Highlights

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) inhibitor use for migraine prophylaxis has increased in Canada since 2018.

-

After CGRP inhibitor initiation, 57% had concomitant use with a different prophylactic migraine medication class, and 30% stopped use.

-

Migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use were lower after CGRP inhibitor initiation versus before.

Introduction

Migraine is a common disorder characterized by recurrent headache attacks that are often moderate-to-severe in nature and associated with other neurological symptoms. Reference Pescador Ruschel and De Jesus1 Between 8.3% and 10.2% of people living in Canada report being diagnosed with migraine by a healthcare professional, with females reporting living with migraine more than twice as often as males. Reference Graves, Gerber and Berrigan2,Reference Ramage-Morin and Gilmour3 Migraine can be classified as episodic (<15 headache days per month) or chronic (≥15 headache days per month for >3 months with the features of migraine headache on ≥8 days per month). 4 Migraine attacks can significantly impair function and negatively impact social and family life, workplace productivity and finances; Reference Buse, Fanning and Reed5,Reference Begasse de Dhaem and Sakai6 the 2021 Global Burden of Disease study ranked migraine as the second leading cause of disability among neurological conditions in North America. Reference Steinmetz, Seeher and Schiess7 The economic burden of migraine on healthcare systems and society is also substantial. Reference Amoozegar, Khan, Oviedo-Ovando, Sauriol and Rochdi8–Reference Lambert, Carides, Meloche, Gerth and Marentette10

Comprehensive migraine therapy includes management of lifestyle factors and triggers, use of acute therapies to address migraine attacks once started and prophylactic therapies to decrease the number and severity of migraine attacks. Reference Becker, Findlay, Moga, Scott, Harstall and Taenzer11 Acute migraine medications recommended by the Canadian Headache Society include pharmacotherapies for pain such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and drugs indicated for migraine such as ergot derivatives and triptans; Reference Becker12 more recently, some gepants have been recommended for the acute treatment of migraine. Reference Ailani, Burch and Robbins13 Prophylactic treatments include oral drugs such as antidepressants, antiepileptics and antihypertensives, most of which are used off-label, along with Health Canada-approved drugs indicated for migraine, such as onabotulinumtoxinA injections, and, more recently, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) inhibitors. Reference Becker, Findlay, Moga, Scott, Harstall and Taenzer11,Reference Medrea, Cooper and Langman14 First approved in 2018, prophylactic CGRP inhibitors currently available in Canada include the monoclonal antibodies erenumab, galcanezumab, fremanezumab and eptinezumab, along with the small molecule CGRP receptor antagonist (gepants) atogepant. Although CGRP inhibitors have a favorable safety and tolerability profile, display good efficacy and are strongly recommended by organizations such as the Canadian Headache Society, American Headache Society and the European Headache Federation (as a first-line treatment option, particularly among those living with high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine), Reference Medrea, Cooper and Langman14–Reference Sacco, Amin and Ashina16 these drugs are costly and typically not covered by provincial supplementary drug plans unless conventional therapies have been attempted first. Thus, appropriate and cost-effective integration of CGRP inhibitors is a priority for decision-makers. However, there is a gap in knowledge about the current real-world use of CGRP inhibitors for migraine prophylaxis and associated health system impacts. The objective of this study was to describe CGRP inhibitor use and treatment patterns and migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use among adults who initiated a prophylactic CGRP inhibitor in Canada. This study resulted from a Canadian policymaker query about CGRP inhibitors that was posed to the Post-Market Drug Evaluation (PMDE) program within Canada’s Drug Agency.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective, observational, population-based cohort study was conducted using administrative health data between 2017 and 2023 (inclusion period 2018–2023, with a 1-year lookback for determination of baseline characteristics) from the six Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Saskatchewan. Ethics approval was received from the Research Ethics Boards at the University of Alberta (Pro00140139) and Dalhousie University (2024-7294; for use of Nova Scotia data); a waiver of consent was applied. This study was reported according to the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data guidelines. Reference Benchimol, Smeeth and Guttmann17

Data source

Canadian provinces have single-payer health systems and provide publicly funded medically necessary health care for all residents; prescription medications are not universally covered. Data coverage from the six provinces included in this study comprised ∼45% of the adult population in Canada (2023 adult population – Canada: 32,590,347; Alberta: 3,668,440; British Columbia: 4,616,436; Manitoba: 1,137,301; Nova Scotia: 881,137; Quebec: 7,187,229 [data coverage in this study: ∼3,306,125]; Saskatchewan: 932,969). 18 Researchers obtained Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec data from each province, and data from British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan was obtained from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Person-level, linked (using a unique individual identifier [Personal Health Number]) data extracts were used from the following listed databases. Provincial registry data from Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec contains information for all residents with healthcare coverage; demographic information, migration in and out of the province and vital status are included; CIHI does not have access to provincial registry data, and therefore, this information was not included for British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Community pharmacy–dispensed prescription medication (capturing all dispensations regardless of payer) from Alberta (Pharmaceutical Information Network), British Columbia (National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System [NPDUIS]), Manitoba (NPDUIS), Nova Scotia (Drug Information System) and Saskatchewan (NPDUIS) contains full population-level coverage; Quebec dispensation data contains information for ∼46% of residents (i.e., seniors [≥65 years] and other publicly insured individuals) and was obtained from the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec. Inpatient data (Discharge Abstract Database in Alberta and Nova Scotia; Maintenance et exploitation des données pour l’étude de la clientèle hospitalière [MED-ÉCHO] in Quebec), ambulatory care data (publicly funded facility-based outpatient treatments and procedures including same-day surgery, day procedures, emergency room visits and community rehabilitation program services; National Ambulatory Care Reporting System in Alberta, Banque de données communes des urgences [emergency department visits] and Système d’information et de gestion des urgences [non-emergent ambulatory care visits] in Quebec) and physician claims data (Practitioner Claims in Alberta; Medical Services Insurance Physician Billings in Nova Scotia; Services médicaux rémunérés à l’acte in Quebec) were used to determine clinical characteristics (Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec) and healthcare use (Alberta). Inpatient and ambulatory care data include demographic, administrative, diagnostic and procedural information; most responsible and secondary diagnostic fields are included and use International Classification of Diseases – Version 10 – Canadian Enhancement (ICD-10-CA) codes. Physician claims data includes information such as demographics, date of service and health service and diagnostic ICD – Version 9 – Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Publicly available Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion File Plus data was used to ascertain geography-aggregated demographics, and census data was used for adult population denominators. 18,19

Cohort selection

The cohort included those who (1) received ≥1 community pharmacy dispensation for a prophylactic CGRP inhibitor (Supplementary Table 1) between December 4, 2018 (the first marketed date for a prophylactic CGRP inhibitor in Canada), and March 31, 2023, and (2) were aged ≥18 years on the date of their initial prophylactic CGRP inhibitor dispensation (index date).

CGRP inhibitor treatment patterns were examined among individuals in the cohort who (1) had an index date between December 4, 2018, and March 31, 2022 (all six provinces), and (2) had ≥1 year of provincial healthcare coverage after the index date for those in Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec. Migraine-related acute medication (all six provinces; Supplementary Table 1) and healthcare use (Alberta) were measured among those in the cohort who (1) had an index date between December 4, 2018, and March 31, 2022 (all six provinces), and (2) had ≥1 year of provincial healthcare coverage before and after the index date, the date of switch to a second CGRP inhibitor or the date that the initial CGRP inhibitor was discontinued for those in Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec; the switch or discontinuation had to occur within the first year after the index date without resumption of the initial CGRP inhibitor within 1 year of the date of the switch or discontinuation.

Study measures

Incidence and prevalence

Incident CGRP inhibitor use was calculated based on the annual (fiscal year; April 1 to March 31) number of adults who received their first-ever dispensation of a CGRP inhibitor from a community pharmacy within that year, with no prior CGRP inhibitor dispensations dating back to December 4, 2018. The annual (fiscal year) prevalence of CGRP inhibitor use was calculated based on the number of adults who had ≥1 CGRP inhibitor dispensation. Annual adult population estimates from Statistics Canada were used for the reference population. 18 Rates were standardized (age- and sex-adjusted) to the Canadian adult population using the direct method.

Baseline characteristics

Demographic characteristics (all six provinces) included age, sex and urban/rural residence (determined by the second digit of the postal code in Alberta and the statistical area classification type [from the Postal Code Conversion File Plus] in other provinces) on the index date. Clinical characteristics (Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec) included the Charlson Comorbidity Index and specific migraine-related health conditions. A Charlson Comorbidity Index score was determined during the 1-year pre-index period that was based on ICD-10-CA and ICD-9-CM codes of 17 different specific health conditions weighted according to their potential for influencing mortality (Supplementary Table 2). Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie20,Reference Lix, Smith and Pitz21 Migraine-related health conditions included anxiety, Reference Marrie, Fisk and Yu22 asthma, Reference Tonelli, Wiebe and Fortin23 cardiovascular disease, Reference Tonelli, Wiebe and Fortin23–Reference Tu, Mitiku, Lee, Guo and Tu27 depression, Reference Doktorchik, Patten and Eastwood28,Reference Alaghehbandan, Macdonald, Barrett, Collins and Chen29 epilepsy, Reference Reid, St Germaine-Smith and Liu30 hypertension Reference Tonelli, Wiebe and Fortin23 and obstructive sleep apnea; Reference Laratta, Tsai, Wick, Pendharkar, Johannson and Ronksley31 each participant was classified with respect to the presence or absence of a condition determined during the 1-year pre-index period (Supplementary Table 3). Socioeconomic status was determined by the Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan (reported dimensions included economic dependency, ethno-cultural composition and residential instability); this is an area based index that uses Canadian Census of Population 2021 microdata to measure key dimensions at the dissemination area level, which was linked to postal codes and presented based on quintiles. 32

CGRP inhibitor treatment patterns

From the index date, the migraine-related medication (Supplementary Table 1) treatment patterns (measured in all six provinces) of (1) discontinuation of all prophylactic migraine medication (a gap in supply of >120 days of all prophylactic migraine medication), (2) treatment break (discontinuation of all prophylactic migraine medication, followed by the resumption of the most recent previously dispensed CGRP inhibitor), (3) switch (change to a different prophylactic migraine medication class between 30 days before and 120 days after the last day of supply of the discontinued baseline CGRP inhibitor) and (4) concomitant use (>30 concurrent days of supply with a different prophylactic migraine medication class) were determined during 1-, 2-, 3- and 4-year post-index periods, up to March 31, 2023. Time (measured in years) from the index date to discontinuation of all prophylactic migraine medication, first treatment break, switch to a second CGRP inhibitor and first switch from any CGRP inhibitor to onabotulinumtoxinA injection was measured in Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec; the probability of these events occurring was also measured at 1 year and 2 years after the index date.

Migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use

Community pharmacy–dispensed prescription migraine-related acute medications (all six provinces) and migraine-related (ICD-10-CA G43 located in the most responsible diagnostic field; ICD-9-CM 346 located in any diagnostic field) healthcare use (physician visits, non-emergent ambulatory care visits, emergency department visits and hospitalizations; Alberta) were measured during the 1 year before and after the index date; medication and healthcare use were also measured before and after the date of switch to a second CGRP inhibitor or the date that the initial baseline CGRP inhibitor was discontinued during the first year after the index date.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as counts and percentages and means with standard deviations (SD). For comparisons between the 1-year period before and after the index date, the date of switch to a second CGRP inhibitor and the date that the initial baseline CGRP inhibitor was discontinued, independent t-tests and Chi-square tests were employed for migraine-related acute medication use across the six provinces (as only aggregated data was available), and paired t-tests (for continuous variables) and McNemar’s tests (for paired proportion comparison) were employed for migraine-related healthcare resource use in Alberta. Mean differences and odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) were calculated. Kaplan–Meier estimates were used to estimate time from CGRP inhibitor initiation to discontinuation, treatment break or switch and probability of the events at 1 year and 2 years after initiation, considering different follow-up durations; out-migration was treated as a censoring event within the Kaplan–Meier framework. In accordance with provincial data custodian privacy standards, outcomes with 1–4 (British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Saskatchewan) or 1–9 (Alberta) individuals were suppressed (reported as <10 with associated proportions presented based on the number 3 or 5, respectively); where applicable, other outcomes were censored (e.g., presented as a range; associated proportions were presented based on the mid number of the range), so the number of individuals within the small cell size outcome could not be calculated and potentially identified. A 2-sided significance level of 0.05 was applied for all statistical tests. Analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 and R (version 4.4.0) statistical software.

Results

Cohort selection

After applying eligibility criteria, 12,851 adults were included in the cohort (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure 1 includes data linkage); 5,123 (39.3%) from Alberta, 3,725 (29.0%) from British Columbia, 1,055 (8.2%) from Manitoba, 714 (5.6%) from Nova Scotia, 1,513–1,516 (1,515 used for calculations; 11.8%) from Quebec and 719 (5.6%) from Saskatchewan.

Figure 1. Cohort selection flow diagram. CGRP = calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Incidence and prevalence

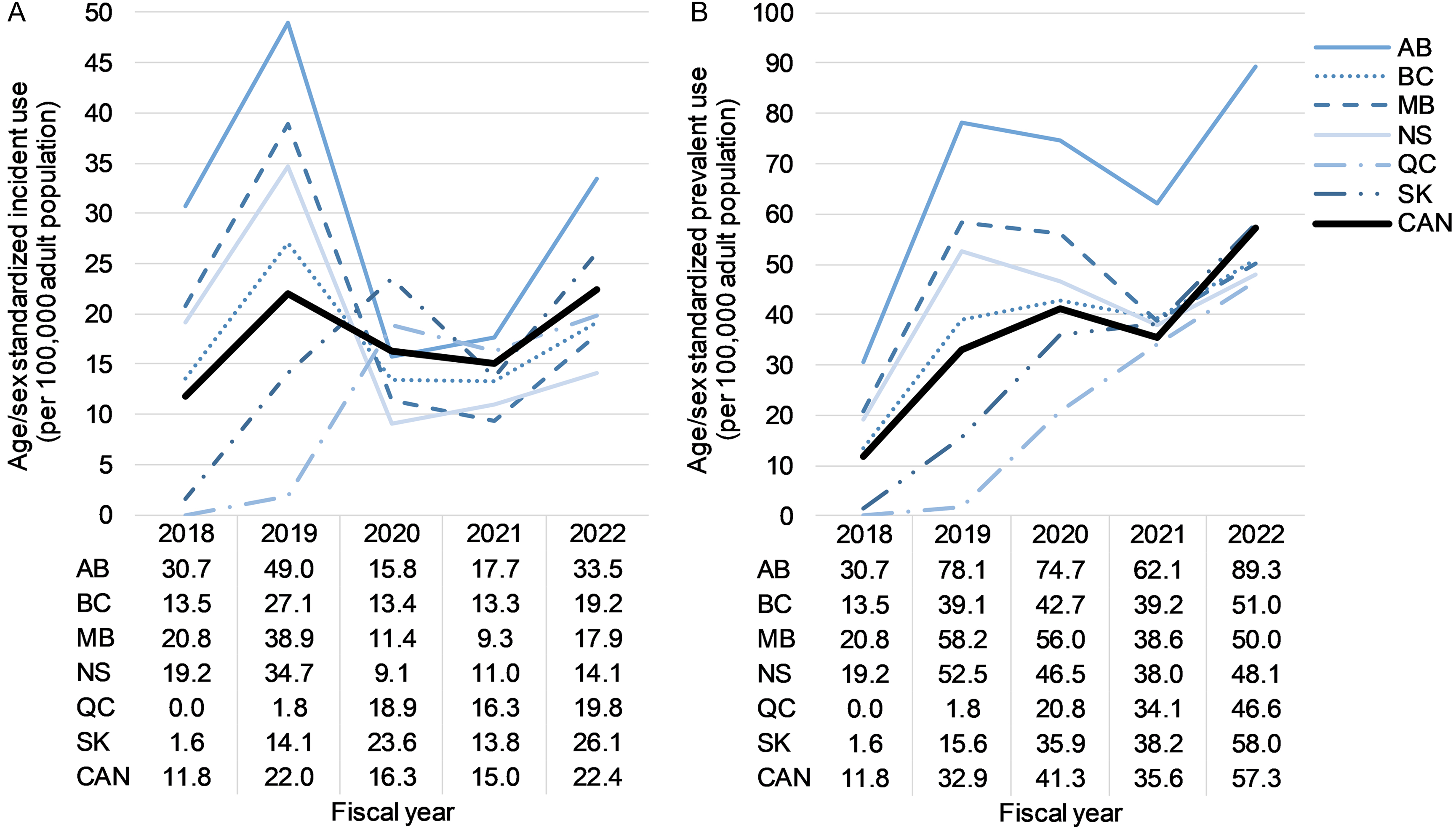

Age/sex standardized annual CGRP inhibitor incident use increased from 11.8 per 100,000 adults in 2018/2019 to 22.4 per 100,000 adults in 2022/2023 (Figure 2); Supplementary Table 4 shows annual incident use by age and sex. Regarding specific CGRP inhibitors, all individuals initiated erenumab in 2018/2019 (the only CGRP inhibitor on the market in Canada); in 2022/2023, the majority of individuals initiated fremanezumab (61.9%), 20.5% initiated galcanezumab, 15.1% initiated erenumab, 2.2% initiated eptinezumab and 0.4% initiated atogepant (Table 1).

Figure 2. Age/sex standardized annual (a) incident and (b) prevalent calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibitor use between December 4, 2018, and March 31, 2023. AB = Alberta; BC = British Columbia; CAN = Canada; MB = Manitoba; NS = Nova Scotia; QC = Quebec; SK = Saskatchewan.

Table 1. Annual incident and prevalent prophylactic calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibitor use (all six provinces) presented according to each drug between December 4, 2018 and March 31, 2023

Note: “–” indicates the drug was not marketed in Canada during the fiscal year. CGRP = calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Age/sex standardized annual prevalence of CGRP inhibitor use increased from 11.8 per 100,000 adults in 2018/2019 to 57.3 per 100,000 adults in 2022/2023 (Figure 2); Supplementary Table 4 shows annual prevalent use by age and sex. The proportion of individuals with prevalent use of erenumab was lower each year after 2018/2019 (Table 1). In 2022/2023, the most commonly used CGRP inhibitor was fremanezumab (38.9%), followed by erenumab (38.7%), galcanezumab (26.0%), eptinezumab (3.3%) and atogepant (0.6%) (Table 1).

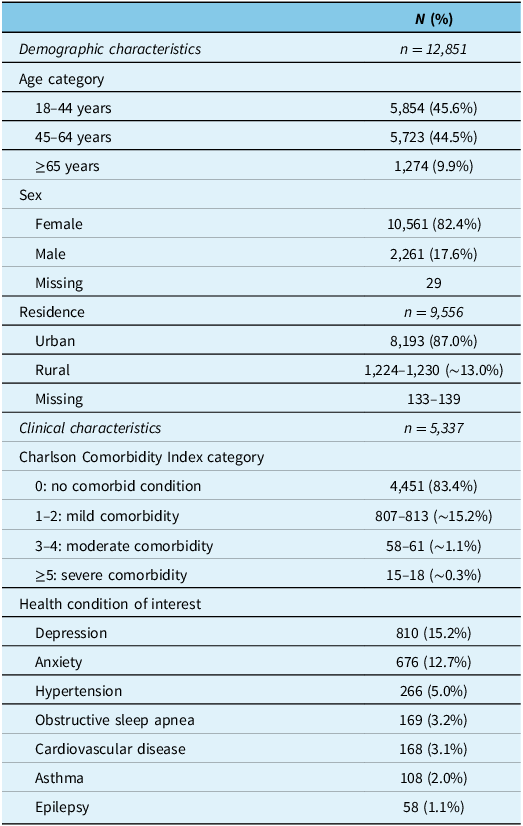

Baseline characteristics

On the index date, the most common age group was 18–44 years (45.6%), followed by 45–64 years (44.5%), then ≥65 years (9.9%); females comprised the majority of the cohort (82.4%), and most lived in urban areas (87.0%) (Table 2). Most individuals had a Charlson Comorbidity Index category of 0 (83.4%), and the most common (>10%) health conditions of interest that individuals were living with were depression (15.2%) and anxiety (12.7%) (Table 2). Socioeconomic status is shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Table 2. Baseline demographic (all six provinces) and clinical (Alberta, Nova Scotia and Quebec) characteristics of the cohort

CGRP inhibitor treatment patterns

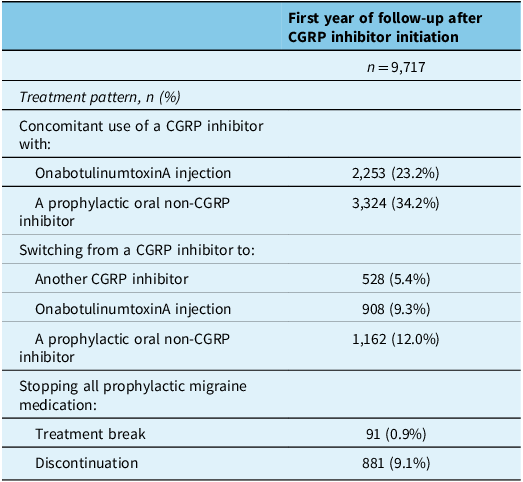

During the 1-year period after the index date, 57.4% had concomitant use with a different prophylactic migraine medication class (onabotulinumtoxinA injection: 23.2%; oral non-CGRP inhibitor: 34.2%) (Table 3). A total of 30.4% stopped use of a CGRP inhibitor – 21.3% switched to a different prophylactic migraine medication class (switched to onabotulinumtoxinA injection: 9.3%; switched to an oral non-CGRP inhibitor: 12.0%), and 9.1% discontinued all prophylactic migraine medication (Table 3). Switching from one CGRP inhibitor to another occurred in 5.4%, and returning to CGRP inhibitor use after stopping all prophylactic migraine medication occurred in 0.9% (Table 3). Supplementary Table 6 shows treatment patterns during the 2- to 4-year period after the index date. Supplementary Table 7 details the mean time from the index date until a switch, treatment break or discontinuation; the probability of these events occurring at 1 year and 2 years after the index date is also presented.

Table 3. Treatment patterns presented during the 1-year period after initiation of a calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibitor (index date; all six provinces)

Note: Prophylactic oral non-CGRP inhibitor migraine medications included antidepressants, antiepileptics, antihypertensives and pizotifen (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). CGRP = calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Pre–post medication and healthcare use

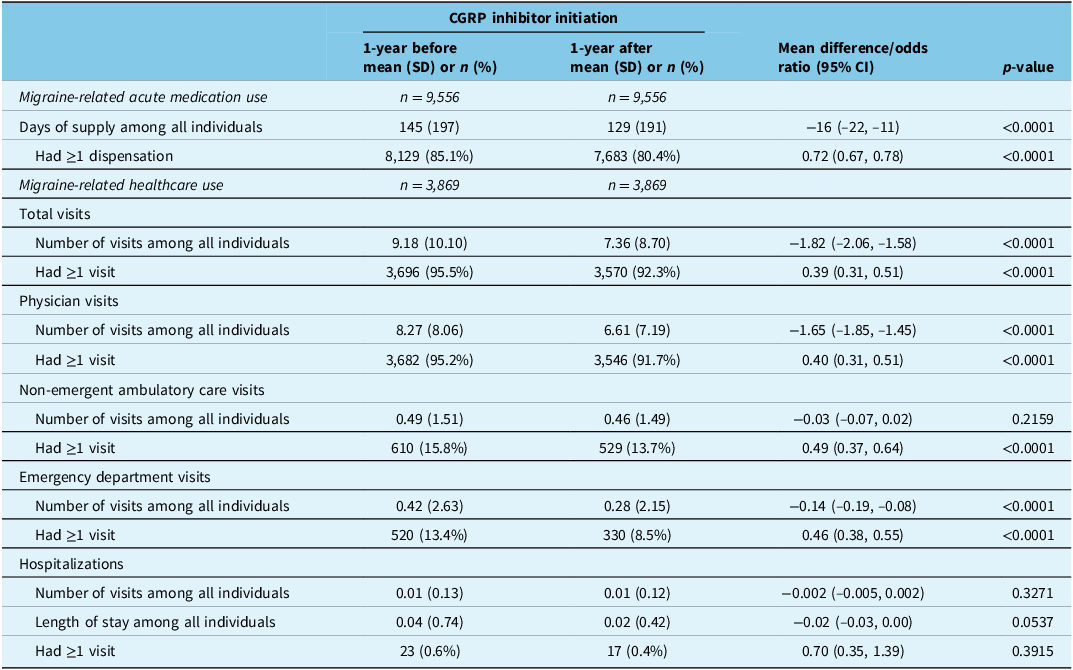

During the 1-year period after the index date (regardless of treatment pattern), the mean number of days of supply for migraine-related acute medication was lower compared with before (129 [SD: 191] versus 145 [SD: 197] days; mean difference: −16 [95% CI: −22, −11] days) among all individuals (n = 9,556 [all six provinces]) (Table 4). The proportion of individuals who received ≥1 dispensation for a migraine-related acute medication was 85.1% before the index date and 80.4% after (odds ratio: 0.72 [95% CI: 0.67, 0.78]) (Table 4).

Table 4. Migraine-related acute medication use (all six provinces) and healthcare use (Alberta) during the 1-year period before and after calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibitor initiation (index date)

Note: Migraine-related acute medications included ergots, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids and triptans (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). An independent t-test and Chi-square test were used for medication use as only aggregated data was available; paired t-tests and McNemar’s tests were used for healthcare use. CGRP = calcitonin gene-related peptide; CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation.

The mean number of migraine-related healthcare visits of any kind was lower during the 1-year period after the index date versus before (7.36 [SD 8.70] versus 9.18 [SD 10.10]; mean difference: −1.82 [95% CI: −2.06, −1.58]) among all individuals ( n = 3,869 [Alberta]); this was driven by fewer physician visits (6.61 [7.19] versus 8.27 [8.06]; −1.65 [95% CI: −1.85, −1.45]) and fewer emergency department visits (0.28 [2.15] versus 0.42 [2.63]; −0.14 [95% CI: −0.19, −0.08]) (Table 4). The proportion of individuals who had ≥1 migraine-related healthcare visit of any kind was 95.5% before and 92.3% after the index date (McNemar’s odds ratio: 0.39 [0.31, 0.51]); this occurred for physician visits (before: 95.2%, after: 91.7%; McNemar’s odds ratio: 0.40 [0.31, 0.51]), non-emergent ambulatory care visits (before: 15.8%, after: 13.7%; McNemar’s odds ratio: 0.49 [0.37, 0.64]) and emergency department visits (before: 13.4%; after: 8.5%; McNemar’s odds ratio: 0.46 [0.38, 0.55]) (Table 4). Supplementary Table 8 shows migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use for those who switched to a second CGRP inhibitor and those who discontinued CGRP inhibitor use during the 1-year post-index period; both are anchored to the date of switch or discontinuation of the initial CGRP inhibitor, respectively.

Discussion

In this retrospective, observational, population-based cohort study of adults who received a prophylactic CGRP inhibitor, incident and prevalent use, treatment patterns and migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use were described between December 4, 2018, and March 31, 2023, using administrative health data in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Saskatchewan. CGRP inhibitor incident and prevalent use increased from 2018/2019 to 2022/2023; erenumab use decreased over time, as use of newer agents increased, particularly fremanezumab. The characteristics of adults who initiated a CGRP inhibitor were consistent with epidemiological findings for those living with migraine; individuals were often middle-aged and female, and the most common comorbidities were depression and anxiety. Reference Burch, Buse and Lipton33 During the 1-year period after CGRP inhibitor initiation, most (57.4%) had concomitant use with a different prophylactic migraine medication class, and 30.4% stopped use (switched to a different prophylactic migraine medication class or discontinued all prophylactic migraine medications). Migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use were lower after CGRP inhibitor initiation compared with before. Findings from this study provide a real-world description of the evolving landscape of CGRP inhibitor use within the context of changing clinical practice standards to integrate new migraine treatments.

A large retrospective, observational study that used administrative health data from the USA found that among adults who received a migraine medication between 2017 (n = 161,396) and 2020 (n = 240,330), CGRP inhibitors had the largest increase in use over this time period – the per person per month use of CGRP inhibitors increased by 178% from 2018 (0.24) to 2020 (0.65). Reference Nguyen, Munshi and Peasah34 Findings from the current study also show that overall CGRP inhibitor use increased in Canada during the observation period. We found that among the different CGRP inhibitors, erenumab use decreased, and newer agents increased, particularly fremanezumab. While clinical evaluative data would be needed to confirm the reasons for this observed shift, it is possible that the increased use of fremanezumab may be due, in part, to emerging evidence of its potential greater effectiveness. Reference Lampl, MaassenVanDenBrink and Deligianni35,Reference Sun, Cheng and Xia36 Two network meta-analyses, one focused on the comparative effectiveness of prophylactic migraine drugs versus placebo (74 unique randomized clinical trials; 32,990 participants) Reference Lampl, MaassenVanDenBrink and Deligianni35 and one on the comparative efficacy of CGRP inhibitors versus placebo (24 double-blind randomized clinical trials; 14,286 participants), Reference Sun, Cheng and Xia36 reported that all CGRP inhibitors were superior to placebo, with monthly fremanezumab (225 mg dose) displaying the numerically largest response in reducing monthly migraine days and achieving a 50% response rate over placebo. Reference Lampl, MaassenVanDenBrink and Deligianni35,Reference Sun, Cheng and Xia36 Other reasons for this observed shift may include tolerability, side effects such as constipation or elevated blood pressure, individual preference (e.g., convenience), ease of patient support program use and/or drug cost. Reference Medrea, Cooper and Langman14

The pathophysiology of migraine is complex, involving multiple pathways and receptors, each representing a specific therapeutic target for treatment. Reference Charles37 As a result, while a single prophylactic medication can be beneficial, some individuals may still experience migraine attacks frequently enough to require additional treatment or a switch to a different medication altogether. Studies investigating combination treatments for migraine prophylaxis report promising findings, including concomitant use of CGRP inhibitors with onabotulinumtoxinA injection (although currently not covered by provincial supplementary drug plans) or prophylactic oral non-CGRP inhibitor treatments. Reference Pellesi, Garcia-Azorin and Rubio-Beltrán38 In the current study, the majority (57.4%) of individuals had concomitant use of a CGRP inhibitor with a different prophylactic migraine medication class during the first year after CGRP inhibitor initiation. Based on expert consensus, the 2024 Updated Canadian Headache Society Migraine Prevention guidelines recommend that layering of treatment can be considered for refractory migraine. Reference Medrea, Cooper and Langman14 Further large-scale clinical trials are required to refine dual prophylaxis treatment and provide robust evidence. Though CGRP inhibitors are an effective treatment for migraine, reports indicate that 8–30% of individuals who initiate a CGRP inhibitor stop its use, mostly due to a lack of benefit or personal choice. Reference Alex, Vaughn and Rayhill39–Reference Pozo-Rosich, Dolezil and Paemeleire41 In alignment with these reports, 30.4% of individuals in the current study stopped use of a CGRP inhibitor during the first year after initiation – 12.0% switched to a prophylactic oral non-CGRP inhibitor treatment, 9.3% switched to onabotulinumtoxinA injection and 9.1% discontinued all prophylactic migraine medication. Comparatively, previous reports have shown that up to 86% of those who initiated an oral migraine prophylactic medication stopped its use during the first year. Reference Hepp, Dodick and Varon42,Reference Woolley, Bonafede, Maiese and Lenz43

As CGRP inhibitor use increases, the appropriate and cost-effective integration of this new drug class will need to consider benefits in quality of life that may be realized, along with the potential reduction in both direct healthcare costs and the societal burden of migraine. To this end, CGRP inhibitors have shown improved quality of life and productivity, along with a reduction in the number of monthly migraine days, acute migraine medication use and healthcare use among people living with migraine. Reference Lampl, MaassenVanDenBrink and Deligianni35,Reference Lipton, Cohen, Gandhi, Yang, Yeung and Buse44,Reference Ford, Foster, Stauffer, Ruff, Aurora and Versijpt45 Preliminary evidence from the current study supports these findings. Health economic and cost-effectiveness models have shown that treatment with CGRP inhibitors have the potential to reduce both direct healthcare costs and the societal burden of migraine; Reference Pozo-Rosich, Poveda, Crespo, Martinez, Rodriguez and Irimia46–Reference Siersbaek, Kilsdal, Jervelund, Antic and Bendtsen48 this is important because direct non-healthcare costs (e.g., transportation for medical appointments, childcare costs) and indirect costs (e.g., productivity loss) could account for up to 87% of the economic burden of migraine in Canada. Reference Amoozegar, Khan, Oviedo-Ovando, Sauriol and Rochdi8,Reference Lambert, Carides, Meloche, Gerth and Marentette10

Important strengths of this study are the large population-based design that covered almost half of the adult population in Canada and a high-quality source of administrative health data. However, this study is also subject to several limitations that should be taken into consideration when interpreting results. Retrospective administrative claims-based studies use administrative data (e.g., codes) as opposed to medical records (which contain detailed notes including diagnoses), and therefore, there is a potential for misclassification of the study groups or measures. To address this limitation, validated case definitions were used where possible. Provincial healthcare coverage information was not available from British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and therefore, some individuals may have unknowingly migrated out of these provinces during the observation period, which would have affected the calculation of CGRP inhibitor treatment patterns and migraine-related acute medication use; however, out-migration of adults from these provinces during the study period has been reported to be less than 2%. 18,49 While Kaplan–Meier analysis does not account for competing risks, the impact is expected to be minimal due to the low prevalence of death in the cohort. Community pharmacy–dispensed prescription drug data only provides information on prescription medication dispensations and may not represent actual medication use by individuals. Additionally, it is not known whether nonspecific migraine medications were taken specifically for migraine or other conditions such as arthritis, depression, hypertension or epilepsy. Use of over-the-counter medications, drug samples and non-pharmacotherapy self-management techniques is not captured within provincial administrative health data and is therefore not reported.

Conclusions

Findings from this population-based study show that CGRP inhibitor use among adults increased in Canada between 2018 and 2023. During the 1-year period after CGRP inhibitor initiation, it was observed that most adults had concomitant use with a different prophylactic migraine medication class, and some stopped CGRP inhibitor use altogether. In addition, lower migraine-related acute medication and healthcare use were seen after CGRP inhibitor initiation (versus before). Overall, the findings of this study provide a real-world description of CGRP inhibitor use that can be used to inform appropriate integration of this new migraine treatment. Future studies investigating the cost-effectiveness of this new drug class that consider quality of life, direct healthcare costs and the societal burden of migraine can further assist with informing decision-making.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2025.10506.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the provincial data custodians and CIHI, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study. Health Data Research Network of Canada assisted with the identification of provinces to be included in this study. Karleen Girn was the PMDE Program Development Officer on this research project. This study is based in part on data from Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services (provided by the Alberta Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Unit housed within Alberta Health Services), CIHI, Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS) and the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness (made available by Health Data Nova Scotia of Dalhousie University). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of the data custodians or data providers. Results are reprinted with permission from the CoLab Network and are also available in report form from the Canadian Drug Agency. Reference Randall, Luu and Vu50 Scott Klarenbach was supported by the Kidney Health Research Chair and the Division of Nephrology at the University of Alberta.

Author contributions

DS, LdL, MB, FA, SB and SK contributed to the study concept and design. HL prepared the draft protocol. JR, HM, DM, GC, DD and JLK facilitated data acquisition. KV, HM, SF and SM conducted the formal analyses. ZL and DM performed validation of analyses. HL, GC, CM, DD and JLK supervised and coordinated analyses. JR and KM created the tables and figures. KM prepared the draft manuscript. JR performed project administration. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. SK provided study supervision.

Funding statement

This work was supported by funding from Canada’s Drug Agency through the PMDE program to the University of Alberta, with SK as the principal investigator; PMDE is funded by Health Canada. The funders had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this manuscript: JR, HL, KV, KM, ZL and SK are members of the Alberta Real World Evidence Consortium (ARWEC) and the Alberta Drug and Therapeutic Evaluation Consortium (ADTEC); these entities (comprised of individuals from the University of Alberta, University of Calgary and Institutes of Health Economics) conduct research including investigator-initiated industry-funded studies (ARWEC) and government-funded studies (ADTEC). MB is a current employee at Pfizer Canada Inc. FA reports receiving research support paid to their institution from Eli Lilly, Allergan/AbbVie, Biohaven, Novartis, Teva and Lundbeck; consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Novartis, Teva, Lundbeck, ICEBM and Pfizer; and speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly, Novartis, Teva, Allergan/AbbVie, ICEBM, Aralez and Lundbeck. All other authors report no conflict. All authors of this study had complete autonomy over the content and submission of the manuscript, as well as the design and execution of the study.

Target article

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Inhibitor Use in 2018–2023: A Retrospective Cohort Study Across Six Canadian Provinces

Related commentaries (1)

Reviewer Comment on Randall et al. “Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Inhibitor Use in 2018–2023: A Retrospective Cohort Study Across Six Canadian Provinces”