Introduction

In 2010, the Workers’ Party (PT, Partido dos Trabalhadores) launched Rousseff’s presidential candidacy with an eye on extending its streak of presidential election victories in Brazil. In order to increase its candidate’s odds, the PT built a broad pre-electoral coalition, encompassing not less than ten parties. However, even if the PT ultimately won the presidential contest, not all pre-electoral coalition party members were invited to take a seat in the cabinet when Rousseff was sworn into office. Despite still providing informal support for the government, the Social Christian Party (PSC, Partido Social Cristão) publicly voiced its dissatisfaction with being excluded from the coalition cabinet. The PSC’s party leader emphatically complained that they did not have a single portfolio seat despite being a former member of the pre-electoral alliance and having a legislative seat share similar to other coalition party members (Azevedo, Reference Azevedo2012).

In a similar story, the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR, Movimiento de la Izquierda Revolucionaria) formed a pre-election alliance so as to back its candidate in the 1989 Bolivian presidential election. Once again, notwithstanding the alliance’s victory, the president-elect party broke up with the pre-electoral pact and gave birth to a government not envisioned by the original multiparty coalition. This case is especially symbolic as the MIR did not assign any top office position to former pre-electoral coalition party members, thereby favouring the construction of a brand-new post-electoral coalition arrangement.Footnote 1

Together, these cases raise the question as to what drives the translation of pre-election alliances into coalition governments in multiparty presidential democracies. This question features prominently as the literature frequently adopts an unexamined assumption that pre-electoral coalitions are automatically transformed into coalition cabinets. Even though pre-electoral coalitions exert notable influence on the government formation process (Borges, Turgeon and Albala, Reference Borges, Turgeon and Albala2021; Carroll, Reference Carroll2007), recent scholarship has argued that, at least in presidentialism, the process from electoral alliances to cabinet formation is not as straightforward as it seems (Couto, Reference Couto2025). Hence, the main aim of this study is to contribute to this burgeoning literature by unpacking the reasons as to why some coalition governments closely match the pre-electoral pacts that brought them forth while others do not.

Studying the process by which pre-election coalitions are turned into coalition cabinets is pertinent for several reasons. Looking at non-formateur parties first, their strategies rely to some extent on knowing whether they will be in the government. Even though parties have different approaches to making their organizations grow (Borges, Albala and Burtnik, Reference Borges, Albala and Burtnik2017; Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988), pre-election coalition party members may be counting on the fact that they will have access to the spoils of office if the pre-election alliance succeeds in the national contest. As such, being excluded from the government potentially undermines parties’ objectives in the short and long run, especially if they aimed to control portfolios to channel pork-barrel resources to their constituencies (Batista, Reference Batista2023; Meireles, Reference Meireles2024) or expected to hold a highly regarded portfolio, which could have boosted their votes in the next elections in return (Batista, Power and Zucco, Reference Batista, Power and Zucco2024). In addition, although elected governments have plausible reasons for not deviating grossly from policy commitments made prior to the elections (Kellam, Reference Kellam2017; Naurin, Soroka and Markwat, Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019), government membership increases parties’ chances of making policies close to their preferences. The experience of coalition governments in parliamentary democracies tells us that parties may even use the portfolio allocation process to keep tabs on which policies are to be implemented by the government (Fernandes, Meinfelder and Moury, Reference Fernandes, Meinfelder and Moury2016), and there is no reason why this should not be replicated in presidential democracies. As a result, even if parties can resort to alternative methods to promote the oversight of the government’s policy-making (Silva and Medina, Reference Silva and Medina2023; Thijm and Fernandes, Reference Thijm and Fernandes2024; Thijm, Reference Thijm2024), losing cabinet participation can have deleterious consequences for pre-electoral coalition parties when it comes to the degree to which the policy-making process is attuned to their policy preferences. On the other hand, understanding why formateurs stick to their pre-electoral coalitions contributes to the stream of studies interested in gauging to what extent presidents use their institutional powers for their own benefit (Ariotti and Golder, Reference Ariotti and Golder2018; Silva, Reference Silva2023).

I argue that the extent to which coalition cabinets resemble pre-electoral coalitions depends on the blend of five conditions: (i) the pre-electoral coalition’s legislative status, (ii) the level of polarization within pre-electoral coalitions, (iii) the ideological polarization in the legislature, (iv) the temporal constraint between election results and the inauguration day, and (v) presidents’ constitutional powers. In doing so, my claim draws on several but different theories of government formation, namely explanations based on office, policy, and institutional assumptions. In this way, I draw on diverse streams of research to further add to the discussion about when and why presidents and their parties honour their office commitments to pre-election coalition partners.

To do so, this paper subscribes to a configurational approach to studying the government formation process in multiparty presidential democracies. To be sure, research on coalition cabinets based on set-theoretic methods is not uncommon in the literature (e.g. Albala, Reference Albala2021; Viatkin, Reference Viatkin2023). Even still, it bears noting that set theory appears to be especially suitable here for three reasons. In the first place, past scholarship has shown that the influence of pre-electoral coalitions on government formation is conditioned by at least one other factor, namely, legislative polarization, in Latin America (Couto, Reference Couto2025). This suggests that the craft of coalition cabinets – especially when factoring in pre-electoral coordination – comes from the confluence of factors rather than the predominance of any single isolated element. Notably, this goes hand in glove with one of the primary goals of qualitative comparative analysis (henceforth, QCA): to capture the combinations of conditions that account for a given outcome (Rönkkö, Maula and Wennberg, Reference Rönkkö, Maula and Wennberg2025). Second, the use of QCA allows me to conduct a case-centred research and bring case knowledge to help unpack what makes post-electoral coalitions congruent with their pre-electoral strategies. Substantially, this case-based perspective offers insights that are elusive to the traditional large-N studies, where the process of learning from cases usually does not feature in the spotlight (e.g. Albala, Borges and Silva, Reference Albala, Borges, Silva, Dumont, Grofman, Bergman and Louwerse2024). Third, employing a set-theoretic method provides me with flexibility to derive a theory-guided case selection. In contrast to purely quantitative research, I purposefully select on the dependent variable to ensure that all cases derive from pre-electoral coalition formation and result in multiparty governments, thus fully aligning theory with empirical scrutiny.

I start in the next section by briefly presenting the literature on government formation in presidentialism and raising empirical expectations to explain the similarity between coalition cabinets and their pre-electoral conception. Thereafter, the third section showcases my research design. More specifically, this section is divided into three parts, in which I first discuss the advantages of QCA to the study of coalition formation, then I detail my case selection, and lastly, I show the calibration process of the outcome and the conditions. In the fourth section, I conduct and reveal the results of necessity and sufficiency analyses. The fifth section briefly refers to the robustness tests, and the sixth illustrates the QCA findings with case-based discussions. Finally, the last section presents my concluding remarks along with suggestions for future research.

The high road between pre-electoral coalitions and coalition cabinets

In presidential and parliamentary democracies alike, formateur parties do not easily attain a parliamentary majority on their own in fragmented party systems. Not coincidentally, coalition governments have become increasingly more common in European parliamentary democracies (Müller, Bäck and Hellström, Reference Müller, Bäck and Hellström2024). Likewise, in recent years, multiparty governments have emerged in presidential democracies that were historically ruled by single-party governments, such as Costa Rica (Hernández-Naranjo and Guzmán-Castillo, Reference Hernández-Naranjo, Guzmán-Castillo, Camerlo and Martínez-Gallardo2018). In such a context, cabinet management arises as one of the main tools available to presidents for securing a legislative majority and, therefore, preventing troublesome deadlocks in the legislature (Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power, Reference Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power2018; Chasquetti, Reference Chasquetti and Lanzaro2001; Cheibub, Reference Cheibub2007). Pre-election coalitions, in particular, help presidents in building their cabinets (Borges et al., Reference Borges, Turgeon and Albala2021; Carroll, Reference Carroll2007).

Nevertheless, pre-election coalition parties do not always grant a legislative majority to the president-elect in both chambers of the legislature. For this reason, it is not unusual for presidential parties to strive to increase their coalition’s share of seats in the aftermath of elections (Albala, Reference Albala2017). More generally, this process falls under the umbrella of the coalition bargaining process: the president-elect’s party opens or reopens negotiations with the remaining parties that have legislative representation to broaden the government’s breadth in the legislature. Importantly, this process is beneficial for both presidential parties and future coalition partners. On the one hand, as mentioned above, cabinet participation is a golden opportunity for parties to push their goals related to office, policy, and vote. On the other hand, presidents remove an obstacle – the lack of support in the legislature – for advancing their policy agenda. Moreover, as coalition governments rarely produce and publicly disclose written coalition agreements in a multiparty presidential context, policy bargaining in the government formation process is seldom plagued by the process of setting down the terms of the coalition compromise, as is the case in parliamentary democracies (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Angelova, Bäck and Müller2024; Moury, Reference Moury2013). Although this may incur some costs for governance later, it represents one less concern at the bargaining table in the lead-up to the new administration.

Against this backdrop, the expectation is that the composition of post-electoral governments should differ from that of pre-electoral pacts when the latter falls short of securing a minimal winning coalition. Reversing the argument, formateur parties ought not to look out for new partners when pre-electoral coalition members successfully help the presidential party to hold a majority in the legislature. By adopting a purely office-seeking premise, this happens as none of the parties would be willing to share the spoils of being in power with parties that are needless in terms of securing enough legislative support for the government (Leiserson, Reference Leiserson1966; Riker, Reference Riker1962).

Yet, as parties have other motivations beyond attaining office, the majority status of pre-electoral coalitions is hypothesized as a causally relevant factor, though not sufficiently to explain why coalition cabinets build on their pre-election coalitions. This is not only in line with the combinatorial logic of configurational comparative methods, but also does justice to the existence of different motivations that guide the behaviour of politicians, such as the promotion of their policy interests (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1970). In other words, the majority granted to the government by pre-election coalition members is a prime example of an INUS condition, where the condition is neither necessary nor sufficient to bring about the outcome on its own, but it is nevertheless an indispensable part of a specific combination that accounts for the outcome (Mello, Reference Mello2021).Footnote 2

H1: Majority pre-electoral coalitions operate as INUS conditions to yield coalition cabinets with a similar composition relative to their pre-electoral composition.

High within pre-electoral coalition polarization is another potential trigger for changes in the composition of pre-electoral alliances in their way of forming coalition governments. Even if parties tend not to coalesce when the ideological distance among them is significant (Kellam, Reference Kellam2017), some pre-electoral alliances are still composed of parties from different ends of the political spectrum (Indridason, Reference Indridason2011). When this happens, pre-electoral coalition members potentially disagree over several issues on coalition governance, such as who gets which portfolio, which policy is to be prioritized, and whether and which party should be invited to be part of the coalition cabinet. As a consequence, a heightened level of ideological polarization may ultimately lead to the fracture of pre-election pacts, while a limited ideological disagreement at the party level may account for coalition cabinets that preserve their pre-election foundation.

Crucially, however, the government formation stage does not revolve exclusively around policy congruence among eventual governing parties. As discussed above, concerns about the government seat share, among other conditions, come into play in coalition formation. Thus, I also expect ideological homogeneity among pre-election coalition partners to contribute to forming coalition governments grounded in their pre-election roots, but I do not expect it to paint the whole picture.

H2: Low within pre-electoral coalition polarization is an INUS condition to render coalition cabinets similar to their pre-electoral origins.

Turning to the party system level, Couto (Reference Couto2025) has recently argued legislative polarization – the weighted distance between parties in the policy space – moderates the extent to which pre-electoral coalitions influence government formation. In a similar vein, I argue here that legislative polarization also plays a role in the process of pre-electoral coalitions turning into coalition cabinets. The key point is that lower levels of legislative polarization make multiparty bargaining more straightforward for formateur parties insofar as they have more leeway to break from the pre-electoral alliance if they wish to do so. That is, when ideological differences among parties are not pervasive, formateur parties have more incentives to build coalition cabinets that push forward their office and policy interests, even if it comes at the expense of cabinet membership for former pre-election coalition partners. Contrariwise, parties’ ideological placements far apart in the party system make bargaining dynamics beyond pre-electoral commitments increasingly costly, as presidents might struggle to accommodate office and policy priorities from other parties. Under these circumstances, presidential parties have an extra incentive to stick with their pre-election partners.

Nevertheless, I claim that legislative polarization does not influence government formation in isolation; that is, it should matter only if accompanied by other conditions. To see how this is the case, consider a pre-electoral coalition in a context where parties are not too ideologically different from one another. Even though the presidential party arguably has more freedom to choose whom to ally with in this scenario, why would it change the composition of the pre-electoral alliance in the first place? Conversely, if formateur parties have an underpinning reason to sever ties with (or to keep) their original pre-electoral commitments, legislative polarization should facilitate (or complicate) the endeavours of formateur parties.

In summary, as with the other hypotheses, the expectation is that legislative polarization relates to the similarity between pre-electoral pacts and coalition cabinets in multiparty presidential democracies. That said, in the absence of complementary conditions, legislative polarization would be of little use in influencing government formation. Thus:

H3: Elevated levels of legislative polarization are an INUS condition to the similarity between coalition cabinets and their pre-electoral predecessors.

One of the main characteristics of presidential regimes is that presidents serve constitutionally fixed terms, thereby not being responsible to an elected assembly (Cheibub, Reference Cheibub2007; Samuels and Shugart, Reference Samuels and Shugart2010). Based on this, the literature draws attention to the fact that constitutional or electoral rules clarify when the presidents’ term in office must come to an end. However, scholars more often than not overlook that the same institutions are also explicit when presidents are to be sworn into office (Albala, Reference Albala2017). That is, presidential regimes, unlike their parliamentary counterparts (Ecker and Meyer, Reference Ecker and Meyer.2015; Golder, Reference Golder2010), cannot have several rounds of multiparty bargaining before the formateur gets into office because there is a temporal bound between the conclusion of the electoral process and the handover of power to the next government.

Overall, institutional claims have found mixed support in research on coalitional presidentialism (Amorim Neto, Reference Amorim Neto2006; Freudenreich, Reference Freudenreich2016). Still, past scholarship has pointed out that pre-electoral pacts are influenced by institutional settings (Ferrara and Herron, Reference Ferrara and Herron2005; Spoon and West, Reference Spoon and Jones West2015). In this way, I argue that the time span between the electoral period and the inauguration day influences the extent to which coalition cabinets resemble their pre-electoral pacts. A shorter distance constrains the president-elect’s parties from drastically changing coalition members, encouraging them to build the government around pre-electoral alliances. By contrast, a longer distance between elections and the inauguration day allows presidents to think more carefully about the composition of their government.

However, again, we should not expect presidents to change the partisan composition of their coalition arrangements just because they have fewer constraints to do so. This is similar to legislative polarization. Just as ideological polarization is not expected to be entirely responsible for changes in coalition configurations, neither is a short temporal distance before the president-elect assumes office. Hence, I theorize that this time-related boundedness is one component of a broader chain to cause post-election coalition cabinets to bear a resemblance to their pre-election commitments. As such:

H4: A short distance between the end of the electoral process and the president’s first day in office is an INUS condition to the alikeness between pre-electoral alliances and subsequent coalition cabinets.

As the last piece of the puzzle, the transition of pre-electoral pacts to coalition cabinets may also be contingent on the extent to which presidents are granted tools to promote the governability of their governments. Indeed, previous empirical studies have shown that presidential powers influence overall patterns of coalition formation (Amorim Neto, Reference Amorim Neto2006; Mart nez-Gallardo, Reference Martínez-Gallardo2012; Silva, Reference Silva2023). More specifically, presidents with extensive formal prerogatives may care less about fulfilling office pre-electoral commitments than those without such powers. This is because the former can appoint their ministers without major trouble and still govern by issuing decree-laws, dictating legislative agenda, or vetoing undesired bills, while the latter must come to terms with the legislature to avoid getting into a collision course and guarantee successful passage of policy.

This should especially be the case for the transition period between pre-electoral coalitions and the formation of coalition cabinets, as presidents are prone to enjoy the honeymoon in their first year in office, thus further discouraging constitutionally weak presidents from disturbing executive-legislative relations at the outset of their term. Given the high stakes in this regard, unlike the previous hypotheses, low presidential powers should lead to congruent post-election coalitions regardless of the other constellation of conditions:

H5: Low presidential powers are sufficient for engendering coalition cabinets similar to the pre-electoral pacts that preceded them.

Research design

To evaluate the claims around the process by which pre-electoral coalitions become coalition cabinets, I make use of QCA. In broad terms, QCA is a set-theoretic method and technique which aims to approximate variable- and case-oriented approaches (Berg-Schlosser et al., Reference Berg-Schlosser, Meur, Rihoux, Ragin, Rihoux and Ragin2009; Ragin, Reference Ragin2008; Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). By doing so, QCA puts cases in the limelight while also allowing the detection of empirical patterns in a cross-case fashion (Mello, Reference Mello2021).

In the scholarship, the primary motivation for applying QCA lies in the fact that it provides further leverage for causal claims by allowing researchers to explore causal complexity. In this study, I am particularly interested in grasping the conjunctural causation involved in government formation under presidentialism. That is, I rely on QCA to investigate which combinations of conditions credibly cause the outcome under study (i.e. coalition resemblance across pre- and post-election periods). Thus, in line with most of the empirical expectations derived in the last section, the primary analysis lens falls on the co-occurrence of conditions rather than the existence of individually sufficient conditions.Footnote 3

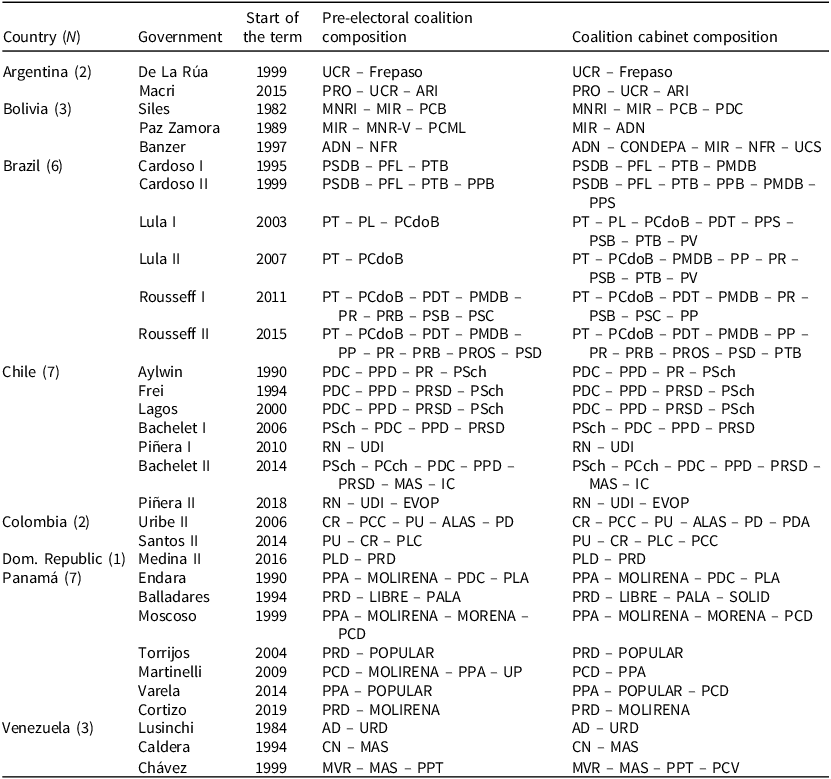

My case selection is slightly particular, as I deliberately select, in varied ways, my observations based on the dependent variable. Despite being a criticized approach following the standards of conventional quantitative literature (Geddes, Reference Geddes2003; King, Keohane and Verba, Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994), this strategy makes sense depending on the researcher’s aims (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). In this study, I do not intend to generalize my findings to all instances of government formation in Latin America. Rather, I am most concerned with coalition cabinets derived from pre-electoral alliances. Given that most coalition governments originate from some sort of multiparty pre-electoral coordination in multiparty presidential democracies (Albala and Couto, Reference Albala and Couto2023), this research design still enables me to cover a substantial portion of the coalition cabinets formed in Latin America. Moreover, I ensure conceptual consistency by studying specifically coalitional arrangements. This happens as I remove pre-electoral coalitions that culminate in single-party governments from the analysis. In so doing, I certify that my outcome, namely, the correspondence between pre- and post-electoral coalitions, remains grounded throughout the process by which coalition partners pass through the electoral period. Otherwise, the underlying conceptual validity is severely put into question. In the Supplementary Material, I discuss in greater detail which other cases are left out of the analysis, such as exclusively electoral coalitions. Table 1 presents the pre- and post-electoral coalition composition of the 31 cases to be analysed in this paper.

Table 1 Pre- and post-electoral governments in Latin America

Source: Amorim Neto (Reference Amorim Neto and Ames2019); Borges et al. (Reference Borges, Turgeon and Albala2021); Freudenreich (Reference Freudenreich2016); Lopes (Reference Lopes2022); Silva (Reference Silva2023); and the countries’ respective electoral committees.

The calibration process of the conditions and the outcome provides the basis for QCA analyses. As a set-theoretic method, the calibration accounts for whether cases are in or out of a given set. Notwithstanding the proliferation of QCA variants in recent years (Mello, Reference Mello2021), QCA has three more well-known specifications (crisp-set QCA, multi-value QCA, and fuzzy-set QCA), each holding specific ways for calibrating conditions (Medina et al., Reference Medina, José Castillo-Ortiz, Concha and Rihoux2017). The fuzzy-set QCA (henceforth, fsQCA) is the most suitable QCA variant for current purposes. The reason for this is that the fsQCA allows us to consider to what extent cases belong to a set by inputting a continuous value membership between 0.0 and 1.0 (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). This, in turn, gives us the upper hand in using more fine-grained information to capture more complex concepts, such as coalition resemblance and legislative polarization. Below, I briefly discuss the decision-making process to calibrate conditions and the outcome.Footnote 4

To begin with, the outcome Coalition Resemblance captures to what extent coalition cabinets are similar to the pre-electoral coalitions that preceded them. To calculate membership in the outcome, I take into account the seat share that pre-electoral coalition members contribute to the coalition’s total seat share in the lower house. In this measure, I disregard the president-elect party’s legislative contingent, as very few presidential parties fail to acquire cabinet membership in the upcoming government (Amorim Neto, Reference Amorim Neto1998). If formateur parties’ share of seats had remained in the calculation in the first place, Coalition Resemblance would have inflated values and, thus, unduly lessen the contribution of the other pre-electoral coalition members to the governing coalition.

Overall, this measure is very similar to the one developed and employed by Albala, Borges and Couto (Reference Albala, Borges and Couto2023) to study the effects of pre-electoral coalitions on cabinet duration in Latin America. In fact, this measure is straightforward if coalition cabinets (i) keep the same partners from the electoral period or (ii) are enlarged to include additional partners. However, this calculation fails to take into account coalition reductions, as pre-electoral coalition members would still account for all the coalition’s share of seats. In order to hold a holistic view of all the possible changes a pre-election alliance can undergo, I slightly modify the formula to also factor in such occurrences by inverting the relationship between pre-election and coalition cabinets. That is, when pre-electoral coalition members are expelled from the coalitional pact, I calculate what is the proportion of the post-electoral coalition cabinet’s share of seats relative to the total share of seats pre-election coalitions would have if their composition had not changed.Footnote 5

Depending on the nature of the modification, the formula for Coalition Resemblance is, then, the combined share of seats of pre-election coalition members in relation to the coalition’s overall share of seats, or the other way around, as given by the following formula:

$${\rm{Coalition\;Resemblance}} = \left( {{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^p {\rm{PE}}{{\rm{C}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^c {\rm{Cabine}}{{\rm{t}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}}} \vee {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^c {\rm{Cabine}}{{\rm{t}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^p {\rm{PE}}{{\rm{C}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}}}} \right)$$

$${\rm{Coalition\;Resemblance}} = \left( {{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^p {\rm{PE}}{{\rm{C}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^c {\rm{Cabine}}{{\rm{t}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}}} \vee {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^c {\rm{Cabine}}{{\rm{t}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^p {\rm{PE}}{{\rm{C}}^{\rm{'}}}{\rm{s\;Seat\;Share}}}}} \right)$$

where p is the number of pre-election coalition members and c corresponds to the total number of coalition partners in the post-election scenario. Presidential parties are excluded from the equation.

Regardless of whether or how pre-election coalitions change from one period to another, full set membership in Coalition Resemblance indicates that coalition cabinets thoroughly resemble pre-electoral coalition members. Meanwhile, full non-membership embodies coalition cabinets and pre-electoral coalitions that are entirely different from one another.

Moving on to explanatory conditions, Majority refers to whether pre-electoral coalitions hold a legislative majority after the election results. To belong to this set, I consider that pre-election coalitions should have at least a semi-majority (more than 45% of the share of seats) in one of the legislative chambers. Importantly, given the existence of ‘parties-for-hire’ across Latin America (Kellam, Reference Kellam2015), this threshold takes into account that presidents and their governing coalitions can still govern even if they do not secure a clear majority in the legislature. This is possible through the formation of ad hoc legislative majorities on individual pieces of legislation, in which presidents guarantee the passage of government policy by making use of their toolbox (Chaisty et al., Reference Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power2018; Raile, Pereira and Power, Reference Raile, Pereira and Power2011), such as through the management of budgetary transfers for pork-barrel politics (Bertholini and Pereira, Reference Bertholini and Pereira2017; Pereira, Bertholini and Melo, Reference Pereira, Bertholini and Melo2023) and partisan appointments in the bureaucracy (Bersch, Lopez and Taylor, Reference Bersch, Lopez and Taylor2023). In this circumstance, cases are assigned a 0.6 score, while cases with a larger seat share receive higher set membership scores. Conversely, pre-electoral pacts that fail to reach at least a semi-majority are more outside than inside Majority and, accordingly, receive lower scores according to their seat share.

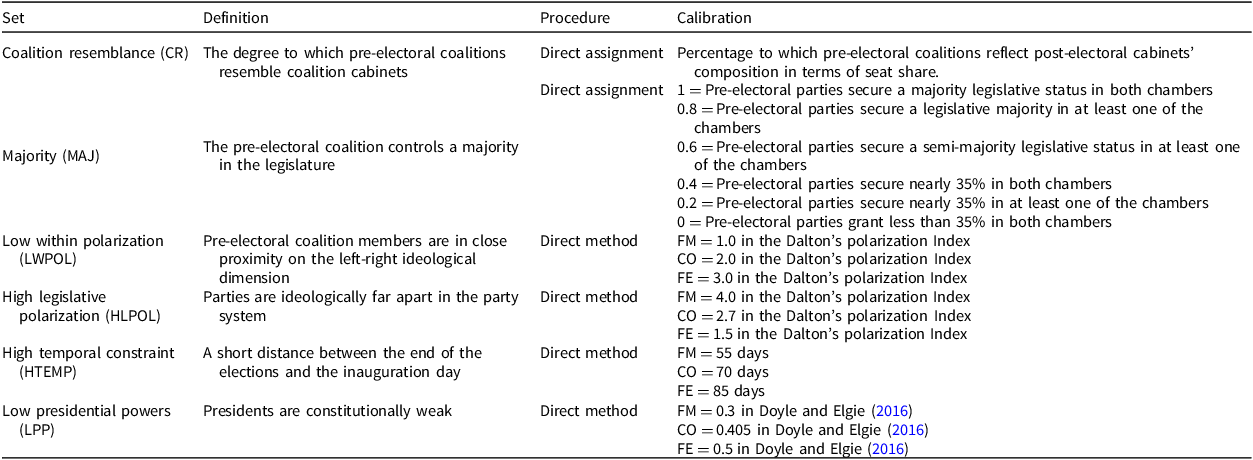

Next, Low Within Polarization refers to the weighted ideological distance between pre-election coalition members, whereas High Legislative Polarization captures the ideological polarization in the legislature. The qualitative anchors across both sets are not exactly reversed to one another, albeit they are based on the same polarization index developed by Dalton (Reference Dalton2008). This happens because legislative polarization naturally tends to be higher than polarization found within pre-electoral alliances. The former includes all parties in party systems, including extremist parties, whereas the latter often revolves around parties with similar ideological preferences (Kellam, Reference Kellam2017).

High Temporal Constraint corresponds to the distance, in days, between the election day and the day presidents are sworn into office. The empirical anchors of this set are established mostly by looking at observed patterns found in the data, since the time lapse that separates the end of elections from the beginning of a new government in presidential democracies has not been profoundly studied yet. Most importantly, since second-round presidential elections cannot logically result in lower temporal constraints for the president-elect compared to first-round elections, the crossover point is set at 70 days. This places most cabinets preceded by run-off elections as being inside the set, with the exception of the Argentine cases and Bachelet II and Piñera II in Chile. Set full membership is defined as 55 days, which is equivalent to a one-and-a-half-month period, whereas full exclusion is set at 85 days, a relatively long period even by the standards of parliamentary democracies (Golder, Reference Golder2010).

At last, Low Presidential Powers is associated with the degree to which presidents are powerful actors in the political system. While indices of presidential powers abound, the calibration rests specifically on Doyle and Elgie’s (Reference Doyle and Elgie2016) measurement. This is so because this measure considers presidential powers as a whole instead of focusing on a single dimension. For example, rather than using decree and veto powers as proxies for presidential powers, this measure encompasses all presidential prerogatives, such as the presidents’ capability to introduce bills, appoint, dismiss and retain ministers at their own discretion, apply for judicial review, and so on. To locate empirical anchors, I once again rely mostly on empirical gaps found in the data, positioning full membership at 0.3 and full exclusion from the set at 0.5. However, the cross-over point is specifically set at 0.405. This ensures that the Dominican and Venezuelan cases are in the reference set.Footnote 6 The assignment of the Dominican case follows the discussion that, though historically strong (Belén Sánchez and Lozano, Reference Sánchez, Benito and Lozano2012), presidential powers are in decline (Marsteintredet, Reference Marsteintredet, Albert, O’Brien and Wheatle2020) and presidents do not boast control over their cabinets to the same degree as other presidents in the region (Araújo, Silva and Vieira, Reference Araújo, Silva and Vieira2016). As for Venezuela, this relates to the constitution endowing presidents with formally limited powers in the country at the time (Crisp, Reference Crisp, Mainwaring and Soberg Shugart1997; Shugart and Carey, Reference Shugart and Carey1992).

To summarize, Table 2 provides an overview of the conditions and the outcome, as well as the respective procedures for calibration and the rules for the calibration process.

Table 2 Overview of the calibration of the outcome and the conditions

Source: Borges et al. (Reference Borges, Lloyd and Vommaro2024); Dalton (Reference Dalton2008); Doyle and Elgie (Reference Doyle and Elgie2016); Freudenreich (Reference Freudenreich2016); Silva (Reference Silva2023); and the countries’ respective electoral committees.

Note: FM stands for full membership in the set, CO for cross-over point, and FE for full exclusion in the set.

Empirical analysis

The empirical analysis of configurational comparative research is based on statements of necessity and sufficiency. In short, necessary conditions are indispensable for the occurrence of the outcome (Ragin, Reference Ragin2008). In turn, sufficient conditions are capable of producing the outcome on their own (Medina et al., Reference Medina, José Castillo-Ortiz, Concha and Rihoux2017; Mello, Reference Mello2021).

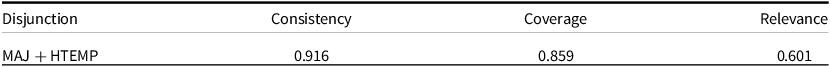

Unless the interest lies in finding minimally necessary disjunctions of minimally sufficient combinations (Haesebrouck and Thomann, Reference Haesebrouck and Thomann2022), QCA empirical analysis operates analyses of necessity and sufficiency separately. In order not to produce untenable assumptions in the analysis of sufficiency, it is advisable that the analysis of necessity must be conducted in advance (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). In the analysis of necessary conditions, the literature argues that a 0.9 consistency threshold and a 0.6 relevance of necessity score should be in place to find meaningful non-trivial necessary relations between conditions and the outcome (Oana, Schneider and Thomann, Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021; Schneider, Reference Schneider2018; Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). By applying these recommendations, Table 2 shows the results of the analysis of necessary conditions for the resemblance of post-electoral coalition governments vis-à-vis their pre-electoral configuration.

The necessity test in Table 3 indicates that only a single combination of conditions is necessary to explain the commonalities between pre-electoral pacts and post-electoral governments. The analysis reveals that either achieving a majority status (MAJ) or facing a short period until the government is officially set in motion (HTEMP) is pivotal for a strong similarity between pre- and post-electoral coalitions.Footnote 7

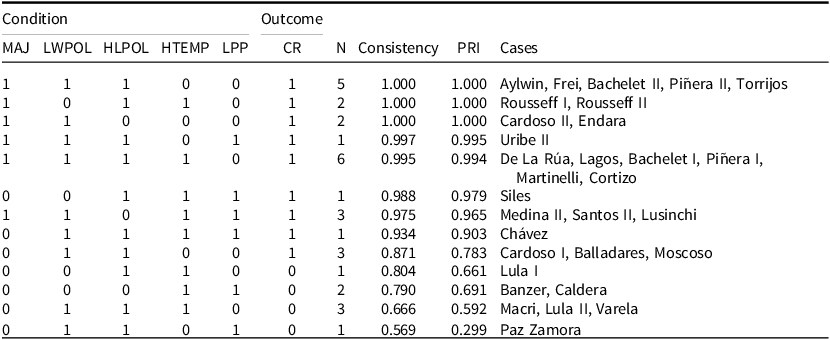

Closely following the necessity test, the next stage in a typical QCA framework involves engaging in sufficiency analysis. Much of the analysis of sufficient conditions boils down to the construction of the truth table and its subsequent minimization process. The reason for this is that the truth table systematically organizes all possible combinations of conditions into distinct rows, assigns empirical cases to each row according to the cases’ degree of membership to every set, and shows the extent to which each row exhibits a sufficient relationship with the outcome. Then, based on the information in the truth table, the minimization process is charged with applying Boolean algebra to generate a ‘recipe’ that supposedly explains the outcome of interest.

Recall that the previous sections devised five empirical expectations to account for the convergence between pre-electoral coalitions and their post-electoral heirs, and that this resulted in the creation of five explanatory conditions. Against this backdrop, the truth table for coalition resemblance generates 32 logically possible combinations, as the number of rows in a truth table is given by

![]() ${2^n}$

, where n is the number of conditions in the study. As listed in Table 4,Footnote

8

the empirical instances are distributed along 13 configurations, with all the remaining rows representing logical remainders,Footnote

9

which have been omitted for ease of interpretation. As a result, since logical reasoning provides a far greater number of possible combinations than those that actually exist in the real world, the present sufficiency analysis is confronted with limited diversity (Ragin and Sonnett, Reference Ragin, Sonnett and Ragin2008).

${2^n}$

, where n is the number of conditions in the study. As listed in Table 4,Footnote

8

the empirical instances are distributed along 13 configurations, with all the remaining rows representing logical remainders,Footnote

9

which have been omitted for ease of interpretation. As a result, since logical reasoning provides a far greater number of possible combinations than those that actually exist in the real world, the present sufficiency analysis is confronted with limited diversity (Ragin and Sonnett, Reference Ragin, Sonnett and Ragin2008).

Table 3 Necessity test for coalition resemblance

Note: In configurational rationale, the sign ‘+’ is equivalent to the logical OR.

Table 4 Truth table for coalition resemblance

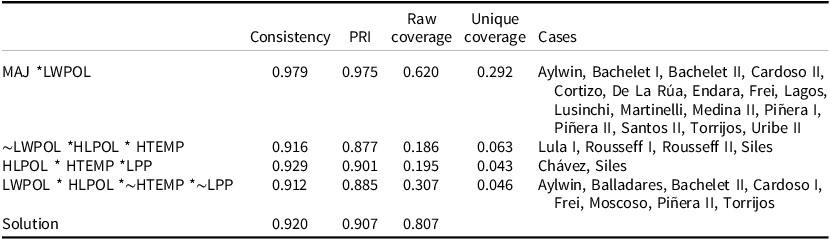

Table 5 Enhanced intermediate solution for coalition resemblance

However, as limited diversity is ubiquitous in empirical research, QCA does have some remedies for treating logical remainders. All in all, the answer lies in the different ways to handle them in the minimization process. Here, I opt for partially including logical remainders in the logical minimization of the truth table. More specifically, while difficult counterfactuals are dismissed, easy counterfactuals – logical reminders in line with theoretical and substantive knowledge (Dusa, Reference Dusa2019, Chap. 8; Ragin, Reference Ragin2008, Chap. 9) – are included in the analysis. Accordingly, the counterfactual analysis allows including educated hunches in the sufficiency test on what would have possibly occurred had the empty truth table rows had empirical cases. Hence, as only a fraction of the counterfactuals is in the minimization process, the analysis of sufficient conditions rests on the intermediate solution.Footnote 10

As the final steps before assessing set relations based on sufficiency, I employ the enhanced standard analysis (ESA) to minimize the truth table, given the existence of a necessary disjunction. I also set the inclusion score for consistency at 0.8, a value slightly above the bare minimum 0.75 consistency threshold recommended by the literature (Mello, Reference Mello2021, Chap. 6; Ragin, Reference Ragin2008, Chap. 3). Furthermore, the directional expectations have the exact directions as the hypothesized conditions, such as Majority is expected to lead to coalition resemblance, as does Low Within Polarization and so forth. Coupled with the previous features, this settings leads to an analysis of sufficiency that produces four causal pathways to account for Coalition Resemblance, as shown in Table 5.

The first path indicates that pre-electoral coalitions that hold a legislative majority and consist of parties with similar policy preferences make coalition cabinets to be heavily based on their pre-election antecessors. To attest to the prominence of this configuration, it has the highest scores for consistency and raw coverage, in addition to uniquely covering several pre-election coalitions that ultimately led to governing coalitions. This path, thus, provides sound supportive evidence for the notion that formateur parties work towards preserving pre-electoral pacts that grant a majority in the legislature to the government and are simultaneously ideologically coherent.

Next, the second path highlights the combination of ideological heterogeneity within the pre-electoral pact, high legislative polarization and a short period until the government’s first day in office to the conversion of pre-electoral pacts into coalition governments. Similarly, high legislative polarization and high temporal constraints are also components of the third path. The difference resides in the fact that, instead of low within polarization, Path 3 envisions that this configuration occurs in tandem with constitutionally weak presidents.

The last pathway poses an intriguing combination. It tells us that, even facing a considerable time until official government formation and with constitutionally moderate to strong presidents, pre-electoral alliances serve as a basis for post-electoral governments when the party system they are embedded in is highly polarized, but their coalition members hold ideologically similar policy views. This combination is particularly noteworthy for severely threatening the necessary claim between coalition resemblance and the disjunction between Majority and High Temporal Constraint.

Together, the four paths yield an overall solution formula with a high consistency score of 0.920 and a significant proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) of 0.907, covering roughly 80% of the cases in the analysis. These scores amount to a solution formula that covers a significant number of cases and contains a single instance that weakens its sufficiency claims.Footnote 11

The analysis of sufficient conditions simultaneously challenges one empirical expectation while providing initial support for the others. Specifically, building coalition cabinets based on pre-electoral alliances was expected to be a central strategy for weak presidents. However, the analysis of sufficiency shows that no condition is individually sufficient to account for the outcome; rather, the conjunctural causation of configurational comparative methods is reinforced, in the sense that the explanatory conditions are individually insufficient but jointly relevant in bringing about the similarity between post- and pre-election coalitions. Consequently, there is provisional support for MAJ, LWPOL, HLPOL, and HTEMP to be causally important factors for Coalition Resemblance when combined with one another and LPP.

To a lesser or greater extent, the findings indicate that every condition works as an INUS condition. Despite this, the combination of Majority and Low Within Polarization, and the individual condition of High Legislative Polarization stand out in the results for a few reasons. Not only does the former cover the greatest number of cases among the four pathways, but it also provides additional support for recent findings in the literature (Albala et al., Reference Albala, Borges, Silva, Dumont, Grofman, Bergman and Louwerse2024). Meanwhile, the latter features in three out of the four paths, contrasting with other conditions, such as Low Presidential Power, which only appears once. No less importantly, the fact that legislative polarization constrains the first cabinet built by the president-elect also resonates with prior literature (Couto, Reference Couto2025). Accordingly, the first significant contribution of this study to the literature is to demonstrate that some past findings from variable-centred research are robust when closely examining the cases behind the conversion of pre-electoral coalitions into coalition cabinets. At the same time, however, it provides a much-needed refined portrait by highlighting how the transition from pre- to post-electoral coalitions cannot be explained by any single factor, but rather by the interplay among several contextual and institutional conditions. Crucially, a further qualification emerges from later within-case analyses: diverging from existing studies, the causal role of High Temporal Constraint in producing coalition resemblance is called into question.

If the set-theoretic analysis for sufficiency for coalition resemblance has yielded a wealth of findings, the results for the non-outcome (a dissonance in composition between pre-electoral coalitions and coalition cabinets) are largely uninformative given their low coverage. However, this was expected to some degree, as the conditions have primarily been calibrated to explain the similarity between pre- and post-electoral coalitions. Consequently, a handful of potential explanatory conditions to account for the difference between pre- and post-electoral stages, such as a profound ideological difference among pre-electoral coalition members, have not been adequately captured. As recommended by best practices, the necessity and sufficiency analyses for the non-outcome are nevertheless available and can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Robustness tests

By default, several methodological decisions in configurational comparative methods lie at the researcher’s discretion, such as which procedure should be used to calibrate conditions, which benchmark should be applied in necessary and sufficient analyses, and so forth. Naturally, this raises concerns about the validity of QCA results, since they could be driven purely by researcher choices. To address this issue, the literature has come up with several tests to probe the soundness of QCA results (Ide, Reference Ide2015; Oana and Schneider, Reference Oana and Schneider2024; Skaaning, Reference Skaaning2011), which have been widely employed in QCA recent empirical research (e.g. Janzwood, Reference Janzwood2020). For current purposes, these tests consist of changing the case selection, modifying the rules for calibrating conditions and the outcome, performing a variety of cluster analyses, and adjusting the consistency benchmark used in the analysis of sufficient conditions. Due to space constraints, these tests can be found in Section 8 in the Supplementary Material. Overall, the results found for the first three pathways in the original analysis remain largely consistent throughout all the tests. That said, Path 4 has shown to be largely sensitive to model specifications and ∼LWPOL is replaced in Path 2 in a couple of diagnostic tests.

Discussion and case studies

Even if QCA excels at bringing the cases to the fore, the present study has so far been much closer to a condition-oriented QCA than a case-oriented QCA.Footnote 12 To fill this gap, I now pass on to the discussion of how the solution derived in the second-to-last section applies to some cases. From reading the solution formula, the explanation of what makes coalition cabinets similar to their pre-electoral origins resides in four paths. Below, I select a few cases from each configuration to illustrate how conditions operate as gears towards Coalition Resemblance.

The first route towards coalition resemblance is marked by majority pre-election coalitions composed of ideologically like-minded members. This path is neatly exemplified by most of the Chilean coalition cabinets present in the analysis, such as Bachelet I and II, Frei, and Lagos. By securing a legislative majority in one chamber and at least a semi-majority in the other, there was little reason to expel any party from the alliance or to bring in a new partner. Moreover, the closeness between pre-electoral coalition members on the left–right scale further reinforced the reasons for maintaining the pre-electoral pact. Despite bringing the Chilean cases as examples, this combination is not idiosyncratic to Chile. In Colombia, the right-wing pre-election coalitions led by Uribe and Santos in their re-election attempts exhibited similar features: despite minor changes, pre-electoral coalitions that held close to a majority in the legislature and were composed of parties with similar policy stances served as the bedrock for the upcoming governments.

In stark contrast, the second path combines the absence of policy congruence among pre-electoral coalition members with high overall ideological polarization in the legislature and a short period until the government’s inauguration. This configuration speaks to Rousseff I and II in Brazil, where the ideological distance between pre-election coalition members on the left-right dimension should have resulted in the outright dismantling of the multiparty agreement at the post-electoral stage. This notwithstanding, pre-electoral coalitions still formed the basis of the first coalition cabinets following each election, resulting in a remarkably low ideological distance between government and opposition in both governments (Borges, Reference Borges2021). Why was this the case? According to the second path, the explanation for this resides in the fact that the polarization at the party system level was high, thereby implying that rearranging interparty negotiations would be costly. In fact, not including major centre-right parties in the ministerial allocation process would not only most likely have triggered a political crisis earlier than expected in Rousseff II (Hunter and Power, Reference Hunter and Power2019) but was practically out of the question given that the vice-presidency was handed to a key right-of-centre party, the Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB, Movimento Democrático Brasileiro). In this context, it seems rather unlikely that Rousseff would have drastically promoted a change even if she had more time to reconsider the partisan composition of her cabinets. As this same story applies to Lula I, our confidence in the importance of High Temporal Constraint should be considerably reduced. Thus, the conclusion is that a contextual condition (i.e. legislative polarization) eased the transformation from pre-election alliances into governing coalitions even though pre-election coalition members were ideologically far apart from one another.

High legislative polarization and low internal polarization are at the core of the third and fourth paths, but in conjunction with different conditions. In broad terms, legislative polarization is combined with formally weak presidents in the third path, whereas the fourth path connects it to non-weak heads of government and the absence of high temporal constraint.

The first government of Chávez in Venezuela is an example of the former path. To be fair, Chávez proceeded to take the first steps towards autocratic rule at the beginning of his government by concentrating power in the executive after a successful constitution-making process (Landau, Reference Landau, Landau and Lerner2019). Yet, at the time of his election, the then-constitution did not grant him enough power to defy the existing order on his own. In fact, pre-election coalition formation was a hard-won feat for Chávez, especially as it was part of the strategy to legitimize him in front of voters (Handlin, Reference Handlin2017). Coupled with the fact that the remaining parties had very different policy preferences from Chávez and the Fifth Republic Movement (MVR, Movimiento V República), it made little sense for Chávez not to base his government on the pre-electoral pact. More remarkably, there is virtually no indication that Maduro would ever have opened talks with opposition parties to enlarge his government had the temporal distance between elections and the inauguration day been larger (Brewer-Carías, Reference Brewer-Carías2010). In contrast to the QCA output, this represents yet another case-based piece of evidence against the causal role of the time-pressured post-election period in producing coalition resemblance.

By contrast, the latter path presents a different configuration. Its causal link, however, should be questioned for two reasons. First, different tests either prompt substantial changes in the combinatorial composition of this final path or completely remove it from the results. Second, this is the only path that covers a deviant case in consistency for the sufficiency analysis.Footnote 13 Specifically, this case is the Balladares government in Panama in 1994. In theory, the case is not overly complicated: the pre-election alliance was composed of rather small parties that failed to provide a legislative majority to the president-elect. Crucially, these parties failed to pass the electoral threshold and were later incorporated into the presidential party. In this context, the presidential party sought out another partner to consolidate the policy-making process of the future government, thereby making the post-election coalition cabinet look very different from the initial pre-election alliance. At the same time, it is unclear to what extent pre-election coalition partners influenced the post-election bargaining process. All of this suggests that we should be extremely cautious in drawing inferences from this last configuration.

Concluding remarks

Thirty years ago, there was barely any study interested in examining how pre-election coalitions influence government formation processes, with the notable exception of Strøm, Budge and Laver (Reference Strøm, Budge and Laver1994). Fortunately, the literature has undergone a tremendous shift, as a large body of research today is dedicated to studying the relationship between pre-electoral alliances and coalition formation, governance, and survival across different systems of government (e.g. Ferrara and Herron, Reference Ferrara and Herron2005; Ibenskas, Reference Ibenskas2016; Spoon and West, Reference Spoon and Jones West2015).

In presidential democracies, in particular, pre-election coalitions are not automatically transformed into coalition governments, as executive-legislative relations derive from the independent election of the executive and the legislative branches. Against this backdrop, the main aim of this paper was to take a closer look at the process by which pre-electoral pacts become post-electoral coalitions in Latin American presidential democracies. This was done especially from a more case-centric perspective on causality. Instead of relying on conventional statistical methods, I subscribe to a configurational approach to study under which conditions post-electoral coalitions mirror their pre-electoral antecessors.

The findings suggest that a combination of contextual and institutional factors is required to understand the degree of stability between pre- and post-electoral coalitions. In varying ways, the seat share granted by pre-electoral coalition members, their alignment on policy goals, the general ideological polarization in the legislature and low presidential powers combine to explain the conversion of pre-electoral into post-electoral coalitions. More specifically, one of the pathways towards coalition resemblance is the combination of a majority seat share with congruent policy views from pre-election coalition partners. Other paths highlight constraints outside the boundaries of pre-election coalitions, such as an ideologically divided legislature and weak presidential powers. Importantly, the analysis reveals that no condition is individually sufficient to account for this process; rather, the explanation resides in the interplay among different factors.

As a consequence, three main takeaways can be retrieved from this work. First, pre-electoral coalition majority status clearly matters for post-electoral coalition formation, but only in combination with low ideological differences among pre-election coalition members. Second, the findings suggest that pre-election coalitions are not necessarily bound to dissipate in the post-electoral scenario if their members have significant differences in policy preferences. If the party system is characterized by irreconcilable policy divergences, then pre-election coalitions are well-positioned to serve as the foundation for the incoming government. While these two contributions further corroborate existing findings in the literature, this article also challenges current knowledge about coalition politics in presidential democracies more generally, and about the transformation of pre-election coalitions into multiparty governments in particular. More specifically, although presidential powers matter for the portfolio allocation process (Silva, Reference Silva2023), I have found very limited support for the causal relevance of low presidential powers to the resemblance between pre- and post-election coalitions. More critically, case analysis shows even less evidence for the role of the institutional time constraint of presidential elections in shaping coalition resemblance. No matter how long the distance between the election results and the government’s inauguration day, the cases covered in this study would most likely still have been based on their pre-election alliances.

While recent years have witnessed a wealth of research on pre-electoral coalitions, there still remains, of course, significant potential for further developments. Departing from this study, future research would greatly benefit from differentiating types of conversion of pre-electoral coalitions into full-fledged coalition governments. In this paper, despite analysing the reasons behind the similarity between pre- and post-electoral coalitions, all changes in pre-electoral coalitions were treated as if they were equivalent to one another, though bringing in another party is very different from expelling a member from the alliance. As a consequence, the different changes that pre-electoral coalitions undergo between the pre- and post-electoral periods deserve closer attention in future research.

In addition, another potential avenue for future research is examining the translation of pre- to post-electoral coalitions from the perspective of within-case studies. This is especially the case in the literature on coalitional presidentialism, a field desperately in dire need of more qualitative studies. Despite adopting a case-oriented approach, the discussion here is bounded by the typical cross-case nature of QCA and confined to typical cases of each causal pathway. Moreover, this analysis features a limitation in not fully exploring the richness of QCA’s different types of cases, each of which serves a specific purpose in causal explanations (Oana and Schneider, Reference Oana and Schneider2018). Thus, future case studies can be conducted to complement (or cast doubt on) this paper’s findings.

Lastly, the coalition literature would be greatly enriched by case studies also conducted at the party level. While this paper has been limited to studying the multiparty aspect of pre-electoral coalitions, it is indisputable that intraparty tensions play a role in party fates. Even if coalition governments result from interparty bargaining, case studies on intraparty politics can help us better understand the processes by which pre-electoral coalitions are formed, expanded and dissolved, in some cases even before presidents are sworn into office.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773925100222.

Data availability statement

Research documentation, data, and replication files are openly available in: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/YL2TGH.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Adrián Albala, Frederico Bertholini, André Borges, and Raimondas Ibenskas for their insightful comments on an early version of this article. I am also indebted to several anonymous reviewers and the EPSR editors for their constructive feedback and critical engagement with the paper. Finally, this paper has also greatly benefited from the methodological literature on configurational comparative methods, without which it would never have come to fruition. All remaining errors are my own.

Funding statement

This research was funded by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) through its scholarship for master’s studies.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests in the research, writing, and publication of this article.