Introduction

This article offers a new history of the Afrogothic, which extends the genre beyond histories of Black enslavement, by routing it instead through the traditions of the Black esoteric and Black surrealism. Important work in the past several decades on African American literature and the Gothic tradition has tended to link them by reference to histories of slavery. Teresa Goddu, for example, has suggested that the “scene of slavery was often represented as Gothic during the antebellum period in America,” and beginning with Richard Wright’s connecting of the Gothic with the African American experience in his introduction to Native Son (1940), Goddu demonstrates how slavery and the Gothic are deeply connected in American and African American literature.Footnote 1 Later, Maisha Wester built on the work of Goddu by observing that Afrogothic “constructions present a complex problem for minority authors who use the Gothic as a vehicle for enunciating the real terrors of racialised existence.”Footnote 2 Wester suggests that Black authors have used these “terrors of racialised existence” to critique the Black experience in America; she has also most recently explored a Black Lives Matter Gothic, which “centres upon a racially targeted violence that defies rational explanation.”Footnote 3 Additionally, in a 2018 Los Angeles Review of Books article, Sheri-Marie Harrison identifies a “New Black Gothic” trend that she sees in contemporary Black art and literature in which “there is no buried trauma that must be converted into language for its victims to move on. Instead, racial violence has never gone away. It is indeed, as the ghosts are, at home with us.”Footnote 4 My article, however, moves away from focussing specifically on the trauma of slavery, and takes as its starting point Sybil Newton Cooksey and Tashima Thomas’s identification of the Afrogothic, in a recent special issue on the genre, as “a ‘process’ and ‘distinctive set of aesthetic strategies’ that take a necessarily indirect or allegorical approach to reckoning with slavery – or … its afterlives.”Footnote 5 Ultimately, I suggest here that the Afrogothic is not always an expression of despair, but can also and alternately be an expression of transcendence.

Bishop Richard Hurd, one of the first theoreticians of the Gothic, used the term “terrible sublime” in 1762 to describe the Gothic romances of Shakespeare, a sublimity that, Carol Margaret Davison argues, “evokes awe, delight and terror in its threat – either direct or indirect, or overwhelming power with its two primary possible outcomes: the desirable possibility of self-transcendence and the dreadful possibility of self-annihilation.”Footnote 6 The Afrogothic, as I explore it here, is similarly concerned with the “terrible sublime” and the possibility of “self-transcendence.” Through mapping a new history of the genre’s evolution, I trace these concerns in Black Gothic writing back to African ur-texts such as the Egyptian Book of the Dead. This Gothic writing is integral to a Black esoteric tradition that finds modernist expression in the work of the Harlem Renaissance writers, and a surrealist postmodern expression in the work of American avant-garde poets via the blues. As such, my rethinking of the Afrogothic resonates with filmmaker Arthur Jafa’s understanding of the “abject sublime” as an essential component of Black expression. In the special issue referenced above, Cooksey, writing on Black danse macabre, or Black dances with Death, quotes Jafa at length:

“So the abject sublime to me is just basically a codification of this idea,” he says, “that inside of the black worldview, black being, the black continuum, it’s impossible to completely separate out what’s magnificent about it and what’s miserable about it. Like, they’re intrinsically bound up.Footnote 7

Through retheorizing and rehistoricizing the Afrogothic, I examine how Black writers developed an Afrogothic aesthetic that not only was deeply in tune with this concept of the terrible sublime, but also supplied a surrealistic aesthetic basis that would inform Black experimental writings in the early and mid-twentieth century. In order to understand the Afrogothic, we need to attend to its surrealist components, which are made visible – as I will presently argue – in the blues aesthetic held in common by both.Footnote 8 Afrogothicism, Afrosurrealism and blues aesthetics reinforce one another in the explorations of sublimity produced by Black Americans in the aftermath of the Harlem Renaissance, and would even go on to influence the better-known white avant-garde writers of the era. This is to say that the Afrogothic aesthetic that I explore here is deeply connected to the blues aesthetic that one sees in a Black literary tradition that, as Jeffrey Ferguson notes, one can trace from Langston Hughes to Toni Morrison to Paul Beatty. Ferguson sees this tradition as problematic in that “blues aesthetic criticism tends to reference the blues as a general sensibility or as an abstract ‘matrix’ of values, concepts, and emotions that define black American cultural practice in general and ground black American literature in the world-making philosophy, linguistic practices, and musical traditions of ordinary blacks.”Footnote 9 In this paper, by demonstrating the relationship that blues has with other aesthetic cultural forms like the Spanish duende, I argue that this “matrix of values” is actually of deep cultural significance to a people who have had their cultural products devalued by the culture at large, and whose cultural products are enlivened by the constant threat and presence of death.

In the following pages, then, I argue that this blues aesthetic and its literary tradition reveal an Afrogothic sensibility that can be traced not only forward to authors like Paul Beatty, but also backwards to what Isiah Lavender III calls “a literary prehistory,” or literary works that inform a tradition that doesn’t yet have a name.Footnote 10 This is to say that the way we read Black writers in the blues tradition changes when we think of them as also engaging with an Afrogothic sensibility of sublime transcendence. This perspective establishes an important connection between the blues writers of the Harlem Renaissance and the bebop writers that pre-dated and developed into the Black Arts Movement. To demonstrate this, I will use two authors as case studies: the first is Jean Toomer, who wrote within the formation we now call the Harlem Renaissance, and the second is the Black bohemian poet Bob Kaufman, often considered a beat poet and influential figure for the development of American postwar avant-garde poetry. Toomer is useful as a representative from the Harlem Renaissance because his book Cane (1923) pre-dates most of the other novels associated with the Harlem Renaissance and thus can be said on some level to have influenced them, and Kaufman is useful because his “bebop bluesgoth” aesthetic, as I define it, evokes the duende theory of Lorca, whose connection to the Harlem Renaissance, as will be demonstrated here, suggests that there was a spiritual or aesthetic coherence between these artists that, I argue, is this very spirit of the terrible sublime.

Origins of the Afrogothic

The Gothic is allied with the surreal in that both are interested in what lies beneath the surface. Thus discussions of the Afrogothic go hand in hand with discussions of Afrosurrealism. Afrosurrealism, a term coined by D. Scot Miller in a special issue of the San Francisco Bay Guardian in 2009, “presupposes that beyond this visible world, there is an invisible world striving to manifest, and it is our job to uncover it. Like the African Surrealists, Afro-Surrealists recognize that nature (including human nature) generates more surreal experiences than any other process could hope to produce.”Footnote 11 Also in 2009, Franklin Rosemont and Robin D. Kelley published Black, Brown & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora, a book that explored the history and development of Black surrealism as an aesthetic and political movement. Rosemont and Kelley argue that Black surrealism begins in 1932 with Etienne Léro, a poet and philosopher from Martinique, who was living in Paris at the time. Léro would bring a group of young people together that year under the name Légitime Défense (“self-defense”), and start a surrealist journal with the same name, a journal in which “twenty-four pages covered an astonishing range of material: a hot mix of surrealist manifesto, poetry, revolutionary theory, and sharp criticism of the Antillean bourgeoisie, its docile politics and complacent culture.”Footnote 12 Thus Black surrealism was interested in doing a deep dive into the Black subconscious in order to reveal the real beyond what we see in the everyday. As Amiri Baraka put it, “I was always interested in Surrealism and Expressionism, and I think the reason was to really try to get below the surface of things.”Footnote 13

This process of diving into the Black subconscious can also be seen in Richard Wright’s work. Wright was, as James Smethurst demonstrates, deeply interested in the Afrogothic, not only in relation to the history of slavery, but also as a confluence of surrealism and the blues.Footnote 14 In his essay “Memories of my Grandmother,” he writes

The manner in which Negro blues songs juxtapose unrelated images … was the advent of surrealism on the American scene. I know, of course, that to mention surrealism in terms of Negro life in America will strike some people like trying to mix oil and water; but the two things are not so widely separated as one might suppose at first.Footnote 15

For Wright, surrealism is not just deeply embedded in the blues and Black culture. Rather, American culture in general gets its sense of the surreal from the blues and from Black culture. Wright’s contemporary, the novelist Chester Himes, made a similar point when he said, “It just so happens that in the lives of black people, there are so many absurd situations made that way by racism, that black life could sometimes be described as surrealistic. The best expression of surrealism by black people, themselves, is probably achieved by blues musicians.”Footnote 16 Both Wright and Himes echo statements made by the surrealist Negritude author Aimé Césaire, who wrote that, for him, surrealism was “more of a confirmation than a revelation … if we plumb the depths, then what we will find is fundamentally black.” Surrealism for Césaire is “a process of disalienation,” which is to suggest that the existential condition of feeling fundamentally alienated from society that informed so much of American and European modernism’s aesthetics was the constant and ongoing condition experienced on a daily, concrete basis by members of the Black diaspora, in their relationship with the West.Footnote 17

One of the problems that arises in attempting to define the Afrogothic is the difficulty of defining what Gothic itself refers to. A good place to start is Horace Walpole’s novel The Castle of Otranto (1764), often considered the first English Gothic novel. The association between the crumbling, medieval castle, the uncanny and the horrific all come to be associated with Gothicism, and generally the Gothic has also been associated with Eurocentrism.Footnote 18 However, one of the bolder moves that Cooksey and Thomas make in their special issue of Liquid Blackness is to challenge the assumption that the Gothic belongs in Europe. In a fascinating roundtable discussion between Cooksey, Thomas, authors Leila Taylor and Lea Anderson, graphic novelist John Jennings and musician Paul Miller (aka DJ Spooky), the participants interrogate this idea, coming to the conclusion that “the definition of Gothic is expanding a lot beyond the traditional Eurocentric or British point of view. It’s a sensibility that can be applied to anyone. Every culture has its ghost stories, its own cultural traumas to work through somehow.”Footnote 19

It may be productive, then, to consider the origins of the Afrogothic as forming in ancient Egyptian religion, especially if one thinks of Egypt as a kind of “African Zion” that has captured the Black diasporic imagination, as Eric Sundquist argues.Footnote 20 For example, The Egyptian Book of the Dead acts as “a kind of passport to the afterlife” that describes “a journey from death and burial to the darkest caverns and to the eternal stars, and on the way the dead enter fiery pits, confront snakes and flesh-eaters; they meet ferrymen and gods and kings.”Footnote 21 Here, the terrible and the sublime are deeply connected; just as Jafa’s “abject sublime” is a dance with death, and just as Dante must first journey through the Inferno to reach Paradise, it is impossible to achieve the sublime without the experience of the terrible. Read as a kind of Black spiritual ancient text, The Egyptian Book of the Dead imagines a transcendent future that first requires acknowledgement of the horrific. With the introduction of the transatlantic slave trade, members of the African diaspora, in their dealings with the Western world, and with the beginnings of a modern, globalized world, would also be subjected to a kind of living death, in which the future would have to be completely reimagined within the framework of having come out on the other side of a lived terror. Moreover, if the attributes normally associated with the Gothic, namely darkness, barbarism and Dionysian madness, are often also associated with physical Blackness, then the Gothic and physical Blackness must also be understood as conceptually related. As Toni Morrison notes in Playing in the Dark, whiteness and Blackness always appear together in American literature, because “these images of blinding whiteness seem to function as both antidote for and meditation on the shadow that is companion to this whiteness – a dark and abiding presence that moves the hearts and texts of American literature.”Footnote 22 Consider, for example, the racialized horror of Blackness in Edgar Allen Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, in which the Gothic island of Tsalal is inhabited by a race of Black people who have no concept of whiteness whatsoever, or the Gothic horror of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, where a trip into the subconscious is quite literally a descent into Blackness and “barbarism,” a loaded word if there ever was one.

Thus the Gothic, as understood within the framework of the Western imagination, has also to be understood in connection with the concept of Blackness, and it comes as no surprise that the first Gothic novel, Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, was published in 1764, just as the transatlantic slave trade was reaching its peak. Reimagined through Black ingenuity, however, the living dead of the transatlantic slave trade were able to turn what were called the “Blue Devils” into the blues. The transition from the blue devils to the blues is worth exploring further. As Peter C. Muir writes in his study of blues music, around

the beginning of the seventeenth century, the concept arose of a “blue devil” (earliest known reference 1616), originally a malignant demon, which, in the plural form, later acquired a metaphorical meaning of despondency … By the middle of the eighteenth century, “blue devils” was being shortened to “blues” or “the blues”.Footnote 23

The blues, however, or these “blue devils” as reimagined by Black people in blues music, is not an expression of despair; on the contrary, it is the very essence of Afrogothicism as I am reading it here: it is the terrible sublime. As Albert Murray writes in his indispensable text Stomping the Blues, the blues is a means of expurgating “the blue devils of gloom,” and “the Saturday Night Function also consists of rituals of resilience and perseverance through improvisation in the face of capricious disjuncture.”Footnote 24

The blues themselves, then, are allied to the Afrogothic in the sense that they are an expression of the terrible sublime. This blues aesthetic became a starting point for modern and modernist African American literature, especially with the literary innovations of the Harlem Renaissance, and so in the following section I will demonstrate how the blues-influenced Afrogothic made its appearance in the modernist novels of the Harlem Renaissance, especially in the work of Jean Toomer.

The emergence of the Afrogothic novel in the Harlem Renaissance

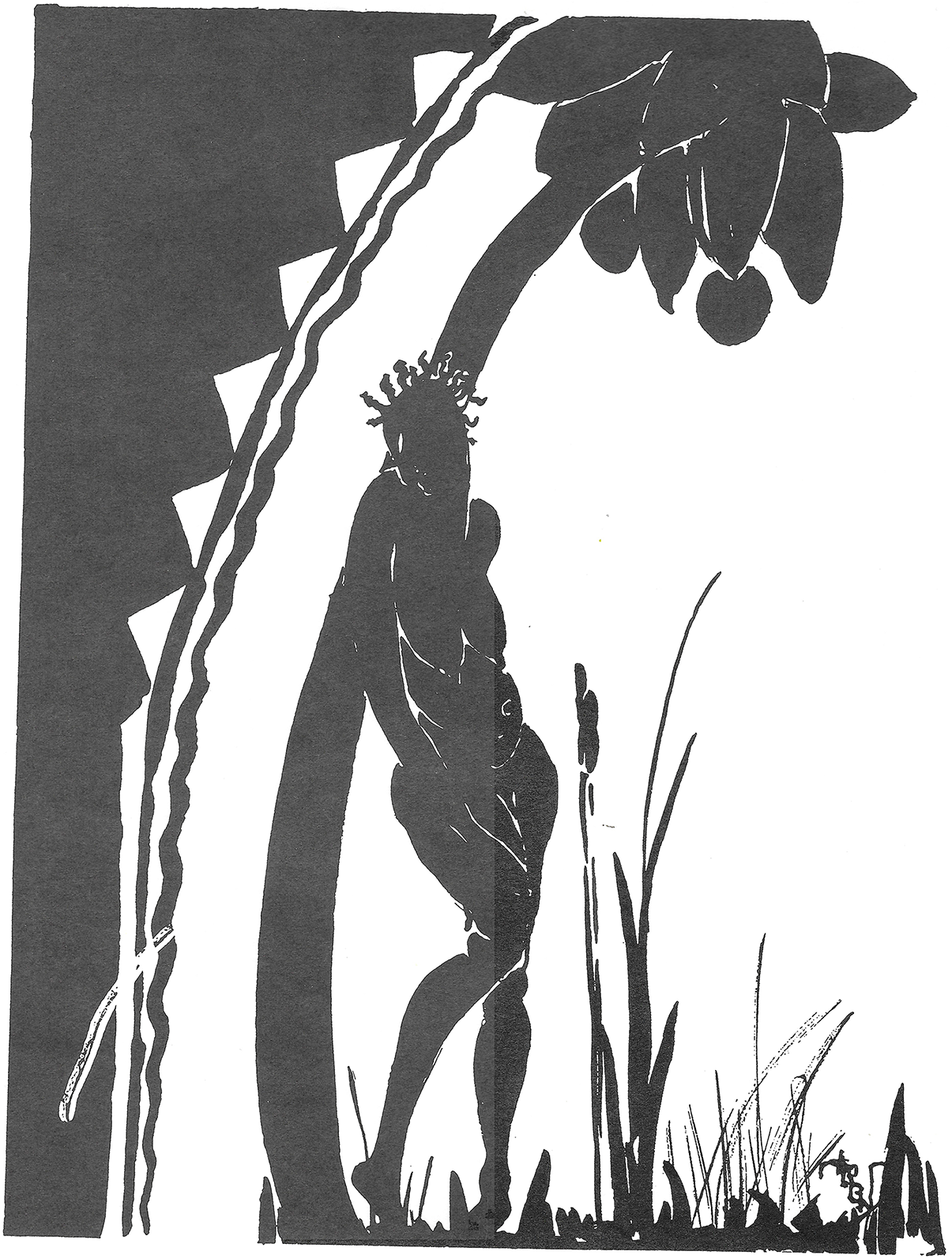

Scholars of the Harlem Renaissance have not fully investigated how several of the movement’s most important novels might be described as New York Afrogothic, particularly Wallace Thurman’s Infants of the Spring (1932), Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem (1932), and Rudolph Fisher’s The Walls of Jericho (1928). These novels use Gothic tropes and modes of expression to explore the lives of writers and artists in Harlem’s counterculture, people in the precarious position of being Black, broke, and queer – in terms of sex and gender, and more broadly. Thurman’s novel, for example, is a roman à clef about life at “Niggerati Manor,” and the artists who lived there and participated in a salon known as the “Dark Tower.” Both of these names evoke the Gothic castles stereotypically associated with European Gothicism. The novel centers around two characters, Ramond Taylor and Paul Arbian, respectively stand-ins for Wallace Thurman himself and his roommate, Richard Bruce Nugent, the first openly gay Black American writer. At the very opening of the novel, Thurman establishes the Gothic atmosphere of “Niggerati Manor” by alerting the reader to “the red and black draperies, the red and black bed cover, the crimson wicker chairs, the riotous hook rugs, and Paul’s erotic drawings.”Footnote 25 It is fair to say that these erotic drawings were not just standard erotica, but would have included non-traditional erotica as well, and one thinks of the erotic drawings of Richard Nugent himself, which are often Gothic in their stark black-and-white chiaroscuro (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Richard Bruce Nugent, “Drawing.” Fire!!, 1, 1 (1925), 4.

Tellingly, the novel also ends with the suicide of Paul, which Thurman describes using deeply Gothic imagery and the same red and black color scheme, with the contrast of Paul’s Black body “crumpled at the bottom, a colorful inanimate corpse in a crimson streaked tub.”Footnote 26 Thurman completes the novel by suggesting an additional great tragedy of Paul’s suicide is that Paul’s potential masterpiece, which he hopes will be posthumously published, becomes waterlogged and illegible in the process. All that is salvageable from the manuscript is the cover page and dedication, which contains a drawing that turns “Niggeratti Manor” into a proper Gothic castle: “Beneath this inscription, he had drawn a distorted inky black skyscraper, modeled after Niggeratti Manor, and on which were focused an array of blindingly white beams of light. The foundation of this building was composed of crumbling stone.”Footnote 27

At the time of writing his novel, Thurman was deeply influenced by the Armenian mystic G. I. Gurdjieff, and he was exploring new ways of writing that were inspired by the Gothic eeriness of Jean Toomer’s book Cane, a profound work of southern Gothicism that is also infused with Gurdjieffian philosophy.Footnote 28 Charles Scruggs and Lee VanDemarr have written on how Cane uses both the detective story genre and the Gothic novel as backdrop.Footnote 29 They see Cane as a work of southern Gothic in which lynching plays the role of the buried secret of the hearth that gives a horrible and frightening undertone to the atmosphere. “Gothicism in Cane,” they write, “depends for its effects on the hidden past erupting into the present, upsetting the social order, and raising questions about good and evil that conventional morality cannot answer. In the post-Reconstruction South, that morality revolved around the issue of black–white relationships and especially the ‘moral’ issue of lynching.”Footnote 30 Ultimately, they argue, the presence of lynching in the post-Reconstruction South gave the lie to claims of American morality, spirituality, or exceptionalism. Similarly, Maisha Wester sees in Cane an emphasis on both “the seemingly permanent entrapment black bodies face in a racialized environment and the absolute horrors of intraracial betrayal, often made synonymous with interracial violence.”Footnote 31 Indeed, Cane is a violent book, and if the southern practice of lynching haunts the text, for Toomer the terrible sublimity of possible spiritual transcendence is the means to salvation. Cane explores this Gothic sublimity through Kabnis, the Black northern intellectual who attempts to come to terms and be at peace with the American South in the third part of the book, which bears his name. Spenser Simrill, in his article on reading this third section “Kabnis” as a mystical text, points out that the text blends both Islamic mysticism and Jewish mysticism, beginning with Kabnis’s name, and he argues that the character of Father John, a former slave and town preacher, who is “the essence and forefather of black spirituality, an Abraham for African Americans,” operates in the text as Kabnis’s “transcendent self.”Footnote 32 Simrill argues that the third section of “Kabnis” only makes sense when read as a work of Black mysticism, which is why the section has confused so many of its readers, right down to W. E. B. Du Bois.Footnote 33 It is Afrogothicism as possible transcendence instead of Afrogothicism as repressed horror.

For Toomer, the Afrogothic horror of lynching is thus contrasted with the Afrogothic possibility of achieving the transcendent sublime via Black mysticism; it is for this reason that the entire text of Cane seems to be both haunted and spellbound at the same time. For example, the first part of the book begins in the South, and it ends with the southern Gothic lynching fable, “Blood-Burning Moon,” which announces its mystical Gothic atmosphere in the opening paragraph:

Up from the skeleton stone walls, up from the rotting floorboards and the solid hand-hewn beams of oak of the pre-war cotton factory, dusk came. Up from the dusk the full moon came. Glowing like a fired pine-knot, it illuminated the great door and soft showered the Negro shanties aligned along the single street of factory town. The full moon in the great door was an omen. Negro women improvised songs against its spell.Footnote 34

In a remarkable couple of sentences Toomer establishes a Black Gothic southern aesthetic that evokes slavery (“pre-war cotton factory”), lynching/burning (“fired pine-knot”), the Black hearth (“Negro shanties”) and Black magic (“songs against its spell”). This story, which introduces Bob Stone, who is white, and Tom Burwell, who is Black, is a classic doomed love triangle. Both men are in love with a Black woman named Louise, or rather Tom loves Louise, and Bob feels possessive of her, nostalgic for the antebellum days when he would have been able to rape Louise with impunity. He decides that he will rape her anyway. When he goes to do so, he discovers that she is with Tom. The two engage in a scuffle, which results in Tom cutting Bob’s throat. Bob alerts the town that Tom was the one who dealt him the fatal blow, and the townspeople come and take Tom and burn him alive. It reads like a southern Gothic fable, and it is very much a lynching story, even though the method of execution in this case is burning. Toomer’s great accomplishment with “Blood-Burning Moon,” then, is to take this trope and turn it into something of a Black horror story, that in its awful familiarity, and in its focus on a “single event” (Einzelerlebnis) takes on the aspect of a legend, as defined by Max Lüthi, or a story that, first, is meant to be believable, and second, has, in its simplicity, the possibility of being communicated orally.Footnote 35 In its southern Gothicism, the novel also evokes the blues. As Benjamin McKeever notes in his article “Cane as Blues,” Georgia itself is the blood-burning moon of the first section, and Georgia is the blues as well. McKeever explains it through reference to Ralph Ellison, quoting Shadow and Act: “the blues is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain and transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.”Footnote 36 McKeever then goes on to argue, “What Ellison says about the blues is an appropriate description of Cane,” namely that it is “an autobiographical chronicle of personal catastrophe expressed lyrically.”Footnote 37 McKeever reads Cane as a series of blues expressions from the various women who appear in the first part, the northward migration of the blues that will characterize the second part and then the blues of Kabnis that occupies the third part of the text.

In Cane, the blues is on the move; the location may change, but the blues travel along. In the second part of the text, where Cane extends its southern Gothicism to the mid-Atlantic city of Washington, DC, the Gothic language remains. Seventh Street, we read, “is a bastard of Prohibition and the War. A crude-boned, soft-skinned wedge of nigger life breathing its loafer air, jazz songs and love, thrusting unconscious rhythms, black reddish blood into the white and whitewashed wood of Washington. Stale, soggy wood of Washington Wedges rust in soggy wood.”Footnote 38 The alliteration here recalls Poe’s lines from “Ulalume”: “It was down by the dank tarn of Auber, / In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.”Footnote 39 By moving his vision beyond the South and recontextualizing it within a city that sits somewhere between the North and the South, just under the Mason–Dixon line, Toomer expands his vision beyond the confines of the South, and his blues begins its Great Migration north. The second part of the text ends with a long story, “Bona and Paul,” which moves the hearth to Chicago, thus putting the reader squarely in the urban North. This story, which focusses on the relationship between Paul, a multiracial man who in some ways can be read as a stand-in for Toomer himself, and Bona, a white woman, is a classic tale of thwarted interracial love. In fact, it makes a striking parallel with “Blood-Burning Moon,” the southern Gothic fable which closes the first part. While “Blood-Burning Moon” concerns two men, one white and one Black, who both desire the same Black woman, “Bona and Paul” makes the drama of interracial love one in which internalized racism prevents the couple from coming together, as opposed to the possessive toxicity of white supremacy, as presented in “Blood-Burning Moon.” Paul and Bona are set up by Paul’s friend Art; and the four of them go out together on a double date; meanwhile Paul, conflicted about how he is perceived by white America, or caught in the grip of a Du Boisian double consciousness, begins to feel uneasy: a “strange thing happened to Paul. Suddenly he knew that he was apart from the people around him. Apart from the pain which they had unconsciously caused. Suddenly he knew that people saw, not attractiveness in his dark skin, but difference.”Footnote 40 This realization ruins the possibility of Paul ever feeling comfortable anywhere. In the final moments of the story, as he leaves the club with Bona, and sees the expression in the Black bouncer’s face, he feels the need to go back and explain himself – in a sense to explain the way that he is haunted – insisting that he will go “out and know her whom I brought here with me to these Gardens which are purple like a bed of roses would be at dusk.”Footnote 41

Of course, Bona is gone by the time Paul reemerges into the night to find her. His haunted mind hangs in the balance of the terrible sublime. He feels that his double consciousness will allow him to transcend the racialized thinking which surrounds and infects him and his companions, but at the same time remains conscious of the haunted quality of his thought. “The hidden past erupting into the present” prevents him from achieving the sublimity of transcendence he seeks and lands him back in the Gothic horror of a deeply racialized America.

Cane cannot really be considered a traditional novel, nor is it just a collection of stories and poems. It becomes, like Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk, a unique collection of literary sketches that forms a whole and reimagines the genre of the long prose Gothic in a new form, just as Du Bois’s text reimagined the possibilities for Black sociological studies. In a sense, Cane’s triumph is in establishing an Afrogothic vision which spans both poetry and prose, the novel, the short narrative and the dramatic form, which Toomer explores in Part Three of Cane. For Toomer, the Afrogothic is a genre which spans all three of these forms – the narrative, the poem and drama – and Cane suggests that the difference between the forms is not so great when considered in terms of a blues-inflected Afrogothicism; and just as the blues influenced bebop, the Harlem Renaissance’s blues-inflected texts would go on to influence the postwar poets who looked to bebop as a fellow traveler to their aesthetic visions, while tapping into the Afrogothic through their use of the surreal, as will be demonstrated in the following section.

Bob Kaufman and the legacy of Afrogothic poetry

Black poets would go on to tap into bebop’s energy in the years following the Harlem Renaissance, although much of this history is unfortunately buried. As Melba Joyce Boyd writes, between 1945 and 1965 “only thirty-five poetry books authored by African Americans were published in the United States, and only nine of those were published by presses with national distribution.”Footnote 42 In the formative years of bebop-influenced poetry, Black poets disseminated their works outside the infrastructures of the commercial literary book trade, either because they were prevented from accessing them or because they preferred to explore nontraditional modes of dissemination and publication outside the book form. Nonetheless, the poets were there. Dudley Randall, Big Brown, Bob Kaufman, Ted Joans and Amiri Baraka, to name just a few, were all practicing poets at the time, and all of their work was inspired by new directions in jazz and the blues; in some sense they were even victims of their own anti-establishment aesthetic in that in their refusal to pursue recognition by the white world, they were often too easily ignored by a literary world only too happy to oblige them. It would be counterculturally minded white authors who would seize on this aesthetic and begin publishing work influenced by bebop. Aldon Nielsen’s Black Chant (1997) has done much to chart this history, and more recently Notes to Make the Sound Come Right: Four Innovators of Jazz Poetry (2004) by T. J. Anderson III and A Black Arts Poetry Machine: Amiri Baraka and the Umbra Poets (2019) by David Grundy have built on Nielsen’s work. In focussing on Bob Kaufman in this section, I seek to further their recovery project, but I also want to argue that Kaufman, like Toomer, is a crucial note in the historical literary networks through which the contemporary Afrogothic is routed. Kaufman’s work uses the blues’ interest in surrealism to develop a poetry that can be called Afrogothic in the way that it evokes the terrible sublime in combination with this blues sensibility, but Kaufman gives his poetry a rhythm more bebop-inspired than blues-inspired, even while invoking the spirit of the blues as an expression of the terrible sublime.

Scholars ranging from Joe Gonzales to Lorenzo Thomas, Aldon Nielsen, Douglas Field and Steven Belletto have all demonstrated that Black poets, and Bob Kaufman in particular, were instrumental in forming the beat poetic aesthetic.Footnote 43 Thus, in examining the work of Bob Kaufman, it is important to note that while the beat writers recognized the spontaneity and free-form rebellion in the jazz and poetry of Black artists, the hidden element of the Black terrible sublime that infused the poetry is often missing in the work of the traditionally recognized white beat writers. Their work often becomes an act of literary appropriation in which something vital has been left out. To echo Langston Hughes, “Yep, you done taken my blues and gone.”Footnote 44 Or as Lorenzo Thomas writes, “Jazz, for Bob Kaufman, suggests … an intense and eerie sadness, a despair for the sanity and survival of all persons,” a sanity and survival which are threatened by the very real threat of dying Black, broke, blue, beat and aesthetically bowdlerized.Footnote 45

The earliest years of Kaufman’s poetry are not well documented, but as early as 1953 there are reports of him reciting poetry on the tables of Vesuvio cafe in North Beach to large crowds.Footnote 46 As his wife Eileen notes in her remembrance of him, “Laughter Sounds Orange at Night,” the Bagel Shop in San Francisco would become a place he was associated with, one where he would often recite his poetry.Footnote 47 The Afrogothic aesthetic that was central to Kaufman’s poetry can be seen in his poem celebrating the Bagel Shop, “Bagel Shop Jazz,” which evokes the scene of the shop and the denizens who inhabit it; the poem evokes a deep sense of the Gothic, with the patrons being cast as “shadow people, projected on coffee-shop walls,” who devour each other (and one thinks especially of them devouring Bob Kaufman and his poetics). This is the Black past made body, a Black spiritualism made beat.Footnote 48

A useful poet for connecting the Harlem Renaissance writers to these mid-century writers is the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. Lorca published his important book of poetry Gypsy Ballads – a book which made him famous, according to Nathanial Mackay – in 1928, and when he travelled to New York in 1929, he would get to meet some of the Harlem Renaissance luminaries. Thus Mackay suggests that the section “The Blacks” of Lorca’s long poem about New York, Poet in New York, was directly influenced by the Harlem Renaissance.Footnote 49 Lorca believed that great Spanish art was possessed with duende, or what he somewhat mysteriously describes in a lecture on the subject as “the hidden spirit of suffering Spain.”Footnote 50 Duende is, for Lorca, a “mysterious power which everyone feels and which no philosopher can explain”; it is the “true living style, of blood, of ancient culture, of the act of creation.”Footnote 51 Lorca’s duende sounds very much like how Murray describes the blues as “rituals of resilience and perseverance through improvisation in the face of capricious disjuncture.”Footnote 52 Duende in fact exemplifies the spirit of the Afrogothic in the way that it evokes the terrible sublime. Lorca writes that the

dark and quivering duende that I am talking about is a descendent of the merry daemon of Socrates, all marble and salt, who angrily scratched his master on the day he drank hemlock; a descendent also of Descartes’ melancholy daemon, small as a green almond, who, tired of lines and circles, went out along the canals to hear the drunken sailors sing.

Quoting Manuel Torres, “a man with more culture in his veins than anybody I have known,” Lorca writes, “All that has dark sounds has duende.”Footnote 53 The Spanish word duende literally translates into “ghost,” or, as Nathanial Mackay puts it on his article on Lorca’s poetic legacy in duende, “the word duende means spirit, a kind of gremlin, a gremlinlike troubling spirit,” and thus it is indeed a special kind of haunting or spirit that inspires the Lorca-esque artist, just as the blues comes from the evocation of the blue devils.Footnote 54 Moreover, Lorca informs his listeners that “the duende doesn’t come if it sees no possibility of death.”Footnote 55 Like the blues, which, as Adam Gussow puts it (referencing Albert Murray) in his study of the existential crisis threatening Black lives that sits at the center of the blues, Seems Like Murder Here (2002), “choosing life when death threatens is … the ethos of the blues essence.”Footnote 56 For both duende and the blues, life and death are inextricably linked, and it is this connection to death that gives the duende and the blues life.

Kaufman was deeply influenced by Lorca and his duende aesthetic. As Mackay notes in his brief analysis of the importance of Lorca to Kaufman’s work, “Kaufman’s apocalyptic, ironically patriotic prose-poem “The Ancient Rain” generously samples, as we would say nowadays, ‘The King of Harlem’ and ‘Standards and Paradise of the Blacks” [by Federico Garcia Lorca].”Footnote 57 Indeed, “The Ancient Rain” can be considered Kaufman’s danse macabre as duende, and Aldon Nielsen notes that Kaufman “found in Lorca’s Duende the black sound of modernism’s future anterior.”Footnote 58 This is to say that, for Kaufman, the future of Black poetry and the sound of Black modernism were already hinted at in the duende of Lorca. Thus the second poem in “The Ancient Rain” is a tribute to Lorca, and when Kaufman writes in this poem, “Give Harlem’s king one spoon,” he is, as noted by Mackay, paying homage to Lorca’s extraordinary poem “El Rey de Harlem” (The King of Harlem), while simultaneously connecting Lorca’s surrealist vision with his own through allusion.

Lorca’s poem, written in 1930, but not published until 1940, four years after Lorca’s death, is itself is a surrealistic journey through the neighborhood of Harlem. Turning Harlem into the unreal landscape that is experienced by the Black Americans colonized there, the political meaning behind Lorca’s poem also fuels Kaufman’s vision, which likewise connects the people of Spain and the Romani people back to Black people. Just as Lorca laments Harlem’s colonization, Kaufman, in “The Ancient Rain”, laments Spain’s “darkened noon,” almost certainly referencing the Fascist Franco dictatorship which was in place from 1939 to 1975.

“The Ancient Rain” is a poem that sinks deep into a blues Afrogothic surrealism funk, or what I earlier identified as Kaufaman’s bebop bluesgoth, in which both the mind and the body have been violated, and this is largely because of the story behind its creation, in which Kaufman, the poet, as human subject, had been subjected to inhumanities that reflected those suffered by his ancestors, Black and Jewish, and which also reflect the terrible sublime: and out of this terrible suffering came the sublime creation of “The Ancient Rain”. Indeed, the story of how this volume came to be collected is the stuff of mythology: In 1963, Kaufman decided to leave New York with his family. His wife Eileen, with their child, had managed to secure a ride all the way cross-country, and as Bob was on his way to meet them, he was arrested in Washington Square Park for walking on the grass during a raid in which the police were cracking down on counterculturalists. His arrest led to his being deemed a problematic person, and as a result he received a series of involuntary electric-shock treatments, from which he never seems to have fully recovered. In fact, the shocks were just the beginning of a deep trauma for Kaufman: A few months later, upon hearing that President Kennedy had been assassinated, Kaufman decided to take a vow of silence that would last from 1963 to 1973; it was during this time that he wrote many of the poems that would comprise The Ancient Rain: Poems 1956–1978, first published in May of 1981.Footnote 59 So in a sense the book contains many of his unvoiced words during his vow of silence. These poems would likely have been lost to posterity if not for the fact that, years after his vow of silence had passed, in autumn 1979, Kaufman was living in North Beach at the Dante hotel when the hotel, somewhat ironically, burned down in a blazing inferno, a story which Raymond Foye, a friend and collaborator of Kaufman’s, tells in a documentary on Kaufman’s life and work.Footnote 60 Ultimately, Foye was able to rescue much of the work that Kaufman, a mostly spoken-word poet, had produced during his vow of silence, and so these poems, born in and out of silence, and the only words from Kaufman during these years, were indeed rescued from the void. “The Ancient Rain” is something unique not only in Kaufman’s own oeuvre, in that it partially spans a period in which no one “heard” anything from Kaufman one way or another, but also because it shows us the work of probably the only American poet to have created a volume of poetry while actively engaged in a vow of silence.

“The Ancient Rain” is such a powerful poetic statement because its Afrogothicism makes explicit the surreal aspect of the blues aesthetic. For example, in “DARKWALKING ENDLESSLY” (from “The Ancient Rain”), Kaufman finds himself haunted by

RAINFALL SEASONS OF THE MIND, PAST THE FOAMING WAVE OF BROKEN INTO AND ENTERED EYES, RIDING BLACK HORSES TO THE THIN LIPS OF THE MIND. IN A YEAR OF BREAKING APRILS, I COME TO THAT PLACE THERE … I WEAVE THE WINDS AND KISS THE RAINS, ALL FOR LOVE.Footnote 61

That this poem is in direct dialogue with the title poem, “The Ancient Rain” itself, is immediately clear, as are many of the poems in this collection. In fact, the poems themselves can be thought of as these ancient rains; and “DARKWALKING ENDLESSLY” evokes Eliot’s The Waste Land, where “April is the cruelest month” and in which the poet makes a spiritual “walk” through the waste land of Western society in search of a spiritual transcendence. In DARKWALKING ENDLESSLY, the transcendence is harder to achieve, however, because if April is the cruelest month, then “A YEAR OF BREAKING APRILS” is the signal of a monotony of cruelest months that does, indeed, seem endless. If there is to be a transcendence, then, it is to come through the blues, through a different kind of rain: a “BLUE RAIN FALLING IN SOFT EYEDROPS FROM NUDE BODIES OF DANCING PLANETS, BEATS OF SCIENCE PLAYED ON VIBRATED TEETH OF OPEN-MOUTHED AFRICAN HARPSICHORDS.”Footnote 62

Kaufman evokes the blues more through his imagery and the “manner in which Negro blues songs juxtapose unrelated images,” as Richard Wright puts it, than he does through blues rhythms, the way a poet like Langston Hughes does.Footnote 63 Nonetheless, the blues is central to Kaufman’s aesthetic; his is a bebop bluesgoth, and it is the surrealism of blues texts that Kaufman finds most useful.Footnote 64

Kaufman’s mode in “The Ancient Rain” is not exclusively all caps, but it is the dominant mode. I read this as signifying the prophetic tone and aura which Kaufman takes in these poems. Here, a traumatized Kaufman, recovering from shock therapy and, along with the rest of the nation, the shock of the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath, is proclaiming from his place of silence on the insanity in which he sees his fellow humans so casually engaged. If Kaufman has taken a personal vow of silence in general society, then in his poetry, through his capital letters, he is screaming.

“The Ancient Rain,” however, the eponymous poem which ends the collection, is not written in all capital letters. Nor is the poem preceding it, “January 30, 1976: A Message to Myself,” which ends, “The Ancient Rain is falling all over America now. / The music of the Ancient Rain is heard everywhere.” Kaufman then begins the title poem, “The Ancient Rain,” in a spiritualized Afrogothic ex cathedra mode reinvoking the tragic through the “blue rain like the rain that fell when John Fitzgerald Kennedy died.”Footnote 65 The blue rain is the blues: it has the potential for the terrible, as in the death of Kennedy, as well as the sublime, as in the music of the dancing spheres.

Thus Kaufman is loudest when he is silent. This is not just Afrogothicism; it is also Black surrealism. Plumbing the depths for Blackness is a plumbing of the depths for this terrible sublime, and the connection between Black surrealism and Afrogothicism is fundamental to the terrible sublime. Indeed, the concept of rationality, which would come at the beginning of a so-called enlightenment that would separate people into civilized and savage, Western and non-Western, and ultimately Black and white, would situate the Black squarely in the realm of the Gothic, the savage, the dark, the Dionysian and the dystopian. As Aldon Nielsen writes in his important article on Bob Kaufman, “Kaufman’s poetry joins a radical tradition of surrealism and racial politics that reaches back through García Lorca’s Poet in New York and Aimé Césaire’s Return to My Native Land to the radical politics of the French Surrealist Group.”Footnote 66 Indeed, this tradition reaches back not only to Lorca’s duende, but also to the blues, and connects Black art with the Spanish duende which Lorca also saw as counter to the traditional Western muse.Footnote 67 These traditions, in their engagement with death, then act as reinterpretations of ancient spiritual texts like the Egyptian Book of the Dead, texts in which life and death coexist and which act as something like guides one engages with in life to lead one through the terrors and mysteries of death.

Conclusion

In this article I have taken two case studies of authors writing within the blues Afrogothic tradition, namely Jean Toomer and Bob Kaufman. I argue that the Afrogothic tradition has a literary prehistory that goes as far back as ancient texts like the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a book that looks to a sublime transcendence of the condition of death, or the “terrible sublime.” By tracing this thread through the labyrinth of Black diasporic traditions, we gain further insight into the way members of the Black diaspora reinvented and reconceived spiritual ideas that they traded with the Western world from far back into antiquity. Because the Gothic has traditionally been attributed to whiteness, whether that be through the crumbling European castles in which the term has its origins in literary studies or through the northern and southern American Gothics popularized by regionalist authors like Washington Irving, Edgar Allen Poe, William Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor, nonetheless a Black Gothic tradition, or an Afrogothic tradition, has also existed for just as long. This is because, if Gothicism seems to make a chiaroscuro dichotomy of darkness and light, black and white, then to be Black in the world of Gothicism is to take a distinct position in this good/evil construct upon which Gothicism is built. And yet, for Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab, it is the unknowable whiteness of the whale that is horrific, and for the islanders of Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, whiteness is also a horror. As Toni Morrison reminds us, “Pym engages in cannibalism before he meets the black savages; when he escapes from them and witnesses the death of a black man, he drifts towards the silence of an impenetrable, inarticulate whiteness.”Footnote 68 If whiteness is horror and if Blackness is also horror, then Afrogothicism suggests that the horror comes solely through the inability of the individual to transcend these horrific dichotomies we have placed upon each other. On the other hand, Afrogothicism also suggests that we can transcend these dichotomies we have placed upon each other by embracing the horror. From the Black Gothic Harlem mansions that were the salons of the Harlem Renaissance to the southern Gothic romances of Jean Toomer to the New York bebop bluesgoth of Bob Kaufman, the Afrogothic embodies the terrible sublime.

Afrogothicism is making a resurgence and speaks to us again today. Popular television shows such as Lovecraft Country (2020), or the film Get Out (2017) play with themes of horror and Blackness, race and transcendence. The collection of short stories Out There Screaming (2023) is edited by Get Out director Jordan Peele, and features Black authors who explore the Gothic from the supernatural Black past to the supernatural Black future. The American imagination is haunted by its past, and the past continues to resurface, like the undead, to reconnect the country to the blues through the surreal landscape of the haunted American psyche. Plumbing the depths of the Afrogothic, one can find limitless possibilities for writers to explore aspects of the American surreal that tread the terrible sublimity of living in a country whose manifest destiny has manifested as a kind of blessed damnation.

Whit Frazier Peterson is a Lecturer and Postdoctoral Research Associate in American Studies at the University of Stuttgart in Stuttgart, Germany. His dissertation focussed on canon theory and coterie anthologies, and his current research interests center on countercultural movements and American religious traditions. He also has core interests in African American literature, transnational modernism, Black speculative fiction and the Black esoteric tradition. He has placed articles in Callaloo, the Polish Journal of American Studies, Black Perspectives, Siècles, Black Scholar, and Amerikastudien/American Studies among other publications. He has also published three novels: one set during the Harlem Renaissance and another during the 2008 election cycle; the third can be considered a historical novel set in the future.