Policy Significance Statement

This study on the existence of formalized urban data governance in the case of a sample of German small towns and all German rural districts will inform the current discourse on digitalization and data-based approaches in smaller municipal administrations. It will serve as a foundation for policy and funding program assessment and for further comparative research in this field.

1. Introduction

The importance of data for sustainable urban development has been acknowledged for several years. Municipalities can optimize urban management with real-time data and better implement evidence-based urban planning and development (Engin et al., Reference Engin, van Dijk, Lan, Longley, Treleaven, Batty and Penn2020; Hersperger et al., Reference Hersperger, Thurnheer-Wittenwiler, Tobias, Folvig and Fertner2022; Sabri and Witte, Reference Sabri and Witte2023; Townsend, Reference Townsend2015). Urban data, whether generated and held by public institutions or by private firms or civil society, comprise historical time series as well as real-time data, in many cases with spatial attributes, and can be aggregated into “big data” sets (Giest, Reference Giest2017; Mans et al., Reference Mans, Giest, Baar, Elmqvist, Bai, Frantzeskaki, Griffith, Maddox, McPhearson, Parnell, Romero-Lankao, Simon and Watkins2018; Kandt and Batty, Reference Kandt and Batty2021). They can be integrated, for instance, into digital urban twins as platforms that allow for more sophisticated analysis and simulation (Batty, Reference Batty2024).

The amount of urban data gathered, administered, and generated by cities is continuously increasing. However, handling these data does not only require appropriate technical capacity but also critical reflection on its political and ethical dimensions, including questions of power (Söderström and Datta, Reference Söderström and Datta2024) and its interlinkage with innovation of urban development and policy for the common good (Duarte and Álvarez, Reference Duarte and Álvarez2019). While the use of data in larger cities, often linked to smart city initiatives, has been intensively studied over the last few decades (e.g., Barns, Reference Barns2018; Engin et al., Reference Engin, van Dijk, Lan, Longley, Treleaven, Batty and Penn2020; Paskaleva et al., Reference Paskaleva, Evans, Martin, Linjordet, Yang and Karvonen2017), the municipal engagement with data for urban development beyond large metropolises has only recently gained increased attention in local administrative practice and academic discourse (cf., e.g., Damm and Spellerberg, Reference Damm and Spellerberg2021; Dembski et al., Reference Dembski, Wössner, Letzgus, Ruddat and Yamu2020; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Frank, Fridgen and Heger2018; Ruohomaa et al., Reference Ruohomaa, Salminen and Kunttu2019; Soike and Libbe, Reference Soike and Libbe2018; Spicer et al., Reference Spicer, Goodman and Olmstead2021).

Across varying national contexts—and political framings of data (Kitchin, Reference Kitchin, Söderström and Datta2023)—such as Canada (Zwick et al., Reference Zwick, Spicer and Bezdedeanu2025), Switzerland (Fabrègue, Reference Fabrègue2025), Great Britain (Thuermer et al., Reference Thuermer, Walker, Koutsiana, Simperl, Carr and Schachtner2025), and the Netherlands (Zuiderwijk et al., Reference Zuiderwijk, Volten, Kroesen and Gill2018), studies reveal a persistent gap in data policy, politics, and practice between large city administrations and smaller municipalities. Examining the conditions under which small towns generate, use, and govern data is therefore crucial for local data-informed and evidence-based urban management (Engin et al., Reference Engin, van Dijk, Lan, Longley, Treleaven, Batty and Penn2020) and on a broader scale for strengthening trust in the evidence that informs policy (cf. Kitchin, Reference Kitchin2025). Moreover, systematic urban data governance (UDG) reflects a thoughtful approach to knowledge production, one that also carries a geopolitical dimension at the global level (Robin and Acuto, Reference Robin and Acuto2018). The European Union (EU) has highlighted the strategic importance of data governance (DG) in recent legal frameworks (EC, 2020a). Given that a higher share of the European population lives in small and medium-sized towns than in large cities (Terfrüchte and Growe, Reference Terfrüchte and Growe2024, p. 18), the adoption of data-related policies by these smaller municipalities is central to realizing European DG frameworks on the local level (cf. Stratigea et al., Reference Stratigea, Leka, Nicolaides, Stratigea, Kyriakides and Nicolaides2017, p. 9).

Within this broader context, the case of Germany represents a prototypical instance to examine the state of UDG in small towns. In Germany, 29% of the German population lives in small towns (Milbert, Reference Milbert2022, p. 4), and its multilevel federal system with high municipal autonomy (Marienfeldt et al., Reference Marienfeldt, Kühler, Kuhlmann and Proeller2024, p. 43) adds complexity to policy adoption in a domain that favors interoperability and unified standards. Recent studies reveal substantial regional variance in how local German administrations frame specific topics (Schütz et al., Reference Schütz, Kriesch and Losacker2025) and implementation gaps in data-based concepts like digital twins in German local administrations (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Campbell and Riedl2025). These disparities highlight the challenges of establishing a coherent UDG across Germany’s fragmented administrative landscape.

So far, formalized UDG, considered a precondition to “good” municipal data practice by academics and in German policy guidelines (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023; Fuhrmann et al., Reference Fuhrmann, Böttcher and Bimesdörfer2021; Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023), has been implemented only recently and sparsely by German municipal administrations, mostly as part of more general digital strategies in the context of smart-city initiatives (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann and Pervez2022; Bürger et al., Reference Bürger, Wiedemann and Raffer2022; Bayat and Kawalek, Reference Bayat and Kawalek2023; Difu, n.d.; Fuhrmann et al., Reference Fuhrmann, Böttcher and Bimesdörfer2021). Several large German cities have recently implemented data guidelines or plan to do so (e.g., Berlin, 2023, pp. 9–10; Hamburg, 2020, p. 32; Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023; Schmuck, Reference Schmuck2024). Although systematic UDG is indispensable for efficient municipal data practice, also in small towns (Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023, p. 4), it is yet unclear whether smaller municipal administrations have UDG strategies or respective guidelines following the explicitly stated goal to foster data-based sustainable urban development (EC, 2020b, p. 5). While recent research has reviewed the extant literature and the status quo of UDG in larger German cities (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann and Pervez2022; Schmuck, Reference Schmuck2024), a mapping of UDG in German small towns and rural districts seems to be missing. As an instance of the broader phenomenon, a nuanced overview of UDG in smaller municipalities and rural districts in the German case is not only relevant for policymakers to assess dissemination and efficiency of policies and funding programs (cf. Zabel and Kwon, Reference Zabel and Kwon2021), but also provides the basis for further research on local digital governance (cf. Barns, Reference Barns2023; Bou Nassar et al., Reference Bou Nassar, Sharp, Anwar, Bartram and Goodwin2024 Lekkas and Souitaris, Reference Lekkas and Souitaris2023; Mora et al., Reference Mora, Gerli, Ardito and Messeni Petruzzelli2023). To this end, we aimed at addressing the small-town knowledge gap by conducting systematic online research of relevant municipal strategies and concepts for a sample of small towns and all rural districts (Landkreise) in Germany. We then performed content analysis of the identified documents, guided by the following three research questions (RQs):

-

(1) How common are published data strategy documents or DG-related guidelines as an expression of a formalized DG strategy in German small towns and rural districts?

-

(2) To what extent does the existence of a data strategy or DG-related guidelines correlate with (a) the respective federal state, (b) the degree of rurality of the district, (c) the socioeconomic situation of the respective district, and on a small town level, (d) the size of the small towns?

-

(3) Is urban development addressed in the existing documents, and if so, which dimensions are addressed?

2. Theoretical background and current discourse

2.1. UDG and data strategies

While DG was originally introduced in corporate and technical contexts (Al-Ruithe et al., Reference Al-Ruithe, Benkhelifa and Hameed2019; Jagals et al., Reference Jagals, Karger and Ahlemann2019; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2017), the more recent adaptation of UDG in the context of the “smart city” discourse relates to activities, stakeholders, and ecosystems in urban settings, aiming at supporting urban development (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann and Pervez2022; Choenni et al., Reference Choenni, Bargh, Busker and Netten2022; König, Reference König2021; Paskaleva et al., Reference Paskaleva, Evans, Martin, Linjordet, Yang and Karvonen2017). While definitions vary across disciplines (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Schneider and vom Brocke2019; Al-Ruithe et al., Reference Al-Ruithe, Benkhelifa and Hameed2019; Bližnák et al., Reference Bližnák, Munk and Pilková2024, p. 149886; U. G. Gupta and Cannon, Reference Gupta and Cannon2020, p. 33), a “social science-informed definition” (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Ponti, Craglia and Berti Suman2020, p. 2) of UDG seems valid, “… understand[ing] data governance as the power relations between all the actors affected by, or having an effect on, the way data is accessed, controlled, shared and used, the various socio-technical arrangements set in place to generate value from data, and how such value is redistributed between actors …” (Micheli et al., Reference Micheli, Ponti, Craglia and Berti Suman2020, p. 3).

The definition of the interplay of data strategies, data policy, and DG by Lis et al. (Reference Lis, Gelhaar, Otto, Caballero and Piattini2023) for a corporate domain can be adopted for urban contexts where a “[data] strategy defines required capabilities for its successful execution [, its operationalization] is anchored through [data] policies” (Lis et al., Reference Lis, Gelhaar, Otto, Caballero and Piattini2023, p. 28) and results in a DG which “… defines standards …” (Lis et al., Reference Lis, Gelhaar, Otto, Caballero and Piattini2023, p. 28). Bozkurt et al. (Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023) highlight that “[data] governance exists in every organization but may not be formalized [.] … [Formal] data governance comprises established guidelines, practices, and clear roles and responsibilities …” (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023, p. 85658).

In recent years, government strategies and legislative frameworks for DG have been implemented across different levels of government. The European strategy for data (EC, 2020a) builds on the concept of data spaces (Cuno et al., Reference Cuno, Bruns, Tcholtchev, Lämmel and Schieferdecker2019; Schieferdecker, Reference Schieferdecker, Putnings, Neuroth and Neumann2021; Battistoni, Reference Battistoni, Bevilacqua, Balland, Kakderi and Provenzano2023) to establish common European data spaces (Weber, Reference Weber2023; EC, 2024a). DG-related goals of the European strategy for data (EC, 2020a) are translated into the European Data Governance Act (EP and EU Council, 2022) and the Data Act (EP and EU Council, 2023; EC, 2024b; EC, 2024c). With regard to the case of Germany, the Data Strategy of the Federal German Government sets the agenda for “… innovative and responsible data …” and intends to push for harmonization of state-level data laws (Bundesregierung and Bundeskanzleramt, 2021, p. 64). German states, too, have developed DG guidelines as data strategies (Schleswig-Holstein, 2024), open data strategies (Berlin, 2023; Brandenburg, 2023), or calls for federal cooperation (cf. Baden-Württemberg, 2020).

Additional laws regulate municipal data use (Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023, pp. 10–11), including the GDPR (EP and EU Council, 2016), the law on re-use of public sector information (EP and EU Council, 2019; DNG, 2021), and domain-specific regulations, e.g., for geodata (INSPIRE, EP and EU Council, 2007; GeoZG, 2009). Sapienza et al. (Reference Sapienza, Palmirani, Greco, Kö, Kotsis, Tjoa and Khalil2024) discuss the European frameworks in the context of smart cities.

2.2. Municipal data strategies for UDG

Given the importance and possible contribution of UDG for common welfare in municipalities, both the EU and the German federal government promote formalization of DG practices on a regional and local level (EC, 2020b; Fuhrmann et al., Reference Fuhrmann, Böttcher and Bimesdörfer2021; Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023). However, until today, there has been no established regulation for systematic and structured governance of data in municipal administrations in Germany (Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023, p. 7). Key aspects of UDG are nevertheless increasingly part of international (Micozzi and Yigitcanlar, Reference Micozzi and Yigitcanlar2022) as well as German smart city strategies (Schmuck, Reference Schmuck2024). A new combined form of digitalization strategies (including partly DG aspects) and integrated urban development strategies is suggested and implemented with the integrated digital development concepts (German: Integriertes Digitales Entwicklungskonzept [IDEK]; Wittpahl and Sedlmayr, Reference Wittpahl and Sedlmayr2023) in several Bavarian piloting municipalities (e.g., Landeshauptstadt München, n.d.; Spinrath and Plessing, Reference Spinrath and Plessing2023, p. 21).

Though comprehensive research on UDG effects on small towns is lacking, existing studies indicate UDG positively influences local data practices in small municipalities, also by enhancing data literacy (Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023) and fostering open data publication (Rajamäe Soosaar and Nikiforova, Reference Rajamäe Soosaar and Nikiforova2025, p. 12). Implementing UDG also aligns with efforts to reduce the digital divide between larger cities and smaller municipalities (cf. Feurich et al., Reference Feurich, Kourilova, Pelucha and Kasabov2024; Löfving et al., Reference Löfving, Kamuf, Heleniak, Weck and Norlén2022).

Implementation challenges of UDG range from establishing a municipal data culture (Courmont, Reference Courmont2021) and building up data ecosystems (Liva et al., Reference Liva, Micheli, Schade, Kotsev, Gori and Codagnone2023) through acquisition of digital skills and data literacy (Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023) to providing sufficient financial resources for relevant infrastructure (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, von Radecki and Ottendörfer2020, p. 19; Dembski et al., Reference Dembski, Wössner, Letzgus, Ruddat and Yamu2020, p. 3). Several contributions suggest concepts and frameworks to address shortcomings (Choenni et al., Reference Choenni, Bargh, Busker and Netten2022; Cuno et al., Reference Cuno, Bruns, Tcholtchev, Lämmel and Schieferdecker2019; de Macedo Schäfer et al., Reference de Macedo Schäfer, Schweinberg, Stenzel and Grafenstein2023; A. Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Panagiotopoulos and Bowen2020; Lupi, Reference Lupi2019; Paskaleva et al., Reference Paskaleva, Evans, Martin, Linjordet, Yang and Karvonen2017; Schieferdecker, Reference Schieferdecker, Putnings, Neuroth and Neumann2021). Mapping the notion of UDG in cities of six EU countries, Bozkurt et al. (Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023) intend to lay the groundwork for a UDG reference model (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023, p. 85674). Overall, the observation that “[although] the rhetoric ‘wants’ smart cities and big data together, a significant portion of data produced within cities is still underused or not used at all …” (Liva et al., Reference Liva, Micheli, Schade, Kotsev, Gori and Codagnone2023, p. 4) seems to be valid for many European cities and especially for small towns (Milbert and Fina, Reference Milbert, Fina, Steinführer, Porsche and Sondermann2021, pp. 41–44).

Drawing on the reflections about the interplay between DG and its underlying formalizations in the form of a data strategy, we considered in this study the existence of documents like a municipal data strategy or specific chapters of larger municipal digital or smart city strategies (Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023, p. 6; Schmuck, Reference Schmuck2024, pp. 77, 82–83) as an indicator for systematic local UDG practice (cf. Section 3.2 Structured online content research and analysis and Higi (Reference Higi2025), “01 Criteria Data Governance Documents Research.pdf”). In contrast to informal DG practice (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023, p. 85658), a data strategy can establish formal DG practice and underpin its intra- and inter-institutional legitimacy (Helder et al., Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023, p. 30). In addition to this, it allows for a concerted DG approach in municipal administrations, including measures with implications on the organizational structure of the administration concerning roles and responsibilities, as well as measures to build the required culture, expertise, and data literacy (Branderhorst and Ruijer, Reference Branderhorst and Ruijer2024, p. 17; Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023).

2.3. Digitalization in small towns, rural areas, and districts—defining the research area

While numerous well-researched digital approaches address global challenges on a local scale in large cities (Barns, Reference Barns2018; Engin et al., Reference Engin, van Dijk, Lan, Longley, Treleaven, Batty and Penn2020; Paskaleva et al., Reference Paskaleva, Evans, Martin, Linjordet, Yang and Karvonen2017), such initiatives are less prevalent in small(er) towns (cf. e.g., Damm and Spellerberg, Reference Damm and Spellerberg2021; Dembski et al., Reference Dembski, Wössner, Letzgus, Ruddat and Yamu2020; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Frank, Fridgen and Heger2018; Ruohomaa et al., Reference Ruohomaa, Salminen and Kunttu2019; Soike and Libbe, Reference Soike and Libbe2018; Spicer et al., Reference Spicer, Goodman and Olmstead2021). Distinguishing precisely small towns from rural areas (cf. Kühne and Kamlage, Reference Kühne, Kamlage, Berr, Koegst and Kühne2024) also is challenging, as they are often considered together in funding programs and hence research projects (cf., e.g., Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Frank, Fridgen and Heger2018; Viale Pereira et al., Reference Viale Pereira, Klausner, Temple, Delissen, Lampoltshammer and Priebe2023). While international definitions of small towns by population vary (Bell and Jayne, Reference Bell and Jayne2009), the German Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) defines them as urban areas with 5,000–20,000 inhabitants or with basic to medium-level central function (BBSR, n.d.).

In Germany, municipal autonomy is guaranteed by the constitution (Heinelt and Zimmermann, Reference Heinelt and Zimmermann2021, pp. 14–15). Two tiers, municipalities and rural districts (Landkreise), constitute local government outside of large cities, where districts “… represent the municipalities within them and administer a range of services and policies on behalf of these municipalities …” (Heinelt and Zimmermann, Reference Heinelt and Zimmermann2021, p. 15; cf. also Wollmann, Reference Wollmann2024a). Both local administrative levels influence digitalization policies (Wollmann, Reference Wollmann2024b) as well as urban policies (Heinelt and Zimmermann, Reference Heinelt and Zimmermann2021), and jointly perform the same tasks as large cities. Against this backdrop and recent efforts of multilevel digitalization governance (Wegrich, Reference Wegrich2021), our study focuses on (1) municipal administrations of small towns per BBSR (n.d.) definition and on (2) district administrations covering multiple towns. This also acknowledges that rural districts (Schulz, Reference Schulz2017), as well as inter-municipal cooperation, can possibly be pivotal for digitalization efforts in Germany at a regional level (Bischoff and Bode, Reference Bischoff and Bode2021) and that digitalization outside mid-sized and large towns should continue to be discussed also on a regional scale (Matern et al., Reference Matern, Schröder, Stevens, Weidner, Bisello, Vettorato, Laconte and Costa2017).

An additional level of governance is given by metropolitan regions, albeit without official administrative status. They hence represent a sometimes-disputed and nonhomogeneous organizational backdrop (Galland and Harrison, Reference Galland, Harrison, Zimmermann, Galland and Harrison2020), making them challenging to analyze comparatively. We examined formalized data governance across all 11 metropolitan regions in Germany; however, due to the complexities mentioned, we did not consider the results in depth within this article. A summary of the results at the metropolitan regional level is provided in Higi (Reference Higi2025), “02 Formalized Data Governance in all German Metropolitan Regions - Summary of Results.pdf.”

2.4. Research gap and background of RQs

While the research reviewed above underscores the need for UDG to overcome obstacles to municipal data usage and the importance of understanding UDG practices for a better theoretical reflection on urban digital innovation, the limited knowledge base regarding smaller municipal administrations reveals a persistent “theory-practice gap” (cf. Mora et al., Reference Mora, Gerli, Ardito and Messeni Petruzzelli2023, p. 16). This gap arises as digitalization frameworks and concepts developed for larger urban areas cannot be directly transferred to small towns (Anschütz et al., Reference Anschütz, Ebner and Smolnik2024). In federal governance systems such as Germany’s, this issue is even more pronounced due to the high degree of autonomy of local administrations (Marienfeldt et al., Reference Marienfeldt, Kühler, Kuhlmann and Proeller2024, p. 43). To contribute to a more robust knowledge base filling these research gaps also on a global level, our work addresses the three RQs introduced above. In the following section, we summarize the background for each of them against the backdrop of the German case.

Regarding RQ1: The call for municipal data strategies within the European and German federal frameworks seems to result in heterogeneous local DG practices and varying levels of formalization in German districts and small towns. The literature addresses UDG challenges either globally or in larger-city case studies. Recent contributions analyzed smart city strategies (including UDG) in German state capitals and cities (Schmuck, Reference Schmuck2024) and reviewed UDG literature (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann and Pervez2022). Nevertheless, a comprehensive analysis of the status quo of DG in German small towns, allowing for a more granular analysis of possible influencing factors, seems to be lacking.

Regarding RQ2: Formalized UDG in municipal administrations can be influenced by state-level legislative frameworks, such as freedom-of-information laws (Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Engewald, Herr, Dragos, Kovač and Marseille2019). Decentralization in public governance can further affect public task attribution (Ebinger and Richter, Reference Ebinger and Richter2016), while state or federal funding programs could shape UDG dissemination (cf. Zabel and Kwon, Reference Zabel and Kwon2021). Discourse on spatial injustice and the urban-rural digital divide (Löfving et al., Reference Löfving, Kamuf, Heleniak, Weck and Norlén2022; Feurich et al., Reference Feurich, Kourilova, Pelucha and Kasabov2024) reveal correlations between rurality and digitalization maturity. While digital practices are assumed to foster rural and small-town development (cf., e.g., Mariotti et al., Reference Mariotti, Capdevila and Lange2023), reality is often more complex (cf., e.g., Binder and Matern, Reference Binder and Matern2020), not least because budgets constrain the introduction of DG roles like chief digital officer or data steward. Sociodemographics and the presence of innovation-driven enterprises, research institutes, and higher education institutions can also affect local municipal digitalization (Greef and Schroeder, Reference Greef and Schroeder2021). Additionally, town size possibly also impacts data availability (Milbert and Fina, Reference Milbert, Fina, Steinführer, Porsche and Sondermann2021), data literacy (Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023), and, hence, local UDG.

Regarding RQ3: Digitalization projects are often closely linked to fields of urban development. However, besides the aforementioned integrated digital development concepts (IDEK; Wittpahl and Sedlmayr, Reference Wittpahl and Sedlmayr2023), municipal strategy papers mostly do not consider UDG and urban development strategies as closely interwoven. Content analysis on specific fields of integrated urban development addressed in the identified UDG documents can offer more insights into the links between these two fields.

3. Methodology

3.1. Preliminary considerations and research design validation

As the principal method, we chose structured online research (Kim and Kuljis, Reference Kim and Kuljis2010; Schweitzer, Reference Schweitzer2010; Welker and Wünsch, Reference Welker, Wünsch, Schweiger and Beck2010; Welker et al., Reference Welker, Taddicken, Schmidt and Jackob2014) for policy documents on UDG in a sample of German small towns and all rural districts. The approach was based on two assumptions: (1) The existence of a document defining rules, guidelines, or outlining typical elements of a local DG is a strong indicator of systematic UDG. (2) To promote their digital and/or data policy, town administrations have an interest in publishing documents, such as strategies, guidelines, or public presentations that should be findable online.

To validate the methodology and assess the overall research design, we discussed the underlying assumptions and reflected on the hypotheses and preliminary results in three interviews with four experts in the field of DG, digital strategies, and smart city strategies in German municipalities between February 2024 and August 2024. At the time of the interviews, the experts were affiliated with the following institutions: One expert with the German Association of Towns and Municipalities (Deutscher Städte- und Gemeindebund, DStGB), one expert with the German Institute of Urban Affairs gGmbH (Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik, Difu), and two experts with the Institute for Innovation and Technology (iit) within the VDI/VDE Innovation + Technik GmbH.

All experts interviewed confirmed assumptions (1) and (2). However, one expert pointed out that officially published strategy documents typically need to receive approval from town councils. This could lead to informal municipal practices of systematic DG that are not explicitly reflected in public strategies, following a more pragmatic approach to avoid time-consuming public debates and possible opposition. Another expert also mentioned the political character of strategy documents, which can lead to tactical maneuvers hindering publication to influence negotiations in local politics. A third expert underlined the impossibility of implementing a sustainable local DG without foundations in a strategy document.

3.2. Structured online content research and analysis

Using a customized Python script for the semiautomated entry of search strings, we conducted the structured online search using the search engine Google (https://www.google.com/, date accessed: March 25, 2024) for each sample town and for all rural districts. We performed nine different searches per administrative unit using the respective name combined with nine different keywords as search strings (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “03 Procedure Systematic Online Research.pdf”). For each search string combination ([town name/district name] + [keyword_1–9]), we screened the first 10 search results of each search for documents containing data strategies or elements of DG guidelines. We then analyzed the identified documents and categorized them based on a predefined four-level gradation assessing the comprehensiveness of systematic UDG across key aspects of UDG described by Helder et al. (Reference Helder, Libbe, Ravin and Henningsen2023, pp. 15–29) and suggested guidelines by the German Smart City Dialogue (Fuhrmann et al., Reference Fuhrmann, Böttcher and Bimesdörfer2021). Definitions of the levels following the resulting criteria catalogue (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “01 Criteria Data Governance Documents Research.pdf”) are briefly outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Definition: Levels of DG of identified policy documents

We set our focus on municipal data strategies of global character for the town. Data strategies of municipal enterprises, such as utility companies, were only considered if they were a substantial part of the municipal strategies or related guidelines. As proof of concept, this online search strategy was successfully performed for three municipalities with existing relevant documents known to the authors (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “04 Protocol Online Research.pdf”).

3.3. Small town sample

We drew the sample of small towns based on the following categories. Küpper’s (Reference Küpper2016) systematic typology of German regions classifies all German districts into the four Thünen Types (1–4) given by the matrix of the two dimensions rurality and socioeconomic situation (Küpper, Reference Küpper2016, p. 17, Thünen Type 5 describes districts in nonrural areas and does not distinguish socioeconomic situations). The typology is used for this study despite some possible minor changes that could appear in a newer version currently being developed at the moment of writing (Thünen-Institut, n.d.).

Besides its aforementioned definition of small towns as municipalities with 5,000–20,000 inhabitants or towns with “at least medium-central function” (BBSR, n.d.), BBSR further distinguishes the subcategories smaller small towns (below 10,000 inhabitants) and larger small towns (BBSR, n.d.). Some towns are classified by BBSR as larger small towns, although they have less than 10,000 inhabitants.

To reflect the distribution of rurality and the socioeconomic situation of German small towns, we attributed the five Thünen Types (Küpper, Reference Küpper2016) of the respective districts to all German municipalities. The municipalities defined as “small towns” following the official definition of BBSR (n.d.; n = 2,174) are subcategorized as “smaller small town” (Kleine Kleinstadt) and “larger small town” (Größere Kleinstadt). Combining these two size categories with the five Thünen Types results in a matrix of 10 categories. We generated an initial random sample of 30% of all towns in each category, resulting in n = 653 small towns out of which n = 443 small towns were researched, representing a minimum percentage of 16.5% of each small-town category. Preliminary result analysis led to the decision to discontinue research for the remaining small towns of the sample, but extend it on the district level for all rural districts. The examined sample is evenly distributed across the federal states; nevertheless, the total number of small towns across the federal states can vary significantly due to population density and different municipal structures.

3.4. Content analysis along defined categories of thematic aspects of urban development

To perform content analysis of the identified policy papers, nine thematic categories of integrated urban development were defined, based on a comparison and synthesis of thematic key aspects in four different guidelines on the generation of an integrated urban development concept (German: Integriertes Stadtentwicklungskonzept and other similar names existing; cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “05 Deduction and Definition Categories Urban Development.xlsx”). The resulting categories are:

-

• Housing

-

• Urban design and public space

-

• Mobility and technical infrastructure

-

• Economy and trade

-

• Culture, tourism, and leisure

-

• Climate protection and climate adaptation

-

• Natural areas

-

• Social infrastructure and public services

-

• Demography and civic engagement.

Possible values for assessing the consideration of aspects comprised by the respective categories are “yes” and “no”. We analyzed all identified documents on the town and district level using the described content analysis matrix. Figure 1 (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “06 Research Design Scheme.pdf”) provides an overview of the overall research design. Research data processing, including research data quality management, is depicted in the research data processing scheme (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “07 Research Data Processing Scheme.pdf”; for assessment of rater reliability: “13 Jupyter Notebook 2 Rater Reliability Data Governance Levels.zip” (resulting weighted Cohen Kappa = 0.98) and “14 Jupyter Notebook 4 Rater Reliability Thematic Content Analysis.zip” (resulting weighted Cohen Kappa = 0.99). Sampling was performed in Jupyter Notebooks (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “08 Jupyter Notebook 1 Data Processing and Sampling Small Towns.zip”, “09 Jupyter Notebook 3 Data Processing Districts.zip”, and “10 Jupyter Notebook 5 Data Processing Metropolitan Regions.zip.”).

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the research design (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “06 Research Design Scheme.pdf”).

4. Results

4.1. Number of documents on the town and district level

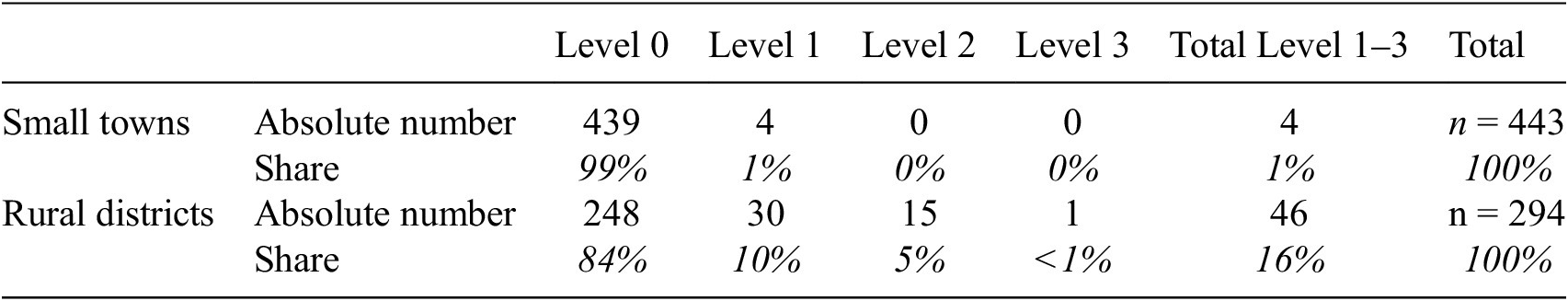

Systematic online research revealed a total number of only four small towns out of n = 443 (i.e., <1%) that had published online a strategy on DG categorized as Level 1 (cf. Table 2). All other investigated towns did not have a relevant document and were hence categorized as Level 0.

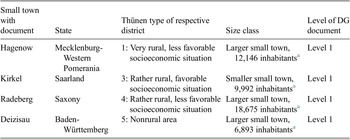

Table 2. Key characteristics of the four small towns with a Level 1 DG document

a BKG Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie. (n.d.). Verwaltungsgebiete 1:250,000 mit Einwohnerzahlen, Stand 31.12. (VG250- EW 31.12). https://gdz.bkg.bund.de/index.php/default/verwaltungsgebiete-1-250-000-mit-einwohnerzahlen-stand-31-12-vg250-ew-31-12.html, last access: December 05, 2024.

None of the four small towns with a data strategy document on Level 1 are part of a district administration with a respective document > Level 0. On the district level, for 16% of the districts, a policy document with aspects of UDG could be identified. Documents were categorized in all defined levels of DG (cf. Table 3). The geographical distribution of identified DG policy documents in small towns and rural districts across German federal states is depicted in Figure 2.

Table 3. Total numbers and rounded percentage shares of data strategies in researched small towns and districts per level

Note: Level 0, no document; Level 1, single DG aspects; Level 2, DG section/various DG aspects; Level 3, dedicated DG document.

Figure 2. Rural districts per DG level of policy documents across federal states and small towns with identified DG documents (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025) “11 Results_Interactive Map.html”). No scale. Base map: BKG Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie. (n.d.). Verwaltungsgebiete 1:250,000 mit Einwohnerzahlen, Stand 31.12. (VG250-EW 31.12), source: https://gdz.bkg.bund.de/index.php/default/verwaltungsgebiete-1-250-000-mit-einwohnerzahlen-stand-31-12-vg250-ew-31-12.html, last access: December 05, 2024.

4.2. DG documents on the district level

The analysis on district level reveals the highest percentage of DG-related documents found for districts in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein, followed by the states of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and North Rhine-Westphalia. Thuringia is the only federal state with no document found at the district level. Comparison of absolute numbers and percentages also visualizes a very heterogeneous number of districts across the German territorial federal states (without city states, cf. Figure 3).

Figure 3. Data governance documents (DGD) on the district level per federal state, absolute numbers (above), and percentage shares (below).

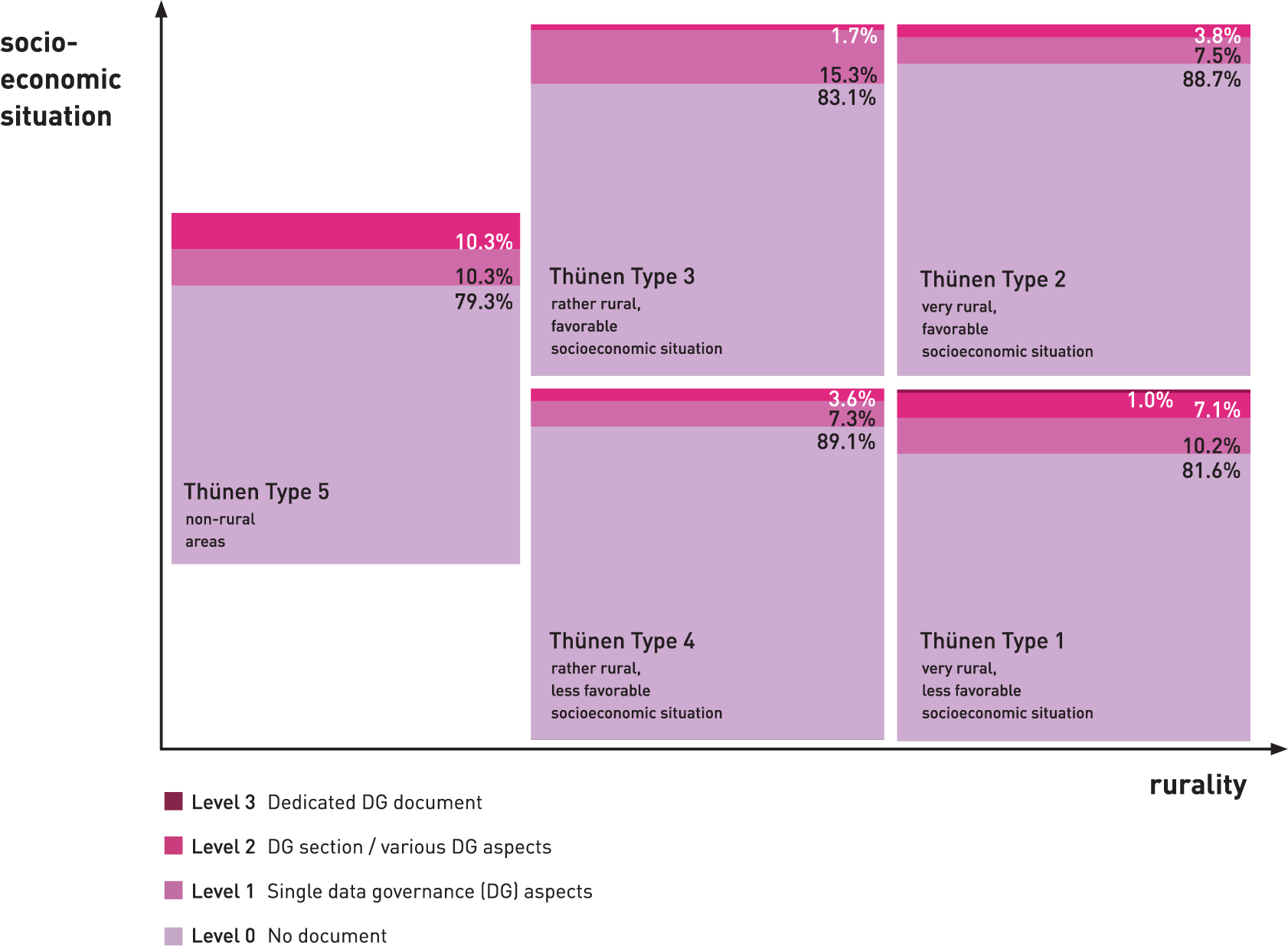

4.3. Correlation of DG documents with Thünen types on the district level

Analysis of the identified documents showed no significant correlation of the existence of a document, neither to one specific Thünen Type on the district level nor to one of the two constituting dimensions, including socioeconomic situation and rurality (cf. Figure 4).

Figure 4. Shares of identified DG documents per DG level and Thünen Type on the district level. Own representation based on Küpper (Reference Küpper2016, p.17). Percentage sums below 100% are possible due to rounding tolerances.

4.4. Content analysis of identified DG documents along defined aspects of urban development

We used the identified documents of 4 small towns and 46 rural districts to examine which categories of urban development are addressed (cf. Section 3.4). Each category could only be counted once per document. For this analysis, we considered all sections of each identified document, often comprising, besides DG and strategic sections, also concrete projects.

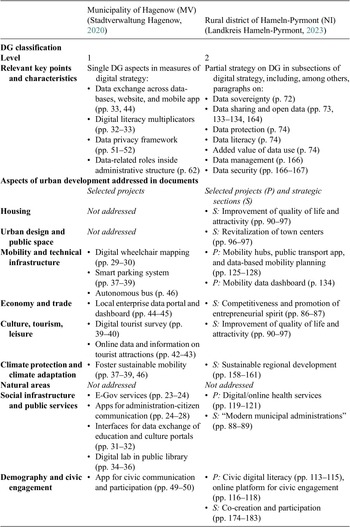

To illustrate the performed content analysis and key point identification, Table 4 summarizes exemplarily relevant aspects for DG level classification and sections for content analysis on aspects of integrated urban development for “typical” documents from the small town of Hagenow and the rural district of Hameln-Pyrmont.

Table 4. An exemplary summary of key points of the two identified documents for DG classification and for content analysis on aspects of urban development

Results of the performed content analysis of all identified documents (n = 50) show a strong focus on economy and trade as the most addressed aspect, followed by social infrastructure and public services. As shown in Figure 5, “typical” spatial key aspects of urban development like housing and urban design and public space are among the least frequently addressed aspects.

Figure 5. Absolute counts of addressed defined aspects of urban development in identified DG documents on district and small-town level.

5. Discussion

Our research revealed policy documents for fewer than 1% of the small-town sample, each mentioning only single DG aspects (that is, Level 1 of the criteria catalogue). In contrast, 16% of all rural districts published online a relevant policy document with identified strategies ranging from Level 1 to Level 3. There is no significant correlation across districts of the existence of formalized DG with the federal state, nor with the socioeconomic situation or the degree of rurality of the district. The low number of documents identified did not allow for conclusions on small-town level in this regard. Content analysis of the identified documents along defined categories of integrated urban development revealed that “economy and trade” is the most frequently addressed aspect, whereas spatially relevant aspects, such as urban design and public spaces, are among the least frequently addressed aspects. The very low percentage of small towns with aspects of formalized DG and a relatively more important share of rural districts disposing of DG-related policy documents confirm our initial assumptions as well as statements of the experts interviewed. This not only corresponds with observations in other contributions regarding data availability and literacy in small towns (Milbert and Fina, Reference Milbert, Fina, Steinführer, Porsche and Sondermann2021; Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023) and digital and data-based approaches in small towns (Damm and Spellerberg, Reference Damm and Spellerberg2021; Dembski et al., Reference Dembski, Wössner, Letzgus, Ruddat and Yamu2020; Hosseini et al., Reference Hosseini, Frank, Fridgen and Heger2018; Ruohomaa et al., Reference Ruohomaa, Salminen and Kunttu2019; Soike and Libbe, Reference Soike and Libbe2018; Spicer et al., Reference Spicer, Goodman and Olmstead2021), but also reflects the current status quo of dissemination of UDG guidelines in larger German cities (Schmuck, Reference Schmuck2024). With regard to the higher share of formalized DG in districts, our findings raise questions about the interplay and influence of the regional and local administrative levels in UDG in practice. More generally, this finding points to an important role of intermediate districts (cf. Bischoff and Bode, Reference Bischoff and Bode2021; Schulz, Reference Schulz2017) and inter-municipal cooperation (cf. Dehne et al., Reference Dehne, Hoffmann, Roth, Mainet, Gustedt, Grabski-Kieron, Demazière and Paris2022, pp. 117–118) in the governance of urban digital innovation within federal systems.

The assumed correlation of formalized DG with socioeconomic conditions and rurality could not be found. The dominance of economy and trade, as well as social aspects, in the identified documents could reflect the current understanding and implementation in Germany of smart city approaches, often driven by the interest of economic development but also, especially in rural regions, by the interest to enhance social conditions. Somewhat surprising is the weak link to spatial aspects of urban development, which reveals a potential gap between the intentions at the European and federal levels (EC, 2020b; Fuhrmann et al., Reference Fuhrmann, Böttcher and Bimesdörfer2021) to integrate data-based approaches with urban development and the actual implementation in regional practice.

While there are outstanding international examples of UDG implementation in larger cities, such as Barcelona (Monge et al., Reference Monge, Barns, Kattel and Bria2022) or London (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Panagiotopoulos and Bowen2020), recent studies focusing more broadly on Europe (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023) also emphasize UDG in large urban areas. Nevertheless, research on smart city governance in smaller towns and rural areas is emerging in various countries in Europe (e.g., Ruohomaa et al., Reference Ruohomaa, Salminen and Kunttu2019; Ševčík et al., Reference Ševčík, Chaloupková, Zourková and Janošíková2022; Viale Pereira et al., Reference Viale Pereira, Temple and Klausner2024) but also beyond (e.g., in Canada; Spicer et al., Reference Spicer, Goodman and Olmstead2021). However, contributions on UDG specifically in small towns in other countries remain scarce. Existing literature points toward similarities with our findings, such as the lack of “… applicability to municipalities and … adaptation to local contexts …” of centralized UDG guidelines in Estonia (Rajamäe Soosaar and Nikiforova, Reference Rajamäe Soosaar and Nikiforova2025, p. 13).

By mapping the current landscape of formalized UDG in German small towns and districts and accounting for their specific characteristics, we established a foundation for further research into factors that may foster or hinder the emergence of formalized UDG in these areas, as well as for a broader understanding of governance of digital innovation and transformation on small-town level in federal systems.

We aimed at reducing limitations through methodological quality management in research design (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “06 Research Design Scheme.pdf”) and data processing (cf. Higi (Reference Higi2025), “07 Research Data Processing Scheme.pdf”). Nevertheless, the clear methodological approach with simple sampling categories and high reproducibility bears some constraints on the resulting data. Due to district reforms in Germany, some municipalities have the formal status of small towns, yet comprise several historically independent villages (Franzke, Reference Franzke, Weith and Strauß2017). To apply the research scheme consistently across the administrative specificities of the federal states and facilitate generalizability, we targeted comparable administrative units, that is, small towns utilizing BBSR’s official definition (n.d.) and rural districts, without considering inter-municipal cooperations of rather informal character. For several reasons, some policy documents might not have been published and findable online during our research between September 2023 and August 2024. With developments in this field being very dynamic, new strategic documents might be published in the months and years to come, positioning this study as a snapshot of the current status quo. In addition, interviewed experts pointed out that publication or council acceptance of policy documents can be subject to power dynamics in local politics; nevertheless, existing policy documents on UDG reflect the intention of the local administration as well as the discourse and process on the municipal level, which led to the issue of the document. For these reasons, the methodological approach followed in this article bears certain limitations as it does not fully capture the complexity of local governance processes and the resulting actual local DG practice. Although informal and internal documents may have limitations such as restricted access, future research could additionally incorporate these resources or include direct surveys among municipal administrations. Although we aimed at maximizing reproducibility of the research design, its adaptation to the German context bears some constraints to the generalizability of the findings, as they are particularly linked to the specificities of the municipal role and high degree of municipal autonomy within the German federal governance system.

The question of causal predictors of formalized UDG at municipal and district levels and emerging patterns within administrative delimitations remains open, but is beyond the scope of this study. Concentrations of formalized UDG, for example, in North Rhine-Westphalia on the district level, as well as experts’ statements in interviews, suggest possible influencing factors and future research directions: (1) Funding programs: Digital strategies are an objective or prerequisite of funding phases in Germany’s federal smart city funding program, Model Projects Smart City MPSC (BMI, n.d.). (2) Policies at the state or federal levels: Research on local digital transformation indicates challenges in implementing and scaling standardized digital approaches on local level due to Germany’s multilevel administrative system (Kuhlmann and Heuberger, Reference Kuhlmann and Heuberger2023). (3) Personal networks and regional proximity of municipalities and districts, paralleling the “upscaling debate” on innovation diffusion in sustainability programs on the municipal level (Kern et al., Reference Kern, Eckersley and Haupt2023). Actual UDG practice in small towns and districts with identified documents and their effects on sustainable municipal development remains to be researched. This relates to identifying best practices for DG in small towns, considering competencies amid scarce resources (Sautter et al., Reference Sautter, Henze-Sakowsky, Lindner, Schweigel, Dobrokhotova, Seick, Kirchner and Braun2023) and exploring synergies from inter-municipal cooperation or centralized district coordination.

Our findings suggest that, on a practical level, assistance and knowledge related to the structured use and governance of data should also be tailored more specifically to the needs of smaller town administrations. This aligns with broader findings for different city types and EU countries, highlighting “… the need for more guidance from the scientific community. Cities need significant support in designing their data governance practices…” (Bozkurt et al., Reference Bozkurt, Rossmann, Konanahalli and Pervez2023, p. 85672). In addition, showcasing best practices for different administrative levels (town level, district level, and inter-municipal cooperations) could be highly beneficial, particularly since the dissemination of UDG appears to be more successful on the district level in smaller urban areas. These policy implications are especially relevant for the German case at a time when Germany’s federal smart city funding program (MPSC) is coming to an end, and as a result, many prototypical smart city initiatives and project-based organizational units—both in larger cities and smaller towns—will need to be integrated into regular administrative structures (BMWSB, 2024).

6. Conclusion

In the present article, we gave an overview of the research on online published policy documents on UDG that we performed for a sample of small towns and all districts in Germany. As initially assumed, the dissemination of formalized UDG among German small towns is rather low. Results revealed a significantly higher percentage of districts disposing of relevant policy documents than the sample of small towns. The present mapping of UDG in smaller municipalities and rural areas, while offering limited explanatory power for underlying causes, provides some groundwork by validating common conjectures and exploring possible correlations. While rurality and socioeconomic situation of the districts do not seem to have any important influence on the existence of a respective document, the heterogeneous distribution of formalized DG across German federal states could indicate starting points for follow-up research explaining patterns of innovation diffusion in DG strategies. After taking stock of formalized DG in small towns and the related upper administrative levels, we can conclude that, while formalized UDG is currently rare in small towns, the role of districts and a regional perspective should be considered when exploring potential upscaling across small towns. DG approaches identified in this research do not seem to be as closely interwoven with sustainable urban development, nor do they even have potential effects on it as intended by urban policies (EC, 2020b). This article aims to offer insights to policymakers regarding the effectiveness of UDG initiatives in small towns, while informing the ongoing discourse on inter-municipal cooperation and the role of districts in digitalization within Germany’s multilevel system. Building on the foundation established in this article, future research should shed light on the actual practice in the respective administrations and discuss potential to foster data-based sustainable transitions in small municipalities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dap.2025.10051.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study and all supplemental material (e.g., code for sampling and data analysis) are published in ZENODO (CC BY 4.0; Higi, Reference Higi2025). These data were partly derived from the following resources available in the public domain (also referenced in Higi (Reference Higi2025), “07 Research Data Processing Scheme.pdf”): BBSR Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung, 2021; BKG Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie, n.d.; Thünen-Institut Forschungsbereich ländliche Räume (Ed.), 2024.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Philip Wiemer for his extensive support in the research and thematic content analysis of the policy documents, as well as the experts interviewed providing substantial thematic insights and reflections on the research conducted. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their constructive feedback and thoughtful guidance, which have contributed to a substantial improvement of the article.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: L.H. Data Curation: L.H. Formal analysis: L.H. Investigation: L.H. Methodology: L.H. Visualization: L.H. Writing—original draft: L.H. Supervision: T.S. and S.W. Writing—review and editing: T.S., S.W. and H.N. All authors approved the final submitted draft.

Provenance

This article was submitted for consideration for the 2025 Data for Policy Conference to be published in Data and Policy on the strength of the Conference review process.

Funding statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Statement on the use of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools

During the stages of data processing and analysis, ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) was used for coding assistance to simplify and debug code snippets. This use of the AI tool was also disclosed in the respective Jupyter notebooks included in the supplemental material.

Interview consent statement

Informed written consent to take part was obtained from all interview partners before conducting the expert interviews. This consent includes the publication of anonymized interview content, with all personal identifiers removed. Additionally, participants were informed and agreed to the disclosure of their professional affiliation as part of the study’s findings.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.