1. Introduction

Starting from the work of Courant (Reference Courant1940), there has been significant interest in the dynamics of interconversions between soap film minimal surfaces triggered by boundary perturbations. These include Courant’s original paradigm of the interconversion between a Möbius strip and a disc, an example for which later work (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Moffatt, Pesci and Ricca2010, Reference Goldstein, McTavish, Moffatt and Pesci2014; Pesci et al. Reference Pesci, Goldstein, Alexander and Moffatt2015; Machon et al. Reference Machon, Alexander, Goldstein and Pesci2016) discovered that the topological rearrangement is associated with a singularity at the film’s boundary that involves reconnection of the associated surface Plateau border (SPB). Because, at least at its early stage, the dynamics of the instability involves a competition between inertial and capillary forces (Keller & Miksis Reference Keller and Miksis1983), the film motion is in the regime of high Reynolds number and is very rapid.

As a means of slowing down such topological rearrangements, we recently introduced (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Pesci, Raufaste and Shemilt2021; Raufaste et al. Reference Raufaste, Cox, Goldstein and Pesci2022) a version of the classical instability of a catenoidal soap film in which the rotational symmetry is broken by introducing a surface cutting the catenoid so that the motion involves SPBs moving along the surface, providing the bulk of the viscous dissipation. We use the terminology SPB in a broader sense than typically used in the foam literature to refer to the junction between a soap film and a (wetted) solid, which is sometimes termed a meniscus or contact line region. In that work, we found that the speed of the moving SPB was quantitatively consistent with a balance between capillary forces and viscous dissipation within the SPB (shown schematically in figure 2), obeying Bretherton’s law (Bretherton Reference Bretherton1961) in which the viscous force

![]() $f$

per unit length is

$f$

per unit length is

![]() $f=A\gamma \textit{Ca}^{2/3}$

, where

$f=A\gamma \textit{Ca}^{2/3}$

, where

![]() $A$

is a dimensionless constant,

$A$

is a dimensionless constant,

![]() $\gamma$

is the surface tension and the capillary number is

$\gamma$

is the surface tension and the capillary number is

![]() $\textit{Ca}=\mu v/\gamma$

, with

$\textit{Ca}=\mu v/\gamma$

, with

![]() $\mu$

the fluid viscosity and

$\mu$

the fluid viscosity and

![]() $v$

the SPB velocity.

$v$

the SPB velocity.

A simple configuration to study the migration of an SPB was proposed in section IV of Moffatt, Goldstein & Pesci (Reference Moffatt, Goldstein and Pesci2016). This involved placing a rod symmetrically along the axis of a catenoidal soap film suspended by two circular wires drawn slowly apart just beyond the separation of critical stability. The collapsing soap film then impacts the rod. and splits into two parts with SPBs propagating in opposite directions along the rod boundary. In the above paper, an estimate for the SPB velocity was obtained by dimensional analysis.

In the present paper, we refine this model in a manner that allows experimental realisation and control. We again do so in the context of a catenoid brought to its point of criticality, by introducing a coaxial central cylinder whose radius is chosen to correspond to the neck of the critical catenoid supported by the loop. We take advantage of the fact (Salkin et al. Reference Salkin, Schmit, Panizza and Courbin2014) that a soap film minimal surface connecting a circular support to a soap solution below is exactly a half-catenoid (figure 1

a). Thus, by slowly raising the supporting loop the film evolves through a continuum of stable half-catenoids with progressively smaller neck radii, until it reaches the critical state and touches the cylinder. Beyond the critical state, an SPB disconnects from the bath and moves upward under the action of the film’s surface tension and resisted by dissipation within the SPB, eventually rising to the level of the upper loop to form a stable minimal surface in the form of an annulus. This set-up therefore achieves a controlled interconversion between two minimal surfaces: the half-catenoid and the annular disk. The set-up considered here has similarities with the elegant work of Clerget et al. (Reference Clerget, Delvert, Courbin and Panizza2021) in which a hemispherical soap bubble on a surface slowly shrinks under the action of surface tension when air is allowed to escape through a hole in the surface. This quasi-static process can be understood quantitatively as a balance of the capillary force and the frictional force of the moving SPB. In contrast to the slow motion of the SPBs in those experiments, with time scales of

![]() $1{-}100\,$

s, the system we study here is intrinsically unstable throughout its entire evolution, which takes

$1{-}100\,$

s, the system we study here is intrinsically unstable throughout its entire evolution, which takes

![]() $\lesssim 0.2\,$

s. In the following, we describe a theoretical approach to this dynamical process based on balancing the capillary force of successive unstable minimal surfaces spanning the SPB and the wire loop with a frictional force for SPB motion. The derived evolution is compared with experimental results.

$\lesssim 0.2\,$

s. In the following, we describe a theoretical approach to this dynamical process based on balancing the capillary force of successive unstable minimal surfaces spanning the SPB and the wire loop with a frictional force for SPB motion. The derived evolution is compared with experimental results.

Figure 1. Experimental set-up. (a) A half-catenoid spanning a loop and a fluid bath and surrounding a cylinder whose radius equal the critical neck radius of the catenoid defined by the loop. (b) Schematic of set-up as the soap film retracts.

2. Theory and experimental verification

The geometry of the set-up is shown in figure 1(b): a wire loop of radius

![]() $R$

held at a distance less than

$R$

held at a distance less than

![]() $d_{\textit{max}}$

above a soap solution (

$d_{\textit{max}}$

above a soap solution (

![]() $d_{\textit{max}}=0.663R$

is the critical height of a half-catenoid) supports a soap film whose shape is the function

$d_{\textit{max}}=0.663R$

is the critical height of a half-catenoid) supports a soap film whose shape is the function

![]() $\zeta (z)$

surrounding a central cylinder of radius

$\zeta (z)$

surrounding a central cylinder of radius

![]() $r_0=0.553R$

, the corresponding critical neck radius. The initial condition of the surface is the critical half-catenoid where the contact line of the surface with the cylinder coincides with the surface of the bath. When the loop is moved beyond

$r_0=0.553R$

, the corresponding critical neck radius. The initial condition of the surface is the critical half-catenoid where the contact line of the surface with the cylinder coincides with the surface of the bath. When the loop is moved beyond

![]() $d_{\textit{max}}$

the SPB detaches from the bath and begins its motion up the cylinder.

$d_{\textit{max}}$

the SPB detaches from the bath and begins its motion up the cylinder.

While the motion of the soap film is a moving boundary problem in which the shape of the film is to be determined as part of the dynamics, we explore the simplest possibility, a quasistatic approximation in which, at every instant of time, the moving film is taken to be an (unstable) equilibrium catenoid that connects the present location of the SPB to the wire loop above. The motion is then governed by a balance between the film’s capillary force and the viscous drag within the moving SPB.

Figure 2. Geometry of Plateau borders for two topologically equivalent situations. (a) Relaxation of a half-catenoid. (b) Relaxation of a bubble with an embedded ring in a tube. (c) Pathway of smooth interconversion between (a) and (b).

We adopt a coordinate system with the origin on the plane of the loop, with positive

![]() $z$

downwards, as in figure 1(b). Let

$z$

downwards, as in figure 1(b). Let

![]() $d(t)$

be the time-dependent SPB location measured from the origin,

$d(t)$

be the time-dependent SPB location measured from the origin,

![]() $z=0$

. Under the quasistatic approximation the shape of the moving surface can be found by a standard analysis. The general form of the catenoid is

$z=0$

. Under the quasistatic approximation the shape of the moving surface can be found by a standard analysis. The general form of the catenoid is

where the constants

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $c$

are determined by the boundary conditions. These are

$c$

are determined by the boundary conditions. These are

![]() $\zeta (0)=R$

and, for all

$\zeta (0)=R$

and, for all

![]() $d\equiv d(t)\leqslant d_{{max}}$

,

$d\equiv d(t)\leqslant d_{{max}}$

,

![]() $\zeta (d)=r_0$

. We adopt a system of units made dimensionless with the loop radius

$\zeta (d)=r_0$

. We adopt a system of units made dimensionless with the loop radius

![]() $R$

and define

$R$

and define

and find from the boundary conditions the result

Writing the hyperbolic functions as exponentials and multiplying by

![]() $x=e^{D/\alpha }$

, this result can be recast as a quadratic equation for

$x=e^{D/\alpha }$

, this result can be recast as a quadratic equation for

![]() $x$

, whose two roots yield transcendental equations defining two branches of solution

$x$

, whose two roots yield transcendental equations defining two branches of solution

![]() $D_\pm (\alpha )$

$D_\pm (\alpha )$

\begin{align} D_\pm =\alpha \ln \left [\frac {\beta \pm \sqrt {\beta ^2-\alpha ^2}}{1-\sqrt {1-\alpha ^2}}\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} D_\pm =\alpha \ln \left [\frac {\beta \pm \sqrt {\beta ^2-\alpha ^2}}{1-\sqrt {1-\alpha ^2}}\right ]\!. \end{align}

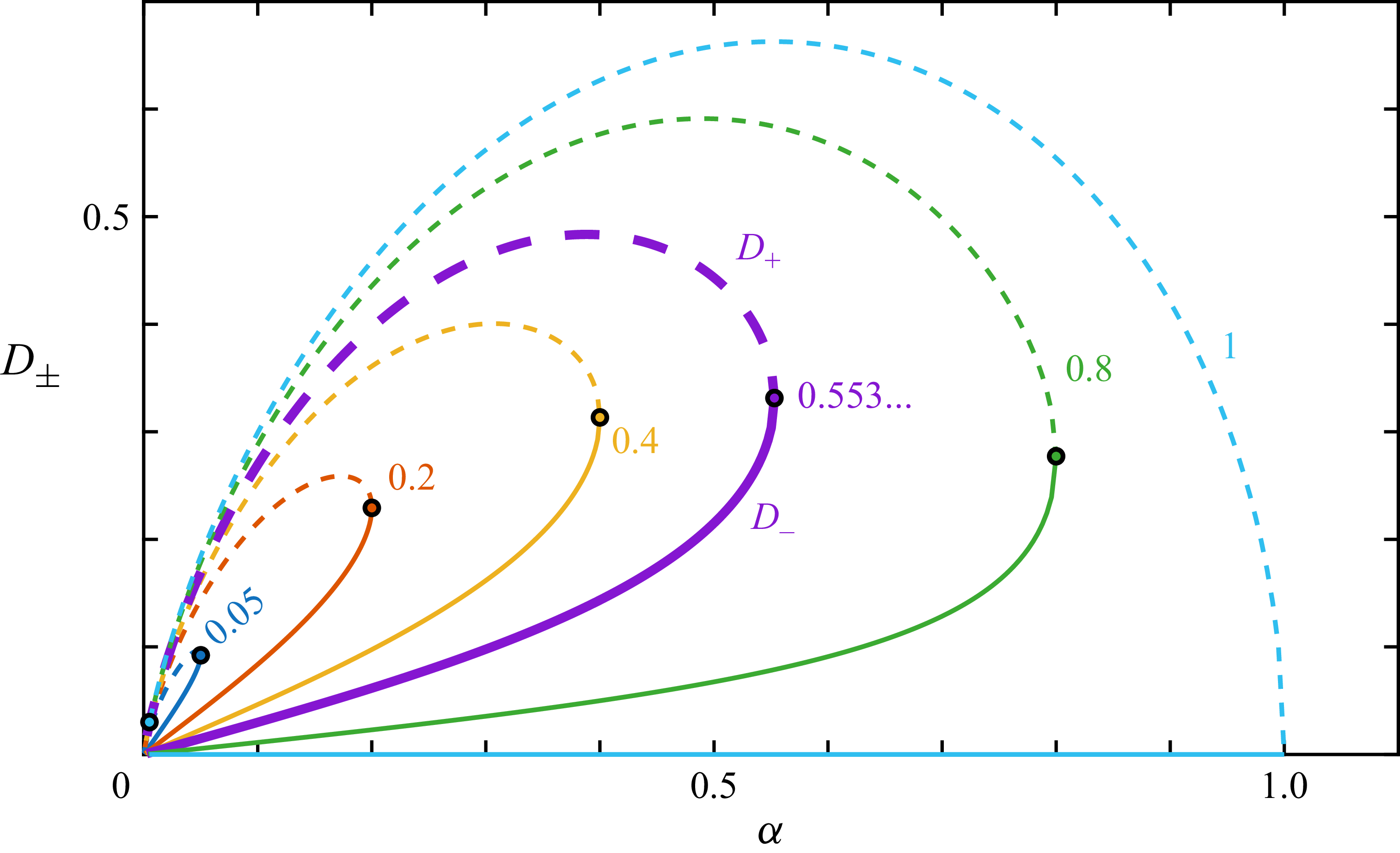

As shown in figure 3, these two branches combine to give a loop in the

![]() $\alpha D$

-plane. As in the treatment of a full catenoid spanning two identical loops (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Pesci, Raufaste and Shemilt2021), of the two branches

$\alpha D$

-plane. As in the treatment of a full catenoid spanning two identical loops (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Pesci, Raufaste and Shemilt2021), of the two branches

![]() $D_\pm$

one (

$D_\pm$

one (

![]() $D_-$

) is the physically attainable one because it is the one that minimises the area, while the other (

$D_-$

) is the physically attainable one because it is the one that minimises the area, while the other (

![]() $D_+$

) is a local maximum of the area. Hence, we choose the branch

$D_+$

) is a local maximum of the area. Hence, we choose the branch

![]() $D_-$

. The contact angle

$D_-$

. The contact angle

![]() $\theta$

at the SPB, defined to be

$\theta$

at the SPB, defined to be

![]() $0$

when the film is tangent to the cylinder as in figure 1(b), is given by

$0$

when the film is tangent to the cylinder as in figure 1(b), is given by

Figure 3. The two branches of solutions

![]() $D_\pm (\alpha )$

in (2.4) for various values of

$D_\pm (\alpha )$

in (2.4) for various values of

![]() $\beta$

. The physical branch

$\beta$

. The physical branch

![]() $D_-$

(solid) and unphysical branch

$D_-$

(solid) and unphysical branch

![]() $D_+$

(dashed) meet at the black circles. Heavy curve for critical size of inner cylinder.

$D_+$

(dashed) meet at the black circles. Heavy curve for critical size of inner cylinder.

The motion of the soap film arises from a balance between the capillary force

![]() $\gamma \cos \theta$

per unit length of SPB with

$\gamma \cos \theta$

per unit length of SPB with

![]() $\theta$

given by (2.5) and we set

$\theta$

given by (2.5) and we set

![]() $\gamma =2\sigma$

, with

$\gamma =2\sigma$

, with

![]() $\sigma$

the surface tension of each side of the soap film, and frictional forces that arise from flows within the Plateau border. The latter have been considered previously by Cantat, Kern & Delannay (Reference Cantat, Kern and Delannay2004), Cantat & Delannay (Reference Cantat and Delannay2005), Terriac, Etrillard & Cantat (Reference Terriac, Etrillard and Cantat2006) and Clerget et al. (Reference Clerget, Delvert, Courbin and Panizza2021), who noted in both steady-state and dynamical problems that Bretherton’s law holds. As shown in figure 2, the Plateau border problems of a moving bubble in a tube and the present situation are related by topological inversion. Thus we expect that, per unit length of the contact line between the film and the cylinder, there is a frictional force of the form previously used to describe the motion of bubbles attached to surfaces, with a general exponent

$\sigma$

the surface tension of each side of the soap film, and frictional forces that arise from flows within the Plateau border. The latter have been considered previously by Cantat, Kern & Delannay (Reference Cantat, Kern and Delannay2004), Cantat & Delannay (Reference Cantat and Delannay2005), Terriac, Etrillard & Cantat (Reference Terriac, Etrillard and Cantat2006) and Clerget et al. (Reference Clerget, Delvert, Courbin and Panizza2021), who noted in both steady-state and dynamical problems that Bretherton’s law holds. As shown in figure 2, the Plateau border problems of a moving bubble in a tube and the present situation are related by topological inversion. Thus we expect that, per unit length of the contact line between the film and the cylinder, there is a frictional force of the form previously used to describe the motion of bubbles attached to surfaces, with a general exponent

![]() $q$

$q$

where

![]() $A$

is a dimensionless constant and

$A$

is a dimensionless constant and

![]() $q=2/3$

corresponds to Bretherton’s law. We take

$q=2/3$

corresponds to Bretherton’s law. We take

![]() $A$

to be fixed as the geometry changes, while recognising that in a more detailed analysis there may be higher-order corrections as the angle

$A$

to be fixed as the geometry changes, while recognising that in a more detailed analysis there may be higher-order corrections as the angle

![]() $\theta$

evolves. For the case of interest (

$\theta$

evolves. For the case of interest (

![]() $q=2/3$

), we define a rescaled time

$q=2/3$

), we define a rescaled time

![]() $T=\gamma t/(\mu \textit{RA}^{1/q})$

, and making use of the relation

$T=\gamma t/(\mu \textit{RA}^{1/q})$

, and making use of the relation

![]() $\cos (\arctan (x))=1/\sqrt {1+x^2}$

, the scaled SPB position obeys the equation

$\cos (\arctan (x))=1/\sqrt {1+x^2}$

, the scaled SPB position obeys the equation

after some straightforward but lengthy algebra, and

![]() $\alpha (D)$

is given implicitly by (2.4). While it is possible to obtain an implicit solution for

$\alpha (D)$

is given implicitly by (2.4). While it is possible to obtain an implicit solution for

![]() $T(\alpha )$

in terms of hypergeometric functions for any power

$T(\alpha )$

in terms of hypergeometric functions for any power

![]() $q\leqslant 1$

, the result is not particularly illuminating and a numerical solution is straightforward. The function

$q\leqslant 1$

, the result is not particularly illuminating and a numerical solution is straightforward. The function

![]() $D(T)$

is shown in figure 3 for

$D(T)$

is shown in figure 3 for

![]() $q=2/3,1$

. At large

$q=2/3,1$

. At large

![]() $T$

, as

$T$

, as

![]() $D\to 0$

, its asymptotic behaviour, obtained from (2.4), is

$D\to 0$

, its asymptotic behaviour, obtained from (2.4), is

![]() $D=-\alpha \ln \beta + {\cdots}$

. Upon substitution into (2.7) one finds

$D=-\alpha \ln \beta + {\cdots}$

. Upon substitution into (2.7) one finds

![]() $D\sim T^{-2}$

when

$D\sim T^{-2}$

when

![]() $q=2/3$

, which contrasts strongly with exponential decay obtained when the frictional law is linear in the capillary number (

$q=2/3$

, which contrasts strongly with exponential decay obtained when the frictional law is linear in the capillary number (

![]() $q=1$

), as would be the case when there is no wetting layer with its associated flows.

$q=1$

), as would be the case when there is no wetting layer with its associated flows.

Figure 4. Time dependence of the SPB position in scaled coordinates. Data points (squares and circles) are from two distinct experimental sets, with error bars representing standard deviations. Blue line is the solution to (2.7) for

![]() $q=2/3$

, and red dashed line is for

$q=2/3$

, and red dashed line is for

![]() $q=1$

.

$q=1$

.

To test which power-law exponent

![]() $q$

governs the SPB motion, we employed an apparatus consisting of a

$q$

governs the SPB motion, we employed an apparatus consisting of a

![]() $50\,$

ml Falcon tube (diameter

$50\,$

ml Falcon tube (diameter

![]() $39\,$

mm) attached by its threaded end to a large plastic Petri dish (inner diameter

$39\,$

mm) attached by its threaded end to a large plastic Petri dish (inner diameter

![]() $135\,$

mm, height

$135\,$

mm, height

![]() $15\,$

mm). The upper loop supporting the soap film is a section of Tygon tubing (diameter

$15\,$

mm). The upper loop supporting the soap film is a section of Tygon tubing (diameter

![]() $8\,$

mm) attached to a shelf extending out from the bottom of a plastic cylinder that fits tightly around the Falcon tube and smoothly slides along it. The shelf is perforated in order to allow free circulation of air in and out of the half-catenoid region. The Petri dish was filled with a soap solution to

$8\,$

mm) attached to a shelf extending out from the bottom of a plastic cylinder that fits tightly around the Falcon tube and smoothly slides along it. The shelf is perforated in order to allow free circulation of air in and out of the half-catenoid region. The Petri dish was filled with a soap solution to

![]() ${\sim} 2\,$

mm below the top. The soap solution was a mixture of Fairy liquid detergent, glycerol and water using published proportions (recipe C in Lalli et al. (Reference Lalli, Shen, Dini and Giusti2023)).

${\sim} 2\,$

mm below the top. The soap solution was a mixture of Fairy liquid detergent, glycerol and water using published proportions (recipe C in Lalli et al. (Reference Lalli, Shen, Dini and Giusti2023)).

Videos of the meniscus motion were captured at

![]() $200\,$

frames sec–1 using a Phantom V641 high-speed camera equipped with a Zeiss macro lens (

$200\,$

frames sec–1 using a Phantom V641 high-speed camera equipped with a Zeiss macro lens (

![]() $f=60\,$

mm). The SPB motion was tracked by hand from those videos using Image J. Figure 4 shows the average data from two independent sessions, consisting respectively of

$f=60\,$

mm). The SPB motion was tracked by hand from those videos using Image J. Figure 4 shows the average data from two independent sessions, consisting respectively of

![]() $8$

and

$8$

and

![]() $10$

independent runs, plotted against the scaled time

$10$

independent runs, plotted against the scaled time

![]() $T$

from theory. At long times, the data clearly favour

$T$

from theory. At long times, the data clearly favour

![]() $q=2/3$

. The deviations visible at early times may arise from a breakdown of the quasi-static approximation when the film separates from the bath. Taking the value

$q=2/3$

. The deviations visible at early times may arise from a breakdown of the quasi-static approximation when the film separates from the bath. Taking the value

![]() $q=2/3$

, there is one free parameter to compare experiment and theory, the characteristic time

$q=2/3$

, there is one free parameter to compare experiment and theory, the characteristic time

![]() $\tau$

that maps the dimensional time

$\tau$

that maps the dimensional time

![]() $t$

to the scaled time

$t$

to the scaled time

![]() $T$

via

$T$

via

![]() $T=t/\tau$

, where

$T=t/\tau$

, where

![]() $\tau =RA^{3/2}\mu /\gamma$

. We find

$\tau =RA^{3/2}\mu /\gamma$

. We find

![]() $\tau =0.1{-}0.3\,$

s. Using

$\tau =0.1{-}0.3\,$

s. Using

![]() $R=4\,$

cm,

$R=4\,$

cm,

![]() $\mu =2\,$

cP and the estimated

$\mu =2\,$

cP and the estimated

![]() $\sigma =25\,$

dyn cm−1, we find

$\sigma =25\,$

dyn cm−1, we find

![]() $A=16{-}30$

, consistent in scale with previous observations by Cantat et al. (Reference Cantat, Kern and Delannay2004) and Clerget et al. (Reference Clerget, Delvert, Courbin and Panizza2021), who found values of

$A=16{-}30$

, consistent in scale with previous observations by Cantat et al. (Reference Cantat, Kern and Delannay2004) and Clerget et al. (Reference Clerget, Delvert, Courbin and Panizza2021), who found values of

![]() ${\sim} 40$

and suggested that the discrepancy between these values and the significantly smaller theoretical estimates of

${\sim} 40$

and suggested that the discrepancy between these values and the significantly smaller theoretical estimates of

![]() ${\sim} 10$

arises from the greater dissipation within the fluid due to the existence of rigid air–water interfaces arising from the presence of surfactants.

${\sim} 10$

arises from the greater dissipation within the fluid due to the existence of rigid air–water interfaces arising from the presence of surfactants.

The agreement between theory and experiment reported provides further validation of the applicability of Bretherton’s law to the motion of Plateau borders, and also shows the validity of force estimates obtained from the geometry of unstable minimal surfaces. This therefore suggests a pathway forward in the quantitative description of more complex topological rearrangements of soap films (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, McTavish, Moffatt and Pesci2014) in which the Plateau border undergoes a reconnection at the moment of singularity (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Moffatt, Pesci and Ricca2010).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to N. Lalli and C. Raufaste for discussions. R.E.G. and A.I.P. acknowledge support from the Complex Systems Fund.

Declaration of interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.