This corrigendum corrects errors in the published version of our article “When the Money Stops: Fluctuations in Financial Remittances and Incumbent Approval in Central Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia” (Tertytchnaya et al. Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). After reviewing our code, we discovered an error involving the creation of one of the three datasets used in the article, based on the Life in Kyrgyzstan Panel Survey, 2010–2013. To merge individuals across waves, we used individuals’ wave specific identifiers, when we should have used respondents’ unique panel identifier, available in a separate document, the “mroster1013.” There are 54 remittance recipients in our analysis for whom wave identifiers change due to marriage, death in family, divorce, etc. As a result, merging across waves was not done properly, nor were the variables that are based on changes from one wave to the next constructed correctly.

We conducted a full audit from the original source files used to construct the dataset and subsequently identified additional errors affecting two variables. First, while reconstructing the Change in Trust in the President t-(t-1), variable, we discovered an error in how this item was constructed for 2013. In the 2010, 2011 and 2012 waves of the Life in Kyrgyzstan Panel Survey, respondents were asked how much they generally trust the “President / Central government officials” of Kyrgyzstan. In the 2013 wave, however, the question was split into two: respondents were separately asked how much they generally trust the president and the government. To be consistent with the 2010–2012 waves, in 2013 we take the average response of respondents to these two questions rather than relying on only one. Second, for one of our controls, we discovered that we erroneously used respondents’ satisfaction with household income as a proxy for life satisfaction while we should have used satisfaction with household living standard. As Tables E.1–4 in the revised supporting information document show, these changes do not significantly alter our results.

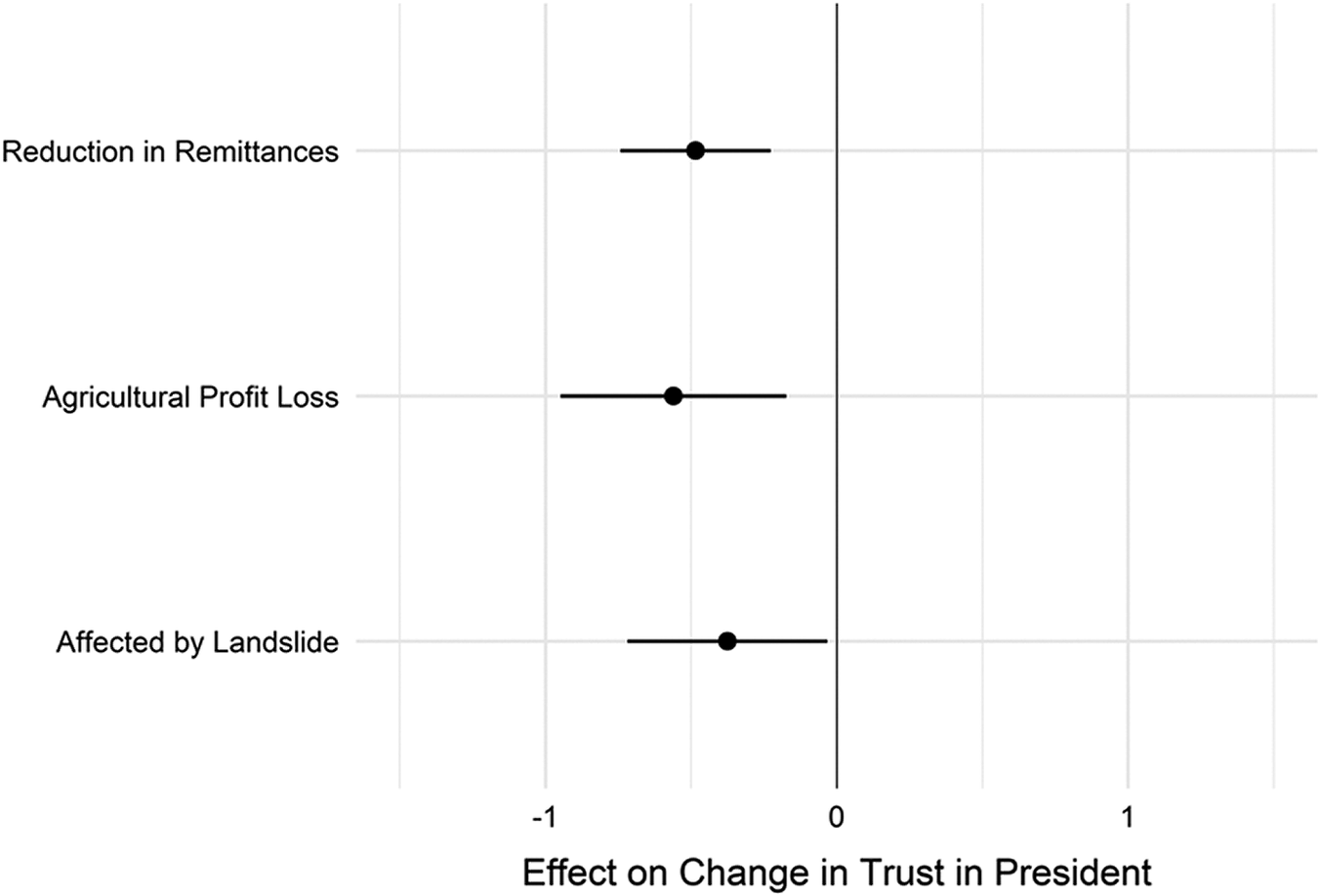

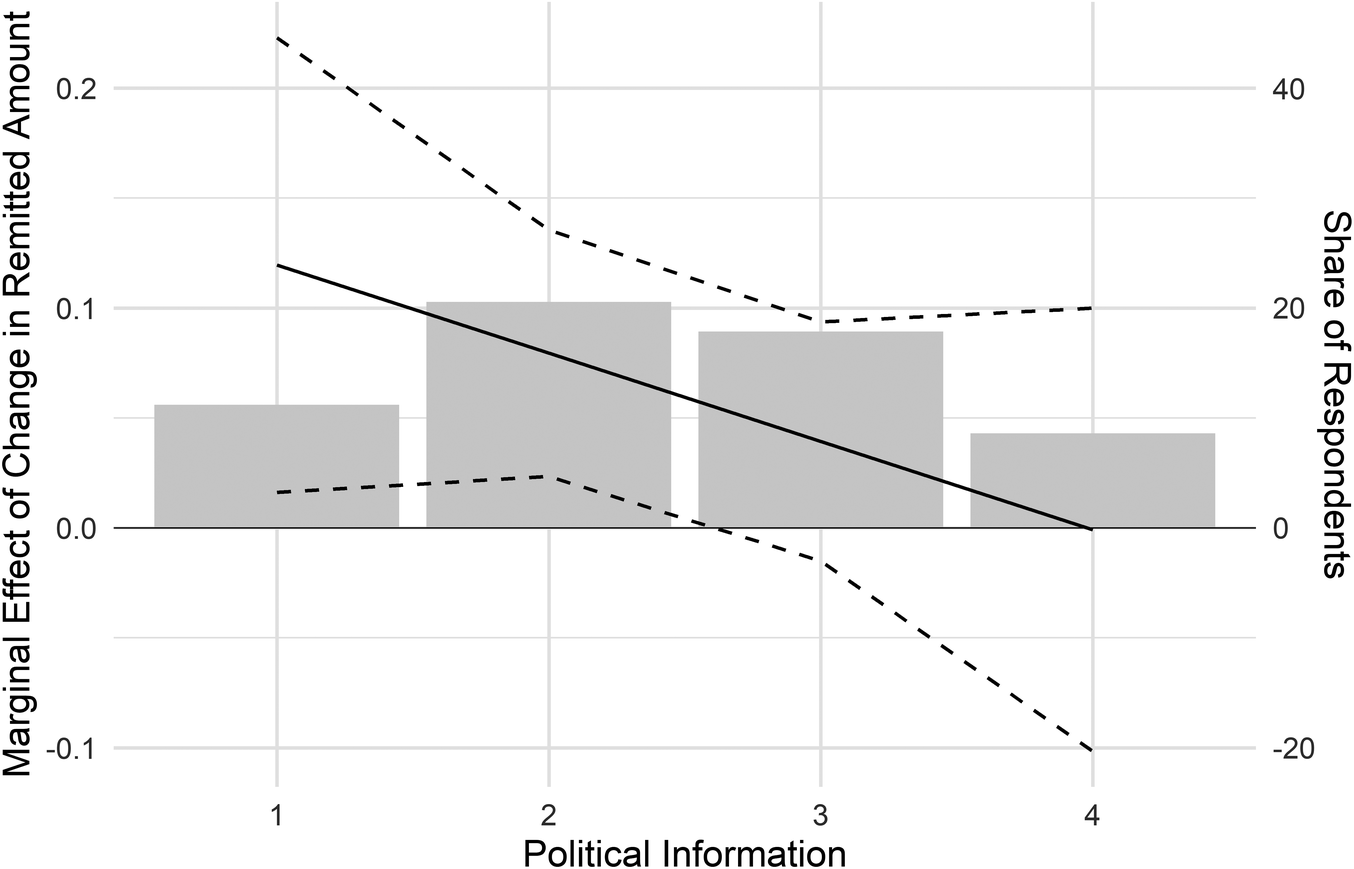

In the revised Tables 2–3 and Figures 3 and 4 we present the corrected estimates. Resolving the errors did not substantively change our findings or conclusions. The general results pertaining to our variables of interest, changes in remittances, remain consistent with those reported in the article, except for Model 3, Tables 2–3 where the coefficient of the variable of interest, Changes in the Remittances Index, fails to reach statistical significance (p=.166). We also noticed a discrepancy in the description of the coding of the reduction in remittances item used in Figure 3. On page 765 of our article, it states that “this variable takes on a value of 1 when respondents experienced a reduction in the amount and/or frequency of remitted income”, this should read “this variable takes on a value of 1 when respondents experienced a reduction in the amount and frequency of remitted income, and 0 otherwise.”

Revised Tables 2–3. Changes in Remittances, Changes in Trust in the President and Concern about Personal Economic Situation, Kyrgyzstan panel data

Notes: Models 1 through 3 present regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses based on a panel GLS estimation with random effects varying across individuals and household and wave fixed effects. Being illiterate is the reference category for education. For full results see Table E.1 of the revised SI and for robustness checks see Tables C.4-C.7 and E.2-3. Significant at the ∗∗∗ p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗ p ≤ 0.05, ∗ p ≤ 0.10 level. Source: Life in Kyrgyzstan Panel Survey, 2010–2013.

Revised Figure 3. The effect of household shocks on Trust in the President

Notes: The figure presents regression coefficients and 95 percent confidence intervals based on a panel GLS estimation with random effects varying across individuals and household and wave fixed effects. Full results are reported in Table B.2 of the revised SI and robustness checks in Tables C.8-C.10 and E.4. Source: Life in Kyrgyzstan Panel Survey, 2010–2013.

Revised Figure 4. The effect on Changes in Remittances on Changes in Trust in the President by access to Political Information

Notes: The figure presents the marginal effect of changes in the amount of remittances on changes in trust in the president at different levels of access to political information with 95 percent confidence intervals based on a panel GLS estimation with random effects varying across individuals and household and wave fixed effects. For full results see Table B.3 and for robustness checks see Table C.15 and Figure C.1 in the revised SI. Source: Life in Kyrgyzstan Panel Survey, 2010–2013.

The Life in Kyrgyzstan Panel Survey was one of three surveys used in our article. The results based on the other two surveys reported in Tables 1 and 4, and Figures 1 and 2 are unchanged. The overall conclusion based on the Life in Kyrgyzstan panel data was that when people experience a decrease (increase) in remittances, they become less (more) satisfied about their household economic situation and misattribute responsibility to the incumbent at home. None of the corrections contradict these findings. Nonetheless, we deeply regret these errors.

All data and materials required to verify the reproducibility of the revised merging, coding and analyses have been posted to the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MO3KOQ.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420001033.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.