Introduction

Across the transition into adolescence, changes in a child’s social world give rise to escalating peer influence. As adult supervision declines and time with agemates grows (Simpkins et al., Reference Simpkins, Gülseven and Vandell2024), youth become increasingly susceptible to peer influence. Close friends (Laursen & Faur, Reference Laursen and Faur2022) and popular peers (Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Cillessen, Lindenberg and Veenstra2010) are particularly salient sources of influence. Concerns about untoward peer influence are widespread, yet efforts to address it are hindered by a dearth of detail. Critically, nothing is known about the relative magnitude of friend and popular peer influence. Nor have scholars considered the possibility that the scope of each varies across behavioral domains. The present study assays self-reports and peer reports of social, emotional, and academic achievement in a large sample of primary and middle school youth to test the hypothesis that different peers exert different amounts of influence over different forms of behavior. Specifically, we examine the degree to which youth conform to best friends and to popularity-driven classroom norms.

Developmental shifts in peer influence

Peer influence describes a process whereby individuals act or think in ways that they would not otherwise act or think in response to experiences with agemates (Laursen, Reference Laursen, Bukowski, Laursen and Rubin2018). We focus here on the transition into adolescence, when peer influence is assumed to peak (Laursen & Veenstra, Reference Laursen and Veenstra2023). Changes in the social world, marked by a rapid expansion of unsupervised time with peers, create uncertainty about how to behave. Uncertainty, in turn, breeds conformity as individuals look to others to inform their actions and avoid social missteps (Berger, Reference Berger, Prinstein and Dodge2008). Other developmental changes also foster conformity. For example, uneven neurological maturation gives rise to processing vulnerabilities and reward-seeking behaviors that favor risk-taking in the company of peers (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2005). Identity exploration may also elicit conformity. Adopting the behaviors and norms of different peers and peer groups allows adolescents to sample and exchange varied identities (Kerpelman & Pittman, Reference Kerpelman and Pittman2001).

During the early and mid-adolescent years, before the rise of romantic relationships, peer influence is typically attributed to either best friends or peer group norms. The two are distinct. Friends represent horizontal, dyadic relationships that are premised on egalitarian sharing and need fulfillment (Laursen & Hartup, Reference Laursen and Hartup2002). Consequential interactions between friends usually take place in private settings. Best friends represent the most important friends (Berndt, Reference Berndt1982), proffering intimacy, unique rewards, and camaraderie. Presumably, this makes best friends more influential than other friends. Peer group norms represent behavioral expectations premised on hierarchy or status-based social structures (Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Lindenberg and Veenstra2008). Consequential interactions between group members usually take place in public settings. Two forms of peer group norms have been identified. Status-based norms describe the behavior of the most popular members of the group, purportedly modeling and enforcing how members should behave to gain approval and avoid sanctions. Descriptive norms describe the average behavior of all members in the group, purportedly representing how most or typical members behave. Status-based norms are usually stronger than descriptive norms (Veenstra & Lodder, Reference Veenstra and Lodder2022), so our focus here is on the former.

To recap: Friends and peer groups play key roles in the social lives of adolescents. Both should influence adaptive behaviors. However, the mechanisms of influence and the settings in which influence is exerted differ across these two sources of influence, raising the prospect that each may influence different behaviors to different degrees.

Cognitive strategies that inform peer influence

Conceptual models and empirical studies typically focus on one source of peer influence or the other, treating each as independent and unique. Few theories and almost no research have considered the possibility that sources of influence overlap and potentially compete. We suspect that there are systematic differences in the magnitude of influence ascribed to each, such that status-based norms drive conformity over some behaviors and best friends drive conformity over others.

The Algorithms of Social Life Model (Bugental, Reference Bugental2000) informs our thinking about potential variations in sources of peer influence. In this model, algorithms represent evolved mental strategies designed to help individuals navigate the social world through the provision of context-sensitive, rule-guided responses for addressing problems and attaining goals (Cacioppo & Tassinary, Reference Cacioppo and Tassinary1990). Algorithms should be particularly important during the transition into adolescence. The power vacuum created by retreating adult oversight results in a social world dominated by peers; new behavioral rules and coping strategies are required for adaptive success (Bugental et al., Reference Bugental, Corpuz, Beaulieu, Grusec and Hastings2015). Two algorithms are particularly relevant: 1) reciprocity, which guides behavior within egalitarian peer relationships, and 2) hierarchy, which guides behavior within power-imbalanced peer relationships.

The reciprocity algorithm addresses egalitarian relationships in which participants expect fair and equitable exchanges. During late childhood and early adolescence, friendships are a particularly salient form of egalitarian relationships, characterized by mutuality, responsiveness, and intimacy. Short-term inequities are tolerated because friends are expected to meet one another’s needs, but in the long run the rewards of participation must outweigh the costs (Laursen & Hartup, Reference Laursen and Hartup2002). As a consequence, participants must learn to balance the demands of the relationship against personal advantage, with rules that guide conduct toward this goal. Conformity is an important tool for maintaining friendship harmony and stability (Laursen & Veenstra, Reference Laursen and Veenstra2021). Conformity fosters similarity, increasing opportunities for rewarding experiences through shared activities and reducing differences that can lead to disagreement and relationship disruption. It follows that during adolescence the reciprocity domain algorithm encourages conformity to friends as a strategy for preserving benefits. The algorithm should be particularly salient in best friend relationships, where investments are significant and rewards are not easily replaced.

The hierarchy algorithm addresses power-imbalanced relationships in which the participants occupy roles that are (at least implicitly) understood to be dominant or subordinate. During late childhood and early adolescence, peer groups are a particularly salient form of power-imbalanced relationships, characterized by leaders, who allocate resources and make decisions on behalf of the group, and followers, who accept and implement the decisions of leaders in an attempt to gain favor (and perhaps raise their own standing in the group). Popular peers tend to be group leaders (Cillessen et al., Reference Cillessen, Mayeux, Ha, de Bruyn and LaFontana2014). They establish group norms that serve as guidelines for individual behavior. Popular peers enforce group norms through the preferential allocation of resources to those who conform (Hawley, Reference Hawley1999). Nonconformists run the risk of being labeled social misfits; leaders can and do exclude social misfits from the group (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Giammarino and Parad1986). Social exclusion is particularly fraught during early adolescence, giving rise to friendlessness, loneliness, victimization, and internalizing problems (see Killen et al., Reference Killen, Rutland, Rizzo, McGuire, Rubin, Bukowski and Laursen2011). It follows that during adolescence, the hierarchy algorithm encourages conformity to status-based norms as a strategy for maintaining a position in the group.

The Algorithms of Social Life model (Bugental, Reference Bugental2000) asserts that different peers practice different forms of influence. In the case of the reciprocity algorithm, peers in important egalitarian relationships should exercise influence through appeals to loyalty, intimacy, and fun. Conformity is often a product of negotiation and benefit exchange between partners who are wary of widening dissimilarities that could provoke relationship dissolution. In the case of the hierarchy algorithm, popular peers who occupy dominant positions in the peer group should influence those in subordinate positions through implicit means, by modeling expected behaviors, and through explicit means, by rewarding those who conform and sanctioning those who do not. Although the model implies that different peers influence different types of behavior, it does not specify how these differences are manifested. Absent conceptual guidance on this front, we refrain from offering hypotheses about which algorithms should prescribe which adaptive behaviors.

What is (and is not) known about friend and peer group norm influence

Conformity is a product of peer influence. Conformity serves the purpose of increasing similarity, which promotes compatibility between friends and promotes the smooth functioning of peer groups (Laursen, Reference Laursen2017). Friend influence enhances dyadic similarity; partners change in ways that increase resemblances. Popular peer influence enhances group homogeneity; members change in ways that increase resemblances either by becoming more similar to a specific popular peer or by more closely adhering to status-based norms. There is a wealth of longitudinal evidence to suggest that peer groups and friends shape the social and emotional behavior of children and adolescents. Longitudinal studies that examine the two sources of influence separately yield evidence that both friends and popularity-driven norms drive changes in individual weight-related cognitions and body mass (Rancourt et al., Reference Rancourt, Choukas-Bradley, Cohen and Prinstein2014; Simpkins et al., Reference Simpkins, Schaefer, Price and Vest2013), delinquency and disruptiveness (Sijtsema & Lindenberg, Reference Sijtsema and Lindenberg2018), and academic achievement and school engagement (Rambaran et al., Reference Rambaran, Schwartz, Badaly, Hopmeyer, Steglich and Veenstra2017; Shin & Ryan, Reference Shin and Ryan2014). Friends also influence internalizing symptoms (Neal & Veenstra, Reference Neal and Veenstra2021) and emotional regulation (Borowski & Zeman, Reference Borowski and Zeman2025), as does network centrality (an index of prominence in the group) and descriptive group norms (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Rancourt, Adelman, Burk and Prinstein2011). Finally, concurrent findings tie friend social media use and peer norms about social media use to the frequency of adolescent engagement with social media (Marino et al., Reference Marino, Gini, Angelini, Vieno and Spada2020); Unknown is the degree to which friends or peer group norms prospectively influence social media use during late childhood and early adolescence, although both have been hypothesized (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a, Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b).

Strategies for comparing sources of peer influence

To date, no longitudinal studies have directly compared the relative influence of friends with that of popular peers or popularity-driven status-based norms. Analytic obstacles make such comparisons difficult. Friend influence is often gauged through social network analysis procedures, which describe changes in resemblance to targets of outgoing nominations, either friends or popular peers; both cannot be included in the same model so direct comparisons are not possible. Status-based norm influence is typically gauged through multilevel modeling strategies, which describe the degree to which group members change to resemble a popularity-weighted index of a behavior (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Guerra, Huesmann, Tolan, VanAcker and Eron2000; Lessard & Juvonen, Reference Lessard and Juvonen2022). Multilevel modeling strategies can also be used to assess friend influence, which is measured at level one, whereas status-based norm influence is measured with a cross-level interaction; there is no obvious way to compare the magnitude of these effects. Friend influence can also be assessed using longitudinal Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) dyadic analyses. When modified for longitudinal data (Popp et al., Reference Popp, Laursen, Kerr, Stattin and Burk2009), APIM strategies gauge the degree to which similarity increases between friends.

The Group Actor Partner Interdependence Model (GAPIM; Kenny & Garcia, Reference Kenny and Garcia2012), is a variation of the APIM in which group effects are tested simultaneously with dyadic effects. Herein, we modify the GAPIM, capturing change using longitudinal data, to compare friend and status-based norm influence. Peer influence (best friends, in this case) is operationalized as an increase in behavioral similarity to more closely resemble that of the partner. Group influence (status-based norms, in this case) is operationalized as an increase in behavioral similarity to more closely resemble the popularity-weighted average of the peer group. Novel to the present study, the modified GAPIM simultaneously assesses the unique portions of best friend and status-based norm influence by removing their shared and overlapping variance.

The current study

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that different peers exert different amounts of influence over different behaviors. To this end, longitudinal GAPIM analyses examine the relative influence of best friends and status-based norms in a sample of Lithuanian middle school students. Separate analyses will specify the relative influence of each on academic achievement, emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity (a component of emotional regulation), problem behavior, social media use, and weight concerns. The choice of outcome variables was pragmatic. As indicated above, previous studies indicate that each is subject to influence from friends and popular peers. Theory and research suggest that friends and peer group norms are important sources of influence, but neither offers guidance as to which source of influence should dominate which type of behavior. Therefore, we refrain from advancing specific hypotheses about who should be most influential over what. Follow-up age comparisons will test the widely held assumption (Berndt, Reference Berndt1982; Steinberg & Monahan, Reference Steinberg and Monahan2007) that peer influence is greater during early adolescence (e.g., 7th–8th grades) than during late childhood (e.g., 5th–6th grade), although here too we refrain from offering hypotheses about behavior-specific variations in sources of influence.

Method

Participants

Participants included 543 students (268 girls, 275 boys) attending public middle schools (which encompass grades 5-8) in a mid-sized community in Lithuania. Students attended all classes with the same peers. Most of the same peers were classmates in previous school years. Teachers rotated between classes. Nearly all students were ethnic Lithuanian. The final sample included 86 fifth graders (M age = 10.82, SD age = 0.39), 212 sixth graders (M age = 11.73, SD age = 0.50), 102 seventh graders (M age = 12.84, SD age = 0.39), and 143 eighth graders (M age = 13.73, SD age = 0.44).

Procedure

Written parental consent and child assent were required to complete the surveys. Trained research assistants administered surveys to students on computer tablets in a quiet school setting. Participants completed identical self-report and peer nomination instruments twice during the same academic year, an average of 12.5 weeks apart, in September/October 2022 (fall, Time 1) and in February 2023 (winter, Time 2).

A total of 1,155 students from all 44 classes in all three middle schools in the community were invited to participate. To avoid bias in nomination data due to low participation, analyses were restricted to classrooms in which at least 60% of the students completed surveys (Bukowski et al., Reference Bukowski, Cillessen, Velásquez, Laursen, Little and Card2012). As a result, 15 classes (with 376 participants) were excluded from the analyses. The remaining 29 classes had an average participation rate of 71.2% (SD = 8.5%, range = 60.0%–90.0%). There were no statistically significant differences on any demographic or study variable between participants in classes that were and were not included in the study.

Measures were translated from English to Lithuanian by a bilingual team of research assistants and then back translated by a separate team. Differences were resolved through discussion. The study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (#6/-2020).

Measures

Peer nominations

Nomination rosters included all students in the classroom (participants and nonparticipants). Same- and cross-sex nominations were allowed.

Top-ranked best friends

Participants identified up to two rank-ordered best friends (“Who is your first best friend?” and “Who is your second best friend”) and up to five additional friends (“Who is your third best friend?” and so on) from a class roster including all students in the class, with the option to nominate unnamed students in other classes or schools (i.e., “My friend is not listed”). The 8 students who did not nominate any friends or only responded with the latter option were omitted from the analyses.

Top-ranked best friends were defined as classmates receiving the highest outgoing friend nomination from a participant in the fall (Time 1). Reciprocity was not a requirement; we assumed influence would be greatest among those perceived to be closest. To avoid unequal individual contributions to the data, participants were restricted to a single top-ranked friendship, prioritizing highest ranked ties. Of the 543 top-ranked best friends, 520 were first-ranked and 23 were second-ranked (their first-ranked friends being randomly assigned to someone else who ranked them similarly). This total included 90 nonparticipant classmates who were nominated as first-ranked friends. A similar number of participants (n = 496) and nonparticipants (n = 81) were nominated as top-ranked best friends in the winter (Time 2).

Peer reputation

Participants nominated an unlimited number of classmates (participants and nonparticipants) who best fit the following descriptors “Someone who does well in school” (academic achievement) and “Someone who is popular” (popularity). For the purpose of calculating class norms, all students in each class (participants and nonparticipants) received scores on these two peer reputation variables. The number of nominations a student received was summed and standardized using a regression-based procedure that accounts for class size (Velásquez et al., Reference Velásquez, Bukowski and Saldarriaga2013). Because each informant in a peer nomination procedure is treated as a separate indicator, single-item peer nomination data are considered reliable (Bukowski et al., Reference Bukowski, Cillessen, Velásquez, Laursen, Little and Card2012), particularly for visible attributes such as academic achievement and popularity (Babcock et al., Reference Babcock, Marks, Crick and Cillessen2014).

Self-reports

All items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Item scores were averaged.

Emotional problems

Participants completed six items from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997) assessing internalizing symptoms (e.g., “I have many fears and am easily scared”). Internal reliability was acceptable (α = .87–.92).

Lack of emotional clarity

Participants completed three items from the Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale Short Form (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Xia, Fosco, Yaptangco, Skidmore and Crowell2016), which assesses the extent to which individuals are uncertain about their affective experiences (e.g., “I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings”). Internal reliability was excellent (α = .92–.92).

Problem behaviors

Participants completed five items from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, Reference Goodman1997) assessing conduct problems (e.g., “I break rules at home, school, or elsewhere”). Internal reliability was good (α = .82–.86). Participants also completed five items from the Bergen Questionnaire on Antisocial Behavior (Bendixen & Olweus, Reference Bendixen and Olweus2006) assessing delinquent behaviors (e.g., “In the past month, how often have you taken things from a store without paying?”). Internal reliability was excellent α=.89–.91). The 10 items from the two instruments were averaged to create a composite problem behavior score (α = .88–.89).

Social media use

Participants completed three items (Leggett-James & Laursen, Reference Leggett-James and Laursen2023) adapted from the Task Values Questionnaire (Eccles, Reference Eccles and Spence1983) assessing the frequency and importance of social media engagement [e.g., “I think it is important to be active on social media (i.e., Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, YouTube”)]. Internal reliability was good (α = .86–.86).

Weight concerns

Participants completed three items from the Eating Patterns Inventory for Children (Schacht et al., Reference Schacht, Richter-Appelt, Schulte-Markwort, Hebebrand and Chimmelmann2006) assessing weight-related cognitions (e.g., “I should try harder to lose weight”). Internal reliability was excellent (α = .91–.91).

Status-based norms

For each participant, separate status-based norms were calculated for six socioemotional adjustment outcomes (i.e., academic achievement, emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, problem behavior, social media use, and weight concerns), using an adapted network-based norm procedure (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Cappella and Neal2015). All students in each class (participant n = 543, nonparticipant n = 237) were included in the calculation of status-based norms. Each participant received a unique norm score for each adjustment outcome, which was operationalized as the weighted average of the fall (Time 1) adjustment outcome scores of all students (participants and nonparticipants) in the classroom (except the target student). To calculate this weighted average, each student’s fall (Time 1) adjustment outcome score was multiplied by their own fall (Time 1) popularity score. The product was summed and divided by the number of students in the class (excluding the target student): (Child A’s adjustment outcome score × Child A’s popularity score) + (Child B’s adjustment outcome score × Child B’s popularity score) + …] / (n class–1). Larger status-based norms indicate that popular students engaged in the behavior, suggesting pressure on classmates to exhibit similarly high levels of the behavior. Smaller status-based norms indicate that popular peers avoided the behavior, suggesting pressure on classmates to exhibit similarly low levels of the behavior.

Potential confounding variables

Supplemental analyses included fall (Time 1) covariates to isolate the unique contributions of friends and popular peers to conformity by removing variance from attributes associated with susceptibility to influence. Total number of friends (i.e., the sum of a participant’s outgoing friend nominations) was included because youth with few friends are more likely to conform than those with several friends (Faur et al., Reference Faur, Laursen and Juvonen2023). Three fall (Time 1) peer status variables [unpopularity (“Someone who is unpopular”), acceptance (“Someone who you like to spend time with”), and rejection (“Someone who you don’t like to spend time with”)] were included as covariates because each has been linked to susceptibility to peer influence (DeLay et al., Reference DeLay, Burk and Laursen2022; Dijkstra et al., Reference Dijkstra, Cillessen and Borch2013).

Missing data

Of the 543 participants who completed the peer nomination and self-report surveys in the fall (Time 1), 98.3% (n = 534) completed the surveys in the winter (Time 2). Because attrition was minimal (1.7%), there was insufficient power to detect statistically significant differences between participants with data at both time points and those with data at only one time point.

All students in the 29 classes received peer nominations, so there was no item-level or wave-level missingness for academic achievement or popularity (or any potential confounders). For self-report variables, (i.e., emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, problem behavior, social media, weight concerns), participant item-level missingness averaged 5.5% (range = 1.5–15.7%) in the fall (Time 1) and 6.1% (range = 0.4–19.7%) in the winter (Time 2). Nonparticipants (n = 237) did not complete self-report surveys; their scores at both time points were treated as wave-level missing. Thus, wave-level missingness accounted for 30.4% of classroom norm data and 16.6% of top-ranked friend data. There were no statistically significant differences between students with and without self-report data on any demographic or peer nomination study variable.

Little’s MCAR test (Little & Rubin, Reference Little and Rubin1987) indicated that data were missing completely at random, χ 2 (39) = 49.43, p = .12. Missing item-level data were handled with an EM algorithm with 25 iterations. Missing wave-level data were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation.

Plan of analysis

To test the hypothesis that different peers exert different amounts of influence over different behaviors, we evaluated the relative influence of top-ranked best friends and status-based norms with longitudinal GAPIM analyses, conducted in a structural equation model framework using Mplus v8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). The analyses followed a four-step procedure.

Model 1 depicts the actor-only model (see Supplemental Figure 1), which estimated the stability of the adjustment outcome for the target participant [actor path a: intrapersonal association from a fall (Time 1) adjustment variable to the same variable in the winter (Time 2)]. The inclusion of this path in subsequent models enables estimates of friend and status-based norm influence, because it removes the baseline stability of the behavior for the individual. The remaining variance represents the change from Time 1 to Time 2 (and error).

Model 2 depicts top-ranked best friend influence (see Supplemental Figure 1). The model included the estimate of individual stability (actor path a) and the estimate of top-ranked best friend influence [friend partner path b: interpersonal association from fall (Time 1) top-ranked best friend adjustment outcome score to winter (Time 2) target participant’s score on the same variable]. The top-ranked best friend influence path describes the extent to which participants changed their adjustment outcome behavior from Time 1 to Time 2 to resemble (conform to) that of the top-ranked best friend at Time 1.

Model 3 depicts the influence of status-based norms (see Supplemental Figure 1). The model included the estimate of individual stability (actor path a) and the estimate of status-based norm influence [group partner path c: interpersonal association from fall (Time 1) status-based norm adjustment outcome score to winter (Time 2) target participant’s score on the same variable]. The status-based norm influence path describes the extent to which a participant changed their adjustment outcome behavior from Time 1 to Time 2 to resemble (conform to) status-based norms at Time 1.

Model 4 depicts the final GAPIM (see Figure 1). The model included estimates of individual stability (actor path a), top-ranked best friend influence (friend partner path b), and status-based norm influence (group partner path c). The model partitions unique influence between top-ranked best friends and status-based norms, describing the relative strength of each after removing overlapping variance.

Figure 1. Sources of peer influence analytic model: group actor partner interdependence model (GAPIM) describing longitudinal associations from top-ranked best friend and status-based norm to changes in socioemotional adjustment.

Note. Separate analyses were conducted for each socioemotional adjustment variable (in parentheses). Actor path a = individual stability/actor path. Friend partner path b = top-ranked best friend influence path. Group partner path c = peer group status-based norm influence path. Concurrent correlations were included in the model but are not depicted.

Follow-up analyses were conducted on Model 4 to identify age-group differences in top-ranked best friend and status-based norm influence. Wald tests of parameter constraints compared older participants (7th–8th grade) and younger participants (5th–6th grade) on the magnitude of top-ranked best friend influence (friend partner path b) and on the magnitude of status-based norm influence (group partner path c).

Standard goodness of fit indices assessed model fit. The RMSEA should be < .08 and the CFI and TLI should be > .95 (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). To assess fit in an otherwise fully saturated model, class participation rate was included as a fall (Time 1) covariate [i.e., correlated with all fall (Time 1) predictors]. Fit was adequate for each model (RMSEA < .01–.03, CFI = .98–.99, TLI = .95–.99).

Supplemental analyses

Four sets of supplemental analyses included (as covariates) variables known to correlate with peer influence, to isolate the influence effects of top-ranked best friends and status-based norms. In separate analyses, each fall (Time 1) predictor variable was correlated with concurrent participant scores on: (a) total number of outgoing friend nominations; (b) acceptance; (c) rejection; and (d) unpopularity.

Power analyses

Monte Carlo simulations (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2002) with 1,000 replications were conducted to determine whether there was adequate (80%) power to detect statistically significant small (β = 0.1), medium (β = 0.3), and large (β = 0.5) effects for each longitudinal path in Model 4, as well as for age-group contrasts on each path. There was sufficient power to detect large and medium effects for top-ranked best friend and status-based norm influence (M > .99, range = .99–.99), but less power to detect small effects (M = .73, range = .64–.78). For multiple group contrasts, there was sufficient power to detect large and medium effect age-group differences (M > .99, range = .99–.99), but less power to detect small effect age-group differences (M = .59; range = .40–.69) in top-ranked best friend influence and status-based norm influence.

Results

Preliminary results

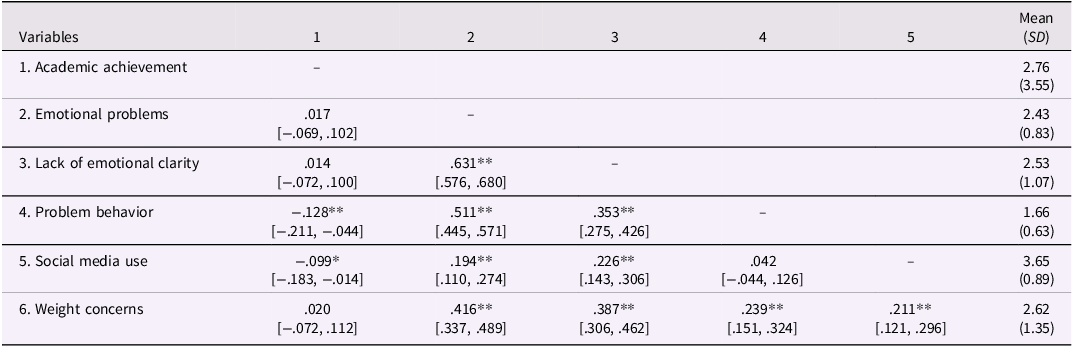

Table 1 presents interclass correlations between study variables in the fall (Time 1). Academic achievement was statistically significantly (p < .05) associated with popularity, problem behavior, and social media use. Emotional problems and lack of emotional clarity were positively correlated with each other and with problem behavior, social media use, and weight concerns. Popularity and weight concerns were positively correlated with social media use.

Table 1. Fall (Time 1) interclass correlations, means, and standard deviations: individual scores

Note. N = 543. 95% confidence intervals are presented in brackets. Emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, problem behavior, social media use, and weight concerns were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Never like me) to 5 (Always like me). Academic achievement was measured with peer nominations, standardized using a regression-based procedure that adjusts for class size.

*p < .05, **p < .01, two-tailed.

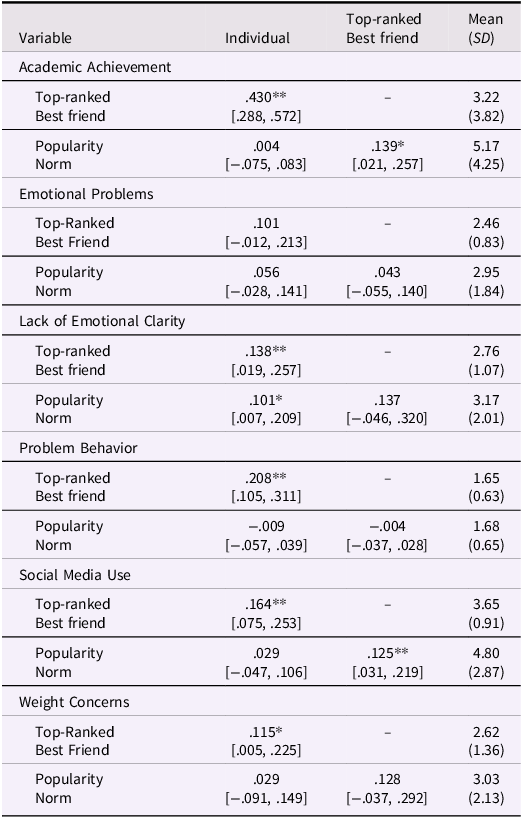

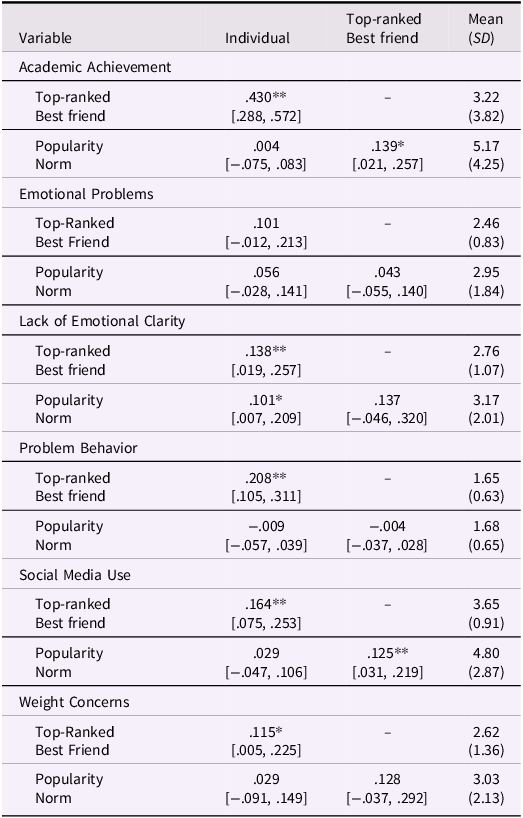

Table 2 presents the correlations between individual scores, top-ranked best friend scores, and status-based norms in the fall (Time 1). There were statistically significant positive correlations between individual and top-ranked best friend scores for academic achievement, emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, social media use, and weight concerns. There were positive correlations between individual scores and status-based norms on lack of emotional clarity. There were also positive correlations between top-ranked best friend scores and status-based norms on academic achievement, lack of emotional clarity, social media use, and weight concerns.

Table 2. Fall (Time 1) interclass correlations: individual scores, top-ranked best friend scores, and status-based norms

Note. N = 543. 95% confidence intervals presented in brackets. Emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, problem behavior, social media use, and weight concerns were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Never like me) to 5 (Always like me). Academic achievement was measured with peer nominations, standardized using a regression-based procedure that adjusts for class size. Status-based norms represent the average of the fall (Time 1) scores of all students (participants and nonparticipants) in the classroom (except the participant).

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Separate repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted with academic achievement, emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, problem behavior, social media use, and weight concerns as dependent variables. Age-group (younger = 5th–6th grade, older = 7th–8th grade) was the between-subjects variable. Time (fall and winter) was the repeated measure. There was a main effect of age-group for lack of emotional clarity, F(1, 514) = 11.05, p < .001. Older adolescents reported greater lack of emotional clarity than younger adolescents (d = 0.27). There was also a main effect of time for weight concerns, F(1, 514) = 6.42, p = .012. Weight concerns increased from the fall (Time 1) to the winter (Time 2) (d = 0.12). Finally, there was a time × age-group interaction for emotional problems, F(1, 514) = 5.26, p = .020. Increases in emotional problems were greater for older adolescents (d = 0.10) than younger adolescents (d = 0.08). The full list of results can be found in Supplemental Table 1.

GAPIM analyses describing behavioral domain differences in sources of peer influence

The GAPIM analyses followed a four-step procedure. Supplemental Table 2 describes the results of Models 1, 2, and 3.

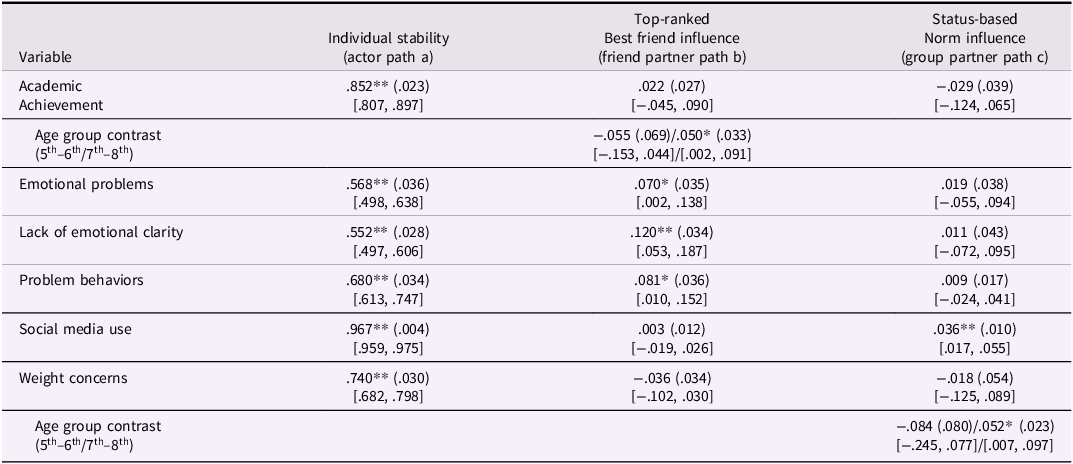

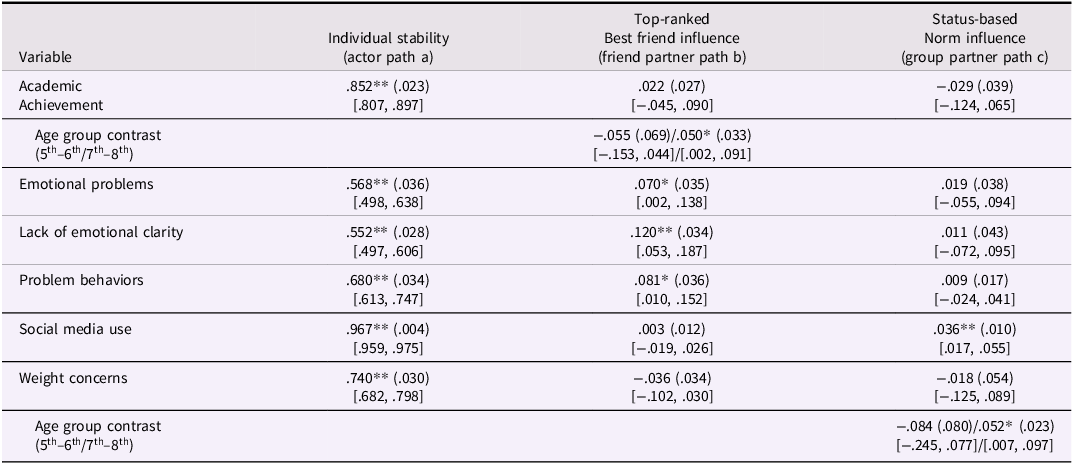

Table 3 presents the results from Model 4. The same pattern of statistically significant (p < .05) results emerged in Model 4 as in Models 1–3.

Table 3. Top-ranked best friend and status-based norm influence over socioemotional adjustment: results from the final GAPIM

Note. N = 543. Standardized beta weights presented with standard error presented in parentheses and 95% confidence intervals in brackets. Figure 1 depicts the path labels. Results from statistically significant (p < .05) multiple group age-group contrasts presented below direct effects, with younger adolescents (5th–6th grade) to the left of the slash and older adolescents (7th–8th grade) to the right of the slash; standard errors presented in parentheses.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Academic achievement

Fall (Time 1) top-ranked best friends (friend partner path b) and status-based norms (group partner path c) were not associated with changes in individual academic achievement from fall (Time 1) to winter (Time 2). However, there were statistically significant age-group differences for top-ranked best friend influence, W(1) = 5.66, p = .02. Top-ranked best friends influenced the academic achievement of older students (β = .05, p = .04) but not younger students (β = −.06, p = .28). There were no statistically significant age-group differences on status-based norm influence, W(1) = 2.41, p = .12.

Emotional problems

Top-ranked best friends influenced individual emotional problems (friend partner path b). Higher fall (Time 1) friend emotional problems anticipated greater increases in individual emotional problems from fall (Time 1) to winter (Time 2). Fall (Time 1) status-based norms were not associated with changes in individual emotional problems (group partner path c). There were no statistically significant age-group differences on top-ranked best friend influence, W(1) = 2.57, p = .11, or on status-based norm influence, W(1) = .02, p = .88.

Lack of emotional clarity

Top-ranked best friends influenced individual lack of emotional clarity (friend partner path b). Higher fall (Time 1) friend lack of emotional clarity anticipated greater increases in individual lack of emotional clarity from fall (Time 1) to winter (Time 2). Fall (Time 1) status-based norms were not associated with changes in individual lack of emotional clarity (group partner path c). There were no statistically significant age-group differences on top-ranked best friend influence, W(1) = .05, p = .83, or on status-based norm influence, W(1) = 3.01, p = .08.

Problem behaviors

Top-ranked best friends influenced individual problem behaviors (friend partner path b). Higher fall (Time 1) friend problem behaviors anticipated greater increases in individual problem behaviors from fall (Time 1) to winter (Time 2). Fall (Time 1) status-based norms were not associated with changes in individual problem behaviors (group partner path c). There were no statistically significant age-group differences on top-ranked best friend influence, W(1) = .04, p = .84, or on status-based norm influence, W(1) = .01, p = .93.

Social media use

Popularity norms influenced individual social media use (group partner path c). Higher fall (Time 1) status-based norms for social media use anticipated greater increases in individual social media use from fall (Time 1) to winter (Time 2). Fall (Time 1) top-ranked best friends were not associated with changes in individual social media use (friend partner path b). There were no statistically significant age-group differences on top-ranked best friend influence, W(1) = .50, p = .48, or on status-based norm influence, W(1) = .05, p = .82.

Weight concerns

Fall (Time 1) top-ranked best friends (friend partner path b) and status-based norms (group partner path c) were not associated with changes in individual weight concerns from fall (Time 1) to winter (Time 2). However, there were statistically significant age-group differences for status-based norm influence, W(1) = 5.32, p = .02. Status-based norms influenced the weight concerns of older students (β = .05, p = .02), but not younger students (β = −.08, p = .29). There were no statistically significant age-group differences on top-ranked best friend influence, W(1) = .02, p = .88.

Supplemental analyses

Supplemental analyses were conducted to remove variance associated with confounding variables in order to isolate influence attributed to top-ranked friends and status-based norms. Separate GAPIM analyses included one of four potentially confounding variables as covariates: (a) acceptance; (b) total number of outgoing friend nominations; (c) rejection; and (d) unpopularity. Supplemental Tables 3–6 indicate that the same pattern of statistically significant results emerged in each case.

Discussion

The present study is unique in that it is the first to test the hypothesis that different peers exert different amounts of influence over different forms of behavior. As expected, conformity to best friends and to popularity-driven (i.e., peer status-based) classroom norms varied across behaviors. When both were included in the same model (removing shared effects), best friends were particularly influential over behaviors that reflect dysfunction and maladjustment (i.e., emotional problems, lack of emotional clarity, problem behaviors, and – among older adolescents – academic difficulties), whereas status-based group norms were particularly influential over behaviors that reflect impression management and appearance (i.e., social media use and – among older adolescents – weight concerns). Notably, the findings held after controlling for other peer status variables and friend network size, isolating effects to best friends and status-based norms.

As we discuss the findings and their implications below, it is important to bear in mind that our analyses represent the first-ever attempt to simultaneously assess friend influence and peer-group norm influence. The strategy we adopted describes the unique influence of best friends, over and above that of status-based norms, and the unique influence of status-based norms, over and above that of best friends. Although the correlations between the two sources of influence were modest (never exceeding 2% of the variance), they were often statistically significant. Removing overlapping variance reduced the magnitude of influence attributed to both sources, potentially enough to render as nonsignificant, effects that others have reported as significant when examining sources of influence in isolation. The point is not that joint influence is unimportant, but that it is different, and should not be ascribed to a single source. Joint influence effects can and should be assessed with analytic tools designed for the challenge, such as the common fate model (Ledermann & Kenny, Reference Ledermann and Kenny2012), which has not, to our knowledge, been applied to longitudinal peer data.

Drawing from evolutionary theory, we applied the Algorithms of Social Life (Bugental, Reference Bugental2000) model to peer influence. According to the model, mental algorithms evolved to help humans master the social demands of living with others – equipping them with adaptive strategies for getting along. We focused on the two social algorithms most relevant to contemporary youth as they navigate a shifting social world characterized by dramatic increases in the salience and amount of unsupervised time with peers. The reciprocity algorithm is designed to guide behavior within egalitarian relationships, such as those between friends. The hierarchy algorithm is designed to guide behavior in power imbalanced relationships, such as those in popularity-dominated peer groups. The application of these algorithms leads to the important insight that peer influence is not a monolithic, undifferentiated process. The framework serves as a starting point for explanations that address why peer influence varies across social settings and behaviors. But it is far from complete. The model does not specify which relationships and which algorithms dominate which forms of behavior. We can only offer post hoc interpretations of the differences we observed. Similarly, it is not clear what happens when both social algorithms come into play, such as when best friends interact with one another while embedded in a peer group. We suspect in these circumstances, youth conform to group norms unless doing so creates conflict with a friend. We eagerly await new conceptual and empirical work that fleshes out the applications of social algorithms to contemporary peer relationships.

A common theme emerged in the findings for friends, one that ties adjustment challenges to the reciprocity algorithm. Interactions with friends are uniquely important during the transition into adolescence, providing a supportive, private space to exchange and explore emotions and goals. The consequences are not always adaptive. Like others, we found evidence for friend influence over internalizing symptoms (Giletta et al., Reference Giletta, Scholte, Burk, Engels, Larsen, Prinstein and Ciairano2011), externalizing symptoms (e.g., Shin & Ryan, Reference Shin and Ryan2017), and academic achievement (e.g., Shin & Ryan, Reference Shin and Ryan2014). New to our study is the determination that effects are specific to best friends and are not driven by conformity (on the part of one or both friends) to popularity-driven peer group norms. Friend influence manifests itself through different means. Co-rumination, a process of self-disclosure that fosters closeness (Rose, Reference Rose2002), reinforces negative thinking in ways that promote the spread of anxiety between friends (Dirghangi et al., Reference Dirghangi, Kahn, Laursen, Brendgen, Vitaro, Dionne and Boivin2015). Problem behaviors also spread between friends through interactions that reward deviant talk and conduct (Dishion et al., Reference Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews and Patterson1996). Rejected by peers because of conduct problems, troubled friends support and reinforce the very behaviors that isolate them from others (Vitaro et al., Reference Vitaro, Pedersen and Brendgen2007). Finally, many friendships are centered on a common academic identity. Those who prioritize achievement share educational values; similarity grows as partners assist one another on assignments and work together on school projects (DeLay et al., Reference DeLay, Laursen, Kiuru, Poikkeus, Aunola and Nurmi2015). Others forge an oppositional identity organized around the rejection of school culture and achievement (Eckert, Reference Eckert1989). School failure can bring friends closer together, particularly if they are segregated into special classrooms or self-segregate to avoid censure from their achievement-oriented peers (Flashman, Reference Flashman2012). A form of deviant talk ensues, where friends reinforce depictions of failure (Berndt & Keefe, Reference Berndt, Keefe and Brophy1996). Others have also reported age differences in friend influence over school achievement (Leclerc-Bedard et al., Reference Leclerc-Bedard, Kaniušonytė and Laursen2025), so it is perhaps not surprising that they emerged because academic achievement becomes more salient and more clearly tied to long-term goals in middle school than during primary school (Gremmen et al., Reference Gremmen, Dijkstra, Steglich and Veenstra2017).

Fewer behaviors were influenced by status-based peer norms, but those that emerged had clear ties to the hierarchy algorithm. Appearance plays out on a public stage. Appearance-related expectations are driven from the top of the hierarchy. Popular youth establish standards for attractiveness, modeling and reinforcing fashion and weight expectations, in school, out of school, and, presumably, online (Salvy & Bowker, Reference Salvy and Bowker2017). Peer-perceived attractiveness, in turn, contributes to and maintains status (e.g., Leggett-James et al., Reference Leggett-James, Faur, Kaniušonytė, Žukauskienė and Laursen2023). Deviation from norms can be costly. Fat-talk and weight-related bullying grow during middle school (Juvonen et al., Reference Juvonen, Lessard, Schacter and Suchilt2017). We are not the first to report that norms drive weight concerns (e.g., Juvonen et al., Reference Juvonen, Lessard, Schacter and Enders2018), but our study is novel in its determination that the effects are specific to status-based norms and are not driven by conformity to higher status friends. Although we did not hypothesize age differences, the fact that weight-related popularity norms were particularly strong during early adolescence should not come as a surprise. Concerns about and dissatisfaction with weight and appearance rapidly escalate at the onset of puberty (Voelker et al., Reference Voelker, Reel and Greenleaf2015). Unique to our study are findings that address peer influence over social media use. Here too, behaviors were driven by high-status peers and not best friends. Social media is assumed to be a tool for status management (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Zhang, Troop-Gordon, Taylor and Chung2025), where users model expected behavior and enforce norms through access, likes, and comments. Some have postulated that youth use social media strategically to enhance their visibility, curating posts in ways that underscore conformity to group norms (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b). We note, in passing, the absence of age group differences, suggesting that norms shape social media use among preteens, who technically are not supposed to have unrestricted access to it.

More broadly, our work underscores the central role of peers in developmental psychopathology. Our findings do not speak directly to whether peers cause clinical levels of dysfunction, but they make clear that the peer context cannot be overlooked for the emergence and persistence of problem behaviors. Previous attempts to trace the origins of symptoms may have overlooked this by focusing on the wrong source of influence. Peer influence is too global a construct. The effects of best friends and of popular peers are distinct, and understanding their impact requires precise theorizing and measurement within the domains where each is most consequential.

Some may be unfamiliar with Lithuania and hesitant to generalize from this sample. A small Northern European nation adjacent to Poland and across the Baltic Sea from Sweden, Lithuania has been a member of NATO and the European Union for more than 20 years. Liberation from the Soviet Union and three decades of freedom and prosperity brought innumerable changes to schools and peer culture. Lithuanian youth are similar to those in other Western European nations in terms of norms and values (Kaniušonytė & Žukauskienė, Reference Kaniušonytė and Žukauskienė2018). Like their Northern European counterparts, young adolescents in Lithuania enjoy considerable freedom of movement (Žukauskienė, Reference Žukauskienė and Žukauskienė2016), and like their Eastern European counterparts, the parents of Lithuanian children prefer traditional parenting practices (Maslauskaitė & Steinbach, Reference Maslauskaitė, Steinbach, Kreyenfeld and Trappe2020). Numerous studies from this data set have failed to identify meaningful differences between US students and Lithuanian students in peer status, adjustment outcomes, classroom norms, and associations between them (Katulis et al., Reference Katulis, Kaniušonytė and Laursen2025; Leggett-James et al., Reference Leggett-James, Faur, Kaniušonytė, Žukauskienė and Laursen2023), bolstering confidence in the generalizability of our conclusions.

The findings have important practical implications. Specifically, the knowledge that different peers shape different forms of maladjustment has the potential to shape prevention and intervention strategies. Efforts to change classroom norms in response to behavior problems may be of little consequence in algorithms that are dominated by friend influence. We know that classroom seating changes anticipate the development of new friendships (Faur & Laursen, Reference Faur and Laursen2022), offering a subtle tool for teachers to pair vulnerable youth with less vulnerable peers. Further, new friends with positive traits may sway children to behave differently, provided the friends have some sort of common ground on which to build their relationship (Gremmen et al., Reference Gremmen, Dijkstra, Steglich and Veenstra2017). Intervening directly against maladaptive friendships may be effective in disrupting the affiliation, but over the long-term problem behaviors tend to increase, not decrease, in response to parent friend disapproval (Kaniušonytė & Laursen, Reference Kaniušonytė and Laursen2024). Maintaining positive relations with children is probably a more effective strategy, buffering against the negative outcomes of increasing internalizing symptoms (e.g., Hazel et al., Reference Hazel, Oppenheimer, Technow, Young and Hankin2014). By the same token, efforts to alter the impact of friends over public-facing behaviors such as social media use and appearance may be of little consequence in algorithms that are dominated by peer group norms. Intervention studies have demonstrated that alterations to status-based norms can influence behaviors such as aggression and prosocial behavior (Paluck et al., Reference Paluck, Shepherd and Aronow2016). Conversely, ignoring status-based norms can perpetuate maladaptive behaviors. For example, bullying and substance may become normalized within certain peer groups (Veenstra, Reference Veenstra2025). Many schools have policies on social media practices. Although initial evidence suggests that social media use policies may mitigate the negative effects of social media use – particularly cyberbullying – on vulnerable youth, policy efficacy is limited (Thimm-Kaiser & Keyes, Reference Thimm-Kaiser and Keyes2025). Indeed, rules are difficult to enforce, and many youth find ways to circumvent them. Intervention efforts designed to shape norms benefit from recruiting popular peers to the cause (Paluck et al., Reference Paluck, Shepherd and Aronow2016); social media policies may reap the same reward. Appearance norms, which originate from popular peers but also probably social media influencers, may require similar strategies. Programs should focus on enlisting popular peers to adopt transparency around social media filters and edited photos. Disclosing the use filters and edits, popular peers may encourage greater tolerance for realistic appearance standards and may mitigate negative outcomes.

Our study is not without limitations. First, although the number of classrooms (29) was adequate for GAPIM analyses (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Lüdtke, Nagengast, Trautwein, Morin, Abduljabbar and Köller2012), null findings should be interpreted with caution because they encompassed effects too small to be identified with underpowered analyses. Second, participants were drawn from a small, homogenous community in Northern Europe. Future studies must determine the extent to which the findings generalize to youth living in heterogeneous, urban contexts and to those in non-Western settings. Relatedly, we used instruments originally devised for English-speaking participants. Although all of the variables – with the exception of social media use – have been used in a non-English speaking contexts (Asgarizadeh et al., Reference Asgarizadeh, Mazidi, Preece and Dehghani2024; Manicinelli et al., Reference Manicinelli, Cottu and Salcuni2024) and emotional problems and conduct problems have been used in other studies with no demonstrable differences this Lithuanian sample and a parallel US sample, strict measurement invariance has not been demonstrated for the variables applied herein. Third, the results do not capture systematic unobserved variations in classroom-specific associations. Such concerns are mitigated, but not eliminated, by the application of the COMPLEX function in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017), which accounts for classroom nesting. Nevertheless, assumptions that the findings generalize across different classroom contexts must be tempered. Best friends differ too, in connectedness and cooperation (e.g., Shulman & Laursen, Reference Shulman and Laursen2002), dimensions that would seemingly impact the amount of influence they exert over one another. Finally, we note the distinction between status-based norm influence and popular peer influence. Although both reflect aspects of the hierarchy algorithm, popular peers are few in number, whereas norms capture a collective consensus, weighted by popularity. A focus on popular peers raises definitional questions that can be avoided with popularity-driven norms, but assumptions that the two constructs hold similar sway awaits empirical confirmation.

Best friends and status-based norms exert differing levels of influence over different adolescent behaviors. Although perhaps self-evident, this insight has the potential to profoundly reshape conventional views of and research approaches toward conformity and peer pressure. When considered jointly, best friends emerged as important sources of influence over behaviors that signaled problems, academically and behaviorally, whereas peer group norms emerged as important sources of influence over behaviors that reflect concerns with impression management and appearance. The knowledge that sources of peer influence overlap and that friends and popular peers uniquely shape different outcomes should open the door to a new generation of research. The nuanced insights offered here about distinct sources of influence have the potential to upend long-held assumptions about the role of peers in the development of adjustment difficulties.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579426101138.

Data availability statement

The data sets are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance and cooperation of the students, faculty, and staff at the Utena District Schools in Lithuania.

Funding statement

The data collection for this project was supported by the European Social Fund (project No 09.3.3-LMT-K-712-17-0009) under grant agreement with the Research Council of Lithuania. The manuscript was prepared as part of a project funded by the State Budget titled Establishment of Centers of Excellence at Mykolas Romeris University, which is implemented under the initiative Centers of Excellence Initiative initiated by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports of the Republic of Lithuania.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Pre-registration

This study was not pre-registered.

AI statement

No AI was used in the preparation of this article.