I. Introduction

Common ownership has been increasing in the United States (Azar (Reference Azar2012), Backus, Conlon, and Sinkinson (Reference Backus, Conlon and Sinkinson2021)). This trend has sparked discussions among policymakers, industry practitioners, and academics about whether it poses an antitrust issue.Footnote 1 Existing empirical research has focused on how firm- or industry-level measures of common ownership relate to product prices, but the evidence remains inconclusive.Footnote 2 Per Rotemberg (Reference Rotemberg1984), a firm incorporating its shareholders’ preferences will maximize the joint profits of its own and its competitors, potentially softening competition when shareholders commonly own competitors’ stock. In this framework, common owners benefit from the reduced product-market competition. However, this raises two natural follow-up empirical questions: i) whether common owners are financially rewarded for holding common ownership positions and ii) how they manifest their preferences in corporate policy.Footnote 3

This article studies the returns and voting behavior of institutional investors adopting high common ownership strategies. We test three hypotheses. First, we study whether active investors who choose to own product-market competitors earn higher returns. Second, because most common owners are institutional investors who have an incentive to create value for their end clients (Lewellen and Lewellen (Reference Lewellen and Lewellen2022)), we test whether the end clients of these institutional investors benefit net of fees, and whether fund managers themselves are financially rewarded. Third, we test the extent to which common owners vote in favor of corporate policies that potentially soften product-market competition (Antón et al. (Reference Antón, Ederer, Giné and Schmalz2023)). Jointly, these three hypotheses shed light on the plausibility of the common ownership hypothesis by focusing on a key premise and mechanism: whether and how common ownership is associated with higher value for common institutional owners and their clients. We test these hypotheses in the data by focusing on actively managed equity mutual funds.

Studying actively managed equity mutual funds has four advantages.Footnote 4 First, by the end of 2018, the funds in our sample managed $3.8 trillion in assets, and many were large common owners. Second, the literature offers a well-established framework to evaluate mutual fund performance, allowing us to relate common ownership positions to investment performance. Third, active funds have incentives to outperform, creating cross-sectional variation in investment strategies and returns. This variation allows us to compare funds with different levels of common ownership. Fourth, active funds are likely more attentive than passive ones. Corporate managers may therefore be more responsive to their preferences (Gilje, Gormley, and Levit (Reference Gilje, Gormley and Levit2020)).

Our analysis proceeds in 3 steps. First, we derive a fund-level common ownership (CO) measure based on the existing theoretical literature (Rotemberg (Reference Rotemberg1984), O’Brien and Salop (Reference O’Brien and Salop2000), and Backus et al. (Reference Backus, Conlon and Sinkinson2021)). This measure is a weighted average of competitors’ pairwise “profit weights” in a fund’s portfolio (see detailed definition in Section II.B). It quantifies the internalization of competitors’ future profits for the portfolio firms owned by a fund. In particular, the measure captures not only the profit considerations among competing portfolio firms but also the incentive and ability of a fund to influence firms’ corporate policy. Therefore, if firms incorporate common owners’ preferences, this measure should correlate positively with common owners’ portfolio profits.

We find that actively managed equity funds with higher CO outperform their peers with lower CO, based on both factor- and benchmark-adjusted returns. In portfolio analyses, we find that the abnormal raw return of the top CO decile portfolio is 1%–2% higher per year than that of the bottom CO portfolio. The annualized Sharpe ratio is also higher. Corroborating this evidence, we find similar results using Fama–MacBeth and panel regressions controlling for fund characteristics. Our further investigation uncovers three patterns in the underlying mechanism: i) high-CO funds’ superior performance comes from CO positions outperforming non-CO holdings, ii) the effect is stronger in industries with higher overall common ownership intensity, and iii) the effect is particularly strong when held firms are in concentrated industries, where funds could more effectively influence competitive outcomes.

Our results remain robust using a matched sample of funds with similar characteristics. We also mitigate concerns over several alternative explanations, including portfolio industry concentration, common stock selection, and funds’ tendency to select firms with high common ownership. Specifically, we conduct the following three tests. First, using the Fama–MacBeth regression approach, we disentangle the common ownership effect from the effect of portfolio industry concentration as documented by Kacperczyk, Sialm, and Zheng (Reference Kacperczyk, Sialm and Zheng2005). Second, by controlling for the average number of institutional investors of portfolio firms, we further establish that the outperformance is not compromised by the fund managers’ abilities that result in commonly selecting high-performing firms. Third, using a modified measure that captures funds’ asset allocation to firms with different levels of common ownership, we show that the results are not likely to be driven by fund managers’ tendency to select firms with high firm-level common ownership. In addition, the performance of active funds with high common ownership is fairly persistent over time.Footnote 5 In robustness tests, we further show that these results are robust to two variants of CO measures, alleviating concerns about the definition of competitors and the functional form of a firm’s objective function.Footnote 6

Our second analysis studies whether active fund managers would have an incentive to adopt a high-CO strategy. If fund managers must expend costly efforts to monitor portfolio companies and influence policy to outperform, they should be compensated. A fund manager’s objective function is the product of fund size and fees (Berk and Green (Reference Berk and Green2004)). CO can affect fund manager payoffs through fees and flows. We find that funds with higher CO have higher expense ratios and management fees. However, we do not find strong empirical evidence relating CO to average fund flows.Footnote 7 A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that a 1-standard-deviation increase in CO raises a fund manager’s total compensation by about $333,000 over 5 years (excluding flow effects). This amounts to 17.4% of the median compensation of $1.92 million. Including performance-related flows would modestly raise the estimate.

Finally, we study whether high-CO funds are active monitors and whether they vote in line with maximizing their payoffs and supporting corporate policies that potentially soften competition. Edmans, Levit, and Reilly (Reference Edmans, Levit and Reilly2019) show that if common owners do not threaten to exit but instead express their preferences through their “voice,” they are more likely to be active monitors. High-CO funds appear to be active monitors following the definition in Iliev and Lowry (Reference Iliev and Lowry2015). That is, they tend to disagree with the leading proxy advisor’s (Institutional Shareholder Services [ISS]) recommendations and rely less on ISS recommendations when voting. In addition, funds with higher CO are more likely to vote against proposals increasing executives’ stock or options that tend to increase their pay-performance sensitivity. We also find that they are more likely to support directors who hold an existing directorship with industry peers of the focal firm. Shared director connections have been empirically documented to potentially transmit peer effects, like changes in corporate policy in response to higher hedge fund activism threats (Gantchev, Gredil, and Jotikasthira (Reference Gantchev, Gredil and Jotikasthira2019)).

In brief, we find that funds with higher CO tend to outperform and charge higher fees while still delivering alpha to their investors. These funds also vote for corporate policies consistent with the common ownership hypothesis. However, we do not establish causal relationships. For instance, high-CO active funds may have informational advantages about their portfolio firms, which could affect both returns and voting. Still, we provide evidence suggesting that this channel is less likely. Nonetheless, relative to the existing academic literature, our findings contribute twofold. First, our study contributes to the broad literature on the cross section of mutual fund performance. Previous literature documents many factors or strategies that drive the variation in the cross section of mutual fund performance.Footnote 8 However, to the best of our knowledge, no study relates the common ownership facet of funds’ strategies to performance and fund managers’ payoffs. Second, we contribute to the growing literature on common ownership. The extant literature primarily focuses on the effect of common ownership on product-market outcomes at the firm or industry level.Footnote 9 A notable exception is Lewellen and Lewellen (Reference Lewellen and Lewellen2022), who examine management fees charged by institutional shareholders and conclude that institutional shareholders gain modestly from common ownership in the most concentrated industries. Focusing on actively managed equity mutual funds, we find that funds holding product-market competitors earn higher abnormal returns. Moreover, we study payoffs to mutual fund managers and their incentives for adopting common ownership strategies. Our findings on both mutual fund returns and voting behavior also relate to the literature on institutional investor corporate governance, such as He and Huang (Reference He and Huang2017), who find that common institutional ownership facilitates active forms of product-market coordination, such as joint ventures, resource sharing, and coordination of research and development expenditures.

II. Empirical Framework and Data

A. Hypotheses

The theoretical foundation for our approach comes from Rotemberg (Reference Rotemberg1984), which provides a framework where firms with common owners balance the interests of various shareholders, incorporating competitors’ profits into their objective functions. However, the implications for market outcomes remain theoretically ambiguous. For instance, López and Vives (Reference López and Vives2019) derive that common ownership can increase innovation and profits under certain conditions, while Azar and Vives (Reference Azar and Vives2021) distinguish between intra-industry common ownership (which may reduce competition) and inter-industry common ownership (which may enhance welfare). Moreover, common owners may be unable or unwilling to promote anticompetitive behavior either because such actions may violate legal or regulatory constraints or because large, diversified funds (which are more likely to be common owners) have limited incentives or capacity to engage in firm-specific product-market decisions.

Previous papers empirically studying the effect of common ownership on market-level outcomes have reported evidence suggesting anticompetitive effects. Azar et al. (Reference Azar, Schmalz and Tecu2018) find that common ownership among airlines was associated with higher ticket prices, and He and Huang (Reference He and Huang2017) document increased market share and reduced product-market competition following institutional cross-ownership events. However, subsequent methodological critiques have raised questions about identification strategies and measurements used. Koch et al. (Reference Koch, Panayides and Thomas2021) challenge the robustness of earlier airline industry findings, highlighting potential confounds in market structure analysis, Lewellen and Lowry (Reference Lewellen and Lowry2021) identify limitations in empirical approaches used to establish causal relationships between institutional ownership patterns and product-market outcomes, and Dennis, Gerardi, and Schenone (Reference Dennis, Gerardi and Schenone2022) demonstrate that accounting for route-specific demand factors materially affects inferences about common ownership’s competitive effects in airline prices.

The empirical impact of common ownership on firm behavior and market outcomes remains an open question. However, essentially all papers rely on a common premise: the payoff to common owners increases when firms consider these owners’ broader portfolio interests. Therefore, given the methodological challenges in the empirical literature, we take a different approach to studying common ownership. Rather than attempting to establish causal effects on product-market competition—a task that has proven difficult, given the lack of plausibly exogenous variation—we analyze the behavior of mutual funds with varying levels of common ownership, focusing specifically on their performance outcomes and governance decisions. This approach allows us to document systematic patterns in institutional investor conduct and incentives.

Our first hypothesis tests whether active fund managers with common ownership positions achieve superior returns for themselves and their investors. Higher returns from CO strategies could indicate that these funds encourage portfolio firms to behave anticompetitively. Furthermore, such outperformance could create a self-reinforcing cycle: investors allocate more capital to high-CO funds, strengthening fund managers’ incentives to engage actively with firm management. However, the plausibility of this mechanism has been questioned in the literature. Common owners may be unwilling or unable to support anticompetitive practices due to various reasons. First, as agents, fund managers face inherent conflicts of interest (e.g., Agarwal, Gay, and Ling (Reference Agarwal, Gay and Ling2014), Bebchuk, Cohen, and Hirst (Reference Bebchuk, Cohen and Hirst2017), and Cohen, Coval, and Pastor (Reference Cohen, Coval and Pastor2005)), and broker-sold active funds typically have weaker incentives to generate alpha (Guercio and Reuter (Reference Guercio and Reuter2014)), potentially discouraging efforts to pursue CO benefits. Second, implementing CO strategies also involves costly managerial effort and possible legal risks, which must be weighed against potential gains, given that manager compensation depends on both fund size and fees (Berk and Green (Reference Berk and Green2004)). Finally, even if CO strategies produce short-term outperformance, such gains could diminish over time as other investors adopt similar approaches. Moreover, alternative explanations—such as portfolio industry concentration, common stock selection, or CO stock-picking—may also drive the observed outperformance of high-CO funds.

To address the concerns above, we proceed as follows: First, we develop a fund-level CO measure, capturing the extent to which funds internalize the future profits of competing firms in their portfolios. Using this measure, we design tests to evaluate whether the superior returns observed in high-CO funds can be attributed to a common ownership channel. Specifically, we conduct three distinct analyses: i) comparing returns of CO holdings directly against non-CO holdings within the same fund, ii) examining the impact of industry-level common ownership intensity on the relationship between fund CO and returns, and iii) exploring whether the relationship is stronger in concentrated industries where potential anticompetitive influence might be greater. Furthermore, we also investigate whether economic incentives exist for managers to adopt CO strategies by examining how fund-level CO relates to fund fees and manager compensation. Finally, to rule out alternative explanations, we implement matched-sample analyses and explicitly control for portfolio industry concentration, common stock selection, or the tendency to select firms with high common ownership.

Our second hypothesis examines whether mutual fund managers exercise their governance rights in ways consistent with common ownership theory. For example, Shekita (Reference Shekita2022) documents 30 cases of interventions by common owners, all of which required not only the attention of the common owner but also the active participation in engaging with corporate managers. This analysis requires linking financial payoffs with fund managers’ voting patterns, focusing on votes that could facilitate inter-firm coordination or affect managerial incentives. Specifically, we test whether voting behavior is consistent with theoretical predictions that common owners would reduce executive pay-performance sensitivity (Antón et al. (Reference Antón, Ederer, Giné and Schmalz2023)). While we do not establish causality, systematic patterns in voting behavior provide evidence of how funds exercise their governance rights under common ownership.

B. Derivation of Fund-Level Measure of Common Ownership

We derive our fund-level measure of common ownership by building upon the established firm-level measure of common ownership used in the existing literature. We begin with the concept of profit weights between firms, then extend this to create fund-specific profit weights, and finally aggregate these into our fund-level common ownership measure.

1. Review of Firm-Level Common Ownership

The literature typically measures common ownership based on how much a firm considers competitors’ profits in its decision-making. For a shareholder

![]() $ s $

of the firm

$ s $

of the firm

![]() $ m $

, we denote her cash flow right as

$ m $

, we denote her cash flow right as

![]() $ {\beta}_{s,m} $

, which equals the ratio of shares she owns to the total number of shares outstanding in firm

$ {\beta}_{s,m} $

, which equals the ratio of shares she owns to the total number of shares outstanding in firm

![]() $ m $

.Footnote 10 She is considered a common owner if she holds positive stakes in both firm

$ m $

.Footnote 10 She is considered a common owner if she holds positive stakes in both firm

![]() $ m $

and its competitor n(i.e.,

$ m $

and its competitor n(i.e.,

![]() $ {\beta}_{s,m}>0 $

and

$ {\beta}_{s,m}>0 $

and

![]() $ {\beta}_{s,n}>0 $

). According to O’Brien and Salop (Reference O’Brien and Salop2000) and Backus et al. (Reference Backus, Conlon and Sinkinson2021), common owners have an incentive to maximize total portfolio profits, leading firm managers to internalize profits across firms held by the same shareholders. The weight (termed “profit weight” or

$ {\beta}_{s,n}>0 $

). According to O’Brien and Salop (Reference O’Brien and Salop2000) and Backus et al. (Reference Backus, Conlon and Sinkinson2021), common owners have an incentive to maximize total portfolio profits, leading firm managers to internalize profits across firms held by the same shareholders. The weight (termed “profit weight” or

![]() $ {\kappa}_{m,n} $

) that firm

$ {\kappa}_{m,n} $

) that firm

![]() $ m $

places on its competitor

$ m $

places on its competitor

![]() $ n $

’s profits is defined as

$ n $

’s profits is defined as

$$ {\kappa}_{m,n}=\frac{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}{\beta}_{s,n}}{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}^2}. $$

$$ {\kappa}_{m,n}=\frac{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}{\beta}_{s,n}}{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}^2}. $$

This weight represents the extent to which focal firm

![]() $ m $

incorporates competitor firm

$ m $

incorporates competitor firm

![]() $ n $

’s profits into its own objective function.Footnote 11 The numerator of equation (1) is the inner product of common ownership across all common owners, and the denominator is the focal firm

$ n $

’s profits into its own objective function.Footnote 11 The numerator of equation (1) is the inner product of common ownership across all common owners, and the denominator is the focal firm

![]() $ m $

’s ownership concentration (akin to the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index) as a scalar. Thus, this measure can be interpreted as the strength of common ownership relative to the ownership concentration of the focal firm. Theoretically, when

$ m $

’s ownership concentration (akin to the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index) as a scalar. Thus, this measure can be interpreted as the strength of common ownership relative to the ownership concentration of the focal firm. Theoretically, when

![]() $ {\kappa}_{m,n}=1 $

, firm

$ {\kappa}_{m,n}=1 $

, firm

![]() $ m $

values firm

$ m $

values firm

![]() $ n $

’s profits equally to its own when maximizing its objective function.

$ n $

’s profits equally to its own when maximizing its objective function.

![]() $ {\kappa}_{m,n} $

could exceed one, indicating that firm

$ {\kappa}_{m,n} $

could exceed one, indicating that firm

![]() $ m $

places more weight on competitor

$ m $

places more weight on competitor

![]() $ n $

’s profits than its own. These profit weights are key components of the “modified HHI delta” measure used in empirical studies of common ownership, such as Azar et al. (Reference Azar, Schmalz and Tecu2018).Footnote 12

$ n $

’s profits than its own. These profit weights are key components of the “modified HHI delta” measure used in empirical studies of common ownership, such as Azar et al. (Reference Azar, Schmalz and Tecu2018).Footnote 12

2. From Firm-Level to Fund-Level Common Ownership

To derive our fund-level measure, we first consider how a specific fund

![]() $ p $

contributes to the profit weight between firms. By decomposing the numerator in equation (1), we define the pairwise profit weight

$ p $

contributes to the profit weight between firms. By decomposing the numerator in equation (1), we define the pairwise profit weight

![]() $ {\kappa}_{p,m,n} $

specific to fund

$ {\kappa}_{p,m,n} $

specific to fund

![]() $ p $

as

$ p $

as

$$ {\kappa}_{p,m,n}=\frac{\beta_{p,m}{\beta}_{p,n}}{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}^2}. $$

$$ {\kappa}_{p,m,n}=\frac{\beta_{p,m}{\beta}_{p,n}}{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}^2}. $$

This measures the value to focal firm

![]() $ m $

of a dollar of profit generated for competitor firm

$ m $

of a dollar of profit generated for competitor firm

![]() $ n $

, specifically attributable to fund

$ n $

, specifically attributable to fund

![]() $ p $

’s common ownership. Building on this, we calculate the aggregate value to firm

$ p $

’s common ownership. Building on this, we calculate the aggregate value to firm

![]() $ m $

of profits generated by all its competitors, attributable to fund

$ m $

of profits generated by all its competitors, attributable to fund

![]() $ p $

:

$ p $

:

$$ {\kappa}_{p,m}=\frac{\sum_{\forall n\ne m}{\beta}_{p,m}{\beta}_{p,n}}{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}^2}. $$

$$ {\kappa}_{p,m}=\frac{\sum_{\forall n\ne m}{\beta}_{p,m}{\beta}_{p,n}}{\sum_{\forall s}{\beta}_{s,m}^2}. $$

Specifically, the numerator of

![]() $ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

represents the inner product of fund

$ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

represents the inner product of fund

![]() $ p $

’s common ownership in focal firm

$ p $

’s common ownership in focal firm

![]() $ m $

(

$ m $

(

![]() $ {\beta}_{p,m} $

) and competitors

$ {\beta}_{p,m} $

) and competitors

![]() $ n $

(

$ n $

(

![]() $ {\beta}_{p,n} $

), with competitors identified using Hoberg–Phillips TNIC data (Hoberg and Phillips (Reference Hoberg and Phillips2016)).Footnote 13 As a scalar, the denominator represents firm

$ {\beta}_{p,n} $

), with competitors identified using Hoberg–Phillips TNIC data (Hoberg and Phillips (Reference Hoberg and Phillips2016)).Footnote 13 As a scalar, the denominator represents firm

![]() $ m $

’s ownership concentration based on all available ownership data sourced from 13F filings, 13D filings, 13G filings, and other public reports, not just fund

$ m $

’s ownership concentration based on all available ownership data sourced from 13F filings, 13D filings, 13G filings, and other public reports, not just fund

![]() $ p $

’s ownership.Footnote 14

$ p $

’s ownership.Footnote 14

Finally, we define our fund-level common ownership measure,

![]() $ {CO}_p $

, by aggregating

$ {CO}_p $

, by aggregating

![]() $ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

across all portfolio firms held by fund

$ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

across all portfolio firms held by fund

![]() $ p $

:

$ p $

:

where

![]() $ {w}_{p,m} $

represents the proportion of fund

$ {w}_{p,m} $

represents the proportion of fund

![]() $ p $

’s total portfolio value invested in firm

$ p $

’s total portfolio value invested in firm

![]() $ m $

, calculated as the product of the firm’s stock price and the number of shares held by the fund, divided by the fund’s total investment value at each quarter-end.

$ m $

, calculated as the product of the firm’s stock price and the number of shares held by the fund, divided by the fund’s total investment value at each quarter-end.

![]() $ {CO}_p $

measures the extent of common ownership within fund

$ {CO}_p $

measures the extent of common ownership within fund

![]() $ p $

’s portfolio and can be interpreted as the portfolio-weighted average value, specific to fund

$ p $

’s portfolio and can be interpreted as the portfolio-weighted average value, specific to fund

![]() $ p $

, of a dollar of profits accruing to competitors relative to a dollar of profits for the focal portfolio firms themselves. The intuition is that as common ownership increases, portfolio firms may have an incentive to reduce competition and thus potentially gain larger profits, of which common owners receive a proportion.Footnote 15

$ p $

, of a dollar of profits accruing to competitors relative to a dollar of profits for the focal portfolio firms themselves. The intuition is that as common ownership increases, portfolio firms may have an incentive to reduce competition and thus potentially gain larger profits, of which common owners receive a proportion.Footnote 15

![]() $ {CO}_p $

not only measures the consideration for profits of competing firms but also the fund’s ability and incentive to influence the policies of firm

$ {CO}_p $

not only measures the consideration for profits of competing firms but also the fund’s ability and incentive to influence the policies of firm

![]() $ m $

. Since

$ m $

. Since

![]() $ {CO}_p $

depends critically on portfolio weights, we consider it part of a fund’s investment strategy.Footnote 16

$ {CO}_p $

depends critically on portfolio weights, we consider it part of a fund’s investment strategy.Footnote 16

Our definition of fund common owners requires fund

![]() $ p $

to hold both firm

$ p $

to hold both firm

![]() $ m $

and its competitor

$ m $

and its competitor

![]() $ n $

to make

$ n $

to make

![]() $ {\sum}_{\forall n\ne m}{\beta}_{p,m}{\beta}_{p,n} $

in

$ {\sum}_{\forall n\ne m}{\beta}_{p,m}{\beta}_{p,n} $

in

![]() $ {CO}_p $

nonzero.Footnote 17 If fund

$ {CO}_p $

nonzero.Footnote 17 If fund

![]() $ p $

only holds firm

$ p $

only holds firm

![]() $ m $

without holding its competitor

$ m $

without holding its competitor

![]() $ n $

, then the incentive and the ability to facilitate coordination between firm

$ n $

, then the incentive and the ability to facilitate coordination between firm

![]() $ m $

and

$ m $

and

![]() $ n $

would be low. Even if a fund obtains outperformance by holding only one side of a pair of competitors, it is possible that fund

$ n $

would be low. Even if a fund obtains outperformance by holding only one side of a pair of competitors, it is possible that fund

![]() $ p $

simply picks stocks and free-rides on other funds holding both firms

$ p $

simply picks stocks and free-rides on other funds holding both firms

![]() $ m $

and

$ m $

and

![]() $ n $

. Therefore, our empirical analyses will seek to disentangle these effects in Section III.D. In the following analyses, CO refers to

$ n $

. Therefore, our empirical analyses will seek to disentangle these effects in Section III.D. In the following analyses, CO refers to

![]() $ {CO}_p $

from equation (4).

$ {CO}_p $

from equation (4).

The connection between our fund-level CO and industry-level common ownership (e.g., MHHI delta) has important empirical implications. If fund-level CO is merely capturing idiosyncratic fund characteristics unrelated to broader competitive effects, we would not expect the relationship between fund CO and fund performance to vary with industry-level common ownership concentration. However, if fund CO is capturing a fund’s participation in potentially anticompetitive ownership structures, then the performance benefits should be more pronounced in industries with high common ownership concentration. We test this prediction in Section III.C by examining how our fund-level CO effects vary with industry-level MHHI delta. We acknowledge that our fund-level measure captures only a single fund’s contribution to the overall common ownership structure rather than the complete industry-level common ownership central to theories of anticompetitive effects. However, this approach allows us to directly examine which funds benefit from common ownership positions and how these benefits relate to broader industry structures, thereby addressing a key premise in the common ownership hypothesis.

C. Data Sources

We construct our sample by merging fund characteristics, stockholdings, stock characteristics, and fund voting data from different databases. In our analyses, we use observations from three levels: i) fund-by-month observations to study returns and fund characteristics, ii) fund-by-year observations to study fees and active monitoring activities, and iii) fund- (or fund-family-)by-proposal to study voting behavior on specific proposals.

We obtain the fund names, monthly returns, monthly total net assets (TNA), investment objectives, and other fund characteristics from the CRSP Survivorship Bias-Free Mutual Fund Database. Following Huang, Sialm, and Zhang (Reference Huang, Sialm and Zhang2011), we identify actively managed U.S. equity mutual funds based on their objective codes and their disclosed asset compositions.Footnote 18 Because data coverage on the monthly TNA and quarterly portfolio holdings before 1999 is limited and of poor quality, our sample period spans from January 1999 to December 2018. We restrict to funds domiciled in the United States, and exclude money market funds, index funds, fixed income funds, and funds that manage less than $5 million in the previous month and those whose total equity holding in dollar value (calculated from the mutual fund holding data discussed below) is less than $5 million in a quarter. For funds with multiple share classes, we calculate the weighted average monthly fund returns by the weights of share class TNA.

We obtain mutual funds’ portfolio holdings from the Thomson Reuters Mutual Fund Holdings Database (S12) and the CRSP Mutual Fund Holdings Database. Recent studies show that the Thomson stockholdings data have problems with missing new funds after 2008, while CRSP portfolio holdings data are “inaccurate prior to the fourth quarter of 2007” (Schwarz and Potter (Reference Schwarz and Potter2016), Zhu (Reference Zhu2020)). To circumvent data quality problems, we consolidate the Thomson stockholdings data before the second quarter of 2010 with the CRSP stockholdings data on and after that quarter.Footnote 19 Beyond mutual funds’ holding data, we also consolidate comprehensive ownership data containing both institutional and individual owners, using all available 13-F filings, 13-D filings, 13-G filings, and other publicly reported ownership. We only keep firms with a minimum of 10% available aggregated ownership to circumvent the problem of missing ownership information, although our results remain robust without this restriction.Footnote 20 To tackle asynchronicities in reported holdings, we keep the stockholdings reported at each quarter-end. For those who did not report at the quarter-end, we use their most recent holding positions before each quarter-end. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the most comprehensive ownership data used for calculating common ownership.Footnote 21 To identify firm competitors, we use the Hoberg–Phillips TNIC data that provide pairwise competition linkages based on textual analysis of firms’ product information (Reference Hoberg and PhillipsHoberg and Phillips (2016)).Footnote 22 In a robustness check, we use the Fama–French 12 Industry Classification to identify industry peers.

At the stock level, we obtain stock fundamentals data from the CRSP–Compustat Merged database. The returns of the Fama–French 5 factors and the momentum factor are sourced from Kenneth French’s website. The factor returns of the q-factor model are from the Hou–Xue–Zhang q-factors data library. We study common stock held by mutual funds listed on the NYSE, Nasdaq, or AMEX stock exchanges. We restrict our sample to stocks with non-missing information on month-end prices, monthly returns, 4-digit SIC industry code, and annual net sales. Stock prices, returns, and the number of outstanding shares are sourced from CRSP. Firm fundamentals data, such as firm sales, come from Compustat.

For the fund voting analysis, we obtain fund voting data from the ISS Voting Analytics data set that includes all management and shareholder proposals for public companies in their proxy statements since 2003. For each proposal, the data set contains the information on the short description of the proposal, the type of proposal categorized using ISS’s system (ISSAgendaItemID), management and ISS recommendation, and mutual fund votes for the proposal—vote for, against, abstaining, and withholding. We follow Peter Iliev’s note to link mutual funds between ISS and CRSP and then to Thomson Reuters (see https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.psu.edu/dist/b/169215/files/2023/08/voting-link-note-v2.pdf). A total of 3,121 funds in ISS are identified during the 2003–2018 period. Because this study focuses on the proposals potentially related to competition, we keep the proposals on stock or stock option plans and elections of directors.Footnote 23

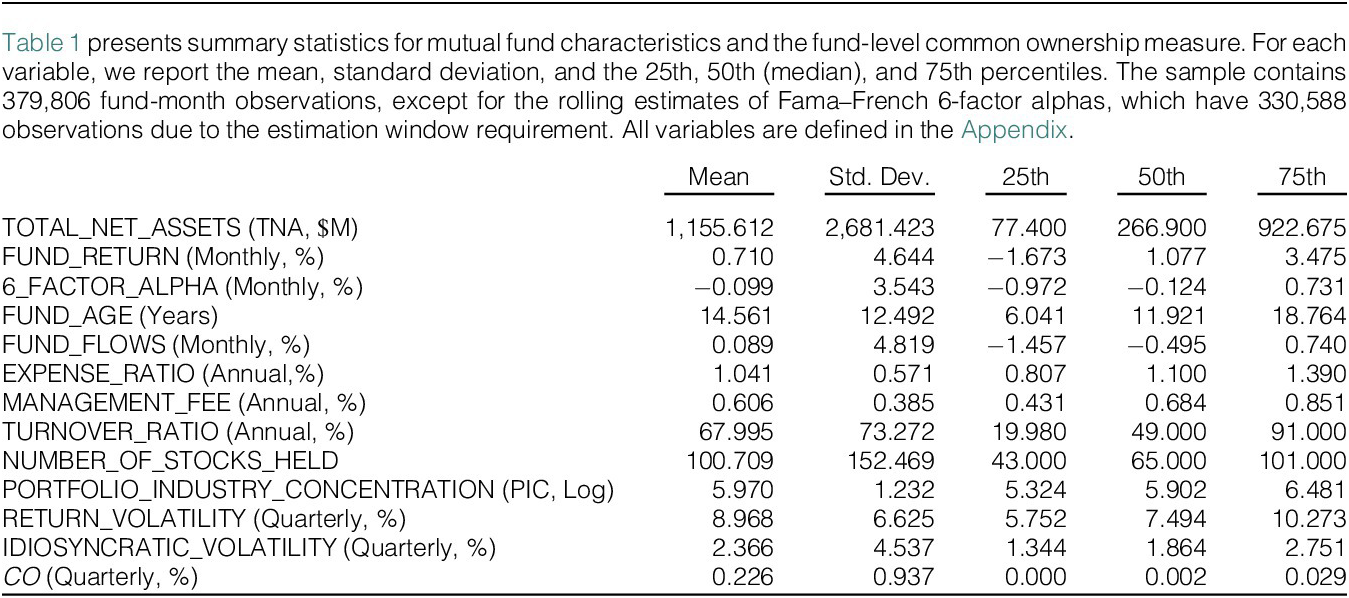

Consolidating the above data sets results in a final sample that includes 6,681 actively managed equity funds with 379,806 fund-month observations. Since we consolidate the CRSP and Thomson Reuters mutual fund data sets, 3,351 unique funds are identified in the CRSP sample and 3,332 in the TR sample. Often, a fund has two separate identifiers, one in each subsample. Table 1 reports summary statistics on CO and other fund characteristics commonly used in the mutual fund literature. All variables are defined in the Appendix.

TABLE 1 Summary Statistics

III. Common Ownership and Mutual Fund Returns

This section first describes mutual funds’ common ownership (CO) characteristics and then studies the relationship between CO and fund returns. We then address alternative explanations and potential confounders of the results.

A. Common Ownership as a Fund Strategy

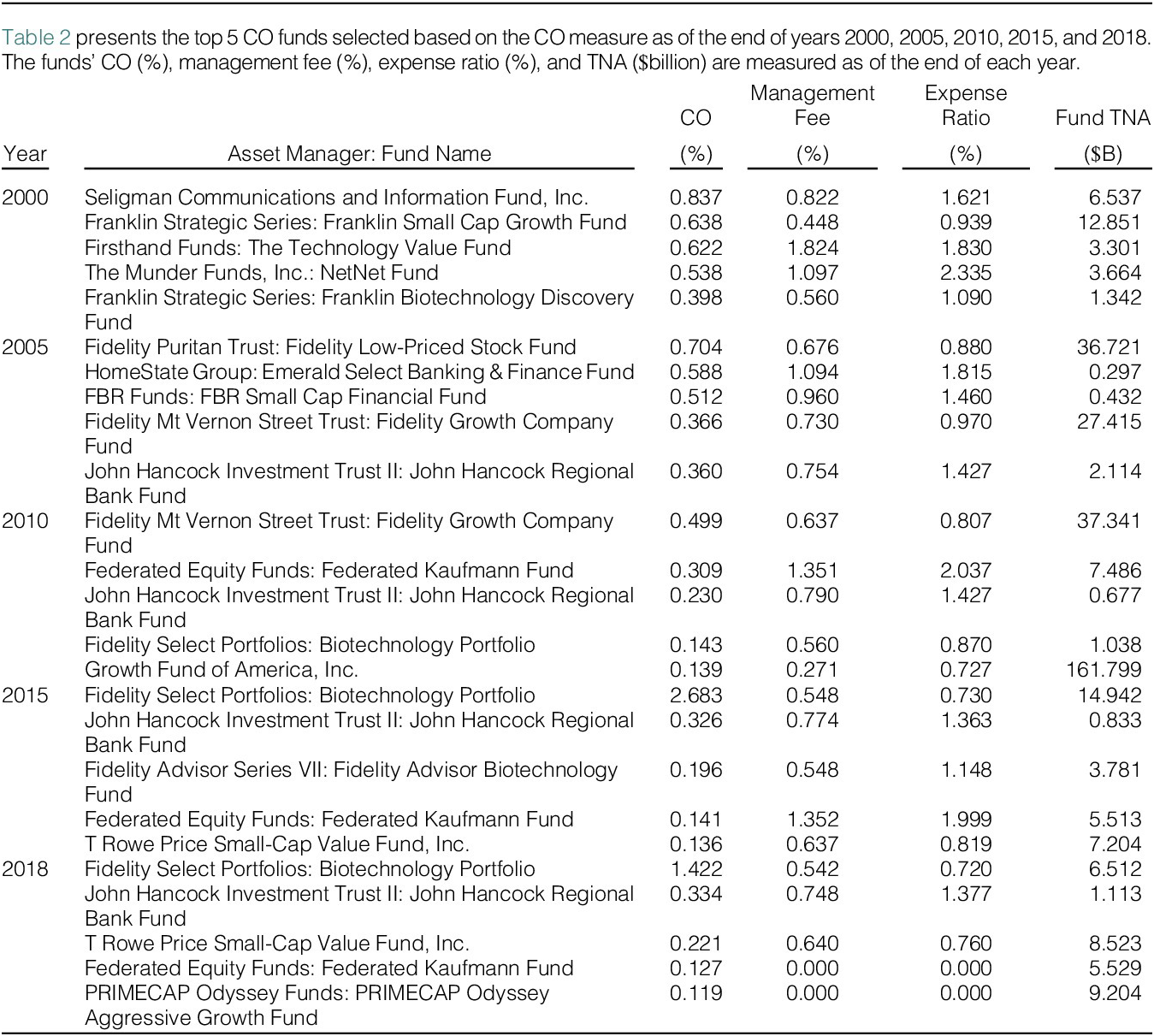

We observe a substantial variation in fund CO across U.S. actively managed equity mutual funds. The maximum CO is 7.12% after winsorization at the 99th percentile, with a mean of 0.22% and a standard deviation of 0.94%. Table 2 presents some of the top CO funds across different years in our sample.Footnote 24

TABLE 2 Top CO Funds

CO is a persistent characteristic of mutual funds: it has an autocorrelation of 0.809, driven by the extreme deciles of CO (see Supplementary Material Table B1). The table also reports that a fund in the lowest decile of CO in a quarter is over 87% likely to stay in the same decile in the next quarter. In contrast, those in the top decile are over 91% likely to stay in the same decile quarterly. Other deciles are slightly less absorbing, with between 60% and 78% likely to stay in the same decile. For example, the CO measure for Hodges Capital Small Intrinsic Value Fund, quoted in the introduction of this article, moved from below the 50th percentile in 2014 to above the 80th percentile in 2018. This allocation is consistent with the portfolio construction methodology on Hodges Capital’s site, which states that their managers may “concentrate the number of holdings in the portfolio within a certain sector during a sector pullback” (see https://hodgescapital.com/process as of July 20).

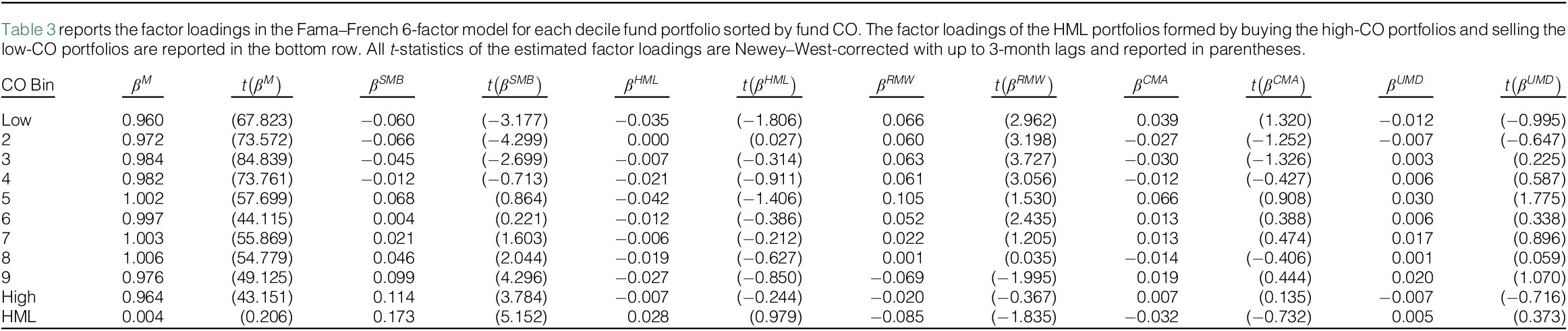

We further study the factor exposures of funds with varying levels of CO. We sort funds into decile portfolios based on their CO measure in the previous quarter and then compute the value-weighted monthly returns for each decile portfolio, as well as the high-minus-low (HML) portfolio formed by buying high-CO portfolios and selling the low-CO portfolios. Table 3 reports the Fama–French 6-factor (Fama and French (Reference Fama and French2015) with momentum) loadings of different CO decile portfolios. We find that funds with higher CO tend to have higher loadings on the size factor, with the loading on the high-minus-low CO decile portfolio reaching 0.173 (t-stat >5).Footnote 25 For these funds, we also observe a slight but statistically insignificant (at the 5% level) tilt toward value stocks and low profitability firms. These style characteristics—the size tilt, value orientation, and focus on firms with potential for profitability improvement—align with patterns documented in the activist investor literature. Brav, Jiang, Kim et al. (Reference Brav, Jiang and Kim2010) and Brav, Jiang, and Kim (Reference Brav, Jiang and Kim2015) show that activist investors typically target smaller firms with lower valuations where they can more effectively influence corporate policies and enhance profitability.

TABLE 3 Factor Loadings of Fund Portfolios

Although CO is defined based on competitors in the same industry classification, it is not primarily driven by funds specializing in a particular industry. For example, the correlation between Kacperczyk et al.’s (Reference Kacperczyk, Sialm and Zheng2005) portfolio industry concentration (PIC) measure and CO is 0.12. Removing sector funds from our analyses does not qualitatively alter the summary statistics and empirical results. Therefore, although funds may not allocate their portfolios to hit a particular value of CO, funds’ common ownership position is a persistent and unique fund characteristic that is not accounted for in traditional factor exposures or standard measures of portfolio industry concentration.

B. Fund Returns

1. Portfolio Sorts

To evaluate fund performance, we use both risk- and benchmark-adjusted return measures. The former uses the 6-factor (Fama and French (Reference Fama and French2015) with momentum), Ferson and Schadt (Reference Ferson and Schadt1996), Pastor and Stambaugh (Reference Pastor and Stambaugh2003), and q-5-factor (Hou, Mo, Xue, and Zhang (Reference Hou, Mo, Xue and Zhang2021)) models to calculate alpha. For example, the Fama–French 6-factor alpha is the intercept from the following time-series regression:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}{r}_{p,t}-{r}_t^f={\alpha}_p+{\beta}^M\left({r}_t^M-{r}_t^f\right)+{\beta}^S{SMB}_t+{\beta}^H{HML}_t+{\beta}^R{RMW}_t\\ {}\hskip1.5em +\hskip0.35em {\beta}^C{CMA}_t+{\beta}^U{UMD}_t+{\varepsilon}_{p,t},\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}{r}_{p,t}-{r}_t^f={\alpha}_p+{\beta}^M\left({r}_t^M-{r}_t^f\right)+{\beta}^S{SMB}_t+{\beta}^H{HML}_t+{\beta}^R{RMW}_t\\ {}\hskip1.5em +\hskip0.35em {\beta}^C{CMA}_t+{\beta}^U{UMD}_t+{\varepsilon}_{p,t},\end{array}} $$

where

![]() $ {r}_{p,t} $

is the return in month

$ {r}_{p,t} $

is the return in month

![]() $ t $

for fund portfolio

$ t $

for fund portfolio

![]() $ p $

,

$ p $

,

![]() $ {r}_t^f $

is the Treasury-bill rate in month

$ {r}_t^f $

is the Treasury-bill rate in month

![]() $ t $

,

$ t $

,

![]() $ {r}_t^M $

is the value-weighted stock market return in month

$ {r}_t^M $

is the value-weighted stock market return in month

![]() $ t $

, and

$ t $

, and

![]() $ {SMB}_t $

,

$ {SMB}_t $

,

![]() $ {HML}_t $

,

$ {HML}_t $

,

![]() $ {RMW}_t $

,

$ {RMW}_t $

,

![]() $ {CMA}_t $

, and

$ {CMA}_t $

, and

![]() $ {UMD}_t $

correspond to the Fama–French size, value, profitability, investment, and momentum factors, respectively.Footnote 26 Using the Morningstar benchmark data, we calculate the benchmark-adjusted returns as

$ {UMD}_t $

correspond to the Fama–French size, value, profitability, investment, and momentum factors, respectively.Footnote 26 Using the Morningstar benchmark data, we calculate the benchmark-adjusted returns as

where the indices follow from equation (5) and

![]() $ {r}_t^{BM(p)} $

is the return of the benchmark identified by Morningstar for fund portfolio

$ {r}_t^{BM(p)} $

is the return of the benchmark identified by Morningstar for fund portfolio

![]() $ p $

. For all these analyses, standard errors are Newey–West-corrected up to 3 lags, allowing for autocorrelation in returns for up to 3 months.

$ p $

. For all these analyses, standard errors are Newey–West-corrected up to 3 lags, allowing for autocorrelation in returns for up to 3 months.

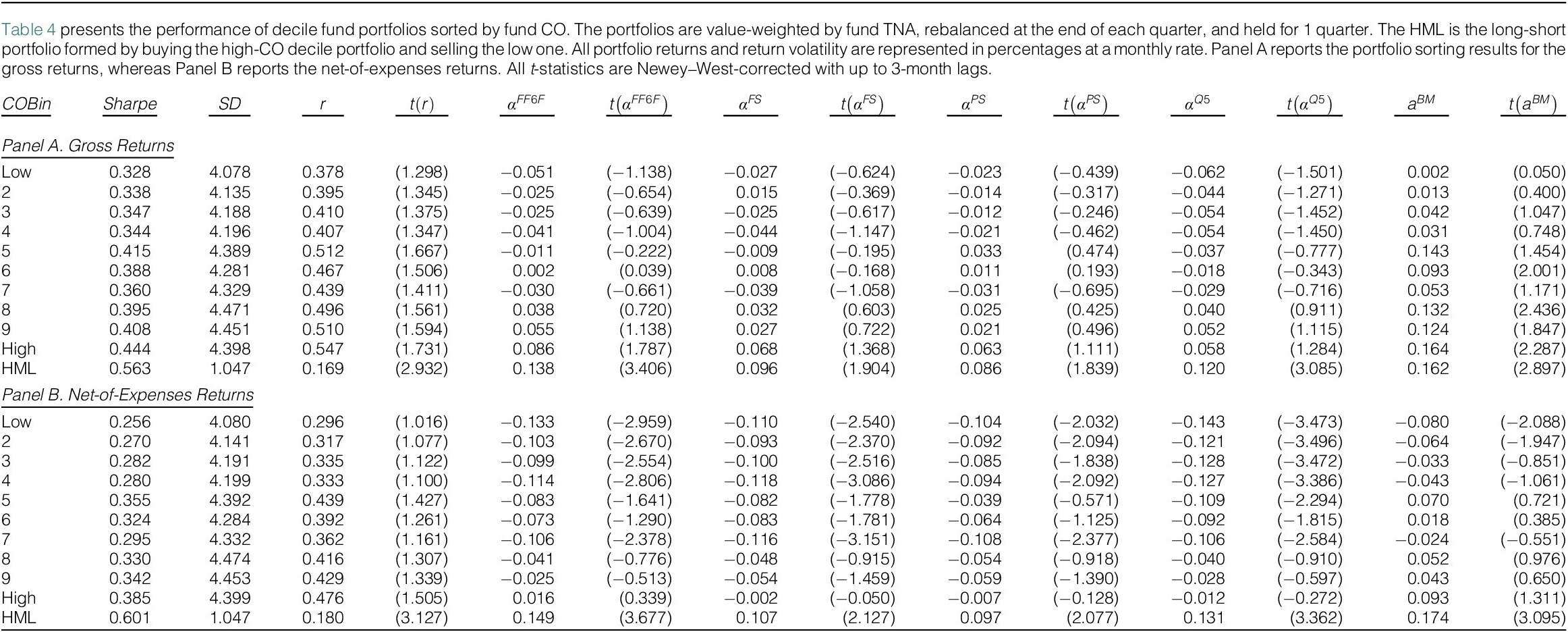

At the beginning of each quarter, we sort decile portfolios based on their most recent quarterly CO measures. We then compute the value-weighted risk- and benchmark-adjusted monthly fund returns in the next quarter using the aforementioned models. Table 4 reports the results of portfolio sorting.

TABLE 4 Portfolio Sorting

Panel A of Table 4 reports that U.S. actively managed equity mutual funds with a larger degree of common ownership exhibit better gross performance. The adjusted returns of funds in the top decile of CO are 1.08%1.92% per annum (9–16 BPS per month) greater than those in the bottom decile of CO. Although the volatility of portfolio returns is higher, the overall annualized Sharpe ratio of high-CO funds is also 0.11 higher than those with low CO. Panel B documents that the higher gross returns also appear to flow through to higher net-of-fee returns. To visualize the performance history, Figure 1 shows the cumulative returns of the CO portfolios throughout our sample period.

FIGURE 1 Time-Series Plots

Figure 1 presents the cumulative returns of top and bottom decile fund portfolios formed based on funds’ common ownership (CO, as defined in Section II.B). The portfolios are value-weighted by fund TNA, rebalanced at the end of each quarter, and held for one quarter. The HML is the long-short portfolio formed by buying the high-CO decile portfolio and selling the low one. Graph A shows the cumulative raw returns of the high-CO (green line) and low-CO (red line) portfolios from 1999 to 2018. Graph B shows the cumulative raw returns for the HML portfolio over the same period.

For robustness, we consider three alternative measures of funds’ common ownership, all detailed in the Supplementary Material. We continue to find a positive relationship between active funds’ performance and their common ownership positions.Footnote 27

2. Regression Analysis

In this analysis, we use Fama–MacBeth regression specifications that control for mutual fund characteristics that may be associated with fund performance using the following specification:

where

![]() $ {CO}_{p,t-1} $

is the measure of common ownership of fund

$ {CO}_{p,t-1} $

is the measure of common ownership of fund

![]() $ p $

in the previous quarter-end,

$ p $

in the previous quarter-end,

![]() $ {Z}_{p,t-1} $

is a matrix of fund control variables, including lagged 1-month log TNA, lagged 1-year expense (EXPENSE

$ {Z}_{p,t-1} $

is a matrix of fund control variables, including lagged 1-month log TNA, lagged 1-year expense (EXPENSE

![]() $ \_ $

RATIO), lagged 1-year turnover (TURNOVER

$ \_ $

RATIO), lagged 1-year turnover (TURNOVER

![]() $ \_ $

RATIO), lagged 1-month flows (FUND

$ \_ $

RATIO), lagged 1-month flows (FUND

![]() $ \_ $

FLOW), lagged 1-year age (FUND

$ \_ $

FLOW), lagged 1-year age (FUND

![]() $ \_ $

AGE), and lagged 1-month net-of-fee raw returns (FUND

$ \_ $

AGE), and lagged 1-month net-of-fee raw returns (FUND

![]() $ \_ $

RETURN). The dependent variable

$ \_ $

RETURN). The dependent variable

![]() $ {r}_{p,t} $

is either funds’ monthly gross or net-of-fee raw returns, Fama–French 6-factor alpha, Ferson and Schadt (Reference Ferson and Schadt1996) alpha, Pastor and Stambaugh (Reference Pastor and Stambaugh2003) alpha, q-factor alpha, or benchmark-adjusted return. The alphas are the difference between actual and expected fund returns, with factor loadings being estimated based on rolling 36-month regressions.Footnote 28

$ {r}_{p,t} $

is either funds’ monthly gross or net-of-fee raw returns, Fama–French 6-factor alpha, Ferson and Schadt (Reference Ferson and Schadt1996) alpha, Pastor and Stambaugh (Reference Pastor and Stambaugh2003) alpha, q-factor alpha, or benchmark-adjusted return. The alphas are the difference between actual and expected fund returns, with factor loadings being estimated based on rolling 36-month regressions.Footnote 28

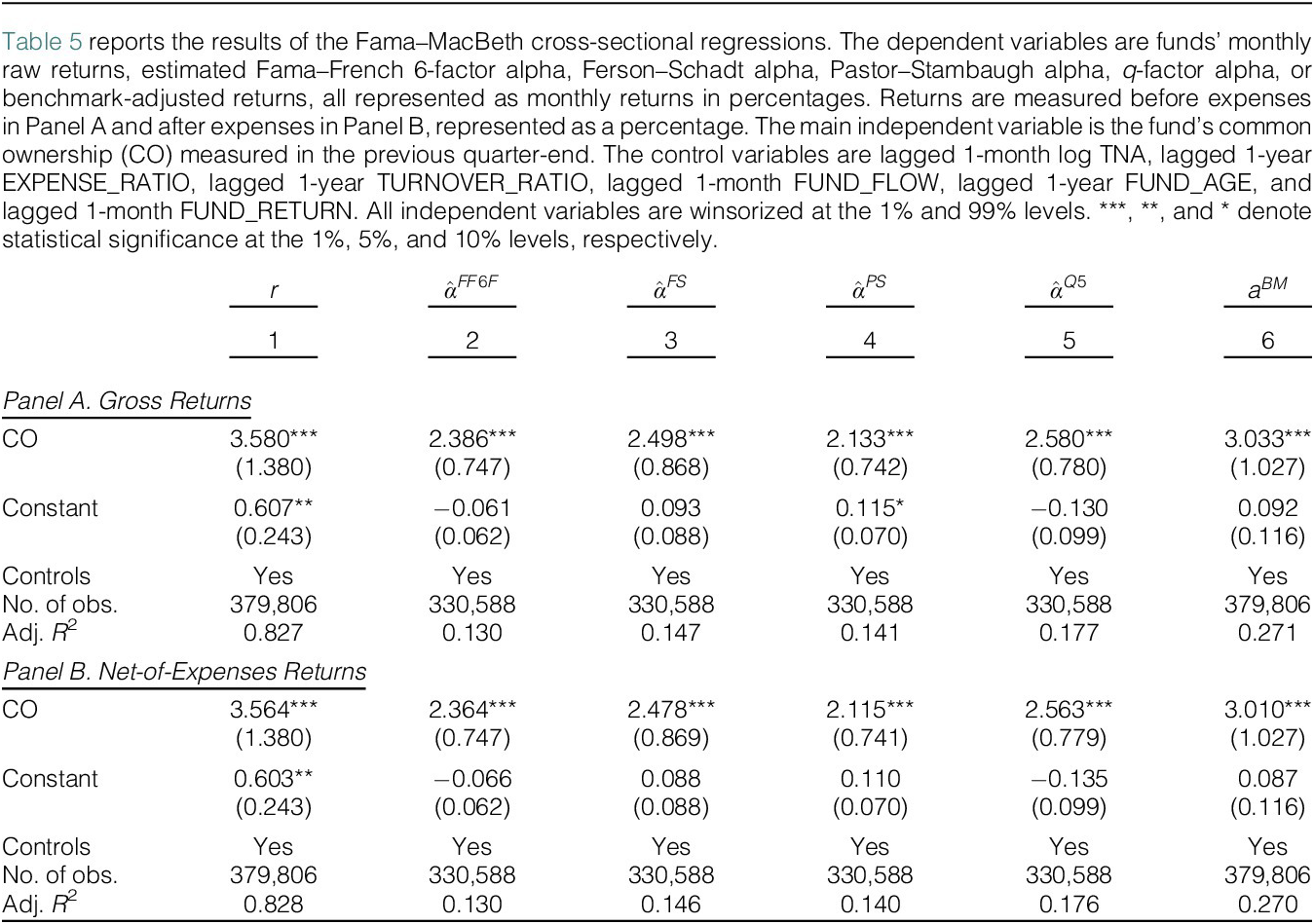

Panel A of Table 5 reports the Fama–MacBeth regression results for gross returns, and Panel B reports the results for net-of-fee returns. Across all specifications in both panels, fund performance is statistically significantly positively associated with CO after controlling for standard fund characteristics. In terms of economic magnitude, moving from funds in the lowest 10th percentile of the CO distribution to the top 90th percentile of CO (equivalent to a 3.8-standard-deviation increase in CO) is associated with a 9-basis-point (2.364

![]() $ \times $

3.8) increase in monthly Fama–French 6-factor net-of-expenses alpha in column 2 of Panel B. The improvement in alpha is meaningful, given that the average net-of-fee alpha is negative 10 BPS monthly.Footnote 29 As additional robustness, we consider panel regressions in Supplementary Material Table B4 with year-month fixed effects and standard errors clustered at the fund and year levels. We find quantitatively and qualitatively similar results.

$ \times $

3.8) increase in monthly Fama–French 6-factor net-of-expenses alpha in column 2 of Panel B. The improvement in alpha is meaningful, given that the average net-of-fee alpha is negative 10 BPS monthly.Footnote 29 As additional robustness, we consider panel regressions in Supplementary Material Table B4 with year-month fixed effects and standard errors clustered at the fund and year levels. We find quantitatively and qualitatively similar results.

TABLE 5 Fama–MacBeth Regression

Overall, the results in the regression approach are consistent with those in the portfolio sorts. Notably, funds with higher CO tend to have higher gross and net-of-fee returns. These findings suggest that not only do funds with higher CO measure tend to do better in terms of average returns and Sharpe ratio, but they also share the gains with their end investors.

C. Drivers of the CO-Performance Link

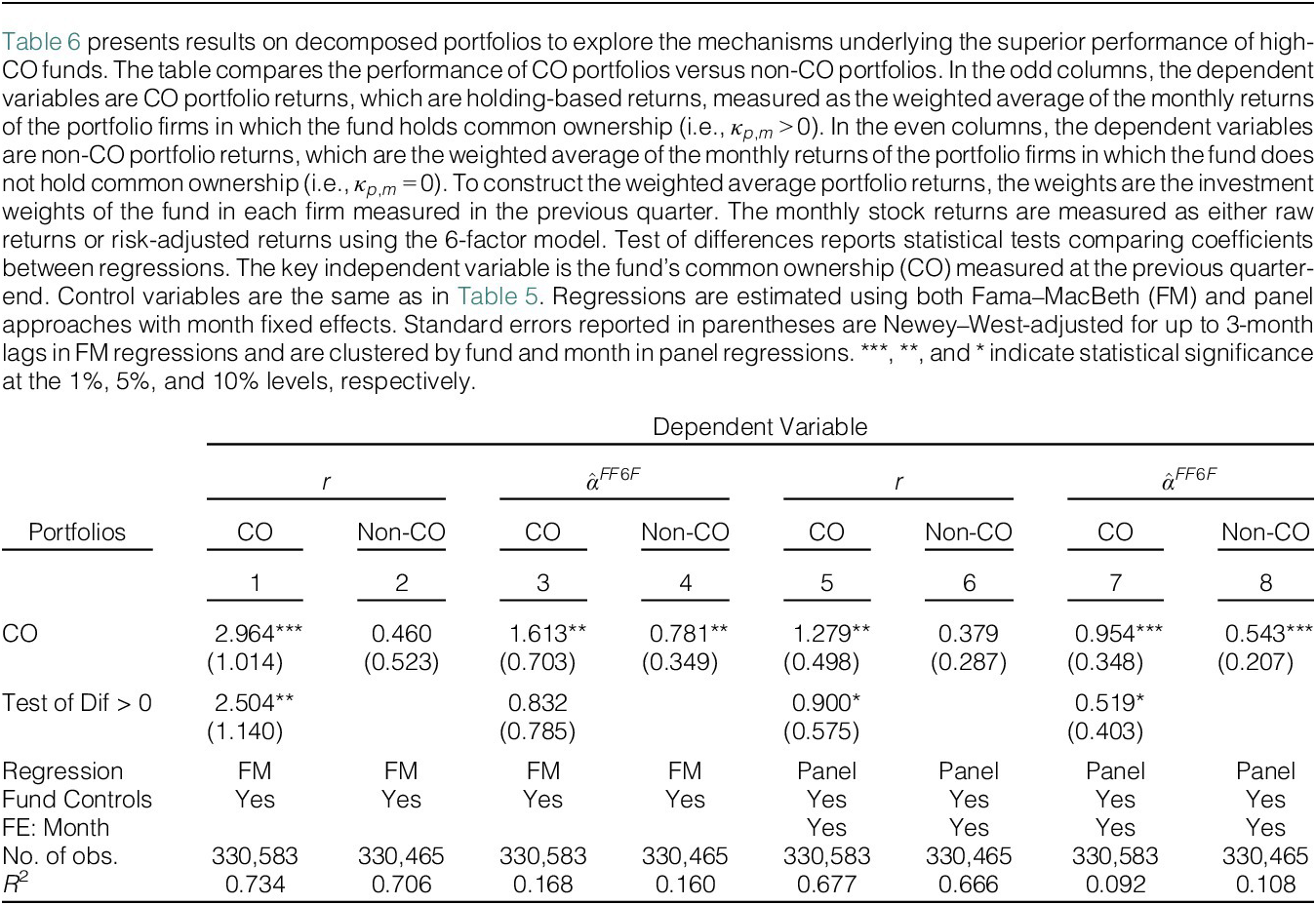

In this section, we provide three sets of results that highlight the sources of the underlying outperformance of high-CO funds, distinct from simple industry specialization. First, funds earn superior returns predominantly from positions with positive common ownership, as opposed to positions without such overlap. We decompose each fund’s portfolio into CO positions (defined as holdings with

![]() $ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

> 0) and non-CO positions (

$ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

> 0) and non-CO positions (

![]() $ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

= 0) and then compute the holding-based returns for those CO and non-CO portfolios. Applying both Fama–MacBeth and panel regression methods with appropriate controls, we find that CO positions of high-CO funds significantly outperform non-CO positions. As reported in Table 6, the estimated coefficients for CO positions range from 0.954 to 2.964 and are statistically significant at the 1% level, whereas those for non-CO positions are markedly smaller and often insignificant. This pattern, observed in both raw and risk-adjusted returns, provides evidence that the superior performance of funds is driven directly by their common ownership positions.

$ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

= 0) and then compute the holding-based returns for those CO and non-CO portfolios. Applying both Fama–MacBeth and panel regression methods with appropriate controls, we find that CO positions of high-CO funds significantly outperform non-CO positions. As reported in Table 6, the estimated coefficients for CO positions range from 0.954 to 2.964 and are statistically significant at the 1% level, whereas those for non-CO positions are markedly smaller and often insignificant. This pattern, observed in both raw and risk-adjusted returns, provides evidence that the superior performance of funds is driven directly by their common ownership positions.

TABLE 6 Decomposing Fund Portfolios: CO Positions

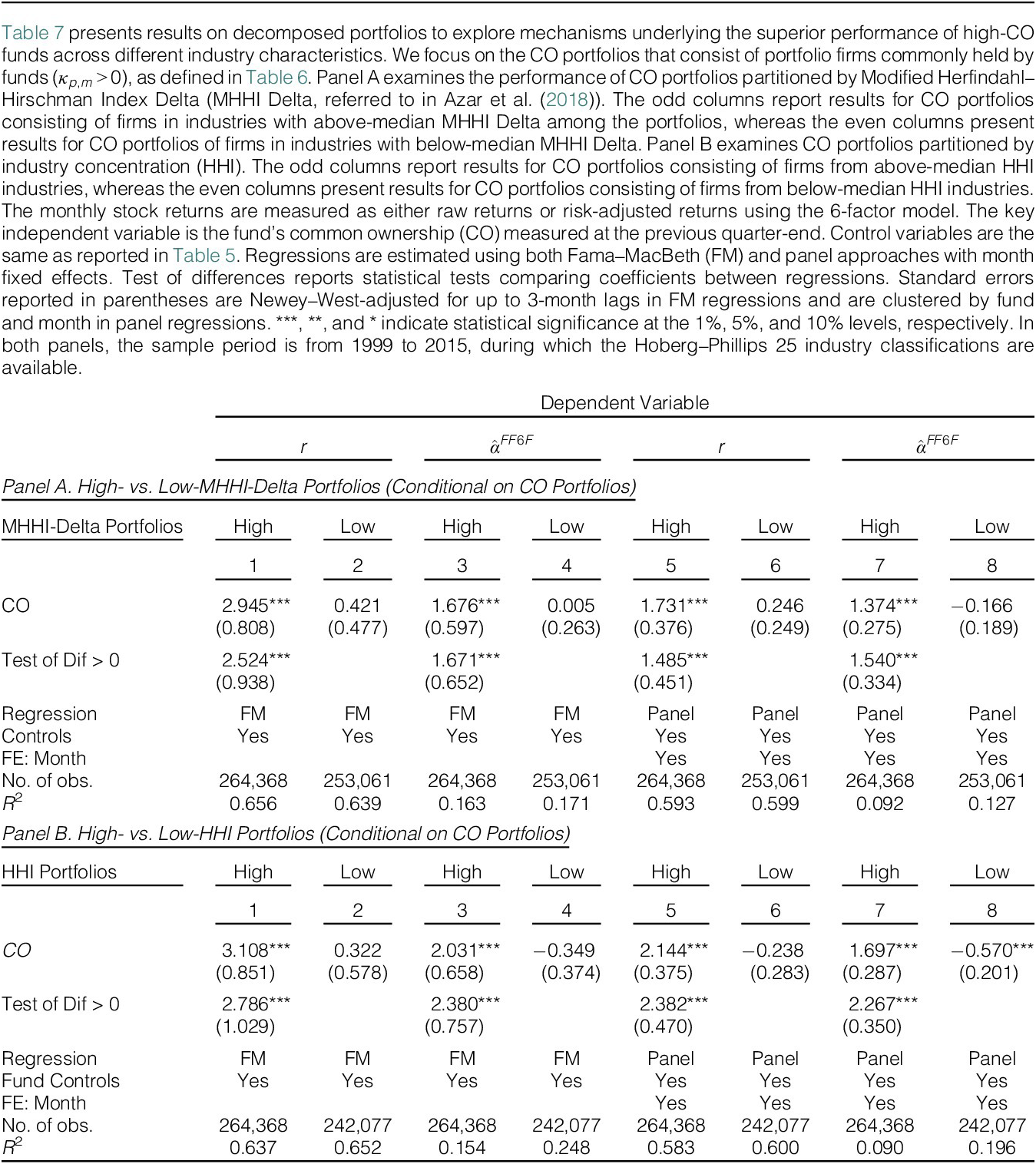

Second, our CO measure captures an individual fund’s common ownership positions, which differs from firm- and industry-level common ownership that aggregates common ownership across all shareholders’ stakes. When we stratify our sample by industry-level common ownership intensity—proxied by the MHHI delta used in Azar et al. (Reference Azar, Schmalz and Tecu2018)—we observe that for portfolio firms in industries with high MHHI delta, CO positions yield robust and economically significant coefficients (ranging from 1.374 to 2.945, as reported in Panel A of Table 7). In contrast, these effects are substantially muted in industries with low MHHI delta. The differences between the coefficients on CO from the two regressions are statistically significant at the 1% level across all specifications. This finding shows that the benefits of CO are contingent on a broader ownership network that collectively influences industry competitive dynamics.Footnote 30

TABLE 7 Decomposing Fund Portfolios: Industry Concentration

Third, the effect of common ownership is further reinforced in concentrated industries, where market power enhances the ability of funds to influence competitive dynamics. Using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) based on the Hoberg–Phillips 25 text-based industry classifications to measure industry concentration, we further partition the CO positions into portfolio firms in more concentrated industries (HHI above the median in a year-month) and those in less concentrated industries (below-median HHI industries).Footnote 31 The results in Panel B of Table 7 demonstrate that the positive association between CO and fund performance is pronounced in concentrated industries, where funds can more effectively leverage their ownership positions to influence competitive outcomes. In less concentrated industries, this relationship is weaker, underscoring the importance of market structure in enhancing the anti-competitive effects of common ownership. Altogether, these findings show that CO positions are associated with superior performance through a mechanism distinct from industry effects, though the relationship is amplified in environments with high overall common ownership and certain market structures.

D. Robustness Tests

This section attempts to address omitted variable concerns on the positive relationship between fund-level common ownership positions and fund performance. First, we matched high-CO funds with low-CO funds based on 12 observable fund characteristics. Using the matched sample, we replicate the positive relationship. Then, we consider three alternative explanations that may drive our results: portfolio industry concentration effects, common selection, and funds’ tendency to select firms with high common ownership.

1. Matched Sample Analysis

To alleviate the omitted variable concerns, we first implement a matching strategy and additional robustness tests on fund performance. We match high-CO funds with low-CO funds based on 12 observable characteristics—including all variables listed in Table 1 except for CO—using propensity score matching. For each fund in the top half of the CO distribution, we identify a matched fund in the bottom half with the closest observable characteristics without replacement. The matching is conducted quarterly to ensure contemporaneous relevance and avoid look-ahead bias.

The covariate balance analysis demonstrates that treated (high-CO) and control (low-CO) funds are remarkably similar across all observable dimensions. As reported in Supplementary Material Figure B3 and Supplementary Material Table B5, none of the differences in key fund characteristics are statistically significant. This balanced matching helps mitigate concerns about selection on observables. Subsequent fund performance regressions in Supplementary Material Table B6—estimated using both Fama–MacBeth and fixed-effects models—confirm that the positive relationship between CO and performance remains robust. This holds across various performance measures, as well as across alternative matching samples based on coarsened exact matching and other characteristic combinations.

2. Alternative Explanations

Next, we evaluate three possible alternative explanations for our main finding: portfolio industry concentration (PIC), common selection (CS), and common-ownership stock picking (COSP) to ensure that the positive association between fund-level common ownership and fund performance is not driven by these confounders.

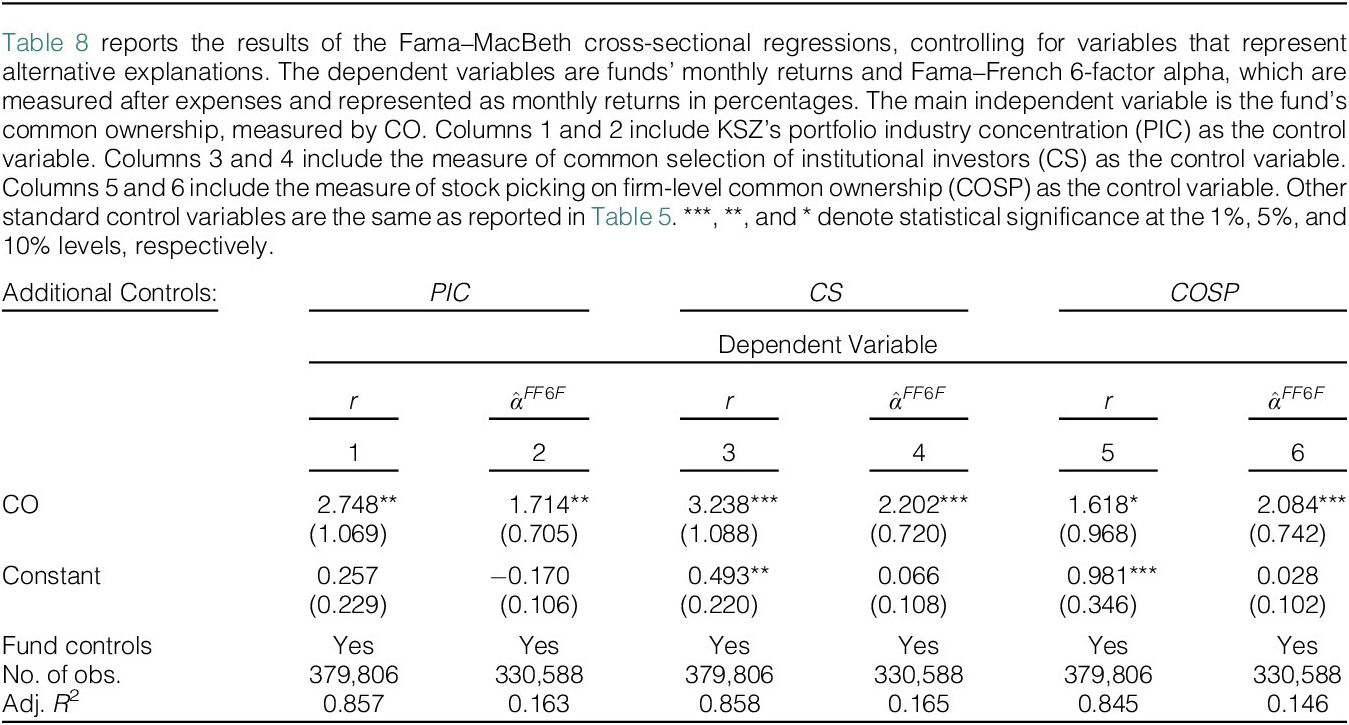

First, actively managed funds with higher CO may concentrate their holdings in particular industries where they possess informational advantages. Kacperczyk et al. (Reference Kacperczyk, Sialm and Zheng2005) demonstrate that funds with high PIC tend to outperform more diversified peers, raising the concern that our results might simply reflect a PIC effect. Importantly, however, the PIC measure—constructed across 10 industries—does not necessarily imply high-CO, nor does a high-CO strategy require industry concentration. Nevertheless, to address this, we include PIC as a control in our Fama–MacBeth regressions. As reported in columns 1 and 2 of Table 8, the coefficient of CO remains positive and statistically significant even after accounting for PIC, whose correlation with CO is below 0.20.

TABLE 8 Portfolio Industry Concentration, Common Selection, and Stock Picking

Second, the common selection (CS) effect posits that funds can co-hold stocks with superior intrinsic return potential, regardless of fund-level CO. Following Alti and Sulaeman (Reference Alti and Sulaeman2012) and Sias, Starks, and Titman (Reference Sias, Starks and Titman2006), we proxy for this effect by the portfolio-weighted change in the number of institutional investors. For each stock in the portfolio of a fund, we calculate the quarterly change in the number of institutional holders and aggregate these changes using portfolio weights.Footnote 32 Columns 3 and 4 of Table 8 include this CS measure as an additional control. Again, the positive relationship between CO and performance remains unchanged, indicating that the selection of high-quality stocks in combination does not drive our results.

Third, fund managers might simply select firms characterized by high firm-level common ownership (i.e., high profit weights) without necessarily holding stakes in their competitors. To address this concern, we construct the CO stock-picking measure (COSP):

where

![]() $ {\kappa}_m={\sum}_n{s}_n{\kappa}_{m,n}. $

We first calculate the firm-level common ownership measure

$ {\kappa}_m={\sum}_n{s}_n{\kappa}_{m,n}. $

We first calculate the firm-level common ownership measure

![]() $ {\kappa}_m $

by summing all pairwise profit weights,

$ {\kappa}_m $

by summing all pairwise profit weights,

![]() $ {\kappa}_{m,n} $

, of the firm

$ {\kappa}_{m,n} $

, of the firm

![]() $ m $

to its competitors

$ m $

to its competitors

![]() $ n $

weighted by

$ n $

weighted by

![]() $ {s}_n $

, the relative sales percentage. Then

$ {s}_n $

, the relative sales percentage. Then

![]() $ {COSP}_p $

is the sum of the profit weights for all stocks held in the portfolio

$ {COSP}_p $

is the sum of the profit weights for all stocks held in the portfolio

![]() $ p $

, weighted by the portfolio weights of the stocks

$ p $

, weighted by the portfolio weights of the stocks

![]() $ {w}_{p,m} $

. Unlike the CO measure,

$ {w}_{p,m} $

. Unlike the CO measure,

![]() $ {COSP}_p $

considers the common ownership of all shareholders (based on our comprehensive ownership data sourced from 13F, 13D, 13G, and so forth) in a firm and does not require the fund to invest in both the focal firm and its competitors. Funds that invest in a firm but do not invest in its competitors are less likely to actively engage in corporate decision-making to soften competition, as they would only gain if the focal firm outcompetes its competitors. Columns 5 and 6 of Table 8 report that the CO coefficient remains significant after controlling for funds’ stock picking on firms with varying degrees of common ownership.

$ {COSP}_p $

considers the common ownership of all shareholders (based on our comprehensive ownership data sourced from 13F, 13D, 13G, and so forth) in a firm and does not require the fund to invest in both the focal firm and its competitors. Funds that invest in a firm but do not invest in its competitors are less likely to actively engage in corporate decision-making to soften competition, as they would only gain if the focal firm outcompetes its competitors. Columns 5 and 6 of Table 8 report that the CO coefficient remains significant after controlling for funds’ stock picking on firms with varying degrees of common ownership.

Although our robustness tests rule out the three alternative explanations, our analysis remains inherently correlational and cannot establish that common ownership causally reduces competition or increases fund returns. Although our results align with theoretical predictions—such as greater CO effects for portfolio firms in industries with high overall common ownership and concentration—we cannot entirely rule out alternative mechanisms. Yet, any viable competing explanation would need to satisfy three stringent criteria: i) produce superior returns at the individual position level (CO vs. non-CO holdings), ii) interact positively with industry-level common ownership intensity (MHHI delta), and iii) be amplified in highly concentrated industries (HHI). Absent these features, alternative theories are unlikely to reproduce the cross-sectional and within-fund patterns we observe. Establishing causality will require future research that exploits exogenous variation in CO or directly measures changes in competitive behavior.

E. Return Persistence and Implementation Barriers

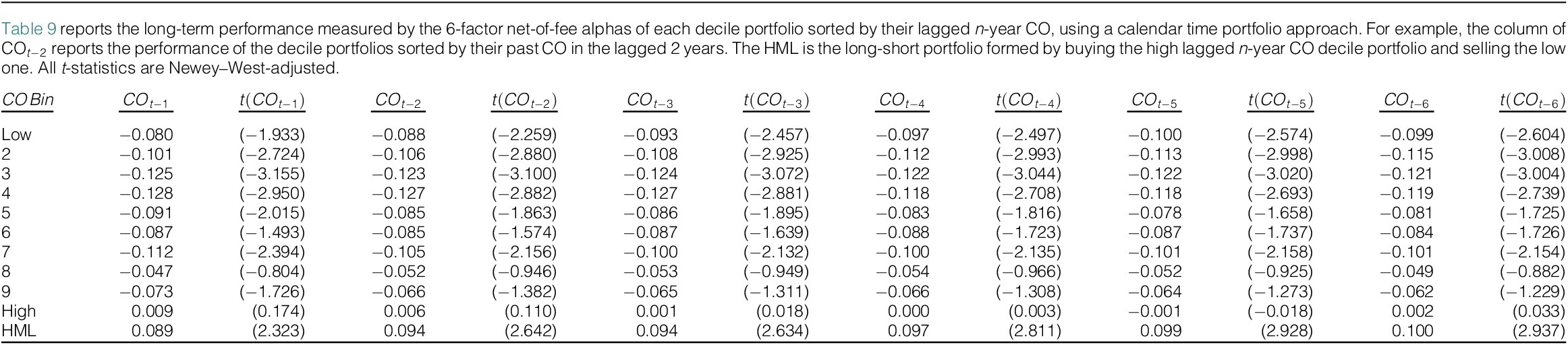

Our last analysis relating CO and fund performance examines whether the persistence in alphas aligns with the persistence in CO, as discussed in Section III.A. Using the portfolio sort analysis, we study the long-term performance of CO decile portfolios with varying levels of past CO, ranging from 1 to 6 years. Table 9 reports the results.

TABLE 9 Persistence

We find that funds with high CO outperform those with low CO for at least 6 years after forming the portfolios. The persistence in performance, coupled with the persistence in fund CO positions, shows a strategy that is profitable yet not widely replicated. Several frictions may constrain wider adoption of CO strategies. First, effective implementation requires specialized governance expertise and engagement resources to monitor and influence multiple portfolio firms. Second, our measure captures meaningful ownership overlap across competitors, necessitating substantial position sizes that smaller funds may be unable to accumulate. Third, regulatory scrutiny from antitrust authorities increases compliance costs and legal risks. Finally, business relationships between institutional investors and portfolio companies may create conflicts that constrain governance engagement (Brickley, Lease, and Smith (Reference Brickley, Lease and Smith1988)). These barriers may explain why CO strategies remain profitable over extended periods without being arbitraged away. If fund managers overcome these hurdles, they should be compensated accordingly. We investigate this compensation question next by examining the incentives of fund managers to adopt CO strategies.

IV. Fund Manager Payoffs

In this section, we study how CO relates to fund manager payoffs. To do so, we employ the framework from Berk and Green (Reference Berk and Green2004) and consider the first-order effects of fund managers’ payoffs from management fees. Since high-CO funds earn positive gross and net-of-fee alphas, we next study whether fund managers also share in the surplus by charging higher fees. Then, taking the results from fund returns and fees together, we conduct a back-of-the-envelope calculation to estimate the relationship between CO and fund managers’ compensation.

A. Fund Fees

To study the differences in fees, we use a panel regression with fund-by-year observations with the following specification:

where

![]() $ p $

indexes a fund,

$ p $

indexes a fund,

![]() $ j(p) $

is the fund family, and

$ j(p) $

is the fund family, and

![]() $ t $

indexes a year. The dependent variables are either fund expense ratios or management fees in year

$ t $

indexes a year. The dependent variables are either fund expense ratios or management fees in year

![]() $ t $

. The control variables in

$ t $

. The control variables in

![]() $ {X}_{p,t-1} $

follow those in equation (7). In addition, we include fund family-by-year fixed effects

$ {X}_{p,t-1} $

follow those in equation (7). In addition, we include fund family-by-year fixed effects

![]() $ {\alpha}_{j(p),t} $

to account for time-varying fund family policies (e.g., Gil-Bazo and Ruiz-Verdú (Reference Gil-Bazo and Ruiz-Verdú2009), Guercio and Reuter (Reference Guercio and Reuter2014), and Hortaçsu and Syverson (Reference Hortaçsu and Syverson2004)). Standard errors are clustered by both fund and year, allowing for shocks to fees that commonly affect all funds and autocorrelated shocks within a fund through time.

$ {\alpha}_{j(p),t} $

to account for time-varying fund family policies (e.g., Gil-Bazo and Ruiz-Verdú (Reference Gil-Bazo and Ruiz-Verdú2009), Guercio and Reuter (Reference Guercio and Reuter2014), and Hortaçsu and Syverson (Reference Hortaçsu and Syverson2004)). Standard errors are clustered by both fund and year, allowing for shocks to fees that commonly affect all funds and autocorrelated shocks within a fund through time.

Table 10 reports that, after controlling for time-varying fund and fund-family characteristics, CO is positively associated with expense ratios and management fees—both in the cross section (columns 1 and 3) and within the fund family (columns 2 and 4). Economically, a 1-standard-deviation increase in fund CO is associated with 4.38 BPS (4.673

![]() $ \times $

0.94%) higher expense ratios and 2.34 BPS (2.497

$ \times $

0.94%) higher expense ratios and 2.34 BPS (2.497

![]() $ \times $

0.94%) higher management fees.

$ \times $

0.94%) higher management fees.

TABLE 10 Fund Fees

To assess whether the relationship between CO and fund manager fees is plausibly meaningful as an incentive for fund managers to adopt common ownership strategies, we next consider the average fund manager’s compensation.

B. Implications for Fund Manager Compensation

We conduct a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation similar to Lewellen and Lewellen (Reference Lewellen and Lewellen2022). However, where Lewellen and Lewellen (Reference Lewellen and Lewellen2022) consider an exogenous increase in the value of a portfolio position, we consider the payoff to a manager adopting a high-CO strategy. Following Berk and Green (Reference Berk and Green2004), fund managers’ objective is to maximize their compensation, specified as:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{COMPENSATION}_{p,t}={TNA}_{p,t-1}\times \left(1+{r}_{p,t}\right)\times \left(1+ FUND\_{FLOWS}_{p,t}\right)\\ {}\times \left(1- EXPENSE\_{RATIO}_{p,t}\right)\\ {}\times MANAGEMENT\_{FEE}_{p,t},\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{COMPENSATION}_{p,t}={TNA}_{p,t-1}\times \left(1+{r}_{p,t}\right)\times \left(1+ FUND\_{FLOWS}_{p,t}\right)\\ {}\times \left(1- EXPENSE\_{RATIO}_{p,t}\right)\\ {}\times MANAGEMENT\_{FEE}_{p,t},\end{array}} $$

where

![]() $ {TNA}_{p,t-1} $

is the lagged total net assets,

$ {TNA}_{p,t-1} $

is the lagged total net assets,

![]() $ {r}_{p,t} $

is the gross monthly return, and

$ {r}_{p,t} $

is the gross monthly return, and

![]() $ FUND\_{FLOWS}_{p,t} $

is the fund flow represented as a fraction of

$ FUND\_{FLOWS}_{p,t} $

is the fund flow represented as a fraction of

![]() $ {TNA}_{p,t-1} $

.

$ {TNA}_{p,t-1} $

.

![]() $ EXPENSE\_{RATIO}_{p,t} $

and

$ EXPENSE\_{RATIO}_{p,t} $

and

![]() $ MANAGEMENT\_{FEE}_{p,t} $

denote the fund’s expense ratio and management fee, respectively.

$ MANAGEMENT\_{FEE}_{p,t} $

denote the fund’s expense ratio and management fee, respectively.

Using our most conservative estimates, funds with a 1-standard-deviation (0.94%) higher CO have 3.58 BPS higher monthly raw gross returns (column 1 of Panel A of Table 5), 2.55 BPS higher annual expense ratio (column 2 of Table 10), and 1.25 BPS higher annual management fees (column 4 of Table 10). Supplementary Material Table B10 reports that average fund flows are not significantly affected by CO, conditional on fund returns, and there is no existing theory suggesting that fund-level CO should be unconditionally correlated with fund flows. Therefore, we assume no relationship between CO and average fund flows.

For a typical fund in our sample with the median value of all characteristics, fund managers earn around 2.2% (~$41,000) more annual compensation relative to the median $1.92 million if they adopt a strategy with a 1-standard-deviation higher CO. Over 5 years, the fund manager earns around 17.4% (~$333,000) more cumulative compensation, since the increase in annual compensation compounds through the CO–return relationship. This calculation shows that active mutual fund managers seem financially incentivized to pursue common ownership strategies.Footnote 33

V. Fund Manager Voting on Corporate Policies

Our earlier findings reveal that funds with larger common ownership positions achieve higher performance and deliver superior returns to their investors despite charging higher fees. These elevated fees could reflect compensation for costly monitoring efforts directed at corporate policies among competing firms. Therefore, in this section, we study whether funds with higher CO intend to engage with their portfolio companies in ways consistent with the common ownership hypothesis. Specifically, we investigate whether mutual funds with substantial ownership stakes across competing firms strategically vote to maximize their portfolio returns and reduce incentives for competition between product-market rivals.

To this end, we focus on mutual funds’ voting on corporate policy proposals in shareholder meetings. Motivated by the voice model of Edmans et al. (Reference Edmans, Levit and Reilly2019), which demonstrates that common owners have stronger monitoring incentives, we utilize classifications and recommendations from ISS to test: i) whether active mutual funds with higher CO tend to be more active monitors (Iliev and Lowry, Reference Iliev and Lowry2015) and ii) whether they systematically vote to reduce executive pay-performance sensitivity (Antón et al. (Reference Antón, Ederer, Giné and Schmalz2023)) and support the appointment of “common directors” who hold positions across competing firms (Azar and Vives (Reference Azar and Vives2021)).

A. Active Monitoring

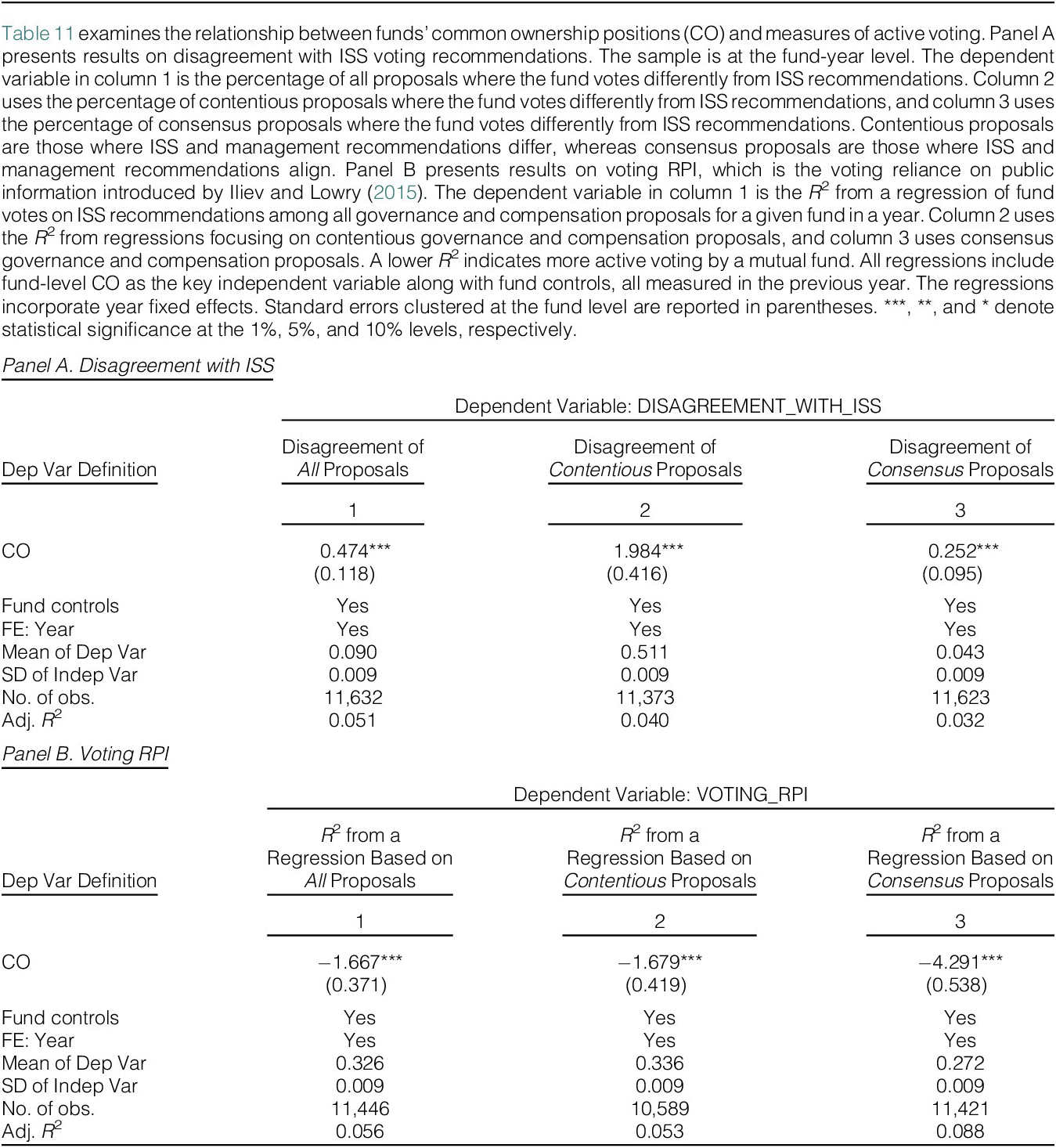

We first examine whether funds with larger common ownership are more active monitors of their portfolio firms. Following Iliev and Lowry (Reference Iliev and Lowry2015), we define active monitoring as the propensity to vote independently of ISS recommendations. Specifically, for each fund in a year, we calculate the percentage of votes where the fund votes differently from ISS recommendations. We relate this proxy for active voting to funds’ CO, along with other fund characteristics measured in the previous year at the fund-year level.

Table 11 reports the results. In column 1, we find that funds with higher CO are associated with greater disagreement with ISS, which is proxied by the percentage of proposals in which the fund votes against ISS recommendations (Iliev and Lowry (Reference Iliev and Lowry2015)). In terms of economic magnitude, a 1-standard-deviation increase in fund CO is associated with a 4.26-percentage-point (0.474

![]() $ \times $

0.09) increase in disagreement with ISS recommendations, representing a substantial increase relative to the unconditional mean of 9.0%.

$ \times $

0.09) increase in disagreement with ISS recommendations, representing a substantial increase relative to the unconditional mean of 9.0%.

TABLE 11 Active Monitoring

In addition, we consider two variants of active voting measures: the percentage of votes where the fund votes differently from ISS recommendations among contentious proposals in column 2 and consensus proposals in column 3. We find that high-CO funds are still positively related to disagreement with ISS. Importantly, as evidenced in column 3, even for proposals where the recommendations of ISS and management align, high-CO funds are still more likely to disagree with them, indicating active voting.Footnote 34

An alternative proxy for active voting proposed by Iliev and Lowry (Reference Iliev and Lowry2015) is the voting RPI, defined as the

![]() $ {R}^2 $

value from a regression of fund votes on ISS recommendations. Following their approach, we focus on governance- and compensation-related proposals that our sample funds vote on and estimate the above regression separately for each fund in a year. A lower

$ {R}^2 $

value from a regression of fund votes on ISS recommendations. Following their approach, we focus on governance- and compensation-related proposals that our sample funds vote on and estimate the above regression separately for each fund in a year. A lower

![]() $ {R}^2 $

indicates more active voting by a mutual fund. Then, we examine whether this active voting indicator is related to the fund’s CO measured in the year prior to the proposals. The results are reported in Panel B of Table 11. In column 1, we find that the voting behaviors of mutual funds with higher CO are less likely to be explained by ISS recommendations. In terms of economic magnitude, a 1-standard-deviation increase in fund CO is associated with a 15-percentage-point (1.667

$ {R}^2 $

indicates more active voting by a mutual fund. Then, we examine whether this active voting indicator is related to the fund’s CO measured in the year prior to the proposals. The results are reported in Panel B of Table 11. In column 1, we find that the voting behaviors of mutual funds with higher CO are less likely to be explained by ISS recommendations. In terms of economic magnitude, a 1-standard-deviation increase in fund CO is associated with a 15-percentage-point (1.667

![]() $ \times $

0.09) decline in the

$ \times $

0.09) decline in the

![]() $ {R}^2 $

from regressions of fund votes on ISS recommendations. These results are robust and even stronger when we estimate the

$ {R}^2 $

from regressions of fund votes on ISS recommendations. These results are robust and even stronger when we estimate the

![]() $ {R}^2 $

using contentious or consensus governance and compensation proposals. Again, these findings suggest that high-CO funds are active voters whose voting activities are less likely to be explained by ISS recommendations.

$ {R}^2 $

using contentious or consensus governance and compensation proposals. Again, these findings suggest that high-CO funds are active voters whose voting activities are less likely to be explained by ISS recommendations.

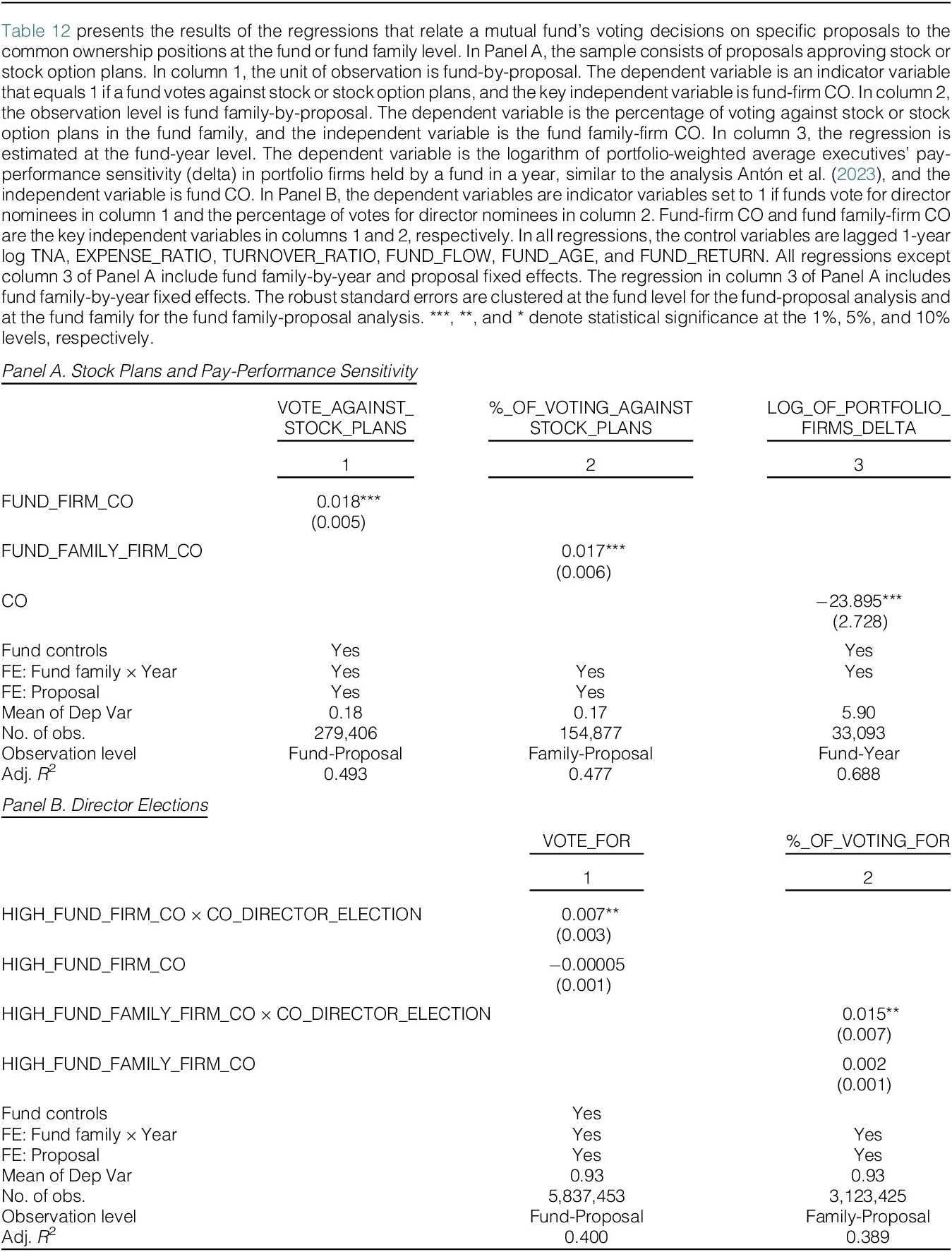

B. Executive Compensation Proposals

We next investigate how mutual fund common owners vote on specific proposals related to executive compensation. Antón et al. (Reference Antón, Ederer, Giné and Schmalz2023) theoretically demonstrate that managerial compensation tends to be less sensitive to own-company performance in the presence of common ownership, as weaker managerial incentives can soften competition within industries. Analogously, we test whether high-CO funds have an incentive to reduce competition among portfolio firms by voting against the proposals related to the approval of executives’ performance-related compensation, such as stock or stock option plans.

Using ISS Voting Analytics data, we estimate fund-by-proposal-level regressions of the form

where

![]() $ p $

indexes a fund,

$ p $

indexes a fund,

![]() $ i $

is a portfolio company,

$ i $

is a portfolio company,

![]() $ k\left(i,t\right) $

is a specific corporate policy proposal for firm

$ k\left(i,t\right) $

is a specific corporate policy proposal for firm

![]() $ i $

in year

$ i $

in year

![]() $ t $

, and

$ t $

, and

![]() $ j(p) $

indicates the fund family of fund

$ j(p) $

indicates the fund family of fund

![]() $ p $

. Observations are structured at the fund-by-proposal level, where a portfolio company could have multiple proposals in the same year. Control variables in

$ p $

. Observations are structured at the fund-by-proposal level, where a portfolio company could have multiple proposals in the same year. Control variables in

![]() $ {X}_{p,t-1} $

are the same as those in equation (9), measured at the year-end preceding the proposal. We incorporate proposal fixed effects

$ {X}_{p,t-1} $

are the same as those in equation (9), measured at the year-end preceding the proposal. We incorporate proposal fixed effects

![]() $ {\gamma}_{k\left(i,t\right)} $

and fund family-by-year fixed effects

$ {\gamma}_{k\left(i,t\right)} $

and fund family-by-year fixed effects

![]() $ {\alpha}_{j(p),t} $

. The former accounts for unobserved heterogeneity at the firm, proposal, and time period levels, whereas the latter controls for time-varying fund family voting patterns (e.g., a family’s general propensity to follow ISS recommendations). With these sets of fixed effects, our identification comes from exploiting variation in votes for a given proposal after controlling for time-varying family unobserved heterogeneity. The dependent variable

$ {\alpha}_{j(p),t} $

. The former accounts for unobserved heterogeneity at the firm, proposal, and time period levels, whereas the latter controls for time-varying fund family voting patterns (e.g., a family’s general propensity to follow ISS recommendations). With these sets of fixed effects, our identification comes from exploiting variation in votes for a given proposal after controlling for time-varying family unobserved heterogeneity. The dependent variable

![]() $ {VOTE}_{p,k\left(i,t\right)} $

varies based on the specific analyses below, and the key independent variable is the previous year-end fund-firm CO measure (i.e., fund

$ {VOTE}_{p,k\left(i,t\right)} $

varies based on the specific analyses below, and the key independent variable is the previous year-end fund-firm CO measure (i.e., fund

![]() $ p $

’s common ownership in firm

$ p $

’s common ownership in firm

![]() $ i $

(

$ i $

(

![]() $ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

in equation (3))). Standard errors are clustered at the fund level, allowing for correlated voting behavior across proposals within a fund (Iliev and Lowry (Reference Iliev and Lowry2015)).

$ {\kappa}_{p,m} $

in equation (3))). Standard errors are clustered at the fund level, allowing for correlated voting behavior across proposals within a fund (Iliev and Lowry (Reference Iliev and Lowry2015)).

Recognizing the substantial influence of fund families on individual fund voting decisions, we also conduct parallel analyses at the fund family-by-proposal level using the following specification: