1. Introduction

Rapid advances in micro-fabrication techniques have aided the miniaturisation and integration of electro-mechanical systems on tiny chips. These micro-electro-mechanical systems find applications in areas ranging from biomedical devices to micro space/aerial vehicles. Currently, these devices rely on low-energy density batteries for their power requirements, which limits their portability and functionality. Micro/meso combustors were initially conceived as potential alternatives to power these devices since the energy density of a typical liquid hydrocarbon is two orders higher in magnitude than standard alkaline/Li-ion batteries (Fernandez-Pello Reference Fernandez-Pello2002; Maruta Reference Maruta2011; Kaisare & Vlachos Reference Kaisare and Vlachos2012). However, micro/meso-scale combustion has found its way into other domains in the form of micro-reactors (that find extensive applications in quantitative chemistry as reported by Zimmermann et al. (Reference Zimmermann, Krippner, Vogel and Müller2002)) and fire safety systems. In this context, ‘micro’ describes combustors with a characteristic length scale smaller than the quenching diameter, while ‘meso’ combustors have a larger length scale that is of the order of the quenching diameter (Ju & Maruta Reference Ju and Maruta2011).

When the combustor size drops to micro or meso scales, the surface area-to-volume ratio increases significantly. As a result, wall heat losses become a critical factor, making the flame susceptible to both thermal and radical quenching. To sustain combustion under these conditions, a widely adopted strategy involves the upstream recirculation of heat from the product gases into the unburnt reactants. This approach preheats the reactants and alters the temperature gradient at the walls, thereby mitigating heat losses and enabling the flame to persist in channels narrower than the classical quenching limit (Lloyd & Weinberg Reference Lloyd and Weinberg1974). Unlike large-scale combustors, where the walls primarily act as a sink for heat and radicals, flame--wall interactions at smaller scales are more complex. In micro and meso combustors, the walls can also contribute energy to the fluid, depending on the Biot and Fourier numbers. This intricate coupling between the flame and the walls can give rise to additional flame regimes that are not observed in large-scale systems. Evans & Kyritsis (Reference Evans and Kyritsis2011) demonstrated that the thermal properties of the walls, especially thermal conductivity, significantly influence the temperature distribution along the walls and the overall flame dynamics in micro and meso combustors. Recent advancements, such as segmented nozzle designs (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Jiaqiang, Chen, Zhang and Ding2024), have significantly improved wall temperature distribution, thereby enhancing the stability and efficiency of micro-scale flames. Furthermore, the incorporation of innovative features like conical rings has been shown to effectively enhance flame stability (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Jiaqiang, Zhao and Zhao2024; Li et al. Reference Li, Jiaqiang, Ding, Cai and Luo2024). The following discussion explores the commonly observed flame behaviours at these small scales, shedding light on the unique dynamics that arise in micro and meso combustors.

Maruta et al. (Reference Maruta, Parc, Oh, Fujimori, Minaev and Fursenko2004, Reference Maruta, Kataoka, Kim, Minaev and Fursenko2005) conducted studies with a cylindrical quartz tube of inner diameter

![]() $2\,\rm mm$

that acts as an optically accessible micro combustor for premixed methane--air flames. The effect of product gas heat recirculation was imposed using two heating plates positioned at the top and bottom of the tube. In addition to the stationary flames (SFs) that establish themselves at a specific section within the channel, various unsteady flame behaviours were also documented. These included a flame exhibiting a series of ignition, propagation, extinction and re-ignition events, referred to as flames with repetitive extinction and ignition (FREI), as well as a pulsating flame and a flame displaying traits of both pulsation and FREI. Similar observations were reported by Fan et al. (Reference Fan, Minaev, Sereshchenko, Fursenko, Kumar, Liu and Maruta2009) in premixed methane--air flames inside micro-scale rectangular quartz channels of different cross-sections. Ju & Xu (Reference Ju and Xu2005) conducted both theoretical and experimental studies on the propagation and extinction of flames at meso scales. Their findings indicate that a flame within a meso-scale channel could propagate at velocities exceeding that of an adiabatic flame, contingent upon the thermal characteristics and heat capacity of the channel walls. Moreover, in addition to heat recirculation from the product gases, streamwise heat conduction along the walls from the flame can also elevate the temperature of the reactant mixture upstream of the flame front, as noted by Kessler & Short (Reference Kessler and Short2008). This upstream heating has a direct impact on the flame speed, further illustrating the complex interplay between thermal processes and flame dynamics in meso-scale systems.

$2\,\rm mm$

that acts as an optically accessible micro combustor for premixed methane--air flames. The effect of product gas heat recirculation was imposed using two heating plates positioned at the top and bottom of the tube. In addition to the stationary flames (SFs) that establish themselves at a specific section within the channel, various unsteady flame behaviours were also documented. These included a flame exhibiting a series of ignition, propagation, extinction and re-ignition events, referred to as flames with repetitive extinction and ignition (FREI), as well as a pulsating flame and a flame displaying traits of both pulsation and FREI. Similar observations were reported by Fan et al. (Reference Fan, Minaev, Sereshchenko, Fursenko, Kumar, Liu and Maruta2009) in premixed methane--air flames inside micro-scale rectangular quartz channels of different cross-sections. Ju & Xu (Reference Ju and Xu2005) conducted both theoretical and experimental studies on the propagation and extinction of flames at meso scales. Their findings indicate that a flame within a meso-scale channel could propagate at velocities exceeding that of an adiabatic flame, contingent upon the thermal characteristics and heat capacity of the channel walls. Moreover, in addition to heat recirculation from the product gases, streamwise heat conduction along the walls from the flame can also elevate the temperature of the reactant mixture upstream of the flame front, as noted by Kessler & Short (Reference Kessler and Short2008). This upstream heating has a direct impact on the flame speed, further illustrating the complex interplay between thermal processes and flame dynamics in meso-scale systems.

Jackson et al. (Reference Jackson, Buckmaster, Lu, Kyritsis and Massa2007) compared the problem of flame propagation/stabilisation in narrow ducts to that of an edge flame and proposed a model that captured the transition between steady and unsteady flame solutions. The model only had thermal considerations and ignored hydrodynamic contributions by directly imposing a Poiseuille velocity profile inside the duct. This treatment was further emphasised by Bieri et al. (Reference Bieri, Kurdyumov and Matalon2011) and Evans & Kyritsis (Reference Evans and Kyritsis2011). Nonetheless, it was observed that the frequency of flame oscillations in unsteady flames aligned with the Strouhal number associated with the instability of the jet emerging from the micro/meso channels (St

![]() $\sim$

0.4; Richecoeur & Kyritsis Reference Richecoeur and Kyritsis2005), emphasising the role of hydrodynamics in dictating the quantitative flame dynamics. Flame--wall interactions in unsteady flame regimes was extensively studied by Evans & Kyritsis (Reference Evans and Kyritsis2009, Reference Evans and Kyritsis2011). Their work showed that a thin wall serves a dual purpose: acting as a heat sink following ignition, resulting in flame extinction due to rapid heat losses, as well as enabling re-ignition since the wall temperature rises quickly (due to flame–wall interaction) due to the associated low thermal inertia. Consequently, this leads to high-frequency extinction and re-ignition events (FREI).

$\sim$

0.4; Richecoeur & Kyritsis Reference Richecoeur and Kyritsis2005), emphasising the role of hydrodynamics in dictating the quantitative flame dynamics. Flame--wall interactions in unsteady flame regimes was extensively studied by Evans & Kyritsis (Reference Evans and Kyritsis2009, Reference Evans and Kyritsis2011). Their work showed that a thin wall serves a dual purpose: acting as a heat sink following ignition, resulting in flame extinction due to rapid heat losses, as well as enabling re-ignition since the wall temperature rises quickly (due to flame–wall interaction) due to the associated low thermal inertia. Consequently, this leads to high-frequency extinction and re-ignition events (FREI).

Studies by Richecoeur & Kyritsis (Reference Richecoeur and Kyritsis2005) and David P (Reference David2012) have also documented acoustic emissions from flames in the FREI regime. Their research indicates that these acoustic signals correspond to gas expansion events (pressure bursts) occurring during the ignition phase of unsteady flames. The associated frequency spectrum was found to span a wide range, including the natural harmonic modes of the combustor. However, the amplitude of these pressure fluctuations decays to quiescent levels as the flame propagates upstream following ignition. David (Reference David2012) emphasised that the level of acoustic emissions depends significantly on the specific experimental set-up. Their studies demonstrated that sound generation– or its absence– is heavily influenced by the thermal conductivity of the combustor’s wall material; higher conductivity amplifies sound emissions.

Recent studies by Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Cai, Li, Zhou and Gao2024) and Cai et al. (Reference Cai, Tang, Zhao, Zhou and Huang2020) also report acoustic emissions in oscillating flame regimes. These flames exhibited fluctuations in the flame front and were localised to a region inside the combustor without upstream propagation (unlike FREI). The observed pressure fluctuations were found to correspond to the oscillations of the flame front. However, the frequencies of these fluctuations were significantly off from the natural harmonic of the combustor tube. Similarly, studies by Prakash et al. (Reference Prakash, Armijo, Masel and Shannon2007a ,Reference Prakash, Armijo, Masel and Shannonb ) on the dynamics of non-premixed methane–oxygen flames in micro-scale channels demonstrated acoustic emissions during the transient phase preceding the establishment of a steady-state flame. In this phase, an edge flame with an elongated tail was observed to anchor at the inlet of the mixing layer between the methane–oxygen streams. Additionally, an unsteady flame undergoing repetitive cycles of ignition and extinction was present. The corresponding acoustic signals exhibited two dominant peaks: one associated with the repetition frequency of the unsteady flame and the other near the natural harmonic of the combustor tube. The authors hypothesised that the second peak is thermoacoustic in nature and attributed it to the steady flame anchored at the mixing layer. However, the acoustic emission ceased to exist beyond the transient phase. Interestingly, thermoacoustic coupling, which is widely observed in large-scale combustors (Schuller et al. Reference Schuller, Poinsot and Candel2020; Mohan & Mariappan Reference Mohan and Mariappan2023) and flames propagating inside channels (Castela et al. Reference Castela, Correa, Alam, Jason and Lacoste2021; Dubey et al. Reference Dubey, Koyama, Hashimoto and Fujita2021; Flores-Montoya et al. Reference Flores-Montoya, Muntean, Pozo-Estivariz and Martínez-Ruiz2023), has not been reported in periodically repeating unsteady flame regimes within micro/meso-scale combustors. This phenomenon will be discussed further in the current work, wherein we report a novel periodically repeating unsteady flame regime exhibiting thermoacoustic coupling while traversing to the upstream end of the tube.

Studies have also explored the micro/meso channel flame dynamics under different wall temperature profiles (all the investigated temperature profiles are monotonic along the combustor axis). Kang et al. (Reference Kang, Gollan, Jacobs and Veeraragavan2017) performed numerical investigations on methane–air flames in microchannels, revealing that flame propagation speed depends not only on the chemical heat release rate but also on the rate of heat exchange between the flame and the channel walls. These interactions collectively result in quantitative variations in flame regime characteristics under different wall temperature profiles. Similarly, Ratna Kishore et al. (Reference Ratna Kishore, Minaev, Akram and Kumar2017) demonstrated that reducing the axial wall temperature gradients shifts the ignition location toward zones with lower wall temperatures. Numerical studies by Wang and collaborators (Wang & Fan Reference Wang and Fan2021a ,Reference Wang and Fanb , Reference Wang and Fan2022, Reference Wang and Fan2023; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wang and Fan2025) have highlighted the significant impact of wall temperature profiles on micro-scale flame dynamics. Their research reveals a variety of complex phenomena, including the coexistence of upstream normal and downstream weak flames, FREI exhibiting multiple bifurcations and other intricate flame behaviours driven by incomplete combustion and residual species. Notably, variations in wall temperature gradients and profiles were shown to play a pivotal role in influencing flame stability, flame structure and reaction pathways. These findings underscore that changes in wall temperature distributions are critical for controlling and predicting flame behaviour in micro- and meso-scale combustion systems.

In practical meso-scale combustors such as swiss-roll burners, where combustion is stabilised at the centre, hot product gases follow a rectangular outward spiral path while reactants travel along an inward rectangular spiral path to reach the reaction-stabilised centre of the combustor. The wall temperature profile is expected to decrease monotonically as we move radially outward from the reaction zone. However, as the flow decelerates at the corners of these rectangular spiral paths, regions with minor spikes in the wall temperature profile are anticipated. The existing literature provides compelling evidence to show that such spikes in the wall temperature profile can significantly influence flame–wall interactions, leading to both quantitative and qualitative changes in flame dynamics. A simplified depiction of wall temperature spikes causing changes in the flame behaviour is discussed in the current study.

The objective of the current study is twofold. The first part investigates the dynamics of unsteady premixed methane–air flames in meso-scale channels, imposed with a monotonically decaying temperature profile along the combustor axis (in the upstream direction). Alongside the well-documented FREI regime, we report the observation of a periodically repeating unsteady novel flame regime that exhibits thermoacoustic coupling. Additionally, we explore the changes in the dynamics of these unsteady flame regimes following the imposition of a bimodal heating profile. This bimodal profile represents a simplified one-dimensional depiction of the local temperature spike imposed over a monotonically decaying wall temperature profile along the combustor axis.

2. Experimental set-up

2.1. Meso-scale combustor facility

A cylindrical quartz channel of

![]() $5\,\rm mm$

inner diameter (

$5\,\rm mm$

inner diameter (

![]() ${d}_{i}$

) and

${d}_{i}$

) and

![]() $7\,\rm mm$

outer diameter (

$7\,\rm mm$

outer diameter (

![]() $d_{o}$

) is used as an optically accessible meso-scale combustor (length:

$d_{o}$

) is used as an optically accessible meso-scale combustor (length:

![]() $380\,\rm mm$

). The channel is heated using two external heaters: a primary heater and a secondary heater, as depicted in figure 1(a). The primary heating unit consists of two heating torches, each fitted with

$380\,\rm mm$

). The channel is heated using two external heaters: a primary heater and a secondary heater, as depicted in figure 1(a). The primary heating unit consists of two heating torches, each fitted with

![]() $12\,\rm mm$

cylindrical nozzles at their tips. These torches are oriented at an angle of

$12\,\rm mm$

cylindrical nozzles at their tips. These torches are oriented at an angle of

![]() $35^{\circ}$

from the central plane (as shown in figure 1a, right) such that the combustor tube passes through the stagnation plane of the jet flames produced by the torches. The tips of the torches are positioned

$35^{\circ}$

from the central plane (as shown in figure 1a, right) such that the combustor tube passes through the stagnation plane of the jet flames produced by the torches. The tips of the torches are positioned

![]() $20\,\rm mm$

below the axis of the combustor tube. The secondary heater is a McKenna flat flame burner, featuring a flat, circular porous surface with a diameter of

$20\,\rm mm$

below the axis of the combustor tube. The secondary heater is a McKenna flat flame burner, featuring a flat, circular porous surface with a diameter of

![]() $60\,\rm mm$

at the top, over which a flat flame is stabilised. It is positioned

$60\,\rm mm$

at the top, over which a flat flame is stabilised. It is positioned

![]() $25\,\rm mm$

below the combustor tube axis. The dual-torch primary heater directs the flame onto a narrow section of the combustor tube, with a width approximately matching the nozzle diameter (

$25\,\rm mm$

below the combustor tube axis. The dual-torch primary heater directs the flame onto a narrow section of the combustor tube, with a width approximately matching the nozzle diameter (

![]() $12\,\rm mm$

). In contrast, the secondary heater heats a broader section of the tube, corresponding to the

$12\,\rm mm$

). In contrast, the secondary heater heats a broader section of the tube, corresponding to the

![]() $60\,\rm mm$

diameter of its porous surface. This distinction is clear in figure 1(b), which plots the inner wall temperature profile along the combustor axis. The figure shows that the primary heating zone (the combustor section directly above the primary heater) is narrower compared with the secondary heating zone (the section above the secondary heater). Additionally, the peak temperature in the primary heating zone (

$60\,\rm mm$

diameter of its porous surface. This distinction is clear in figure 1(b), which plots the inner wall temperature profile along the combustor axis. The figure shows that the primary heating zone (the combustor section directly above the primary heater) is narrower compared with the secondary heating zone (the section above the secondary heater). Additionally, the peak temperature in the primary heating zone (

![]() ${\sim }1130\,\rm K$

) is higher than that in the secondary heating zone (

${\sim }1130\,\rm K$

) is higher than that in the secondary heating zone (

![]() ${\sim}1025\,\rm K$

) and is a result of positioning the primary heater closer to the combustor axis than the secondary heater. In combination, the primary and secondary heaters impose a bimodal wall heating profile over the combustor walls. The distance between the centres of the heaters, characterised by

${\sim}1025\,\rm K$

) and is a result of positioning the primary heater closer to the combustor axis than the secondary heater. In combination, the primary and secondary heaters impose a bimodal wall heating profile over the combustor walls. The distance between the centres of the heaters, characterised by

![]() $d$

(figure 1a), is varied to obtain different bimodal wall heating profiles. The secondary heater was intentionally positioned farther from the combustor tube axis (than the primary heater) to ensure that it only preheats the premixed reactant mixture without triggering an auto-ignition event. In contrast, the primary heater was specifically designed to induce auto-ignition of the reactant mixture.

$d$

(figure 1a), is varied to obtain different bimodal wall heating profiles. The secondary heater was intentionally positioned farther from the combustor tube axis (than the primary heater) to ensure that it only preheats the premixed reactant mixture without triggering an auto-ignition event. In contrast, the primary heater was specifically designed to induce auto-ignition of the reactant mixture.

Figure 1. (a) Experimental set-up. (b) Inner wall temperature profiles at different separation distances (

![]() $d/{d}_{i}$

). The regions highlighted in brown and yellow represent the primary and secondary heating zones, respectively, for

$d/{d}_{i}$

). The regions highlighted in brown and yellow represent the primary and secondary heating zones, respectively, for

![]() $d/{d}_{i}=18$

.

$d/{d}_{i}=18$

.

Figure 1(b) depicts the spatial profile of the wall temperature measured along the inner walls of the combustor tube, using a

![]() $1\,\rm mm$

K-type thermocouple. It is to be noted that since the combustor tube is heated from below, the inner wall temperature is not uniform across the combustor cross-section. The lower periphery, in closer proximity to the heaters, has a higher wall temperature compared with the upper periphery. This disparity was most pronounced in the primary heating zone, reaching approximately

$1\,\rm mm$

K-type thermocouple. It is to be noted that since the combustor tube is heated from below, the inner wall temperature is not uniform across the combustor cross-section. The lower periphery, in closer proximity to the heaters, has a higher wall temperature compared with the upper periphery. This disparity was most pronounced in the primary heating zone, reaching approximately

![]() $2\,\%$

of the measured temperature. The temperature profiles depicted in figure 1(b) represent inner wall temperature measured along the lower periphery of the combustor in the axial direction. A plot comparing the inner wall temperatures along the lower and upper peripheries is provided in section S1 of the supplementary material. The profiles are estimated from three sets of experimental measurements and correspond to quiescent conditions inside the combustor.

$2\,\%$

of the measured temperature. The temperature profiles depicted in figure 1(b) represent inner wall temperature measured along the lower periphery of the combustor in the axial direction. A plot comparing the inner wall temperatures along the lower and upper peripheries is provided in section S1 of the supplementary material. The profiles are estimated from three sets of experimental measurements and correspond to quiescent conditions inside the combustor.

Methane and air regulated through two precise mass flow controllers (Bronkhorst flexi-flow compact with the range of 0–1.6 SLPM for

![]() $\rm CH_4$

and 0–2 SLPM for air) are directed into a mixing chamber, where the streams mix into each other to create a homogeneous mixture, which is then subsequently fed into the quartz combustor tube at its upstream end. The flow rates of liquefied petroleum gas and air into the primary and secondary heaters were controlled using precise pressure regulators and mass flow controllers (Alicat Scientific MCR-500SLPM), respectively. In the discussions that follow, the

$\rm CH_4$

and 0–2 SLPM for air) are directed into a mixing chamber, where the streams mix into each other to create a homogeneous mixture, which is then subsequently fed into the quartz combustor tube at its upstream end. The flow rates of liquefied petroleum gas and air into the primary and secondary heaters were controlled using precise pressure regulators and mass flow controllers (Alicat Scientific MCR-500SLPM), respectively. In the discussions that follow, the

![]() $x$

axis is oriented along the combustor axis, extending along the downstream direction. The origin (

$x$

axis is oriented along the combustor axis, extending along the downstream direction. The origin (

![]() $x=0\,\rm mm$

) is set at the upstream end of the tube. The quartz tube connects to the upstream mixing chamber via a

$x=0\,\rm mm$

) is set at the upstream end of the tube. The quartz tube connects to the upstream mixing chamber via a

![]() $1.5$

mm tubular constriction followed by a flashback arrestor. The

$1.5$

mm tubular constriction followed by a flashback arrestor. The

![]() $1.5\,\rm mm$

tube houses a

$1.5\,\rm mm$

tube houses a

![]() $100\,\unicode{x03BC}\rm m$

wire mesh upstream of

$100\,\unicode{x03BC}\rm m$

wire mesh upstream of

![]() $x=0\,\rm mm$

.

$x=0\,\rm mm$

.

The current study was performed at three different equivalence ratios (

![]() $\Phi$

):

$\Phi$

):

![]() $0.8$

,

$0.8$

,

![]() $1.0$

and

$1.0$

and

![]() $1.2$

. The mixture velocity (

$1.2$

. The mixture velocity (

![]() $\bar {u}$

) was varied between

$\bar {u}$

) was varied between

![]() $0.1$

and

$0.1$

and

![]() $0.3\,\rm m\,s^-{^1}$

in increments of

$0.3\,\rm m\,s^-{^1}$

in increments of

![]() $0.05\,\rm m\,s^-{^1}$

, yielding upstream Reynolds numbers between

$0.05\,\rm m\,s^-{^1}$

, yielding upstream Reynolds numbers between

![]() $32$

and

$32$

and

![]() $96$

in increments of

$96$

in increments of

![]() $16$

. The experiments were conducted with four different wall heating conditions: a baseline case, wherein only the primary heater was used (no flat flame burner), and three other cases, wherein the distance between the centres of the dual torch and the flat flame burner (

$16$

. The experiments were conducted with four different wall heating conditions: a baseline case, wherein only the primary heater was used (no flat flame burner), and three other cases, wherein the distance between the centres of the dual torch and the flat flame burner (

![]() $d$

) was varied between

$d$

) was varied between

![]() $75\,\rm mm$

to

$75\,\rm mm$

to

![]() $105\,\rm mm$

, in increments of

$105\,\rm mm$

, in increments of

![]() $15\,\rm mm$

, which corresponds to

$15\,\rm mm$

, which corresponds to

![]() $d/d_{i}$

of

$d/d_{i}$

of

![]() $15$

,

$15$

,

![]() $18$

and

$18$

and

![]() $21$

. The axial temperature profile corresponding to these cases is plotted in figure 1(b).

$21$

. The axial temperature profile corresponding to these cases is plotted in figure 1(b).

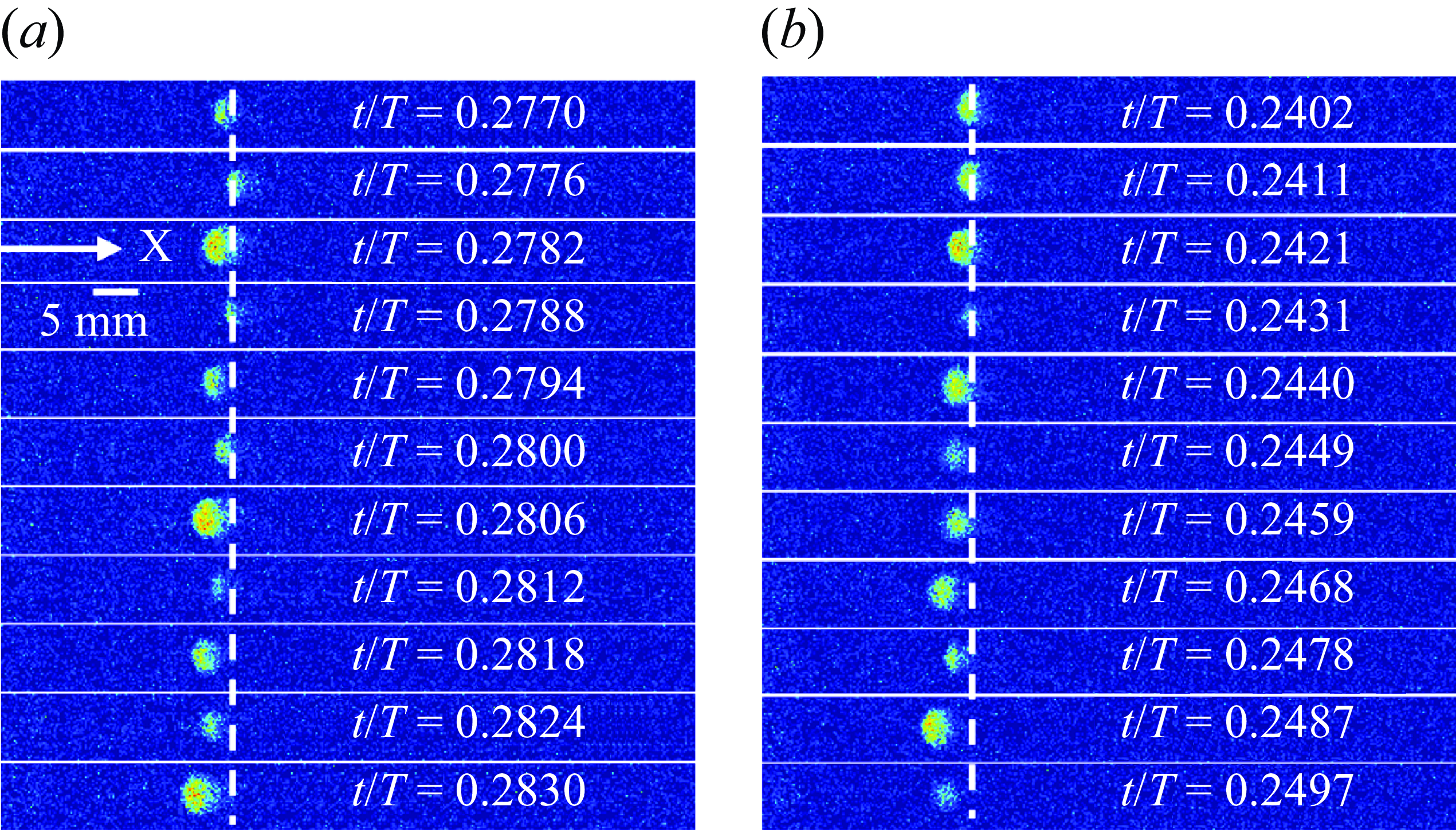

2.2. High-speed flame imaging and data acquisition from PMT and microphone

A Phantom Miro Lab 110 high-speed camera coupled with a

![]() $100\,\rm mm$

Tokina macro-lens was used for high-speed flame imaging. The dynamics were captured at 4000 frames per second (

$100\,\rm mm$

Tokina macro-lens was used for high-speed flame imaging. The dynamics were captured at 4000 frames per second (

![]() $250\,\unicode{x03BC}\rm s$

exposure time) with a spatial resolution of

$250\,\unicode{x03BC}\rm s$

exposure time) with a spatial resolution of

![]() $200\,\unicode{x03BC}\rm m$

per pixel (frame size of 1280 × 120 pixels). The data were used to track the spatial location of the flame. It is to be noted that the initial

$200\,\unicode{x03BC}\rm m$

per pixel (frame size of 1280 × 120 pixels). The data were used to track the spatial location of the flame. It is to be noted that the initial

![]() $65\,\rm mm$

segment of the quartz tube was inaccessible for imaging due to the presence of a steel support that held the

$65\,\rm mm$

segment of the quartz tube was inaccessible for imaging due to the presence of a steel support that held the

![]() $380\,\rm mm$

long quartz combustor tube in the form of a cantilever (figure 1a). The OH* chemiluminescence signal of the flame was captured using a Hamamatsu photomultiplier tube (PMT, H 11526-110-NF). The PMT was positioned at a distance of

$380\,\rm mm$

long quartz combustor tube in the form of a cantilever (figure 1a). The OH* chemiluminescence signal of the flame was captured using a Hamamatsu photomultiplier tube (PMT, H 11526-110-NF). The PMT was positioned at a distance of

![]() $70\,\rm mm$

from the downstream end of the combustor along the tube axis, such that the photocathode is exposed to the flame inside the combustor tube via a Nikon Rayfact (PF10445MF) UV lens and an OH* bandpass filter (

$70\,\rm mm$

from the downstream end of the combustor along the tube axis, such that the photocathode is exposed to the flame inside the combustor tube via a Nikon Rayfact (PF10445MF) UV lens and an OH* bandpass filter (

![]() $\sim 310 \pm 10\,\text {nm}$

); depicted in figure 1(a). The pressure field fluctuation was recorded using a PCB microphone (PCB 130E20), which was placed at a radial distance of

$\sim 310 \pm 10\,\text {nm}$

); depicted in figure 1(a). The pressure field fluctuation was recorded using a PCB microphone (PCB 130E20), which was placed at a radial distance of

![]() $80\,\rm mm$

from the combustor axis at the downstream end of the combustor tube (figure 1a). The data from the PMT and the microphone were acquired using an NI-DAQ (PCI 6251) at 12,000 Hz and was triggered alongside flame imaging via the high-speed camera.

$80\,\rm mm$

from the combustor axis at the downstream end of the combustor tube (figure 1a). The data from the PMT and the microphone were acquired using an NI-DAQ (PCI 6251) at 12,000 Hz and was triggered alongside flame imaging via the high-speed camera.

The flame images from the high-speed camera were processed in ImageJ, where they were subjected to thresholding using the Otsu thresholding technique, an integral feature of ImageJ. Otsu’s thresholding algorithm calculates a single intensity threshold value (

![]() $I_f$

) that separates all the pixels within an image into two categories: foreground and background. This threshold value

$I_f$

) that separates all the pixels within an image into two categories: foreground and background. This threshold value

![]() $(I_f)$

is determined by minimising the variance within each category or maximising the variance between the two. Pixels

$(I_f)$

is determined by minimising the variance within each category or maximising the variance between the two. Pixels

![]() $(i, j)$

with intensities greater than or equal to

$(i, j)$

with intensities greater than or equal to

![]() $I_f$

are set to a binary value of 1, while those with intensities less than

$I_f$

are set to a binary value of 1, while those with intensities less than

![]() $I_f$

are assigned 0. The resulting binary area, comprising pixels with a value of 1, delineates the flame’s boundary. Once the boundary is estimated, the location of the flame (

$I_f$

are assigned 0. The resulting binary area, comprising pixels with a value of 1, delineates the flame’s boundary. Once the boundary is estimated, the location of the flame (

![]() $x_f$

) is tracked by estimating the centroid of the region isolated by the flame boundary. The method has proven to be an effective technique for tracking the position of the flame and has been implemented previously by Vadlamudi et al. (Reference Vadlamudi, Thirumalaikumaran and Basu2021), Pandey et al. (Reference Pandey, Basu, Gautham, Potnis and Chattopadhyay2020), Thirumalaikumaran et al. (Reference Thirumalaikumaran, Vadlamudi and Basu2022) and Vadlamudi et al. (Reference Vadlamudi, Aravind and Basu2023). The position of the flame is tracked spatially with respect to time to obtain the flame propagation speed (

$x_f$

) is tracked by estimating the centroid of the region isolated by the flame boundary. The method has proven to be an effective technique for tracking the position of the flame and has been implemented previously by Vadlamudi et al. (Reference Vadlamudi, Thirumalaikumaran and Basu2021), Pandey et al. (Reference Pandey, Basu, Gautham, Potnis and Chattopadhyay2020), Thirumalaikumaran et al. (Reference Thirumalaikumaran, Vadlamudi and Basu2022) and Vadlamudi et al. (Reference Vadlamudi, Aravind and Basu2023). The position of the flame is tracked spatially with respect to time to obtain the flame propagation speed (

![]() $S_f$

) in the reference frame of zero upstream mixture velocity, compensating for the relative velocity of the incoming mixture (

$S_f$

) in the reference frame of zero upstream mixture velocity, compensating for the relative velocity of the incoming mixture (

![]() $\bar {u}$

) with respect to the upstream traversing flame. Mathematically,

$\bar {u}$

) with respect to the upstream traversing flame. Mathematically,

![]() $S_f$

can be expressed as

$S_f$

can be expressed as

It is to be noted that in the above relation,

![]() $\bar {u}$

is the velocity of the fuel–air mixture measured along the x axis, while

$\bar {u}$

is the velocity of the fuel–air mixture measured along the x axis, while

![]() $S_f$

and

$S_f$

and

![]() ${{\rm d}x_f}/{{\rm d}t}$

are measured along the negative x axis since the flame tends to traverse upstream with respect to the incoming flow.

${{\rm d}x_f}/{{\rm d}t}$

are measured along the negative x axis since the flame tends to traverse upstream with respect to the incoming flow.

The OH* chemiluminescence and microphone signals are processed in MATLAB after filtering it using the Savitzky–Golay filter (Savitzky & Golay Reference Savitzky and Golay1964), which is a low-pass filter based on the local least-square polynomial approximation that smooths the signal without distorting it (Di Stazio et al. Reference Di Stazio, Chauveau, Dayma and Dagaut2016a ,Reference Di Stazio, Chauveau, Dayma and Dagautb ). The data from the PMT and the pressure sensor were used to estimate the time scales associated with the unsteady meso-scale flame regimes. In the discussion presented in the subsequent sections, all the descriptors of unsteady flames (position, flame propagation speeds, OH* chemiluminescence, frequency of repetition, time scales, etc.) are results averaged out over at least ten periodic repetition cycles from three different trials.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Global observations

Premixed methane–air mixture, at

![]() $300\,\rm K$

, enters the quartz combustor tube at

$300\,\rm K$

, enters the quartz combustor tube at

![]() $x=0\,\rm mm$

and travels downstream, continuously gaining heat from the combustor walls and increasing its mean flow temperature (

$x=0\,\rm mm$

and travels downstream, continuously gaining heat from the combustor walls and increasing its mean flow temperature (

![]() $T_m$

). The mixture auto-ignites close to the primary heating zone where the inner wall temperatures are close to

$T_m$

). The mixture auto-ignites close to the primary heating zone where the inner wall temperatures are close to

![]() $1130\,\rm K$

. Upon auto-ignition, the mixture starts to propagate upstream, consuming the incoming reactants. This behaviour is consistently observed across the space of experimental conditions explored in the current work. However, this upstream traversing flame exhibits different dynamics contingent on the operating conditions of Reynolds numbers (

$1130\,\rm K$

. Upon auto-ignition, the mixture starts to propagate upstream, consuming the incoming reactants. This behaviour is consistently observed across the space of experimental conditions explored in the current work. However, this upstream traversing flame exhibits different dynamics contingent on the operating conditions of Reynolds numbers (

![]() $Re$

), equivalence ratios (

$Re$

), equivalence ratios (

![]() $\Phi$

) and imposed wall heating profiles. Two global flame behaviours emerge, steady flames and unsteady flames.

$\Phi$

) and imposed wall heating profiles. Two global flame behaviours emerge, steady flames and unsteady flames.

Stationary stable flames (steady flames) stabilise themselves at a characteristic upstream location (figure 2a) post ignition. However, the unsteady flames demonstrate two distinct patterns: they either extinguish after traversing a characteristic distance (figure 2b) or persist (continue propagating) until extinguished at the upstream meshed constriction of the combustor tube (figure 2d) at

![]() $x=0\,\rm mm$

. These unsteady flame regimes demonstrate periodic recurrence, reigniting after a characteristic time delay following extinction, as the fresh incoming mixture auto-ignites and repeats the flame cycle. Accordingly, three major flame regimes can be identified: stationary flames (SF), flames with repetitive extinction and ignition (FREI) and propagating flames (PF), respectively. In the subsequent sections, the dynamics of the latter-mentioned unsteady flame regimes (FREI and PF) are discussed, initially focusing on the trends observed in the baseline case (wherein only the primary heater is used) and then comparing them with the changes observed due to the introduction of the secondary heater at different separation distances (

$x=0\,\rm mm$

. These unsteady flame regimes demonstrate periodic recurrence, reigniting after a characteristic time delay following extinction, as the fresh incoming mixture auto-ignites and repeats the flame cycle. Accordingly, three major flame regimes can be identified: stationary flames (SF), flames with repetitive extinction and ignition (FREI) and propagating flames (PF), respectively. In the subsequent sections, the dynamics of the latter-mentioned unsteady flame regimes (FREI and PF) are discussed, initially focusing on the trends observed in the baseline case (wherein only the primary heater is used) and then comparing them with the changes observed due to the introduction of the secondary heater at different separation distances (

![]() $d$

). Propagating flames identified in the current study are a novel observation and have not been reported in the literature to the best of the author’s knowledge. Although stationary steady flames are identified in the present work, further experiments are necessary to establish conclusive trends in this regime since the SFs are expected to sustain over a wide range of Reynolds numbers above

$d$

). Propagating flames identified in the current study are a novel observation and have not been reported in the literature to the best of the author’s knowledge. Although stationary steady flames are identified in the present work, further experiments are necessary to establish conclusive trends in this regime since the SFs are expected to sustain over a wide range of Reynolds numbers above

![]() $100$

(Ju & Maruta Reference Ju and Maruta2011), which is beyond the scope of the present work.

$100$

(Ju & Maruta Reference Ju and Maruta2011), which is beyond the scope of the present work.

Figure 2. (a) Stationary flames (SFs). (b) Flames with repetitive extinction and ignition (FREI). (c) Diverging FREI (D-FREI). (d) Propagating flames (PFs). (e) Combined flame (CF). The brown and orange dashed vertical lines indicate the locations of the primary and secondary heaters, respectively. In the figure,

![]() $T$

is the characteristic time period of repetition of the unsteady flames and

$T$

is the characteristic time period of repetition of the unsteady flames and

![]() $t_c$

is the convective time scale associated with the flow. Supplementary movies 1–4 available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.113 illustrate the unsteady flame regimes depicted in figure 2(b–e), respectively. Here, ‘bs’ denotes baseline conditions.

$t_c$

is the convective time scale associated with the flow. Supplementary movies 1–4 available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2025.113 illustrate the unsteady flame regimes depicted in figure 2(b–e), respectively. Here, ‘bs’ denotes baseline conditions.

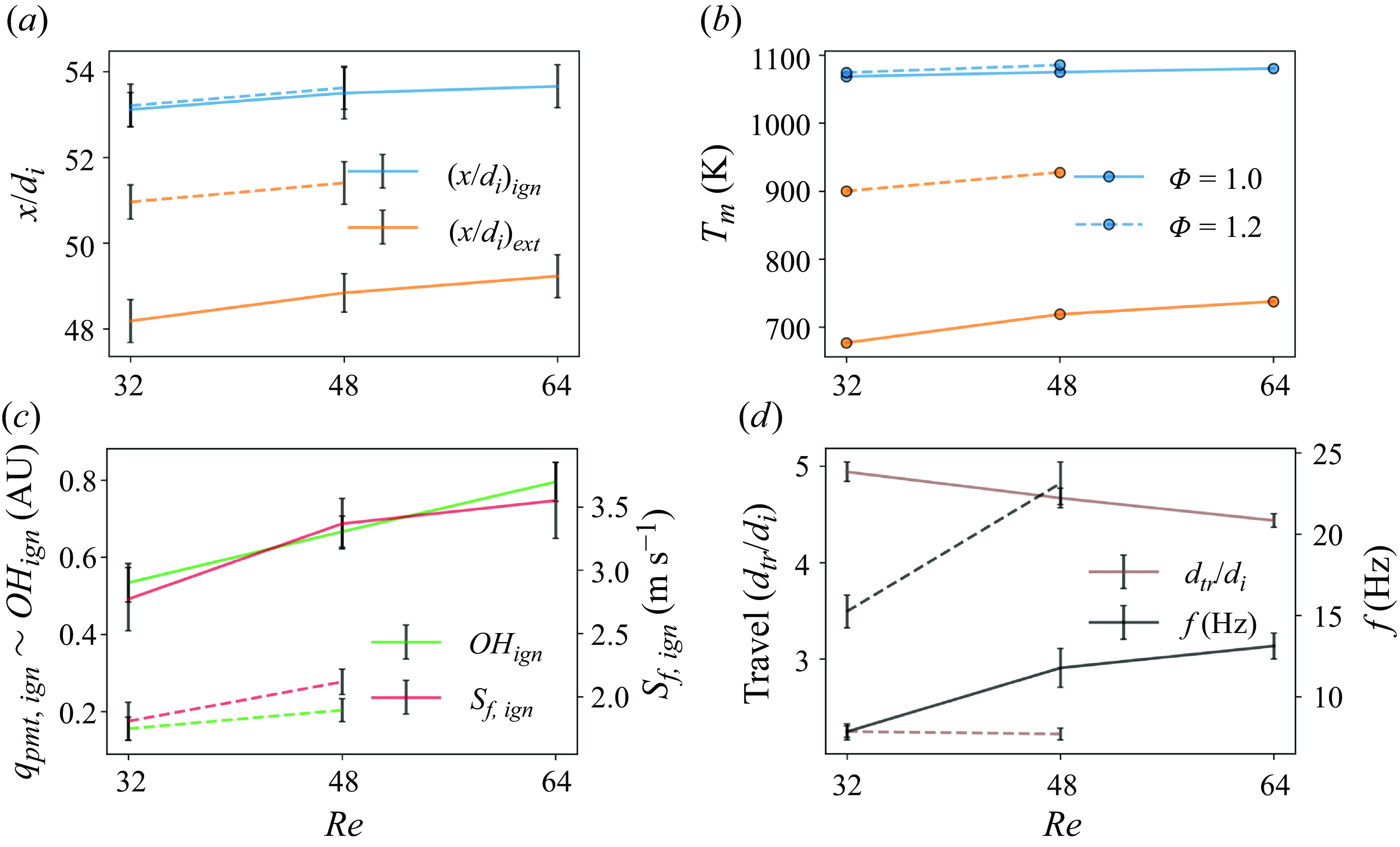

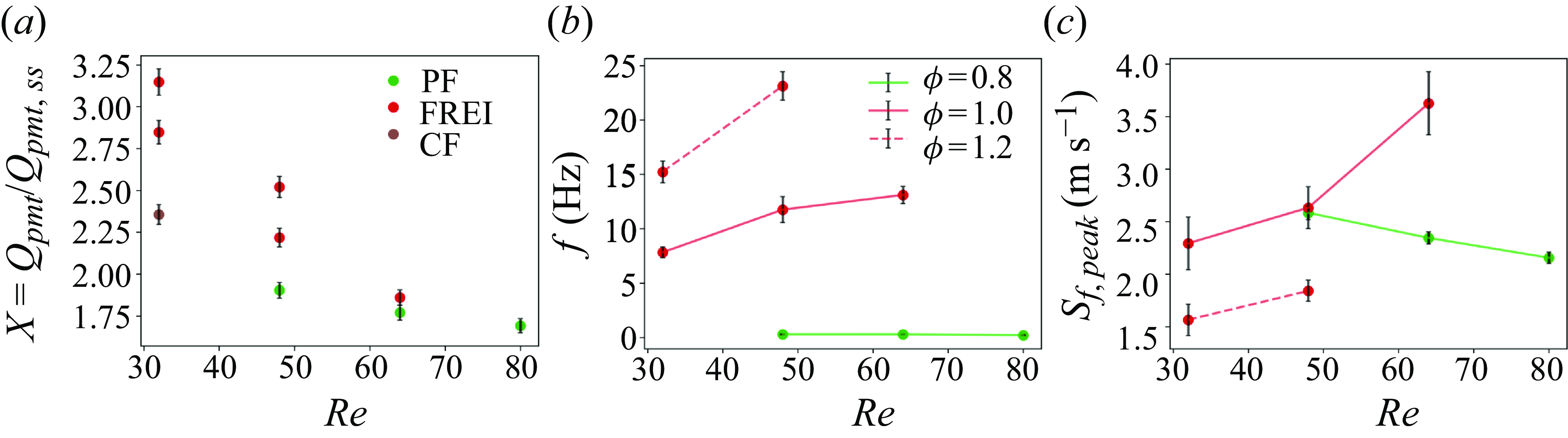

In the baseline configuration, the FREI regime appears at the equivalence ratio of

![]() $1.0$

and

$1.0$

and

![]() $1.2$

, in the low-Reynolds-number regime, bounded by upper limits of

$1.2$

, in the low-Reynolds-number regime, bounded by upper limits of

![]() $64$

and

$64$

and

![]() $48$

, respectively (figure 3a). These flames, upon auto-ignition, propagate upstream and extinguish after a characteristic travel distance. This cycle is observed to repeat itself with a characteristic frequency (

$48$

, respectively (figure 3a). These flames, upon auto-ignition, propagate upstream and extinguish after a characteristic travel distance. This cycle is observed to repeat itself with a characteristic frequency (

![]() $\sim O (10)$

), which increases with rising

$\sim O (10)$

), which increases with rising

![]() $Re$

and

$Re$

and

![]() $\Phi$

. Both the ignition and extinction locations are found to move downstream into regions of higher wall temperatures as the Reynolds number increases. Although the ignition locations are comparable between the equivalence ratios of

$\Phi$

. Both the ignition and extinction locations are found to move downstream into regions of higher wall temperatures as the Reynolds number increases. Although the ignition locations are comparable between the equivalence ratios of

![]() $1.0$

and

$1.0$

and

![]() $1.2$

, the flame tends to extinguish with a shorter flame travel at

$1.2$

, the flame tends to extinguish with a shorter flame travel at

![]() $\Phi =1.2$

.

$\Phi =1.2$

.

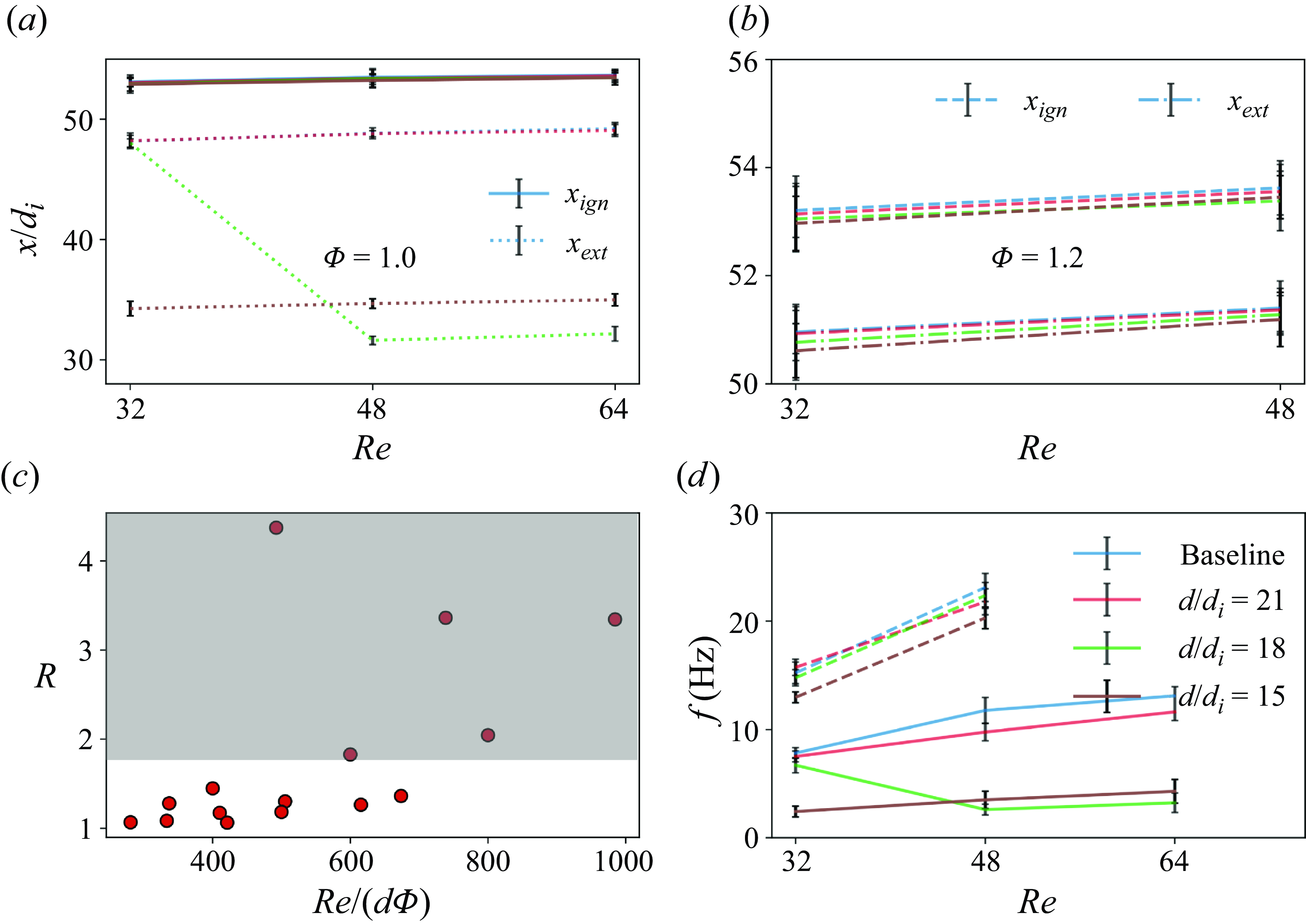

Figure 3. (a) Regime map indicating the different flame regimes observed in the baseline case. (b–d) Regime map corresponding to

![]() $d/d_{i}$

of

$d/d_{i}$

of

![]() $21$

,

$21$

,

![]() $18$

and

$18$

and

![]() $15$

, respectively.

$15$

, respectively.

Introducing the secondary heater was found to qualitatively alter the OH* chemiluminescence and flame speed profiles of the FREI regime in a characteristic range of

![]() $Re$

and

$Re$

and

![]() $\Phi$

. At

$\Phi$

. At

![]() $\Phi =1.0$

, the FREI dynamics changed significantly when the secondary heater was introduced at different separation distances (

$\Phi =1.0$

, the FREI dynamics changed significantly when the secondary heater was introduced at different separation distances (

![]() $d$

). A

$d$

). A

![]() $75$

mm separation between the heaters (

$75$

mm separation between the heaters (

![]() $d/{d}_i\,=\,\rm 15$

) was found to shift the flame’s extinction location upstream, increasing the flame’s travel distance while reducing the FREI repetition frequency. Additionally, an extra peak emerged in the OH* chemiluminescence and flame propagation speed (

$d/{d}_i\,=\,\rm 15$

) was found to shift the flame’s extinction location upstream, increasing the flame’s travel distance while reducing the FREI repetition frequency. Additionally, an extra peak emerged in the OH* chemiluminescence and flame propagation speed (

![]() $S_f$

) profiles. This regime that diverges from the baseline FREI behaviour will be referred to as diverging FREI (D-FREI) in the sections that follow (figure 2c). Similar trends were observed when the separation distance was increased to

$S_f$

) profiles. This regime that diverges from the baseline FREI behaviour will be referred to as diverging FREI (D-FREI) in the sections that follow (figure 2c). Similar trends were observed when the separation distance was increased to

![]() $90\,\rm mm$

(

$90\,\rm mm$

(

![]() $d/{d}_i\,=\,18$

) for

$d/{d}_i\,=\,18$

) for

![]() $Re \geq 48$

, wherein the flame exhibited D-FREI behaviour. However, as the Reynolds number dropped below 48 (at

$Re \geq 48$

, wherein the flame exhibited D-FREI behaviour. However, as the Reynolds number dropped below 48 (at

![]() $d/{d}_i\,=\,18$

), the flame was found to retain the qualitative behaviour of the baseline FREI regime, exhibiting only minor quantitative variations in the FREI descriptors. Dynamics resembling the baseline FREI were also observed when the separation distance was further increased to

$d/{d}_i\,=\,18$

), the flame was found to retain the qualitative behaviour of the baseline FREI regime, exhibiting only minor quantitative variations in the FREI descriptors. Dynamics resembling the baseline FREI were also observed when the separation distance was further increased to

![]() $105\,\rm mm$

(

$105\,\rm mm$

(

![]() $d/d_i\,=\,21$

) across all values of

$d/d_i\,=\,21$

) across all values of

![]() $Re$

. However, unlike stoichiometric conditions, at the equivalence ratio of

$Re$

. However, unlike stoichiometric conditions, at the equivalence ratio of

![]() $1.2$

, the dynamics were found to be weakly dependent on the separation distance (

$1.2$

, the dynamics were found to be weakly dependent on the separation distance (

![]() $d$

), wherein the flame exhibited only minor quantitative variations (with respect to the baseline case) in the FREI descriptors for all values of

$d$

), wherein the flame exhibited only minor quantitative variations (with respect to the baseline case) in the FREI descriptors for all values of

![]() $d/d_{i}$

(across the space of

$d/d_{i}$

(across the space of

![]() $Re$

). These observations with relevant arguments are discussed in detail in §§ 3.3.1 and 3.4.

$Re$

). These observations with relevant arguments are discussed in detail in §§ 3.3.1 and 3.4.

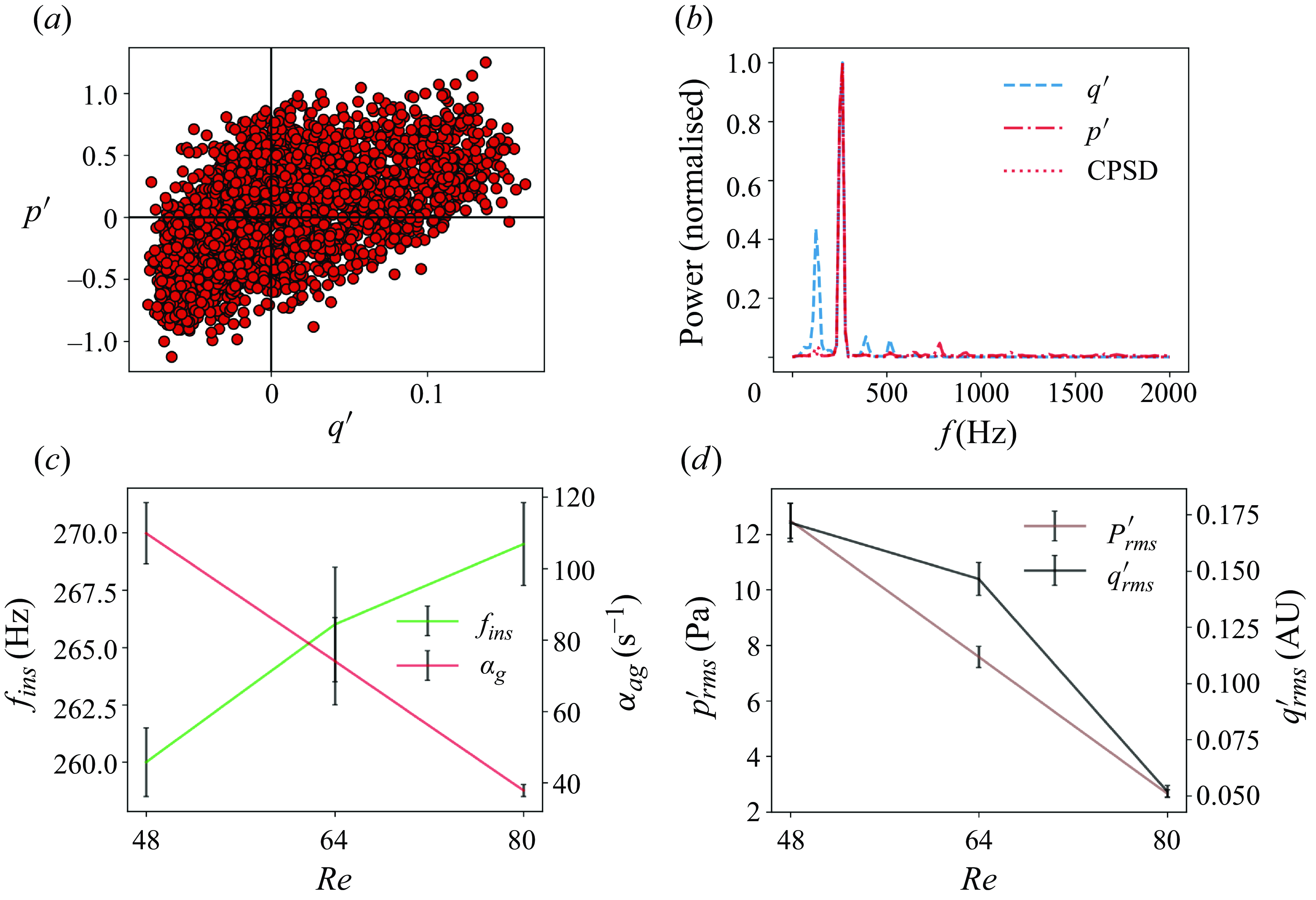

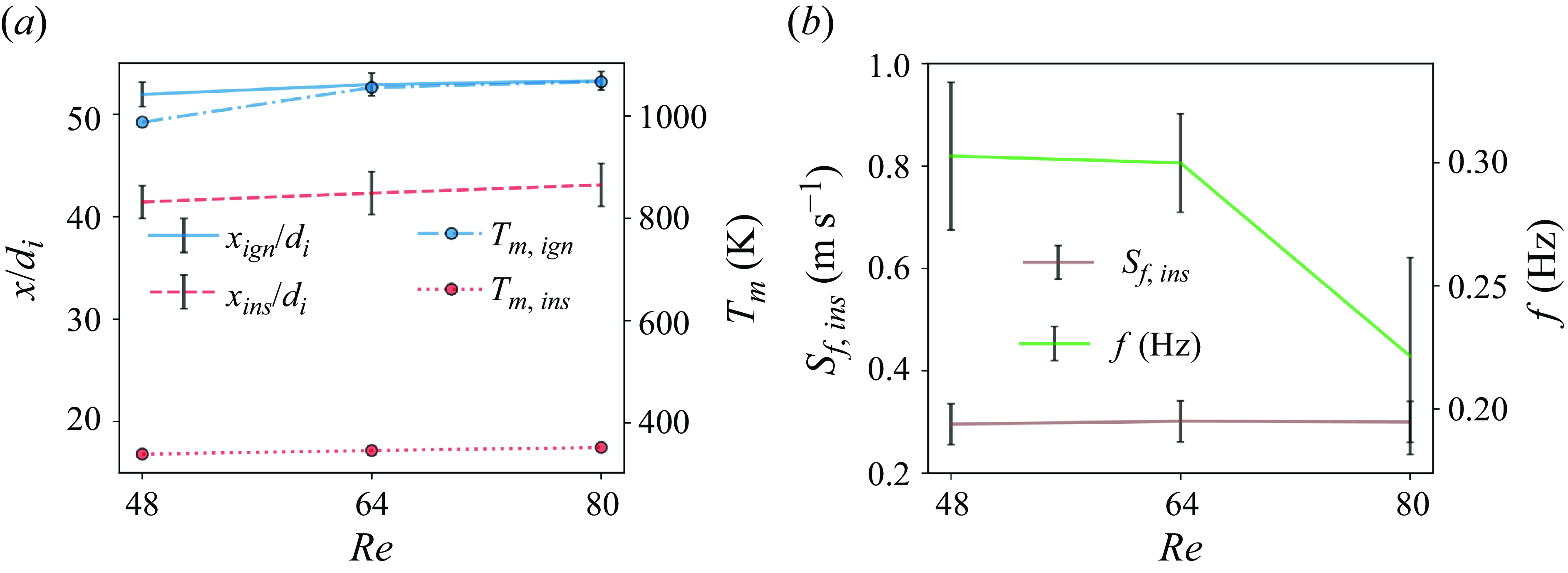

In the baseline case, PFs were observed at the equivalence ratio of

![]() $0.8$

within the Reynolds number range of

$0.8$

within the Reynolds number range of

![]() $48$

to

$48$

to

![]() $80$

. A PF, unlike FREI, continues travelling until it reaches the upstream end of the tube, wherein it is forced to extinguish by a meshed constriction (figure 2d). Their ignition characteristics are similar to that observed in the FREI regime, wherein the ignition location moves downstream into regions of higher wall temperatures as

$80$

. A PF, unlike FREI, continues travelling until it reaches the upstream end of the tube, wherein it is forced to extinguish by a meshed constriction (figure 2d). Their ignition characteristics are similar to that observed in the FREI regime, wherein the ignition location moves downstream into regions of higher wall temperatures as

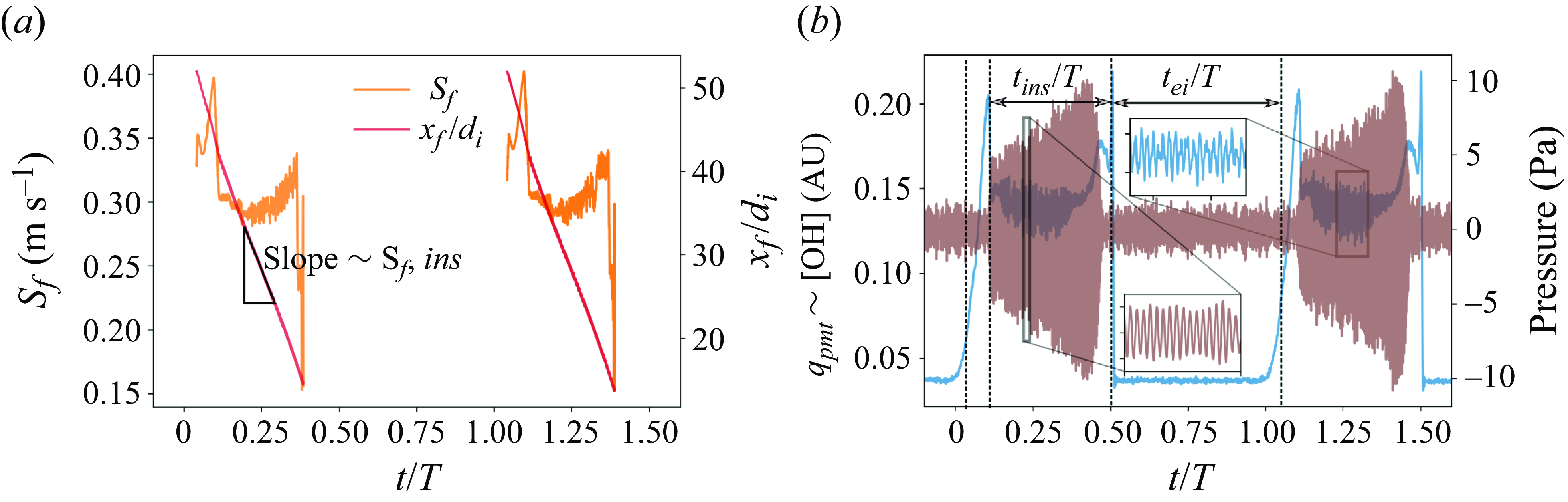

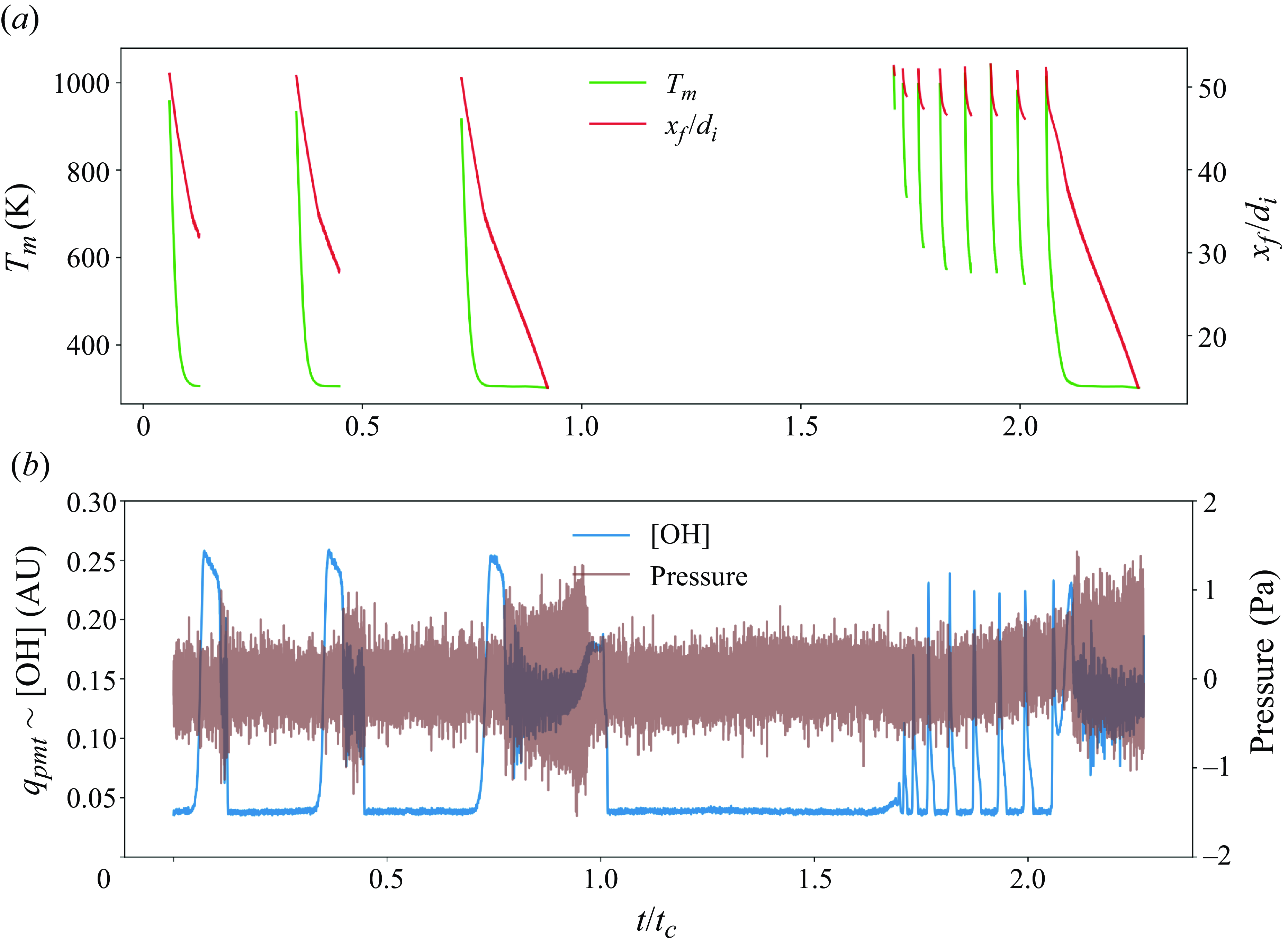

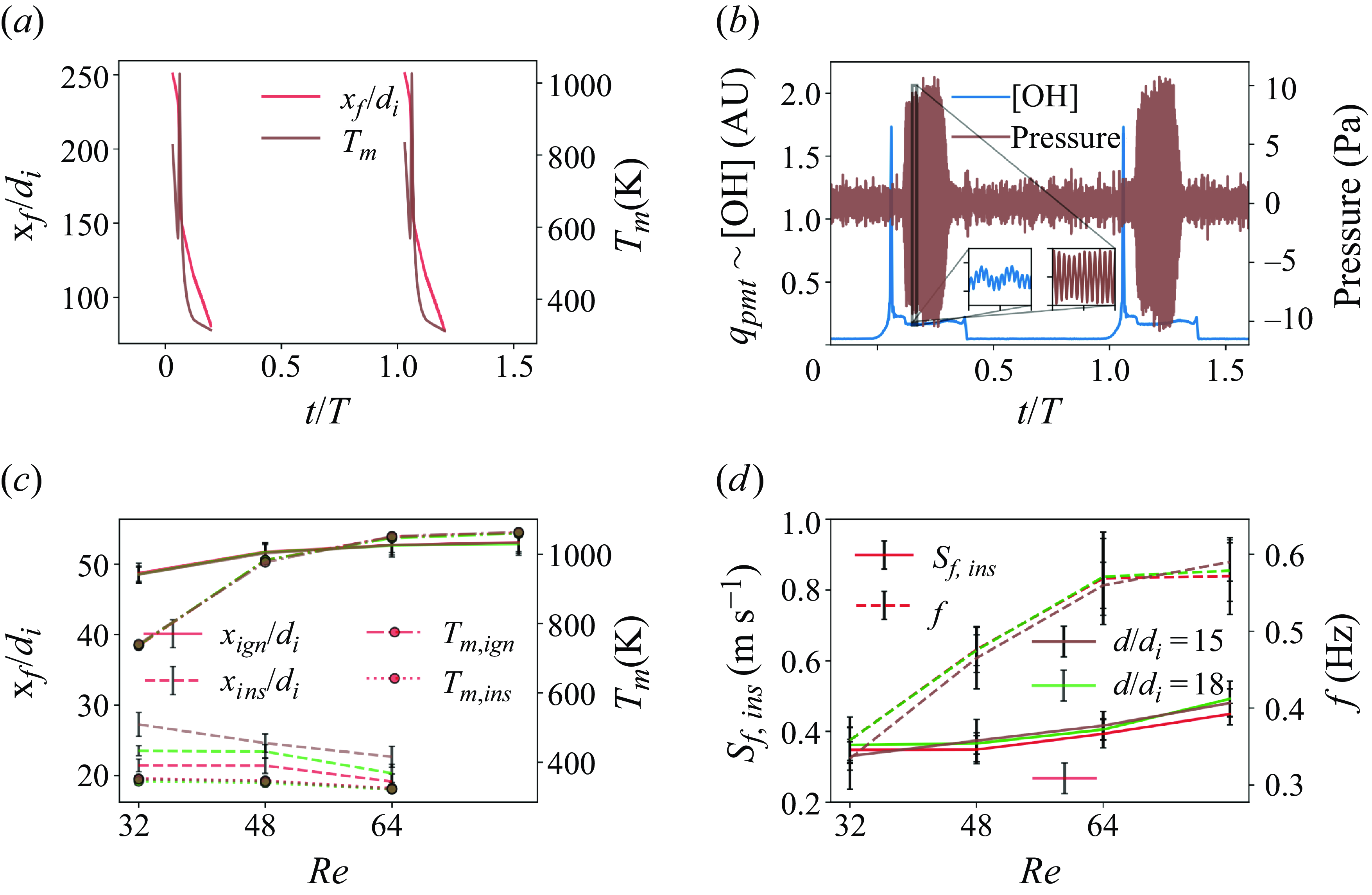

![]() $Re$

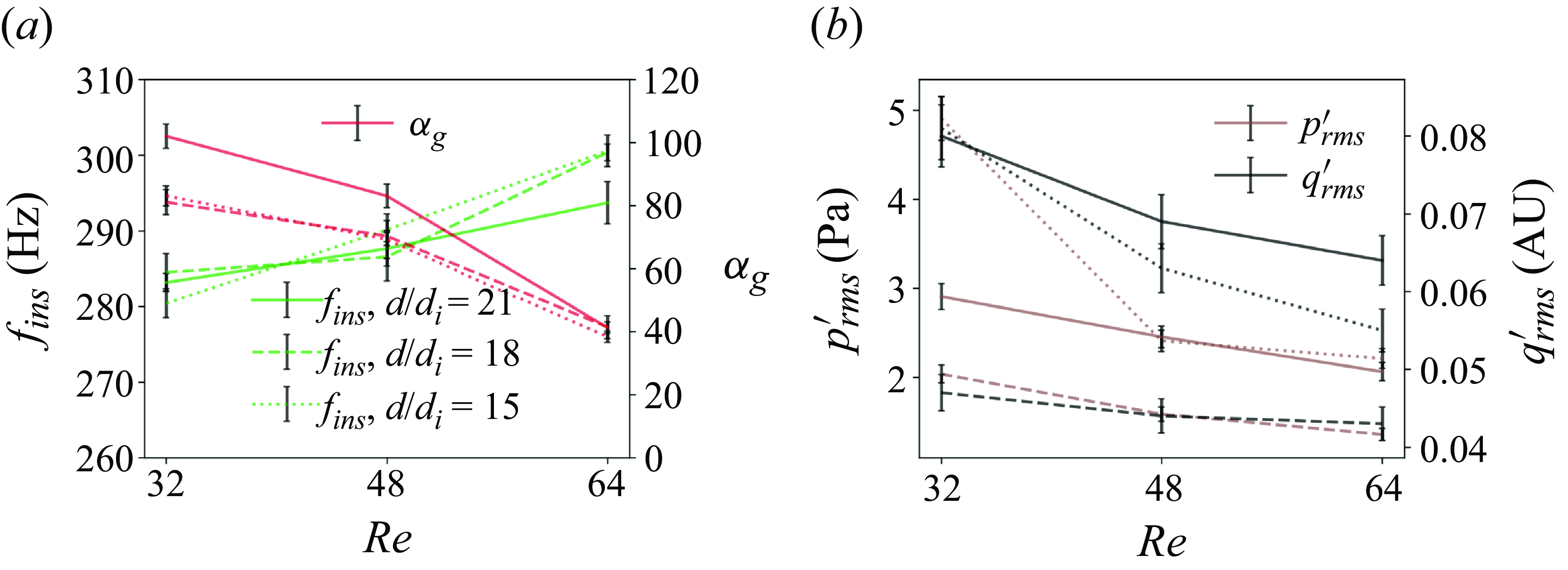

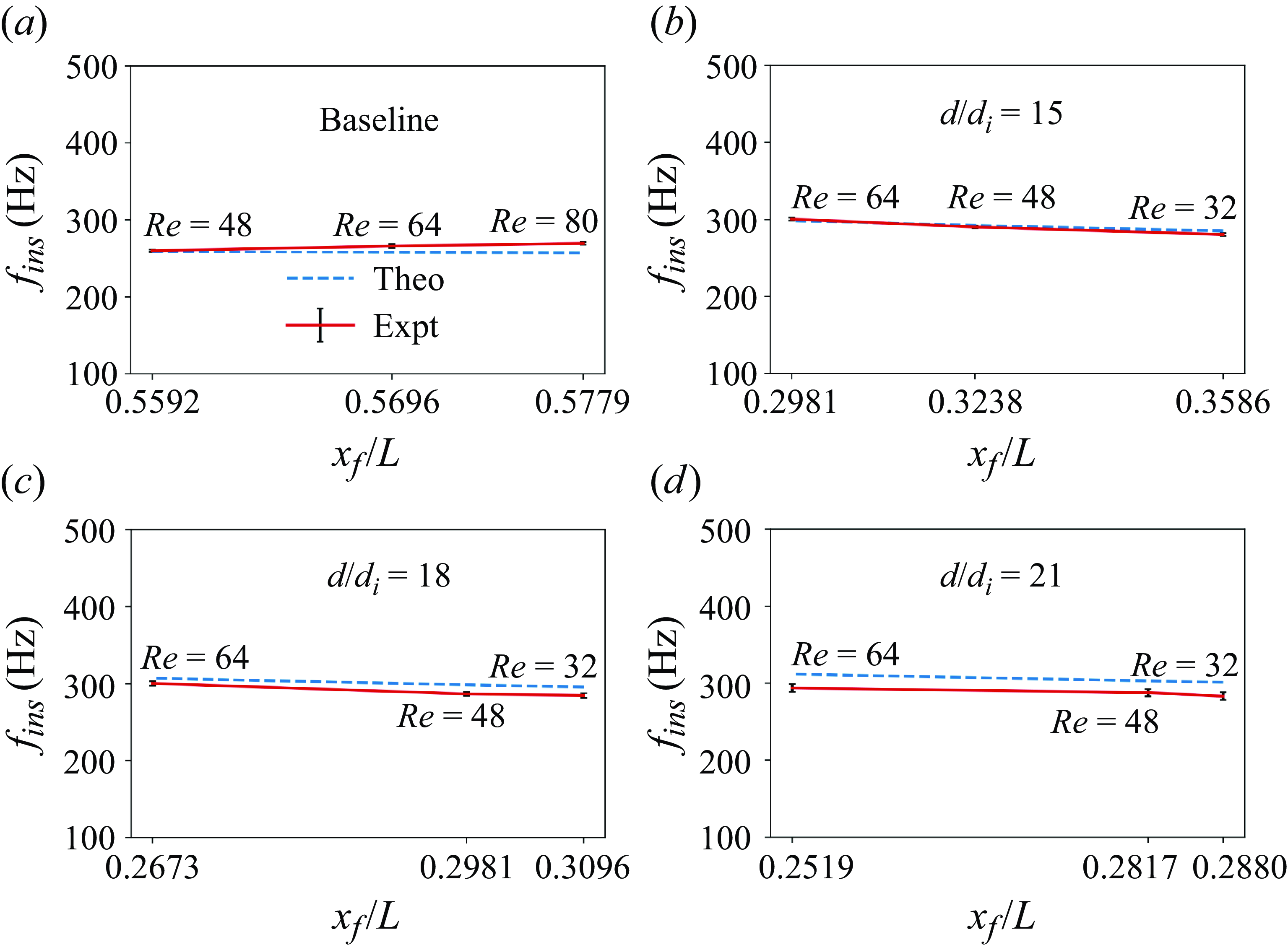

increases. However, unlike FREI, PFs develop instabilities during their propagation phase, that transform into a violent back-and-forth motion of the flame front (figure 9a). These fluctuations are also found to be accompanied by a distinctive acoustic signal. A frequency domain analysis reveals that the fluctuations in the OH* chemiluminescence (heat release rate) and pressure signals are coupled during this phase and that the frequency of oscillation is close to the natural harmonic of the combustor tube. It is interesting to note that once the thermoacoustic coupling is established, the flame propagates upstream at a near-constant propagation velocity (

$Re$

increases. However, unlike FREI, PFs develop instabilities during their propagation phase, that transform into a violent back-and-forth motion of the flame front (figure 9a). These fluctuations are also found to be accompanied by a distinctive acoustic signal. A frequency domain analysis reveals that the fluctuations in the OH* chemiluminescence (heat release rate) and pressure signals are coupled during this phase and that the frequency of oscillation is close to the natural harmonic of the combustor tube. It is interesting to note that once the thermoacoustic coupling is established, the flame propagates upstream at a near-constant propagation velocity (

![]() $S_{f,ins}$

), which tends to increase with an increase in the Reynolds number. In the presence of a secondary heater, the Reynolds number range over which the PFs were observed shifted between

$S_{f,ins}$

), which tends to increase with an increase in the Reynolds number. In the presence of a secondary heater, the Reynolds number range over which the PFs were observed shifted between

![]() $32$

and

$32$

and

![]() $80$

for all values of

$80$

for all values of

![]() $d/d_i$

. The imposition was also found to elevate the peaks of the OH* chemiluminescence and the flame speed signals and quantitatively alter the flame descriptors. These trends are further discussed in § 3.4.

$d/d_i$

. The imposition was also found to elevate the peaks of the OH* chemiluminescence and the flame speed signals and quantitatively alter the flame descriptors. These trends are further discussed in § 3.4.

A combined flame (CF) regime was identified at the equivalence ratio of

![]() $0.8$

and

$0.8$

and

![]() $Re=32$

(figure 2e) in the baseline configuration. The flame exhibited characteristics of both FREI and PFs, wherein a series of finite travel flame cycles (flame extinction after a characteristic travel distance, similar to FREI) was followed by a propagation flame cycle wherein the flame travelled up to the upstream end of the tube (similar to a PF). The number of FREI cycles between consecutive PF cycles was stochastic. This flame regime is synonymous with transitional flame regimes that exist at the regime boundaries of different flame types, as reportedby Ju & Maruta (Reference Ju and Maruta2011). It is to be noted that this regime ceases to exist when the secondary heater is introduced and is only observed in the baseline configuration.

$Re=32$

(figure 2e) in the baseline configuration. The flame exhibited characteristics of both FREI and PFs, wherein a series of finite travel flame cycles (flame extinction after a characteristic travel distance, similar to FREI) was followed by a propagation flame cycle wherein the flame travelled up to the upstream end of the tube (similar to a PF). The number of FREI cycles between consecutive PF cycles was stochastic. This flame regime is synonymous with transitional flame regimes that exist at the regime boundaries of different flame types, as reportedby Ju & Maruta (Reference Ju and Maruta2011). It is to be noted that this regime ceases to exist when the secondary heater is introduced and is only observed in the baseline configuration.

It is important to note that the flame front images shown in figure 2 are not symmetric about the combustor axis. This asymmetry arises due to the peripheral non-uniformity in the wall temperature profiles, which influences the flame shape (Di Stazio et al. Reference Di Stazio, Chauveau, Dayma and Dagaut2016a

). While this may cause minor quantitative changes in the flame characteristics owing to changes in the effective flame speeds, the trends and variations with respect to

![]() $Re$

,

$Re$

,

![]() $\Phi$

and

$\Phi$

and

![]() $d/d_{i}$

, which constitute the primary focus of this study, remain unaltered.

$d/d_{i}$

, which constitute the primary focus of this study, remain unaltered.

Figure 3 presents a regime map that depicts the occurrence of the identified flame regimes as a function of equivalence ratio and Reynolds number at different wall heating conditions. In the sections that follow (

![]() $\S\S\,$

3.3.1 and 3.3.2), the above-mentioned characteristics of FREI and PFs are discussed in detail with relevant scaling/mathematical arguments. However, to delve into such mathematical arguments, we need to first estimate the mean flow temperature (

$\S\S\,$

3.3.1 and 3.3.2), the above-mentioned characteristics of FREI and PFs are discussed in detail with relevant scaling/mathematical arguments. However, to delve into such mathematical arguments, we need to first estimate the mean flow temperature (

![]() $T_m$

) of the reactant mixture prior to ignition, which can act as a parameter to characterise and compare the flame characteristics across the explored parametric space (§ 3.2).

$T_m$

) of the reactant mixture prior to ignition, which can act as a parameter to characterise and compare the flame characteristics across the explored parametric space (§ 3.2).

3.2. Estimation of the mean flow temperature

Mean flow temperature (

![]() $T_{m}$

) is an estimate of the average temperature of the flow across the cross-sectional area (at a given axial distance,

$T_{m}$

) is an estimate of the average temperature of the flow across the cross-sectional area (at a given axial distance,

![]() $x$

) and can be used as a parameter to characterise the ignition–extinction behaviours of the fuel–air mixture. The estimation of

$x$

) and can be used as a parameter to characterise the ignition–extinction behaviours of the fuel–air mixture. The estimation of

![]() $T_m$

presented below is applicable only up to the section where the fluid packet auto-ignites or encounters the unsteady moving flame inside the tube. The following simplifying assumptions were used to evaluate

$T_m$

presented below is applicable only up to the section where the fluid packet auto-ignites or encounters the unsteady moving flame inside the tube. The following simplifying assumptions were used to evaluate

![]() $T_{m}$

.

$T_{m}$

.

Experiments were conducted under steady-state external heating conditions. Due to the proximity of the external heaters to the combustor tube’s lower periphery, a higher inner wall temperature is expected here compared with the upper periphery. However, since the disparities in the inner wall temperatures (

![]() $T_{w,i}(x,r)$

) were measured to be

$T_{w,i}(x,r)$

) were measured to be

![]() ${\leq}2\,\%$

of its measured value, we can approximate the wall temperature profile to have a radial uniformity. This implies that

${\leq}2\,\%$

of its measured value, we can approximate the wall temperature profile to have a radial uniformity. This implies that

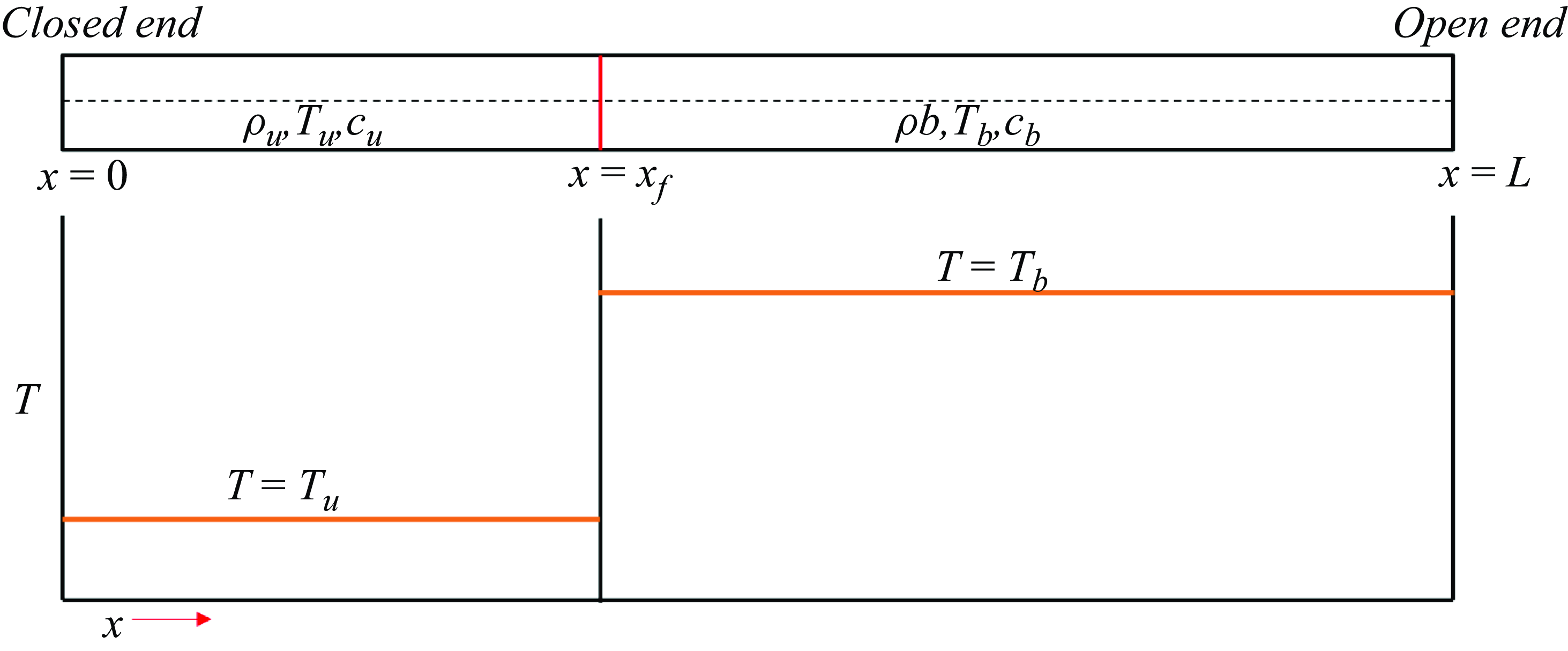

![]() $T_{w,i} (x,r )=T_{w,i} (x )$

in figure 4(a).

$T_{w,i} (x,r )=T_{w,i} (x )$

in figure 4(a).

Figure 4. (a) Schematic depicting heat transfer across the tubular quartz combustor tube. (b) Schematic showing energy transfer across a control volume inside the quartz tube.

As the unsteady regimes of FREI and PFs propagate upstream following ignition, the flame interacts with the combustor walls. However, the wall heating effects resulting from these interactions are negligible compared with the heating provided by the external heaters. Therefore, disregarding the wall heating effects of the unsteady flames on the quartz tube, we can approximate the tube to remain in a steady state. It should be noted that this is a simplifying approximation, and the wall heating effects of unsteady flames can become significant depending on the operating conditions (Ju & Maruta Reference Ju and Maruta2011). However, since our focus is on discussing the qualitative trends in flame characteristics based on the estimated

![]() $T_{m}$

, this approximation can be considered valid within the context of the current study. Consequently, the energy balance equation for the quartz combustor tube simplifies to (figure 4a)

$T_{m}$

, this approximation can be considered valid within the context of the current study. Consequently, the energy balance equation for the quartz combustor tube simplifies to (figure 4a)

It is to be noted that (3.1) holds true for all Reynolds numbers and equivalence ratios of the premixture flow inside the quartz tube since the effect of the internal flow manifests in the form of boundary conditions along the inner walls of the tube. A simple scaling analysis can now be used to deduce the temperature drop across the inner and outer walls of the combustor tube:

The inner wall temperature profile, as measured using the thermocouple, reveals that the axial gradient of the wall temperature is highest near the secondary heating zone wherein the temperature drops from

![]() $1025\,\rm K$

to

$1025\,\rm K$

to

![]() $300\,\rm K$

(

$300\,\rm K$

(

![]() $(\Delta T)_x = 725\,\rm K$

) over an axial distance of approximately

$(\Delta T)_x = 725\,\rm K$

) over an axial distance of approximately

![]() $70\,\rm mm$

(

$70\,\rm mm$

(

![]() $\Delta x = 70\,\rm mm$

). As per the above scaling law, this would imply that

$\Delta x = 70\,\rm mm$

). As per the above scaling law, this would imply that

![]() $(\Delta T)_r \sim 0.15\,\rm K$

, which would correspond to the highest temperature drop in the radial direction (taking

$(\Delta T)_r \sim 0.15\,\rm K$

, which would correspond to the highest temperature drop in the radial direction (taking

![]() $\Delta r \sim (r_{o}-r_{i})$

, where

$\Delta r \sim (r_{o}-r_{i})$

, where

![]() $r_{o}$

and

$r_{o}$

and

![]() $r_{i}$

are the outer and inner wall radii of the combustor tube, respectively). We can thus approximate the inner and outer wall temperatures to be comparable. Section S2 of the supplementary materials presents a finite difference formulation to estimate the outer wall temperature profile from the measured inner wall temperature profile and (3.1). The plots in section S2 clearly depict that the fractional change in temperature between the inner and outer walls of the combustor tube is negligible.

$r_{i}$

are the outer and inner wall radii of the combustor tube, respectively). We can thus approximate the inner and outer wall temperatures to be comparable. Section S2 of the supplementary materials presents a finite difference formulation to estimate the outer wall temperature profile from the measured inner wall temperature profile and (3.1). The plots in section S2 clearly depict that the fractional change in temperature between the inner and outer walls of the combustor tube is negligible.

Combining the above simplifications with the fact that the outer wall temperature is maintained constant by the external heaters (Di Stazio et al. Reference Di Stazio, Chauveau, Dayma and Dagaut2016a

), we can assume that the measured inner wall temperature profile remains temporally invariant and does not change with

![]() $Re$

and

$Re$

and

![]() $\Phi$

. Thus, the inner wall temperature profile in figure 1(b), which is measured under quiescent conditions, can be assumed to hold true across all experimental conditions explored in the current study.

$\Phi$

. Thus, the inner wall temperature profile in figure 1(b), which is measured under quiescent conditions, can be assumed to hold true across all experimental conditions explored in the current study.

We can now estimate the heat transferred from the combustor walls to the fluid moving inside the tube, assuming a temporally invariant inner wall temperature profile. For the Reynolds number range under consideration, the hydrodynamic entrance length is of the order of

![]() $O(10^{\circ})\,\rm mm$

, which is negligible in comparison with the length of the tube (

$O(10^{\circ})\,\rm mm$

, which is negligible in comparison with the length of the tube (

![]() $380\,\rm mm$

). We can thus assume the flow to be fully developed as it passes through the primary and secondary heating zones. Additionally, the Peclet number associated with the flow is of the orderof

$380\,\rm mm$

). We can thus assume the flow to be fully developed as it passes through the primary and secondary heating zones. Additionally, the Peclet number associated with the flow is of the orderof

![]() $O(10)$

, and hence, the effect of axial conduction inside the flow can be neglected in comparison with axial advection effects (Bejan Reference Bejan2013). The energy balance equation for the steady reactant mixture stream moving downstream inside the combustor tube thus reduces to a balance between the radial conduction effects from the combustor walls and axial advection effects associated with the flow:

$O(10)$

, and hence, the effect of axial conduction inside the flow can be neglected in comparison with axial advection effects (Bejan Reference Bejan2013). The energy balance equation for the steady reactant mixture stream moving downstream inside the combustor tube thus reduces to a balance between the radial conduction effects from the combustor walls and axial advection effects associated with the flow:

A simple scaling analysis can be used to show that the Nusselt number will remain constant under these considerations (Bejan Reference Bejan2013). For an elemental control volume of length

![]() $\Delta x$

(where

$\Delta x$

(where

![]() $\Delta x \lt \lt L$

, where, L is the length of the combustor tube) in the flow domain (figure 4b), the wall temperature can be assumed to remain spatially constant across the elemental length of

$\Delta x \lt \lt L$

, where, L is the length of the combustor tube) in the flow domain (figure 4b), the wall temperature can be assumed to remain spatially constant across the elemental length of

![]() $\Delta x$

. Invoking the assumption detailed earlier on the temporal invariance of the inner wall temperature, we can assume the inner wall temperature to remain locally constant across

$\Delta x$

. Invoking the assumption detailed earlier on the temporal invariance of the inner wall temperature, we can assume the inner wall temperature to remain locally constant across

![]() $\Delta x$

; spatially and temporally. This simplification helps in estimating the value of the Nusselt number to 3.66, locally (Bejan Reference Bejan2013).

$\Delta x$

; spatially and temporally. This simplification helps in estimating the value of the Nusselt number to 3.66, locally (Bejan Reference Bejan2013).

The energy balance equation can be further simplified to obtain

where

![]() $q^{\prime\prime}_{w}(x)$

is the wall heat flux at the axial distance of

$q^{\prime\prime}_{w}(x)$

is the wall heat flux at the axial distance of

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $\dot {m}$

is the reactant mass flow rate and

$\dot {m}$

is the reactant mass flow rate and

![]() $H(x)$

is the specific enthalpy of the mixture. Substituting for

$H(x)$

is the specific enthalpy of the mixture. Substituting for

![]() $q^{\prime\prime}_{w}(x)$

as

$q^{\prime\prime}_{w}(x)$

as

![]() $h ( T_{o}(x) - T_{m}(x) )$

, where

$h ( T_{o}(x) - T_{m}(x) )$

, where

![]() $h$

is the coefficient of heat transfer that is evaluated in terms of Nusselt number as

$h$

is the coefficient of heat transfer that is evaluated in terms of Nusselt number as

![]() $h=((Nu) k))/(2 r_{i})$

; and using

$h=((Nu) k))/(2 r_{i})$

; and using

![]() $H(x) = C_{p}(T)T_{m}(x)$

in the above equation, we obtain

$H(x) = C_{p}(T)T_{m}(x)$

in the above equation, we obtain

where

![]() $\alpha$

is the thermal diffusivity and

$\alpha$

is the thermal diffusivity and

![]() $\bar {u}$

is the mean flow velocity of the mixture. Since the mean flow temperature at the inlet of the quartz tube (

$\bar {u}$

is the mean flow velocity of the mixture. Since the mean flow temperature at the inlet of the quartz tube (

![]() $x=0\,\rm mm$

) is known, (3.5) can be used to march spatially along the combustor axis to obtain the mean flow temperature profile (axially).

$x=0\,\rm mm$

) is known, (3.5) can be used to march spatially along the combustor axis to obtain the mean flow temperature profile (axially).

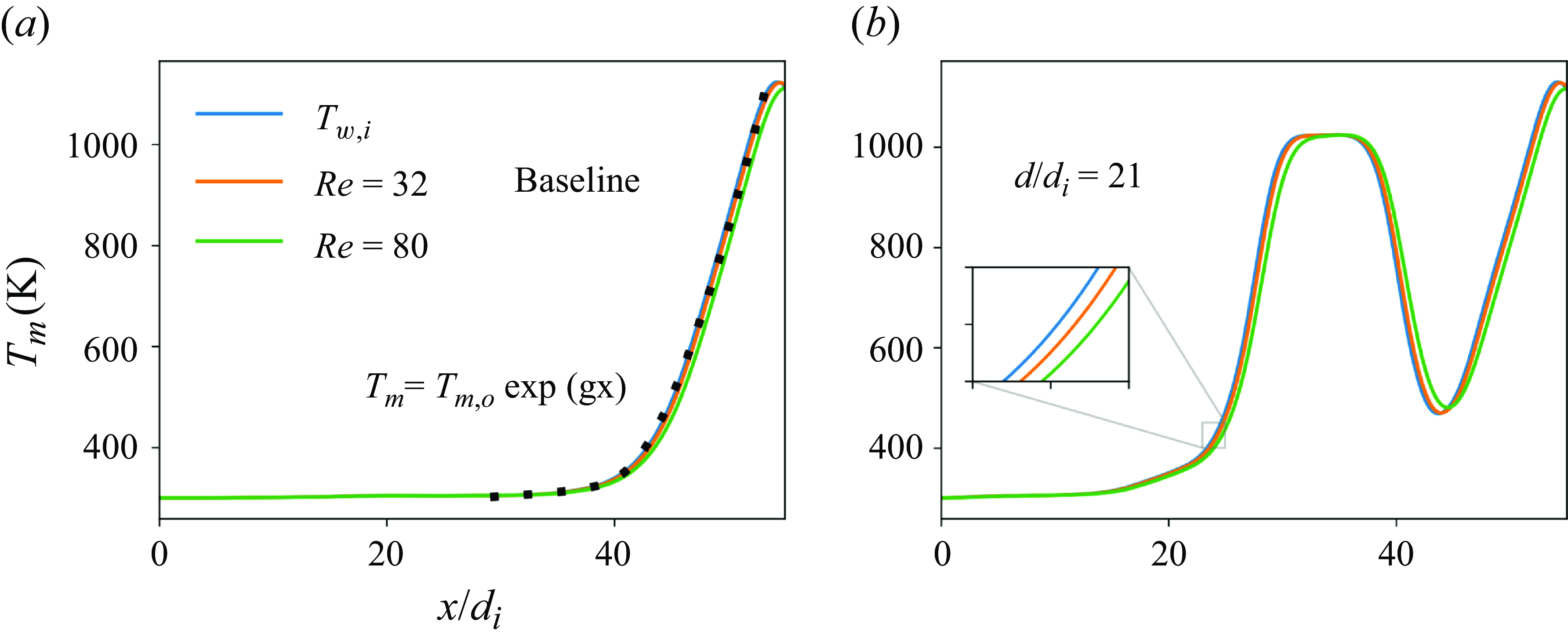

Figure 5 plots the axial variation of the mean flow temperature for the baseline configuration and the case corresponding to

![]() ${d}/{d_i}=21$

, at the Reynolds number of

${d}/{d_i}=21$

, at the Reynolds number of

![]() $32$

and

$32$

and

![]() $80$

(similar trends are observed for other values of

$80$

(similar trends are observed for other values of

![]() $ {d}/{d_i}$

and

$ {d}/{d_i}$

and

![]() $Re$

and is hence not presented in the plots). In the range of

$Re$

and is hence not presented in the plots). In the range of

![]() $x/d_{i}$

, where the wall temperature gradient is positive (

$x/d_{i}$

, where the wall temperature gradient is positive (

![]() ${{\rm d}T_{w,i}}/{{\rm d}x} \gt 0$

), the plots show that the mean flow temperature drops as the Reynolds number increases, and the reverse is true when

${{\rm d}T_{w,i}}/{{\rm d}x} \gt 0$

), the plots show that the mean flow temperature drops as the Reynolds number increases, and the reverse is true when

![]() ${{\rm d}T_{w,i}}/{{\rm d}x} \lt 0$

(figure 5a,b). In general, the mean flow temperature profile tends to shift downstream (with respect to

${{\rm d}T_{w,i}}/{{\rm d}x} \lt 0$

(figure 5a,b). In general, the mean flow temperature profile tends to shift downstream (with respect to

![]() $T_{w,i}$

) with increasing Re, and this downstream shift becomes more pronounced at higher Reynolds numbers. The plots imply that in the regions where the temperature gradient is positive, the reactants have to travel longer distances along the combustor axis to reach a given mean flow temperature as

$T_{w,i}$

) with increasing Re, and this downstream shift becomes more pronounced at higher Reynolds numbers. The plots imply that in the regions where the temperature gradient is positive, the reactants have to travel longer distances along the combustor axis to reach a given mean flow temperature as

![]() $Re$

increases.

$Re$

increases.

Figure 5. (a,b) Plots of the mean flow temperature profiles in the baseline configuration and at

![]() $d/d_{i} = 21$

, respectively. The plots correspond to the Reynolds numbers of

$d/d_{i} = 21$

, respectively. The plots correspond to the Reynolds numbers of

![]() $32$

and

$32$

and

![]() $80$

and are plotted alongside the inner wall temperature profile.

$80$

and are plotted alongside the inner wall temperature profile.

Section S3 in the supplementary materials presents a finite volume based numerical simulation to estimate the mean flow temperature, accounting for the conjugate heat transfer between the combustor tube walls and the internal flow. The plots in the section demonstrate a strong agreement between the theoretical estimate of the mean flow temperature (presented here) and the estimation of

![]() $T_m$

from the numerical simulations.

$T_m$

from the numerical simulations.

3.3. Baseline configuration

This section explores the dynamics of the unsteady flame regimes across the space of

![]() $Re$

and

$Re$

and

![]() $\Phi$

in the baseline configuration.

$\Phi$

in the baseline configuration.

3.3.1. Flames with repetitive extinction and ignition

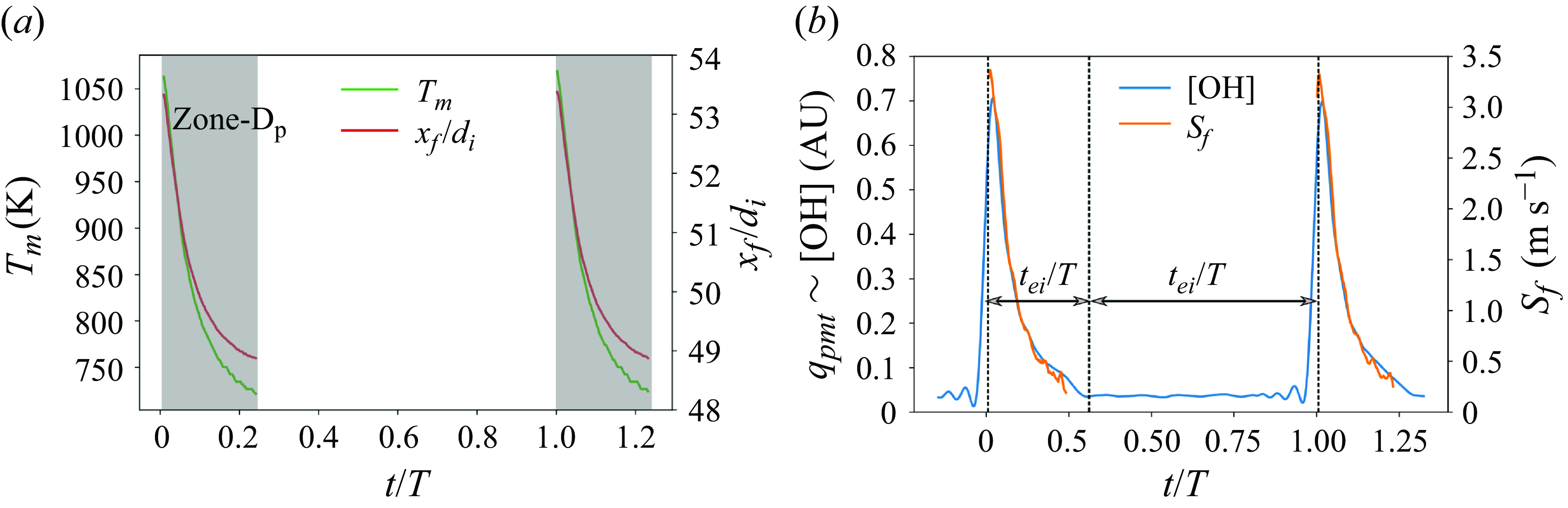

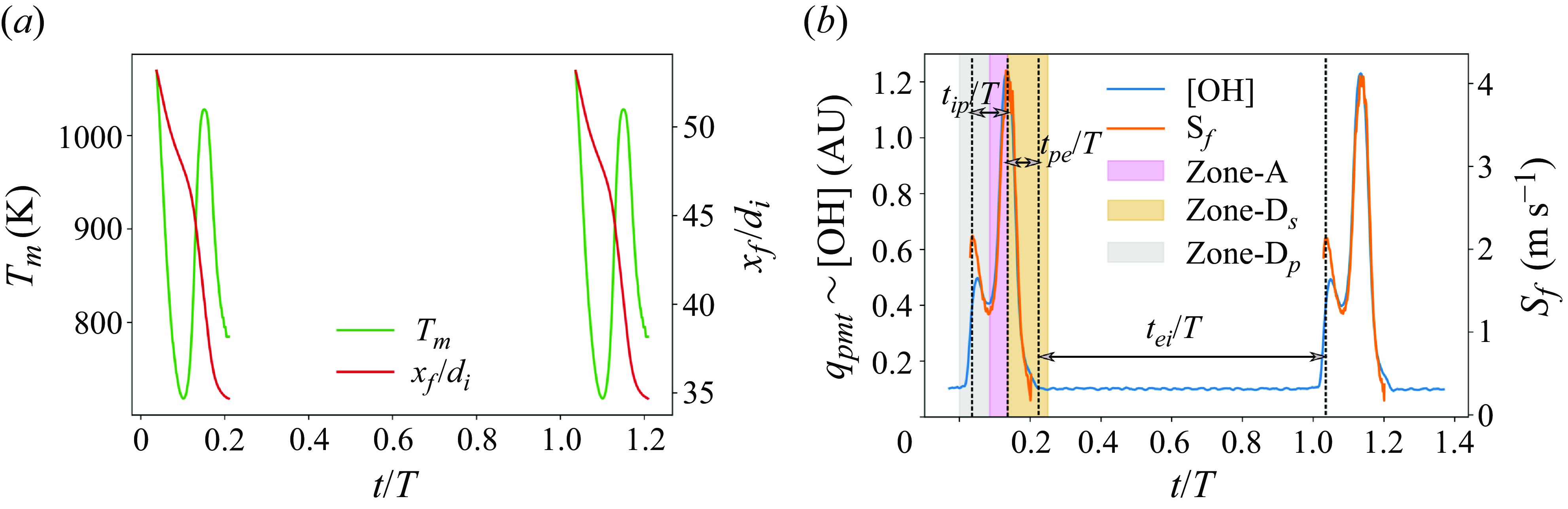

Figure 6 presents the typical OH* chemiluminescence signal, flame position (

![]() $x_f$

) and propagation speed (

$x_f$

) and propagation speed (

![]() $S_f$

) in a FREI cycle. Ignition is marked by simultaneous peaks in OH* chemiluminescence and flame speed profiles and is followed by a decay in both signals as the flame propagates upstream. The flame eventually extinguishes after traversing a characteristic distance.

$S_f$

) in a FREI cycle. Ignition is marked by simultaneous peaks in OH* chemiluminescence and flame speed profiles and is followed by a decay in both signals as the flame propagates upstream. The flame eventually extinguishes after traversing a characteristic distance.

Figure 6. (a) Flame position is plotted alongside the corresponding mean flow temperature of the unburnt reactants in a typical FREI cycle. (b) The OH* chemiluminescence signal is plotted alongsidethe flame propagation speed (

![]() $S_{f}$

). The plots correspond to

$S_{f}$

). The plots correspond to

![]() $Re = 48$

at an equivalence ratio of

$Re = 48$

at an equivalence ratio of

![]() $1.0$

. In the figure,

$1.0$

. In the figure,

![]() $t_{ie}$

represents the ignition-to-extinction time scale,

$t_{ie}$

represents the ignition-to-extinction time scale,

![]() $t_{ei}$

denotes the flame re-ignition time scale and

$t_{ei}$

denotes the flame re-ignition time scale and

![]() $T$

is the time period of FREI oscillations.

$T$

is the time period of FREI oscillations.

The observed flame dynamics can be understood using the analytical model for flame propagation in narrow channels developed by Daou & Matalon (Reference Daou and Matalon2002). It should be noted that while the model was developed for the asymptotic limit where

![]() $2l_f/d_{i} \gt \gt 1$

(where

$2l_f/d_{i} \gt \gt 1$

(where

![]() $l_f$

is the flame thickness), the qualitative trends– which are the primary focus of the current study – remain valid for

$l_f$

is the flame thickness), the qualitative trends– which are the primary focus of the current study – remain valid for

![]() $2l_f/d_{i} \geq 0.135$

(Daou & Matalon Reference Daou and Matalon2002). Based on our experimental data, the minimum value of

$2l_f/d_{i} \geq 0.135$

(Daou & Matalon Reference Daou and Matalon2002). Based on our experimental data, the minimum value of

![]() $2l_f/d_{i}$

corresponding to the conditions in this study is 0.21. Therefore, the model is applicable to the experimental space explored in this work. Therefore, we have

$2l_f/d_{i}$

corresponding to the conditions in this study is 0.21. Therefore, the model is applicable to the experimental space explored in this work. Therefore, we have

The model non-dimensionalises flame propagation speed as

![]() $V={2}/{3} ({1}/{\bar {u}}\left |{{\rm d}x_f}/{{\rm d}t}\right |+1 )$

, which can be rewritten in terms of

$V={2}/{3} ({1}/{\bar {u}}\left |{{\rm d}x_f}/{{\rm d}t}\right |+1 )$

, which can be rewritten in terms of

![]() $S_{f}$

as

$S_{f}$

as

![]() $V={2}/{3} ({S_f}/{\bar {u}} )$

. The heat losses at the combustor walls are accounted for using a non-dimensional parameter,

$V={2}/{3} ({S_f}/{\bar {u}} )$

. The heat losses at the combustor walls are accounted for using a non-dimensional parameter,

![]() $\kappa$

, defined as

$\kappa$

, defined as

where

![]() $E$

is the activation energy of the one-step reaction that describes the chemical activity,

$E$

is the activation energy of the one-step reaction that describes the chemical activity,

![]() $q_{w}^{\prime \prime }$

is the heat flux at the inner walls of the combustor tube,

$q_{w}^{\prime \prime }$

is the heat flux at the inner walls of the combustor tube,

![]() $l_{f}$

describes the flame thickness,

$l_{f}$

describes the flame thickness,

![]() $R_{o}$

is the universal gas constant and

$R_{o}$

is the universal gas constant and

![]() $T_{a}$

is the adiabatic flame temperature. The wall heat flux,

$T_{a}$

is the adiabatic flame temperature. The wall heat flux,

![]() $q_{w}^{\prime \prime }$

, can be expressed as

$q_{w}^{\prime \prime }$

, can be expressed as

![]() $\bar {h} (T_a-T_{w,i} ),$

where

$\bar {h} (T_a-T_{w,i} ),$

where

![]() $\bar {h}$

is the effective heat transfer coefficient. The plots in figure 5(a) depict that the inner wall temperatures are close to the mean flow temperatures at a given axial location. We can thus approximate

$\bar {h}$

is the effective heat transfer coefficient. The plots in figure 5(a) depict that the inner wall temperatures are close to the mean flow temperatures at a given axial location. We can thus approximate

![]() $ (T_a-T_{w,i} )$

as

$ (T_a-T_{w,i} )$

as

![]() $ (T_a-T_m )$

in the expression for

$ (T_a-T_m )$

in the expression for

![]() $q_{w}^{\prime \prime }$

. Here,

$q_{w}^{\prime \prime }$

. Here,

![]() $ (T_a-T_m )$

can be further scaled as

$ (T_a-T_m )$

can be further scaled as

![]() $({Q_RY_F})/{C_p}$

based on energy balance between the reactants and products (Daou & Matalon Reference Daou and Matalon2002; Law Reference Law2006). Thus,

$({Q_RY_F})/{C_p}$

based on energy balance between the reactants and products (Daou & Matalon Reference Daou and Matalon2002; Law Reference Law2006). Thus,

![]() $\kappa$

reduces to

$\kappa$

reduces to

\begin{align} \kappa =E\bar {h}\left (\frac {Q_RY_F}{C_p}\right )\frac {l_f^2}{R_o^2T_a^2r_i}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \kappa =E\bar {h}\left (\frac {Q_RY_F}{C_p}\right )\frac {l_f^2}{R_o^2T_a^2r_i}. \end{align}

As evident from the above equation, for a fixed value of Reynolds number and equivalence ratio,

![]() $\kappa$

scales inversely with

$\kappa$

scales inversely with

![]() $T_a^2$

:

$T_a^2$

:

As the FREI flame auto-ignites in the primary heating zone and propagates upstream, it encounters reactants with progressively decaying mean flow temperatures (see figure 6a). Since

![]() $T_a$

scales as

$T_a$

scales as

![]() $ (T_m+\ {(Q_RY_F)}/{C_p} )$

,

$ (T_m+\ {(Q_RY_F)}/{C_p} )$

,

![]() $T_a$

drops during the propagation phase, increasing

$T_a$

drops during the propagation phase, increasing

![]() $\kappa$

. This reduces

$\kappa$

. This reduces

![]() $V$

as per (3.6), causing

$V$

as per (3.6), causing

![]() $S_f$

to drop during the propagation phase, and this is evident in figure 6(b), which depicts the same trend experimentally. To plot in section S4 of the supplementary materials depicts the inverse dependence of

$S_f$

to drop during the propagation phase, and this is evident in figure 6(b), which depicts the same trend experimentally. To plot in section S4 of the supplementary materials depicts the inverse dependence of

![]() $V$

on

$V$

on

![]() $\kappa$

. Given that the flame speed (

$\kappa$

. Given that the flame speed (

![]() $S_f$

) scales with the reaction rate (Law Reference Law2006),

$S_f$

) scales with the reaction rate (Law Reference Law2006),

![]() $\omega$

, a corresponding decay is expected in

$\omega$

, a corresponding decay is expected in

![]() $\omega$

, and is corroborated by the OH* chemiluminescence signal of the flame (figure 6b), which also scales with the reaction rate.

$\omega$

, and is corroborated by the OH* chemiluminescence signal of the flame (figure 6b), which also scales with the reaction rate.

Following the analytical model outlined in (3.6) and the plot in section S4 of the supplementary materials, the non-dimensional heat loss parameter,

![]() $\kappa$

, increases and reaches a local maximum of 0.18 as the upstream traversing flame nears extinction (Daou & Matalon Reference Daou and Matalon2002). This is accompanied by a simultaneous decay in

$\kappa$

, increases and reaches a local maximum of 0.18 as the upstream traversing flame nears extinction (Daou & Matalon Reference Daou and Matalon2002). This is accompanied by a simultaneous decay in

![]() $V$

, which drops to a minimum of 2/3 close to extinction. At this point,

$V$

, which drops to a minimum of 2/3 close to extinction. At this point,

![]() ${{\rm d}x_f}/{{\rm d}t}$

will reduce to zero (as per the definition of

${{\rm d}x_f}/{{\rm d}t}$

will reduce to zero (as per the definition of

![]() $V$

), causing the flame to cease propagation and extinguish.

$V$

), causing the flame to cease propagation and extinguish.

Figure 7 presents the ignition, extinction, flame speed and OH* chemiluminescence characteristics of the baseline FREI regime as a function of the premixture Reynolds number. As

![]() $Re$

increases at a given equivalence ratio, the reactant mass flow rate increases. Mathematically, this can be expressed as

$Re$

increases at a given equivalence ratio, the reactant mass flow rate increases. Mathematically, this can be expressed as