1. Introduction

In today’s globalised society, the use of more than one language is increasingly common. For example, recent estimates indicate that over one-fifth of London residents and nearly 60% of Europeans report speaking at least one language in addition to their home tongue (Office for National Statistics, 2022). This widespread engagement with multiple languages, especially among younger populations, has fuelled growing interest in how varying degrees of multilingual experience may influence cognitive functions (e.g., Filippi et al., Reference Filippi, Periche-Tomas, Papageorgiou, Bairaktari, Bright and Kadosh2024). One area that has received substantial attention is executive functioning (EF), particularly inhibitory control (IC), that is, the ability to regulate attention and suppress automatic or prepotent responses. In this context, multilingual language use has been hypothesised to offer regular opportunities to engage IC mechanisms, particularly during language selection and suppression. A number of studies have reported a potential bilingual advantage in terms of cognitive control (e.g., Poarch & Bialystok, Reference Poarch and Bialystok2015); other research has yielded null results (e.g., Paap et al., Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2015), while others have identified conditional or task-specific patterns (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013; Ware et al., Reference Ware, Kirkovski and Lum2020).

Though IC remains a widely studied domain, research has predominantly focused on externally driven behavioural inhibition. However, IC also plays a critical role in the regulation of internally generated thoughts that may arise during cognitive tasks or in everyday situations. Surprisingly, there is limited evidence regarding the relationship between bilingualism and mind wandering (MW), a frequent and natural phenomenon in daily life, characterised by the tendency for attention to drift away from the “here and now” towards task- or stimulus-unrelated thoughts. MW is related to, but distinct from, cognitive control and is influenced by various individual differences, which may also include multilingual experience, the central focus of the present study.

1.1. Mind wandering, cognitive control and multilingualism

MW is a common experience, occurring during approximately 30% to 50% of waking hours (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Gross, Chun, Smeekens, Meier, Silvia and Kwapil2017; Killingsworth & Gilbert, Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert2010). It has been associated with both costs, such as reduced reading comprehension (Bonifacci et al., Reference Bonifacci, Colombini, Marzocchi, Tobia and Desideri2022), academic self-concept (Desideri et al., Reference Desideri, Ottaviani, Cecchetto and Bonifacci2019) and lower mood (Smallwood & O’Connor, Reference Smallwood and O’Connor2011) and potential benefits, including enhanced creativity and future planning (Baird et al., Reference Baird, Smallwood, Mrazek, Kam, Franklin and Schooler2012; Mooneyham & Schooler, Reference Mooneyham and Schooler2013). Importantly, MW is not a monolithic phenomenon but is better understood through a family-resemblances framework (Seli et al., Reference Seli, Kane, Smallwood, Schacter, Maillet, Schooler and Smilek2018), which conceptualises it as a natural category with graded membership.

The most commonly accepted definitions of MW emphasise unintentional mind wandering (UMW), typically operationalised as either task-unrelated thought (i.e., thought disengaged from one’s primary task) and/or stimulus-independent thought (i.e., thought decoupled from perceptual input; Smallwood & Schooler, Reference Smallwood and Schooler2006, Reference Smallwood and Schooler2015). UMW is often indicative of lapses in attention, particularly when cognitive demands are high or in situations requiring sustained focus (Seli et al., Reference Seli, Beaty, Marty-Dugas and Smilek2019). However, there is also evidence supporting the existence of intentional mind wandering (IMW) (Robison & Unsworth, Reference Robison and Unsworth2018), which may serve as a strategic response to failure or boredom (Wen et al., Reference Wen, Soffer‐Dudek and Somer2024), or function as a coping mechanism and means of escaping stress (Seli et al., Reference Seli, Beaty, Marty-Dugas and Smilek2019). In addition, a third important dimension of MW is meta-awareness, that is, the capacity to recognise one’s own MW episodes, which was found to be a distinct component from intentional MW (Seli et al., Reference Seli, Ralph, Risko, Schooler, Schacter and Smilek2017). Research suggests that individuals with greater meta-awareness are better able to regulate and utilise their wandering thoughts for beneficial outcomes (Seli et al., Reference Seli, Ralph, Risko, Schooler, Schacter and Smilek2017).

To summarise, MW encompasses a wide range of experiences that vary in content, intentionality and the relationship between mental activity and external stimuli (Seli et al., Reference Seli, Kane, Smallwood, Schacter, Maillet, Schooler and Smilek2018). These components reflect underlying differences in cognitive control and metacognitive monitoring and may be differentially sensitive to individual variation in cognitive engagement and attentional regulation. According to the decoupling hypothesis (Smallwood & Schooler, Reference Smallwood and Schooler2006), decreased performance during MW occurs primarily because attention becomes decoupled from the task at hand and instead coupled to task- or stimulus-unrelated thoughts. Individuals with stronger executive control are generally better at maintaining task focus and suppressing irrelevant thoughts, leading to a reduced frequency of UMW and more effective engagement in IMW. This suggests that deliberate engagement with internal thoughts requires sufficient IC and working memory capacity (e.g., McVay & Kane, Reference McVay and Kane2009). However, as Irving et al. (Reference Irving, Glasser, Gopnik, Pinter and Sripada2020) argue, a defining feature of MW is its dynamic nature, through which thoughts unfold and shift over time. In line with this, Wong et al. (Reference Wong, Willoughby and Machado2022) emphasise the role of cognitive flexibility, suggesting that MW should be understood as a cognitive switching process between external task demands and internal thought processes.

Although various components of attentional control, such as switching/flexibility, inhibition and working memory, are clearly implicated in MW, it is also dynamically influenced by emotional factors, individual task-related skills and task characteristics, as proposed in the swing effect model from the meta-analysis by Bonifacci et al. (Reference Bonifacci, Viroli, Vassura, Colombini and Desideri2023). Finally, Kane et al. (Reference Kane, Gross, Chun, Smeekens, Meier, Silvia and Kwapil2017) highlights that MW in everyday environments and task-unrelated thoughts (TUTs) during controlled laboratory settings may have distinct correlates, underscoring the need for more context-sensitive investigations.

This brief overview of MW provides the conceptual basis for exploring how multilingualism may serve as a source of individual differences worthy of investigation in relation to MW. From a theoretical standpoint, the possible link between multilingualism and MW is compelling. Managing multiple languages involves regular attentional control, that is, switching, monitoring and inhibiting competing linguistic representations, which could extend to internally generated cognition. However, previous research has yielded mixed findings regarding the debated bilingual advantage in executive functions (e.g., Paap et al., Reference Paap, Johnson and Sawi2015; Lehtonen et al., Reference Lehtonen, Soveri, Laine, Järvenpää, de Bruin and Antfolk2018; van den Noort et al., Reference van den Noort, Struys, Bosch, Jaswetz, Perriard, Yeo, Barisch, Vermeire, Lee and Lim2019), with particularly inconsistent evidence in the domain of response inhibition. In contrast, multilingualism may exert a more consistent influence on internally directed cognitive processes, such as the regulation of MW. Importantly, multilingualism is not merely a cognitive condition but a lived, socially embedded experience. As highlighted by Poarch and Krott (Reference Poarch and Krott2019), multilingual experience can positively affect perspective-taking in conversational contexts (Schroeder, Reference Schroeder2018), creative and divergent thinking (Kharkhurin, Reference Kharkhurin2009), open-mindedness and tolerance of ambiguity, as well as cultural empathy (Dewaele & Wei, Reference Dewaele and Wei2013). This broader view shifts the focus from a purely cognitive interpretation of the bilingual advantage to a more nuanced and ecological perspective, which considers the multifaceted and dimensional nature of multilingual experience.

From this standpoint, investigating MW in multilingual individuals becomes particularly relevant, as the ability to flexibly regulate internal thought may be influenced by a general predisposition to switch between internal states (e.g., selecting which language to activate) and external demands (e.g., adapting to the interlocutor’s language). Such flexibility may enhance the regulation of the dynamic structure of MW, aligning with broader executive and metacognitive functions shaped by multilingual experience.

Yet, empirical evidence on this relationship is sparse. One notable study (Shulley & Shake, Reference Shulley and Shake2016) found no differences in MW between bilingual and monolingual students during cognitive tasks, but it relied on categorical classification and did not examine degrees of multilingual engagement or meta-awareness. Moreover, it used probe-based measures, which may not capture stable, trait-like patterns of daily MW.

1.2. The present study

Building on prior research linking multilingual experience with aspects of executive and attentional control, the present study aimed to examine whether individual differences in multilingual proficiency and use, as measured by the multilingual proficiency index, predict performance in externally and internally directed attention regulation. Specifically, we investigated whether multilingual engagement is related to behavioural inhibition and MW processes, including both the frequency and awareness of internally generated thoughts. On this basis, we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Higher scores on the multilingual proficiency index would not significantly predict commission error rates on the Go/No-Go task, indicating no clear association between multilingual proficiency and externally driven IC.

Hypothesis 2: Higher multilingual proficiency scores would be associated with lower levels of unintentional and intentional mind wandering, reflecting better regulation of internally generated cognitive states.

Hypothesis 3: Higher multilingual proficiency scores would be associated with greater meta-awareness of mind wandering (MAMW), reflecting enhanced metacognitive monitoring of attention.

This study aims to contribute to an emerging research direction that seeks to understand how multilingual engagement might shape attentional dynamics beyond traditional EF paradigms. If multilingualism is associated with reduced unintentional or intentional MW, it could suggest novel mechanisms through which language experience supports everyday attentional regulation, with implications for educational contexts and populations at risk of attentional dysregulation. The present study adopts a dimensional approach to multilingualism using a multilingual proficiency index, which integrates self-rated proficiency and daily use of non-native languages. This method avoids binary classifications and enables a more refined analysis of how language background relates to IC and MW. IC was assessed with a Go/No-Go task measuring response inhibition, while MW was evaluated using the Brief Mind Wandering Three-Factor Scale (BMW-3; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Frischkorn, Sadus, Welhaf, Kane and Rummel2024), which captures trait-level tendencies across intentional MW, unintentional MW and meta-awareness.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Sixty-five university students (48 female, 17 male) participated in the study. Ages ranged from 18 to 34 years (M = 21.4, SD = 3.1). Participants were recruited via departmental mailing lists and social media platforms targeting students at UK universities. All participants reported having normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. All participants were multilingual, reporting use of at least one additional language beyond their first (L1). The most common L1s were Mandarin, English and Cantonese, and participants reported proficiency in a range of additional languages, including Urdu, Ilonggo, Japanese and Portuguese. The participants’ demographic, educational and linguistic background is summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Participation was voluntary, and all participants gave informed consent prior to beginning the study. The project received ethical approval from the UCL Research Ethics Committee.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and educational background of participants

Note: M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2. Self-reported language background and language use of participants

Note: M = mean; SD = standard deviation; AoA = age of acquisition.

2.2. Design

This study adopted a correlational design to investigate whether individual differences in multilingual proficiency and use predicted variation in IC and MW. The independent variable was the multilingual proficiency index, and the dependent variables were the commission error rate on a Go/No-Go task (IC) and the three BMW-3 subscale scores (unintentional MW, intentional MW and meta-awareness).

2.3. Materials

All questionnaires and the behavioural task in this study were programmed and administered online using PsyToolkit (Stoet, Reference Stoet2010, Reference Stoet2017).

2.4. Language experience questionnaire

A language background questionnaire adapted from Filippi et al. (Reference Filippi, Leech, Thomas, Green and Dick2012) was used to collect information on participants’ demographics, educational background, language history and socioeconomic status (SES). Participants listed up to five spoken languages and rated their proficiency in each non-native language across four domains: speaking, reading, writing and understanding. The items were presented using a 1–7 Likert scale; however, responses were exported by PsyToolkit using a 0–6 coding scheme (0 = no ability; 6 = native-like ability), and all analyses were conducted using this 0–6 coding. This difference reflects a shift in scale origin only and preserves the full response range without altering the underlying measurement. Proficiency ratings across the four domains were averaged for each language to yield a composite language proficiency score. Participants also reported their average daily use (in hours) of each language over the previous month. These data were used to derive a composite index of multilingual engagement, as described in the following section.

2.5. Language experience assessment

Multilingual experience was assessed using a study-specific composite index developed for this project. The measure focused exclusively on non-native languages (L2–L5), as the cognitive demands associated with multilingualism arise from the management and use of additional languages rather than from proficiency in the native language, which is typically automatised. Excluding the L1, therefore, avoids inflating scores and preserves meaningful variation in active multilingual engagement.

For each non-native language, participants provided self-rated proficiency across four domains: speaking, reading, writing and understanding. All proficiency values were analysed using the 0–6 coding described above. To minimise the influence of extreme or implausible values and to ensure comparability across languages, daily usage was recoded into a 0–4 ordinal scale: 0 = no use; 1 = >0–2 hours; 2 = >2–5 hours; 3 = >5–8 hours and 4 = >8 hours.

A per-language multilingual experience score was obtained by multiplying the mean proficiency score by the corresponding daily-use code, capturing both competence and frequency of engagement. The overall multilingual experience index was computed by summing the weighted proficiency–use values across all non-native languages reported by each participant. This total was then divided by four (the maximum number of non-native languages in the questionnaire) to normalise the index to a comparable scale for all participants, regardless of how many non-native languages they spoke. It provides a continuous, functionally oriented representation of multilingual engagement that captures the complexity of real-world language experience more effectively than binary classifications (e.g., bilingual versus monolingual).

2.6. Go/no-go task

The Go/No-Go task was used to assess IC. On each trial, a single letter appeared on screen. Participants were instructed to press the spacebar for four Go letters (A, V, W or Y) and withhold responses for one No-Go letter (X). The task comprised 170 trials total: 20 practice trials with feedback indicating whether responses were correct, followed by 150 experimental trials without feedback. Go and No-Go stimuli were pseudo-randomly presented in an 80%/20% ratio. Each letter was displayed for 500 ms, followed by a 1000 ms inter-stimulus interval (ISI). The main outcome measure was the commission error rate, calculated as the proportion of No-Go trials in which participants incorrectly pressed the key. Higher error rates indicated weaker IC. Reaction times were automatically recorded by the PsyToolkit platform but were not analysed, as timing precision in online environments is generally less reliable than in controlled laboratory conditions. In addition, the commission-error rate is the most widely accepted and theoretically grounded indicator of response inhibition in Go/No-Go tasks (Simmonds et al., Reference Simmonds, Pekar and Mostofsky2008).

2.7. Mind wandering questionnaire

MW was assessed using the Brief Mind-Wandering three-factor scale (BMW-3; Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Frischkorn, Sadus, Welhaf, Kane and Rummel2024), a validated self-report instrument designed to capture stable individual differences in the frequency and nature of task-unrelated thought. The scale comprises three subscales measuring: (1) UMW, reflecting spontaneous attentional lapses occurring without awareness; (2) IMW, referring to deliberately initiated task-unrelated thought; and (3) MAMW, indexing individuals’ monitoring and awareness of their own MW episodes. Each subscale consists of four items. Items were presented on a 5-point response scale coded 0–4 (0 = fully disagree; 1 = somewhat disagree; 2 = neutral; 3 = somewhat agree; 4 = fully agree). Subscale scores were calculated by summing the four items within each factor, resulting in a possible range of 0–16, with higher scores indicating greater levels of the corresponding MW dimension. The BMW-3 has demonstrated strong internal reliability and construct validity in previous research (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Frischkorn, Sadus, Welhaf, Kane and Rummel2024).

2.8. Procedure

Participants accessed the study by clicking a link distributed via the Research Participant Pool, WhatsApp or WeChat. The link redirected them to PsyToolkit (Stoet, Reference Stoet2010, Reference Stoet2017), where the full study was administered. After providing informed consent, participants completed basic biographical information, including age, gender, ethnicity and educational background. To reduce potential fatigue effects on behavioural performance, the Go/No-Go task was then administered immediately, beginning with a 20-trial practice block (with feedback) followed by 150 experimental trials (without feedback). After completing the task, participants continued with the remaining sections of the Language Experience Questionnaire, followed by the BMW-3. The entire study took approximately 15–30 minutes to complete. There were no forced response questions, and participants could leave at any point.

2.9. Data analysis

All data were processed and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 30). Four separate hierarchical regression models were conducted to test the hypotheses, corresponding to commission error rate, UMW, IMW and MAMW as dependent variables. Given the focused, hypothesis-driven nature of the study and the theoretical interrelatedness of the outcome measures, no formal correction for multiple comparisons was applied. This approach follows recommendations that correction procedures are unnecessary for planned analyses addressing distinct yet conceptually related hypotheses (Perneger, Reference Perneger1998; Rothman, Reference Rothman1990).

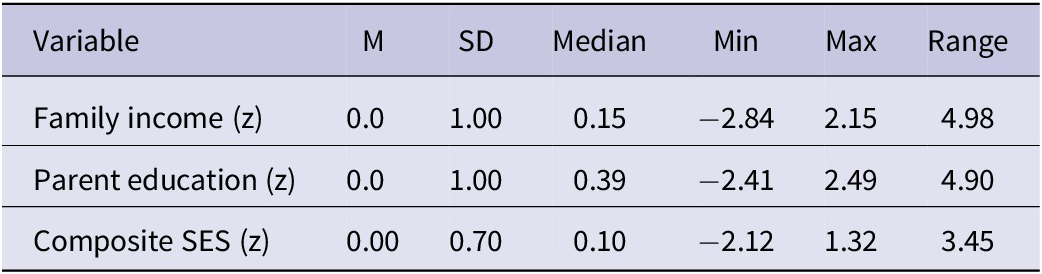

SES was used as a control variable and computed as the mean of standardised parental education (average of mother’s and father’s education level) and standardised household income (see Table 3). All components were z-scored before averaging to ensure equal weighting. Higher SES scores indicated relatively higher SES than the sample average, whereas negative scores reflected relatively lower SES (see Table 4).

Table 3. Distribution of parental education and household income levels

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for standardised SES variables

Note: Z-scores were computed within the current sample (M = 0, SD = 1 by design).

2.10. Statistical analyses

First, descriptive statistics were used to summarise the distribution of major variables, including the multilingual proficiency index, the commission error rate in the Go/No-Go task, MW scores (UMW, MAMW and IMW) and the control variable SES. The dataset was then screened for missing data, outliers, and violations of statistical assumptions. Due to the medium sample size (n = 65), the normality of continuous variables was assessed using Shapiro–Wilk tests, histograms and Q–Q plots. Assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity and normality of residuals were examined through standardised residual scatterplots and Q–Q plots of regression residuals.

Bivariate relationships among variables were explored using Pearson correlation analyses. Hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the predictive role of the multilingual proficiency index on IC and MW, respectively. In the first step of each model, the index was entered alone to assess its zero-order predictive effect. In the second step, SES was included as a control variable to determine whether proficiency scores uniquely predicted the outcome variables above and beyond individual socioeconomic differences. All statistical tests were conducted using a two-tailed alpha level of .05, and results were considered statistically significant at p < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for all key variables are summarised to provide an overview of the sample (see Table 5). There was no missing data for any variables (n = 65). The mean score for the multilingual proficiency index was 3.88 (M = 3.88, SD = 2.44), with values ranging from .50 to 10.75. The mean commission error rate was .26 (M = .26, SD = .19). MW was assessed using three subscales: the mean UMW score was 8.26 (M = 8.26, SD = 3.24), the mean MAMW score was 9.95 (M = 9.95, SD = 3.49) and the mean IMW score was 9.09 (M = 9.09, SD = 3.77). SES had a mean of .00 (M = .00, SD = .70), with values ranging from −2.12 to 1.32.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for key variables

a Summed subscale score.

3.2. Assumption checks for normality, linearity and homoscedasticity

To assess the suitability of the data for correlation analysis and linear regression, assumption checks were conducted. The Shapiro–Wilk statistics indicated significant departures from normality for multilingual proficiency, W = 0.90, p < .001, and for the commission error rate, W = 0.94, p = .005. All three MW scales were non-significant (all p > .05), supporting normality. Diagnostic checks based on standardised residual plots revealed no curvilinear trends and no funnel-shaped patterns, indicating that the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity were satisfied. Given the moderate sample size and the robustness of ordinary-least-squares regression to minor violations, no data transformations or non-parametric alternatives were required.

3.3. Correlational analyses

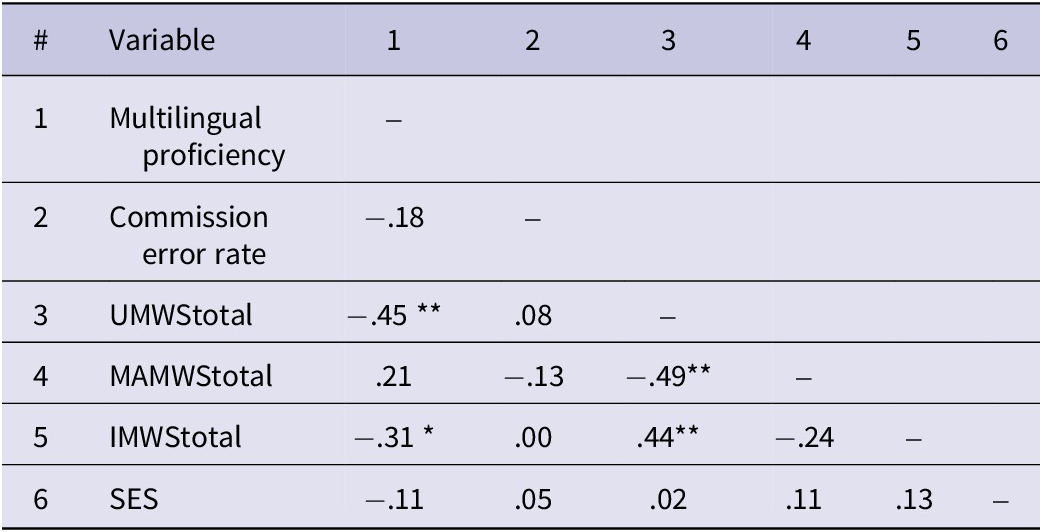

Pearson correlations (see Table 6) showed that greater multilingual experience was moderately associated with lower scores on both UMW, r(63) = −.45, p < .001, and IMW, r(63) = −.31, p = .014. The correlation between proficiency scores and MAMW was small and not significant, r(63) = .21, p = .099, and the multilingual proficiency index was unrelated to commission error rate, r(63) = −.18, p = .161. SES showed no meaningful association with any cognitive measure (all |r| ≤ .13, all p ≥ .286). Although some variables deviated mildly from normality, Pearson’s r is robust in samples of this size, so no rank-based alternative was required. As expected, the multilingual proficiency index was positively associated with established indicators of multilingual experience, such as the number of non-native languages (see supplementary materials, Table S1), supporting its convergent validity.

Table 6. Pearson correlations among variables (N = 65)

Note: UMWS = Unintentional Mind Wandering; MAMWS = Meta-Awareness of Mind Wandering; IMWS = Intentional Mind Wandering; SES = socioeconomic status. Values are Pearson’s r.

*p < .05. ** p < .01 (two-tailed).

3.4. Regression analyses

Hierarchical regressions (Step 1 = multilingual index, Step 2 = SES; N = 65) showed that multilingual proficiency did not predict response-inhibition accuracy: for commission error rate, Step 1 explained 3% of the variance (R 2 = .03), and the multilingual proficiency index was non-significant (β = −.17, p = .161); adding SES left the model unchanged (ΔR 2 < .01, SES β = .03, p = .818). By contrast, the multilingual index was a strong negative predictor of UMW: Step 1 accounted for 20% of the variance (R 2 = .20), with the multilingual index showing a significant effect (β = −.46, p < .001); introducing SES produced a trivial, non-significant increment (ΔR 2 = .01, SES β = −.03, p = .797). A similar, though smaller, effect emerged for IMW: Step 1 R 2 = .09, multilingual index β = −.29, p = .018; Step 2 ΔR 2 = .01, SES β = .10, p = .408. Finally, the multilingual proficiency index did not relate reliably to MAMW: Step 1 R 2 = .04, β = .22, p = .079; adding SES produced a non-significant model (R 2 = .06, SES β = .13, p = .294). In short, greater multilingual experience uniquely predicts lower unintentional and, to a lesser extent, IMW, but neither meta-awareness nor IC, and SES contributes no additional explanatory power in any model (see Table 7).

Table 7. Summary of regression coefficients and significant and non-significant effects

Note: N = 65. UMW = Unintentional Mind Wandering; IMW = Intentional Mind Wandering; MAMW = Meta-Awareness of Mind Wandering.

3.5. Validation of multilingualism measures

To examine whether the observed effects reflected general patterns of multilingual experience rather than properties of the composite index alone, we computed correlations between each multilingualism component (L2 proficiency, daily use and number of non-native languages) and the cognitive outcomes (UMW, IMW, MAMW and commission errors). As shown in the Supplementary Material (see Table S1), all three components showed negative correlations with UMW, and small negative trends with IMW, consistent with the pattern observed for the composite index. Correlations with meta-awareness were positive but small, and none of the multilingualism components were associated with commission errors.

This convergent pattern indicates that the main findings are consistent across the specific operationalisation of multilingualism: the associations with MW outcomes reflect shared variance captured across multiple aspects of multilingual experience. We, therefore, retained the composite index as the primary predictor in the main analyses, as it provides an integrated and theoretically coherent measure of multilingual engagement.

These results demonstrate that the effects observed in the main analyses are not driven solely by daily language use or by the mere number of languages spoken, and that proficiency-related mechanisms account for the relationship between multilingual experience and MW tendencies. To facilitate interpretation, Figure 1 illustrates the predicted effects of the multilingual proficiency index on both unintentional mind wandering (UMW; Panel A) and intentional mind wandering (IMW; Panel B). In both models, higher multilingual proficiency was associated with lower predicted levels of MW.

Figure 1. Predicted effects of the multilingual proficiency index on MW. Panel A shows predicted unintentional mind wandering (UMW; BMW-3), and Panel B shows predicted intentional mind wandering (IMW; BMW-3). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

This study examined whether individual differences in multilingual proficiency and use predict performance in response inhibition and MW.

We proposed three hypotheses: (1) that multilingual proficiency would not significantly predict commission error rates, reflecting no clear association with externally driven IC; (2) that multilingual proficiency would be associated with reduced unintentional and intentional mind wandering; and (3) that multilingual proficiency would be associated with greater meta-awareness, indicating enhanced metacognitive monitoring of attention.

4.1. Response inhibition

As predicted, multilingual proficiency did not significantly predict commission errors in the Go/No-Go task. The null effect of multilingual experience on response inhibition contrasts with Thanissery et al. (Reference Thanissery, Parihar and Kar2020), who found a bilingual advantage in young adults. Several methodological differences may explain this discrepancy. The present study included daily language use frequency alongside proficiency, providing a more comprehensive measure of functional multilingual engagement. Moreover, Thanissery et al.’s advantage was limited to high-monitoring conditions, not implemented here. This aligns with prior evidence that cognitive advantages linked to multilingualism are often condition-dependent and context-sensitive.

The current results are consistent with Martin-Rhee and Bialystok (Reference Martin-Rhee and Bialystok2008), Papageorgiou et al. (Reference Papageorgiou, Bright, Periche Tomas and Filippi2019) and Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Uchikoshi, Bunge and Zhou2019), which also found null effects in response inhibition. The convergence across studies and age groups questions the generalisability of inhibition advantages and calls for caution in attributing broad cognitive benefits to multilingualism. Importantly, the lack of association persisted even after controlling for SES, suggesting that multilingual experience may not confer measurable advantages in response inhibition under typical conditions.

4.2. Mind wandering and internal attention regulation

However, the results supported the second hypothesis: multilingual proficiency was significantly related to lower levels of unintentional and intentional mind wandering, although no effect was found for meta-awareness. These findings suggest that the cognitive effects of multilingual experience may be more pronounced in domains involving internal attention regulation than in traditional executive function tasks focused on inhibition of external responses. This pattern diverge from Shulley and Shake (Reference Shulley and Shake2016), who found no differences in MW between bilingual and monolingual university students during EF tasks. Several key methodological differences may account for this discrepancy. While both studies involved university-aged participants, Shulley and Shake (Reference Shulley and Shake2016) adopted a binary classification of language background, whereas the present study used a continuous multilingual proficiency index that incorporated both self-rated proficiency and daily usage frequency, thereby capturing more granular variation in language experience. Additionally, Shulley and Shake (Reference Shulley and Shake2016) relied on a probe-based method administered during cognitive tasks, which may have underestimated stable individual differences in MW tendencies. In contrast, the present study employed BMW-3, a validated self-report measure that captures trait-level patterns in MW across contexts and includes items that reflect MW as it occurs in everyday settings. These methodological differences likely contributed to the contrasting results, with the present study offering greater sensitivity to individual differences in internal cognitive states, particularly as they manifest in real-world experience. This more nuanced measurement strategy may help explain why multilingualism was found to be negatively associated with both spontaneous and deliberate MW. It is plausible that the attentional demands of managing multiple languages, particularly the need to monitor, switch and suppress competing linguistic representations, strengthen top-down attentional control processes. In turn, these processes may enhance the regulation of internal thought, reducing the likelihood of task-unrelated mental content.

This interpretation aligns with theoretical frameworks that conceptualise MW as an EF-dependent phenomenon regulated by cognitive control mechanisms (McVay & Kane, Reference McVay and Kane2010; Smallwood & Schooler, Reference Smallwood and Schooler2015). Importantly, the current findings suggest that multilingualism may exert its strongest cognitive influence not on externally triggered behavioural inhibition, but on internally directed mental states such as MW. This shift in focus, from classic EF tasks to more ecologically valid, internally oriented outcomes, represents a promising direction for future research.

4.3. Meta-awareness

The expected positive relationship between the multilingual proficiency index and meta-awareness of MW (Hypothesis 3) was not observed. This may be due to several factors. First, while multilingualism might enhance attention regulation, it may not necessarily improve the metacognitive capacity to detect attentional lapses. Second, although the BMW-3’s meta-awareness subscale is validated and psychometrically sound, it relies on participants’ introspective accuracy, which can vary widely across individuals and may not always correspond to real-time monitoring capacities. Furthermore, the BMW-3 is designed to capture trait-level patterns, including those manifesting in everyday life contexts, but it may still lack the ecological sensitivity to detect subtle variations in metacognitive monitoring shaped by language experience. It is also possible that the hypothesised link between multilingualism and meta-awareness requires a higher level of cognitive maturity, extensive experience in metacognitive reflection or targeted training to become evident.

4.4. Theoretical and practical implications

The current findings have several theoretical and applied implications. Most notably, the dissociation between the null effect of multilingual experience on response inhibition and its significant associations with both UMW and IMW suggests that the cognitive effects of multilingualism may be domain-specific rather than domain-general. While classic EF tasks such as Go/No-Go or Stroop tasks have long served as standard paradigms in the bilingual advantage literature, they typically assess externally oriented, time-constrained responses in artificial contexts. In contrast, MW reflects internally directed cognitive phenomena that occur spontaneously in everyday life. The present results, therefore, point towards a more nuanced view: rather than enhancing general EF across all domains, multilingualism may be more closely linked to the regulation of internally generated thought, a capacity highly relevant to real-world functioning yet underrepresented in traditional experimental paradigms.

This calls for a more nuanced theoretical framework that moves beyond dichotomous claims of a universal “bilingual advantage” versus “no advantage.” Rather than treating multilingualism as a binary variable with generalised effects, future accounts should examine how specific dimensions of language experience, such as frequency of use, interactional context and code-switching demands, interact with task types and cognitive domains. This perspective aligns with recent proposals adopting a systems view of bilingualism, which conceptualise multilingual experience as a dynamic interplay between social, linguistic and cognitive dimensions (Tiv et al., Reference Tiv, Kutlu, Gullifer, Feng, Doucerain and Titone2022). In this respect, the current findings offer indirect support for the Adaptive Control Hypothesis (ACH) (Green & Abutalebi, Reference Green and Abutalebi2013), which posits that cognitive control adaptations are shaped not merely by language proficiency, but by the recurrent demands of language selection in different conversational settings (e.g., single-language, dual-language or dense code-switching contexts). However, the present study did not directly measure interactional context, limiting the extent to which ACH can be conclusively evaluated. Still, our results suggest that internally directed cognitive regulation, such as the suppression of MW, may be more sensitive to multilingual engagement than externally triggered inhibition, underscoring the importance of refining theoretical models to account for these domain-specific effects.

Practically, these results raise the possibility that multilingual experience may support the regulation of attention in everyday settings, offering cognitive benefits that may not be detectable through conventional laboratory-based EF tasks. However, multilingual experience is not a unitary construct, and its cognitive effects may depend on how language experience is operationalised. In the present study, some aspects of multilingualism appear to be more closely associated with MW regulation than others, suggesting that factors such as proficiency may play a distinct role relative to frequency or context of use. If these associations are replicated in future longitudinal or intervention-based research, second language learning could be strategically incorporated into educational or cognitive-behavioural programmes targeting individuals prone to excessive MW, such as students with attentional regulation difficulties or individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by persistent difficulties in sustaining attention and regulating thought (Faraone et al., Reference Faraone, Bellgrove and Brikell2024). Unlike formal cognitive training, multilingual communication entails continuous engagement in goal-directed processing, language monitoring and suppression of interference, all embedded in real-life social contexts. These ecologically valid demands may promote the development of attentional stability and thought regulation over time. As such, the present findings suggest that meaningful cognitive improvements may arise not only from structured interventions but also from immersive, sustained experiences like multilingual interaction in daily life.

4.5. Limitations and future directions

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the present findings. First, the sample was demographically narrow, with a disproportionate number of East Asian participants and early bilinguals. While this homogeneity may minimise confounds related to SES or age of acquisition, it also restricts the generalisability of the findings to more linguistically and culturally diverse populations, such as late bilinguals or those from less educationally advantaged backgrounds. Second, the reliance on self-report measures introduces inherent limitations related to subjectivity and potential bias. Although the BMW-3 has demonstrated strong psychometric validity (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Frischkorn, Sadus, Welhaf, Kane and Rummel2024), it remains dependent on individuals’ introspective accuracy. This can vary considerably and may not reliably reflect actual MW frequency or meta-awareness. Similarly, the components of the multilingual proficiency index, self-rated language proficiency and daily usage estimates are vulnerable to social desirability effects, overestimation or retrospective recall errors. Moreover, despite the index’s advantage over dichotomous classifications, it may still fail to capture crucial aspects of multilingual experience, such as the context-specific demands of language switching, interactional diversity or environmental entropy. Participants with identical index scores may nonetheless differ substantially in their real-world cognitive demands. Third, the present study did not include measures of emotional or personality factors, which previous research has shown to be related to both the content and frequency of MW. These factors may be particularly important in multilingual populations, which may have distinctive emotional or personality profiles. Finally, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the study precludes any causal conclusions. Although the results suggest a potential link between multilingual experience and reduced MW, the direction of this association remains unclear. It is equally plausible that individuals with stronger baseline executive control or greater self-regulatory capacity are more inclined to pursue or maintain multilingual engagement. Without temporal data or experimental manipulation, reverse causality and third-variable explanations, such as general cognitive motivation or personality traits, cannot be ruled out.

Building on the present findings and addressing the outlined limitations, several avenues for future research are warranted. First, to overcome the constraints of cross-sectional and correlational designs, future studies should adopt longitudinal or experimental methodologies, such as language learning interventions or naturalistic exposure tracking, to better assess causality and the temporal dynamics of cognitive change. Second, future work should unpack the multidimensional nature of language experience more precisely since age of acquisition, language switching frequency and context of use may exert distinct cognitive effects. Disentangling these components within a unified framework could help identify which aspects of multilingualism best modulate the relationship between executive functions and MW, and under which conditions such benefits emerge (McVay & Kane, Reference McVay and Kane2010). In line with this, the present findings suggest that language proficiency may play a more prominent role than language use; however, given the emerging nature of research on MW and bilingualism, this pattern warrants further investigation across different populations and contexts. Third, researchers should consider integrating both externally oriented executive tasks and internally focused cognitive measures within the same study design. Evaluating both domains simultaneously may help determine whether multilingualism selectively enhances internally directed regulation or whether task demands moderate the emergence of cognitive advantages. Fourth, as MW is also related to emotional aspects, future studies should include emotional aspects and consider MW content in addition to MW rate.

Since MW content can be either positive or negative, past or future oriented, it would be interesting to assess whether the experience of harmonious bilingualism (De Houwer, Reference De Houwer, Schalley and Eisenchlas2020) could be associated with greater well-being and more positive and future-oriented MW. In this context, it would also be of particular interest to study populations of adolescents with different levels of heritage language maintenance. Lastly, the inclusion of neurocognitive methods (functional MRI, EEG or pupillometry) could offer mechanistic insight into how multilingual experience affects attentional networks and the regulation of spontaneous thought. Such approaches would help determine whether multilingual engagement modulates attentional control networks or alters spontaneous thought patterns at the neural level, thereby extending the current behavioural findings and contributing to a more mechanistic account of how language experience shapes cognition.

5. Conclusion

This study contributes to a growing literature questioning the generalisability of the bilingual advantage in executive functions. While no significant effects were found for response inhibition or meta-awareness, multilingual experience was associated with reduced unintentional and, to a lesser extent, IMW.

Overall, our findings suggest that high proficiency in more than one language may enhance the regulation of internal attention rather than external behavioural inhibition. This highlights the need for research that extends beyond traditional EF paradigms towards more ecologically valid, self-reflective measures of cognition. The results offer a fresh perspective on how language experience might shape the mind and invite future work exploring its broader cognitive and applied implications.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728926101035.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Agnieszka Graham of Queen’s University in Belfast for inspiring this work and her kind initial input.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.