phrasal accounts struggle with.

A significant theoretical advantage of result is the parsimony of the lexicon. Under a fully lexicalist treatment like CGEL’s, the category of determinatives becomes an infinite, open one containing every possible numerative. By contrast, the hybrid analysis restricts determinatives to the basic numeratives (0–99) and the magnitude words (hundred, thousand, etc.). This creates a finite, closed category of fewer than 200 items. This aligns determinatives with other closed categories like prepositions or pronouns, which are typologically expected to have small memberships, rather than making them an anomalous exception.

3.3.1. Syntax above ninety-nine

The syntactic nature of complex numeratives should be the default assumption based on their apparent multi-word nature. Two thousand simply looks like a phrase, and one hundred and twenty like a coordination. This assumption is supported by prosodic and syntactic properties.

In speech, for instance, a numerative like two thousand twenty-two is typically parsed with an intonational break separating the magnitude units (two thousand // twenty-two). This prosodic phrasing is characteristic of syntactic constituents in a coordination, contrasting sharply with the fused prosody of lexical compounds (e.g. a bread-and-butter issue).

Ellipsis patterns provide further support for this internal syntactic structure. Consider the example from Ionin & Matushansky (Reference Ionin and Matushansky2006: 338):

While interpretation (4a) is by far the more natural, Ionin & Matushansky report that ‘the majority of the speakers we have asked also accept (4b)’ (2006: 338, fn 22). This suggests that hundred books forms a constituent permitting substitution of two with three under ellipsis – a possibility excluded if complex numeratives were lexically atomic, as CGEL claims. Instead, it corroborates the hierarchical internal structure proposed here, where the factor (two) and magnitude (hundred) retain syntactic independence within a larger constituent.

Another significant syntactic piece of evidence is that modifiers can be interpolated (5).

This should not be possible in lexemes.

3.3.2. Lexemes below one hundred

The status of the simple and derived numeratives words is undisputed; that of the putative compounds with dashes (e.g. twenty-one) isn’t so clear. Five converging diagnostics show that they are indeed compound lexemes, locating the morphology–syntax boundary just beyond 99.

First, only the 1–99 lexemes can appear as factors ( twenty-one thousand) and as additions (two thousand and twenty-one ). Those above 99 don’t occur in either function. This pattern picks out a natural category of the basic numeratives that includes the putative compounds.

Second, though how many freely replaces constituents in larger numeratives (3), it can’t target subparts of twenty-one: *how many one, *twenty how many. This impossibility indicates that twenty-one is already atomic at syntax.

Third, unlike in high-value examples like (5), insertions inside the dashed words are rejected: *twenty whole / precisely / roughly two. Morphology blocks internal modification.Footnote 1

Fourth, phrasal numeratives allow overt coordination (two thousand and seven books); 21–99 compounds resist it (?twenty and one books).Footnote 2

An objection – echoing Comrie (Reference Comrie, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) – holds that because additive forms match the arithmetic template

![]() $ \left(n\times b\right)+m $

with

$ \left(n\times b\right)+m $

with

![]() $ m<b $

, they must be syntactic phrases. This conflates mathematical transparency with syntactic constituency. Comrie explicitly abstracts away from element order, the very evidence syntactic tests exploit. Transparent arithmetic composition therefore does not force phrasality. English contains many morphologically complex yet syntactically atomic words – thirteen (‘10 + 3’), unhappiness (‘not happy + ness’). The contrast between licit twenty plus twelve (

$ m<b $

, they must be syntactic phrases. This conflates mathematical transparency with syntactic constituency. Comrie explicitly abstracts away from element order, the very evidence syntactic tests exploit. Transparent arithmetic composition therefore does not force phrasality. English contains many morphologically complex yet syntactically atomic words – thirteen (‘10 + 3’), unhappiness (‘not happy + ness’). The contrast between licit twenty plus twelve (

![]() $ =32 $

) and unattested *twenty-twelve confirms the point: decade stems such as twenty- subcategorize for single-digit complements, just as -able selects verbs. The restriction is morpholexical, not mathematical; arithmetic facts of the Comrie variety remain true but are orthogonal to constituency.

$ =32 $

) and unattested *twenty-twelve confirms the point: decade stems such as twenty- subcategorize for single-digit complements, just as -able selects verbs. The restriction is morpholexical, not mathematical; arithmetic facts of the Comrie variety remain true but are orthogonal to constituency.

Fifth and finally, the compounds resist internal intonation breaks (*twenty // one). Higher numeratives break at each magnitude phrase (one hundred // twenty-seven million). Prosodic cohesion is a classic marker of lexical integrity.

These five independent diagnostics converge on 0–99 being a distinct and cohesive set. While no single test is conclusive, their systematic alignment demonstrates a grammatically motivated cut-off rather than arbitrary division. This analysis complements the evidence presented above and in section 3.1.2, where ordinal and fractional morphology, prosodic phrasing and ellipsis patterns all converge to reveal the same constituent boundaries – boundaries that are precisely what Ionin & Matushansky’s NP-deletion architecture denies. Together, these multiple lines of evidence directly support the hybrid model’s treatment of post-99 numeratives as genuine syntactic constructions.

4. The status of factors in numeratives

The evidence shows that English numeratives above 99 are phrases or coordinations. If that’s the case, what’s their structure? Smith’s headedness analysis is sound, but the function of the pre-head dependent is a puzzle.

To solve it systematically, I examine factors against CGEL’s three-way classification of dependents. According to Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 24), dependents fall into three major types: complements, determiners and modifiers. Each category has distinct syntactic properties that allow us to test where factors belong.

4.1. Are factors a subtype of complement?

The complement analysis is motivated by the fact that factors are licensed by the head magnitude word, and only by magnitude words. Also, complements are obligatory in many though not all contexts, a property shared by factors. The non-obligatory contexts are cases like the following:

In (6a) nouns thousand/dozen head a nominal in an attributive-modifier function. Those in (b) are non-count quantificational nouns selecting a plural oblique (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 351). And (c) involves adjectives functioning as attributive modifiers.

One might object that complements can precede their heads, as factors do. Pre-head complements such as the NP object in the PP [ the possibility of a veto notwithstanding] exist but are rare, being licensed chiefly by a small number of prepositions. This positional similarity, though, isn’t enough to establish factors as complements. More problematically, if factors were complements, they’d have to be licensed by determinatives (for cardinals), nouns (fractionals) and adjectives (ordinals). This is an extravagant outcome and a significant argument against this position.

Another problem is that factors are semantically multiplicative, which is sui generis among complements. One might propose that the by phrase in multiply three by seven shares similar semantics, but this stretches the comparison – the multiplicative meaning resides primarily in the verb multiply, not in the complement itself.

In sum, factors are only superficially like complements.

4.2. Are factors a subtype of determiner?

Since factors have quantificational (if multiplicative) semantics and quantification is a key semantic function of determiners, it’s natural to consider whether factors are determiners. Determiners are generally obligatory in singular countable NPs, though exceptions exist, such as certain complements in PPs (e.g. at school), bare-role NPs (e.g. they made her chair) and certain set meal nouns (e.g. I made lunch).Footnote 3 Similarly, factors are typically obligatory: for example, Bring one hundred pens is grammatical, whereas *Bring hundred pens isn’t.

Nevertheless, Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 385) reject the determiner analysis, considering the factor to be ‘an integral part of the numerative, and not as an independent determiner’. This aligns with a view of numeratives as lexemes, a stance that is less troubling if one adopts a non-lexical position. Still, their rejection warrants consideration.

In contrast, the determiner analysis finds support in the HPSG literature, which characterizes ‘constructions with multiplicative semantics [as] specifier–head constructions’ (Smith Reference Smith, Webelhuth, Koenig and Kathol1999: 148). Still, the specifier in HPSG encompasses a broader range of functions than the determiner in the CGEL framework.

One strike against a determiner analysis arises in examples like these two hundred pencils. In Huddleston & Pullum et al.’s (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002) analysis of this NP, these is a DP in determiner function and two hundred is a modifier. This creates a problem: attributive modifiers in NPs typically lack internal determiners (e.g. the faculty office, not *the [some faculty] office). A non-numerative determiner-like element is possible (e.g. the many-worlds interpretation), but this occurs only in morphological compounding, not as a syntactic phrase; factors appear in such constructions nonetheless.

Another significant problem with analyzing factors as determiners is that determiners are strictly NP-bound in CGEL (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 24). Since numeratives include ordinal adjectives with factors (e.g. two thousandth), treating factors as determiners would require substantial revisions to the framework.

Even for cardinal nouns, treating factors as determiners necessitates new machinery to account for the lack of number agreement: *the year two thousands and five. This isn’t a problem for cardinal determinatives, since determinatives don’t usually inflect for number, but – like AdjPs – neither do they license determiners; only NPs do.

The analysis is even more challenged by fractionals, which require a determiner to form an NP, even when a factor is present. For instance, There’s *(seven) three-hundredths of a gram requires a determiner such as seven, despite the presence of the factor three. And the number of the final word agrees with the determiner: one two-hundredth, two two-hundredths.

The same holds for cardinals with a factor: one two hundred, two two hundreds. If the factor were a determiner, the NP would contain two determiners, something explicitly rejected by CGEL.

All together, fractionals’ dependence on non-factor determiners, along with the appearance of factors in non-NP numeratives and their incompatibility with CGEL’s determiner constraints rule out a determiner analysis.

4.3. Are factors modifiers?

Having excluded factors as complements or determiners, I turn to the remaining category of dependents in CGEL: modifiers.

Factors like two in two hundred occupy the pre-head position typical of modifiers, scaling the magnitude word in a manner akin to predeterminer modifiers like twice in twice the size. Their multiplicative semantics aligns more with modification than with complementation, and their occasional optionality, as in the (one) thousand people, echoes modifiers’ flexibility. But their near-obligatory presence in most numeratives admittedly tempers this fit, marking them as an imperfect but plausible candidate within CGEL’s framework.

In the end, having dismissed the impossible, modifiers stand as the least improbable option within CGEL’s framework. These are modifiers that are possible in DPs, NPs and AdjPs, making them distinct from multipliers like twice in twice the amount.

This dependent-based analysis contrasts with Ionin & Matushansky (Reference Ionin and Matushansky2018), who treat factors as heads selecting magnitude complements. Yet treating two as a dependent (specifically, a modifier) of hundred better aligns with both English constituent order and cross-framework convergence, as the following HPSG mapping demonstrates.

5. Categorial analysis

Previous analyses of numeratives have frequently blurred distinctions between lexical categories and syntactic functions. Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 49), for instance, acknowledge that the form–function distinction is crucial, clearly differentiating syntactic categories (such as NP) from grammatical functions (such as subject or object). But they themselves conflate these concepts when analyzing numeratives, stating that ‘both cardinal and ordinal numeratives can function like pronouns … or postdeterminers’ (1985: 394): Pronoun isn’t a function and numeratives aren’t among the subcategories of pronouns in their analysis (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985: 345).

In contrast, CGEL offers a more principled categorial analysis, consistently distinguishing lexical category from syntactic function. It treats numeratives as clearly defined lexical subcategories: cardinal numeratives are determinatives and nouns, fractionals are nouns, and ordinals are adjectives. I propose a further refinement within the category of cardinal nouns, distinguishing proper nouns (when denoting abstract mathematical entities or serving as labels) from common nouns (when quantifying). This additional distinction resolves lingering ambiguities and clarifies cardinal nouns’ dual behaviour.

5.1. Determinatives (cardinal)

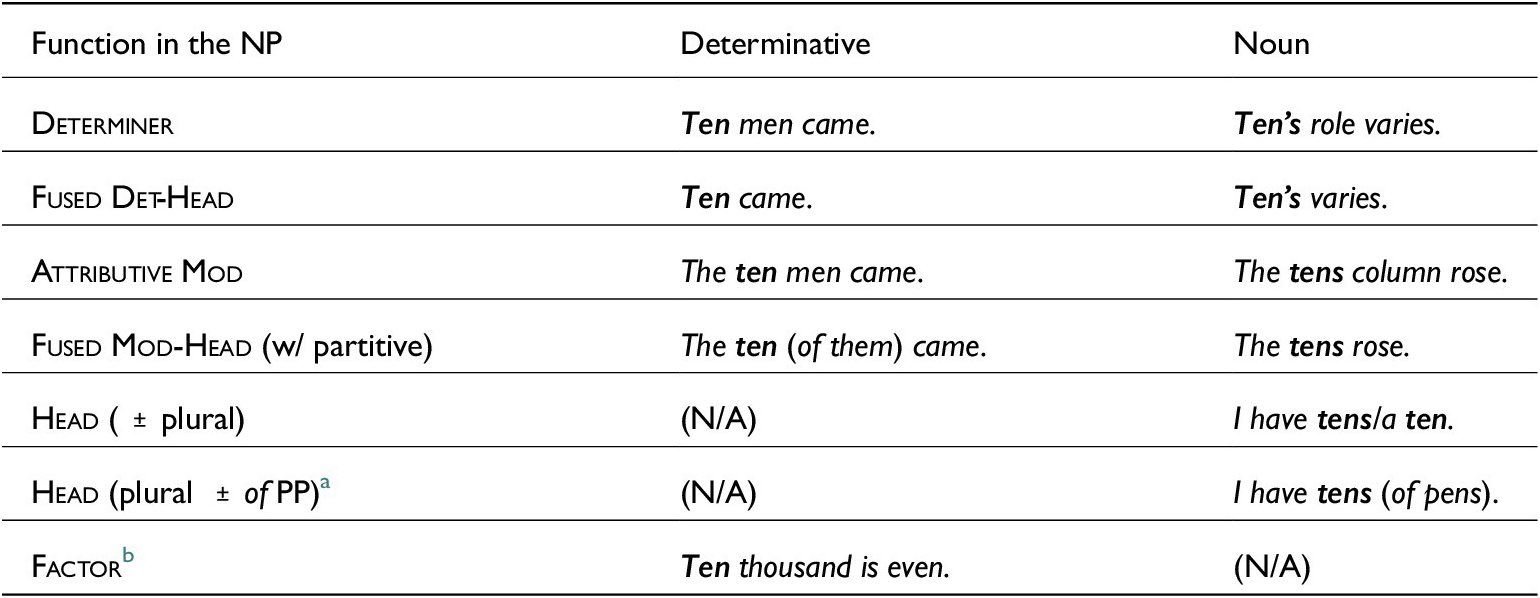

Cardinal determinatives display the following properties. Semantically, they denote counts, quantities, multiples and measures.Footnote 4 Syntactically, they head DPs that primarily function as determiners. (Their full range of syntactic functions is detailed in table 1, which contrasts the functions of determinatives and the DPs they head with those of nouns.) They license the same dependents as other determinatives (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 431), with the addition of factors, distinguishing them clearly from cardinal nouns. They allow modification by preposition phrases (PPs; e.g. at least twenty people), other determinative phrases (DPs; e.g. six hundred) and adverb phrases (AdvPs; e.g. not / almost / exactly / fully twenty people), a property less typical of cardinal nouns in isolation.Footnote 5 Like many other determinatives, the only complements they license are partitives like two of them. And, like most determinatives, cardinals don’t inflect for number or other grammatical categories.Footnote 6

Table 1. Syntactic functions of cardinal numeratives in NPs

a I have [single-digit]s of pens is possible (e.g. twos or fives), but this structure is mostly limited to magnitude words. Unlike fused Mod-Head NPs, this NP may also be non-partitive, which is to say that the complement in the PP may be indefinite.

b Only basic numeratives may be factors.

Table 1 contrasts the syntactic functions of cardinal determinatives and nouns. The key distinction is that only determinatives (heading DPs) can function as factors in complex numeratives,Footnote 7 while only nouns can head NPs with plural marking and of-complements.

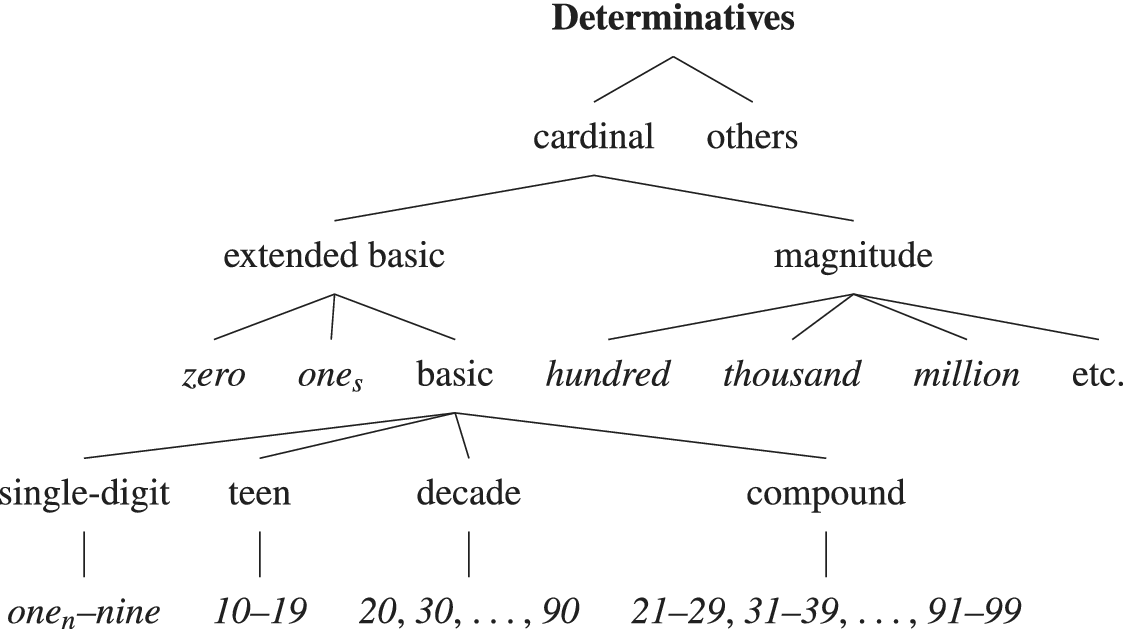

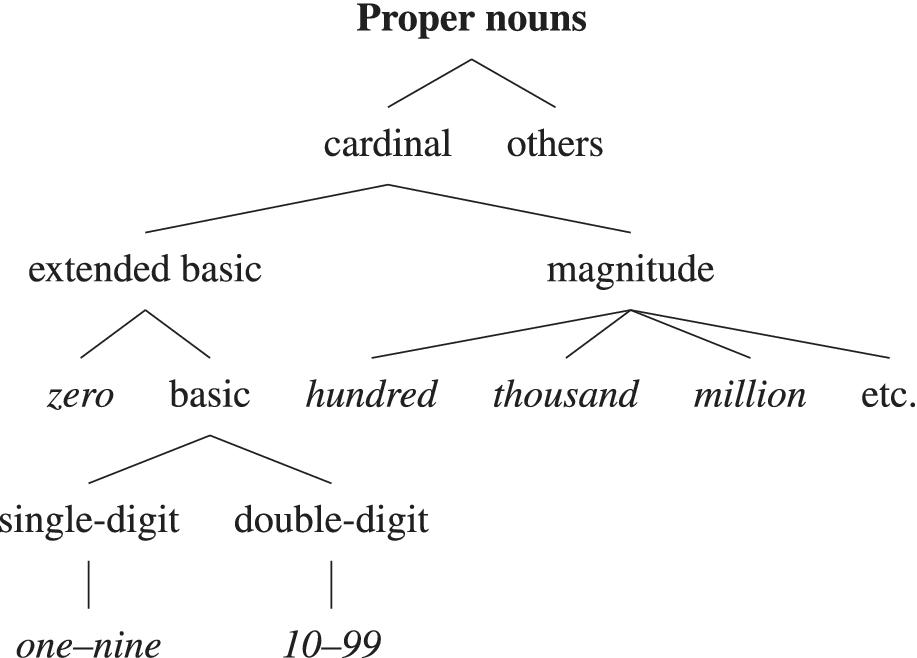

The structure of the lexical category of determinatives is presented in figure 3. Zero is treated separately due to its unique properties. Onen is numerical one, while ones is singulative one (e.g. They set out one fine day. She’s one solid performer; Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 386). Both can head DPs in determiner function, but only onen can head factors in numerative phrases.

Figure 3. The structure of the lexical category of determinatives

At the syntax–semantics interface, there is an additional, though less distinct, low–high numerative division (not shown) relevant to a count-noun diagnostic. Numeratives from zero up to roughly ten function as the low group (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 345). The boundary, however, is neither sharp nor binary. High numeratives ending with low numerative additions (e.g. one thousand twenty-seven) may be less acceptable with count nouns than those without such additions (e.g. *one police, ?twelve police, a thousand police, ?one thousand twenty-seven police.)

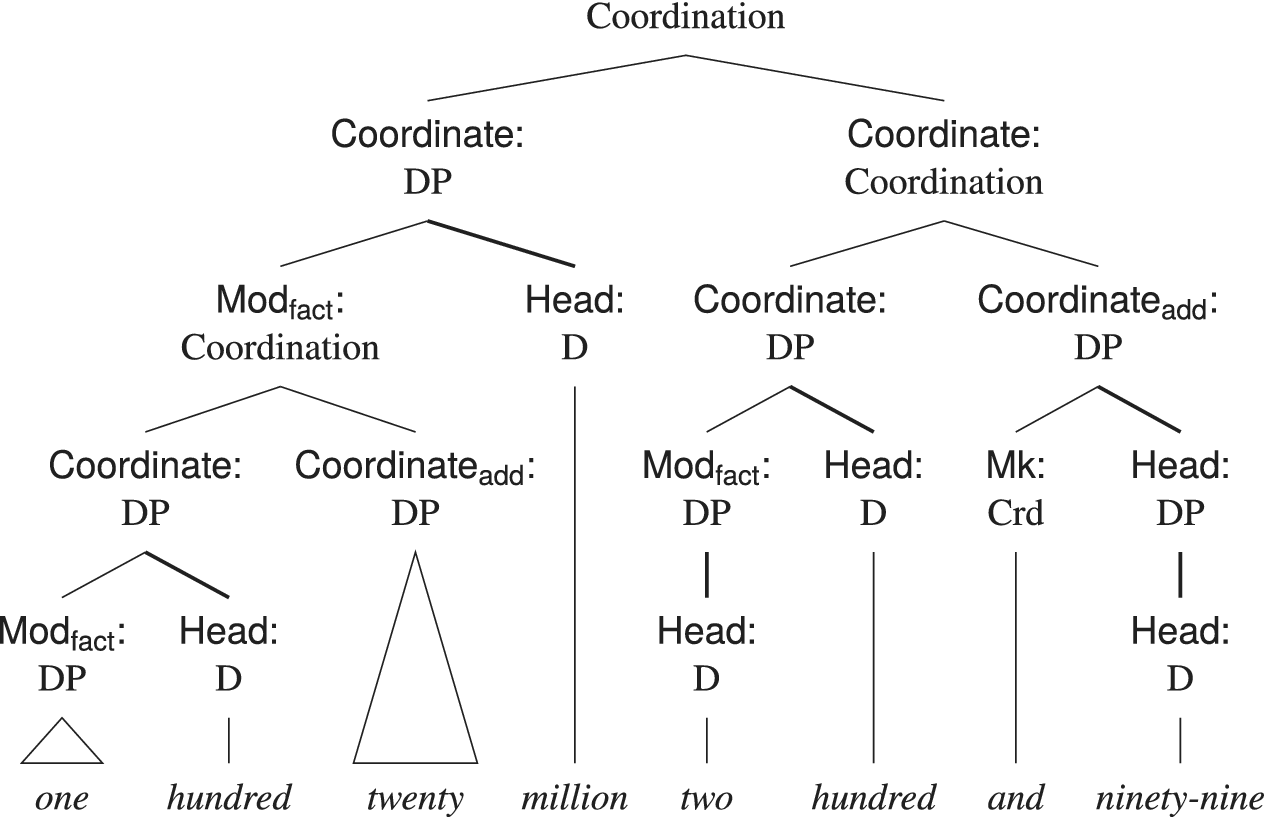

The syntactic structure of numerative DP coordinations is shown in figure 4. These structures are recursive, allowing numerative DPs such as two thousand and seven to function as additions within larger expressions like three million two thousand and seven.

Figure 4. Tree diagram for one hundred twenty million, two hundred and ninety-nine

5.2. Proper nouns (cardinal)

CGEL categorizes cardinals as both determinatives and nouns, but remains ambiguous regarding their categorization as common or proper nouns. I propose a principled distinction: cardinal nouns are proper nouns when denoting mathematical entities or acting as unique identifiers and are common nouns in quantificational contexts. This duality aligns with systematic noun alternations elsewhere in English (e.g. China proper versus china common).

While the idea that cardinal numerals are proper names traces back at least to Frege (Kremer Reference Kremer1985), to my knowledge, the explicit claim that they constitute proper nouns is novel and so requires careful justification. Proper nouns are lexemes within the category noun ‘specialized to the function of heading proper names’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 516, my emphasis). Proper names themselves are characterized semantically as:

nominal expressions that refer uniquely to one specific extra-linguistic entity. For this reason, proper names (or simply, names) are rigid designators in the sense of Kripke (Reference Kripke1980). Unlike common nouns, which have descriptive content and denote concepts, proper names don’t have lexical meaning (or at most to a very limited extent); accordingly, the relation between name and referent is direct and not mediated via the lexical content as in the case of common nouns. Semantically, unique and direct reference can therefore be regarded as the defining properties of proper names. (Schlücker & Ackermann Reference Schlücker and Ackermann2017: 310)

As Wiese (Reference Wiese2003) observes, numeratives exhibit precisely this type of semantic behaviour when they assign entities to abstract mathematical quantities through Representational Measurement Theory. Just as Canada directly denotes a specific nation-state, seven in mathematical contexts rigidly designates a particular abstract quantity via what Wiese terms ‘nominal number assignment’ – a linguistic counterpart to Kripke’s (Reference Kripke1980) direct reference theory.

This pattern of direct reference extends naturally to non-mathematical naming contexts:

In these examples, cardinal nouns function similarly to capitalized proper names, identifying unique entities through direct reference rather than descriptive content.Footnote 8 So, Room 101 Footnote 9 refers consistently to the same room across all possible worlds, and 1066 refers consistently to the same year,Footnote 10 precisely as Paris refers to a unique city.

Not only do these numeratives have the semantic properties of proper names, but they also have distributional properties that are typical of proper nouns, rather than common nouns:

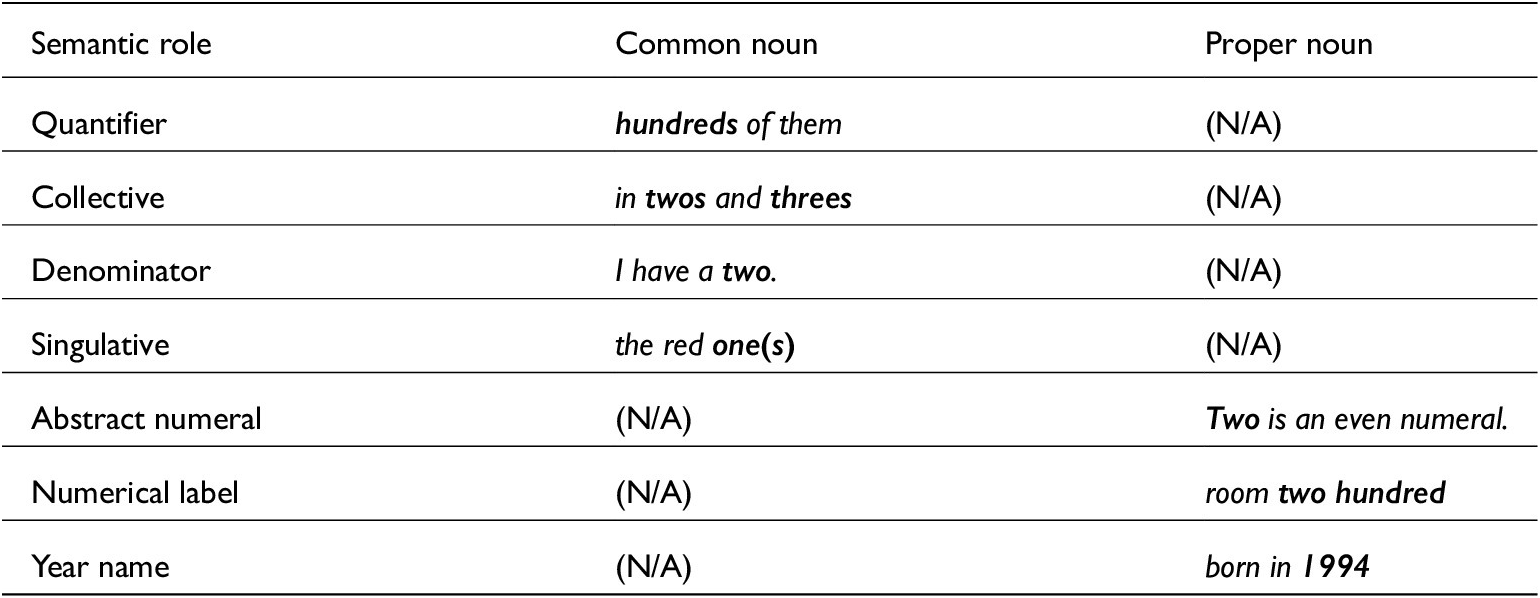

Cardinal nouns in the senses used in (7) head bare NPs (8a), resist determiners (8b) and attributive modifiers (8c), and don’t license of-PP complements (8d). These tests distinguish proper and common cardinal nouns, aligning with their semantic roles, as summarized in table 2.

Table 2. Semantic roles of numerative nouns

Figure 5 shows the structure of cardinal proper nouns. Unlike determinatives, this subcategory has a simpler structure because morphological constraints limit compounding: only determinative decade bases combine with single digits to form compounds like twenty-two. Double-digit bases cannot participate (*twenty-twelve), preventing parallel formations in other categories (*fiftieth-fifth for ordinals).

Figure 5. The structure of the lexical subcategory of proper nouns

The syntactic relevance of these distinctions is straightforward: magnitude words license factors, basic numeratives (1–99) can function as additions, and zero patterns uniquely in being unable to serve as an addition.

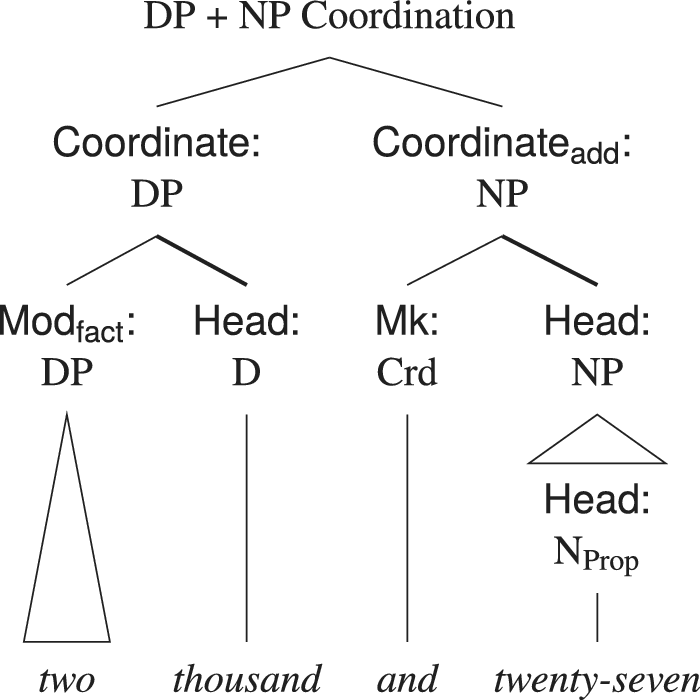

The structure of cardinal NPs is illustrated in figure 6. This structure, again, is recursive, allowing for the construction of arbitrarily large numeratives. Although the coordinate categories differ (DP + NP), ‘a difference of category is generally tolerated where there is likeness of function’ (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1326). This principle demonstrably holds here in the construction of the overall numerical value by denoting additive components of the total quantity.

Figure 6. Tree for two thousand and twenty-seven. Only the final coordinate is an NP

5.3. Common nouns (cardinal)

5.3.1. Basic properties

The common cardinal nouns display the following properties. Semantically, they typically denote abstract numeral concepts, labels and identifiers, and quantities in mathematical contexts. They head nominals (Nom) that primarily function as heads or modifiers in NPs. They license the same range of modifiers as other nouns (plus factors), along with of-PP complements, chiefly for tens or plural magnitude nouns (e.g. tens of cats but not *ten thousands of cats. This construction differs from the partitive (two of the cats), in which the numerative is a DP in fused-determiner–head function. Factors aren’t obligatory in cases such as hundreds of people. The cardinal nouns are count nouns and inflect for number.

The cardinal nouns have the same membership as the determinatives, but without the numerical–singulative distinction for one. Pro-nominal one (I’ll take these ones) and pronoun one (One should be explicit) aren’t among the numeratives (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1513).

The structural difference between proper-noun and common-noun cardinals manifests in the NP structure. The first tree in figure 7 shows a proper noun heading a bare NP, while common cardinals form determined NPs, as in the figure on the right.

Figure 7. Syntactic structures for (left) proper and (right) common cardinal nouns

This analysis resolves CGEL’s ambiguity by recognizing cardinal nouns’ dual nature: proper when rigidly designating mathematical or named entities, common when quantifying. It accounts for their syntactic, semantic and spoken-form duality without invoking homophony or ad hoc mechanisms, thereby preserving CGEL’s framework while refining its noun categorization.

5.4. Common nouns (fractional)

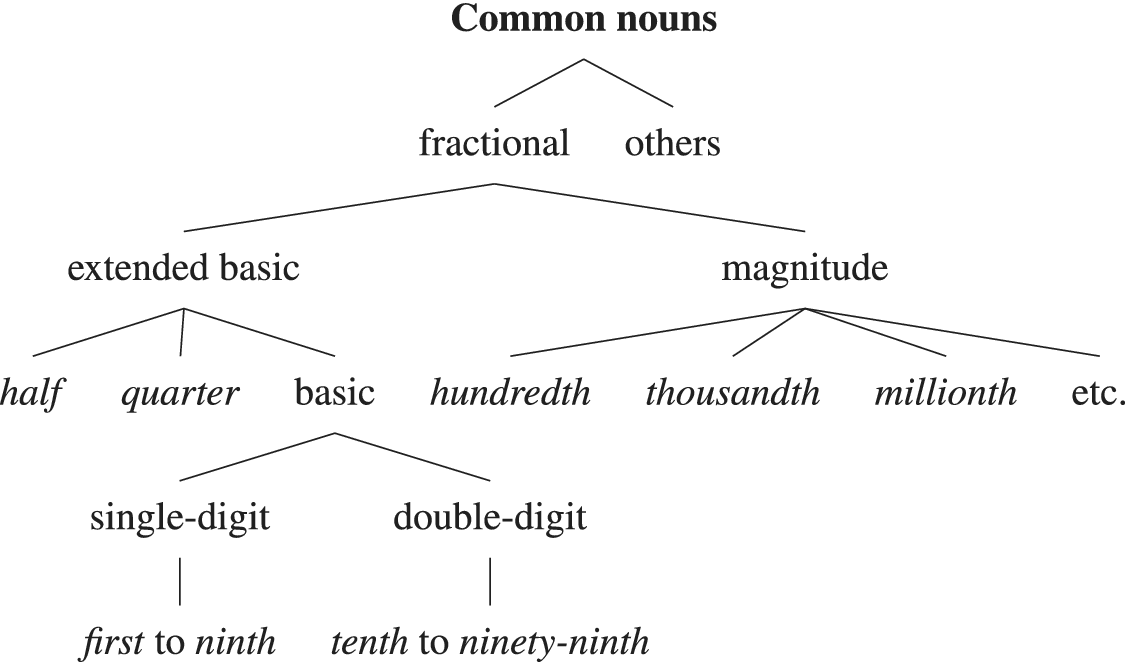

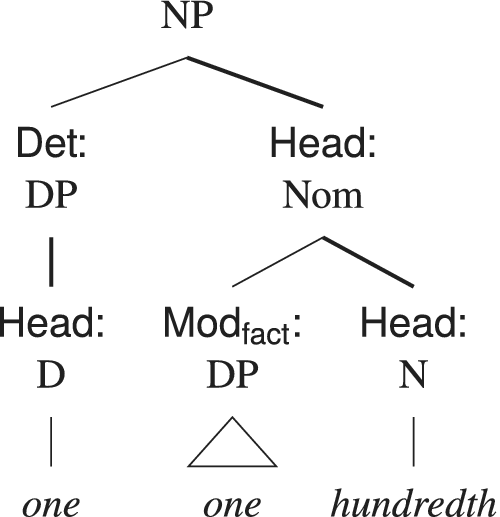

Fractional nouns display the following properties. They typically have partitive semantics and predominantly denote denominators. Fractionals head nominals (Nom), which primarily function as heads or modifiers in NPs with the semantics of fractions. They license the same range of modifiers as other nouns (plus factors). In a fraction such as one-fifth, the numerator is a DP functioning as determiner in the NP, not a factor as in one hundred. The head noun is the denominator. They are derived from cardinal nouns, but there is no fractional *zeroth. *Oneth is suppleted by first (from foremost), which occurs only in complex or compound fractionals (e.g. one *(twenty)-first). Half and quarter can’t be used in compound numeratives, which use second and fourth instead (e.g. one twenty-second vs *one twenty-half). Fractionals are count nouns that inflect for number.

Figure 8 shows the categorial structure of fractionals within the common nouns. The tree diagram for the fraction one one-hundredth appears in figure 9.

Figure 8. The structure of the lexical subcategory of common nouns

Figure 9. Tree diagram for the fraction one one-hundredth

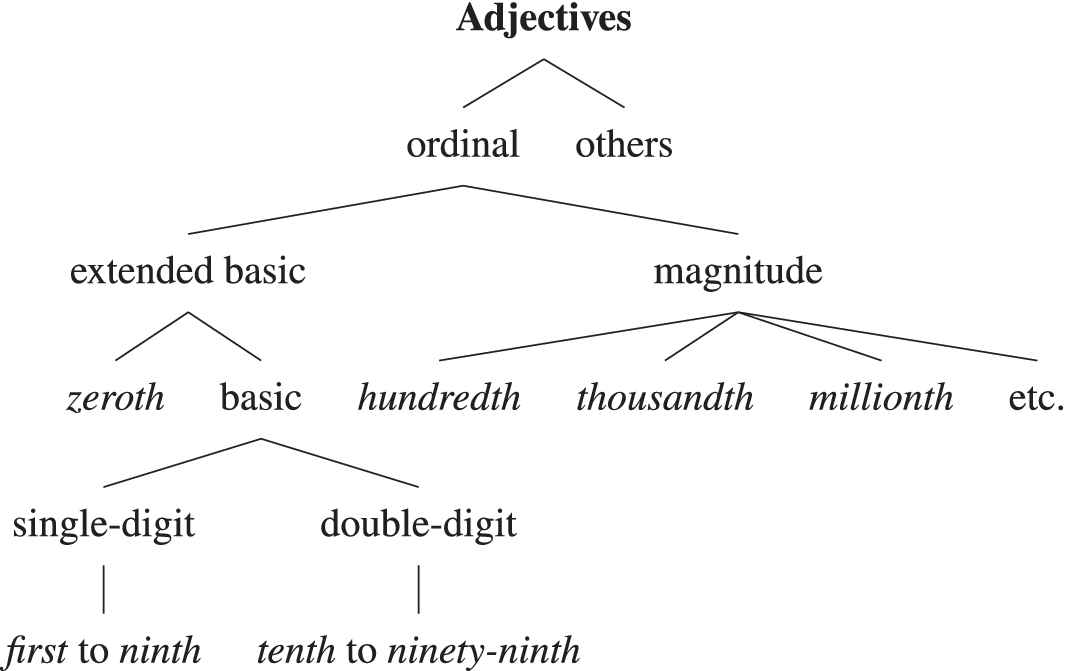

5.5. Adjectives (ordinal)

Ordinal adjectives display the following properties. They typically describe ranks or positions in sequences. They head AdjPs that primarily function as modifiers or fused head–modifiers in NPs or as predicative complements in VPs. Ordinal adjectives don’t license the same range of modifiers as other adjectives. Notably, they don’t license -ly AdvP modifiers (e.g. *We came closely second. Very first contains the same very as in the very person I wanted, which isn’t the adverb.) Ordinals license factors along with PP complements (e.g. second of all, first among them), though these are more natural with the lower-valued members. They don’t inflect but can produce adverbs such as secondly. Footnote 11

Apart from the fractional forms half and quarter, ordinals correspond directly to fractionals, each pair being homographic homonyms. Additionally, the ordinal zeroth occurs mostly in specialized contexts, such as physics or mathematics.

The structure of ordinals within the adjective category is given in figure 10.

Figure 10. The structure of the lexical category of adjectives

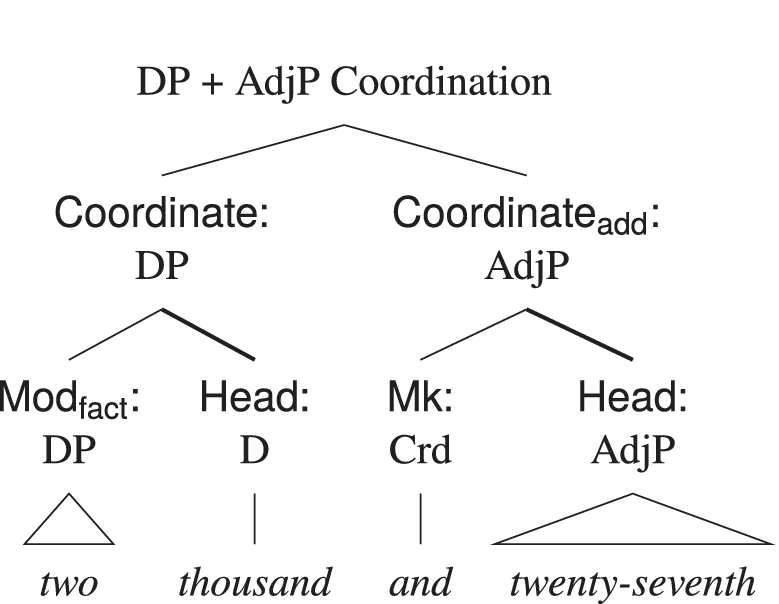

Figure 11 illustrates the internal structure of the coordination two thousand and twenty-seventh, showing that only the final constituent (twenty-seventh) is an adjective.

Figure 11. Tree diagram for the DP + AdjP coordination two thousand and twenty-seventh

6. Conclusion

I’ve argued for a morphosyntax-sensitive, CGEL-compatible hybrid analysis of English numeratives: extended basic numeratives (0–99) are lexical items, while larger expressions are syntactic – multiplicative pieces are factor–magnitude phrases headed by the magnitude, and additive material is coordination (binary, right-branching). Various independent diagnostics converge on one constituent. This boundary is precisely the one that Ionin & Matushansky’s cascading NumP + NP-deletion architecture denies for English; any repair they might adopt recreates the very constituent I posit overtly.

Within CGEL’s categorial inventory, the analysis sharpens rather than overturns commitments: factors are modifiers, not determiners or complements; additions are genuine coordinates; the determinative lexicon is a small, closed set (extended basics plus magnitudes) instead of an unbounded list of ‘numeral lexemes’. On the nominal side, cardinal nouns split systematically into proper nouns (for mathematical/label uses) and common nouns (for quantificational uses), with ordinary distributional diagnostics distinguishing them. The HPSG mapping (Smith Reference Smith, Webelhuth, Koenig and Kathol1999) falls out cleanly once post-magnitude ‘complements’ are reanalyzed as coordinates: factors correspond to specifiers, magnitudes to heads and additions to coordinates.

The account explains why English looks lexical below 100 but demands overt syntax above it, why ordinal and fractional morphology always targets the rightmost simple base, why prosodic breaks and ellipsis sites align with that same edge, and why forms like *twenty-twelve are blocked while twenty-one is lexicalized. It also predicts the tight coupling between orthographic hyphenation and the lexeme/phrase divide, without treating orthography as a primary diagnostic.

In short, once English ordinal/fractional morphology is taken seriously, the grammar forces a constituent that collapses non-constituency architectures back into the structure I adopt. The result is a tighter division of labour: a genuinely small closed lexicon of determinatives, plus exactly as much syntax as English independently signals through morphology, prosody and ellipsis.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Peter Evans, Nathan Schneider and Geoff Pullum for helpful comments. I used ChatGPT o3 (OpenAI, Apr 2025) and Claude 4 (Anthropic, May 2025) extensively, restructuring an earlier draft and drafting new sections and many paragraph-level passages. I reviewed, edited and approved all the material and take full responsibility for the final text and conclusions.