1. Introduction

In Mandarin Chinese, verbs can be reduplicated to express a delimitative aspectual meaning (e.g. Chao Reference Chao1968: 204–205, Li & Thompson Reference Li and Thompson1981: 232, Li Reference Li1996: 14, Dai Reference Dai1997: 70, Zhu Reference Zhu1998: 382–383, F. Xing Reference Xing2000: 420–421, Q. Chen Reference Chen2001: 48, Tsao Reference Tsao and Chappell2001: 288, Yang Reference Yang2003: 11–12, Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: Section 4.3). This means that the event or state denoted by the verb happens in a short duration and/or a low frequency (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 155), such as illustrated in (1).Footnote 1 Thus, verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese is often translated as doing something ‘a little bit/for a little while’.

The current study tries to determine a suitable formal and unified analysis for the structure of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. It contributes more empirical evidence and offers a novel analysis of this phenomenon in the theoretical framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG; Pollard & Sag Reference Pollard and Sag1994, Sag Reference Sag1997, Müller et al. Reference Müller2024) using Minimal Recursion Semantics (MRS; Copestake et al. Reference Copestake2005) as the semantic representation formalism. This new account of reduplication avoids the problems of previous approaches and explains more forms of deliminative verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese.

This paper is organized as follows: after this introduction, we will present in Section 2 the forms and syntactic distribution as well as the semantics of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. Importantly, we restrict the object of this study to the AA, A-yi-A, A-le-A, A-le-yi-A, ABAB and AB-le-AB forms of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. We will also discuss in this section, with the help of corpus data, the question of whether the reduplication is better analyzed as a morphological or a syntactic process. In Section 3, we will discuss the advantages and drawbacks of previous approaches. Section 4 will present a new HPSG account for verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. Finally, Section 5 will conclude the paper.

The data in this paper was drawn from several sources. In addition to introspection, the Modern Chinese subcorpus of the corpus of the Center for Chinese Linguistics of Peking University (CCL; Zhan, Guo & Chen Reference Zhan2003, Zhan et al. Reference Zhan2019) and the BCC corpus (Xun et al. Reference Xun2016) were also consulted. Further, examples from novels and plays written by native speakers were considered. Corpus data provides natural and contextualized examples, and contains a variation of linguistic properties (Meurers & Müller Reference Meurers, Müller, Lüdeling and Kytö2009: 921). This can help us discover relevant constraints that can otherwise go unnoticed through introspection.

2. The phenomenon

This section introduces the fundamental grammatical behaviors of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. After illustrating its forms, syntactic distribution and semantics, we discuss the questions of whether it is better analyzed as a morphological or a syntactic phenomenon.

2.1. Forms

There is no general agreement on the forms of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. We adopt a broad definition in terms of the forms of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese and list in (2)–(4) all the forms commonly discussed in the literature.

Fan (Reference Fan1964), Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni (Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014) and Xie (Reference Xie2020) compare the AA, ABAB and AABB forms of reduplication and find a number of differences between the AA and ABAB forms compared to the AABB form in terms of their semantics, productivity, syntactic distribution and origin. Specifically, Fan (Reference Fan1964: 277) proposes that AA, ABAB originated from the verb-measure word combination from Middle Chinese, while AABB developed from the reiterative rhetoric from Old Chinese. Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni (Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014: 17–18), Melloni & Basciano (Reference Melloni and Basciano2018: 144) and Xie (Reference Xie2020: 90) identify that AA and ABAB have a diminishing meaning, namely that the event happens for a short duration or to a small extent. By contrast, AABB expresses an increasing meaning, which indicates a repetition or an action in progress (compare (3a) and (3c)). Xie (Reference Xie2020: Section 3.1) also finds a number of differences between AA, ABAB vs. AABB forms, which we will discuss in detail in Section 2.4. These differences seem to suggest that there is a fundamental difference between these two groups of verbal reduplication. The current study will only focus on the AA, A-yi-A, A-le-A, A-le-yi-A, ABAB and AB-le-AB forms of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. AA-kàn, A-kàn-kàn, AAB, A-yi-AB and A-le-AB will also be mentioned occasionally to provide further arguments. In what follows, the term reduplication will be used to refer specifically to the AA, A-yi-A, A-le-A, A-le-yi-A, ABAB and AB-le-AB forms, if not specified otherwise.

2.2. Syntactic distribution

The reduplication has a similar syntactic distribution as an unreduplicated verb (5)–(9).

Sui & Hu (Reference Sui and Hu2016) claim that the syntactic distribution of the deliminative reduplication is subject to the following constraints. First, Sui & Hu (Reference Sui and Hu2016: 319, 332) claim that reduplication cannot appear in a relative clause without a modal verb or a verb with a modal or mood meaning, such as dǎsuàn ‘plan’, ràng ‘let’ and jiào ‘ask’, providing the contrast in (10) as an example.

This claim can be falsified by corpora examples such as (11), where reduplication occurs in relative clauses without modal or mood verbs. We thus consider the contrast in (10) a matter of providing a proper context.

Secondly, Sui & Hu (Reference Sui and Hu2016: 319) show that the reduplication cannot co-occur with a duration or a frequency phrase (12).

As we will show in Section 2.3.4, this can be explained by the redundant semantics of the reduplication and duration and frequency phrases.

Thirdly, Sui & Hu (Reference Sui and Hu2016: 319) note that reduplicated verbs cannot be aspect marked (13).

However, as shown in (5b), le can occur in between the reduplicated verb and expresses the perfective aspectual meaning, that the event denoted by the sentence is realized. Thus, we argue that the reduplication can in fact be aspect marked, but only by le ‘pfv’ but not the other aspect markers. As we will argue in Section 2.3.3, this is also not a syntactic but a semantic constraint.

Sui & Hu (Reference Sui and Hu2016: 319) further claim that the reduplication cannot be embedded under negation. But (14) shows that this is not the case.

Finally, Sui & Hu (Reference Sui and Hu2016: 322) claim that a reduplicated verb cannot combine with a quantized object. However, examples in (15) prove otherwise.

One reviewer suggests that Sui & Hu’s (Reference Sui and Hu2016: 322) claim only holds true for accomplishments, not activities. Since a quantized object only makes accomplishments but not activities telic, the acceptability of (15) is expected (more on the semantics of reduplication will be discussed in Section 2.3). However, we also find examples of reduplicated accomplishments followed by quantized objects in CCL and BCC, as shown in (16).

In sum, we consider that the reduplication has a similar syntactic distribution as an unreduplicated verb, and the incompatibility of the reduplication with duration and frequency phrases as well as aspect markers other than le can be explained semantically, as we will show in the next section.

2.3. Semantics

As shown in Section 1, the reduplication seems to be connected to certain aspectual properties. The current study adopts the two-component aspect model proposed by Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004) based on Smith (Reference Smith1991). The general term ‘aspect’ is considered to encompass the following two components: situation aspect, i.e. ‘aspectual information conveyed by the inherent semantic representation of a verb or an idealized situation’ (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 21); and viewpoint aspect, i.e. ‘the aspectual information reflected by the temporal perspective the speaker takes in presenting a situation’ (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 21). Situation aspect can be further modeled as verb classes at the lexical level and situation types (the interaction of verb classes and other constituents, such as adjuncts) at the sentential level (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 33). The verb classes are determined with verbs in a neutral context (preferably in a perfective viewpoint aspect, with a simple object only when it is obligatory), where everything that might change the aspectual value of a verb is excluded and only the inherent features of the verb itself are considered (see Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 52 for more details). This does not rule out the fact that the same verb may express different aspectual properties in other contexts, but its verb class remains the same, as the aspectual change can be attributable to other components at the sentential level.

In this section, we will first discuss the core meaning of the reduplication as well as the meaning of its different forms (Section 2.3.1). We will then investigate the interaction of the reduplication with verb classes (Section 2.3.2), aspect markers (Section 2.3.3) and other sentential components (Section 2.3.4).

2.3.1. Core meaning

The reduplication has a delimitativeness meaning (e.g. Chao Reference Chao1968: 204–205, Li & Thompson Reference Li and Thompson1981: 232, Li Reference Li1996: 14, Dai Reference Dai1997: 70, Zhu Reference Zhu1998: 382–383, F. Xing Reference Xing2000: 420–421, Q. Chen Reference Chen2001: 48, Tsao Reference Tsao and Chappell2001: 288, Yang Reference Yang2003: 11–12, Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: Section 4.3). To be specific, the reduplication of [

![]() $ + $

durative] verbs reduces the duration of the events, and the reduplication of [

$ + $

durative] verbs reduces the duration of the events, and the reduplication of [

![]() $ - $

durative] verbs reduces the iteration frequency of the events (Li Reference Li1996: 14, Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 149–150). Besides delimitativeness, Chao (Reference Chao1968: 204), Fan (Reference Fan1964: 276), Smith (Reference Smith1991: 356, Reference Smith1994: 199–120), Li (Reference Li1996: 14), and Tsao (Reference Tsao and Chappell2001: 290–291) suggest that the reduplication signifies tentativeness, which can be used ‘to refer modestly to one’s own activities, or for mild imperatives’ (Smith Reference Smith1991: 356), or ‘trying to’ do something (Li & Thompson Reference Li and Thompson1981: 234). Frequentativeness or habitualness, that the event denoted by the verb happens frequently or habitually, is mentioned by Fan (Reference Fan1964: 276), Li (Reference Li1996: 15) and Qian (Reference Qian2000: 1) as the meaning of reduplication as well. Fan (Reference Fan1964: 276) further proposes a meaning of slightness or casualness for reduplication, which implies that the event is unimportant or conveys a casual attitude of the speaker. Zhu (Reference Zhu1998: Section 3.1.3) suggests that the main function of reduplication is to increase the agency of the action or the change denoted by the verb.

$ - $

durative] verbs reduces the iteration frequency of the events (Li Reference Li1996: 14, Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 149–150). Besides delimitativeness, Chao (Reference Chao1968: 204), Fan (Reference Fan1964: 276), Smith (Reference Smith1991: 356, Reference Smith1994: 199–120), Li (Reference Li1996: 14), and Tsao (Reference Tsao and Chappell2001: 290–291) suggest that the reduplication signifies tentativeness, which can be used ‘to refer modestly to one’s own activities, or for mild imperatives’ (Smith Reference Smith1991: 356), or ‘trying to’ do something (Li & Thompson Reference Li and Thompson1981: 234). Frequentativeness or habitualness, that the event denoted by the verb happens frequently or habitually, is mentioned by Fan (Reference Fan1964: 276), Li (Reference Li1996: 15) and Qian (Reference Qian2000: 1) as the meaning of reduplication as well. Fan (Reference Fan1964: 276) further proposes a meaning of slightness or casualness for reduplication, which implies that the event is unimportant or conveys a casual attitude of the speaker. Zhu (Reference Zhu1998: Section 3.1.3) suggests that the main function of reduplication is to increase the agency of the action or the change denoted by the verb.

In general, all of the above-cited research agrees that the reduplication expresses a short duration and/or a low frequency, which fits the definition of delimitativeness. Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 152–154) and Yang (Reference Yang2003) argue that the core meaning of reduplication is delimitativeness, while all other meanings are merely pragmatic extensions in specific contexts. Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 152–154) point out that tentativeness and casualness are constrained by a number of contextual elements such as the reduplicated verb must be volitional and the subject of the sentence must be animate. But these constraints are only necessary but not sufficient conditions for a tentative or casual meaning of reduplication. Among all instances of verbal reduplication they found in a corpus, all of them have a delimitative reading, while only some of them convey tentativeness or casualness. Yang (Reference Yang2003) compares the sentence pairs with reduplicated verbs and their unreduplicated counterparts, and shows that the reduplication itself does not add a tentative, frequentative, casualness or increased agency meaning to the sentence. Rather, these additional meanings arise from the sentences or the contexts as a whole. She concludes that these additional meanings are results of meaning extensions of delimitativeness in specific contexts. We follow Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004) and Yang (Reference Yang2003) and treat delimitativeness as the central meaning of reduplication, and the other meanings as pragmatic extensions.

The semantics of the reduplication has the properties of transitoriness, holisticity and dynamicity (Dai Reference Dai1997: 70–79, Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 155–159). It presents the situation as a transitory and non-decomposable whole. A situation expressed by a sentence with the reduplication involves changes not only in the initiation and termination of an event, but also in the transitory process itself. Compared to (17a), which could mean that the protagonist kept staring at the footprint, (17b) indicates that the protagonist took a brief look or several brief looks at the footprint and looked away in the end, which is a process full of changes.

The semantics of A-le-A can be deduced compositionally from its structure. It is a hierarchical combination of the perfective aspect and delimitativeness, ‘conveying a transitory event which has been actualized’ (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 151).

As for A-yi-A, Fan (Reference Fan1964: 273) compares examples found in novels and plays and concludes that A-yi-A has exactly the same meaning as its AA counterpart. She thus assumed that AA is merely a form of A-yi-A, where the yi is omitted phonologically. F. Xing (Reference Xing2000: Section 5) considers that the major difference between AA and A-yi-A lies in the speaker’s attitude. The former conveys a casual attitude whereas the latter sounds more serious. However, he stresses that there is no difference in the delimitative semantics of both forms, and that the variance in meaning is a pragmatic one. The difference is also not absolute and often only shows a tendency. Xu (Reference Xu2002) finds out that compared to A-yi-A, one tends to use AA in contexts with strong emotional attitudes, urgent, casual, timid or uncertain contexts. But he also states that these differences are pragmatic rather than semantic, as he argues that AA and A-yi-A can be used interchangeably in most cases, and the differences in meaning only arise from specific contexts as a whole. Yang (Reference Yang2003: 15) suggests that AA and A-yi-A have the same core meaning, while A-yi-A implies a slightly more serious attitude than AA due to its length. We assume A-yi-A to be a form of reduplication and that it has the same core semantics as AA.

AA-kàn and A-kàn-kàn are described to express a ‘try … and find out’ meaning (Cheng Reference Cheng2012: 63). Tsao (Reference Tsao and Chappell2001: 290) also observes that the tentative meaning is particularly prominent when the reduplication is followed by kàn ‘look’. We still consider the tentativeness implied by these two forms to be a pragmatic extension of delimitativeness. The tentative meaning is made prominent by the verb kàn ‘look’, and the whole structure can be understood as ‘do A a little bit and see’.

2.3.2. Interaction with verb classes

Previous research often claims that the reduplication can only be used for certain verb classes, while it is infelicitous for other ones. Li & Thompson (Reference Li and Thompson1981: 234–235) and Hong (Reference Hong1999: 277–278) suggest that reduplication is only possible for volitional activity verbs. Dai (Reference Dai1997: 70–71) and Tsao (Reference Tsao and Chappell2001: 290) both consider that reduplication can only be used in dynamic situations. The former further claims that achievement verbs cannot be reduplicated. Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 155), Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni (Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014: 20) and Basciano & Melloni (Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 145) propose that only [

![]() $ + $

dynamic] and [

$ + $

dynamic] and [

![]() $ - $

result] verbs can be reduplicated. This means that the reduplication can only interact with dynamic situations which encode no results and is consequently only compatible with activities and semelfactives, but not with states and achievements.

$ - $

result] verbs can be reduplicated. This means that the reduplication can only interact with dynamic situations which encode no results and is consequently only compatible with activities and semelfactives, but not with states and achievements.

Q. Chen (Reference Chen2001: 53) and Yang (Reference Yang2003: 10–11) acknowledge that the reduplication of non-volitional verbs is more restricted than that of volitional ones. But Zhu (Reference Zhu1998: 381–382) lists a number of non-volitional predicates that can be reduplicated. We found the examples shown in (18) in CCL where non-volitional verbs wěiqū ‘feel wronged’, rèn-xìng ‘be willful’ and diào ‘drop’ are reduplicated.Footnote 5

It is true that the reduplication of stative and achievement verbs is not as easily acceptable as that of activities and semelfactives. Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 155) classify bìng ‘be sick’ as a stative verb. Indeed, compared to the questionable reduplication of bìng ‘be sick’ in (19a), the reduplication of the activity verb kàn ‘watch’ in (19b) and that of the semelfactive verb késòu ‘cough’ in (19c) are readily acceptable.

However, examples such as (20) can be found where bìng ‘be sick’ is reduplicated.

As a reviewer points out, Tham (Reference Tham2013: Section 3.3) considers bìng ‘be sick’ to be a basic change of state (COS) verb, i.e. ‘become sick’. In contrast, she uses xǐhuān ‘like’ and xiāngxìn ‘believe’ as examples of stative verbs. Peck, Lin & Sun (Reference Peck2013: 680) also list xǐhuān ‘like’ and xiāngxìn ‘believe’ as stative verbs. For these two verbs, examples such as (21) and (22) can be found.

On the other hand, as the reviewer and indeed Tham (Reference Tham2013: 669–670) herself note, verbs expressing psychological states such as these can have a COS interpretation (but not necessarily), let us look at other examples of stative verbs listed by Peck, Lin & Sun (Reference Peck2013: 680) which do not express psychological states, and examples in Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: Section 3.3.3) of individual-level states (ILSs) which only have stative interpretation, as opposed to stage-level states (SLSs) which can have both stative and dynamic interpretations.Footnote 6 The following examples contain the reduplication of xiàng ‘look like’ and zài-chǎng ‘be present on the scene’.

One might argue that even in the examples above, dynamic rather than stative meaning is conveyed. We argue that the dynamic interpretation does not come from the verb but from reduplication. The use of reduplication affects the situation aspect at the sentential level. And as we describe in Section 2.3.1, the semantics of reduplication has the property dynamicity. Verbs such as xiàng ‘look like’ and zài-chǎng ‘be present on the scene’ are stative in a neutral context and thus, we consider the intrinsic feature of these verbs to be stative and they should be classified as stative verbs. The dynamic interpretation only arises when they are used in specific contexts, in this case, when they are reduplicated.

Similar to stative verbs, the reduplication of achievement verbs is also not readily acceptable, as shown in (25) with reduplication of yíng ‘win’.

However, examples such as those in (26a–c) can be found. Here, achievement verbs like wàng ‘forget’ and shēng ‘give birth to’ are reduplicated.

The examples presented in this section show that although the reduplication does have a tendency to interact with volitional verbs and with activities and semelfactives due to its dynamic meaning, this is by no means a rigid constraint, and non-volitional verbs, states and achievements can be reduplicated in appropriate contexts as well, contrary to common beliefs in the literature. Thus, a theoretical account of reduplication should not restrict its use to only certain verb classes.

2.3.3. Interaction with aspect markers

As mentioned in Section 2.2, the reduplication can only be marked by the perfective aspect marker le but not other aspect markers.Footnote 9 We believe this incompatibility to be for semantic reasons.

Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: Chapter 4) consider le, guo and reduplication to indicate perfective aspects, as they all view the situation as an inseparable whole. The perfective aspect marker le is compatible with reduplication while the experiential aspect marker guo is not. Xiao & McEnery (Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 128–131) state that le has the semantic feature of dynamicity, since it ‘can focus on both heterogeneous internal structures and changing points’ (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 129). It can be combined with a situation with a dynamic internal structure, such as crying in (27a). It can also co-occur with a situation with a change at a certain time point, such as getting to know in (27b). As shown in Section 2.3.1, reduplication can also express dynamicity of both a time point and a time period, just like le illustrated here. Therefore, le is compatible with reduplication.

In comparison, the experiential aspect marker guo cannot co-occur with a reduplicated verb, because its dynamicity attributes to an ‘experiential change’ (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 148), namely that a situation has been experienced historically and that ‘the final state of the situation no longer obtains’ at the reference time (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 144). Compare (28a) and (28b), guo in (28a) suggests a change out of the state of being a soldier, whereas le in (28b) conveys a change into the state of being a soldier (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 149).

It is clear that guo only indicates a change at the termination of a situation and cannot express the dynamicity within a situation. Hence, it is incompatible with the semantics of the reduplication.

Due to the holistic semantics of the reduplication, it is incompatible with imperfective aspect markers: the durative aspect marker zhe and the progressive aspect marker zài, as both only focus on a part of the situation and do not view the situation as a whole (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: Chapter 5).

From the illustration above, it seems that due to its semantics, reduplication can only be marked by le but not the other aspect markers.

2.3.4. Interaction with other sentential components

The reduplication is incompatible with an expression that quantifies the duration or the extent of the event expressed in the sentence (29) (Li Reference Li1998: 83–84, L. Chen Reference Chen2005: 114–115). This is because the reduplication already contains a quantity meaning (Li Reference Li1998: 84, L. Chen Reference Chen2005: 114–115), namely a short duration or a small extent, which cannot be measured on a concrete scale (Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004: 155, Sui & Hu Reference Sui and Hu2016: 333). This results from the properties of reduplication rather than the verb itself, as the verb itself can be combined with such an expression (29a).

2.4. Word vs. phrase

The literature on reduplication makes different assumptions on whether it is a morphological or syntactic phenomenon. Chao (Reference Chao1968: Chapter 4), Li & Thompson (Reference Li and Thompson1981: Chapter 3), Dai (Reference Dai1992: Section 4.1) and Liao (Reference Liao and Li2014: 4–5) list reduplication under morphological processes. By contrast, Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni (Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014: 23), Xiong (Reference Xiong2016), Basciano & Melloni (Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 146), Yang & Wei (Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 229–231), Melloni & Basciano (Reference Melloni and Basciano2018: 330) and Xie (Reference Xie2020) claim it to be syntactic. This section reviews the arguments in Xie (Reference Xie2020) and applies tests from Dai (Reference Dai1992: Section 7, 1998: Section 2.3–2.4) to distinguish words from phrases in Mandarin Chinese. The results are compatible with a lexical analysis.

Xie (Reference Xie2020) compares the AA and the ABAB forms of reduplication with the AABB form and claims that AA and ABAB are syntactic processes while AABB is morphological. She points out that AA and ABAB behave differently from AABB in their productivity, possibility of le insertion, categorial stability, transitivity, and input/output constraints. While AA and ABAB are highly productive, AABB shows low productivity. Le can be inserted freely into AA (30) and ABAB (31) but not into AABB (32).

The output of AA and ABAB does not change the grammatical category of the input (verb), but the output of AABB could have other categories such as adverb (33) or adjective (34).

AA and ABAB do not change the valency of the input verb, but AABB makes a transitive verb intransitive (35).

The two groups also have different input and output constraints. Xie (Reference Xie2020) claims that only dynamic and volitional verbs can undergo AA or ABAB reduplication (but see Section 2.3.2). In comparison, AABB requires its input to be a complex verb whose constituents are either synonymous, antonymous or logically coordinated (36). Moreover, as can be seen in the translation in (36), the output of AABB has an increasing meaning, i.e. an event happens repeatedly or continuously, as opposed to the delimitative meaning of AA and ABAB.

However, a morphological process can be productive, and it does not necessarily change the part of speech label or valency of the input. For instance, the -able derivation in English is a productive morphological process. The adjective inflection in languages like German does change neither the part of speech nor the valency of the adjectival stem.Footnote 10 Further, if le is considered to be a morphological element (e.g. Huang, Li & Li Reference Huang2009: 101–102, Müller & Lipenkova Reference Müller, Lipenkova, Lai and Chui2013: 246), the insertion of le does not have to be viewed as a syntactic process either. It seems that Xie (Reference Xie2020) only shows that AA and ABAB are different processes than AABB, but not necessarily that the former is syntactic while the latter morphological.

A reviewer claims that le insertion can be seen as a violation of lexical integrity, because it is never found in between the two constituents of a compound word, but must be placed after the whole unit. For instance, Her (Reference Her2006: 1282) claims that the V-gěi sequence cannot be separated and uses this as evidence for analyzing it as a single lexical item (jì-gěi-le tā ‘send-give-pfv he, sent him’ vs. ? jì-le-gěi tā ‘send-pfv-give he’). In non-separable VO compounds, le insertion also does not seem to be possible (guān-xīn-le ‘close-heart-pfv, cared for’ vs. ? guān-le-xīn ‘close-pfv-heart’). The AABB form of reduplication also only accepts le to its right but not in between (37).

In respond to this, we found counter-examples that show le insertion in between V-gěi (38) as well as guān-xīn ‘close-heart, care for’ (39) is possible.

In any case, since reduplication is not compounding (Sui Reference Sui, Finkbeiner and Freywald2018: 149–150, Gao, Lyu & Lin Reference Gao2021 provide psycholinguistic evidence), and the patterns discussed here constitute a different process than the AABB pattern (see the discussions above, also Deng Reference Deng2013: Section 4.3, Sui & Hu Reference Sui and Hu2016: Section 2, Sui Reference Sui, Finkbeiner and Freywald2018 and Wang Reference Wang2023), it is not surprising that le occurs at a different position.

It is, therefore, necessary to resort to other tests that are intended to distinguish words from phrases in Mandarin Chinese. For this purpose, Dai (Reference Dai1992: 32–33, Reference Dai and Packard1998: 117–120) proposes the modification and the expansion tests.

First, the modification test suggests that subparts of a word cannot be modified at a phrasal level. This is possible for a VP (40), as the NP inside of the VP can be modified by e.g. an AP.

In contrast, the individual verbs in reduplication cannot be modified by an e.g. AdvP. (41) is ungrammatical whether the AdvP is interpreted to modify the first or the second verb. This shows that it has nothing to do with the relative position of the verb and the AdvP.Footnote 11

Second, the expansion test suggests that a phrasal dependent (either a modifier or an argument) cannot be inserted into a word. Expansion is possible for a verbal classifier phrase (42), as the object can occur after or in between.

For reduplication, expansion is not possible (43), as the object cannot be inserted between the two verbs.

The above two tests indicate a lexical analysis for reduplication.

Cross-linguistically, verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese patterns more with morphological reduplication (below as reduplication) in other languages than syntactic reduplication (below as repetition; Gil Reference Gil and Hurch2005: 31, Forza Reference Forza2016: 1–2).Footnote 12 Gil (Reference Gil and Hurch2005: 35–36) considers non-iconicity and having only two (but not more) copies as sufficient but not necessary conditions for reduplication. He further proposes building one intonational group as sufficient and necessary condition for reduplication (p. 36). All three conditions are true for verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese (see Sui Reference Sui, Finkbeiner and Freywald2018: 154 on the intonation of verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese). Forza (Reference Forza2016: 9) argues that the substantial difference between reduplication and repetition lies in the fact that only the former affects grammatical features such as aspect. This is also the case for verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese.

In sum, we maintain that verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese is better analyzed as a morphological phenomenon.

3. Previous analyses

Previous analyses of the reduplication in Mandarin Chinese and in other languages can be classified into three groups: the reduplication as a verbal classifier phrase (Section 3.1), as an aspect modifier (Section 3.2), and as a special reduplication construction (Section 3.3).Footnote 13 This section will review these analyses and will discuss their advantages and shortcomings.

3.1. The reduplication as a verbal classifier phrase

Fan (Reference Fan1964), Chao (Reference Chao1968: 205) and Xiong (Reference Xiong2016) analyze the reduplication in Mandarin Chinese as a verbal classifier phraseFootnote 14. A verbal classifier is a measure for verbs of action that ‘expresses the number of times an action takes place’ (Chao Reference Chao1968: 615), such as the cì in (44).

In this analysis, the first element in the reduplication is the actual verb, the second element is a verbal classifier borrowed from a verb, and yi ‘one’ is an optional pseudo-numeral that only has an abstract ‘a little bit’ meaning. The analysis is syntactic.

The parallel between the reduplication and a verbal classifier phrase is obvious. Both the reduplication and the verbal classifier phrase serve to quantify the duration or the extent of a situation. A reduplication structure can often be paraphrased into a verbal classifier phrase such as yí xià ‘once, a while’, yí huì ‘a while’, as illustrated in (45).

However, there are several arguments suggesting that the reduplication cannot be analyzed the same way as a verbal classifier phrase. First, the verb and the verbal classifier can be separated (46), while the reduplication cannot (47) (Paris Reference Paris and Cao2013: 269).Footnote 15, Footnote 16

Second, unlike verbal classifiers (48), the yi ‘one’ in A-yi-A cannot be replaced by other numerals (49) (Yang & Wei Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 299–230).

Third, idioms (50a) lose their idiomatic meaning when used with verbal classifiers (50b), but maintain their idiomatic meaning with reduplications (50c) (Yang & Wei Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 230–231).Footnote 17

Based on these observations, it seems inappropriate to view reduplication as involving a kind of verbal classifier phrase.

3.2. The reduplicant as an aspect modifier

A number of studies consider the reduplication to be an element that modifies the aspectual properties of the base verb (Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014, Basciano & Melloni Reference Basciano and Melloni2017, Yang & Wei Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017) due to the delimitative aspectual meaning of reduplication.

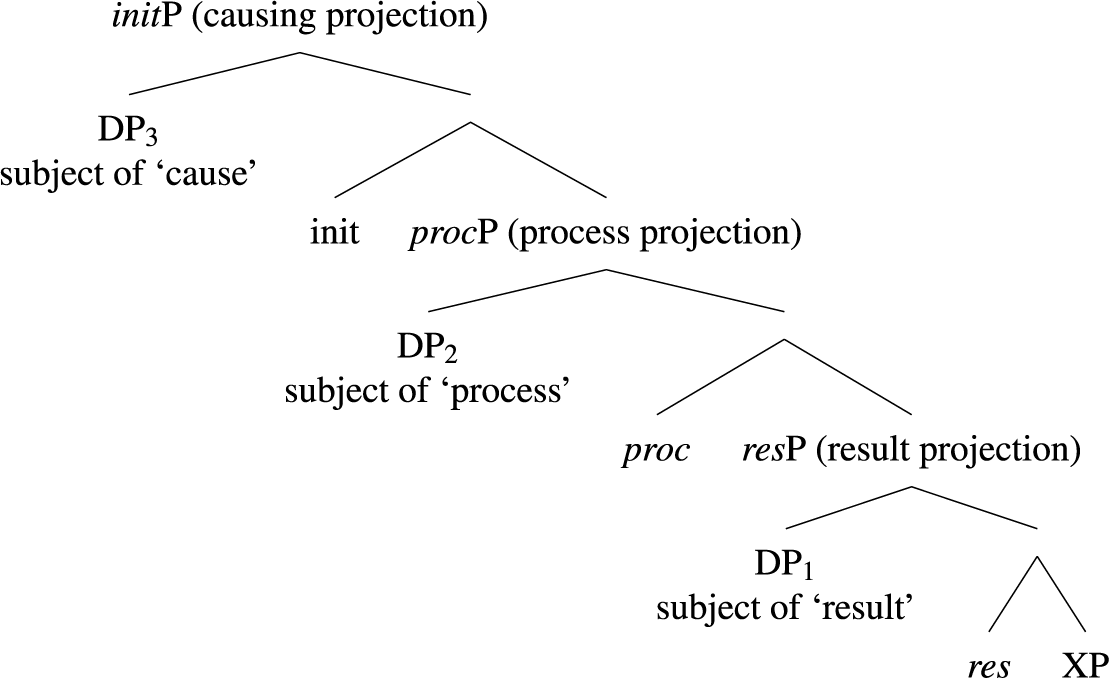

Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni (Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014) and Basciano & Melloni (Reference Basciano and Melloni2017) analyze the reduplication within the framework of First Phase Syntax (Ramchand Reference Ramchand2008). Ramchand (Reference Ramchand2008) proposes that an event is comprised of the following phrases: the causative subevent (initP), the process subevent (procP) and the result subevent (resP), which are ordered hierarchically, as illustrated in Figure 1.Footnote 18 Dynamic and volitional verbs have the features [init proc] and are therefore located under init and proc (Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014: 24, Basciano & Melloni Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 147). Achievement verbs possess the feature [res] and reside under res (Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014: 24, Basciano & Melloni Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 147). Stative verbs do not contain a procP (Basciano & Melloni Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 152).

Figure 1. Event structure according to Ramchand (Reference Ramchand2008: 193)

Arcodia, Basciano & Melloni (Reference Arcodia and Augendre2014) and Basciano & Melloni (Reference Basciano and Melloni2017) assume that the first element in the reduplication is the actual verb, which resides under init and proc, and that the second element is the copy of the verb, which resides in the complement position of proc and serves as an event delimiter. Since the second element occupies the same syntactic position as resP, it should have complementary distribution with resP and should thus be incompatible with achievement verbs because of their [res] feature. Furthermore, if procP does not exist in the event, as in the case of states, there should be no place for the reduplication either.

This analysis correctly predicts that the reduplication of achievement verbs and stative verbs is not as easily acceptable as that of dynamic and volitional verbs (marked by [init, proc] features).

However, as shown in Section 2.3.2, the reduplication of states and achievements is unusual but not impossible. This suggests that the reduced acceptability of reduplicated achievement and stative verbs is semantic rather than structural. Their use is possible in specific contexts and should not be ruled out syntactically. Consequently, this proposal does not seem to offer an appropriate account for reduplication.

Yang & Wei (Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 229) endorse the analysis of reduplication as an aspect marker following the structure of Mandarin Chinese aspects proposed by Tsai (Reference Tsai2008). Yang & Wei (Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017) did not spell out the exact analysis. We worked out the analysis for reduplication based on Tsai (Reference Tsai2008), and show in Appendix A that Tsai’s (Reference Tsai2008) system has a syntax-semantics mismatch problem.

3.3. Reduplication construction

Fan, Song & Bond (Reference Fan and Müller2015) provide a unified HPSG analysis for the reduplication of both verbs and adjectives in Mandarin Chinese. They consider reduplication to be a morphological process and model it via lexical rules. They provide the lexical rule (51) for reduplication in general, and further propose redup-a-lr and redup-v-lr as subtypes of redup-type, as illustrated in (52) and (53) respectively.Footnote 19 For them, the reduplication functions as an intensifier predicate, as represented in the predicate (pred) in the constructional-content (c-cont). The intensifier_x_rel has two subtypes: redup_up_x_rel for the amplifying meaning of adjectival reduplication and redup_down_x_rel for the delimitative meaning of verbal reduplication. The orthography is handled separately. The AABB form for adjectives and the ABAB form for verbs, as well as the AAB form for V-O compounds, are handled as irregular derivation forms.

This approach provides a unified account for adjectival and verbal reduplication. Their commonalities are captured by inheritance hierarchies of the intensifier predicates and the lexical rules. In the case of verbal reduplication, A-yi-A is analyzed as an alternative orthographical form of AA. This correctly captured the intuition that AA and A-yi-A express the same meaning and only differ from each other phonologically/orthographically (see Section 2.3.1).

Nevertheless, this analysis has some shortcomings. To begin with, since the combination with aspect markers is completely forbidden, it is impossible for this approach to account for A-le-A. Moreover, as verbal reduplication is considered to express a delimitative aspectual meaning, it seems unconvincing to assume that there is no aspect information in its semantics. We consider a semantic explanation as described in Section 2.3.3 to be more reasonable for ruling out aspect markers other than le. Furthermore, this account can only deal with monosyllabic reduplication and handles ABAB and AAB as irregular forms, for the reason that ABAB and AAB reduplication of AB verbs ‘are not very productive in Chinese’ (Fan, Song & Bond Reference Fan and Müller2015: 102). This is not true. H. Xing (Reference Xing2000: 33), Basciano & Melloni (Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 161), Melloni & Basciano (Reference Melloni and Basciano2018: 329) and Xie (Reference Xie2020: Section 2) all consider both AA and ABAB to be productive, and H. Xing (Reference Xing2000: 36) concludes that AAB is productive as well. Thus, these forms should not be handled as irregular forms, but should be derivable by lexical rules.

The shortcomings of previous analyses lead us to propose a new analysis on verbal reduplication within HPSG, which formalizes the phonology of the reduplication, resolves the problem of yi and preserves the generalization on aspect marking, as we will elaborate in Section 4.

4. A new HPSG analysis

In this section, we suggest a new lexical-rule-based analysis of aspect marking and reduplication using Minimal Recursion Semantics (MRS; Copestake et al. Reference Copestake2005). MRS is an instance of underspecified semantics as is currently used in theoretical and computational work in HPSG (Koenig & Richter Reference Koenig, Richter and Müller2024: Section 6, Bender, Flickinger & Oepen Reference Bender and Carroll2002: Section 3, Müller Reference Müller2015: Section 4.4, Müller Reference Müller2025: Chapter 5). The advantage of such types of semantics is that scope relations can be left underspecified. This way, it is avoided that large numbers of analyses are assigned to single sentences. Instead sentences are paired with underspecified semantic representations from which various readings can be derived. MRS uses lists of elementary predications that are connected via pointers. Scope constraints are represented by statements of domination. This allows for elegant ways to underspecify scope. The details cannot be discussed here. The interested reader is referred to Copestake et al. (Reference Copestake2005), Koenig & Richter (Reference Koenig, Richter and Müller2024: Section 6) or for the use of MRS in a grammar of German to Müller (Reference Müller2025: Chapter 5). In what follows, we will present the elementary predications with the features assumed in MRS, but leave out handle constraints to keep things simple.

Like Fan, Song & Bond (Reference Fan and Müller2015), we assume lexical rules for reduplication. Our lexical rules are organized in an inheritance network. verbal-reduplication-lr is the most general type for reduplication lexical rules in this network and the implicational constraint in (54) shows the constraints on all structures of type verbal-reduplication-lr. Such structures take a verb as lexical-daughter (lex-dtr). The output reduplicates the phonology (phon) of the input verb with the possibility to have further phonological material in between.

![]() $ \square $

indicates an underspecified list which could be empty or not.Footnote 20 A delimitative relation is appended to the relations (rels) value of the input verb, and it takes the event index of the input verb (

$ \square $

indicates an underspecified list which could be empty or not.Footnote 20 A delimitative relation is appended to the relations (rels) value of the input verb, and it takes the event index of the input verb (

![]() $ \boxed{3} $

) as argument (arg0, …, arg3 are feature names for arguments. The values are indices or events similar to variables in normal predicate logic.). The list of relations contains so-called elementary predications. There is no complicated embedding of relations. Instead each elementary predication comes with a label (lbl). The label can be used as an argument of another relation or in scope constraints, which are not provided here to keep things simple. The feature ltop points to the local top. This is the elementary predication that is considered the top-most one in the rels list. Other elementary predications may share the label or have arguments with labels of other elementary predications. We will discuss an example below when we discuss the perfective lexical rule. The label of the output (

$ \boxed{3} $

) as argument (arg0, …, arg3 are feature names for arguments. The values are indices or events similar to variables in normal predicate logic.). The list of relations contains so-called elementary predications. There is no complicated embedding of relations. Instead each elementary predication comes with a label (lbl). The label can be used as an argument of another relation or in scope constraints, which are not provided here to keep things simple. The feature ltop points to the local top. This is the elementary predication that is considered the top-most one in the rels list. Other elementary predications may share the label or have arguments with labels of other elementary predications. We will discuss an example below when we discuss the perfective lexical rule. The label of the output (

![]() $ \boxed{2} $

) is identified with the label of the input and with the label of the delimitative relation, hence delimitative-rel is treated as an intersective modifier. Further relations can be added at the beginning of the rels list to allow for the additional perfective meaning in A-le-A and A-le-yi-A. The combination with the perfective will be elaborated on in the following paragraphs.

$ \boxed{2} $

) is identified with the label of the input and with the label of the delimitative relation, hence delimitative-rel is treated as an intersective modifier. Further relations can be added at the beginning of the rels list to allow for the additional perfective meaning in A-le-A and A-le-yi-A. The combination with the perfective will be elaborated on in the following paragraphs.

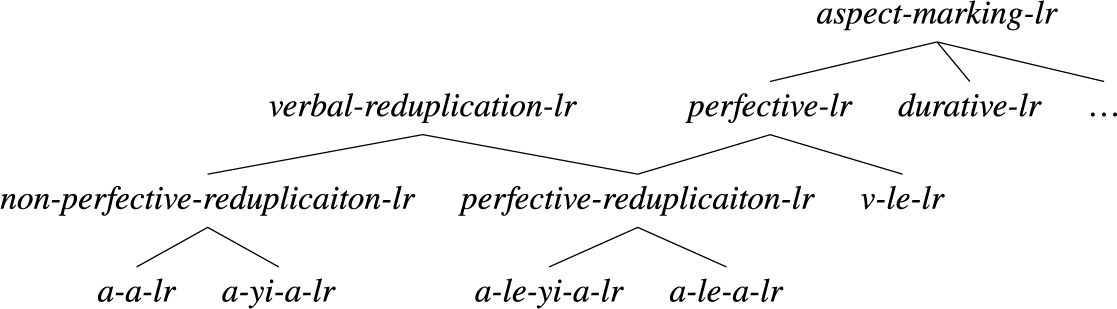

To account for the variations in the phonology of the reduplication as well as the combination with the phonology and semantics of the perfective aspect marker le, the type hierarchy of lexical rules in Figure 2 is put forward. Apart from the type perfective-reduplication-lr, which adds the inherited perfective relation, there is a subtype non-perfective-reduplication-lr, which does not add further relations. Hence, what is

![]() $ \square $

in the rels list in (54) is the empty list in (55):

$ \square $

in the rels list in (54) is the empty list in (55):

Figure 2. Type hierarchy for lexical rules of verbal reduplication and le

The rels list of the output of the lexical rule is the rels list of the daughter (

![]() $ \boxed{1} $

) plus a list with one element. Since this element is specified in the supertype, it is not specified in (55) again.

$ \boxed{1} $

) plus a list with one element. Since this element is specified in the supertype, it is not specified in (55) again.

non-perfective-verbal-reduplication-lr has aa-lr and a-yi-a-lr as direct subtypes. (57) and (58) show aa-lr and a-yi-a-lr, respectively. As subtypes of verbal-reduplication-lr illustrated in (54), both inherit the constraints on the lex-dtr and on the semantics of the output, and because of (55), no extra material is appended to the rels value of the input verb and the list containing the delimitative-rel. In addition to the inherited constraints, aa-lr and a-yi-a-lr specify the phonology of the output differently. aa-lr determines that the

![]() $ \square $

between the two phonological copies in (54) is the empty list, whereas a-yi-a-lr specifies this list of phonological material as

$ \square $

between the two phonological copies in (54) is the empty list, whereas a-yi-a-lr specifies this list of phonological material as

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em yi\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

:

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em yi\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

:

The lexical rules with all inherited constraints are given in (57) and (58):

v-le-lr is a direct subtype of the perfective-lr. perfective-reduplication-lr inherits from both verbal-reduplication-lr and perfective-lr and has two subtypes, a-le-yi-a-lr and a-le-a-lr itself. verbal-reduplication-lr is already presented in (54). We now turn to the constraints on perfective-lr and its subtypes.

Müller & Lipenkova (Reference Müller, Lipenkova, Lai and Chui2013: 246) propose the perfective lexical rule given in (59), adapted to the formalization adopted in the current paper. It takes a verb as lex-dtr and appends

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

to its phonology. Further, it accounts for the change in semantics by appending the rels value of the input verb to a perfective-rel.

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

to its phonology. Further, it accounts for the change in semantics by appending the rels value of the input verb to a perfective-rel.

The event variables (

![]() $ \boxed{3} $

) of the input and the output verb are shared. The ltop of the output of the lexical rule (

$ \boxed{3} $

) of the input and the output verb are shared. The ltop of the output of the lexical rule (

![]() $ \boxed{2} $

) is the label of the perfective relation, and this relation scopes over the embedded verb. The handle of the embedded verb (

$ \boxed{2} $

) is the label of the perfective relation, and this relation scopes over the embedded verb. The handle of the embedded verb (

![]() $ \boxed{4} $

) is the argument of the perfective-rel.

$ \boxed{4} $

) is the argument of the perfective-rel.

The lexical rule suggested in (59) only explains simple perfective aspect marking with le, where le immediately follows the verb. But it cannot account for the perfective aspect marking of a reduplicated verb, as le does not occur after the reduplication, nor can le be reduplicated together with the verb. It can only appear between the verb and the reduplicant. In order to accommodate le marking for both simple and reduplicated verbs, a general perfective lexical rule as in (60) and a subtype v-le-lr as in (61) are posited here. Besides adding a perfective-rel in the rels list of the output as in (59), the perfective-lr in (60) allows an underspecified list to be appended at the end of the rels list. The phon value of the output makes it possible for further phonological material to occur both before and after

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

.

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

.

v-le-lr with all inherited constraints as given in (61) inherits from perfective-lr and specifies that the first element in the output phon list is identified with the phon value of the input verb and that nothing else comes after

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

. Furthermore, no other list can be appended at the end of the rels list of the output anymore. This corresponds to the proposal of Müller & Lipenkova (Reference Müller, Lipenkova, Lai and Chui2013: 246) shown in (59), which accounts for the simple perfective marking of verbs.

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

. Furthermore, no other list can be appended at the end of the rels list of the output anymore. This corresponds to the proposal of Müller & Lipenkova (Reference Müller, Lipenkova, Lai and Chui2013: 246) shown in (59), which accounts for the simple perfective marking of verbs.

perfective-reduplication-lr inherits from both verbal-reduplication-lr and perfective-lr. The phon value of the output reduplicates the phonology of the input verb and states that there is

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

in between, as well as potentially further phonological material. The rels list of the output appends the delimitative-rel to the perfective-rel and the rels value of the input verb. The arguments of both perfective-rel and delimitative-rel share the event index of the input verb (

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

in between, as well as potentially further phonological material. The rels list of the output appends the delimitative-rel to the perfective-rel and the rels value of the input verb. The arguments of both perfective-rel and delimitative-rel share the event index of the input verb (

![]() $ \boxed{3} $

) to ensure that they apply to the same event denoted by the input verb. The label of the delimitative-rel and the input verb are identified (delimitative-rel is an intersective modifier) and this shared label is embedded under the perfective-rel.

$ \boxed{3} $

) to ensure that they apply to the same event denoted by the input verb. The label of the delimitative-rel and the input verb are identified (delimitative-rel is an intersective modifier) and this shared label is embedded under the perfective-rel.

For example (63), we get the MRS representation in (64), where h1 and h2 correspond to the handles

![]() $ \boxed{2} $

and

$ \boxed{2} $

and

![]() $ \boxed{4} $

and e1 to the event variable

$ \boxed{4} $

and e1 to the event variable

![]() $ \boxed{3} $

:

$ \boxed{3} $

:

So the delimitative relation is treated as an intersective modifier of the main relation of the verb, and the perfective relation scopes over both the main relation and the delimitative relation.

Two subtypes of perfective-reduplication-lr are posited: a-le-yi-a-lr and a-le-a-lr, as shown in (65). They inherit the semantic change to the input from perfective-reduplication-lr, but specify the phon value differently. Specifically, a-le-yi-a-lr specifies the middle phonological material as

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le, yi\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

, while a-le-a specifies it as

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le, yi\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

, while a-le-a specifies it as

![]() $ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

only.Footnote 21

$ \left\langle \hskip0.22em le\hskip0.22em \right\rangle $

only.Footnote 21

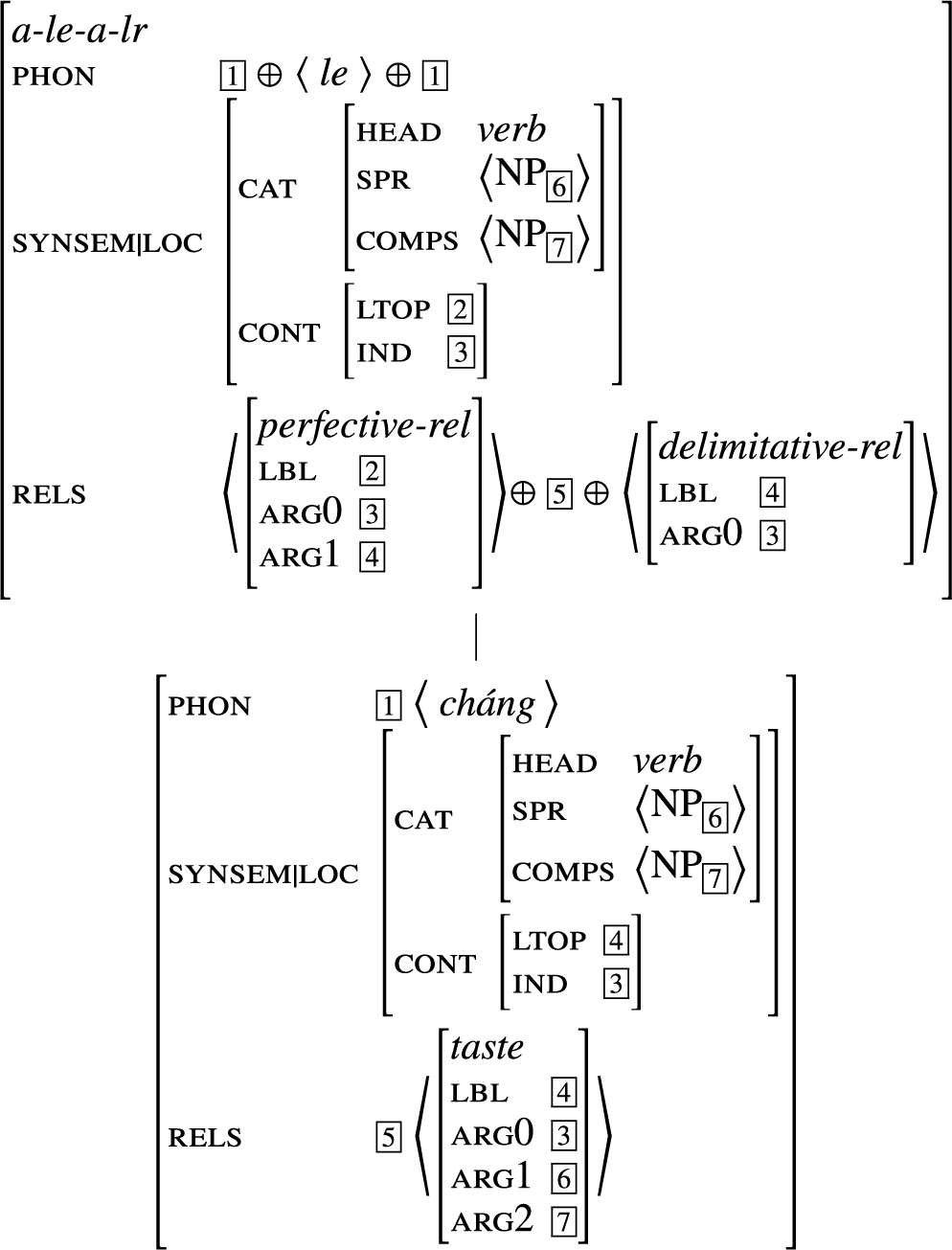

The analysis of (63) is shown in tree format in Figure 3. The lex-dtr is the daughter in the tree.

Figure 3. Analysis of cháng-le-cháng taste-PFV-taste ‘taste the soup a little bit’

The figure shows how the lexical item for cháng ‘to taste’ is inserted as a daughter into the a-le-a-lr lexical rule. The arguments of cháng ‘to taste’ are represented within the spr and the comps list (see Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000: 23 for English) and the respective argument NPs are linked to the arguments of taste: the subject is arg1, the agent, and the object is arg2, the stimulus. See Davis, Koenig & Wechsler (Reference Davis and Müller2024) for more on linking. The part of speech of the lexical item (verb) and the valence information is carried over from the daughter to the mother unchanged. The semantic contribution of the daughter verb, the value of

![]() $ \boxed{5} $

, is inserted into the rels list of the mother as it was specified in the constraints on the type perfective-reduplication-lr in (62). The phon value of the mother is the concatentation of cháng, le and cháng, as specified in the constraint on a-le-a-lr in (65b). The resulting unit cháng-le-cháng then combines with its object forming a VP. This VP is combined with the subject resulting in a complete verbal projection, a sentence. cháng-le-cháng behaves in the same way as the simple cháng.

$ \boxed{5} $

, is inserted into the rels list of the mother as it was specified in the constraints on the type perfective-reduplication-lr in (62). The phon value of the mother is the concatentation of cháng, le and cháng, as specified in the constraint on a-le-a-lr in (65b). The resulting unit cháng-le-cháng then combines with its object forming a VP. This VP is combined with the subject resulting in a complete verbal projection, a sentence. cháng-le-cháng behaves in the same way as the simple cháng.

Since the above-described lexical rules do not constrain the number of syllables of the input verb, but simply reduplicate its phonology as a whole, they can also account for the ABAB and the AB-le-AB forms of reduplication, as long as the input verb is disyllabic. Notice that the lexical rules above also produce AB-yi-AB and AB-le-yi-AB for disyllabic input verbs. Although these forms are considered unacceptable by some authors (Li & Thompson Reference Li and Thompson1981: 30, Hong Reference Hong1999: 275–276, Basciano & Melloni Reference Basciano and Melloni2017: 160, Yang & Wei Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 239), Fan (Reference Fan1964: 269) and Sui (Reference Sui, Finkbeiner and Freywald2018: 143) consider AB-yi-AB and AB-le-yi-AB to be possible, even though they both recognize that these two forms are rare. Indeed, a few examples of AB-yi-AB and AB-le-yi-AB in Old Mandarin (66a–b) and Modern Mandarin (66c–f) were found.

This suggests that even though AB-yi-AB and AB-le-yi-AB might be degraded, they are not ungrammatical per se. The reason for this degradedness is probably phonological, since AB-yi-AB and AB-le-yi-AB contain too many syllables (Fan Reference Fan1964: 274, Zhang Reference Zhang2000: 15, Yang & Wei Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 239, Sui Reference Sui, Finkbeiner and Freywald2018: 143), but we argue that it is not an issue of grammaticality. Thus, they can still be produced via the lexical rules posited above, but are ruled out or degraded due to a general phonological constraint.Footnote 27

AAB, A-yi-AB, A-le-AB, AA-kàn and A-kàn-kàn can also be accounted for by the lexical rules proposed in this section. They can be analyzed as compounds consisting of a reduplicated monosyllabic verb and another element. Specifically, AAB, A-yi-AB and A-le-AB can be considered as the compound of a reduplicated monosyllabic verb (A) and a noun (B).Footnote 28 AA-kàn can be regarded as the compound of a reduplicated monosyllabic verb (A) and the verb kàn ‘look’, whereas A-kàn-kàn is the compound of a monosyllabic verb (A) and the reduplication of kàn ‘look’. A-yi-A-kàn is also possible, though rare, presumably also due to its length. An inquiry in CCL found 55 hits of A-yi-A-kàn. A sample is listed in (67).

Due to the prominent tentative, trying meaning of AA-kàn and A-kàn-kàn, they are not compatible with the perfective aspect marker le semantically, as one usually cannot try something that is already realized. Thus, structures such as A-le-A-kàn and A-kàn-le-kàn are considered pragmatically infelicitous.

The current analysis provides a unified account for all forms of delimitative verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. Like in Fan, Song & Bond (Reference Fan and Müller2015), yi is handled as a phonological element which does not make any contribution to the semantics, and an inheritance hierarchy is used to capture the commonalities among different forms of reduplication. But the present proposal also reflects the connection between the reduplication and aspect marking via multiple inheritance. This account makes use of a semantic mechanism, which correctly rules out aspect marking with forms other than le. By providing a semantic explanation, this mechanism seems less ad hoc than the one used in Fan, Song & Bond (Reference Fan and Müller2015), which simply assumed that the reduplication cannot combine with aspect information. The present approach also has a broader coverage of the forms of verbal reduplication than the one in Fan, Song & Bond (Reference Fan and Müller2015). Furthermore, all the forms are derivable from the lexical rules proposed here, so that there is no need to resort to irregular lexicon entries, and the productivity of these forms is correctly captured. In sum, the analysis proposed in this paper possesses greater explanatory power and resolves the problems of previous studies.

5. Conclusions

The current study provides a new HPSG account for delimitative verbal reduplication in Mandarin Chinese. We present empirical evidence that reduplication is possible with all verb classes. We give a semantic explanation for the incompatibility of reduplication with aspect markers other than le. We argue that reduplication is better analyzed as a morphological rather than a syntactic process. We model reduplication as a lexical rule, and the different forms of reduplication are captured in an inheritance hierarchy using underspecified lists. The interaction between verbal reduplication and aspect marking is handled by multiple inheritance. This analysis is compatible with both mono- and disyllabic verbs, so that all productive forms of reduplication are derivable by lexical rules. The analysis is implemented as part of a computer-processable grammar of Mandarin Chinese. The analysis is implemented as part of the CoreGram project (Müller Reference Müller2015) in a Chinese grammar (Müller & Lipenkova Reference Müller, Lipenkova, Lai and Chui2013) in the TRALE system (Meurers, Penn & Richter Reference Meurers, Radev and Brew2002, Penn Reference Penn and Scott2004).

Acknowledgements

We are really grateful for the comments of several reviewers of the Journal of Linguistics and of the HPSG 2021 conference. We also thank Elizabeth Pankratz for comments on an earlier version of this paper. This work was supported by a grant from the DFG to the project SFB 1412 A04.

Appendix A. Analysis based on the aspectual system by Tsai (Reference Tsai2008 )

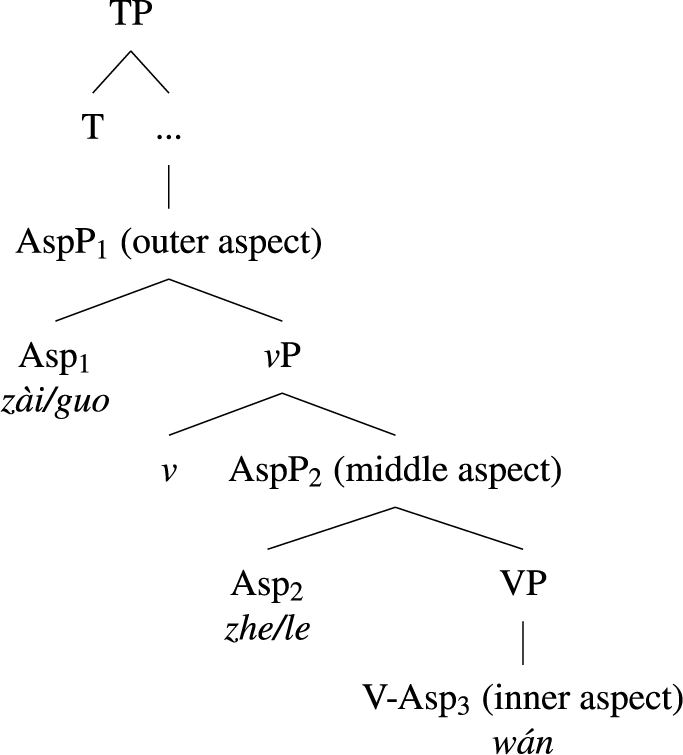

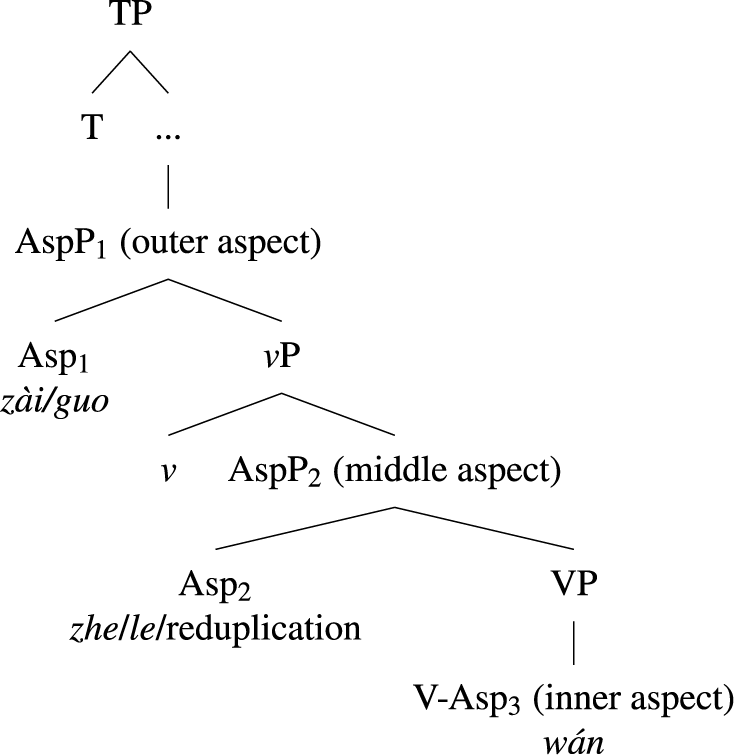

Yang & Wei (Reference Yang, Wei and Erlewine2017: 229) claim that reduplication can be analyzed as an aspect marker following the structure of Mandarin Chinese aspects proposed by Tsai (Reference Tsai2008). Tsai (Reference Tsai2008) provides the syntactic analysis for aspect markers in Mandarin Chinese as shown in Figure 4.Footnote 29 He observes the so-called incompleteness effect, namely that a minimal sentence, which only contains a verb marked by zhe ‘dur’, le ‘pfv’ or wán ‘compl’ and its arguments, seems incomplete without further sentential elements such as the sentence final particle le or a temporal adverbial like gāngcái ‘just now’ (68). In contrast, a minimal sentence with a verb marked by zài ‘prog’ or guo ‘exp’ and its arguments can stand alone (69).

Figure 4. Structure of the aspectual system in Mandarin Chinese according to Tsai (Reference Tsai2008: 683)

He thus proposes three aspect positions under TP. zài ‘prog’ and guo ‘exp’ reside under Asp

![]() $ {}_1 $

, while zhe ‘dur’ and le ‘pfv’ under Asp

$ {}_1 $

, while zhe ‘dur’ and le ‘pfv’ under Asp

![]() $ {}_2 $

, as illustrated in Figure 4.Footnote 30

$ {}_2 $

, as illustrated in Figure 4.Footnote 30

Turning to reduplication, a minimal sentence with reduplication also seems incomplete (70). Based on this, the reduplicant should reside under Asp

![]() $ {}_2 $

, as illustrated in Figure 5.

$ {}_2 $

, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Position of reduplication according to the aspectual system in Tsai (Reference Tsai2008)

This analysis would result in a mismatch between syntax and semantics, in the sense that the aspect markers that belong to the same semantic group do not occur in the same syntactic position. Even though le ‘pfv’, guo ‘exp’ and reduplication all mark perfective aspects (Section 2.3.3, Dai Reference Dai1997, Xiao & McEnery Reference Xiao and McEnery2004), guo ‘exp’ is situated under Asp1, while le ‘pfv’ and reduplication are under Asp2. Similarly, zài ‘prog’ and zhe ‘dur’ are both imperfective aspects but also occur in different syntactic positions. We prefer a uniform treatment.

Appendix B. yi and le

A reviewer suggests that the fact that only yi and le can appear in between reduplication seems somewhat arbitrary, and it is not evident why certain elements are permissible while others are not. We think that there might be historical and phonological reasons.

le ‘pfv’ marks the perfective aspect. The reason for le ‘pfv’ being the only aspect marker compatible with reduplication is explained in Section 2.3.3.

As for yi ‘one’, its use stems from the historical development of delimitative verbal reduplication but is synchronically opac. Zhang (Reference Zhang2000: 13–15) shows that delimitative verbal reduplication originates from the “V + numeral + verbal classifier” phrase, where the verbal classifier is borrowed from a verb of the same form, as shown in (71) from Sòngdài juàn: Xūtáng Héshang yǔlù [The Song dynasty volume: Quotations from Abbot Xutang] p. 387 as cited in Zhang (Reference Zhang2000: 12).

Here the numeral refers to the actual number of the action taking place and can be any number. This evolved into the structure of V-yi-V (or A-yi-A), which does not express the actual number of the action anymore, but simply conveys that the action happens in a short period of time or for only few times. Consider (72) from Sòngdài juàn: Zhāng Xié zhuàngyuán [The Song dynasty volume: Top graduate Zhang Xie] p. 519 as cited in Zhang (Reference Zhang2000: 13).

In this case, yī ‘one’ cannot be replaced by other numerals. Since V-yi-V does not express the actual number of the action anymore, it became possible to delete the yī ‘one’, hence the use of the VV (or AA) form, too.

Synchronically, A-yi-A has the same meaning as AA and both do not refer to the actual number of the event denoted by the verb. This means that yī ‘one’ in A-yi-A does not contribute any specific meaning to the structure and is only there as a historical remnant. In this sense, yī ‘one’ appearing in between the reduplication is synchronically arbitrary.

Besides the obvious conceptual reason that yī ‘one’ is taken to mean ‘little/few’, there might be a phonological explanation for yī ‘one’ rather than other numerals is used in the A-yi-A structure. In Mandarin Chinese, one form of intensifying reduplication is A-li-AB e.g. hú-li-hútú ‘confused-li-confused’, where the li is fixed and also does not bear any meaning. Sui (Reference Sui, Finkbeiner and Freywald2018: 137) assumes that this syllable is filled with li because the open syllable li is a relatively unmarked phonological constituent (Yip Reference Yip1992) and the second syllable in A-li-AB occupies an unstressed position. We can see the similarities between li in A-li-AB and yi in A-yi-A: they are both relatively unmarked and occupy an unstressed position. This can also make it easier for yī ‘one’ rather than other numerals to become part of a fixed structure. But a phonological account is out of the scope of this paper and has to be left for further research.