Introduction

The emergence of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to the adoption of unprecedented social distancing policies across the globe. In Canada, federal, provincial, and municipal government interventions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 were put in place in early 2020, with community non-essential services closed down in March of 2020 (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). While critical to decreasing the spread of the virus, social distancing and other COVID-19 policies disrupted daily activities for many who are unable to participate in their usual in-person activities and daily routine (Mynard, Reference Mynard2020).

Occupations are tasks and activities that people perform in the course of everyday life, that hold value and meaning, and that are a vital determinant of health and well-being (Townsend & Polatajko, Reference Townsend and Polatajko2013). Occupational disruption is a temporary or transient state of disruption of a person’s typical activity pattern of everyday life activities, as a result of extraordinary life circumstances (Whiteford, Reference Whiteford2000), with negative, and potentially devastating, effects on health (Nizzero, Cote, & Cramm, Reference Nizzero, Cote and Cramm2017). Older adults may experience occupational disruption as a result of retirement, caregiving, social losses, illness, or relocating to a long-term care facility (Nizzero et al., Reference Nizzero, Cote and Cramm2017; Whiteford, Reference Whiteford2000). Disruption of social or leisure activities (i.e., intrinsically motivated, non-obligatory activities, performed during discretionary time, with an aim of enjoyment [Squire, Ramsey, & Dunford, Reference Squire, Ramsey, Dunford, Curtin, Adams and Egan2017]) in older adulthood can have negative implications on health and well-being, as social and leisure activities are related to cognitive (Sharifian, Kraal, Zaheed, Sol, & Zahodne, Reference Sharifian, Kraal, Zaheed, Sol and Zahodne2020), mental (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yeh, Lee, Lin, Chen and Hsieh2012), and physical health, and general well-being (Chang, Wray, & Lin, Reference Chang, Wray and Lin2014). Disruption of social activities may result in social isolation, defined as having little participation in activities with others, or lacking social engagement (Holwerda et al., Reference Holwerda, Deeg, Beekman, Tilburg, Stek and Jonker2012).

Tyrrell and Williams (Reference Tyrrell and Williams2020) identified the paradox of social distancing, whereby older adults who are more susceptible to the COVID-19 infection, severe disease, and complications (Malone et al., Reference Malone, Hogan, Perry, Biese, Bonner and Pagel2020) become subject to health risks as a result of the policies intended to protect them. Social distancing and the disruption of daily activities and social interactions may have tangible effects on mental, cognitive, and physical health as well as the well-being of older adults (Robb et al., Reference Robb, de Jager, Ahmadi-Abhari, Giannakopoulou, Udeh-Momoh and McKeand2020). Understanding the profound impacts of social distancing policies on the lives of older adults is key in supporting their health and well-being.

Older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or subjective cognitive decline (SCD; i.e., the experience of decline in cognitive functions with no evidence for objective cognitive deficits [Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Amariglio, Buckley, van der Flier, Han and Molinuevo2020]) are at risk for future cognitive decline and development of dementia (Lehrner et al., Reference Lehrner, Bodendorfer, Lamm, Moser, Dal-Bianco and Auff2016), and even prior to the current social distancing requirements, are reporting withdrawal from social and leisure activities (Rotenberg, Maeir, & Dawson, Reference Rotenberg, Maeir and Dawson2020). With pre-existing risk factors, it is possible that occupational disruption, secondary to the COVID-19 policies, may carry negative implications for their functioning, health, and well-being. van Maurik et al. (Reference van Maurik, Bakker, van Den Buuse, Gillissen, van de Beek and Lemstra2020) found negative psychological effects of COVID-19 measures in approximately half of a sample of older adults with SCD and MCI, which included increased loneliness, anxiety, uncertainty, and depression. Concern regarding faster cognitive decline was reported by 14 per cent of older adults with SCD.

Focusing on this population, through interviews conducted in the early months of the pandemic (April–June, 2020), this article aimed to understand the experience of occupational disruption resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic policies. The participants in this study were community-dwelling older adults with SCD and MCI, who were participating in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) that was ongoing in March 2020, and had shifted to virtual delivery. O’Sullivan and Bourgoin (Reference O’Sullivan and Bourgoin2010) called for expanding the study of implications of a pandemic on disadvantaged populations beyond the medical aspects (e.g., disease transmission, symptomatology) in order to identify supports that can minimize its adverse effects. This is echoed in a joint statement by the Canadian Association on Gerontology and the Canadian Journal on Aging (Meisner et al., Reference Meisner, Boscart, Gaudreau, Stolee, Ebert and Heyer2020), stressing the importance of understanding the lived experience of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, through qualitative research that portrays their broad perspectives on issues beyond prevention of COVID-19 infection and disease. The current study addresses these calls and gives voice to older adults who have made drastic changes to their lifestyles to adhere to public health policies, and highlights the complex implications this has had on their day to day lives.

It is of note that occupational disruption and social isolation are not phenomena unique to a pandemic, and may be experienced as a result of other significant life events (Whiteford, Reference Whiteford2000). Social isolation among older adults has been recognized as a major public health issue, detrimental to quality of life and mortality in older adults (Smith, Steinman, & Casey, Reference Smith, Steinman and Casey2020). To that end, understanding the implications of occupational disruption and social isolation on older adults is essential in understanding factors related to the health and well-being of older adults (Courtin & Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017), even in the post-COVID era.

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of occupational disruption during a pandemic among community-dwelling older adults. The overall research aim was to describe the lived experience of community-dwelling older adults during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Toronto, Canada. The research questions were: (1) How do community-dwelling older adults understand and act on COVID-19-related public health guidelines? and (2) How do community-dwelling older adults perceive COVID-19-related policies and guidelines to affect their everyday life?

Methods

Design and Procedure

The study utilized a qualitative descriptive design, which aims for a rich, unfiltered, description of informants’ experiences, articulated in a language similar to their own words (Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen, & Sondergaard, Reference Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen and Sondergaard2009). The approach is suitable in health services research in which gaining the perspectives of vulnerable populations is a goal in and of itself (Neergaard et al., Reference Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen and Sondergaard2009). Insight into the perspectives and experiences of vulnerable populations is valuable for the development or refinement of interventions, for conceptual clarifications for assessment development, and for needs assessments (Neergaard et al., Reference Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen and Sondergaard2009). The qualitative descriptive design was deemed most appropriate for this study, as it aimed to gain first-hand knowledge of the experiences of community dwelling older adults during the pandemic, as a first step towards understanding how social services and health care providers can support older adults in maintaining their health and well-being.

This study was nested within a larger RCT (NCT03495037, unpublished), examining the efficacy of a strategy-based client-centered intervention in improving the daily functioning of community-dwelling older adults, performed in community and senior centres across the Greater Toronto Area. Participants receiving the intervention when COVID-19 policies were implemented and transferred to virtual training were invited to participate in this study at the end of their training period. An interview guide was developed by S.R. and reviewed by Y.B. and D.R.D. (see Table 1). The guide provided a general outline while allowing for unanticipated topics and ideas to emerge. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Baycrest Health Sciences.

Table 1. Interview guide

Participants

The inclusion criteria for the RCT were: (1) being community dwelling, (2) being age 60–85 years of age, (3) having confirmed subjective cognitive problems (defined by confirming at least one of the following questions: “Do you feel that you have problems with your memory or cognition?” and “Do you feel that your memory has become worse?” see Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Amariglio, Buckley, van der Flier, Han and Molinuevo2020), (4) being fluent in English, (5) having no current depression (Patient Health Questionnaire [Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001] score ≤ 9, indicating low levels of depressive symptoms), (6) having no self-reported neurological or psychiatric history and (7) no self-reported substance abuse, and (8) not currently receiving chemotherapy. Sixteen participants, of 19 approached, agreed to be interviewed and provided informed consent. Their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics

Note. Pt-X = Participant-X

Data Collection

Demographic data were collected using a self-report questionnaire. The qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews, lasting approximately 60 minutes. The interviews were conducted by S.R. or Y.B., both health care professionals experienced in working with older adults. The interviews were performed virtually, using the secure Ontario Telehealth Network (OTN) platform, or by phone, based on participants’ preference and Internet quality. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, 2018).

Data Coding and Analysis

Data coding and analysis were informed by Braun and Clark’s semantic thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), which involves identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. In line with the qualitative descriptive approach, the team of researchers met several times throughout the data coding and analysis stages to discuss emerging codes and themes in order to prevent researcher bias and to minimize subjectivity (Neergaard et al., Reference Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen and Sondergaard2009). First, the coders (S.R., J.S.O., Y.B.) familiarized themselves with the data by reading through the interview transcripts and noting possible codes, defined as words or sentences that contain an idea or piece of information. Second, the three coders generated initial codes using three transcripts, and developed a provisional code book, in an iterative process. We then coded the entire data set. Each interview was coded independently by two team members, S.R., J.S.O. and/or Y.B., and codes were added as they were identified. All coding was done using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, 2018). Weekly meetings were held to resolve discrepancies and discuss new codes that emerged. Data saturation was reached after 12 of the 16 interviews. The codes were consolidated into themes and then re-examined and revised several times through discussion between S.R., J.O., Y.B., N.D.B., and D.R.D. until a consensus was reached.

Participant quotes are presented verbatim to support the identified themes. Some quotes were edited to enhance clarity. Deleted words were replaced by an ellipsis (…) and information added by the authors to provide context, is enclosed in square brackets. The abbreviation Pt-X, where X represents the participant number as presented in Table 2, was used to identify the participant quoted.

Results

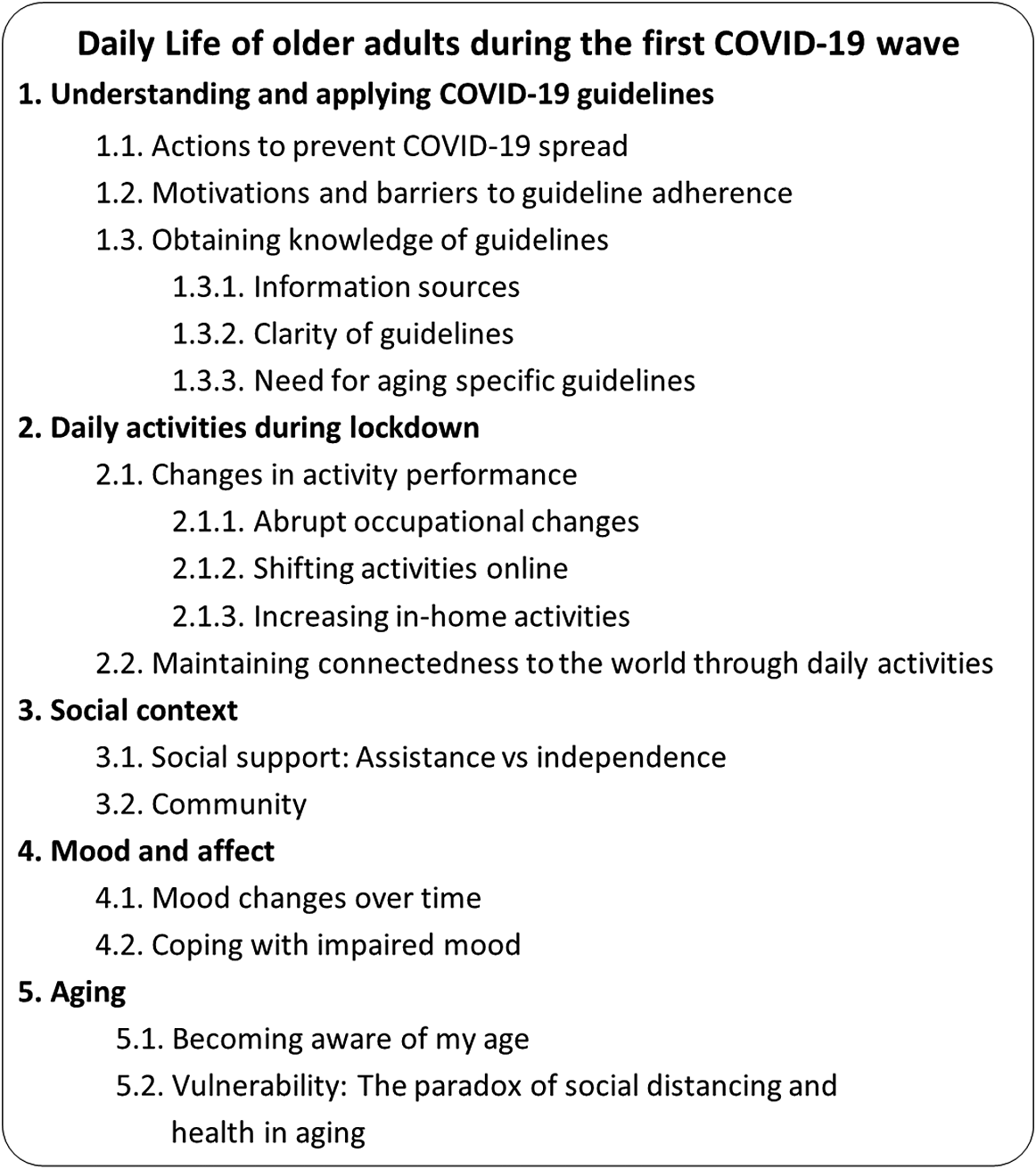

The following five themes, related to daily life of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, were constructed from the data analysis: (1) understanding and applying COVID-19 guidelines, (2) daily activities during lockdown, (3) social context, (4) mood and affect, and (5) aging. Each of the themes encompasses several sub-themes, presented in Figure 1, and detailed in the following sections.

Figure 1. Thematic analysis.

Theme 1: Understanding and Applying COVID-19 Guidelines

Theme 1 describes actions taken by participants to prevent COVID-19 spread and the rationale behind them, ways that participants obtained information about COVID-19 policies, and their thoughts on clarity of the policies.

Actions to prevent COVID-19 spread

Participants mentioned implementing public health guidelines as advertised at the time of the interviews, including social distancing, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE; e.g., face-masks, gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitising. Based on their understanding of the guidelines, participants sanitised items brought to their homes, including their shoes, walking cane, and groceries. One participant cancelled a newspaper subscription he had had for many years for fear of bringing COVID into the home, and another left her newspaper on the counter for a week before reading it.

Several participants mentioned taking actions knowing they were exceeding recommended measures. These included adding items to the recommended PPE, such as glasses or a hat, and spraying alcohol on a facemask and gloves before entering a store. Several participants avoided leaving the house for extended periods of time, ranging from 4 weeks to 3 months. Pt-14 took herbal medications as “a natural product that I believe helps me to be a little bit ahead of the curve where the virus contact might potentially be an issue”.

Motivations and barriers to guideline adherence

Several reasons were mentioned for adhering to the COVID-19 guidelines. Predominantly, participants saw this as a way of reducing risk and protecting themselves, and were motivated to implement social distancing by fear and anxiety of severe illness or death, related to their age and to having other health conditions.

I have asthma, allergies, sensitivities… if I catch it I’m in big trouble… I don’t want to catch COVID because I don’t think I have the defences to deal with it, and because people seem to die really fast… So I consider myself high risk. And I’m not death ready… so that’s what I’m afraid of. (Pt-16)

Other reasons for taking action were persuasion or pressure from family members and/or friends. Others were motivated by a feeling of social responsibility: “you don’t wanna become part of the problem… the hospitals are already overwhelmed, so don’t do anything stupid” (Pt-10). A unique view was voiced by Pt-15, who was not concerned about catching COVID-19, and was the only participant who had indoor social interactions with people outside of his household. He, too, however, adhered to some social distancing guidelines to avoid upsetting his social network.

Participants encountered some obstacles in adhering to the guidelines. First, some had difficulty purchasing PPE or disinfectants: “I tried to buy and they were out, so I don’t have the masks. So the only thing I do is put the gloves on.” (Pt-11). Another challenge was not having the conditions to adhere to the guidelines. For example, Pt-3 described difficulty keeping 6-feet distance from other people while outdoors: “I do go out for walks, usually by myself. But of course, the streets can be crowded. Especially where I live. I live in a very active part of the city.” Two participants felt that they had no choice but to disobey the guidelines and interact with other people indoors, in order to get their household chores done. Pt-3 was doing her laundry at a friend’s house, feeling that it was safer than going to a laundromat: “I don’t have laundry facilities here. So what I do is I go up her [friend’s] back stairs. I go in and use her laundry facilities, and then I sit at the top of the stairs and she sits down in the garden and we talk.”

Obtaining knowledge of guidelines

Information sources. The main sources of information about COVID-19 guidelines were television news broadcasts and news Web sites. Some participants followed multiple news channels, including international ones “just to see what’s going on in the world” (Pt-5) or out of interest in their country of origin and/or a country where they have family. They chose television networks and Web sites that they considered trustworthy. Another source of information was government Web sites and social media outlets. Participants regularly followed formal messages at the federal, provincial, and municipal levels through relevant Facebook pages, and televised messaging. Less frequently mentioned sources of information were family or friends, the person’s general physician, street signage, flyers in the mail, and a police officer.

Clarity of guidelines. As a whole, the participants felt that the guidelines were presented clearly and repeatedly enough such they knew what was expected of them. Some uncertainty was expressed regarding the number of people allowed to gather outdoors or the effectiveness of surgical masks and gloves. Some were concerned that they might have been missing information. One participant was confused by what she experienced as contradicting information between the media and a police officer

I was walking sort of near the entrance [to a park] and I saw the police officer… and he said you better leave in about five min ‘cause they’re coming to close the park down and you’re going to get a ticket. And I said when did this take effect?… I said to him, you know officer, I didn’t hear about this… It’s not what I had read in the paper. (Pt-2)

Need for aging specific guidelines. Participants felt that there was a need for guidelines from the government about how family members could safely support them with necessary daily tasks that require the presence of another person in the home, such as helping out with cleaning, laundry, and other housekeeping tasks: "If guidelines like that were given… seniors… would not panic thinking they were putting their children at risk or their children were putting their parents in risk." (Pt-14). They also expressed disappointment that government guidelines did not address the need to maintain general physical health, address mental health, and/or the importance of maintaining activity levels of older adults. Some thought the government should actively address the contradiction between current social distancing guidelines, and long-standing health recommendations for older adults (see more details on this topic under the sub-theme “Vulnerability: The paradox of social distancing and health”).

Theme 2: Daily Activities During Lockdown

Theme 2 describes how participants’ engagement in daily activities changed as a result of the lockdown, including a shift to online activities and increased daily activities at home. It also highlights how performing some out-of-home and/or in-person activities helped participants maintain connectedness to the world.

Changes in activity performance

Abrupt occupational changes. The social distancing guidelines and closure of public spaces, community centres, and social services resulted in an abrupt disruption of daily activities typically performed outside people’s homes, or indoors with others: “So one day, everything got cancelled” (Pt-10). Participants reduced the frequency or stopped performing activities such as social interactions (e.g., going out to restaurants, babysitting grandchildren), leisure or hobby activities (e.g., playing bridge, going to the library), work, physical activities (e.g., going to the gym, swimming), volunteerism, and informal education (e.g., courses). Many participants were used to a highly active lifestyle that included multiple regular and spontaneous activities that they now missed. Some were bothered by the lack of activity choice, more than missing specific activities: “I kinda joke about this, I say, you know I can’t wait till things go back to normal so I can stay home by myself on purpose” (Pt-16)

To cope with the sudden halt of social activities, participants frequently met with family members or friends outdoors, while keeping socially distanced: “My buddy… came to the house a couple times… and we just had a driveway discussion” (Pt-5). Participants planned their meals to minimize the frequency of grocery shopping, such as Pt-10 who increased the consumption of canned and frozen foods. In some cases, participants refrained from activities available to them, like riding their bicycle or cutting firewood, for fear of getting hurt and requiring medical attention.

Also related to the abrupt change in activity level, many participants described a feeling of boredom, and having lack of daily structure, low productivity, and reduced energy levels: “I usually just putter around, cook. Try to do some cleaning. Sometimes do nothing… So my day is pretty much just not very much.” (Pt-2). Pt-15 said: “I don’t have Corona but I’m dying of boredom.” They highlighted the importance of keeping busy and having a daily structure: “[I say to myself] you need to do something now! And what of the things that you enjoy doing do you want to do now? And I would pick one and do it.” (Pt-14). Efforts to keep active while in lockdown were motivated by a desire to maintain self-worth: “I need some stimulation in my brain so I don’t feel I was useless. ‘Cause I think it’s very easy to feel… you kind of just are losing what you’re worth” (Pt-9).

Shifting activities online. Participants shifted many out-of-home activities to various virtual and/or digital platforms. Some of the activities performed virtually were grocery shopping, social-leisure activities (e.g., music lessons, investment club, games), and physical activities. In many cases, this was because of a lack of other options: “Well, I’ve done online shopping, which I normally never do… I think it’s a pain in the butt. It takes an hour just to select your items. You can be in and out of the store” (Pt-2). Pt-2 described how she and her friends transferred from in person to virtual card games.

We used to get together at each other’s home, every week… 2-3 times a week… Now we have a system. One of us will be the lead every time to make the conference calls to everyone else. We’ll all get on the [web]site about the same time… Somebody will create a table and we’ll join the table… so we got it down to a bit of an art. (Pt-2).

Technological challenges. Participating in online activities was not trivial for many participants, who found it challenging and felt they lacked the required technological proficiency, because of their age: “I don’t wanna play with a computer… I want to play with the person that I played with. I’m not that… technically proficient to be able to do so, so I can’t do that.” (Pt-7). Technological issues such as poor or inconsistent Internet connectivity, sensory deficits (e.g., poor hearing), and discomfort from prolonged computer use (e.g., headaches, vision discomfort), also restricted activity options. Pt-4 described losing touch with friends who did not have access to technology: “I’ve got some friends like 80ish… They don’t really want to talk on the phone. They don’t know how to use the technology to Facetime”. Participants described initially being excited and interested in the opportunities for online activities, but growing weary of those over time.

The experience of online activities. Although participants were happy to have activities available online, they often found virtual activities to be less efficient and not as enjoyable or fulfilling as in-person activities. Virtual social interactions were experienced as inferior to in-person meetings. Pt-5 described virtual meetings with his grandchildren: “It’s difficult… when you see the kids… you really feel like you wanna touch them”. The quality of social interactions with grandchildren was lacking because it was limited to virtual conversations rather than shared activities like playing or dining together.

Despite the challenges related to virtual social interactions, there was a unanimous agreement that they met at least some of the need for social connection: “I live alone, and so I’m spending a lot of time online, as much as I can… I really miss that [meeting people] a lot… I do keep connected online. Thank goodness I’m able to do that” (Pt-7). Keeping in touch virtually required more effort than in-person socializing: “You go out with a group of 10 people. It’s easy, you just socialize. but now I wouldn’t make an effort to call each one” (Pt-9).

Despite the general preference for in-person activities, some participants found advantages to activities online. For example, eliminating the need to travel allowed participants to attend more webinar classes than they would have been able to attend in person: “it’s easier for me without travelling time… to have a full schedule of Zoom activities” (Pt-16). Pt-16 also enjoyed online exercise classes with her instructor more than she did when they were in person: “Actually it’s easier to go to his classes… online… because I can do things at home that I can’t do if I’m physically there. I’m not self conscious, it’s a webinar so he can’t see… nobody can see you. You see him, he talks to you.”

Increasing in-home activities. The abrupt cessation of out-of-home activities and consequent boredom brought about an increase in in-home non-virtual activities, in addition to the virtual activities mentioned. Participants reported an increase in leisure activities, such as crossword puzzles, reading, and listening to music; however, those were mostly described as a compromise compared with out-of-home leisure activities. On a more positive note, a few participants engaged in activities they had put off in the past, such as sorting old pictures, organizing books for donation, decluttering, or writing a book. Additionally, a number of participants initiated new activities. Pt-3 described becoming more politically active on the Internet, and Pt-16 became more involved in religious and spiritual activities online. Some took up old hobbies: “So today I… got my husband to bring up the sewing machine and made masks.” (Pt-1).

A few participants increased the time spent on home maintenance, such as cleaning and cooking, because they suspended outside paid cleaning help, and were not able to dine out. Others, on the other hand, felt reduced motivation to clean their house because they were not receiving visitors. Household activities were mostly described as burdensome, although some saw this time as a positive opportunity to declutter their home. Another positive outcome was healthier eating: “I can’t… go [out] and eat junk food lunch now, can I?” (Pt -15).

Participants described an increase in time spent on sedentary activities, because of both boredom and the shift of activities to virtual platforms. In addition to online activities, many participants watched more television than they would have liked: “I did get lost in Netflix when it first started, soap operas, movies… too much Netflix” (Pt-16). Watching television or online videos (e.g., YouTube) were described as ways to pass time and distract from COVID-19-related stressors, but were also viewed as a waste of time and were, for the most part, not fulfilling activities. There was an increase in news consumption from before the lockdown, explained by a need to be informed of the COVID-19 status and ongoing changes to guidelines. Many described spending significant amounts of time watching or reading news in the first few weeks, but found this overwhelming and experienced adverse emotional effects. Exposure to news was described as distressing, concerning, overwhelming, and depressing, and as making them feel hopeless: “The news is overwhelming. You can only do [watch] so much… following the Canadian [news] it’s pretty hard not to take in the fact that in some areas of Ontario we’re in quite a mess.” (Pt-10)

Many gradually decreased the time spent on news:

I overdosed on it in the first week or two…. and I cut myself back because I didn’t wanna hear it anymore. It was the same old thing. So now… I’ve disciplined myself… to just concentrating on certain sources… at very specific times… Other than that, I don’t wanna hear about it. If it’s constantly in my face I don’t like it. (Pt-6).

Participants were frustrated by deteriorating fitness as a result of stopping out-of-home physical exercise and performing more sedentary activities: “I used to be able to keep myself in really good shape, playing hockey twice a week, working out two or three times a week. But I feel that I’ve really let that slip badly, and I don’t know what to do about it.” (Pt-5). A small number of participants, however, increased the time spent on physical activity, such as walking or doing yoga, because they now had more time.

Maintaining connectedness to the world through daily activities

Participants explained how performing daily activities out of the home served two different, yet related, purposes. First, going out was an opportunity to experience the new reality: “We went for a drive downtown just to see what the dead streets…they were really dead” (Pt-5). Seeing the new reality firsthand was helpful in alleviating the anxiety related to it.

You have to go out there at some point to see what is happening. It’s like putting your toe in the water and feeling it to see, you know?… The world is different, and you are very careful… but you can actually look at… what is available and new. (Pt-10)

Second, participants engaged in outdoor, socially distanced, in-person meetings to maintain a sense of normalcy in connecting to their pre-COVID world: “Honestly, it was nice just to be able to talk to somebody in person. I didn’t care if it was six feet apart. It made you feel like, oh my god, some part of the real world. …” (Pt-10). Gardening and being outdoors in good weather were enjoyable for many, and helped in supporting a sense of normalcy by enabling them to perform activities that remained unchanged.

Theme 3: Social Context

The third theme presents participants’ understanding of the tangible and/or emotional social support that they received from their social network and on the community level.

Social support: Assistance versus independence

Many participants received help with daily activities, mainly from their adult children, or from a neighbour or friend. Many expressed mixed feelings regarding assistance; they were appreciative, yet also frustrated by the dependence imposed on them by the situation or by their children. Many felt that the help that they were getting was not necessary, and, in some cases, forced on them: “my son… is concerned because of my age. I think I’m perfectly fine, but he’s persistent about doing the grocery shopping for me” (Pt-9); “They’re [children] very adamant - don’t go out, don’t do anything, stay home, we can bring the stuff in. They’re like mini security police *laugh*” (Pt-10). Relying on children made participants feel dependent and also concerned about putting their children at increased risk for COVID-19.

I ordered some things online and they need to be mailed back, but I can’t go to the post-office. So I have to depend on my kids to take it back to the post office. And my children are so bogged down right now with their jobs and their kids at home that I have a very hard time asking them to do something for me. And yet at the same time, they told me they don’t want me doing those things. (Pt-12).

A few participants, previously receiving paid help with household management (e.g., grocery shopping, laundry), found themselves without help because of the lockdown. Receiving the necessary help at home while following the social distancing guidelines was challenging.

I have trouble with stairs, so I couldn’t get downstairs [to basement] to do my laundry. I went downstairs on my hands and knees to get my laundry done…. Trying to make my bed was also a struggle. All of those things became problematic… and having PSW [personal support worker], I had to discontinue that, I didn’t want to have that risk. I had to say to my children if I have my windows open when you come and I am going to sit in the back bedroom and… you wear a mask… could you come and take my laundry out of the dryer, bring it up and make my bed and go!… I made sure that everything that they would maybe touch was alcoholed with my spritzer. (Pt-14)

Family members and friends also provided emotional support and encouragement to their loved ones to be active and engaged in activities: “If left to my own devices without my wife, I would probably watch TV a lot more, but… she also is an inspiration to go out and exercise… she just makes lists, a honey-do list” (Pt-5).

Community

Participants’ sense of safety out of home was dependent on the behaviours of others in the community. They often felt unsafe when store owners did not fully enforce COVID restrictions in their stores, or when other people did not keep enough distance. As a result, many participants did not feel comfortable being in public places, and experienced stress and fear related to going out. They sometimes avoided activities that made them feel unsafe. One participant started taking her walks at 5 a.m. to avoid crowds on the sidewalks and in the ravine near her house.

When going out, many felt vulnerable because of their age-related physical limitations: “I stay away from people… It’s like a game of dodgeball… people are… coming too close to you and I’m a little slow because I’m older.” (Pt-16). Participants felt that careless behaviour was more typical of younger people, and preferred shopping during a “seniors only” hour. Careless behaviour by younger people was perceived as reflecting ageist attitudes.

I find that the young people are careless. They don’t move to let you by… They just have this ‘get out of my way’ attitude. I think that ageism is a big problem in society… even on the street when they’re jogging they don’t move. They just come right at you, and they don’t have a mask on, so I always cross the street… as soon as I see them. (Pt-4)

Theme 4: Mood and Affect

Theme 4 captures how participants understood the implications of the COVID-19 policies on their mood over time, and the coping strategies they employed to improve or maintain a positive mood.

Mood changes over time

Three main trends were identified in relation to participants’ mood during lockdown: generally good, generally poor, or fluctuating. Those who described their mood as good attributed it to a general positive life disposition: “I’m a very optimistic person. I’m a happy guy… and I haven’t irritated easily since COVID has come on… Some of the routine has changed… but generally speaking, I had a good life before and I have a good life after." (Pt-6). Two participants noted feeling depressed for the duration of the lockdown because of reduced physical and social activity levels: “I find it depressing as… I am really a physical person, and also a social person. And I’m finding this extremely difficult… I’m suffering with this.” (Pt-1)

The majority of participants described some fluctuations in their mood. Some felt anxious or sad during the first few weeks of the lockdown, to the extent that it impacted their functioning, but their mood improved with time.

It was tough at the first month and a half. …don’t feel like getting up, and what’s the point. And you stop changing your pajamas. I just felt lazy, and I ate more junk food, easy food, rather than spending some time cooking and preparing some better food. I think it eventually got back. Now I’m in a much better place. (Pt-9).

Others experienced a decrease in mood later, as the lockdown was repeatedly extended. They were concerned about the prolonged and unpredictable duration of the lockdown, and about its possible long-lasting effects. Many felt that their well-being would be severely impacted if the lockdown continued: “the uniqueness is wearing off and now it’s becoming more a feeling of ‘oh my god is this will never be over’… Mentally it’s…I don’t know [sigh]. Another month of this? Wow… people are really gonna start to feel it after that.” (Pt-10). In addition to sadness related to disengagement from previous activities and relationships, participants were worried about financial, physical and mental health implications on them, their families, and society in general: “what it’s going to do to the economy… It concerns me… our kids are gonna have real difficult times.” (Pt-5).

Coping with impaired mood

Participants used several coping strategies to maintain a good mood. First, participants re-framed the situation in ways that supported their mood and helped reduce anxiety. For example, some found that looking at the lockdown as a temporary state, focusing on the hope of returning to normal life, and having plans for enjoyable activities in the future (e.g., vacation) supported their mood. Others found comfort in knowing that they were better off than older adults living in long-term care facilities, a friend living with a partner with dementia, or younger people who had lost their source of income. They expressed appreciation and gratitude for positive things in their lives, which helped them shift their focus away from things that were out of their control: “Look at the bright side, I have a roof over my head, I have food in my fridge, I don’t have to worry about paying the rent. It could be a lot worse and I choose to look at it that way.” (Pt-8).

Second, participants took actions to maintain a positive affect, such as minimizing their news consumption, performing calming activities (e.g., eat ice-cream, take baths, listen to music), performing leisure activities (e.g., gardening, reading, playing games), or exercising, interacting with others, and being outdoors (e.g., backyard, ravine). Having a daily routine also supported a positive mood.

At times like this you really need to keep your routine, so you’ll have as much of a normal life as you can. I have a routine. I exercise, I do things, and I fill my time with something I think is a bit more challenging… and not going into lazy mode. (Pt-9)

Pt-14 thought that more information about the accessibility of mental health supports was required, and, more importantly, a message legitimizing reaching out for such supports.

I would have suggested that the government may have had on those panels that they had initially, a psychologist… [saying] it’s okay to be needing the help of a psychologist. There shouldn’t be any stigma associated with reaching out for help. (Pt-14).

Theme 5: Aging

The last theme describes thoughts, beliefs, and feelings expressed by participants about the role that their age played in their experience during the first pandemic wave.

Becoming aware of my age

Participants talked about the unique experience of being an older person during the pandemic. Many felt that because their age group was at a higher risk for severe disease and death as a result of the COVID-19 virus, their age had become a more meaningful factor in life choices, such as going out, than it had been before:

I’m just becoming more aware of my age. Although I’m fairly healthy… But one report really struck me, where one man… was quite seriously ill. He said he had only gone to the grocery store once. You just never know. I am masked, I am gloved, but… is it really worth it to get some food? (Pt-6).

Participants thought that being forced to disengage from daily routine was especially difficult for older people who had fewer years left to live, and often lived alone, and that a higher priority should be placed on recommencing in-person activities for older adults, with precautions.

People need to die of something. It’s sort of the way of the world. It’s not a good thing, but it’s just the truth. People don’t like to accept it, but you know. And I’m at the age already, of being over 60, where I’m one of the vulnerable people at this point. But I would say that… this is kind of purgatory we’re living in. We’re not really living our lives. We’re sort of existing until this all goes away. And I think that it’s wrong. (Pt-1).

Alternatively, being older and having life experiences, such as living through wars, was conversely described as helpful in putting things in perspective and making it easier to deal with the lockdown and its implications: “the difference between this and during the war… When I go for a walk, I’m not worried about bombs… So let’s look at it from a positive point of view. Could be better, but it could be a lot worse.” (Pt-8)

Vulnerability: The paradox of social distancing and health

A few participants were frustrated by what they perceived as a paradox between social distancing guidelines and general health recommendations for older adults to stay active.

…not that clear… whether you should go out for a walk or not. So some say, if you’re over 65 you shouldn’t go for a walk out[doors] at all, which is a terrible thing to say, because you need to get out. But if you do social distancing and it’s not that busy around here, I’m not sure why I shouldn’t go for a walk for my health. (Pt-2)

Some expressed concern about the lockdown exacerbating pre-existing age-related changes, for them and other family members. Pt-6 was worried about his 94-year-old father: “he would normally be out and about much more often. And he would be getting his exercise just getting out and walking… And I can see that by being inactive and staying inside, it’s aging him.”

As mentioned previously (see Need for aging-specific guidelines), participants felt that more action should have been taken to help them resolve this paradox, and maintain their overall health and well-being.

I don’t think they were quick enough to alert people to the necessity, not just the masks and the gloves, but to make sure that their nutrition was up to date… That they had proper and useful ideas for how to spend your time in isolation. It’s a whole new dynamic for people… I know how anxiety can, you know, make itself known, when you live alone and you are worried about stuff that’s going on that’s outside of your control. But if there had been as much attention paid to the need to distract yourself, the ability to remind yourself of hobbies you had when you were younger and had the time to do them… things that give people a sense of continuity but also a way of grounding themselves in a situation that is all over the place. (Pt-14)

Discussion

The lockdown resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic provided a unique opportunity to gain insight into how daily life of older adults was affected when occupational disruption and social isolation occurred. This study was conducted with community-dwelling older adults who were participating in various social and leisure opportunities outside their home prior to the lockdown, looking at non-medical implications of the pandemic on older adults, as recommended by O’Sullivan and Bourgoin (Reference O’Sullivan and Bourgoin2010). We presented findings on five interrelated themes that highlight how older adults understood and applied COVID-19 guidelines and the impacts that these had on their daily activities and life as a whole. We found considerable variation among the participants in their response to the occupational disruption and social isolation that they experienced and in the impacts that these had on their lives. The findings provide in-depth descriptions of similarly diverse and complex findings from a rapid review on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults, which reported decreased in-person social interactions and reduction of physical activity, along with increased psychological symptoms and reduced quality of life (Lebrasseur et al., Reference Lebrasseur, Fortin-Bédard, Lettre, Raymond, Bussières and Lapierre2021)

Understanding and Applying COVID-19 Guidelines

The vast majority of participants felt that public health guidelines were clear and adhered closely to these. Their actions suggest that public health guidelines were disseminated effectively through multiple sources of information, such as news outlets, social media, family, and friends. Adherence to the guidelines was predominantly motivated by fear of catching the virus. It is likely that fear of death in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is greater in older adults, as it is widely known that the risk of severe illness and death as a result of COVID-19 infection is significantly higher as people age (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Peng, Xu, Zhao, Liu and Peng2020). Indeed, older age was a significant predictor of adherence to COVID-19 guidelines in the United States (Park et al., Reference Park, Russell, Fendrich, Finkelstein-Fox, Hutchison and Becker2020). In this study, participants took extra steps beyond those recommended, including not leaving their home for up to 3 months. They also avoided activities available to them, such as bicycling, for fear of requiring medical help which would put them at added risk for COVID-19 infection. This may have exacerbated the occupational disruption caused by following public health guidelines.

Daily Activities during Lockdown

All participants experienced and reported disruption in their daily activities and a reduction in the frequency of their activities outside the home, resulting in a lack of daily structure and feelings of boredom and low productivity. In the absence of out-of-home activities during this pandemic, having a daily structure, maintaining social connections, and preserving physical and mental activities have been suggested to support the health and well-being of older adults (Hwang, Rabheru, Peisah, Reichman, & Ikeda, Reference Hwang, Rabheru, Peisah, Reichman and Ikeda2020). This was identified by many of the participants who took actions to perform social and leisure activities virtually and/or find meaningful activities at home.

Many participants found the transition to online activity challenging, recognizing their limited proficiency with technology. In a survey conducted in July 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, 74 per cent of Canadians over the age of 65 reported feeling confident in using current technology, and 80 per cent believed that technology could help them remain connected with others (Age-Well, 2019). A study performed in Europe during the first pandemic wave found that intergenerational and other non-physical social contacts during lockdown decreased the negative effects of the lockdown on depressive symptoms in older adults, but did not eliminate them (Arpino, Pasqualini, Bordone, & Solé-Auró, Reference Arpino, Pasqualini, Bordone and Solé-Auró2021). In a similar vein, the participants felt that technology was helping them to stay connected; however, it did not provide the same quality of social interaction as connecting in person did.

Participants expressed the fatigue experienced in relation to increased online activity, and the reduced pleasure from virtual activities compared with engaging in them in person. Certainly, these responses were not unique to seniors (Reinach Wolf, Reference Reinach Wolf2020). Further, as the participants in the current study were relatively young seniors, their challenges with technology may have been much less than would have been experienced by older seniors. As it is likely that online activity will remain, post-pandemic, at a higher level that was the norm pre-pandemic, community care providers may consider how to enhance the quality of the overall experience of virtual social and leisure activities, and how best to offer seniors training and support in ongoing technical proficiency.

The new or expanded in-home activities were commonly described as time fillers, and as less fulfilling than previous out-of-home activities. The latter was true, for the most part, for social-leisure activities performed virtually. A reduction in social, leisure, and work activities gives rise to concerns about the long-term health effects for seniors, as we now know that a combination of social, intellectual, and physical activity has substantive protective effects on health (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Wray and Lin2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yeh, Lee, Lin, Chen and Hsieh2012; Sharifian et al., Reference Sharifian, Kraal, Zaheed, Sol and Zahodne2020).

The increased in-home activity, virtual or tangible, contributed to an increased amount of time in sedentary activities, with a notable loss of opportunities for physical activity. Given the importance of physical activity for overall health (Rebelo-Marques et al., Reference Rebelo-Marques, De Sousa Lages, Andrade, Ribeiro, Mota-Pinto and Carrilho2018), this is of particular concern in relation to the longer-term health effects of the pandemic. Only a minority of the participants were able to alter their routines and find ways to maintain previous levels of physical activity, so as to avoid the negative long-term health effects of reduced physical activity during the pandemic. Many of the participants had previously participated in community-based physical activities, such as in a gym or community centres, which were shown to be positively related to not only physical health, but also to functional ability, independence, mental health, and social connectedness in older adults (Hambrook, Middleton, Bishop, Crust, & Broom, Reference Hambrook, Middleton, Bishop, Crust and Broom2020). It is not clear if replacing them with solo walks or online classes, as some of the participants had done, will carry similar benefits. Therefore, the need to support older adults’ activity levels is particularly salient. It is likely that some older adults will have experienced a decline in their abilities over the time of social isolation, and may require supports to return to their previous level of activity engagement when social distancing policies are discontinued.

Mood and Affect

Being involved in meaningful occupations provides routine and structure, and enables enjoyment and fulfilment that can alleviate stress, distract from one’s problems, enhance a sense of self-worth, and foster hope (Hammell, Reference Hammell2020). Therefore, it is not surprising that many of the participants expressed some emotional distress. Increased news consumption in the early weeks of the pandemic may have increased stress levels, because participants found the news overwhelming and depressing. Stainback, Hearne, and Trieu (Reference Stainback, Hearne and Trieu2020) suggest that COVID-19 news media consumption may amplify the perceived threats from the virus, and negatively impact mental health and well-being, especially in the early stages of the pandemic, when a solution, such as a vaccine, was not in sight. As these interviews were performed in the early months of the pandemic, we do not know whether participants’ experiences remained similar in the following months of the pandemic and ongoing daily life restrictions.

Importantly, none of the participants in this study described high levels of anxiety or depression, but rather reported using various strategies to maintain their mental health. Research on occupational disruption after relocating to retirement living suggests that having control and preparing well for the move contributed to a positive adjustment (Walker & Mcnamara, Reference Walker and Mcnamara2013). Because of the pandemic circumstances, these participants did not have the privilege of advance planning. They described ways of coping that aligned with emotion-focused coping, which included reframing one’s understanding of the situation as a way to decrease stress (Lazarus, Reference Lazarus1993). Aldwin, Lee, Choun, and Kang (Reference Aldwin, Lee, Choun, Kang, Revenson and Gurung2019) noted that emotion-focused coping strategies are considered to be appropriate for uncontrollable situations. Participants also described using what can be understood as problem-focused coping strategies, including making behavioural changes aimed at reducing negative emotional responses (Aldwin et al., Reference Aldwin, Lee, Choun, Kang, Revenson and Gurung2019). In this study, participants’ problem-focused strategies included the noteworthy transition to online activities, as well as engaging in calming and pleasurable activities at home or outdoors, often with other people. Park et al. (Reference Park, Russell, Fendrich, Finkelstein-Fox, Hutchison and Becker2020) also found that these types of problem-focused strategies were commonly used to cope with COVID-19-related stress. Interestingly, they reported lower stress levels among older adults compared with young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (Park et al., Reference Park, Russell, Fendrich, Finkelstein-Fox, Hutchison and Becker2020). This supports the premise that older adults may use more proactive coping strategies to avoid problems in real world situations than young adults, enabling resilience in aging (Aldwin et al., Reference Aldwin, Lee, Choun, Kang, Revenson and Gurung2019). Our findings provide support for the ability of older adults to benefit from problem- and emotion-focused strategies and suggest that their explicit integration into interventions may support the health and well-being of older adults dealing with stress related to occupational disruption and social isolation.

Aging and Social Context

The participants, who were generally active and independent older adults, reported becoming more aware of their age and the limitations it posed during the pandemic. This heightened awareness may be related to the occupational disruption that they experienced. Previously, the inability of older adults to take part in meaningful activities was found to disrupt their sense of self, lead to thoughts about being old and dying, and compromise their well-being (Mulholland & Jackson, Reference Mulholland and Jackson2018). Another possible explanation is that this awareness increased in response to the ageist attitudes expressed in traditional and social media, the misrepresentation of the COVID-19 pandemic as an “older adult problem”, and the social policies that imposed restrictions on older adults (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Lagacé, Bongué, Ndeye, Guyot and Bechard2020). It is also possible that feeling pressured or forced to accept help from others compromised participants’ sense of independence and autonomy, which are viewed by older adults as key for aging well (Halaweh, Dahlin-Ivanoff, Svantesson, & Willén, Reference Halaweh, Dahlin-Ivanoff, Svantesson and Willén2018). The findings suggest that limitations caused by the pandemic, the protective response taken by family members, and carelessness by others in the community, may all contribute to an experience of “feeling old”, characterized by fear of helplessness and dependence and feeling different from other people (Nilsson, Sarvimäki, & Ekman, Reference Nilsson, Sarvimäki and Ekman2000). Loss of independence and autonomy related to disengagement from former life roles was reported in regards to occupational disruption in the first few weeks after moving to a long-term care facility (O’Neill, Ryan, Tracey, & Laird, Reference O’Neill, Ryan, Tracey and Laird2020), suggesting that understanding occupational disruption is important for the post-pandemic era as well.

Participants identified a paradox between the public health social distancing guidelines and pre-COVID health recommendations to engage in lifestyle behaviours that support health in aging, such as physical exercise, and social-leisure activities (Sabia et al., Reference Sabia, Singh-Manoux, Hagger-Johnson, Cambois, Brunner and Kivimaki2012). They expressed concern that although following COVID-19 guidelines may protect them from the virus, it leaves them susceptible to physical, mental, and/or cognitive decline that may severely affect their lives post-pandemic. This paradox was also identified by Tyrrell and Williams (Reference Tyrrell and Williams2020), who suggested that ageism and age- and health-related biases may be impacting health care policies that put older adults at acute risk of loneliness, depression, and physical decline. Our findings suggest an urgent need for acknowledgement of this paradox, and the development of directives or its management.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that participants were involved in an online group as part of the RCT described in the Methods section. As the intervention was converted to be run online, this activity continued without interruption even when the lockdown was imposed. In addition to the intervention sessions, participants also had the opportunity for contact with research assistants for booking of follow-up sessions and providing information. Therefore, their experiences of occupational disruption and social isolation may have been attenuated relative to their counterparts. The second limitation is the relative homogeneity of the sample. All participants were community-dwelling older adults who were independently mobile in their communities. In addition, the majority were Caucasian and were well educated, many with multiple years of post-secondary education. The experiences of those less well-educated, from visible minorities, and/or with more mobility restrictions could be quite different. Third, the results reported here represent early responses to the occupational disruption caused by the lockdown and cannot be generalized to the experiences people may be having a year into the pandemic.

Conclusions and Implications

Older adults who participated in this study were concerned about the long-term effects of public health guidelines on their physical and mental health. The problem-solving strategies, such as transfer to virtual activities and performance of alternative social-leisure activities at home or outdoors, offer benefit yet do not provide the same level of meaning and pleasure. They experienced the paradox of social distancing (Tyrrell & Williams, Reference Tyrrell and Williams2020), whereby reducing the risk for COVID-19 infection puts their overall health and well-being at increased risk of decline. It is necessary for policy makers, at the provincial and government levels, to take the broad health needs of older adults into account when making future decisions and planning next steps for implementing social distancing guidelines. Unfortunately, we cannot assume that seniors will return to pre-pandemic activities once social distancing restrictions are lifted and therefore, the possible deterioration in physical, mental, and cognitive health precipitated by the lockdown may continue. We suggest that community and health care agencies start planning and implementing ways to support seniors in returning to a pre-pandemic activity level.

Funding statement

A grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (# 366538) supported the parent RCT.