Impact statement

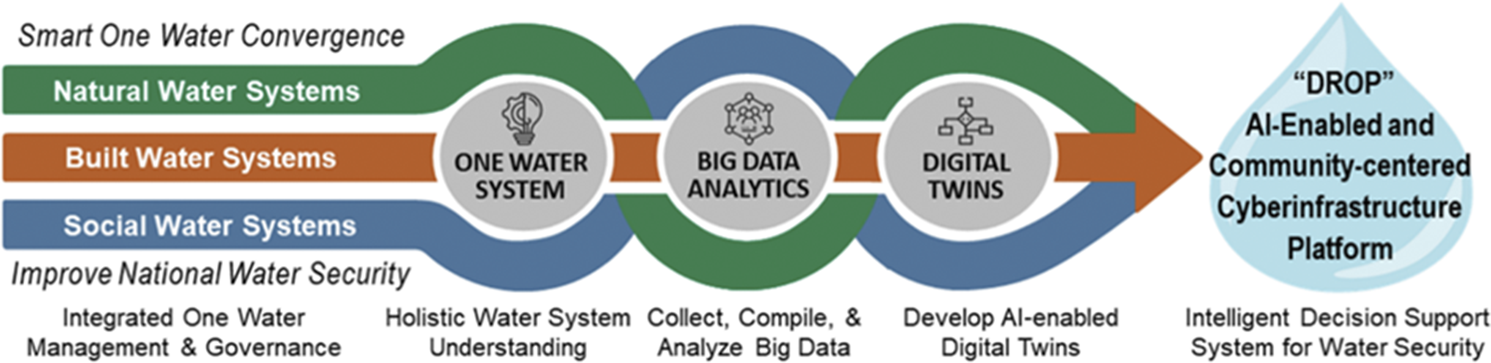

Access to clean and reliable water is critically important for health, well-being and economic development. The natural, built and social systems are linked and form the water system-of-systems. These systems are threatened by intensifying hazards and stressors, including aging infrastructure, floods, droughts, storms, wildfires, sea level rise, population growth, cyber threats and pollution. Rural communities and Tribal nations with insufficient access to clean water or regenerative water sources are often the most impacted. Fragmented and uncoordinated governance and management hamper responses to these issues. The Sustainable Water Infrastructure Management (SWIM) 2024 conference and workshop were organized to focus on the critical importance of water in communities’ ability to function and thrive. The event focused on issues of water scarcity, flooding and water quality, and on powerful innovations and approaches to address these challenges. It explored how communities could create and manage more resilient water availability with wider and more evenly distributed societal accessibility. The SWIM conference generated excitement and passion about water as an essential resource. Attendees were enthusiastic about educating, inspiring and empowering others to get involved, which motivated this call-to-action paper. Major efforts are now required to detail specific solutions (including approaches, methods and technologies) and to define pathways for implementation. Participants offered several initial recommendations for a Smart One Water (S1W) approach. The primary recommendation proposed an integrative, source-to-tap, digital framework that considers natural water sources, engineered water infrastructure and social behaviors to support comprehensive decision-making aimed at increasing water accessibility and the long-term sustainability and resilience of water systems. The approach to operationalizing S1W is captured in the graphical abstract.

Introduction and background

Purpose

This paper summarizes the findings from an effort that convened water sector stakeholders and experts – in the second year of a 3-year conference sequence – to identify solutions and approaches needed to address previously identified issues and challenges in water management. The findings of this paper will be used to further detail and inform how potential solutions and approaches can be successfully implemented (i.e., digital/or social and/or physical) in diverse communities across the United States. The conference series was organized by the Sustainable Water Infrastructure Management (SWIM) Center, a collaborative network based at Virginia Tech, which brings together professional and institutional members from the Water Sector, and has compiled and structured data and knowledge from over 300 water utilities.

The vision and findings of the 3-year SWIM conference series (i.e., the SWIM Trilogy) are also being influenced through the parallel development and implementation of an artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled digital platform for water accounting and tracking from source to tap, which allows consideration of water governance and management (in)efficiencies across and within the water System of Systems (SoS). This platform and initiative are being led by researchers in the SWIM center and in the US Geological Survey, with assistance and support from Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), the States of Georgia, California, and Texas, and many individual public and private utilities.

In brief, the SWIM Trilogy and this paper seek to address the following gaps in water systems practice (and literature):

-

• A relative lack of holistic integration of water governance, management and operations from “source to tap.”

-

• A paucity of “source to tap” data and knowledge compilation, AI-enabled processing and interpretation, and use for efficient, accountable, resilient delivery of water services across a diversity of contexts, communities and hydrologic and political boundaries.

-

• A dearth of education and workforce development tools and training for the next generation of water professionals – data-driven, systems-thinking, AI-knowledgeable and facilitating.

Motivation for our work

The availability of clean, abundant water is essential for human life and economic enterprise. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) state (in target 6.1) the need to “achieve [by 2030] universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all” (Mueller and Gasteyer, Reference Mueller and Gasteyer2021; UN SDG, 2025; UN SDG-6, 2025). Delivering on this target is a major challenge, given the clean water delivery problems caused by aging infrastructure, land-use changes, environmental pollution and natural hazards (e.g., floods and droughts). These stresses are increasing across many parts of the planet. They affect both built and natural water systems (NWS) – built water infrastructure and natural water reservoirs (e.g., groundwater and streams). They also have major consequences for how communities and water professionals react and plan for the future (WHO, n.d.; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mahat and Ramirez2019; Mueller and Gasteyer, Reference Mueller and Gasteyer2021; UN-Water, 2021–2025; NSF-ERVA, 2023).

Availability of water

Availability of water is essential for economic growth and development, and especially so in poor or economically vulnerable communities, including in rural and Tribal communities, as well as in developing countries (Stockholm International Water Institute, 2005; NIAC, 2020; Zhang and Christian-Borja-Vega, Reference Zhang and Christian-Borja-Vega2024). Water allows irrigation and food production and energy generation, both directly (e.g., hydropower) or indirectly (e.g., cooling of power plants), which are all associated with economic growth and well-being (Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Pinilla and Serrano2014). Availability of clean water for drinking, sanitation and hygiene is also essential for health and for preventing the costs associated with disease (Hutton and Chase, Reference Hutton, Chase, Mock, Nugent and Kobusingye2017). Water is also essential to support the digital economy, particularly through its rapidly accelerating use to support AI (Pinheiro Privette, Reference Pinheiro Privette2024), including generative AI (Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Donti, Cuff, Sroka, Ilic, Sze, Delimitrou and Olivetti2024). Lastly, because of ever-increasing uses for water, water scarcity is projected to increase across the planet, thereby posing a threat to economic development (Distefano and Kelly, Reference Distefano and Kelly2017).

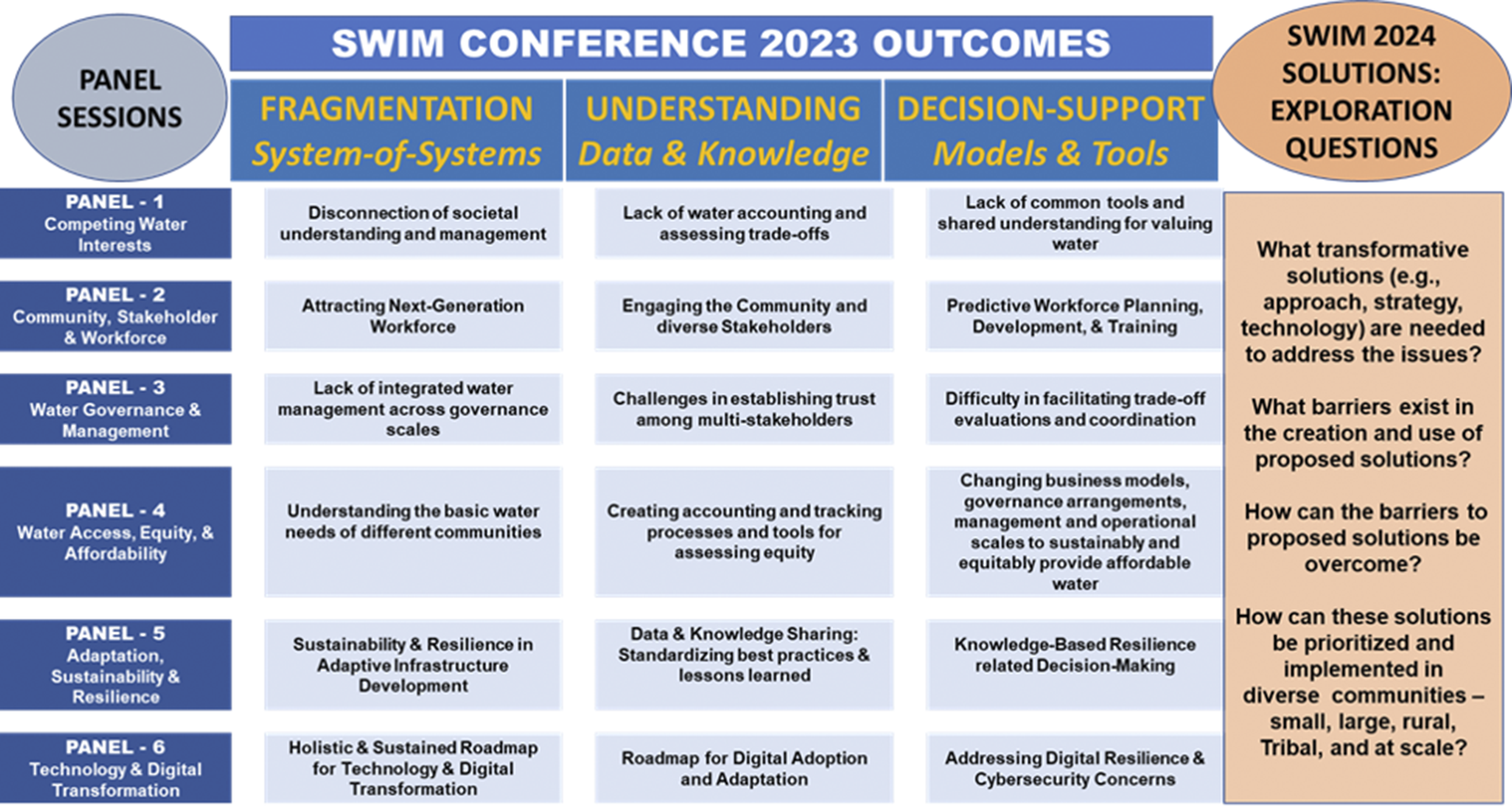

The three major challenges targeted for novel solutions and approaches

Focusing initially on public water supply systems (drinking water, storm water and wastewater), the SWIM 2023 conference identified three major issues that needed to be addressed: (1) fragmentation of water knowledge, governance and management; (2) water system inefficiencies; and (3) stagnation in capacity building and workforce development (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a). These three foundational issues were found to have great variability in relative intensity across different communities in the United States, while nonetheless being susceptible to great improvements through digital tools and technology.

Water fragmentation, disparate accounting and inefficiencies

Fragmentation of knowledge and creation of water management siloes has long been recognized as a problem, one resulting from legacy practices in the water sector and aided by an increasing trend for employment specialization in industry and urban areas (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Babbar-Sebens, Dzombak, Gardoni, Watford, Scales, Grigg, Westerhof, Thompson, Meeker and Shugart2023a). Water professionals have sought to address this issue and provide different frameworks for more integrated water management. Drinking, waste, storm, industrial, agricultural and environmental water, as well as water for energy, are all managed differently, even though they all depend on the natural water cycle (FAO, 2012). Stakeholders of water in the natural, built and social environments have begun to call for more coordination and less siloed water management and governance (FAO, 2016). The shift advocated by many is called One Water (FAO and WWC, 2018), Integrated Water (Pokhrel et al., Reference Pokhrel, Shrestha, Hewage and Sadiq2022), Our Water (Hager et al., Reference Hager, Haroon, Mian, Kasun and Rehan2021) or Total Water (Mukheibir et al., Reference Mukheibir, Howe and Gallet2014), and is driven by the need to improve the management of water systems, to reduce their vulnerabilities and to improve understanding of water system interdependencies. Hydrologists studying watersheds, river systems and groundwater and focused on modeling and assessing “natural water systems” (NWS), developed the concept of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). In contrast, water professionals working in urban areas, who are usually focused on the delivery of water services and the management of storm water and wastewater, developed the One Water integrating framework (US Water Alliance, 2016; Water Research Foundation, 2017a,b; Howe, Reference Howe2019; USEPA Office of Water, 2025). Built water systems (BWS) and infrastructure are at the foundation of the One Water concept. Nonetheless, the One Water concept increasingly considers NWS provisioning, preservation and condition needs. For example, strategies are increasingly being used, including in urban areas, and infrastructure built to capture stormwater for water reuse and conservation (e.g., see Vigneswaran et al., Reference Vigneswaran, Kandasamy and Ratnaweera2025) and to use treated wastewater for managed aquifer recharge (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu and Kanyerere2020). The One Water concept also brought in the need to account for the intricacies of the Social Water System (SWS) – the system describing the socioeconomic utilities of water supply services, as well as the social behaviors, value systems and financing mechanisms needed for effective, sustainable and resilient provisioning of water services. In summary, the One Water concept ultimately seeks to integrate three water systems (NWS, BWS and SWS) into a single natural, built, social water (NBSW) SoS (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a).

Fragmentation of water governance is also a major problem that is increasingly recognized, especially as water is transferred from provisioning basins and watersheds to areas with growing populations or socio-economically important enterprises (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a). Perhaps because water is so important, its operations and governance have tended to grow from the ground up, from local needs and contexts to sometimes broader regional needs. And even at the level of States or Regions, agencies with responsibilities for water management or governance tend to be focused on the policy or regulatory drivers responsible for their existence. Ecological conservation and needs are commonly institutionally divorced from the administration of water rights and allocation permitting, which are themselves divorced from water pollution management and from the utilities providing water services, as well as from the authorities ensuring the needed transfers and efficient storage of water supplies. Topping this off are often inconsistent and antiquated systems of water laws that generally fail to be cognizant of modern scientific knowledge, such as, the interconnections between groundwater and surface water systems (McNutt, Reference McNutt2014). While many Federal agencies have responsibilities for water in the United States, there is similarly no national program or entity that envisions, provides information and helps coordinate integrated governance and management of NWSs with built and socio-economic water systems (NIAC, 2023a,b) – while taking into account local to regional contexts. Having such a national program or entity could potentially benefit not only local and State water management but also help in the establishment, maintenance or revisions of interstate compacts and/or in the adjudication of in-basin or transbasin water issues.

Fragmentation of knowledge, governance and management translates into a disparate set of water accounting frameworks. Water professionals focused on NWS and IWRM tend to use the Water Accounting Plus approach (Karimi et al., Reference Karimi, Bastiaanssen and Molden2013; Amdar et al., Reference Amdar, Mul, Al-Bakri, Uhlenbrook, Rutten and Jewitt2024). Professionals interested in the connections between water and the economics of Nations, as might be described by integration with the System of National Accounts used in OECD countries, use accounts based on assessing the supply, demand and values of natural capital (Vardon et al., Reference Vardon2023; Reference Vardon2025). Meanwhile, corporate entities dependent on water or providing water services have their own tools for decision-making, based, for example, on corporate water accounting (Christ and Burritt, Reference Christ and Burritt2017) and/or on risk management (Meurer and Michael Van Bellen, Reference Meurer and Michael Van Bellen2024; Peng et al., Reference Peng2025). In contrast with these approaches, the SWIM conferences and community of practice are focused on developing accounting for the NBSW SoS.

The SWIM 2023 and SWIM 2024 conferences recognized the problems caused by the above-described fragmentations and the many resultant inefficiencies in water management and water services provisioning. For example, water utilities often do not invest enough in the maintenance of their built water infrastructure systems and, therefore, experience high water losses through their treatment and distribution systems for local communities. Or there is a lack of sufficient protection to preserve high-quality natural water sources. Or at larger scales, inter-basin disputes occur between States and often between Nations regarding responsibilities for managing water allocations and conserving water availability and quality – even as natural variability, extreme events, land-use change and other stressors further complicate decision-making (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Davis, Gardoni, Babbar-Sebens, Stuhr, Huston, Cauffman, Williams, Alanis, Anand and Vishwakarma2023b). The conferences recognized the great benefits that could potentially result from a better and more smartly integrated NBSW SoS, one that could: (1) optimize the reduction of water losses and other inefficiencies, (2) promote integrated risk management and (3) ensure affordable, reliable and resilient water services.

In turn, digital technologies and AI tools have already proven essential to overcoming fragmentation, pointing to correctable inefficiencies and integrating data acquisition, analysis, scenario-building and AI-enabled knowledge generation. The economic and social gains will be unprecedented for communities, and especially important for those with limited resources. A research project in the State of Georgia has already shown that harnessing AI with existing data and knowledge systems to efficiently and dynamically manage water security can save billions of dollars and scarce resources, both under normal and stressed conditions, and following extreme events. Digital technologies can also be used to improve communications, to instigate and develop lifelong learning and to build capacity and career development in the water sector – while also improving connections with communities and cross-sector institutions. The current project, led by the SWIM Center and collaborative network and by the US Geological Survey (USGS) and ORNL, seeks to minimize water losses and increase water delivery efficiencies. The project is entitled “Artificial Intelligence for water sector” (aiWATERS). The project brings in and is guided by stakeholder knowledge and data (e.g., from water utilities and State water agencies) that is then used to benefit the stakeholders and their communities.

The Smart One Water (S1W) vision

Bringing digital technologies and AI to the One Water concept is what we call our S1W vision. We see S1W as essential to developing more proactive, adaptive, water SoS plans and actions (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a,Reference Sinha, Thompson, Dermody and Dadialab,Reference Sinha, Vakaria, Karpatne and Ramakrishnac) and to more efficiently manage the NBSW SoS (Mukheibir et al., Reference Mukheibir, Howe and Gallet2014; Chester et al., Reference Chester, Grimm, Redman, Miller, McPherson, Munoz-Erickson and Chandler2015; FAO and WWC, 2018; Hager et al., Reference Hager, Haroon, Mian, Kasun and Rehan2021; Pokhrel et al., Reference Pokhrel, Shrestha, Hewage and Sadiq2022). We recognized that executing the S1W vision, prioritizing problems to be addressed, finding possible solutions and approaches and developing implementation pathways required a continuing, coordinated, inclusive engagement of professionals from across the water sector (e.g., researchers, practitioners, public and policymakers). The 3-year SWIM conference series provides waypoints on this trajectory. Outcomes of the SWIM 2023 Conference, which identified critical issues in water governance and management, were recently published (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a). The present paper focuses on the solutions and approaches identified at the SWIM 2024 conference and provides a steppingstone for the development of possible implementation pathways at the SWIM 2025 conference.

Realizing the S1W vision requires designing, assessing and improving governance and management of the water SoS across all elements and processes of the water cycle, in both built and natural environments, up to the watershed, river-basin or regional scales – as appropriate (NSF-ERC Planning Grant, 2020, n.d.b; 2020a–f,j; 2022). The scales of governance, management and operations also need to be nested with appropriate interventions at each level simultaneously (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009). S1W seeks to integrate data on water systems (natural, built and social) (cf. Figure 1, Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a) with a wide range of models and tools brought together into a cyberinfrastructure platform enabling stakeholder-centered, regional to national-scale water accounting, information sharing and decision support system (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Babbar-Sebens, Dzombak, Gardoni, Watford, Scales, Grigg, Westerhof, Thompson, Meeker and Shugart2023a,Reference Sinha, Davis, Gardoni, Babbar-Sebens, Stuhr, Huston, Cauffman, Williams, Alanis, Anand and Vishwakarmab).

Figure 1. Smart One Water implementation for desired societal impacts.

Advances in the Internet of Things, AI, sensor networks, communication systems, data analytics, automation, high-performance computing and human-computer interfaces are being leveraged by the SWIM Center, the US Geological Survey and Oak Ridge National Lab in their development of the aiWATERS knowledge and technology platform. aiWATERS is a digital, AI-enabled cyberinfrastructure platform (with appropriate safeguards and constraints) that uses advances in data analytics, AI and decision support systems to address the goals delineated in our Digital-Water ecosystem (Figure 1). The availability of a large amount of water data and computational resources, together with the development of advanced AI-enabled techniques tailored to specific applications, is fostering the development of more robust, trustworthy models and algorithms to process and analyze water systems. Meanwhile, the data collection and knowledge sharing landscape is evolving rapidly in the United States.

Workforce development and capacity building

We also recognized that executing the S1W vision would also mean developing education and training opportunities for workforce development and capacity-building, opportunities that connected well with communities, with water stakeholders and with our new AI-enabled digital age. Executing the S1W vision will mean developing systems thinking and transdisciplinary approaches, using the latest technologies in water-data science, increasing knowledge of means to improve the sustainability and resilience of NBSW systems in the face of continuing and emerging stressors (Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Davis, Gardoni, Babbar-Sebens, Stuhr, Huston, Cauffman, Williams, Alanis, Anand and Vishwakarma2023b) and developing strategies to increase participation by actively engaging communities through research and staff recruitment.

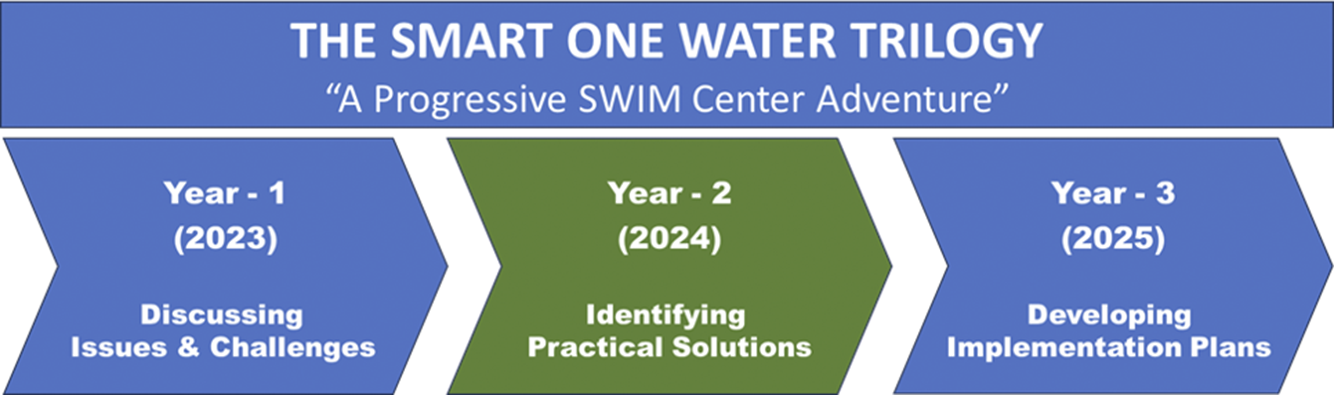

The SWIM conference and workshop trilogy

The S1W Trilogy is a 3-year program that pulls together water professionals from public agencies, private companies, academia and state and national organizations to identify, evaluate and develop practical solutions to some of our most critical water issues (Figure 2). Using a conference format consisting of motivational and keynote speakers, structured panel discussions and workshops, this interactive program incorporates audience participation, teamwork and crowdsourcing to provide a truly collaborative work product. The multiyear conference series started in 2023, which focused on identifying issues and challenges in water management. Year 2024 focused on identifying practical solutions and 2025 will identify and detail ways to implement these solutions. This paper presents the 2024 results.

Figure 2. The SWIM Center trilogy.

The distribution of contributors was:

-

• Private technology and service providers – 31%,

-

• Water and wastewater utilities – 25%,

-

• US Federal Government – 10%,

-

• Academia – 12%,

-

• Nongovernmental organizations – 9%,

-

• Regional/Compact/State/Local government agencies – 11% and

-

• Media – 2%.

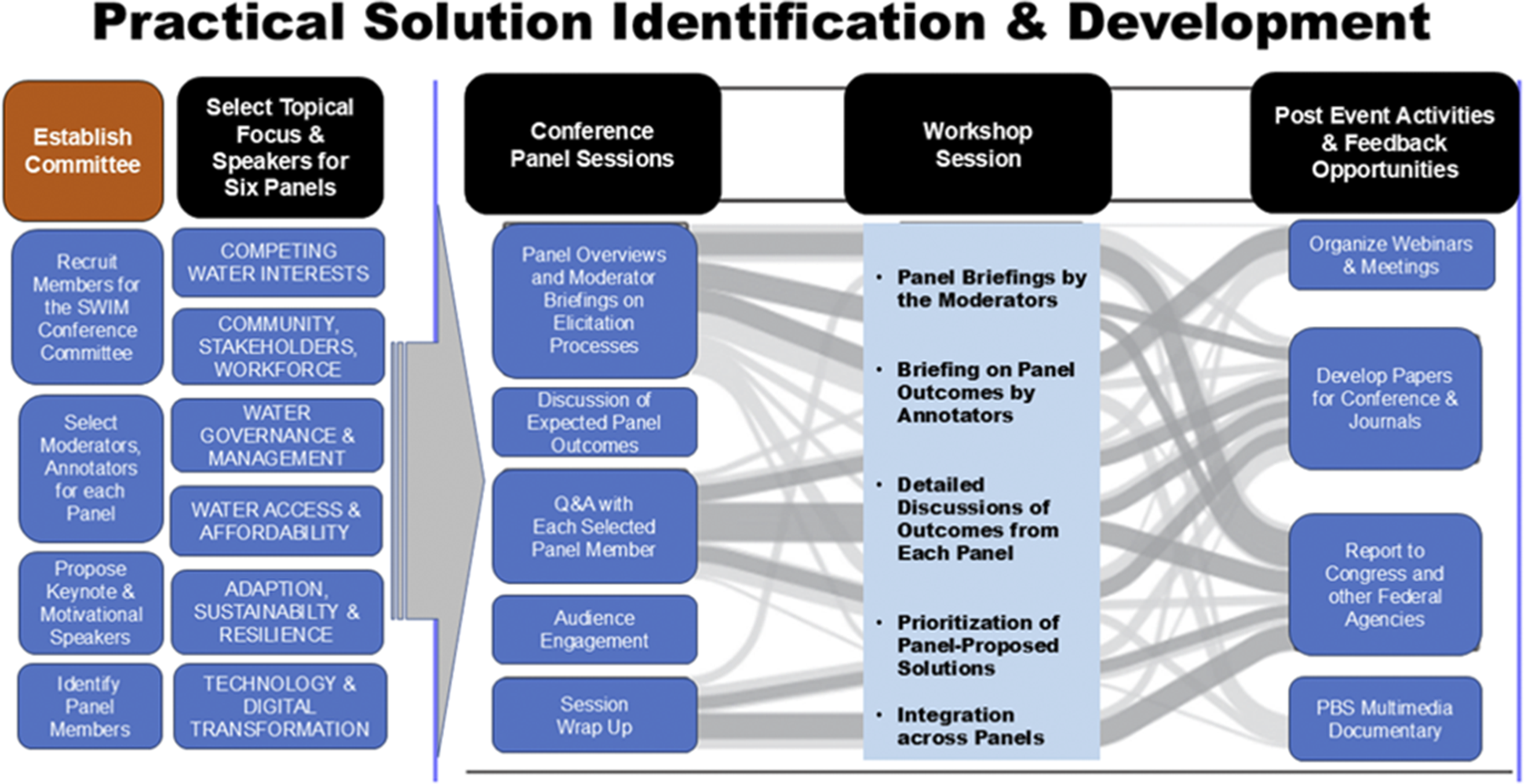

Conference and workshop participants were provided with review materials from Year 1, the SWIM 2023 conference and workshop. Figure 3 provides a flow chart illustrating the selection of speakers, moderators, annotators and panelists and the consequent discussions and feedback that helped identify, prioritize and develop practical solutions needed to meet the key water challenges (identified in the previous year’s conference). As in 2023, the Year 2 event (SWIM 2024) was organized according to six foundations and associated panels. The Year 1 outcomes identifying key challenges needing to be addressed (cf. Figure 4) were used as the basis for identifying, prioritizing and developing solutions in Year 2 (which this paper reports on). A new framework was created to enable identifying, prioritizing and developing solutions and approaches (Figure 5). The framework allowed the panels and other discussants to prepare, generate ideas/topics and ask probing questions. The framework asked all participants to: (1) consider the most essential challenges identified in Year 1, (2) provide examples of best practices pointing to possible solutions or approaches to address to challenges, (3) make recommendations on innovative solutions or approaches, (4) discuss possible barriers to implementation of those solutions/approaches and (5) start setting the stage for possible implementation pathways and some first steps. Participants were also asked to suggest metrics and milestones for measuring progress toward in addressing identified challenges (the lower row of boxes in Figure 5).

Figure 3. Flow chart illustrating moderator/annotator and speaker/panelist selections and processes for identification and development of SWIM-2024 practical solutions needed to address key water challenges (identified in the SWIM-2023 conference and workshop).

Figure 4. The SWIM Conference and Workshop 2023 overall outcomes.

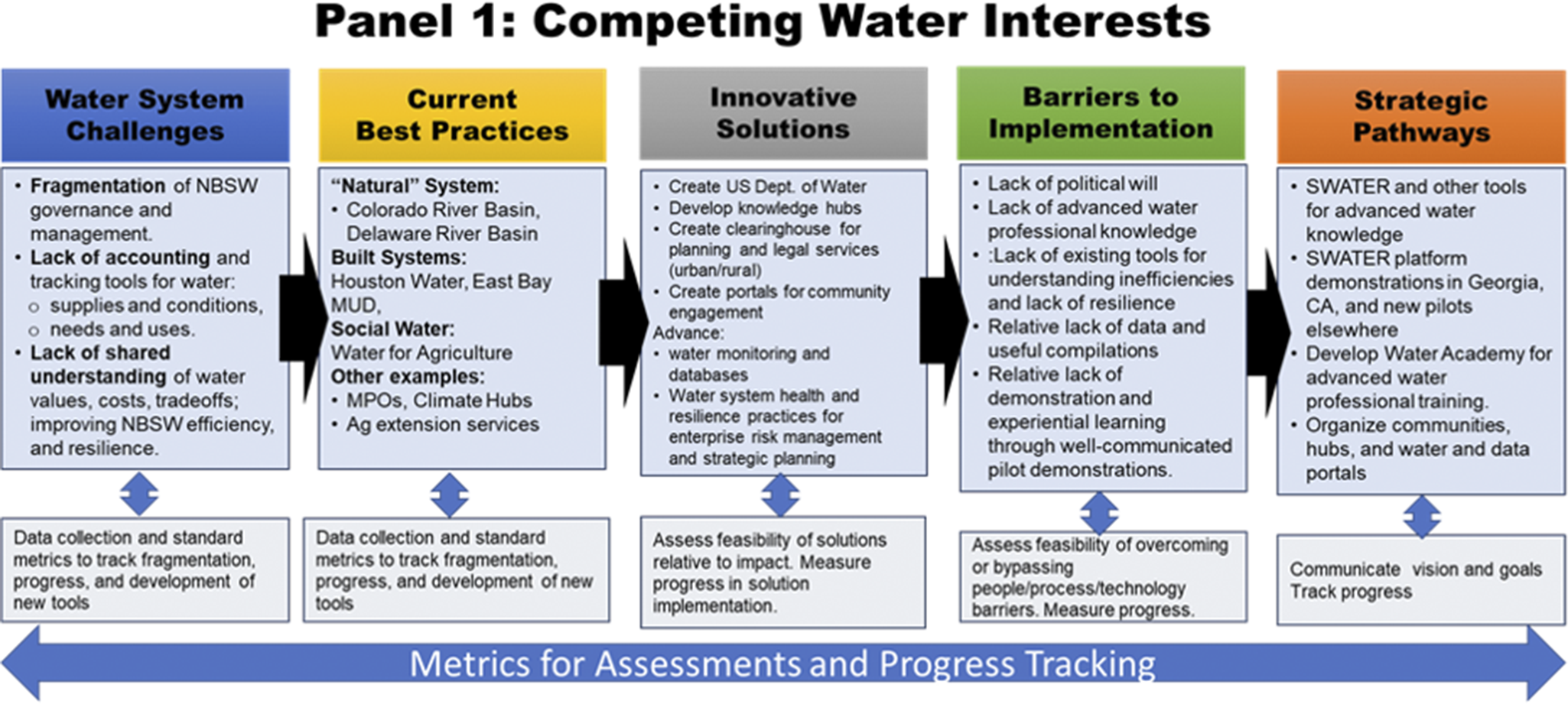

Figure 5. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Panel-1 Session. Note: “SWATER” refers to the aiWATERS platform.

SWIM conference trilogy: Year 2 accomplishments

The outcomes of the Year 1 SWIM 2023 conference are discussed in Sinha et al. (Reference Sinha, Glynn, Gardoni, Tang, Sebens, Dyckman, Helgeson, Berk, Thompson, Williams, Graf, Vallabhaneni, Malkawi, Baumann, Dermody, Wiersema, Sinclair, Hyer, Johnson and Eggers2025a) (cf. Figure 4). The key SWIM 2024 conference and workshop (Year 2) findings and recommendations are discussed below. The outcomes for each of the six panels are presented first, followed by challenges, best practices, innovative solutions, barriers to implementation and strategic pathways (Figure 5).

Panel 1: Competing water interests

Overall outcomes

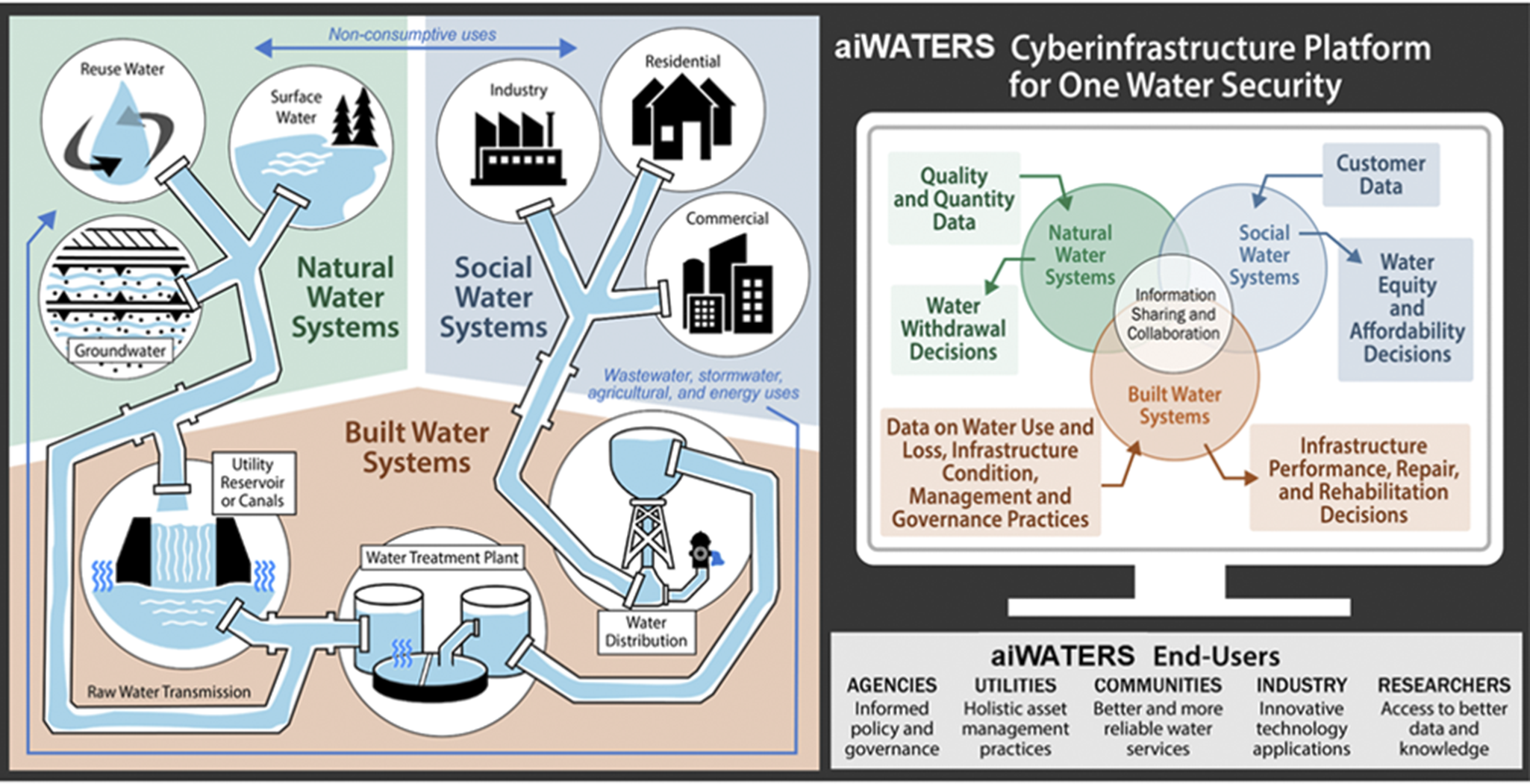

Progress was made in identifying innovative solutions and approaches to address the most critical “Competing water interests” challenges initially identified in the SWIM 2023 conference and workshop. Importantly, the Year 2 results, synthesized in Figure 5 for panel 1, point to possible pathways for implementation of the identified solutions and approaches. The identification of the aiWaters platform as a possible tool for helping implement proposed solution recommendations, overcome barriers and meet the needs of an ecosystem of different end-users and tradeoff decisions was an essential finding of the panel (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Interactions between the natural, built, and social water systems, the role of the aiWaters AI-enabled data and knowledge platform, and implications for water end-users and decision support.

Water system challenges

Fragmented governance and management of water – from source to tap – accompanied by a lack of accounting and tracking tools that could be used to inform decision-making across the water system were seen as critical challenges to be addressed. These challenges were accompanied by knowledge gaps relating to assessing water valuations, costs and system (in)efficiencies – all of which are needed to quantify tradeoffs and improve governance and management in the water SoS. Adopting an S1W approach for governance and management at watershed and/or river basin scales was seen as a key overarching need that would meaningfully integrate data and knowledge of NBSW systems. NWS comprises a complex network of interconnected and difficult-to-observe hydrologic processes, often resulting in data gaps and uncertainties due to limited monitoring. BWS are complex and inadequately understood, with interwoven people, technology and governance models. Despite the general abundance of data from sources like water utilities, insights into many operational processes still remain limited. SWS involves many individual and institutional actors who make decisions about water use, needs and protection. Their actions are driven by a wide range of factors, including health, cost, economic development, laws and regulations, cultural norms and aesthetics.

Current best practices

There are several examples that not only showcase best practices but also point to ways of addressing critical challenges. They occur in different geographic areas but are organized around principles of integration and collaboration in watershed management. The Colorado River Basin (CRB) uses increasingly integrated water governance and management, including water accounting for the lower basin (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Pitt, Keaton Wilson, Martin and Morton2023). The increased attention to the need for integrated management of the CRB is a natural result of the overallocations of water (relative to availability) given the competing demands among upper and lower basin States and across a diverse mix of consumptive water uses (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Lamsal, Marston, Dhakal, Sangha, Rushforth, Wei, Ruddell, Davis, Hernandez-Cruz, Sandoval-Solis and Schmidt2024). The Delaware River Basin engages in highly collaborative integrated management (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman2015; Moore, Reference Moore2021). Both examples, but especially the CRB, include important consideration not only of public water supply needs but also of agricultural needs for water, and associated tradeoffs (e.g., Glennon, Reference Glennon2018). For urban water utilities, East Bay Metropolitan Utility District (MUD) in Oakland, CA (EBMUD Public Affairs, 2022), and Houston Water (Loftus et al., Reference Loftus, Murata and Stonecipher2021; Cardno, Reference Cardno2022) offer examples of state-of-the-art practices, including the use of technology, asset management and monitoring. Many excellent tools and methodologies are already available for creating water accounts, tracking water from source to tap and assessing efficiencies, values and cost–benefit tradeoffs. But so far, they have seen limited use for watershed to basin-scale integrated governance and management across the NBSW SoS, in part because of a lack of trusted knowledge hubs and limited sharing and training opportunities for water professionals in water agencies and utilities. However, some possibilities for improving water planning, management and operations, specifically for improving SoS efficiencies, resilience and trade-off decision-making, are pointed to by:

-

• metropolitan planning organizations used in urban planning but applied in a water context to both urban and rural areas,

-

• extension services used to improve agricultural practices and

-

• climate hubs used to enable more resilient futures.

Innovative solutions

Our choices of innovative solutions and approaches are bolstered by existing knowledge in water management and in other areas, including:

-

• accounting and tracking of natural resources and of their uses for different societal needs;

-

• design, implementation and curation of monitoring and assessment networks;Footnote 1

-

• establishment of trusted protocols and standards for monitoring, efficiency and resilience assessments and trusted methodologies for water valuation, economics and financing;Footnote 2

-

• communication and implementation of best practices for water operations and risk-informed strategic planning;

-

• creation of knowledge hubs for professionals and portals for community engagement.

Figure 5 provides an overview of some of the specific innovative solutions and approaches that resulted from the SWIM 2024 conference and workshop. Importantly, the proffered solutions show that there is a need for both bottom-up engagement applications by communities and water professionals, combined with top-down coordination and leadership. The latter could be offered by creating a Federal-level Department of Water that either regrouped or eliminated the need for the 27 siloed Federal agencies currently tasked with different aspects of water management in the United States. Such a recommendation was recently made by the President’s National Infrastructure Advisory Council under the Biden Administration (Vereckey, Reference Vereckey2023; NIAC, 2023b). However, the history of water federalism in the United States (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Lauber, van den Hoogen, Donmez, Bain, Johnston, Crowther and Julian2024) suggests major challenges in the establishment of such a Department – especially if it wanted to impose national-level policy and requirements on States and local to regional contexts, as opposed to offering coordination and knowledge services and tools or platforms that could be used by utilities and States to improve water operations and management.

Barriers to implementation

The most commonly cited barriers to solution implementation included (1) lack of political will, (2) lack of advanced professional knowledge (and communication and sharing of the knowledge) and (3) lack of understanding of already available tools and technologies. Data insufficiencies and inadequacies were also mentioned. Addressing these is especially important for the use of AI, such as the process-informed structured machine learning being conducted as part of the creation of the aiWATERS project and knowledge and technology platform, and of its implementation in States across the United States (GA, CA, TX, CO and WV). Much of the effort has been focused on built water system operations, but initial integration with the NWSs and SWSs has also pointed to benefits, greater system efficiencies and improved resiliency that would accrue through enhanced integration and understanding. For example, additional research is needed to establish trusted accounting metrics for natural water resources and also to establish consistent, useful valuation practices and trade-off methodologies. These could then inform both the design of sustainable shorter-term business models and water operations, as well as strategic planning and investments for longer-term water SoS resilience needs. And yet, prioritization of resources through informed decision-making is a major barrier for progress. Valuing water means recognizing and considering all the diverse benefits and risks provided by water, and encompassing its economic, social and ecological dimensions, as well as its diverse cultural and religious meanings.

Strategic pathways

The AI-enabled SWIM/USGS/ORNL project and knowledge and technology platform entitled aiWATERS is generating considerable interest across the professional water community. The project was started by Virginia Tech and USGS to examine and quantify water losses (Sakry, Reference Sakry2022). With the help of ORNL, and following the increasing input and interest from stakeholders (e.g., in GA, CA, TX, OR, WV, AK and more), aiWaters’ capabilities are rapidly expanding and are helping more broadly assess water service efficiencies and delivery economics from source to tap (e.g., Vekaria and Sinha, Reference Vekaria and Sinha2024; Sinha et al., Reference Sinha, Vakaria, Karpatne and Ramakrishna2025c). The aiWATERS project will help overcome many of the barriers and challenges identified above. aiWATERS aims to aggregate and structure a large amount of context-dependent water data and knowledge, which is then processed and interpreted through AI tools to meet the needs of a diverse set of end-users and decisions (Figure 6). The development of a Water Academy that would offer advanced water training and internships is also an excellent possibility, currently in development by the greater SWIM community of practice. Work is also being initiated in the area of community engagement and portals, in part through the aiWATERS project. However, exploration of new ways to finance water services still needs further research (and is not shown in Figures 5 or 6), particularly making users pay their fair share. Full cost pricing of water needs to be implemented. This also ties in with the need to improve methodologies to (1) determine the full cost of water provisioning services, (2) assess the value of water in its use for different purposes and (3) establish useful metrics for assessing efficiencies and resilience in the water SoS and in its component systems.

Panel 2: Community, stakeholders and workforce

Overall outcomes

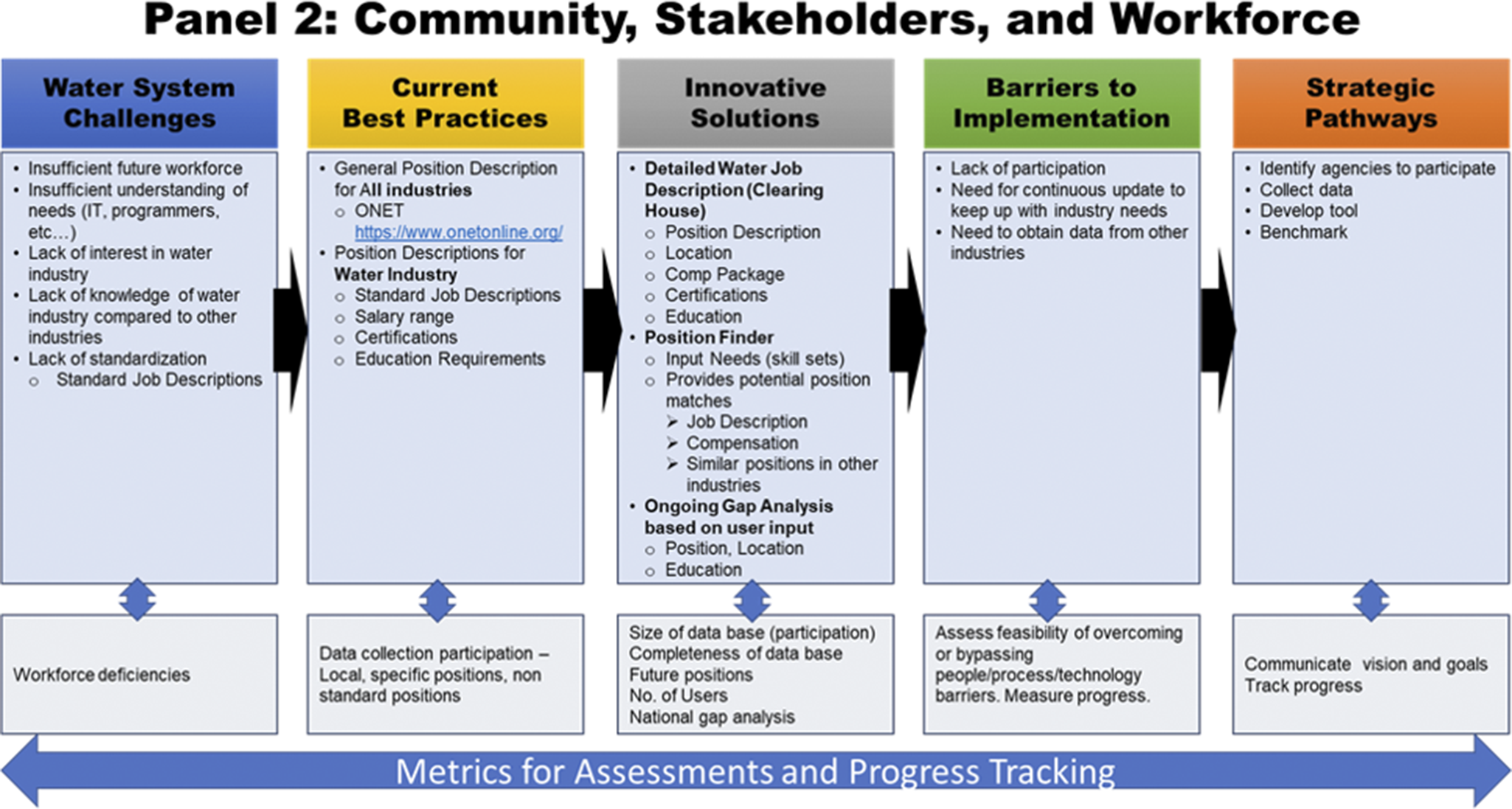

The synthesis of stakeholder discussions, community feedback and workshop exchanges revealed a multidimensional view of workforce and community challenges facing the water sector (see Figure 7). The graphic captures the evolving system-wide needs and Panel 2’s solution rubric. The solutions and approaches identified by the panel aimed to coordinate efforts to attract and develop a resilient workforce while strengthening connections between communities and the water industry.

Figure 7. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Panel-2 Session.

Water system challenges

There is an urgent need to expand stakeholder engagement and deepen community participation. Most communities lack awareness of water careers, and existing communication often fails to connect with local cultural and generational values. Simultaneously, small utilities struggle to compete for talent due to limitations in visibility, flexibility and compensation. A system-wide effort is needed to involve Community-Based Organizations (CBOs, i.e., nonprofit groups representing community interests), universities and trade schools to build cultural trust and support inclusive strategies that reflect varied workforce motivations – from stability and benefits for mid-career professionals to purpose-driven, flexible opportunities for younger workers.

Current best practices

Current recruitment strategies and workforce planning in the water sector often remain fragmented and overly technical, emphasizing credentials over competencies and skills. Although some utilities have begun outreach efforts, these are typically ad hoc and underutilize behavioral, cultural and psychographic insights that could inform better job matching. There is little use of predictive or real-time workforce analytics, and few national benchmarks exist for comparing job types, compensation packages or cultural fit indicators across regions and utility sizes.

Innovative solutions

Emerging approaches include partnership models with CBOs to codesign culturally resonant outreach, digital twin simulations for skill visualization and the use of human-in-the-loop AI tools for capturing behavioral and experiential insights. Success stories highlight how social media campaigns, storytelling from current staff and gamified experiences can inspire interest from new demographics. Tools such as interactive apps, augmented-reality/virtual-reality training and national job-skill databases allow both candidates and utilities to make informed decisions aligned with values, skillsets and context-specific job demands. The need to envision what future water-utility structure and operations might look like, and then determine the types of skills needed, was also proposed. The water sector needs to hire for the future and not just react to crises in the present.

Barriers to implementation

The sector lacks a unified workforce planning framework that incorporates data-driven tools, predictive models and flexible hiring practices. Without better data infrastructure, utilities cannot effectively identify future workforce gaps, benchmark recruitment outcomes or craft localized talent strategies. Many small utilities lack the technical or financial capacity to participate in innovation pilots. There is also limited adoption of feedback loops, such as exit interviews or behavioral analysis, that could illuminate the cultural or structural reasons for attrition. Additionally, some local governments may have rigid hiring requirements, which can sometimes turn out to be major impediments. Having broad regional and national-scale agreements regarding water-sector workforce requirements and hiring/retainment/development processes could potentially help overcome or reduce such impediments.

Strategic pathways

To build long-term resilience, the sector must institutionalize continuous, trust-based public engagement and transparent communication. This includes framing water careers around public health, environmental stewardship and community impact; embedding storytelling into outreach; and creating low-barrier pathways into water roles. Strategic investments in national workforce data systems, AI-enabled recruitment planning and CBO compensation models are essential. Public awareness and value perception of water services must be elevated to support the next generation of workers and to foster civic stewardship for water systems.

Panel 3: Governance and management

Overall outcomes

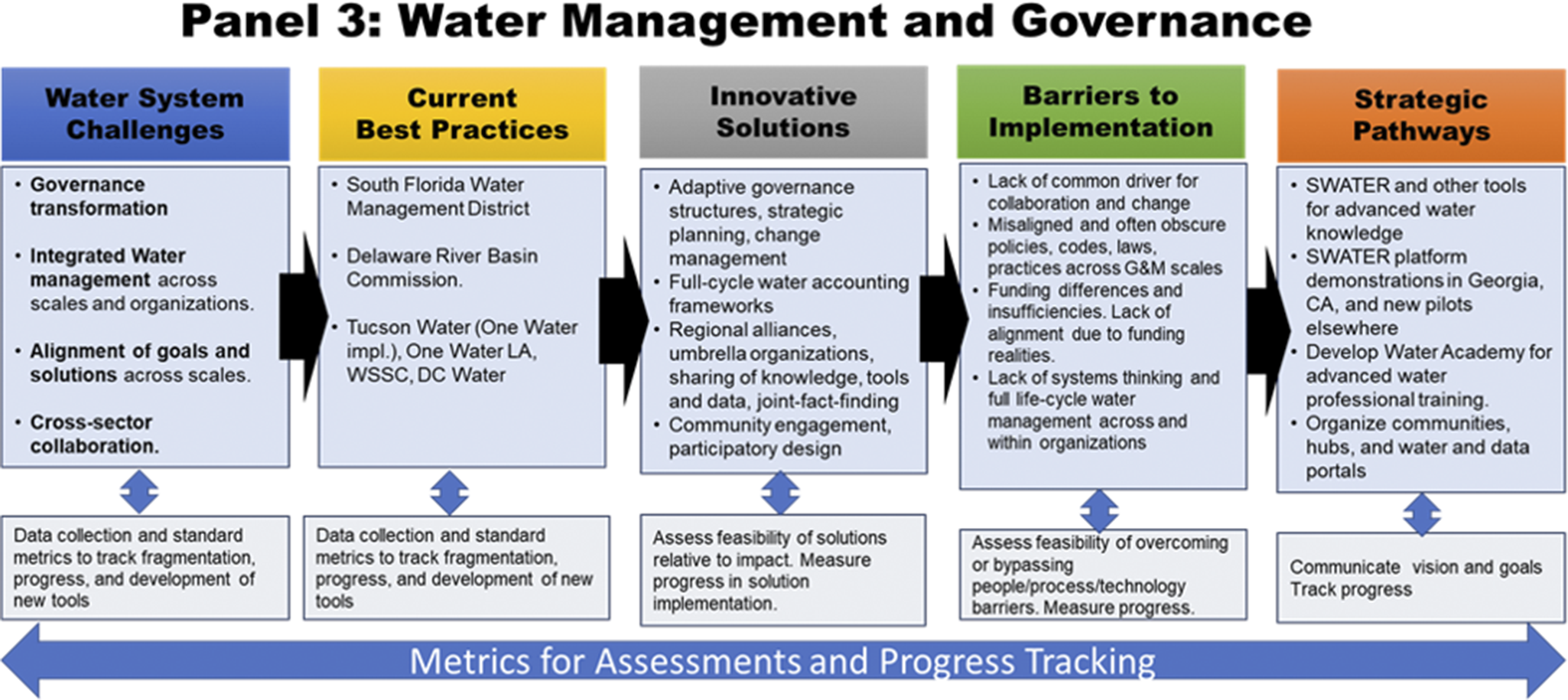

Water systems across the United States face increasing governance and management challenges driven by climate change, population growth and the need for sustainability and equity (Figure 8). These challenges necessitate a transformative shift in institutional coordination, integrated management and cross-sector collaboration. Best practice examples exist showing how adaptive, participatory and regionally aligned governance by different types of institutions can address complex issues of water supply, quality, ecosystem restoration and resilience (e.g., South Florida Water Management District [SFWMD], Delaware River Basin Commission [DRBC] and Tucson Water). Innovative solutions ranging from adaptive governance and strategic planning to full water accounting and participatory engagement offer scalable models for holistic water management. However, widespread implementation is hindered by institutional silos, policy misalignment, fragmented funding and a lack of comprehensive water data. Strategic pathways forward include S1W approaches, collaborative platforms like those in Georgia and California, advanced training through water academies and transparent water and data portals. These tools and frameworks collectively support a paradigm shift toward more integrated, agile and inclusive water governance.

Figure 8. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Panel-3 Session.

Water system challenges

Water systems face growing management and governance challenges that require a transformative shift in how institutions operate and coordinate. Governance transformation is essential to overcome fragmented responsibilities and outdated decision-making frameworks, enabling more adaptive and participatory approaches. Integrated water management is critical for addressing the interconnected nature of water supply, wastewater, stormwater and natural systems and regulation. However, it is often hindered by siloed agencies and conflicting mandates. Achieving alignment of goals and solutions across jurisdictions and stakeholders remains a persistent obstacle, particularly as utilities attempt to balance economic viability, sustainability, equity and resilience objectives. Effective cross-sector collaboration with public agencies, private utilities, community organizations and other infrastructure sectors is key to implementing holistic strategies, leveraging resources and ensuring that water system governance is responsive to the multifaceted pressures of climate change, population growth and environmental justice.

Current best practices

In the context of governance transformation, integrated water management, goal alignment and cross-sector collaboration, several US water institutions offer best practice examples – particularly the SFWMD, the DRBC (Kauffman, Reference Kauffman2015; Moore, Reference Moore2021) and Tucson Water (e.g., Zuniga-Teran and Tortajada, Reference Zuniga-Teran and Tortajada2021). These entities illustrate how innovative, collaborative and adaptive governance can address complex water system challenges. SFWMD is a leading example of governance transformation and integrated water management in a highly complex and environmentally sensitive region (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Angelo and Hamann2009). It operates under a broad mandate that encompasses water supply, flood control, water quality and ecosystem restoration across a 16-county region (e.g., Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Stanek, Frantzeskaki and Yeh2016). SFWMD’s work on the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan demonstrates alignment of federal, state and local goals with ecosystem restoration and water supply outcomes (Wetzel et al., Reference Wetzel, Davis, van Lent, Davis and Henriquez2017).

The DRBC exemplifies cross-jurisdictional governance and alignment of water management goals across state boundaries. Established through a compact among four states (Delaware, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania) and the federal government, the DRBC coordinates water allocation, drought management, pollution control and ecological health across the entire basin. The Commission’s Flexible Flow Management Program and Special Protection Waters program demonstrate how data-sharing, scientific consensus and regulatory cooperation can protect shared water resources while balancing competing interests. Its governance structure provides a model for resolving conflicts (Moore, Reference Moore2021). Tucson Water is also recognized for its leadership in integrated urban water management and community collaboration in a semi-arid region (Gerlak et al., Reference Gerlak, Elder, Thomure, Shipek, Zuniga-Teran, Pavao-Zuckerman, Gupta, Matsler, Berger, Henry, Yang, Murrieta-Saldivar and Meixner2021). The utility has successfully diversified its supply portfolio through groundwater recharge, reclaimed water reuse and conservation-based demand management (Zuniga-Teran and Tortajada, Reference Zuniga-Teran and Tortajada2021). Tucson Water’s Water Security Program and One Water approach exemplify alignment of goals across sectors, particularly by incorporating climate resilience, affordability and public trust into decision-making (Tucson Water, 2021; Zuniga-Teran and Tortajada, Reference Zuniga-Teran and Tortajada2021). Their proactive public engagement and education campaigns have fostered broad community support for conservation and innovation. Together, these examples highlight how adaptive institutions can integrate across scales, jurisdictions and sectors to address the governance and management challenges facing modern water systems.

Innovative solutions

Innovative solutions in water management and governance are increasingly rooted in integrated, adaptive and participatory frameworks that allow more flexible and inclusive community-supported responses to often poorly predictable future stresses arising from climate change, land-use change, competing demands for water and environmental degradation. Adaptive governance enables flexible decision-making through iterative learning, scenario planning and responsive institutions (e.g., Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin) (Murray Basin Plan, 2024). Strategic planning, like California’s Water Plan (2023), links long-term urban development, land use and climate considerations with water resource sustainability. Full water accounting uses tools like satellite data and national water balances (e.g., Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meterologu=y, and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) system) to quantify all inflows, uses and losses, providing a more complete foundation for decision-making. These approaches support more holistic and resilient management practices that go beyond traditional supply–demand calculations.

Equally important are innovations in collaboration and stakeholder engagement. Regional alliances – such as the CRB agreements – demonstrate how cross-jurisdictional partnerships can enable shared governance of water systems. Data and tool sharing initiatives, like NASA’s OpenET platform (OpenNet, 2025), democratize access to real-time water data, empowering users from farmers to regulators. Finally, community engagement and participatory planning ensure that decision-making processes are more inclusive, equitable and grounded in local knowledge. Examples such as New Zealand’s co-governance with Māori communities (Co-governance, 2023) and California’s stakeholder-driven Bay Delta planning (Bay Delta, 2025) illustrate how integrating local voices can lead to more inclusive, societally supported and sustainable water management and governance. Together, these innovations represent a paradigm shift toward transparent, collaborative and adaptive water governance.

Barriers to implementation

Despite the availability of innovative solutions in water management and governance, several barriers hinder their effective implementation. A key obstacle is the lack of collaboration among agencies, jurisdictions and stakeholders, which leads to fragmented decision-making and duplication of efforts. Misalignment of policies, legal frameworks and regulatory codes across sectors or government levels further complicates coordination, making it difficult to develop coherent strategies that address complex and interlinked water challenges. Additionally, institutional inertia and sectoral silos often prevent the adoption of systems thinking, which is essential for understanding water issues as part of a broader social, ecological and economic context.

Another major barrier is the disparity in funding mechanisms and inefficiencies in resource allocation. Variability in funding priorities across agencies and geographic regions can undermine the continuity and scaling of successful initiatives. The absence of comprehensive and transparent water accounting compounds these issues, as decision-makers often lack reliable data to guide investment, planning and policy evaluation. Without integrated accounting and a shared understanding of water availability, use and risk, opportunities for sustainable management are missed. Ultimately, these barriers limit the capacity of institutions to respond adaptively to emerging challenges such as climate change, population growth and competing demands for water.

Strategic pathways

Strategic pathways in water management and governance are increasingly embracing integrated, data-driven and capacity-building approaches to tackle the growing complexity of water-related challenges. One promising direction is the advancement of S1W management, which leverages digital technologies, real-time monitoring and system-wide data integration to optimize water allocation, infrastructure performance and ecosystem sustainability. States like Georgia and California are leading the way through the development of a collaborative platform, facilitating coordinated decision-making across jurisdictions and sectors. These platforms foster regional partnerships, align policies and integrate data systems to support broadly inclusive and adaptive water governance.

In parallel, building institutional and human capacity is critical for the success of these innovations. Water academies offer advanced training in areas such as integrated water resource management, scenario planning and climate risk assessment, helping to prepare the next generation of water professionals. Additionally, open-access water and data portals serve as foundational infrastructure for transparency and informed decision-making. These portals enable the public, planners and policymakers to access critical hydrological, climatic and usage data, thus supporting more responsive and evidence-based governance. Together, these strategic pathways embody a shift toward a more agile, inclusive and informed water management paradigm.

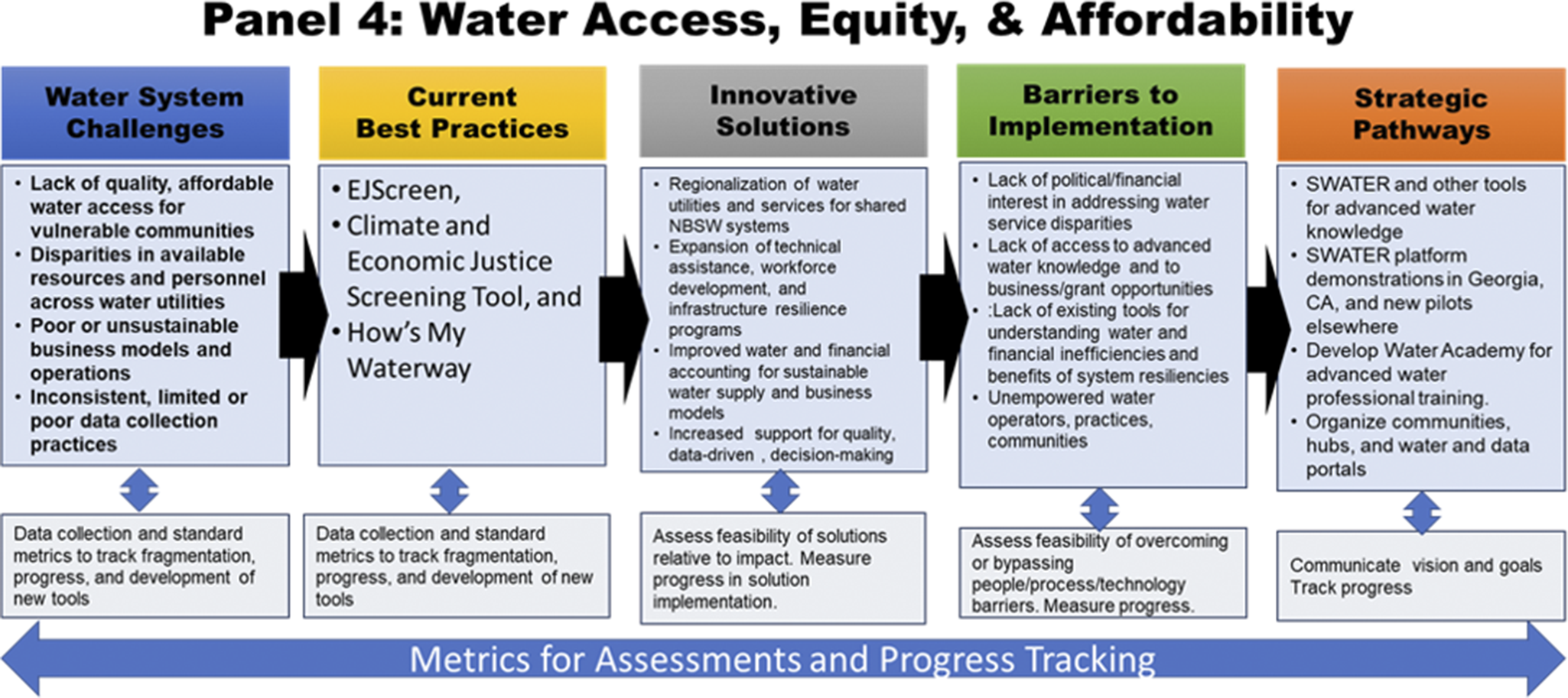

Panel 4: Water access and affordability

Overall outcomes

The overall outcomes synthesized from the Panel 4 discussions are presented in Figure 9. Four solutions and approaches – involving regionalization, strategic training, improved business models and access to data and knowledge platforms and tools – were examined and discussed.

Figure 9. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Panel-4 Session.

Water system challenges

Water is a necessity for life, and ensuring that each community has improved access to clean, safe and affordable water requires the implementation of the seven strategic pillar goals. Challenges to improved access and affordable services can stem from practical hurdles, such as a lack of resources in utilities and municipalities to support needed services. Lack of understanding on where, why and how community members can implement accessible and affordable water services is also a major problem – and so are limitations in acquiring and managing funds to enable and maintain services. Challenges are especially dire for small water systems (primarily small and rural systems, which comprise about 90% of water systems in the United States), and stem from under-resourcing, limited staff and difficulties complying with policies often designed for larger systems.

Current best practices

Currently available data-driven tools – such as EJScreen (Osakwe et al., Reference Osakwe, Motsinger-Reif and Reif2024), the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (Shrestha et al., Reference Shrestha, Rajpurohit and Saha2023) and How’s My Waterway (USEPA Office of Water, 2024) – have proven valuable in helping industry incorporate social indicators to assess the resilience of communities to environmental stressors. However, adoption of these tools has been limited by a lack of workforce trained to use such tools, and a lack of unified national standards for data collection in the water sector. Some communities benefit from privatization, achieving efficiency and better service. However, concerns arise when the needs of the moment, and/or short-term profits, are repeatedly prioritized over longer-term maintenance needs or investments for the future. The resilience and sustainability of water services to communities end up degraded and can ultimately lead to high costs that a community may not be able to afford. Therefore, it is important to have governance and policies that can help prevent short-termism and/or predatory practices, and especially so for small or vulnerable communities that lack resilient funding or access to economies of scale (Osakwe et al., Reference Osakwe, Motsinger-Reif and Reif2024).

Innovative solutions

Solutions proposed included regionalization efforts to consolidate smaller systems into regional utilities, thereby generating cost savings, improving service quality and reducing environmental impacts. For example, in Camden County (NJ), regionalization reduced treatment plants from 52 to 3, improved water quality and enabled economic development (US Water Alliance, 2022).

Another solution focused on workforce development and the broadening of educational programs beyond science and engineering to include marketing, public outreach and other soft skills. Strategic training initiatives, such as examining the Circular Water Economy program and analyzing its case studies, could also be used to foster innovation.

Of equal or even greater importance is the need to improve funding options and business models for communities. This was the third proposed solution. Beyond grants, low-interest loans, longer payback periods and state-revolving fund programs could help utilities in their delivery of services. Operational and maintenance savings from infrastructure upgrades can offset debt service costs. The process of acquiring funding and/or establishing viable business models could potentially foster deeper community connections, improve alignment with strategic priorities and strengthen the financial resilience of water deliveries.

As a last (fourth) solution, the need to improve data practices and understanding and addressing of community-specific needs was proposed. This included needs arising from flooding or storm recovery. Data and visualization tools could improve understanding of needs and knowledge gaps – understanding which could then help procure funding, strengthen collaborations and identify regionalization opportunities.

Barriers to implementation

The siloed nature of water agencies is a hindrance to solving challenges and identifying opportunities. Lack of data-informed understanding of water systems, funding limitations, political will and a lack of courageous leadership were identified as key obstacles to implementation. And so is the high number of small, vulnerable utilities, and the fact that there is no well-established framework or processes for regionalization. There was a call for better governance and leadership focused on long-term innovation and collaboration. Robust collaboration and coordination between agencies and communities can empower learning from others.

Strategic pathways

Regionalization should be evaluated for each community. Economies of scale, standardization and effective resources could be realized if implemented. Political and other factors may be obstacles that each community will need to evaluate and appropriately address. Advanced data-driven platforms are needed to provide knowledge, information, visualization and analysis tools, and best practices and standards to help communities address accessibility and affordability issues. Finally, there may be some examples (not known to the panel at the time of their discussions) of successful public assistance programs for utilities that could help in the design of strategic pathways for implementation of the solutions and approaches identified by the panel.

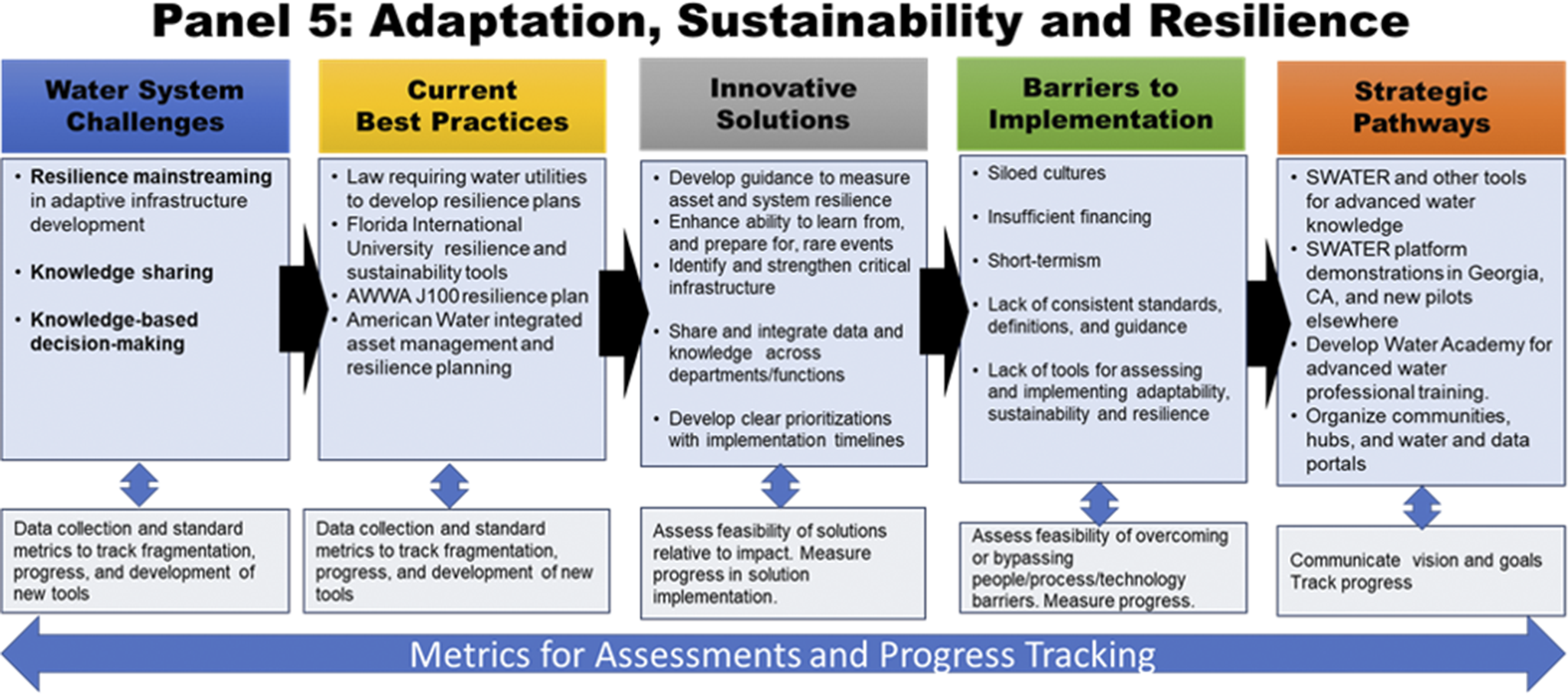

Panel 5: Adaptation, sustainability and resilience

Overall outcomes

The synthesis of stakeholder discussions, community feedback and workshop exchanges on water adaptation, sustainability and resilience is presented in Figure 10. The discussions revealed a challenging and constantly evolving risk landscape for water utilities, given the threats posed by climate-induced hazards and cyber threats from nation-state and criminal actors. The discussion identified some current best practices but also a remaining need to improve education, training, knowledge sharing and implementation of technical and adaptive management solutions to improve the resilience and sustainability of water infrastructure.

Figure 10. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Panel-5 Session.

Water system challenges

The water sector needs resilience, adaptive management and sustainability concepts to become mainstream practices. This will help address challenges presented by the dynamic nature of natural and man-made threats, while at the same time ensuring that the sector has the resources to operate, maintain, repair and replace water infrastructure to sustainably meet current and future consumer demands. Addressing these challenges will require adequate funding, as well as strategic planning and the availability of needed data, to implement necessary changes while meeting regulatory requirements. This means that greater attention is needed in the development of improved business models and financing for water services, as well as in the development and use of strategic planning.

Current best practices

The panel identified a few tools, laws, plans and practices that could potentially help create examples of best practices (cf. Figure 10). Outside of the panel discussions, one of the co-authors of this paper suggested the best practice example of NY State, which is incorporating sea level rise and flooding evaluations into their asset management guidelines, thereby linking infrastructure replacement needs with anticipated climate change impacts. Generally, the panel noted a lack of best practice mechanisms and approaches that it could cite as examples to cross-sector, regional-scale collaborations enabling improved water SoS adaptation, sustainability and resilience. Indeed, the water SoS has cross-linked dependencies with many other infrastructure services (e.g., power, communications and transportation) that may not be fully considered when planning for evolving threats and hazards. Water utilities do have an opportunity, however, to collaborate with other water utilities in the region to apply a more holistic approach to resilience and sustainability. Good quality, relevant, structured and well-maintained data are essential.

Innovative solutions

Develop and empower transformative leaders to “ACT” (adapt, create and transform) in championing adaptation, sustainability and resilience, and ensure they become mainstream elements of effective utility management practice. This will entail assembling and sharing best practices, developing data standards and protocols, developing a consistent risk and resilience-based planning approach, including how to incorporate complex threats due to climate change and evolving cyber threats aligned with operational and asset management approaches to achieve resilience objectives. Implementation of this solution will also mean investing in associated workforce development through targeted training, knowledge transfer and succession planning.

Barriers to implementation

The benefits of adaptation, sustainability and resilience are not currently well understood, making communication and collaboration across jurisdictions or among infrastructure system operators challenging. Additionally, existing governance structures and budget allocations are often siloed, with departments/divisions operating under separate mandates, metrics and funding streams. Best practice in this area needs to be defined and shared.

Furthermore, there is no regulatory requirement for resilience or sustainability, making it difficult to justify such investments in comparison to those needed to address aging infrastructure or growth to meet increasing system demands. There is a pressing need to improve data and processes/procedures to evaluate system vulnerability and undertake risk assessment for both chronic and acute risks. There is also a need to identify how, when and why to measure key indicators and cross or inter-system performance criteria.

Strategic pathways

Once the backbone of good quality, relevant, structured and accessible data is in place, develop advanced data analytic tools for proactive decision-making. Equip decision-makers with the necessary awareness, skills and tools to interpret and integrate scientific data into existing work processes or decision-making frameworks, specifically the decision support tools for long-term management and the necessary data to make informed asset management decisions that lead to enhanced reliability and resilience of water utilities. Develop the mechanisms for learning from disruptive events, incorporating learning into guidance and best practices and disseminating knowledge through a Water Academy and water and data portals.

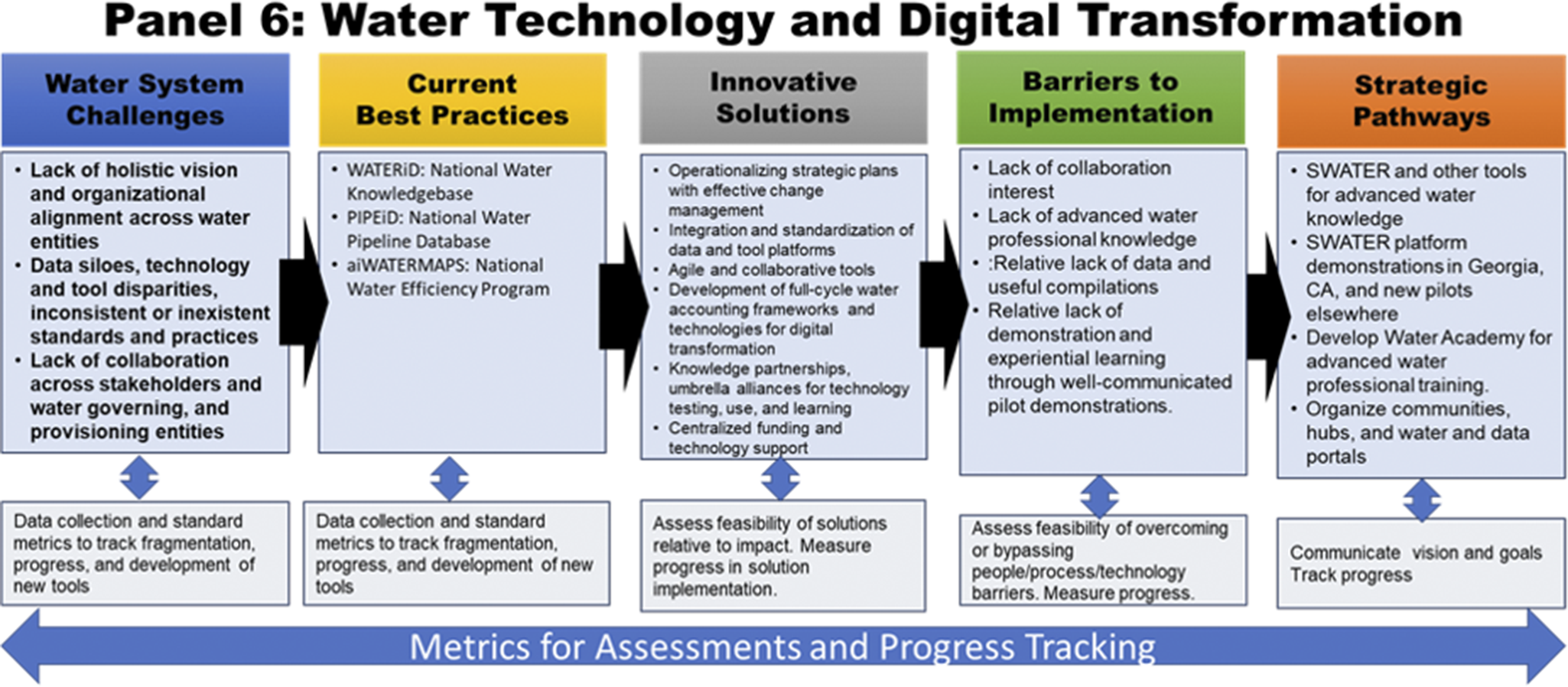

Panel 6: Technology and digital transformation

Overall outcomes

Figure 11 presents synthesized outcomes from conference and workshop discussions centered on digital transformation in the water sector. The five colored boxes represent Challenges, Current Practice, Innovative Solutions, Barriers to Implementation and Strategic Pathways. Below them, evaluation metrics for digital maturity, resilience and workforce engagement guide utilities in tracking transformation progress. The panel emphasized that digital transformation must be purposeful, inclusive and resilient – aligned with business goals, rooted in user needs and protected by robust cybersecurity strategies.

Figure 11. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Panel-6 Session.

Water system challenges

The sector must accelerate the creation of a national digital innovation ecosystem that supports the implementation of the seven strategic pillars, while recognizing the need for localized flexibility. Key challenges identified included:

-

• fragmented data silos across Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA), Geographic Information System (GIS) and Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) platforms;

-

• lack of cross-functional coordination;

-

• cultural resistance to change; and

-

• limited integration of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) systems. Integrating IT (Information Technology) and OT (Operational Technology) in water management merges data analysis with physical operations, using IoT sensors and systems for real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and automated control, leading to significant gains in efficiency, resource optimization, leak detection, and sustainability, while also improving security by bridging data gaps between business intelligence and operational control for smarter, more resilient water systems.

Additionally, water utilities struggle to retain institutional knowledge as senior staff retire without capturing their expertise in digital form.

Current best practices

Utilities are gradually adopting digital tools (e.g., Houston’s Water Data Lake), but progress is uneven. Many implementations are reactive or isolated – driven by IT departments or vendors – without a sustained roadmap linking technology investments to mission-critical outcomes. Few utilities have a cohesive business plan for digital transformation that aligns with operational needs, cybersecurity requirements and staff readiness. Emerging good practices include internal strategy councils, pilot programs with Return on Investment (ROI) evaluation and expanding mobile access to frontline workers.

Innovative solutions

A sustained transformation roadmap requires coordinated action across organizational, technological and cultural dimensions. Innovative approaches include developing user-friendly mobile tools to support operations, implementing digital twins for simulation-based learning and using sandboxes for fail-safe experimentation. Establishing standards for digital resilience and interoperability is critical to ensure that systems can adapt, integrate and grow over time. AI adoption, when guided by operational goals and supported by clean data, offers promising efficiency gains.

Barriers to implementation

Despite progress, many utilities face systemic barriers: lack of funding for change management, over-reliance on vendor-driven solutions, limited technical capacity among field workers and absence of shared data governance models. Cybersecurity concerns – especially around common data environments, cloud platforms and wireless sensors – can delay adoption. Additionally, the legacy software systems used by many utilities are unsuited for cloud applications, and updates are typically modifications to software structures that are not adaptable to cloud-based applications. Utilities also hesitate to adopt AI or digital twins without a clear understanding of their ROI or risk profile. Without frameworks for pilot testing, knowledge transfer and collaborative platforms, utilities struggle to scale success.

Strategic pathways

To safeguard public health and ensure operational continuity, utilities must embed cybersecurity into every stage of digital transformation. Defense-in-depth strategies – layered firewalls, multifactor authentication, backup systems and secure communication protocols – should be coupled with workforce training. Guidelines for utility-level data governance, AI responsibility and secure cloud use are essential. National efforts should focus on creating flexible templates for digital business plans, sector-wide ROI benchmarks and integrated digital resilience assessments. Building from frontline engagement and clear operational missions, digital transformation in the water sector can become a sustainable, inclusive and secure path forward. Lastly, the importance of establishing frameworks and processes for selecting, testing and implementing new technologies was also mentioned.

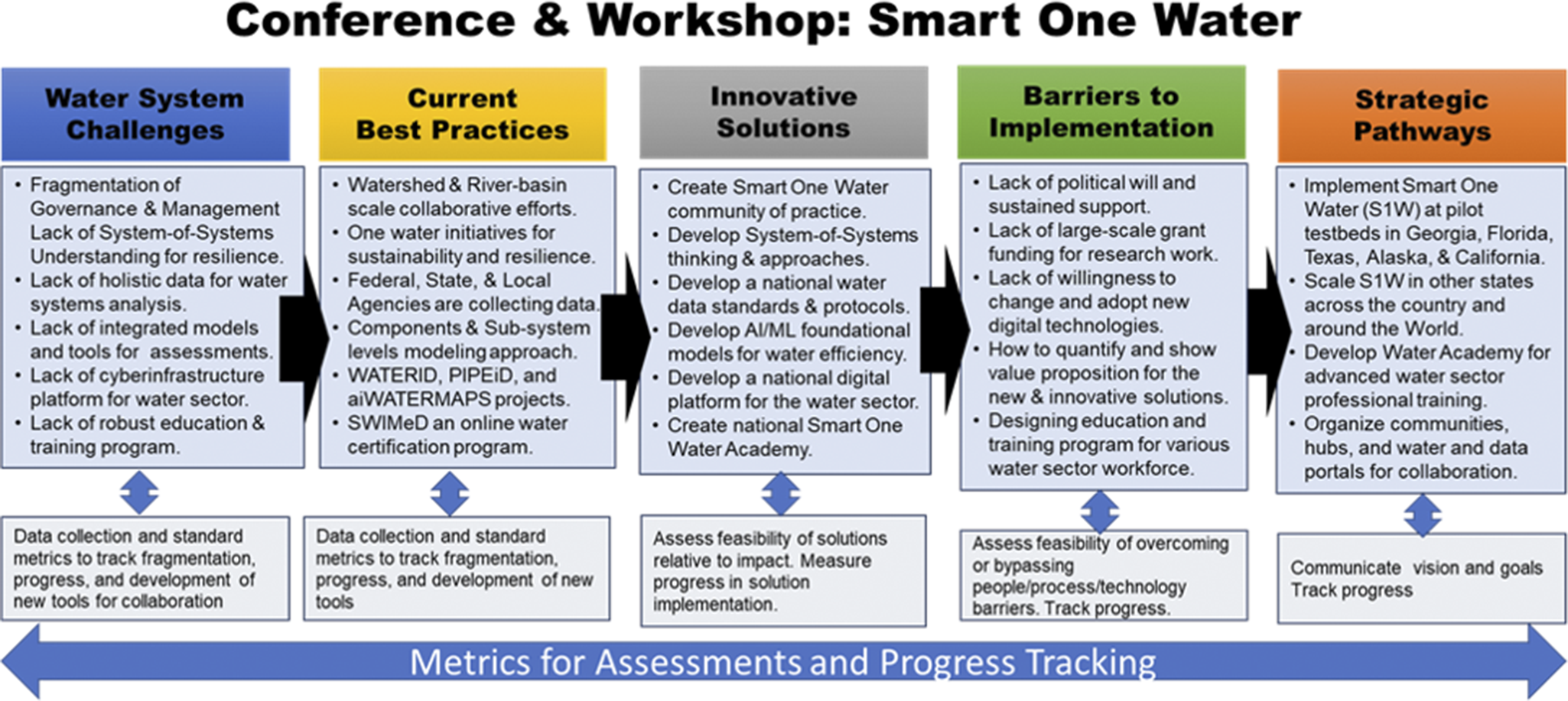

Key takeaways from the SWIM 2024 conference and workshop

Overall outcomes

The SWIM 2024 conference and workshop confirmed that there is an urgent need for a new water sector governance and management model. The authors believe that a participatory and collaborative approach to co-producing and implementing S1W, an approach built on a culture of inclusion, diversity and community engagement, is the only way to create an innovation ecosystem that can deal with the complex set of contemporary and future water sector management and governance challenges across the country and the world. Motivational and keynote speakers provided high-level ideas and overarching topics to consider for water sector governance and management. Six panel sessions were followed by a workshop that all served to identify possible solutions and approaches to meet critical water challenges, research needs and issues while aiming for just and equitable water systems for all. The insights gained are synthesized in Figure 12. Recommendations spanned a range from broad principles and missions to be adopted by various participating programs and their initiatives on actions for communities and their water management and governance activities across the country and around the globe. The five boxes – Challenges, Current Best Practice, Innovative Solutions, Barriers to Implementation and Strategic Pathways – capture the evolving system-wide needs and solutions. Below, some metrics are noted to guide the assessment and tracking of progress.

Figure 12. Overall outcomes from Conference and Workshop Smart One Water.

Water system challenges

Currently, water systems have fragmented governance and management, especially at the regional and watershed levels. There is a clear lack of water SoS understanding by water professionals. This includes an understanding of the potential threats and stresses posed by climate, land-use and socioeconomic changes. The lack of SoS understanding is accompanied by a paucity of holistic data for water systems analysis, a lack of integrated models and assessment tools and inadequate cyberinfrastructure and educational and workforce-development programs. Holistic data collection and the development of standardized metrics need to be used to track progress. And the development of utility/university collaborations and partnerships could potentially create new opportunities and a much-needed paradigm shift.

Current best practices

The current best practices include watershed and river-basin collaborations, a few initiatives promoting the “one-water” paradigm, some data collection efforts from Federal, State and Local Agencies; successful projects like WATERID (2025), PIPEID (2025), aiWATERS (WRF Report 4797) (2025); and certification programs like SWIMeD (2025). Data collection and standard metrics can help track progress and the development of new tools. We introduced the aiWATERS project developed by the SWIM Center, USGS, ORNL and water utility and State water agency stakeholders (especially in GA, CA, TX and OR) earlier in this paper. While evolving rapidly, the aiWATERMAPS (2025) project is already demonstrating the governance, management, operational and financial efficiencies that could be potentially achieved through an S1W-inspired, data-informed, AI-enabled, source-to-tap, integrated framework and knowledge platform.

Innovative solutions

Emerging approaches include creating a S1W community of practice, developing a SoS thinking, creating nationally consistent water data standards and protocols, leveraging new technological advances by creating AI/Machine Learning (ML) models for the water sector, developing a digital platform at the national level and creating a national Smart One Water Academy. Progress can be tracked by assessing the feasibility of different candidate solutions and the advancement in implementing solution strategies.

Barriers to implementation

While the needs are well-understood and there is a clear vision on how to bring innovative solutions, there are significant barriers to successful and practical implementation. There is a lack of political will and sustained support, including large-scale grant funding for research. Water utilities are also, understandably, sometimes slow or unwilling to change and adopt new technologies. Any changes and poorly understood or untested technologies involve new exposures to uncertainties and consequent risks. At the same time, questions remain on how to quantify and convincingly demonstrate the value proposition of the new digital solutions, and there is a need for new education and training programs to bring digital solutions to fruition. Progress could be tracked by an ongoing assessment of the feasibility of overcoming these barriers.

Strategic pathways

The SWIM 2024 conference and workshop identified four key strategic pathways to address the challenges of the water systems breaking through the existing barriers. They are:

-

1) Implement the S1W at pilot testbeds in Georgia, Florida, Texas, Alaska and California, which are distinct and provide unique opportunities to work out solutions for different jurisdictions;

-

2) Scale S1W to other states across the country (and beyond);

-

3) Develop a Smart One Water Academy to train and support professionals;

-

4) Organize communities, hubs and water/data sharing portals.

Conclusions and future directions

The critical water issues and challenges addressed by the 2024 SWIM conference and workshop (through its suggested solutions) reflect worldwide concerns relating to governance, management and accessibility to safe drinking water and to wastewater treatment systems. A World Health Organization report (WHO, 2021) estimated that, in 2020, two billion people (about one in four) around the world lacked access to safely managed drinking water services. More recent modeling (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Lauber, van den Hoogen, Donmez, Bain, Johnston, Crowther and Julian2024) using a combination of on-the-ground household survey data for low- to middle-income countries and earth observations geospatial data finds that an estimated 4.4 billion people lack safely managed drinking water services. Nonetheless, as mentioned by Hope (Reference Hope2024) in his perspective summary of Greenwood et al. (Reference Greenwood, Lauber, van den Hoogen, Donmez, Bain, Johnston, Crowther and Julian2024), progress has been made, in some countries, in the provision of safe water. Government investments in India, for example, have resulted in a major increase in household water taps from 16% in 2019 to 77% in 2023. Improved water system monitoring and assessments of water delivery services support the attention and investments of water policymakers and funding entities: data and attention to data are key.

The SWIM 2024 conference and workshop findings and recommendations, focusing largely on water systems in the United States, support the importance of access to quality water data – but go beyond that by considering the need to bring together, integrate, communicate, share and enable the use of available water SOS data and knowledge, now and into the future, in a just and equitable way. Digital technologies and AI tools are essential to this effort, and so are innovative governance, policymaking and business models that control water provisioning services.

Water data and knowledge need to be integrated from “source to tap,” and decision-making and investments need to consider not only the immediate needs of communities, but also their longer-term needs, as well as the resilience of the water SOS (including NBSW systems) in the face of dynamically evolving stressors (incl. Climate change, land-use change and socioeconomic change). What does this mean in practice? It means that even in higher-income countries like the United States, fragmentation of water knowledge, water operations and water investments is a major, largely unaddressed problem. Adherence to past legacies and institutionalized practices, largely stove-piped into three separate systems of interest (natural water provision, built water treatment and delivery and socioeconomic water uses), is for the most part designed to face the water problems of the past, rather than the water problems of the present and of the future. Water SOS failures (e.g., Flint, MI; Jackson, MI; CRB over-allocation) keep occurring at a systems level. Responses are largely reactive and parsed out (when even feasible) to meet the immediate crisis. Anticipatory planning, adaptive management and governance are lacking. There is a paucity of creative, integrative, yet practical thinking and decision-making needed to address present water and future challenges.

So, did the SWIM conference and workshop – with its focus on “sustainable and resilient water future for all in an ever-changing environment” – change this state of affairs? No, a much greater and longer effort is needed. Nonetheless, we (the authors and participants) believe that it suggested important recommendations to improve the governance and management of water in the United States. The S1W vision provides an important framework and integrative conceptualization that goes beyond previous integration efforts (such as IWRM). S1W also leverages new technologies and modeling to improve data and knowledge integration and identification of gaps and quality issues. The major recommendations of the conference (mentioned in the previous section) are part of a larger effort by the SWIM community of practice to create a roadmap for further progress, not only for the United States but also for other countries.

The next SWIM conference scheduled for December 2025 has been designed to suggest possible pathways for practical solutions implementation. The SWIM community of practice – collaborating with water utilities and with the US Geological Survey and other partners in academia, the private sector and government agencies at the national, state and local levels – has started a major project and knowledge and technology platform, aiWATERS. The aiWATERS platform and approach aim to improve efficiency and resilience of drinking water provision, delivery and use (across the NBSW systems). The project started in Georgia, where it has had a major state-wide impact and attracted national attention (AP Article, 2024). Other states are now actively participating (e.g., Alaska, California, Georgia, Florida and Texas) or have expressed interest (e.g., Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York). Momentum is being built, nationally and internationally, toward the establishment of a widely accessible digital water platform offering access to data, modern technologies and tools (including AI and Digital Twin modeling), guidelines and standards for assessments and a knowledge base for enabling comparisons of situational contexts and for advancing development of best practices and innovation. At the international level, the S1W vision and approach and the SWIM community of practice are also working on a project to improve the resilience of water systems management, operations, planning and community and stakeholder engagement in India with the help of a United States Agency for International Development-funded project.