In August 1972, Kenya’s newspapers covered—over several days—an event attended by the Minister for Co-operative Development, Masinde Muliro. The event marked the completion of fifteen maisonettes in Nairobi, built by the Harambee Co-operative Savings and Credit Society (referred to henceforth as Harambee Co-operative). The maisonettes were presented as an achievable route to a respectable professional life for a small urban family: “[t]he maisonettes… are three-bedroomed. There is a study, three bathrooms and toilets, kitchen, laundry and a servant’s quarters…. Members of the society can expect to be allocated houses with reduced rentals.”Footnote 1

The Harambee Co-operative was, at this point, being held up as an outstanding example of collective self-help, conveniently nestled right at the heart of government.Footnote 2 While it was a co-operative (in keeping with the convention of the time, we will hyphenate that word throughout), owned and run by its members, those members were all on the payroll of the Office of the President—including the staff of the provincial administration, which for most Kenyans was more or less synonymous with the state.Footnote 3 Harambee Co-operative’s name itself had multiple resonances: “Harambee” was President Jomo Kenyatta’s preferred rallying cry for his doctrine of self-help; “harambee” was the term used to describe the many meetings across the country at which citizens were urged to offer contributions to public projects; and its office at Harambee House was also the headquarters of the Office of the President.Footnote 4 Muliro’s speech—thoroughly reported in the newspapers—hailed the completion of the maisonettes as a great success for the rapidly growing co-operative savings and credit movement in Kenya, noting that “[i]t was the policy of the Government to assist every mwananchi [citizen] to have a better home.”Footnote 5

As will be explained below, much of the detail in these newspaper stories was untrue. The maisonettes were not destined to be homes for members of the society, and though Harambee Co-operative, founded only two years earlier, was indeed growing rapidly, it was already showing signs of the weaknesses that would lead it to the brink of collapse by the end of 1976. Yet the history of Harambee Co-operative is not simply a story of the bombastic misrepresentation of reality by politicians, officials, and journalists obsessed with development. In exploring the first decade of Harambee Co-operative, we argue that Harambee Co-operative (as opposed to the wider “harambee” movement, which is not the focus of study here) really did enable many of its members—many of whom were at the very bottom of the civil service hierarchy—to pursue an ideal of propertied life. While it served as an engine of inequality, Harambee Co-operative also enabled thousands of employees of the government to invest in their futures. Harambee was the largest savings and credit co-operative of the period, and so we focus on it in this article. But there were many others, as we will explain. This story, we suggest, offers a window on long-standing questions about Kenya’s political economy in the 1970s.

More than forty years ago, Mordecai Tamarkin asked how we should understand what he called Kenya’s “political stability” through the 1960s and 1970s—by which he meant the absence of military coups and the continuity in elected civilian government. Tamarkin pointed to a number of factors: the emergence of a highly personalized presidency; close control over security services and an electoral system that served as an effective channel of both communication and patronage.Footnote 6 Much subsequent literature has echoed aspects of that analysis, emphasising in particular the role of the system of provincial administration—though the framing of the question has shifted away from explaining “stability” and towards a concern with the way that political continuity has existed alongside persistent inequality, centralized authority, and state violence.Footnote 7 Since the 1990s, in the context of the turbulent politics of multi-partyism, focus has been on the way that the Kenyatta years entrenched a clientelist politics that combined a centralized, authoritarian politics with a political mobilisation of ethnicity.Footnote 8 But Tamarkin’s original argument had also pointed to the role of what he called an “African bourgeoisie” with vested interest in the regime. He was vague in his account of that bourgeoisie, calling it an “elite” but also saying that it embraced both “middle and upper class.” Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o similarly argued that an emerging middle class willingly accepted presidential authoritarianism as the price for their pursuit of property ownership.Footnote 9 More recent work has also pointed to the importance of a “statist” regime of land allocation in Kenya.Footnote 10 The redistribution of land formerly held by white settlers was a deeply unequal process, yet it provided the resources for a politics of patronage that underwrote stability, though at the cost of entrenching patterns of political mobilization that foregrounded ethnicity.Footnote 11 In this paper we return to that entanglement of property-owning and politics.

At more or less the same time that Tamarkin was writing, leftist scholars were pursuing a separate, but related, debate which turned on a simple question: had Kenya become home to a “national bourgeoisie”– a group of indigenous capitalists whose interests were not necessarily aligned with those of international capital? Footnote 12 The key focus of this analysis were politically well-connected individuals who had used the tool of the state to secure control of real estate and to elbow their way into significant positions of ownership in some of Kenya’s largest companies, some of which were (formally or not) local agents of international firms.Footnote 13 The significance of that question (beyond the pursuit of a theoretical point about dependency and global capitalism) was that it raised a further issue.Footnote 14 Were Kenya’s elite simply self-interested accumulators, happy to accept subordination in a global economy in return for personal wealth? Or, as a national bourgeoisie with a sense of shared interests, would they break the cycle of dependence which kept Kenya underdeveloped? The evidence here throws tangential light on that, suggesting that senior civil servants could work together to restrain one another’s behaviour and to enable other Kenyans to pursue a property-owning future

The records of the co-operative itself are not available, but the government department that supervised co-operatives (sometimes a single Ministry for Co-operative Development, at other times a department within a wider Ministry for Co-operative Development and Social Welfare) has made many of its files for the period available in the Kenya National Archives. The collection is incomplete but is complemented by a significant amount of newspaper coverage. The resulting paper trail provides, on the one hand, evidence of accumulation by particularly well-connected individuals, showing both how this accumulation was possible and how unequal the process was. Yet the evidence points to a more complex story than simple rent-seeking by senior officials, showing how employees at the lowest level of the state machinery could benefit. That offers a new perspective on why the provincial administration was so robust, going beyond explanations which have emphasised the colonial legacy of authoritarianism and the campaign against Mau Mau.Footnote 15 The evidence from Harambee Co-operative shows that there was a very material aspect to the loyalty of those who worked for the state: through the co-operative, hopeful clerks, drivers, and policemen could see employment as the route to a better future for themselves and their families, a way to acquire and improve land and houses and realize the promise of property-owning citizenship. When weaknesses in the management of Harambee Co-operative threatened to undermine the faith of these lower-ranking government employees in the future, more senior colleagues intervened to save the co-operative and ensure the recruitment of these petty accumulators to an emergent “African bourgeoisie.”

Harambee Co-operative was especially significant because it was large, and because it underpinned the provincial administration. That is why we focus on it here. But it was one of many savings and credit co-operatives in Kenya, as we will also show in this article. Across all departments of government, and many private businesses, these co-operatives enabled waged employees to imagine—and reach—a future in which they were property-owners. Savings and credit co-operatives both complemented and mediated Kenya’s “statist” regime of land allocation. They offered waged workers a distinct route to buying property, intersecting with the ethnic politics of settlement schemes and land-buying companies yet not identical with these. They help us see that there were multiple routes to acquiring a stake in a political economy that was deeply unequal but not entirely exclusive.

“Mobilizing Savings”: Government Policy and Co-Operatives

Kenya’s first savings and credit co-operatives were created in 1964. They drew on two distinct roots. One was the particular kind of producer co-operative that emerged out of colonialism. Such co-operatives had existed in Kenya since the early twentieth century, initially created by European settlers for the purpose of marketing crops and becoming a channel for producer credit to a European farming sector that relied on state support and the expropriation of African land and labour.Footnote 16 In late-colonial Kenya—as elsewhere in Africa—British policy promoted co-operatives for Africans, as part of a strategy of “imperial rescue” in the face of threats to colonial order.Footnote 17

Since the late 1960s, a critical literature on co-operatives in Africa has consequently tended to emphasise their alien nature, and to present them primarily as tools of state intervention and control, which were doomed to failure because they lacked connection with a popular “economy of affection.”Footnote 18 In Kenya, where produce and marketing co-operatives were central to a postindependence vision of development as state-directed, if located in individual enterprise, Kara Moskowitz has described them as “a site of state-building outside the state.”Footnote 19 Certainly, a sense of “administrative paternalism” permeated co-operative policy in Kenya, and postindependence legislation confirmed—and even extended—the very extensive powers of the government over co-operative societies.Footnote 20 Yet, we argue, that this critique risks ignoring the extent to which savings and credit co-operatives, in particular, responded to popular demands and aspirations and mobilised both mutual obligation and individual ambition to become part of everyday life for many Kenyans.

Thrift societies were the other root of savings and credit co-operatives. These had been intermittently promoted by the colonial state from the 1940s as one aspect of a wider, not entirely coherent or consistent, colonial attempt to encourage Africans to “save”—that is, to encourage them to see value in terms of money and to bank that money.Footnote 21 When these thrift societies started to lend money to their members, colonial officials tried to reconcile their deep-rooted concern over African “improvidence” with the emerging belief that development was being held back by a lack of credit. Officials sought to catch up with emerging practice and reassert control through model by-laws supplied by the Registrar of Societies. These defined the aims of thrift societies:

a. to encourage thrift and small savings by providing means whereby such savings may receive a reasonable interest without risk and without being removed from the control of the members; and

b. to afford relief to members in need by enabling them to obtain loans for useful or really necessary purposes at reasonable interest and with easy terms of repayment.Footnote 22

These thrift societies were mostly small and short-lived and were a minor element in colonial policy.Footnote 23 But from 1964, just after independence, a new and more robust model for co-operative saving and borrowing was introduced to Kenya, brought—in ways that were uncoordinated but closely linked—by the Catholic church and by development workers linked to credit unions in North America.Footnote 24 The key innovation was simple but profound: savings became shares. A group of people would form a co-operative. All were shareholders in the co-operative as a mutually-owned institution. Each time they saved, they were buying shares. They could only get their money back by leaving the co-operative and cashing in their shares. But—crucially—they could borrow against their shareholding needing no further collateral. In fact, they could borrow double, or in some cases up to three times, their shareholding, repaying monthly with interest charged on the reducing balance. The savings and credit co-operative allowed people to keep their savings while also borrowing.

In the mid-1960s, a review of co-operatives in Kenya by the Nordic Technical Aid Project recommended that a clear distinction should be established.Footnote 25 Credit for rural farmers should be provided solely through producer cooperatives: since the challenges for farmers were seen as primarily those of credit and marketing, these cooperatives would handle both.Footnote 26 Savings and credit cooperatives, on the other hand, would be reserved for urban workers. As the name implied, savings were to take precedence over credit.Footnote 27

That separation reflected a set of ideas that were powerful in development thinking of the time. The development of smallholder agriculture, it was believed, was held back by lack of access to credit. On the other hand, the development of the national economy as a whole was held back by an overall lack of savings and Kenyans—particularly wage-earning Kenyans employed in the towns—needed to save more: “investment must be preceded by savings,” the governor of the Central Bank sternly announced.Footnote 28 Mwai Kibaki, a junior minister (and later vice-president and then president of Kenya) told a national newspaper: “one of the major problems facing Kenya was to convert the people to thinking in terms of saving.”Footnote 29 Savings and credit co-operatives were repeatedly presented in those terms: a way to “generate local savings for re-loaning and distribution to the country for development and reduce reliance on borrowed capital.”Footnote 30

This was not a peculiarly Kenyan concern. Many economic theorists insisted that “take-off” required a certain level of domestic savings: the “mobilisation of local savings” was seen as a way to avoid excessive reliance on external capital.Footnote 31 This was the theme of pan-African annual conferences throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, funded by the US-based Credit Unions National Association (CUNA), which had won US government support for its work by explicitly presenting credit unions as a tool against communism.Footnote 32 Explaining the lack of capital in Africa as a problem of personal behaviour that could be solved by thrift—rather than as a consequence of systemic global underdevelopment—appealed to other international donors too, notably the Konrad Adenauer Foundation. As other scholars have pointed out, the logic of co-operatives has not always been anti-capitalist.Footnote 33

While not uniquely Kenyan, savings and credit co-operatives proved particularly successful there, being worked into a narrative that tied them to the distinctive, if elusive, Kenyan model of “African socialism.” This combined an emphasis on “mutual social responsibility” with an urgent sense of the need for growth.Footnote 34 Savings and credit co-operatives, civil servants declared, preserved Africa’s “cultural heritage” of “mutual aid”—an argument that was often made at the time.Footnote 35 Concerned that the first savings and credit co-operatives tended to be unstable and “organized on a tribal basis,” the Department for Co-operative Development—with funding from Catholic Relief Services and the CUNA—dispatched field officers to promote the creation of savings and credit co-operatives in workplaces and encouraged employers to allow check-off systems, through which savings (and loan repayments) could be taken directly from wages.Footnote 36 A Kenya National Promotion Committee for the Mobilisation of Local Savings was formed, with membership from across government; the Commissioner for Co-operative Development (CCD) told its members that savings and credit co-operatives were “the instrument and spearhead in the participation of wananchi in economic activities.”Footnote 37 Senior civil servants across multiple ministries and departments, and in private enterprise, were encouraged to promote co-operatives:

As you might be aware, it is the Government Policy to promote formation of Savings and Credit Societies among salary earners both in Government and the Private Sector.… The money thus mutually saved is in turn lent out to deserving members at reasonable terms for specific purposes such as paying of deposit for a house, medical expenses, school fees and a host of others. It is indeed a form of self-help and is dictated and guided by needs of members of the group who have confidence and trust of each other.… I am writing therefore to solicit your good cooperation and assistance to promote Savings and Credit Co-operative Societies.Footnote 38

This campaign by government and donors was followed by a significant growth in the number of savings and credit societies in Kenya: from 80 co-operatives with 21,268 members and 1,170,000/- (Kenya shillings) of savings in 1968, to 161 co-operatives with 35,745 members and 16,200,000/- savings at the end of 1972.Footnote 39

The rhetorical insistence on the cultural embeddedness of the co-operative model was at odds with the reality of government and donor intervention.Footnote 40 Yet the evidence shows that the growth of the savings and credit co-operatives was not simply a top-down process. Groups of workers actively sought help to create savings and credit co-operatives.Footnote 41 There was a powerful pull factor for them, summarised by the popular politician J. M. Kariuki, when he attended the first meeting of a new co-operative in 1969: “the society would help those who could not obtain money from banks.”Footnote 42 For most Kenyans, access to money credit from banks was almost impossible in the 1960s. Kenya’s commercial banks had emerged in the colonial period as institutions primarily interested in financing trade through lending to European or Asian businesses; after independence the major banks continued to operate as a cartel to ensure their profits.Footnote 43 Some—notably Barclays—did seek to “Africanise” business in the wake of independence. Footnote 44 But most potential African customers, including wage-earning civil servants, had little to save and had no collateral to offer in return for credit. While the newspaper adverts for banks featured tempting images of smartly-dressed consumers, few could afford the account fees charged by banks, or maintain the minimum balances that they demanded. An angry letter to a national newspaper in 1969 asked:

May one of the bold bank managers or directors tell wananchi [citizens] whose bank accounts were recently compulsorily closed or who have been prevented from opening bank accounts because they cannot raise the minimum deposit of 500/- the reasons for such unwarranted action?… Is this really nation-building? Instead of encouraging a low-income earner or a peasant to farmer to make a gradual saving in order to make a saving [sic] for his children’s education, a better house and improved living conditions, the banks have put a ceiling to all these…. Are the banks really interested in the welfare of wananchi or is their only interest to make big profits which will only benefit a few individuals—the shareholders?Footnote 45

“It’s a hard job trying to get a mortgage,” lamented one newspaper article.Footnote 46 By contrast, savings and credit cooperatives offered a way not only to save small amounts but—crucially—to borrow significantly more than had been saved.

Government Intervention and Popular Demand: The Creation of Harambee Co-Operative

A savings and credit co-operative for employees of the Office of the President was first suggested in October 1969 by the head of the civil service, Geoffrey K. Kariithi, at a meeting of the Kenya Civil Servants Union. In an apparent riposte to calls from the union’s president for a new negotiating mechanism around wages and terms of employment, Kariithi reportedly “called on the union leadership to shift emphasis from petty fights against the employer to the mobilisation of resources and efforts to uplift the welfare of the workers.”Footnote 47 The message was clear—workers should help themselves, rather than making demands on their employers.

Within a few months, in the early 1970s, senior officials in the Office of the President had registered the Harambee Co-operative Savings and Credit Society.Footnote 48 While the co-operative had a management committee nominally elected by members, this was—initially, at least—very much a top-down process. The Office of the President employed the seven provincial commissioners (PCs) and their immediate subordinates, the forty-seven district commissioners (DCs), who wielded executive power in everyday life across Kenya. These senior staff were not initially imagined as co-operative members. Rather, Harambee Co-operative was created for the provincial administration’s thousands of lower-ranking staff. The administration police—a relatively lowly-paid adjunct force to the regular Kenyan Police —were also paid through the Office of the President. So were all local government staff and—through a quirk of organization—the staff of the Ministry of Labour. All in all, there were something like 18,000 employees, all potential members of the co-operative. The most senior officials set about trying to sign them up.

Co-operatives Department staff across the country were instructed to promote membership: the possibility that President Jomo Kenyatta would formally present the registration certificate to Harambee was mentioned, and they were told that signing up members would mean that “all of us can be proud.”Footnote 49 Perhaps more significantly, letters were sent out by Gideon Opondo, the Chief Personnel Officer in the Office of the President, to all PCs and DCs: “[i]t is understood that you will encourage your staff to join this society,” they were told.Footnote 50 PCs, in turn, demanded reports on membership from their DCs, blurring the boundary between administrative hierarchy and co-operative structure.Footnote 51 It was helpfully pointed out that those joining need not pay any money directly, since their joining fee and their monthly share contributions would all be simply deducted from their salaries: since they were all on a single payroll, this was easily arranged.Footnote 52 More letters from senior civil servants followed.Footnote 53 The response was initially modest. One local district officer (DO, the rank just below the DC) rather cautiously reported “I regret to inform you that most of them are not interested in becoming members of the society.”Footnote 54 While the correspondence does not explicitly reveal this, it seems very likely that some junior staff were more or less bullied into signing up, as a national newspaper hinted: “there are dangers that over-enthusiastic officials might be carried away and force some society members to join the movement against their wish, as has been reported in some districts of Central Province.”Footnote 55

Opondo’s involvement might seem heavy-handed. But it can be seen more sympathetically in the context of his wider concern for lower-ranked civil servants. As president of the Senior Civil Servants Association, he had spoken out in 1970 against an unexpected pay rise for his members. Opondo had argued that the money should rather have been used to improve the pay and conditions of more junior staff and expressed concern that civil servants might become “demoralised”; with other senior civil servants, he then donated money in a failed attempt to create a cheap co-operative shop for government workers.Footnote 56 He himself became the first chairman of Harambee Co-operative, and continued to use his position to expand the co-operative, ordering PCs to tell their DCs “to assist the local co-operative officers” in this.Footnote 57 He kept pressing for a formal presentation of the registration certificate by Kenyatta, evidently hoping that the prospect of this would inspire officials to sign up more members.Footnote 58 When the presentation finally took place, however, it was not a public event—and reportedly required a “donation” of 10,000/- to Kenyatta from the co-operative.Footnote 59

Reluctant as they may initially have been, members began to save—and to borrow. The record, fragmentary though it is, suggests that much of that borrowing was very modest. In Tana River, a marginal district far from Nairobi, eight members applied for loans in November 1971: the mean value of the loans requested was 1,450/-, with the smallest amount sought being 700/-. For context, the average annual salary for a Kenyan public sector worker at the time was 6,400/- a year, while senior staff were earning 34,000/- or more. These loans would have been significant for junior staff, but not for their seniors.Footnote 60 Yet modest borrowing could allow these low-ranking civil servants to become property-owners: that 700/- was borrowed by a member who wanted to buy a plot of land in his home area (in central Kenya).Footnote 61

By mid-1972, bottom-up enthusiasm was replacing top-down encouragement. More than 300 new members were joining Harambee Co-operative nationally each month, and the co-operative had about 6,000 members.Footnote 62 Having been invited to imagine themselves as land- and house-owners, Kenya’s civil servants took up the possibility with enthusiasm. As the honorary secretary of Harambee Co-operative proudly reported:

I have to confirm that the most frequent loans demanded and have been granted are for the following purposes.

1. For buying land

2. For building houses in the land

3. For school fees and lastly

4. For personal use i.e. medical expenses, buying furniture

I should stress that this society has helped its members to purchase land and build houses more than anything else. School fees comes [sic] occasionally.Footnote 63

Harambee Co-operative’s perceived success was reflected in the treatment of its officials. Opondo, as chairman, was appointed to the national committee for the mobilisation of savings, where he was a vocal and opinionated presence. He was also sent to international conferences—where he evidently saw himself as speaking for Kenya—and on a study tour to the US.Footnote 64

Thwarted Self-Improvers: Discontent and Protest

Harambee Co-operative’s management committee found themselves struggling to keep up with the growth in membership, as loan applications from all over Kenya arrived at Harambee House, where the co-operative was given office space. With advice from an expatriate expert attached to the Department of Co-operatives, the committee invented a branch system, which allowed members to elect officials at a local level to scrutinise loan applications.Footnote 65 The composition of these branch committees confirms the impression that—outside Nairobi, at least—Harambee’s members were low-ranking: clerical officers, typists, and interpreters.Footnote 66 Yet there was some confusion over the exact nature of branches. Should there be one for each of Kenya’s administrative districts? What exactly were their responsibilities in terms of record keeping?Footnote 67 Officials from the Department of Co-operatives—who were supposed to oversee all savings and credit cooperatives—became concerned that Harambee was not keeping proper records or using its funds properly.Footnote 68 But Harambee Co-operative’s officials dismissed both criticism and offers of support in the imperious manner that characterized the provincial administration generally—they were not willing to be challenged by civil servants whom they saw as their juniors.Footnote 69

As Harambee grew, it began to attract higher-ranking staff. Such staff had other ways of borrowing money: from commercial banks or from the government itself, which provided car loans and a generous salary advance system.Footnote 70 But, as the chair of Harambee Co-operative explained, some had larger ambitions: “the society was able to lend money even to senior officers for the purchase of land, payment of legal fees, architects’ fees and further, for payment of mortgage deposits.”Footnote 71

This expansion in membership began to exacerbate a liquidity problem at Harambee Co-operative. People could borrow more than they had saved, but if everyone did this at the same time, the co-operative would run out of money to lend. This was a common challenge for savings and credit co-operatives. It could be fatal. If a co-operative could no longer give loans, members stopped paying monthly contributions (since most were saving in order to borrow), no new members would join, and some who owed money stopped repaying their debts. This led rapidly to what Department of Co-operative officials glumly called “dormancy”—a co-operative could simply become inactive.Footnote 72 In the early 1970s, around a third of registered savings and credit co-operatives in Kenya had become dormant.Footnote 73

In Harambee Co-operative’s case, the liquidity problem was compounded partly by excessive lending to some members, and a failure to recover money loaned out (even though the automatic deduction from payroll should have made recovery simple). In 1973, a meeting of Harambee’s management committee noted with concern that “many members from payrolls appear to have more than two loans… it was evidenced that loans are not being kept properly…. A number of loans had been given to members but no recoveries are being made.”Footnote 74

Even as these problems emerged, however, senior officials began to hatch more ambitious plans. From the late 1950s, some of the large farms given to white farmers in the colonial period had been sold to groups who then sub-divided them. Co-operatives had been one mechanism for this process and some saw opportunities for more such purchases.Footnote 75 Housing projects financed by commercial lenders—which sold individual houses on to buyers on a mortgage basis—also provided a model which some co-operatives sought to emulate: if a co-operative had enough capital, surely it could buy land, build houses, and sell them to members? As it grew, Harambee Co-operative became involved in several projects that went well beyond the initial aim of gathering money and lending to members. These offered another route to property-ownership, but their scale worsened the liquidity problem facing Harambee Co-operative.

The maisonettes opened with such fanfare in 1972 exemplified this problem, and revealed how poor management could exacerbate the consequences of overambition. Harambee’s management committee had initially planned to sell these maisonettes to members, with the purchasers borrowing the money from Harambee itself and paying back over time.Footnote 76 The details are not entirely clear, but it seems that some of the possible purchasers, who would be paying 1,200/- each month on their loans, intended to rent the houses out rather than live in them. Buyers were expected to make a down-payment of 15,000/-, and the chairman of Harambee admitted that the scheme was not for lower earners (average earnings for public sector employees were 6,940/- per annum in 1972).Footnote 77 The Commissioner for Co-operatives evidently suspected a plan to use members’ contributions to enable the wealthiest members of the co-operative to become rental landlords. He barred this, noting that “there are financial institutions in the country which cater for the financial needs of investors.”Footnote 78

Yet by this time the buildings were already well advanced. So Harambee Co-operative was given permission to use its members’ money and a loan from the Co-operative Bank to buy the houses and rent them to its members. When the Co-operative Bank proved unwilling to lend all the money, the property developer lent Harambee the balance of the purchase price.Footnote 79 Once completed, the houses were rented out not to Harambee members, but to an inter-governmental organisation, at a rent which did not cover the costs of the loan taken on to build them in the first place. Several years later, the houses were still not covering their costs.Footnote 80

Other projects followed. Harambee Co-operative’s officials announced a plan to buy an office block, which they would use and rent to others; the Assistant CCD refused to approve the plan, arguing that funds should rather be used for loans to members and warning of “members’ dissatisfaction.”Footnote 81 The co-operative did, however, get drawn into the development of housing estates around Nairobi, offering members loans to buy into these.Footnote 82

Harambee Co-operative continued to draw in new members. The partial records in the archive include a list of 173 members from Kitui District (a district which was neither very marginal nor very central in Kenya) in 1976. The list shows that most members were still relatively low-ranked members of the civil service.Footnote 83 The largest single group were members of the administration police (see definition above); the next largest groups were clerical officers and secretaries; after that came chiefs and assistant chiefs who—despite their titles—were not customary figures but rather local administrators. Their membership numbers suggest that they joined in clusters—several administration policemen joining all at the same time; then a group of assistant chiefs; then clerks. This pattern likely reflected the requirement for guarantors. Any loan application had to be “guaranteed” by two other members, who in theory agreed to repay the loan if the borrower defaulted (though in practice this very rarely happened). Anyone joining the co-operative was likely to encourage their immediate workmates to join too, so that they could guarantee one another’s loans.Footnote 84

Most of the members on the Kitui list were modest savers (see Table 1, above). One-third were saving (that is, buying shares to the value of) twenty shillings a month, the minimum possible; only eighteen were saving over a hundred shillings a month, and none saved more than two hundred. Even if they had wanted to buy houses in Nairobi, none of these members could have done so through the housing projects Harambee was promoting at the time, which would have required them to save “at least 5,000/-” in fifteen months so that they could borrow the required deposit.Footnote 85 Yet these small savers could become property owners on a more modest scale, after years of patience. The clerk who saved forty shillings each month and then borrowed 5,000/- to buy three acres of land in a settlement scheme at the coast must have waited three years to build up the share-holding needed for the loan.Footnote 86 To see these small savers as an “elite” would stretch the meaning of that term—but they were able to leverage their role as employees of government into a new status as property owners.

Table 1. Membership of Harambee, Kitui Branch

Source: KNA MV 1/9, list attached with Chairman Kitui Branch to Hon. Secretary, Harambee, 21 July 1976.

By 1975, however, Harambee Co-operative was the subject of a growing stream of complaints. Frustrated members who had submitted loan applications but received no response began writing to the management committee; many seem to have travelled to the co-operative’s headquarters in Nairobi to complain in person.Footnote 87 Unsurprisingly, given their familiarity with bureaucratic forms, many of these complainants copied their letters to the Commissioner for Co-operative Development (CCD), and/or to the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Co-operatives and Social Services (as it had become by this time). Some wrote to the national press.Footnote 88 They complained that loans were delayed or denied; they alleged that “90% of the loans granted go to Nairobi members” and that the officials of Harambee were using loans to reward “their followers”; they denounced the “expensive projects” pursued by the committee and claimed that “it seems as if the society was formed to benefit a few individuals only” and that “certain individuals, because of their position, have secured enormous loans thereby depriving low earners the opportunity of getting loans.”Footnote 89

These allegations of clientelism were combined with moral stories, which cast the authors as self-improvers thwarted by the abuse of office. A clerical officer who was saving forty shillings each month (likely around 10 percent of his gross salary), explained that the delay in releasing his loan would imperil his claim to land on which he had already made a down-payment and started to build a house: “I shall definitely forfeit the materials I had spent on the house and the money I had paid as well…. Sir, you will find that I am in a precarious predicament and to spare me such an embarrassment I implore you to release my cheque.”Footnote 90

Letters from other complainants constantly emphasised the worthy nature of proposed borrowing: “for the purpose of building”; “to pay school fees”; “to solve a land case and also to pay school fees.”Footnote 91 Most of these members were seeking to borrow small amounts: the mean of the loans requested by forty-nine unhappy members from Nyeri was 4,261/- Kenya shillings, with only one of them asking for the maximum possible loan of 30,000/-. Twenty-six applicants from Kitui applied for an average of only 1,430/-.Footnote 92 Branch officials around the country became advocates for the aggrieved. While these officials were low-ranking clerks, they lent weight to their complaints by using addresses—and forms of signature—that emphasised their role in the administration. One complainant declared their address as “D[istrict] O[fficer]’s Office, Malindi,” with an enthusiastic marginal note of support from the branch secretary; the secretary of another branch, routinely signed his letters to the co-operative “f [or] DC Kitui,” though he was only a junior clerical officer.Footnote 93 These officials used the government internal mail system—for which no postage payment was required—to circulate their complaints to one another, as well as copying them to the CCD; some took to quoting each other’s letters in their complaints.Footnote 94

Some loans were still reaching relatively lowly-paid staff: the eleven Harambee members in Kitui district who did receive loans in September 1975 asked for, and received, an average of 2,236/- each, with none receiving more than 3,600/-.Footnote 95 But by 1976, some local officials were writing to Harambee Co-operative’s office (with copies to the CCD) giving “final notice” that their members had decided on a mass resignation because the funds were being “misappropriated by officials.”Footnote 96

Changes in the leadership of Harambee Co-operative may have exacerbated the problems. The first chairman had resigned, perhaps out of frustration—an official from the Department of Co-operatives suggested that “nobody from the committees [sic] care about the society apart from the chairman.”Footnote 97 The process of electing his successor was criticised by some senior officials.Footnote 98 More projects went awry: Harambee members were given the opportunity to apply for loans which would be used to buy land in western Kenya, but the land seems not to have been purchased, leaving those who had borrowed with a debt but no land.Footnote 99 Meanwhile, more ambitious projects were proposed: restaurants, lodging houses, tractor rental, and more.Footnote 100

Concern about Harambee Co-operative was increasingly evident in the correspondence of the Department for Co-operative Development. Joshua Muthama, the CCD, wrote to the new chairman of Harambee, warning him that “there is more demand for loans than deposits and therefore priority for funds must be given to loans to your members” and pointing out that some of his proposals were “outside the scope of your by-laws.”Footnote 101 He, and other officials, began writing anxious minutes on complainants’ letters and demanding action: the PC of Eastern Province red-penned “something should be done urgently” in the margin of one.Footnote 102 More complaints kept finding their way to senior officials, including the allegation that members of the co-operative board were approving loans to themselves.Footnote 103

Increasingly critical public comments were made by civil servants. In 1975, Kariithi, who had originally suggested the creation of Harambee Co-operative, used a speech at the annual delegates’ conference of Harambee Co-operative to warn its officials against “favouritism” and “any action that might be construed as injust [sic] or unfair”; at the same event, staff from the Department of Co-operatives told Harambee officials “not to invest in large projects at the expense of members” and that “they should aim to satisfy the small man.”Footnote 104 A few weeks later, Muthama, the CCD, made a very public threat to “expose” co-operative officials who gave themselves the “‘lion’s share’” of loans. He sent out a circular to all savings and credit co-operatives, noting that “in a very few societies… office bearers had been unusually generous in granting themselves loans” and set out new rules for lending.Footnote 105

“An Improved System of Management”: Government Intervention

In December 1976 Muthama dismissed all of Harambee’s officials and appointed a new management committee consisting almost entirely of senior civil servants serving ex officio—headed by Joseph Gethenji, the Director of Personnel Management in the Office of the President, one of those who had expressed concern over the election of the previous committee.Footnote 106 “[T]he committee of the said society is not performing its duties properly” read the official notice of the decision. Having offered a glimpse of property-owning progress to employees of government, the co-operative’s failings now threatened to cause disaffection amongst employees of the government.

Harambee’s new chairman issued a circular setting out rules for loans. This restated some rules already nominally in place but also set new requirements: that emergency loans (in cases of illness or bereavement) should be evidenced and that applications for money to buy land or houses should be supported by a letter from the chief or district officer.Footnote 107 The implication of the letter was that members were abusing the system to borrow for other purposes; some branches wrote back querying this and repeating the allegation that “a lion’s share of loans went to Nairobi members.”Footnote 108 Meanwhile, Harambee Co-operative’s auditors identified a different cause for Harambee’s problems, reporting that “[n]o proper bookkeeping and accounting has been done for the society since its inception.” Gethenji brought in a consultancy organization called Technoserve, which had been active in Kenya for several years with funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID).Footnote 109 For the next two years, Technoserve provided a manager and accounting support—which Harambee paid for, though the cost seems to have been effectively subsidised by the USAID grant.Footnote 110 The Technoserve manager spent months fielding a constant stream of angry letters from members whose dreams of property-owning had been frustrated.Footnote 111 But by the beginning of 1979, the flow of complaints had largely—though not entirely—ceased and loans were being issued without delay. Gethenji proudly announced that “future stability” was assured by the “improved system of management.”Footnote 112

At a cocktail party held early in 1979 to mark the end of Technoserve’s work, Gethenji reeled off a list of figures to illustrate the turnaround. In the last two years, he said

the society’s membership had increased from 11,791 to 16,081, the share capital from 19,355,761/- to 34,026,649/- and turnover from 1,953,529/- to 3,567,508/-… the society had now given Sh[illing] 29 m loans to members compared with Sh 19.9 m loans given by December 31st 1976.Footnote 113

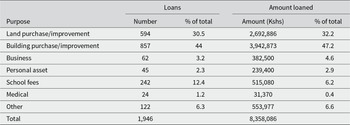

Technoserve also kept a record of how loans were used—or at least, the declared intention for use—in the period of their management (see Table 2, below). It was a record that confirms the idea of Harambee Co-operative as an engine of embourgeoisement: Kenya’s government employees borrowed to invest in property. They bought land, built houses, and improved farmland. A few members were borrowing substantial amounts (35,000/- to pay a deposit on a housing project house, for example)—but the mean loan amount was only 4,295/-. Harambee’s members were mostly borrowing relatively small amounts to pursue modest property investments.Footnote 114

Table 2. Declared purpose of loans from Harambee, January–June 1978

Source: KNA TNA 8/1229, “Loans analysis,” Harambee Co-operative Savings and Credit Society.

While loans were now being issued more swiftly, inequalities persisted. The management committee noted reports that some junior members of staff were being forced to act as guarantors for loans taken by their seniors—but seem to have been unable to prevent this.Footnote 115 Some of those who had lost money in the West Kenya Farm project continued to complain: “certain more influential and powerful people whose money were [sic] also taken… have got back their money. We are really finding it bitter that we are being deducted for the money we did not make use of.”Footnote 116

More widely, while some of those who had borrowed very large sums from Harambee were forced to repay through salary deductions, the collection of other large outstanding loans stalled because no one was willing to take debtors who were also senior civil servants to court.Footnote 117 Some large loans which broke the new lending rules were still approved, with the special sign-off of the CCD.Footnote 118 The clamour by Harambee Co-operative’s members had been effective in restarting the flow of loans to lower-paid members, but some senior members still seem to have enjoyed favourable treatment.

In 1979, Harambee’s members were given the right to elect their own officials again. Even as the co-operative was emerging from its crisis, its officials were launching new investment schemes: including the purchase of godowns (warehouses) in Mombasa which seem to have been bought for above the market price and which immediately required repairs.Footnote 119 Other problems continued. It was reported that, while the deduction of loan repayments had been computerised, the records were being tampered with in some cases so that repayment was not being taken.Footnote 120 Meanwhile, though the average loan was still less than 5,000/-, Harambee asked for—and received—permission to start making loans of up to 70,000/-, to help the better paid acquire urban property in Nairobi.Footnote 121 Within a few years, Harambee was in difficulties again, partly because of ambitious investment projects, a cycle that was to be repeated in the 1990s.Footnote 122

Yet the co-operative continued to grow. By the end of 1987, Harambee had more than 83,000 members (more than 6 percent of Kenya’s total waged work force), and in 1987 alone it reportedly lent 334 million shillings to members—that was almost half as much credit as all Kenya’s commercial banks together provided to all private households in Kenya in that year.Footnote 123 Harambee was chronically beset with crises—but it was also an extraordinary success.

Harambee Co-operative was unusually large and influential because of its link to the provincial administration. By helping tens of thousands of its employees to become property owners, the co-operative gave these people—chiefs, police, clerks, typists, drivers—a stake in Kenya’s future. That helps us to understand how robust and stable Kenya’s administration was in the 1970s. But our argument goes further than that. Harambee was by no means the only savings and credit co-operative in Kenya. What observers called the “explosive” growth of these co-operatives enabled accumulation by wage employees across the public sector, as well as some in the private sector (see Table 3, above).Footnote 124

Table 3. Number, membership, and assets and savings and credit co-operatives

Source: Annual reports of the Department of Co-operatives and Dublin and Dublin, Credit Unions.

The lending figures are particularly striking. Savings and credit co-operatives were insignificant in 1970. By 1977 they were providing a quarter of all household lending in Kenya (see Table 4, above). By the late 1970s, Kenya stood out in Africa because of the size and reach of its savings and credit co-operatives. Elsewhere on the continent, the weakness of the commercial banking system made it hard for relatively low-paid civil servants and other wage earners to accumulate property. In Kenya, Harambee Co-operative and other co-operatives were making it possible for wage earners to borrow and invest.

Table 4. Household lending by commercial banks and savings and credit co-operatives

Source: Kenya, Economic Survey, various years; Department of Co-operatives annual reports; Dublin and Dublin, Credit Unions.

Figures are not consistently available after 1977, but by 1985, Kenya’s savings and credit co-operatives reportedly had more than 700,000 members—which meant that rather more than half of all waged employees in Kenya belonged to one.Footnote 125 Like Harambee Co-operative, some of those other co-operatives faced problems of mismanagement and abuse of office, which left a trail of plaintive letters from members, admonitory notes from the Department of Co-operatives, and dramatic headlines.Footnote 126 Yet also like Harambee Co-operative, they helped many of their members to imagine—and reach—a property-owning future.

Conclusion

Two lessons may be drawn from the story of Harambee Co-operative’s rise and crisis from 1970 to 1979: lessons which might seem contradictory on the surface but are compatible with a nuanced reading of capitalism. On the one hand, this was a story of the abuse of power and inequality. Harambee Co-operative was—sometimes—a machine that collected savings from the relatively low-paid workers and used them to fund borrowing by wealthier, or better-connected, higher-ranking officials who accumulated property as a result. This is a pattern that was enabled by the centralization of power that has been emphasised by scholarship on Kenya since the work of Tamarkin and Cherry Gertzel.

Yet there is also another lesson here. Harambee Co-operative also enabled relatively low-paid government employees to borrow and invest for themselves, offering a route to the accumulation of property that could intersect with, but was separate from, the patterns of ethnic patronage and clientelism that have been seen as the defining feature of land acquisition in Kenya. Moreover, when Harambee Co-operative ran into difficulties, senior civil servants intervened to improve its management—and ensured that lower-ranking government employees could continue to borrow money and buy property. Without Harambee Co-operative and other co-operatives, this path to property ownership would have been simply impossible. As Joseph Oluoch, the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Co-operatives, proudly commented in 1977, through the savings and credit co-operatives “wananchi are able to build better homes, buy land, meet expenses such as school fees, medical bills and so on.”Footnote 127 By insisting on the right of all Harambee Co-operative’s members to borrow, senior civil servants took seriously the claims of chiefs and clerks as citizens committed to self-help, seeking a route to a prosperous future.

In 1987, Harambee’s officials sponsored a newspaper feature claiming, “Today even the lowest paid of our members own property by way of land or house, they have managed to develop their farms and most of them will retire not only with good houses but with well-developed farms.”Footnote 128 That boast hid a story of loss and disappointment for some. But at least some of Kenya’s elite saw the possibility of Kenya as a society of land- and house-owners and they tried—with some success—to recruit their juniors to that society.

Observing Kenya’s savings and credit co-operatives in the late 1970s, the veteran credit union experts Jack and Selma Dublin saw many problems: excessive government interference, mismanagement, insufficient commitment and skills among members of co-operative officials. Yet they also saw the political possibilities of the movement:

The Kenyan elite with their commitment to a trickle-down economic system may be buying time for their tenuous control of their nation’s destiny by giving hope and stability to a rising middle class—the wage earners of government, commerce and industry—who themselves have a vision of someday entering the magic circle of wealth, privilege and prestige. It is this “secondary elite” who hold the key to the future of Kenya’s savings and credit societies…. The availability of savings and credit societies will play no small part in their upward mobilityFootnote 129

They were surely right. Through Harambee Co-operative and other co-operatives, Kenya’s wage earners—including those who did the everyday work of government—could see themselves as citizens, saving, borrowing, and building their way towards an unequal, but property-owning, future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the British Academy (grant SRG2223\231509), the British Institute in Eastern Africa, the Kenya National Archives and Financial Sector Deepening (Kenya) for their help with the research for this paper. Thanks also to Christian Velasco and other colleagues at CIDE, Mexico City, for their comments on an earlier version of this paper, and to the anonymous reviewers at the JAH.