Introduction

AI art and cultural narratives around ageing

It is acknowledged that ageing is not just biological but deeply cultural (Gullette Reference Gullette2004; Luborsky and Sankar Reference Luborsky and Sankar1993). In the past decade, there has been growing recognition of the environmental and cultural aspect of ageing, with an emphasis on how cultural narratives shape elderly life and wellbeing (Ng and Lim-Soh Reference Ng and Lim-Soh2021; Ohs and Yamasaki Reference Ohs and Yamasaki2025). Ageing perceptions shape both the psychological and the physical experiences of old age (Levy Reference Levy2003). However, dominant ageing narratives reinforce ageism by equating old age with frailty and dependency, limiting alternative perspectives (Hepworth Reference Hepworth, Coupland and Gwyn2003; Katz Reference Katz2001). In this article, we explore how artificial intelligence (AI) art could contribute to reshaping cultural narratives around ageing.

Any imagery, with or without the intervention of AI, is not isolated in our cultural world. Stuart Hall states that ‘representation is an essential part of the process by which meaning is produced and exchanged between members of a culture’ (Hall Reference Hall and Hall1997, 15). Media and cultural artefacts create and reinforce societal norms through the process of representation. Images generated using AI reflect the meanings embedded in training data and produce new but recognizable visual combinations (Arielli and Manovich Reference Arielli and Manovich2024). Recent studies examine how AI systems perpetuate cultural biases, for instance by portraying females in traditional or aesthetic-focused roles (Sandoval-Martin and Martínez-Sanzo Reference Sandoval-Martin and Martínez-Sanzo2024) and by recycling harmful stereotypes in visual representations of dementia (Putland et al. Reference Putland, Chikodzore-Paterson and Brookes2023). Artistic intervention may challenge embedded bias, both in systems and in collective perception, by raising awareness or addressing them in unexpected ways. Mirzoeff (Reference Mirzoeff2002) argues that visual culture functions as a powerful space for resistance and reimagining societal norms. This capacity of visual media supports the potential of AI visual art: when guided by curation and creative direction, it could disrupt dominant cultural assumptions about ageing, create counter-hegemonic representations and open new spaces for alternative narratives.

In gerontological discourse, Zhuo and Cao (Reference Zhuo and Cao2025) make a critical update to the classical model of successful ageing (Rowe and Kahn Reference Rowe and Kahn1997), extending from individual performance to broader environmental influences. Building on this perspective, we propose that AI-generated art could be examined as part of this environmental shift, as today’s AI-infused digital environments increasingly mediate societal narratives and public perception (Elliott Reference Elliott2019; Jaidka et al. Reference Jaidka, Chen, Chesterman, Hsu, Kan, Kankanhalli, Lee, Seres, Sim, Taeihagh, Tung, Xiao and Yue2025). In the following review of the literature, we use a 3A model (AI, arts and ageing) as a structural tool for mapping out the intersections of these three fields (see Figure 1), followed by a brief explanation of theoretical grounding. This model helps identify trends within fragmented scholarship and pinpoint gaps in the intersection of AI art and ageing representations, leading to our central question: can AI art, as a new form of visual representation, contribute to successful ageing by shaping cultural narratives?

Figure 1. Identifying a research gap in the ‘3A’ framework (ageing, AI and arts).

Literature review

Arts and ageing

With increasing efforts to examine the integration of artistic forms in health promotion and communication, scholars worldwide have recognized the impact of arts-based interventions on wellbeing and health care (e.g. Cox et al. Reference Cox, Lafrenière, Brett-MacLean, Collie, Cooley, Dunbrack and Frager2010; Sonke et al. Reference Sonke, Rollins, Brandman and Graham-Pole2009; Tan et al. Reference Tan, Tan, Tan, Yoong and Gibbons2023). Recent research celebrates the role of various art forms in enhancing older adults’ wellbeing, with visual arts emerging as a dominant focus (Bowman and Lim Reference Bowman and Lim2022; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Chirino, Cortez and Gearhart2020). Studies on visual arts and ageing demonstrate the arts’ diverse benefits for older adults, such as cognitive function and communication improvements (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Chirino, Cortez and Gearhart2020), enhanced social connections (Bowman and Lim Reference Bowman and Lim2022) and increased sense of self-worth and community engagement (Rodrigues et al. Reference Rodrigues, Smith, Sheets and Hémond2019). Visual arts programmes have shown particular promise when implemented with skilled facilitation and participant choice in art mediums, especially when culminating in public exhibitions that provide meaning and purpose (Moody and Phinney Reference Moody and Phinney2012).

Extensive research supports the functional benefits of visual arts engagement, including cognitive, social and psychological outcomes (Richmond-Cullen Reference Richmond-Cullen2018; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Das, Maguire, Fleet and Punamiya2024), but few studies examine the arts’ cultural impact on ageing representation rather than their therapeutic effects (e.g. wellbeing, memory care). Among the few exceptions, Madrigal et al. (Reference Madrigal, Fick, Mogle, Hill, Bratlee-Whitaker and Belser2020) and Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Vreugdenhil and Macnish2018) discuss how contemporary art events create opportunities to showcase positive representations of ageing, disrupting deficit-focused stereotypes. While AI art has proliferated in both institutional settings and popular media, surprisingly little research addresses its implications for key sociocultural subjects like ageing.

AI and ageing

Recent studies have explored how age-related bias in AI can be identified and mitigated through algorithmic design, data practices and inclusive innovation strategies (Berridge and Grigorovich Reference Berridge and Grigorovich2022; Chu et al. Reference Chu, Donato-Woodger, Khan, Shi, Leslie, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi, Nyrup and Grenier2024; Mannheim et al. Reference Mannheim, Wouters, Köttl, van Boekel, Brankaert and van Zaalen2023; Rubeis et al. Reference Rubeis, Fang and Sixsmith2022). In AI-generated imagery specifically, scholars have identified the under-representation of older adults in training datasets (Park et al. Reference Park, Bernstein, Brewer, Kamar and Morris2021) and problematic visual stereotypes (Stypinska Reference Stypinska2023). Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Xu, Nishikitani, Patil, Hule and Bradley2024) highlight that AI image-generating tools produce biased depictions of different age groups, often rendering images of older people with lower brightness and sharpness while portraying them as incompetent, lonely, vulnerable and worried.

While some counter-narratives advocate for inclusive AI representations through participatory design and intersectional approaches (Neves et al. Reference Neves, Petersen, Vered, Carter and Omori2023; Rubeis et al. Reference Rubeis, Fang and Sixsmith2022), research remains scarce on AI-generated imagery as a counter-hegemonic force in ageing representation. Though a few studies have begun to examine how AI influences ageing narratives (Gallistl et al. Reference Gallistl, Banday, Berridge, Grigorovich, Jarke, Mannheim, Marshall, Martin, Moreira, Van Leersum and Peine2024; Stypinska Reference Stypinska2023), little attention has been given to its role in shaping public perceptions and identity formation in later life. This raises the question of whether AI-generated imagery, when presented as artistic practices, could serve as an effective medium for reimagining cultural environments for ageing.

AI and arts

The integration of AI into art opens up new means of artistic expression and engagement (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2022) while also raising complex questions about human agency and interpretation (McCormack et al. Reference McCormack, Gifford, Hutchings, Ekárt, Liapis and Castro Pena2019; Park Reference Park2024; Yusa et al. Reference Yusa, Yu and Sovhyra2022). Some scholars debate whether machine-created imagery can be justified as ‘real’ art (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2022; Coeckelbergh Reference Coeckelbergh2017; Pereira and Moreschi Reference Pereira and Moreschi2021), while others argue for moving beyond these debates to explore the social and cultural dimensions of AI art (Daniele and Song Reference Daniele and Song2019; Yusa et al. Reference Yusa, Yu and Sovhyra2022). For instance, Bak Herrie et al. (Reference Bak Herrie, Maleve, Philipsen and Staunæs2024) investigate how AI-generated imagery democratizes artistic engagement by allowing users, regardless of traditional artistic skills, to contribute to and form new visual communities. However, there remains a critical gap in examining how AI art shapes cultural narratives, particularly concerning ageing and other important societal issues.

Studies on AI-generated images and avatars have begun addressing the representation of ageing in digital spaces. Zorrilla-Muñoz et al. (Reference Zorrilla-Muñoz, Moyano, Marcos Carvajal and Agulló-Tomás2024) argue that equitable representation of ageing in AI imagery is essential for reshaping societal narratives and fostering inclusivity. Similarly, Liao (Reference Liao2024) examines how AI avatars shape self-perception and identity, stating that AI-generated representations of ageing can both reinforce societal biases and offer alternative ways to visualize ageing beyond restrictive norms. These studies demonstrate the idea that AI technology ‘changes the way we think, act, and perceive the world’ (Arielli and Manovich Reference Arielli and Manovich2024, 190) and suggest that AI-generated imagery can act as an active site of cultural negotiation.

Research gap and theoretical grounding

Despite the growing academic interest in the intersection of AI, arts and ageing, little research explores how AI art influences ageing through reshaping its cultural narratives. Existing efforts predominately focus on the therapeutic benefits of visual arts or on technical aspects of AI, leaving its cultural impact largely unexplored. Methodologically, no prior research has used qualitative case studies with multi-stakeholder interviews to examine AI art’s influence on the cultural aspect of ageing. This research fills both the knowledge and the methodological gaps by using an innovative study design to investigate AI art as a site of cultural negotiation. Drawing from empirical data generated through a three-study procedure, this article aims to present new perspectives on AI art’s cultural implications for ageing narratives and thus opens up an important dialogue around alternative ageing identities and notions of later life in the age of AI.

Hall’s (Reference Hall and Hall1997) theory of representation anchors our understanding of cultural meaning as socially produced and subject to contestation. We conceptualize AI art as a relational space where visual narratives are negotiated across multiple dimensions, and representation becomes a key site where both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic discourses can emerge. The theoretical grounding of this research is informed by Twigg’s (Reference Twigg2004) feminist gerontology, which frames ageing, gender and the body as socially constructed and culturally coded, particularly through visual representation. Drawing from post-humanist theory and new materialist thought, the study adopts an understanding of subjectivity as emergent from relations among humans, technologies and environments (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2013), thereby moving beyond the individualistic or deficit-based views and foregrounding ageing as shaped by non-anthropocentric entanglements. Coeckelbergh’s (Reference Coeckelbergh2011) work on artificial others extends new materialist thinking by emphasizing the role of language, imagination and social expectations in constructing AI’s perceived agency, which in turn influences how AI-generated outputs are interpreted and legitimized. This rationale helps situate AI within the relational assemblage where human imagination, algorithmic aesthetics and sociocultural narratives intersect to shape how ageing is visually reconfigured.

Bridging the fields of media studies and cultural gerontology, this interdisciplinary research makes an innovative and timely contribution to the still-limited scholarship on AI art’s potential for challenging dominant ageing narratives through algorithmically mediated representations. To add to the burgeoning discussions centring on AI-generated imagery, we seek to further the understanding of its impacts on real-world issues by using a culturally specific issue with social urgency. We acknowledge the ongoing debate surrounding ‘AI art’, including in relation to questions of creativity and the aesthetic qualification of AI-generated images. However, this study chooses to sidestep these metaphysical debates, focusing instead on AI art’s practical and cultural implications.

Study design

A tripartite qualitative design

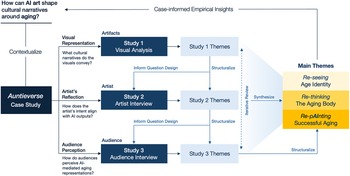

This research features a qualitative multi-stakeholder design (Coghlan and Brydon-Miller Reference Coghlan, Brydon-Miller, Coghlan and Brydon-Miller2014), integrating three studies centred on a single case: visual analysis, artist interviews and audience interviews (see Figure 2). To critically capture the perspectives of each stakeholder (the artefacts, the artist and the audience) and allow them to ‘speak’ freely, a procedural exploration is chosen instead of focused groups. This design balances a holistic view with a nuanced understanding of how AI art shapes ageing narratives.

Figure 2. A multi-stakeholder three-study design process flowchart.

A multimodal and iterative strategy guides the process. As AI-generated images are fluid in meaning and shaped by audience perception and AI training biases, we adopt an adaptive approach, where analysis begins early and evolves alongside the data collection. Patterns emerging in one phase shape the next, allowing the research to remain responsive to new insights. Themes from all three studies are iteratively triangulated and synthesized, leading to final themes that reflect the dynamic interplay among visual representation, artistic intent and audience perception. This approach grounds the findings in both visual and interpretative analysis, enabling a rich exploration of AI’s role in shaping cultural narratives of ageing.

Case selection

Auntieverse is an AI-generated art project created by Singaporean artist Lim Wenhui under the name Niceaunties. Initiated in February 2023, this ongoing project consists of 1,000 images presented across ten chapters: (1) ‘Auntie City’, (2) ‘Spa menu’, (3) ‘Factory’, (4) ‘Auntique’, (5) ‘Auntiesocial’, (6) ‘Fashion’, (7) ‘TESLA’, (8) ‘IKEA’, (9) ‘MoMA’ and (10) ‘NASA’ (see the supplementary material). Auntieverse serves as a world-building framework that connects all images and presents an evolving narrative about the life of Singaporean aunties.

Lim has stated on multiple occasions that her creative choice of depicting aunties originated from her experience growing up with her aunties and years of reflection on ageing and the auntie archetype. In Singapore, the term ‘auntie’ often carries connotations of being old and conservative, leading younger women to resist this label (Wong Reference Wong2006). Meanwhile, there are different voices questioning what aunties are really like. Singaporean journalist Yeo Boon Ping reflects on his encounters with aunties at local supermarkets, re-seeing them as warm, encouraging, life-knowledgeable and relatable figures; he states that, despite being widely vilified, auntie culture is an intrinsic and universal part of the nation’s identity and thus ‘should be Singapore’s entry into the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ (Yeo Reference Yeo2021). Further, CNA correspondent Hidayah Salamat wittily questions whether the Singaporean auntie could be ‘a national symbol’ not only because she is both an ‘enduring stereotype’ and an ‘endearing archetype’ but also, more importantly, because ‘she is us’ (Salamat Reference Salamatn.d.).

Thus, Auntieverse is selected as the case study for its explicit engagement with ageing through AI-generated images, its rich visual content guided by clear artistic intentions and its global influence. With broad media coverage in The Straits Times, Forbes, and The Guardian, high-profile events like Christie’s 3.0 charity auction and exhibitions at institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, Auntieverse offers a culturally rich site for exploring the intersection of artistic intent, algorithmic influence and societal perceptions of ageing.

Study 1 visual analysis

Methods

The first study is a systematic visual analysis of Auntieverse’s storytelling. To ensure both breadth and depth in analysis, all Auntieverse images were initially reviewed to identify recurring motifs, dominant themes and visual anomalies. From this dataset, 40 images (four from each chapter) were selected for in-depth analysis. This selection process mirrors natural audience engagement, where viewers first develop an overall impression before focusing on specific images that stand out. Preliminary findings informed the subsequent artist interview, where key themes were further examined to determine whether they were deliberate artistic expressions or unintended by-products of AI’s generative processes.

The analytical approach follows Gillian Rose’s (Reference Rose2016) visual methodologies. Each selected image was documented in an image log, where both formal qualities (descriptive notes) as well as thematic and symbolic elements (interpretive notes) were recorded. Particular attention was given to how AI-generated textures and aesthetic choices influence the emotional and narrative depth of the images. Symbolic patterns – such as synchronized movement, depictions of labour and visual metaphors of agency – were analysed to determine how Auntieverse might reinforce, subvert or complicate cultural narratives of ageing.

Results and analysis

The grand performance: ageing as a spectacle

In Auntieverse, ageing is portrayed as bold, dramatic and impossible to ignore – far from the preconception of frailty and dependence. Key visual codes emphasize autonomy and empowerment: ‘urban infrastructures’ depict aunties as the masterminds behind city planning and mobility solutions; ‘adaptive architecture’ transforms spaces to accommodate their needs; ‘self-sustaining systems’ present aunties as resourceful leaders managing autonomous communities; and ‘utopian mobility’ envisions them navigating futuristic transport with total independence.

In ‘Auntiesocial’, this empowerment manifests as aunties wearing glittering sequined bodysuits and oversized sunglasses, posing like fashion icons on a sunlit beach (see Figure 3). Their perfect silver hair gleaming like the essential party accessory and their vogue poses are unapologetically dramatic. Meanwhile, in ‘Auntie City’, their colossal feet form the foundation of towering residential buildings, possibly symbolizing the generation’s role in shaping Singapore’s early years. Lim, drawing on her architectural background, metaphorically fuses aunties’ bodies into the urban landscape, transforming them into pillars and underground tunnels (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Artworks from the ‘Auntiesocial’ and ‘Auntie City’ chapters.

Beauty as paradox

The aunties pose for fashion shows, indulge in luxurious spa treatments and emerge with meticulously styled hair, all with a sense of calm and self-assuredness. At first glance, these images celebrate beauty as creative resistance, showcasing ageing bodies with bold self-expression and glamour. However, beneath the polished surfaces lies a complex narrative. The visual code ‘beauty labour’ is evident in the ritualized self-maintenance, portraying beauty as an exhaustive, almost industrial process.

In ‘Auntieque’, aunties are ‘renovated’ like architecture while getting haircuts; in ‘Spa menu’, excessive needles and decorations covering wrinkled faces symbolize painful plastic surgery procedures, reminding viewers of the anxieties tied to youth-centric ideals. A striking example from the ‘Fashion’ chapter features a close-up of female genitalia, where ovaries are replaced by oversized cat-eye sushi and the vagina is depicted as a cat’s mouth – a playful yet unsettling visual pun on ‘pussy’. This image encapsulates the tension between empowerment and discomfort, where beauty is not merely a state but a performance that blends self-expression with a theatrical display of labour and transformation.

The ‘collective aesthetics’ of AI

In Auntieverse, autonomy and individuality are not always aligned with viewers’ presumptions. By ‘collective aesthetics’ we refer to the visual tendency of AI-generated imagery to emphasize repetition, symmetry and coordinated group behaviour over individual differentiation. These collective aesthetics manifest visually through repeated group actions and mirrored body language, rendering the aunties as choreographed ensembles. Visual codes of ‘synchronized labour’ and ‘standardized individuality’ show aunties performing coordinated tasks, their distinctiveness replaced by a ceremonial collectivity. In ‘Factory’, female older adults work together at futuristic food farms, massive conveyor-belt sushi restaurants and industrial seafood-processing plants. In ‘NASA’, they dress as astronauts preparing meals in a space station or having a culinary lesson together in front of a huge holographic screen that shows a commander-like granny smiling and instructing. Non-human symbols like food and cats also repeat across the scenes, contributing to a ‘cultural loop’ that creates a sense of uncanny familiarity.

The imagery presents an ambiguity between showcasing community solidarity and imposing a sense of uniformity. The tension is likely driven by AI’s generative patterns, contrasting with the artist’s intention to depict elderly autonomy and vibrancy, as evident in other visual codes.

Study 2 artist interview

Methods

The second study consisted of a semi-structured interview with Lim, to gain deeper insight into her creative process and the role of AI in shaping Auntieverse. The interview process began with an email outreach through Lim’s official Niceaunties website. Prior to the formal interview, the researcher and Lim met once and exchanged messages to establish rapport and clarify the research objectives. The interview was recorded with consent, transcribed and analyzed through thematic coding.

The discussion was guided by three central themes. First, Lim reflected on her motivations for developing Niceaunties and how AI technology influenced her artistic process. Second, she shared her perspective on ageing and its cultural implications in the Singapore context. Finally, the conversation addressed patterns and surprises found in Study 1, such as the perceived aesthetic bias in the AI-generated imagery and scenes showing old female figures working collectively, inviting the artist to clarify her intentions regarding cultural representation. The findings from this study informed Study 3, shaping interview questions that explored the gaps and overlaps between artistic intent and audience perception.

Results and analysis

Reclaiming aunties as ‘nice’

‘Why Niceaunties?’ This is often the first question people ask when encountering Lim’s work. It is, in fact, the artist’s direct response to the culturally specific stereotypes towards older women in Singapore. Growing up in a large family with strict aunties, Lim did not have the most positive experience with aunties herself.

Auntie culture is a very ingrained thing in Singapore, it is actually negative, so I thought what if I make the imaginary world where I reimagine this perception of aunties to be nice. So ‘Niceaunties’ is meant to be an irony, because aunties are not nice, generally, Lim explained.

Being ‘nice’ and being ‘free’ are interrelated in Auntieverse. She described Auntieverse as a fantasy world where older women are no longer tied to their familial and social roles but have absolute freedom:

Aunties are often seen as stuck in roles – they have no choice. So, I imagined a world where they have full control, where they are the queens.

Lim visualized this sense of autonomy through images of aunties engaging in extreme physical, social and spiritual freedom. Her grandmother having dementia for 20 years also led her to reflect on ageing as both constraint and potential escape. Through art, Lim imagined her grandmother escaping into an imaginary world with absolute freedom. While autonomy is central, Lim also acknowledged that real-life aunties might not see themselves as ‘free’ in the same way she imagined them.

Beauty and anti-ageism critiques

Lim explained that the fear of ageing, particularly in Asian culture, is closely tied to the fear of losing power, mobility, companionship and beauty. With three out of the ten chapters in Auntieverse specifically focusing on beauty, Lim’s work critically engages with these cultural anxieties. Instead of depicting aunties as youthfully pretty, Lim intentionally introduces uncanny and metamorphic imagery to serve as visual critiques of beauty standards (see Figure 4). She aims to subvert beauty anxieties, showing that beauty is not about conforming to external expectations but about self-empowerment and authentic joy. Drawing from her own experiences, including witnessing the Chinese ‘chanjiao’ (foot binding) custom within her family, Lim critiques how female beauty standards, especially in Asia, are often shaped by the male gaze. As Lim noted:

Beauty is about feeling good for yourself, not because of others. But society pushes this fear of ageing – especially for women.

Figure 4. Artworks from the ‘Spa menu’ chapter.

The aunties in her images are not concerned with appearing young or conforming to expectations. Instead, they engage in playful, bold and sometimes surreal beauty practices, embodying what Lim calls their ‘superpower’ – the ability to not care anymore. She concludes our conversation with a thought that captures her philosophy:

I think ageing is beyond skin deep. As we age spiritually, beauty and autonomy are one thing. So, you’ll find your own definition of what’s true and beautiful to your soul.

Interestingly, when asked about criticism regarding her portrayal of ageing women, especially those with extreme appearances, Lim shared two notable instances. In one case, a Japanese audience on Instagram misinterpreted her depiction of aunties wrapped in sushi (see Figure 4) and accused her of promoting cannibalism. Lim clarified that the scene was meant to depict a bath treatment and that she had no intention or awareness of a cannibalistic reference.

The second instance was about a Chinese gallery that wanted to show her works in China but could not because the content ‘looks too Japanese’. She admitted and justified that the overall Japanese aesthetic was influenced both by her personal love for sushi and by model biases. The earlier version of Midjourney, she explained, could generate clear Asian female faces only when the word ‘Japanese’ was included in the prompt. Now the limitation has been resolved, and she has also moved away from sushi-themed imagery.

Creative agency: human or machine?

Unlike many artists who integrate AI into their existing artistic practices, Lim did not have a traditional artistic trajectory before creating Niceaunties. While her reflections on ageing had long been a rich source of inspiration, it was the technology itself that prompted her to create:

I think I was inspired by the freedom and the speed the technology offered. So it was more like a tool that allows you to visualize your ideas really quickly and improve them many times in the same period of time that you would do [them once] in the traditional world.

Lim described AI as a ‘super assistant’, comparing it to photography, once also a controversial medium that eventually became a legitimate form of artistic expression. Despite our repeated use of the term ‘AI art’, Lim expressed her discomfort with the label. ‘I’m still kind of allergic to the word’, she said, arguing that AI is simply a digital tool and art created with it should be seen as digital art, not segregated into a niche category.

Lim also addressed our misinterpretation of the factory scenes in Auntieverse. Where we saw labour and uniformity, she intended a utopian community space where aunties were not working but enjoying life:

They’re not really working in those settings. In the factory, for instance, everything is automated, and they are doing yoga. So, it’s actually a social club. It’s really not about working, it’s more about coming together and having the best life ever in any setting you can think of.

She continued to explain that the rationale for this visual choice was rooted in her personal history, implying that the factory-like scenes were her creative decision rather than a highly AI-generated choice:

My parents worked in factories in Singapore in the 1980s. That world was full of aunties. I wanted to flip that – make it a world where they are in control.

When asked why aunties in Auntieverse are still often seen in traditional roles like cooking, Lim responded:

I always see them as super humans. They can do everything, but they are never appreciated. They can cook so well, they do all the housework, but this housework is dismissed as normal… So it’s something to celebrate, I think. Anyway, one of the things about [the] Auntieverse is to blow up very small things in everyday life here and make [them] a big deal.

Overall, we noticed that what we had initially interpreted as AI’s digital footprint could also be related to the artist’s vision and storytelling intent.

Study 3 audience interview

Methods

The third study examined audiences’ interpretations of Auntieverse. Five female participants from different age groups (20s–60s), all Singaporean citizens or long-term residents, were selected to ensure familiarity with local cultural conceptions of ageing and ‘aunties’. They came from diverse professional and personal backgrounds, including working professionals, retirees and homemakers.

Participants browsed Auntieverse on an iPad at their own pace, selecting images they found compelling, unusual or thought-provoking. Interviewers used open-ended prompts to encourage free-form exploration and reflections, allowing participants to share initial reactions and deeper insights. The insights gathered from these interviews were then compared with the artist’s perspective, highlighting areas of coherence and contradictions. After transcription, thematic analysis was conducted inductively so that themes could emerge directly from participant responses rather than being pre-imposed. Given the iterative nature of the research, findings evolved throughout data collection, refining the thematic framework over time.

Results and analysis

Who are the aunties?

Ageing and being an auntie are related in interesting ways. While all participants acknowledged that ageing often leads to being labelled an auntie, they also agreed that auntiehood is a complex and shifting identity. Most participants felt that a person is seen as an auntie when they or others recognize her as such, often based on a blend of visual cues and social behaviours. One participant associated the auntie title with motherhood, recalling: ‘When I came back to work after maternity leave, people called me auntie. I was only 32’. Another participant, in her 50s, rejected the label entirely, insisting that she does not fit the ‘auntie’ stereotype because she is still active, positive and career-focused, unlike others who are always ‘worrying about the future, [this] and that’.

Three participants pointed out that this relational identity was flattened in the representations, where aunties were ‘too old already’ and ‘all look alike’. They criticized the mismatch between the name ‘Auntieverse’ and the subject matter of female older adults in exaggerated wrinkles and silver hairs, which might reinforce ageism by tying negative auntie stereotypes to being old. Surprisingly, while older participants were more critical of the stereotypical auntie image, younger audiences seemed more accepting, often praising Auntieverse for its bold and eye-catching visuals, even if they did not fully relate to the representations.

Beauty, autonomy and social status

The influence of beauty anxiety on female ageing was also a prominent theme. One participant shared a personal story about visiting a cosmetic surgery clinic just a day before the interview. She admitted feeling deep anxiety over her ageing appearance but ultimately decided against the procedure owing to fears of pain and side effects. This real-life hesitation mirrored the social critique found in Lim’s ‘Spa menu’ images, where aunties undergo extreme beauty treatments, highlighting the discomfort and pressures tied to youth-centric ideals.

Three out of five participants associated financial stability with the ability to age gracefully and autonomously. ‘If she has money, she can live however she wants. If not, she’s just working to survive’, said one participant. Another expressed scepticism about the portrayal of female older adults in Auntieverse: ‘The aunties I know are not so glamorous. They work hard, they survive, but they are not in control like the images show’. Younger audiences, while attracted to the visuals, also felt that Auntieverse offered more of a fantasy of wealth and leisure than a realistic portrayal of ageing.

For all participants, the carefree and powerful aunties in Auntieverse did not reflect the full spectrum of ageing experiences, particularly those influenced by economic realities. Thus, there is a perception gap between Auntieverse’s intended message of beauty and autonomy and how audiences interpret the visuals through the lens of class and economic privilege.

Questioning AI’s role

While some controversial visual choices were identified through careful scrutiny in Study 1, we were surprised to see how the participants picked those up almost immediately and questioned the legitimacy of AI art. One participant questioned the imagery of uniformity: ‘Why do they all look the same? It feels like a factory, not freedom’. This comment reflects a tension between individual autonomy and social conformity, as many participants felt that the hyper-coordination in Auntieverse depicted aunties as part of a systematized collective rather than individuals with unique identities (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Artworks from the ‘Factory’ and ‘NASA’ chapters.

Another point of contention was the repetition of Japanese cultural symbols, which perplexed some participants. ‘Is this a Japanese artist?’ asked one participant, noting the prevalence of sushi, cats and inter-Asian aesthetics in the visuals. When informed that the artist is Singaporean, she responded, ‘Oh, but there are so many Japanese images it feels a bit off’, reflecting a broader uncertainty about whether these choices were intentional or a result of AI’s training data biases. One participant speculated that it was the AI that associated successful ageing with Japanese culture:

I know most Western people think of Japan as the best, the most peaceful, the healthiest country in Asia. There [are] so many Japanese movies showing very old people working happily … be[ing] the adorable and fun granny, cooking healthy Japanese meals every day. So, I guess AI would think Japanese people enjoy the ideal old life.

Depictions of aunties in traditional roles, such as cooking, cleaning and care-giving, also drew critique. Some participants felt that these representations were stereotypical, reinforcing outdated gender roles. ‘Why are they always cooking or cleaning? It’s like they’re stuck in these roles forever’, noted one participant. Another addressed, ‘I know aunties who are businesswomen, leaders – not just homemakers. I wonder if this is AI showing what it thinks aunties do or if it’s the artist’s choice’, raising questions about whether the imagery was shaped by societal norms embedded in the algorithm’s training set.

Younger participants were more inclined to accept the AI-generated imagery as part of the digital art aesthetic, though they too noted the repetitive motifs. One said: ‘AI art is still like any other kind of art; it cannot give a complete representation. But the good thing is how AI shows us something really crazy and interesting to dream of, or to reflect on, when we are being afraid of ageing’.

Discussion

Re-seeing age identity

Auntieverse exemplifies how AI art can shape cultural narratives around ageing, both by presenting new possibilities and by provoking critical reflection. The AI-generated representations enable a process of ‘dis-identification from familiar and hence normative values’ (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2013, 89) with bold scenarios that are impossible in real life, thus inviting the audience to interrogate stereotypical and ageist cultural imaginaries that impose decline narratives or unrealistic age-defying ideals (Laceulle Reference Laceulle2018). The exaggerated activities and surrealist juxtapositions help revisualize age identity free from cultural and physical boundaries, as they challenge the connotations of outdatedness and marginalization often associated with Singaporean aunties, depicting aunties as confident masters of their worlds. At the same time, Auntieverse invites viewers into a world where ageing is not a quiet, gentle drift into the background, introducing a reflective language into their meaning-making of the ageing process.

The artist Lim’s own journey of self-reflection on ageing identity is already embedded in Auntieverse. Like many Singaporeans, she once viewed aunties as strict, overbearing and far from ‘nice’. But as she aged she began to see beyond the surface, and her work implies that the harsh aspect of aunties’ identity that she once perceived was influenced by their constrained freedom in social and cultural life. These aunties had endured lives defined by their roles as care-givers, homemakers and silent supporters, often losing themselves in the process. Auntieverse, then, presented a utopian escape but is also in fact the artist’s sincere attempt to rewrite these narratives, imagining a world where ageing equates to independence rather than servitude.

Yet, this portrayal carries contradictions. While the artist sought to transform the stereotypically ‘not nice’ aunties into icons of freedom and joy, Auntieverse also risks falling into the same stereotypes that it aims to subvert. The AI-generated imagery of old aunties, with their uniform silver hair and exaggerated wrinkles, reduces the complexity of the ‘auntie’ identity to a singular, almost caricatured type. Although these aunties may occupy a focal position in every scene, the audience-expected individuality is often lost in the algorithm’s repetitive patterns.

Our audience interviews revealed a gap between this imagined world and real-life experiences. The majority of our participants felt that the visuals did not show the full spectrum of what it means to age. Instead, the images leaned into an oversimplification, where ageing became a predictable look and a specific way of being. The project’s attempt to depict autonomy and vibrancy through a utopian lens was met with mixed responses; while some saw it as empowering, others found the dramatic and performative spectacles unsettling.

This tension between intention and perception strikes at the core of how AI art shapes cultural narratives. If ageing is to be a meaningful and inclusive process, it must allow for complex, embodied and culturally situated identities rather than substituting one idealized standard for another. Transforming cultural narratives around ageing comes not only from showing new possibilities but also from respecting the diverse and layered realities of the ageing experience. It is evident in our case that AI tends to selectively amplify certain visuals, guided by the patterns it learns from pre-existing data. As a non-human agent trained by and through human culture, AI shows a distortion and prioritization of ageing-related visual elements that opens up a reflective space, and the distinct reactions, the gap between the human artist’s intention and the audience’s perceptions, are in a way highly productive for initiating new discourses. In this sense, Auntieverse demonstrates how AI art can powerfully and efficiently prompt the audience to reimagine age identity, while also serving as a reminder that bold new visions need participatory space to negotiate with the real-life complexities and contradictions of ageing.

Rethinking the ageing body

Auntieverse offers a powerful visual rethinking of the ageing body. Whether in relation to declining health conditions or changing appearance, the body is the first place where we directly experience the social and physical aspects of ageing (Clarke and Korotchenko Reference Clarke and Korotchenko2011). It is also where cultural and institutional practices impose discipline, and frame ageing as a process to be managed, corrected or slowed down through medical and technological interventions (Katz Reference Katz1996). The female ageing body in Auntieverse is hyper-visible and proactive, which aligns with Twigg’s (Reference Twigg2004) articulation of the body as socially constituted and entangled with gendered expectations.

The treatment of beauty in Auntieverse is a relatively straightforward exemplification of the artist’s rebellious energy in criticizing existing sociocultural constraints forced on ageing female bodily image. The bold and sometimes unsettling scenarios use the ageing body as a medium for this critique. Viewers may interpret these images as either a sarcasm of beauty standards or an assertion of autonomy, where aunties simply go crazy on their body image as they have obtained the ‘superpower of not caring anymore’. Aesthetically, AI’s image-generating tool’s strength in layering unexpected visual elements lends itself to these uncanny, dreamlike images and potentially contributes to engaging viewers in rethinking cultural narratives surrounding ageing bodies.

However, when the computational aesthetics overshadow the artist’s agency, surprises could go from excitement to aversion. When audiences encounter the AI-generated images featuring elderly human figures, especially when such figures can fit into their cultural context, they inevitably tend to focus on the body image – that of the depicted, their own and the gaps in between. In our Study 3, many participants found the visually surprising ageing bodies aspirational but disconnected from reality. While Lim saw her work as a platform to redefine beauty, some audience members felt that it reinforced societal pressures to look youthful and be socially active, which are ideals that can seem out of reach, especially for those without the financial stability to access such freedoms.

Participants shared personal stories of beauty anxiety, recalling moments when they considered cosmetic procedures but hesitated as they feared the pain and permanence. These real-life tensions reflect a broader struggle in cultural narratives around ageing. While Auntieverse pushes back against beauty norms, it also provokes sentiments related to class-based realities. The participants stated that autonomy over one’s appearance – whether through fashion, beauty treatments or lifestyle choices – is often a privilege. Financial stability and social status significantly influence how ageing is experienced and perceived, making Auntieverse’s vision more fantasy than a possible reality for many.

Auntieverse, at its worst, undeniably captures attention. Whether it was the Japanese audience on Instagram suspecting cannibalism in sushi-wrapped aunties or our study participants questioning the class implications of depicted activities, the project certainly sparked conversation. And perhaps that, in itself, is a success. Despite its challenges, Auntieverse remains a powerful example of how AI art can reshape cultural narratives around ageing. It creates a space in which to reimagine the ageing body as a counter-narrative to existing social perceptions, while encouraging critical reflection on the pressures and realities of growing older. By blending bold visuals with complex social commentary, Auntieverse shows that even if AI art cannot always control the narrative, it can certainly start one.

‘RepAInting’ successful ageing

What has emerged from our study is that AI art presents both opportunities and challenges in reshaping successful ageing. By ‘successful ageing’, we are deviating from the set standard for older adults to remain youthful and productive, as it often marginalizes those who cannot meet this standard and reinforces ageist attitudes (Katz Reference Katz1996). Auntieverse challenges these norms, not by setting new standards but by expanding the narrative possibilities through AI-generated imagery. Unlike traditional art, where human intention is often clear, AI’s involvement in creating cultural representation introduces a post-human agency to the artistic process.

The influence is twofold: first, it democratizes artistic creation, allowing individuals without formal artistic training to bring complex cultural narratives to life. Lim herself acknowledged that AI technology was not just a tool but in itself a source of inspiration. It is exactly AI’s power of ‘liberating individual imagination from material constraints’ (Eldagsen Reference Eldagsen2024, 37) that helped transform Lim’s years of reflections on ageing into visually striking and thought-provoking artworks. Second, AI brings its own aesthetic fingerprint, which can lead to surprising and sometimes problematic interpretations. For instance, Lim envisioned a utopian community space where aunties enjoy leisure time with the companionship of their peers; somewhat ironically, however, the repetitive motifs and uniform visuals led some audiences to perceive labour and conformity. Therefore, AI art represents neither pure extensions of the artist’s imagination nor fully automated creativity away from human subjectivity; rather, it is a post-human output of societies’ ‘collective unconscious’, a revelatory medium reflective of techno-cultural entanglements (Kalpokas Reference Kalpokas2023, 1). Auntieverse exemplifies this post-human assemblage where artistic agency and machine patterning co-construct the visibility and legibility of ageing.

Audience responses revealed how quickly they could pick up on the visual motifs and cultural inconsistencies, such as the prevalence of Japanese aesthetics despite the project’s Singaporean context. The unexpected ‘problematic’ elements got them to question, which, then, is not necessarily an undesirable outcome as it sparked engagement. A recent experiment indicates that AI is considered to possess less mind, while ‘positive deviation from expectations’ could lead to increased appreciation (Messingschlager and Appel Reference Messingschlager and Appel2023, 9). This suggests that AI’s role in shaping cultural narratives is not just about what it creates but about how audiences make sense of and respond to its outputs – a process that will keep evolving as AI technology advances and public familiarity grows.

This sensitivity to cultural symbols also touches on a broader truth about AI art as a cultural mediator. While elements like grey hair or sushi may appear stereotypical, their recurrence reflects both the visual tropes embedded in AI training data and the artist’s own playful, self-aware use of cultural motifs. Rather than endorsing stereotypes, these visuals can invite critical reflections and discourses, which guides us to improve the representations of ageing both in the algorithms and in our society. As artworks reflect cultural beliefs, computational aesthetics are also good at speculating on what viewers might expect or prefer to see (Arielli and Manovich Reference Arielli and Manovich2024). Auntieverse’s aesthetic choices, whether intentional or algorithmically generated, serve as a reminder of the existing biases within cultural narratives around ageing, especially for the current generation of older women who have lived through significant societal shifts. In addition, it is crucial to remind ourselves not to blame all discrepancies between artist intent and audience interpretation on AI, as non-AI art also more than often passively confronts or actively invites distinctive interpretations.

This intertwining of artist’s agency and AI influence makes Auntieverse both complex and captivating. Some viewers questioned whether the visuals genuinely reflected Lim’s artistic voice or if they were merely algorithmic artefacts. Our younger participants were more open to the AI-generated style, appreciating its bold and eye-catching quality, particularly within the context of social media. Given Auntieverse’s social media presence, its vibrant and sometimes controversial imagery became a catalyst for reflection and debate – showing that AI art’s ability to activate conversation is itself a step towards reshaping cultural narratives around ageing.

To truly ‘repAInt’ successful ageing, it is crucial for artists to actively balance the algorithmic creative agency with their own and for the audience to critically participate in the meaning-making process. Much like a funhouse mirror, AI has the ability to show us not only what is real but also what might be possible. The challenge lies in using this reflective surface not only to amplify existing narratives but also to uncover new perspectives on ageing. Auntieverse might not be a perfect answer for how to envision successful ageing through AI art, but it serves as a fascinating example which delivers complex visual messages that invite us to rethink the stories and values that define what it means to age well.

Limitations

This study’s qualitative approach focused on unfolding narratives and identifying valuable insights, with Study 3 involving a small sample size of five participants, all from middle-upper-class backgrounds. This limited demographic scope may have affected the diversity of perspectives, particularly regarding socio-economic influences on perceptions of ageing. Researcher bias was also a potential limitation, as audience interviews were conducted after the artist interview, raising the risk of influencing participant responses. To mitigate this, the interviewer maintained a neutral tone, avoided defending the artist’s choices and encouraged open expression. Besides, the study’s cultural specificity may have limited its applicability to broader international audiences. Finally, while Auntieverse exclusively depicts older female figures, this study does not explicitly engage with gender issues or feminist scholarship, as doing so would have overcomplicated the primary research focus.

Conclusion

This study addresses a critical gap in understanding AI art’s role in shaping cultural narratives of ageing. Through the Auntieverse case study, we demonstrate that AI-generated representations of ageing are not passive reflections of reality but active sites of meaning-making, shaped by algorithmic aesthetics, artistic intent and audience interpretation. While Auntieverse reimagines ageing through radical and visually striking depictions, our findings reveal that the re-rendering of ageing is subject to a complicated negotiation between artistic intent, AI-generated aesthetics and audience interpretation. This article thus situates AI art within broader discussions on representation, identity and digital culture, emphasizing its role not just in creative experimentation but in influencing how ageing is conceptualized and visualized in contemporary society.

As AI increasingly mediates cultural representation, it is essential to critically assess its influence on identity, agency and social belonging. Future research could explore how AI-generated ageing imagery is perceived by diverse demographic groups, including older adults and digital natives, who play an important role in fostering intergenerational understanding. To support systematic analysis, scholars may develop culturally grounded frameworks to evaluate AI-generated images of ageing, as well as apply quantitative methods to explore their psychosocial and societal impacts. Beyond academic discourses, it would also be productive to create interdisciplinary and participatory spaces through community-based programmes or industry collaborations, so that AI engineers, artists, cultural scholars and older adults can co-develop more inclusive narratives of ageing that reflect bottom-up perspectives. At the policy level, ethical guidelines for AI-based cultural production may also help ensure socially responsible representations and contribute to more inclusive cultural narratives. Moving forward, rather than viewing AI in binary terms of utopia or dystopia, we advocate for engaging in ongoing enquiry and critique to navigate its potential for cultural transformation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X25100445.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to Dr. Takao Terui for his insightful feedback and to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable constructive suggestions that significantly contributed to the development of this paper. We are deeply appreciative of the artist Niceaunties, whose work served as the inspiration for this research. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to the anonymous participants who generously shared their time, experiences, and reflections. We also gratefully acknowledge the “Seed Fund” provided by the University Research Centre for Culture, Communication, and Society at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University. The research underpinning this article was presented at the 2025 International Health Humanities Conference, which was held at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University.

Financial support

This research was supported by Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University under Grant RDF-23-01-54.

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

This research was approved by the Department Ethics Review Committee, Department of Communications and New Media, National University of Singapore (Approval No. 20250123). No additional IRB review was required for this project.