Are citizens who look to religious authority figures for guidance about politics more likely than others to support political violence? Scholars have long suspected that deference to religious authority erodes support for democratic norms, including those forbidding the use of violence for political ends. Yet studies in this area have yielded mixed results. Indeed, the impact of religiosity on support for political violence appears to vary across faith traditions and also according to the particular facet of “religiosity” that is examined (whether individual beliefs or communal practices, for example). Hence, a recent survey of the literature concludes that the relationship between religiosity and support for liberal democratic norms, including the rejection of political violence, is “ambivalent.” Religion simultaneously inculcates “undemocratic values and practices” and “foster[s] development of democratic norms and practices” (Arikan and Ben-Nun Bloom, Reference Arikan and Ben-Nun Bloom2019).

We accept that religiosity is a multifaced phenomenon, and that its impact on democratic values will vary according to the specific beliefs or practices that are being examined. At the same time, we believe the unsettled state of the literature reflects a failure to focus on the fundamental question of whether loyalty to religious leaders, texts, or edicts is inherently at odds with democratic commitment. Stated positively, we hope to advance the debate by refocusing attention on the question of deference to religious authority in politics (DRAP), by which we mean the degree to which citizens follow, or purport to follow, religious guidance when making decisions about political matters. We suspect that citizens with high self-reported levels of deference to religious authority will exhibit less support for democratic norms, such as the rejection of political violence, even after controlling for other known correlates of support for violence. Relatedly, we suspect that deference to religious authority will exert an independent impact on support for violence that is not captured by other common measures of religiosity, such as worship attendance and Biblical literalism. Finally, we posit that the relationship between self-reported deference to religious authority and support for violence will be more pronounced among believers with low levels of religious attendance.

We test these hypotheses using a new measure of DRAP developed from the 2024 Chapman Survey of American Fears (CSAF). The DRAP index is constructed from survey questions asking whether respondents believe that decisions in the political realm should be guided by advice from religious sources. The dependent variable is a scale constructed from questions asking whether the use of violence is justified to achieve political outcomes.

We begin by reviewing the literature on religiosity and democratic norm support. Significantly, the measures of religiosity used in this literature typically gauge respondents’ levels of religious participation (e.g. worship attendance) or support for particular religious tenets (e.g. Biblical literalism). At least in the US context, scholars have rarely attempted to measure deference to religious authority directly (but see Burge and Djupe, Reference Burge and Djupe2022). We then explain our new DRAP measure, which we believe provides a more accurate measure of the extent to which citizens seek religious guidance in political affairs. After providing summary statistics of the demographic and other correlates of deference to religious authority, we analyze its relationship to support for political violence. The evidence presented strongly supports the hypotheses listed above: deference to religious authority both predicts support for political violence and exerts an effect not captured by other common measures of religiosity. Additionally, the positive relationship between deference to authority and support for violence is more pronounced among respondents with low levels of religious attendance. We suggest that this last finding may be explained by differences in the types of religious guidance sought by attending and non-attending believers: while the former are more likely to seek guidance from real-world congregational leaders, the latter may be more likely to seek guidance from self-selected religious influencers and commentators.

Religiosity, democratic commitment, and support for political violence

The basic intuition driving the literature on religion and democratic commitment is easily summarized: If believers are duty-bound to obey the dictates of sacred texts or spiritual leaders, it may be difficult for them to accept the legitimacy of political arrangements or outcomes that do not conform to the tenets of their faiths. The idea that religiosity is necessarily in tension with respect for democratic norms is explored in several classic works (Adorno et al., Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950; Habermas, Reference Habermas2006; Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Rawls, Reference Rawls1993). However, there is no firm consensus on this point, and some scholars maintain that religiosity actually bolsters support for democratic values (see e.g. Putnam and Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Tocqueville, Reference Tocqueville2003).

A somewhat clearer picture emerges when “religiosity” is disaggregated so that the effects of its various components—often conceptualized as “belief, belonging, and behavior”—can be measured separately (see e.g. Layman, Reference Layman2000, 55–58; Leege and Kellstedt, Reference Leege and Kellstedt1993; Smidt, Reference Smidt2019). For example, several studies have found that specific types of religious beliefs, including a dogmatic or fundamentalist orientation, are correlated with lower levels of tolerance, democratic commitment, and social trust (Gibson, Reference Gibson, Alan and Ira2010; Jelen and Wilcox, Reference Jelen and Wilcox1991; McFarland, Reference McFarland1989). Similarly, Christians who score high on measures of Biblical literalism appear to be both less tolerant of other perspectives and less supportive of democratic norms (Burdette et al., Reference Burdette, Eillson and Hill2005; Guth, Reference Guth2019; Schwadel and Garneau, Reference Schwadel and Garneau2019), as do those who possess a “wrathful” image of the deity (Froese et al., Reference Froese, Bader and Smith2008). Finally, a growing body of literature suggests that “Christian nationalist” (CN) beliefs tend to undermine support for democratic principles and procedures (Djupe et al., Reference Djupe, Lewis and Sokhey2023; Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020; Walker and Vegter, Reference Walker and Vegter2023).

A separate body of research hypothesizes that different religious groups—whether conceptualized as faith traditions, religious movements, or congregations—will exhibit differing levels of support for democratic norms. Because religions and sects differ widely in their substantive teachings and internal dynamics, the thinking goes, individual-level toleration and support for democratic values will tend to vary according to the specific group to which an individual belongs (see e.g. Huntington, Reference Huntington1996; Toft et al., Reference Toft, Philpott and Samuel Shah2011). To date, however, efforts to determine whether specific religious traditions (e.g. Islam, Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and evangelical Christianity) promote or discourage democratic commitment have yielded mixed results (see e.g. Anderson, Reference Anderson2004; Gu and Bomhoff, Reference Gu and Bomhoff2012; Hoffman, Reference Hofmann2004; Radu, Reference Radu1998; Roy, Reference Roy2023; Shah, Reference Shah2004; Wilcox and Jelen, Reference Wilcox and Jelen1990). A related body of work, focused on the strength of religious group identification (as opposed to the effects of specific faith traditions), suggests that religious group membership may simultaneously bolster and undermine democratic values. On the one hand, a strong sense of religious group identity appears to promote democratic participation and civic engagement (Djupe and Gilbert, Reference Djupe and Gilbert2006; Nieheisel et al., Reference Nieheisel, Djupe and Sokhey2008; Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2004; Putnam and Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010); on the other hand, strong group identity may heighten believers’ sense of being threatened by outgroups, which may in turn lead to a decrease in toleration and other democratic values (Ben-Nun Bloom et al., Reference Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan and Courtemanche2015; Braunstein, Reference Braunstein, Sokhey and Djupe2024; Broeren and Djupe, Reference Broeren and Djupe2024; Djupe and Calfano, Reference Djupe and Calfano2013).

A final strand of the literature focuses on religious behavior, such as frequency of attendance at religious services. Here, too, the impact of strong religiosity on democratic commitment appears to be mixed. Although frequency of religious participation may promote civic skills and political participation (see e.g. Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, MacGregor and Putnam2013; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wright Austin and Orey2009; Putnam and Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010), some studies have found that it also heightens individuals’ sense of in-group identity, leading to lower levels of tolerance for disliked groups and less support for civil liberties (Djupe and Calfano, Reference Djupe and Calfano2012; Reimer and Park, Reference Reimer and Park2001; Sherkat et al., Reference Sherkat, Lehman and Bill Julkif2023). However, there is disagreement on this point, and other studies have found a positive correlation between religious participation and such pro-democratic values as trust in democratic institutions and tolerance of outgroups (Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan, Reference Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan2012; Burge, Reference Burge2013; Stroop et al., Reference Stroope, Rackin and Froese2021). Still other scholars maintain that the apparent relationship between religious participation and democratic norm support (whether positive or negative) is attenuated, and perhaps disappears altogether, when controls for psychological traits such as dogmatism, self-esteem, and social trust are introduced into the analysis (Eisenstein and Clark, Reference Eisenstein and Clark2014; Eisenstein and Clark, Reference Eisenstein and Clark2017).

The subset of studies examining the relationship between religiosity and support for political violence, specifically, have yielded similarly conflicting results. On the one hand, this is not surprising, given that the world’s major religions and sects offer conflicting teachings on the question of when, if ever, violence is acceptable. Still, growing literatures on both “political Islam” and “Christian nationalism” indicate that what may be loosely termed theocratic attitudes are associated with greater support for violent forms of political action (Armaly et al., Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022; Armaly and Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2024; Beller and Kröger, Reference Beller and Kröger2018; Bueno de Mesquita, Reference Bueno De Mesquita2007; Fair et al., Reference Fair, Hamza and Heller2017; Shady et al., Reference Shady, Hooghe and Marks2024; but see Fair et al., Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2012). Additional recent work suggests that the melding of religious and partisan identities may boost support for violence, at least in the United States (Kalmoe and Mason, Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022). Other studies, however, have found that introducing socioeconomic and other demographic controls undermines claims of a clear relationship between religiosity and political violence (Canetti et al., Reference Canetti, Hobfoll, Pedahzur and Zaidise2010). Further complicating matters is the fact that studies in this area often fail to disaggregate religiosity into its separate components, which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions about potential relationships (see e.g. Zaidise et al., Reference Zaidise, Canetti-Nisim and Pedahzur2007).

Based on the foregoing, it appears that the relationship between “religiosity” and support for democratic norms, such as the renunciation of political violence, is complex and arguably contradictory. Religion’s impact on democratic norms seems to depend on which aspect of religiosity is being examined, as well as the organizational structures and substantive beliefs of the religious group in question (Arikan and Ben Nun-Bloom, Reference Arikan and Ben-Nun Bloom2019; Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan, Reference Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan2012; Bloom, Reference Bloom2012; Philpott, Reference Philpott2007). We believe that this insight, while important, should not stand as the final word on the subject. Instead, we propose to advance the debate by focusing greater attention on the psychological propensities and communicative contexts that push some believers, but not others, to embrace violent or extreme forms of political action.

Deference to religious authority as a possible driver of support for political violence

As a first step toward clarifying matters, it is helpful to recall that much of the literature we have just reviewed stems from a single theoretical claim: that religious faith, which typically demands absolute fidelity to a set of divine commandments, is inherently difficult to reconcile with liberal democracy’s emphasis on toleration and compromise. That this tension exists is clear. Yet it would be a mistake to assume that it is equally present in all religious traditions or in the lives of all believers, or that it necessarily drives support for political violence. In fact, many religious thinkers and traditions explicitly endorse liberal democracy—and the tolerance of difference it entails—as the ideal governing structure for a fallen world in which sinful human beings cannot be relied upon to translate divine truth into legal commands, or else on the grounds that governmental or coercive enforcement of religiously “correct” beliefs and behaviors is ineffective or counterproductive (see e.g. McGraw, Reference McGraw2010; Murray, Reference Murray1993; Niebuhr, Reference Niebuhr2011). Other sects practice forms of separatism which, in the name of maintaining the purity of the religious community, proscribe entanglement with contemporary political debates and, by extension, the use of violence to intervene in said debates (Joireman, Reference Joireman and Joireman2009). Finally, as a practical matter, most religious groups are internally divided on whether believers are obligated to bring secular governing structures into alignment with religious doctrines—and also about the means that may be used to achieve such an alignment. American Catholics, for example, can easily find co-religionists who advocate peaceful and democratic means of resolving political disagreement, as well as those who advocate a theocratic “regime change” that would overthrow liberal democracy (see e.g. Vallier, Reference Vallier2023; Deneen, Reference Deneen2023), and there is evidence that a similar debate is playing out among evangelicals and other Protestants (Gorski and Perry, Reference Gorski and Perry2022; Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020).

The reality of intra-tradition disagreement, coupled with the relatively loose authority structures that characterize religious practice in the twenty-first-century United States, suggests that the question of how best to reconcile one’s religious convictions with undesired political outcomes is often left to the discretion of the individual believer (Chaves, Reference Chaves1994; Compton Reference Compton2020). Indeed, recent studies on the political influence of the clergy make clear that few believers passively acquiesce to political cues from their purported spiritual leaders (Calfano et al., Reference Calfano, Oldmixon and Gray2014; Djupe and Calfano, Reference Djupe, Calfano, Djupe and Claassen2018; Djupe and Gilbert, Reference Djupe and Gilbert2008). Hence, even in instances where religious groups are strongly committed to liberal democracy, there is little reason to believe that such convictions are reliably passed on to parishioners in a hierarchical manner (see e.g. Margolis, Reference Margolis2018b; Melkonian-Hoover and Kellstedt, Reference Melkonian-Hoover and Kellstedt2019; Roy, Reference Roy2023).

This, in turn, prompts the question: Why do some believers endorse political violence while others reject it? We suspect that the answer can be traced to (1) the psychological predispositions and attitudes of individual believers and (2) the specific communicative contexts in which believers are enmeshed. Stated otherwise, the tension between religiosity and liberal democratic citizenship should not be understood as an inescapable fact of religious belief (or of membership in a particular tradition), but rather as a trait or attitude that varies across the population of believers, and which may be meliorated or exacerbated by a believer’s particular environment.

It is well established that some believers are predisposed to a zero-sum view of the tension between religious and liberal democratic political authority (e.g. Altemeyer and Hunsberger, Reference Altemeyer, Hunsberger, Paloutzian and Park2005; Armaly et al., Reference Armaly, Buckley and Enders2022). Such believers tend to view the religious sphere as inherently good, while viewing the liberal democratic political sphere as inherently suspect, since the latter demands toleration of beliefs and behaviors that may run counter to divine law. This worldview, in turn, is plausibly related to support for political violence, since passive toleration of political outcomes or structures that conflict with divine commands may put the believer at risk of eternal damnation (Juergensmeyer, Reference Juergensmeyer2017). Although violence is far from the only way of resisting disfavored outcomes, it presents itself as an obvious possibility when peaceful or democratic means are seen as ineffective or inconvenient (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2015).

Scholars of religious fundamentalism have significantly advanced our understanding of the tension between religious and political authority—and of why this tension sometimes manifests in support for political violence (see e.g. Almond et al., Reference Almond, Scott Appleby and Sivan2003; Altemeyer and Hunsberger Reference Altemeyer and Hunsberger1992; Appleby, Reference Appleby, Omar, Scott Appleby and Little2015).Footnote 1 However, fundamentalism as conventionally defined provides an incomplete picture of the forces that lead some believers to support violent or illiberal forms of political action.Footnote 2 One problem is that scholars often include support for violence in their definitions of fundamentalism (e.g. Schneider and Pickel, Reference Schneider and Pickel2021; Steinmann and Pickel, Reference Steinmann and Pickel2025). This works well enough when the aim is to predict support for xenophobic policies (for example), but it presents obvious problems when support for violence is the dependent variable. Moreover, conventional definitions of fundamentalism include factors, such as belief in the literal truth of a sacred text, that are peripheral to what we take to be the main potential driver of support for political violence: namely, the belief that one’s actions in the political sphere should be subordinate to—and guided by—religious influences of some kind.

We therefore view DRAP, rather than fundamentalism (as conventionally defined), as the most important predictor of religiously motivated support for political violence. At the same time, we would caution that psychological traits or attitudes concerning authority, by themselves, are unlikely to fully explain believers’ differing levels of support for political violence and extremism. Hence, our second claim: the communicative context in which believers are embedded also matters.

It is well established that communicative contexts and congregational dynamics shape the political beliefs and behavior of religious individuals (see e.g. Djupe et al., Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018; Djupe and Neiheisel, Reference Djupe and Neiheisel2022; Wald et al., Reference Wald, Owen and Hill1988). Studies of religious communication typically investigate the conditions under which individual believers adopt (or reject) political cues from religious elites or fellow congregants. At least in the modern United States, the relative weakness of hierarchical religious authority means that whether a given believer accepts political cues from religious leaders typically depends less on the formal teachings or authority structures of the believer’s tradition than on the communication patterns, authority dynamics, and political orientation of the local congregation (Djupe and Neiheisel, Reference Djupe and Neiheisel2022, 168). Although studies in this vein typically focus on congregations and other in-person group settings, the basic insight can be extended beyond brick-and-mortar places of worship. Indeed, at a time when many believers report that they have little or no contact with a real-world congregation, it appears that Americans are increasingly taking religious guidance where they can find it—whether on social media, via streaming platforms, or from podcasts (Campbell, Reference Campbell2020; Campbell and Bellar, Reference Campbell and Bellar2022).

We should also consider that religious political guidance may no longer operate in a unidirectional or top-down fashion, with believers accepting (or rejecting) cues from their designated leaders. Rather, given current levels of political polarization, there is growing evidence that many believers favor religious “guidance” that confirms preexisting political views or prejudices. Believers may even switch between available options as needed to justify support for preferred candidates, parties, or policies (Egan, Reference Egan2020; Margolis, Reference Margolis2018a; Patrikos, Reference Patrikos2008). Hence, whether deference to religious authority is predictive of support for political violence likely depends in part on what “authority” means in the concrete case of an individual believer. A believer who takes his or her cues from a real-world congregational leader may adopt a very different attitude toward political violence than a believer who takes his or her cues from an online religious personality, even if the two hypothetical believers share a similar psychological profile, religious affiliation, and political orientation.

In sum, we suspect there is a subset of believers, across all traditions, for whom the religious sphere is inherently superior to the (liberal democratic) political sphere. For these believers, some form of religious guidance (however conceptualized) will typically be seen as essential to navigating the political realm, and political outcomes that run counter to religious guidance may be seen as illegitimate and unworthy of respect. But not all believers who report a high degree of deference to religious authority will take the further step of concluding that disfavored political outcomes may legitimately be met with violence. Openness to political violence is likely to be exacerbated (or mitigated) by the specific communicative context in which a believer is embedded.

Deference to religious authority in politics: the need for a new measure

Crucially, none of the variables typically used to measure the “three B’s” (belief, belonging, and behavior) appear to be reliable proxies for DRAP. The familiar Biblical literalism variable, for example, fails to capture religious authority dynamics within traditions, such as Catholicism, that do not promote a literal reading of sacred texts (Burge and Djupe, Reference Burge and Djupe2022, 172). Similarly, religious participation variables, while possibly correlated with deference to religious authority in the congregational or group context, shed little light on authority dynamics that operate outside of face-to-face or congregational channels, as when believers are influenced by religious personalities on the Internet or social media. Such variables fail to account for the fact that many modern-day believers are subject to (or view themselves as subject to) religious authority even when they have little or no connection to a real-world congregation (see e.g. Cambell and Bellar, Reference Campbell and Bellar2022; Evolvi, Reference Evolvi2021).

“Christian nationalism,” although plausibly related to religious deference, is not a suitable proxy for DRAP. The CN scale is designed to capture a specifically (often American) Christian worldview, whereas the trait of deference to religious authority should be present across all religious traditions. Moreover, the questions typically used to construct the CN scale are focused on symbolic expressions of Christian identity, as opposed to the dynamics of religious authority as experienced by individual believers (Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). They ask whether Christian identities and symbols should receive pride of place in American politics and society; they do not attempt to measure the extent to which believers are, or see themselves as, guided by religious authority when acting in politics.Footnote 3

In theory, one could avoid the need for proxies by measuring deference to religious authority in a more straightforward way—for example, by simply asking respondents whether they seek and/or accept religious guidance when acting in the political realm.Footnote 4 Still, such questions are surprisingly rare in survey research on religion and politics in the United States. To date, we are aware of only one study that has attempted to operationalize deference to religious authority in the American context.Footnote 5 Burge and Djupe’s (2019) Religious Authority Values (RAV) scale is derived from a battery of survey questions measuring respondents’ fidelity to congregational leaders and religious orthodoxy. Significantly, Burge and Djupe find that their religious authority measure is inversely correlated with support for democratic norms, including support for free expression and checks on majority rule. Moreover, they find that the RAV captures a distinct psychological trait that is not reducible to dogmatism or (secular) authoritarianism. Their study thus marks an important step forward in the research on religious authority and democratic commitment in the United States.

Nonetheless, it suffers from certain limitations. For example, the questions used to compose the RAV measure are entirely focused on respondents’ attitudes about authority relations within religious groups or traditions; they do not attempt to measure whether respondents are guided by religious authorities when making decisions about external matters, such as which candidates or policies to support in secular elections.Footnote 6 And while it may be true that one form of authority entails the other, we do not believe this can be assumed. Some believers likely defer to religious leaders (or other sources of religious authority) on narrowly spiritual questions or matters of internal group governance while looking elsewhere for guidance about politics. In addition, two of the three datasets used in the Burge and Djupe article are limited to avowedly religious respondents (in one case members of the clergy). While these limitations do not affect the authors’ ability to establish the viability of deference to religious authority as a distinct psychological disposition, they do indicate a need for caution when using the RAV scale to draw conclusions about the relationships between religious authority, democratic commitment, and political extremism in the wider population.

We propose a new measure of DRAP, described below, that we suspect will be positively and significantly correlated with support for political violence. In addition, we believe our measure will provide greater clarity about how other, commonly used measures of religiosity (e.g. attendance, Biblical literalism, self-reported religiosity) relate to support for political violence. Hence, the first two hypotheses we propose to test:

H1: Greater deference to religious authority in politics (DRAP) is positively related to support for political violence.

H2: Traditional measures of religiosity are unrelated to support for political violence once the effects of DRAP are taken into account.

Finally, we suspect that the relationship between deference to religious authority and support for political violence will differ across the spectrum of religious attendance. We base this claim on two considerations. First, although there is debate on this point, several studies have found that religious attendance (and social engagement more generally) exerts a moderating influence on believers’ political opinions and behavior (Bloom Reference Bloom2012; Putnam and Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Stroope et al., Reference Stroope, Rackin and Froese2021). Conversely, social isolation appears to exacerbate the tendency toward extreme political views and behavior (Gade, Reference Gade2020; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Osmundsen and Arceneaux2023; Pfundmair et al., Reference Pfundmair, Wood, Hales and Wesselmann2024).

Second, we assume that the type of religious guidance sought by high-attending believers will differ systematically from that sought by low-attending believers. When high-attending believers report that they seek religious guidance in politics, they are likely thinking of a traditional congregational leader or the official doctrines of a denomination or faith tradition. On balance, such guidance might be expected to discourage radical or illiberal forms of political action, since most major religious groups in the United States are at least nominally committed to democratic processes and the peaceful resolution of political disagreement. In contrast, when low-attendance believers indicate that they seek religious guidance in politics, they are more likely thinking of some type of entirely self-selected religious guidance—whether an online influencer, a social media personality, or a television preacher or commentator. When religious guidance operates in this way, it brings into play all the well-documented pathologies of digital media and online information ecosystems as they relate to political behavior and opinion formation. Such “guidance” may, for example, push believers toward extreme positions, shield them from moderating or countervailing influences, or erode trust in democratic institutions (Falkenberg et al., Reference Falkenberg, Zollo, Quattrociocchi, Pfeffer and Baronchelli2024; Kubin and Von Sikorski, Reference Kubin and Von Sikorski2021; Lorenz-Spreen et al., Reference Lorenz-Spreen, Oswald, Lewandowsky and Hertwig2023). Hence, our final hypothesis:

H3: The positive relationship between deference to religious authority in politics (DRAP) and support for political violence will be more pronounced among respondents with low levels of religious attendance.

Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we rely on the CSAF (see Bader et al., Reference Bader, Baker, Edward Day and Gordon2020). Conducted annually for the past 10 years, this nationally representative survey utilizes a probability-based design. The use of a probability sample rather than an opt-in design yields numerous benefits including accuracy and reduction of biases (MacInnis et al., Reference MacInnis, Krosnick, Ho and Cho2018; Zack et al., Reference Zack, Kennedy and Scott Long2019). The survey was fielded in the spring of 2024 over the web. There were 1008 respondents after data quality checks were conducted, yielding a survey completion rate of 45%.Footnote 7

Deference to religious authority in politics (DRAP) index

A 4-item index was constructed to measure DRAP. All four items were designed to measure respondents’ propensity to seek guidance from religious leaders when acting in the political realm. The first three items are Likert scales that range from (1) strongly agree to (4) strongly disagree: “On political issues, the advice of religious leaders should outweigh one’s own feelings”; “Religious leaders are a reliable source of guidance on political issues”; “Ministers and religious leaders should not try to influence how their congregations vote in political elections.” For the first two, agreeing or strongly agreeing is consistent with deference to religious authority, while disagreeing or strongly disagreeing represents deference in the third question. Finally, we asked, “Thinking about recent elections, how often have you relied on advice from religious leaders when deciding which candidate or party to support?” with response categories ranging from (1) always to (6) never. For analysis, all items were recoded (0,1) and added together, resulting in a range of 0–4. The index has a Cronbach’s α = .70, which demonstrates an acceptable level of reliability (Ekolu and Quainoo, Reference Ekolu and Quainoo2019; Streiner, Reference Streiner2003).

For all items, the meaning of “religious leaders” was left purposely open-ended. As discussed above, there is considerable evidence that non-traditional religious figures, including digital media figures, serve as trusted sources of guidance for many believers. We did not want to preclude such interpretations by defining “religious leaders” as the traditional heads of religious congregations (e.g. ministers, priests, rabbis, and imams).

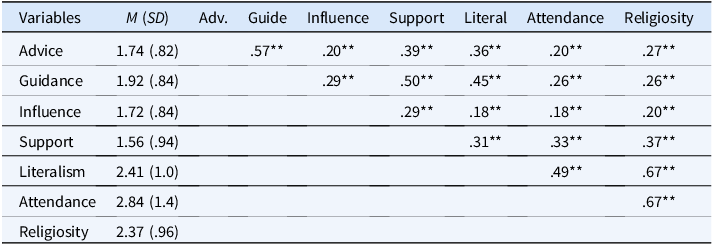

We next examined how each of the individual components of the DRAP index relate to commonly used proxies for religious authority: belief that the Bible is literally true, worship attendance, and self-reported importance of religion. Biblical literalism was measured on a four-point scale with response categories: (1) “The Bible means exactly what it says. It should be taken literally, word-for-word, on all subjects”; (2) “The Bible is perfectly true, but it should not be taken literally, word-for-word. We must interpret its meaning”; (3) “The Bible contains some human error”; (4) “The Bible is an ancient book of history and legends.” Religious attendance, originally measured on a nine-point scale, was recoded to a five-point scale ranging from (1) never attends to (5) attends once a week or more. Self-reported religiosity is measured on a four-point scale ranging from (1) not at all religious to (4) very religious.

In Table 1, we report correlations between our DRAP index components and a series of common religion variables that often serve as proxies for religious authority. Biblical (LITERALISM) is moderately correlated and statistically significant with the belief that advice (ADVICE) from religious leaders should outweigh one’s own feelings (r = .36; P ≤ .01), has a moderate, statistically significant relationship with believing that religious leaders are a reliable source of guidance (GUIDANCE) on political issues (r = .45; P ≤ .01), has a weak positive, though statistically significant correlation with whether religious leaders should influence (INFLUENCE) their congregations on how to vote (r = .18; P ≤ .01), and has a moderate relationship to frequency of relying on religious leaders for advice on whom to support (SUPPORT) in an election (r = .31; P ≤ .01). Both religious ATTENDANCE and self-reported RELIGOSITY have a statistically significant relationship with all our components. Frequency of religious ATTENDANCE has a weak correlation with ADVICE (r = .20; P ≤ .01) and GUIDANCE (r = .26; P ≤ .01), has a weak relationship with INFLUENCE (r = .18; P ≤ .01), and has a moderate relationship with SUPPORT (r = .33; P ≤ .01). Self-reported religiosity has a mild relationship with ADVICE (r = .27; P ≤ .01), a moderate one with GUIDANCE (r = .36; P ≤ .01), a mild relationship with INFLUENCE (r = .20; P ≤ .01), and a moderate relationship with SUPPORT (r = .37; P ≤ .01). Taken together, these findings illustrate that the DRAP measure is distinct from these other measures of religious authority, though related as one would expect.

Table 1. Deference to religious authority in politics by proxies for religious authority

** P < .01 (two-tailed test).

Figure 1 provides additional descriptive information concerning the relationship between our DRAP measure and common religious authority proxies. Specifically, the figure illustrates how positive responses to our religious authority questions are distributed across the range of the religious attendance, Biblical literalism, and self-reported religiosity variables, as well as across religious traditions. Again, we see that, while deference to religious authority is positively correlated with the other religion variables, there is a surprising amount of deference to authority at the lower end of the religiosity spectrum. For example, 27 percent of respondents who never attend religious services responded positively to at least one DRAP question, as did 21 percent of respondents at the bottom of the Biblical literalism scale and 18.5 percent of respondents who reported that religion was “not at all” important to them. Similarly, Figure 1 makes clear that not all high-religiosity respondents seek religious guidance when making decisions about politics. Fully 45 percent of weekly church attenders responded negatively to every DRAP question (thus earning a DRAP score of 0), as did 24.6 percent of respondents who believe that the Bible is “literally true” and 42.6 percent of respondents who report that religion is a “very important” part of their lives. There is, in short, enough variation across the range of common religion variables to suggest that the DRAP index is capturing traits or behaviors that are not reducible to other common measures of religious commitment.

Figure 1. Positive religious authority responses by common proxies for religious authority and religious tradition. (a) Positive religious authority responses by religious attendance. (b) Positive religious authority responses by Biblical literalism. (c) Positive religious authority responses by self-reported importance of religion. (d) Positive religious authority responses by religious tradition/category.

Unsurprisingly, there is some variation across religious traditions as well, with Muslim and evangelical respondents being noticeably more likely—and atheists and agnostics noticeably less likely—to report that they regularly seek religious guidance about politics. We would urge caution in interpreting these findings, however, due to (1) the small size of the Muslim sample and (2) the use of a non-standard coding scheme for evangelicals.Footnote 8

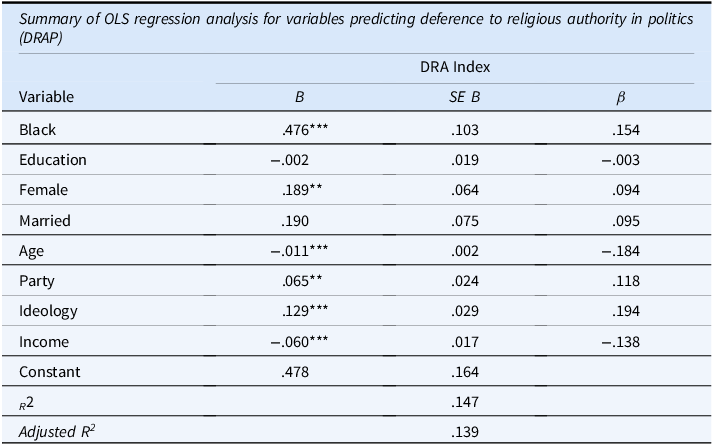

Next, we investigate the demographic predictors of DRAP in a regression analysis (Table 2). We found that conservative IDEOLOGY (β = .194; p < .001) and AGE (β = −.184; p < .001) were the most influential predictors, with younger and more conservative respondents scoring higher on the DRAP. Additionally, Black respondents (β = .154; P < .001), those with lower incomes (β = −.138; p < .001), Republican identifiers (β = .118; p = .008), and women (β = .102; p = .003) were more likely than others to score high on our measure of deference to religious authority.

Table 2. Deference to religious authority in politics by demographics

*P < .05. **P < .01. ***.001.

Dependent variable

Support for political violence was measured by a 3-item index (Cronbach’s α = .77), composed of the following statements: “The use of violence to achieve political goals is sometimes necessary”; “Force is justified to restore Donald Trump to the Presidency”; and “Because US laws and institutions are fundamentally unjust, the use of violence is justified to change them.” The response options were Likert scales ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Some 16.2% agreed or strongly agreed that violence is sometimes necessary, 12.4% agreed or strongly agreed that force is justified to restore Donald Trump to the presidency, and 17.6 % felt the use of violence is justified to change unjust laws and institutions. These responses were collapsed into binary variables and added together, yielding an index with scores ranging from 0 to 3. We use this index as the dependent variable for Models 1 through 4, reported in Table 3. For Models 5 through 8, we removed the Trump question to account for any effects due to support for Trump alone. The resulting 2-item index had a Cronbach’s α= .75.

Table 3. OLS regression models predicting support for political violence (3-item index)

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***< .001.

Control variables

We include known correlates of support for political violence, as well as basic demographic characteristics as control variables. The Internet is a source of hateful and “violence-advocating materials” that contribute to violent extremism. Moreover, “higher usage of social networking sites…and other internet services increase the probability of encountering online extremism” (Hawdon et al., Reference Hawdon, Bernatzky and Costello2019, 332; Lelkes et al., Reference Lelkes, Sood and Iyengar2017). Although we do not have a variable for what respondents view on the Internet, we do have a measure of frequency of use that is coded (1) almost constantly, (2) several times a day, (3) about once a day, (4) several times a week, and (5) less often.

Turning to party identification, our analysis includes a seven-point party identification question. Bartels (Reference Bartels2020) found that Republicans were more likely than Democrats to hold attitudes that violate democratic norms, including using force for political purposes. Similarly, Wintemute et al. (Reference Wintemute, Robinson, Tomsich and Tancredi2024) report that “MAGA Republicans” are more likely to believe there will be a civil war in the United States, and that political violence is justifiable. (There is disagreement on this point, however, and other studies have found little evidence that Republican partisanship, or extreme partisanship more generally, drives support for political violence [see e.g. Westwood, Grimmer, and Tyler Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022]).

Other control variables include age and education, which Howe (Reference Howe2017) finds are related to support for democratic norms, with younger and less educated Americans being less likely to support norms and more likely to condone violence (also see Armaly and Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2024; Desmarais et al., Reference Desmarais, Simons-Rudolph, Brugh, Schilling and Hoggan2017; Wolfowicz et al., Reference Wolfowicz, Litmanovitz, Weisburd and Hasisi2020). The eight-point education variable ranges from (1) less than high school graduate to (8) postgraduate or professional degree. Finally, demographic controls include dummy variables for female, married respondents, and Black respondents.

Results

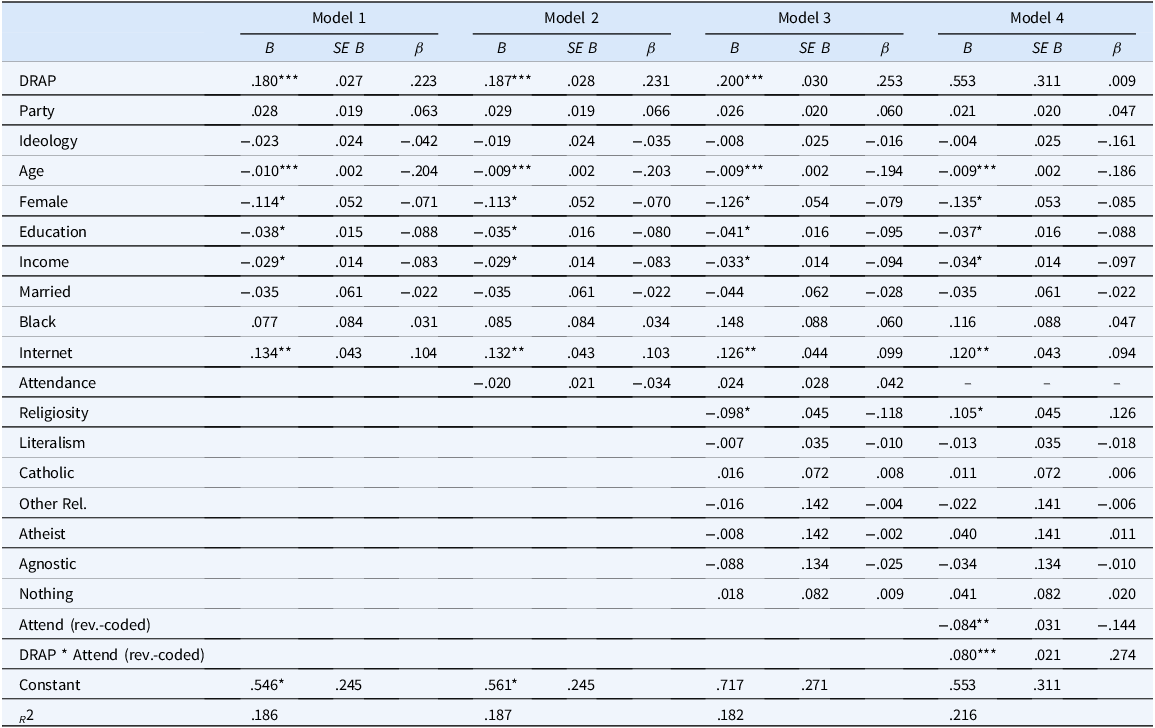

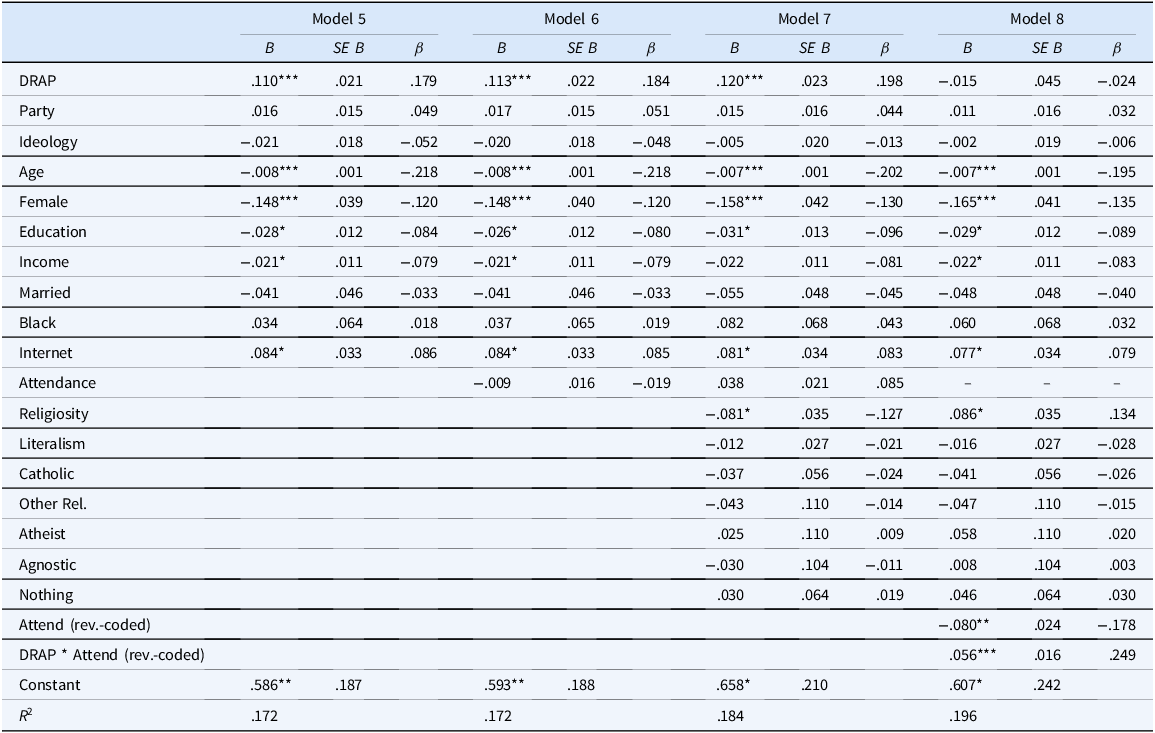

Tables 3 and 4 report a series of regression models designed to account for different possible combinations of control variables. Recent research indicates that the inclusion of multiple, highly correlated measures of religiosity in a single model is a common problem in the religion and politics literature, often resulting in suppression effects or otherwise biasing estimates (Djupe et al., Reference Djupe, Friesen, Lewis, Sokhey, Neiheisel, Broeren and Burge2025; Lenz and Sahn, Reference Lenz and Sahn2021). To avoid this problem, we first present a model (1) in which the DRAP index is paired only with the non-religion control variables listed above. We then report a model (2) that includes, in addition to the non-religion controls, a single measure of religious commitment (religious attendance). Model (3) adds a full complement of religion variables, including attendance, self-reported religiosity, Biblical literalism, and dummy variables for several religious traditions and secular categories. Finally, Model 4 adds an interaction term for DRAP and attendance (reverse-coded) to test H3, which posits that the relationship between DRAP and support for violence will be more pronounced at lower levels of attendance. The four specifications are repeated in Models 5 through 8 (Table 4) using the two-item violence index (minus the Trump question) as the dependent variable.

Table 4. OLS regression models predicting support for political violence (2-item index)

*P < .05. **P < .01. ***< .001.

Models 1 through 3 provide strong support for H1. The DRAP index is positively and significantly correlated with the political violence index, even after controlling for other factors commonly associated with support for violence. In all three models, DRAP had the largest standardized coefficient (β = .223−.253; P ≤ .001). The relationship between DRAP and support for political violence is robust to changes in model specification. Neither the addition of a single measure of religiosity (attendance) in Model 2 nor the inclusion of the full slate of religion variables in Model 3 noticeably alters the size or significance of the coefficient. In substantive terms, a one-unit increase on the four-point DRAP index was associated with an increase in support for political violence of .180–.200, as measured on the 0–3 scale. Other significant predictors of support for violence included age (with younger respondents more supportive), gender (female respondents less supportive), frequency of Internet use, education, and income (with less educated and less wealthy respondents more supportive).

Models 5 through 7 provide additional support for H1. The dependent variable is the two-item violence index, with the question referencing Donald Trump removed. Once again, DRAP is significantly and positively correlated with support for political violence, regardless of model specification. In each model, it has the second-largest standardized coefficient (β = .179−.198; P ≤ .001), with only age offering more explanatory power. (Other significant control variables were, again, gender, frequency of Internet use, education, and income.)

Models 2 and 3, as well as Models 6 and 7, lend support to H2. In sum, traditional religion variables appear to be generally uncorrelated with support for political violence after accounting for the effects of the DRAP index. The lone exception is self-reported importance of religion, which shows a mild negative correlation (P ≤ .05) with support for violence in Models 3 and 7 (which include the full slate of religion variables). We would urge caution in interpreting this finding, however, due to the possibility of suppression effects as described above.

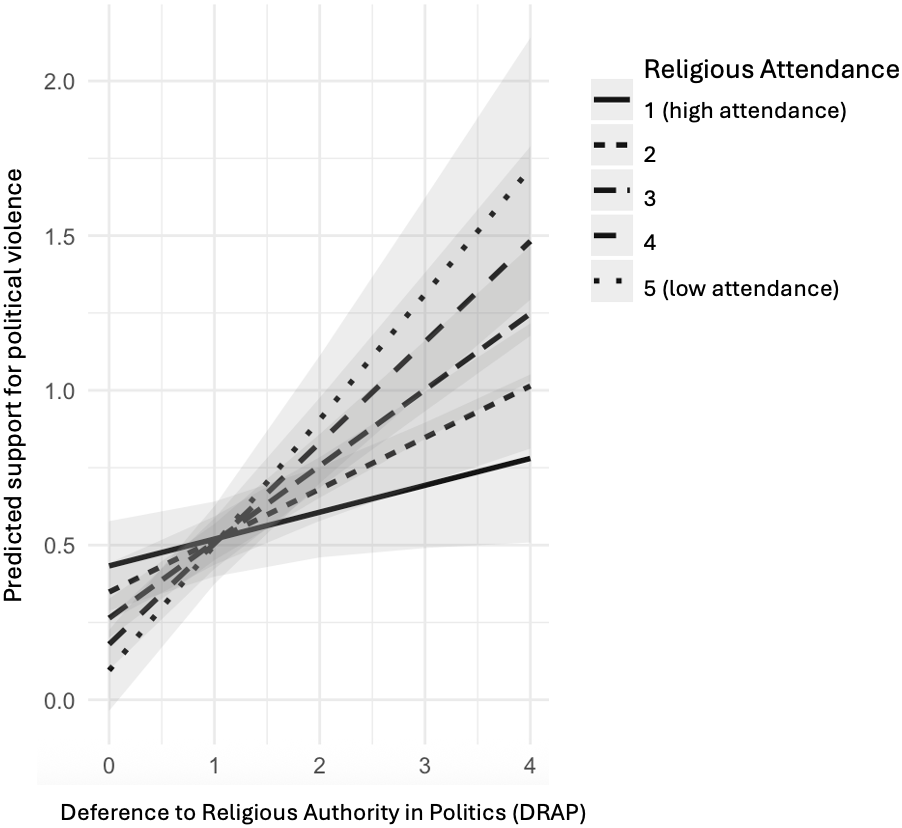

Models 4 and 8 provide strong support for H3, which posits that the relationship between DRAP and support for violence will be more pronounced at lower levels of religious attendance. The interaction term (DRAP X reverse-coded religious attendance) produces the largest standardized coefficient in Model 4 (β = .274; P ≤ .001) as well as Model 8 (β = .249; P ≤ .001), indicating that, all else being equal, the combination of low attendance and high self-reported deference to religious authority is strongly predictive of support for violence (whether measured using the 2- or 3-item index). As a robustness check, and to address the possibility of suppression effects, the appendix reports models without the full slate of religion variables used in Models 4 and 8. The results, reported in Table A1, make clear that the positive relationship between the interaction term and support for violence is robust to changes in model specification. Indeed, the interaction term produced the largest standardized coefficient in both models (β = .283−.299; P ≤ .001).

The Model 4 interaction between deference to religious authority and religious attendance is graphically displayed in Figure 2. The figure makes clear that low attendance bolsters the relationship between deference to authority and support for political violence. While deference to religious authority is associated with higher levels of support for political violence across all levels of religious attendance, the substantive impact of deference is weakest in the case of regular attenders and strongest in the case of non-attenders. For regular attenders, the difference between answering negatively to all religious authority questions and answering positively to all religious authority questions equates to an increase of a little more than 25 points on the three-point political violence scale. For low attenders, in contrast, the difference in predicted support for violence between low- and high-deference individuals amounts to more than 1.5 points on the three-point violence scale.

Figure 2. Predicted support for political violence by deference to religious authority and religious attendance.

Discussion

DRAP, as measured by our DRAP index, is clearly a powerful predictor of support for political violence. All else being equal, individuals who say they look to religious figures for guidance when making decisions about political matters are far more likely than other respondents to view violence as an acceptable way of advancing political goals in at least some circumstances. Moreover, the variables traditionally used to measure religious commitment (e.g. attendance, self-described importance of religion, and Biblical literalism) are generally uncorrelated with support for political violence once our new measure of religious authority is introduced into the analysis. Together, these findings suggest the need to rethink existing approaches to studying the relationship between religiosity and support for political violence. Where scholars have traditionally focused on individual religious behavior or group beliefs as potential drivers of support for violence, our analysis indicates that an individual’s propensity to seek religious guidance about political matters—which appears to cut across religious traditions—is a stronger predictor.

At the same time, we remain open-minded about exactly what the DRAP index is measuring. Clearly, many respondents who score high on our measure of religious authority are subject to authority of the sort traditionally exerted by religious groups over their members. However, a small but hardly insignificant number of low-religiosity respondents—those who attend services rarely, do not believe in the literal truth of the Bible, or do not consider themselves religious—exhibit moderate to high levels of deference to religious authority. These low-religiosity respondents are obviously not subject to religious authority in the traditional sense. And yet, looking at attendance specifically, we find that the combination of low religious attendance and self-reported deference to religious authority is particularly predictive of support for violence.

This finding invites attention to the question of where Americans are receiving religious guidance about politics, if not via participation in organized religious groups. At present, we lack adequate data to answer this question. However, there is growing evidence that social media, streaming platforms, and other online sources of information are beginning to rival traditional congregational activities as sources of religious information and influence (Burge and Williams, Reference Burge and Williams2019; Myers et al., Reference Myers, Syrdal, Mahto and Sen2023). Relatedly, a growing number of ostensibly secular online influencers and commentators, many of whom boast followings in the millions, are now incorporating religious arguments and appeals in their critiques of contemporary American society (Soloveichik, Reference Soloveichik2024; Sykes and Hopner, Reference Sykes and Hopner2024). Finally, there is evidence that the algorithms used by YouTube and similar sites promote religious content to users who have viewed socially conservative videos, even if the user has not previously shown interest in religion (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Cooper, Bhatnagar and Gatewood2024). It is worth exploring the possibility that low-religiosity respondents who score high on the DRAP index perceive themselves as receiving religious guidance about politics, not from ministers, priests, or rabbis, but via consumption of media and social media touching on religious themes.Footnote 9

The CSAF data offers some preliminary evidence to suggest that, among believers, the amount of time spent online is correlated with higher scores on the DRAP index. Looking only at respondents who reported that religion was “somewhat” or “very” important to them, Figure A1 displays stacked bar graphs reporting the number of positive DRAP responses by party affiliation and frequency of Internet use. The clear takeaway is that among Republicans and (to a lesser extent) independents, believers in the highest category of online activity were noticeably more likely than others to say that they defer to religious guidance when making decisions about politics. (Among religious Democrats, there appears to be no relationship between frequency of Internet usage and self-reported deference to religious authority.)

Lastly, it is worth asking whether some of what we are capturing is simply an expressive preference for the idea of religious authority or guidance. As Democratic identifiers have grown more secular relative to Republican identifiers, there is some evidence that rank-and-file Republicans are now identifying with labels that evoke traditional social values, even in cases where there is no real-world connection to the identity in question. For example, a surprising number of secular conservatives now tell survey researchers that they identify as “evangelical”—a label traditionally reserved for devout, theologically conservative Protestants (Burge, Reference Burge2024). We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that some individuals who score high on the DRAP measure are simply expressing approval of religious authority figures in general (on the grounds that they are part of the conservative “team”), or else seeking to differentiate themselves from a Democratic party they view as overwhelmingly secular.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that researchers examining the relationship between religiosity and political extremism should consider including a measure of deference to religious authority in their models. There is growing evidence that deference to religious authority is an important predictor of political attitudes and behavior (e.g. Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Gainous and Wagner2021), and it appears this tendency cannot be accurately captured via the use of proxies, such as Biblical literalism or worship attendance (Burge and Djupe, Reference Burge and Djupe2022). The logical next step, which we have attempted here, is to measure respondents’ levels of deference to authority directly—that is, by asking them whether, and to what extent, religious guidance shapes their political behavior and beliefs.

More work is needed, however, to understand precisely what survey respondents mean when they say they defer to religious guidance (or that it is desirable to defer to religious guidance) when making decisions about political matters. In future research, we hope to investigate the relative importance of traditional (e.g. congregational or group-centered) religious authority vis-à-vis online influencers and other non-traditional sources of religious guidance. Relatedly, we hope to explore the possibility that an expressive preference for religious authority may be shaping responses to the DRAP questions. Finally, given the strong correlation between DRAP scores and approval of political violence, it is important to ask whether deference to religious authority predicts, or is otherwise related to, other anti-democratic or authoritarian attitudes. For example, the 2024 iteration of the CSAF did not include the traditional authoritarianism scale questions, nor did it include questions on Christian nationalism. We look forward to investigating how these variables relate to the DRAP measure in future work.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S175504832610025X

Data availability statement

The dataset that supports the findings of this study is available at the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hannah Ridge, Mohammad Isaqzadeh, Lewis Luartz, the anonymous reviewers at Politics and Religion, and the participants of the Chapman Political Science department’s Works in Progress seminar for their helpful feedback and suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.