Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental condition, arising in childhood and defined by developmentally inappropriate inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that disrupts day-to-day functioning. Reference Sayal, Prasad, Daley, Ford and Coghill1,Reference Franke, Michelini, Asherson, Banaschewski, Bilbow and Buitelaar2 Although heritability is high, causal pathways remain incompletely understood: best estimates place prevalence between 2 and 7%. Reference Sayal, Prasad, Daley, Ford and Coghill1,Reference Franke, Michelini, Asherson, Banaschewski, Bilbow and Buitelaar2 Genetic susceptibility (e.g. polymorphisms in dopaminergic transporters and receptors) interacts with environmental exposures (such as obesity, early traumatic brain injury or family adversity) to shape neurodevelopmental risk. Reference Sayal, Prasad, Daley, Ford and Coghill1,Reference Franke, Michelini, Asherson, Banaschewski, Bilbow and Buitelaar2

The klotho gene encodes a pleiotropic protein with recognised roles in ageing, metabolism and the nervous system. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Alex, Buss, Davis, Campos, Donald and Fair4 In early life, klotho appears to support neurodevelopment. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Alex, Buss, Davis, Campos, Donald and Fair4 Heterozygosity for the KL-VS haplotype (rs9536314 F352V and rs9527025 C370S) elevates circulating klotho and has been related to better cognitive performance, including executive function, attention and episodic memory, and larger frontotemporal cortical volumes. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Alex, Buss, Davis, Campos, Donald and Fair4 Neuroimaging work further implicates the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, one of the hub regions related to executive function, and to working memory and processing speed, with KL-VS-related volumetric differences. Reference Yokoyama, Sturm, Bonham, Klein, Arfanakis and Yu5

A meta-analysis of ten studies on associations between klotho levels and various neuropsychiatric conditions (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and psychosocial stress) found reduced klotho levels in bipolar disorder, depression and psychosocial stress but increased levels in schizophrenia. Reference Birdi, Tomo, Sharma, Yadav, Charan and Sharma6 Evidence also suggests that inflammatory stress, which is commonly observed among patients with ADHD, significantly reduces klotho expression in both the brain and peripheral organs (i.e. kidneys and intestine). Reference Ohyama, Kurabayashi, Masuda, Nakamura, Aihara and Kaname7,Reference Schnorr, Siegl, Luckhardt, Wenz, Friedrichsen and El Jomaa8 Garre-Morata et al assessed the effect of methylphenidate on klotho levels among 59 children and adolescents with ADHD, and found a surprisingly non-significant decrease in klotho levels following a 3-month treatment regimen. Reference Garre-Morata, de Haro, Villén, Fernández-López, Escames and Molina-Carballo9 However, no study has investigated differences in klotho levels between patients with ADHD and healthy individuals. Reference Garre-Morata, de Haro, Villén, Fernández-López, Escames and Molina-Carballo9

We therefore examined whether adolescents with ADHD show reduced circulating α-klotho levels relative to healthy adolescents, and whether reduced klotho levels may be further related to executive dysfunction. We hypothesised lower klotho in ADHD and an inverse association between klotho and executive function.

Method

Participants and study procedure

We enrolled 92 adolescents (aged 12–17 years) diagnosed with ADHD by board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists according to DSM-5 criteria, along with 80 age-matched healthy adolescents recruited from nearby junior and senior high schools through bulletin board advertisements. All participants were interviewed by board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. Exclusion criteria included autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder; eating or organic mental disorders; severe autoimmune disease; epilepsy; cerebrovascular disease; pregnancy or breastfeeding; and unstable medical illness. Healthy adolescents had no DSM-5 diagnosis. Their parents completed the parent-reported Swanson, Nolan and Pelham IV (SNAP-IV) scale and the Child Behavior Checklist-Dysregulation Profile (CBCL-DP). Reference Gau, Shang, Liu, Lin, Swanson and Liu10,Reference Holtmann, Buchmann, Esser, Schmidt, Banaschewski and Laucht11

Ethical standards

Procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. The Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital approved the study (approval no. 2020-07-010A). Written informed consent was obtained from both participants and their parents/guardians.

Measurement of klotho

Fasting serum was collected in serum separator tubes, allowed to clot for 30 min and stored at −80 °C. Serum soluble α-klotho was quantified using the Human klotho DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (no. DY5334-05; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The assay standard range was 78.1–5000 pg/mL (100 µL sample), with a minimal detectable concentration of approximately 50 pg/mL. Absorbance at 450 nm was read on a Bio-Tek PowerWave Xs and analysed using KC junior software. Standard curves showed linear regression R 2 ≥ 0.95. Raw concentrations are provided in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10969.

Assessment of executive function

Executive control was evaluated using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), a widely used measure of mental set-shifting, strategic search, feedback utilisation and goal-directed behaviour. We analysed standard indices, including trials to first category and percentages of perseverative and non-perseverative errors. WCST was commonly used in our previous studies. Reference Chen, Hsu, Huang, Tsai, Tu and Bai12,Reference Chen, Kao, Chang, Tu, Hsu and Huang13

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using F-tests, and categorical variables by Pearson χ 2 tests. Because klotho distributions were non-normal by Kolmogorov–Smirnov testing, values were log-transformed. Generalised linear models (GLMs) were used to assess (a) group differences in klotho and WCST indices and (b) associations between klotho and executive function, adjusting for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), SNAP-IV, CBCL-D and ADHD medication use. Model adequacy was evaluated using residual deviance, the Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion, which showed that model assumptions had been met. We additionally compared klotho among drug-naïve ADHD, medicated ADHD and control groups. Two-tailed α was 0.05. For 4 secondary WCST comparisons, a Bonferroni-adjusted threshold of 0.0125 was applied. All data processing and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 17 for Windows.

Results

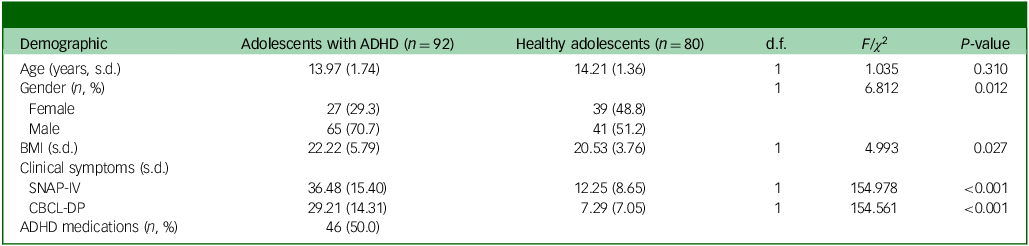

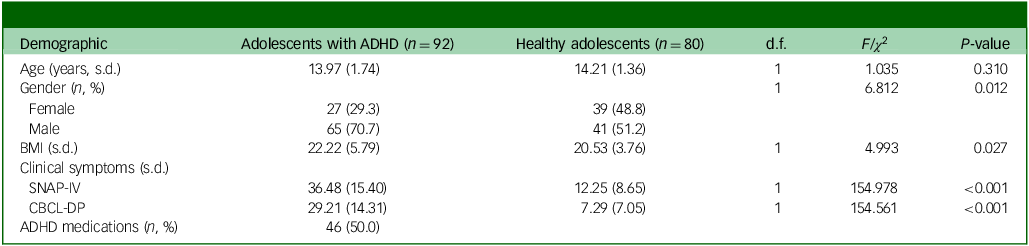

Table 1 shows a comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescents with ADHD with those of healthy adolescents, with a mean age of approximately 14 years. The ADHD group was male-predominant (70.7%) and had significantly higher scores for SNAP-4 (P < 0.001) and CBCL-DP (P < 0.001) compared with the control group (Table 1). Among adolescents with ADHD, 46 (50%) had been prescribed ADHD medications (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of groups

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BMI, body mass index; SNAP-IV, Swanson, Nolan and Pelham Rating Scale IV; CBCL-DP, Child Behavior Checklist-Dysregulation Profile.

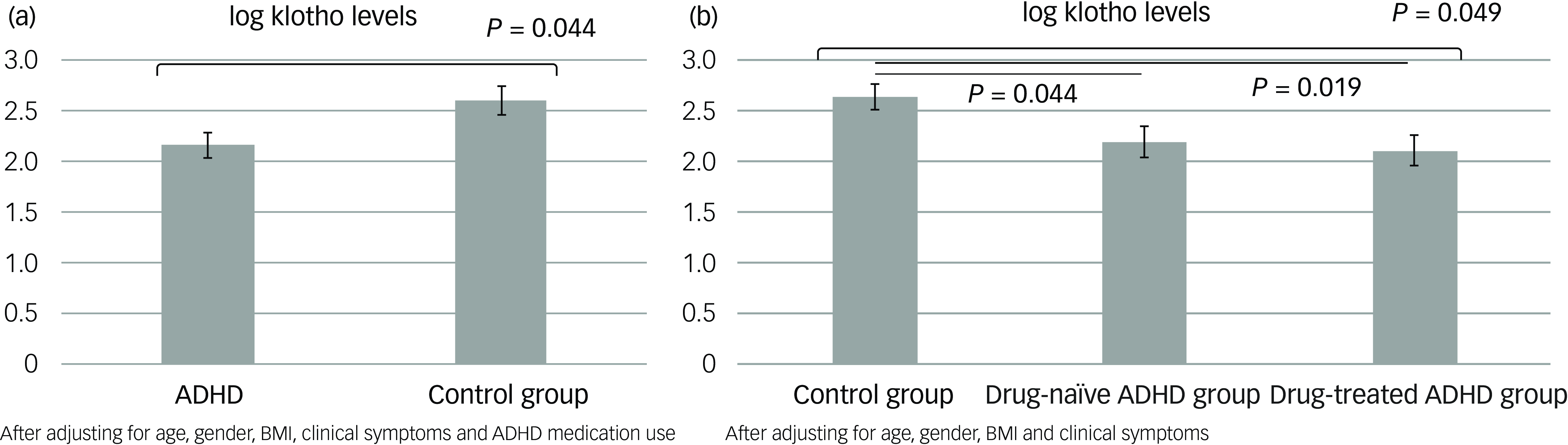

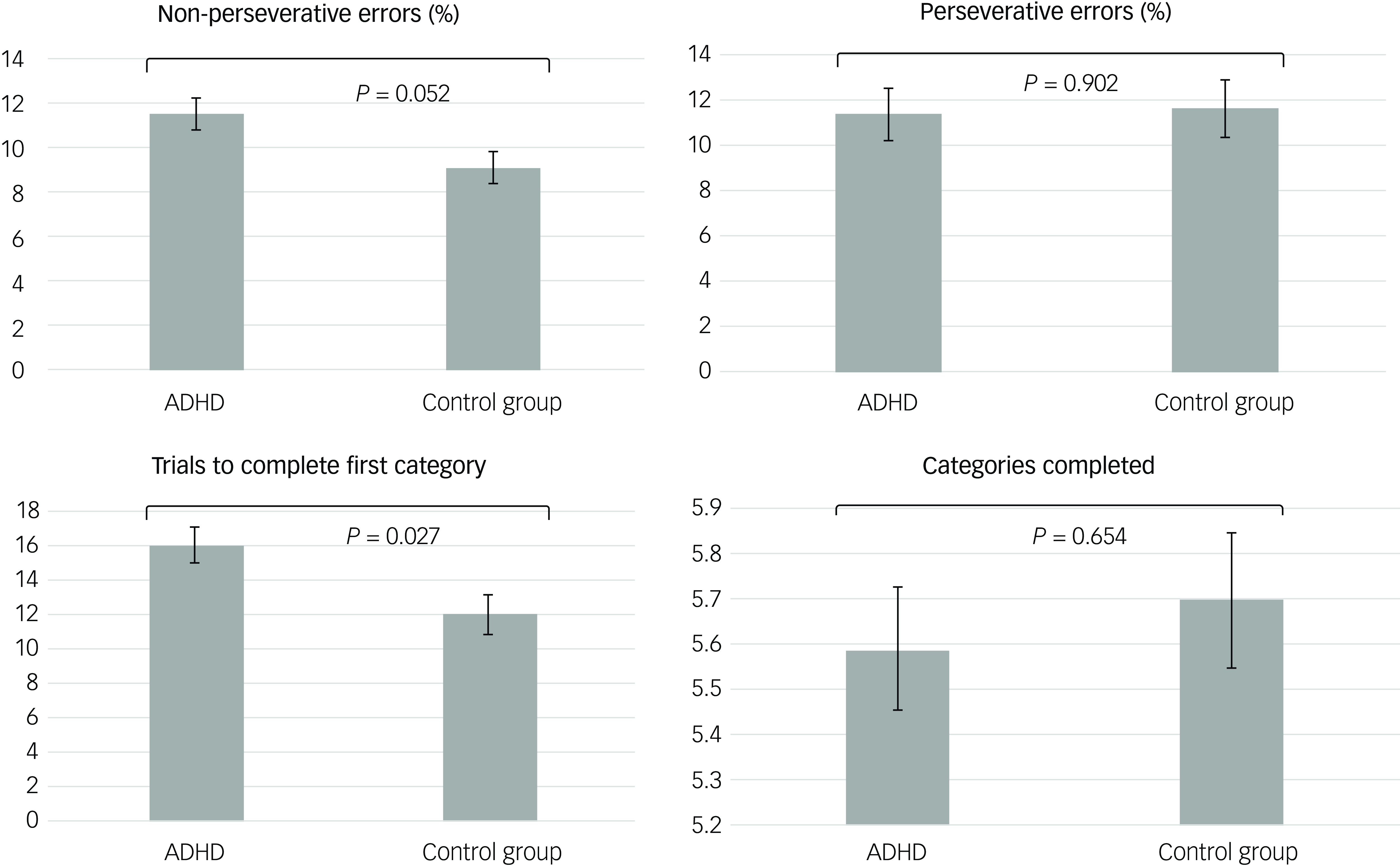

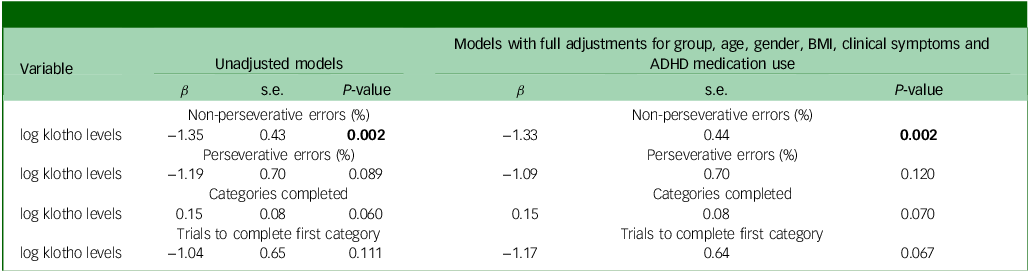

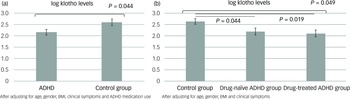

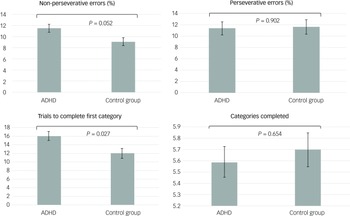

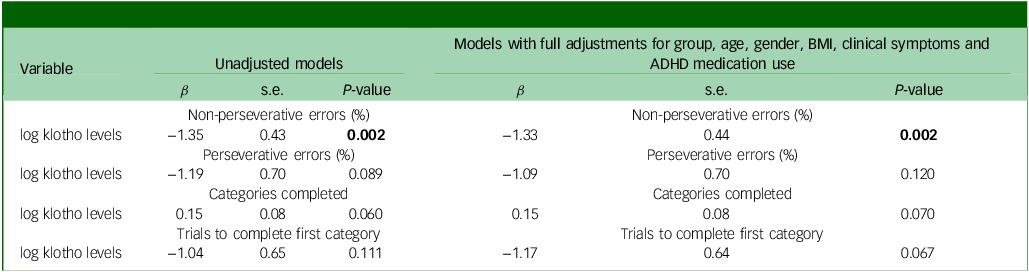

The GLMs, adjusted for age, gender, BMI, clinical symptoms and ADHD medication use, demonstrated that adolescents with ADHD had significantly lower levels of klotho (P = 0.044) and performed worse on WCST, especially with regard to increased trials to complete the first category (P = 0.027), compared with healthy adolescents (Figs 1(a) and 2). In addition, both the drug-naïve (P = 0.044) and drug-treated (P = 0.019) ADHD groups exhibited lower levels of klotho than the control group (Fig. 1(b)), with no difference in levels between the two ADHD groups. Finally, lower klotho concentrations were associated with a higher percentage of non-perseverative errors on WCST following covariate adjustment (P = 0.002), an effect surviving Bonferroni correction (α = 0.0125). These results are summarised in Table 2.

Fig. 1 Estimated klotho levels based on the generalised linear models: (a) between the ADHD and control groups and (b) among the drug-naïve and drug-treated ADHD and control groups. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BMI, body mass index.

Fig. 2 Estimated executive function based on the generalised linear models after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, clinical symptoms and ADHD medication. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2 Associations between klotho levels and executive function using generalised linear models

BMI, body mass index; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Bold type indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Discussion

We found that adolescents with ADHD had reduced circulating α-klotho compared with healthy peers, independent of demographics, adiposity, clinical symptom burden and current medication, which may suggest klotho as a trait marker of ADHD. In addition, klotho levels were negatively associated with the percentage of non-perseverative errors on WCST, indicating a correlation between lower klotho levels and worse executive function. Following Bonferroni correction for 4 comparisons, the significance threshold was adjusted from α = 0.05 to 0.0125; the association between klotho levels and percentage non-perseverative errors remained significant (P = 0.002 < 0.0125), indicating a robust relationship between klotho and executive function.

Studies of klotho have primarily been conducted among middle-aged and older adults, due to its known age-suppressive qualities. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Alex, Buss, Davis, Campos, Donald and Fair4 In the current decade, the neurodevelopmental role of klotho has gained scientific and clinical attention, which may reflect evidence linking neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Alex, Buss, Davis, Campos, Donald and Fair4 Increasing evidence suggests that klotho levels are associated with those of psychological stress and cognitive function in young people. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Birdi, Tomo, Sharma, Yadav, Charan and Sharma6,Reference Beckner, Conkright, Eagle, Martin, Sinnott and LaGoy14 Using in situ hybridisation, Clinton et al found that levels of klotho messenger RNA expression among developing and adult rat brains in regions such as the cortex, hippocampus and amygdala increased during the first week of life, decreased during the second week and then gradually increased again to reach adult levels by postnatal day 21. Reference Clinton, Glover, Maltare, Laszczyk, Mehi and Simmons15 Beckner et al assessed klotho levels and cognitive function in 54 young service members who underwent a 5-day simulated military training protocol that included daily physical exertion and 48 h of restricted sleep and caloric intake, which led to a 7.2% reduction in klotho levels and a 5.6% decrease in working memory. Reference Beckner, Conkright, Eagle, Martin, Sinnott and LaGoy14 A klotho genotyping neuroimaging study of 1387 children and adolescents aged 3–21 years found that individuals carrying KL-VS heterozygotes had better cognitive function, including executive function and attention, than those without, particularly before the age of 11 years. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3 Gupta et al found that klotho acutely increased synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus in male mice, in a histological pattern similar to that in individuals undergoing cognitive stimulation, suggesting that klotho had enhanced cognition in young mice and countered cognitive deficits in older mice. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3 The findings of de Vries et al and Gupta et al imply that insufficient klotho levels may lead to impaired attention and executive function, an endophenotype of ADHD, during critical neurodevelopmental periods. Reference de Vries, Staff, Noble, Muetzel, Vernooij and White3,Reference Gupta, Moreno, Wang, Leon, Chen and Hahn16

Our study results suggested that reduced klotho levels may serve as a trait marker of ADHD and related executive dysfunction, independent of clinical symptoms and ADHD medication use. Siahanidou et al measured klotho levels in 50 healthy neonates – 25 preterm (with a mean gestational age of 33.7 weeks) and 25 full-term – on days 14 and 28 of life, and found that these were significantly higher in full-term compared with preterm infants at both time points. Reference Siahanidou, Garatzioti, Lazaropoulou, Kourlaba, Papassotiriou and Kino17 A preclinical study of postnatal day 10 mice reported that hypoxic injury decreased hippocampal klotho levels at post-injury day 4. Reference Herrmann, Kochanek, Vagni, Janesko-Feldman, Stezoski and Gorse18 Preterm and neonatal hypoxia are believed to be risk factors for ADHD. Reference Franz, Bolat, Bolat, Matijasevich, Santos and Silveira19,Reference Bala, Bala, Pell and Fleming20 Furthermore, Lian et al found that klotho reduced oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury caused by sevoflurane in the hippocampus of newborn rats. Reference Lian, Lu, Zhao, Zou, Lu and Zhou21 Xie et al reported that neonatal exposure to sevoflurane may lead to impulse control deficits in mice by disrupting excitatory neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex. Reference Xie, Liu, Hu, Wang, Zhu and Jiang22 Prather et al linked klotho levels with chronic psychological stress, indicating that high-stress individuals exhibited lower klotho levels compared with low-stress. Reference Prather, Epel, Arenander, Broestl, Garay and Wang23 Schnorr et al identified an inflammatory biotype of ADHD that presented with increase in both chemokine signalling and the NF-κB pathway, and was associated with chronic stress as measured by the perceived stress scale. Reference Schnorr, Siegl, Luckhardt, Wenz, Friedrichsen and El Jomaa8 Other studies have shown a significant association between high levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity and a high level of perceived stress. Reference Salla, Galera, Guichard, Tzourio and Michel24,Reference Oster, Ramklint, Meyer and Isaksson25 These findings indirectly suggest a potential association between klotho and ADHD, indicating that early childhood adversity and psychological stress, combined with insufficient klotho levels, may increase vulnerability to ADHD. However, the findings of our cross-sectional study are insufficient to confirm a causal association among klotho levels, ADHD and executive dysfunction. Reference Siahanidou, Garatzioti, Lazaropoulou, Kourlaba, Papassotiriou and Kino17 Longitudinal studies would be required to validate our findings.

Our study has several limitations. First, we assessed executive function using only the association between WCST performance and klotho levels. Additional research would be required to evaluate associations between klotho levels and other aspects of cognitive function, such as inhibitory control and working memory. Second, although previous studies have shown a high correlation between ADHD symptoms and perceived psychological stress, we did not assess perceived psychological stress among those adolescents with ADHD who participated in our study, and we compared klotho levels between groups only after adjusting for clinical symptoms. Further research would be necessary to clarify an association among klotho levels, perceived psychological stress and ADHD symptoms. Third, given the Barkley model of ADHD as an executive function deficit disorder, Reference Barkley26,Reference Castellanos and Tannock27 it is difficult to determine whether lower klotho levels are specific to ADHD per se or, rather, reflect executive dysfunction more broadly. The potential transdiagnostic role of reduced klotho levels in executive dysfunction warrants further investigation. Fourth, we focused on soluble α-klotho because it is the predominant circulating form, with validated serum ELISAs and the clearest prior links to cognition/executive function. By contrast, β- and γ-klotho act mainly as membrane co-receptors for endocrine fibroblast growth factors, have low/uncertain circulating levels and lack widely standardised serum assays and reference ranges. Further research would be warranted to clarify the associations of β- and γ-klotho with ADHD and executive function. Fifth, whether the observed reduction in klotho among adolescents with ADHD may generalise to adults with ADHD remains to be determined.

In conclusion, adolescents with ADHD exhibited decreased klotho levels compared with healthy adolescents following adjustments for demographic characteristics, clinical symptoms and ADHD medication use. In addition, lower klotho levels were associated with higher executive dysfunction, indicating that klotho may serve as a trait marker of ADHD. The exact neuromechanisms underlying the association among klotho, ADHD and executive function require further investigation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10969

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. However, these data are not publicly accessible due to ethical regulations in Taiwan.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank I-Fan Hu, MA (Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London; National Taiwan University) for his friendship and support; he declares no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

M.-H.C. designed the study, analysed the data and drafted the paper. L.-C.C., J.-W.H., S.-J.T. and Y.-M.B. performed the literature review, critically reviewed the manuscript and interpreted the data. All authors contributed substantially to the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission. All authors are responsible for the integrity, accuracy and presentation of the data.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (nos V112C-033, V113C-039, V113C-011); Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (nos CI-113-32, CI-113-30); Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (nos MOST110-2314-B-075-026, MOST110-2314-B-075-024-MY3, MOST109-2314-B-010-050-MY3, MOST111-2314-B-075-014-MY2, MOST111-2314-B-075-013, NSTC111-2314-B-A49-089-MY2, NSTC113-2314-B-075-042); Taipei, Taichung, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital; Tri-Service General Hospital; Academia Sinica Joint Research Programme (nos VTA112-V1-6-1, VTA113-V1-5-1); and Veterans General Hospitals and University System of Taiwan Joint Research Programme (nos VGHUST112-G1-8-1, VGHUST113-G1-8-1). The funding sources had no role in any process of the study.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.