LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article, you will be able to:

-

• express an informed view on a general psychological theory of how individuals relate to one another

-

• understand how interrelating becomes dysfunctional and the importance of this for understanding personality disorder

-

• identify the process whereby a therapeutic encounter can resolve conflictual relationships.

Interpersonal theory focuses on how humans relate to one another and has its genesis in the work of Harry Stack Sullivan, an American neo-Freudian and psychiatrist. He emphasised the interpersonal nature of personality, writing ‘personality can never be isolated from the complex of interpersonal relationships in which [a] person lives’ (Sullivan Reference Sullivan1947: p. 5). His work has subsequently been developed by several authors, including Timothy Leary, Jerry Wiggins, Donald Kiesler, Jeremy Safran and others. It is impossible to do justice to its rich developmental history here, but I would refer the interested reader to papers by Wiggins’ (Reference Wiggins1996) and Wagner & Safran (Reference Wagner, Safran, Castonguay, Muran and Angus2010) for helpful summaries of its elaboration. As this is a review bound by history, an update on the theory is portrayed by Hopwood et al (Reference Hopwood, Wright and Ansell2013). In this review, I will sketch only its main elements, but particularly focus on the contributions of the late Donald Kiesler, whose work, I believe, ought to be better known outside of North America. But why should it be relevant to personality disorder?

The interpersonal nature of personality disorder

First, one might argue that interpersonal difficulties are the crucial defining feature of personality disorder, as both DSM-5 and ICD-11 in their general definitions of the condition make clear. ICD-11, for instance, describes personality disorder as comprising ‘impairments in functioning of aspects of the self (e.g., identity, self-worth, capacity for self-direction) and/or problems in interpersonal functioning (e.g., developing and maintaining close and mutually satisfying relationships, understanding others’ perspectives, managing conflict in relationships’ (World Health Organization 2024: p. 553; my italics). DSM-5 is more succinct but similar in defining personality disorder as having ‘impairments in personality (self and interpersonal) functioning and the presence of pathological personality traits’ (American Psychiatric Association 2013: p. 761; my italics).

Here, there is a definitional problem that needs to be addressed. One might query, for instance, whether there is a real distinction between impairments of the self and in interpersonal functioning, as the demarcation lacks clarity. For example, in a narcissistic individual, there is clearly a disordered sense of self encompassing self-entitlement, grandiosity, etc. which inevitably manifests itself in disordered interpersonal relationships by exploiting others, etc. Hence, the demarcation between self and interpersonal functioning is unclear.

Perhaps a more crucial distinction is where there is fragmentation of self (‘identity, self-worth and capacity for self-direction’) as compared with a dysfunction of interpersonal functioning in the presence of a coherent sense of self. Although both ICD and DSM appear to give equivalent weight to the dysfunction of self and interpersonal functioning in their definitions of personality disorder, clinically, it is an impairment of the latter that characterises the majority of those with personality disorder. For instance, in someone with narcissistic personality disorder, one could argue that their ‘identity, self-worth and capacity for self-direction’ are not in any way impaired in the sense of being fragmented; rather, these features coalesce around a dysfunctional identity that is entirely congruent but one that is neither helpful to self nor to broader society, and hence the disorder (Edershile Reference Edershile and Wright2025). Indeed, it is this very congruence of self – rather than its fragmentation – that creates such a resistance to change.

There is one exception and this applies to borderline personality disorder, which, it could be argued, is unique among those with personality disorder in showing this fragmentation of the self. It is here (and only here) that one finds mercurial changes in ‘identity, self-worth and capacity for self-direction’. As ever, it all depends on how the self is defined, but there is no doubt that interpersonal dysfunction is a crucial component of personality disorder and hence it ought to be the main focus of treatment.

Second, one needs to recognise that attempts at exploring and attempting to change this interpersonal component of a person’s personality (or its disorder) can be seen as an attack on the ‘person’ and therefore why it might provoke a negative response. Hence, extreme sensitivity is required in such an endeavour. This sensitivity as to the nature of the disorder would not apply to the same degree to a clinician treating someone with, say, other mental health conditions such as depression or schizophrenia or indeed physical disorders. These are, after all, ailments visited upon, rather than part of, the self, as is the case with personality disorder.

Finally, how one understands and manages this interaction between patient and therapist is a critical component in developing effective treatments for those with personality disorder. Although a wide array of treatments – both physical and psychological – have been assessed for efficacy in borderline personality disorder, few of these have been tested for other personality disorders, and although some have shown some modest effects (Storebø Reference Storebø, Stoffers-Winterling and Völlm2020), these gains have often failed to be replicated when compared with high-quality generic clinical care (Chanen Reference Chanen, Betts and Jackson2022). Moreover, even when there is symptomatic improvement in borderline personality disorder, a sense of social isolation and feeling of emptiness persist (Alvarez-Tomás Reference Alvarez-Tomás, Soler and Bados2017). Here, there is an important caveat in that these evaluations consider evidence from groups rather than from the individual, and extrapolating such group findings to the individual is not straightforward. To paraphrase an argument from Kiesler’s (Reference Kiesler1966) critique of psychotherapy research: given personality disorder’s considerable heterogeneity, the more pertinent question is not ‘what works for personality disorder?’ but rather ‘what works for this individual with this personality disorder?’. What is required then is a theory that has sufficient generality that it can be applied to groups, but also is sufficiently nuanced that it can be applied to the individual. Interpersonal theory has the capacity to fulfil both of these requirements.

Interpersonal theory

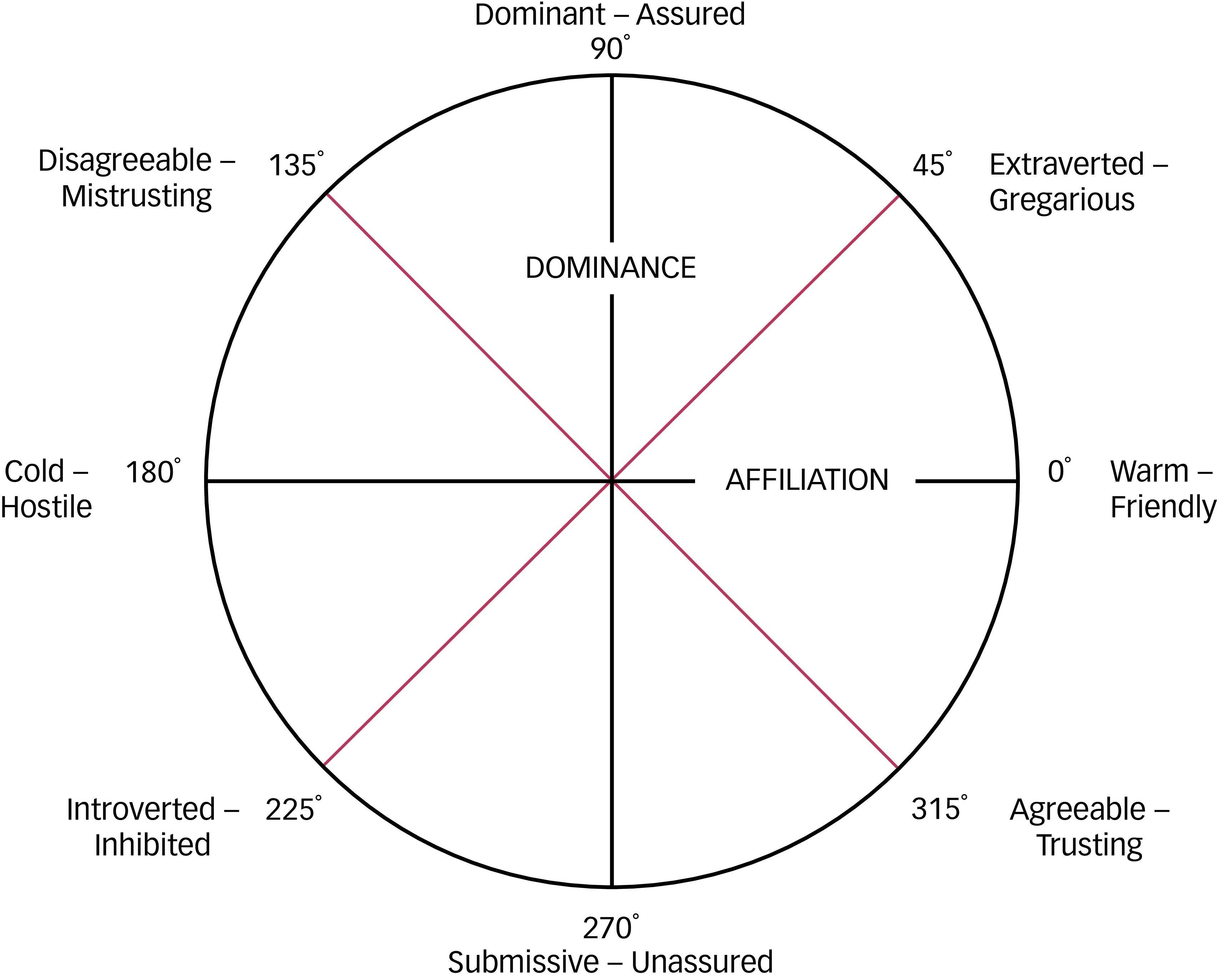

Interpersonal theory is premised on how humans (and other animal forms) face the challenge of relating to one another by achieving a balance between (a) affiliation and (b) dominance (i.e. a wish to relate to others but also to control them). This produces a dimensional representation of personality organised around these two major axes, orthogonal to one another, with the extremes (the poles) of its ‘affiliation’ axis represented by ‘cold (hostile)’ versus ‘warm (friendly)’ and those of its ‘dominance’ axis by ‘dominant’ versus ‘submissive’ in a circumplex. Combinations of these two dimensions can then be pooled to produce blended variants around the centre (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 The interpersonal circumplex, with the axes of affiliation and dominance and their derivatives.

There have been various elaborations of this basic portrayal of the theory, but it has been criticised as being too value laden, so alternatives have been proposed. John Birtchnell’s octagon theory, for instance, posits the alternative dimensions of ‘close’ versus ‘distant’ and ‘upper’ versus ‘lower’, as these are generic and value free (Birtchnell Reference Birtchnell2010). Although I believe that this nomenclature is superior, here I will use the more conventional terms, such as cold (hostile)/warm (friendly) rather than close/distant, and dominant/submissive rather than upper/lower.

Consequences of interpersonal theory

Normality versus abnormality

How relating takes place around this circumplex has the following implications. First, it implies that normality in relating is close to the centre, as it is here that one finds someone who has a repertoire of responses to interpersonal encounters that is varied and appropriate, but not extreme. Thus, ‘normal’ individuals can move flexibly around the centre, with an array of wide-ranging and adaptive interpersonal responses to the situation in which they find themselves, resulting in harmonious and stable relationships. Second, those who occupy a position at the edge of the circumplex have responses that are not only more extreme, but also more limited, resulting in a constrained behaviour repertoire that remains the same irrespective of the situation. For instance, someone who occupies a position at the ‘dominant’ pole of the axis is likely to behave in a dictatorial and controlling manner irrespective of the circumstances in which they find themselves, so that they appear overbearing and autocratic as they are intent on eliciting a submission from their respondent. So, the first consequence of the theory is that normality is associated with interpersonal flexibility, whereas abnormality is associated with both extreme and constrained interpersonal behaviour. The relevance of this observation is that rigidity and extremity of interpersonal behaviour, irrespective of the circumstances, is one of the core defining features of personality disorder.

DSM-IV shows the position of some of the personality disorders on the circumplex. It is worth noting that borderline personality disorder does not appear, and there is good reason for this omission. As referenced above, borderline personality disorder is unique among personality disorders in that it has a fragmented rather than a coherent sense of self and this is reflected in such a disordered interpersonal style that it cannot be represented within the circumplex. This also has implications for how the patient–therapist interaction is managed therapeutically (see the ‘Borderline personality disorder’ section below).

Complementarity

The theory is further developed by considering the interpersonal exchanges of the interactants within the system, or what has been termed their complementarity. Sullivan (Reference Sullivan1953) introduced this in his ‘theorem of reciprocal emotion’, in which he stated ‘integration in an interpersonal situation is a process in which (1) complementary needs are resolved, or aggravated; (2) reciprocal patterns of activity are developed, or disintegrated; and (3) foresight of satisfaction, or rebuff, of similar needs are facilitated’ (Sullivan Reference Sullivan1953, p. 198). He also emphasised that both parties contribute to the interpersonal exchange; Kiesler (Reference Kiesler, Anchin and Kiesler1982: p. 198) quotes Sullivan: ‘neither Person A’s nor Person B’s needs alone determine the outcome. Interpersonal needs always seek conjoint expression and resolution.’ Finally, Sullivan’s other important contribution is his observation that the interpersonal exchange constrains the response of the interactant. This constraint, in turn, reinforces the first person’s ensuing actions.

Subsequently, it was left to others, but particularly to Robert Carson, to develop this aspect of the theory further. Here, I shall do no more than mention the main features of the theory of complementarity and I refer interested readers to the work of Carson (Reference Carson1966) and Kiesler (Reference Kiesler1983) for a more complete account.

The ‘evoking message’

As human interpersonal interaction aspires to be as anxiety free and as stable as possible, this is achieved through ‘unconscious evoking messages that function to constrain the others’ reactions to those that are predictable and comfortable for the individual’ (Wagner Reference Wagner, Safran, Castonguay, Muran and Angus2010: p. 218). Thus, one individual is manoeuvred by another to adopt a relationship position that is ‘complementary’ to the one being offered and is mutually rewarding to both participants. If this does not occur, then the relationship is unlikely to endure, or the interaction is altered such that complementarity is re-established.

Correspondence versus reciprocity

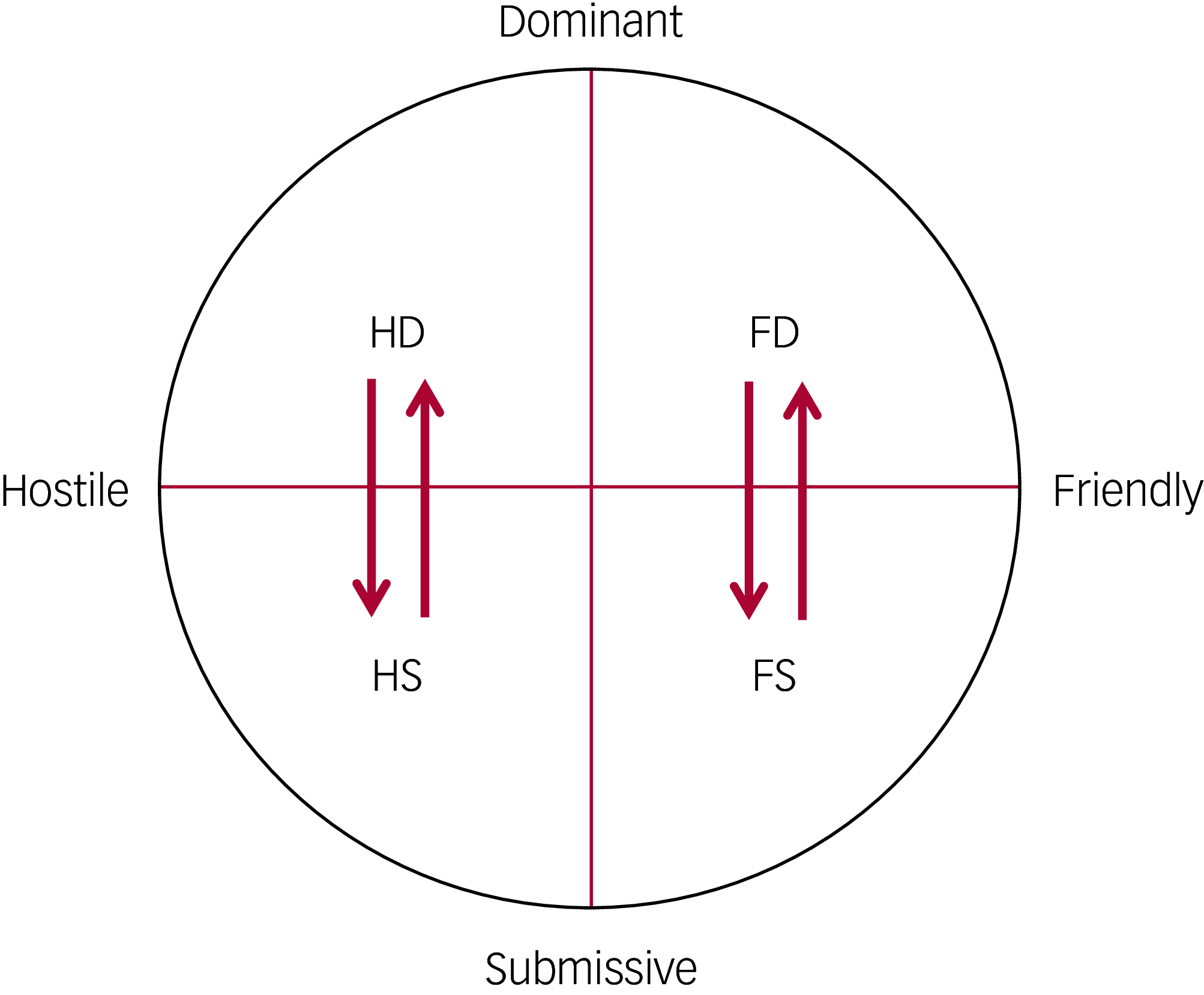

Interpersonal theory posits further that in order to maintain stability in relating, correspondence occurs on the affiliation axis (friendliness invites friendliness, and hostility invites hostility), whereas reciprocity tends to occur on the power axis (dominance invites submission, and submission invites dominance). For instance, a complementary response is established when an individual in the Hostile/Dominant quadrant evokes a hostile/submissive response from someone in the Hostile/Submissive quadrant. Similarly, someone in the Hostile/Submissive quadrant would seek a complementary hostile/dominant response from someone in the Hostile/Dominant quadrant. When these trait styles are not concordant, interpersonal messages are sent to pull a complementary response to alter the partner’s behaviour towards one that is reinforcing to their preferred style (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 Complementarity within the interpersonal circumplex. D, dominance; S, submission; H, hostility; F, friendliness. The direction of the arrows shows a complementary response.

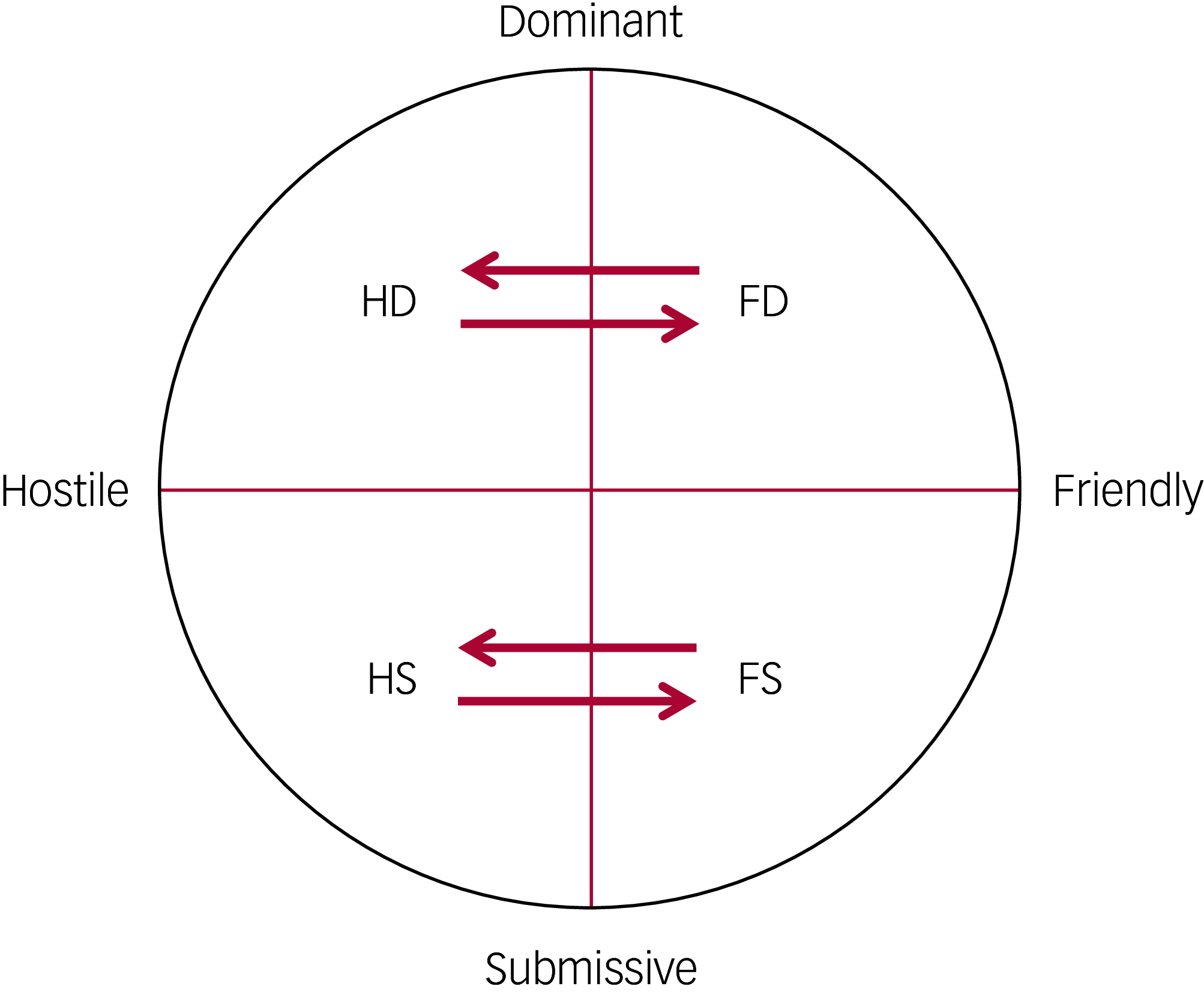

Anti-complementarity

If two individuals are in opposite quadrants (e.g. Hostile/Dominant and Friendly/Dominant or Hostile/Submissive and Friendly/Submissive), their evoking messages are unlikely to work, so a state of anti-complementarity results (Fig. 3). In such an interaction, as neither the individual’s affiliation nor their status is supported, this will be experienced as minimally rewarding or aversive. Consequently, the relationship is unlikely to survive. This has relevance to the psychotherapeutic process as here the therapist needs to take an anti-complementarity stance in order to effect change. In so doing, they face the challenge of maintaining the relationship while also seeking to move the patient from their preferred position (see the ‘Therapeutic implications’ section below).

FIG 3 Anti-complementarity within the interpersonal circumplex. D, dominance; S, submission; H, hostility; F, friendliness. The direction of the arrows shows an anti-complementarity response.

The unconscious element of interactions

As regards the interaction, it is important to realise that this interpersonal communication in relationships is more unconscious than overt. Here, Kiesler was heavily influenced by communication theory and figures such as Beier, Haley and Watzlawick and others. To quote Beier (Reference Beier1966) for instance,

‘The evoking message is probably one of the basic tools used by individuals to maintain their consistency of personality. With this message an individual can elicit responses without being aware that he is responsible for doing so. To a certain extent he can create his environment without feeling that he is accountable for the responses which come his way’ (p. 13).

To capture this non-verbal messaging, Kiesler and colleagues developed the Impact Message Inventory (IMI).

The Impact Message Inventory (IMI)

Traditionally, psychological assessments (including those of personality disorder) consist of evaluating individuals through their responses to questionnaires, face-to-face interviews – with either the individual or significant others – neuropsychological tests, etc., all of which focus directly on the responses of the individual being assessed. Kiesler adopted a different strategy by focusing on the ‘receiving end’ of the communication in the interpersonal exchange. He posited that ‘the interpersonal style of one person A can be validly defined and measured by assessing the covert responses or “impact messages” of another person B who has interacted with or observed A’ (Kiesler Reference Kiesler1975, p. 1). Thus, the interpersonal style of A is identified by measuring the interpersonal responses of B, who has interacted with A.

The IMI is therefore a self-report transactional inventory and is unique in that it focuses not on the patient’s status or reactions directly, but on measuring the impact of their interaction on the recipient. The recipient’s covert impact messages include elements of feelings, action tendencies (impulses to respond in specific ways), fantasies and attributions (about the evoking person’s intent, character, etc.) (Kiesler Reference Kiesler1975). These are measured on three subscales on the IMI, which assess direct feelings (e.g. ‘When I am with this person, he makes me feel dominant’), action tendencies (‘When I am with this person he makes me feel that I could lean on him for support’) and perceived evoking messages (‘When I am with this person he makes me feel that I want to put him on a pedestal’), where respondents rate their reactions on a 1–4 Likert scale, from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much so’ (Kiesler Reference Kiesler1975, p. 2).

The IMI has been used in research in studies on psychotherapy processes and outcome, personality and depression, etc. to establish its validity and utility. By way of illustration, I will refer to Daffern et al’s (Reference Daffern, Duggan and Huband2008) study, which examined whether the IMI predicted in-patient aggression and treatment non-completion among patients with personality disorders in a medium secure unit. Four members of nursing staff independently completed the IMI shortly after each patient’s admission. Results showed that aggressive patients were rated on the IMI as being more dominant and competitive and that those who completed treatment were rated as more nurturing and help-seeking. In a companion study, Daffern et al (Reference Daffern, Duggan and Huband2009) found that there was no significant variability among the nursing staff who assessed patients using the IMI (i.e. there was consistency in their responses). These results offer some preliminary evidence that not only does the IMI have utility as an outcome measure in such a setting, but, more importantly, that it is reliable among respondents, tapping into a sensitivity and responsivity to evoking messages that are universal among us as humans.

Therapeutic implications

Kiester (again) provides a useful summary of the implications of interpersonal theory in psychotherapeutic practice (Kiesler Reference Kiesler1983). At the beginning of therapy, the patient intentionally and unintentionally shapes the therapist to respond to them from a restricted aspect of the therapist’s own internal experience and behavioural repertoire. Here, the patient/client has the whip hand so that ‘the therapist cannot but be hooked or sucked in by the client, because the client is more adept, more expert in his distinctive, rigid, and extreme game of interpersonal encounter’ (Kiesler Reference Kiesler, Anchin and Kiesler1982: p. 281).

The therapist’s task is then to become aware of how they are being manoeuvred by the patient by being attentive as to how their own actions, attributions and fantasies are being altered by the interaction. In interpersonal theory, this refers to an awareness that one is being pulled to give a complementary response by the patient to re-establish harmony and stability in the relationship. Becoming aware of this ‘pull’ and a realisation that this is the unconscious activity of the patient rather than something within the therapist is a crucial component of the therapeutic encounter. Having this self-awareness goes to the heart of any psychotherapeutic encounter in which the therapist has not only the competence, but also the confidence, to decide on how they are being manoeuvred by the patient to respond in a way that is out of character. With personality disorder, this can be especially challenging as it encompasses a judgement on much of what passes for ordinary human interaction. It emphasises the need for extensive training, together with ongoing support and supervision for those engaged in such work.

With this realisation, the therapist then needs to disengage and stop the reinforcement of the individual’s pathological style by interrupting their automatic responses to the patient. With a dependent individual, for instance, the therapist may begin to withhold advice and take control so as to interrupt the pattern of reinforcement of the individual’s pathological dependent style. This can then progress to the therapist engaging in anti-complementary actions that challenge the patients’ bid for further reinforcement based on the elements of the interpersonal circumplex. The contents of this phase focus on the self-defeating consequences for the patient of their extreme and rigid behavioural pattern.

When the therapist changes from a complementary to an anti-complementary role there is an opportunity to link the patient’s immediate response to their more habitual behaviour. Clearly, this would need to be done sensitively and in a non-judgemental way, for example ‘I notice that you seem a little disappointed [uncomfortable/angry etc. depending on the response] that I failed to meet your expectation that I would provide you with an extra session as you were lonely. I wonder whether you see any connection between this and how you have reacted to similar perceived rejections in the past’.

Borderline personality disorder

There is one exception to this general rule of the predictability of the interaction and this refers to borderline personality disorder, which, as we have seen above, is difficult to locate within the interpersonal circumplex. This is because of its rapid change of self states, an alteration between idealisation and denigration, impulsive behaviour, etc. This has treatment implications as the therapist has to be nimble and be able to follow the patient through an unpredictable landscape. This is well captured by Marsha Linehan:

‘The patient is frequently like a dancer twirling out of control. The therapist has to move in quickly with a counterforce to stop the patient from moving off the dance floor. “Dancing” with the patient often requires the therapist to move quickly from strategy to strategy, alternating acceptance with change, control with letting go, confrontation with support, the carrot with the stick, a hard edge with softness, and so on in rapid succession’ (Linehan 1993: p. 203, cited in Hopwood Reference Hopwood, Wright and Ansell2013).

People with borderline personality disorder are also unusual in that they are treatment seeking (in contrast to many people with personality disorders who reject treatment) (Tyrer Reference Tyrer, Mitchard and Methnen2003); but this can create another problem and that is that disengagement can be difficult and needs to be carefully thought through.

Birtchnell and ‘competency’

To conclude, it is only fair to reference John Birtchnell, whom I have already mentioned for his less value-laden perspective of the circumplex. In his book Relating in Psychotherapy (Birtchnell Reference Birtchnell2002), he recognises, for instance, the existence of an unconscious, automatic, inner brain, which has ineffective relating strategies; he refers to these as a lack of ‘competency’. The psychotherapist’s task then is, through the conscious outer brain, to correct and improve within the axes of control and affiliation these mutually reinforcing and destructive elements of their interaction. Birtchnell sees achieving such ‘competency’ as a process that is common to all psychotherapies – individual, couple, group or family.

Alliance ruptures

Another important advance in psychotherapeutic thinking relevant to this discussion is that of alliance ruptures and their repair, stemming from the operational and empirical study of the therapeutic relationship by Jeremy Safran and colleagues. ‘Alliance ruptures’ are defined as a tension or breakdown in the collaborative relationship between the patient and the therapist, varying in intensity from brief disengagements to full-blown termination (Safran Reference Safran, Crocker and McMain1990). This thinking has been heavily influenced by interpersonal theory, as the therapeutic relationship is conceived ‘as consisting of intersecting dimensions of affiliation and interdependence on the interpersonal circumplex’ (Safran Reference Safran, Crocker and McMain1990).

Hence, they stress that such ‘ruptures’ (a) are interactive: ‘a rupture is not a phenomenon that is located exclusively within the patient or caused exclusively by the therapist. Rather a rupture is an interactive process that includes these kinds of experiences that play out within the context of each particular therapeutic relationship’ (Samstag Reference Samstag, Muran, Safran and Chaman2019: p. 188); and (b) that they recapitulate long-standing interpersonal interactions: ‘Ruptures often emerge when therapists unwittingly participate in maladaptive interpersonal cycles, that resemble those characteristic of patients’ other interactions, thus confirming their patients’ dysfunctional interpersonal schemas or generalized representations of self-other interactions’ (Safran Reference Safran and Muran1996: p. 447). Being aware of this interpersonal pull and being able to detach oneself sufficiently to collaboratively explore what is taking place in the therapeutic relationship, they refer to therapeutic metacommunication (adopted from Kiesler Reference Kiesler1996).

Complementarity and countertransference

This type of therapist reactivity is a very similar to, but a more generalised aspect of, countertransference in the analytic literature. Countertransference was initially conceived as something that impeded therapeutic work – a psychological blind spot in the analyst that needed to be understood and dealt with. Over time, however, far from being a barrier, attentiveness to one’s countertransference was seen as providing ‘an additional avenue of insight into the patient’s unconscious mental processes’ (Sandler Reference Sandler, Dare and Holder1973, p. 66). The value of countertransference in the treatment of personality disorder was noted by Kernberg (Reference Kernberg1965), who wrote ‘that the full use of the analyst’s emotional response can be considered to be of particular importance in the treatment of patients with profound personality disorders’ (cited in Sandler Reference Sandler, Dare and Holder1973, p. 66).

This suggests that one’s interpersonal response in the therapeutic encounter might provide not only valuable information on the patient’s interpersonal pathology but also an opportunity to ameliorate it. There is no better description of the value of this interactive process between therapist and patient than that in a quote from James Stratchey in the early psychoanalytic literature:

‘The original conflicts, which had led to the onset of neurosis, began to be re-enacted in the relation to the analyst. Now this unexpected event is far from being the misfortune that at first sight it might seem to be. In fact it gives us our great opportunity. Instead of having to deal as best we may with conflicts of the remote past, which are concerned with dead circumstances and mummified personalities, and whose outcome is already determined, we find ourselves involved in an actual and immediate situation, in which we and the patient are the principal characters and the development of which is to some extent at least under our control’ (Strachey Reference Strachey1934).

This early psychoanalytic quote shows a remarkable concordance with much of what has been written here, as there is an (a) interpersonal encounter enacted with the analyst which is not only (b) conflictual but also (c) involves an ‘actual and immediate situation […] under our control’ and (d) is a great opportunity to engage in a real life encounter between two parties so that progress is possible. Indeed, these intersubjective negotiations between a patient and therapist in developing and maintaining the therapeutic relationship in spite of the conflict, and the patient’s emerging experience of a new and constructive connection with the therapist, are considered the ‘very essence of the change process’ (Safran Reference Safran and Muran2000).

Case vignettes

The following fictitious case vignettes show how an understanding of a person’s position within the interpersonal circumplex can inform therapy and management of individuals with personality disorders in forensic settings.

Vignette 1: dependent personality disorder

M.B. was a 38-year-old man who grew up in Manchester, the only son of high-achieving middle-class parents. Convicted of homicide, he was detained in a high secure hospital and received a diagnosis of dependent personality disorder. He had no other criminal history.

He was thought suitable for transfer to a lower level of security, but attempted to sabotage the transfer by taking a medication overdose. This pattern was repeated when he was later moved to the community, when he claimed that he had homicidal fantasies after leaving hospital. This effected his readmission, ensuring that his dependency needs continued to be met. Evidence of his extremely high levels of dependency were provided by (a) his index offence (an inexplicable attack on his landlady when his partner unexpectedly left him) and (b) dropping out of university and subsequently failing to obtain employment, although being very intelligent.

Within the interpersonal circumplex (Fig. 1), he occupied a position in the lower right quadrant (being both highly submissive and friendly). Psychotherapeutic work – in which he engaged fully – consisted of the team progressing to take an anti-complementarity position encouraging him to become more independent when faced with his discharge. Although it took several attempts, he was eventually discharged as he was able to work through his resistance and overcome his high level of dependency. Follow-up showed someone who, although he had made peace with the world, had not realised his full potential.

Vignette 2: paranoid personality disorder

A.M. was a 24-year-old man seen for assessment in prison. He had had a turbulent childhood, coming from a broken home and having to rely on his own resources from an early age in order to survive. He quickly graduated from petty crime to become involved in the drug trade, which often involved extreme violence. He was suspicious of others, bore grudges and never developed any intimacy in relationships.

The assessment interview was difficult as it was impossible to establish any kind of emotional connection. A.M. was angry, belligerent and dismissive of this ‘shrink’s’ credentials and interest in him. He perceived any questions as intrusive and refused any offer of help. There was no evidence of psychosis. He terminated the interview prematurely, believing that the process was yet another attempt ‘to set him up’. The interviewing psychiatrist was shaken by the encounter.

Despite the inadequacy of the information on direct contact, it was sufficient to conclude that A.M. had paranoid personality disorder and he occupied a position in the left upper quadrant of the interpersonal circumplex – representing a dominant and hostile disposition (Fig. 1).

Comment: patients such as A.M. rarely if ever present to the general psychiatrist, as they believe that there is nothing psychologically wrong with them and certainly nothing that mental health services can offer. Occasionally, they may present to a forensic psychiatrist if they are compelled to do so or, more likely, there is some advantage for themselves by so doing. They present a formidable therapeutic challenge. Although the assessing psychiatrist has little impact on A.M., informing the in-reach mental health team (and the prison staff) of his findings might help those caring him work out how their interaction with this difficult inmate might be improved. For instance, a way forward might be to try to establish a positive relationship by avoiding A.M.’s personal concerns and his need to achieve control and not responding to provocation. These are all more easily said than done, but they are essential elements in the interaction that overtime may lead to a more equitable exchange.

Conclusion

I have attempted to make the following points in favour of interpersonal theory. First, although personality disorder is a disorder in the sense that those who are so labelled are distressed (in the same way that those labelled with other mental disorders – e.g. depression or bipolar disorder – are distressed), it is also distinct in that it is personal (i.e. part of the person) in a way that other mental disorders are not. Consequently, it requires especial sensitivity in both its recognition and management.

Second, interpersonal theory has the scope (as it includes both normality and abnormality along a spectrum in the interpersonal circumplex) for it not to be seen as pejorative by those who are sensitive to labelling. It is also sufficiently comprehensive to allow a broad array of psychological interventions without being tied to the theoretical underpinnings of any. It therefore has the capacity to avoid the internecine warfare between competing schools of psychotherapy.

Finally, it has the capacity to be rigorously evaluated (using data from groups), but also has the sensitivity to be applied to an individual.

Nonetheless, interpersonal theory faces some challenges in its implementation. Primarily, one has to question why, almost 100 years since it was first introduced by Sullivan, it has never been very fashionable or become more mainstream. One reason may be that it is intellectually demanding (I have provided only a brief summary in this article) and there is still much more to be done in its development.

Furthermore, in therapy there is an enormous emphasis on one of the interactants (i.e. the therapist) to (a) decide on what is normal/abnormal using the self as the resonator and (b) have sufficient strength to manage the resistance that will inevitably emerge in moving the patient forward. As the individual therapist is so crucial as part of the dyad, extensive training and ongoing supervision will be necessary to maintain treatment fidelity, which inevitably will be expensive. This expense, however, has to be matched against the costs that those with personality disorder inflect on themselves and others, often across a life-time.

Although there are pros and cons to the approach, interpersonal theory provides a way of thinking that is both rigorous and therapeutically informative for a group of individuals that have hitherto been poorly served by psychiatrists.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Which of the following individuals has not contributed to the development of interpersonal theory?

-

a Sigmund Freud

-

b Timothy Leary

-

c Donald Kiesler

-

d Harry Stack Sullivan

-

e Jeremy Safran.

-

-

2 Interrelating is a crucial aspect of personality disorder, but which of the following is incorrect?

-

a Dysfunctional relating is a common aspect of the definition of personality disorder in both DSM-5 and ICD-11

-

b Most personality disorders can be identified by the person’s specific style of interrelating

-

c Borderline personality disorder is similar in this regard to the other personality disorders

-

d Borderline personality disorder has specific issues regarding how the self is organised

-

e Most personality disorders are associated with a coherent sense of self.

-

-

3 In interpersonal theory, which of the following statements is incorrect?

-

a The optimal relating position is to be close to the centre in the interpersonal circumplex

-

b Opposite poles in the interpersonal circumplex provoke a complementary response

-

c Both individuals contribute to the interaction

-

d Even if interpersonal actions are discordant, the relationship is likely to continue

-

e Interpersonal theory provides guidance on how a therapist ought to respond.

-

-

4 As regards the concept of therapeutic ruptures, which of the following statements is incorrect?

-

a Jeremy Safran has been a major contributor

-

b This concept is supported by observational data

-

c The therapist needs to recognise their own shortcomings in the rupture

-

d Resolving the rupture is the responsibility of both parties

-

e When a rupture occurs, its identification and repair is the responsibility of the patient.

-

-

5 As regards the contribution interpersonal theory can make to the National Health Service provision of psychotherapy, which of the following statements is incorrect?

-

a It is sufficiently general that it can encompass the several different schools of psychotherapy

-

b Its breadth, encompassing both the normal and the pathological states along a continuum, suggests that it is not stigmatising.

-

c It places a heavy burden on services for adequate training and ongoing supervision, so that it may be difficult to implement in practice

-

d It is easy to comprehend and has been fully articulated

-

e Its development has been mostly in North America and hence it is insufficiently known in the UK.

-

MCQ answers

-

1 a

-

2 c

-

3 d

-

4 e

-

5 d

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.