Introduction

Small ceramic bottles (unguentaria and amphoriskoi) are traditionally associated with perfumes and medicines (Brun Reference Brun2000), but their contents, like those of many Phoenician vessels (Hellenistic–Roman), remain understudied. Ancient texts mention a Phoenician trade in aromatics, and the consideration of literary and epigraphic sources highlights coastal centres like Sidon and indirect evidence for the involvement of Tyre (Frangié-Joly Reference Frangié-Joly2016). Although there is no direct archaeological evidence for the production of aromatics in Tyre, local vessel output and references to traded essences indicate a possible industry and involvement in trade.

This study uses the term ‘Tyrian’ to denote a broader regional phenomenon involving multiple production sites in and around Tyre, rather than a single workshop. While dispersed workshops have been proposed (Frangié-Joly Reference Frangié-Joly2017: 28–31), our working definition is based on the most recent archaeological and archaeometric data. Petrographically, the vessels analysed in this study show fine granulometry with quartz, iron-oxide nodules and microfossils in the coarse fraction. Preliminary results from the project ‘A holistic approach to ceramic production in Tyre’ identify several workshops, with some vessels corresponding to Phoenician Semi-Fine Ware (Berlin Reference Berlin and Herbert1997: 54–68), found throughout the eastern Mediterranean and Black seas (Papuci-Władyka Reference Papuci-Władyka and Blajer2012).

Given their production in Tyre, we assume that these vessels contained substances produced locally or imported into Tyre and subsequently distributed elsewhere. This assumption guided our sampling strategy, which included five sites across the eastern Mediterranean.

Organic residue analysis, including gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and gas chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (GC-HRMS), allow for precise identification of adsorbed substances in ceramic matrices. HRMS permits a metabolomics approach, which identifies small organic molecules preserved in archaeological samples. High-resolution methods (e.g. lipidomics, proteomics, sterolomics) enable the detection of complex residues preserved as tiny traces. We apply these methods, alongside typo-chronology and archaeometry, to assess the role of Tyre in Hellenistic-Roman (third century BC–first century AD) exchange networks, investigate how vessel form, contents and context correlate with function. Despite obstacles like post-depositional contamination, this integrated approach offers new insights into Phoenician material culture.

Case study

Eleven unguentaria and four amphoriskoi dating from the third century BC to the second century AD were examined. Samples were taken from complete and fragmentary vessels, which were either recently excavated or held in storage, from Tyre (Acropolis, Hippodrome, Borj), Sidon (Wastani), Chhim, Nea Paphos and Olbia (Figure 1). The vessels come from diverse contexts: funerary, domestic, religious, mercantile and industrial. The key aim is to assess whether vessel form and content correlates with context-based function.

Figure 1. Sample sites in the Mediterranean and Black seas (figure by U. Wicenciak).

Methods

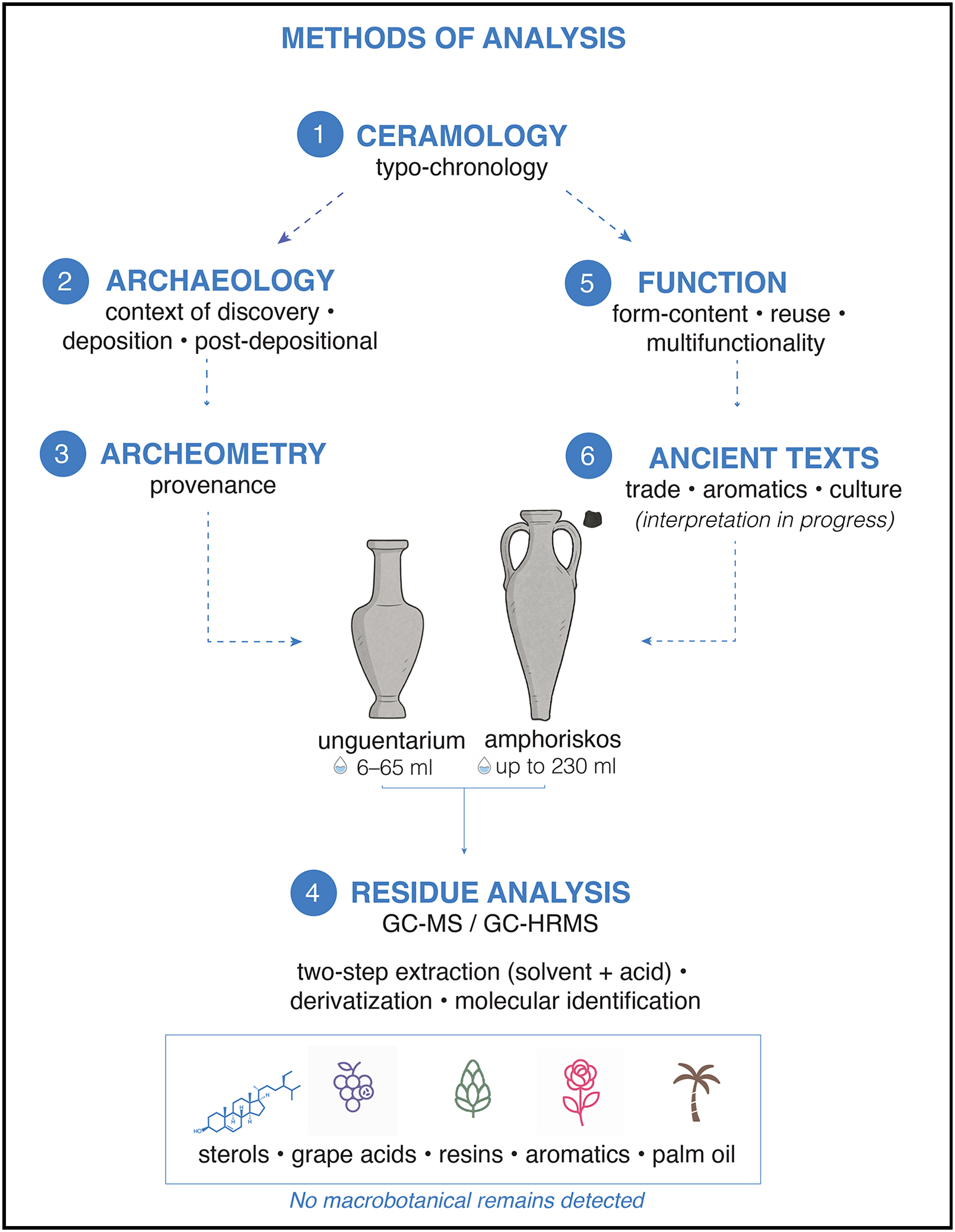

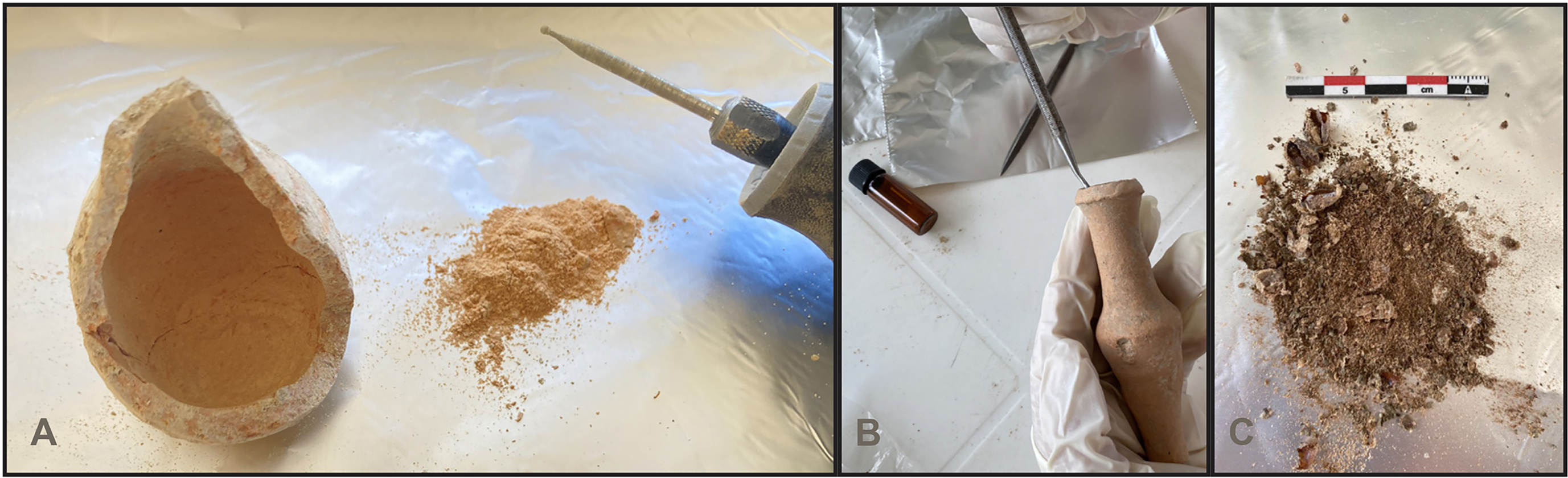

The study’s interdisciplinary approach is outlined in Figure 2. The inner surfaces of vessels were scraped to collect any preserved contents for analysis (Figure 3). Four Nea Paphos samples were analysed by GC-MS at the University of Bradford (UK) but showed no significant lipid content, probably due to degradation or extraction polarity and sampling depth (Garnier Reference Garnier2022: 291–92). GC-HRMS was applied to 11 samples (Tyre, Sidon, Chhim and Olbia) to increase sensitivity. Analysis followed established protocols to minimise contamination and application of a two-step extraction protocol (solvent and anhydrous acid) improved molecular recovery (Garnier & Valamoti Reference Garnier and Valamoti2016). Step one used an organic solvent for lightly adsorbed compounds, and step two used an anhydrous acidic medium for more strongly bound compounds. Extracts were derivatised to improve separation. GC-HRMS identified molecular markers by mass spectrum and exact mass. The absence of macrobotanical remains restricts archaeobotanical interpretation. Plant-derived biomarkers—such as epicuticular waxes—may contribute to future interdisciplinary interpretations within the broader research framework.

Figure 2. Analytical workflow used in the study (figure by U. Wicenciak).

Figure 3. Sampling with a Dremel rotary tool (A) and a dental tool (B), and the contents of an unwashed vessel (C) (A & C by U. Wicenciak; B by Jose Maria Lopez Gari).

Results

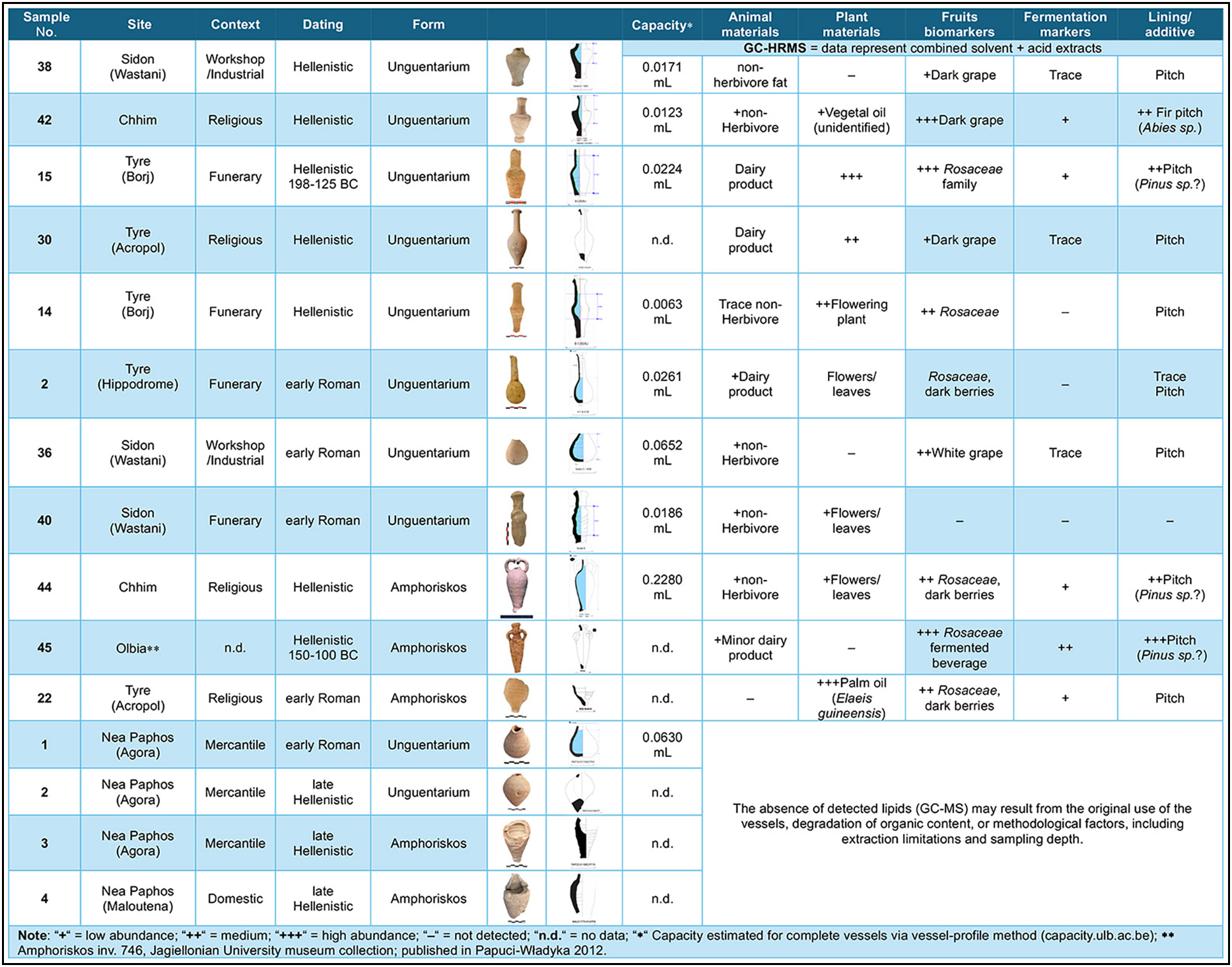

Although the varied provenance and context of the samples limits broader interpretation, our results demonstrate the potential of this approach on a case-by-case basis. All samples contained preserved residues, reflecting multifunctional vessel use (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Summary of molecular analyses: GC-HRMS samples from Tyre, Sidon, Chhim and Olbia; GC-MS samples from Paphos (figure U. Wicenciak & N. Garnier).

Sterols and lipids

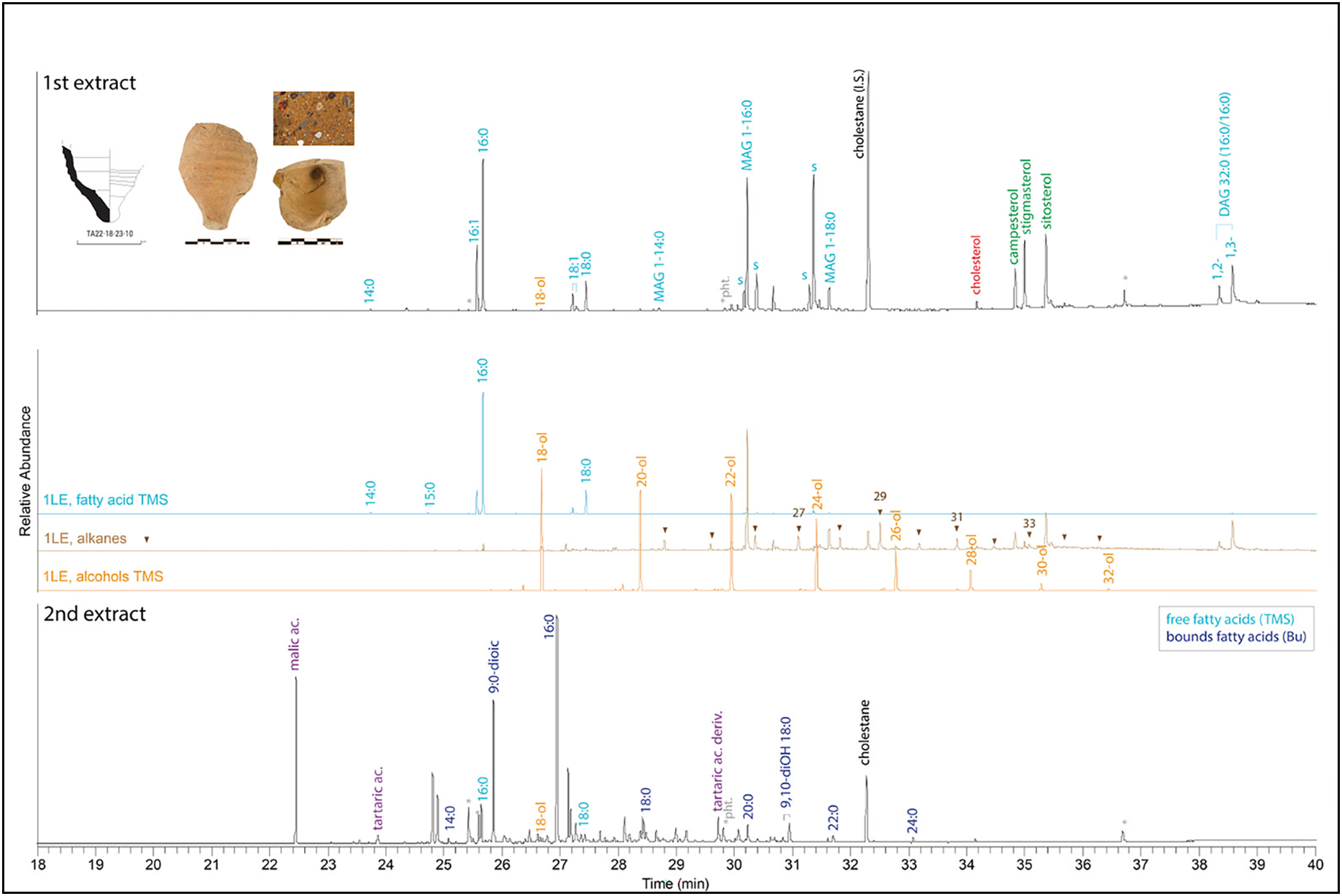

Cholesterol and sitosterol ratios indicate animal and plant contents, in combination with acylglycerols and fatty acids; no specific biomarkers for dairy were detected. Notably, a Tyrian amphoriskos contained palm oil from Elaeis guineensis (Figure 5), indicating its importation from subtropical regions and varied applications.

Figure 5. Lipid chromatograms for amphoriskos sample 22, trimethylsilylated extract. Detected markers include fatty acids (palmitic acid 16:0, stearic acid 18:0), diglycerides and sterols (sitosterol, stigmasterol), indicating palm oil. Tartaric and syringic acids suggest fermented fruit. Conifer pitch is also detected (figure by N. Garnier).

Resins and sealants

Free and methylated dehydroabietic acid, with retene, in specific ratios, confirm conifer pitch (Pinus sp. and Abies sp.), used for waterproofing or aromatic purposes.

Grape-derived acids

Tartaric, malic and syringic acids in specific ratios confirm grape-based contents: wine, vinegar, berries.

Aromatic biomarkers

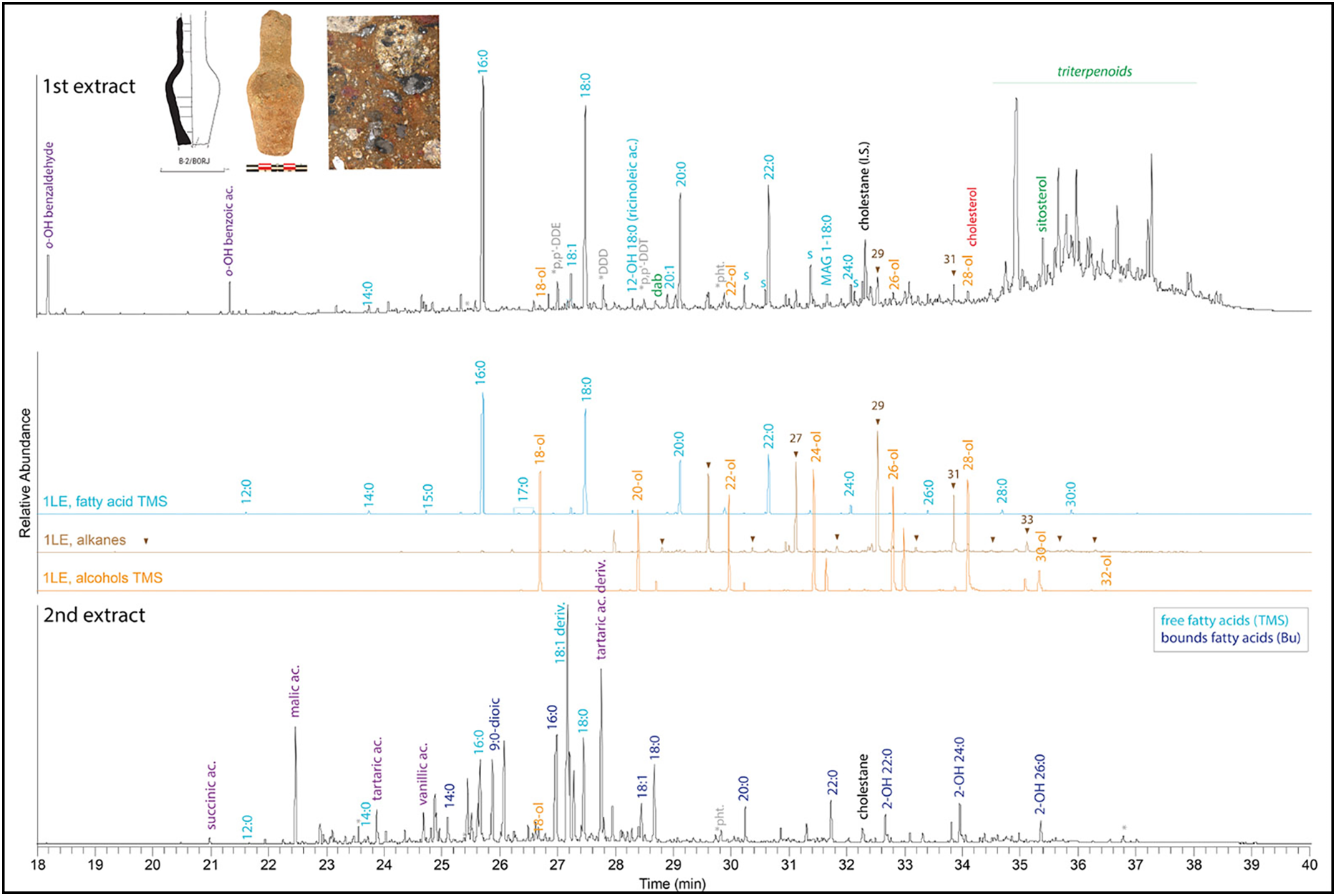

An unguentarium from Borj yielded floral biomarkers (e.g. linalool, α-terpineol), implying aromatic or medicinal functions (Figure 6). The diversity of chemicals—plant/animal sterols, terpenic acids, fruit markers—reflects aromatic or medicinal preparations and/or sequential use.

Figure 6. Lipid chromatograms for unguentarium sample 15, trimethylsilylated extract. Detected molecular markers include fatty acids (palmitic acid 16:0, stearic acid 18:0), sterols (cholesterol, sitosterol) and triterpenoids originating from flowering plants (figure by N. Garnier).

Other

Some chemical profiles combining animal fats, fruit acids and diterpenic resins suggest complex histories of vessel use. Previous studies, such as, the analysis of unguentaria from Cumae revealing mixtures of red wine, oleoresins and animal fats (Brkojewitsch et al. Reference Brkojewitsch, Garnier, Duday, Frère, Del Mastro, Munzi and Pouzadoux2021), support the interpretation of wine, as a component in aromatic or ritual preparations.

Interpretations of the aromatic content of Phoenician vessels has primarily been based on vessel form and archaeological context. Our results provide the first chemical evidence for multifunctional use of two container types, including for fermented liquids and conifer-based resins. This interpretation is supported by residue analyses of Phoenician amphoriskoi (e.g. Koh et al. Reference Koh, Berlin and Herbert2021), which identify cedar oil, highlighting aromatic and preservative applications.

Conclusions

This pilot study advances understanding of Phoenician material culture and the socioeconomic complexity of the Hellenistic and early Roman eastern Mediterranean. The results suggest a correlation between vessel form and contents, with amphoriskoi likely used for fermented liquids and unguentaria for oils and resins. Chemical markers (aldaric and diterpenic acids) support this interpretation. The combinations of compounds recorded in several samples—sometimes inconsistent with the expected functions—suggest versatile use or reuse of the vessels.

Despite contamination or secondary use, the results highlight the value of integrating residue analysis with archaeological context. Further comparative studies focusing on well-defined contexts are essential to refining our understanding of Phoenician production and trade.

Acknowledgements

The host institution is the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw. We thank Jose Maria Lopez Gari for his assistance with documentation and sampling. Special thanks go to Sarkis Khoury, Director of the Directorate General of Antiquities, as well as Miriam Ziade and Anna Georgiadou for facilitating the export permits for samples from Lebanon and Cyprus.

Funding statement

Funded by the University of Warsaw (New Ideas 3B, grant PSP: 501-D353-20-4004310/ https://pcma.uw.edu.pl/en/2023/04/27/tyre-scent-substances/). X-ray diffraction analyses supported by National Science Centre Poland (grant 2021/43/B/HS3/00354), project: ‘A holistic approach to ceramic production in Tyre’ (PI: F.J. Núñez Calvo, PCMA UW/ https://pcma.uw.edu.pl/en/2023/04/19/project-a-holistic-approach-to-tyre-ceramic/).