Introduction

The field of rural history has undergone a significant historiographical evolution, shifting from a narrow focus on agrarian economies and land tenure systems to a multi-dimensional and interdisciplinary approach. Defining the ‘rural’ remains a central conceptual challenge in rural history, as the term has been used in varied and shifting ways across time and disciplines. Earlier historiography often equated the rural with agricultural production and countryside economies, whereas later scholarship has emphasized its cultural, social, and symbolic dimensions. This fluidity complicates comparison and risks conflating unlike phenomena, since both historians and historical actors employed distinct vocabularies – such as village, peasantry, or country – that carried different meanings across contexts.

Early studies concentrated on landholding, tenancy, and agrarian conflict structures, often emphasizing class, production, and modernization as core themes.Footnote 1 Over time, this lens expanded to incorporate questions of power, identity, and resistance, primarily through micro-historical and regional studies of social conflict, protest, and everyday life in rural communities.Footnote 2 Simultaneously, the role of underrepresented actors – such as women, racial minorities, and servants – became central to analyses of labour, property, and legal structures, particularly in post-emancipation and colonial settings.Footnote 3

The early development of rural history as an academic field was marked by significant institutional, intellectual, and cultural difficulties that shaped its subsequent trajectory. In its formative stages, particularly during the 1960s to 1980s, rural history struggled to achieve recognition as a legitimate and autonomous branch of historical inquiry, often overshadowed by the more established domains of political, economic, and urban history. Within university settings, it was commonly dismissed as a derivative or antiquarian pursuit – concerned primarily with the technicalities of agriculture, land tenure, and rural economy – rather than as a field capable of addressing broader social or cultural processes. The dominance of what critics termed a ‘plough and cow’ tradition of agricultural historiography reinforced an insular and empiricist ethos, resistant to theoretical innovation and comparative analysis. Early scholars who sought to move beyond these boundaries encountered scepticism, even hostility, from senior academics who regarded interdisciplinary approaches – drawing on sociology, anthropology, geography, and literary studies – as intellectually suspect or methodologically inappropriate. In the British context, especially, the institutional conservatism of agricultural history associations and their affiliated journals created structural barriers to publishing new forms of rural research, while the limited presence of rural history in graduate curricula constrained the training of new specialists. Attempts to broaden the field’s scope – to include issues of class relations, gender divisions of labour, and rural protest – were often met with institutional opposition; some pioneers, particularly those working on rural women or social conflict, faced explicit discouragement and professional risk. Despite such resistance, a gradual redefinition took place through scholarly persistence, informal networks, and the establishment of interdisciplinary conferences and working groups that connected historians, geographers, archaeologists, and sociologists. This growing intellectual coalition eventually culminated in the founding of Rural History: Economy, Society, Culture in 1990, which crystallized the ambitions of a new generation seeking to reposition the rural not as a residual or nostalgic domain but as a vital arena for understanding historical change. The difficulties of these early decades thus reveal how the emergence of rural history was as much a struggle for academic legitimacy as it was a transformation of historical imagination, redefining both the boundaries of the discipline and the meaning of the rural itself.Footnote 4

Since the early 2000s, rural history has become increasingly global and thematic, with scholars exploring issues such as ecological transformation, cultural identity, cooperative movements, and the politics of memory. Comparative approaches across Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia have deepened insights into the rural past and challenged Eurocentric narratives of development and decline.Footnote 5 Recent works, such as Freire-Esparís (2007) and Muñoz-Sougarret (2007), demonstrate the integration of local case studies within broader socio-political frameworks.Footnote 6 Others, like Gómez-Benito (2007), reflect on rural imaginaries’ cultural and intellectual legacies.Footnote 7 Then, rural history today is defined by methodological diversity, cross-cultural comparison, and a sustained interest in the lived experiences of rural actors across time and geography.Footnote 8 A new era of rural history has emerged, but despite the publication of numerous articles, a comprehensive and insightful study remains elusive for researchers, doctoral students, and rural history enthusiasts. This research seeks to fill this gap by answering these questions:

-

RQ 1. What is the current overall state of research in rural history regarding volume, disciplines, and citation?

-

RQ 2. What key themes and research communities exist within rural history based on citation and keyword patterns?

-

RQ 3. What are the main trends and gaps in rural history research that suggest areas needing more study?

-

RQ 4. What are the most influential articles shaping rural history scholarship and its future directions?

Despite the depth and diversity of rural history scholarship – spanning themes from land use and estate management to gender, class, and postcolonial dynamics – identifying overarching trends and research gaps remains challenging due to the field’s thematic breadth and methodological fragmentation. Numerous studies offer rich qualitative insights into specific case studies, such as Briggs (2023) on medieval England,Footnote 9 Destenay (2023) on Ireland during WWI,Footnote 10 and Byrne (2021) on spatial language in rural Australia,Footnote 11 while others like Andreoni (2021) and Bayly (2021) analyze economic and institutional developments across different regions and periods.Footnote 12 These contributions demonstrate the field’s growing temporal, geographical, and thematic scope, as seen in works on gender and masculinity,Footnote 13 environmental regulation,Footnote 14 and religious architecture.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, because these studies are often siloed by region, theme, or time period, it is not easy to systematically evaluate the state of the field or track the evolution of rural historiographical priorities across time and space. To address this problem, applying quantitative methods – particularly bibliometric analysis – offers a promising strategy for mapping scholarly production, measuring thematic concentration, and identifying under-researched areas. While qualitative and mixed-methods research has generated deep contextual knowledge, bibliometrics can synthesize this fragmented landscape by highlighting citation patterns, co-authorship networks, and keyword clusters across journals and decades.Footnote 16 Ultimately, such an approach can enhance interdisciplinary dialogue and foster more cohesive research agendas in rural history by revealing what has been studied and remains overlooked.

Methodology

The bibliometric methodology illustrated in Figure 1 outlines a rigorous and systematic approach to data collection and screening in rural history, aimed at producing a coherent and analytically robust corpus of scholarly literature. Theoretically, bibliometrics provides a quantitative lens through which patterns of scholarly communication, citation behaviour, and conceptual convergence can be understood, offering historians an empirical means to trace shifts in historiographical emphasis over time. Practically, its application in historical research enables the systematic mapping of how certain themes – such as agrarian transformation, rural modernity, or environmental change – gain or lose prominence within academic discourse.Footnote 17 Drawing on Scopus as the primary data source, the initial search strategy employed a keyword-based query – specifically, ‘rural histor*’ – which yielded a preliminary set of 822 articles. This broad search was refined through successive filtering stages, underscoring thematic relevance and disciplinary precision. The first level of refinement limited the dataset to those articles in which ‘rural histor*’ appeared as a keyword, reducing the total to 578. This stage ensured that rural history was not merely incidental but central to the thematic focus of the articles. Further screening by subject area (specifically to Social Sciences and Arts & Humanities) narrowed the corpus to 557 articles, reflecting an intention to situate rural history firmly within humanistic and socio-historical discourses rather than purely agricultural or environmental domains.

Figure 1. The methodological data collection and analysis strategy.

The selection was refined by excluding non-research outputs, such as reviews and editorials, by limiting the document type to ‘research articles’, which yielded 436 records. These articles underwent normalization for bibliometric analysis. The resultant dataset represents a curated, thematically cohesive, and epistemologically consistent corpus that is methodologically sound for further visualization and network analysis. The use of diverse analytical software – including CiteSpace (v6.3.R1), VOSviewer (v1.6.20), R programming environment (v3.6.3), and the bibliometrix package (v3.1.4) – further strengthens the methodological rigour by enabling multi-dimensional mapping of co-authorship patterns, keyword co-occurrences, citation networks, and thematic evolution.Footnote 18 Notably, the dataset displays strong linguistic dominance by English-language publications (345 of 436 articles), though a significant minority appears in Spanish (70), reflecting the field’s partial internationalization beyond Anglophone academia.

The Open Access distribution (with 99 articles accessible) indicates a growing trend toward research democratization, yet suggests that a substantial portion of rural history literature remains behind paywalls. The affiliation and funding sponsor data also reveal interesting institutional geographies: institutions such as the University of Leicester and the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) emerge as key contributors, while funding agencies like the Leverhulme Trust and the European Commission highlight a European-centric funding ecosystem. Including subject areas such as Agricultural and Biological Sciences and Earth and Planetary Sciences (though secondary in number) further attests to the field’s latent interdisciplinarity. This approach reveals the thematic and institutional contours of rural history and its epistemological foundation in the social sciences and humanities, providing a comprehensive methodological framework for subsequent quantitative and qualitative syntheses.

Results

Performance Information (RQ 1)

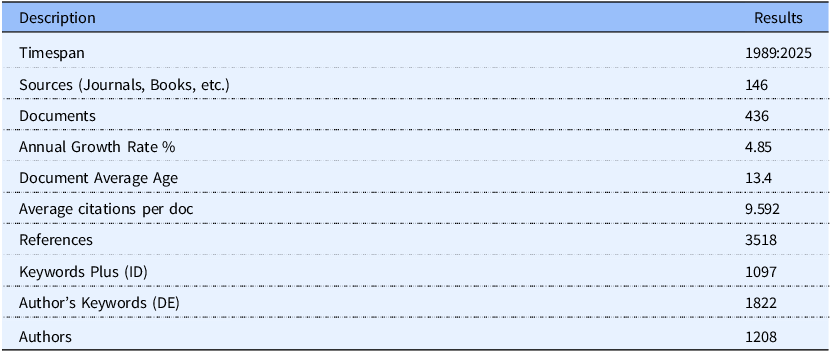

Table 1 provides a quantitative overview of the scholarly landscape in rural history from 1989 to 2025, highlighting significant trends in its academic development. With 436 documents from 146 outlets, the field demonstrates a steady annual growth rate of 4.85%, indicating a consistent expansion of scholarly interest. The average document age of 13.4 years suggests a balance between foundational texts and more recent contributions, while the average of 9.592 citations per document points to moderate academic influence. The substantial number of references (3,518) and the diversity of both ‘Keywords Plus’ (1,097) and ‘Author’s Keywords’ (1,822) reflect a thematically rich and interdisciplinary discourse. Moreover, the involvement of 1,208 authors underscores a broad and collaborative scholarly community, suggesting that rural history remains a dynamic and evolving field of inquiry with increasingly complex methodological and theoretical orientations. Figure 2 illustrates the temporal evolution of scholarly output and impact in rural history from 1989 to 2025, revealing significant fluctuations in annual article production and the mean number of citations per article. Initial productivity was modest, with sporadic publication until the mid-1990s, when a marked increase occurred – particularly notable in 1996 (14 articles) and peaking intermittently in subsequent years, such as 2009 (23 articles) and 2019 (24 articles). Citation impact, however, does not correlate linearly with output; instead, it exhibits peaks in specific years, notably 1992 (mean of 61 citations), 2010 (23.94), and 2012 (32.2), suggesting the publication of particularly influential works. Post-2020, although production remains high, mean citation rates drop sharply – likely reflecting citation lag for recent publications. This temporal discrepancy between quantity and citation impact underscores both the maturing of the field and the time-dependent nature of academic influence, indicating that foundational or paradigm-shifting contributions remain relatively rare but highly influential within the broader corpus.

Figure 2. Annual production and citation.

Table 1. Primary information about the collected documents

Figure 3, a three-field plot in the form of a Sankey diagram, provides a comprehensive visualization of the interplay between sources (SO), authors’ countries (AU_CO), and research descriptors or keywords (DE) in the scholarly landscape of rural history.Footnote 19 The diagram reveals a concentration of intellectual production and influence from a relatively small number of key journals – particularly Rural History: Economy, Society, Culture, Historia Agraria, and the Journal of Rural Studies – which act as central publishing venues for scholars in this domain. The dominance of the United Kingdom as a source of authorship is immediately evident, with strong flows connecting it to both leading journals and a wide array of descriptors, such as ‘rural history’, ‘historical geography’, and ‘historical perspective’, underscoring its pivotal role in shaping the field’s historiographical frameworks.

Figure 3. Three-field plot or Sankey diagram.

The term rural has always carried a degree of conceptual fluidity, encompassing a spectrum of meanings that shift across temporal, spatial, and disciplinary contexts. In the context of this study, the category of ‘rural history’ is approached not as a fixed or self-contained field but as a dynamic historiographical formation that has evolved through dialogue with economic, social, environmental, and cultural histories.Footnote 20 While the methodological framework adopted here relies primarily on journal titles and disciplinary self-identification to map the thematic and institutional trajectories of the field, it is important to acknowledge that many significant contributions to the study of the rural past have appeared outside journals explicitly devoted to rural or agricultural topics. Influential articles published in mainstream venues such as Past & Present, the English Historical Review, and the Transactions of the Royal Historical Society have played a pivotal role in shaping debates on rural social relations, peasant protest, enclosure, agrarian capitalism, and the moral economies of the countryside.Footnote 21 These works – though not always categorized under the label of ‘rural history’ – nonetheless engage profoundly with rural experience and thus constitute an integral, if methodologically diffuse, part of its intellectual terrain. To undertake a comprehensive inclusion of such dispersed scholarship would be an immense, perhaps unmanageable, undertaking, given the porous boundaries that have long characterized the rural as an analytical and archival category. Nevertheless, flagging their presence underscores the porousness of the field and the extent to which ‘the rural’ operates less as a disciplinary perimeter than as a conceptual crossroads – a site where historians of class, environment, gender, and culture have continually intersected, sometimes without consciously identifying as rural historians.

Spain and the United States are also significant contributors, with Historia Agraria notably associated with Spanish scholarship, reflecting regional historiographical traditions and interests. Moreover, while European countries like Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands contribute to the field, their scholarly output appears more dispersed in terms of journal choice and thematic focus, indicating a more diversified and perhaps fragmented research orientation. On the right side of the diagram, the dominant descriptors such as ‘rural history’, ‘historical geography’, ‘rural society’, and ‘nineteenth century’ suggest a thematic preoccupation with long-term socio-spatial transformations and the embeddedness of rural studies within both economic and cultural historiography. The recurrence of geographical identifiers like ‘Europe’, ‘United Kingdom’, and ‘Eurasia’ in the descriptor column signals a strong regional anchoring of research, while terms such as ‘rural area’ and ‘rural society’ reinforce the field’s enduring interest in the spatial and social dimensions of the countryside. This Sankey diagram, therefore, not only maps the structural relationships among publishing venues, national scholarly communities, and thematic focuses but also reflects the intellectual architecture of rural history as a field deeply rooted in regional historiographies, yet increasingly interconnected through transnational scholarly discourse.

Cluster & Trend Analysis (RQ 2-3)

Figure 4, a timeline view generated through CiteSpace, presents a richly layered analysis of thematic evolution within rural history, highlighting key clusters of scholarly activity over time. The clusters’ visual structure and temporal distribution reveal continuity and transformation in research foci, aligning with broader historiographical trends and regional historiographies.Footnote 22 The most foundational cluster (#0), centred on rural history, the nineteenth century, and socio-economic conditions, has its mean publication year around 2001, suggesting an early consolidation of rural history as a formalized field, primarily oriented toward Western and Southern European contexts, with Spain and broader Eurasian regions as notable spatial foci. This cluster’s emphasis on economic history, power relations, and social conflict points to a socio-structural analytical framework, rooted in historical materialism and influenced by European agrarian historiography.

Figure 4. Timeline view analysis.

In contrast, more recent clusters, such as #1 and #4, reflect a broadening of scope and a deepening engagement with cultural, political, and justice-oriented themes. Cluster #1, with a mean year of 2014, incorporates archaeological surveys, cultural influences, and the Ottoman Empire, illustrating a shift toward interdisciplinary methods and non-Western rural histories, while also intersecting with critical themes such as colonialism and social movements. Similarly, Cluster #4, thematically tied to social justice, land markets, and protest, engages with rurality through the lens of popular resistance and governance in places such as South America and Chile, demonstrating a global shift in rural historiography. This temporal and thematic diversification continues in clusters like #5 (agrarian reform) and #6 (social class and rural health), which foreground rural development and institutional change, especially in North American, Australian, and Latin American contexts. These clusters reflect a growing concern with land tenure, indigenous rights, and the intersection of rural transformation with health and legal frameworks – areas that have been previously marginalized in mainstream rural historiography.

Furthermore, cluster #2 integrates historical geography with archaeological evidence, grounding rural historical inquiry in spatial methodologies, especially concerning the United Kingdom and broader Western Europe. Meanwhile, clusters #3 and #6 emphasize rural population and socio-economic factors, linking demographic shifts with identity, urbanization, and class questions, and situating rural history within broader discourses on modernity and migration. Notably, cluster #7 represents a methodological shift, focusing on documentary sources, demographic history, and spatial analysis, underscoring the role of quantitative and digital humanities tools in deepening our understanding of rural pasts. Lastly, cluster #8, which deals with agricultural history and political economy – particularly on African American rural experiences in the US – reflects an emergent strand of scholarship attentive to race, marginality, and post-slavery agricultural regimes, particularly in places like Louisiana.

Figure 4 maps a dynamic and increasingly pluralistic intellectual terrain. While earlier research was dominated by European agrarian concerns grounded in socio-economic paradigms, the field has progressively expanded to incorporate postcolonial, cultural, environmental, and spatial dimensions, demonstrating a clear evolution from structural to multi-scalar and intersectional approaches. The timeline structure, further colour-coded by publication periods, visually captures the field’s chronological depth and shifting epistemological contours, illustrating how rural history has matured into a globally attuned and methodologically diverse scholarly domain.

Figure 5 provides a comprehensive longitudinal visualization of thematic evolution in rural history from 1989 to 2025, illustrating the shifting focus of scholarly attention and the emergence of new thematic priorities over time. Organized into four chronological segments (1989–2004, 2005–2012, 2013–2019, and 2020–2025), the Sankey diagram and associated thematic evaluation metrics trace the interconnected trajectories of key topics, regions, and methodological approaches. During the earliest phase (1989–2004), research was primarily centred on foundational themes, including rural population, settlement patterns, rural society, and historical geography, with strong regional emphases on areas such as New Zealand, Catalonia, China, and the United Kingdom. These early studies laid the groundwork for later inquiries, embedding rural history within demographic and spatial frameworks and highlighting issues such as rural politics and socio-economic structure. This period demonstrated a concern with agrarian livelihoods and rural demography, with moderate thematic diversity but limited transnational dialogue.

Figure 5. Thematic evaluation.

In the 2005–2012 segment, the field expanded its thematic and geographical scope. Rural history remained central, but was now deeply embedded within broader spatial and regional clusters such as Eurasia, North America, and South America. This period also witnessed the emergence of demographic history and a refined interest in rural population dynamics, signalling a move toward a more data-informed and comparative rural historiography. This expansion aligned with a historiographical shift toward recognizing regional diversity and postcolonial contexts. The connections between clusters in this phase suggest a deepening interdisciplinary engagement, where economic, political, and cultural variables intersect with spatially grounded inquiries.

The period from 2013 to 2019 represents a methodological and conceptual intensification in rural history scholarship. A marked diversification is visible, with the rise of topics such as migration, fertility, cultural history, colonialism, land tenure, and political history. Notably, the category of rural history remains a dominant conduit through which other themes flow, reflecting its institutional centrality within the field of history. However, the field has become increasingly global and reflective, with thematic incursions into regions such as Cyprus, Hungary, and Italy and critical theoretical domains including historiography, social movements, and agricultural labour. It is also supported by the thematic evaluation data, which reveals a strong presence of topics such as colonialism (Inclusion Index: 0.33), migration (1.00), social justice, cultural influence, and land reform. Such topics underscore the field’s responsiveness to contemporary concerns, including inequality, decolonization, and climate resilience.

In the most recent segment (2020–2025), the diversification of themes reaches its apex, reflecting the field’s maturity and increasing responsiveness to global crises and local historical narratives. Alongside the continued prominence of rural history, this period emphasizes historical perspective, cultural heritage, social movement, and collective action. The re-emergence of regions such as Chile, Ireland, and India, along with concepts like pastoralism, planning history, and cultural history, marks a decisive turn toward global comparative rural historiography and critical rural studies. The Weighted Inclusion Index and Stability Index from the thematic evaluation further underscore the dynamism of this period, with high values for themes such as historiography (1.00 stability) and cultural history (1.00 inclusion), as well as migration, pastoralism, and fertility, all of which suggest robust, sustained engagement and thematic resilience. The presence of low-inclusion but high-occurrence clusters (e.g., nineteenth century; agricultural history; socio-economic conditions) further indicates an ongoing tension between traditional empirical foundations and emerging critical agendas.

Figure 5 reveals a clear diachronic trajectory in rural history scholarship, from foundational demographic and geographical themes to a rich tapestry of transdisciplinary concerns informed by postcolonial, cultural, environmental, and political perspectives. The field’s evolution demonstrates increasing complexity, thematic inclusivity, and global scope, suggesting that rural history has transformed into a dynamic site for interrogating broad historical processes, including capitalism, colonialism, migration, land use, and rural resistance. This nuanced historiographical shift reflects internal disciplinary developments and external sociopolitical pressures, positioning rural history as a vital and responsive field within the humanities and social sciences.

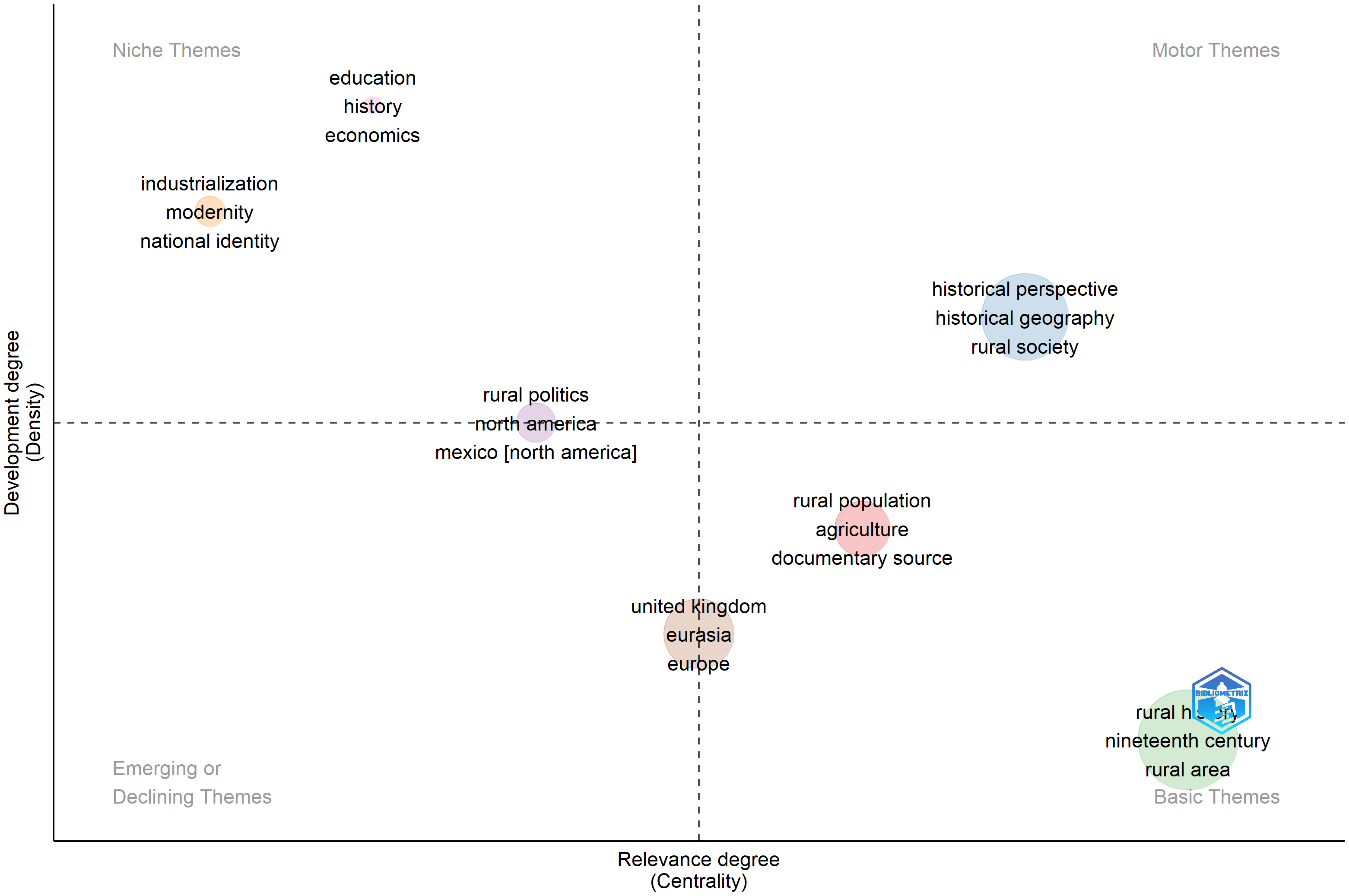

Figure 6 presents a thematic map that spatially organizes scholarly themes in rural history based on two crucial metrics: Callon Centrality (indicating relevance to the broader research field) and Callon Density (indicating the internal development of the theme). This map reveals four thematic quadrants – Motor Themes, Niche Themes, Basic Themes, and Emerging or Declining Themes – each indicative of varying degrees of academic maturity and interconnectivity. Notably, rural history, the nineteenth century, and rural areas are positioned within the Basic Themes quadrant, characterized by low density but high relevance. This placement underscores their foundational role in the field. While these themes are conceptually central and widely cited (as evidenced by rural history’s exceptionally high Cluster Frequency of 1398 and Callon Centrality of 18.10), they lack thematic innovation or internal complexity, suggesting a mature yet methodologically static domain.

Figure 6. Thematic map.

Conversely, the Motor Themes quadrant is populated by historical perspective, historical geography, and rural society – themes that not only have high centrality but also exhibit strong internal development (with Callon Densities above 40 and high Cluster Frequencies, especially for historical perspective at 697). These themes are evidently at the forefront of rural history scholarship, serving as intellectual engines that integrate and propel the field forward. Their methodological richness and thematic relevance reflect broader interdisciplinary engagement, particularly with cultural, spatial, and social historiographies.

The Niche Themes quadrant encompasses specialized yet less interconnected topics, including education, history, economics, industrialization, modernity, and national identity. Despite their high density – most notably in education, with a Callon Density of 67.4, and industrialization at 50.8 – these themes exhibit low centrality, indicating that they are self-contained and potentially isolated from the main discursive currents of rural historiography. Their development suggests deep but narrowly focused scholarly interest, often aligned with regionally or temporally specific studies that may not significantly influence the broader field.

Finally, the lower-left quadrant – Emerging or Declining Themes – contains topics such as rural politics, North America, Mexico, and broader regional identifiers like Europe and Eurasia. These themes exhibit low density and low centrality, reflecting either nascent stages of scholarly inquiry or diminishing relevance within current academic discourse. Interestingly, despite its historical centrality, the United Kingdom appears near this quadrant’s border, suggesting a relative decline in thematic innovation within UK-focused rural history or a shift in scholarly interest toward more global or transnational perspectives.

This thematic map reveals a field in dynamic transformation. While traditional foundations such as rural history and the nineteenth century remain structurally important, the thematic vitality of historical geography, rural society, and historical perspective suggests that the intellectual energy of the field is increasingly channelled through critical, spatial, and socially engaged methodologies. Simultaneously, developing niche domains and regional themes indicates a diversification of rural history into more pluralistic, context-sensitive, and interdisciplinary directions.

The overlay visualization networks in Figure 7 offer a compelling diachronic insight into rural history’s intellectual structure and thematic progression as a research field.Footnote 23 The first image (left) captures the thematic constellation from approximately 2005 to 2016, while the second image (right) extends the temporal scope up to 2020, thereby revealing notable shifts in scholarly priorities. In the earlier period, central clusters revolved around enduring historiographical themes, such as rural history, the nineteenth century, rural society, and the twentieth century, often embedded within the analytical frameworks of historical geography, social history, and cultural history.Footnote 24 These core concepts are surrounded by more temporally and politically charged topics such as social movement, collective action, and colonialism, suggesting a transition in scholarly interest toward social and political contestations in rural contexts. The intensity of newer terms, such as urban history, human settlement, and agricultural production – marked in darker purple – indicates a growing engagement with interdisciplinary and socio-environmental concerns.

Figure 7. Overlay visualization network.

In contrast, the second visualization reveals the field’s clear expansion and diversification post-2016. While canonical themes such as rural history, agricultural history, and rural population remain robust, the network becomes significantly more saturated with concepts reflecting broader global and structural concerns, including governance approaches, natural resources, environmental protection, indigenous populations, and economic growth.Footnote 25 Importantly, the appearance and clustering of terms like capital, gender role, violence, and racism reflect a paradigmatic shift in rural history toward a more critical, intersectional analysis that integrates the dynamics of power, identity, and inequality. This latter period also exhibits increasing methodological and epistemological complexity, as evident in the inclusion of terms such as GIS, academic research, and strategic approach, indicating a shift toward digital and interdisciplinary methodologies.

The contrast between the two maps illustrates the evolution of rural history from a field anchored in classical socio-economic and political history to one that now incorporates transnational, environmental, and cultural dimensions. There is an evident trajectory from Eurocentric case studies and traditional agrarian historiography toward more global, inclusive, and methodologically diverse inquiries. This diachronic development demonstrates thematic broadening and a methodological maturation that aligns rural history more closely with contemporary debates in environmental humanities, critical geography, and decolonial studies.

Reference Analysis (RQ 4)

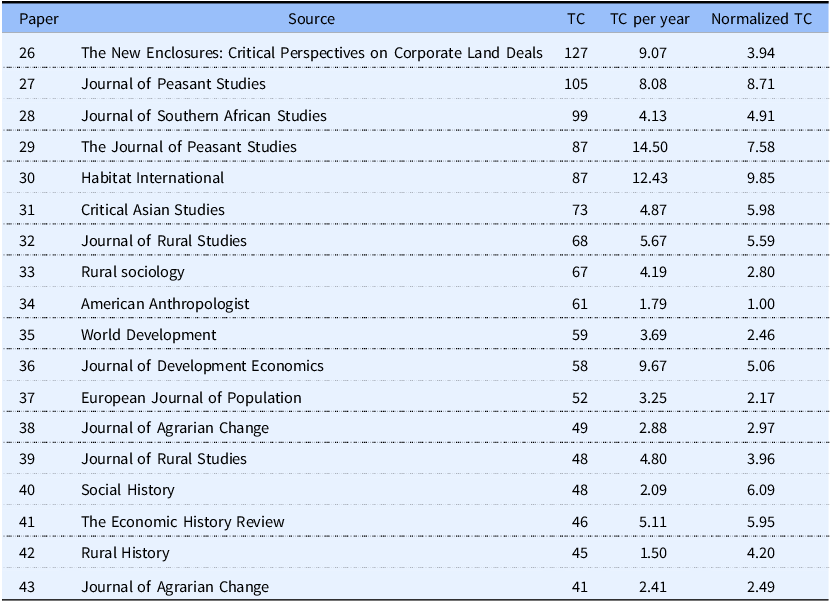

The reference analysis in Table 2 reveals significant insights into the intellectual contours and thematic priorities of scholarly production in rural history, highlighting a decisive turn toward transdisciplinary, globally situated, and politically engaged research. The most influential articles – judged by total citations (TC), citations per year (TC/year), and normalized citations – underscore a dominant concern with land, livelihood, spatial transformation, and power relations within rural contexts. At the apex of this influence is White et al. (2013), whose work on corporate land deals, published in The New Enclosures, typifies the critical agrarian studies tradition, as it interrogates the dynamics of dispossession and accumulation in the global South. Closely following is Ye et al. (2013), also published in the Journal of Peasant Studies, which explores internal migration and the “left-behind” populations in China, thus reflecting a growing concern with demographic mobility, social fragmentation, and structural inequality as outcomes of rural transformation under late capitalism. Notably, the prominence of O’Laughlin (2002) and Peschard & Randeria (2020) further emphasizes the enduring salience of historical materialist perspectives and political ecology in rural historiography, particularly in the Global South, where questions of proletarianization, resistance, and seed activism emerge as central to understanding rural agency and contestation.

Table 2. The most influential articles

Additionally, the high normalized citation rates of Hu et al. (2019) and Lewis & Severnini (2020) point to a growing methodological sophistication and empirical innovation in spatial and infrastructural studies. Hu et al.’s work offers a multi-dimensional view of rural spatial restructuring in China. In contrast, Lewis and Severnini employ historical economic methods to examine the long-term impacts of rural electrification in the US – a study exemplifies the integration of environmental history, development economics, and rural sociology. Similarly, Verbrugge (2016) and Reyes-García et al. (2014) demonstrate a sustained interest in resource governance, indigenous land rights, and artisanal economies, further testifying to the maturation of rural history as a field that engages with both micro-level ethnographic inquiry and macro-structural analysis.

It is also worth noting this influential corpus’s temporal and thematic diversity. Earlier foundational contributions, such as those by Graffam (1992) and Hindle (1996), explore long-term continuities in rural social structures and pastoralism, highlighting rural life’s archaeological and demographic substrates. These are complemented by more recent works, such as de Haas (2017), who quantitatively reconstructs rural welfare in colonial Africa, reflecting an epistemic shift toward mixed-methods and data-driven approaches within historical inquiry. These articles reflect a vibrant and evolving field wherein rural history is no longer confined to the margins of national historiographies but is increasingly shaped by interdisciplinary dialogues with anthropology, development studies, geography, political ecology, and feminist theory. The diversity of geographic foci – from Mozambique to China, from the Bolivian Amazon to colonial Uganda – further suggests that rural history is now articulated through a globally interconnected framework, attentive not only to the longue durée but also to contemporary crises of land, labour, and livelihood.

Discussion

The collective analysis of all research questions (RQs 1–4) reveals a rural history field that has evolved from a regionally anchored, socioeconomically focused discipline into a globally engaged, methodologically diverse, and thematically expansive domain. RQ1, addressed through Table 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3, establishes the field’s steady growth, moderate citation impact, and strong international collaboration, especially among scholars from the UK, Spain, and the US, while confirming the centrality of key journals and thematic consistencies around historical geography and rural society. RQs 2 and 3, explored through Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7, further deepen this understanding by charting the field’s intellectual trajectory and thematic diversification. The timeline and thematic evaluations (Figures 4 and 5) illustrate how rural history has evolved from foundational studies of population and land use to more critical, interdisciplinary concerns, such as colonialism, social justice, and indigenous rights, with an increasing emphasis on cultural, environmental, and digital methodologies. Figure 6’s thematic map reinforces this by identifying “motor themes” like historical perspective and rural society as intellectually central and methodologically advanced, while foundational topics such as “rural history” and “nineteenth century” remain vital but exhibit less internal innovation. Figure 7’s overlay visualization confirms this diachronic expansion, illustrating a shift from Eurocentric, agrarian themes toward global, intersectional, and methodological complexity, encompassing environmental protection, gender roles, and digital tools. Finally, RQ4, addressed in Table 2, confirms these shifts by identifying the most influential literature, which prominently features global, critical, and interdisciplinary perspectives – ranging from land deals and rural migration in the Global South to spatial restructuring and political ecology. The data across all RQs indicate a consistent, coherent, and evolving field that has shifted from national, structuralist paradigms to a transnational, reflexive, and critically engaged historiography, responding dynamically to scholarly and socio-political transformations.

The most recent scholarly contributions to rural history highlight the field’s dynamic engagement with global, intersectional, and underexplored topics, confirming the trends identified across all research questions regarding thematic diversification and methodological innovation. Studies increasingly address rural masculinities under authoritarian regimes,Footnote 26 gendered labour and mobility,Footnote 27 environmental and spatial histories,Footnote 28 and the politics of land use and agrarian reform across historical contexts.Footnote 29 Integrating digital tools like GISand sociometabolic analysisillustrates a methodological broadening, while including non-Western and postcolonial geographies – such as rural China,Footnote 30 Palestine,Footnote 31 and Latin AmericaFootnote 32 – underscores the shift toward global rural historiographies. Scholars also explore rural cinema,Footnote 33 cultural institutions,Footnote 34 memory, conflict, and identity, reinforcing the field’s movement from agrarian economics toward a richer cultural and political analysis. These recent works reflect and expand upon the intellectual trajectory mapped in Figures 4–7, confirming that rural history has evolved into a critically engaged, methodologically diverse, and geographically expansive discipline, aligned with global historiographical trends.

Recent developments in rural historiography have significantly broadened the field’s analytical scope and methodological sophistication, offering robust support for the research findings and effectively addressing the central research questions through diverse thematic and interdisciplinary approaches. Scholarship has increasingly emphasized community agency and plebeian cultureswhile revisiting rural protest and food politics as central to 18th- and 19th-century power dynamics.Footnote 35 Scholars have investigated colonial and postcolonial agrarian landscapes,Footnote 36 ,Footnote 37 gendered labour patterns and family economies,Footnote 38 and the socio-spatial evolution of small rural settlements.Footnote 39 Land reform and property regimes have received renewed critical focus across diverse geographies,Footnote 40 and new works are linking rural governance with ideological shifts in state formation.Footnote 41 Studies on rural migration, electrification, and demography demonstrate the impact of policy, infrastructure, and globalization on rural transformation,Footnote 42 while methodological innovations include visual culture, spatial analysis, and environmental data.Footnote 43 Research on racial solidarities, indigenous struggles, and peasant resistance repositions rural spaces as sites of political contestation and memory.Footnote 44 Then new trends underscore the growing complexity of rural historiography, marked by greater attention to social justice, environmental change, and transnational comparisons.Footnote 45

It is indeed possible that certain more traditional domains of inquiry into the rural past – such as landscape archaeology, medieval settlement studies, agrarian economy, and historical geography –Footnote 46 though deeply embedded in the empirical and methodological foundations of rural scholarship, are less inclined to employ the explicit label of ‘rural history’ as a keyword or descriptor, thereby leading to their partial invisibility or underrepresentation in bibliometric mappings and historiographical syntheses; for instance, research appearing in specialized venues such as Landscape History, Agricultural History Review, or the Journal of the Medieval Settlement Research Group often continues to operate within well-established disciplinary or chronological frameworks that predate the self-conscious emergence of ‘rural history’ as an interdisciplinary field after c. 1990, and thus such studies, while constituting a vital substratum of the rural historiographical tradition, may not be captured within contemporary analytical samples, which tend to privilege works that explicitly signal their alignment with newer, more theoretically or comparatively informed paradigms;Footnote 47 this divergence underscores the complex genealogy of the field, wherein older empiricist or regionally anchored traditions coexist, sometimes uneasily, with the broader interdisciplinary and international orientations that have come to define the modern conception of rural history, suggesting that the apparent absence of these “traditional” strands in recent thematic surveys reflects not a lack of scholarly vitality but rather a semantic and classificatory gap between evolving historiographical vocabularies and the enduring continuities of rural research practice.

Conclusion

The expanding field of rural history is increasingly characterized by its thematic diversification, interdisciplinary integration, and critical engagement with global and comparative frameworks. A notable future trend is likely to be the growing focus on environmental history and rural ecologies, particularly in light of current climate challenges, as scholars increasingly focus on historical patterns of land use, ecological degradation, and the resilience or transformation of rural landscapes.Footnote 48 Similarly, rural gender studies – especially those that interrogate the intersectionality of class, ethnicity, and gender in agrarian contexts – remain underdeveloped outside a few regional case studies and are poised for further exploration, particularly in non-Western or postcolonial settings. The digital humanities and spatial history also present promising methodological avenues, primarily through applying GIS, remote sensing, and archival digitization to reconstruct rural landscapes, settlement patterns, and long-term agricultural change.Footnote 49 However, a persistent gap remains in longitudinal rural demography, particularly concerning micro-level family histories and community structures beyond Western Europe and North America.Footnote 50 Moreover, studies on rural economies often overlook the informal or subsistence sectors, which are crucial for understanding the lived experiences of rural populations historically and today.Footnote 51 Another area ripe for further inquiry is the history of rural governance and policy, especially how rural populations interacted with, resisted, or shaped state power at the local level – this has practical relevance for contemporary rural development frameworks and decentralization strategies.Footnote 52 Practical precedents drawn from historical rural cooperatives, commons management, and peasant self-governance (e.g., Europe, Latin America, and South Asia) provide instructive models for contemporary participatory development and sustainability initiatives.Footnote 53 As rural history evolves, it must engage more deeply with transnational comparisons, postcolonial critiques, and decolonial methodologies, expanding the field’s relevance and analytical capacity beyond traditional rural-urban binaries and national historiographies.

Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, rural history has significantly broadened its scope and methodology, moving far beyond its earlier, narrowly agrarian and Anglocentric orientations toward a more comparative, interdisciplinary, and globally attuned field. This transformation was shaped by several complementary intellectual currents that predated and converged with the launch of Rural History in 1990. Among the most significant antecedents were the Annales school’s longue durée approach to social and environmental structures, the innovations of historical geography, and the international development of historical demography – primarily through the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure and its French counterparts, such as Louis Henry and Michel Vovelle.Footnote 54 These traditions emphasized rural societies’ material, spatial, and demographic dimensions and influenced subsequent comparative studies of family, kinship, and settlement patterns across Europe and beyond. Literary criticism and cultural studies, particularly the ‘rural turn’ exemplified in the work of John Barrell and other cultural historians, further expanded the field by revealing how representations of the countryside intersected with class, gender, and national identity.Footnote 55

Parallel to these developments, the rise of women’s and gender history from the 1970s onward, inspired by scholars like Esther Boserup and Jane Valenze, reframed questions of labour, patriarchy, and agency in the rural economy.Footnote 56 Anthropological perspectives – from Bourdieu, Leach, and Macfarlane, among others – contributed analytical tools for understanding kinship, ritual, and symbolic economies in rural contexts.Footnote 57 This widening of the field was accompanied by a conscious internationalisation: rural history began to flourish not only in Britain and France but also in the United States, Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Japan, China, and later across Africa, Latin America, and Australasia. The deliberate efforts of editors and institutions such as Cambridge University Press to foster transnational and interdisciplinary collaboration further accelerated this expansion, as reflected in the increasingly diverse composition of journal editorial boards.Footnote 58 However, this historiographical reorientation was neither uncontested nor uncontestedly smooth. Many emerging themes – rural gender relations, peasant protest, and cultural representations of the countryside – faced resistance from conservative scholars defending the older ‘plough and cow’ paradigms of agricultural history. The struggles surrounding the establishment of Rural History symbolized these tensions, revealing how academic hierarchies and disciplinary boundaries often resisted the infusion of feminist, anthropological, and social-theoretical perspectives. Nevertheless, through the convergence of these intellectual traditions and the persistence of interdisciplinary advocates, rural history since 1990 has come to embody a dynamic synthesis of economy, society, and culture – an evolving field attentive to both the global diversity and local particularities of the rural past.

This bibliometric study offers a methodologically robust overview of rural history scholarship but presents notable limitations. The exclusive use of Scopus restricts coverage by underrepresenting non-English and regionally significant literature, while relying on a narrow keyword strategy may overlook relevant but differently framed research. Exclusion of non-article formats (e.g., monographs, chapters, and grey literature) further narrows the field’s representation. The dataset reflects a linguistic and geographic bias that favours Anglophone and Western European institutions, thereby limiting epistemological diversity.Footnote 59 Additionally, while analytical tools like VOSviewer and CiteSpace enable detailed network mapping, they favour quantifiable data over interpretive nuance. To advance future research, scholars should adopt multi-database strategies, broaden keyword taxonomies, and incorporate qualitative methods to better reflect the field’s thematic, linguistic, and methodological diversity.

It is possible that the transformations identified within rural history since the late twentieth century – manifest in its widening thematic, geographical, and methodological horizons – are not solely the outcome of shifting intellectual fashions or theoretical realignments, but are equally conditioned by broader institutional and material forces, including the restructuring of academic labour and publishing economies, the commercial strategies of presses and journals seeking to internationalise their readerships, the contraction of university extramural and adult education departments that once sustained a vibrant network of independent and local historians, and the resulting decline in submissions from such ‘amateur’ scholars to long-established venues like the Agricultural History Review, all of which together have recalibrated the balance between professionalized, quantitatively oriented, and globally comparative research and the more regionally grounded empirical traditions that previously defined the field;Footnote 60 and if such patterns are now discernible across the historiography of the rural world, it may well be that they are symptomatic of broader transformations within the historical disciplines at large, in which intellectual innovation has become increasingly intertwined with the pressures and incentives of institutional restructuring, research assessment regimes, and the international marketisation of academic knowledge.

The ongoing transformations within rural history are driven by an intricate interplay between intellectual innovation and structural shifts within the global academic landscape. The expansion of the field beyond its earlier agrarian and national confines reflects not only the influence of broader historiographical movements – such as environmental history, gender studies, and postcolonial theory – but also material changes in the production and circulation of knowledge. The internationalisation of publishing, the consolidation of university research systems, and the growing dominance of interdisciplinary funding frameworks have collectively encouraged scholars to situate rural histories within transnational, ecological, and cultural contexts. Nevertheless, this evolution has also exposed new gaps: rural histories of the Global South remain underrepresented, and comparative research on non-European agrarian systems, indigenous ruralities, and postcolonial land regimes is still limited.Footnote 61 Furthermore, the contraction of local and extramural scholarship has diminished grassroots perspectives that once enriched the field’s empirical base. The intellectual implication of these developments is clear: which rural history must continue to bridge the quantitative reach of global scholarship with the qualitative depth of local experience, integrating new methodologies – digital, environmental, and decolonial – while remaining attentive to the lived specificities of rural worlds across diverse historical and geographical settings.